Abstract

Epithelial glucose transport is accomplished by Na+-glucose cotransporters SGLT1 and SGLT2. In the intestine, uptake of dietary glucose is for its majority mediated by SGLT1, and humans with mutations in the SGLT1 gene show glucose/galactose malabsorption. In the kidney, both transporters, SGLT1 and SGLT2, are expressed and recent studies identified that SGLT2 mediates up to 97% of glucose reabsorption. Humans with mutations in the SGLT2 gene show familial renal glucosuria. In the last 3 decades, significant progress was made in understanding the physiology of these transporters and their potential as therapeutic targets. Based on the structure of phlorizin, a natural compound acting as a SGLT1/2 inhibitor, initially several SGLT2, and later SGLT1 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors have been developed. Interestingly, SGLT2 knockout or treatment with SGLT2 selective inhibitors only causes a fractional glucose excretion in the magnitude of ~60%, an effect mediated by upregulation of renal SGLT1. Based on these findings the hypothesis was brought forward that dual SGLT1/2 inhibition might further improve glycemic control via targeting two distinct organs that express SGLT1: the intestine and the kidney. Of note, SGLT1/2 double knockout mice completely lack renal glucose reabsorption. This review will address the rationale for the development of SGLT1 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors and potential benefits compared to sole SGLT2 inhibition.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, renal glucose transport, intestinal glucose transport, drug development, sodium-glucose cotransporter, inhibitor, chronic kidney disease, heart failure

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a leading cause of cardiovascular and end-stage kidney disease,1 resulting in a tremendous economic burden for treating diabetes that costs approximately 825 billion US dollars per year worldwide.2 Currently, there are several different pharmaceutical options available for the treatment of diabetes mellitus (e.g. sulphonylureas, metformin, glitazones, insulin, glucagon-like peptide receptor 1 agonists); however, there are significant drawbacks when it comes to cardiovascular outcomes. Only glucagon-like peptide receptor 1 agonists seem effective in reducing cardiovascular risks, while other treatment options have neutral effects on cardiovascular mortality. In recent years, much attention has been on Na+-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, also known as gliflozins, as a new class of anti-hyperglycemic drugs used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and possibly as an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). The FDA and other agencies have now approved multiple SGLT2 inhibitors and one dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor (Table 1). This review will discuss the rationale for either adding SGLT1 inhibition on top of SGLT2 inhibition (dual SGLT1/2 inhibition), or sole SGLT1 inhibition, in order to possibly achieve even better glycemic control and further improve cardiovascular outcomes.3 SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death; however, this was only seen in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and not in those with multiple risk factors. In contrast, regardless of whether atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or heart failure were present, treatment with SGLT2 inhibitor reduced the risk of hospitalization for heart failure and progression of renal disease.4 The underlying idea of this strategy is to reduce glucose burden by inhibiting the uptake of dietary glucose (mediated by SGLT1) in the intestine and excreting filtered glucose into the urine (mediated by SGLT2 and SGLT1) via the kidneys, but the logic extends beyond this.

Table 1.

Preclinical and clinical SGLT1, SGLT2 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors. This list is not all-inclusive. IC50 values and selectivity ratios vary with the experimental system and laboratory they are studied.

| Compound | SGLT1 ICso (nmol/L) | SGLT2 IC50 (nmol/L) | Selectivity (SGLT2 vs SGLT1) | Selectivity (SGLT2 vs SGLT1) | Selectivity (SGLT1 vs SGLT2) | Selectivity (SGLT1 vs SGLT2) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofogliflozin Apleway®,Deberza® | ~8400 | ~2.9 | ~2900-fold |  |

~0.0003-fold |  |

125,126 |

| Empagliflozin Jardiance® | ~8300 | ~3.1 | ~2700-fold | ~0.0004-fold | 34,127 | ||

| Ertugliflozin Steglatro® | ~1960 | ~0.9 | ~2200-fold | ~0.0005-fold | 34,128 | ||

| Luseogliflozin Lusefi® | ~4071 | ~2.3 | ~1770-fold | ~0.0006-fold | 129,130 | ||

| Dapagliflozin Farxiga® | ~1400 | ~1.2 | ~1200-fold | ~0.0009-fold | 131,132 | ||

| Canagliflozin Invokana® | ~710 | ~2.7 | ~260-fold | ~0.004-fold | 133,134 | ||

| Ipragliflozin | ~1875 | ~7.5 | ~250-fold | ~0.004-fold | 135,136 | ||

| UK066 Licogliflozin | ~21 | ~0.6 | ~35-fold | ~0.03-fold | 49 | ||

| Sotagliflozin Zynquista® | ~36 | ~1.8 | ~20-fold | ~0.05-fold | 95,107 | ||

| Phlorizin | ~400 | ~65 | ~6.2-fold | ~0.2-fold | 137,138 | ||

| T-1095 | ~200 | ~50 | ~4-fold | ~0.25-fold | 37,139 | ||

| LX2761 | ~2.2 | ~2.7 | ~0.8-fold | ~1.2-fold | 53,140 | ||

| TP0438836 | ~7 | 28 | ~0.25-fold | ~4-fold | 54 | ||

| Mizagliflozin | ~27 | ~8170 | ~0.003-fold | ~303-fold | 51,89 |

During evolution, food supply ad libidum was not part of our daily lives. Our bodies learned to cope with limited energy supply, which has been extensively “tweaked” over time to guarantee our survival. Therefore, it is not surprising that the body can respond to excess exogenous energy in a maladaptive or detrimental manner. Consequently, targeting energy homeostasis by decreasing intestinal glucose uptake into the body, spilling glucose into the urine, or both, and then by using counterregulatory mechanisms to readjust the metabolism, may provide unrecognized advantages as an anti-hyperglycemic modus operandi.5,6

Targeting SGLTs for glycemic control

Why target glucose transport in the kidney?

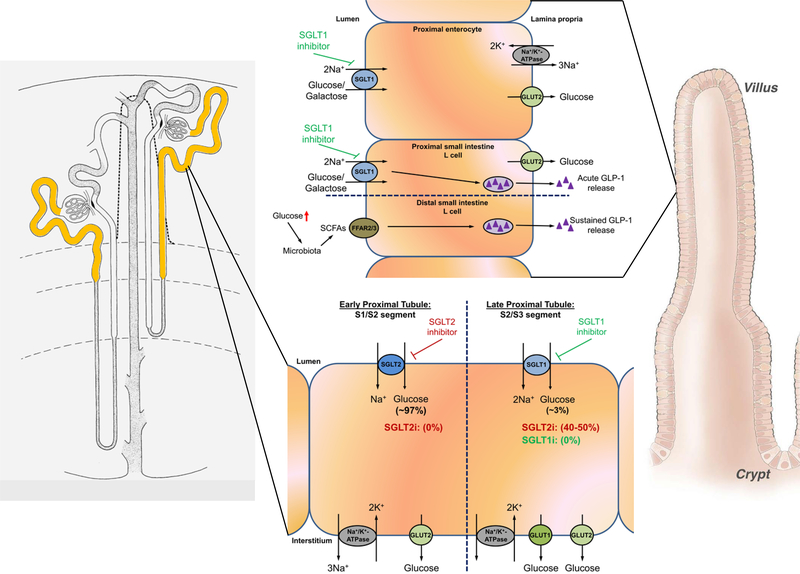

In healthy adult kidneys, all of the filtered glucose (~180 g/day) is reabsorbed by the proximal tubule (Figure 1). SGLT2 and SGLT1 are localized on the brush border membrane of the early S1/S2 and late S2/S3 proximal tubule segments, respectively. Glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule requires a secondary active transport process that depends on basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase activity to generate the driving force for apical glucose uptake via SGLTs.7 The glucose exits on the basolateral side following its concentration gradient via GLUT2 and re-enters the blood stream.8 The utilization of SGLT1 and SGLT2 knockout mice (SGLT1−/− and SGLT2−/−, respectively), and the micropuncture and clearance studies performed therein, clearly demonstrated that under conditions of normoglycemia, SGLT2 contributes to 97% of fractional glucose reabsorption (FGR) and SGLT1 contributes to 3% of FGR (Figure 1).9–11 Consequently, studies in SGLT1/2 double knockout mice (SGLT1/2−/−) confirmed that both transporters, SGLT1 and SGLT2, are responsible for all renal glucose reabsorption in normoglycemia.11 Interestingly, the expression pattern of renal SGLT1/2 is largely the same in rodents and humans; however, different from rodents, human SGLT1 has not so far been found in the thick ascending limb or macula densa, and expression of both SGLTs appears to be sex-independent.12

Figure 1.

Left: yellow color indicates sodium-glucose cotransporter 1/2 (SGLT1/2) expression along the proximal tubule. Right: expression of SGLT1 along villi of the intestine where SGLT1 mediates mass absorption of intestinal glucose/galactose. Several signals, including dietary carbohydrate content, leptin and others, as well as factors mediating effects of central/peripheral clock genes (diurnal expression changes) have been implicated in the regulation of SGLT1. Dietary glucose is sensed by SGLT1 in L cells of the proximal small intestine, subsequently leading to acute release of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Inhibition of SGLT1 has multiple effects: (i) inhibition of glucose absorption and (ii) acute and sustained release of GLP-1. Regarding the latter, increased glucose delivery to the distal small intestine causes glucose to be metabolized by the microbiome, resulting in generation of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that trigger sustained GLP-1 release via activation of fatty acid receptors (FFAR2/3) in distal L-cells. In the kidney, SGLT2 and SGLT1 mediate all glucose absorption under normoglycemia, with SGLT2 mediating 97% and SGLT1 mediating 3%, respectively (see text for details). Lack of SGLT2, SGLT2 inhibition (0% reabsorption where SGLT2 is expressed) or hyperglycemia unmasks a substantial capacity of SGLT1 for glucose absorption, up to 50%, in the late proximal tubule. Taken together, dual SGLT1/2 inhibition might reduce postprandial glucose excursion, improve insulin release/inhibit glucagon release and increase renal glucose excretion. GLUT1: glucose transporter 1, GLUT2: glucose transporter 2. For simplicity, not all signaling pathways are shown. See text for additional details.

The renal transport maximum of glucose is reached when blood glucose levels rise >200 mg/dL; consequently, glucose cannot be 100% reabsorbed and is found in the urine.13 Given this mechanism, the human body is able to avoid excessive hyperglycemic periods. However, under diabetic conditions, the renal transport maximum may increase, thereby allowing more glucose to be reabsorbed and contributing to a sustained hyperglycemia. It is still unclear why the increase in renal transport maximum for glucose occurs in diabetes, but there are several (mal)adaptive mechanisms in the kidney that might contribute. In the early stages of disease,14 tubular growth15 can result in an increase in kidney weight (especially the proximal tubule which comprises ~90% of the renal cortex) and may be associated with poor renal outcome.16 In addition, primary increases in renal expression of SGLT2 and/or SGLT1 have been observed in diabetic mice.17–19 Studies in T2DM patients identified that renal SGLT1 mRNA expression was markedly increased and SGLT2 mRNA levels (not significantly) downregulated.20 Of note, another study in patients with T2DM showed that both SGLT1 and SGLT2 mRNA expression were significantly lower as well as a qualitatively weaker SGLT2 labeling in the kidneys of T2DM patients versus well‐matched non-diabetic subjects was observed.21 Another study showed that SGLT2 and GLUT2 expression were significantly higher in proximal tubule cells isolated from the urine of patients with T2DM compared to healthy controls.22 Increasing renal glucose reabsorption in T1DM and T2DM seems counterproductive because it would rather maintain then fend off hyperglycemia. More studies are needed to elucidate these changes that occur in diabetes. That said, data from SGLT2−/− mice and by employing SGLT2 inhibitors indicate that without SGLT2, the reabsorptive capacity of the kidneys for glucose declines to the residual capacity of SGLT1, resulting in a fractional glucose reabsorption of 40% or ~80 g/day. Supporting these findings are studies in SGLT1−/− mice which, when treated with a SGLT2 inhibitor, completely lack renal glucose reabsorption.11

The first occurrence of renal glucosuria was described in 1927 with urinary glucose losses ranging from 1–150 g/1.73m2. 23 Meanwhile, ~50 mutations have been described which are most commonly caused by mutations in the gene encoding SGLT2. Due to its familial inheritance, the condition is referred to as familial renal glucosuria.24 The condition is generally considered benign; however, can present with symptoms like polydipsia, polyuria, urogenital infections (including candida) and postprandial hypoglycemia. So far, no long-term complications have been observed in patients with SGLT2 mutations.24,25 The “mild” phenotype of these patients supported the idea that developing SGLT2 inhibitors could be a potentially safe therapeutic approach to lower glucose levels.

Why target glucose transport in the intestine?

Blood glucose elevations after meals are associated with an increased risk of diabetic complications.26 Postprandial hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease; therefore, strategies aimed at preventing glucose excursions in diabetics may also be used for treatment of cardiovascular disease. The small intestine is the major site of dietary glucose absorption, which occurs predominantly through SGLT1 on the brush border membrane (Figure 1).9,27 On the basolateral side, glucose enters the circulation via the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT2. Interestingly, some studies have shown evidence that GLUT2 can translocate to the apical side of the enterocyte to contribute to luminal glucose uptake. This appears to be dependent on pre- and post-prandial luminal glucose concentrations28 and/or leptin levels (JA Dominguez Rieg and T Rieg, unpublished observations). In addition to glucose uptake, intestinal SGLT1 regulates the release of intestinal hormones implicated in glucose balance, including but not limited to, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) (Figure 1).6,9,29

Genetic mutations of SGLT1 in humans causes glucose-galactose malabsorption (GGM); initial case descriptions were reported almost simultaneously from Sweden and France in 1962.30 Patients become symptomatic in early infancy and have chronic watery diarrhea that, if left untreated, is lethal. Removing the offending sugars (glucose, galactose and lactose) stops the symptoms. Consistent with these observations, SGLT1−/− mice die within 2 days after weaning when they received a standard 58% carbohydrate-containing diet. Mortality can be rescued by feeding a glucose-galactose–free diet.9 There are ~300 GGM known cases worldwide, with around 50% of them resulting from familial intermarriage.31

The effect of diabetes on intestinal SGLT1 expression is incompletely understood. Some studies found that intestinal SGLT1 expression and glucose transport are increased in response to streptozotocin-induced T1DM in rodents.32,33,34,35 In contrast, db/db mice (hyperleptinemic), a well-established mouse model of T2DM, show significantly reduced intestinal SGLT1 expression; whereas ob/ob mice (aleptinemic), also a T2DM model, show no changes in SGLT1 expression.36 Consequently, db/db mice show reduced blood glucose excursions in response to oral glucose tolerance tests and treatment with the SGLT1/2 inhibitor phlorizin did not further reduce blood glucose excursions and were not different from SGLT1−/− mice.27,36 SGLT1 abundance in db/db mice is possibly reduced via activation of the leptin receptor isoform A (LEPRa). Further studies are needed to study the usefulness of intestinal SGLT1 inhibition in hyperleptinemic obese patients.

Development of SGLT inhibitors

Based on the above rationale, inhibiting renal glucose reabsorption and/or intestinal glucose absorption has been an interesting approach to target hyperglycemia. The first SGLT inhibitors to be discovered/developed were the O-glucosides phlorizin and T-1095.37 In 1835, chemists discovered phlorizin, a molecule from the root bark, leaves, shoots and fruit of the apple tree. Phlorizin was initially thought to cure malaria and infectious diseases because of its bitter taste; however, it was never used for these indications. Instead, it was found to increase urinary glucose excretion. The first description of its renal effects dates back to 1886, when Joseph von Mering, a German physician, first described a transient glucosuria.38 Homer W. Smith later described the glucosuric effect in healthy volunteers in a more scientifically rigorous approach.39 Consecutive studies in insulin resistant diabetic rats identified that subcutaneous administration of phlorizin normalized plasma glucose profiles and insulin sensitivity.40,41 Even given these beneficial effects, phlorizin was not a candidate to be developed into a clinical drug because of its poor solubility, limited bioavailability (~10%),42 and its only ~6-fold higher selectivity for SGLT2 versus SGLT1. A different compound, called T-1095,37 overcame some of these limitations and was possibly the first SGLT inhibitor that was developed. T-1095 is a pro-drug that acts as a SGLT1 inhibitor in the intestine. Once it is absorbed into the bloodstream, T-1095 is converted into the active drug (T-1095A) which consequently inhibits renal SGLT2, resulting in glucosuria.37 However, due to its non-selective nature and safety concerns, T-1095 was not further developed into a clinical drug.

Subsequent efforts led to the development of the selective SGLT2 inhibitors dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin, all of which contain C-glucoside linkage in lieu of O-glucoside linkage, making the molecules resistant to hydrolysis by β-glucosidase and increasing their half-life.34,43–45 The C-glucoside-containing SGLT2 inhibitors vary in their selectivity for SGLT2 over SGLT1 (Table 1); however, their potency, protein binding and half-life are all comparable.34,46 Recently, a novel antisense compound ISIS388626 was developed to increase glucose excretion by inhibiting SGLT2 mRNA expression. However, the study was halted early because subcutaneous administration in healthy volunteers caused substantial increases in serum creatinine that were accompanied by increased urinary excretion of beta‐2‐microglobulin and kidney-injury molecule 1, both kidney injury markers.47 Further preclinical studies are needed to address the safety of this compound.

More recently, there has been efforts to develop dual SGLT1/2 and selective SGLT1 inhibitors. Sotagliflozin (Zynquista®), is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor; sotagliflozin only has ~20-fold higher potency for SGLT2 versus SGLT1 (Table 1).48 Another compound, LIK066 (licogliflozin), is a dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor that shows favorable aspects on metabolic hormone profiles, with increased GLP-1, PYY and glucagon levels and reduced GIP, insulin and blood glucose levels (for physiological aspects of these effects, see section on intestinal SGLT1 inhibition). Further, a ~6% body weight reduction was observed in dysglycemic obese patients treated with licogliflozin compared to placebo.49 Current Phase II clinical trials with licogliflozin are underway for metabolic disorders such as obesity (NCT03100058) and polycystic ovary syndrome in obese women (NCT03152591).

In regard to selective SGLT1 inhibition, several compounds have been developed. Mizagliflozin (also known as DSP-3235, KGA-3235 or GSK-1614235), currently the most selective SGLT1 inhibitor, is ~300-times more selective for SGLT1 over SGLT2. Mizagliflozin is considered a non-absorbable intestinal SGLT1 specific inhibitor; it shows a very low bioavailability (F=0.02%) without any notable accumulation in tissues.50 Current clinical trials are investigating the use of mizagliflozin as a potential candidate to improve functional constipation (due to its ability to increase luminal glucose and water content).51,52 In addition, newly developed non-absorbable SGLT1 inhibitors include LX276153 and TP043883654 (Table 1). Both compounds significantly reduced blood glucose excursions in response to oral glucose tolerance tests in rodents.

When considering a drug to lower blood glucose levels in T1DM and T2DM, one must consider the risk of hypoglycemia, since episodes of hypoglycemia can impair cardioprotective effects, an effect partially caused by activation of the sympathetic nervous system.55 Fortunately, the risk of hypoglycemia during treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors is low except for patients simultaneously treated with sulfonylureas or insulin.56 The reason for this might be several-fold, but possibly relates to (i) compensation of SGLT1 in the late S2 and S3 segments, and (ii) counterregulation by endogenous hepatic glucose production.5

To date, major clinical trials that have evaluated the effectiveness of the selective SGLT2 inhibitors canagliflozin57, dapagliflozin58 and empagliflozin59,60 for the treatment of T2DM. The incidence of heart failure with canagliflozin and empagliflozin was reduced by ~35% and therefore surpassed the requisite safety parameters57,59–63. Dapagliflozin did not affect the rate of major cardiovascular events compared to placebo but did result in a lower rate of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure.58 What may constitute these cardioprotective mechanisms? In addition to their glucosuric effect, the gliflozins also show diuretic and natriuretic effects; both of which can contribute to reducing volume overload, decreasing blood pressure and aid to reduce body weight.64,65 However, the factors leading to cardiovascular benefits might be multifaceted. Reducing volume overload and decreasing blood pressure will improve ventricle loading conditions, preload and afterload, respectively.66,67 SGLT2 inhibitors possibly have a positive effect on cardiac energy metabolism. This could lead to improved myocardial energetics and substrate efficiency, which consequently could improve cardiac efficiency and cardiac output.68,69 A novel link between SGLT2 and sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 1 in the heart has been postulated to reduce cytoplasmic Na+ and Ca2+,70 both early hallmarks and drivers of cardiovascular death and heart failure,71 thus offering cardioprotection. This finding is of particular interest considering that SGLT2 is not expressed in the myocardium. At later stages of disease, after fibrosis has developed, dapagliflozin was shown to have antifibrotic effects via suppression of collagen synthesis by increasing the activation of M2 macrophages subsequently inhibiting myofibroblast differentiation.72 Lastly, altered paracrine regulation of adipokines has been implicated in the genesis of heart failure.73 Possibly as a consequence of weight reduction, 64,65 canagliflozin reduced plasma leptin and adiponectin levels which could contribute to a reduction of inflammation and fibrosis.62

Additional renal beneficial effects included reductions in albuminuria and a lesser decline in estimated GFR. What about the effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibition in diabetic patients with CKD? As one might expect, the improvement of glycemic control in response to SGLT2 inhibition is attenuated because of the reduced absolute filtered glucose load. Despite this, the cardioprotective and blood pressure lowering effects of SGLT2 inhibitors are preserved in patients with CKD and reduced eGFR.61,74

Renal SGLT1 inhibition: What does it add?

Under normoglycemic conditions, renal SGLT1 contributes to ~3% of FGR (Figure 1). Notably, under conditions of hyperglycemia or during SGLT2 inhibition, this contribution can increase substantially (up to 40–50%) when more glucose is delivered to the late proximal tubule. Despite the fact that SGLT2 normally contributes to >90% of FGR, pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of SGLT2 in patients75–77 and mice9,11 showed that FGR is only reduced to ~40–50%. This is the consequence of a compensatory role of SGLT1 in the late proximal tubule.11 Studies in knockout mice allowed us to estimate that the basal overall glucose reabsorption capacities for SGLT2 versus SGLT1 in a non-diabetic mouse kidney is in the range of 3:1–5:1.78 Based on these observations, with regard to lowering blood glucose levels, simultaneously blocking SGLT1 and SGLT2 in the kidney could be advantageous compared to only inhibiting SGLT2.79 As discussed in the following section, SGLT1 inhibition would greatly impact intestinal glucose absorption, and the renal effects would be expected to be additive to the intestinal effects. The risk for hypoglycemia was found to be lower in patients with T1DM treated with insulin and dual SGLT1/2 inhibition.80–82 If this relates to increased hepatic gluconeogenesis83,84 or the observed reduction in the daily required insulin dose80–82 remains to be determined. The expected stronger diuretic effect could place patients at greater risk of hypotension, pre-renal failure, and complications from hemoconcentration and diabetic ketoacidosis.85 If the greater risk for hypotension leads to falls and consequently fractures, the latter observed with canagliflozin treatment,86 remains to be determined. Preliminary data in a mouse model of acute kidney injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion showed that lack of SGLT1 (SGLT1−/− mice) improved kidney recovery, unraveling a role of SGLT1 for outer medullary integrity.87 Consequently, at least in terms of SGLT2 inhibitor-induced AKI,88 concomitant SGLT1 inhibition might reduce this potential risk.

Intestinal SGLT1 inhibition: What does it add?

Selective SGLT1 inhibition has been shown to delay post-prandial intestinal glucose absorption and enhance plasma levels of GLP-1 and GIP in healthy volunteers,89,90 normal mice,91 and diabetic rodents.92 GLP-1 receptor agonists are an approved treatment for T2DM, so it is of great importance that SGLT1 inhibition leads to increased GLP-1 levels. Why is GLP-1 beneficial in diabetes? Pancreatic β-cells are stimulated by GLP-1 to increase insulin secretion93 while diminishing glucagon secretion; additionally, GLP-1 decreased appetite and increased β-cell mass in preclinical studies.94 These effects are responsible for the anti-hyperglycemic effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists.56 Along those lines, studies in SGLT1−/− mice have shown an attenuated secretion of GLP-1 in response to a glucose bolus.9,95 Additionally, SGLT1−/− mice show abnormal pancreatic islet (cyto)morphology associated with impaired insulin and glucagon release capacity,96 thus, SGLT1 appears to be required for normal β- and α-cell function. Interestingly, a recent randomized trial in T2DM patients showed that treatment with canagliflozin, a selective SGLT2 inhibitor, increased plasma GLP-1 levels when administered before meals.97 Even though canagliflozin is ~260-fold more selective for SGLT2 than SGLT1 (Table 1), it was reported to inhibit intestinal glucose absorption because concentrations in the intestinal lumen reached 10-times the IC50 of SGLT1.92 Thus, given at high doses, canagliflozin may serve as a dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor and have both direct and indirect effects related to blocking intestinal SGLT1. Further supporting this, canagliflozin significantly increased cecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in mice with CKD, suggesting increased bacterial carbohydrate fermentation in the intestine.98 Of note, canagliflozin’s SGLT1 inhibitory action might not only be found in the intestine. SGLT1 is expressed in pancreatic α cells and regulates glucagon secretion.83 Canagliflozin, in contrast to dapagliflozin, was found to inhibit glucagon secretion in diabetic mice99 and T2DM patients.100

Inevitably, blocking glucose transport in the upper small intestine will lead to a greater glucose delivery to further distal segments of the small intestine and colon.53,89,92,95 It has been speculated that the gut microbiome metabolizes glucose in the colon to form SCFA, which bind to free fatty acid receptors (FFAR2/3) on distal small intestine L cells and may promote sustained GLP-1 release. However, a recent study identified that colonic GLP-1 can be released in response to SCFA without activating FFAR2/3.101 In regard to the gut microbiome, recent evidence suggests the gut dysbiosis contributes to the pathogenesis of T2DM.102 Studies have shown compositional and functional differences in the gut bacteria of pre-diabetic and T2DM patients compared to healthy individuals.103–105 As such, one might expect that changes in distal intestinal luminal glucose concentration as a result of SGLT1 inhibition might alter the gut microbiome. Surprisingly, treatment with a dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor did not affect relative abundance of bacterial orders or bacteria of interest in diabetic rodents.106 In contrast, in an adenine-induced CKD mouse model, 2-week canagliflozin treatment significantly altered microbiota composition in CKD mice.98 More studies are needed to better understand the role of SGLT1 and/or 2 inhibition on changes in gut microbiota.

As mentioned previously, lack of SGLT1 leads to GGM, and consequential osmotic diarrhea, dehydration, and metabolic acidosis. Based on this, one would expect that treatment with SGLT1 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors would lead to gastrointestinal side effects such as diarrhea due to the increase in luminal glucose and water. Surprisingly, the selective SGLT1 inhibitor mizagliflozin and the dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor sotagliflozin can be taken orally at doses that measurably inhibit intestinal glucose uptake but do not cause severe gastrointestinal side effects.89,107 However, the inTandem3 trial which looked at the net benefit of sotagliflizon versus placebo in T1DM did show that diarrhea occurred in 4.1% of the patients treated with sotagliflozin versus 2.3% in the placebo group, and even led to discontinuation in 0.4% of the patients treated with sotagliflozin versus 0% in the placebo group.82 If the composition of the microbiome contributes to the severity of intestinal side effects remains to be determined. However, the increase in luminal glucose and water as a result of SGLT1 inhibition may be enough to soften stools and improve constipation. As mentioned in a previous section, clinical studies are currently studying the use of mizagliflozin for the treatment of functional constipation.51,52 Of note, mizagliflozin increased plasma GLP-1 levels, which in addition to the incretin response, has been shown to ameliorate abdominal pain; thus, warranting further study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation.52

Taken together, intestinal inhibition of SGLT1 has multiple effects on glucose homeostasis: (i) directly by inhibiting glucose transport and (ii) indirectly by inducing a prolonged increase of GLP-1 and possibly GIP release (Figure 1). SGLT1 inhibition offers the possibility to enhance the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors or may have its own separate indications for the treatment of other diseases, e.g. constipation, obesity or polycystic ovary syndrome. In any case, long-term studies are needed to better determine their intestinal responses and safety.

SGLT1 inhibition beyond the kidney and intestine

Beyond the kidney and intestine, SGLT1 is expressed in salivary glands, liver, pancreatic alpha cells, lung, heart, skeletal muscle, and brain.6 The role of SGLT1 at many of these sites, as well as the consequences of SGLT1 inhibition, are poorly understood. A recent study, by using a Mendelian randomization strategy, showed that SGLT1 blockade should decrease the incidence of heart failure.108 Regarding the role of cardiac SGLT1, several mechanisms, including but not limited to, sodium influx replenishing ATP stores, glycogen accumulation, generation of reactive oxygen species and toxic accumulation of calcium have been speculated to contribute to SGLT1’s role in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. SGLT1 is significantly upregulated in cardiac ischemia and hypertrophy109,110 and SGLT2 has been postulated to be involved in the progression of diabetic cardiomyopathy.111 Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) was shown to be part of the involved signaling pathways; however, the data are ambiguous. Some studies showed that AMPK attenuated pressure overload or diabetes-related cardiac remodeling,112,113 while others showed that activated AMPK resulted in increased SGLT1 expression, which has been reported to promote myocardial ischemia and hypertrophy.109 Further, SGLT1 might be triggering reactive oxygen species generation and/or the accumulation of glycogen in cardiomyocytes, both potentially protective against ischemia reperfusion injury by refilling ATP stores in ischemic cardiac tissues by enhancing glucose availability. In contrast to these beneficial effects, another study found that dual SGLT1/2 inhibition with T-1095 in rats resulted in an exacerbation of cardiac dysfunction in response to myocardial infarction.114 In the brain, inhibiting or down-regulating SGLT1 was shown to be beneficial for early treatment of traumatic brain injury.115 As originally described in the CANVAS trial,57 canagliflozin had an increased risk of below knee amputations. A more recent study by Udell et al. showed a ~2-fold higher risk of amputation when the SGLT2 inhibitor cohort included canagliflozin, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin.116 The reason for the increased amputation risk remains elusive and could be either a direct SGLT2 inhibitory or off-target effect. Either of them could lead to susceptibility to trauma because of neuropathy, macro- and microvascular dysfunction-induced ischemia, infection and/or impaired wound healing. Another serious side effect that has recently been reported was the occurrence of Fournier’s gangrene, a most severe and potentially fatal genital infection, in patients treated with empagliflozin117 and dapagliflozin.118

While inhibition of SGLT1 merits evaluation for its therapeutic potential in diabetes and other conditions (e.g. heart and brain), it is obvious that there is need for a more mechanistic understanding of its function and the potential detrimental consequences associated with SGLT1 inhibition.

Perspectives

The usefulness of selective SGLT1 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibition will need to be confirmed in large clinical outcome trials. In terms of T1DM, selective SGLT2 and dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors are currently being tested in T1DM patients as add on to insulin. Since protective effects have already been reported in T2DM,119 it is not surprising that these compounds similarly improved glycemic control.82,120–122 However, it is concerning that there is a greater incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis.80–82,123 Since these inhibitors do not require a diabetic condition to be present to unveil their effects on glomerular filtration rate, and the body’s volume homeostasis,5 these inhibitors are being tested in CKD and heart failure patients.124

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors were supported by NIH grant 1R01DK110621 (TR).

Abbreviations:

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AngII

angiotensin II

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- eGFR

estimated GFR

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GGM

glucose galactose malabsorption

- GIP

glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLUT2

facilitative glucose transporter

- FGR

fractional glucose reabsorption

- FRG

familial renal glucosuria

- SCFA

short chain fatty acids

- SGLT

sodium glucose cotransporter

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Laakso M Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes from population to man to mechanisms: the Kelly West Award Lecture 2008. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawwas GK, Smith SM, Park H. Cardiovascular outcomes of sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallon V, Thomson SC. Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia. 2017;60(2):215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song P, Onishi A, Koepsell H, Vallon V. Sodium glucose cotransporter SGLT1 as a therapeutic target in diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20(9):1109–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis VW, Brazy PC. Phosphate and glucose transport in the proximal convoluted tubule: mutual dependency on sodium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1978;103:79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer SC, Pardridge WM, Hirayama BA, Wright EM. Colocalization of GLUT2 glucose transporter, sodium/glucose cotransporter, and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in rat kidney with double-peroxidase immunocytochemistry. Diabetes. 1992;41(6):766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorboulev V, Schurmann A, Vallon V, et al. Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes. 2012;61(1):187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horikawa YT, Panneerselvam M, Kawaraguchi Y, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of caveolin-3 attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and increases natriuretic peptide expression and signaling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(22):2273–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rieg T, Masuda T, Gerasimova M, et al. Increase in SGLT1-mediated transport explains renal glucose reabsorption during genetic and pharmacological SGLT2 inhibition in euglycemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(2):F188–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrhovac I, Balen Eror D, Klessen D, et al. Localizations of Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporters SGLT1 and SGLT2 in human kidney and of SGLT1 in human small intestine, liver, lung, and heart. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467(9):1881–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeFronzo RA, Davidson JA, Del Prato S. The role of the kidneys in glucose homeostasis: a new path towards normalizing glycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogensen CE, Andersen MJ. Increased kidney size and glomerular filtration rate in early juvenile diabetes. Diabetes. 1973;22(9):706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson SC, Deng A, Bao D, Satriano J, Blantz RC, Vallon V. Ornithine decarboxylase, kidney size, and the tubular hypothesis of glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(2):217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigalleau V, Garcia M, Lasseur C, et al. Large kidneys predict poor renal outcome in subjects with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2010;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallon V, Rose M, Gerasimova M, et al. Knockout of Na-glucose transporter SGLT2 attenuates hyperglycemia and glomerular hyperfiltration but not kidney growth or injury in diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304(2):F156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallon V, Gerasimova M, Rose MA, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin reduces renal growth and albuminuria in proportion to hyperglycemia and prevents glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetic Akita mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(2):F194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang XX, Luo Y, Wang D, et al. A dual agonist of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and the G protein-coupled receptor TGR5, INT-767, reverses age-related kidney disease in mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(29):12018–12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton L, Shannon CE, Fourcaudot M, et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter (SGLT) and glucose transporter (GLUT) expression in the kidney of type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(9):1322–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solini A, Rossi C, Mazzanti CM, Proietti A, Koepsell H, Ferrannini E. Sodium-glucose co-transporter (SGLT)2 and SGLT1 renal expression in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(9):1289–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahmoune H, Thompson PW, Ward JM, Smith CD, Hong G, Brown J. Glucose transporters in human renal proximal tubular cells isolated from the urine of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3427–3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hjarne U A Study of Orthoglycaemic Glycosuria with Particular Reference to its Hereditability. Acta Med Scand. 1927;67(5/6):495–571. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santer R, Calado J. Familial renal glucosuria and SGLT2: from a mendelian trait to a therapeutic target. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright EM, Loo DD, Hirayama BA. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):733–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceriello A Postprandial hyperglycemia and diabetes complications: is it time to treat? Diabetes. 2005;54(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roder PV, Geillinger KE, Zietek TS, Thorens B, Koepsell H, Daniel H. The role of SGLT1 and GLUT2 in intestinal glucose transport and sensing. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E. Apical GLUT2: a major pathway of intestinal sugar absorption. Diabetes. 2005;54(10):3056–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriya R, Shirakura T, Ito J, Mashiko S, Seo T. Activation of sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 ameliorates hyperglycemia by mediating incretin secretion in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(6):E1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindquist B, Meeuwisse GW. Chronic diarrhoea caused by monosaccharide malabsorption. Acta Paediatr. 1962;51:674–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turk E, Zabel B, Mundlos S, Dyer J, Wright EM. Glucose/galactose malabsorption caused by a defect in the Na+/glucose cotransporter. Nature. 1991;350(6316):354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyamoto K, Hase K, Taketani Y, et al. Diabetes and glucose transporter gene expression in rat small intestine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181(3):1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogata H, Seino Y, Harada N, et al. KATP channel as well as SGLT1 participates in GIP secretion in the diabetic state. J Endocrinol. 2014;222(2):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grempler R, Thomas L, Eckhardt M, et al. Empagliflozin, a novel selective sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor: characterisation and comparison with other SGLT-2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujita Y, Kojima H, Hidaka H, Fujimiya M, Kashiwagi A, Kikkawa R. Increased intestinal glucose absorption and postprandial hyperglycaemia at the early step of glucose intolerance in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty Rats. Diabetologia. 1998;41(12):1459–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dominguez Rieg JA, Chirasani VR, Koepsell H, Senapati S, Mahata SK, Rieg T. Regulation of intestinal SGLT1 by catestatin in hyperleptinemic type 2 diabetic mice. Lab Invest. 2016;96(1):98–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oku A, Ueta K, Arakawa K, et al. T-1095, an inhibitor of renal Na+-glucose cotransporters, may provide a novel approach to treating diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48(9):1794–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Mering J Ueber künstliche Diabetes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Membr Transp Signal. 1885;23/30(8):529–544. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chasis H, Jolliffe N, Smith HW. The Action of Phlorizin on the Excretion of Glucose, Xylose, Sucrose, Creatinine and Urea by Man. J Clin Invest. 1933;12(6):1083–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossetti L, Smith D, Shulman GI, Papachristou D, DeFronzo RA. Correction of hyperglycemia with phlorizin normalizes tissue sensitivity to insulin in diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1987;79(5):1510–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossetti L, Shulman GI, Zawalich W, DeFronzo RA. Effect of chronic hyperglycemia on in vivo insulin secretion in partially pancreatectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(4):1037–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crespy V, Aprikian O, Morand C, et al. Bioavailability of phloretin and phloridzin in rats. J Nutr. 2001;131(12):3227–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi CI. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors from Natural Products: Discovery of Next-Generation Antihyperglycemic Agents. Molecules. 2016;21(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isaji M SGLT2 inhibitors: molecular design and potential differences in effect. Kidney Int Suppl. 2011(120):S14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tahrani AA, Barnett AH. Dapagliflozin: a sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor in development for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2010;1(2):45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheen AJ. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Clinical Use of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(7):691–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Meer L, van Dongen M, Moerland M, de Kam M, Cohen A, Burggraaf J. Novel SGLT2 inhibitor: first-in-man studies of antisense compound is associated with unexpected renal effects. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017;5(1):e00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lapuerta P, Zambrowicz B, Strumph P, Sands A. Development of sotagliflozin, a dual sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1/2 inhibitor. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(2):101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.HE Y, HAYNES WG, MEYERS CD, et al. LIK066, a Dual SGLT1/2 Inhibitor, Reduces Weight and Improves Multiple Incretin Hormones in Clinical Proof-of-Concept Studies in Obese Patients With or Without Diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67(Supplement 1). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohno H, Kojima Y, Harada H, Abe Y, Endo T, Kobayashi M. Absorption, disposition, metabolism and excretion of [(14)C]mizagliflozin, a novel selective SGLT1 inhibitor, in rats. Xenobiotica. 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoue T, Takemura M, Fushimi N, et al. Mizagliflozin, a novel selective SGLT1 inhibitor, exhibits potential in the amelioration of chronic constipation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;806:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fukudo S, Endo Y, Hongo M, et al. Safety and efficacy of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 inhibitor mizagliflozin for functional constipation: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(9):603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodwin NC, Ding ZM, Harrison BA, et al. Discovery of LX2761, a Sodium-Dependent Glucose Cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) Inhibitor Restricted to the Intestinal Lumen, for the Treatment of Diabetes. J Med Chem. 2017;60(2):710–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuroda S, Kobashi Y, Oi T, et al. Discovery of a potent, low-absorbable sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) inhibitor (TP0438836) for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28(22):3534–3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khunti K, Davies M, Majeed A, Thorsted BL, Wolden ML, Paul SK. Hypoglycemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in insulin-treated people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(2):316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1696–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE, et al. Empagliflozin and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Established Cardiovascular Disease, and Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation. 2018;137(2):119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Packer M Do sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors prevent heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction by counterbalancing the effects of leptin? A novel hypothesis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(6):1361–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bailey CJ, Marx N. Cardiovascular protection in type 2 diabetes: Insights from recent outcome trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inzucchi SE, Zinman B, Wanner C, et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk: proposed pathways and review of ongoing outcome trials. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(2):90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zaccardi F, Webb DR, Htike ZZ, Youssef D, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Efficacy and safety of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(8):783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verma S, McMurray JJV, Cherney DZI. The Metabolodiuretic Promise of Sodium-Dependent Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibition: The Search for the Sweet Spot in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(9):939–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sattar N, McLaren J, Kristensen SL, Preiss D, McMurray JJ. SGLT2 Inhibition and cardiovascular events: why did EMPA-REG Outcomes surprise and what were the likely mechanisms? Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferrannini E, Mark M, Mayoux E. CV Protection in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial: A “Thrifty Substrate” Hypothesis. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(7):1108–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopaschuk GD, Verma S. Empagliflozin’s Fuel Hypothesis: Not so Soon. Cell Metab. 2016;24(2):200–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Wust RC, et al. Empagliflozin decreases myocardial cytoplasmic Na(+) through inhibition of the cardiac Na(+)/H(+) exchanger in rats and rabbits. Diabetologia. 2017;60(3):568–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, van Borren MM, Belterman CN, Coronel R, Fiolet JW. Increased Na+/H+-exchange activity is the cause of increased [Na+]i and underlies disturbed calcium handling in the rabbit pressure and volume overload heart failure model. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(4):1015–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee TM, Chang NC, Lin SZ. Dapagliflozin, a selective SGLT2 Inhibitor, attenuated cardiac fibrosis by regulating the macrophage polarization via STAT3 signaling in infarcted rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;104:298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel VB, Shah S, Verma S, Oudit GY. Epicardial adipose tissue as a metabolic transducer: role in heart failure and coronary artery disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22(6):889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petrykiv S, Sjostrom CD, Greasley PJ, Xu J, Persson F, Heerspink HJL. Differential Effects of Dapagliflozin on Cardiovascular Risk Factors at Varying Degrees of Renal Function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Komoroski B, Vachharajani N, Boulton D, et al. Dapagliflozin, a novel SGLT2 inhibitor, induces dose-dependent glucosuria in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(5):520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heise T, Seewaldt-Becker E, Macha S, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics following 4 weeks’ treatment with empagliflozin once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(7):613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sha S, Devineni D, Ghosh A, et al. Canagliflozin, a novel inhibitor of sodium glucose co-transporter 2, dose dependently reduces calculated renal threshold for glucose excretion and increases urinary glucose excretion in healthy subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(7):669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gallo LA, Wright EM, Vallon V. Probing SGLT2 as a therapeutic target for diabetes: basic physiology and consequences. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(2):78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Powell DR, DaCosta CM, Gay J, et al. Improved glycemic control in mice lacking Sglt1 and Sglt2. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(2):E117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buse JB, Garg SK, Rosenstock J, et al. Sotagliflozin in Combination With Optimized Insulin Therapy in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: The North American inTandem1 Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(9):1970–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Danne T, Cariou B, Banks P, et al. HbA1c and Hypoglycemia Reductions at 24 and 52 Weeks With Sotagliflozin in Combination With Insulin in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: The European inTandem2 Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(9):1981–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garg SK, Henry RR, Banks P, et al. Effects of Sotagliflozin Added to Insulin in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(24):2337–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Merovci A, Solis-Herrera C, Daniele G, et al. Dapagliflozin improves muscle insulin sensitivity but enhances endogenous glucose production. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferrannini E, Muscelli E, Frascerra S, et al. Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonora BM, Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and diabetic ketoacidosis: An updated review of the literature. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Usiskin K, et al. Effects of Canagliflozin on Fracture Risk in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(1):157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nespoux J, Patel R, Huang W, Koepsell H, Freeman B, Vallon V. Absence of the Na-Glucose Cotransporter SGLT1 Ameliorates Kidney Recovery in a Murine Model of Acute Kidney Injury. The FASEB Journal. 2018;32(1_supplement):849.845–849.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hahn K, Ejaz AA, Kanbay M, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Acute kidney injury from SGLT2 inhibitors: potential mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):711–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dobbins RL, Greenway FL, Chen L, et al. Selective sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1 inhibitors block glucose absorption and impair glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide release. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308(11):G946–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Polidori D, Sha S, Mudaliar S, et al. Canagliflozin lowers postprandial glucose and insulin by delaying intestinal glucose absorption in addition to increasing urinary glucose excretion: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2154–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee EY, Kaneko S, Jutabha P, et al. Distinct action of the alpha-glucosidase inhibitor miglitol on SGLT3, enteroendocrine cells, and GLP1 secretion. J Endocrinol. 2015;224(3):205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oguma T, Nakayama K, Kuriyama C, et al. Intestinal Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 1 Inhibition Enhances Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Secretion in Normal and Diabetic Rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354(3):279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ahn CH, Oh TJ, Kwak SH, Cho YM. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition improves incretin sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(2):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vilsboll T The effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on the beta cell. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11 Suppl 3:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Powell DR, Smith M, Greer J, et al. LX4211 increases serum glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY levels by reducing sodium/glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1)-mediated absorption of intestinal glucose. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345(2):250–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muhlemann M, Zdzieblo D, Friedrich A, et al. Altered pancreatic islet morphology and function in SGLT1 knockout mice on a glucose-deficient, fat-enriched diet. Mol Metab. 2018;13:67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takebayashi K, Hara K, Terasawa T, et al. Effect of canagliflozin on circulating active GLP-1 levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Endocr J. 2017;64(9):923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mishima E, Fukuda S, Kanemitsu Y, et al. Canagliflozin reduces plasma uremic toxins and alters the intestinal microbiota composition in a chronic kidney disease mouse model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;315(4):F824–F833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suga T, Kikuchi O, Kobayashi M, et al. SGLT1 in pancreatic alpha cells regulates glucagon secretion in mice, possibly explaining the distinct effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on plasma glucagon levels. Mol Metab. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kadowaki T, Inagaki N, Kondo K, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin as add-on therapy to teneligliptin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Results of a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(6):874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Christiansen CB, Gabe MBN, Svendsen B, Dragsted LO, Rosenkilde MM, Holst JJ. The impact of short-chain fatty acids on GLP-1 and PYY secretion from the isolated perfused rat colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;315(1):G53–G65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vrieze A, Holleman F, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Hoekstra JB, Nieuwdorp M. The environment within: how gut microbiota may influence metabolism and body composition. Diabetologia. 2010;53(4):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498(7452):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang X, Shen D, Fang Z, et al. Human gut microbiota changes reveal the progression of glucose intolerance. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Du F, Hinke SA, Cavanaugh C, et al. Potent Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter SGLT1/2 Dual Inhibition Improves Glycemic Control Without Marked Gastrointestinal Adaptation or Colonic Microbiota Changes in Rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;365(3):676–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zambrowicz B, Freiman J, Brown PM, et al. LX4211, a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor, improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(2):158–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Seidelmann SB, Feofanova E, Yu B, et al. Genetic Variants in SGLT1, Glucose Tolerance, and Cardiometabolic Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(15):1763–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Di Franco A, Cantini G, Tani A, et al. Sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLT) in human ischemic heart: A new potential pharmacological target. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banerjee SK, McGaffin KR, Pastor-Soler NM, Ahmad F. SGLT1 is a novel cardiac glucose transporter that is perturbed in disease states. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84(1):111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ye Y, Bajaj M, Yang HC, Perez-Polo JR, Birnbaum Y. SGLT-2 Inhibition with Dapagliflozin Reduces the Activation of the Nlrp3/ASC Inflammasome and Attenuates the Development of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Further Augmentation of the Effects with Saxagliptin, a DPP4 Inhibitor. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(2):119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ma ZG, Dai J, Zhang WB, et al. Protection against cardiac hypertrophy by geniposide involves the GLP-1 receptor / AMPKalpha signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(9):1502–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ma ZG, Yuan YP, Xu SC, et al. CTRP3 attenuates cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress and cell death in diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats. Diabetologia. 2017;60(6):1126–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Connelly KA, Zhang Y, Desjardins JF, Thai K, Gilbert RE. Dual inhibition of sodium-glucose linked cotransporters 1 and 2 exacerbates cardiac dysfunction following experimental myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sebastiani A, Greve F, Golz C, Forster CY, Koepsell H, Thal SC. RS1 (Rsc1A1) deficiency limits cerebral SGLT1 expression and delays brain damage after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2018;147(2):190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Udell JA, Yuan Z, Rush T, Sicignano NM, Galitz M, Rosenthal N. Cardiovascular Outcomes and Risks After Initiation of a Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor: Results From the EASEL Population-Based Cohort Study (Evidence for Cardiovascular Outcomes With Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Real World). Circulation. 2018;137(14):1450–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kumar S, Costello AJ, Colman PG. Fournier’s gangrene in a man on empagliflozin for treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34(11):1646–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm617360.htm.

- 119.Fattah H, Vallon V. The Potential Role of SGLT2 Inhibitors in the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes.. Drugs. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sands AT, Zambrowicz BP, Rosenstock J, et al. Sotagliflozin, a Dual SGLT1 and SGLT2 Inhibitor, as Adjunct Therapy to Insulin in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1181–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dandona P, Mathieu C, Phillip M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in patients with inadequately controlled type 1 diabetes (DEPICT-1): 24 week results from a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(11):864–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Henry RR, Thakkar P, Tong C, Polidori D, Alba M. Efficacy and Safety of Canagliflozin, a Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor, as Add-on to Insulin in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2258–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pieber TR, Famulla S, Eilbracht J, et al. Empagliflozin as adjunct to insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes: a 4-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (EASE-1). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(10):928–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Heerspink HJ, Desai M, Jardine M, Balis D, Meininger G, Perkovic V. Canagliflozin Slows Progression of Renal Function Decline Independently of Glycemic Effects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ohtake Y, Sato T, Kobayashi T, et al. Discovery of tofogliflozin, a novel C-arylglucoside with an O-spiroketal ring system, as a highly selective sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2012;55(17):7828–7840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Suzuki M, Honda K, Fukazawa M, et al. Tofogliflozin, a potent and highly specific sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, improves glycemic control in diabetic rats and mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341(3):692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA, Norton L. Novel hypothesis to explain why SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit only 30–50% of filtered glucose load in humans. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3324–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mascitti V, Maurer TS, Robinson RP, et al. Discovery of a clinical candidate from the structurally unique dioxa-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane class of sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2011;54(8):2952–2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kakinuma H, Oi T, Hashimoto-Tsuchiya Y, et al. (1S)-1,5-anhydro-1-[5-(4-ethoxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-4-methylphenyl]-1-thio-D-glucito l (TS-071) is a potent, selective sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for type 2 diabetes treatment. J Med Chem. 2010;53(8):3247–3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Samukawa Y, Mutoh M, Chen S, Mizui N. Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Luseogliflozin, a Sodium Glucose Co-transporter 2 Inhibitor, in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40(8):1207–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Meng W, Ellsworth BA, Nirschl AA, et al. Discovery of dapagliflozin: a potent, selective renal sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2008;51(5):1145–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hummel CS, Lu C, Liu J, et al. Structural selectivity of human SGLT inhibitors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(2):C373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kuriyama C, Xu JZ, Lee SP, et al. Analysis of the effect of canagliflozin on renal glucose reabsorption and progression of hyperglycemia in zucker diabetic Fatty rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351(2):423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nomura S, Sakamaki S, Hongu M, et al. Discovery of canagliflozin, a novel C-glucoside with thiophene ring, as sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Chem. 2010;53(17):6355–6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Imamura M, Nakanishi K, Suzuki T, et al. Discovery of Ipragliflozin (ASP1941): a novel C-glucoside with benzothiophene structure as a potent and selective sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(10):3263–3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tahara A, Kurosaki E, Yokono M, et al. Pharmacological profile of ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, in vitro and in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385(4):423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nagata T, Suzuki M, Fukazawa M, et al. Competitive inhibition of SGLT2 by tofogliflozin or phlorizin induces urinary glucose excretion through extending splay in cynomolgus monkeys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(12):F1520–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Castaneda F, Burse A, Boland W, Kinne RK. Thioglycosides as inhibitors of hSGLT1 and hSGLT2: potential therapeutic agents for the control of hyperglycemia in diabetes. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4(3):131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tsujihara K, Hongu M, Saito K, et al. Na+-Glucose Cotransporter (SGLT) Inhibitors as Antidiabetic Agents. 4. Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of 4’-Dehydroxyphlorizin Derivatives Substituted on the B Ring. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1999;42(26):5311–5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Powell DR, Smith MG, Doree DD, et al. LX2761, a Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter 1 Inhibitor Restricted to the Intestine, Improves Glycemic Control in Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;362(1):85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]