Abstract

Background

Inflammation may contribute to preterm birth and to morbidity of preterm infants. Preterm infants are at risk for alterations in the normal protective microbiome. Oral probiotics administered directly to preterm infants have been shown to decrease the risk for severe necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) as well as the risk of death, but there are safety concerns about administration of probiotics directly to preterm infants. Through decreasing maternal inflammation, probiotics may play a role in preventing preterm birth and/or decreasing the inflammatory milieu surrounding delivery of preterm infants, and may alter the microbiome of the preterm infant when given to mothers during pregnancy. Probiotics given to mothers after birth of preterm infants may effect infant bacterial colonization, which could potentially reduce the incidence of NEC.

Objectives

1. To compare the efficacy of maternal probiotic administration versus placebo or no intervention in mothers during pregnancy for the prevention of preterm birth and the prevention of morbidity and mortality of infants born preterm.

2. To compare the efficacy of maternal probiotic administration versus placebo, no intervention, or neonatal probiotic administration in mothers of preterm infants after birth on the prevention of mortality and preterm infant morbidities such as NEC.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 2), MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 21 March 2017), Embase (1980 to 21 March 2017), and CINAHL (1982 to 21 March 2017). We also searched clinical trials databases, conference proceedings, and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomized controlled trials and quasi‐randomized trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials in the review if they administered oral probiotics to pregnant mothers at risk for preterm birth, or to mothers of preterm infants after birth. Quasi‐randomized trials were eligible for inclusion, but none were identified. Studies enrolling pregnant women needed to administer probiotics at < 36 weeks' gestation until the trimester of birth. Probiotics considered were of the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium or Saccharomyces.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration and Cochrane Neonatal to determine the methodologic quality of studies, and for data collection and analysis.

Main results

We included 12 eligible trials with a total of 1450 mothers and 1204 known infants. Eleven trials administered probiotics to mothers during pregnancy and one trial administered probiotics to mothers after birth of their preterm infants. No studies compared maternal probiotic administration directly with neonatal administration. Included prenatal trials were highly variable in the indication for the trial, the gestational age and duration of administration of probiotics, as well as the dose and formulation of the probiotics. The pregnant women included in these trials were overall at low risk for preterm birth. In a meta‐analysis of trial data, oral probiotic administration to pregnant women did not reduce the incidence of preterm birth < 37 weeks (typical risk ratio (RR) 0.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32 to 2.67; 4 studies, 518 mothers and 506 infants), < 34 weeks (typical risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; 2 studies, 287 mothers and infants), the incidence of infant mortality (typical RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; 2 studies, 309 mothers and 298 infants), or the gestational age at birth (mean difference (MD) 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.63; 2 studies, 209 mothers with 207 infants).

One trial studied administration of probiotics to mothers after preterm birth and included 49 mothers and 58 infants. There were no significant differences in the risk of any NEC (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.46; 1 study, 58 infants), surgery for NEC (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.58; 1 study, 58 infants), death (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.06 to 6.88; 1 study, 58 infants), and death or NEC (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.49; 1 study, 58 infants). There was an improvement in time to reach 50% enteral feeds in infants whose mothers received probiotics, but the estimate is imprecise (MD ‐9.60 days, 95% CI ‐19.04 to ‐0.16 days; 58 infants). No other improvement in any neonatal outcomes were reported. The estimates were imprecise and do not exclude the possibility of meaningful harms or benefits from maternal probiotic administration. There were no cases of culture‐proven sepsis with the probiotic organism. The GRADE quality of evidence was judged to be low to very low due to inconsistency and imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to conclude whether there is appreciable benefit or harm to neonates of either oral supplementation of probiotics administered to pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth or oral supplementation of probiotics to mothers of preterm infants after birth. Oral supplementation of probiotics to mothers of preterm infants after birth may decrease time to 50% enteral feeds, however, this estimate is extremely imprecise. More research is needed for post‐natal administration of probiotics to mothers of preterm infants, as well as to pregnant mothers at high risk for preterm birth.

Plain language summary

Maternal probiotic supplementation for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants

Review question Do probiotics given to pregnant women prior to delivery and/or probiotics given to mothers of premature babies after birth compared with administration of placebo, no intervention or postnatal administration of probiotics to premature babies themselves reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality in premature babies?

Background Inflammation may contribute to premature birth and to morbidity of premature babies. Premature babies are at risk for alterations in the growth of normal "good" bacteria in their intestinal tract. Probiotics are supplements of "good bacteria." Giving these bacteria directly to premature babies may decrease inflammation and decrease the risk for severe gastrointestinal disease (necrotizing enterocolitis) as well as the risk of death. However, there are safety concerns about administration of probiotics directly to premature babies.

Study characteristics Twelve eligible trials with a total of 1450 mothers and 1204 known infants were included from searches, up to date as of March 2017. Eleven trials gave probiotics to mothers during pregnancy and one trial gave probiotics to mothers after the birth of their preterm infants. No studies compared maternal probiotic administration directly versus neonatal administration.The studies of pregnant women focused on various aspects of the studies with different probiotics given at different times. The pregnant women included in these trials were overall at low risk for preterm birth. The one trial with mothers given probiotics after birth was to mothers of infants who weighed less than 1500 g at birth.

Key results There is insufficient evidence to conclude whether there is appreciable benefit or harm to neonates of either oral supplementation of probiotics administered to pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth or oral supplementation of probiotics to mothers of preterm infants after birth. There were no trials that gave mothers at high risk for having a premature infant probiotics, so the effects of probiotics given to those mothers is unknown. More studies are needed to know if probiotics given to mothers of preterm infants decreases death, necrotizing enterocolitis, or other problems related to prematurity.

Quality of evidence In general, the evidence was of low to very low quality due to imprecision (small sample sizes) and indirectness (enrolled mothers were not necessarily at high risk for delivering their babies early).

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The microbiome is defined as the genomes and gene products of microbes that live within and on humans (Johnson 2012). Under normal conditions the microbiome of an infant is established through exposure with bacteria both prenatally and postnatally. The placenta, amniotic fluid and meconium have their own microbiota that influences the microbiome of the infant. Postnatal influences of the microbiome come from exposures mainly from the maternal microbiome which includes exposure to vaginal, oral, fecal, skin and breast milk bacteria, with a typical predominance of protective Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in the neonatal period.

Preterm infants are at risk for alterations in the normal protective microbiome due their increased cesarean delivery rate, exposure to antibiotics, nosocomial exposures to pathogens, lack of typical skin contact with maternal flora, as well as alterations in typical exposure to breast milk (Cilieborg 2012). Cesarean delivery alters colonization of neonates so their stool has lower bifidobacteria and more skin flora such as Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium (Faa 2013). Maternal intrapartum antibiotics and antibiotics given to mothers with prolonged rupture of membranes are associated with lower transfer of Lactobacillus to the infant, and even antibiotics given days before birth have been shown to alter the premature infant microbiome with less bacterial diversity of the first stool samples (Faa 2013; Keski‐Nisula 2013). Antibiotics given in the neonatal period have also been associated with decreased stool bifidobacteria (Faa 2013). This may lead to delayed colonization with low diversity of bacteria as well as colonization with pathogens and bacterial overgrowth which put infants at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), sepsis and death in the neonatal period (Cilieborg 2012).

The development of NEC is typically associated with a dysregulation of inflammation in the gut that results in gas‐producing bacteria translocating through the bowel mucosa and is not usually caused by one single organism. It is a disorder that affects approximately 7% of infants with a birth weight of less than 1500 g, with a death rate of approximately 20% to 30% (Neu 2011). Strategies to prevent NEC have been employed including exclusive human milk diet, standardized feeding protocols, human milk fortifiers and postnatal probiotics, but prematurity and alterations of gut flora still put premature infants at risk.

Modifications of the neonatal microbiome may have long‐term effects on health that may last until adulthood. Altered microbiomes have been associated with the development of atopy (hereditary tendency to be hypersensitive to certain allergens), inflammatory bowel disease, obesity and impaired glucose regulation. It is unknown to what extent early preterm infant alterations in the microbiome may influence their lifelong risk for these diseases.

Description of the intervention

Probiotics are defined as living microorganisms that confer a health benefit to the host (Othman 2007); they are often given enterally to colonize the gastrointestinal tract. Typical probiotic bacteria administered are bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus or Saccharomyces (Dugoua 2009; Thomas 2010). They have been given directly to preterm infants with the intention to decrease the rate of NEC (AlFaleh 2014; Costeloe 2016; Deshpande 2010; Neu 2011), and there is emerging interest in promoting gastrointestinal colonization in preterm infants through administration of probiotics to their mothers instead of directly to infants. Probiotics have already been studied during pregnancy for other indications with the intention to treat genitourinary infections, prevent infant atopy, enhance metabolism and prevent preterm labor (Dugoua 2009; Gomez Arango 2015; Lahtinen 2009; Lindsay 2013; Reid 2003; VandeVusse 2013).

The focus of this investigation is the maternal oral administration of probiotics. Maternal probiotics can be administered to pregnant women at risk for preterm birth or to mothers of preterm infants after birth. Pregnant women administered probiotics in pregnancy will be compared to pregnant women receiving placebo or no intervention. Mothers of preterm infants administered probiotics after birth will be compared to either mothers of preterm infants administered placebo or no intervention, or to preterm neonates administered probiotics directly.

How the intervention might work

The microbiome of the pregnant and postpartum woman is influenced by the established microbiome, diet, probiotic exposures, and pregnancy itself as there are alterations of the microbiome that occur during pregnancy that are likely hormonally mediated. During pregnancy probiotics have been generally regarded as safe (Elias 2011; Gomez Arango 2015; Lindsay 2013), and beneficial for mothers in preventing and treating bacterial vaginitis, and reducing the risk of gestational diabetes, with hypotheses but no definitive evidence of their efficacy in preventing preterm birth (Gomez Arango 2015; Othman 2007). While studies have shown that probiotics taken by adults only change their microbiome while they are being taken, these short‐term alterations in maternal microbiome may have long‐term effects on establishment of the fetal and neonatal microbiome (Matamaros 2013).

Normal microbiome colonization occurs prenatally with bacteria found in the placenta, amniotic fluid and fetal meconium (Matamaros 2013), and postnatal colonization from the mother and environment, including vaginal Lactobacillus obtained at birth, maternal skin flora and bacteria in breast milk (Cilieborg 2012; Faa 2013). Especially predominant and beneficial to the healthy neonatal microbiome are lactobacilli and Bifidobacterium. Lactobacilli are facultative anaerobes that create an environment in which bifidobacteria, anaerobic gram‐positive bacilli, can colonize and predominate in the colon (Bergmann 2014; Dugoua 2009). These bacteria help maintain the mucosa of the intestines, prevent pathogens from colonizing the colon, modulate inflammation along the mucosa and activate the immune system (Hickey 2012), which may help to decrease the risk of NEC and subsequent development of sepsis.

Breast milk consumption greatly contributes to colonization of newborn infants. Studies have shown that there are more than 200 species of bacteria in human milk with a predominance of Lactobacillus and bifidobacteria in addition to Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and corynebacteria (Bergmann 2014). There is evidence that the neonatal gut microbiome reflects the bacteria found in breast milk and the mother’s stool (Bergmann 2014; Cilieborg 2012; Jost 2014). According to the theory of the entero‐mammary pathway, bacteria are deposited into the mammary milk ducts from the maternal gastrointestinal tract via active transport through the blood (Bergmann 2014; Jost 2014). Dendritic cells in the maternal gut lumen are thought to trap bacteria, and with the help of mononuclear cells, transport them through the blood to the breast (Bergmann 2014). This is thought to be hormonally mediated, occurring late in the third trimester, with the most bacteria present in the breast in the peripartum period (Bergmann 2014).

Studies have shown that lactobacilli taken orally by the mother are present in breast milk when taken prenatally and postnatally (Bergmann 2014). Supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri) during the third trimester prior to delivery resulted in a statistically significant increase in L reuteri in maternal colostrum (Abrahamsson 2009), and Lactobacillus GG taken by mothers for one month prior to delivery increased the diversity of fecal Bifidobacterium in neonates (Gueimonde 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Probiotic administration in high‐risk very low birth weight (VLBW) infants has been shown to reduce the incidence of NEC as well as mortality (AlFaleh 2014; Deshpande 2010). Postnatal probiotic administration decreased the risk of developing stage II‐III NEC by more than half (AlFaleh 2014). In their analysis, Deshpande and coworkers suggest that routine use be implemented without the need for more placebo‐controlled trials (Deshpande 2010).

However, the studies included in these meta‐analyses are quite heterogeneous in regards to the specie(s), dose, timing and duration of administration, and there is concern about safety and quality assurance of probiotics which lie outside the purview of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation. A recent systematic review cautions universal use of probiotics in VLBW infants citing the lack of evidence of efficacy for specific strains (Mihatsch 2012), while others in the neonatal community cite both methodologic and safety concerns as cautions against universal adoption (Garland 2010; Soll 2010). The American Academy of Pediatrics 2010 Clinical Report written by the Committee on Nutrition states that there is insufficient data to recommend probiotics in infants weighing less than 1000 g, and that since not all probiotics have been studied, they cannot all be generally recommended (Thomas 2010). The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition counsels caution in introducing potentially infectious agents to VLBW infants due to their immunologic immaturity, and states that there are not enough data to conclude that probiotic administration to preterm neonates is safe (Agostoni 2010). While there are many studies that suggest the safety of probiotics (AlFaleh 2014; Costeloe 2016), there have been cases of sepsis with the strains of probiotics given to preterm infants (Bertelli 2015), as well as a death due to gastrointestinal mucormycosis from Rhizopus oryzae‐contaminated probiotic directly administered to a preterm infant (CDC HAN 2014). With these emerging safety concerns, the FDA has issued a warning against the use of probiotics in immunocompromised patients (CDC 2015; FDA 2014).

These same safety concerns may not be universal where there are regulatory organizations responsible for overseeing the safety of probiotics, such as the Natural Health Products Directorate in Canada (Janvier 2013).

Currently, probiotic use in the VLBW population is not routine in many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in the USA. A recent survey of US NICUs that are members of Vermont Oxford Network showed that 14% of these NICUs give VLBW infants probiotics (Viswanathan 2016). Of these 14%, 8.8% of NICUs routinely give all VLBWs probiotics, while another 5.2% of NICUs give probiotics to select VLBW infants (Viswanathan 2016).

With these safety concerns regarding the direct administration of probiotics to preterm infants and evidence showing that probiotics given to preterm infants decreases the rate of NEC and mortality (AlFaleh 2014; Deshpande 2010), there is interest in alternate methods for inducing a normal microbiome in a safe manner. Since maternal flora and breast milk bacteria are known to be transmitted naturally to fetuses and neonates, an alternative method of exposure to probiotics that avoids direct administration to preterm infants, and therefore direct administration of possible contaminants, is maternal probiotic administration to mothers of preterm infants or pregnant women at risk for preterm birth. While not all species of probiotics or timing of administration within pregnancy have been studied thoroughly enough to make definitive statements about safety for all probiotics (Dugoua 2009), probiotics in pregnancy have been generally regarded as safe (Elias 2011; Gomez Arango 2015; Lindsay 2013).

Maternal probiotic administration in pregnancy for prevention of preterm labor and preterm birth has been addressed in one systematic Cochrane review focusing on probiotics specifically as a treatment or prevention of urogenital infections (Othman 2007). Our review will also address probiotic administration to pregnant women at risk of preterm birth, but its focus is on the preterm infant and includes pregnant women at risk for preterm birth for any reason. To our knowledge, this will be the first systematic review of maternal probiotic administration with a focus on mothers of preterm infants given probiotics after birth, the first to address the comparison of probiotics administered to mothers of preterm infants versus administration to the preterm infants themselves, and the first to address prenatal and postnatal probiotic administration to mothers at risk for preterm birth.

Objectives

To determine whether maternal probiotic administration to pregnant women and/or probiotic administration to mothers after preterm birth compared to administration of placebo, no intervention or postnatal administration to preterm infants reduces the risk of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants.

Comparisons

-

Probiotics administered to pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation) versus placebo or no intervention:

In pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation), maternal probiotics only prior to birth versus maternal placebo or no intervention prior to birth;

In pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation), maternal probiotics both prior to and after birth versus maternal placebo or no intervention prior to and after birth.

Probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants (< 37 weeks' gestation) versus maternal placebo or no intervention.

Probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants (< 37 weeks' gestation) versus neonatal probiotic administration.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials. Quasi‐randomized controlled trials, and cluster trials were eligible for inclusion but none were identified. Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Comparison 1: probiotics administered to pregnant women versus placebo or no intervention

Pregnant women at risk for preterm birth (birth at < 36 weeks' gestation).

Comparison 2: probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants versus maternal placebo or no intervention

Postpartum mothers who have given birth to a preterm infant born < 37 weeks' gestation.

Comparison 3: probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants versus neonatal probiotic administration

Postpartum mothers who have given birth to a preterm infant born < 37 weeks' gestation.

Newborn infants born < 37 weeks' gestation.

Types of interventions

Included probiotics included Lactobacillus species, Bifidobacterium species, or Saccharomyces, and mixed preparations of these probiotics at any dose with the intention to treat for a minimum of seven days.

For antenatal probiotic administration, probiotics were taken at some point during the trimester in which the mother gives birth, or within one week of birth if born early in the third trimester.

Types of outcome measures

Data on the mothers and the preterm infants of these mothers was collected.

Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

Gestational age at birth (limited to infants in Comparison 1).*

Early onset bacterial sepsis, defined by positive blood culture on 'day of life 3' or earlier (limited to infants in Comparison 1).

Late‐onset sepsis, defined by positive blood culture on 'day of life 3' or later.

Culture‐proven sepsis with supplemented probiotic(s) before hospital discharge.

Neonatal sepsis (at any time)*

Surgical NEC (Bell Stage III) (Bell 1978).*

For infants born < 37 weeks

Duration of hospital stay (days).

Duration of parenteral nutrition (days).

Days to full enteral feeds.

Days to 50% enteral feeds*

Growth (g/kg/day) during hospitalization (prior to discharge).

Growth Z score at 36 to 40 weeks' postmenstrual age (PMA).

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (any stage, severe stage 3 or greater) (ICCROP 2005).

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (any grade and severe (Grade III‐IV)) (Papile 1978).

Cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) (diagnosed by cranial imaging).

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (treated either medically or surgically).

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) assessed at 28 days and at 36 weeks' PMA.

Long‐term major neurodevelopmental disability assessed at 18 to 24 months in survivors (cerebral palsy (CP)), developmental delay (Bayley or Griffith assessment more than two standard deviations (SD) below the mean) or intellectual impairment (intelligence quotient (IQ) more than two SD below mean), blindness (vision < 6/60 in both eyes), sensorineural deafness requiring amplification) (Jacobs 2013).

Maternal secondary outcomes

Maternal chorioamnionitis: suspected or confirmed intrauterine inflammation or infection or both ("Triple I") based upon the criteria from the 2016 chorioamnionitis workshop Higgins 2016). Suspected Triple I is defined by a fever without a clear source plus baseline fetal tachycardia, maternal white blood count greater than 15,000/mm³ in the absence of corticosteroids or definite purulent fluid from the cervical os. Confirmed Triple I is defined as meeting criteria for suspected Triple I plus amniocentesis‐proven infection through a positive Gram stain, low glucose or positive amniotic fluid culture or placental pathology revealing diagnostic features of infection. For comparison 1 only.

Maternal endometritis: clinical diagnosis by obstetric provider consisting of an oral temperature of ≥ 38.0 °C on any two of the first 10 postpartum days or a temperature of ≥ 38.7 °C during the first 24 hours postpartum based upon the American Committee of Maternal Welfare's standard definition) (Mackeen 2015).

Maternal mastitis diagnosed clinically by obstetrics provider at any time during the study.

Maternal sepsis as defined by positive maternal blood culture and assessed at any time during the study.

Maternal Group B Streptococcus colonization (based upon most recent vaginal/rectal swab results prior to birth).

* outcome added post‐hoc after review of available study outcomes

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal Group search strategy for specialized register).

Electronic searches

We conducted a comprehensive search including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 21 March 2017); Embase (1980 to 21 March 2017); and CINAHL (1982 to 21 March 2017) using the following search terms: (probiotic OR lactobacillus OR bifidobacter* OR saccharomyces), plus database‐specific limiters for RCTs and neonates (see Appendix 1 for the full search strategies for each database). We did not apply language restrictions. We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization’s International Trials Registry and Platform www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/, and the ISRCTN Registry).

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Information Scientist (see Appendix 2).

Searching other resources

We searched the abstracts of the Society for Pediatric Research (US) (published in Pediatric Research) for the years 1985 to 1999 using the following key words: (probiotic OR lactobacillus OR bifidobacteria OR saccharomyces) AND (neonates OR infants).

We also searched for conference abstracts from Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS) and European Society for Paediatric Research (ESPR). We carried out searches in Abstracts to View (2000 to present) (www.abstracts2view.com/pasall/) and Pediatric Research as well as the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

We collected information regarding the method of randomization, blinding, drug intervention, stratification, and whether the trial was single or multicenter for each included study. We noted the information regarding trial participants including gestational age criteria, birth weight criteria, and other inclusion or exclusion criteria. We analyzed the information on clinical outcomes including death, severe NEC (Bell stage II or more), early onset sepsis (if probiotics were administered before delivery), late onset sepsis, prematurity (gestational age) (if probiotics were administered prior to delivery), culture‐proven sepsis with supplemented probiotic(s), duration of hospital stay (days), duration of parenteral nutrition (days), days to full enteral feeds, growth (g/kg/day), ROP (any, severe), IVH (Grade III‐IV), cystic PVL and PDA (treated either medically or surgically), chronic lung disease (CLD), and long‐term major neurodevelopmental disability. Maternal data collected included maternal chorioamnionitis, endometritis, mastitis and sepsis. We assessed the quality of evidence at the outcome level using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013).

Selection of studies

We assessed the titles and abstracts resulting from the electronic searches. The full copy of all relevant or potentially relevant trials was obtained and assessed according to the 'Criteria for considering studies for this review'.

We included randomized controlled trials fulfilling the selection criteria described in the previous section. We planned to include cluster‐randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials but none were identified. Cross‐over studies were not eligible for inclusion. Both superiority trials and non‐inferiority trials were eligible for inclusion. All review authors reviewed the results of the search and separately selected the studies for inclusion. Disagreements about whether a trial should be included were resolved by discussion and consensus was reached. In cases where additional information was needed before a decision could be made as to whether to include a trial, we planned to obtain this information from the study investigator.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted, assessed, and coded all data for each study, using a form designed specifically for this review. Any standard error (SE) of the mean was replaced by the corresponding standard deviation (SD). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. For each study, final data were entered into Review Manager 5 (RevMan) by one review author (JG) and then checked by the other review author (RS) (Review Manager 2014). If needed, we planned to contact authors of trials to obtain missing data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JG, RS) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011) for the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Any other bias

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third assessor. See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed the statistical analyses using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We analyzed categorical data using risk ratio (RR), and risk difference (RD). For statistically significant outcomes, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional participant with a beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional participant with a harmful outcome (NNTH). We analyzed continuous data using mean difference (MD) and the standardized mean difference (SMD). We reported the 95% confidence interval (CI) on all estimates.

Unit of analysis issues

Had we included any cluster‐randomized trials, we planned to use the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) to calculate effective sample sizes in an approximate analysis (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 15.3.4). Once trials had been changed to their effective sample size, we planned to enter the data into RevMan in a manner similar to how data from randomized control trials are entered.

Dealing with missing data

The review was analyzed using an intention‐to‐treat paradigm. For studies with missing data, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain this data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated the treatment effects of individual trials and examined heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I² statistic. We graded the degree of heterogeneity as: less than 25% — no heterogeneity; 25% to 49% — low heterogeneity; 50% to 75% — moderate heterogeneity; more than 75% — substantial heterogeneity. If statistical heterogeneity (an I² > 50%) was noted, the possible causes were explored (for example, differences in study quality, participants, intervention regimens, or outcome assessments).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to create a funnel plot if there were at least 10 studies meeting our inclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

If multiple studies were identified and thought to be sufficiently similar in participant population, intervention and outcomes, meta‐analysis was carried out using Review Manager 2014. For categorical outcomes, we calculated the typical estimates of RR and RD, each with its 95% CI; and for continuous outcomes the MD or a summary estimate for the MD, each with its 95% CI, was calculated. We used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. If meta‐analysis was judged to be inappropriate, we analyzed individual trials and interpreted them separately.

Quality of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: preterm birth (any preterm birth (< 37 weeks) and preterm birth < 34 weeks) (limited to infants in Comparison 1); severe NEC (Bell stage II or more) (Bell 1978); death (mortality before discharge); death or severe NEC; culture‐proven sepsis with supplemented probiotic(s) before hospital discharge; late‐onset sepsis, defined by positive blood culture on 'day of life 3' or later.

We added several clinically important outcomes to the 'Summary of findings' tables based on review of available studies post hoc: for Comparison 1: gestational age at birth (weeks); miscarriage/stillbirth; for Comparison 2: any NEC, surgery for NEC, feeding with more than 50% breast milk (days).

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of the outcomes listed above. We considered evidence from randomized controlled trials as high quality but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT GDT Guideline Development Tool to create ‘Summary of findings’ tables to report the quality of the evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence in one of four grades.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We examined the effect of differences in the definitions and measurement of outcomes, such as diagnosis of NEC and infections and differences in length of follow‐up using methods for addressing clinical heterogeneity: subgroup analysis and meta‐regression. If any other significant heterogeneity was detected between studies, we planned to carry out subgroup analysis and avoid pooling of results.

Subgroups for analysis

The following pre‐planned subgroup analyses were performed.

Probiotic type: Lactobacillus sp ecies, Bifidobacterium species, Saccharomyces, or mixed preparations of these probiotics

Economic country setting (low‐income, lower‐middle income, upper‐middle income and high‐income economies as defined by the World Bank (The World Bank 2016)

In addition, a post hoc subgroup analysis was performed based on maternal gestational age at enrollment.

There were insufficient data to perform subgroup analyses based upon birth weight, race, ethnicity, sex, provision of breast milk, and maternal risk for preterm birth.

Sensitivity analysis

Excluding studies with high risk of bias (performed).

Excluding unpublished studies (planned but not performed due to lack of data).

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies.

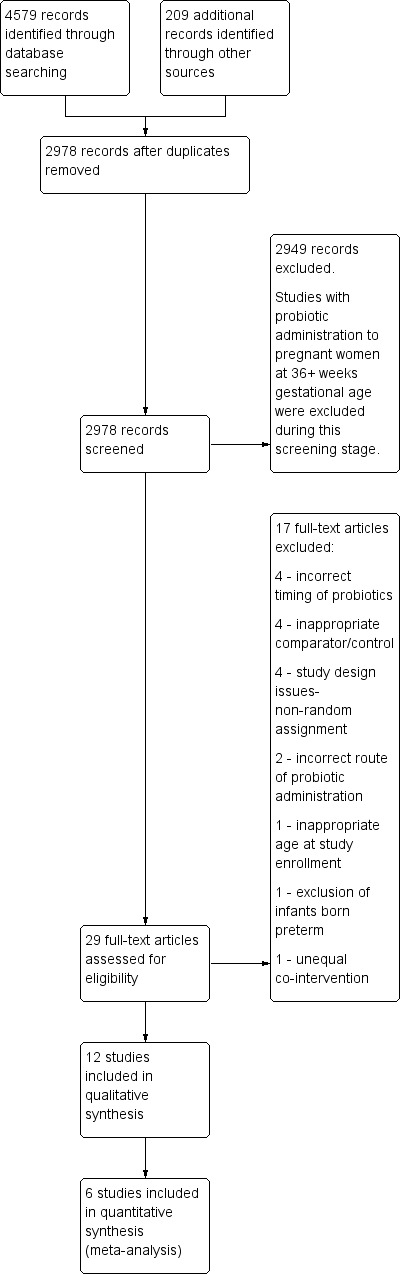

See the Figure 1 study flow diagram.

1.

1 Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

Twelve studies were found that met the inclusion criteria; 11 for the comparison of probiotics administered to pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation) versus placebo or no intervention, (Comparison 1) (Badehnoosh 2018; Dolatkhah 2015; Fernández 2016; Jacobsson 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Mantaring 2016; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), and one for the comparison of probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation versus maternal placebo or no intervention, (Comparison 2) (Benor 2014). The studies in Comparison 1 and 2 combined included 1450 mothers and 1204 known infants (as not all studies reported the number of infants born). No studies were found meeting the criteria for the comparison of probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation versus neonatal probiotic administration (Comparison 3).

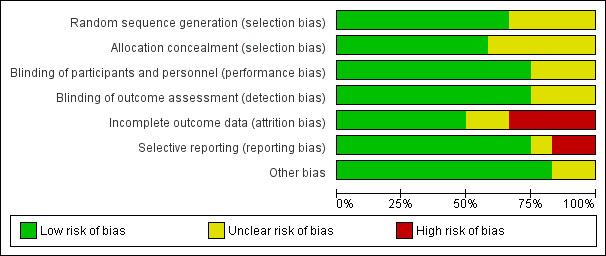

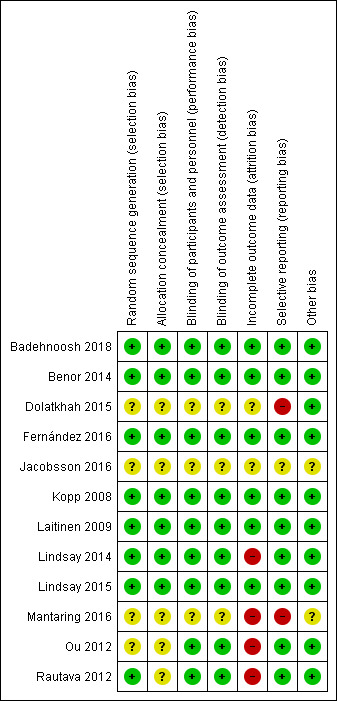

Nine studies reported on at least one outcome of interest and included 1199 mothers and 1048 known infants (as not all studies reported the number of infants born) (Badehnoosh 2018; Benor 2014; Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), while three studies (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016) with 260 mothers with 156 known infants did not report on outcomes of interest. Three studies conducted in pregnant women with atopy or with a fetus at risk for atopy that included 524 mothers and 484 infants (Kopp 2008; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), only had gestational age at birth as an outcome of interest, and did not report the data in a format suitable for meta‐analysis. The remaining six studies reported on at least one outcome of interest for a total of 675 mothers and 564 infants. Five of these studies were in Comparison 1 and included 626 mothers and 506 infants; four administered the intervention only to mothers during pregnancy (Badehnoosh 2018; Fernández 2016; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), and one administered the intervention during pregnancy and after birth (Laitinen 2009). One study met the criteria for Comparison 2, administering the intervention to mothers of preterm infants after birth, for a total of 49 mothers with 58 infants (Benor 2014). See the 'Rrisk of bias' tables for data on risk of bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Included studies

Comparison 1: Probiotics administered to pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation) versus placebo or no intervention

Before delivery (probiotics given only prior to delivery)

Summary: six studies were identified (Badehnoosh 2018; Dolatkhah 2015; Fernández 2016; Jacobsson 2016; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015).

Participants: there were six studies that administered probiotics to women only during pregnancy: three to pregnant women with gestational diabetes (Badehnoosh 2018;Dolatkhah 2015; Lindsay 2015), one to obese women at risk for metabolic derangements (Lindsay 2014), one to low‐risk women to assess immunological or inflammatory responses (Jacobsson 2016), and one to pregnant women with a history of mastitis during lactation (Fernández 2016).

Interventions: two studies used combination probiotics with various species of lLctobacillus, Bifidobacterium and/or Streptococcus (Badehnoosh 2018; Dolatkhah 2015), while four studies used single probiotic agents, three administering Lactobacillus salivarius (L. salivarius) (Fernández 2016; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015) and one using Lactobacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) (Jacobsson 2016). There was a degree of heterogeneity in terms of the timing and duration of the intervention, ranging from eight to 10 weeks until delivery (Jacobsson 2016), starting at 24 to 28 weeks and lasting four to eight weeks (Badehnoosh 2018; Dolatkhah 2015; Lindsay 2014), or starting at 30 weeks or < 34 weeks until delivery (Fernández 2016; Lindsay 2015). All control group participants received a placebo in these studies.

Outcomes of interest reported upon were preterm birth < 37 weeks (Badehnoosh 2018; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), preterm birth < 34 weeks (Lindsay 2014), gestational age at birth (Badehnoosh 2018; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), neonatal mortality (Lindsay 2014), miscarriage/stillbirth (Lindsay 2015), and mastitis (Fernández 2016).

Review of individual studies (based on study aims)

Treatment of maternal gestational diabetes

Badehnoosh 2018 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial at the Akbarabadi Clinic in Tehran, Iran (April 2016 to September 2016), evaluating the effects of probiotic supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes among participants with gestational diabetes (GDM). Sixty pregnant women diagnosed between 24 to 28 weeks with GDM who were not on oral hypoglycemic agents were randomly allocated to intake either probiotic capsule containing Lactobacillus acidophilus (L.acidophilus), Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) and Bifidobacterium bifidum (B. bifidum) ( 2 x 10^9 colony‐forming units (CFU)/g each) (n = 30) or placebo (n = 30) for six weeks. Primary outcomes were inflammatory markers, while secondary outcomes were biomarkers of oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth, gestational age at birth, Apgar scores, hospitalization, hypoglycemia, macrosomia, and cesarean delivery rates.

Dolatkhah 2015 conducted a double‐blind placebo‐controlled randomized clinical trial at Alzahra University Hospital in Tabriz, Iran (Spring and Summer 2014), to assess the effect of a probiotic supplementation on glucose metabolism and weight gain in pregnant women with newly diagnosed GDM. Sixty‐four pregnant women diagnosed between 24 to 28 weeks with GDM were randomly assigned to receive either aL.acidophilus LA‐5, Bifidobacterium BB‐12, Streptococcus thermophilus (S. thermophilus) STY‐31 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus (L. delbrueckii bulgaricus) LBY‐27 (4 biocap > 4 × 10^9 CFU) probiotic (n = 32) or placebo (n = 32) capsule along with dietary advice for eight consecutive weeks. Primary outcomes assessed were trend in weight gain and glucose metabolism indices in the mother. No outcomes of interest for this systematic review were reported.

Lindsay 2015 conducted a double‐blind placebo‐controlled randomized trial at the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin, Ireland (March 2012 to May 2014) to investigate the effects of a probiotic capsule intervention on maternal metabolic parameters and pregnancy outcome among pregnant women with gestational diabetes. One‐hundred forty‐nine singleton pregnant women with a new diagnosis of GDM in this pregnancy and who were < 34 weeks' gestation were randomly assigned to receive a capsule of probiotic (n = 74 ) with 100 mg of L. salivarius UCC118 at a target dose of 10^9 CFUs, or placebo (n = 75) until delivery. The primary outcome was the maternal fasting glucose and secondary outcomes were need for pharmacologic treatment of GDM, neonatal birth weight, stillbirths or miscarriages, gestational age at birth, preterm birth, cord blood metabolic parameters, Apgar score, small for gestational age (SGA) or large for gestational age (LGA) birth weight percentiles, and need for admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Treatment of maternal obesity

Lindsay 2014 (Probiotics in Pregnancy Study (ProP Study) conducted a placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized trial at the National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland (March 2012 to March 2013) that investigated the effect of a probiotic capsule on maternal fasting glucose in obese pregnant women. One‐hundred seventy‐five pregnant obese women were assigned to probiotic administration with 100 mg L. salivarius UCC118 at 10^9 CFU (n = 83) or placebo capsule (n = 82) from 24 to 28 weeks' gestation. The primary outcome was the change in maternal fasting glucose and secondary outcomes included differences in the incidence of impaired glycemic control, neonatal anthropometric measures, delivery complications, cord blood metabolic variables, 5‐minute Apgar score, preterm birth rate < 37 weeks or < 34 weeks, gestational age at birth, perinatal mortality and admission to the NICU.

Inflammation/lipids

Jacobsson 2016 conducted a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial to assess the effects of supplementation with L. rhamnosus (LGG) in low‐risk pregnant women on maternal immunological or inflammatory responses. Forty low‐risk pregnant women at eight to 10 weeks of pregnancy were randomized to receive L. rhamnosus (10^8 CFU) (n = 20) or placebo (n = 20) until delivery. Main outcomes assessed were inflammatory and immunologic assays at recruitment, 25 weeks and 35 weeks of gestation. No outcomes of interest for this systematic review were reported.

Prevention of mastitis

Fernández 2016 conducted a double‐blind, randomized controlled trial at the Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid, Spain that investigated the effect of an oral probiotic given to pregnant women to prevent infectious mastitis. One‐hundred‐eight pregnant women with a history of infectious mastitis after a prior pregnancy were assigned to probiotic capsule administration with L. salivarius PS2 at 9 x 10^10 CFU (n = 55) or placebo capsule (n = 53) from approximately week 30 of pregnancy until delivery. The primary outcome was the diagnosis of mastitis in the first three months after giving birth. Secondary outcomes included acute mastitis, subacute mastitis, breast pain scores, and breast milk bacterial counts.

Before and after delivery (probiotics given both prior to and after delivery)

Summary: five studies were identified that administered probiotics to women both prior to and after delivery (Kopp 2008, Laitinen 2009; Mantaring 2016;Ou 2012, Rautava 2012).

Participants: of the five studies, three studies enrolled pregnant women with a fetus at risk for atopy (Kopp 2008; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), while two studies focused on healthy women with a focus on nutrition (Laitinen 2009; Mantaring 2016).

Interventions: two studies used a single agent probiotic of Lactobacillus GG (Kopp 2008; Ou 2012), while three used combination probiotics, one using L. rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) versus Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) and B. longum (Rautava 2012), and the other two using L. rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis (B. lactis) (Laitinen 2009; Mantaring 2016). The beginning gestational age at first administration and the duration varied between studies from 14 weeks until end of exclusive breastfeeding (Laitinen 2009), four to six weeks before delivery until six months (Kopp 2008), 24 weeks until six months (Ou 2012), two months before delivery until two months after delivery (Rautava 2012), and the beginning of the third trimester until two months postpartum (Mantaring 2016). The studies that focused on atopic risk all had placebo capsules as the control (Kopp 2008, Ou 2012, Rautava 2012), while the other two studies had either nutritional counseling (Laitinen 2009), or nutritional beverage supplement (Mantaring 2016) that were administered in both the probiotic and control group.

Outcomes of interest reported upon were preterm birth < 37 weeks (Laitinen 2009), gestational age at birth (Kopp 2008; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), although these studies did not report average and standard deviation (SD) and thus cannot be included quantitative analysis, neonatal mortality (Laitinen 2009), miscarriage/stillbirth (Laitinen 2009), and neonatal and maternal sepsis (Laitinen 2009).

Review of individual studies (based on study aims)

Multiple aims

Laitinen 2009 conducted a randomized controlled trial in maternal welfare clinics in Turku and South‐West Finland (April 2002 to November 2005) that investigated the impact of dietary counseling and/or probiotics on pregnant women with an aim to optimize maternal dietary intake and metabolism, to advance maternal health and reduce the risk of disease in the child. After final recruitment, 256 healthy pregnant women were recruited, 85 were in the control + placebo group, and 171 were in the nutritional intervention group. These 171 pregnant women were further randomized in a double‐blind fashion to receive probiotics (L. rhamnosus GG, and B. lactis Bb12, 10^9 CFU/day) and the nutritional intervention (n = 85), or placebo and the nutritional intervention (n = 86) from enrollment to the study around 14 weeks' gestation until the end of exclusive breastfeeding. Fourteen articles have been published from the original trial (Characteristics of included studies), with one only including a subset of enrolled patients as it was published before final recruitment. Primary and secondary outcomes vary between the articles, and include outcomes focused on maternal dietary compliance, adiposity, pregnancy weight gain, anthropometric measurements during and after pregnancy, maternal diagnosis of gestational diabetes, maternal laboratory indices for lipids, leptin, and glucose metabolism, as well as placental fatty acids, breast milk fatty acids and inflammatory markers, maternal sepsis and infant sensitization. Outcomes pertinent to the neonate include birth weight, birth length, birth head circumference, gestational age at birth, miscarriage rate, preterm birth < 37 weeks, preterm birth < 32 weeks, preterm birth 32 to 36 weeks, cesarean delivery rate, perinatal mortality, infant sepsis, and 5‐minute Apgar score. There are also reports of illness in mother and illness in child without further description. For this review, the two arms that received the nutritional intervention and either probiotic or placebo were included and compared.

Atopy

Kopp 2008 conducted a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled prospective trial at outpatient gynecology offices co‐ordinated with the University of Freiburg in Freiburg, Germany (July 2002 to June 2004), to investigate the immunologic proliferative response and cytokine release in cultures of isolated mononuclear cells from pregnant women and their neonates supplemented withLactobacillus GG (LGG) or placebo. Ninety‐four pregnant women with at least one first‐degree relative or a partner with an atopic disease were randomly assigned to receive either the probiotic LGG (ATCC 53103; 5 x 10^9 CFUs LGG twice daily) or placebo four to six weeks before expected delivery. This was followed by a post‐natal period of six months in which breastfeeding mothers took the randomized interventions for three months, but formula‐fed infants (n = 2 in the LGG group, n = 3 in the placebo group) were given the agents directly. After three months, the capsules were given only directly to infants until six months. Primary outcomes were proliferative response of cord blood mononuclear cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the corresponding mother. Secondary outcomes included gestational age at birth. Only outcomes pertaining to the prenatal period of probiotic administration were included since formula‐fed infants were directly given the probiotic or placebo.

Ou 2012 conducted a prospective, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan (August 2002 and January 2006), to evaluate the effectiveness of prenatal and postnatal probiotics in the prevention of early childhood and maternal allergic diseases. One‐hundred ninety‐one pregnant women with atopic diseases were randomly assigned to receive either probiotics (Lactobacillus GG; 1x10^ 10 CFUs daily) (n = 95) or placebo (n= 96) from 24 weeks of pregnancy until delivery. After delivery, the interventions were given exclusively to breastfeeding mothers or to non‐breastfeeding neonates until six months of age. Outcomes assessed were the point and cumulative prevalence of sensitization and development of allergic diseases, and improvement of maternal allergic symptom score and plasma immune parameters before and after intervention. Mother‐infant pairs were followed until 36 months. Secondary outcomes include gestational age at birth. Only outcomes pertaining to the prenatal period of probiotic administration were included in this review since formula‐fed infants were directly given probiotics or placebo.

Rautava 2012 conducted a parallel, double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial at a single tertiary center in Turku, Finland (August 2005 and April 2009), to investigate whether maternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and breast‐feeding reduces the risk of developing eczema in high‐risk infants. Two‐hundred forty‐one mothers with allergic disease and atopic sensitization were randomized to receive (1) L. rhamnosus 1 x 10^9 CFIU and B. longum 1 x 10^9 CFUs (n = 81), (2) L paracasei 1 x1 0^9 CFUs and B longum 1 x1 0^9 CFUs (n = 82), or (3) placebo (n = 78), beginning two months before delivery and during the first two months of breast‐feeding. The primary outcome was cumulative incidence of eczema in the infant up to two years old. Secondary outcomes were atopic sensitization, gestational age at birth, birth weight, and duration of exclusive breast‐feeding.

Nutrition

Mantaring 2016 conducted a double‐blind, randomized controlled study at the Community Hospital of Muntinlupa City, Philippines to assess the effects of maternal nutritional supplement beverages formulated both with and without a probiotic mixture on maternal health, fetal/infant growth and health when given to pregnant women in the third trimester and during lactation. Two‐hundred thirty‐three healthy women in the beginning of the third trimester of pregnancy who were willing to exclusively breast feed for at least two months were assigned to receive a daily nutritional supplement (S, n = 78); the same supplement with probiotics L. rhamnosus (CGMCC 1.3724) 7 x 10^8 CFU and B. lactis (CNCC I‐3446) 7 x 10^8 CFU per serving (S pro, n = 78), or no supplement (no‐S, n = 77) for the duration of their pregnancy and eight weeks' postpartum. Outcomes included maternal health outcomes at gestational months six, seven, eight, and delivery, as well as neonatal health outcomes, including fetal ultrasound at 24 to 28 weeks, birth weight, Apgar scores, and infant growth over the first year of life. No outcomes of interest for this systematic review were reported.

Comparison 2: probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation versus maternal placebo or no intervention

Summary: there was one study that administered probiotics to postpartum mothers who have given birth to a preterm infant born < 37 weeks' gestation identified (Benor 2014).

Participants: mothers of infants born with birth weight of 1500 g or less who intended to breast feed and were enrolled within 48 hours of birth, and their infants were included in Benor 2014.

Interventions:Benor 2014 administered L. acidophilus and B. lactis. Placebo capsules were used in the control group.

Outcomes of interest:Benor 2014 reported on the following outcomes of interest: any necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), death prior to hospital discharge, death or NEC, surgery for NEC, bacterial sepsis, culture‐proven sepsis with probiotic organism, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), days to feeding with more than 50% breast milk.

Benor 2014 conducted a prospective, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial at the Tel Aviv Medical Center in Israel (June 2007 to November 2009) which examined the effects of maternal oral probiotic supplementation on the incidence of NEC, death, and sepsis in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants fed with maternal breast milk. Mothers were assigned to supplementation with L. acidophilus and B. lactis 2 × 10(E) CFU/day or to placebo starting from one to three days postpartum. The primary outcome measures were NEC, sepsis, and death. A total 49 mothers of 58 VLBW infants were recruited (25 infants were in the probiotic group and 33 in the placebo group).

Comparison 3: probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation versus neonatal probiotic administration

Postpartum mothers who have given birth to a preterm infant born < 37 weeks' gestation; and

Newborn infants born < 37 weeks' gestation.

Summary: no studies identified.

Excluded studies

We excluded 17 studies from this review. Four studies were excluded due to timing of administration of probiotics that did not align with the criteria that the intervention be given in the trimester of birth, or intention to administer within one week of birth if stopped in the second trimester. Three studies were excluded due to probiotics administered only until the second trimester (Jain 2017; Jamilian 2016; Krauss‐Silva 2011), and one was excluded due to post‐natal administration of probiotics to mothers of term infants (Ortiz‐Andrellucchi 2008). Two studies administered the intervention vaginally, not orally, and were excluded on the grounds of incorrect route of administration (Daskalakis 2014; Karampelas 2013). As a placebo or no intervention was a requirement for the control group, four studies were excluded due to inappropriate comparator, with three studies using either yogurt or fermented product which presumably contain probiotics in both arms (Asemi 2011; Asemi 2012; Nishijima 2005), and one study was excluded due to a comparison of probiotic treatment versus antibiotic treatment (Hantoushzadeh 2012). Bisanz 2014 was excluded due to a co‐intervention only given to the probiotic group and not the control group. Gonai 2014 was excluded due to unclear gestational age at study entry, and Gronlund 2011; Grzeskowiak 2012; Hanson 2014; and Vitali 2012 were excluded due to issues with study design, including non‐random assignment and non‐random assessment of a larger randomized trial. Wickens 2008 was excluded due to multiple factors including recruitment at 35 weeks, mothers who gave birth prior to 37 weeks or had infants with a NICU admission were explicitly excluded, and probiotics were administered directly to the infant after birth starting on day two. See the table of Characteristics of excluded studies for more details about individual studies.

Post hoc the decision was made to exclude studies that administered probiotics starting at 36 weeks' gestation to pregnant women, as the majority of infants of these mothers would be born at term, especially with the inclusion criteria that the probiotics were intended to be administered for at least one week. The population of interest in this review is preterm infants, and the outcomes of interest relate to prematurity. Including these studies would not fit with the overall goal of this review. There is a large body of literature that fits this criteria and listing those studies is beyond the scope of this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Sequence generation: four studies did not describe how participants were randomized into groups (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016; Ou 2012) and therefore have an unclear risk of selection bias in this domain. Eight studies used computer‐generated random numbers (Badehnoosh 2018; Benor 2014; Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Rautava 2012,) with three of these studies having this sequence generation done by independent researchers or statisticians removed from the rest of the study (Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015). Overall, there is a low risk of allocation bias due to issues with sequence generation, as those studies with unclear risk of bias did not contribute data to the outcomes included.

Allocation concealment: five studies did not describe their allocation concealment and were deemed to have an unclear risk (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), while two studies did not specifically describe their allocation concealment but were deemed to be low risk due to the use of placebo capsules that resembled the probiotic capsules (Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008). In one study, allocation was said to be concealed from the researcher and participants until final analyses but not fully described (Badehnoosh 2018), and in another study sealed envelopes were opened in the room with the patient (Laitinen 2009). Sequentially‐numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes were used in two studies (Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), and opaque medication boxes with identical capsules was used in one study (Benor 2014) as methods for allocation concealment. Overall, the risk of bias due to allocation concealment is low.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel: nine studies were deemed to be low risk for performance bias with eight studies that were double blinded (Benor 2014 ;Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), and one study (Badehnoosh 2018) in which it was unclear if the research nurse who randomized participants was blinded, but other personnel and participants were blinded. Three studies did not describe blinding of participants or personnel and are of unclear risk of performance bias (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016).

Blinding of outcome assessors: four studies described that groups were concealed from the researchers at least until after outcomes were assessed (Badehnoosh 2018; Benor 2014; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), three studies had no clear description of blinding but the outcomes assessed were thought to be straightforward enough to have low risk of detection bias (Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009), while two studies had adequate blinding of assessors for most outcomes (Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), totaling nine studies that are deemed to be low risk for detection bias. Three studies had no description of blinding of outcome assessors and are thus of unclear risk (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016).

Incomplete outcome data

Six studies were deemed to have low attrition bias due to < 10% of participants lost to follow up in five studies (Badehnoosh 2018; Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2015), and in one study that had 89% full outcome data, with the other 11% only being excluded due to a lack of ability to provide > 50% breast milk by one week postpartum (Benor 2014). Four studies were at high risk for attrition bias due to > 10% participants lost to follow‐up (Lindsay 2014; Mantaring 2016; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), while two studies had unclear risk due to no description of their completeness of data (Dolatkhah 2015; Jacobsson 2016). Of note, the number of infants was lower than the number of mothers due to miscarriage and dropouts from the studies.

Selective reporting

Nine studies were deemed to be low risk, five since outcomes that were described in the study protocols were reported (Badehnoosh 2018; Benor 2014; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), and four that did not have published study protocols but reported data for outcomes that were stated (Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012). One study was deemed to have unclear risk (Jacobsson 2016) due to lack of information in the abstract, and two studies that did not report data for all planned outcomes were considered high risk of reporting bias (Dolatkhah 2015; Mantaring 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

Ten of the studies have low risk of other sources of bias (Badehnoosh 2018; Benor 2014; Dolatkhah 2015; Fernández 2016; Kopp 2008; Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012), while two have an unclear risk due to their lack of description in their abstracts (Jacobsson 2016; Mantaring 2016).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Probiotics administered to pregnant women at risk of preterm birth compared to placebo or no intervention for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants.

| Probiotics administered to pregnant women compared to placebo or no intervention for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants Setting: Intervention: probiotics administered to pregnant women < 36 weeks' gestation Comparison: placebo or no intervention. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no intervention. | Risk with Probiotics administered to pregnant women < 37 weeks' gestation | |||||

| Preterm birth < 37 weeks' gestation | Study population | Typical RR 0.92 (0.32 to 2.67) | 518 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 26 per 1,000 | 24 per 1,000 (8 to 70) | |||||

| Preterm birth < 34 weeks' gestation | Study population | ‐ | 287 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 3 | No preterm birth < 34 weeks' gestation in either group. | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | The mean gestational age at birth (weeks) was 0 | MD 0.15 higher (0.33 lower to 0.63 higher) | ‐ | 207 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Outcome added post hoc |

| Death | Study population | ‐ | 298 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | No death reported in either group. | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Miscarriage/stillbirth | Study population | Typical RR 0.79 (0.20 to 3.14) | 320 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Outcome added post hoc | |

| 25 per 1,000 | 20 per 1,000 (5 to 78) | |||||

| Neonatal sepsis ≤ 3 days | Study population | not estimable | 162 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 3, 4 | ||

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Severe necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (Bell stage II or more) |

Not reported | |||||

| Death or severe NEC | Not reported | |||||

| Late‐onset sepsis | Not reported | |||||

| Culture‐proven sepsis with supplemented probiotic | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate, The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Indirectness: mothers enrolled not at high risk for preterm birth

2 Imprecision: wide confidence interval

3 Imprecision: below the optimal information size

4 Imprecision: only one study contributes to the evidence

Summary of findings 2. Probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants compared to maternal placebo or no intervention for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants.

| Probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants compared to maternal placebo or no intervention for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants Setting: Intervention: probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation Comparison: maternal placebo or no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with maternal placebo or no intervention | Risk with Probiotics administered exclusively after birth in mothers of preterm infants < 37 weeks' gestation | |||||

| Any necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) | Study population | RR 0.44 (0.13 to 1.46) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Outcome added post hoc | |

| 273 per 1,000 | 120 per 1,000 (35 to 398) | |||||

| Death prior to hospital discharge | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.06 to 6.88) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 61 per 1,000 | 40 per 1,000 (4 to 417) | |||||

| Death or NEC | Study population | RR 0.53 (0.19 to 1.49) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 303 per 1,000 | 161 per 1,000 (58 to 452) | |||||

| Surgery for NEC | Study population | RR 0.15 (0.01 to 2.58) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Outcome added post hoc | |

| 121 per 1,000 | 18 per 1,000 (1 to 313) | |||||

| Neonatal sepsis | Study population | RR 1.32 (0.48 to 3.61) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 182 per 1,000 | 240 per 1,000 (87 to 656) | |||||

| Culture‐proven sepsis with probiotic organism | Study population | not estimable | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Feeding with more than 50% breast milk (days) | The mean feeding with more than 50% breast milk (days) was 0 | MD 9.6 lower (19.04 lower to 0.16 lower) | ‐ | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Outcome added post hoc Although statistically significant, the result is imprecise and only derived from the one included study |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Impression: wide confidence interval suggesting extreme imprecision. GRADE assessment downgraded two levels

Comparison 1: probiotics administered to pregnant women (< 36 weeks' gestation) versus placebo or no intervention

Preterm birth < 37 weeks' gestation (outcome 1.1 and outcome 1.2)

Four studies reported on preterm birth at < 37 weeks, three of which administered the intervention during pregnancy only (Badehnoosh 2018; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015), and one in which the intervention was given to mothers during pregnancy and after birth (Laitinen 2009). A total of 518 mothers and 505 infants are included in this outcome. Of note, the number of infants was lower than the number of mothers due to miscarriage and dropouts from the study. There were no individual studies that reached statistical significance. The studies are relatively small and give very imprecise estimates of effect (Laitinen 2009: risk ratio (RR) 0.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.03 to 2.22; Badehnoosh 2018: RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.19 to 20.90; Lindsay 2014: RR 1.79, 95% CI 0.31 to 10.35; and Lindsay 2015: RR not estimable, risk difference (RD) 0.0, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.03).

Overall, 2.5% (13/518) of mothers enrolled in these four studies delivered preterm. When combined in the meta‐analysis, there is no proven effect on preventing preterm birth at < 37 weeks' gestation and the results remain very imprecise (typical RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.32 to 2.67; 4 studies, 518 mothers). There was no significant heterogeneity for this meta‐analysis ( I2 of 14%).

Further subgroup analysis was undertaken, for preterm birth < 37 weeks as this was the only outcome with greater than two included studies.

Probiotic preparation: two studies (287 mothers) administered Lactobacillus preparations (Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015) and two studies (231 mothers) administered mixed probiotic preparations (Badehnoosh 2018; Laitinen 2009). No differences emerge regarding the impact on preterm birth at < 37 weeks' gestation based on probiotic preparation (Lactobacillus preparations: typical RR 1.79, 95% CI 0.31 to 10.35; mixed probiotic preparations: typical RR of 0.60, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.48) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Probiotics administered to pregnant women at risk of preterm birth (< 37 weeks' gestation) vs. placebo or no intervention., Outcome 2 Preterm birth < 37 weeks' gestation (probiotic preparation).

Gestational age at which probiotics were initiated: a subgroup analysis based upon the gestational age at which probiotics were initiated < 20 weeks' gestation or > 20 weeks' gestation was undertaken as a post‐hoc analysis.

Two studies administered probiotics to 309 mothers < 20 weeks' gestation (Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014) and two studies administered probiotics to 209 mothers > 20 weeks' gestation (Lindsay 2015: Badehnoosh 2018). When only studies that enrolled pregnant women < 20 weeks were included the typical RR was 0.74 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.51), and for those with enrollment > 20 weeks, the typical RR was 2.00 (95% CI 0.19 to 20.90) (Analysis 1.1). These results are non‐significant and highly imprecise.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Probiotics administered to pregnant women at risk of preterm birth (< 37 weeks' gestation) vs. placebo or no intervention., Outcome 1 Preterm birth < 37 weeks' gestation (age at enrollment).

Economic country setting: the subgroup analysis of economic country setting was also undertaken, with Badehnoosh 2018 taking place in a lower middle‐income country and Laitinen 2009, Lindsay 2014, and Lindsay 2015 taking place in high‐income countries. Excluding the results from Badehnoosh 2018 did not change the significance of the results with a typical RR of 0.74 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.51).

Methodologic quality: a sensitivity analysis was also performed to include only studies with high‐methodological quality. All of the included studies overall had high‐methodological quality, except for Lindsay 2014, where there was a concern for attrition bias. Excluding Lindsay 2014 does not significantly alter the results or significance of results with a typical RR of 0.60 (95% CI 0.5 to 2.48).

Other planned analyses: Planned subgroup analyses of mothers who provided breast milk, and subgroup analyses based upon infant weight and gestational age at birth were unable to be performed as studies performed during pregnancy did not classify infants into these categories. There were no studies of mothers with the risk of preterm birth of preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM), preterm labor, genital infection or history of preterm birth, so no subgroup analysis could be performed based upon risk for preterm labor as planned.

Preterm birth < 34 weeks' gestation (outcome 1.3)

Preterm birth < 34 weeks was reported by two studies that included 287 mothers and infants: Lindsay 2014 and Lindsay 2015 both of which administered probiotics during pregnancy only. No infants were born less than 34 weeks in either of these studies, and thus the risk ratio is not estimable and the typical RD is 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; 2 studies, 287 mothers).

Gestational age at birth (weeks) (outcome 1.4)

The gestational age at birth was reported in five studies including 735 mothers and 733 infants (Badehnoosh 2018; Kopp 2008; Lindsay 2015; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012). Two studies with 209 mothers with 207 infants reported data that was in a form suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis (Badehnoosh 2018; Lindsay 2015), with both studies administering probiotics only before pregnancy. Neither study showed an individually statistically significant difference in gestational age, and when combined, the MD in gestational age at birth was 0.15, (95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.63; 2 studies, 207 mothers). The three other studies that reported gestational age at birth (Kopp 2008; Ou 2012; Rautava 2012) had similar median values and ranges or similar mean and SD range in the probiotic and control groups. Overall, there was not a significant difference in gestational age seen in these studies.

Death (outcome 1.5)

Neonatal mortality was reported in two studies (Laitinen 2009; Lindsay 2014), reporting on a total of 309 mothers and 298 infants. There was no infant mortality in either study out of 298 infants for a typical RD of 0.00 (95% CI‐0.02 to 0.02; 2 studies, 298 infants) and a non‐estimable relative risk.

Miscarriage/stillbirth (outcome 1.6)