Abstract

Background

This is the second update of a Cochrane Review (Issue 4, 2006). Pain and distress from needle‐related procedures are common during childhood and can be reduced through use of psychological interventions (cognitive or behavioral strategies, or both). Our first review update (Issue 10, 2013) showed efficacy of distraction and hypnosis for needle‐related pain and distress in children and adolescents.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

Search methods

We searched six electronic databases for relevant trials: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE; PsycINFO; Embase; Web of Science (ISI Web of Knowledge); and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). We sent requests for additional studies to pediatric pain and child health electronic listservs. We also searched registries for relevant completed trials: clinicaltrials.gov; and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int.trialsearch). We conducted searches up to September 2017 to identify records published since the last review update in 2013.

Selection criteria

We included peer‐reviewed published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with at least five participants per study arm, comparing a psychological intervention with a control or comparison group. Trials involved children aged two to 19 years undergoing any needle‐related medical procedure.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data and assessed risks of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. We examined pain and distress assessed by child self‐report, observer global report, and behavioral measurement (primary outcomes). We also examined any reported physiological outcomes and adverse events (secondary outcomes). We used meta‐analysis to assess the efficacy of identified psychological interventions relative to a comparator (i.e. no treatment, other active treatment, treatment as usual, or waitlist) for each outcome separately. We used Review Manager 5 software to compute standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and GRADE to assess the quality of the evidence.

Main results

We included 59 trials (20 new for this update) with 5550 participants. Needle procedures primarily included venipuncture, intravenous insertion, and vaccine injections. Studies included children aged two to 19 years, with few trials focused on adolescents. The most common psychological interventions were distraction (n = 32), combined cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; n = 18), and hypnosis (n = 8). Preparation/information (n = 4), breathing (n = 4), suggestion (n = 3), and memory alteration (n = 1) were also included. Control groups were often 'standard care', which varied across studies. Across all studies, 'Risk of bias' scores indicated several domains at high or unclear risk, most notably allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessment, and selective reporting. We downgraded the quality of evidence largely due to serious study limitations, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Very low‐ to low‐quality evidence supported the efficacy of distraction for self‐reported pain (n = 30, 2802 participants; SMD −0.56, 95% CI −0.78 to −0.33) and distress (n = 4, 426 participants; SMD −0.82, 95% CI −1.45 to −0.18), observer‐reported pain (n = 11, 1512 participants; SMD −0.62, 95% CI −1.00 to −0.23) and distress (n = 5, 1067 participants; SMD −0.72, 95% CI −1.41 to −0.03), and behavioral distress (n = 7, 500 participants; SMD −0.44, 95% CI −0.84 to −0.04). Distraction was not efficacious for behavioral pain (n = 4, 309 participants; SMD −0.33, 95% CI −0.69 to 0.03). Very low‐quality evidence indicated hypnosis was efficacious for reducing self‐reported pain (n = 5, 176 participants; SMD −1.40, 95% CI −2.32 to −0.48) and distress (n = 5, 176 participants; SMD −2.53, 95% CI −3.93 to −1.12), and behavioral distress (n = 6, 193 participants; SMD −1.15, 95% CI −1.76 to −0.53), but not behavioral pain (n = 2, 69 participants; SMD −0.38, 95% CI −1.57 to 0.81). No studies assessed hypnosis for observer‐reported pain and only one study assessed observer‐reported distress. Very low‐ to low‐quality evidence supported the efficacy of combined CBT for observer‐reported pain (n = 4, 385 participants; SMD −0.52, 95% CI −0.73 to −0.30) and behavioral distress (n = 11, 1105 participants; SMD −0.40, 95% CI −0.67 to −0.14), but not self‐reported pain (n = 14, 1359 participants; SMD −0.27, 95% CI −0.58 to 0.03), self‐reported distress (n = 6, 234 participants; SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.56 to 0.04), observer‐reported distress (n = 6, 765 participants; SMD 0.08, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.50), or behavioral pain (n = 2, 95 participants; SMD −0.65, 95% CI −2.36 to 1.06). Very low‐quality evidence showed efficacy of breathing interventions for self‐reported pain (n = 4, 298 participants; SMD −1.04, 95% CI −1.86 to −0.22), but there were too few studies for meta‐analysis of other outcomes. Very low‐quality evidence revealed no effect for preparation/information (n = 4, 313 participants) or suggestion (n = 3, 218 participants) for any pain or distress outcome. Given only a single trial, we could draw no conclusions about memory alteration. Adverse events of respiratory difficulties were only reported in one breathing intervention.

Authors' conclusions

We identified evidence supporting the efficacy of distraction, hypnosis, combined CBT, and breathing interventions for reducing children’s needle‐related pain or distress, or both. Support for the efficacy of combined CBT and breathing interventions is new from our last review update due to the availability of new evidence. The quality of trials and overall evidence remains low to very low, underscoring the need for improved methodological rigor and trial reporting. Despite low‐quality evidence, the potential benefits of reduced pain or distress or both support the evidence in favor of using these interventions in clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Psychological strategies to reduce pain and distress for children and adolescents getting needles

Bottom line

Psychological strategies help reduce children's pain, distress, and fear of needles. Distraction and hypnosis are helpful, although specific breathing (such as inflating a balloon), and combining multiple psychological strategies can also help.

Background

Psychological strategies affect how children think or what they do before, during, or after a needle. They can be used by children or with support from parents or medical staff, like nurses, psychologists, or child life specialists. The information applies to children aged from two to 19 years who are healthy or ill, undergoing all types of needle procedures at the hospital, in a clinic, or at school.

Key results

For this update, in September 2017, we searched for clinical trials looking at psychological strategies for reducing pain and distress of children and teens getting a needle. We found 59 trials including 5550 children and teens. Twenty of these trials were new for this update. We found six psychological strategies, four of which help reduce children's pain and distress during needles. These include distraction, hypnosis, specific breathing, and combining multiple strategies (‘combined cognitive behavioral’). Ways to distract children and teens during needles include reading, watching a movie, listening to music, playing video games, or virtual reality. Hypnosis involves deep relaxation and imagery, and is usually taught to a child by a trained professional. Examples of strategies that can be combined include distraction, breathing, relaxation, positive thoughts, having the child learn or practice the steps of the needle procedure, and coaching parents about ways to support their child. Other psychological strategies have been tested but do not seem helpful on their own. For example, children do not have less pain or distress when they are only told what is going to happen before or during the needle ('providing information or preparation or both) or when someone merely suggests to the child that something is being done to help them. One other strategy is helping children to remember their previous needles more positively. There is not enough information yet to know if this is helpful.

Quality of evidence

We rated the quality of the evidence from studies using four levels: very low, low, moderate, or high. The quality of the evidence from this review is very low to low, as results may be biased by including only small numbers of children or by children knowing what psychological intervention they received. This means that we are uncertain about the results.

Summary of findings

Background

This review is an update of two previous iterations published in the Cochrane Library (2006, Issue 4 and 2013, Issue 10).

Description of the condition

Pain and distress due to medical procedures are common during childhood. Needles are routinely given from the first year of life, particularly for vaccine injections. Current recommendations state that healthy children receive 20 to 30 immunizations before the age of 18 years (CDC 2018; NACI 2018; WHO 2018). Among children with acute or chronic illness, needle procedures are even more frequent for the assessment and management of their conditions (Stevens 2011; Stevens 2012), and are reported as the most distressing part of treatment (Ljungman 1999). Unfortunately, pain and distress associated with medical procedures are often poorly managed in routine care (Berberich 2012; Stevens 2011; Taddio 2009). As well as negatively impacting the child, significant child pain and distress during needle procedures are reported as highly distressing and challenging for parents and healthcare providers (Kennedy 2008).

Failure to adequately manage pain and distress during needle procedures can lead to the development of significant needle fears, which often begin in early to middle childhood and persist into adulthood (McMurtry 2015b). Moreover, fear of needles contributes to vaccine hesitancy (Taddio 2012), and medical non‐adherence (Pate 1996). Thus, needle pain and distress are critical and timely to address, given the growing concern for increasing outbreaks of preventable and infectious diseases and the potential loss of herd immunity (Smith 2014).

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition of the need to adequately manage needle‐related pain and distress. Evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines have been developed for the management of pain and fear during vaccine injections, and include recommended pharmacological, physical, and psychological strategies (McMurtry 2016; Taddio 2015). For psychological interventions, existing guidelines recommend using a variety of cognitive and behavioral interventions that have been deemed efficacious in reducing pain during needle procedures (e.g. blowing bubbles, distraction). Moreover, guidelines recommend not using strategies that have been deemed ineffective in reducing pain (e.g. making reassuring statements like “don’t worry”). Many of these strategies have been recommended by the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts for the management of immunizations worldwide (WHO 2015). Additional efforts include hospital certifications (ChildKind International; www.childkindinternational.org; Schechter 2010a) and hospital‐wide policies (Schechter 2008), as well as recommended standards of care for the management of medical procedures, including needles, for youth with cancer (Flowers 2015), and social media efforts targeting parents (#itdoesnthavetohurt; www.itdoesnthavetohurt.ca).

Description of the intervention

Consistent with previous iterations of this review (Uman 2006; Uman 2013), we include only non‐pharmacological psychological interventions for pain that are cognitive‐behavioral in this update. We do not include non‐pharmacological physical interventions such as acupuncture, heat, or cold.

Cognitive interventions include techniques that target negative or unrealistic thoughts to help replace them with more positive beliefs and attitudes. Behavioral interventions include techniques that target negative or maladaptive behaviors to help replace them with more positive and adaptive behaviors. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) uses a combination or variation of strategies targeting cognitions (thoughts) or behaviors, or both (Barlow 1999). CBT for pain management aims to help individuals develop and use coping skills to manage their pain and distress, and often includes a combination of various techniques, such as distraction, relaxation training, deep breathing, hypnosis, preparing for and rehearsing the procedure in advance, using positive reinforcement for adaptive behaviors, making positive coping statements, and receiving coaching to use adaptive strategies (Chen 2000a; Christophersen 2001; Keefe 1992). Engagement and developmental appropriateness are thought to contribute to the efficacy of each intervention (Birnie 2017).

Many of the psychological interventions described in this review do not require highly specialized training and can be administered by non‐psychologists, such as other healthcare providers (e.g. child life specialists, nurses) and parents. However, some trials describe brief training and education in order to maximize the effectiveness of interventions. Furthermore, psychological interventions often have natural appeal, given their tendency to draw on children’s coping tendencies, potential use of minimal or widely available resources, and feasible implementation across clinical care settings.

How the intervention might work

There are several proposed mechanisms through which psychological interventions might work. Cognitive interventions target thoughts whereas behavioral interventions target individual behaviors. CBT uses a combination or variation of both cognitive or behavioral strategies, or both (Barlow 1999). Cognitive, behavioral, and combined cognitive‐behavioral strategies are believed to influence pain and distress through cognitive (e.g. attention, motivation, expectations, suggestibility), learning processes, physiological, or neurobiological or both mechanisms (Accardi 2009; Birnie 2017; Jafari 2017; Noel 2018). As in our previous reviews, all of the cognitive, behavioral, and cognitive‐behavioral strategies described above fall under the overarching category of ‘psychological’ interventions. Psychological interventions for pain management aim to help individuals to develop and use coping skills to manage their pain and distress, and can include various techniques such as distraction, relaxation training, deep breathing, hypnosis, preparing for and rehearsing the procedure in advance, using positive reinforcement for adaptive behaviors, making positive coping statements, and receiving coaching to use adaptive strategies (Chen 2000a; Christophersen 2001; Keefe 1992).

For this second review update, we revised the previous intervention categories that focused on methodological similarities to now reflect theorized or proposed mechanisms of treatment effect versus methodological similarities (e.g. virtual reality interventions are now encompassed within distraction interventions) (Accardi 2009; Birnie 2017; Jafari 2017; Noel 2018). We hoped this would lead to more meaningful conclusions and would also minimize the number of intervention categories that had small numbers of trials.

Why it is important to do this review

Previous narrative, non‐systematic reviews and book chapters on this topic have been published (Alvarez 1997; Blount 2003; Chen 2000a; Christophersen 2001; Kazak 2001; Powers 1999; Young 2005); however, more rigorous systematic reviews examining a variety of psychological interventions for needle pain and distress are essential to draw firmer conclusions about intervention efficacy and guide clinical decision‐making.

Our original Cochrane Review (Uman 2006; Uman 2008) included 28 RCTs, supported the efficacy of several interventions (distraction, hypnosis, and CBT), and led to recommendations about improving the quality of trials in this area (Uman 2010). Our first review update (Uman 2013) expanded this original review, and included 39 RCTs (18 new) and coded each trial for risks of bias. We found evidence for the efficacy of distraction and hypnosis. Overall, we rated the risks of bias of trials as high or unclear, suggesting the need for improvements in methodological rigor and reporting.

In the five years since the publication of our first update, several new trials have been published, examining psychological interventions for needle‐related pain and distress in children and adolescents. Advances and expansion of technology have been made (e.g. humanoid robots, smartphone apps), and peer‐reviewed journals have continued to raise standards for trial reporting and quality. The aim of this second review update was therefore to identify new trials, to synthesize the results of new trials with those previously reviewed, and to extend assessment of trial quality. This enables us to make firmer, more refined conclusions about the existing evidence on the efficacy of these interventions and to strengthen the evidence base for future research and clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with at least five participants in each study arm. The original version of this review (Uman 2006) included quasi‐randomized trials (e.g. alternating assignment) and unpublished trials (e.g. dissertations). We excluded these from the first review update (Uman 2013) and from this current update, to focus only on the highest‐quality evidence available. We applied no language restrictions during the search, and obtained translations when necessary.

Types of participants

We included RCTs involving children and adolescents aged two to 19 years, undergoing any needle‐related medical procedure. Participants included healthy children and children with chronic or transitory illnesses from both inpatient and outpatient settings. We excluded children under two years old, due to developmental differences either precluding the appropriateness of reviewed psychological interventions in infancy or the qualitatively different application of these interventions in that age group. Furthermore, the efficacy of psychological interventions for procedural pain and distress in infants is thoroughly addressed in another review (Pillai‐Riddell 2011; Pillai‐Riddell 2015). We selected a maximum age of 19 years to be consistent with the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of adolescence that extends to 19 years of age (http://www.searo.who.int/ en/Section13/Section1245_4980.htm). The efficacy of psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain in adults is reviewed elsewhere (Boerner 2015). We preferred a broad age range to minimize exclusion of any relevant studies. We excluded studies including any participants beyond two‐ to 19‐year olds unless we could obtain data from authors for the relevant eligible subsample, while also continuing to meet the minimum criterion of five participants per group.

This review focuses on needle‐related procedures performed for medical purposes, which are the most commonly occurring and feared procedures for both healthy and chronically‐ill children (Broome 1990; Ljungman 1999; McMurtry 2015a). A list of common included needle‐related procedures and their definitions can be found in Table 8. We excluded needle procedures performed for non‐medical purposes (e.g. body piercings or tattoos).

1. Definitions of medical procedures.

| Procedure | Definition |

| Accessing a portacath (also known as a port) | Insertion of a needle into an implanted access device (portacath) which facilitates the drawing of blood and intravenous (or intra‐arterial) injections by not having to locate and insert a cannula into a new vessel. Some ports are connected for intrathecal, intraperitoneal or intracavitary injections. |

| Arterial blood gas (ABG) | A test which analyses arterial blood for oxygen, carbon dioxide and bicarbonate content in addition to blood pH. Used to test the effectiveness of respiration. |

| Arterial line (also known as intra‐arterial catheter) | Insertion of a catheter into an artery. |

| Arterial puncture | A hole, wound, or perforation of an artery made by puncturing. |

| Bone marrow aspiration (BMA) | The bone marrow is the tissue that manufactures the blood cells and is in the hollow part of most bones. This test is done by suctioning some of the bone marrow for examination. |

| Bone marrow biopsy (BMB) | The removal and examination of tissue, cells, or fluids from the bone marrow of a living body; usually performed at the same time as a BMA. |

| Central line (also known as central venous catheter) | Insertion of a catheter into the large vein above the heart, usually the subclavian vein, through which access to the blood stream can be made. This allows drugs and blood products to be given and blood samples withdrawn. |

| Finger prick/pin | Obtaining blood by puncturing the tip of the finger. |

| Immunization (also known as immunization) | Protection against a particular disease or treatment of an organism by protecting against certain pathogen attacks; the introduction of microorganisms that have previously been treated to make them harmless. |

| Injection | The act of forcing a liquid into tissue, the vascular tree, or an organ. |

| Intramuscular injection | Injection administered by entering a muscle. |

| IV/catheter insertion | A narrow short, flexible, synthetic (usually plastic) tube known as a catheter, that is inserted approximately one inch into a vein to provide temporary intravenous access for the administration of fluid, medication, or nutrients. |

| Lumbar punctures (LP) (also known as spinal tap) | The withdrawal of cerebrospinal fluid or the injection of anesthesia by puncturing the subarachnoid space located in the lumbar region of the spinal cord. |

| Paracentesis | A surgical puncture of a bodily cavity (e.g. abdomen) with a trocar, aspirator, or other instrument usually to draw off an abnormal effusion for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. |

| Subcutaneous injection | Injection administered under the skin. |

| Suture (also known as laceration repair) | A stitch made with a strand or fiber used to sew parts of the living body. |

| Thoracocentesis (also called thoracentesis) | Aspiration of fluid from the chest. |

| Venepuncture (also known as venipuncture) | The surgical puncture of a vein typically for withdrawing blood or administering intravenous medication. |

We also excluded studies if they specifically included participants with known needle phobias (i.e. diagnosed by a qualified professional such as a psychologist and warranting specific clinical assessment, diagnoses, and targeted intervention). Other reviews address specific evidenced‐based psychological interventions for high levels of needle fears/phobias that are different from those indicated for procedural pain management (e.g. exposure‐based treatment) (McMurtry 2015a; McMurtry 2016).

We excluded children undergoing surgery, given the numerous factors specific to surgery or intensive care units that complicate or interfere with self‐report of pain and distress (e.g. sedation, intubation, more intensive pharmacological interventions, long‐term hospitalization, inability or difficulty attributing pain or distress to a specific medical procedure) (Puntillo 2004). We made an exception for studies evaluating a psychological intervention for a pre‐surgical needle procedure (e.g. intravenous insertion) only when outcomes of interest were completed prior to surgery or sedation.

Types of interventions

Studies had to include at least one trial arm that assessed a primarily psychological intervention. Trials had to include at least one comparator arm (i.e. no treatment, other active treatment, treatment as usual, or waitlist). We placed no restrictions on duration, intensity, or frequency of psychological interventions. Interventions had to occur at some point prior to the needle procedure and the assessment of outcomes of interest. We excluded studies in which psychological intervention(s) were combined with a non‐psychological intervention (e.g. pharmacological, physical), so that the unique effects of the psychological intervention could not be isolated and evaluated.

As specified in the review protocol and original version of this review (Uman 2005; Uman 2006), psychological interventions were broadly defined as those using cognitive, behavioral, or combined cognitive‐behavioral strategies. In brief, cognitive interventions are those primarily targeting thoughts and feelings, whereas behavioral interventions are those primarily targeting overt behaviors (Barlow 1999). Combined cognitive‐behavioral interventions are defined as those including at least one cognitive strategy combined with at least one behavioral strategy. For this update, intervention categories were generally based on key theorized mechanisms of effect or specific distinct strategies, or both (Accardi 2009; Birnie 2017; Jafari 2017; Noel 2018), with similar interventions grouped together based on conceptualizations or intervention descriptions or both, included in published papers. Emphasizing mechanisms of effect in defining intervention categories resulted in some intervention categories from previous iterations of this review being subsumed under other broader categories. We did this to allow more meaningful meta‐analyses, and to avoid intervention categories with very small numbers of studies or single trials only. Specifically, we now include virtual reality interventions as one type of distraction, given their conceptualized application in this context for pain reduction (Kenney 2016). We now include the following interventions from the previous review as combined CBT, as they include at least one cognitive and one behavioral strategy as described in the original review protocol (Uman 2005): parenting coaching plus child distraction, parent positioning plus child distraction, and distraction plus suggestion. As stated in our original review protocol (Uman 2005), the division of psychological interventions into mutually exclusive categories is difficult, given a lack of consistent operational definitions. We feel our emphasis on treatment mechanisms in this second update reflects emerging empirical evidence and contemporary thinking in our understanding of psychological interventions for acute pain and distress.

Studies in this second update fall under one of the following psychological intervention categories:

Distraction;

Combined CBT;

Hypnosis;

Preparation/information;

Breathing;

Suggestion;

Memory alteration.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest were pain intensity and distress. These are two core outcome domains recommended for clinical trials in pediatric acute pain (PedIMMPACT; McGrath 2008). Distress is broadly defined as any type of negative affect associated with the needle procedure (e.g. anxiety, fear, stress). We extracted pain and distress outcomes separately, as assessed by child self‐report, observer global report (e.g. parents, nurses, researchers, etc. report using single‐item scales), and/or behavioral measurement (e.g. validated rating scales assessing observed pain or distress behaviors or both, displayed by the child).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include any physiological measurement that has been associated with pain and distress and that it is practical to quantify in a clinical setting. Examples include heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, cortisol levels, transcutaneous oxygen tension (tcPO2), and transcutaneous carbon dioxide tension (tcPCO2) (Jafari 2017; Sweet 1998). We also assessed adverse events.

Timing of outcome assessment

Where possible, we extracted outcomes assessed during the needle procedure. If outcomes during the needle procedure were not evaluated, we selected the next time point occurring closest to the completion of the procedure. If outcomes were assessed both during and following the needle‐related procedure, we included only outcomes assessed during the needle procedure. We did not include outcomes assessed at other times (e.g. pre‐needle outcomes).

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified published studies through electronic database searches, postings to various electronic listservs, and clinical trial registries.

Electronic searches

We developed detailed search strategies through consultation with a reference librarian and assistance from the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care (PaPaS) Group. Definitions for included medical procedures (MedLine 2004) are described in Table 8.

We searched the following six electronic databases for relevant trials:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Library Issue 8 of 12, 2017;

MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process (OVID), March 2013 to 12 September 2017;

Embase (OVID), March 2013 to 2016, week 37;

PsycINFO (OVID), 2013 to September week 1, 2017;

Web of Science (ISI Web of Knowledge), 2013 to 12 September 2017;

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), March 2013 to September 2017.

Database search terms were consistent with previous versions of this review (Uman 2006; Uman 2013). We conducted updated searches in September 2016 and September 2017 to identify any records published since the last review update in 2013. See appendices for search strategies, keywords, and MeSH terms as appropriate for each database: MEDLINE (Appendix 1), PsycINFO (Appendix 2), CENTRAL (Appendix 3), Embase (Appendix 4), IBI Web of Knowledge (Appendix 5), and CINAHL (Appendix 6).

Searching other resources

We also solicited relevant studies through professional listservs, including:

Pain in Child Health (PICH);

Pediatric Pain;

American Psychological Association’s Society of Pediatric Psychology Division 54;

American Psychological Association’s Health Psychology Division 38.

For this update, we also searched clinical trial registries for any relevant completed trials, including clinicaltrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int.trialsearch). We also included any other relevant studies identified and included in the original review and the previous update.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors considered titles and abstracts retrieved from database searches for review inclusion (LU and CC for original review; KB and MN for first and second review updates). Two review authors checked full‐text articles when relevance and eligibility for the current review were unclear from the abstract alone (LU and CC for original review; KB and MN for review updates). We resolved discrepancies through discussion with a third review author.

Included studies had to use true random assignment. We determined this based on the description of participant assignment available in each study’s peer‐reviewed publication. We retrieved and included 28 RCTs in the original review (Uman 2006), although we later excluded seven of these studies from subsequent review updates, including this one, as they were unpublished dissertations or reported quasi‐randomized methods (e.g. alternating assignment). Updated database searches (conducted March 2012 and March 2013) for the last review update (Uman 2013) identified an additional 18 RCTs meeting our inclusion criteria and providing necessary data. Searches for the current (second) update (conducted September 2016 and September 2017) identified an additional 20 RCTs, for a total of 59 RCTs included in this review. We coded all included RCTs in full. References for included studies are provided below in the ’Description of studies’ section.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data (LU and CC original review; KB and MN for review updates), using a data extraction form designed for the original review. A researcher outside the review team who was fluent in Farsi reviewed one non‐English study in the previous review update, to confirm inclusion eligibility and conduct data extraction. Extracted data included study design, participant demographics, diagnosis (when applicable), type of needle procedure, type of intervention and control conditions, outcomes, as well as other related variables. A third review author was available to resolve coding discrepancies, if needed. If studies reported incomplete data necessary for meta‐analysis, we contacted study authors. We excluded RCTs if the data necessary for data pooling were not available in the published study, could not be identified through contact with the study authors, or could not be calculated based on other data provided. A trained research assistant or another study author, or both, reviewed the extracted data for errors. We analyzed all data suitable for pooling using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan) (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (KB and MN) independently assessed risks of bias for all included studies, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2017), with any disagreements resolved by discussion. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study using the 'Risk of bias' tool in RevMan.

We assessed the following for each study.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as: low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random‐number table; computer random‐number generator); unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated). We excluded studies using a non‐random process (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes); unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated). We considered studies that did not conceal allocation (e.g. open list) to have high risk of bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed methods as: low risk of bias (study states that it was blinded and describes the method used to achieve blinding); unclear risk of bias (study states that it was blinded but does not provide an adequate description of how this was achieved). We considered studies that were not blinded or when the nature of the psychological intervention precluded participants and personnel from being blinded (e.g. obvious intervention such as watching television or a medical clown in the room) to have high risk of bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (study has a clear statement that outcome assessors were unaware of treatment allocation, and ideally describes how this was achieved); unclear risk of bias (study states that outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation but lacks a clear statement on how this was achieved). We considered studies where outcome assessment was not blinded or when the nature of the psychological intervention precluded outcome assessors from being blinded to have a high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data). We assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data as: low risk (no missing data, reasons for missing data unlikely to be related to true outcome or balanced with similar reasons across groups); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgment of risk); high risk of bias (reasons for missing data judged likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons across groups).

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias). We assessed whether primary and secondary outcome measures were prespecified and whether these were consistent with those reported: low risk of bias (study protocol is available, or is not available but it is clear that the report specified and reported on all expected outcomes); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgment of risk); high risk of bias (study did not prespecify and/or report all primary outcomes, one or more outcomes is reported incompletely so that it cannot be entered in meta‐analysis).

Other bias (checking for possible biases not covered elsewhere). We assessed other bias in studies as: low risk of bias (study appears to be free of other sources of bias); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgment of risk); high risk of bias (at least one important risk of bias likely to impact study findings, such as baseline group differences reported and not accounted for, using unvalidated/unreliable measurement tool, inadequate sample size/study underpowered).

Measures of treatment effect

Given the nature of the outcome measures in this review, all outcome data were continuous (e.g. rating scales). We calculated standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which allowed the combination of results across different measurement scales assessing the same outcome (e.g. pain). We applied the following rule of thumb for interpreting SMDs as effect sizes, as suggested by Cochrane (Higgins 2017): 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 represents a medium effect, and 0.8 represents a large effect (Cohen 1988). We assessed each category of psychological intervention separately in a meta‐analysis. Within each intervention category, we assessed outcomes and measurement type separately. We pooled all comparators together. We only conducted meta‐analysis when data from more than a single RCT were available. Thus, for each psychological intervention we assessed possible treatment effects for the following seven outcomes:

Pain: self‐report;

Pain: observer global report;

Pain: behavioral measure;

Distress: self‐report;

Distress: observer global report;

Distress: behavioral measure;

Physiological measures: each physiological outcome was assessed separately.

Unit of analysis issues

We included parallel two‐group RCTs as well as cluster‐randomized trials (i.e. groups of individuals randomized together to the same intervention). We included cross‐over trials only when data were available separately for each group following the first treatment arm (i.e. prior to cross‐over). We did this because once psychological interventions have been introduced, it can be difficult to prevent participants from using these strategies themselves at subsequent needle procedures (e.g. distraction). We included studies with multiple treatment groups so long as each treatment group separately met the review inclusion criteria.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact study authors in all situations when data necessary for data pooling were not reported in published RCTs (e.g. means, standard deviations (SDs), group sizes). If this was not possible, we used statistical methods for calculating missing data from other reported measures of variation as recommended (e.g. calculating standard deviations from standard errors, confidence intervals, t values, and P values) (Higgins 2017). We excluded studies or outcomes or both from this review when we could not contact the authors or they did not respond, did not have data available, or when we could not calculate data necessary for pooling from available data. We included the number of participants in each group identified in published study results sections. When not otherwise specified by the authors, we assumed there were no study dropouts and used the reported group sizes in the meta‐analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using both the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic. Given that Chi2 tests often have low statistical power, we used a Type 1 error level of 0.10 for rejecting the null hypothesis of homogeneity. While Chi2 tests are useful for identifying whether heterogeneity is present, it has been argued that there will always be some level of heterogeneity in meta‐analyses, given the clinical and methodological diversity (Higgins 2017). The I2 statistic provides a measure of inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2017). I2 is expressed as a percentage from 0% to 100%, and we used the following rough interpretation guide: 0% to 40%, might not be important; 30% to 60%, may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%, may represent substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2017). Ranges overlap, as the importance of I2 depends on several other factors such as the magnitude and direction of effects, as well as the strength of evidence for the heterogeneity (for example, the P value for the Chi2 test or the confidence interval for the I2 statistic). In cases where we found statistically significant heterogeneity, data were still pooled but should be interpreted with caution. Given significant heterogeneity for several analyses, we analyzed results using a random‐effects model.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used several strategies to overcome publication, language, and outcome reporting bias in this update and previous iterations (Uman 2006; Uman 2013). We imposed no language barriers in database searches, we searched clinical trial registries, we posted requests to listservs in pediatric health and pain regarding any published, unpublished, or in‐progress studies, and tried to obtain any and all missing data from included studies through repeated email requests to study authors or co‐authors. We included any studies in the meta‐analysis that provided completed results (i.e. means, SDs, and cell sizes for both treatment and control groups) for at least one outcome measure of interest. Information related to reporting biases is also captured in the 'Risk of bias' tool. Fourteen of the studies included in this review had authors who responded to requests for missing data (Balan 2009; Bisignano 2006; Caprilli 2007; Cavender 2004; Crevatin 2016; Gupta 2006; Kleiber 2001; Liossi 1999; McCarthy 2010; Meiri 2016; Miguez‐Navarro 2016; Nilsson 2015; Sinha 2006; Sander Wint 2002).

Data synthesis

We calculated SMDs using a random‐effects model separately for all outcomes for each intervention category when necessary data were available. We considered interventions to be efficacious when the SMD and corresponding CIs were negative. The reported P values reflect the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis.

We combined intervention groups that included variations of the same psychological intervention category (e.g. two types of distraction) to create a single pair‐wise comparison, as recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2017). When multiple control conditions were available, we selected the condition that could most clearly isolate the active ingredient of the intervention condition. For example, comparing eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) + distraction (intervention group) to EMLA only (selected control group) instead of no‐EMLA standard care (not‐selected control group). Another example includes comparing music with headphones (intervention group) to headphones only without music (selected control group) instead of no headphones or music (not‐selected control group).

Many control conditions are defined as standard or routine care groups. Some include cognitive or behavioral techniques, or both. We made an a priori decision to consider these as control groups as conceptualized by the authors themselves, and it is ethical for the conduct of clinical trials not to offer below current standard of care. Less common are studies that report the use of pharmacological strategies, such as topical anesthetics, in standard care. In such cases, we also considered these as a control condition as long as it was offered similarly to the intervention condition, in addition to psychological strategies.

We combined outcomes in cases when multiple observers rated children’s pain or distress or both (e.g. nurses, parents, researchers) or when multiple behavioral measures assessed pain or distress or both (e.g. both the child‐adult medical procedure inventory scale (CAMPIS) and observation scale of behavioral distress (OSBD) for distress). We pooled data using statistical formulae recommended by Cochrane for combining means and SDs: pooled mean = [(mean1 x N1) + (mean2 x N2) / (N1 + N2)] and pooled SD = square root of [SD12 (N1−1)+SD22 (N2−1)]/N1+N2−2.

Quality of the evidence

Two review authors (KB and MN) independently rated the quality of the outcomes. We used the GRADE system as applied to continuous outcomes (Guyatt 2013) to rate the quality of evidence separately for all intervention categories and all outcomes with data from more than one RCT. We used the GRADE profiler Guideline Development Tool software (GRADEpro GDT 2015), GRADE recommendations (Guyatt 2011) and the guidelines provided by Cochrane (Higgins 2017).

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning a quality level to a body of evidence (Higgins 2017):

High: randomized trials; or double‐upgraded observational studies

Moderate: downgraded randomized trials; or upgraded observational studies

Low: double‐downgraded randomized trials; or observational studies

Very low: triple‐downgraded randomized trials; or downgraded observational studies; or case series/case reports

Factors that may decrease the quality level of a body of evidence are:

Limitations in the design and implementation of available studies suggesting a high likelihood of bias;

Indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes);

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (including problems with subgroup analyses);

Imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals);

High probability of publication bias.

Factors that may increase the quality level of a body of evidence are:

Large magnitude of effect;

All plausible confounding would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect;

Dose‐response gradient.

We decreased the GRADE rating by one (−1) or two (−2) if we identified:

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study quality;

Important inconsistency: I2 statistic moderate > 45% (−1) or I2 statistic considerable > 90% (−2);

Some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness;

Imprecise or sparse data: sample size < 400 (−1) or sample size < 100) (−2);

High probability of reporting bias (−1).

For transparency, we documented all reasons for downgrading the GRADE quality of evidence rating. Decreases of 3 or more ratings dropped the GRADE quality levels to 'very low'.

GRADE quality levels are interpreted as follows:

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; and

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

'Summary of findings' tables

We include seven 'Summary of findings' tables to present the main findings in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, we included key information about the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all primary outcomes:

Pain: self‐report;

Pain: observer global report;

Pain: behavioral measure;

Distress: self‐report;

Distress: observer global report;

Distress: behavioral measure

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We assessed each category of psychological intervention separately (i.e. distraction, hypnosis, etc.) as consistent with previous versions of this review. For each intervention, we conducted analyses separately by type of outcome (pain and distress) and measurement (self‐report, observer‐report, behavioral, physiological). We assessed different physiological outcomes separately (e.g. heart rate versus blood pressure). As described above, we calculated the Chi2 test and I2 statistic for all outcomes to assess heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We were unable to conduct all of the sensitivity analyses that we had proposed in our original review, due to insufficient data reported within and across studies, as well as the small number of studies within each intervention category. The main sensitivity analyses conducted in the original review involved comparing the study results when quasi‐randomized trials were added to the analyses. However, in order to strengthen the methodological quality of the findings in subsequent updates, we have limited the included trials to only true RCTs. We have therefore not conducted additional sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

We conducted six electronic database searches in total: one for the original review (February 2005) (Uman 2006); three for the first review update (December 2010, March 2012, March 2013) (Uman 2013); and two for the current review update (September 2016, September 2017).

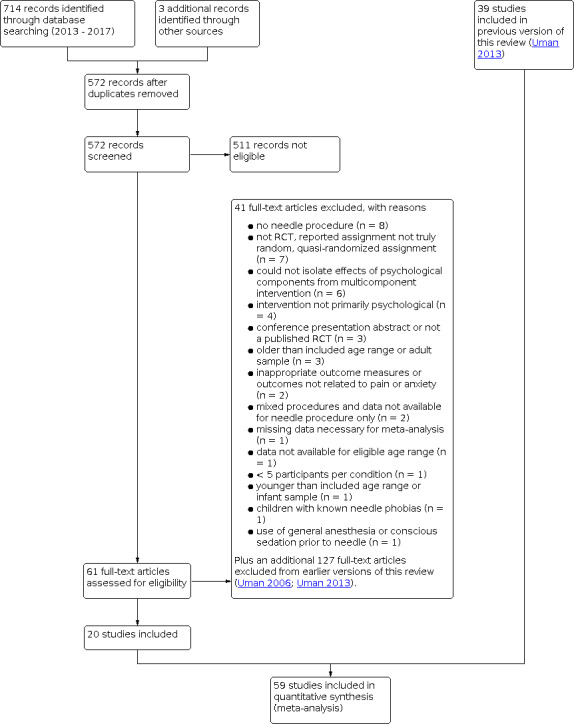

Database searches conducted in September 2017 for this review update identified 714 records, and our searches of other resources (i.e. professional listservs and trials registries) identified an additional three studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. After duplicate records had been removed, there remained 572 unique abstracts for review. Of these, 511 records were deemed not eligible. We reviewed 61 manuscripts in full, of which 20 met our inclusion criteria and provided the data necessary for data pooling. We included 39 trials in the previous review update (Uman 2013). This incorporated 21 studies from the original review published prior to 2005 (Uman 2006), plus 18 additional studies published between 2005 and 2013. Although the original review included 28 studies (Uman 2006), we excluded seven of these (reported in eight publications) from subsequent review updates, including this one, due to lack of adequate randomization procedures (Cohen 1997; Cohen 1999; Cohen 2002; French 1994) and being unpublished dissertation theses (Krauss 1996; Posner 1998; Zabin 1982). We found no non‐English studies in the database searches for this review update. Previous review searches identified studies in Portuguese (Santos 2000), German (Hoffman 2011; Kammerbauer 2011), Italian (Bufalini 2009; Lessi 2011), and Farsi (Alavi 2005; Shahabi 2007; Vosoghi 2010) which were either translated or assessed and coded in full by a native language speaker. Thus, 59 studies meet the inclusion criteria for this review update. For a further description of our screening process, see the study PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

This review and meta‐analysis includes 59 studies (n = 5550 participants). Of these, 21 studies were identified in the original review (Blount 1992; Cassidy 2002; Cavender 2004; Chen 1999; Eland 1981; Fanurik 2000; Fowler‐Kerry 1987; Gonzalez 1993; Goodenough 1997; Harrison 1991; Katz 1987; Kleiber 2001; Kuttner 1987; Liossi 1999; Liossi 2003; Liossi 2006; Press 2003; Tak 2006; Tyc 1997; Vessey 1994; Sander Wint 2002), 18 studies from the first review update (Balan 2009; Bellieni 2006; Bisignano 2006; Caprilli 2007; Gold 2006; Gupta 2006; Huet 2011; Inal 2012; Jeffs 2007; Kristjansdottir 2010; Liossi 2009; McCarthy 2010; Nguyen 2010; Noguchi 2006; Sinha 2006; Vosoghi 2010; Wang 2008; Windich‐Biermeier 2007), and 20 studies from the most recent searches conducted in September 2017 (Aydin 2017; Beran 2013; Cohen 2015; Crevatin 2016; Ebrahimpour 2015; Kamath 2013; Luthy 2013; Meiri 2016; Miguez‐Navarro 2016; Miller 2016; Minute 2012; Mutlu 2015a; Nilsson 2015; Oliveira 2017; Pourmovahed 2013; Ramírez‐Carrasco 2017; Rimon 2016; Sahiner 2016; Yinger 2016; Zieger 2013). Included trials had two to six study arms. Two studies used cross‐over designs (Nilsson 2015; Oliveira 2017), and there were no cluster‐RCTs.

Of the 59 included studies, nine assessed multiple psychological interventions (Cohen 2015; Fowler‐Kerry 1987; Gupta 2006; Kuttner 1987; Liossi 1999; Miller 2016; Sahiner 2016; Tak 2006; Wang 2008). In one study (Mutlu 2015a), we deemed only one of two interventions eligible for inclusion in the review (i.e. balloon inflation). Four studies assessed multiple types of distraction interventions (Aydin 2017; Bellieni 2006; Miller 2016; Sahiner 2016). Assessed interventions included distraction (n = 32), followed by combined CBT (n = 18), hypnosis (n = 8), preparation and information (n = 4), breathing (n = 4), suggestion (n = 3), and memory alteration (n = 1).

Needle procedures varied, and included venipuncture or blood draw only (n = 20), immunization or injection (n = 11), intravenous insertion (n = 8), lumbar puncture (n = 6), intravenous cannulation or venipuncture (n = 4), bone marrow aspiration (n = 3), local dental anesthetic injection (n = 3), and intramuscular injection, laceration repair, allergy testing involving injection, and insulin injection (n = 1 each). Ages of participating children and adolescents ranged from two to 19 years old. Most studies (n = 34) focused exclusively on children in early childhood (two to five years old) or middle childhood (i.e. six to 12 years old). Only one study focused exclusively on adolescents (i.e. 13 to 15 years old). All remaining studies (n = 24) included children ranging from early childhood to late adolescence (up to 19 years olds). Most studies (n = 33) provided no specific health diagnoses for participating children and adolescents. The remaining studies included children with mixed chronic illness (n = 13), children with cancer (n = 12), or children with diabetes (n = 1). Trials were conducted in a variety of settings, including hospital inpatients, hospital outpatient clinics, emergency departments, community clinics, and schools.

See the ’Characteristics of included studies’ tables for more detail by study and the seven 'Summary of findings' tables for more details by type of intervention.

Excluded studies

Overall, across all three iterations of this review, we excluded 168 studies after reviewing full‐text articles. Of these 168 excluded studies, 51 were excluded from the original review (Uman 2006), 69 from the previous review update (Uman 2013), 41 from the current review update, plus an additional seven included in the original review that we excluded from subsequent review updates, due to studies lacking true randomization or being unpublished dissertation theses. Additionally, we excluded one intervention arm for an otherwise included study (Mutlu 2015b).

Primary reasons for exclusion were:

Not a randomized controlled trial, reported assignment not truly random, quasi‐randomized assignment, randomization failed (n = 53) (Agarwal 2017; Alhani 2010; Ashkenzai 2006; Atkinson 2009; Bagnasco 2012; Ben‐Pazi 2017; Boivin 2008; Bowen 1999; Cline 2006; Cohen 1997; Cohen 1999; Cohen 2002; Cohen 2010; Crowley 2011; Davit 2011; Dufresne 2010; Forsner 2014; French 1994; Heckler‐Medina 2006; Hedén 2009; Hoffman 2011; Howe 2011; Jimeno 2014; Kammerbauer 2011; Kearl 2015; Lawes 2008; Lessi 2011; Liossi 2007; MacLaren 2005; MacLaren 2007; Manimala 2000; Manne 1990; Manne 1994; McCarthy 1998; McCarthy 2014; McInally 2005; Nilsson 2009; Powers 1993; Ramponi 2009; Rogovik 2007; Schechter 2010b; Sikorova 2011; Singh 2016; Slifer 2011; Sparks 2001; Stefano 2005; Sury 2010; Thurgate 2005; Tüfekci 2009; Vohra 2011; Wood 2002; Yoo 2011; Zahr 1998);

Missing data necessary for pooling, such as means, SDs, and cell sizes (n = 24) (Arts 1994; Bengston 2002; Carlson 2000; Chen 2000b; Dahlquist 2002; Fassler 1985; Gilbert 1982; Goymour 2000; Inal 2010; Hartling 2013; Jay 1987; Kazak 1996; Kazak 1998; Klingman 1985; Kuttner 1988; Malone 1996; Megel 1998; O'Laughlin 1995; Peretz 1999; Reeb 1997; Santos 2000; Vernon 1974; Young 1988; Zeltzer 1982);

Older than included age range or adult sample (n = 14) (Agarwal 2008; Anson 2010; Drahota 2008; Hudson 2015; Jacobson 2006; Kwekkeboom 2003; McWhorter 2014; Salih 2010; Schneider 2011; Shabanloei 2010; Shimizu 2005; Slack 2009; Tokunaga 2017; Vika 2009);

No needle procedure (n = 11) (Chow 2017; Cumino 2017; Franzoi 2016; Isong 2014; Kettwich 2007; Marechal 2017; Quan 2016; Seiden 2014; Suresh 2015; Weber 2010; Weinstein 2003);

Intervention not primarily psychological (n = 9) (Anghelescu 2013; Demir 2012; Garret‐Bernardin 2017; Marec‐Bérard 2009; Mutlu 2015b; Park 2008; Shemesh 2017; Ujaoney 2013; Wallace 2010);

Unpublished dissertation (n = 9) (Christiano 1996; Krauss 1996; Lustman 1983; Myrvik 2009; Olsen 1991; Posner 1998; Schur 1986; Winborn 1989; Zabin 1982);

No control or comparison group or inappropriate control group (n = 8) (Broome 1998; Hawkins 1998; Jay 1995; Kolk 2000; Slifer 2009; Smith 1989; Smith 1996; Wall 1989);

Inappropriate intervention or could not isolate effects of psychological components from multi‐component intervention (n = 8) (Baxter 2011; Benjamin 2016; Franck 2014; Jay 1991; Lee 2013; Moadad 2016; Schreiber 2016; Stevenson 2005);

Conference presentation abstract or not a published RCT (n = 6) (Bufalini 2012; Fancourt 2016; Firoozi 2014; Inal 2010; Russell 2012; Skinner 2015);

Inappropriate outcome measures or outcomes not related to pain or anxiety (n = 5) (Alderfer 2010; Bruck 1995; Chan 2013; Jay 1990; Oberoi 2016);

Surgical procedure (n = 3) (Hatava 2000; Klorman 1980; Melamed 1974);

Cross‐over design with data not available pre‐cross‐over (n = 3) (Alavi 2005; El‐Sharkawi 2012; Shahabi 2007);

Younger than included age range or infant sample (n = 3) (Cramer‐Berness 2005; Hillgrove‐Stuart 2013; Ozdemir 2012);

Use of general anesthesia or conscious sedation prior to needle procedure (n = 3) (Bufalini 2009; Kain 2006; Rajan 2017);

Variable medical procedures or causes of pain, and data not available for needle procedure only (n = 3) (Jibb 2017; Mohan 2015; Tyson 2014).

Fewer than five participants per condition (n = 2) (Felluga 2016; Pederson 1996);

Data not available for eligible age range (n = 1) (Shanmugam 2016)

Inclusion of children with known needle phobias (n = 1) (Berge 2017)

Only one group received an adjunctive pharmacological intervention (n = 1) (Berberich 2009);

Secondary data analysis and original study not included in review (n = 1) (Dahlquist 2005).

See ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table for reasons of exclusion.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of ’Risk of bias’ assessments for all included studies. More detail on the ’Risk of bias’ judgments can be found in the 'Characteristics of included studies' section.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We rated 33 studies (55.9%) as being at unclear risk of bias, as the process for sequence generation was not clearly reported. We rated the other 26 studies (44.1%) as being at low risk of bias, as they reported clear strategies for generating random sequences (e.g. computer‐generated random‐number table). We rated no studies at high risk of bias for this domain.

Allocation concealment

We rated 46 studies (78.0%) as being at unclear risk of bias, as they did not report any detail about allocation concealment strategies. We rated only three studies (5.1%) as being at low risk of bias for clearly reporting use of sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. We rated the remaining 10 studies (16.9%) at high risk of bias for reporting open allocation strategies.

Blinding

We rated 57 studies (96.6%) at high risk of bias and two (3.4%) at unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel; we rated no studies at low risk of bias for this domain. This was largely due to the nature of psychological interventions that are often obvious to children and nurses, or they are involved in delivery of the intervention itself. We rated one study (Gonzalez 1993) at unclear risk of bias in circumstances where parents delivered the intervention, making it possible for the child or nurse administering the needle, or both, to be blind to study group, although that was unclearly reported. We rated a second study (Goodenough 1997) at unclear risk of bias, as the intervention was a minor alteration to wording (i.e. suggestion), unlikely to be detected by the child.

We rated 56 studies (94.9%) at high risk of bias, two studies (3.4%) at unclear risk, and one study (1.7%) at low risk for blinding of outcome assessment. Similarly, most studies at high risk of bias were attributable to the obvious nature of psychological interventions. The few instances with unclear or low risk of bias occurred when the psychological intervention was not overtly apparent or when outcome raters were unaware of the group assignment (e.g. blinded observational assessment).

Incomplete outcome data

We rated 48 studies (81.4%) at low risk of bias, seven studies (11.9%) at unclear risk, and four (6.8%) at high risk for incomplete reporting of outcome data. We gave low ratings in circumstances where all outcomes were reported in full and with sufficient detail to be included in meta‐analysis, or where missing data were balanced across groups, or likely not to be related to study outcomes. We gave high risk of bias ratings when reasons for missing data were likely related to study outcomes, or an imbalance in missing data or dropouts between groups. We gave unclear ratings where insufficient information was provided.

Selective reporting

We rated 36 studies (61.0%) at unclear risk of bias, 17 studies (28.8%) at high risk, and six studies (10.2%) at low risk for selective reporting of outcomes. Most studies were given unclear risk of bias ratings when primary and secondary outcomes of interest were not clearly outlined, making it difficult to determine whether study outcomes were fully reported. We gave high risk of bias ratings when one or more outcomes of interest were incompletely reported. We gave low risk of bias ratings in circumstances where primary and secondary outcomes were identified a priori and reported in full.

Other potential sources of bias

We rated 32 studies (54.2%) at high risk of bias, 15 studies (25.4%) at low risk, and 12 studies (20.3%) at unclear risk for other potential sources of bias. Common areas of concern contributing to high risk of bias ratings included studies with small sample sizes or that were underpowered to detect treatment effects, contamination of intervention strategies between groups, use of unreliable or unvalidated outcome measures, or significant group differences that were not controlled for in analyses (e.g. variable number of injections, parental presence).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Summary of findings 1. Distraction compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

| Distraction compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 2‐19 years with mixed medical (acute or chronic illness) or generally healthy undergoing venipuncture, immunization, intravenous insertion, lumbar puncture, bone marrow aspiration, routine injection, allergy testing injections, or laceration repair Setting: hospital (inpatient/outpatient/emergency department), community clinic, or school Intervention: distraction Comparison: control (varied across studies) | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments** | |

| Risk with control | Risk with distraction | ||||

| Self‐reported pain | The mean level of self‐reported pain in the control group ranged from 0.65 to 8.32 (adjusted to a 0 to 10 scale). | The mean level of self‐reported pain with distraction was 0.56 standard deviations lower (0.78 to 0.33 lower). | 2802 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,b | This result equates to a moderate difference in favor of distraction |

| Self‐reported distress | See comment | The mean level of self‐reported distress with distraction was 0.82 standard deviations lower (1.45 to 0.18 lower) | 426 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c | This result equates to a large difference in favor of distraction |

| Observer‐reported pain | See comment | The mean level of observer‐reported pain with distraction was 0.62 standard deviations lower (1 to 0.23 lower) | 1512 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,d | This result equates to a moderate to large difference in favor of distraction |

| Observer‐reported distress | See comment | The mean level of observer‐reported distress with distraction was 0.72 standard deviations lower (1.41 to 0.03 lower) | 1067 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,d | This result equates to a moderate to large difference in favor of distraction |

| Behavioral measures‐ pain | See comment | The mean level of behavioral pain with distraction was 0.33 standard deviations lower (0.69 lower to 0.03 higher) | 309 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | There is no evidence of an effect of distraction |

| Behavioral measures‐ distress | See comment | The mean level of behavioral distress with distraction was 0.44 standard deviations lower (0.84 to 0.04 lower) | 500 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c | This result equates to a small to moderate difference in favor of distraction |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **One 'rule of thumb' for interpreting the relative effect is that 0.2 represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate difference and 0.8 a large difference. CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

a Downgraded once for serious study limitations: most trials had unclear/high risk of bias in blinding, allocation concealment and/or selective reporting of outcomes. b Downgraded once for inconsistency due to moderate heterogeneity (I2) > 45%. c Downgraded once for imprecision: analysis based on < 400 participants per group.

d Downgraded twice for inconsistency due to considerable heterogeneity (I2) > 90%.

Summary of findings 2. CBT‐combined compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

| CBT‐combined compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents | ||||||

| Patient or population: children aged 3‐18 years with mixed medical (acute or chronic illness) or generally healthy undergoing immunization, intravenous insertion, venipuncture, bone marrow aspiration, insulin injection, or dental local anesthetic Setting: hospital (inpatient/outpatient/emergency department), community clinic, or school Intervention: CBT‐combined Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments** | |

| Risk with control | Risk with CBT‐combined | |||||

| Self‐reported pain | The mean level of self‐reported pain in the control group ranged from 0.84 to 8.4 (adjusted to a 0 to 10 scale). | The mean level of self‐reported pain with combined CBT was 0.27 standard deviations lower (0.58 lower to 0.03 higher) | 1359 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,b | There is no evidence of an effect of combined CBT | |

| Self‐reported distress | See comment | The mean level of self‐reported distress with combined CBT was 0.26 standard deviations lower (0.56 lower to 0.04 higher) | 234 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | There is no evidence of an effect of combined CBT | |

| Observer‐reported pain | See comment | The mean level of observer‐reported pain with combined CBT was 0.52 standard deviations lower (0.73 to 0.30 lower) | 385 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | This result equates to a moderate difference in favor of combined CBT | |

| Observer‐reported distress | See comment | The mean level of observer‐reported distress with combined CBT was 0.08 standard deviations higher (0.34 lower to 0.50 higher) | 765 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,b | There is no evidence of an effect of combined CBT | |

| Behavioral measures‐ pain | See comment | The mean level of behavioral pain with combined CBT was 0.65 standard deviations lower (2.36 lower to 1.06 higher) | 95 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,d | There is no evidence of an effect of combined CBT | |

| Behavioral measures‐ distress | See comment | The mean level of behavioral distress with combined CBT was 0.40 standard deviations lower (0.67 to 0.14 lower) | 1105 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,b | This result equates to a small to moderate difference in favor of combined CBT | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **One 'rule of thumb' for interpreting the relative effect is that 0.2 represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate difference and 0.8 a large difference. CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a Downgraded once for serious study limitations: most trials had unclear/high risk of bias in blinding, allocation concealment and/or selective reporting of outcomes. b Downgraded once for inconsistency due to moderate heterogeneity (I2) > 45%. c Downgraded once for imprecision: analysis based on < 400 participants per group. dDowngraded twice for imprecision: analysis based on < 100 participants per group.

Summary of findings 3. Hypnosis compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

| Hypnosis compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 3‐16 years with chronic illness (cancer) or generally healthy undergoing bone marrow aspirations, lumbar punctures, venipuncture, or local dental anesthetic Setting: hospital (inpatient/outpatient), community clinic Intervention: hypnosis Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments** | |

| Risk with control | Risk with hypnosis | ||||

| Self‐reported pain | The mean level of self‐reported pain in the control group ranged from 4.17 to 8.6 (adjusted to a 0 to 10 scale) | The mean level of self‐reported pain with hypnosis was 1.40 standard deviations lower (2.32 to 0.48 lower) | 176 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | This result equates to a large difference in favor of hypnosis |

| Self‐reported distress | See comment | The mean level of self‐reported distress with hypnosis was 2.53 standard deviations lower (3.93 to 1.12 lower) | 176 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,c,d,e | This result equates to a large difference in favor of hypnosis |

| Observer‐reported pain | See comment | See comment | See comment | .‐ | This outcome was not assessed in any study |

| Observer‐reported distress | See comment | See comment. | 36 (1 RCT) | ‐ | This outcome was assessed in one study only |

| Behavioral measures‐ pain | See comment | The mean level of behavioral pain with hypnosis was 0.38 standard deviations lower (1.57 lower to 0.81 higher) | 69 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c | There is no evidence of an effect of hypnosis |

| Behavioral measures‐ distress | See comment | The mean level of behavioral distress with hypnosis was 1.15 standard deviations lower (1.76 to 0.53 lower) | 193 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | This result equates to a large difference in favor of hypnosis |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **One 'rule of thumb' for interpreting the relative effect is that 0.2 represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate difference and 0.8 a large difference. CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

a Downgraded once for serious study limitations: most trials had unclear/high risk of bias in blinding, allocation concealment and/or selective reporting of outcomes. b Downgraded once for inconsistency due to moderate heterogeneity (I2) > 45%. c Downgraded twice for imprecision: analysis based on < 100 participants per group. d Downgraded once for possibility of publication bias given that almost all trials are from one expert group. e Downgraded twice for inconsistency due to considerable heterogeneity (I2) > 90%.

Summary of findings 4. Preparation/information compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents.

| Preparation/information compared to control for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 3‐12 years with mixed medical (acute or chronic illness) or unclear diagnoses undergoing venipuncture or intravenous insertion Setting: hospital (outpatient/emergency department) or community clinic Intervention: preparation/information Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments** | |

| Risk with control | Risk with preparation/information | ||||

| Self‐reported pain | The mean level of self‐reported pain in the control group ranged from 2.6 to 6.12 (adjusted to a 0 to 10 scale) | The mean level of self‐reported pain with preparation/information was 0.18 standard deviations lower (0.60 lower to 0.23 higher) | 313 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c | There is no evidence of an effect of preparation/information |

| Self‐reported distress | See comment | See comment | See comment | ‐ | This outcome was not assessed in any study |

| Observer‐reported pain | See comment | The mean level of observer‐reported pain with preparation/information was 0.40 standard deviations lower (0.98 lower to 0.18 higher) | 259 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b,c | There is no evidence of an effect of preparation/information |

| Observer‐reported distress | See comment | See comment | 100 (1 RCT) | ‐ | This outcome was assessed in one study only |

| Behavioral measures‐ pain | See comment | See comment | 39 (1 RCT) | ‐ | This outcome was assessed in one study only |

| Behavioral measures‐ distress | See comment | See comment | 54 (1 RCT) | ‐ | This outcome was assessed in one study only |