Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common condition among patients in intensive care units (ICUs), and is associated with high death. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is a blood purification technique used to treat the most severe forms of AKI. The optimal time to initiate RRT so as to improve clinical outcomes remains uncertain.

This review complements another Cochrane review by the same authors: Intensity of continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different timing (early and standard) of RRT initiation on death and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with AKI.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant’s Specialised Register to 23 August 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also searched LILACS to 11 September 2017.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We included all patients with AKI in ICU regardless of age, comparing early versus standard RRT initiation. For safety and cost outcomes we planned to include cohort studies and non‐RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted independently by two authors. The random‐effects model was used and results were reported as risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We included five studies enrolling 1084 participants. Overall, most domains were assessed as being at low or unclear risk of bias. Compared to standard treatment, early initiation may reduce the risk of death at day 30, although the 95% CI does not rule out an increased risk (5 studies, 1084 participants: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.13; I2 = 52%; low certainty evidence); and probably reduces the death after 30 days post randomisation (4 studies, 1056 participants: RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.10; I2= 29%; moderate certainty evidence); however in both results the CIs included a reduction and an increase of death. Earlier start may reduce the risk of death or non‐recovery kidney function (5 studies, 1076 participants: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.05; I2= 54%; low certainty evidence). Early strategy may increase the number of patients who were free of RRT after RRT discontinuation (5 studies, 1084 participants: RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.40; I2= 58%; low certainty evidence) and probably slightly increases the recovery of kidney function among survivors who discontinued RRT after day 30 (5 studies, 572 participants: RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence) compared to standard; however the lower limit of CI includes the null effect. Early RRT initiation increased the number of patients who experienced adverse events (4 studies, 899 participants: RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.16; I2 = 0%; high certainty evidence). Compared to standard, earlier RRT start may reduce the number of days in ICU (4 studies, 1056 participants: MD ‐1.78 days, 95% CI ‐3.70 to 0.13; I2 = 90%; low certainty evidence), but the CI included benefit and harm.

Authors' conclusions

Based mainly on low quality of evidence identified, early RRT may reduce the risk of death and may improve the recovery of kidney function in critically patients with AKI, however the 95% CI indicates that early RRT might worsen these outcomes. There was an increased risk of adverse events with early RRT. Further adequate‐powered RCTs using appropriate criteria to define the optimal time of RRT are needed to reduce the imprecision of the results.

Timing of initiation of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury

What is the issue?

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is very common among patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU); it is associated with high death rates and characterised by the rapid loss of the kidney function. Patients with AKI show increased levels of serum uraemic toxins (creatinine and urea), serum potassium and metabolic acids, accumulation of water and in the most cases a reduction in urine output. In this population these chemicals and fluid overload are related to increased rates of death. Theoretically, early removal of toxins and excess water from the bloodstream might improve patient outcomes (such as death rate and recovery of kidney function).

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is a blood purification technique that enables removal of excess water and toxins. RRT involves blood being diverted from the patient via a catheter (a hollow, flexible tube placed into a vein) through a filtering system which removes excess water and toxins; purified blood is then returned to the patient via the catheter. Early initiation of RRT improves the removal of toxins and excess water. The aim of this review was to investigate the effect of different timing of RRT initiation (early or standard) on death, recovery of kidney function, and adverse events in people with AKI who are critically ill.

What did we do?

We searched the literature up until August 2018 and identified five studies enrolling 1084 critically ill patients with AKI that were evaluated in this review.

What did we find?

Five randomised studies enrolling 1084 participants were included in our review. Compared to standard, early initiation of RRT may reduce the risk of death, may increase the recovery of kidney function, or increase the risk of adverse events in patients with AKI in intensive care units. Nevertheless, in death the early initiation of RRT showed a range of values that included benefit (decrease death), as well as harm (increase death).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Early versus standard renal replacement therapy (RRT) initiation for acute kidney injury (AKI)

| Early versus standard RRT initiation for AKI | |||||

| Patient or population: patients with AKI Setting: ICU Intervention: early initiation of RRT Comparison: standard RRT | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with standard initiation | Risk with early initiation | ||||

| Death at day 30 | 414 per 1.000 | 344 per 1.000 (253 to 468) | RR 0.83 (0.61 to 1.13) | 1084 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Death after 30 days | 487 per 1.000 | 448 per 1.000 (370 to 536) | RR 0.92 (0.76 to 1.10) | 1056 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 |

| Death or non recovery kidney function at day 90 | 541 per 1.000 | 449 per 1.000 (357 to 568) | RR 0.83 (0.66 to 1.05) | 1078 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Patients free of RRT after discontinuing RRT (all patients) Follow‐up: 90 days | 469 per 1.000 | 530 per 1.000 (427 to 656) | RR 1.13 (0.91 to 1.40) | 1084 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Number of patients with any adverse events Follow‐up: 90 days | 657 per 1.000 | 723 per 1.000 (683 to 769) | RR 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) | 437 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| ICU length of stay Follow‐up: 30 days | The mean length of stay was 14.6 days | MD 1.78 days lower (3.7 lower to 0.13 higher) | ‐ | 1056 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; ICU: intensive care unit/s | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Serious inconsistency: due to moderate heterogeneity

2 Serious Imprecision: due to the CI crossed the threshold for clinically meaningful effects

Summary of findings 2.

Early initiation versus standard renal replacement therapy (RRT) for acute kidney injury (AKI): subgroup analysis

| Subgroup analysis: early initiation according to clinical‐biochemical parameters versus time criteria | |||||

| Patient or population: patients with AKI who need RRT Setting: ICU Intervention: early initiation Comparison: standard initiation of RRT | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with standard initiation | Risk with early initiation | ||||

| Death: early initiation according to clinical‐biochemical criteria Follow‐up: 30 days | 857 per 1.000 | 146 per 1.000 (43 to 523) | RR 0.17 (0.05 to 0.61) | 28 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 |

| Death: early initiation according to time criteria Follow‐up: 30 days | 407 per 1.000 | 371 per 1.000 (318 to 432) | RR 0.91 (0.78 to 1.06) | 1049 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Risk of bias: due to an incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) limiting the internal validity of the study

2 Indirectness: the population included is restricted to people who only have surgery‐acquired AKI

3 Imprecision: due to wide CI which crossed the threshold for clinically meaningful effects

Background

This review complements another Cochrane systematic review by the same authors: Intensity of continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury (Fayad 2016).

Description of the condition

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a complex clinical entity characterised by an abrupt decline in kidney function (Mehta 2007). AKI incidence among adults admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) ranges from 5% to 20% (Joannidis 2005); in children the incidence is 10% (Schneider 2010). Despite its potential to be reversed, AKI is associated with high rates of morbidity and death (Bagshaw 2007). Renal replacement therapy (RRT) has become a form of renal support for critically ill patients with AKI (Wald 2015). Despite advances in clinical care and RRT the presence of AKI in ICU setting is associated with poor prognosis, and requires significant healthcare resources (Sutherland 2010; Uchino 2005).

Description of the intervention

RRT is an extracorporeal blood purification therapy, intended to support impaired kidney function. We included the following RRT modalities: Continuous RRT (CRRT) slowly removes fluid (Foland 2004;Gibney 2008; Goldstein 2001) and higher molecular weight solutes efficiently over prolonged periods (Brunnet 1999;Clark 1999;Liao 2003; Sieberth 1995), and confers beneficial haemodynamic stability effects. CRRT modalities are defined by their main solute clearance mechanism. These are convection (continuous venovenous haemofiltration (CVVHF)), diffusion (continuous venovenous haemodialysis (CVVHD)), or a combination of both convection and diffusion (continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration, CVVHDF)) (Palevsky 2002).The intermittent RRT (IRRT) removes fluid and lower molecular weight solutes over short period of time (sessions of 3 to 5 hours), two or three times in a week. The diffusion is the main solute clearance mechanism. These are intermittent haemodialysis (IHD), intermittent haemofiltration (IHF), intermittent haemodiafiltration (IHDF), and intermittent high‐flux dialysis (IHFD). The hybrid therapies, also known as prolonged IRRTs, such as sustained low‐efficiency dialysis (SLED) and extended‐duration dialysis (EDD); that provides RRT for an extended period of time (6 to 18 hours), at least three times per week (Edrees 2016); includes both convective (i.e. haemofiltration) and diffusive (i.e. haemodialysis) therapies, depending on the method of solute removal (Marshall 2011). Peritoneal dialysis modality was not included.

Timing of RRT initiation is generally related to "when to start renal support in critical ill patients with AKI". A number of organisations have published practice guidelines that include statements on timing of RRT initiation in ICU settings. The Kidney Disease Improving Global outcomes (KDIGO 2012), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2013) and the French Intensive Care Society (Vinsonneau 2015) have published practice guidelines that include statements on timing of RRT initiation in ICU settings. There has been consensus on the standard initiation criteria: when life‐threatening changes in fluid, electrolyte, and acid‐based balance exist according to different guidelines; however none of the recommendations have been graded. Unfortunately, there has been little consensus on early begin of RRT in ICU‐patients with AKI. Some published studies have used urine output and serum creatinine (Sugahara 2004) or urine output and clearance of creatinine (Bouman 2002), as surrogate criteria of early initiation. Other authors have considered time to ICU admission (Bagshaw 2009), time to fulfilling AKI stage 2 within 8 hr (ELAIN 2016) or within 12 hr using a novel kidney damage biomarker neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) (STARRT‐AKI 2013), and time to fulfilling AKI stage 3 (AKIKI 2015). With poor agreement (expert opinion), NICE 2013 and Vinsonneau 2015 also published possible indicators for early renal support therapy e.g. weight "gain less than 10%, urea less than 25 mmol/litre and oliguria 0.5 ml/kg/hour or less for at least 24 hours" or "KDIGO AKI stage 2 or within 24 hr after onset of AKI of which reversibility seems unlikely, respectively". In our review, we will assign definitions given in included studies in relation to early and standard RRT initiation.

How the intervention might work

A hypothesis that timing of RRT commencement may affect survival emerged from animal and human studies over the past decade. Animal studies investigating sepsis (Mink 1995) and pancreatitis (Yekebas 2002) suggested beneficial effects on physiologic and clinical endpoints when haemofiltration was started early, simultaneously, or two hours after injury. Several observational studies investigated the effect of timing in patients with AKI; Teschan 1960 reported improved survival rates relating to RRT timing in patients commencing dialysis with low blood urea nitrogen; Gettings 1999 indicated improved survival in early haemofiltration patients with AKI related to trauma, the same was found in patients with AKI post cardiac surgery (Demirkilic 2004; Elahi 2004). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found in patients with pancreatitis that the survival was also significantly better in patients who received early haemofiltration (within 48 hours after onset of abdominal pain) than in the group with late haemofiltration (96 hours after onset abdominal pain) (Jiang 2005), while other RCTs failed to demonstrate these advantages (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

Studies assessing RRT timing (early versus standard) have reported inconsistent results: earlier studies indicated significant improvements in survival and kidney function recovery; yet others, including RCTs and meta‐analyses, did not find these benefits. We investigated the relationship between different timing of RRT initiation and clinical outcomes for critical patients with AKI. Review evidence could have direct relevance to guide clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different timing (early and standard) of RRT initiation on death and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with AKI.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs looking at RRT modalities for people with AKI in ICU settings were eligible for inclusion. For outcomes such as safety and costs, non‐RCTs and cohort studies were also to be included if sufficiently high quality, sampling was clearly described, patients characterised, proportions of patients experiencing any adverse events or who dropped out because of adverse events was adequately reported, co‐interventions were described, and at least 80% of patients included were analysed after treatment.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included all patients with AKI in ICU being treated with RRT regardless of age and gender. We assigned AKI definitions cited by the included studies.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients who received dialysis treatment before admission to ICU, patients admitted for drug overdose (doses exceeding therapeutic requirements), or with acute poisoning (all toxins).

Types of interventions

We compared early (intervention group) versus standard (control) initiation in CRRT and IRRT. We excluded peritoneal dialysis modality. The criteria of time were defined as published in the original publications.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death

Death from any cause at days 7, 15, 30, 60 and 90

Death or non‐recovery kidney function at day 90.

Recovery of kidney function

Numbers of patients free of RRT after discontinuing RRT

Numbers of patients free of RRT after discontinuing RRT at days 30, 60 and 90.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

Numbers of patients experiencing any adverse events

Numbers of patients who dropped out because of adverse events (technique or patient‐dependent factors)

Numbers of patients with intervention‐related complications (e.g. disequilibrium, hypokalaemia, hypophosphataemia, hypocalcaemia, bleeding, hypotension)

Numbers of patients with catheter‐related complications.

We looked for differences in overall drop‐out rates and any adverse effects by type (mild or severe). We defined adverse events severity where medical therapeutic interventions were implied in reporting. Withdrawals due to protocol violation or loss to follow‐up were not included in counts of adverse events.

Length of stay

Days in hospital

Days in ICU.

Cost

We planned to assess costs of RRT modalities including:

Type and number of dialyser filters

Use or no use of anticoagulation

Types of anticoagulation and anticoagulants

Use of replacement fluid

Number of days on RRT.

All costs were to be reported in international monetary units.

Cost per day of RRT

Length of hospital stay with RRT

Length of ICU stay with RRT.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 23 August 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources. .

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP). Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register were identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference, proceedings and current awareness alert, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms and strategies used for this review.

Searching other resources

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences) (from March 1980 to September 2017)

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies with potential relevance to the review. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that could include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and if necessary, the full text of these studies to determine which satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐ English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data was used. We resolved any discrepancy by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For normally distributed outcomes, we calculated summary estimates of treatment effects using the inverse variance method. For dichotomous outcomes (death, kidney recovery and adverse events) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (length of stay, cost) the mean difference (MD) was used or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales were used. The results were interpreted taking into account the size of the effect (magnitude or importance) (see CKT 2017; EPOC 2013).

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing to corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last‐observation‐ carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If possible, funnel plots were to be used to assess the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data were to be pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (such as intervention, parameters to define early or standard initiation, participant and study quality). Heterogeneity among participants could relate to age, gender, fluid overload (< 10% and > 10% in body weight relative to baseline), and timing of RRT for AKI in homogenous subpopulations such as cardiac surgery or sepsis patients, effects of early initiation on severity of illness. We used appropriate scores of illness severity, such as Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM), Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (Apache), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), and Cleveland Clinic ICU Acute Renal Failure (CCF). Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed using descriptive techniques. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared with no treatment or another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). One summary of findings tables were created. Summary of findings table 1 summarizes the main findings for the comparison "Early versus standard initiation of RRT for acute kidney injury". We presented the following outcomes.

Death until day 30 post‐randomisation

Death after 30 days post‐randomisation

Kidney function recovery: number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing RRT (all patients)

Number of patients with adverse events

Subgroup analysis: death in patients who start RRT according to KDIGO AKI stage criteria and in patients who start RRT according to physiological (e.g. urine output) and or biochemical criteria (e.g., urea, serum creatinine).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

We identified 208 reports from electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, Cochrane Kidney and Transplant’s Specialised Register and LILACS) to 23 August 2018 and two records from handsearching. Of these, 5 studies (10 records) (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004) were included and 84 studies (198 records) were excluded. One ongoing study was identified (NCT00837057), and one study has been completed but there are currently no publications (IDEAL‐ICU 2014). These studies and will be assessed in a future update of this review (Figure 1). There was no disagreement among authors regarding inclusion of studies.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing number of reports retrieved by database searching and the number of studies included in this review

Included studies

Five included studies (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004) enrolled a total of 1084 participants.

Study participants were all admitted to ICU. The mean age was between 62.8 and 64.5 years, and the proportion of males ranged from 59.6% to 79%. Surgery or cardio‐surgery were the primary causes of AKI in three studies (Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) and mixed (medical or surgical) in the other two studies (AKIKI 2015; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

All studies were reported between 2002 and 2016. Two were single‐centre studies (ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) and three were multicentre (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

Three studies used CRRT (Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) and two used combined therapy (intermittent and continuous) (AKIKI 2015; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

All the included studies assessed the effects of timing (early and standard) of RRT initiation on clinical outcomes of critical patients with AKI. In Bouman 2002, two of three arms received the same timing of RRT initiation (early) but differed only in the intensities of continuous therapy. For the purpose of the analysis we combined these two early treatment arms to create one early arm.

Sugahara 2004 did not report the treatment allocation of 8/36 participants that did not start the treatment. We assumed that they were evenly distributed among treatment arms (18 participants per arm). Similarly, we assumed that these 8 participants had a favourable evolution (none of them died and all of them recovered).

The included studies used a wide spectrum of definitions for early and standard initiation of RRT. Bouman 2002 and Sugahara 2004 defined early RRT initiation based on physiologic (urine output) and biochemical parameters (creatinine clearance/serum creatinine, respectively). The other three studies defined early as starting of RRT by time criteria e.g. within 8 and 12 hours of fulfilling KDIGO stage 2 (ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013) or within 6 hours of fulfilling KDIGO stage 3 (AKIKI 2015).

For full details see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 84 studies (198 records). Two of 22 reports in RENAL 2006 assessed timing however the study design was not randomised (retrospective nested cohort). Seven studies did not mandate the presence of AKI (Durmaz 2003; HEROICS 2015; Han 2015; Koo 2006; Payen 2009) or ICU stay as an inclusion criteria in the early initiation arm (Jamale 2013; Pursnani 1997) and two studies did not assess the outcomes of interest to this review (Cole 2002; Misset 1996). The remaining 74 studies did not assessing timing of RRT (See Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Included studies were generally assessed at low or unclear risk of bias for most domains; one study was assessed as high risk for incomplete outcome data (Sugahara 2004). Risk of bias assessments of the included studies are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Bouman 2002 did not provide detailed information on random sequence generation and allocation concealment processes. Authors were contacted and we were informed that random sequence generation was appropriate (computer‐generated) and sealed opaque envelopes were used for the allocation process. Three studies (AKIKI 2015; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013) were assessed as being at low risk of selection bias due to appropriate random sequence generation (computer‐generated) and for allocation concealment process. The random sequence generation and allocation concealment processes were considered unclear in Sugahara 2004 as it provided insufficient information to enable judgment.

Blinding

All included studies were assessed at low risk of detection bias (outcome measurement was unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding), and unclear risk of performance bias (insufficient information to enable judgment).

Incomplete outcome data

One study (Sugahara 2004) was assessed at high risk of attrition (data from > 20% of randomised patients were not available for inclusion in the analysis). Intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed in the other four studies.

Selective reporting

All five studies reported all expected outcomes and were considered to be at low risk of bias (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002;ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004).

Other potential sources of bias

Of the five included studies, 3 received pharmaceutical industry funding (AKIKI 2015; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013), which is a potential source of bias; however the sponsors had no role in the design, data collection, analysis and results, review or approval of the manuscript (low risk of bias). These data were not available in the remaining two studies (Bouman 2002;Sugahara 2004) (unclear risk of bias).

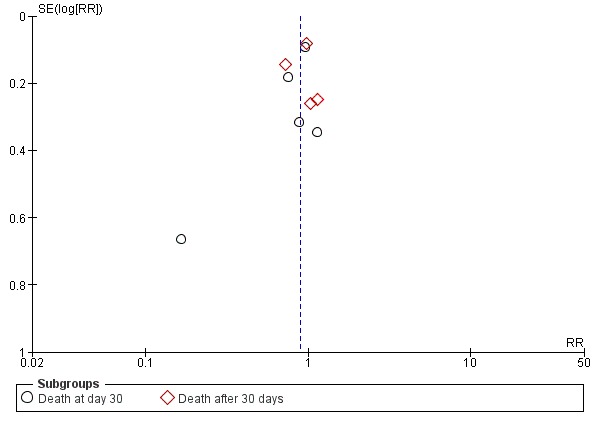

Evaluation of publication bias

We constructed a funnel plot to investigate potential publication bias. Meta‐analysis of death at day 30 was analysed. We found reasonable symmetry indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Early vs. late initiation, outcome: 1.1 Death.

Effects of interventions

The effects of early RRT initiation versus standard for main results and the quality of the evidence are summarised in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Death

All five studies assessed the effect of different timing of RRT initiation on death. These studies varied in reporting timing: 90 days (ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013); 60 days (AKIKI 2015); 28 days after randomisation (Bouman 2002); and 14 days after coronary bypass graft surgery (Sugahara 2004).

Compared to standard, early initiation of RRT may reduce the risk of death at day 30 (Analysis 1.1.1 (5 studies, 1084 participants): RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.13; low certainty evidence). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 52%). We assessed the certainty of evidence as low due to concerns about imprecision and heterogeneity. However, early start probably reduces the risk of death after 30 days post‐randomisation in comparison with standard initiation (Analysis 1.1.2 (4 studies, 1056 participants): RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.10; I2= 29%; moderate certainty evidence). We assessed the certainty of evidence as moderate due to concerns about imprecision. Nevertheless, the CIs of both outcomes included a range of plausible values with clinically important benefits as well as harms (Table 1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Early versus standard initiation, Outcome 1 Death.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There was evidence of moderate heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect among the included studies that measured death at different times of randomisation. To explore heterogeneity among participants, we planned to performed pre‐specified subgroup analyses. Only data for AKI aetiology, parameters for early initiation and modalities of RRT were available.

The effect of AKI aetiology was considered using two subgroups: patients with AKI secondary to surgical causes and patients with AKI related to non‐surgical causes. Compared to standard, early RRT initiation probably reduces the risk of death in patients with non‐surgical AKI (Analysis 2.1.1 (2 studies, 719 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.13; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence), while it may reduce the risk of death in patients with AKI related to surgical causes (Analysis 2.1.2 (3 studies, 373 participants): RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.36; I2= 69%; low certainty evidence). There was no heterogeneity between groups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.90, df = 1; P = 0.34, I2 = 0%).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis: death, Outcome 1 Death by AKI aetiology.

The effect of different parameters used to define RRT initiation was assessed using two subgroups: patients starting RRT according to time to fulfilled KDIGO AKI stage 2 and 3 and patients initiating RRT according to physiological (urine output) and or biochemical parameters. Compared to standard RRT, early strategy probably reduces the risk of death in patients initiating RRT according to physiological or biochemical parameters (Analysis 2.2.1 (1 studies, 28 participants): RR 0.17; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.61; P = 0.007; low certainty evidence) and in patients starting RRT according to time criteria (Analysis 2.2.2 (4 studies, 1049 participants): RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.06; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). The heterogeneity observed in subgroup analyses could be explained by different criteria used for RRT initiation (Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 6.41; P = 0.01; I2 = 84.4%).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis: death, Outcome 2 Death by definition of early RRT initiation.

The effect of modalities of RRT was considered using two subgroups: patients with continuous renal support and patients who received mixed modalities (continuous and intermittent). Compared to standard, early RRT initiation may reduce the risk of death in patients with CRRT (Analysis 2.3.1 (3 studies, 365 participants): RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.31to 1.36); I2= 70%; low certainty evidence), while it probably slightly reduces the risk of death in patients treated with mixed modalities ((Analysis 2.3.2 (2 studies, 719 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.13; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence). Without heterogeneity between groups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.95, df = 1; P = 0.33; I2= 0%).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis: death, Outcome 3 Death by RRT modality.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies by risk of bias and large studies. When the analysis was developed taking risk of bias into account we observed that Sugahara 2004 contributed to heterogeneity, and when excluded, heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.29; I2= 20%). The reason for exclusion was incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), but the overall estimation of effect did not change, and the direction of effects remained constant. We found no changes in heterogeneity when the study with larger sample size was excluded.

Death or non‐recovery of kidney function at 90 days

This composite outcome was available from all five studies (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004). Compared with standard initiation, early initiation may reduce the risk of death or non‐recovery kidney function (Analysis 1.2 (5 studies, 1078 participants): RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.05; I2= 54%; low certainty evidence). However, the CI included both clinical benefits and harms. We assessed the certainty of evidence as low due to concerns about imprecision and heterogeneity (Table 1).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Early versus standard initiation, Outcome 2 Death or non‐recovery kidney function at day 90.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Data was not available in any of the included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies by risk of bias and large studies. When the analysis was developed taking risk of bias into account we observed that Sugahara 2004 contributed to heterogeneity, and when excluded, heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.53; I2= 0%). The reason for exclusion was study limitation (attrition bias), but the overall estimation of effect did not change, and the direction of effects remained constant. We found no changes in heterogeneity when the study with larger sample size was excluded.

Recovery of kidney function

Five studies reported information on recovery of kidney function (in all patients and among patients’ survivors). Studies varied in reporting of kidney recovery timing: at 90 days after randomisation (AKIKI 2015; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013), 28 days or at hospital discharge (Bouman 2002), or 14 days after coronary bypass graft surgery (Sugahara 2004).

Compared to standard, early RRT initiation may increase the numbers of patients who were free of RRT after RRT discontinuation (Analysis 1.3.1 (5 studies, 1084 participants): RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.40; I2= 58%; low certainty evidence). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2= 58%). We assessed the certainty of evidence as low due to concerns about imprecision and heterogeneity.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Early versus standard initiation, Outcome 3 Recovery of kidney function.

Among survivors who discontinued RRT after day 30, early initiation of RRT probably slightly increases the recovery of kidney function compared to standard (Analysis 1.3.2 (5 studies, 572 participants): RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence). We assessed the certainty of evidence as moderate due to concerns about indirectness (Table 1).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There was evidence of heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect among the included studies that measured recovery of kidney function in all patients at different times after randomisation. To explored heterogeneity among participants we planned to performed pre‐specified subgroup analyses. Only data for AKI aetiology, parameters of early initiation and modalities of RRT were available.

The effect of AKI aetiology was considered using two subgroups: patients with AKI predominantly related to surgical causes and patients with AKI related to non‐surgical causes. Compared to standard, early RRT initiation may increase the recovery of kidney function in patients with AKI related to surgical causes (Analysis 3.1.1 (3 studies, 365 participants): RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.18; I2= 74%; low certainty evidence), while it probably slightly increases the recovery of kidney function in patients with non‐surgical AKI (Analysis 3.1.2 (2 studies, 719 participants): RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.20; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence). There was no heterogeneity between groups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.71, df = 1; P = 0.40; I2= 0%).

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: recovery of kidney function, Outcome 1 Recovery of kidney function by AKI aetiology.

The effect of different parameters used to define early RRT initiation was assessed by two subgroups: patients who started RRT according to time criteria (time to fulfilled KDIGO AKI stage 2 and 3) and patients initiating RRT according to physiological (urine output) and or biochemical parameters. Compared to standard, early initiation RRT probably improves recovery of kidney function in patients starting RRT according to time criteria (Analysis 3.2.1 (4 studies, 1050 participants): RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.24; I2 = 7%; moderate certainty evidence), but had uncertain effect on kidney function recovery in patients initiating RRT according to physiological and or biochemical parameters (Analysis 3.2.2 (1 study, 28 participants): RR 5; 95% CI 1.33 to 18.8; very low certainty evidence). The heterogeneity between groups could be explained by different time criteria of RRT initiation (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 4.98, df = 1; P = 0.03; I2= 79.9%).

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: recovery of kidney function, Outcome 2 Recovery of kidney function by definition of early RRT Initiation.

The effect of modality of RRT was considered using two subgroups: patients with CRRT and patients who received mixed modalities (continuous and intermittent). Compared to standard, early RRT initiation may increase the recovery of kidney function in patients with CRRT (Analysis 3.3.1 (3 studies, 365 participants): RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.34; I2= 76%; low certainty evidence), and probably slightly improves kidney function in patients treated with mixed modalities (Analysis 3.3.2 (2 studies, 719 participants): RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.20; I2= 0%; moderate certainty evidence). There was no heterogeneity between groups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.89, df = 1; P = 0.35; I2= 0%).

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: recovery of kidney function, Outcome 3 Recovery of kidney function by RRT modality.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies at high risk of bias and large studies. When the analysis was developed taking risk of bias into account we observed that Sugahara 2004 contributed to heterogeneity, and when excluded, heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.24; I2= 29%). The reason for exclusion was study limitation (attrition bias), but the overall estimation of effect did not change, and the direction of effects remained constant. We found no changes in heterogeneity when the study with larger sample size was excluded.

Adverse events

The effects of timing of RRT initiation on adverse events were reported in four studies (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

Early initiation of RRT increase the number of patients who experienced adverse events compared to standard (Analysis 1.4.1 (4 studies, 899 participants): RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.16; I2 = 0%; high certainty evidence). However, it is uncertain whether early initiation of RRT increases or reduces the risk of bleeding (Analysis 1.4.2 (1 study, 106 participants): RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.50 to 5.84; very low certainty evidence) or the occurrence of thrombocytopenia (Analysis 1.4.3 (1 study, 106 participants): RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.20 to 5.35; very low certainty evidence) compared with standard initiation. We assessed the certainty of evidence as very low due to concerns about very serious imprecision and indirectness (Table 1)

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Early versus standard initiation, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

Length of stay

Four studies assessed the effect of timing on length of stay (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013).

Early initiation of RRT may reduce the number of days in ICU (Analysis 1.5.1 (4 studies, 1056 participants): MD ‐1.78 days, 95% CI ‐3.70 to 0.13; I2 = 90%; low certainty evidence) compared to standard. There was substantial heterogeneity among studies. We assessed the certainty of evidence as low due to concerns with imprecision and heterogeneity.

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Early versus standard initiation, Outcome 5 Length of stay.

Data on hospital length of stay (mean, SD) was not available in any of the included studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There was evidence of high heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect among the included studies that measured length of stay. To assess heterogeneity among participants, we performed sensitivity analyses to explore the above listed factors on the effect size. However, no data were available to conduct any of these subgroups analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies with high risk of bias and those with large sample sizes. When the analysis was developed taking studies with larger sample size into account, we observed that AKIKI 2015 contributed to heterogeneity. When excluded, heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.62; I2 = 0%). The reason for exclusion was indirectness. The effect of early initiation did not change.

Cost

This outcome was not reported by any of the included studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our systematic review and subsequent meta‐analysis examined the effect of different timing of initiation of RRT on death, kidney recovery function, length of stay, and adverse events among 1084 critically ill patients with AKI. Most of the included studies were assessed as low or unclear risk of bias for all domains. One study was at high risk bias, by incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Within the time of RRT initiation assessed, earlier start may have a beneficial effect on death at different time points post‐randomisation (day 30 or after 30 days) and kidney recovery function (in all patients) compared to standard initiation. The overall estimated effects on risk of death showed clinically important benefits (decreased death by 17% and 8%); but the CIs were sufficiently wide to include benefits and harm (imprecision), with moderate and low (I2= 51% and I2= 29%) levels of heterogeneity, respectively (inconsistency).

Earlier initiation may increase the number of patients who recovered kidney function. The magnitude of the possible benefit was clinically relevant (increased by 13%); however, CIs also included damage (imprecision), with a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2= 58%; inconsistency). In contrast, there was little or no difference to kidney recovery among survivors between treatments. However, reporting kidney recovery among survivors alone does not preserve the previously achieved randomisation. Therefore, the interpretation of this results may be misleading given death is a competing endpoint for recovery of kidney function in patients with high short‐term risk of death (indirectness).

Earlier initiation increased the number of patients who experienced adverse events compared to standard strategy (increased risk by 10%), CIs included harm between 3% to 16%, although it had uncertain effects on other adverse events (bleeding or thrombocytopenia) when compared to standard initiation.

In relation to length of stay, early initiation may reduce the number of days in ICU in patients with AKI. This result should be interpreted with caution owing to the high level of heterogeneity found (I2= 90%; inconsistency). Some studies have reported days in hospital and days in ICU, but in this population death is a competing endpoint for length of stay.

With focus on the size (magnitude and importance) of the effect estimate, we observed that early initiation may have beneficial effects on death and recovery of kidney function, while it increased the risk of adverse events; however, all results (except adverse events) were imprecise because the CIs crossed both the important effect threshold and the no difference threshold.

An important limitation of this systematic review was the moderate to high heterogeneity found in the main results, as death at day 30 (I2= 52%), death or non‐recovery of kidney function in all patients at 30 or more days (I2= 54%), recovery of kidney function in all patients (I2 = 58%), and ICU length of stay (90%). There was no heterogeneity identified for adverse events and recovery of kidney function among survivors.

We explored this heterogeneity by prespecified subgroup analyses; by aetiology of AKI; according to criteria used to define timing of RRT initiation; and by modalities of RRT. The subgroup by criteria of time of RRT initiation was identified as a source of heterogeneity in the size of the effect observed in death and recovery of kidney function (Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 6.41; P = 0.01; I2 = 84.4% and Chi2 = 4.98; P = 0.03; I2= 79.9%, respectively). These results should be interpreted with caution owing to the fact that only one small study reported these data.

In the subgroup of aetiology of AKI, we observed an important reduction on death rate (34%) in patients with surgery‐acquired compared to those patients with non‐surgery‐acquired AKI (5%), but there were not statistically significant differences between groups. The surgical AKI‐population should be taken into account in future researches.

We were not able to explore other subgroup analyses due to insufficient data.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

See Description of studies; Characteristics of included studies

Five RCTs (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004) evaluated the effect of different times of RRT initiation on death, recovery of kidney function, length of stay, and adverse events in critically ill patients with AKI. Three studies (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; STARRT‐AKI 2013) have not demonstrated beneficial effects on clinical outcomes with an earlier initiation of RRT. In contrast, two other studies (ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) favoured earlier strategy. These results are consistent with those reported in our review.

Disparity and the heterogeneity found in these results among the studies probably may be explained by several factors such as differences in the methodological quality of studies, sample size, patient characteristics, illness severity, modalities, delivered dialysis dose, and heterogeneous definitions of timing of RRT initiation.

Thirty six patients with AKI following coronary bypass surgery (Sugahara 2004) were randomised to early group when the urine output remained ≤ 30 mL/h for three consecutive hours and their serum creatinine had increased by ≥ 0.5 mg/dL/d whereas in the late group RRT was started when urine output fell to < 20 mL/h for at least 2 hours. Only 28 patients were analysed (14 in each group) and effectively received protocol treatment; Of the patients treated per protocol, only 2 patients (14%) in the early group died at 2 weeks compared with 12 patients (86%) in the late arm. We observed some limitations in this study: an incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) (limiting the internal validity); a low incidence of patients with AKI‐related to sepsis; and a non‐validated short‐term outcome (limiting the external validity).

In ELAIN Study 2016, 231 critically ill patients with AKI were randomised to initiation of RRT either within 8 hours of diagnosis of KDIGO stage 2 AKI (early), or within 12 hours of reaching KDIGO stage 3 AKI, or when specific metabolic and clinical indications were present (delayed). Death at day 90 was significantly lower among patients of early initiation arm compared with those in the delayed initiation arm (from 39.3% versus 54.7%; P = 0.03). Similarly benefits were observed on recovery of kidney function in survivors (early 53.6& versus delayed 38.7%; P = 0.02); RRT duration (9 versus 25 days; P = 0.04) or hospital length of stay (51 versus 82 days P = 0.001) but not in RRT dependence or ICU length of stay. The death difference (15.4%) observed in favour of early treatment exceeds the survival benefit expect in this population and is probably related to the high incidence of patients with postsurgical AKI, limiting the external validity. It is interesting to note that only 9% of the patients randomised to the late‐arm were never treated with RRT, because they spontaneously recovered or died. These studies provide support towards earlier initiation of RRT in surgical patients with postsurgical AKI but do not completely answer the question when to the optimally initiate renal support in all ICU patients. Additionally, both studies (ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) were unblinded and single‐centre (limiting the internal and external validity respectively).

In contrast, three studies did not demonstrate any effect of timing (early versus standard) of RRT initiation on survival and recovery of kidney function. Bouman 2002 conducted a small study evaluating both intensity and timing of initiation of CVVHF in 106 critical patients with AKI. There were no differences on the survival, recovery of kidney function, length of stay and adverse events for either initiation time or intensity. The survival at day 28 was greater than expected (69% to 75% in all groups) and was probably associated to low incidence of patients with AKI‐related to sepsis or it might be attributed to the closed format of the ICUs (limiting the external validity). The recovery of kidney function (based on independence of RRT) was 100% in all survivors. Of note, 6 out of 36 patients assigned to late therapy were never treated with RRT; 4 recovered kidney function and 2 died before fulfilling the criteria for late strategy. The study was underpowered to definitive detect differences due to the small sample size. STARRT‐AKI 2013 was a multicentre RCT comparing accelerated RRT initiation (12 hours or less from eligibility) with standard strategy for starting RRT based on persistent AKI and or the development of more conventional indications. They found no difference in death at 90 days, recovery of kidney function and adverse events (39.6% versus 44.2%). Only 25% of patients randomised to standard RRT strategy recovered kidney function spontaneously with no need to start RRT; therefore, an accelerated treatment is probably to expose some patients to unnecessary RRT. The study was underpowered to detect differences (non‐inferiority of delayed RRT) in clinically important outcomes due to the small sample size. Finally, AKIKI 2015 was a multicentre (31 ICUs) unblinded RCT which assessed whether a delayed strategy may improve outcomes in critically ill AKI patients. A total of 620 patients were randomised to either initiate RRT within 6 hours of fulfilling KDIGO stage 3 AKI (early) or not begin renal support unless specific clinical or metabolic indications for RRT were present (delayed). This study reported no beneficial effect on recovery of kidney function and death at 60 days with delayed strategy. It is important to note that 51% of patients in the delayed arm did not receive RRT. This cohort had a lower death rate (37.1%) when compared with patients who received either early (48.5%) or delayed (61.8%) RRT.

ELAIN 2016 and AKIKI 2015 are important contributions towards informing practice on this question; however, their contradictory results require careful interpretation. The patients enrolled in ELAIN 2016 had greater severity of illness as assessed by Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, with lower rates of severe sepsis or sepsis shock and had AKI related to postsurgical cause, whereas patients in AKIKI 2015 were predominantly medical AKI (80%). The RRT management was per protocol only in ELAIN 2016; selection of modalities, dialysis dose were to the criteria of each site, but monitored in accordance with French guidelines. The relevant difference between ELAIN 2016 and AKIKI 2015 was their criteria for timing of RRT initiation, ELAIN 2016 commenced RRT after stage 3 AKI (delayed strategy) and while in AKIKI 2015 the threshold for early initiation was stage 3 AKI.

Although the analyses included data obtained from a comprehensive and rigorous search, we identified gaps in several areas. The majority of participants in the included studies were adults, limiting the applicability of our finding to children. In general, the incidence of AKI secondary to sepsis in ICU is high; however, in three studies it was observed that the majority of patients had post‐surgical AKI, and relatively few had sepsis or pre‐existing chronic kidney disease, limiting the applicability of our results to general ICU population. Two included studies were single‐centre and all were unblinded, limiting external and internal validity of the results.

There were large variations in the definition of timing of RRT initiation among included studies. Heterogeneous indicators such as different serum urea or serum creatinine levels, urine output, time from randomisation and time to fulfilling KDIGO AKI stage, remain widely used to measure timing of RRT; however, this approach provides an incomplete assessment of optimal timing in this population and limits the applicability of our results. The long‐term kidney outcomes after hospital discharge among survivors of AKI remain poorly characterised. The studies did not report data on death and kidney function recovery in patients with pre‐existing chronic kidney disease and with low or intermediate scores of severity of illness.

The results on length of stay (days in hospital and in the ICU) and recovery of kidney function should be interpreted with caution, especially when the death risk is taken into account in this high‐risk population.

Data on number of patients with adverse events were limited and only provided by four studies in our review. We were unable to address all of the objectives of this review due to the lack of data in the included studies.

Taking these results into account, it is important to know when early RRT initiation may be essential (to improve outcomes) or unnecessary treatment for AKI‐patients in ICU (to increase potential harms).

We included only RCTs with the purpose of reducing bias.

Quality of the evidence

We conducted this review according to the process described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Our review was based on evidence from five RCTs (1084 participants) that compared different timing of RRT initiation in critically ill patients with AKI. The certainty evidence for our main outcomes was drawn from studies assessed at low risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment processes, incomplete outcomes data, intention to treat analysis, selective outcomes reporting, performance and detection bias and other sources of bias; and unclear risk for detection bias. One study was at high risk for incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Data comparing the effect of early RRT initiation against standard on death at day 30 or after were obtained from five and four well‐conducted RCTs respectively, but we downgraded the certainty of evidence to low, mainly due to inconsistency (I2 value of 52%) and imprecision (CIs included a range of plausible value with clinically important benefits, but also included harm); and rate moderate by imprecision for death after 30 days. Similarly, we downgraded the certainty of evidence to low for recovery of kidney function in all patients due to imprecision and inconsistency (I2 = 58%) and rate as moderate data obtained for recovery of kidney function among survivors at 30 days by indirectness (the recovery of kidney function in this high risk group is affected when the risk of death is taken into account).

Data used to assess the impact of early versus standard initiation of CRRT on adverse events were obtained from three well‐conducted RCTs, providing treatment effects with clinically important harms; we rates this as high certainty evidence. One study provided data on number of patients with bleeding and thrombocytopenia; we downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to serious imprecision and indirectness.

Length of stay was reported by four well‐conducted RCTs, but we downgraded the certainty of evidence to low due to substantial inconsistency (I2 value of 90%) and indirectness (the length of stay in this high risk group is affected when the risk of death is taken into account).

Potential biases in the review process

While this review was conducted according to rigorous methods developed by the Cochrane Collaboration, some bias may be present in the review process. We searched for all relevant studies using sensitive and validated strategies in major medical databases and grey literature sources. However, it is possible that some studies (such as unpublished data and studies with negative or no effects) were not identified. An analysis for evidence to assess the risk of publication bias was not possible for all outcomes due to the small number of studies available in each meta‐analysis (Figure 4).

Several subgroups analyses were planned to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in our review; however a lack of data prevented us from doing these analyses.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our systematic review in keeping with previous meta‐analysis on timing in RRT (Karvellas 2011; Liu 2014; Luo 2017; Wang 2012; Wang 2017) found that early initiation of RRT may have beneficial effects on death and kidney recovery function in critically ill patients with AKI compared to standard therapy. These results were not consistent with other two systematic reviews that included randomised and observational studies (Seabra 2008; Wierstra 2016) and recent meta‐analyses based only RCTs (Lai 2017; Mavrakanas 2017; Xu 2016).

The hypothesis that in critically AKI patients, especially those with acidaemia, fluid overload, or systemic inflammation, could benefit from an early RRT was proposed by several researchers. Our review has found that early strategy may have beneficial effect on death at day 30. This result is consistent with two individual RCTs (ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004), but does not agree with those reported in three multicentre RCTs (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; STARRT‐AKI 2013). It is important to note that differences in death between AKIKI 2015 and ELAIN 2016 were observed (41.6% versus 30.4% of patients at day 30 respectively). These differences may be due to several factors including: different severity and aetiology of AKI e.g. prevalence of patients with AKI‐related to surgical cause in the ELAIN 2016 or septic AKI‐patients was more frequent in AKIKI 2015 (both aetiology have different pathophysiology and prognosis), and variable criteria for defining early RRT initiation (KDIGO AKI stage 3 for AKIKI 2015 and KDIGO AKI stage 2 for ELAIN 2016). See Overall completeness and applicability of evidence.

There has been increased interest in recovery of kidney function. Indeed, lack of recovery of kidney function implies the need for long‐term dialysis associated with low quality of life. Our review has found that early strategy may have beneficial effect on recovery of kidney function in all patients. This finding is consistent with two individual RCTs (ELAIN 2016; Sugahara 2004) and does not agree with other three multicentre RCTs (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002; STARRT‐AKI 2013). Differences on recovery of kidney function between studies may be due to the same factors related above. However, in patients with a high short‐term death risk, the interpretation of this result may be misleading given that death is a competing endpoint for recovery of kidney function (Palevsky 2005).

Patients with AKI have a longer hospital stay. In our review, earlier strategy may reduce ICU length of stay, this result is consistent with four individual RCTs (Bouman 2002; ELAIN 2016; STARRT‐AKI 2013; Sugahara 2004) and does not agree with those reported of one RCT (AKIKI 2015). However, the length of stay in this high risk population may be affected when death is taken into account.

There was an increased risk in the number of patients who have any adverse events with early initiation of RRT compared with standard. Our results were consistent with other two RCTs (AKIKI 2015; Bouman 2002). This outcome was not examined by previous systematic reviews.

Our review has an important limitation due to the significant heterogeneity observed in the main outcomes. We explored heterogeneity but found no association between effect estimate and different subgroup analysed (aetiology of AKI, modality of AKI) in agreement with other reviews (Karvellas 2011; Seabra 2008; Wierstra 2016), except for criteria of time of RRT initiation subgroup in keeping with recent review (Luo 2017). We were unable to address all of the pre‐specified subgroup analyses of this review due to the lack of data in the included studies.

Previous reviews explored the effect of time to initiation RRT in patients with AKI; however, these reviews included studies that we excluded from our review due to: different inclusion criteria applied e.g. hospitalised patients were not in an ICU setting (Pursnani 1997) or did not require AKI for enrolment in early arm (Durmaz 2003; HEROICS 2015; Jamale 2013; Koo 2006) and differences in the methodological studies design (cohort studies). Although the abundance of cohorts studies provided more power (increases the sample size) to find significant clinical differences between both treatments, these studies have an important limitations: patients between treatments group were different e.g. patients who would have been assigned to late arm treatment might have died before initiating the therapy, while others who lived enough to be assigned to the late group might have been less sick than those or with a high likelihood of recovering kidney function without RRT; and a relevant point, the patients do not have the same opportunity to receive early or standard treatment(allocation or selection bias). Consequently, to minimise the risk of bias in our review, we included only randomised studies for main outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

With available data of included RCTs, early RRT initiation may have beneficial effects on death or recovery of kidney function; although in both results the CIs included clinical benefits and harm; however, there was an increased risk of adverse events compared to standard therapy. The absence of high quality evidence of efficacy and the possibility of increased adverse events does not support the routine use of early RRT in critically ill patients with AKI.

These results do not minimise the importance of the timing in RRT of critically ill patients, but rather reinforce the need to better understand in whom and when earlier initiation translates into improved patients outcomes. Minimal standards for the initiation of RRT appear to have been identified in different guidelines (KDIGO 2012; NICE 2013; Vinsonneau 2015); however these approaches provide an incomplete assessment of optimal timing of RRT.

Until now, given the low certainty evidence observed in the main outcomes, decision regarding the optimal timing of RRT should remain based on individual patients characteristic and clinician judgment.

Given the persistently high death rate among critically ill patients with AKI, it would be important to accurately determine the effect of timing of RRT on death. In view of the inconsistencies observed in the main outcomes and the inability to assess all possible causes of heterogeneity, it would be important to perform pooled analyses of individual patient data from all completed studies to deal with heterogeneity issues. Also, the intensity of RRT during therapy needs to be rigorously evaluated.

Adequately‐powered randomised studies that included appropriate and reproducible criteria to define the optimal time of RRT allowing improvement in clinical outcomes in AKI patients are needed. At present, two on‐going RCTs (IDEAL‐ICU 2014; NCT00837057) in this area will provide definitive answers that will guide clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the referees for their advice and feedback during the preparation of this review.

The authors would also like to thank all study authors who provided additional information about their studies and Daniel Comandé, Librarian of the Institute for Clinical Efectiveness and Health Policy (Argentina) for his help in search for the literature.

We would like to thank Cochrane Kidney and Transplant for their help with this review and especially to Marta Roque Figuls, Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre for her support and editorial advice during the reporting of this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

| LILACS |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random) |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes) |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon) |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub scales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |