Abstract

The NF-E2 p45-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor that regulates the cellular adaptive response to oxidative stress, is a target for limiting tissue damage from exposure to environmental toxins, including arsenic. In the current study, we determine whether Pterostilbene (Pts), as a potent activator of Nrf2, has a protective effect on arsenic-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human keratinocytes. Human keratinocytes (HaCaT) or mouse epidermal cells (JB6) were pretreated with Pts for 24 h prior to arsenic treatment. Harvested cells were analyzed by MTT, DCFH-DA, commercial kits, Flow cytometry assay and western blot analysis. Our results demonstrated that Pts effectively regulated the viability in HaCaT and JB6 cells, decreased the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and lipid peroxidation (MDA), and improved the NaAsO2-induced depletion of superoxide dismutase (SOD). Moreover, Pts treatment further dramatically inhibited NaAsO2-induced apoptosis, specifically the mitochondrial mediation of apoptosis, which coincided with the effective recovery of NaAsO2-induced mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) depolarization and cytochrome c release from the mitochondria. Furthermore, arsenic-induced decrease of anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl, and increase of pro-apoptotic factor Bax and Bad, as well as survival signal related factor caspase 3 activation were reversed by Pts treatment. Further mechanistic studies confirmed that Pts increased antioxidant enzyme expression in a dose-dependent manner, which was related to Nrf2 nuclear translocation. In addition, the effects of Pts on NaAsO2-induced cell viability were largely weakened when Nrf2 was knocked down. Together, our results provide evidence for the use of Pts to activate the Nrf2 pathway to alleviate arsenic-induced dermal damage.

Keywords: pterostilbene, Nrf2, arsenic, apoptosis, keratinocytes

Introduction

Arsenic, a common constituent of the Earth’s crust, affects the health and well-being of many diverse populations. Inorganic arsenic is generally considered more harmful than organic arsenic, and the most toxic arsenic compounds are in trivalent oxidation states, such as sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) and arsenic trioxide (As2O3). Previous studies have mainly focused on the carcinogenic effect of NaAsO2 and the anticancer function of As2O3 (Jiang et al., 2013). Epidemiological studies have shown that long-term exposure to NaAsO2 in contaminated drinking water increases the risk of many different types of cancer in the skin, lung, kidney and liver (Hughes et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2011). Human skin lesions associated with arsenic exposure include Bowen’s disease, pigmentation disorders, squamous cell carcinoma, verrucose hyperkeratosis and basal cell carcinoma. In addition, skin complications caused by arsenic exposure occur after an incubation period of 5–10 years and continue to develop decades after the cessation of arsenic exposure, suggesting that long-term prevention is beneficial (Haque et al., 2003).

Arsenic cancer, an archetype of skin cancer, is characterized by increased proliferation, individual cell apoptosis, and full-layered dysplasia, which can be viewed microscopically. All of these effects require the involvement of mitochondria, which contribute to energy production, ROS development, cell proliferation, and DNA damage and mutations (Lee and Yu, 2016). Previous studies have shown that exposure to inorganic arsenic salts (iAs3+) may induce oxidative stress (Zhao et al., 2013). In the context of increased oxidative stress, arsenic contributes to increased oxidative damage, apoptosis and mtDNA mutations in keratinocytes and in the tumor tissues of patients with arsenic skin cancers (Lee and Yu, 2016). Nrf2, a redox-sensitive transcription factor, plays an imperative role in the cellular redox homeostasis and oxidative stress, including increasing the expression of genes encoding antioxidant and phase 2 drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as heme oxygenase1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Kumar et al., 2014). Earlier experiments showed that the stable knockdown of endogenous Nrf2 makes the cells more sensitive to NaAsO2-induced cell death (Wang et al., 2007). In addition, numerous reports have also indicated that the antioxidant signaling pathway regulated by Nrf2 is involved in the adaptive response to inorganic arsenite-induced oxidative stress, and Nrf2 is considered to be a key factor in this response (Fu et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated that activation of Nrf2 and the Nrf2-regulated antioxidant and detoxification enzyme expression can protect HaCaT cells from arsenic-induced apoptosis and cytotoxicity (Zhao et al., 2013; Duan et al., 2016). Therefore, enhancing the Nrf2-dependent adaptive response is expected to protect against iAs (Martinez et al., 2011)+-induced toxicity and carcinogenicity.

To date, the study of natural products has contributed greatly to drug discovery, and many epidemiological studies have shown that phytochemicals found in fruits and vegetables can reduce the risk of developing various cancers (Koehn and Carter, 2005a,b; Gomez-Pinilla, 2008). In the past few decades, some studies have demonstrated the benefits of natural products in combating oxidative stress by regulating the Nrf2/ARE pathway (Lv et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Chen et al., 2018). Pterostilbene, a natural dimethylated analog of resveratrol, is found in blueberries and grapes. It has been reported to that Pts can prevent myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by reducing oxidative/nitrative stress and inflammatory responses (Yu et al., 2017). In addition, Pts protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in the skeletal muscles via decreasing the Bax/Bcl2 ratio (Cheng et al., 2016). The B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of protein, including Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, Bax, and Bad, play a key role in apoptosis (Mahieux et al., 2001). Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl are important anti-apoptotic molecules that inactivates of Bcl-2 related X protein (Bax), thereby inhibiting the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Bax then stimulates the release of caspases, triggering the final cascade of events and morphological changes in the process of cell apoptosis. Resveratrol has been reported to protect against arsenic trioxide-induced cardiotoxicity (Zhang et al., 2014). Pts has a longer half-life in vivo, and its anti-inflammatory activity and anticancer effects are stronger than those of Resv (Paul et al., 2009; Estrela et al., 2013). In addition, Pts exerts better protection than Resv against chronic UVB-induced oxidative damage (Sirerol et al., 2015). Thus, in this study, we studied the protective effects and mechanisms of Pts on arsenic-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human keratinocytes. Our results suggested that the anti-apoptosis role of Pts depends on Nrf2 activation in NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity in human HaCaT cells. Our findings are important not only for understanding the effects of Pts on NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity in human HaCaT cells, but also for developing strategies to prevent and proper treatment of chronic arsenic poisoning, including arsenic-induced skin disorders.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Pterostilbene with a purity >98% was purchased from Chengdu Pufeide Biotech Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Sodium arsenite (NaAsO2, 99.0%) and DCFH-DA were provided by Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, United States). Antibodies against Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, Bax, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Caspase-3, Bad, Cytochrome c, p-AMPK, T-AMPK, p-AKT, T-AKT, Lamin B and β-actin were supplied by Cell Signaling (Boston, MA, United States) or Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States). The MDA and SOD test kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The Annexin V fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/Propidium Iodide (PI) apoptosis kit was purchased from BD (San Jose, CA, United States). The control siRNA and Nrf2 siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, United States). Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1 were offered from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Jiangsu, China).

Cell Culture and Cell Treatment

The HaCaT cell, a spontaneously immortalized human epithelial cell line, was obtained from the China Cell Line Bank (Beijing, China). Cells were maintained in a full DMEM supplemented with 3 mM glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. The mouse epidermal cell line JB6 P+ (ATCC, CRL-2010) were cultured in EMEM containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% gentamicin. The cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°.

Cell Viability Assay

HaCaT and JB6 cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well for 24 h. To determine the preventive effect of Pts on the cell viability, cells were pretreated with Pts (7.5, 15, and 30 μM) for 1 h, and exposed to NaAsO2 (25 μM) for 20 h. Then, MTT solution was added to the plates and incubated for another 4 h, the formed blue formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO. Finally, the absorbance of MTT was measured at 570 nm with a microplate reader.

Intracellular ROS Formation Assay

Reactive oxygen species generation was measured by the DCFH-DA method. Briefly, HaCaT and JB6 cells were incubated in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) for 24 h, and then the cells were treated with 25 μM NaAsO2 and pretreated with or without Pts (7.5, 15, and 30 μM) for 24 h. Next, the cells were incubated with serum-free medium containing DCFH-DA (10 μM, Sigma) at 37°C away from light for 2 h. The fluorescence of the dye was measured using a multi-detection reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc.) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 530 nm, respectively. The treated cells were visualized directly by a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) at 200× magnification.

Intracellular MDA and SOD Assay

Intracellular lipid peroxidation (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) concentrations were measured using a commercially test kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). HaCaT and JB6 cells were grown in 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) for a 24 h incubation, and then exposed to 25 mM of NaAsO2 and pretreated with or without Pts (7.5, 15, and 30 μM) for 24 h. At the end of the handle, cells were collected into the tubes and then lysed in ice-cold PBS by sonication followed by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were used immediately for the measurements using commercially kits.

Apoptotic Cells Quantification

Quantification of apoptotic cells was performed using annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) double staining. HaCaT cells were seeded into 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) for a 24 h incubation, and then treated with 25 μM NaAsO2 with or without pretreatment with Pts as mentioned above. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, harvested by trypsin, and centrifuged at 1500 rpm/min for 5 min at 4°C. Next, cells were subjected to annexin V and PI staining, and the level of apoptosis was determined using flow cytometry (LSR II Flow Cytometer; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, United States).

Morphology of apoptotic cells was observed by fluorescence microscopy following DAPI staining. In brief, the treated cells were fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene for 15 min, cellular DNA was stained with 0.1% DAPI for 15 min, and then the cell morphology was immediately visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) at 200× magnification at the wavelengths of 364 nm for excitation and 454 nm for emission.

Western Blot Analysis

HaCaT cells were plated into 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) for a 24 h, and then treated with 25 μM NaAsO2 with or without pretreatment with Pts as mentioned above. After each experiment, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS. Whole-cell protein extracts were obtained using cell lysis buffer with 1 Mm PMSF, protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors. Nuclear protein and mitochondria protein extraction kits were purchased from Beyotime (Jiangsu, China). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay before storing the lysates at –80°C. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE (8–12%) and then transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked by 5% non-fat milk. Immunoblotting analysis was performed using specific antibodies. Then the membranes were further incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected using an ECL western blot substrate. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ gel analysis software. The experiments were repeated three times for each experimental condition.

JC-1 Assay for Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

HaCaT cells were plated into 12-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well, treated with 25 μM NaAsO2 with or without pretreatment with Pts as mentioned above. Next, the cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS, then incubated with JC-1 (10 μg/ml) at 37°C in the dark for 30 min. JC-1 fluorescence was quantified through flow cytometry, in which red JC-1 aggregates were gated in the FL2 channel and green JC-1 monomers in the FL1 channel.

Nrf2-siRNA Transfection

HaCaT cells were seeded into 6-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well until the cells fusion was approximately 40–50%. Then, the siRNA transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 was used to transiently transfect Nrf2-siRNA or Nrf2-negative control siRNA into the cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After 24 h, the transfected cells were treated with Pts for 24 h and the lysate was analyzed by Western blot.

Statistical Analysis

All results were expressed as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Differences between mean values of normally distributed data were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Pts Inhibited NaAsO2-Induced Cytotoxicity in HaCaT and JB6 Cells

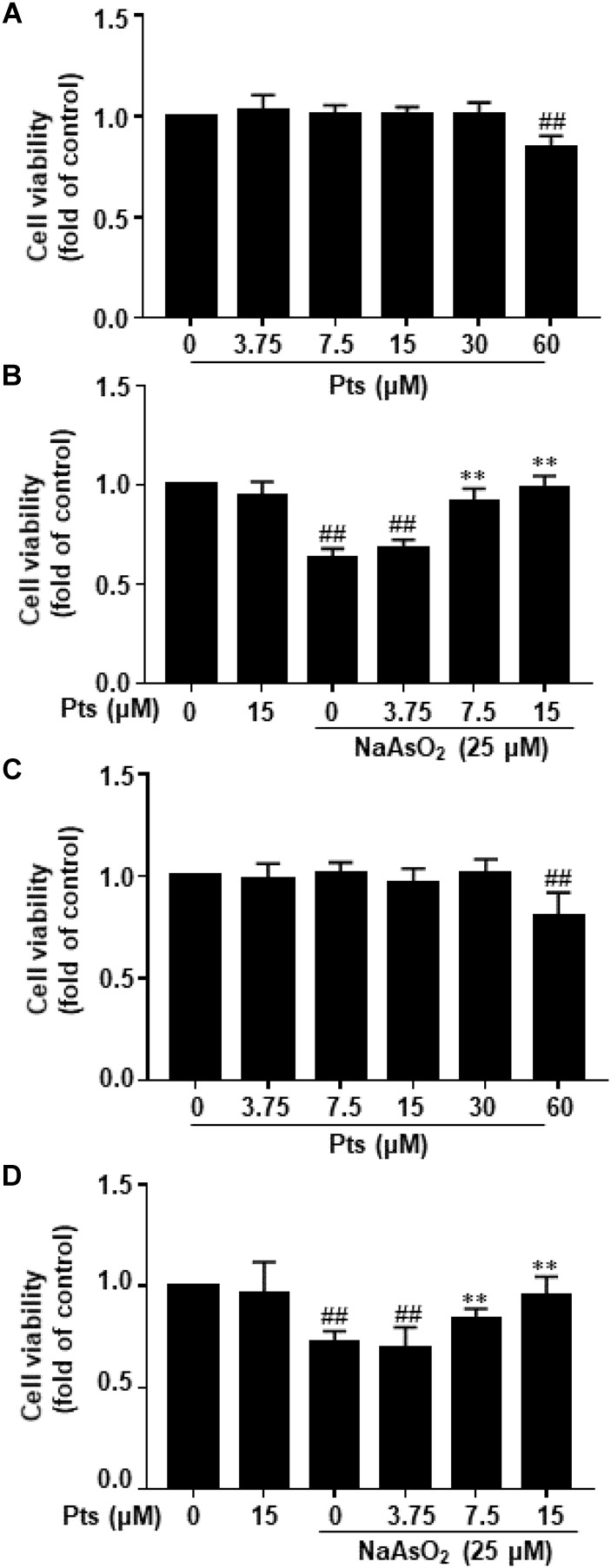

After cells were exposed to various concentrations of Pts for 24 h, Pts at 7.5–30 μM did not decrease the viability of HaCaT and JB6 cells compared to the control, although there was a decrease in cell viability at 60 μM (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 1A,C). To evaluate the protective effect of Pts against NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity, Pts (7.5, 15 and 30 μM) pretreatment was conducted before NaAsO2 (25 μM) exposure for 24 h. Our results demonstrated that Pts remarkably protected the cells from NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 1B,D).

FIGURE 1.

Protective effect of Pts pretreatment against NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity in HaCaT and JB6 cells. (A,C) The HaCaT and JB6 cells were exposed to different concentrations of Pts (7.5–60 μM) for 24 h, and then cell viability was measured by MTT assay. (B,D) HaCaT and JB6 cells were exposed to NaAsO2 (25 μM) for 24 h with or without pretreatment with Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM), and then cell viability was measured by MTT assay. The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments.##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

Pts Decreased NaAsO2-Induced ROS Generation and MDA Formation and Increased SOD Content in HaCaT JB6 Cells

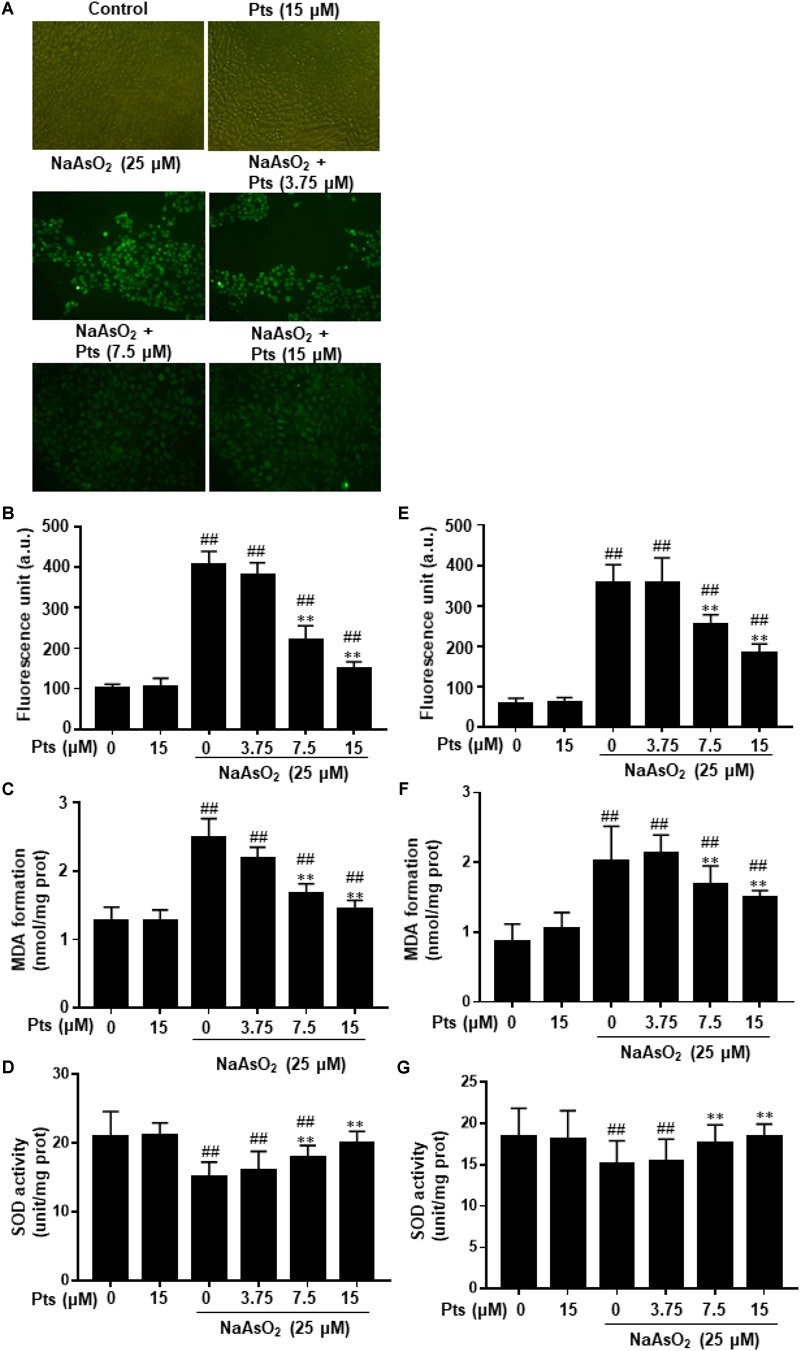

Increased intracellular ROS and oxidative stress induction were associated with arsenic-related cell damage (Gong et al., 2015). In this study, we found that NaAsO2 treatment enhanced ROS production, which was significantly inhibited by Pts pretreatment (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 2A,B,E). Lipid peroxidation was assessed by measuring the amounts of MDA, a common end product of lipid peroxidation. SOD is thought to be an essential antioxidant that protects against arsenic-induced oxidative damage. Figure 2C,D,F,G shows that NaAsO2 exposure markedly enhanced MDA generation and SOD depletion, which were reversed by Pts pretreatment (P ≤ 0.01).

FIGURE 2.

Protective effect of Pts pretreatment against NaAsO2-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT cells. The HaCaT and JB6 cells were exposed to 25 μM of NaAsO2 for 24 h with or without Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM) pretreatment. (A,B,E) ROS generation was measured by the DCFH-DA method using a multi-detection reader and fluorescence microscope at 100× magnification. Intracellular MDA levels (C,F) and SOD (D,G) activities were determined by commercial kits. The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. ##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

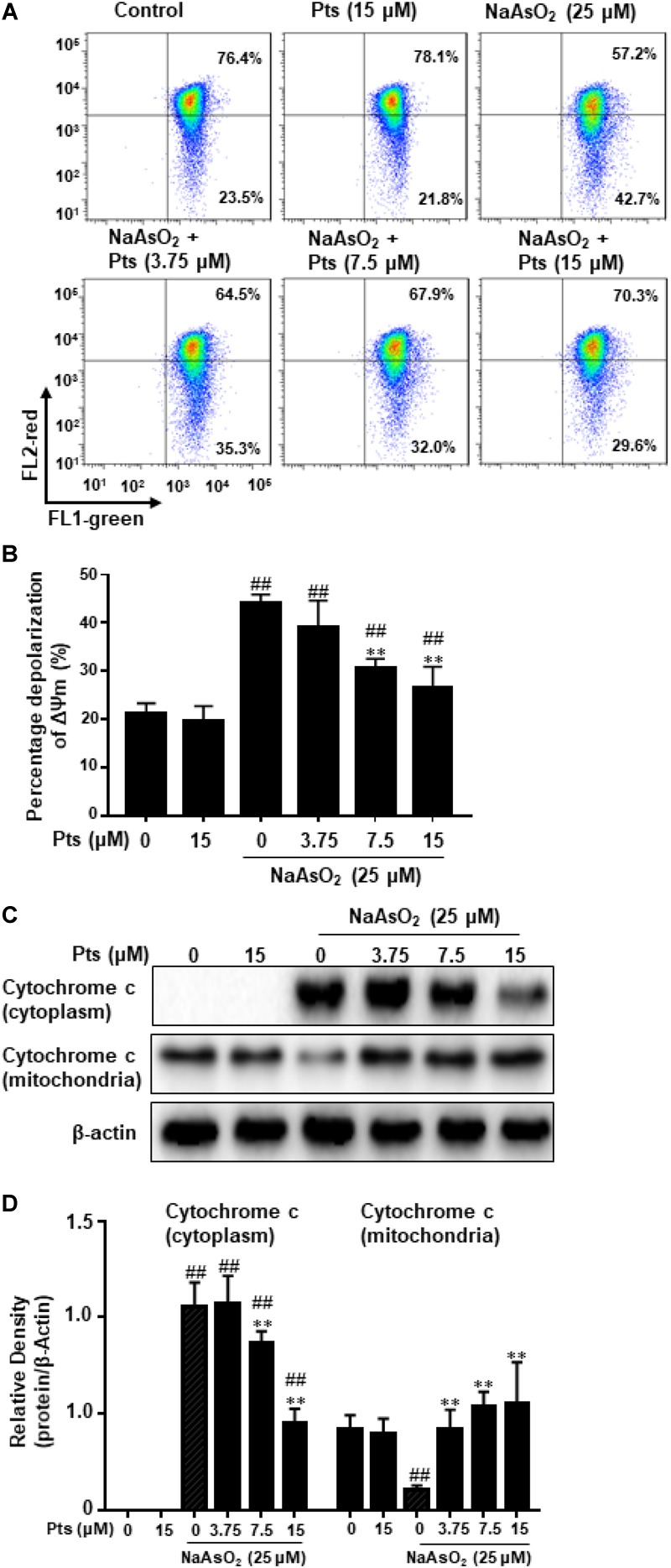

Pts Ameliorated NaAsO2-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in HaCaT Cells

Mitochondria, which play a vital role in the process of apoptosis in different cells, and the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP, ΔΨm) is associated with apoptosis. To determine whether NaAsO2-induced apoptosis in HaCaT cells occurred through a mitochondrial-derived pathway, we examined the alteration of ΔΨm and cytochrome c release in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were pretreated with Pts for 1 h and then exposed to NaAsO2 (25 μM) to induce mitochondrial dysfunction, JC-1 staining was then used to detect the change in ΔΨm. A large number of reports have showed that normal cells exhibit JC-1 red fluorescence, but the reduction of MMP caused the green JC-1 monomers to replace the red fluorescence. Compared to the control group, the ΔΨm of cells was reduced with NaAsO2 but was enhanced after pretreatment with Pts in a dose-dependent manner, which suggested that Pts significantly inhibited mitochondrial dysfunction in HaCaT cells (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 3A,B). To further determine the protective effect of Pts on mitochondria, western blot analysis was used to evaluate the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol. As shown in Figure 3C,D, treatment with NaAsO2 increased the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol fraction clearly, while the effect was reversed by Pts pretreatment (P ≤ 0.01).

FIGURE 3.

Protective effect of Pts pretreatment against NaAsO2-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in HaCaT cells. The HaCaT cells were exposed to 25 μM of NaAsO2 for 24 h with or without Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM) pretreatment. (A) Mitochondrial membrane potentials (ΔΨm) were assessed with JC-1 staining by flow cytometry, and the percentage of cells with depolarization of ΔΨm were quantified in panel (B). (C) Cytochrome c levels in the mitochondria and cytoplasm were detected by western blot analysis, and the band densities were quantified in panel (D). The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. ##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

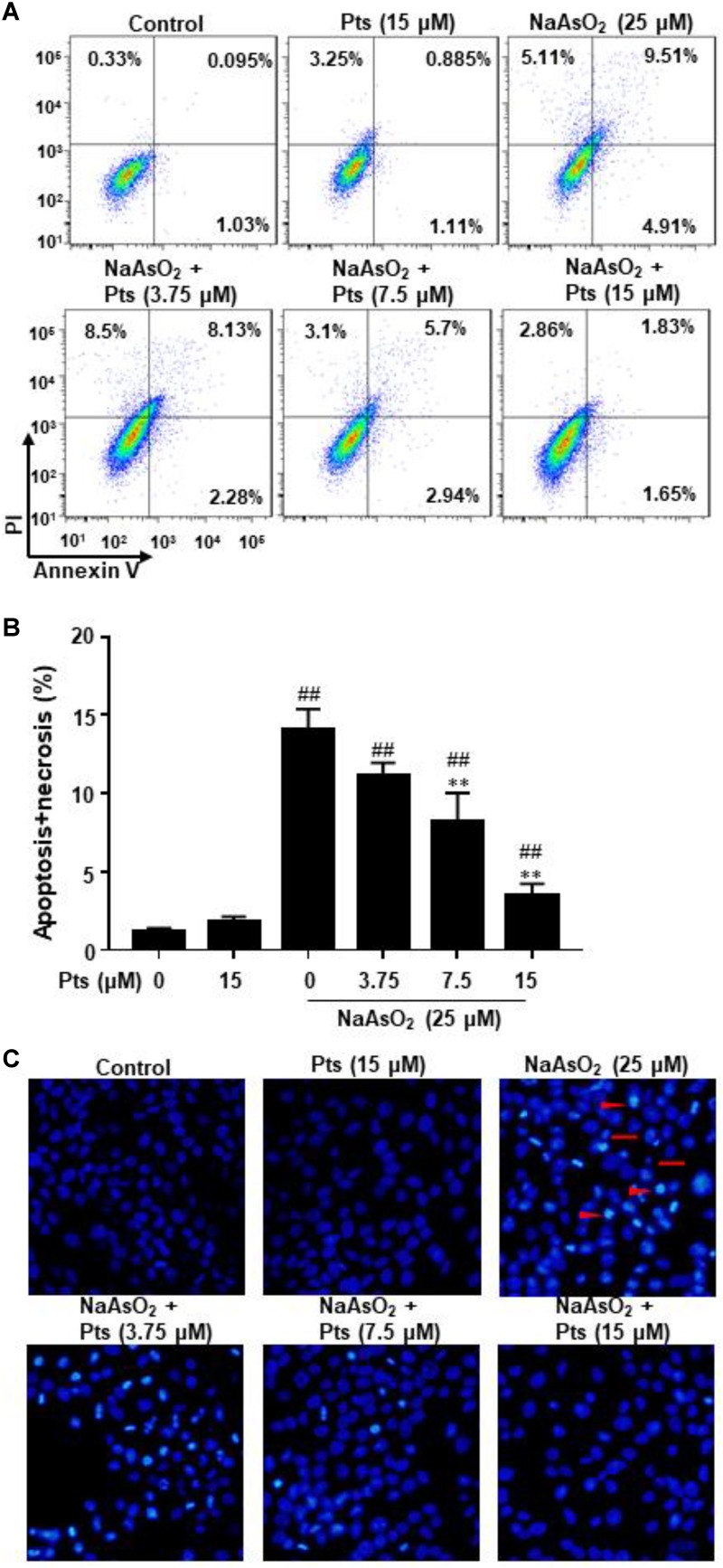

Pts Inhibited NaAsO2-Induced Cell Apoptosis in HaCaT Cells

As shown in Figure 4A,B, NaAsO2 significantly increased the incidence of cell death by promoting the apoptosis and necrosis in total cells, whereas Pts effectively reduced the apoptosis and necrosis induced by NaAsO2 in a dose-dependent manner. We also evaluated the morphological characteristics of HaCaT cells by DAPI staining. Compared to the control group, NaAsO2 treatment results in typical features of apoptosis, such as chromatin condensation and apoptotic bodies, while Pts pretreatment significantly reversed those abnormalities (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Protective effect of Pts pretreatment against NaAsO2-induced apoptosis in HaCaT cells. The HaCaT cells were exposed to 25 μM of NaAsO2 for 24 h with or without Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM) pretreatment. (A,B) The percentage of cell apoptosis was determined using flow cytometry. (C) Morphology of apoptotic cells was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy following DAPI staining at 200× magnification. Triangles: nuclear chromatin condensation in apoptotic cells. Arrows: apoptotic bodies. The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments.##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

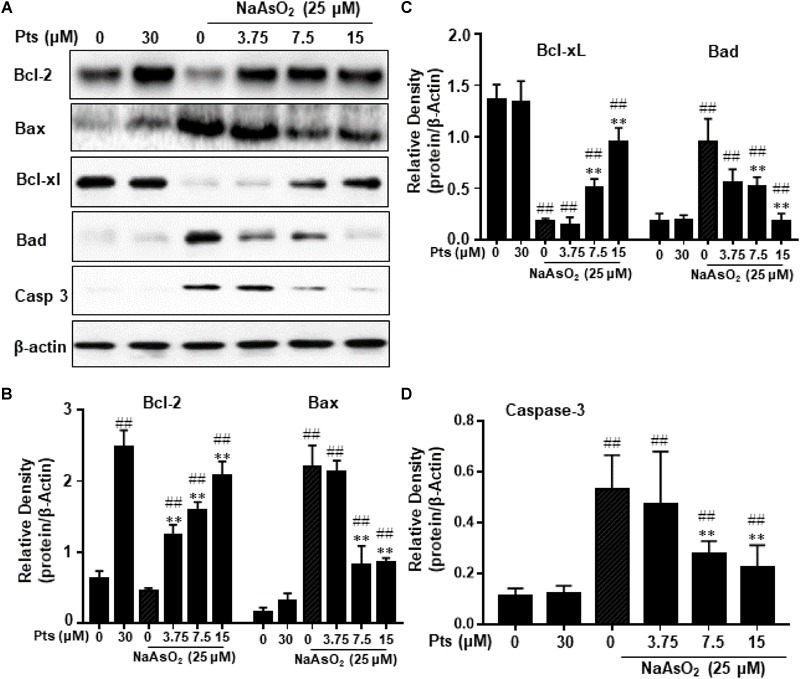

Pts Modulated the Apoptosis-Related Protein Expression in Arsenic-Treated HaCaT Cells

The Bcl-2 family of proteins, including Bcl-2, Bax, Bad, and Bcl-xl, plays an important role in apoptosis. In order to further prove the possible mechanisms of Pts in anti-apoptosis, we tested its effects on NaAsO2-induced apoptosis-related proteins. As shown in Figure 5, arsenic treatment decreased Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl protein expression and increased Bax, Bad and Caspase 3 protein expression compared with the control, but Pts pretreatment dramatically blocked these changes in a dose-dependent manner (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 5B–D).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of Pts on apoptosis-related protein expression in arsenic-treated HaCaT cells. The HaCaT cells were exposed to 25 μM of NaAsO2 for 24 h with or without Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM) pretreatment. (A) Bcl-2, Bax, Bcl-xl, Bad and Casp 3 protein levels from total cell lysates were detected by western blot analysis, and the band densities were quantified in panels (B–D). The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. ##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

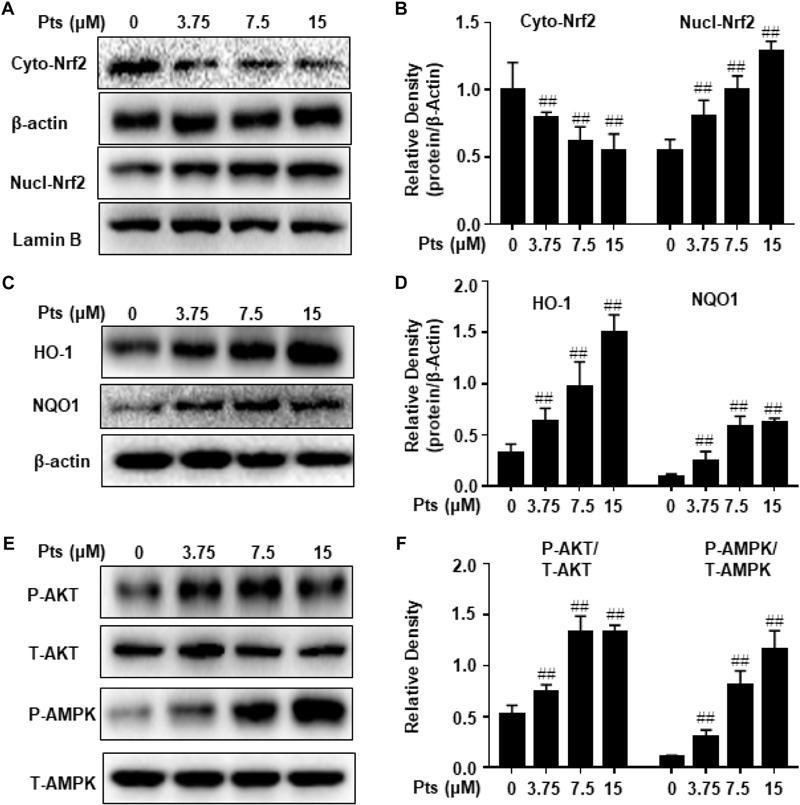

Pts Induced Nrf2 Translocation and Antioxidant Enzyme Expression in HaCaT Cells

NF-E2 p45-related factor 2 plays an imperative role in cellular redox homeostasis and actively regulates the expression of genes encoding antioxidant and phase 2 drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as HO-1, NQO-1, GCLC, and GCLM. As shown in Figure 6A,B, Pts treatment significantly increased the translocation of Nrf2 from cytoplasm to nucleus in a dose-dependent manner in HaCaT cells. Moreover, we quantified the expression of antioxidant enzymes and demonstrated that Pts upregulated HO-1 and NQO-1 expression in a dose-dependent manner (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 6C,D), but had no effect on GCLC and GCLM (data not shown). Pts has been shown to reduce acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant defense system via the AMPK/Akt/GSK3β pathway (Fan et al., 2018). Thus, we aimed to examine the effect of Pts on AMPK and AKT phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 6E,F, treatment of cells with Pts markedly increased AMPK and AKT phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of Pts on AMPK and AKT phosphorylation, Nrf2 translocation and antioxidant enzyme expression. HaCaT cells were plated in six-well culture plates and treated with Pts (3.75, 7.5, and 15 μM) for 24 h. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from cells were prepared for detecting Nrf2 in panels (A,B) and total protein extracts from cells were prepared for detecting HO-1, NQO1, AMPK and AKT in panels (C–F). The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. ##P ≤ 0.01 versus the control group.

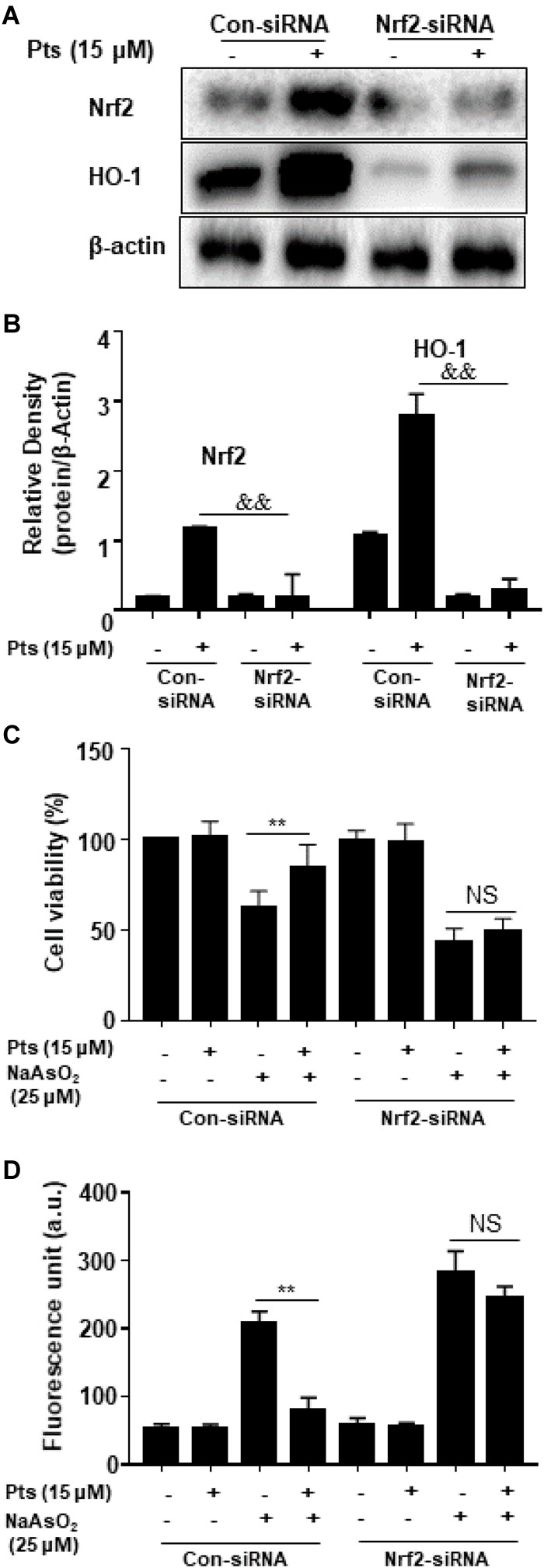

Pts-Mediated Protective Effects on NaAsO2-Induced Cytotoxicity Are Dependent on Nrf2 Activation

We proposed that the protective effect of Pts on NaAsO2 cytotoxicity of human HaCaT cells is due to the activation of Nrf2. In our study, we used Nrf2 siRNA to confirm the effect of Pts on antioxidant enzymes and NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity. HaCaT cells were transiently transfected with control or Nrf2 siRNA, and Nrf2 and HO-1 protein expression was detected by western blot analysis. Figure 7A,B demonstrate that Nrf2 siRNA can inhibit Nrf2 and HO-1 protein expression. Furthermore, our results showed that the protective effects of Pts on NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity and ROS generation were remarkably attenuated in Nrf2 siRNA transfected cells (P ≤ 0.01, as shown in Figure 7C,D).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of Nrf2-siRNA transfection on Pts-induced Nrf2 and HO-1 protein expression and protection on NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity. (A,B) Nrf2 mediates Pts-induced HO-1 protein expression. Nrf2-siRNA or Nrf2-negative control siRNA were transfected into cells for 24 h and then were treated with Pts (15 μM) for 24 h. (C) Nrf2 mediates Pts-induced protection against NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity. Cells were transfected with either control-siRNA or Nrf2-siRNA for 24 h, and then were left untreated or co-treated NaAsO2 (25 μM) with or without Pts (15 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. (D) Nrf2 mediates Pts-induced protection against NaAsO2-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT cells. Cells were transfected with either control-siRNA or Nrf2-siRNA for 24 h, and then were left untreated or co-treated NaAsO2 (25 μM) with or without Pts (15 μM) for 24 h. ROS generation was measured by the DCFH-DA method using a multi-detection reader. The results are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. ∗∗ P ≤ 0.01 versus the NaAsO2 group.

Discussion

Pterostilbene has been shown to exert a wide range of biological effects on human health, including antioxidant properties. Pts has been used for the chemoprevention and treatment of various skin diseases, such as skin tumorigenesis and wound healing (Singh et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). It has been shown that pterostilbene activates Nrf2 in human keratinocytes to protect against UVB-induced photo damage (Singh et al., 2017). Skin pigmentation and keratosis have long been considered as the most common health problems associated with exposure to arsenic contaminated drinking water (Majumdar and Guha Mazumder, 2012). In this study, our data confirm the hypothesis that pterostilbene plays a vital role in protecting against NaAsO2-induced toxicity via activating the Nrf2 pathway.

Oxidative stress is pivotal in apoptosis and cell death in arsenic toxicology, which is caused by an imbalance in reactive species, including ROS, and the intracellular antioxidant defense system in cells. Pterostilbene has been reported to inhibit ROS production and prevent continued oxidative stress (He et al., 2018). Our results here suggested that arsenic-induced cytotoxicity were significantly reversed by Pts treatment. Moreover, Pts treatment significantly suppressed oxidative stress markers, such as the depletion of the antioxidant enzyme SOD and augmented ROS and MDA levels, which were caused by NaAsO2. In addition, mitochondria is essential for the normal maintenance of the physiological function of MMP, but the accumulation of ROS leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, which promotes the release of cytochrome c and cell apoptosis (Lv et al., 2017b). Our data suggested that Pts can reverse NaAsO2-induced MMP collapse and mitochondrial cytochrome c translocation, hence suggesting that Pts can attenuate NaAsO2-induced mitochondrial damage and prevent further apoptosis in HaCaT cells.

Apoptosis can be initiated by stressful conditions, resulting in serious health problems and fatality. Various models show that arsenic is a strong inducer of apoptosis by overgenerating ROS, decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential, and increasing the DNA fragmentation in immune cells (Xu et al., 2015). In the present study, we found that NaAsO2 caused excessive ROS production and eventually promoted apoptosis in HaCaT cells. Pts pretreatment ameliorated NaAsO2-induced apoptosis by decreasing the number of apoptotic cells and restoring the apoptotic morphological markers of chromatin condensation, nucleolus pyknosis, and apoptotic bodies in HaCaT cells. The Bcl-2 family of proteins includes the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 subfamily, and the pro-apoptotic Bax subfamily and the Bik family, and the Bax/Bcl2 ratio plays a key role in cell death and survival. Previous findings indicate that Pts significantly decreases the incidence of apoptosis and the Bax/Bcl2 ratio during skeletal muscle IR injury (Cheng et al., 2016). Our current results showed that NaAsO2 exposure induced the downregulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl protein and the upregulation of Bax, Bad and Caspase 3 proteins, which could be reversed by Pts treatment. Taken together, our results suggest that not only the regulation of mitochondrial dysfunction, but also the inhibition of the apoptotic process may be involved in the cytoprotective effects of the antioxidant Pts.

NF-E2 p45-related factor 2, which directly regulates many antioxidant and detoxification enzyme genes, plays a vital role in cellular redox homeostasis and antioxidant response. Previous studies have shown that the steady depletion of Nrf2 by shRNA makes human HaCaT cells more sensitive to iAs3+ induced cell death, suggesting that Nrf2 activators may be used in therapeutic and dietary interventions against the side effects of arsenic (Zhao et al., 2012). Pts, as an effective inducer of Nrf2, has been shown to reduce acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant defense system via the AMPK/Akt/GSK3β pathway (Fan et al., 2018). In this study, Pts was shown to induce AMPK and AKT phosphorylation, translocation of Nrf2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, upregulating Nrf2 downstream expression of NQO1 and HO-1 expression. These investigations indicated that Pts possesses antioxidant activity and further protected against NaAsO2-induced toxicity in HaCaT cells, and that these effects are attenuated in Nrf2-knockdown cells, suggesting that the upregulation of Nrf2-mediated expression of antioxidant genes induced by Pts protects against NaAsO2-induced toxicity.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the protective effects of Pts against NaAsO2-induced cytotoxicity by regulating oxidative stress markers and mitochondrial dysfunction in HaCaT cells. Pts treatment provided protection from apoptosis by increasing Bcl-2 and decreasing Bax protein expression. In addition, Pts could also induce a Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response, which is likely connected to the observed increased cell survival. Our data therefore suggest that Pts, a Nrf2 inducer, represents a novel therapeutic and dietary candidate in the treatment of arsenic-induced skin hyperkeratosis and carcinogenesis. The protective effects of Pts on arsenic-induced skin damage should be further studied in animal models.

Author Contributions

JZ wrote the manuscript and performed the experiments. XC, XM, QY, YC, and YZ performed some experiments, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. SL contributed to design the experiments and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by Science and Technology Projects of Chaoyang District of Changchun (201613).

References

- Chen J., Liu W., Yi H., Hu X., Peng L., Yang F. (2018). The natural rotenoid deguelin ameliorates diabetic neuropathy by decreasing oxidative stress and plasma glucose levels in rats via the Nrf2 signalling pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 48 1164–1176. 10.1159/000491983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Di S., Fan C., Cai L., Gao C., Jiang P., et al. (2016). SIRT1 activation by pterostilbene attenuates the skeletal muscle oxidative stress injury and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by ischemia reperfusion injury. Apoptosis 21 905–916. 10.1007/s10495-016-1258-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X., Li J., Li W., Xing X., Zhang Y., Li W. (2016). Antioxidant tert-butylhydroquinone ameliorates arsenic-induced intracellular damages and apoptosis through induction of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses as well as stabilization of anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 in human keratinocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 94 74–87. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrela J. M., Ortega A., Mena S., Rodriguez M. L., Asensi M. (2013). Pterostilbene: biomedical applications. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 50 65–78. 10.3109/10408363.2013.805182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Wang L., Huang J., Lv H., Deng X., Ci X. (2018). Pterostilbene reduces acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating the Nrf2 antioxidative defense system via the AMPK/Akt/GSK3beta pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 4 1943–1958. 10.1159/000493655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Woods C. G., Yehuda-Shnaidman E., Zhang Q., Wong V., Collins S., et al. (2010). Low-level arsenic impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells: involvement of cellular adaptive response to oxidative stress. Environ. Health Perspect. 118 864–870. 10.1289/ehp.0901608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F. (2008). Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 568–578. 10.1038/nrn2421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Ivanov V. N., Davidson M. M., Hei T. K. (2015). Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) protects against sodium arsenite-induced nephrotoxicity by suppressing ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction, pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and programed cell death. Arch. Toxicol. 89 1057–1070. 10.1007/s00204-014-1302-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R., Mazumder D. N., Samanta S., Ghosh N., Kalman D., Smith M. M., et al. (2003). Arsenic in drinking water and skin lesions: dose-response data from West Bengal, India. Epidemiology 14 174–182. 10.1097/01.ede.0000040361.55051.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. L., Dong X. H., Li Z. H., Wang X. Y., Fu Z. A., Shen N. (2018). Pterostilbene inhibits reactive oxygen species production and apoptosis in primary spinal cord neurons by activating autophagy via the mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 17 4406–4414. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. F., Beck B. D., Chen Y., Lewis A. S., Thomas D. J. (2011). Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol. Sci. 123 305–332. 10.1093/toxsci/kfr184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Chen C., Zhao W., Zhang Z. (2013). Sodium arsenite and arsenic trioxide differently affect the oxidative stress, genotoxicity and apoptosis in A549 cells: an implication for the paradoxical mechanism. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 36 891–902. 10.1016/j.etap.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn F. E., Carter G. T. (2005a). Rediscovering natural products as a source of new drugs. Discov. Med. 5 159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn F. E., Carter G. T. (2005b). The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4 206–220. 10.1038/nrd1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Kim I. S., More S. V., Kim B. W., Choi D. K. (2014). Natural product-derived pharmacological modulators of Nrf2/ARE pathway for chronic diseases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31 109–139. 10.1039/c3np70065h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Yu H. S. (2016). Role of mitochondria, ROS, and DNA damage in arsenic induced carcinogenesis. Front. Biosci. 8:312–320. 10.2741/s465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Liu Q., Zhou J., Tan G., Deng X., Ci X. (2017b). Daphnetin-mediated Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathways ameliorate tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP)-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 106 38–52. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Liu Q., Wen Z., Feng H., Deng X., Ci X. (2017a). Xanthohumol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury via induction of AMPK/GSK3beta-Nrf2 signal axis. Redox Biol. 12 311–324. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Xiao Q., Zhou J., Feng H., Liu G., Ci X. (2018). Licochalcone A upregulates Nrf2 antioxidant pathway and thereby alleviates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 9:147. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahieux R., Pise-Masison C., Gessain A., Brady J. N., Olivier R., Perret E., et al. (2001). Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1- and type 2-infected cells by a caspase-3-dependent mechanism involving Bcl-2 cleavage. Blood 98 3762–3769. 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar K. K., Guha Mazumder D. N. (2012). Effect of drinking arsenic-contaminated water in children. Indian J. Public Health 56 223–226. 10.4103/0019-557X.104250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V. D., Vucic E. A., Becker-Santos D. D., Gil L., Lam W. L. (2011). Arsenic exposure and the induction of human cancers. J. Toxicol. 2011:431287. 10.1155/2011/431287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Rimando A. M., Lee H. J., Ji Y., Reddy B. S., Suh N. (2009). Anti-inflammatory action of pterostilbene is mediated through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in colon cancer cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2 650–657. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Arora D., Shukla Y. (2017). Enhanced chemoprevention by the combined treatment of pterostilbene and lupeol in B[a]P-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 99 182–189. 10.1016/j.fct.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirerol J. A., Feddi F., Mena S., Rodriguez M. L., Sirera P., Aupí M., et al. (2015). Topical treatment with pterostilbene, a natural phytoalexin, effectively protects hairless mice against UVB radiation-induced skin damage and carcinogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 85 1–11. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. J., Sun Z., Chen W., Eblin K. E., Gandolfi J. A., Zhang D. D. (2007). Nrf2 protects human bladder urothelial cells from arsenite and monomethylarsonous acid toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 225 206–213. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. X., Liu S. Z., Wu D., Qiao G. F., Yan J. (2015). Sumoylation of the tumor suppressor promyelocytic leukemia protein regulates arsenic trioxide-induced collagen synthesis in osteoblasts. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 37 1581–1591. 10.1159/000438525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. C., Tseng C. H., Wang P. W., Lu L. U., Weng Y. H., Yen F. L., et al. (2017). Pterostilbene, a methoxylated resveratrol derivative, efficiently eradicates planktonic, biofilm, and intracellular MRSA by topical application. Front. Microbiol. 8:1103. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Wang S., Zhang X., Li Y., Zhao Q., Liu T. (2017). Pterostilbene protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via suppressing oxidative/nitrative stress and inflammatory response. Int. Immunopharmacol. 43 7–15. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Gao L., Cheng Y., Jiang J., Chen Y., Jiang H., et al. (2014). Resveratrol, a natural antioxidant, has a protective effect on liver injury induced by inorganic arsenic exposure. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:617202. 10.1155/2014/617202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R., Hou Y., Zhang Q., Woods C. G., Xue P., Fu J., et al. (2012). Cross-regulations among NRFs and KEAP1 and effects of their silencing on arsenic-induced antioxidant response and cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes. Environ. Health Perspect. 120 583–589. 10.1289/ehp.1104580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R., Yang B., Wang L., Xue P., Deng B., Zhang G., et al. (2013). Curcumin protects human keratinocytes against inorganic arsenite-induced acute cytotoxicity through an NRF2-dependent mechanism. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:412576. 10.1155/2013/412576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]