Abstract

Background

Disablement occurs when people lose their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) like bathing and dressing, and is measured as the rate of increasing disability over time. We examined whether balance impairment, cognitive impairment, or pain among residents at admission to long-term care homes were predictive of their rate of disablement over the subsequent 2 years.

Methods

Linked administrative databases were used to conduct a longitudinal cohort study of 12,334 residents admitted to 633 long-term care (LTC) homes between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012, in Ontario, Canada. Residents received an admission assessment of disability upon admission to LTC using the RAI-MDS 2.0 ADL long-form score (ADL LFS, range 0–28) and at least two subsequent disability assessments. Multivariable regression models estimated the adjusted association between balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain present at admission and residents’ subsequent disablement over 2 years.

Results

This population sample of newly admitted Ontario long-term care residents had a median disability score of 13 (interquartile range [IQR] = 7, 19) at admission. Greater balance impairment and cognitive impairment at admission were significantly associated with faster resident disablement over 2 years in adjusted models, while daily pain was not.

Conclusions

Balance impairment and cognitive impairment among newly admitted long-term care home residents are associated with increased rate of disablement over the following 2 years. Further research should examine the mechanisms driving this association and identify whether they are amenable to intervention.

Keywords: Activities of daily living, Disability, Geriatric syndrome, Nursing homes

At the time of admission to a long-term care home (LTCH, or nursing home), most residents need help with activities of daily living (ADLs) (1) and become more dependent on others for ADLs over time (2). Disability refers to residents needing help with ADLs measured at one point in time, while disablement refers to increasing disability over time (3). A recent cross-sectional study found that geriatric syndromes such as balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain, accounted for half of the between-resident differences in disability in a population sample (4). We hypothesized that in addition to these cross-sectional associations, balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain present at admission to an LTCH would increase residents’ rate of disablement over time. Past studies of these geriatric syndromes’ association with disablement were conducted either in select subpopulations of LTCH residents (5,6) or did not account for the effect of baseline disability (5,7,8). It is therefore unclear whether balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain are simply acting as proxy measures for baseline disability, and whether their association with disability and disablement is due to selection bias in restricted samples.

This study examines the independent associations of pain, balance, and cognitive impairment at admission and LTCH residents’ subsequent disablement over 2 years in a population sample. Plausible mechanisms—such as medication side effects (9), activity restriction (10) or fear of falling (11) —may link these geriatric syndromes with disablement and are amenable to intervention. Knowing whether residents with these common geriatric syndromes present at admission experience more rapid subsequent disablement during their long-term care stay is important to guide future interventions that prevent or slow disablement in LTCH residents.

Method

Study Cohort

We conducted a population-based longitudinal cohort study to determine the association between balance impairment, moderate severe to severe cognitive impairment, and daily pain (henceforth: balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain) at admission to long-term care with disablement over 2 years. We enrolled all LTCH residents in Ontario, Canada, who were newly admitted to an LTCH and received a Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Dataset 2.0 (RAI-MDS) admission assessment between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012. We then applied several exclusions (Supplementary Figure S1), such that residents included in the study sample had at least two subsequent RAI-MDS assessments in the LTCH that they were admitted to and had admission disability scores below the maximum score of 28. These exclusions allowed for longitudinal tracking of disablement among residents following their admission.

Data Sources

Data for this study were drawn from health administrative databases containing information on all hospital admissions, physician visits, and LTC resident functional assessments. Because Ontario finances and regulates all licensed LTCH care, the data represent a complete population cohort of LTCH residents. Data were linked at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) using unique, anonymized identifiers. Data included the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) to determine chronic conditions coded during hospital admissions, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) physician billings to determine diagnoses in physician claims, the Registered Persons Database (RPDB) for resident age and sex, and the CIHI Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS) for baseline demographic characteristics and geriatric syndrome diagnoses as well as repeated resident disability measures obtained from RAI-MDS assessments (12). The RAI-MDS is a standardized, multidimensional assessment tool used in LTCHs across Canada, the United States, and internationally (13). Trained LTCH staff complete the assessments when residents are admitted to LTCH, every 90 days thereafter, and when there are any significant changes in resident health status (14). National and international evaluations have demonstrated that the RAI-MDS scales used to identify geriatric syndromes in this study are reliable (13) and valid (12). This study received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Office of Research Ethics and the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Research Ethics Board. Results are reported in accordance with the RECORD extension of the STROBE criteria for observational studies conducted in health administrative data (15).

Outcome

The primary outcome was the repeated measure of disability from RAI-MDS assessments. Resident disability was measured using the Activities of Daily Living Long-Form Score (ADL LFS) on a scale from 0 to 28 based on degree of dependence on others for bed mobility, transfer, locomotion, dressing, eating, toilet use, and personal hygiene. A one-point increase in ADL LFS indicates increased dependence in an ADL or dependence in a new ADL, both of which are associated with intensified care needs from LTCH staff (5). The ADL LFS has been validated against standardized measures of disability (16,17), is reliable and internally consistent (18,19), and responsive to changes in disability over time (5). Time was measured in months since the date of residents’ admission assessment.

Disablement was measured using the ADL LFS treated as a continuous linear variable, as in previous research (4,20,21). Figure S2 shows the distribution of disability scores in sample residents at admission. Among individuals who died during the 2-year observation period, a final disability measure of 28 was imputed on the date of their death. This analytic treatment of missing data due to censoring has precedent in other longitudinal studies of disablement (22,23) and aligns with extant knowledge on the rapid disablement individuals experience in the month prior to death (24).

Geriatric Syndrome Exposures

Residents were classified as having balance impairment if during an admission test of balance from standing, they required partial physical support or were unable to balance from standing. This RAI-MDS balance assessment has been used to study balance impairment in older nursing home populations from several countries (7,21,25). Moderately severe to severe cognitive impairment was defined as RAI-MDS cognitive performance score of 4, 5, or 6, which is equivalent to a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of seven or less (26). Residents who reported daily or severe daily pain were classified as having pain at admission (27).

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics, 16 coexisting chronic conditions that had been treated or affected medical management in the 5 years prior to admission, and six additional geriatric syndromes (bowel incontinence, urinary incontinence, hearing impairment, visual impairment underweight BMI, and pressure ulcer) prevalent at admission were included as covariates in multivariable models (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Statistical Analyses

The unit of analysis was the individual resident. Nested hierarchical linear regression models were used to assess the relationship between disablement and the geriatric syndrome exposures, controlling for baseline disability, sociodemographic characteristics, time in months since admission, chronic conditions, and the additional geriatric syndromes. The effects of the geriatric syndrome exposures on disablement were estimated through interactions between these geriatric syndromes and time, controlling for the interaction between baseline disability and time (Supplementary Appendix Equation 1). The latter interaction was included to enable assessment of the incremental effect of geriatric syndrome exposures beyond the effect of disability on disablement. The models accounted for nesting of time within residents and residents within LTCHs by including random effects for LTCH and resident (Supplementary Table S3). The assumptions of normally distributed random effects and residual errors were confirmed, and a quadratic term for time was tested. Regression modeling was performed using STATA xtmixed (28).

Sensitivity Analyses

The prevalence of the geriatric syndrome exposures among those who subsequently died were examined, as were characteristics of residents excluded because they had fewer than two postadmission RAI-MDS assessments. We also examined the impact of imputation of a final disability score of 28 among those who died as well as rerunning the analysis, excluding residents who died during follow-up.

Results

Resident Characteristics

A total of 12,334 residents from 633 Ontario LTCHs were included in the study (Table 1). The mean disability score at admission was 13.0 (SD: 7.2); mean age was 84.1 years (SD: 7.2) and 67.7% were female. Residents had a median of nine assessments (interquartile range [IQR]: 7, 9) in the observation period, including their admission assessment. The median number of days between assessments was 90.5 (IQR: 85.0, 91.0).

Table 1.

Ontario LTCH Resident Characteristics at Admission to Long-Term Care

| N | % | Mean ADL LFS (SD) at Admission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Cohort | 12,334 | 100 | 13.0 (7.2) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–74 | 1,321 | 10.7 | 12.9 (7.5) |

| 75–84 | 4,580 | 37.1 | 12.7 (7.2) |

| 85–94 | 5,697 | 46.2 | 13.0 (7.2) |

| 95+ | 736 | 6.0 | 14.3 (7.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 8,348 | 67.7 | 12.9 (7.2) |

| Male | 3,986 | 32.3 | 13.0 (7.3) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 3,713 | 30.1 | 13.5 (7.3) |

| Widowed | 6,870 | 55.7 | 12.7 (7.2) |

| Never married/Separated/Divorced | 1,518 | 12.3 | 12.5 (7.3) |

| Missing | 233 | 1.9 | 13.3 (7.2) |

| Pre-NH Neighborhood Income Quintile | |||

| 1 (low) | 2,830 | 22.9 | 12.4 (7.3) |

| 2 | 2,306 | 18.7 | 13.2 (7.2) |

| 3 | 2,039 | 16.5 | 13.1 (7.2) |

| 4 | 1,786 | 14.5 | 13.1 (7.2) |

| 5 (high) | 1,551 | 12.6 | 13.3 (7.1) |

| Missing | 1,822 | 14.8 | 13.0 (7.4) |

| Geriatric Syndrome Exposures | |||

| Balance impairment | 7,790 | 63.2 | 15.6 (6.7) |

| Cognition | |||

| Intact or borderline | 3,309 | 26.8 | 11.3 (7.6) |

| Moderate impairment | 7,246 | 58.8 | 12.6 (6.8) |

| Moderate-severe/very severe impairment | 1,779 | 14.4 | 17.5 (6.3) |

| Pain | |||

| No pain | 7,169 | 58.1 | 12.4 (7.2) |

| Less than daily pain | 3,095 | 25.1 | 13.5 (7.0) |

| Daily or severe daily pain | 2,070 | 16.8 | 14.1 (7.3) |

| Other Geriatric Syndromes | |||

| Bowel incontinence | 3,746 | 30.4 | 18.3 (5.6) |

| Hearing impaired | 1,762 | 14.3 | 13.9 (6.9) |

| BMI | |||

| BMI < 18.5 | 1,251 | 10.1 | 14.8 (7.2) |

| 18.5 ≤ BMI ≤ 25 | 5,583 | 45.3 | 13.0 (7.2) |

| 25 < BMI <30 | 3,355 | 27.2 | 12.2 (7.2) |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 2,145 | 17.4 | 13.0 (7.2) |

| Pressure ulcer | 662 | 5.4 | 18.8 (5.7) |

| Urinary incontinence | 6,878 | 55.8 | 16.0 (6.2) |

| Visual impairment | |||

| Moderate impairment | 4,131 | 33.5 | 13.9 (7.0) |

| Severe impairment | 588 | 4.8 | 16.6 (7.1) |

| Chronic Conditions | |||

| Arthritis | 5,897 | 47.8 | 13.4 (7.2) |

| Asthma | 688 | 5.6 | 13.4 (7.1) |

| Cancer | 4,305 | 34.9 | 12.9 (7.3) |

| Kidney disease | 2,479 | 20.1 | 14.2 (7.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 4,303 | 34.9 | 13.2 (7.3) |

| COPD | 1,974 | 16.0 | 12.9 (7.3) |

| Dementia | 8,572 | 69.5 | 13.1 (7.2) |

| Diabetes | 3,664 | 29.7 | 13.4 (7.2) |

| Epilepsy | 426 | 3.5 | 14.3 (7.2) |

| Heart failure | 2,703 | 21.9 | 13.9 (7.2) |

| Limb paralysis or amputation | 1,802 | 14.6 | 12.9 (7.0) |

| Mood disorders | 1,941 | 15.7 | 13.1 (7.4) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 896 | 7.3 | 16.0 (6.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 440 | 3.6 | 13.3 (7.0) |

| Psychiatric conditions other than depression and dementia | 2,661 | 21.6 | 13.4 (7.2) |

| Stroke | 2,517 | 20.4 | 15.2 (7.1) |

Note: ADL = Activities of daily living; BMI = Body mass index; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LFS = Long form score; LTCH = Long-term care home; NH = Nursing home.

A total of 4,213 (34%) residents died during follow-up; the geriatric syndromes exposures were more prevalent among decedents (Supplementary Table S4). Similarly, residents excluded because they had fewer than two postadmission assessments also had higher prevalence of geriatric syndrome exposures (Supplementary Table S4), higher baseline disability and increased prevalence of most chronic conditions (Supplementary Table S5).

Main Results

Table 2 reports the association of disablement with balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain present at admission, the geriatric syndrome exposures, adjusted for baseline disability, demographic characteristics, chronic conditions, and other geriatric syndromes. Higher ADL LFS equates to more disability; thus, positive regression coefficients indicate a higher rate of disablement over time. Balance impairment (0.42, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.56) and cognitive impairment (0.85, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.03) were both associated with slightly higher disability, whereas daily pain was not. Balance impairment at admission was associated with an average 0.04 (95% CI: 0.02, 0.06) monthly increase in residents’ ADL LFS over 2 years; cognitive impairment also increased rate of disablement by 0.08 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.10) per month. Daily pain present at admission was conversely associated with a small decrease in residents’ rate of disablement (−0.03, 95% CI: −0.05, −0.01) over 2 years. Full model estimates, including coefficients for adjustment variables, are available in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 2.

Adjusted Associations of Disablement Over 2 y with Resident Geriatric Syndromes Present at Admission in Ontario LTCH Residents

| Covariate | Regression Coefficient in Multivariable Model |

|---|---|

| Est (95% CI) | |

| Constant | 0.27 (−0.05, 0.59) |

| Time (months since admission) | 0.56 (0.54, 0.58)‡ |

| Baseline Disability (ADL LFS) | 0.86 (0.85, 0.87)‡ |

| Baseline Disability × Time | −0.02 (−0.02, −0.02)‡ |

| Baseline Geriatric Syndromes | |

| Balance impairment | 0.42 (0.28, 0.56)‡ |

| Cognition | |

| Intact or borderline | Reference |

| Moderate impairment | 0.26 (0.11, 0.40)‡ |

| Moderate-severe/very severe impairment | 0.85 (0.66, 1.03)‡ |

| Pain | |

| None | Reference |

| Less than daily pain | −0.17 (−0.30, −0.04)* |

| Daily or severe daily pain | −0.05 (−0.20, 0.10) |

| Geriatric Syndromes’ Association with Disablement Over 2 y | |

| Balance impairment × Time | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06)‡ |

| Moderately-severe to severe cognitive impairment × Time | 0.08 (0.06, 0.10)‡ |

| Daily or severe daily pain × Time | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01)† |

Note: All model estimates are adjusted for resident age, sex, marital status, preadmission neighborhood income quintile, and the six additional geriatric syndromes and 16 chronic conditions indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

ADL = Activities of daily living; CI = Confidence interval; LFS = Long form score; LTCH = Long-term care home.

Statistical significance of each coefficient is indicated as follows: *p-value <.05; †p-value <.01; ‡p-value <.0001.

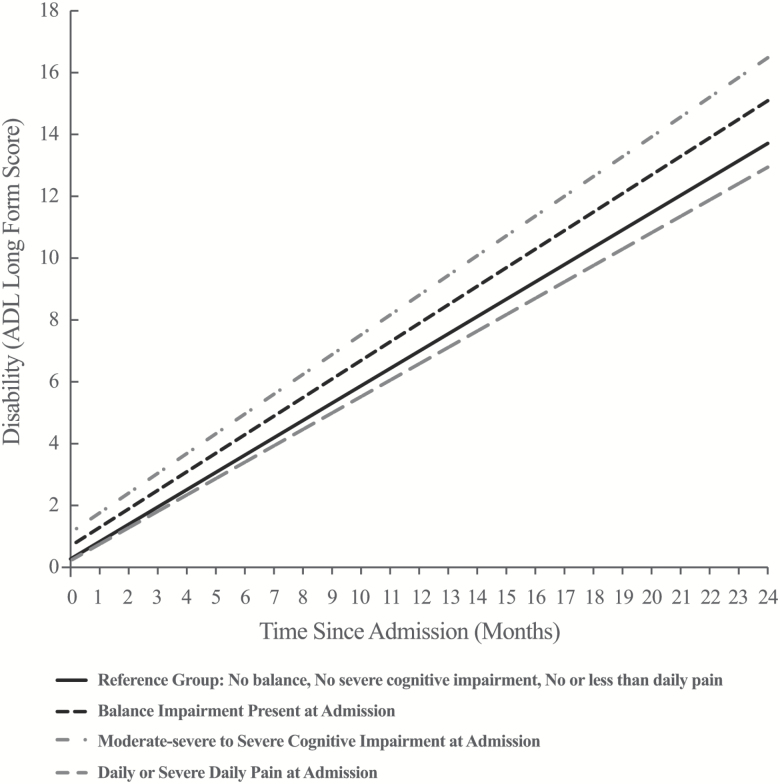

Figure 1 is based on the estimates in Table 2, and illustrates differences in admission disability and disablement over 2 years in Ontario LTCH residents. The reference rate of disablement (+0.56 ADL LFS points/month, 95% CI: 0.54, 0.58) was estimated as the mean monthly rate (slope) of increasing disability in residents with no balance impairment, cognitive impairment or pain at admission, adjusted for all other model covariates. The association of balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain with disablement were interpreted as the incremental effects of each exposure on the reference rate of disablement. In addition to their association with higher disability, both balance impairment and cognitive impairment were associated with significantly increased rates of disablement over 2 years. Adjusting for all variables, residents who were admitted to an LTCH with balance impairment had ADL LFS scores an average of 1.38 points higher 2 years later than ones with no balance impairment at admission. Similarly, residents admitted with moderate severe to severe cognitive impairment had average ADL LFS scores 2.77 points higher 2 years later than those with moderate, mild or no cognitive impairment at admission. In contrast, residents admitted to LTCH with daily pain experienced slightly slower rates of disablement than residents with no pain or nondaily pain at admission and had an average ADL LFS score 0.77 points lower 2 years postadmission.

Figure 1.

Adjusted differences in admission disability and rate of disablement in LTCH residents with cognitive impairment, balance impairment, and pain at admission. Note: Increasing disability (ADL Long-Form Score) is undesirable; an upward sloping line indicate residents are becoming more disabled over time. ADL = Activities of daily living; LTCH = Long-term care home.

Sensitivity Analyses

One sensitivity analysis included all residents who died during the study period but did not impute a final ADL LFS score of 28 on the date of their death. A second excluded all residents who died during follow-up. Both resulted in reduced estimates for the rates of disablement over 2 years. The effects of cognitive impairment and pain on disablement were unchanged in both sensitivity models. The impact of balance impairment on disablement was rendered nonsignificant in the sensitivity model that excluded residents who died during follow-up.

Discussion

A population-based sample of 12,334 newly admitted Ontario LTCH residents experienced disablement over the course of 2 years. Balance impairment and cognitive impairment were associated with higher baseline disability and increased rate of disablement over 2 years in adjusted models, whereas pain was not. We found balance impairment and cognitive impairment present at residents’ admission to long-term care were associated with increased rate of disablement over 2 years, independent of baseline disability, sociodemographic characteristics, six prevalent geriatric syndromes (bowel incontinence, urinary incontinence, hearing impairment, visual impairment underweight BMI, and pressure ulcer) and 16 prevalent chronic conditions. These findings from a population sample enhance our understanding of the independent role balance impairment and cognitive impairment may play in increasing LTCH residents’ disablement over time.

We hypothesized that balance impairment, cognitive impairment, and pain present at admission to a LTCH would increase disablement in residents, independent of their baseline ADL disability. We posited that this may occur through a variety of mechanisms, such as activity restriction due to balance impairment and fear of falling (10,11), discomfort with movement due to pain (29), lack of comprehension or motivation to maintain activity (30,31), or medication side effects (9) associated with cognitive impairment. We did not test these mechanisms directly.

Given the breadth of covariates adjusted for in the multivariable analysis, it is unsurprising that balance and cognitive impairment were associated with relatively modest increases in the rate of residents’ disablement. Furthermore, although our study only accounted for these geriatric syndrome exposures at admission to LTCH, differences in residents’ rate of disablement persisted over the subsequent 2 years. Even small differences in the rate of disablement are meaningful given this timespan. Having daily pain at admission to LTCH was not associated with resident disability and was associated with slightly slower rate of disablement in adjusted models. One possible explanation for this is that unlike balance or cognitive impairment, pain can be readily treated pharmacologically and some of the pain may result from increased activity levels. LTCH staff may also act as proxies for residents in the reporting of pain in the RAI-MDS, leading in inaccurate measurement, especially among cognitively impaired residents (27). This could have caused misclassification of pain status among residents in our study that masked an association between pain at admission and disablement over time.

Our finding that balance impairment and cognitive impairment were associated with higher disability at LTCH admission aligns with evidence of this relationship from cross-sectional research (4), but few studies have examined these relationships longitudinally. In Carpenter et al.’s study of LTCH residents with dementia and few comorbidities, those with moderate cognitive impairment became disabled at a rate of 0.30 ADL LFS points per month, compared to a similar rate of 0.28 among residents with severe cognitive impairment (5). Conversely, Kruse et al. found that each 1-point increase in a 7-point cognitive impairment scale was associated with a 0.08 point worsening in disability measured with ADL LFS per month (6). Our study expands on these findings by demonstrating in an inclusive sample that an association between cognitive impairment and faster disablement is generalizable to newly admitted LTCH residents, not just those recently discharged from hospital (6).

The median 2-year follow-up period in this study also affords an important long-term view of associations between balance and cognitive impairment and pain with disablement in LTCH residents. For example, Burge et al. found that both balance and cognitive impairment were associated with increased hazard of a dichotomous ADL “decline” outcome in 10,199 nursing home residents (7); Wang et al. found that balance dysfunction was independently associated with loss of independence in personal hygiene and toileting in 4,942 Minnesota nursing home residents, whereas pain was not associated with disablement in any ADLs (21).

But because these studies examined predictors of disablement over 8–12 months, the longer-term impact of being admitted with one of these geriatric syndrome exposures could not be determined. In our study, the median frequency and intervals between RAI-MDS assessments indicate that the vast majority of those who survived were followed for the full 2 years. LTCH residents’ length of stay varies across countries and sociodemographic characteristics (32,33); in the United States, the mean length of stay is 1.1 years (33), compared to 2 to 3 years in Canada, England, and Switzerland (32,34,35). Findings from the present study are more generalizable that past research for care planning among newly admitted LTCH residents in populations where the majority of LTCH residents live 2 years or more after admission.

A major strength of our study was the use of data from a representative population cohort of newly admitted LTCH residents in a single-payer health system. Second, we tracked changes in a validated measure of disability over multiple time points using robust statistical models. Third, we also used validated administrative claims data to adjust for the effects of comorbidities. Fourth, unlike other studies of these relationships, ours tracked residents after their admission and did not exclude anyone based on comorbidities.

Our study was subject to some limitations. First, our requirement that residents have at least two subsequent assessments after admission may have caused selection bias. However, we provided information on the characteristics of these excluded subjects so that the likely effects of their exclusion could be assessed. Second, 34% of the sample died during the follow-up period, but sensitivity analyses revealed a minimal impact of this on findings, other than balance impairment which was not associated with disablement in the healthier subset of residents in a complete case analysis.

A third limitation is that the ADL LFS measure may be relatively insensitive to changes in disability as residents approach the higher range of the scale (36). In our study, this would lead to potential underestimation of disablement, rendering our findings conservative estimates of potentially larger true relationships. Fourth, the psychometric properties of the RAI-MDS balance assessment have not been formally assessed, however it has high face validity and has been widely used in studies of balance impairment in LTC populations (7,21,25). Fifth, the Ontario Ministry of Health reimburses LTCHs more to care for residents who are more disabled; this potentially incentivizes operators to code residents as having higher levels of disability over time; however, this equally affects residents with and without the geriatric syndrome exposures in this study.

Future research needs to examine the mechanisms linking cognitive and balance impairment at admission with LTCH residents’ rate of disablement over the subsequent 2 years. Studies can examine the allocation of resources among persons with these and other geriatric syndromes to identify which are most responsible for ameliorating the effect of geriatric syndromes on subsequent disablement, as well as intervening events (ie, hospitalizations) that worsen the trajectory of disablement. Studies of interventions to improve balance or cognitive function in LTCH residents could also enhance the evidence base by measuring rate of disablement as an outcome.

Balance impairment and cognitive impairment among newly admitted LTCH residents are associated with increased rate of disablement over the following 2 years. Future research must elucidate the mechanisms driving these potentially causal associations so that appropriate action can be taken to slow disablement in LTCH residents.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC) to the Health System Performance Research Network (Grant # 06034), as well as the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the MOHLTC. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. Natasha Lane was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship and a Foundation grant (FDN 143303) postgraduate fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. C.M.B. was supported by the Paul Beeson Career Development Award (NIH K23 AG032910), The John A. Hartford Foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, and the Starr Foundation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ms. Alice Newman at ICES for her meticulous work creating the dataset for this study, as well as Dr Paul Stolee for his thoughtful feedback on this study.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- 1. Canadian Institute of Health Information: When a Nursing Home is Home: How do Canadian Nursing Homes Measure up on Quality. Toronto, ON: Canadian Institute of Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dutcher SK, Rattinger GB, Langenberg P, et al. Effect of medications on physical function and cognition in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1046–1055. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lane NE, Wodchis WP, Boyd CM, Stukel TA. Disability in long-term care residents explained by prevalent geriatric syndromes, not long-term care home characteristics: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:49. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0444-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carpenter GI, Hastie CL, Morris JN, Fries BE, Ankri J. Measuring change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kruse RL, Petroski GF, Mehr DR, Banaszak-Holl J, Intrator O. Activity of daily living trajectories surrounding acute hospitalization of long-stay nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1909–1918. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bürge E, von Gunten A, Berchtold A. Factors favoring a degradation or an improvement in activities of daily living (ADL) performance among nursing home (NH) residents: a survival analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fedecostante M, Dell’Aquila G, Eusebi P, et al. Predictors of functional changes in Italian nursing home residents: the U.L.I.S.S.E. Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmac. 2012;10:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304:1919–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Talley KM, Wyman JF, Gross CR, Lindquist RA, Gaugler JE. Change in balance confidence and its associations with increasing disability in older community-dwelling women at risk for falling. J Aging Health. 2014;26:616–636. doi: 10.1177/0898264314526619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirdes JP, Poss JW, Caldarelli H, et al. An evaluation of data quality in Canada’s continuing care reporting system (CCRS): secondary analyses of Ontario data submitted between 1996 and 2011. BMC Med Inform Decis. 2013;13:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, et al. Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: a 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:277. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirdes JP, Mitchell L, Maxwell CJ, White N. Beyond the ‘iron lungs of gerontology’: using evidence to shape the future of nursing homes in Canada. Can J Aging. 2011;30:371–390. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frederiksen K, Tariot P, De Jonghe E. Minimum Data Set Plus (MDS+) scores compared with scores from five rating scales. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00920.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawton MP, Casten R, Parmelee PA, Van Haitsma K, Corn J, Kleban MH. Psychometric characteristics of the minimum data set II: validity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:736–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M546–M553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.M546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Mor V, Fries BE, Nonemaker S. Reliability estimates for the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist. 1995;35:172–178. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.2.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang J, Chang LH, Eberly LE, Virnig BA, Kane RL. Cognition moderates the relationship between facility characteristics, personal impairments, and nursing home residents’ activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2275–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang J, Kane RL, Eberly LE, Virnig BA, Chang LH. The effects of resident and nursing home characteristics on activities of daily living. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:473–480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spiers NA, Matthews RJ, Jagger C, et al. Diseases and impairments as risk factors for onset of disability in the older population in England and Wales: findings from the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:248–254. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lam JM, Wodchis WP. The relationship of 60 disease diagnoses and 15 conditions to preference-based health-related quality of life in Ontario hospital-based long-term care residents. Med Care. 2010;48:380–387. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca2647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.M174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fries BE, Simon SE, Morris JN, Flodstrom C, Bookstein FL. Pain in U.S. nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the minimum data set. Gerontologist. 2001;41:173–179. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skronda A.. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, vol. Volume I: Continuous Responses. 3rd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eggermont LHP, Leveille SG, Shi L, et al. Pain characteristics associated with the onset of disability in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly Boston study. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sinclair AJ, Girling AJ, Bayer AJ. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. All Wales Research into Elderly (AWARE) Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2000;50:203–212. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(00)00195-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mcalister C, Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Lamb R. Examination of variables that may affect the relationship between cognition and functional status in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;31:123–147. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hedinger D, Hämmig O, Bopp M; Swiss National Cohort Study Group Social determinants of duration of last nursing home stay at the end of life in Switzerland: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:114. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0111-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kelly A, Conell-Price J, Covinsky K, et al. Length of stay for older adults residing in nursing homes at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1701–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03005.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wodchis WP, Austin P, Newman A, Corallo A, Henry D. The concentration of health care spending: little ado (yet) about much (money). Montreal, QC: CAHSPR; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Forder J, Fernandez JL.. Length of Stay in Care Homes. Canterbury, UK: Bupa Care Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glenny C, Stolee P, Thompson M, Husted J, Berg K. Underestimating physical function gains: comparing FIM motor subscale and interRAI post acute care activities of daily living scale. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2012;93:1000-1008. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.