Abstract

Background

Rats (Rattus spp.) invaded most of the world as stowaways including some that carried the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the cause of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in humans and other warm-blooded animals. A high genetic diversity of A. cantonensis based on short mitochondrial DNA regions is reported from Southeast Asia. However, the identity of invasive A. cantonensis is known for only a minority of countries. The affordability of next-generation sequencing for characterisation of A. cantonensis genomes should enable new insights into rat lung worm invasion and parasite identification in experimental studies.

Methods

Genomic DNA from morphologically verified A. cantonensis (two laboratory-maintained strains and two field isolates) was sequenced using low coverage whole genome sequencing. The complete mitochondrial genome was assembled and compared to published A. cantonensis and Angiostrongylus malaysiensis sequences. To determine if the commonly sequenced partial cox1 can unequivocally identify A. cantonensis genetic lineages, the diversity of cox1 was re-evaluated in the context of the publicly available cox1 sequences and the entire mitochondrial genomes. Published experimental studies available in Web of Science were systematically reviewed to reveal published identities of A. cantonensis used in experimental studies.

Results

New A. cantonensis mitochondrial genomes from Sydney (Australia), Hawaii (USA), Canary Islands (Spain) and Fatu Hiva (French Polynesia), were assembled from next-generation sequencing data. Comparison of A. cantonensis mitochondrial genomes from outside of Southeast Asia showed low genetic diversity (0.02–1.03%) within a single lineage of A. cantonensis. Both cox1 and cox2 were considered the preferred markers for A. cantonensis haplotype identification. Systematic review revealed that unequivocal A. cantonensis identification of strains used in experimental studies is hindered by absence of their genetic and geographical identity.

Conclusions

Low coverage whole genome sequencing provides data enabling standardised identification of A. cantonensis laboratory strains and field isolates. The phenotype of invasive A. cantonensis, such as the capacity to establish in new territories, has a strong genetic component, as the A. cantonensis found outside of the original endemic area are genetically uniform. It is imperative that the genotype of A. cantonensis strains maintained in laboratories and used in experimental studies is unequivocally characterised.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-019-3491-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rat lungworm, Mitochondrial genome, Genetic diversity, Invasive species, Next-generation sequencing, Rat lungworm, cox1, Rattus

Background

Biological invasions are a recognised outcome of global change [1, 2]. Historically, non-native species were introduced into new areas by the movement of people and goods, [3–6]. The rat (Rattus spp.) is recognised globally as an invasive species (GISD 2018: http://www.iucngisd.org) [7, 8]. Rats were accompanied by their pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, protozoans, helminths and ectoparasites [9]. The rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Strongylida: Metastrongylidae), is a cause of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in humans and animals [10]. The first documented outbreaks of human disease due to A. cantonensis occurred in Tahiti and Hawaii in the 1950s [11, 12]. The nematode A. cantonensis was described from rat lungs in the Guangzhou region in China and Taiwan more than 30 years earlier [13, 14], with the first human case reported during World War 2 (WW2) in a patient domiciled in Taiwan.

The life-cycle of A. cantonensis is sustained between rats, where the adult helminths are confined to the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle, and a range of molluscs, crustaceans, planarians and for example frogs serving as intermediate and transport hosts, respectively [15–17]. Humans, companion animals and wildlife are accidental dead-end hosts for A. cantonensis. Although such infections are unimportant to the sustainability of A. cantonensis, they may lead to severe, even fatal, infections in these accidental hosts [18–20]. One theory concerning the emergence of A. cantonensis outside Southeast Asia following WW2 states that invasion was facilitated by the introduction of the giant African snail, Achatina fulica that permitted the parasite to flourish. Alternatively, A. cantonensis might have been carried within the snail across the Pacific, where rats had already been established [21–23]. Reports of newly invaded territories keep occurring, e.g. Canary Islands (2010), Uganda (2012) and Oklahoma, USA (2015), although the exact timing and the route of the invasions remains largely uncharacterised [24–26].

Southeast Asia (including China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar) is considered to be the original endemic region for A. cantonensis [21, 22, 27–35]. In Japan, Tokiwa et al. [33] suggested colonization of the area by multiple genetic lineages spreading from the south to the north of Japan. The majority of phylogeographic studies have local character and are based on partial sequences [36]. Data on genetic and phenotypic diversity of A. cantonensis within invaded regions remain scarce [10, 37–40]. A recent study has shown that the pathogenicity of A. cantonensis for its laboratory host(s) varied between different A. cantonensis genetic lineages [41]. The range of A. cantonensis phenotypes in rats and molluscs from inside and outside of Southeast Asia may imply that only certain A. cantonensis genetic lineages are capable of invading other territories.

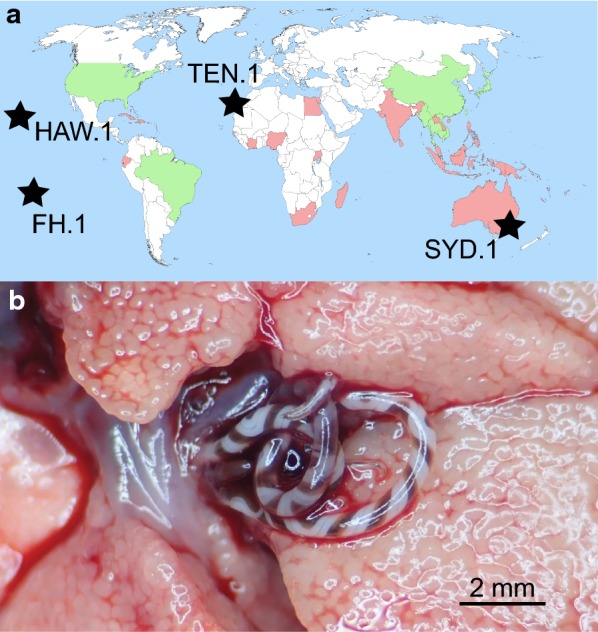

The aim of this study was to determine the extent of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) diversity of A. cantonensis outside Southeast Asia. We used whole genome low coverage next-generation sequencing to obtain complete mtDNA of A. cantonensis originating from four geographically distant regions where it represents an important public health concern: (i) Sydney (Mosman, NSW, Australia); (ii) Fatu Hiva Island (Marquesas, French Polynesia); (iii) Hawaii Island (Hawaii, USA); and (iv) Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain) (Fig. 1). The low mtDNA diversity of invading A. cantonensis observed prompted us to review published experimental studies to determine the identity of A. cantonensis isolates used in experimental studies. The suitability of partial cox1 to unequivocally identify genetic lineages for A. cantonensis was evaluated in the context of all available sequence data and the entire mtDNA genome.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (a) and localization within a rat (b). Locality of material examined in this study (black stars). The original endemic region of A. cantonensis is Southeast Asia (China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar). Countries where A. cantonensis is present (a) and cox1 sequence is publicly available (green). Countries where A. cantonensis is present but with no cox1 genetic confirmation (red). Several adult females of A. cantonensis inhabiting the pulmonary artery (which has been slit open) of Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans) from Hawaii Island, Hawaii (b). The map was created based on references cited by Barratt et al. [10]

Results

Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Pacific and Atlantic regions determined by morphology and cox1 sequence

Adults of A. cantonensis from the Pacific region (Fatu Hiva, Marquesas, French Polynesia; Hawaii Island, Hawaii, USA; Sydney, Australia) and Atlantic region (Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain) were morphologically consistent with the original description and re-description of A. cantonensis sensu Chen, 1935 and sensu Bhaibulaya, 1968, respectively [13, 42]. The spicules of the caudal end of A. cantonensis males examined exceeded 1 mm [Sydney specimen: 1.2–1.5 mm (SYD, n = 6); Fatu Hiva specimen: 1.1–1.2 mm (FH, n = 3); Hawaii specimen: 1.3 mm (HAW, n = 1); Canary Islands: 1.2–1.3 mm (TEN, n = 5), Fig. 2a]. Partial cox1 sequences (primers LCO1490 and HCO2160) of selected vouchers from each series were > 98% identical to the reference A. cantonensis cox1 sequence (strain AC3; KT947978).

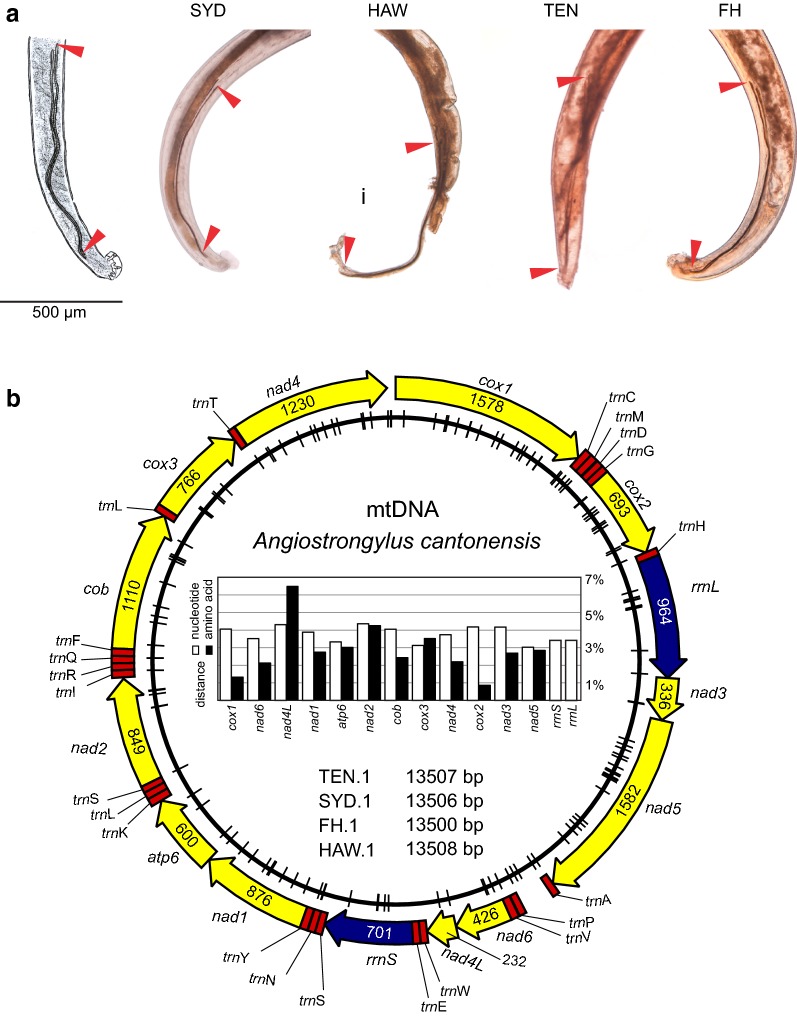

Fig. 2.

Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Sydney, Australia (SYD), Hawaii, USA (HAW), Tenerife, Spain (TEN) and Fatu Hiva, French Polynesia (FH). Caudal parts of male A. cantonensis specimens and the original illustration (left) of the species [13]. Length of the spicules (red arrowheads). The tail of the HAW male is damaged, with no effect on the spicules structure (a). Diagram of mitochondrial genomes of A. cantonensis obtained in our study with defined genes (length indicated on the annotation) and trn regions. Dashes on the inner circle localize SNP sites across sequenced vouchers (SYD.1, HAW.1, TEN.1, FH.1). The graph shows the highest pairwise nucleotide and amino acid sequence distances (b)

Low diversity of four invasive Angiostrongylus cantonensis mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA)

Low coverage whole genome next-generation sequencing of A. cantonensis DNA (quantity 36–57 ng) yielded 1.4–5.4 G bp with 89.49–92.99% high quality Q30 of the nucleotides (Table 1). Using MitoBIM, we assembled four (SYD.1, HAW.1, FH.1, TEN.1) complete mtDNA sequences, 13,500–13,508 bp (Fig. 2b). Three independent MitoBIM runs, each initially baited with A. cantonensis mtDNA (NC_013065), returned identical mtDNA sequences. With the aid of the MITOS Web Server and subsequent manual correction, 12 protein-coding genes representing 3426 amino acids (10,278 bp), 22 trn regions and two ribosomal subunits were annotated (Fig. 2b). The partial cox1 sequence obtained by PCR (primers LCO1490-HCO2160, c.650 bp) from the same initial DNA following Sanger sequencing was 100% identical to the mtDNA assembled from the NGS data.

Table 1.

Whole genome next-generation sequencing of Angiostrongylus cantonensis raw data summary

| Identifier | Sequence ID | DNA amount (ng) | Total read bases (G bp) | Total reads (mil) | G-C content (%) | A-T content (%) | Q30 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SYD.1 | JS4458 | 43 | 2.0 | 20.2 | 41.39 | 58.61 | 92.28 |

| HAW.1 | JS4459 | 36 | 5.4 | 53.5 | 41.38 | 58.62 | 89.49 |

| TEN.1 | 6967 | 57 | 2.3 | 22.7 | 41.81 | 58.19 | 92.72 |

| FH.1 | R23-F | 50 | 1.4 | 13.8 | 41.56 | 58.44 | 92.99 |

Note: Paired end 101-bp Illumina sequencing of Nextera XT DNA library. Q refers to Phred Quality Score which is calculated with − 10log10P, where P is probability of erroneous base call. Q30 stands for 1 incorrect base call in 1000

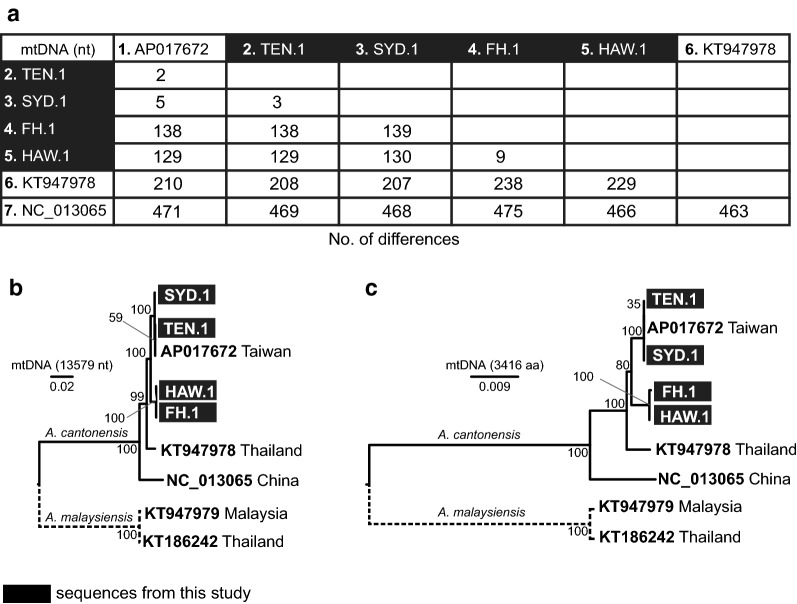

Nucleotide sequence alignment of four A. cantonensis complete mtDNA genomes obtained in this study with three published A. cantonensis mtDNA genomes originating from Southeast Asia [Taiwan (AP017672), Thailand (Isolate AC3, KT947978), China (NC_013065)] was reconstructed (length 13,525 nt). Overall, the four new A. cantonensis mtDNA sequences (SYD.1, TEN.1, HAW.1, FH.1) differed in ≤ 0.02% (3–139 residues) (Fig. 3a), the SYD.1 and TEN.1 differing in only 3 residues (synonymous mutations C/T and G/T located in cox1 and cox2, respectively, and a single nucleotide change in trnN). Similarly, HAW.1 and FH.1 differed in 9 residues: seven indels in rrnL, one indel in a non-coding region between trnP and trnA, and one mutation C/T in cob (position 815) resulting in amino acid A in HAW.1 and V in FH.1, respectively. Compared to published Southeast Asian mtDNA sequences, the greatest similarity was between our isolates and the Taiwanese isolate AP017672, comprising two residue differences (one in rrnL and the other in a non-coding region) from TEN.1 to 138 residues for FH.1 (99 located in protein-coding genes). The highest difference was observed between the Chinese isolate NC_013065 and all the other isolates (463–475 residues/3.4–3.5%) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of seven available complete mtDNA genomes of Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Pairwise sequence distance for all available complete mtDNA sequences (13,525 bp) of A. cantonensis expressed as number of differences (a). Sequence AP017672 originates from Taiwan, KT947978 from Thailand and NC_013065 from China. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree reconstructed from complete nucleotide sequences (b) by TN93 model [60] and from amino acid sequences (c) by JTT model [61]

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees reconstructed from complete mtDNA nucleotide (13,579 nt; Fig. 3b) and amino acid sequences (3,416 aa; Fig. 3c) showed clear separation of A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis clades. The A. cantonensis clade was further divided in four sub-clades comprising (i) Chinese isolate (NC_013065); (ii) Thailand isolate (KT947978); (iii) isolates HAW.1, FH.1; and (iv) including Taiwanese isolate (AP017672), SYD.1 and TEN.1 isolates. All four sub-clades were supported by high bootstrap values (99–100 for nucleotide and 80–100 for amino acid tree; Fig. 3b, c).

The nucleotide pairwise sequence distance percentages (PSDN) calculated for each of the protein-coding genes and rRNA gene subunits varied from 3.0% (nad5) to 4.4% (nad2) (Fig. 2b). The highest amino acid pairwise sequence distance percentage (PSDAA) was observed in the shortest gene nad4L (77 aa). Interestingly, six of seven analysed sequences were identical in this gene, only the Chinese isolate (NC_013065) differed from the others in 5 amino acids. The lowest PSDAA was observed in cox2 (maximum difference 0.9%), representing two polymorphic sites (out of 230) where serine substituted for either asparagine or proline. The second lowest PSDAA was detected in cox1 (maximum difference 1.3%). Six of seven cox1 sequences (525 aa), differed by a single amino acid (V/I in position 516). The sequence of the Chinese isolate (NC_013065) differed from the other six sequences in 6–7 amino acids. The interspecific PSDAA of cox1 sequences between A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis (KT947979) was 12–14 residues (2.3–2.7%).

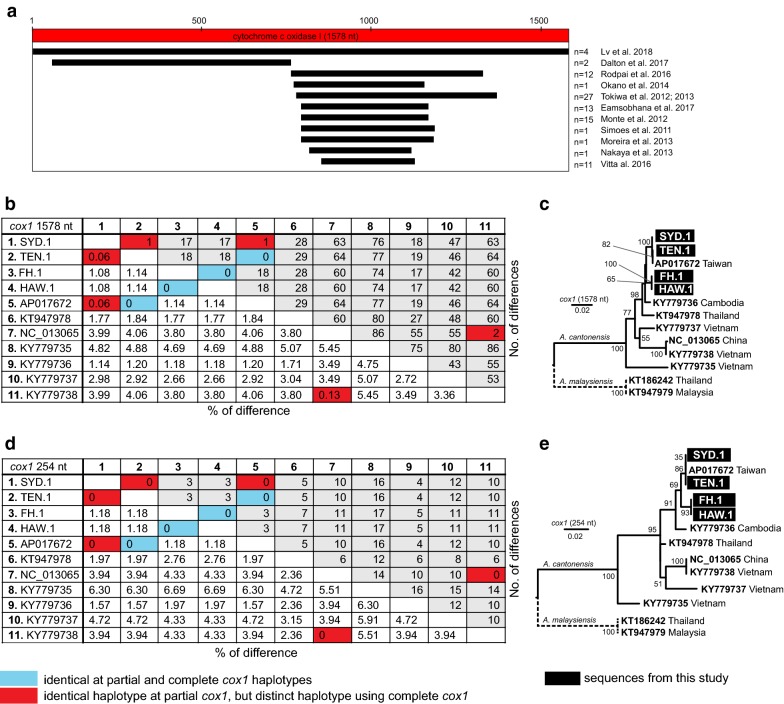

Short overlapping cox1 sequence limits characterization of rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis

Currently, there are 86 A. cantonensis (including 3 complete mtDNA) and 13 A. malaysiensis (including 2 complete mtDNA) cox1 sequences available in public DNA repositories. Six sequences of A. cantonensis (GU138106–11) were excluded from further analyses because they included internal stop codons. The complete coding sequences of cox1 (1578 bp; 525 aa + stop codon) extracted from newly obtained complete mtDNA were aligned with available sequences, demonstrating no gaps and no variation in length (Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). There were 13 complete cox1 sequences (11 for A. cantonensis, 2 for A. malaysiensis) in the final alignment (Fig. 4a, b, c). The remaining sequences were distributed across ten different fragments of cox1 depending on the primer sets used in the respective studies (Fig. 4a). The majority (98%, 95/97) of the A. cantonensis cox1 sequences overlapped in 254-bp region (positions 847–1101). The cox1 sequences MF000735-MF000736 (A. cantonensis from mainland USA) were outside this 254-bp region (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of Angiostrongylus cantonensis diversity at cox1 sequences. Map of cox1 regions amplified by different authors relative to the complete cox1 (a). Pairwise sequence distance expressed as percentage of difference and number of differences for complete cox1 (b). The alignment of complete cox1 included 1,433 (90.1%) conserved, 145 (9.2%) variable and 75 (4.8%) parsimony informative sites and 70 (4.4%) singletons. Maximum likelihood tree reconstructed using the TN93 model [60] from this alignment (c). Pairwise sequence distance expressed as percentage of difference and number of differences for 254-bp region of cox1, where the majority of available sequences overlap (d). Alignment of the 254-bp region included 227 (89.4%) conserved, 27 (10.6%) variable and 13 (5.1%) parsimony informative sites and 14 (5.5%) singletons. Maximum likelihood tree reconstructed using the TN93 model [60] from this alignment (e). In both trees, bootstrap values above 50 are shown

The comparison between PSDN for 11 available complete cox1 and restricted to the 254-bp fragment of the same sequences demonstrated a decrease in the absolute number of polymorphic nucleotide residues (Wilcoxon matched pair test, P-value < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b, d). While sequences SYD.1, TEN.1 and AP017672 represented different haplotypes of complete cox1, in this 254-bp region, they appeared identical. Similarly, sequences KY779738 and NC_013065 were not detected as different haplotypes based on this 254-bp region. The phylogenetic tree reconstructed from the 254-bp alignment of cox1 (Fig. 4e) showed lower resolution of internal relationships within the A. cantonensis clade compared to the tree reconstructed from complete cox1 (Fig. 4c).

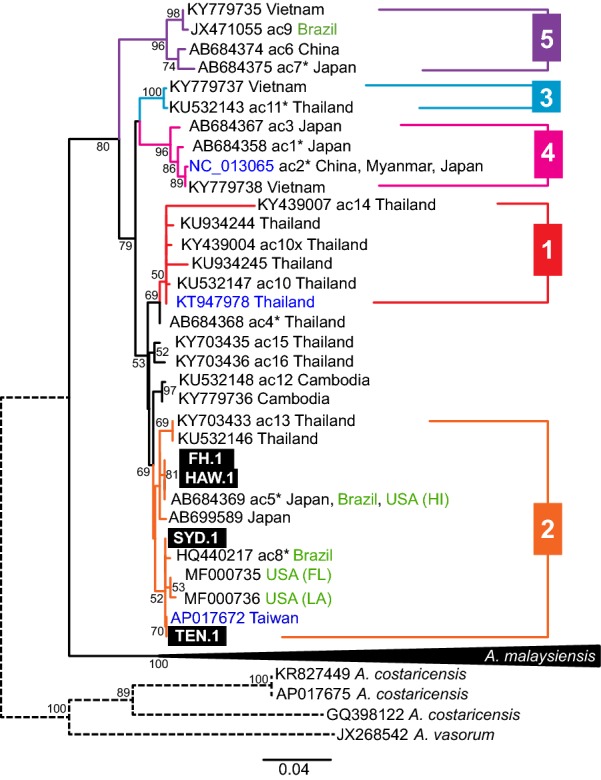

To show relationships between our four newly sequenced isolates and previously published data, the initial dataset was narrowed down to 56 unique cox1 sequences (A. cantonensis, n = 40; A. malaysiensis, n = 12; outgroup, n = 4) and used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree. The alignment consisted of 1581 characters with 1094 (69.1%) conserved, 484 (30.6%) variable and 316 (20%) parsimony informative sites and 168 (10.6%) singletons. Tree topology (Fig. 5) showed separation of A. malaysiensis and A. cantonensis as two distinct clades. Eight sequences named as A. cantonensis downloaded from GenBank clustered within the A. malaysiensis clade (Additional files 6 and 7). These sequences originated from Thailand (n = 7) and Taiwan (n = 1).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of Angiostrongylus cantonensis at cox1. A maximum likelihood tree was inferred using maximum likelihood (GTR+G [59]; bootstrap 100). Each sequence represents a unique haplotype. Bootstrap values noted at the nodes, only values above 50 are shown. Previously named haplotypes (ac1-16) marked. Haplotypes comprising multiple sequences are marked by asterisks. Sequences in green originate outside of the original endemic region of A. cantonensis. Previously published complete mtDNA sequences are presented in blue. Numbering of the subclades is based on Dusitsittipon et al. [36] The clade of A. malaysiensis is collapsed as the species was not focus of our study. The full tree is provided in Additional file 7

All of our four A. cantonensis isolates represented by cox1 clustered together with sequence AP017672 (extracted from mtDNA) to the Clade 2 sensu Dusitsittipon et al. [36]. This clade also contained sequences originating from Brazil, Hawaii and continental USA (Florida and Louisiana). Further subdivision of the subclade was not supported (bootstrap < 50%).

Systematic literature review shows lack of complete characterization of experimentally studied Angiostrongylus cantonensis strains

The Sydney and Fatu Hiva A. cantonensis strains are currently maintained in experimentally infected laboratory rats and snails (Table 2). The literature search yielded 412 articles on A. cantonensis published after 2011, with 104 articles describing experimental work (Additional file 8). The exact origin of A. cantonensis used for the experimental studies was specified in 46% of studies (48/104) and 4% (2/48) provided cox1 to confirm the identity of the parasite (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of Angiostrongylus cantonensis used in this study

| Identifier | Locality of origin, host | Date of collection for analysis | Laboratory strain (laboratory host, year of isolation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FH.1 | Fatu Hiva, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia, Rattus exulans | February 2017 | University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Brno, Czech Republic, Wistar rat, Rattus norvegicus, 2017 |

| TEN.1 | Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain; Rattus norvegicus | April 2018 | – |

| HAW.1 | Hawaii Island, Hawaii, USA; Rattus exulans | May, 2018 | – |

| SYD.1 | Mosman (near Taronga Zoo, Sydney), NSW, Australia; Rattus norvegicus | December, 2017 | Westmead Hospital, NSW, Australia; Wistar rat, Rattus norvegicus, 1997 |

Table 3.

Review of identification of A. cantonensis strains used in experimental studies

| Total | Vertebrate host | Invertebrate host | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics | Pathology | Physiology | Treatment | Pathology | Physiology | ||

| Number of articles | 104 | 3 | 46 | 31 | 12 | 11 | 1 |

| Origin of the strain specified | 48 | 1 | 14 | 17 | 5 | 10 | 1 |

| Helminths sequenced | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cox1 haplotype determined | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

To demonstrate how whole genome sequencing can assist routine nematode characterization, we analysed complete mtDNA genomes of the invasive metastrongylid A. cantonensis originating from four geographically distant areas well outside the endemic range of the parasite in Southeast Asia. Dusitsittipon et al. [36] attempted to synthesize published data on A. cantonensis mtDNA and concluded that detailed morphological and genetic characterization is urgently needed. Our data not only provide complete mtDNA of morphologically identified A. cantonensis vouchers, but the sequence data represent a resource from which other target genes sequences can be extracted.

The circular mtDNA of our A. cantonensis includes two ribosomal subunits, 12 protein-coding genes and 22 trn coding regions, concordant with published results [43, 44]. The generally low mtDNA genetic distance amongst invasive A. cantonensis isolates studied is in stark contrast to the genetic distances observed between Southeast Asian isolates, suggesting that only a limited number of mtDNA haplotypes had the capacity to emerge as globally invasive A. cantonensis [36, 41].

The isolates of A. cantonensis from tropical Pacific islands of Fatu Hiva and Hawaii are almost identical. Similarly, two localities which are almost 20,000 km apart (Sydney and Tenerife) differ by only 3 nucleotides across the entire 13.5 kbp mtDNA. Angiostrongylus cantonensis was first detected in eastern Australia in 1950s, while Tenerife, Canary Islands has only recently been invaded [24, 45, 46]. It would be too speculative to suggest an Australian origin for the recent Tenerife invasion, because we do not know the extent of A. cantonensis diversity in other regions that could have equally been the source population, and there is no plausible historical connection between Australia and the Canary Islands (Fig. 1). Indeed, the Tenerife and Sydney isolates are almost identical to the Taiwanese isolate (AP017672) from BioProject PRJEB493. We speculate that the rapid spread of A. cantonensis in the Pacific region was a consequence of naval operations during and/or after the World War II, because troop and supply ships could readily permit spread of the A. cantonensis infected rats and/or snails. In a telling analogy, A. cantonensis repeatedly colonised Japan during the 20th century, spreading from southern islands to the north resulting in a presence of several different haplotypes from three clades [22].

The phylogeny inferred from partial cox1 sequences corresponds to the tree topography described by Dusitsittipon and colleagues [36]. Numerous haplotypes from different clades detected in China, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia support the theory that A. cantonensis originated historically from Southeast Asia in the same manner as its Rattus hosts [10, 32–34, 47]. In contrast, all but one sequence originating from outside of the endemic range of A. cantonensis cluster within the Clade 2 sensu Dusitsittipon et al. [36], confirming the trend of low diversity for invasive A. cantonensis isolates. The situation in Hawaii might have experienced more complicated scenario, because cob sequences KP721454–55 are distinct from our HAW.1 and exhibit high similarity to the Chinese isolate NC_013065 (Additional file 9). Unfortunately, no detailed information is available on the origin of the previously submitted A. cantonensis (e.g. the particular island) from Hawaii.

The genotypic diversification of a parasite is commonly associated with morphological and biological diversification, enabling the organism to acquire traits that permit invasion of new territories and hosts [48, 49]. The complexity of haplotypes of A. cantonensis suggests variability in its biological traits, but this is yet to be established experimentally [36]. The review of 104 experimental studies involving A. cantonensis revealed that only two studies identified their A. cantonensis genetically using, for example, cox1 [41, 50]. Nevertheless, Lee et al. [50] while comparing infectivity and pathogenicity between what they considered two A. cantonensis (named strain P and H) inadvertently worked with two distinct Angiostrongylus species, because cox1 (strain H; KF591126) clusters within the A. malaysiensis clade in our analyses (Additional file 7).

In the past, obtaining the complete mtDNA of A. cantonensis was accomplished with laborious PCR and primer walking [43, 51]. With the accessibility of next-generation sequencing services, it is logical to consider this methodology for any A. cantonensis laboratory-maintained strain. Such resource can be further mined for other genes of interest, including those under Darwinian selection and therefore informing on phenotypic characterization.

Conclusions

Using whole genome next-generation sequencing methods, we assembled and analysed complete mtDNA of four A. cantonensis isolates originating from four geographically disparate localities outside of the parasite’s endemic range. The observed uniformity of invasive strains implies that only certain A. cantonensis genetic lineages have the capacity to become globally invasive. Our review of published experimental studies demonstrated a need of improved consistency in reporting the identity and origin of tested A. cantonensis. We encourage researchers working with A. cantonensis in laboratories to provide thorough information on their strains, including the origin (country, region, host species) and genetic characterization represented by sharing raw data, or mtDNA sequence or minimally, provide a sequence of complete cox1. Having a resource with standardised good quality information will provide a basis for future studies focused on phenotypic traits of A. cantonensis.

Methods

Collection of adult rat lungworms Angiostrongylus cantonensis

The adults of A. cantonensis were collected from Rattus spp. in four geographically distant localities in the Pacific and Atlantic region and donated for the study as vouchers in 90% ethanol (Fig. 1a, Table 2).

Morphological determination of adult rat lungworms Angiostrongylus cantonensis

All the adult specimens were examined under the light microscope (Olympus BX53 and BX60) equipped with Nomarski interference contrast optics. The morphology was compared to descriptions of A. cantonensis, A. mackerrasae and A. malaysiensis [13, 42, 52, 53]. In male worms, the structure of the copulatory bursa was observed, and spicules were measured as the spicules varying in length from 1.0–1.46 mm, postero-lateral ray significantly shorter than medio-lateral ray and separation of the ventro-ventral from the latero-ventral ray at the point about distal one third of the common trunk are typical features for distinguishing A. cantonensis. Females of A. cantonensis are determined by the length of the vagina in the range 1.5–3.25 mm (2.1 mm on average), by the vulva located 0.16 mm from the anus and finally, by the absence of a minute terminal projection at the tip of the tail [42, 52].

Several specimens from each series were deposited to the helminthological collection of the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Center, České Budějovice (Fatu Hiva and Tenerife material; accession number IPCAS N-260) and to the Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia (Hawaii and Sydney material; accession numbers: W/L HC# N5703–N5711)

Isolation of genomic DNA from tissue segment of adult rat lungworms Angiostrongylus cantonensis

DNA was isolated from dried c.0.5 cm segment of the mid-body using the Nucleospin Tissue XS (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) or Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline, Alexandria, Australia) according to manufacturers’ instructions and eluted in 100 µl of Tris buffer (pH = 8.5). DNA was stored at − 20 °C.

Amplification of cox1 mtDNA from rat lungworms Angiostrongylus cantonensis

Partial sequence of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1) was amplified using primers LCO1490 (forward) and HCO2198 (reverse) [54]. PCR mixtures were prepared using 15 µl of MyTaqTM Red Mix Kit (Bioline, Alexandria, Australia), 10.5 µl of PCR water, 1.25 µl of each of the primers (10 µM) and 2 µl of the template DNA. The PCR protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min; 35 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 55 °C and 10 s at 72 °C; and a final elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were sequenced in Macrogen Inc. (Amsterdam, Netherlands and Seoul, South Korea), the quality of sequences was assessed in CLC Genomic Workbench 6.9.1 (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/) and the sequences were searched through BLAST [55] (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to confirm the identity of the worms.

Sequencing and assembly of the rat lungworms Angiostrongylus cantonensis mtDNA from the whole genome sequencing data

Isolated DNA (36–57 ng; Table 1) was used for Illumina Nextera XT library construction followed by the next-generation sequencing using 100 bp paired end Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing systems utilizing at the depth of 1Gb of raw sequence data (Macrogen, Seoul, Republic of Korea). All four specimens used for the whole genome sequencing were females. The complete mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) was assembled from FastQ data using the MITObim pipeline [56] available at https://github.com/chrishah/MITObim with the sequence of A. cantonensis complete mtDNA (NC_013065) as bait. The assembly was repeated three times with varying percentage of the raw FastQ sequence data used (2–10%), keeping mtDNA coverage at 60–100×. The obtained mtDNA was annotated with the aid of MITOS Web Server [57] available at http://mitos.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/ and aligned with available Angiostrongylus spp. complete mtDNA sequences in CLC Genomics Workbench 6.9.1. for manual validation.

Pairwise sequence distance of complete mtDNA sequences

Newly obtained mtDNA sequences were aligned with published mtDNA sequences of A. cantonensis (AP017672, KT947978, NC_013065) and pairwise sequence distance (PSD) expressed as number of differences was calculated in CLC Genomics Workbench 6.9.1. Another mtDNA sequence (KT186242) labelled as A. cantonensis was not included in our analyses as Dusitsittipon et al. [36] showed that the sequence clusters within the A. malaysiensis clade. To assess intraspecific diversity of individual genes and thus their suitability for phylogenetic studies, all 12 mitochondrial genes were separately translated to amino acids and PSD was calculated for both nucleotide (PSDN) and amino acid (PSDAA) sequences. The PSDN was calculated for both mitochondrial rRNA gene subunits. As cox1 is the most commonly used gene for studying diversity and phylogeography of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, we included cox1 sequence extracted from complete mtDNA of A. malaysiensis (KT947979) for PSDAA calculation, aiming to compare the intra- and interspecific variability. The maximum likelihood trees were constructed from complete nucleotide mtDNA sequences and from amino acid sequences of the 12 protein-coding genes in MEGA X [58] using sequences of A. malaysiensis (KT186242, KT947979) as outgroup. The model was selected by model test implanted in MEGA X.

Analysis of cox1 alignment and maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of cox1 sequences

Complete sequences of cox1 were extracted from available A. cantonensis mtDNA (n = 7) and all cox1 sequences labelled as A. cantonensis were downloaded from GenBank. The geographical location of all isolates was recorded. All sequences were aligned in CLC Genomics Workbench 6.9.1 and the alignment was manually checked for gaps and stop-codons. As we determined that the majority of sequences overlapped in a short fragment (254 nt) of cox1, we decided to compare the information contained in this fragment with the information from complete cox1. The PSDN expressed as number of differences and percentage of difference was calculated for 11 available complete cox1 sequences (7 extracted from complete mtDNA and 4 sequences KY779735–KY779738) and for the overlapping 254-bp fragment of the same 11 sequences. Paired values were compared using Wilcoxon matched pair test (GraphPad Prism 7.02, GraphPad, CA) at significance level P-value 0.05. Number of singletons, conserved, variable and parsimony informative sites were recorded, and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed in MEGA X [58] from both alignments using cox1 sequences of A. malaysiensis (KT186242, KT947979) as the outgroup. The GTR+G model was chosen by model test integrated in MEGA X [58] software. The phylogenetic relationships of the taxa were tested by 100 replicates of bootstrap. To provide corroborating evidence using an alternative gene, we analysed cob of A. cantonensis (Additional file 9).

To compare diversity of all available A. cantonensis cox1 sequences, a maximum likelihood tree was constructed. The alignment comprised one sequence representing each recognised A. cantonensis haplotype. As there are apparently sequences (including a mitochondrial genome accession number KT186242), labelled as A. cantonensis, which are in fact A. malaysiensis (see Dusitsittipon et al. [58]), sequences of A. malaysiensis (n = 13) were added to the analysis as the A. cantonensis sibling species and for the verification of the GenBank sequences taxonomic identity. Complete cox1 sequences extracted from mtDNA of A. costaricensis (AP017675, GQ398122, KR827449) and A. vasorum (JX268542) were used as outgroups. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed in MEGA X [58] by the GTR+G model [59] chosen by the model test implemented within the software. The phylogenetic relationships of the taxa were tested using 100 replicates of bootstrap.

Systematic review of A. cantonensis literature published between 2011–2019

On January 9, 2019, we searched the Web of Science database using the keywords “Angiostrongylus” AND “cantonensis”. Because the first cox1 sequence of A. cantonensis was published in 2011 [40], we limited the search to articles published between 2011 and 2019. The next step was identification of experimental studies using A. cantonensis. The inclusion criteria were: (i) the authors infected any vertebrate or invertebrate host in the laboratory irrespective of which aspect of the infection was being studied, including investigations concerning biological traits of the parasite or even just aspects of the life-cycle of the parasite; and (ii) experiments where in vitro cultivation of any parasite stage was the objective of the study. Phylogeographic studies, case reports, reviews or reports of new occurrence were not evaluated as experimental. The decision as to whether the study was or was not experimental was based on reading the abstracts, or the full-text (if it was not clear from the abstract).

Experimental studies were further classified based on the type of the host investigated (vertebrate or invertebrate) and objectives of the study (diagnostics, pathology, physiology, treatment) based on reading the abstract or full-text. As our aim was to determine the amount of information provided on laboratory-maintained strains of A. cantonensis, full-texts were manually searched for any information on how the authors obtained the helminths for the experiment(s), including reference to a previous publication, whether the isolate comes from nature/other laboratory or if the isolate is maintained in the laboratory on a long-term basis, etc., and also, if any DNA characterization of the strain was attempted. Thus, the results were tabulated in categories: (i) origin of the helminths specified; (ii) any DNA marker sequenced; (iii) cox1 haplotype determined.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Alignment S1. Alignment of complete mtDNA sequences of all available A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis in FASTA format.

Additional file 2: Alignment S2. Alignment of complete mtDNA sequences of all available A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis in CLC format including annotations.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Overview of Angiostrongylus cantonensis cox1 sequences from GenBank. Sequences in bold represent the given haplotype in the cox1 phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). Abbreviation: mtDNA, sequence was extracted from complete mtDNA.

Additional file 4: Alignment S3. Alignment of complete cox1 sequences used for PSD table and maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 4b, c.

Additional file 5: Alignment S4. Alignment of 254-bp fragment of cox1 sequences used for PSD table and maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 4d, e.

Additional file 6: Alignment S5. Alignment of cox1 sequences used for construction of maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 5.

Additional file 7: Tree S1. Full maximum likelihood tree of cox1 from Fig. 5 where the A. malaysiensis clade is not collapsed.

Additional file 8: Table S2. List of publications used in our literature review.

Additional file 9: Text S1. Analysis of diversity of cob in invasive lineages of A. cantonensis.

Acknowledgements

We thank ‘Excmo. Cabildo Insular’ of Tenerife for allowing us to conduct the field study. We thank the Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, The University of Sydney for hosting BČ during her postdoctoral fellowship. We thank Dave Spratt (CSIRO) for discussions and insight into the Angiostrongylus biology.

Funding

The work in Tenerife was supported by “Proyectos I + D de la Consejeria de Economía, Industria, Comercio y Conocimiento de la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias” and FEDER 2014-2020 [grant number ProID2017010092]; Red de Investigación de Centros de Enfermedades Tropicales-RICET [grant number RD16/0027/0001]; ISCIII-Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa RETICS, Ministry of Health and Consumption, Spain (PF, AM). This study is outcome of project International Collaboration in ecological and evolutionary biology of vertebrates (CZ02.2.69/0.0/0.0/16_027/0008027) within operational program Research, Development and Education controlled by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic funded by the European Structural and Investing Funds which supported the postdoctoral internship of BČ at the University of Sydney. Maintenance of Fatu Hiva isolates at UVPS was supported by grant of the Internal Grant agency of UVPS Project No. 123/2018/FVL (DM, BF). KH has been financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the project CEITEC 2020 (LQ1601).

Availability of data and materials

Sequence data were deposited at SRA NCBI BioProject: PRJNA533181. The complete mtDNA genome sequences were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers MK570629 (TEN.1), MK570630 (HAW.1), MK570631 (SYD.1), MK570632 (FH.1). Vouchers from Hawaii (HAW) and Sydney (SYD) were deposited in the Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia under the accession numbers: W/L HC# N5703–N5711. Vouchers from Fatu Hiva (FH) and Tenerife (TEN) were deposited in the helminthological collection of Institute of Parasitology, Biology Center, České Budějovice, under the accession number IPCAS N-260.

Authors’ contributions

BČ carried out bioinformatics and data analysis, results interpretations and drafted the manuscript; BF provided systematic literature analysis. BČ, BF isolated DNA and carried out PCR analysis and morphological determination. RM, JW contributed insight into the historical emergence and clinical disease consequences. DM, KH, PF, AMA, RL, JW, CNN collected and contributed material. JŠ, DM supervised the study and provided resources. JŠ, DM conceived and coordinated the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All isolates were obtained according to local animal ethics guidelines including appropriate permits adhering to local regulations. In Hawaii, USA, wild rats (R. exulans) were live-trapped in May 2018 and humanely euthanised in a CO2 chamber and frozen at − 20 °C. The necropsy was performed in July 2018 and worms were extracted from pulmonary artery of a single male rat. All animal procedures were conducted according to the Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and following the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols (QA-2835; US Department of Agriculture, National Wildlife Research Center). In Tenerife, Spain, wild rats (R. rattus and R. norvegicus) were live-trapped in April 2018 in the forested area of Parque Rural de Anaga. Captured animals were sacrificed by barbiturate overdose in the laboratories of the Instituto Universitario de Enfermedades Tropicales y Salud Pública de Canarias and necropsied. Worms were extracted from pulmonary artery of a single adult R. norvegicus. All the animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of animal welfare in experimental science and the European Union legislation (Directive 86/609/EEC). In Sydney, adult worms were harvested from the lungs of laboratory Wistar rats experimentally infected with A. cantonensis. This parasite culture originated from a wild rat (Rattus norvegicus) caught around the Taronga Park Zoological Gardens in Sydney about 30 years ago. A live culture of these worms has been maintained in the laboratory (Western Sydney Local Health District Animal Ethics approval number 8002.02.13). Adult worms were frozen at − 20 °C until extracted and sequenced. In Fatu Hiva, French Polynesia, the rats (co-occurring R. rattus, R. exulans) were trapped in snap traps in February 2017 at the edge of Omoa village, the worms used in the current study were extracted from the pulmonary artery of a single male R. exulans. All the animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of animal welfare in experimental science and the European Union legislation (Directive 86/609/EEC).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acid

- bp

base pairs

- cox1

gene for subunit 1 of cytochrome c oxidase

- cox2

gene for subunit 2 of cytochrome c oxidase

- cob

gene for cytochrome b

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- nad2

gene for subunit 2 of NADH dehydrogenase

- nad5

gene for subunit 5 of NADH dehydrogenase

- nad4L

gene for subunit 4L of NADH dehydrogenase

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- nt

nucleotide

- PSD

pairwise sequence distance

- PSDN

pairwise sequence distance of nucleotide sequences

- PSDAA

pairwise sequence distance of amino acid sequences

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Barbora Červená, Email: bara.cervena@gmail.com.

David Modrý, Email: modryd@vfu.cz.

Barbora Fecková, Email: barborafeckova.vet@gmail.com.

Kristýna Hrazdilová, Email: kristyna@hrazdilova.cz.

Pilar Foronda, Email: pforonda@ull.edu.es.

Aron Martin Alonso, Email: amalonso@ull.edu.es.

Rogan Lee, Email: Rogan.Lee@health.nsw.gov.au.

John Walker, Email: johndenisewalker@gmail.com.

Chris N. Niebuhr, Email: niebuhrc@landcareresearch.co.nz

Richard Malik, Email: richard.malik@sydney.edu.au.

Jan Šlapeta, Email: jan.slapeta@sydney.edu.au.

References

- 1.Pysek P, Richardson DM. Invasive species, environmental change and management, and health. Annu Rev Env Resour. 2010;35:25–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-033009-095548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simberloff D, Martin JL, Genovesi P, Maris V, Wardle DA, Aronson J, et al. Impacts of biological invasions: whatʼs what and the way forward. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulme PE. Trade, transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol. 2009;46:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01600.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pejchar L, Mooney HA. Invasive species, ecosystem services and human well-being. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoberg EP. Invasive processes, mosaics and the structure of helminth parasite faunas. Rev Sci Tech. 2010;29:255–272. doi: 10.20506/rst.29.2.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrenfeld JG. Ecosystem consequences of biological invasions. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2010;41:59–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audoin-Rouzeau F, Vigne J-D. La colonisation de l’Europe par le rat noir (Rattus rattus) Rev Paléobiol. 1994;13:125–145. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morand S, Bordes F, Chen HW, Claude J, Cosson JF, Galan M, et al. Global parasite and Rattus rodent invasions: the consequences for rodent-borne diseases. Integr Zool. 2015;10:409–423. doi: 10.1111/1749-4877.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosoy M, Khlyap L, Cosson JF, Morand S. Aboriginal and invasive rats of genus Rattus as hosts of infectious agents. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015;15:3–12. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2014.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barratt J, Chan D, Sandaradura I, Malik R, Spielman D, Lee R, et al. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: a review of its distribution, molecular biology and clinical significance as a human pathogen. Parasitology. 2016;143:1087–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen L, Chappell R, Laqueur GL, Wallace GD, Weinstein PP. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by a metastrongylid lung-worm of rats. JAMA. 1962;179:620–624. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050080032007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen L, Laigret J, Bories S. Observations on an outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis on Tahiti, French Polynesia. Am J Hyg. 1961;74:26–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HT. Un noveau nématode pulmonaire, Pulmonema cantonensis n.g., n.sp. des rats de Canton. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1935;13:312–317. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1935134312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaver PC, Rosen L. Memorandum on the first report of Angiostrongylus in man, by Nomura and Lin, 1945. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1964;13:589–590. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1964.13.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhaibulaya M. Comparative studies on the life history of Angiostrongylus mackerrasae Bhaibulaya, 1968 and Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) Int J Parasitol. 1975;5:7–20. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(75)90091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace GD, Rosen L. Studies on eosinophilic meningitis. II. Experimental infection of shrimp and crabs with Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Am J Epidemiol. 1966;84:120–131. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JR, Hayes KA, Yeung NW, Cowie RH. Diverse gastropod hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm, globally and with a focus on the Hawaiian Islands. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunn JA, Lee R, Smaller J, MacKay BM, King T, Hunt GB, et al. Twenty two cases of canine neural angiostronglyosis in eastern Australia (2002–2005) and a review of the literature. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma GM, Dennis M, Rose K, Spratt D, Spielman D. Tawny frogmouths and brushtail possums as sentinels for Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm. Vet Parasitol. 2013;192:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker AG, Spielman D, Malik R, Graham K, Ralph E, Linton M, et al. Canine neural angiostrongylosis: a case-control study in Sydney dogs. Aust Vet J. 2015;93:195–199. doi: 10.1111/avj.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alicata JE. Biology and distribution of the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, and its relationship to eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and other neurological disorders of man and animals. Adv Parasitol. 1965;3:223–248. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokiwa T, Hashimoto T, Yabe T, Komatsu N, Akao N, Ohta N. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) infections in invasive rodents from five islands of the Ogasawara Archipelago, Japan. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace GD, Rosen L. Studies on eosinophilic meningitis. I. Observations on the geographic distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Pacific Area and its prevalence in wild rats. Am J Epidemiol. 1965;81:52–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foronda P, Lopez-Gonzalez M, Miquel J, Torres J, Segovia M, Abreu-Acosta N, et al. Finding of Parastrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) in Rattus rattus in Tenerife, Canary Islands (Spain) Acta Trop. 2010;114:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mugisha L, Bwangamoi O, Cranfield MR. Angiostrongylus cantonensis and other parasites infections of rodents of Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda. AJABS. 2012;7:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.York EM, Creecy JP, Lord WD, Caire W. Geographic range expansion for the rat lungworm in North America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1234–1236. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.141980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dusitsittipon S, Criscione CD, Morand S, Komalamisra C, Thaenkham U. Cryptic lineage diversity in the zoonotic pathogen Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;107:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dusitsittipon S, Thaenkham U, Watthanakulpanich D, Adisakwattana P, Komalamisra C. Genetic differences in the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae), in Thailand. J Helminthol. 2015;89:545–551. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X14000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eamsobhana P, Lim PE, Solano G, Zhang HM, Gan XX, Sen Yong H. Molecular differentiation of Angiostrongylus taxa (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) by cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene sequences. Acta Trop. 2010;116:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eamsobhana P, Song SL, Yong HS, Prasartvit A, Boonyong S, Tungtrongchitr A. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I haplotype diversity of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Acta Trop. 2017;171:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv S, Guo YH, Nguyen HM, Sinuon M, Sayasone S, Lo NC, et al. Invasive Pomacea snails as important intermediate hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam: Implications for outbreaks of eosinophilic meningitis. Acta Trop. 2018;183:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodpai R, Intapan PM, Thanchomnang T, Sanpool O, Sadaow L, Laymanivong S, et al. Angiostrongylus cantonensis and A. malaysiensis broadly overlap in Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar: a molecular survey of larvae in land snails. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tokiwa T, Harunari T, Tanikawa T, Komatsu N, Koizumi N, Tung KC, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, isolated from different geographical regions revealed widespread multiple lineages. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitta A, Srisongcram N, Thiproaj J, Wongma A, Polsut W, Fukruksa C, et al. Phylogeny of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Thailand based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene sequence. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2016;47:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yong HS, Eamsobhana P, Song SL, Prasartvit A, Lim PE. Molecular phylogeography of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) and genetic relationships with congeners using cytochrome b gene marker. Acta Trop. 2015;148:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dusitsittipon S, Criscione CD, Morand S, Komalamisra C, Thaenkham U. Hurdles in the evolutionary epidemiology of Angiostrongylus cantonensis: pseudogenes, incongruence between taxonomy and DNA sequence variants, and cryptic lineages. Evol Appl. 2018;11:1257–1269. doi: 10.1111/eva.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalton MF, Fenton H, Cleveland CA, Elsmo EJ, Yabsley MJ. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis associated with rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) migration in two nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and an opossum (Didelphis virginiana) in the southeastern United States. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2017;6:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monte TCC, Simoes RO, Oliveira APM, Novaes CF, Thiengo SC, Silva AJ, et al. Phylogenetic relationship of the Brazilian isolates of the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) employing mitochondrial COI gene sequence data. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:248. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreira VLC, Giese EG, Melo FTV, Simoes RO, Thiengo SC, Maldonado A, et al. Endemic angiostrongyliasis in the Brazilian Amazon: natural parasitism of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus, and sympatric giant African land snails, Achatina fulica. Acta Trop. 2013;125:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simões RO, Monteiro FA, Sanchez E, Thiengo SC, Garcia JS, Costa-Neto SF, et al. Endemic angiostrongyliasis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1331–1333. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monte TC, Gentile R, Garcia J, Mota E, Santos JN, Maldonado A. Brazilian Angiostrongylus cantonensis haplotypes, ac8 and ac9, have two different biological and morphological profiles. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:1057–1063. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276130378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhaibulaya M. A new species of Angiostrongylus in an Australian rat Rattus fuscipes. Parasitology. 1968;58:789–799. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000069572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lv S, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Liu Q, Liu HX, Hu L, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the rodent intra-arterial nematodes Angiostrongylus cantonensis and Angiostrongylus costaricensis. Parasitol Res. 2012;111:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yong HS, Song SL, Eamsobhana P, Lim PE. Complete mitochondrial genome of Angiostrongylus malaysiensis lungworm and molecular phylogeny of metastrongyloid nematodes. Acta Trop. 2016;161:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackerras MJ, Sandars DF. The life history of the rat lung-worm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen) (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) Aust J Zool. 1955;3:1–25. doi: 10.1071/ZO9550001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prociv P, Carlisle MS. The spread of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Australia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:126–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verneau O, Catzeflis F, Furano AV. Determining and dating recent rodent speciation events by using L1 (LINE-1) retrotransposons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11284–11289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maldonado Junior A, Zeitone BK, Amado LA, Rosa IF, Machado-Silva JR, Lanfredi RM. Biological variation between two Brazilian geographical isolates of Echinostoma paraensei. J Helminthol. 2005;79:345–351. doi: 10.1079/JOH2005293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gharamah AA, Rahman WA, Azizah MNS. Morphological variation between isolates of the nematode Haemonchus contortus from sheep and goat populations in Malaysia and Yemen. J Helminthol. 2014;88:82–88. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X12000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JD, Chung LY, Wang LC, Lin RJ, Wang JJ, Tu HP, et al. Sequence analysis in partial genes of five isolates of Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Taiwan and biological comparison in infectivity pathogenicity between two strains. Acta Trop. 2014;133:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yong HS, Eamsobhana P, Lim PE, Razali R, Aziz FA, Rosli NSM, et al. Draft genome of neurotropic nematode parasite Angiostrongylus cantonensis, causative agent of human eosinophilic meningitis. Acta Trop. 2015;148:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhaibulaya M, Cross JH. Angiostrongylus malaysiensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae), a new species of rat lung-worm from Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1971;2:527–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yokogawa S. A new species of nematode found in the lungs of rats Haemostrongylus ratti sp. nov. Trans Nat Hist Soc Formosa. 1937;27:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hahn C, Bachmann L, Chevreux B. Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads-a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucl Acids Res. 2013;41:e129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernt M, Donath A, Juhling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, et al. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Alignment S1. Alignment of complete mtDNA sequences of all available A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis in FASTA format.

Additional file 2: Alignment S2. Alignment of complete mtDNA sequences of all available A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis in CLC format including annotations.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Overview of Angiostrongylus cantonensis cox1 sequences from GenBank. Sequences in bold represent the given haplotype in the cox1 phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). Abbreviation: mtDNA, sequence was extracted from complete mtDNA.

Additional file 4: Alignment S3. Alignment of complete cox1 sequences used for PSD table and maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 4b, c.

Additional file 5: Alignment S4. Alignment of 254-bp fragment of cox1 sequences used for PSD table and maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 4d, e.

Additional file 6: Alignment S5. Alignment of cox1 sequences used for construction of maximum likelihood tree in Fig. 5.

Additional file 7: Tree S1. Full maximum likelihood tree of cox1 from Fig. 5 where the A. malaysiensis clade is not collapsed.

Additional file 8: Table S2. List of publications used in our literature review.

Additional file 9: Text S1. Analysis of diversity of cob in invasive lineages of A. cantonensis.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data were deposited at SRA NCBI BioProject: PRJNA533181. The complete mtDNA genome sequences were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers MK570629 (TEN.1), MK570630 (HAW.1), MK570631 (SYD.1), MK570632 (FH.1). Vouchers from Hawaii (HAW) and Sydney (SYD) were deposited in the Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia under the accession numbers: W/L HC# N5703–N5711. Vouchers from Fatu Hiva (FH) and Tenerife (TEN) were deposited in the helminthological collection of Institute of Parasitology, Biology Center, České Budějovice, under the accession number IPCAS N-260.