Abstract

Introduction:

Endemic measles persists in China, despite >95% reported coverage of two measles-containing vaccine doses and nationwide campaign that vaccinated more than 100 million children in 2010. We performed a case–control study in six Chinese provinces during January 2012 through June 2013 to identify risk factors for measles infection among children aged 0–7 months.

Methods:

Children with laboratory-confirmed measles were neighborhood matched with three controls. We interviewed parents of case and control infants on potential risk factors for measles. Adjusted matched odds ratios (mOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by multivariable conditional logistic modeling. We calculated attributable fractions for risk factors that could be interpreted as causal.

Results:

Eight hundred thirty cases and 2303 controls were enrolled. In multivariable analysis, male sex (mOR 1.6 [1.3, 2.0]), age 5–7 months (mOR 3.9 [3.0, 5.1]), migration between counties (mOR 2.3 [1.6, 3.4]), outpatient hospital visits (mOR 9.4 [6.6, 13.3]) and inpatient hospitalization (mOR 107.1 [48.8, 235.1]) were significant risk factors. The calculated attributable fractions for hospital visits was 43.1% (95% CI: 40.1, 47.5%) adjusted for age, sex and migration.

Conclusions:

Hospital visitation was the largest risk factor for measles infection in infants. Improved hospital infection control practices would accelerate measles elimination in China.

Keywords: Measles, Measles elimination, Case–control study, Population immunity, Risk factors, China

1. Introduction

A safe and effective vaccine for measles has been available for more than 50 years, successfully eliminating the disease in many countries. However, an estimated 122,000 measles-related deaths occurred worldwide in 2011 [1]. All six World Health Organization (WHO) regions now have measles elimination goals, but none have yet replicated the success of the WHO Region of the Americas [1]. In 2012, the WHO Western Pacific Region recorded its lowest-ever measles incidence (5.9 per million population) [2], and appeared to be approaching elimination. A large part of this success was due to adramatic reduction in the incidence of measles in China, historically the source of most measles cases in the region, and the primary worldwide reservoir for the H1 measles genotype [3].

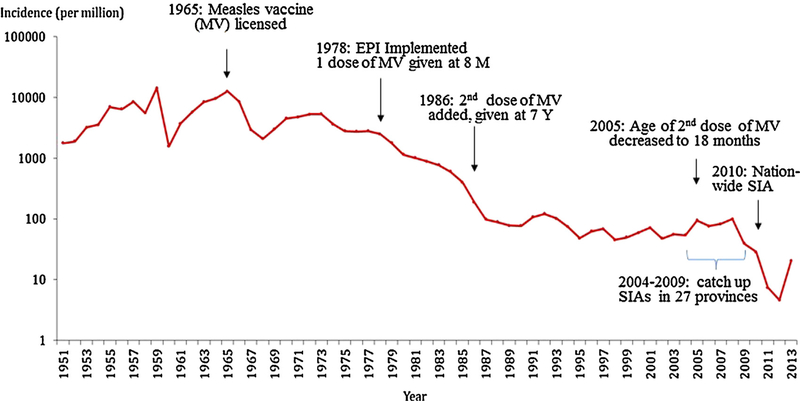

In line with the WHO Western Pacific Region goal of measles elimination by 2012, China in 2006 endorsed an action plan for measles elimination [4]. This plan to rapidly close the immunity gap in children was similar to the successful AMR elimination plan, including a 2-dose routine measles-containing vaccine (MCV) schedule with >95% coverage and use of supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) [5]. In China, a first MCV dose is now given at age 8 months and a second between 18 and 23 months with >95% reported coverage for both doses [6]. To close accumulated immunity gap among children with many measles cases reported, between 2004 and 2009, 27 of 31 mainland provinces conducted unsynchronized province-wide SIAs targeting children aged 8 months to 14 years [6,7]. In September 2010, China conducted a synchronized nationwide SIA and vaccinated more than100 million children aged 8 months to 14 years [8]. After a stable measles incidence of 50–100 cases per million population from1994 to 2008, incidence decreased rapidly in 2011 to 7.4 (Fig. 1). However, endemic measles virus transmission was not interrupted after the campaign [9].

Fig. 1.

Incidence of reported measles cases by year, and the evolution of measles vaccine routine immunization schedule—China, 1951–2013. Abbreviation: MV, measlesvaccine; SIAs, supplementary immunization activities; M, months; Y, years.

National measles surveillance in China has shown an increasing proportion of cases in infants <8 months old, a remarkable decrease in incidence and percentage of cases in children aged 8 months to 14 years old, and an increase in the proportion of cases, but not overall incidence, in adults aged ≥15 years. Between 1993 and2013, the proportion of measles cases among those aged <8 months increased from <5% [10] to 31% [11]. Among children aged 8 months to 14 years, the proportion of cases decreased from 83% to 42%; and adult measles cases increased from 12% to 27% [10,11]. Infants <8 months old are not eligible for measles vaccination, unfortunately, this age group has had the highest incidence of measles in China since 2005 [8,12–14]. In 2013, the median age of confirmed measles case-patients in China decreased to 11 months, the lowest since measles surveillance began [9].

The notably low measles incidence after the nationwide measles SIA in 2010 provided an opportunity to assess the impact and limitations of a vaccination strategy targeting children in epidemiological situations where infants younger than the recommended age for vaccination make up most measles case-patients [9]. As risk factors for measles likely differ by age group, we conducted a case–control study during 2012–2013, after the nationwide SIA, to identify risk factors for measles infection among infants, children, and adults, and to guide further measles elimination efforts in China. In this paper, we report results for infants aged ≤7 months.

2. Methods

2.1. Study location and time

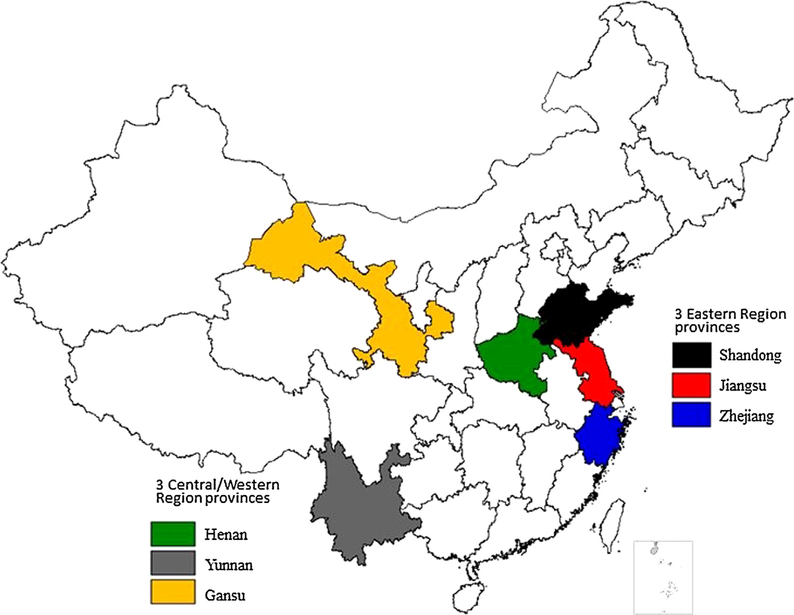

Since 1986, China’s 31 mainland provinces have been divided into three groups according to economic and social development: eastern, central, and western regions [6,15]. We selected six provinces for the study based on geographic groupings mentioned above, an incidence of measles during 2005–2010 of >40cases per million population, sustained measles virus transmission in 2011, and >50% of cases occurring in infants aged 0–7 months and adults aged ≥15 years. On the basis of these criteria, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong were selected from the more developed eastern region, and Henan, Gansu, and Yunnan from the less developed central and western regions (Fig. 2). These six provinces have a total population of around 394.5 million, 29.6% of the total population of China in 2010 [16]. The study sought to investigate all laboratory-confirmed measles cases reported from these provinces from January to December 2012. Because the number of reported cases did not meet the estimated sample size requirement by the end of 2012 (see below), we extended the study for 6 more months to cover the 2013 peak measles season.

Fig. 2.

Provinces participating in the case control study—China, 2012–2013.

2.2. Sample size

For sample size calculation and data analysis, we combined cases from the central and western regions because of overall similar demographics and measles epidemiology. We calculated sample size separately for each of three age groups (infants, children and adults, as defined above). For infants, assuming a risk factor prevalence in controls of 30%, 134 infant cases with three matched neighborhood controls in each of the eastern and central/western regions would provide a 90% power to detect an odds ratio (OR) >2 with 95% confidence [17,18]. To account for a possible non-participation rate of 10%, we sought to investigate 150 infant cases per area.

2.3. Case selection

A case-based measles surveillance system with laboratory support has been in place in China since 2009 [19]. Once a suspected measles case seeks health care, the healthcare provider is expected to report the case within 24 h. Suspected measles cases are confirmed based on laboratory findings, an epidemiologic link, or clinical criteria. For this study, only case-patients confirmed by positive IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (SERION ELISA anti-measles virus IgM, Institut Virion\Serion GmbH) or isolation of measles virus in a WHO Global Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network accredited laboratory were enrolled. Case-patients were excluded if they received MCV 7–14 days before rash onset [20] or declined to participate in the study. Cases were enrolled in each province until the calculated sample size was reached for each age group or through June 2013, whichever came first.

2.4. Control selection

We enrolled three 0–7 month old neighborhood matched controls for each 0–7 month case-patient. Controls were selected starting with the household closest to that of the case-patient. If more than one age eligible individual lived in the household, we selected the one closest in age to the case-patient. Subsequent households were visited until three eligible controls were found and enrolled. Potential controls were excluded if caregivers refused consent for study participation or if the control infants had a history of fever and rash in the previous 3 months, to ensure that they were unlikely to be undiagnosed measles cases.

2.5. Data collection

Trained investigators conducted in-house face-to-face interviews with parents of case-patients and controls using a standard questionnaire. Variables collected included demographic characteristics, hospital exposure, routine vaccination history, and any reasons for non-vaccination if appropriate, health care service utilization and access, and migration status. Receipt of routine vaccines was determined by household-retained vaccination card, clinic-based vaccination records, or parental recall if written vaccination records were unavailable. Migration status was defined by either a personal history of the child having at least one previous residence outside of the current county of residence or a family history of ever having migrated from a different county, prefecture, or province to the current place of residence.

2.6. Data analysis

A summary description of demographic variables and risk factors of interest was completed for all cases and controls. Matched odds ratios (mORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk factors were calculated via conditional logistic regression overall and by region. Adjusted matched odds ratios were obtained from a multivariable conditional logistic model. Model building sequentially assessed each factor’s significance adjusted for other variables in the model, as well as effect modification on the primary variable of interest, hospital visits for reason other than vaccination. Attributable fractions (AF) were calculated for those exposure risk factors that could be interpreted as causal, using the formula: AF = P[E|D] × (1 − (1/mOR)), where P[E|D] is the observed prevalence of the exposure among cases. We used bootstrapping to calculate a 95% CI for the AF by repeatedly sampling with replacement n matched sets, where n is the total number of matched sets available in the analysis [21]. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of 500 estimated AFs define the 95%CI.

2.7. Ethical considerations

We obtained written informed consent from parents or guardians of participating children. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by both the Ethics Review Committee of the WHO Regional office for Western Pacific Region (Unique ID Number: 2011.24.CHN.05.EPI), and the Ethical Review Committee of China Center for disease control and prevention (Unique ID Number: 201117).

3. Results

From January 2012 through June 2013, the six study provinces reported 30,249 suspected measles cases (32.3% of the national total), of which 5978 (19.8%) were eventually classified as measles. Among these 5978 case-patients, 5876 (98.3%) were laboratory confirmed, 6 (0.1%) were epidemiologically confirmed and 96 (1.6%) were clinically compatible. Among the laboratory confirmed cases, 1730 (29.4%) were in infants aged <8 months, 2164 (36.9%) were children aged 8 months through 14 years, and 1982 (33.7%) were in adults aged ≥15 years. The percentage of measles cases in infants aged <8 months ranged from 22.5% in Gansu to 39.8% in Henan. During this period, six measles-related deaths were reported in the six provinces; three of these deaths were in infants <8 months. Among 471 cases of all ages with genotype results, 439 (93.2%) were H1, and 32 (6.8%) were D9 genotype (30 from Yunnan province and 2 from Shandong province).

In total, 830 (47%) case-patients aged <8 months were enrolled in this study: 360 from the eastern region and 470 from central/western region. Yunnan contributed the largest number of case-patients (254), followed by Henan (182), Shandong (177), Zhejiang (143), Jiangsu (40), and Gansu (34). Enrolled and non-enrolled case-patients did not significantly differ by age group (χ2 = 0.008, p = 0.93) or sex (χ2 = 0.21, p = 0.65). The number of case-patients increased progressively with age from three in the <1-month-oldage-group to 259 in the 7-month-old age-group; 79% of cases were in 5–7 month old children (Table 1). Among all potential control infants approached, 2520 controls were enrolled, 25 refused con-sent for participation, and two were excluded for a history of fever and rash in the past 3 months. After enrollment, 217 (8.5%) control infants were excluded from analysis because they were aged >8 months; therefore, 2303 controls were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of measles cases and age-matched controls aged 0–7 months stratified by geographic area—China, 2012–2013.

| Eastern region, N (%) |

Central/western region, N (%) |

Total, N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 360) | Controls (n = 1046) | Cases (n = 470) | Controls (n = 1257) | Cases (n = 830) | Controls (n = 2303) | |

| Sex (male) | 242 (67) | 572 (55) | 313 (67) | 683 (54) | 555 (67) | 1255 (54) |

| Age (months) | ||||||

| 0 | 2 (1) | 14 (1) | 1 (0) | 26 (2) | 3 (0) | 40 (2) |

| 1 | 1 (0) | 59 (6) | 6 (1) | 99 (8) | 7 (1) | 158 (7) |

| 2 | 7 (2) | 94 (9) | 11 (2) | 132 (11) | 18 (2) | 226 (10) |

| 3 | 12 (3) | 122 (12) | 32 (7) | 179 (14) | 44 (5) | 301 (13) |

| 4 | 42 (12) | 157 (15) | 59 (13) | 179 (14) | 101 (12) | 336 (15) |

| 5 | 69 (19) | 189 (18) | 82 (17) | 201 (16) | 151 (18) | 390 (17) |

| 6 | 105 (29) | 206 (20) | 142 (30) | 222 (18) | 247 (30) | 428 (19) |

| 7 | 122 (34) | 205 (20) | 137 (29) | 219 (17) | 259 (31) | 424 (18) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 0–4 months | 64 (18) | 446(43) | 109 (23) | 615 (49) | 173 (21) | 1061 (46) |

| 5–7 months | 296 (82) | 600 (57) | 361 (77) | 642 (51) | 657 (79) | 1242 (54) |

| Vaccination card (yes) | 356 (99) | 1036 (99) | 460 (98) | 1218 (97) | 816 (98) | 2254 (98) |

| Received all eligible doses (yes) | 196 (58) | 847 (85) | 226 (56) | 909 (83) | 422 (57) | 1756 (84) |

| Mothers education | ||||||

| ≤Primary school | 27 (8) | 71 (7) | 99 (21) | 245 (20) | 126 (15) | 316 (14) |

| Middle school | 292 (82) | 821 (79) | 343 (74) | 941 (75) | 635 (78) | 1762 (77) |

| ≥College | 36 (10) | 150 (14) | 22 (5) | 65 (5) | 58 (7) | 215 (9) |

| Fathers education | ||||||

| ≤Primary school | 19 (5) | 37 (4) | 81 (17) | 170 (14) | 100 (12) | 207 (9) |

| Middle school | 280 (79) | 820 (79) | 360 (77) | 1003 (80) | 640 (78) | 1823 (80) |

| ≥College | 57 (16) | 184 (18) | 25 (5) | 76 (6) | 82 (10) | 260 (11) |

| Type of house | ||||||

| Multistory building | 191 (53) | 550 (53) | 172 (37) | 447 (36) | 363 (44) | 997 (43) |

| Single-story house | 156 (43) | 481 (46) | 281 (60) | 773 (62) | 437 (53) | 1254 (55) |

| Other | 12 (3) | 15 (1) | 13 (3) | 31 (2) | 25 (3) | 46 (2) |

| Number of siblings | ||||||

| 0 | 248 (69) | 732 (70) | 248 (53) | 683 (54) | 496 (60) | 1415 (62) |

| 1 | 96 (27) | 274 (26) | 170 (36) | 459 (37) | 266 (32) | 733 (32) |

| ≥2 | 14 (4) | 37 (4) | 51 (11) | 114 (9) | 65 (8) | 151 (7) |

| Primary caretaker | ||||||

| Parents | 322 (90) | 897 (86) | 433 (93) | 1151 (92) | 755 (91) | 2048 (89) |

| Other | 36 (10) | 147 (14) | 35 (7) | 105 (8) | 71 (9) | 252 (11) |

| Change in residence in child | ||||||

| Yes | 49 (14) | 74 (7) | 35 (8) | 38 (3) | 84 (10) | 112 (5) |

| History of family migration | ||||||

| From different province | 75 (21) | 173 (17) | 12 (3) | 40 (3) | 87 (11) | 213 (9) |

| From different prefecture | 92 (26) | 196 (19) | 40 (9) | 87 (7) | 132 (16) | 283 (12) |

| From different county | 104 (29) | 219 (21) | 60 (13) | 126 (10) | 164 (20) | 345 (15) |

| Non-vaccination hospital visit in last 8–21 days (yes) | 172 (48) | 64 (6) | 201 (43) | 60 (5) | 373 (45) | 124 (5) |

| Type of visit | ||||||

| Outpatient: 8–21 days | 98 (27) | 53 (5) | 78 (17) | 50 (4) | 176 (21) | 103 (5) |

| Inpatient: 8–21 days | 74 (21) | 11 (1) | 123 (26) | 10 (1) | 197 (24) | 21 (1) |

| No visit | 185 (52) | 973 (94) | 264 (57) | 1182 (95) | 449 (55) | 2155 (95) |

Note: Discrepancies between sum of cases or controls listed for a variable and the total number of cases or controls reflect unknown or missing data, which were ≤2% for each variable and therefore omitted from this table. Exception: Data for “received all eligible doses” is missing in 11% of cases and 9% of controls.

Case-patients were more frequently male and older (median age: 6 months, IQR: 5–7 months) than controls (median age: 5 months, IQR: 3–6 months) (Table 1). The sex distribution and median age of case-patients was similar between the eastern and central/western regions. Although ≥97% of case-patients and controls in both regions reported possession of a vaccination card, cases were less frequently up-to-date with all recommended vaccines (57% vs. 84%). Case-patients and controls has similar rates of visit to a hospital or clinic for any reason at least once in the 8–21 days before rash onset or interview, 58% and 46%, respectively (data not shown). However, 45% of case-patients compared with only 5% of controls reported at least one visit to a hospital or clinic for a reason other than vaccination 8–21 days before rash onset or date of interview (Table 1). Reason for visits included fever and cough (37% case-patients; 3% controls), other illness (10% case-patients, 2% controls) and other non-illness visits (4% case-patients,1% controls). Visits were further classified as inpatient (24% case-patients, 1% controls) and non-inpatient (21% case-patients, 5% controls). Case-patients and controls in the eastern region more frequently reported a history of changing residence or family migration (county, prefecture, and province), parental education beyond primary school, having one or no siblings, and residence in a multistory building than case-patients and controls from the central/western regions (Table 1).

From univariate conditional logistic models, case-patients were more likely than controls to have visited the hospital for a reason other than vaccination in the 8–21 days before rash onset or investigation date. This was true for all case-patients as well when stratified by eastern and central/western regions (Table 2). Both inpatient hospitalization and outpatient hospital visits were significantly associated with being a case-patient overall and in each region. A personal history of changing residences was associated with being a case-patient in both regions. Additional risk factors for both regions included male sex, age 5–7 months, and missing vaccine doses for other antigens (Table 2). In multivariable analysis, male sex (mOR 1.6 [1.3, 2.0]), age 5–7 months (mOR 3.9 [3.0, 5.1]), migration between counties (mOR 2.3 [1.6, 3.4]), outpatient hospital visits (mOR 9.4 [6.6, 13.3]) and inpatient hospitalization (mOR 107.1 [48.8, 235.1]) remained significant risk factors. The calculated attributable fractions of measles cases for any non-vaccine hospital visit was 43.1% (95% CI: 40.1, 47.5) adjusted for age, sex and migrating from a different county. The AF for inpatient visits was 23.8% (95% CI: 21.0, 27.4) and for outpatient was 19.2% (95% CI: 16.6, 22.8).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with measles in children aged 0–7 months stratified by geographic area, matched case–control study–China, 2012–2013.

| Variable description | East |

Central/west |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of matched setsa | mOR (95%CI) | Number of matched sets | mOR (95%CI) | Number of matched sets | mOR (95% CI) | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Sex (male:female) | 360 | 1.7(1.3,2.3) | 470 | 1.6(1.3,2.0) | 830 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.0) |

| Age group (5–7 months:0–4 months) | 360 | 4.1(3.0,5.8) | 470 | 3.6(2.8,4.7) | 830 | 3.8 (3.1, 4.7) |

| Vaccination card (yes:no) | 360 | 0.8(0.2,2.6) | 469 | 1.6(0.7,3.7) | 829 | 1.3 (0.6, 2.6) |

| Received all eligible doses (no:yes) | 335 | 4.3(3.2,5.9) | 387 | 4.9(3.6,6.7) | 722 | 4.6 (3.7, 5.7) |

| Mother’s education | 355 | 464 | 819 | |||

| ≤Primary:college+ | 2.0(1.0,4.0) | 1.4(0.7,2.6) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) | |||

| Middle:college+ | 1.8(1.1,2.9) | 1.2(0.7,2.2) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.3) | |||

| Father’s education | 356 | 465 | 821 | |||

| ≤Primary:college+ | 2.0(0.9,4.2) | 1.7(0.9,3.1) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) | |||

| Middle:college+ | 1.2(0.8,1.8) | 1.2(0.7,2.1) | 1.2(0.9, 1.7) | |||

| Type of house | 359 | 465 | 824 | |||

| Multistory:single story | 1.5(0.9,2.4) | 1.0(0.7,1.5) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | |||

| Other:single story | 9.7(2.4,38.4) | 1.0(0.4,2.4) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | |||

| Any siblings (yes:no) | 358 | 1.0(0.8,1.4) | 469 | 1.1(0.9,1.4) | 827 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) |

| Care taker (parents:other) | 358 | 1.6(1.0,2.4) | 468 | 1.1(0.7,1.7) | 826 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) |

| Migration history | ||||||

| History of migration in child (yes:no) | 360 | 2.5(1.6,4.0) | 463 | 3.5(2.0,6.1) | 823 | 2.9 (2.0, 4.1) |

| Family migration between provinces (yes:no) | 359 | 1.9(1.2,3.0) | 469 | 0.7(0.3,1.4) | 828 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) |

| Family migration between prefectures (yes:no) | 359 | 2.3(1.5,3.5) | 469 | 1.3(0.8,2.2) | 828 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) |

| Family migration between counties (yes:no) | 359 | 2.5(1.6,3.8) | 469 | 1.5(0.9,2.4) | 828 | 2.0 (1.5, 2.7) |

| Hospital exposure (non-vaccination visit) | ||||||

| Hospital visit in last 8–21 days (yes:no) | 57 | 16.6(10.9, 25.1) | 465 | 21.3(13.8, 32.8) | 822 | 18.8 (13.9, 25.3) |

| Type of visit in last 8–21 days | ||||||

| Outpatient visit: no Visit | 357 | 10.7(6.8, 16.8) | 465 | 8.6(5.4, 13.9) | 822 | 9.7 (6.9, 13.4) |

| Inpatient visit: no visit | 357 | 52.8(20.9, 134) | 465 | 207 (50.7, 848) | 822 | 97.7 (45.4, 210) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; mOR, matched odds ratio.

Matched sets is the number of cases with at least one matched control.

We calculated vaccination coverage among age eligible subsets for each dose of HBV, DPT, and OPV. Ignoring the matched design, the first dose vaccination coverage was similar between case-patients and controls; however coverage was lower for second and third dose coverage among case-patients for all antigens (Table 3). 1813 missed vaccinations doses among cases and controls, 1660 (91.6%) caregivers reported a reason for the missed dose. Most commonly, parents incorrectly believed that the child was too young for vaccination or reported contraindication to vaccination; together, these causes were responsible for 56–66% of all missed vaccination opportunities.

Table 3.

Routine immunization coverage of HBV, DTP, OPV among children aged 0–7 months, matched case–control study—China, 2012–2013.

| Vaccine dosage | Age range for dose eligible (months) | Eastern region number (% vaccinated) |

Central/west region number (% vaccinated) |

Total number (% vaccinated) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | Case | Control | ||

| HBV1 | 1–7 | 350 (99) | 1030 (100) | 455 (98) | 1213 (99) | 805 (98) | 2243 (99) |

| HBV2 | 2–7 | 345 (98) | 959 (99) | 431 (96) | 1085 (98) | 776 (97) | 2044 (98) |

| HBV3 | 7 | 68 (61) | 178 (88) | 65 (56) | 156 (85) | 133 (59) | 334 (86) |

| DTP1 | 4–7 | 306 (92) | 731 (98) | 355 (89) | 754 (97) | 661 (91) | 1485 (97) |

| DTP2 | 5–7 | 237 (83) | 560 (94) | 263 (81) | 544 (92) | 500 (82) | 1104 (93) |

| DTP3 | 6–7 | 141 (66) | 320 (81) | 156 (65) | 314 (80) | 297 (66) | 634 (80) |

| OPV1 | 3–7 | 323 (94) | 848 (97) | 413 (95) | 933 (97) | 736 (95) | 1781 (97) |

| OPV2 | 4–7 | 294 (89) | 707 (95) | 339 (87) | 730 (95) | 633 (88) | 1437 (95) |

| OPV3 | 5–7 | 219 (77) | 526 (90) | 230 (74) | 503 (89) | 449 (75) | 1029 (89) |

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B vaccine; DTP, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine; OPV, oral polio vaccine.

4. Discussion

In our study, hospital exposure was the primary risk factor for measles infection in infants under vaccination age. The combined attributable fraction of 43% for inpatient and outpatient hospital visits suggests that up to two in every five measles cases in pre-vaccination age children in China could be caused by nosocomial exposure. Recent careful outbreak investigations in China have demonstrated hospital exposure in up to 58% of case-patients aged <1 year [22] and have documented infusion rooms, inpatient wards, and waiting areas [22–25], as likely sites of disease acquisition, efficient locations for measles transmission as they are enclosed and frequently crowded [26–28].

A recent review of nosocomial measles transmission worldwide highlighted increasing reports of hospital transmission in the past decade, especially among young adults and infants in countries nearing measles elimination [29]. Several factors make measles easily transmissible in hospital settings. Measles is extremely contagious with reported basic reproductive numbers from 6.2 to 15 [30], and is most transmissible in the early stage. Before the onset of rash, measles is not easily distinguished from other febrile respiratory illnesses. The respiratory symptoms facilitate production of infectious droplets, which can remain aerosolized for several hours [31,32]. As measles incidence falls, clinicians are less familiar with the disease manifestations and diagnosis is frequently delayed or missed altogether. Studies of hospitalized measles patients have documented correct initial diagnosis rates of <20% [33], and prompt initiation of airborne isolation in <10% during the contagious phase [34]. Strict adherence to appropriate precautions for all patients with respiratory symptoms would not only decrease the likelihood of measles transmission but also reduce the risk for nosocomial spread of tuberculosis, influenza, and other pathogens spread via airborne route. A recent study in Inner Mongolia demonstrated that 68% of healthcare workers (HCWs) were positive for latent tuberculosis, among the highest reported prevalence worldwide, suggesting widespread nosocomial transmission [35]. Studies from other countries have documented that HCWs have an up to 19-fold increased risk for acquiring measles when compared with the general public [36,37]. Because they might transmit disease to patients, HCWs should either have documented protection against measles or be vaccinated before starting work. Hospitals should maintain up-to-date records of the protection status of all HCWs at their facilities in a readily accessible and searchable format [29]. These steps would help reduce the risk for nosocomial outbreaks and protect vulnerable populations such as infants from measles infection.

In line with the national surveillance data [11], cases in our study most frequently occurred in children aged 5–7 months. We observed very few cases in 0–2 month-old infants and cases steadily increased with age, consistent with the youngest infants being protected from infection by maternal antibodies. This correlates with previous sero-epidemiological studies of measles antibodies in China, which demonstrated decreasing seropositivity rates from >70% in <1 month-old-infants to as low as 0–19% at 6 months [38–41]. As the majority of Chinese infants are susceptible to measles before becoming eligible for MCV1 [42], these infants must be protected by optimizing strategies to maintain sufficient herd immunity. Children should therefore receive the first dose of MCV as soon as they are eligible. Since infants of mothers with vaccine-induced immunity lose passive immunity to measles approximately 3 months earlier than infants of mothers with immunity acquired via measles disease [43], vaccination of infants as young as 6 months old can be considered in outbreak settings when a large proportion of cases occur in children under 8 months of age or the attack rate for children <8 months is high [43,44]. Because of lower vaccine efficacy at this age, these children should be re-vaccinated as soon as possible after age 8 months [44].

Children who were not up-to-date with other immunizations were at increased risk for measles infection, despite not yet being eligible for measles vaccination. This was true despite case-patients and controls having generally similar demographics, apart from case-patients being slightly older than controls. Why children who have not received other vaccines would be at risk for measles infection is unclear from our data, but it might suggest that there is a subset of children who are both at increased risk of not receiving timely vaccination and of being exposed to measles virus. These children might have increased exposure to older children who have not been vaccinated against measles or have increased exposure to healthcare settings where they miss vaccination opportunities and are at elevated risk for measles infection. For immunization programs, this finding might present an opportunity to identify early a cohort of children at increased risk for measles acquisition. Defaulter tracking of children in immunization clinics could allow this high-risk group to be targeted for close follow-up to ensure that timely measles vaccination is accomplished. The most frequent reason for missed vaccination was lack of knowledge about the appropriate age for vaccination. This suggests that increased parental education on the importance of timely vaccination and the recommended vaccination schedule is needed.

Our study has several limitations. The case-based measles reporting system in the six provinces, like all surveillance systems, undoubtedly misses cases because of incomplete reporting from community health systems—although the non-measles discard rate is as high as 4 per 100,000 population, which may affect the representativeness of included case-patients. Despite a deliberate attempt to select provinces with a range of demographic and epidemiological characteristics, findings from this study might not apply to all regions in China. However, the similarity of results between study regions suggests nosocomial measles transmission is likely an important risk factor for measles among infants aged <8 months in many areas of China. The exclusion of controls with fever and rash from the study could bias the study toward increasing the association between previous hospital exposure and measles infection, because these potential controls would presumably be more likely to have visited a hospital previously but would be excluded from our study. Available data indicate that exclusions due to fever and rash were few and would therefore be unlikely to significantly alter the strong association between hospital exposure and measles infection among infants. Parents of measles case-patients might be more likely to recall hospital visits because of heightened awareness of events preceding the illness, but interviewers, carefully trained before administering the interview, asked detailed standard questions to elicit hospital exposure history similarly for both case-patients and controls. Neighboring matching of cases with controls, utilized to reduce the risk of differential exposure to measles virus given the low level of recent disease transmission in China, limits the ability to look at residence as a risk-factor for infection. This also likely lead to an underestimation of the association between migration status and infection, as recent migrants in eastern China tend to predominately cluster in certain neighborhoods.

Protecting children too young for measles vaccination depends on maintaining sufficient herd immunity and insulating infants from possible exposure. Enhancing hospital infection control practices in China is necessary to decrease the risk for measles transmission among this vulnerable group. Additional educational programs for healthcare workers on infection control to raise awareness of the risk for nosocomial disease transmission to both patients and staff are required. Ill children should be physically separated as much as possible from well children in hospitals to reduce the risk for exposure. Fever and rash cases should be isolated promptly, preferably in negative-pressure rooms if hospitalized, and hospitalization of suspected measles patients should be limited to those with serious complications. Increased collaboration between the immunization and infection control programs at all levels in China is needed to implement measures to prevent measles transmission in hospitals and accelerate progress toward measles elimination in China.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at county, prefecture, and province level Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in China for their assistance with this investigation. We also acknowledge Susan Y. Chu, Robert Linkins, and Stephen L. Cochi at the Global Immunization Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for their support of this project.

Funding to support the activities described in this article came from Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Global Immunization Division, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Disclaimers: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources are for identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Public Health Service or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- [1].WHO. Global control and regional elimination of measles, 2000–2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014;89:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].WHO. Progress towards measles elimination in the Western Pacific Region, 2009–2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013;88:233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhang Y, Xu S, Wang H, Zhu Z, Ji Y, Liu C, et al. Single endemic genotype of measles virus continuously circulating in China for at least 16 years. PLoS One 2012;7:e34401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].MOH. National plan of measles elimination in China 2006–2012; 2006. http://www.moh.gov.cn/jkj/s3581/200804/361e2acfadcc4e93bcac60235d307a48.shtml.

- [5].Castillo-Solorzano CC, Matus CR, Flannery B, Marsigli C, Tambini G, Andrus JK. The Americas: paving the road toward global measles eradication. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 1):S270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ma C, An Z, Hao L, Cairns KL, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. Progress toward measles elimination in the People’s Republic of China, 2000–2009. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 1):S447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jing M, Luo H, Lixin H, Chao M, Ning W, Chunxiang F, et al. Evaluation on implementation of measles supplementary immunization activities in 13 provinces of China in 2009. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2010;16:481–4. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chao M, Lixin H, Jing M, Yan Z, Lei C, Xiaofeng L, et al. Measles epidemiological characteristics and progress of measles elimination in China, 2010. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2011;17:242–5. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ma C, Hao L, Zhang Y, Su Q, Rodewald L, An Z, et al. Monitoring progress towards the elimination of measles in China: epidemiological observations, implications and next steps. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:340–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhi-wei Y, Xing-lu Z, Jian Z, Gong-huan Y, Guang Z, Ke-an W. An analysis of current measles epidemiological situation in China. Chin J Vaccin Immun 1998;4:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chao M, Qi-ru S, Li-xin H, Ning W, Chun-xiang F, Lei C, et al. Measles epidemiology characteristics and progress toward measles elimination in China, 2012–2013. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2014;20:193–9. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chao M, Lixin H, Qi-ru S, Chao M, Yan Z, Lei C, et al. Measles epidemiology and progress towards measles elimination in China, 2011. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2012;18:193–9. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lixin H, Chao M, Jing M, Zhijie A, Huiming L, Xiaofeng L. Analysis on epidemiological characteristics of measles in China from 2008–2009. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2010;16:293–6. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chao M, Huiming L, Zhijie A, Ping Z, Ning W, Wei X, et al. Analysis on epidemiological characteristics and measures of measles control in China during 2006–2007. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2008;14:208–13. [Google Scholar]

- [15].The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The seventh five year plan; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [16].China statistical yearbook. Beijing: China: Statistics Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dupont WD. Power calculations for matched case–control studies. Biometrics 1988;44:1157–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chao M, Lixin H, Zhijie A, Jing M, Yan Z, Wenbo X, et al. Establishment and performance of measles surveillance system in the People’s Republic of China. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2010;16:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- [20].WHO. Monitoring progress towards measles elimination. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2010;85:490–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Llorca J, Delgado-Rodriguez M. A comparison of several procedures to estimate the confidence interval for attributable risk in case–control studies. Stat Med 2000;19:1089–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jiang-wen Q, Zhi-gang G, Ya-xing D, Li-xia W, Xiao-yan L, Ying Z. Analysis on characteristic and reasons of measles high incidence in Tianjin municipal, 2010. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2013;19:35–8. [Google Scholar]

- [23].En-fu C, Han-qing H, Qian L, Rui M, Feng-ying W, Chun-hua Q. Case–control study on epidemiology factors of measles in Zhejiang Province in 2008. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2010;16:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li W-G, Xu H, Zhu Q-F, Jia L. Epidemiological investigation on an outbreak of 4 cases of measles in a pediatric ward. Chin J Infect Control 2013;12:41–3. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gao J, Chen E, Wang Z, Shen J, He H, Ma H, et al. Epidemic of measles following the nationwide mass immunization campaign. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Marshall TM, Hlatswayo D, Schoub B. Nosocomial outbreaks—a potential threat to the elimination of measles? J Infect Dis 2003;187(Suppl. 1):S97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Biron C, Beaudoux O, Ponge A, Briend-Godet V, Corne F, Tripodi D, et al. [Measles in the Nantes Teaching Hospital during the 2008–2009 epidemic]. Med Mal Infect 2011;41:415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Beggs CB, Shepherd SJ, Kerr KG. Potential for airborne transmission of infection in the waiting areas of healthcare premises: stochastic analysis using a Monte Carlo model. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Botelho-Nevers E, Gautret P, Biellik R, Brouqui P. Nosocomial transmission of measles: an updated review. Vaccine 2012;30:3996–4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mossong J, Muller CP. Estimation of the basic reproduction number of measles during an outbreak in a partially vaccinated population. Epidemiol Infect 2000;124:273–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bloch AB, Orenstein WA, Ewing WM, Spain WH, Mallison GF, Herrmann KL, et al. Measles outbreak in a pediatric practice: airborne transmission in an office setting. Pediatrics 1985;75:676–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Remington PL, Hall WN, Davis IH, Herald A, Gunn RA. Airborne transmission of measles in a physician’s office. JAMA 1985;253:1574–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Davidson N, Andrews R, Riddell M, Leydon J, Lynch P. A measles outbreak among young adults in Victoria, February 2001. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2002;26:273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen SY, Anderson S, Kutty PK, Lugo F, McDonald M, Rota PA, et al. Health care-associated measles outbreak in the United States after an importation: challenges and economic impact. J Infect Dis 2011;203:1517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].He GX, Wang LX, Chai SJ, Klena JD, Cheng SM, Ren YL, et al. Risk factors associated with tuberculosis infection among health care workers in Inner Mongolia, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012;16:1485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Atkinson WL, Markowitz LE, Adams NC, Seastrom GR. Transmission of measles in medical settings—United States, 1985–1989. Am J Med 1991;91:320S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Steingart KR, Thomas AR, Dykewicz CA, Redd SC. Transmission of measles virus in healthcare settings during a communitywide outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20:115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lian-jun W, Chao C, Jian-hui Z, Jing W, Gui-yan L. The study of the best immunization time of measles vaccine for newborns. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2001;7:10–1. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rui M, Guozhang X, Hong-jie X, Yan-hui M, Hong-jun D, Yan L. Study on Changing of maternal transferred measles antibody level in infants. Chin J Vaccin Immun 2008;14:226–8. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yan-tian W, Jian-guang H, Lan-xiang D, Wen L, Yun-qing X. Study on the relationship between maternal measles antibody and the incidence of infant measles. Chin Prev Med 2012;13:357–60. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liu X-L, Wang Y-J, Cao L, Li Y-L, Chen X-N. Surveillance of measles antibody levels of maternal women and infants in Tongchuan of Shaanxi. Mod Prev Med 2014;41:437–9. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Leuridan E, Sabbe M, Van Damme P. Measles outbreak in Europe: susceptibility of infants too young to be immunized. Vaccine 2012;30:5905–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].WHO. Meeting of the strategic advisory group of experts on immunization, October 2015—conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2015;90:681–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].WHO. Response to measles outbreaks in measles mortality reduction settings; 2009. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO-IVB-09.03-eng.pdf?ua=1 . [PubMed]