Abstract

Orthogonal ribosomes are unnatural ribosomes that are directed towards orthogonal messenger RNAs in Escherichia coli, through an altered version of the 16S ribosomal RNA of the small subunit1. Directed evolution of orthogonal ribosomes has provided access to new ribosomal function, and the evolved orthogonal ribosomes have enabled the encoding of multiple non-canonical amino acids into proteins2–4. The original orthogonal ribosomes shared the pool of 23S ribosomal RNAs, contained in the large subunit, with endogenous ribosomes. Selectively directing a new 23S rRNA to an orthogonal mRNA, by controlling the association between the orthogonal 16S rRNAs and 23S rRNAs, would enable the evolution of new function in the large subunit. Previous work covalently linked orthogonal 16S rRNA and a circularly permuted 23S rRNA to create orthogonal ribosomes with low activity5,6; however, the linked subunits in these ribosomes do not associate specifically with each other, and mediate translation by associating with endogenous subunits. Here we discover engineered orthogonal ‘stapled’ ribosomes (with subunits linked through an optimized RNA staple) with activities comparable to that of the parent orthogonal ribosome; they minimize association with endogenous subunits and mediate translation of orthogonal mRNAs through the association of stapled subunits. We evolve cells with genomically encoded stapled ribosomes as the sole ribosomes, which support cellular growth at similar rates to natural ribosomes. Moreover, we visualize the engineered stapled ribosome structure by cryo-electron microscopy at 3.0 Å, revealing how the staple links the subunits and controls their association. We demonstrate the utility of controlling subunit association by evolving orthogonal stapled ribosomes which efficiently polymerize a sequence of monomers that the natural ribosome is intrinsically unable to translate. Our work provides a foundation for evolving the rRNA of the entire orthogonal ribosome for the encoded cellular synthesis of non-canonical biological polymers7.

The ribosome is a 2.5-megadalton molecular machine, composed of two subunits, that synthesizes proteins using mRNA templates8. Ribosomal translation represents the ultimate paradigm for the encoded, high fidelity synthesis of long polymers of defined sequence and composition7. However, adapting the cellular ribosome to enable the encoded synthesis of non-canonical biopolymers is an outstanding challenge7. The small subunit of the ribosome, containing 16S rRNA, binds to mRNAs and decodes codon-anticodon interactions between the mRNA and transfer RNAs, whereas the large subunit, containing 23S rRNA, facilitates peptide bond formation and co-translational protein folding; both subunits bind translation factors and coordinate translation8. Ribosomes are essential and many mutations in the ribosome are dominant negative or lethal9.

In previous work, we created orthogonal (O-) ribosome-mRNA pairs in E. coli1. In these pairs, an orthogonal message (O-mRNA, containing and O-ribosome binding site), is selectively translated by the O-ribosome (containing O-16S rRNA with mutations in the anti-Shine Dalgarno (ASD) sequence); this O-mRNA cannot, however, be translated by endogenous ribosomes1. The O-ribosome is non-essential, and has been further evolved to enable efficient incorporation of multiple distinct non-canonical amino acids into polypeptides3,4.

The orthogonal and the wild-type ribosomes share a common pool of large subunits. An important goal is the creation of orthogonal ribosomes in which both a new 23S rRNA and the O-16S rRNA are directed towards an orthogonal message7. Such orthogonal ribosomes would maximize the contributions of the new 23S rRNA to translation of an O-mRNA, insulate the effects of otherwise deleterious mutations in the new 23S rRNA from cellular translation, and therefore enable the evolution of new function in the large subunit.

Ribosomal subunits can be covalently linked by joining helix 44 of the 16S rRNA to Helix 101 of a circularly permuted 23S rRNA (Fig. 1) 5,6,10 through either a flexible tether, the A8/9 tether, or the hinge from the J5-J5a region from the Tetrahymena group I self-splicing intron11; the latter strategy created the parental orthogonal ‘stapled’ ribosome (herein called O-d0d0). These O-ribosomes with linked subunits maintain only 30% of the activity of the parental O-ribosome (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 1). Moreover, the exceptionally high concentration of ribosomes in cells (see Supplementary Information) suggests that subunit tethering – without additional features that favour association between the linked subunits and/or restrict association of linked subunits with endogenous subunits – is unlikely to specify the association of linked subunits within an orthogonal ribosome (in cis) over association of the linked subunits with endogenous subunits (in trans) (Fig. 1b). Gain-of-function mutations in the 23S rRNA portion of an O-ribosome with tethered subunits led to a measurable phenotype when using an orthogonal message6. However, statistical partitioning of large subunits between orthogonal and endogenous small subunits can confer gain-of-function phenotypes without specificity in subunit association (Extended Data Fig. 1), and stronger gain-of-function phenotypes have been described with endogenous ribosomes12,13. Orthogonal translation by linked subunits occurs in cells that also contain endogenous ribosomes; here, a different set of subunit associations may occur from those that may occur in cells that contain only ribosomes with covalently linked subunits that are directed to endogenous mRNAs (Fig. 1b,c). Therefore, in contrast to common assumptions, experiments that use ribosomes with linked subunits, directed to endogenous messages, as the sole ribosomes in the cell (Fig. 1c) (which currently require multicopy plasmids for rRNA expression and lead to retarded growth6) do not address the key question of whether orthogonal ribosomes with covalently linked subunits associate with the free subunits of endogenous ribosomes when both types of ribosomes are present in the cell (Fig. 1b). Thus, there is no compelling evidence that the linked subunits within O-ribosomes reported to date specifically associate with each other to mediate translation7, nor is there any evidence that O-ribosomes can be altered to access new large subunit functions that have not been accessed in natural ribosomes.

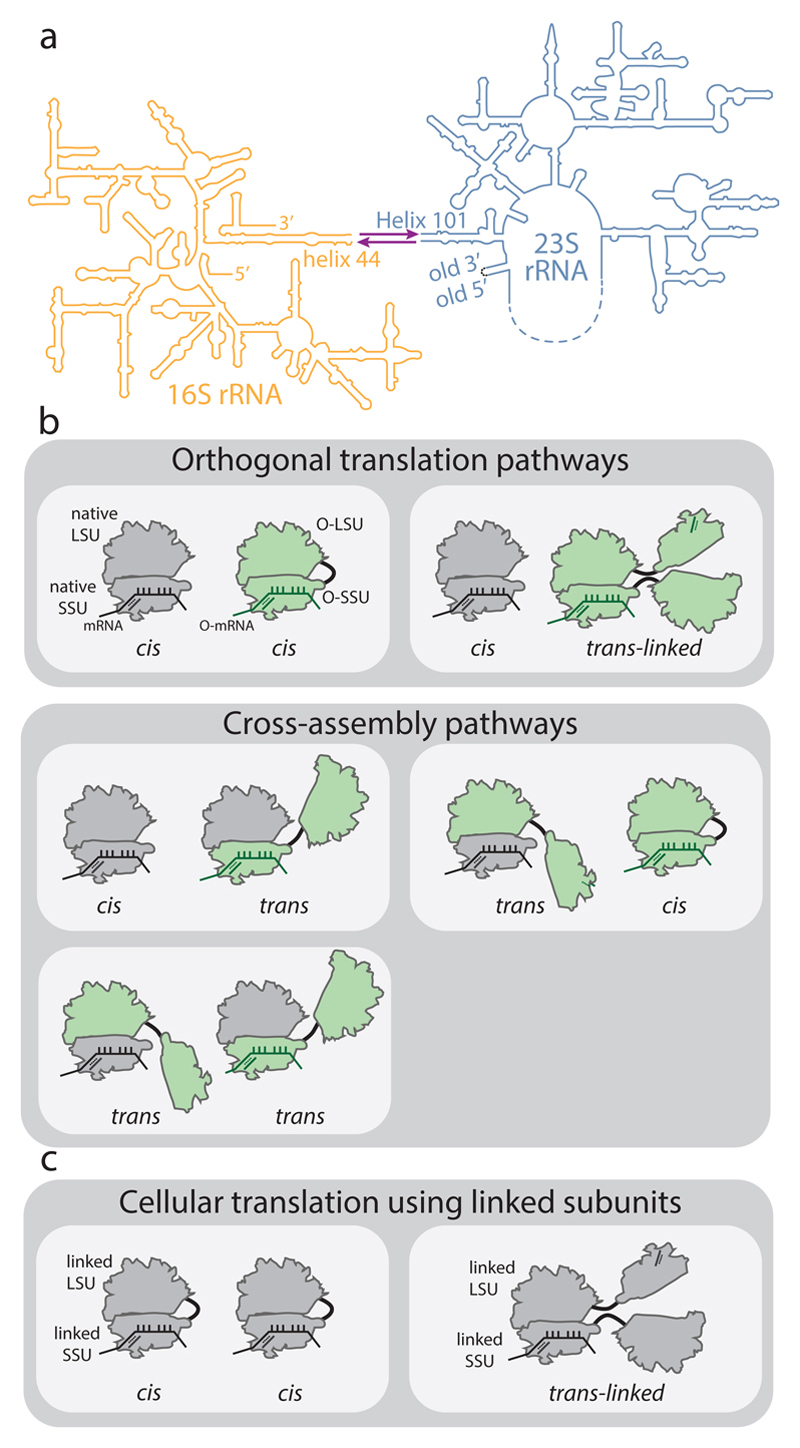

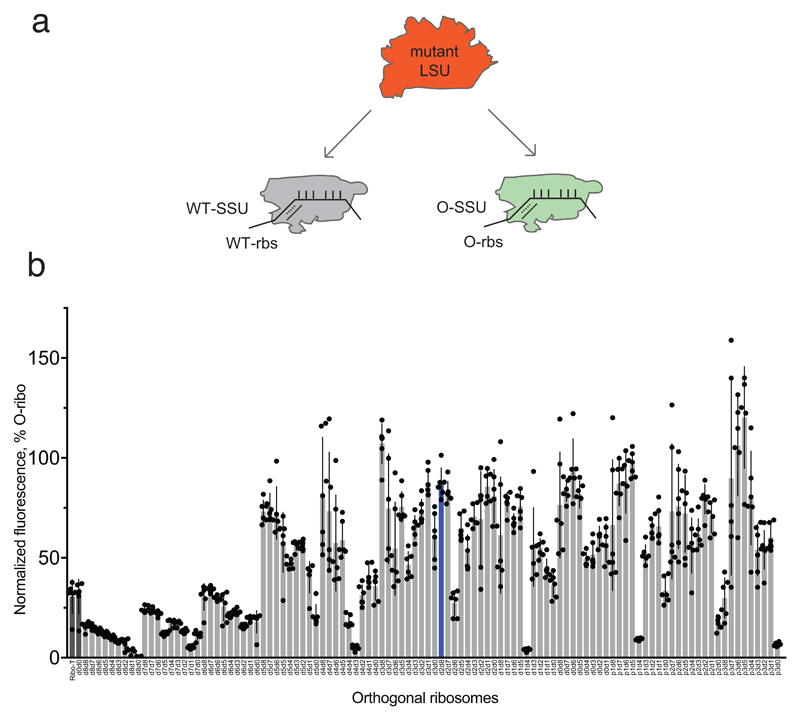

Figure 1. Ribosome stapling and potential interactions of linked subunits in vivo.

a, Secondary structure of RNA from ribosomes with linked subunits. A single rRNA transcript is generated by inserting a circularly permuted 23S rRNA (blue) into a split 16S rRNA (yellow), with the 16S and 23S rRNAs linked together by an RNA linker (purple). In stapled ribosomes the linker is a staple derived from the J5-J5a region of the Tetrahymena group I intron. The original O-stapled ribosome, referred to here as O-d0d0, directly links h44 and H101 through the staple. b, Potential interactions of linked ribosomal subunits in vivo. Cells (white boxes) containing O-ribosomes with linked subunits as well as endogenous (native) subunits may associate to create orthogonal translation pathways or cross-assembly pathways. An orthogonal translation complex is created by directing the association of an orthogonal small ribosome subunit (O-SSU) with its linked large subunit (O-LSU) in cis, or by forming trans-linked complexes. Linked ribosome subunits may interact with native ribosome subunits in trans if the linker is insufficient to direct assembly in cis. High concentrations of native ribosome subunits in the cytoplasm under physiological conditions counteract the effects of tethering and may lead to cross-assembly. c, In E. coli strains containing solely ribosomes with covalently linked subunits, cis- or trans-linked complexes may form.

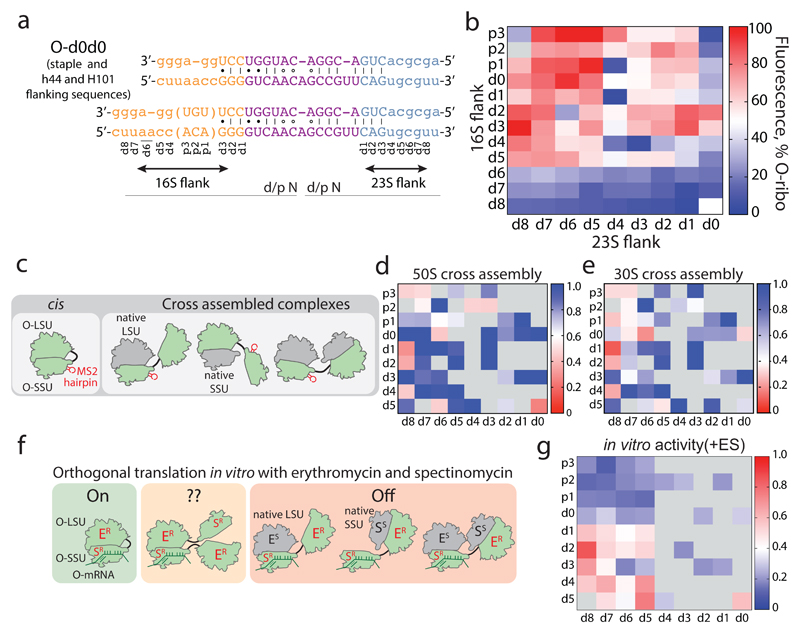

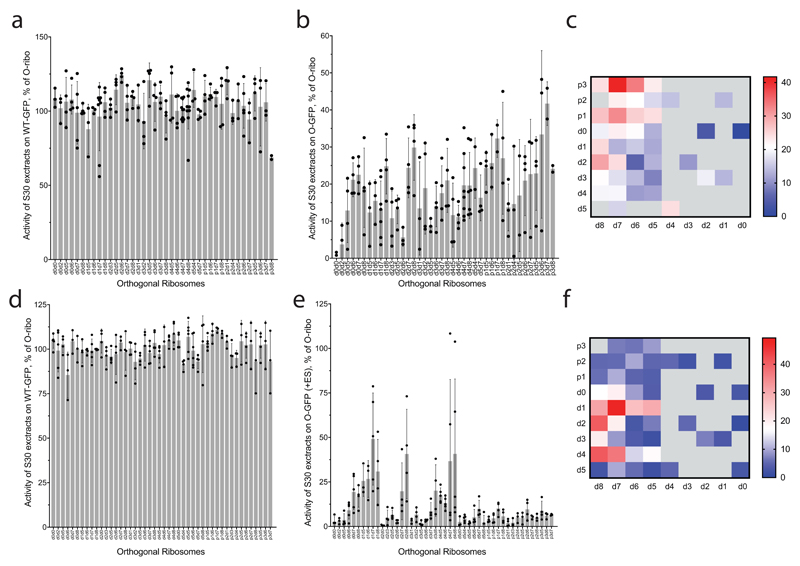

Figure 2. Maximizing activity and minimizing cross-assembly in engineered O-stapled ribosomes via systematic variation of the intersubunit linker.

a, Top two rows, the intersubunit staple sequence (uppercase letters)—composed of a hinge (purple) and native helical flanking residues (yellow and blue)—used in O-d0d0. rRNA-derived sequences are in lowercase letters. Bottom, variants are denoted by the number (N) of base pairs that have been deleted (d) or inserted (p, for ‘plus’) from the 16S side, followed by the number of base pairs deleted from the 23S side. b, Heat map showing O-stapled ribosome activity (as analysed by the synthesis of GFP) in vivo. The resulting GFP fluorescence is shown as a percentage of that produced from an orthogonal ribosome with non-linked subunits. Data are thresholded at 100. See Methods for statistics and Extended Data Fig. 1b for full data. c, Potential complexes between small subunits (SSUs) and large subunits (LSUs) following affinity purification of O-stapled ribosomes (green) with an MS2 stem loop. Native subunits are in grey. d, e Heat map showing 50S (LSU; d) and 30S (SSU; e) cross-assembly coefficients. Variants in grey were not tested. The heat map is thresholded at 1. Data are means of n=2 biological replicates. See Extended Data Fig. 3a,b. f, In vitro translation of the orthogonal message in the presence of the antibiotics erythromycin and spectinomycin (which selectively inhibit native subunits) is denoted ‘on’, ‘off ’ or unknown (‘??’) for each complex upon selective inhibition of native subunits. ER and SR denote erythromycin and spectinomycin resistance; ES and SS denote erythromycin and spectinomycin sensitivity g, Heat map showing the efficiency of translating T7-O-GFP (a construct containing a T7 promoter upstream of an orthogonal ribosome-binding site and an sfGFP gene) in S30 extracts of E. coli; the extracts contained the indicated O-stapled ribosome and native ribosomes. We added 10 μM spectinomycin and 50 μM erythromycin (ES) to the extract to inhibit native subunits. The heat map shows the mean fluorescence. For values of n and errors, see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 6.

Here we identify engineered O-stapled ribosomes that minimize association with endogenous ribosomal subunits and maximize their activity through stapled subunit association. In an evolved strain of E.coli, the engineered stapled ribosome supports robust cell growth as the sole, genomically encoded, ribosome, with growth rates comparable to those conferred by wild-type ribosomes. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) reveals how the staple covalently links ribosome subunits to control their association, and we evolve engineered O-stapled ribosomes with new intrinsic polymerization function.

We envisioned that both the activity of the O-stapled ribosome directed to an orthogonal message, and the contributions to that activity from orthogonal translation pathways versus cross assembly pathways (Fig. 1b,c), may vary as a function of the length of the helices in each subunit that link to the J5-J5a hinge (Fig. 2a). We created a matrix of 107 O-rDNAs (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 1) that systematically combines deletions or insertions in helix 44 with deletions in Helix 101 in the O-stapled ribosome; these alterations are expected to both translocate and rotate one subunit with respect to another. We named the linker variants by the number of base pairs that were deleted (d) or added (p, for ‘plus’) to helix 44 followed by the number of base pairs that have been deleted from Helix 101 with respect to O-d0d0 (Fig. 2a). We found that removing up to five nucleotides of helix 44 in O-16S rRNA leads to more active ribosomes, and that shortening Helix 101 of the 23S rRNA in the O-stapled ribosome is commonly associated with a gradual increase in activity. Indeed, some of the new O-stapled ribosomes are substantially more active than the first-generation O-ribosomes with linked subunits, and approach the activity of the non-stapled O-ribosome.

We next investigated the cross assembly of O-stapled ribosomes and endogenous subunits (Fig. 1b) by affinity purifying O-stapled ribosomes tagged with the RNA stem loop from the MS2 bacteriophage (refs.14,15) from cells and measuring the co-purification of endogenous subunits (Fig. 2c-e, Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 2). We defined the molar ratios of 50S and 30S rRNA to MS2-tagged stapled O-rRNA from the purification as the 30S and 50S cross assembly coefficients, respectively. We found that different O-stapled ribosomes associate with endogenous ribosomal subunits to substantially different extents (Fig. 2c-e and Extended Data Fig. 3). Previously described O-ribosomes with linked subunits have cross-assembly coefficients close to one, demonstrating that they interact extensively and stably with endogenous ribosome subunits in trans. By contrast, O-d2d8 has substantially reduced cross-assembly coefficients (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3).

Next we compared the relative activity of different O-stapled ribosomes, resulting solely from linked subunits acting in cis- or trans-linked complexes (Fig. 1b), in the presence of endogenous subunits. We achieved this by first developing an in vitro orthogonal translation system (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 3) in which we could selectively inhibit translational contributions from wild-type subunits by adding the antibiotics spectinomycin and erythromycin; we used stapled subunits that contain mutations conferring resistance to these antibiotics16,17 (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 4). Several O-stapled ribosomes that translate an O-mRNA in the presence of functional endogenous subunits could not support robust translation when the endogenous subunits were inactivated (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 6); these ribosomes presumably mediate translation via trans interactions with endogenous subunits. By contrast, other O-stapled ribosomes – notably O-d2d8 – exhibit substantial activity when the translational capacity of endogenous subunits is inhibited (Fig. 2g), and can mediate robust translation using only O-stapled ribosome subunits.

Taken together our data suggests that the highly active translation of O-mRNAs by O-d2d8 may be mediated primarily by the association of subunits within the O-stapled ribosome, and indicate that the connection between the J5-J5a RNA hinge and the two subunits in the d2d8 linker has an optimum geometry for specifying intramolecular subunit association.

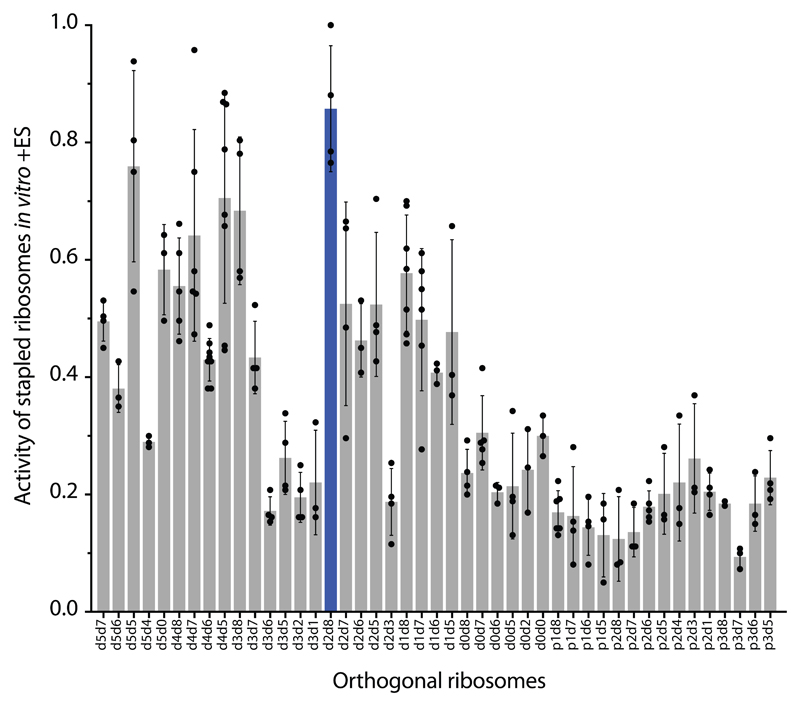

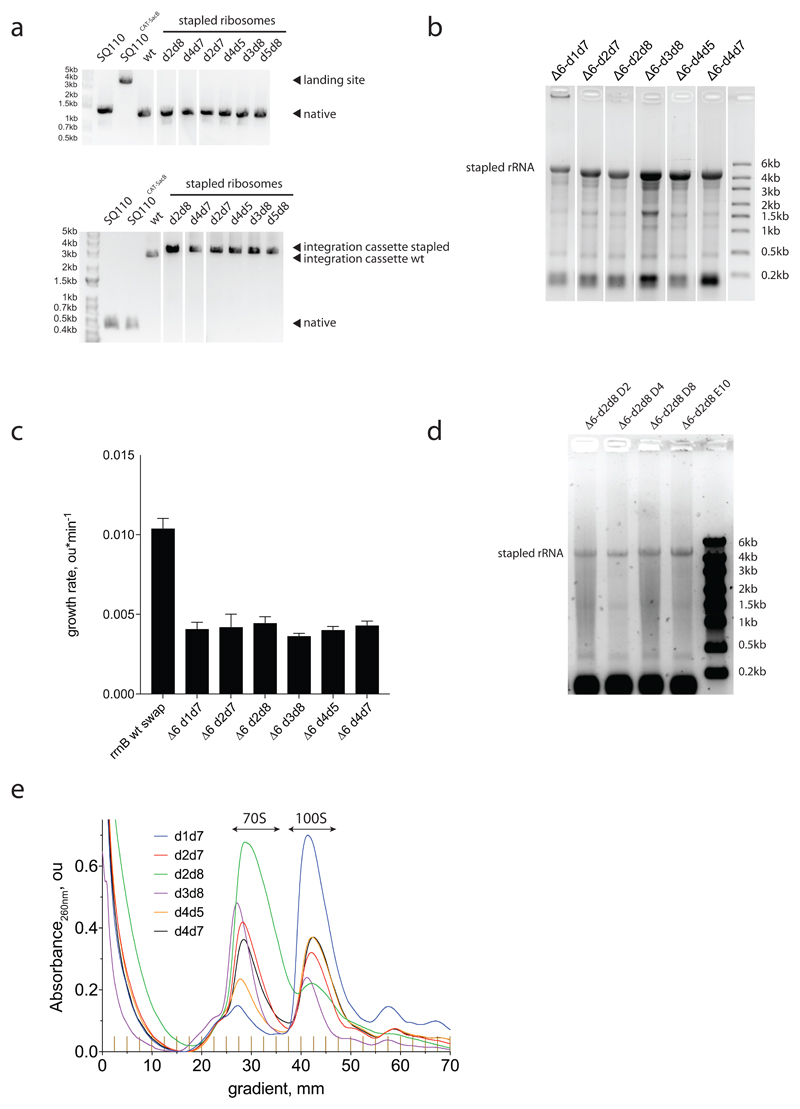

We used a variant of replicon excision enhanced recombination (REXER18; Fig. 3a) to create bacterial strains that use genomically encoded stapled ribosomes with a wild-type ASD as the sole ribosome in the cell19 (Extended Data Fig. 7). Sucrose gradient analyses of the resulting strains suggests that, in some strains, trans-linked stapled ribosome complexes dominate and probably support growth (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 7e). The strain containing the d2d8 stapled ribosome (Δ6 d2d8), however, forms minimal trans-linked complexes (Fig. 3b), and the growth rate of the strain is 30-40% of wild-type controls (Extended Data Fig. 7d).

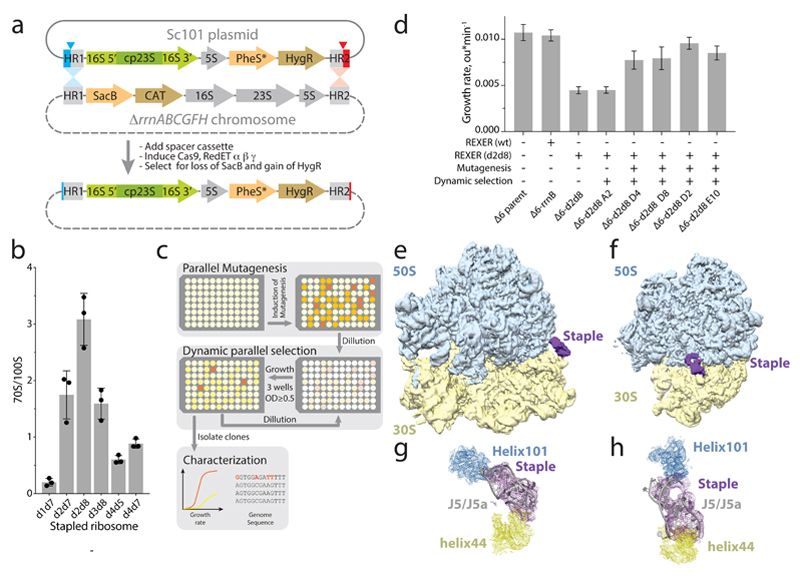

Figure 3. Genomically encoding stapled ribosomes as the sole cellular ribosomes, and subsequent strain evolution, generates fast-growing E.coli for d2d8 purification and structure determination.

a, Schematic showing how ribo-REXER is used for the genomic replacement of ribosomal RNA operons, applied here to generate Δ6d2d8. The SC101 plasmid contains the rRNA for the stapled ribosome; this rRNA is used to replace the single rRNA in the chromosome of a ΔrrnABCGFH strain of E. coli. SacB, Bacillus subtilus levansucrase gene; CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; cp, circularly permuted; HR, homologous regions; HygR, hygromycin-resistance gene; PheS*, T251A A294G mutant of E. coli phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase. Red and blue arrows indicate sites of Cas9-mediated cleavage. b, Ratio of monosomes (70S) to ribosome dimers (100S) from sucrose gradient analyses of different stapled ribosomes isolated from cells under associating conditions. Shown are individual data points (black dots), means (grey bars) and standard deviations from three biological replicates. c, Evolution of Δ6 d2d8 by automated parallel evolution. Clonal cultures are shown in pale yellow; mutagenized populations in each well are represented by distinct shades. Dynamic parallel selection was repeated for ten cycles before clone isolation and genome characterization. OD indicates the optical density at 600 nm. In the dynamic parallel selection, the dilution of cells was triggered once the OD600 of three wells was greater than or equal to 0.5. d, Characterization of the specific growth rates of Δ6 d2d8 (resulting from ribo-REXER), as well as passaged passaged (A2) and evolved (D4, D8, D2, E10) strains. rrnB is an rRNA operon For statistics, see Methods. e, Electron-density map for E.coli d2d8 70S ribosome. f, A rotated view of the electron-density map shown in e, g. A close up of the density (purple mesh) connecting Helix 101 and helix 44. The J5-J5a RNA (Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession code 1GID; grey) is docked into the density for the staple. The orientation shown is comparable to that in e. h, Similar to g, but shown in a comparable orientation to f.

We developed an automated parallel evolution method (Fig. 3c) and used it to select faster-growing strains derived from the Δ6 d2d8 strain; these strains facilitated isolation of d2d8 ribosomes for structural studies. Following strain evolution, we isolated individual clones from the four fastest growing cultures to analyse in detail. The specific growth rates of the evolved strains were approximately 81% of those of controls with wild-type ribosome (Fig. 3d). Whole-genome sequencing of independently evolved strains provided further insight into the mutations associated with their improvement (Supplementary Data 5-11). We note that our approach provides a rapid and reproducible route to cellular evolution (with the entire process taking just two to three weeks).

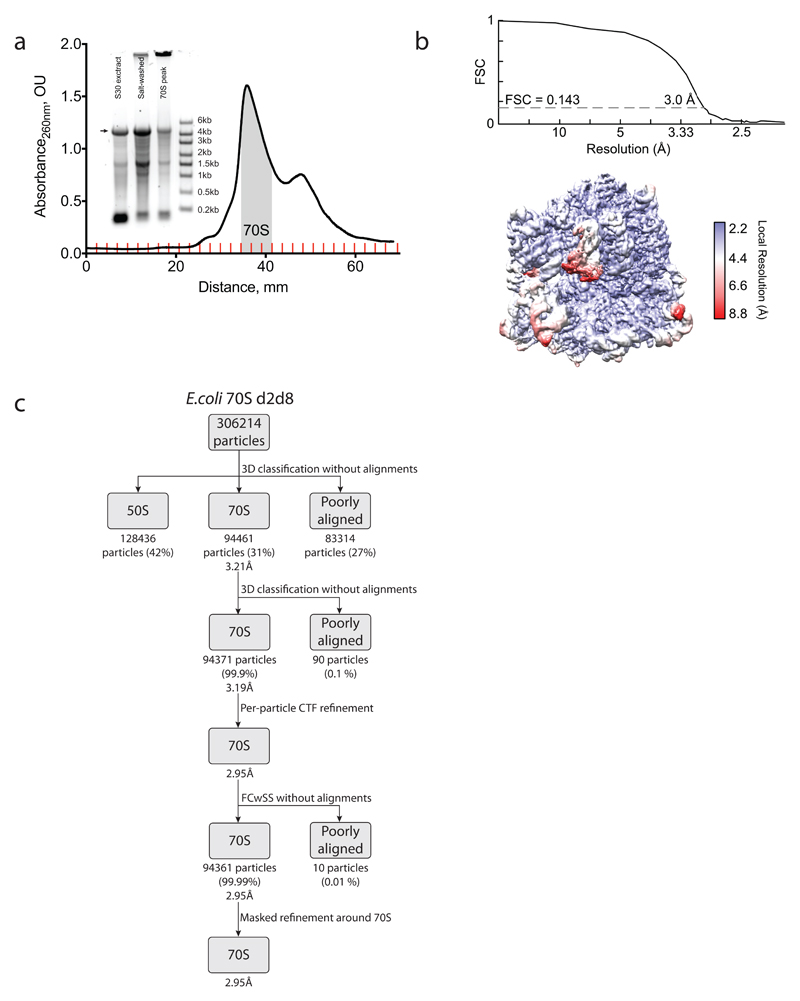

To reveal how the staple connects the ribosome subunits of d2d8 to mediate their selective association, we prepared d2d8 70S ribosomes from Δ6 d2d8-E10 E. coli (Extended Data Fig. 8a) and visualized the stapled ribosome structure by single particle cryo-EM, at an overall resolution of 3.0Å (Fig. 3e,f, Extended Data Fig. 8b,c and Extended Data Table 1). The structure clearly reveals the two subunits of the ribosome in a canonical conformation, with protein and RNA components in the same positions as in previous structures of native ribosomes20. Notably, the two subunits are linked by continuous electron density between helix 44 in the small subunit and Helix 101 in the large subunit (Fig. 3e-h). A previously solved structure of the J5-J5a RNA hinge11 was docked easily into this density (Fig. 3g,h); this is consistent with the hinge adopting a broadly similar structure, when stapling ribosome subunits, as in its native context. The structure reveals how the rational union of RNA modules and combinatorial optimization can be used to engineer a megadalton-sized molecular machine with new properties.

To explicitly demonstrate the advantages of controlling subunit association in the O-stapled ribosome, we evolved the large subunit of O-d2d8 to access a function that has not been accessed in the native ribosome – the intrinsic ability to polymerize a polyproline sequence. The natural ribosome, which is intrinsically able to translate the other 19 amino acids, commonly fails on polyproline (poly(P)) sequences.

The challenge of translating polyproline sequences arises from poor accommodation of the prolyl-tRNA, the retarded rate of peptide bond formation at proline residues, and clashes between the nascent polyproline chain and the exit tunnel (notably residue G2061)21–23. Nature addresses this challenge by augmenting translation with elongation factor P (EF-P) 24,25, which binds to the E-site of ribosomes and stabilizes and positions the peptidyl-tRNA to favour both the formation of peptide bonds between proline residues and the elongation of polyproline sequences. We investigated whether we could evolve O-stapled ribosomes that are intrinsically able to translate proline-rich sequences in the absence of EF-P.

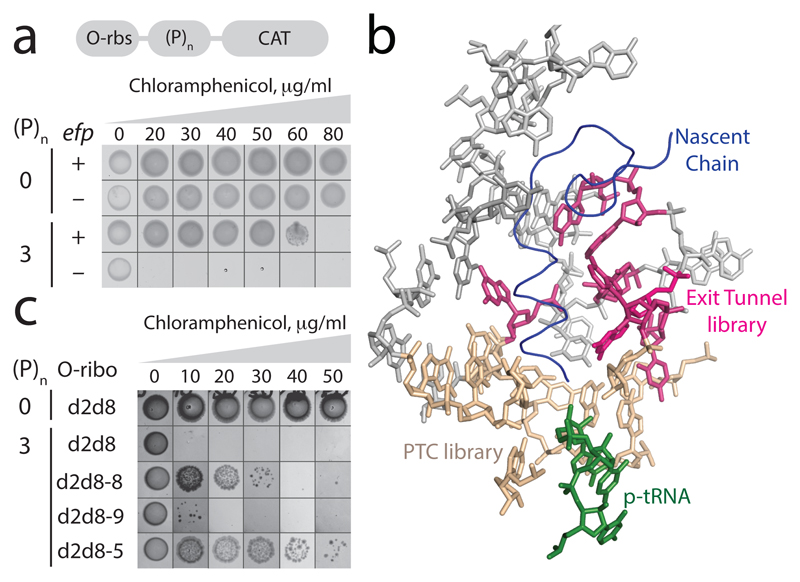

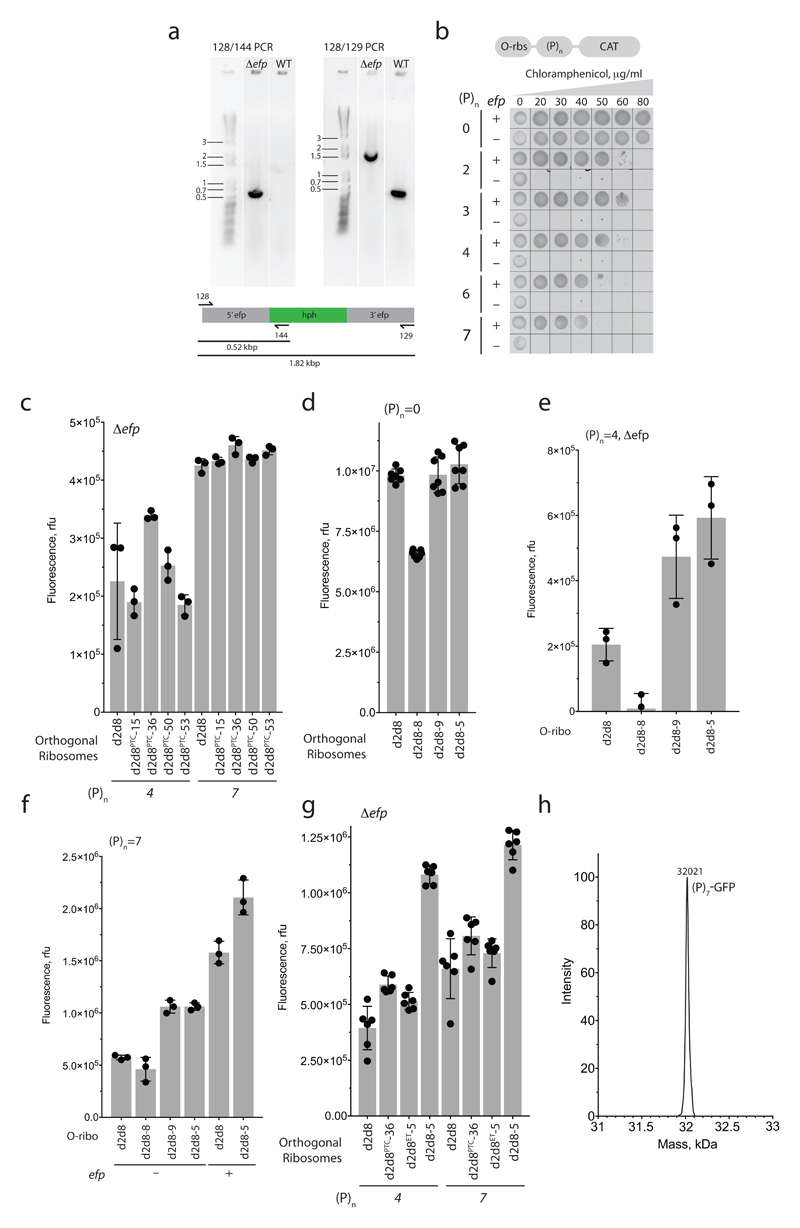

We found that O-d2d8, like the natural ribosome, struggles to translate proline-rich sequences in the absence of EF-P (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 9). We then created a library that randomized ten nucleotides in the peptidyl-transferase centre (PTC) of O-d2d8 (Fig. 4b), and selected those library members that can read through proline coding stretches between an orthogonal ribosome-binding site and a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (O-(P)2-CAT and O-(P)3-CAT), in the absence of EF-P (Fig. 4b). We identified four O-d2d8 variants (Extended Data Fig. 9c and Supplementary Data 12), but none of these constituted a general solution to translating proline-rich sequences. We next created a second library that randomized seven exit tunnel nucleotides (Fig. 4b), using the four previously selected PTC variants as templates. We identified ten O-d2d8 variants following this selection, including O-d2d8 (5) (Supplementary Data 12). Notably, O-d2d8 (5) confers the ability to translate proline rich sequences at a level approaching that facilitated by EF-P (Fig. 4c), enhances the translation of polyproline sequences of varying lengths in several contexts, and can act synergistically with EF-P (Extended Data Fig. 9d-g). O-d2d8 (5) produces (P)7-tagged green fluorescent protein (GFP) with the expected total mass, confirming that it translates through polyproline sequences with good fidelity (Extended Data Fig. 9h). O-d2d8 (5) contains 15 nucleotide mutations (Supplementary Data 12); the G2061U mutation, and other purine-to-pyrimidine mutations may relieve the steric clash between the exit tunnel and proline residues in the growing nascent chain21. Our results provide a first example of accessing new, previously inaccessible function in the large subunit of an orthogonal ribosome.

Figure 4. Discovering O-d2d8 variants with the intrinsic ability to translate polyproline sequences.

a, Top, the O-rbs–(P)n–CAT gene, in which an orthogonal ribosome-binding site (O-rbs) directs the translation of proline (P) codons (n=0 or 3) followed by the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene. When the number of proline codons is 0, the O-d2d8 ribosome can translate the CAT gene even in the absence of efp (encoding EF-P), and thus confers resistance to chloramphenicol. In the absence of efp, the ribosome cannot translate through the polyproline (n = 3) sequence and thus cannot translate the CAT gene; hence the strain is not resistant to chloramphenicol and does not grow. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. b, The region of the ribosome that we targeted for mutation (PDB accession code 5NWY) in order to facilitate translation of polyproline sequences. Beige, nucleotides (C2063, G2447, A2450, A2451, C2452, U2506, G2583, U2584, U2585 and A2602) of the 23S rRNA in the peptidyltransferase centre (PTC) that were randomized. Pink, nucleotides (2058A, 2059A, 2061G, 2062A, 2501C, 2503G and 2505G) in the exit tunnel that were randomized. c, Chloramphenicol resistance provided by evolved O-d2d8 variants in the absence of EF-P. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Note that cells grow more slowly in strains lacking EF-P.

We have demonstrated how controlling the association of ribosome subunits and directing both subunits to an orthogonal message enables the evolution of new large subunit function that has not been accessed in natural ribosomes. Our work provides a foundation for further evolution of the rRNA in the entire O-stapled ribosome; it may facilitate the evolution of O-stapled ribosomes for non-natural bond forming reactions26–29, and the selective recruitment of tRNAs and other translation factors to write orthogonal genetic codes2,3,30. Thus we anticipate that our approach will facilitate the encoded cellular synthesis of biopolymers with non-natural backbone chemistries7.

Methods

Generation of the linker length library for the O-stapled ribosome

We altered the linker length in the O-stapled rDNA in a modular fashion with a modified GoldenGate cloning procedure31, using the primer pairs long-XX-f and long-XX-r and short-XX-f and short-XX-r (for all oligonucleotide sequences see Supplementary Data 1) with pRSF-O-ribo(h44H101) as a template. h44 is helix 44; H101 is Helix 101; O-ribo(h44H101) is also called O-d0d0, for consistency with the naming scheme for describing linker-length variants. All of the resulting long fragments and short fragments were uniquely combined. The resulting O-stapled rDNA plasmids were sequence verified.

In vivo activity assay for O-stapled ribosomes

Escherichia coli Genehogs cells containing a plasmid carrying the Methanosarcina mazei pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylS)/tRNACUA pair, (pKW132), a reporter plasmid carrying a GFP150TAG gene preceded by an orthogonal ribosome binding site1, and a plasmid containing a linker-length variant of the O-stapled ribosome were assayed following induction of expression with 1mM isopropropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The OD600, and fluorescence at 485/520 nm were measured on a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices). The fluorescence was normalized by OD600 and baseline autofluorescence was deducted.

Generation of MS2-tagged O-ribosome variants

The MS2 stem loop flanked on either end by three uridine residues and two SpeI sites was inserted in place of nucleotides 83-86 at the tip of helix 6 of the 16S rDNA portion of different pRSF-O-ribo(h44H101) variants. The insertion was carried out through a one step, site-directed mutagenesis protocol33, using Forward-ms2 and Rev-ms2 primers.

Cloning, expression and purification of GST-tdMS2CP

The sequence encoding the bacteriophage MS2 tandem dimer (tdMS2CP) was custom-synthesized (by Genscript) to contain the V29I mutation34 in one monomer, the V75E/A81G double mutation35 in the other, and a GSSGGSSG linker between the two monomers. It was then subcloned into plasmid pGEX-4T1, expressed and purified on 4b glutathione-sepharose resin (GE Healthcare) that had been washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The eluent was dialysed three times in 4 l PBS supplemented with 20% v/v glycerol, aliquoted and stored at -80°C.

Expressing MS2-tagged O-stapled ribosomes for affinity purification

DH10B cells containing the p15A-O-cat plasmid as well as a pRSF plasmid encoding a member of the MS2-tagged O-stapled-ribosome linker-length library were grown to an OD600 0.05, and then induced with 1 mM IPTG (3 h, 37 °C). The culture was then immediately cooled in an ice bath for 30 min to halt translation initiation and to allow ribosomes on mRNAs to finish translation. Cells from each culture were pelleted (50 ml, 4,000 r.p.m., 10 min, 4 °C), resuspended in 1 ml ribosome lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme) and lysed for three freeze–thaw cycles; 30 μl 10% sodium deoxycholate was then added to complete lysis. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (13,000 r.p.m., 20 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was used for immediate analysis or was flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Sucrose gradient and affinity purification of O-stapled ribosomes

Lysates containing MS2-tagged O-stapled ribosomes were first purified using sucrose gradient fractionation: 10–40% linear sucrose gradients (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), 100 μM benzamidine, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)) were generated using a BioComp Gradient Station (BioComp Instruments). Ten A260 units of the lysate were layered directly onto each sucrose gradient (14 ml) and spun in an ultracentrifuge using a SW 40 Ti rotor at 37,000 r.p.m. for 3 h at 4 °C. Gradients were fractionated using the BioComp Gradient Station with a flow rate of 0.3 mm s−1. Fractions were monitored via the absorption profile at 254 nm, and manually collected over the collection window.

To prevent nonspecific sticking, the GST-tdMS2CP-bound resins (roughly 0.5 ml solid beads) were incubated with 1 mg sheared salmon sperm DNA for 30 min at 4 °C. The pooled ribosome fractions as described above (from ten A260 units of the lysate) were then added to the GST-tdMS2CP-bound resins (roughly 0.5 ml solid beads) and incubated with gentle mixing for 1 h at 4 °C. The resins were washed extensively, twice with 10 ml ribosome-binding buffer at 4 °C, and twice more with 10 ml ribosome-binding buffer with 0.05% Tween-20; the wash steps were separated by gentle mixing at 4 °C for at least 20 min. To harvest RNA species bound to resins, we treated the resulting resin pellet with QIAzol (500 μl) for 5 min at room temperature. Chloroform (100 μl) was then added, and the mixture vortexed and centrifuged (12,000g, 5 min, 4 °C). The upper aqueous phase was collected and mixed in a 1:1 v/v ratio with isopropanol. After incubation at −20 °C for 30 min, the RNA pellet was compacted by centrifugation (15,000g, 15 min, 4 °C), washed once with 70% ethanol, and air-dried, and the ratio of O-stapled ribosome to endogenous subunits was determined. Control experiments from cells without the MS2-tagged ribosome were used to remove contributions from nonspecific capture. We defined the 30S and 50S cross-assembly coefficients as the ratio of 30S or 50S to O-stapled ribosome. For a small number of O-stapled ribosomes MS2 purifications were less efficient and we were not able to determine cross assembly coefficients.

Constructs and O-ribosomes for orthogonal translation in vitro

The construct pCF-sfGFP, contains a T7 promoter, a wild-type ribosome binding site (rbs) and an sfGFP gene. pCF-O-sfGFP, has an orthogonal ribosome binding site replacing the wild-type site, as well as AT-rich sequence separating the T7 promoter and the O-rbs, introduced with primers z71 and z72. We introduced antibiotic-resistance mutations to the O-stapled ribosome subunits by standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods.

Preparation of cell extracts containing orthogonal ribosomes

E. coli BL21 cells were transformed with pRSF-O-ribo(h44H101) variants or pRSF-O-Ribo1. Overnight cultures were used to inoculate 2xTYPG medium supplemented with 10 mM MgSO4, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 µg ml-1 kanamycin, and 0.2 mM IPTG to a starting OD600 of 0.05 and grown until OD600 reached 2.5. Cells were chilled rapidly on an ice-water bath, pelleted at a relative centrifugal force (RCF) of 5,000 at 4°C for 10 min, and washed three times with ice-cold buffer A (10 mM Tris-acetate pH 8.2, 14 mM Mg(OAc)2, 60 mM KOAc and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)). The washed cell pellets were weighed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80ºC. Just before use, cells were rapidly thawed and suspended in 1 ml of Buffer A per gram of wet cell mass. Cells were either grown in 1 l volume in baffled 2.5 l conical flasks with agitation at 150 r.p.m. (for reference lysate samples), or in 50 ml volume in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks with agitation at 270 r.p.m. (for activity screening of O-stapled ribosome variants). Cells grown on a litre scale were lysed with EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) and prepared as previously reported36. Cells grown on 50-ml scale were lysed via sonication using a VCX750 Instrument (Sonics&Materials, USA) equipped with a 2 mm diameter 8 tip probe (QSonica, USA) as described36 with the following sonication parameters: frequency 20 kHz, 20% of amplitude, 5 s/10 s sonication/rest regime, and energy input 400 J. Lysates were clarified via centrifugation at 21,000 RCF at 4°C for 20 min. The top 200 µl of the lysate were taken and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C. The total amount of protein in cell extracts, as quantified by the Bradford detergent-free protein assay, was consistently 8 ± 2.8 mg ml-1.

Translation by O-ribosomes after native-ribosome inhibition

In vitro translation reactions were carried out in a 384-well plate with reaction volume of 12.5 µl. The reaction mixture for protein synthesis was prepared as described37. Reactions were carried out at 30ºC for at least 4 h. Synthesis of superfolder GFP (sfGFP) was monitored on an Infinite 200 Pro plate reader (Tecan AG, Switzerland).

We carried out three types of in vitro translation reaction for each O-stapled ribosome variant. First, to control for the quality of the lysate that contains a mixture of endogenous and O-stapled ribosomes, we added the reporter plasmid pCF-sfGFP (which includes the wild-type ribosome-binding site) to the reaction and measured GFP production. Second, we added pCF-O-sfGFP to the reaction and measured GFP production from the orthogonal ribosome-binding site. Finally, we added pCF-O-sfGFP, 10 μM spectinomycin and 50 μM erythromycin and measured GFP production from the orthogonal ribosome-binding site when native subunits were inhibited. The GFP signal obtained from the reaction with pCF-sfGFP was used to normalize the GFP signal measured from pCF-O-sfGFP. The background signal that originates from the activity of endogenous ribosomes on the orthogonal message was measured in lysates containing only endogenous ribosomes and pCF-O-sfGFP, and was subtracted from the normalized GFP signals measured when an O-stapled ribosome was present in the lysate. The activity of an O-stapled ribosome in the presence of 10 μM spectinomycin and 50 μM erythromycin divided by its activity in the absence of antibiotics provides a ratio that allows us to compare O-ribosomes of different total activity. For graphing, the highest such ratio was set to 1 and relative values between 0 and 1 are reported for other O-stapled ribosomes. We cannot determine the absolute fractional activity of translation resulting from only O-ribosome subunits because we cannot determine the extent to which erythromycin inhibits the stapled large subunit. Previously described ribosomes with linked subunits had low in vitro translation activities that precluded their characterization in this system.

Genomic replacement of an rRNA operon by ribo-REXER

Ribo-REXER is a modification of REXER18. A landing site-containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene as a positive and the SacB gene as a negative selection marker – was introduced at the 5’ flank of the rrnE RNA operon in the genome of SQ110 E.coli19 by Red/ET recombination (Gene Bridges). Correct integration was validated by phenotyping, colony PCR using primer pair WS441f/r and sequencing, and resulted in plasmid SQ110CAT-SacB.

Candidate CRISPR target sequences 5’ and 3’ of the rrnE region were identified using ChopChop38,39 and matched to sequences on the incoming donor plasmid, so that the linearized product would retain homology arms of 50 base pairs on both the 5’ and the 3’ flank with respect to the targeted genomic region. The plasmid containing the four spacers for REXER 4 was cloned by PCR mutagenesis of the spacer plasmid18, and subsequently shortened to contain only the two-spacer cassette necessary for REXER 2.

The donor plasmid containing flanking homology regions and protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences for integration at the rrnE locus was constructed by In-Fusion cloning (Takara). The sequences chosen for targeting 5’ of the incoming rRNA operon and 3’ of the pH cassette (which comprises the E. coli PheS-derived negative selection marker PheS* (T251A A294G)40 paired with an hph gene, enabling resistance to hygromycin B) were CATTAATTGCGTTGCGCACGGGG and AGGCAAGACCGAGCGCCATTTGG. Donor plasmids containing stapled O-rDNA were created from the parent donor plasmid.

REXER was performed essentially as described18 using the spacer cassette: ttaataactaaaaatatggtataatactcttaataaatgcagtaatacaggggcttttcaagactgaagtctagctgagacaaatagtgcgattacgaaattttttagacaaaaatagtctacgaggttttagagctatgctgttttgaatggtcccaaaacCattaattgcgttgcgcacggttttagagctatgctgttttgaatggtcccaaaacAGGCAAGACCGAGCGCCATTgttttagagctatgctgttttgaatggtcccaaaacttcagcacactgagacttgttgagttgaattcggtcagtgcg

We identified rDNA replacements by colony PCR using primers WS467f/341r,WS218f/467r, and total RNA extraction. Loss of the incoming plasmid was confirmed by extracting plasmid DNA (Plasmid Miniprep Kit, Qiagen), and testing (by PCR amplification of the SpcR locus) for the presence of the tRNA helper plasmid ptRNA67 present in Δ6 and Δ7 strains, and for loss of the donor plasmid backbone, and also by transforming TOP10 E. coli cells with the extracted plasmid mixture and testing for the formation of colonies on LB agar plates containing 75 μg/ml spectinomycin, but not 150 μg/ml hygromycin B. Growth rates were determined by growing at minimum eight colonies from a validated strain in 2xTY growth medium containing 75 μg ml-1 spectinomycin, 150 μg ml-1 hygromycin B and 1% glucose.

Automated parallel evolution

The Δ6 d2d8 strain was transformed with the mutagenesis plasmid MP6 (ref.41) and grown on LB agar containing 2% glucose, 150 μg ml-1 hygromycin B, 75 μg ml-1 spectinomycin and 50 μg ml-1 chloramphenicol. We picked 92 individual colonies into wells containing liquid media. Random mutagenesis was induced by addition of 25 mM arabinose to each well, creating mutator cultures in each well. The mutator cultures were incubated for 48 h at 37°C and 200 r.p.m.41. Following a 1:400 dilution step into fresh growth media, the incubation was repeated. The remaining four wells of the culture plate were inoculated with colonies from Δ6 d2d8 and grown in 1% glucose.

We diluted 0.5 μl of each culture into 200 μl of liquid medium containing 1% glucose in a fresh lidded ‘growth’ plate, and then incubated the plates (37°C, 400 rpm, 2h). We measured the OD600 in each well at the start and then again periodically (every 2-9 h) depending on the growth rate. When the OD600 reached a threshold of 0.5 for at least three mutator-culture wells, all cultures were diluted. If fewer wells reached the threshold, the three wells with the present highest OD600 were identified. This process was repeated once more, and if the threshold was not reached after 20 h, the plate was incubated for a further 12 h before the dilution step was implemented independently of the measured cell density. This allowed for dynamic maintenance of a week-long evolution experiment that flexibly adjusted the selective pressure on the system on the basis of the observed bacterial growth behaviour during each step. After an estimated 110 generations, the workflow— which we implemented on a Beckmann robotics platform—was terminated and glycerol stocks were created from the final growth plate. The pools with the highest final OD600 measurements were carried forward, and growth curves were recorded for individual clonal lines derived from each pool.

The resulting Δ6 d2d8 strains were characterized by colony PCR and total RNA extraction, and their genomes were sequenced (Miseq, Illumina). The sequencing data was aligned to a reference sequence derived from strain SQ110 (GenBank, NCBI) using a Bowtie script (https://github.com/TiongSun/iSeq)42. Every called mutation was then filtered43 to identify mutations introducing an in-frame stop codon and any non-silent mutation within an open reading frame.

Stapled ribosome preparation for cryo-EM

Escherichia coli cells expressing only stapled ribosomes (Δ6 d2d8 E10) were grown in 6 l of 2xTYPG media supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C with agitation, until the OD600 reached 0.5–0.6. Cells were rapidly chilled in an ice-water bath, harvested by centrifuging at 5,000 RCF at 4 °C for 10 min, washed twice in ice-cold TBST buffer and washed once with ice-cold buffer ‘100/10’ (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 100 mM NH4Cl, 10.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT). The cell pellet was resuspended in ten volumes of ice-cold ‘100/10’ buffer and lysed with EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) at a variable pressure of 17,000 to 20,000 p.s.i., passing twice. Cell debris was removed by two rounds of centrifugation at 30,000 RCF at 4 °C for 30 min, with only the top 60–80% of the volume being passed to the next stage. The S30 supernatant was loaded on 1.25 volumes of 1.1 M sucrose in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 500 mM NH4Cl, 10.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT and centrifuged in a Type 45 Ti rotor (Beckman-Coulter) for 18 h at 37,000 r.p.m. at 4 °C. Glassy pellets were washed three times with ice-cold ‘100/10’ buffer and dissolved in the same buffer by agitation on ice. Then, approximately 400 OU260 (where OU is optical unit) of salt-washed ribosomes were loaded onto six SW32 tubes containing 10–40% linear sucrose gradients in ‘100/10’ buffer and centrifuged for 18 h at 17,000 r.p.m. and 4 °C. Fractions corresponding to the 70S peak were collected on a BioComp gradient station, pelleted in a Type 70 Ti rotor (Beckman-Coulter) at 55,000 r.p.m. for 2.5 h and 4 °C, and dissolved in ‘100/10’ buffer. The sample concentration was estimated at 485 OU260 per ml and aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Cryo-electron cryomicroscopy

Quantifoil copper R2/2 400-mesh grids were coated with a thin sheet (around 60 Å) of amorphous carbon and glow-discharged for 5 s at 5 mA. Purified E. coli 70S d2d8 ribosomes were diluted to 100 nM in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 100 mM KOAc, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2 and applied to grids in 3 µl aliquots. Grids were incubated for 30 s at 4ºC and 100% humidity, blotted for 4.5 s and frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark III (FEI). Micrograph movies of d2d8 70S ribosomes were collected on a Titan Krios microscope at 300 keV with a Falcon III detector using automated data collection with EPU software (all FEI). Movies were collected at a pixel size of 1.06 Å with a dose rate of 15 e-Å-2s-1 over a 1.79-s exposure, consisting of 71 total frames. Defocus values of –3.2, –2.9, –2.6, –2.3, –2.0 and –1.7 μm were used.

Image processing

All processing was done using RELION-2.1 (ref. 44). Micrograph movie frames were aligned using Motioncorr45 and contrast transfer functions calculated using Gctf46. Aligned movies were removed after manual inspection if micrographs contained ice particles or if contrast transfer functions failed to calculate. Ribosome particles were picked semi-autonomously47; incorrectly picked non-ribosomal particles were identified and discarded by reference-free two-dimensional classification. The resulting 306,214 particles were used for initial three-dimensional refinement with an E. coli 70S ribosome (EMD-3493) low-pass-filtered to 40 Å as a reference. Three-dimensional classification of the initial reconstruction was performed without alignments to discard poorly aligned particles. Two major classes were obtained, one of closed 70S ribosomes (94,461 particles) and another containing ‘opened’ 70S ribosomes (128,436 particles). The closed ribosomes were selected and refined. Focused classification with signal subtraction48 on the RNA hinge gave the final primary class (94,371 particles). The quality of the density in the hinge region is lower than that in other parts of the structure. However, classification focused on the staple revealed a single class, demonstrating sample homogeneity. This indicated that the lower density in this region is not due to a mixture of particles; it may instead reflect flexibility in the hinge and/or local variation in the hinge conformation.

Model building

A model (PDB 5MDZ) of the E. coli 70S ribosome20 was docked into the reconstruction in Chimera49, and individual RNA and protein chains were rigid body fitted using Coot50. Portions of helix 44 from the 16S rRNA and Helix 101 from the 23S rRNA were deleted according to the sequence of the d2d8 ribosome. The RNA hinge expected to link the two subunits was then docked into the remaining, unaccounted-for density. Real-space refinement was carried out using Phenix51 and the model was validated using MolProbity52. Figures were created using Pymol53 or Chimera49.

O-stapled ribosomes for polyproline polymerization

A PTC library with a theoretical diversity of 1.1x106 was constructed by randomizing nucleotides C2063, G2447, A2450, A2451, C2452, U2506, G2583, U2584, U2585 and A2602 of the 23S rRNA portion of O-d2d8 through rounds of enzymatic inverse PCR, with pRSF-O-d2d8 as a starting template and using primers WS297_Gf, WS297_Tf, WS297_Af and WS297r. The resulting four clones were used in parallel enzymatic inverse PCR reactions with WS275f and WS275r. The four ‘sub-libraries’ were combined to form the final library with all ten positions randomized. Transformations led to around 3 × 107 to 10 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) per sub-library (theoretical diversity 2.6 × 105); this 100-fold oversampling leads to high confidence that the library’s theoretical diversity is covered in the plasmids collected. Libraries were also verified by direct sequencing of the randomized DNA and by sequencing around 20 separate clones.

The exit-tunnel library was prepared by randomizing the 23S rRNA nucleotides 2058A, 2059A, 2061G, 2062A, 2501C, 2503G and 2505G from the four most active mutants in the PTC library, namely O-d2d8PTC-15, O-d2d8PTC-36, O-d2d8PTC-50 and O-d2d8PTC-53, by enzymatic inverse PCR. The first reactions were performed with primers Lib_1_15, Lib_1_36_50 or Lib_1_53 and a Lib1r_all. The second enzymatic inverse PCR used Lib2_r_all, as well as one of three forward primers, Lib_2_15, Lib_2_36_50 or Lib_2_53. The transformation efficiencies at both stages of library preparation were around 107 CFU μg−1 of plasmid DNA. Before transformation into the ribosome-selection strain, all four sub-libraries were mixed in equal proportions. Transformations resulted in approximately 107 CFU per sub-library (theoretical diversity 6.6 × 104); thus, oversampling ensures that the library’s theoretical diversity is covered in the plasmids collected. Libraries were also verified by direct sequencing of the randomized DNA and by sequencing of 12 clones from each sub-library.

To delete efp in TOP10 cells, the promoter and hph gene conferring resistance to hygromycin B were amplified from the pH plasmid using primer pairs z139/z140 and z141/z142, respectively, fused in an overlapping-PCR with z139 and z142 primers. Primers F1/RV1 and F2/RV2 were used to introduce homology regions and FRT sites. Column-cleaned PCR product was used for lambda red recombination54. The correct insertion of the hph gene at the efp locus was verified in hygromycin-resistant colonies by colony PCR reactions using primers z128/z144 and z128/z129.

p15A-O-(P)n-CAT was constructed from a plasmid derived from p15-O-CAT with the forward primer z150 and the reverse primers z145, z146, z147, z148 and z149. p15A-O-(P)4-GFP and p15A-O-(P)7-GFP were cloned by replacing the CAT gene in the corresponding p15A-O-(P)4-CAT and p15A-O-(P)7-CAT plasmids with the sfGFP gene using Gibson assembly reactions.

To select O-d2d8 ribosome variants capable of translating polyproline sequences, we transformed E. coli TOP10 Δefp cells with p15A-(P)2-O-CAT or p15A-(P)3-O-CAT reporter plasmids. The pRSF-O-d2d8 libraries were transformed into these cells by electroporation55. Following growth and then induction of rRNA expression (1 mM IPTG, 4 h), the equivalent of 1 ml of culture at an OD600 of1was spread out on 2×TY agar 20cm×20cm plates with 12.5μg ml−1 kanamycin, 4 μg ml−1 tetracycline, 1 mM IPTG and 20 μg ml−1 or 50 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 days. Following selection, pRSF-O-d2d8 mutant plasmids were isolated and retransformed into E. coli TOP10 Δefp cells containing the reporter plasmid p15A-(P)2-O-CAT or p15A-(P)3-O-CAT and used to check the phenotype. To ensure that mutations in the 23S rRNA portion of O-d2d8 were responsible for the observed phenotype, we subcloned the selected 23S, PTC-containing fragments into a fresh pRSF-O-d2d8 backbone. All obtained recloned mutant plasmids were sequence verified. To test the activity of O-d2d8 mutants in translating O-(P)n-GFP reporters, we transformed Δefp E. coli cells containing p15A-(P)n-O-sfGFP reporters with pRSF-O-d2d8 mutant plasmids. GFP fluorescence and cell density were measured hourly on a SpectraMax i3 Multi-Mode Detection Platform (Molecular Devices) in a culture induced with IPTG. The measured GFP fluorescence was normalized by cell density (OD600).

Statistics for Figures

For Fig 2b, the number of replicates (n) was 6 for all data, except in the case of p3d5, where n = 5. Error bars represent ± s.e.m.

For Figure 3d and Extended Data Fig. 7c, growth rates were determined from n = 8 independently grown bacterial colonies. Curve fitting (logistic growth) was performed using Prism 7 (Graphpad). Error bars show ± s.e.m. It is not possible to plot individual points because the means and errors were derived from the best fit to all growth curves simultaneously.

For Extended Data Fig. 2a, n=6 for all MS2 experiments.

The standard deviations for MS2-tagged O-stapled ribosome variants were as follows (in parentheses): d0d0 (12.4), d0d1 (23.7), d0d2 (25.5), d0d3 (21.5), d0d4 (20.9), d0d5 (34.4), d0d6 (39.1), d0d7 (35.4), d0d8 (31.0), d1d0 (15.0), d1d1 (18.6), d1d2 (23.0), d1d3 (22.5), d1d4 (1.6), d1d5 (31.7), d1d6 (28.7), d1d7 (33.0), d1d8 (25.1), d2d0 (33.4), d2d1 (36.0), d2d2 (28.2), d2d3 (29.7), d2d4 (21.7), d2d5 (27.1), d2d6 (11.2), d2d7 (35.0), d2d8 (36.7), d3d0 (25.0), d3d1 (36.9), d3d2 (30.9), d3d3 (27.4), d3d4 (19.3), d3d5 (31.6), d3d6 (22.2), d3d7 (30.3), d3d8 (45.0), d4d0 (14.7), d4d1 (17.1), d4d2 (12.9), d4d3 (2.0), d4d4 (7.6), d4d5 (24.3), d4d6 (23.4), d4d7 (29.8), d4d8 (32.9), d5d0 (8.6), d5d1 (16.5), d5d2 (24.1), d5d3 (23.9), d5d4 (20.0), d5d5 (23.6), d5d6 (29.8), d5d7 (31.5), d5d8 (30.8), p1d0 (13.8), p1d1 (27.3), p1d2 (27.3), p1d3 (21.8), p1d4 (3.9), p1d5 (40.8), p1d6 (36.4), p1d7 (36.3), p1d8 (27.3), p2d0 (7.1), p2d1 (29.4), p2d2 (33.3), p2d3 (25.7), p2d4 (22.9), p2d5 (29.2), p2d6 (30.8), p2d7 (30.0), p3d0 (2.7), p3d1 (25.2), p3d2 (22.3), p3d3 (21.9), p3d4 (32.5), p3d5 (49.1), p3d6 (43.5), p3d7 (37.3) and p3d8 (12.0).

For untagged ribosomes, n=6 for all data except in the case p3d5, where n=5. The standard deviations for untagged O-stapled ribosome variants were d0d0 (7.9), d0d1 (8.7), d0d2 (4.8), d0d3 (5.9), d0d4 (3.2), d0d5 (6.2), d0d6 (13.6), d0d7 (4.9), d0d8 (24.2), d1d0 (5.4), d1d1 (4.5), d1d2 (4.4), d1d3 (18.0), d1d4 (0.7), d1d5 (6.9), d1d6 (3.8), d1d7 (4.5), d1d8 (26.5), d2d0 (12.2), d2d1 (7.0), d2d2 (21.8), d2d3 (5.0), d2d4 (8.4), d2d5 (5.9), d2d6 (5.7), d2d7 (5.0), d2d8 (6.9), d3d0 (11.1), d3d1 (6.2), d3d2 (5.5), d3d3 (5.3), d3d4 (6.0), d3d5 (7.0), d3d6 (21.3), d3d7 (25.1), d3d8 (9.2), d4d0 (6.3), d4d1 (4.9), d4d2 (4.7), d4d3 (1.2), d4d4 (2.7), d4d5 (8.5), d4d6 (22.0), d4d7 (26.9), d4d8 (26.9), d5d0 (5.1), d5d1 (7.2), d5d2 (2.0), d5d3 (2.3), d5d4 (2.4), d5d5 (13.7), d5d6 (12.0), d5d7 (6.6), d5d8 (5.2), p1d0 (5.9), p1d1 (8.3), p1d2 (4.7), p1d3 (4.3), p1d4 (0.6), p1d5 (5.9), p1d6 (14.7), p1d7 (10.1), p1d8 (29.9), p2d0 (2.9), p2d1 (7.2), p2d2 (6.7), p2d3 (7.0), p2d4 (12.6), p2d5 (17.7), p2d6 (19.3), p2d7 (30.9), p3d0 (0.9), p3d1 (5.9), p3d2 (8.8), p3d3 (11.9), p3d4 (21.4), p3d5 (22.8), p3d6 (22.9), p3d7 (44.3) and p3d8 (9.3).

For Extended Data Fig. 4b, n, n values for the in vitro measurements are the same as in Extended Data Fig. 5c (below) For the in vivo measurement n=6, except in the case of p3d5, where n=5. The error bars represent the S.E.M.

For Extended Data Fig. 4e, that were n=4 independent replicates. The standard deviations are: (0, 0)±0.4, (5, 0)±0.4, (10, 0)±0, (20, 0)±0, (50, 0)±0, (100, 0)±0, (0, 5)±4.6, (5, 5)±21.8, (10, 5)±13.3, (20, 5)±7.5, (50, 5)±11.6, (100, 5)±8.3, (0, 10)±4.3, (5, 10)±14.1, (10, 10)±31.2, (20, 10)±32.6, (50, 10)±26.7, (100, 10)±16, (0, 20)±3.6, (5, 20)±37.5, (10, 20)±38.3, (20, 20)±24.8, (50, 20)±37.9, (100, 20)±23.4, (0, 50)±2.7, (5, 50)±38.7, (10, 50)±55.7, (20, 50)±30.7, (50, 50)±20.6, (100, 50)±40.1, (0, 100)±5.9, (5, 100)±20.8, (10, 100)±23.8, (20, 100)±25.3, (50, 100)±27.2 and (100, 100)±29.8, where the first digit in the parentheses corresponds to the concentration of erythromycin and the second to the concentration of spectinomycin (both in μM).

For Extended Data Fig. 5a, n (in parentheses) was as follows: d0d0 (3), d0d2 (3), d0d5 (4), d0d6 (4), d0d7 (5), d0d8 (4), d1d5 (3), d1d6 (3), d1d7 (8), d1d8 (4), d2d3 (4), d2d5 (4), d2d6 (4), d2d7 (4), d2d8 (4), d3d1 (3), d3d2 (4), d3d5 (4), d3d6 (4), d3d7 (4), d3d8 (4), d4d5 (4), d4d6 (4), d4d7 (10), d4d8 (10), d5d4 (3), d5d7 (4), p1d5 (4), p1d6 (4), p1d7 (3), p1d8 (4), p2d1 (4), p2d4 (3), p2d5 (3), p2d6 (5), p2d7 (3), p3d5 (4), p3d6 (3), p3d7 (3) and p3d8 (2).

For Extended Data Fig. 5b, c n was as follows: d0d0 (3), d0d2 (3), d0d5 (4), d0d6 (4), d0d7 (4), d0d8 (4), d1d5 (3), d1d6 (3), d1d7 (7), d1d8 (4), d2d3 (4), d2d5 (4), d2d6 (3), d2d7 (4), d2d8 (4), d3d1 (3), d3d2 (4), d3d5 (3), d3d6 (4), d3d7 (4), d3d8 (4), d4d5 (4), d4d6 (4), d4d7 (8), d4d8 (7), d5d4 (2), d5d7 (4), p1d5 (4), p1d6 (3), p1d7 (2), p1d8 (4), p2d1 (4), p2d4 (3), p2d5 (2), p2d6 (4), p2d7 (3), p3d5 (4), p3d6 (3), p3d7 (2) and p3d8 (2).

For Extended Data Fig. 5d n was as follows: d0d0 (5), d0d2 (5), d0d5 (4), d0d6 (3), d0d7 (3), d0d8 (3), d1d5 (4), d1d6 (4), d1d7 (5), d1d8 (4), d2d0 (4), d2d3 (4), d2d5 (4), d2d6 (4), d2d7 (3), d2d8 (4), d3d1 (4), d3d2 (4), d3d5 (4), d3d6 (4), d3d7 (5), d3d8 (5), d4d5 (5), d4d6 (3), d4d7 (4), d4d8 (5), d5d0 (4), d5d4 (4), d5d5 (6), d5d6 (6), d5d7 (4), d5d8 (4), p1d5 (5), p1d6 (4), p1d7 (3), p1d8 (3), p2d1 (3), p2d3 (4), p2d4 (3), p2d5 (3), p2d6 (4), p2d7 (3), p2d8 (3), p3d5 (4), p3d6 (3) and p3d7 (3).

For Extended Data Figure 5e, f n was as follows: d0d0 (4), d0d2 (3), d0d5 (4), d0d6 (5), d0d7 (5), d0d8 (4), d1d5 (3), d1d6 (3), d1d7 (5), d1d8 (4), d2d0 (4), d2d3 (4), d2d5 (4), d2d6 (4), d2d7 (4), d2d8 (4), d3d1 (3), d3d2 (4), d3d5 (4), d3d6 (4), d3d7 (4), d3d8 (4), d4d5 (5), d4d6 (5), d4d7 (5), d4d8 (5), d5d0 (3), d5d4 (5), d5d5 (4), d5d6 (4), d5d7 (4), d5d8 (4), p1d5 (4), p1d6 (4), p1d7 (4), p1d8 (4), p2d1 (4), p2d3 (3), p2d4 (3), p2d5 (3), p2d6 (4), p2d7 (3), p2d8 (3), p3d5 (4), p3d6 (3) and p3d7 (3).

For Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 6 n was as follows: d5d7 (4), d5d6 (3), d5d5 (4), d5d4 (3), d5d0 (3), d4d8 (5), d4d7 (6), d4d6 (8), d4d5 (8), d3d8 (4), d3d7 (4), d3d6 (4), d3d5 (4), d3d2 (4), d3d1 (3), d2d8 (4), d2d7 (4), d2d6 (3), d2d5 (4), d2d3 (4), d1d8 (7), d1d7 (6), d1d6 (3), d1d5 (3), d0d8 (4), d0d7 (5), d0d6 (3), d0d5 (4), d0d2 (3), d0d0 (3), p1d8 (6), p1d7 (4), p1d6 (4), p1d5 (3), p2d8 (3), p2d7 (3), p2d6 (5), p2d5 (3), p2d4 (3), p2d3 (3), p2d1 (4), p3d8 (2), p3d7 (3), p3d6 (3) and p3d5 (4).

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Partitioning of free large subunits between wild-type and orthogonal small subunits, and in vivo activity of O-stapled ribosomes.

a Gain-of-function mutations in free large subunits may confer gain-of-function phenotypes through statistical partitioning of free large subunits between wild-type (WT) and orthogonal small subunits. A mutant large subunit (LSU) can partition between WT and orthogonal (green) small subunits (SSUs) in cells that contain both WT large subunits (not shown) and mutant large subunits. Hence the mutant phenotype will be observed in the translation of both WT and orthogonal messages (see Extended Data Fig. 4d for an example). b In vivo activity of linker length variants of O-stapled ribosomes (same data set as Fig. 2b). GFP expression was analysed in E. coli cells containing the indicated O-ribosome, the Methanosarcina mazei PylRS synthetase/tRNACUA pair, and the O-sfGFP150TAG reporter, in the presence of 1 mM BocK (N-epsilon (tert-butoxylcarbonyl)-l-lysine). GFP fluorescence is shown as a percentage of that produced from an orthogonal ribosome with independent, non-linked subunits. O-d2d8 is highlighted in blue, and O-ribosomes with previously described subunit linkers are in dark grey. Statistics are detailed in the Methods.

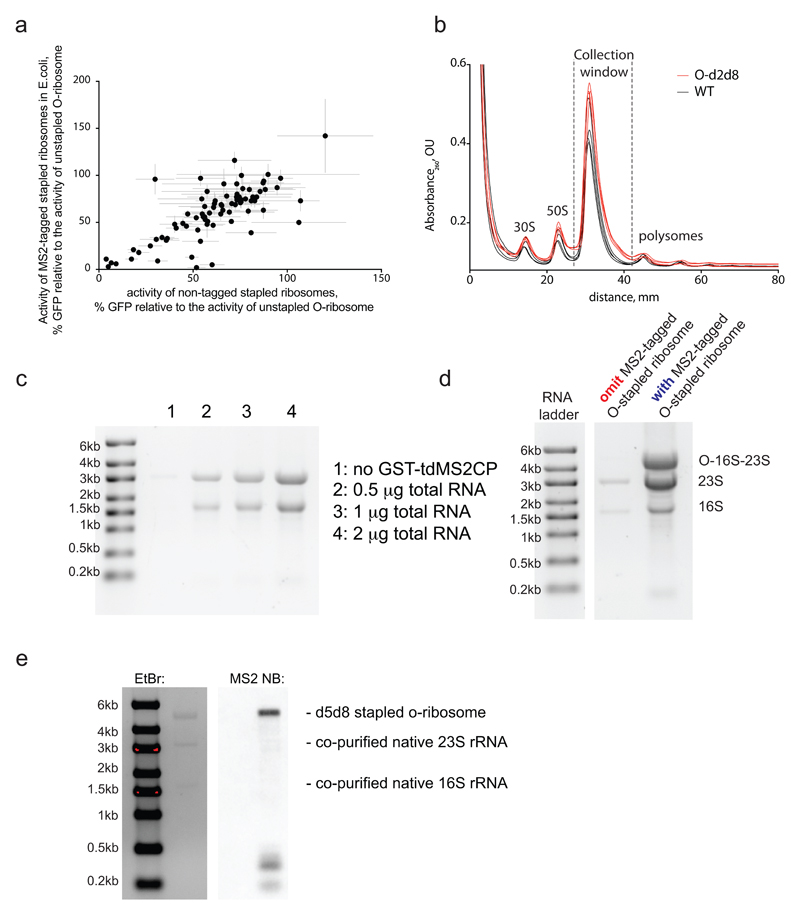

Extended Data Figure 2. MS2 tagged O-stapled ribosomes.

a Tagging O-stapled ribosomes with an MS2 stem loop minimally perturbs in vivo ribosome activity. We measured in vivo ribosome activities via GFP production from an O-sfGFP150TAG reporter, in cells expressing an intact or MS2-tagged linker-length variant of O-stapled ribosome along with the M. mazei pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair (encoded by PylS/pylT) in the presence of 1 mM BocK. GFP fluorescence was normalized to that produced from a non-stapled O-ribosome. For numbers of replicates (n) and statistics, see Methods and Supplementary Data 2. b, Sucrose gradient analysis of an E. coli lysate with and without an O-stapled ribosome variant; n = 3 biological replicates. c, Affinity purification of a non-stapled O-ribosome depends on the presence of GST-tdMS2CP (a fusion between glutathiose-S-transferase (GST) and a mutant of a tandem dimer of the MS2 coat protein (tdMS2CP)) on resin. Affinity purification of MS2-tagged ribosomes was performed on glutathione–sepharose resin with bound GST-tdMS2CP (lanes 2–4) and without GST-tdMS2CP (lane 1). Varying amounts of total RNA were loaded in lanes 2–4. d, Affinity purification depends on the presence of the MS2 RNA stem loop on ribosomes. Pellets of O-p2d6 ribosomes were collected through sucrose cushions. Affinity purifications were performed on glutathione–sepharose resin with bound GST-tdMS2CP. e, O-d5d8-MS2 was affinity purified, and MS2 stem-loop-containing species were probed by northern blot (NB). EtBr, ethidium bromide (a fluorescent stain for nucleic acid). The experiments in c–e were each performed once. For source data regarding gels, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

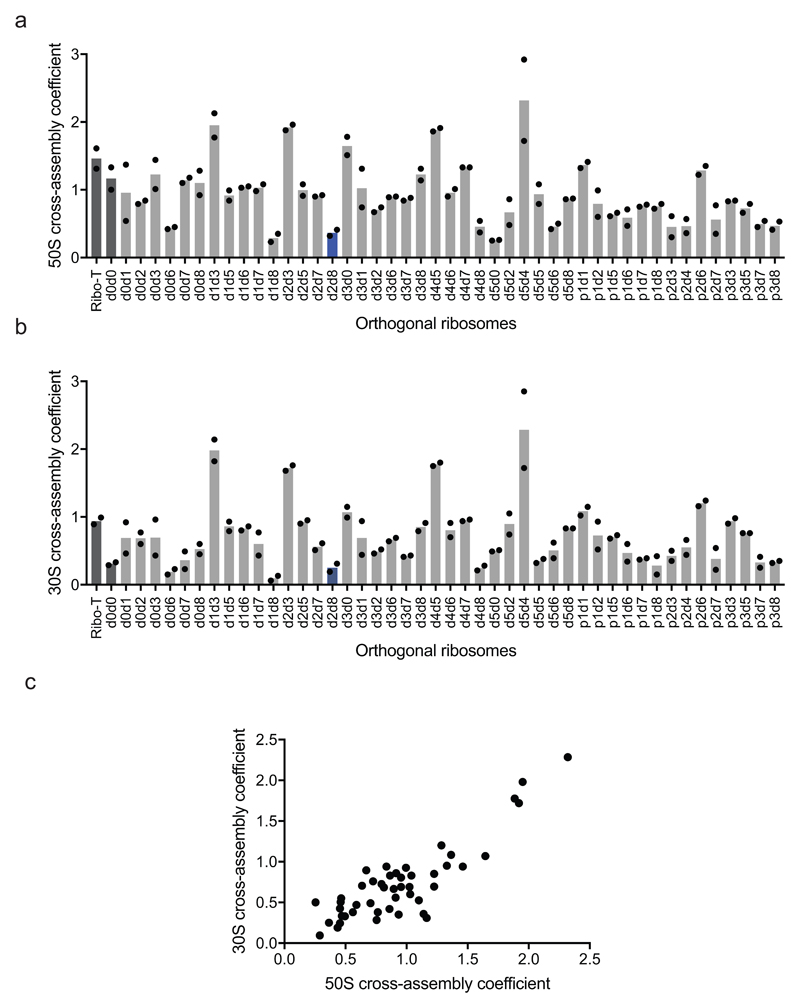

Extended Data Figure 3. Engineered O-stapled ribosome variants minimize cross assembly.

a Screen of 50S cross-assembly coefficients for different O-ribosomes with linked subunits. n = 2 biological replicates; each replicate is shown by a dot, and the bars represent the means (using the same dataset as in Fig. 2d). b, Screen of 30S cross-assembly coefficients. n = 2 biological replicates; each replicate is shown by a dot, and the bars represent the means (using the same dataset as in Fig. 2e). In a and b, more than 90% of ribosomes had cross-assembly coefficients between 0 and 1, as expected. Previously reported O-ribosomes with linked subunits are shown in dark grey, while O-d2d8 is highlighted in blue. c, Correlation between the means (from n = 2 biological replicates) of 50S and 30S cross-assembly coefficients for different O-stapled ribosome variants; the variation in these data is shown in a, b.

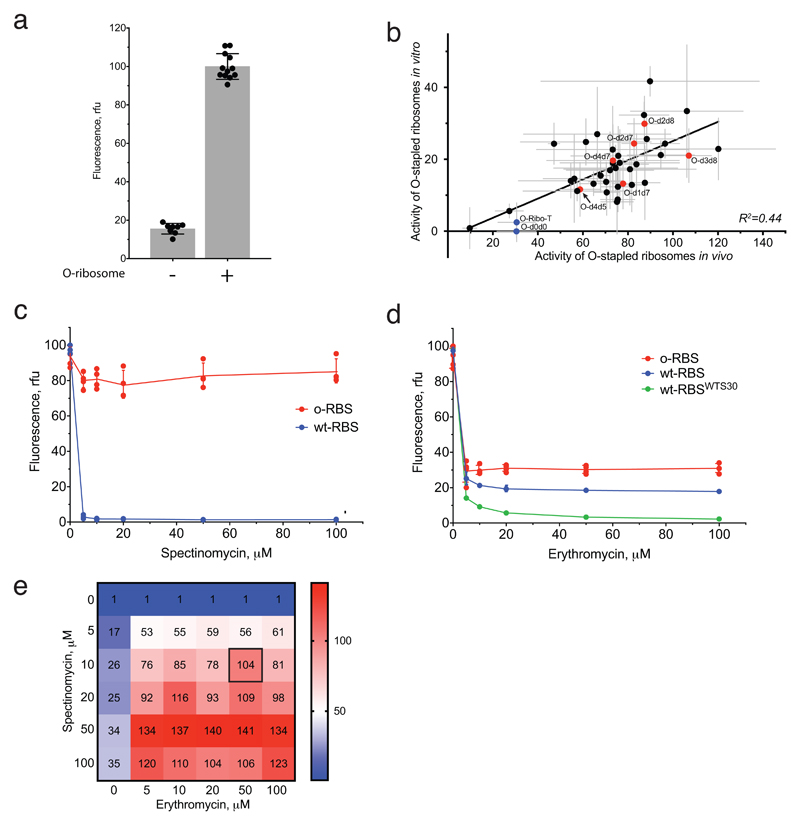

Extended Data Figure 4. In vitro translation activity of O-stapled ribosomes upon inhibition of native ribosomes.

a In vitro translation of T7-O-GFP in the in S30 extracts with and without the non-stapled O-ribosome. The data show the means (grey bars) of, respectively, 12 and 8 independent replicates (dots); the error bars show ±s.d. b In vitro translation activities of O-stapled ribosome variants (y-axis) were measured via the GFP fluorescence produced from T7-O-GFP. In vivo activities (measured as described in Extended Data Fig. 1b) are shown on the x-axis. Individual replicates are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b, and statistics are described in the Methods. c, In vitro translation of T7-O-GFP (O-RBS) or T7-GFP (wt-RBS) in S30 extracts containing the non-stapled O-ribosome in the presence of spectinomycin. The O-16S rRNA of the O-ribosome contains the C1192U mutation, which confers resistance to spectinomycin. The data show the mean of n = 4 independent replicates; error bars are ± s.d. From this, we conclude that 10 μM of spectinomycin is sufficient to inhibit the translational activity of wild-type small subunits in the S30 extract, but has minimal effect on spectinomycin-resistant subunits. rfu, relative fluorescence units. d, In vitro translation of T7-O-GFP (O-RBS) or T7-GFP (wt-RBS) in S30 extracts containing the non-stapled O-ribosome in the presence of erythromycin. The 23S rRNA that is co-expressed with the O-16S rRNA contains the A2058G mutation, which confers resistance to erythromycin. In vitro translation of T7-GFP (wt-RBSWTS30) was also performed in S30 extracts without the O-ribosome. The data show the means of n = 4 independent replicates; error bars show ± s.d. We found that 50 μM erythromycin reduces translation from the wild-type ribosome-binding site to 18.5% of the level seen without erythromycin, and reduces translation from the orthogonal ribosome-binding site to 30% of the level without erythromycin. We conclude that 50 μM erythromycin is sufficient to inhibit wild-type large subunits in the S30 extract. e, Ratios of GFP produced from T7-O-GFP versus T7-GFP in S30 extracts containing the non-stapled O-ribosome are shown as a function of spectinomycin and erythromycin concentration. The data are means of n = 4 independent replicates; statistics are in the Methods.

Extended Data Figure 5. Activities of O-stapled ribosome linker-length variants in cell free protein synthesis.

a, Activities of lysates that contain a mixture of host and O-stapled ribosomes on a WT-GFP reporter, showing that the translation machinery in the tested lysates is equally active. Every data point shows the activity of an independently produced S30 extract from independently grown cells. b, Activities of the same set of lysates as in a on an O-GFP reporter, normalized to their activity on the WT-GFP reporter. Every data point shows the activity of an independently produced S30 extract from independently grown cells. Detailed statistics are shown in Supplementary Data 3. c, The same dataset as in b, represented as a heatmap for ease of comparison. d, Activity of lysates containing a mixture of host and O-stapled ribosomes on the WT-GFP reporter. Every data point shows independently measured activities of O-stapled ribosome variants in independently prepared S30 extracts. e, Activity of the same set of the lysates as in d on the O-GFP reporter in the presence of 10 μM spectinomycin and 50 μM erythromycin, normalized to their activity on WT-GFP. Data points are independently measured activities of O-stapled ribosome variants in independently prepared S30 extracts. Detailed statistics are given in Supplementary Data 4. f, The same dataset as in e, represented as a heatmap for ease of comparison. In a, b, d and e, the error bars show ± s.d., the grey bar shows the mean of the number (n) of independent replicates. Values for n are given in the Methods.

Extended Data Figure 6. In vitro translation activity of O-stapled ribosome variants upon inhibition of native ribosome subunit.

This figure uses the same dataset as in Fig. 2g, and shows the in vitro translation of T7-O-GFP in S30 extracts containing different O-stapled ribosome variants in the presence of 10 μM spectinomycin and 50 μM erythromycin (which inhibit contributions to translation from endogenous subunits). The dots indicate individual data for each tested O-stapled ribosome, and the grey bars show means, for the number of independent replicates given in the Methods. O-d2d8 is highlighted in blue, and the error bars indicate ± s.d.

Extended Data Figure 7. Genomically encoded stapled ribosomes.

a, Colony PCR products reflect the genomic exchanges seen in E. coli strains with a genomically encoded, stapled ribosome rRNA operon integrated by ribo-REXER. Top, direct amplification of the genomic region upstream of the rrnE locus. Integration of the landing site (SacB/CAT) to create the strain SQ110CAT-SacB increases the length of the region upstream of rrnE from 1.3 kb to 3.5 kb. After ribo-REXER, this cassette is lost again, leading to a 1.3-kb band. Bottom, amplification from nucleotide 2,630 of 23S to the rrnE terminator region shows integration of the PheS*/HygR cassette after integration of the wild-type rrnB operon, indicated by ‘integration cassette wt’. Integration of a stapled-ribosome cassette increases the length of the PCR product further, as it includes the 16S 3′ and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, leading to the bands indicated by ‘integration cassette stapled’. The experiment was performed once. b, Denaturing RNA gel electrophoresis reveals the expression of rRNA (around 4,500 nucleotides) from intact stapled ribosomes as the predominant RNA species in all strains. The experiment was performed once. c, Growth rates of strains after successful ribo-REXER. WT describes the integration of a non-stapled rrnB operon. For statistics, see Methods. d, Denaturing RNA gel electrophoresis shows the expression of rRNA from intact stapled ribosomes (around 4,500 nucleotides) as the predominant RNA species in all evolved Δ6 d2d8 strains. The experiment was performed once. e, Sucrose gradient analyses of stapled ribosomes isolated from cells under ribosome-associating conditions (10 mM MgCl2); the experiments were repeated three times with similar results. For source data regarding gels, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 8. Purification of the d2d8 stapled ribosome and structural determination by cryo-EM.

a, Isolation of the d2d8 stapled ribosome on a sucrose gradient for cryo-EM. Fractions corresponding to the middle of the 70S peak (grey shading) were collected and used in structural studies. The inset shows RNA agarose gel analysis of the stapled ribosome at the different purification stages (30S extract preparation and salt wash) as well as the combined 70S fraction sample. The arrow indicates the position of the stapled rRNA. For source data regarding gels, see Supplementary Fig. 1. The data represent n = 2 independent preparations. b, Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve, calculated between independent half-maps. The resolution is estimated from the map-to-map correlation at FSC = 0.143 (for a detailed description, see Extended Data Table 1). The electron-microscopy map is coloured according to local resolution. c, Workflow showing the three-dimensional classification and refinement of cryo-EM particles.

Extended Data Figure 9. Selection of O-ribosome variants competent in translation of polyproline sequences.

a, PCR characterization of an E. coli TOP10 Δefp strain. PCR was carried out, using the indicated primer pairs (128/144 or 128/129), on genomic DNA from a TOP10 strain with intact efp, or a strain in which the efp locus was disrupted by a hygromycin-B-resistance gene (hph). For source data regarding gels, see Supplementary Fig. 1. The experiment was performed twice. b, Cell-growth assay, showing the translation activity of O-d2d8 on O-(P)n-CAT reporters in wild-type (+) or Δefp (−) E. coli TOP10 cells and with varying concentrations of chloramphenicol. The experiment was performed once. c, Activity of the PTC-library hits and the parental O-d2d8 ribosome on p15A-O-(P)4-GFP and p15A-O-(P)7-GFP reporters in E. coli TOP10 Δefp cells. n = 3 biological replicates; error bars indicate ± s.d. d, Translation activity of exit-tunnel library hits in the absence of proline-rich sequences. p15A-O-GFP was used as a reporter. n = 7 biological replicates; error bars indicate ± s.d. e, GFP fluorescence resulting from translation of O-(P)4-GFP in E. coli TOP10 Δefp cells. n = 3 biological replicates; error bars indicate ± s.d. f, As for e, except that the activity of the evolved mutants was tested on an O-(P)7-GFP reporter in E. coli with and without efp. n = 3 biological replicates; error bars represent ± s.d. g, Mutations in both the PTC and the exit tunnel are required to confer on O-d2d8 the ability to translate O-(P)4-GFP and O-(P)7-GFP in TOP10 Δefp cells. O-d2d8PTC-36 and O-d2d8ET-5 contain selected mutations in the PTC and the exit tunnel respectively; O-d2d8-5 contains mutations in both. See Supplementary Data 12 for details on mutations. n = 6 biological replicates; error bars represent ± s.d. h, Electrospray ionization spectra of O-(P)7-GFP synthesized by O-d2d8-5 in Δefp E. coli. This experiment was performed once.

Extended Data Table 1. Collection, refinement and validation of cryo-electron-microscopy data.

| 70S d2d8 stapled (EMDB-0261) (PDB-6HRM) |

|

|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | |

| Magnification | 134615x |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 |

| Electron exposure (e–/Å2) | 26.85 |

| Defocus range (μm) | -2.0 to -3.5 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.06 |

| Symmetry imposed | none |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 306214 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 94371 |

| Map resolution (Å) FSC threshold |

3.0 0.143 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 2.2-8.8 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial model used (PDB code) | 5MDZ |

| Model resolution (Å) FSC threshold |

3.1 0.143 |

| Model resolution range (Å) | 2.6-7.1 |

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | -78.8 |

| Model composition Non-hydrogen atoms Protein residues Nucleic acid residues Ligands |

145181 6131 4563 453 |

|

B factors (Å2) Protein RNA |

86.4 55.1 |

| R.m.s. deviations Bond lengths (Å) Bond angles (°) |

0.008 1.004 |

| Validation MolProbity score Clashscore Poor rotamers (%) |

1.45 2.96 0.47 |

| Ramachandran plot Favored (%) Allowed (%) Disallowed (%) |

94.78 5.16 0.05 |

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC; grants MC_U105181009 and MC_UP_A024_1008), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC; grant BB/M000842/1, for automation) and the European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant (grant SGCR), all to J.W.C. S.D.F. was supported by a fellowship from Kings College, Cambridge. C.D.R. was supported by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship, and supported in the laboratory of V. Ramakrishnan by the MRC (grant MC_U105184332), the Wellcome Trust (grant WT096570), the Louis-Jeantet Foundation and the Agouron Institute.

Footnotes

Data availability

The cryo-EM structure of d2d8 can be found under the PDB accession code 6HRM and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank accession number EMD-0261. Genome sequences for the strains created here are provided in Supplementary Tables 5–10. All other datasets generated and analysed here are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

W.H.S. developed riboREXER and automated parallel evolution, and analysed the resulting data. Z.T. prepared samples for electron microscopy, developed the orthogonal in vitro translation systems and analysed the resulting data. Z.T. also generated the O-stapled ribosome library, with the assistance of W.H.S., and performed and analysed the polyproline translation experiments. C.U. developed the MS2 pulldown experiments, performed the pulldowns, and analysed the data using samples prepared with the assistance of W.H.S. C.D.R performed cryo-EM and data analysis. S.D.F. cloned O-stapled ribosomes and performed some initial analysis. W.H.S. characterized the activities of O-stapled ribosomes, with assistance from C.U. and Z.T. W.H.S., Z.T., C.U. and J.W.C. wrote the paper, with input from all authors.

Author Information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Rackham O, Chin JW. A network of orthogonal ribosome x mRNA pairs. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:159–166. doi: 10.1038/nchembio719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang K, Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Evolved orthogonal ribosomes enhance the efficiency of synthetic genetic code expansion. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:770–777. doi: 10.1038/nbt1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann H, Wang K, Davis L, Garcia-Alai M, Chin JW. Encoding multiple unnatural amino acids via evolution of a quadruplet-decoding ribosome. Nature. 2010;464:441–444. doi: 10.1038/nature08817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang K, et al. Optimized orthogonal translation of unnatural amino acids enables spontaneous protein double-labelling and FRET. Nat Chem. 2014;6:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried SD, Schmied WH, Uttamapinant C, Chin JW. Ribosome Subunit Stapling for Orthogonal Translation in E. coli. Angew Chem Weinheim Bergstr Ger. 2015;127:12982–12985. doi: 10.1002/ange.201506311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orelle C, et al. Protein synthesis by ribosomes with tethered subunits. Nature. 2015;524:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature14862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin JW. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code. Nature. 2017;550:53–60. doi: 10.1038/nature24031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voorhees RM, Ramakrishnan V. Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:203–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-113009-092313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Triman KL, Peister A, Goel RA. Expanded versions of the 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA mutation databases (16SMDBexp and 23SMDBexp) Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:280–284. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitahara K, Suzuki T. The ordered transcription of RNA domains is not essential for ribosome biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2009;34:760–766. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szewczak AA, Cech TR. An RNA internal loop acts as a hinge to facilitate ribozyme folding and catalysis. RNA. 1997;3:838–849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakatogawa H, Ito K. The ribosomal exit tunnel functions as a discriminating gate. Cell. 2002;108:629–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez-Laslop N, Ramu H, Klepacki D, Kannan K, Mankin AS. The key function of a conserved and modified rRNA residue in the ribosomal response to the nascent peptide. EMBO J. 2010;29:3108–3117. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett OP, Chin JW. Evolved orthogonal ribosome purification for in vitro characterization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2682–2691. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youngman EM, Green R. Affinity purification of in vivo-assembled ribosomes for in vitro biochemical analysis. Methods. 2005;36:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vester B, Douthwaite S. Macrolide resistance conferred by base substitutions in 23S rRNA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.1-12.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigmund CD, Ettayebi M, Morgan EA. Antibiotic resistance mutations in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4653–4663. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.11.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, et al. Defining synonymous codon compression schemes by genome recoding. Nature. 2016;539:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature20124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan S, Skovgaard O, McLaughlin RE, Buurman ET, Squires CL. Markerless Escherichia coli rrn Deletion Strains for Genetic Determination of Ribosomal Binding Sites. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:2555–2557. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.022301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James NR, Brown A, Gordiyenko Y, Ramakrishnan V. Translational termination without a stop codon. Science. 2016;354:1437–1440. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huter P, et al. Structural Basis for Polyproline-Mediated Ribosome Stalling and Rescue by the Translation Elongation Factor EF-P. Mol Cell. 2017;68:515–527 e516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doerfel LK, et al. Entropic Contribution of Elongation Factor P to Proline Positioning at the Catalytic Center of the Ribosome. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12997–13006. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlov MY, et al. Slow peptide bond formation by proline and other N-alkylamino acids in translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:50–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809211106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doerfel LK, et al. EF-P is essential for rapid synthesis of proteins containing consecutive proline residues. Science. 2013;339:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1229017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ude S, et al. Translation elongation factor EF-P alleviates ribosome stalling at polyproline stretches. Science. 2013;339:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1228985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maini R, et al. Protein Synthesis with Ribosomes Selected for the Incorporation of beta-Amino Acids. Biochemistry. 2015;54:3694–3706. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melo Czekster C, Robertson WE, Walker AS, Soll D, Schepartz A. In Vivo Biosynthesis of a beta-Amino Acid-Containing Protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5194–5197. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maini R, et al. Ribosome-Mediated Incorporation of Dipeptides and Dipeptide Analogues into Proteins in Vitro. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11206–11209. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedkova LM, Fahmi NE, Golovine SY, Hecht SM. Construction of modified ribosomes for incorporation of D-amino acids into proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15541–15551. doi: 10.1021/bi060986a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terasaka N, Hayashi G, Katoh T, Suga H. An orthogonal ribosome-tRNA pair via engineering of the peptidyl transferase center. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:555–557. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sachdeva A, Wang K, Elliott T, Chin JW. Concerted, rapid, quantitative, and site-specific dual labeling of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7785–7788. doi: 10.1021/ja4129789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Naismith JH. An efficient one-step site-directed deletion, insertion, single and multiple-site plasmid mutagenesis protocol. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:91. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peabody DS, Ely KR. Control of translational repression by protein-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]