Summary

Hyperactivity and disturbances of attention are common behavioral disorders whose underlying cellular and neural circuit causes are not understood. We report the discovery that striatal astrocytes drive such phenotypes through a hitherto unknown synaptic mechanism. We found that striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) triggered astrocyte signaling via GABAB receptors. Selective chemogenetic activation of this pathway in striatal astrocytes in vivo resulted in acute behavioral hyperactivity and disrupted attention. Such responses also resulted in up-regulation of the synaptogenic cue thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) in astrocytes, increased excitatory synapses, enhanced corticostriatal synaptic transmission, and increased MSN action potential firing in vivo. All of these changes were reversed by blocking TSP1 effects. Our data identify a form of bidirectional neuron-astrocyte communication, and demonstrate that acute reactivation of a single, latent astrocyte synaptogenic cue alters striatal circuits controlling behavior, revealing astrocytes and the TSP1 pathway as therapeutic targets in hyperactivity, attention deficit and related psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: hyperactivity, attention deficit, astrocyte, behavior, striatum, microcircuit, thrombospondin, gabapentin

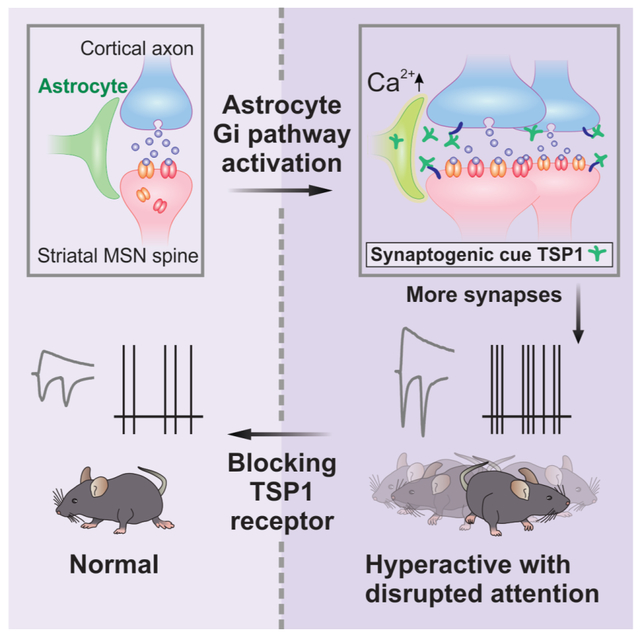

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Bi-directional communication between striatal neurons and astrocytes drive acute behavioral hyperactivity and disrupted attention

Introduction

Hyperactivity and disturbances of attention are common behavioral disorders (DSM-5, 2013; Fayyad et al., 2007; Polanczyk et al., 2007) whose underlying causes are unknown and which lack adequate treatment (Curatolo et al., 2010; de la Peña et al., 2018). Such disorders involve dysfunctions in the striatum based on imaging studies in humans (Cubillo et al., 2012; Riva et al., 2018). The striatum is the largest nucleus of the basal ganglia, a group of interconnected subcortical nuclei involved in movement, repetitive behaviors, obsessions, habits, tics and diverse neuropsychiatric conditions (Graybiel, 2008). In the current study, we report the unexpected discovery that latent synaptogenic cues derived from striatal astrocytes drive behavioral hyperactivity with disrupted attention in adult mice.

Initially documented over a century ago, astrocytes represent about 40% of all brain cells. They are the most numerous type of glia and tile the entire central nervous system (Barres, 2008). During development, astrocytes provide important cues to regulate synapse formation and removal (Allen and Lyons, 2018), whereas in adults the finest astrocyte processes from these “bushy” cells continue to contact neurons, synapses, blood vessels and other glial cells. In these locations, astrocytes mediate multiple active and homeostatic functions (Attwell et al., 2010; Khakh and Sofroniew, 2015; Volterra et al., 2014). Astrocytes also display CNS area specific properties and functions (Chai et al., 2017; Haim and Rowitch, 2017; Molofsky et al., 2014). Despite these advances, the mechanisms of astrocyte-neuron signaling, its effects on the functions of intact neural circuits, their behavioral outputs and their contributions to brain diseases remain to be fully elucidated.

Replete with molecularly defined astrocytes, the striatum represents an important circuit to explore astrocyte biology within adult mice (Chai et al., 2017; Kelley et al., 2018). As the major input nucleus of the basal ganglia, the striatum integrates converging excitatory and inhibitory signals from numerous parts of the brain and is involved in action selection and motor function (Graybiel, 2008). We used several recently developed striatal astrocyte selective genetic, transcriptomic, imaging, behavioral and electrophysiology approaches (Bakhurin et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2017; Srinivasan et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018) to interrogate the roles of bidirectional neuron-astrocyte interactions in the function of striatal microcircuits in vivo. We discovered an unexpected mechanism for astrocyte-neuron mediated synaptic plasticity, a hitherto unknown role for astrocytes in hyperactivity and disrupted attention phenotypes and potential therapeutic strategies within astrocytes to treat such psychiatric diseases.

Results

The results of statistical comparisons, n numbers and P values are shown in the figure panels or figure legends with the relevant average data. When the average data are reported in the text, the statistics are also reported there. However, all statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1 for every experiment.

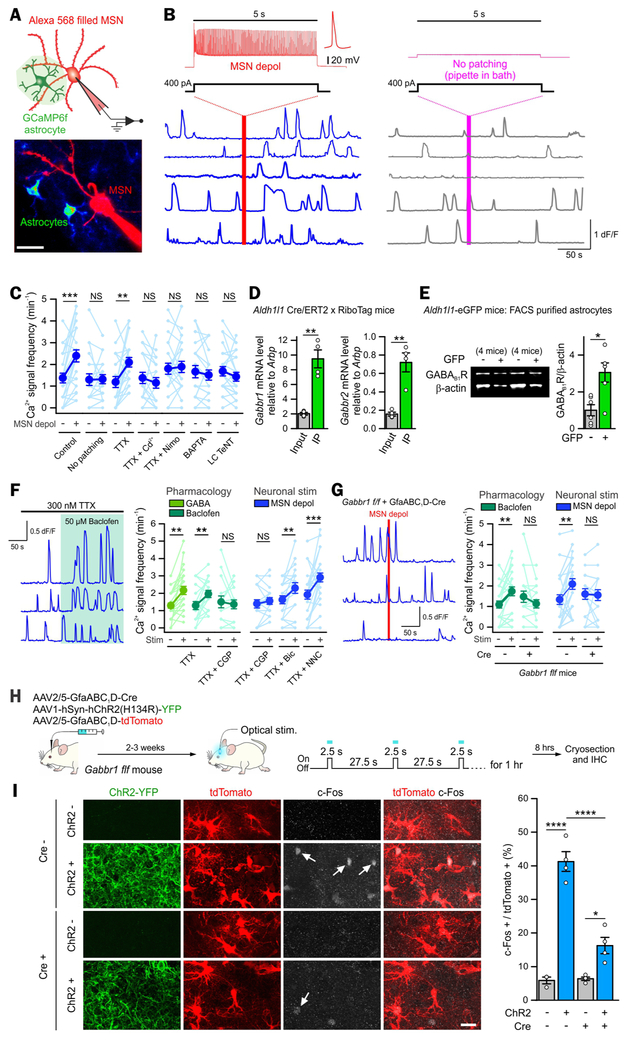

Striatal MSN-to-astrocyte signaling via GABA

We expressed the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f (Chen et al., 2013) in striatal astrocytes (Srinivasan et al., 2016) and depolarized medium spiny neurons (MSNs) to physiological upstate-like membrane potential transitions (Wilson and Kawaguchi, 1996) via whole-cell patch-clamp (Figure 1A-C). MSN depolarization by ~20–30 mV resulted in action potential (AP) firing and significantly increased the frequency of Ca2+ signals in nearby astrocytes (<50 μm away from MSN somata or dendrites) from 1.4 ± 0.2 to 2.4 ± 0.3 min−1 (Figure 1B,C; n = 24 astrocytes, 6 mice, P < 0.001). The amplitude of the Ca2+ signals was unaltered (0.3 ± 0.04 to 0.3 ± 0.04 dF/F; P > 0.05, n = 24 astrocytes, 6 mice), but their duration increased (2.8 ± 0.04 to 4.0 ± 0.4 s; P < 0.01, n = 24 astrocytes, 6 mice) likely reflecting merged events. No change in Ca2+ signals was observed by current injection via an open pipette, indicating that the astrocyte responses were not due to mechanical effects (Figure 1B-C; n = 20 astrocytes, 5 mice). Furthermore, astrocytes responded similarly when either D1 or D2 MSNs were depolarized (Figure S1A-C), likely reflecting developmental maturity in adult mice (Martín et al., 2015) and consistent with anatomical data (Octeau et al., 2018). MSN depolarization-evoked astrocyte Ca2+ signals were resistant to tetrodotoxin (TTX; 300 nM; Figure 1C, n = 21 astrocytes, 5 mice), which blocked all APs (Figure S1F). However, astrocyte Ca2+ signals were abolished by Cd2+ (50 μM, n = 20 astrocytes, 5 mice) and nimodipine (20 μM, n = 23 astrocytes, 4 mice), which both block MSN L-type Ca2+ channels (Bargas et al., 1994; Carter and Sabatini, 2004) (Figure 1C). The depolarization-evoked astrocyte Ca2+ signals were also blocked by MSN dialysis with the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (10 mM, n = 21 astrocytes, 4 mice) or with the light-chain of tetanus toxin (LC-TeNT; 1 μM; Figure 1C; n = 24 astrocytes, 5 mice), which blocks vesicular release. Together with imaging of MSN activity during upstate-like heightened excitability (Figure S1D-G), these data show that MSN membrane potential transitions open high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels and cause Ca2+-dependent vesicular release of a substance from MSNs that communicates to nearby astrocytes to cause intracellular Ca2+ elevations.

Figure 1: MSN GABA release activated striatal astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in situ and in vivo.

(A) Whole-cell recording from MSNs (filled with Alexa 568) and imaging from nearby cytosolic GCaMP6f expressing astrocytes.

(B) MSN depolarization to upstate like levels for 5 s (117 ± 11 APs evoked) increased the frequency of astrocyte Ca2+ signals (blue traces, 5 representative cells). This did not occur without patching (gray traces, 5 representative cells).

(C) Graph of astrocyte Ca2+ signal frequency before and after MSN depolarization in control and various experimental configurations (n = 18-24 astrocytes from 4-6 mice per condition).

(D-E) Striatal astrocyte specific qPCR (D, n = 4 mice) and Western blotting (E, n = 6 experiments from 20 mice) revealed GABAB receptor enrichment in astrocytes.

(F) Left, Baclofen bath application increased the frequency of astrocyte Ca2+ signals (3 representative cells). The right summary graph shows astrocyte Ca2+ signal frequency before and after drug application or MSN depolarization in various experimental configurations (n = 15-30 astrocytes from 4-5 mice).

(G) Left, astrocyte Ca2+ signals (3 representative cells) from the striatum in which Gabbr1 was deleted. The right summary graphs show astrocyte Ca2+ signal frequency before and after baclofen application or MSN depolarization in Gabbr1 f/f mice with or without Cre (n = 18-25 astrocytes from 4 mice).

(H) Cartoon illustrating AAV microinjection into the dorsal striatum to delete Gabbr1 in astrocytes by delivering AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-Cre and the method used to activate neurons in vivo with optical stimulation following expression of ChR2(H134R). tdTomato was expressed in order to visualize astrocytes.

(I) ChR2-based striatal neuron excitation in vivo resulted in c-Fos expression in astrocytes, which was attenuated by Gabbr1 deletion in astrocytes (n = 4 mice).

Paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed ranks test between before (basal) and after stimulation (C, F, G). Paired t-test (D, E). Two-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (I). Scale bars, 20 μm (A, I). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001, **** indicates P < 0.0001, NS indicates not significantly different. See also Fig S1-3.

Since MSNs are GABAergic, we explored roles for GABA in MSN-to-astrocyte signaling. A role for GABA was supported by RNA-seq (Chai et al., 2017) and qPCR data showing enrichment of GABAB receptor Gabbr1 and Gabbr2 mRNAs in striatal astrocytes (Figure 1D; 4 mice). GABAB receptor type-1 (GB1R) proteins (gene: Gabbr1) were abundant in striatal astrocytes isolated by FACS (Chai et al., 2017) from Aldh1l1-eGFP mice (Figure 1E; n = 6; 20 mice). Furthermore, consistent with functional expression of GABA receptors in astrocytes, bath application of GABA (300 μM, n = 24 astrocytes, 5 mice) and the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (50 μM, n = 20 astrocytes, 5 mice) increased astrocyte Ca2+ signals (Figure 1F, P < 0.01). The effect of baclofen was blocked by the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP55845 (10 μM, n = 15 astrocytes, 4 mice; Figure 1F), which also blocked the MSN-depolarization evoked astrocyte Ca2+ signals (Figure 1F, n = 18 astrocytes, 4 mice). Astrocyte Ca2+ responses evoked by baclofen and by MSN-depolarization were abolished (Figure 1G) in mice in which GB1Rs were deleted from the striatum (Figure 1G & S2A-B).

We explored if MSN depolarization stimulated astrocytes via GABA in vivo. We expressed ChR2(H134R) in MSNs and assessed immediate early gene (c-Fos) expression in astrocytes following optical stimulation. We detected GB1R-dependent c-Fos expression in astrocytes following MSN ChR2(H134R) stimulation: the optically stimulated increase in c-Fos expression within astrocytes was significantly reduced when GB1R was deleted (Figure 1H-I; 4 mice). Ca2+ signals represent a readout of diverse astrocyte G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Porter and McCarthy, 1997). GB1Rs couple to Gi proteins, which in astrocytes (Haustein et al., 2014) leads to Ca2+ elevations by activation of phospholipase C, which we confirmed for the GABAB receptor responses (Figure S2C,D). Furthermore, MSNs intermingle extensively with astrocytes (Chai et al., 2017; Octeau et al., 2018) and their dendrites were closely juxtaposed with astrocyte somata and processes (Figure S2E,F; n = 26 images, 4 mice), providing the proximity for MSN released GABA to stimulate astrocyte GABA receptors. We hypothesize that MSNs release GABA from their dendrites to mediate astrocyte responses: dendritic release of neurotransmitters including GABA is known (Waters et al., 2005). It has also been suggested that hippocampal astrocytes respond to glutamate, ATP and/or endocannabinoid release from dendrites (Bernardinelli et al., 2011; Navarrete and Araque, 2008) via release mechanisms that are not yet delineated. Taken together, our data provide strong evidence for MSN-to-astrocyte signaling mediated by neuronal GABA release acting on astrocyte GABAB receptors (Figures 1, S1-S2).

We comment on our use of mice carrying a floxed (f/f) Gabbr1 allele and the use of AAVs. In the preceding sections, we deleted GB1R from astrocytes using striatal AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-Cre microinjections. We could identify astrocytes based on their bushy morphologies as well as by marker expression (Figure S2A,B), and we could therefore easily monitor the consequences of deleting GB1Rs in single cell evaluations (Figure 1G,I). However, as reported in Fig S3A-D and the associated legend, we could not use Gabbr1 f/f mice for astrocyte-selective evaluations of more complex phenomena such as animal behavior. To explore the consequences of GB1R Gi-pathway activation within astrocytes, in the following section we used chemogenetic approaches that have been fully validated for astrocyte selectivity (Adamsky et al., 2018; Chai et al., 2017).

Striatal astrocyte Gi pathway activation in vivo

GABAB receptors exist in multiple brain cells including neurons, therefore GABAB receptor agonists cannot be used in vivo to interrogate astrocyte GABAB receptor mediated physiology. Furthermore, currently available genetic strategies cannot selectively delete GABAB receptors only from striatal astrocytes in the adult brain (Figure S3A-D). Hence, to specifically explore the consequences of striatal astrocyte GABAB Gi pathway activation in vivo, which is necessary to interpret behavioral effects, we expressed hM4Di Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) (Roth, 2016) using established methods that result in selective expression within 84 ± 3% of striatal astrocytes (Chai et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018) using AAV (Figure S3E-G; 4 mice). hM4Di and GCaMP6f were also co-expressed so that the consequences of hMD4i activation could be imaged (Figure 2A, n = 34 mice). We confirmed that intrastriatal microinjection of AAV2/5-delivered cargo was astrocyte selective and restricted to the striatum, although there was a little expression proximal to the needle tract in astrocytes of the cortex and sometimes of the corpus callosum (Figure S3E). We suspect such expression occurred in all past studies employing viruses, as it is impossible to reach subcortical brain structures without advancing the needle through the overlying tissue: all studies employing microinjections (including ours) need to be interpreted with this anatomical caveat in mind.

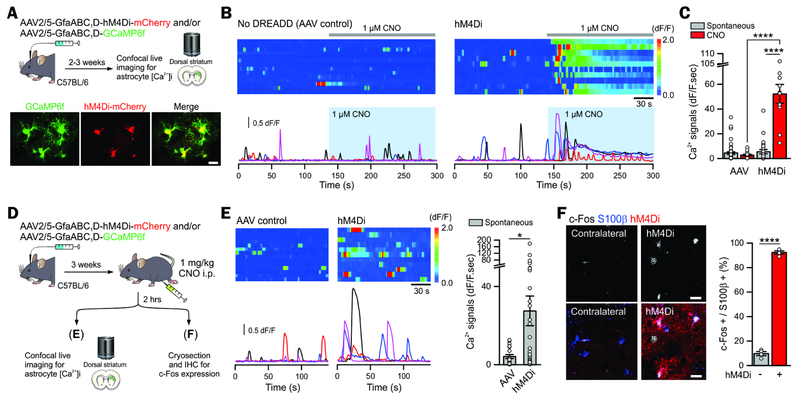

Figure 2: Astrocyte-specific Gi pathway activation by a Gi-DREADD hM4Di.

(A) Cartoon illustrating AAVs used for expressing GCaMP6f with and without mCherry-fused hM4Di in astrocytes in the dorsal striatum. The lower images show GCaMP6f and hM4Di-mCherry expressing astrocytes in striatal slices were colocalised (Chai et al., 2017).

(B-C) Kymographs and ΔF/F traces of astrocyte Ca2+ responses evoked by bath application of 1 μM CNO in control AAV injected and hM4Di injected mice. The bar graph shows the CNO-evoked integrated area of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in the hM4Di group, and in the controls (n ≥ 11 cells from ≥ 3 mice).

(D) Schematic illustrating 1 mg/kg CNO was administrated i.p. in vivo 2 hr prior to harvesting brains for imaging.

(E) Kymographs and ΔF/F traces of astrocyte Ca2+ responses in control and hM4Di groups. The bar graphs summarize the integrated areas of the spontaneous Ca2+ signals in hM4Di and control mice that received CNO i.p. 2 hr prior (n ≥ 21 astrocytes from ≥ 3 mice). These data show that a single in vivo dose of CNO evoked a long lasting increase in astrocyte Ca2+ signaling.

(F) hM4Di activation with in vivo CNO administration increased c-Fos expression in striatal S100β positive astrocytes (4 mice).

Scale bars, 20 μm (A, F). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. * indicates P < 0.05, **** indicates P < 0.0001. See also Fig S3.

In brain slices from control mice, the hM4Di agonist clozapine-N-oxide (CNO at 1 μM) had no effect on astrocyte Ca2+ signals (Figure 2B,C; Movie S1; n = 14 astrocytes, 4 mice). However, in brain slices from mice expressing hM4Di in striatal astrocytes, CNO evoked significant astrocyte Ca2+ elevations (Figure 2B,C, Movie S2; n = 11 astrocytes, 4 mice, P < 0.0001). These were similar to those mediated by GABAB receptors (Figure 1F) and other endogenous GPCRs (the CNO-evoked response area was 52.1 ± 8.4 dF/F.sec, whereas that for phenylephrine (Srinivasan et al., 2016) acting on α1 receptors was 62.5 ± 8.8 dF/F.sec; n = 11 & 12 astrocytes, n = 4 & 3 mice). Furthermore, 2 hrs after acute in vivo administration of CNO (Alexander et al., 2009), striatal astrocytes in brain slices displayed significantly elevated spontaneous Ca2+ signals (Figure 2E,F; n = 21 & 28 astrocytes, n = 3 & 4 mice). in vivo hM4Di activation by CNO increased c-Fos expression in striatal astrocytes (Figure 2F; n = 4 mice). Thus, CNO stimulated hM4Di-expressing striatal astrocytes to a level similar to that mediated by endogenous GPCRs (Porter and McCarthy, 1997; Shigetomi et al., 2016) recalling data with exogenous and endogenous GABA (Figure 1).

Hyperactivity and disrupted attention following striatal astrocyte Gi pathway stimulation

We prepared mice with bilateral expression of hM4Di in striatal astrocytes and assessed behavior 2 hrs after intraperitoneal (i.p.) CNO (Alexander et al., 2009) (Figure 3). Since CNO can have off-target effects (Gomez et al., 2017), we performed three controls for every behavior experiment. We prepared mice with a control AAV (tdTomato) and administered either vehicle or CNO (i.e. “AAV + Veh” and “AAV + CNO” groups in Figure 3A,B). We also prepared hM4Di expressing mice, which received either vehicle or CNO (“hM4Di + Veh” and “hM4Di + CNO” groups in Figure 3A,B). hM4Di + CNO mice showed heightened ambulation in the open-field when compared to the AAV + CNO control, or to the hM4Di + Veh and AAV + Veh groups (Figure 3B, C). There were no differences between groups on the accelerating rotarod that we could ascribe to altered motor function (Figure S4A). Interestingly, the hM4Di + CNO mice showed heightened rearing behavior on this task (Figure S4B) increasing their tendency to fall off the rotarod on Day 1. However, after multiple days of testing there were no significant differences between the groups (Figure S4A). There were also no differences in the footprint assay, showing that the mice had intact motor co-ordination (Figure S4C). Consistent with an overall hyperlocomotion phenotype disturbing the bedding, hM4Di + CNO mice buried significantly more marbles (Figure S4D).

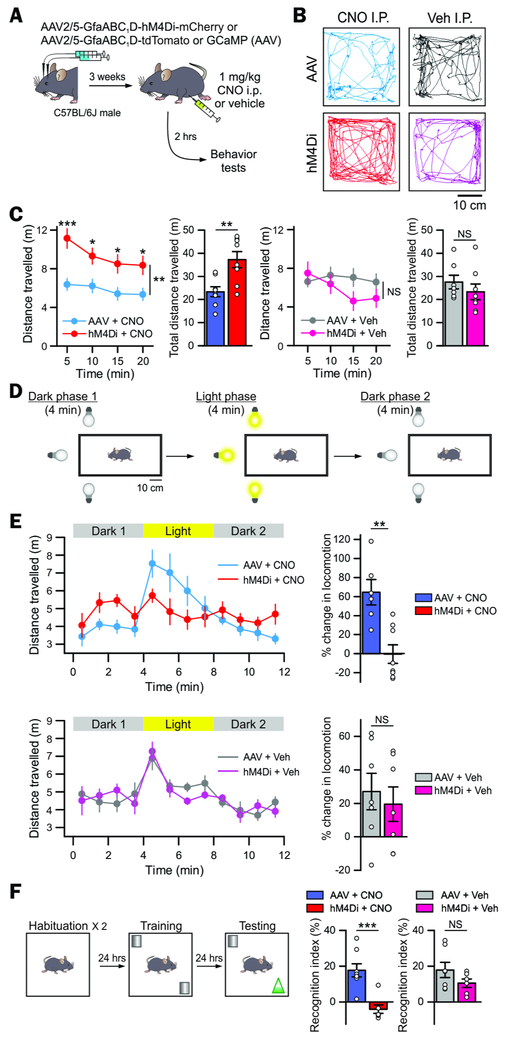

Figure 3: Astrocyte-specific Gi pathway activation in vivo induced hyperactivity and disrupted attention.

(A) Cartoon illustrating the AAV2/5 reagents and approaches for selectively expressing hM4Di-mCherry or tdTomato (as a control AAV) bilaterally in striatal astrocytes. Once such mice were prepared, behavior was assessed 3 weeks later and 2 hrs after intraperitoneal administration of 1 mg/kg CNO or vehicle.

(B) The representative open-field activity tracks show the 4 experimental groups used in behavioral analyses to control for potential off target effects of CNO and to control for AAV microinjections.

(C) Distance travelled by the mice over 20 min in an open field chamber, divided into 5 min epochs and also pooled over 20 mins for the 4 experimental groups.

(D) Cartoon of the modified open field test with a light stimulus.

(E) Distance travelled in the modified open field chamber before, during and after light stimulation (in 1 min epochs). Notably, the hM4Di + CNO group showed no significant increase in ambulation in response to light stimulation, whereas all the other groups did so.

(F) Behavioral layout of the novel object recognition task for the 4 experimental groups. No significant difference was found between hM4Di + Veh and AAV + Veh groups across all the behavioral tests, but there were clear differences between the AAV + CNO and the hM4Di + CNO groups (B-F).

Data: mean ± s.e.m. Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001, NS indicates not significantly different. See also Fig S3-4.

In humans, hyperactivity is often associated with a lack of attention to environmental stimuli (e.g. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, ADHD) (DSM-5, 2013). To explore this association in CNO-treated hM4Di mice we used a well-characterized modified open field task (Godsil et al., 2005a; Godsil and Fanselow, 2004; Godsil et al., 2005b) (Figure 3D). In this initially dark open field, onset of a localized visual stimulus drives investigatory activity. hM4Di+CNO mice were initially hyperactive in the dark relative to AAV+CNO controls (Figure 3E upper panel). However, unlike controls, which showed pronounced investigatory response to the light, hM4Di+CNO mice appeared oblivious to stimulus onset. Again, the hM4Di+CNO mice did not react to light termination while control mice decreased their activity to pre light levels. hM4Di+Veh mice were indistinguishable from controls (Figure 3E lower panel). Furthermore, in the novel object recognition task, hM4Di + CNO mice spent significantly less time with the novel object as compared to controls (Figure 3F, 6–8 mice). Overall, activation of an astrocyte-specific Gi pathway produced inattentive hyperactivity in mice reminiscent of human ADHD.

Astrocyte Gi pathway augmented MSN excitatory synapses and increased AP firing

The striatum is involved in common hyperactivity disorders in humans (Cubillo et al., 2012; Riva et al., 2018), which lack mechanistic understanding, but must involve synaptic and circuit dysfunctions. To explore such possibilities, we evaluated synaptic mechanisms accompanying hyperactivity phenotypes following acute striatal astrocyte Gi-pathway activation in vivo (Figure 3). In sagittal brain slices, we stimulated glutamatergic corticostriatal axons to assess fast excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) onto MSNs in the four experimental groups (Figure 4A,B). We recorded AMPA receptor-mediated evoked EPSCs, paired-pulse responses (at −70 mV) and NMDA receptor-mediated evoked EPSCs (at +40 mV; Figure 4A). We found no significant changes in any of these metrics for the three control groups (AAV + Veh, AAV + CNO, hM4Di + Veh). However, in the hM4Di + CNO group, we detected significantly potentiated AMPA and NMDA EPSCs (Figure 4A,B), with no change in paired-pulse or AMPA/NMDA ratios (Figure 4A,B), arguing against altered neurotransmitter release probability or D-serine levels. For the experiments shown in Figure 4AB, we used the same stimulation for each slice, but we also examined evoked AMPA EPSCs at multiple stimulation intensities (Figure 4C and C’; n = 12–13 MSNs from 4 mice) and found the same results. To our knowledge, the boosting of both AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs is a previously unreported synaptic phenotype mediated by astrocytes, prompting us to explore the underlying mechanisms.

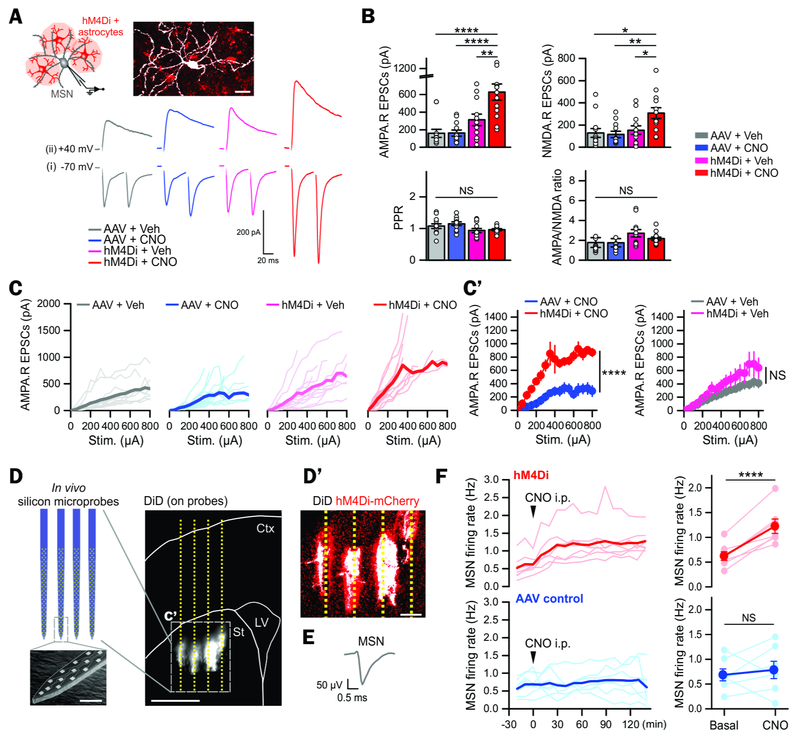

Figure 4: Increased corticostriatal excitatory synaptic transmission and elevated MSN firing in vivo by acute astrocyte Gi pathway activation.

(A) Cartoon illustrating whole-cell patch-clamp recording from an MSN (filled with Biocytin) surrounded by hM4Di-expressing astrocytes. The lower traces show representative traces for evoked AMPA.R EPSCs due to paired stimuli at membrane potentials of −70 mV (i) and for NMDA.R EPSCs due to single stimuli at +40 mV (ii) from the indicated 4 experimental groups.

(B) Summary of multiple experiments such as those illustrated with representative traces in panel A (n = 12-13 MSNs from 4 mice). Notably, the AMPA.R and the NMDA.R EPSC amplitude in the hM4Di + CNO group was greater compared to other control groups, but there was no significant change in PPR and AMPA/NMDA ratios.

(C) The graphs plot the AMPA EPSC amplitudes with varying stimulation intensities delivered to the cortico-striatal pathway in brain slices from the indicated 4 experimental groups. Plots in light colors show individual data from each MSN and those in dark colors and thicker lines indicate averaged data (n = 12-13 MSNs from 4 mice). The subpanel C’ shows average plots from indicated 4 experimental groups.

(D) Illustration and scanning electron microscope image of the silicon microprobes used to record neuronal activity in vivo. The probes were coated with DiD fluorescent dye, which was deposited at the implantation site, allowing reconstruction of their position post hoc. The subpanel D’ shows that the microprobes (indicated in white by the dye) were positioned near hM4Di-expressing astrocytes (indicated in red owing to mCherry).

(E) Representative extracellularly recorded MSN AP.

(F) The graphs plot the MSN firing rate before and following i.p. CNO administration to AAV control mice and to hM4Di mice. The scatter graphs on the right summarize such experiments. Notably, MSN firing rate was significantly increased 120 min after CNO i.p. administration in hM4Di mice, but not in control mice (n = 7 mice).

Scale bars, 20 μm in panel (A), 1 mm in the large image of panel D, 10 μm in the small image of the microprobes in D, and 200 μm in panel D’. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, **** indicates P < 0.0001, NS indicates not significantly different. See also Fig S4.

To determine how astrocyte Gi-pathway activation affected striatal microcircuits in vivo, we used silicon probes (Figure 4D) to record from MSNs in awake head-fixed mice before, during and after acute i.p. CNO administration (Bakhurin et al., 2016). We recorded from probes inserted near hM4Di-expressing astrocytes (Figure 4D’). Extracellular APs were detected and those from MSNs identified by their characteristic waveform duration and baseline firing properties (Bakhurin et al., 2016) (Figure 4E). We recorded 300 units from the AAV + CNO control group and 492 units from the hM4Di + CNO group (7 mice each). Consistent with previously reported striatal neuron type composition, the majority of these units were putative MSNs (~70% of recorded units) with smaller proportions of tonically active neurons (TANs), fast spiking interneurons (FSIs) and unclassified neurons (Figure S4E). Within 30 min of CNO, MSN firing in the hM4Di + CNO group increased, but not in the AAV + CNO control group (Figure 4F). The increase in MSN firing measured from hM4Di + CNO mice stabilized at ~2 hrs post CNO (Figure 4F; P <0.0001), corresponding to the time point when mouse behavior was assessed (Figure 3). Consistent with behavioral observations in Figure 3, CNO significantly increased locomotor activity of the mice on the treadmill in the hM4Di + CNO group (Figure S4G). We detected no change in FSI firing rate (Figure S4F). We explored whether an increase in MSN firing in vivo may reflect intrinsic MSN excitability following astrocyte Gi pathway activation. However, we found no evidence for this from whole-cell current-clamp measurements of MSN excitability in brain slices (Figure S4H-K). Our data show that acute striatal astrocyte Gi-pathway activation in vivo leads to rapid augmentation of synaptic excitation (Figure 4A-C), and elevated MSN firing (Figure 4D-F) that accompany behavioral hyperactivity (Figure 3).

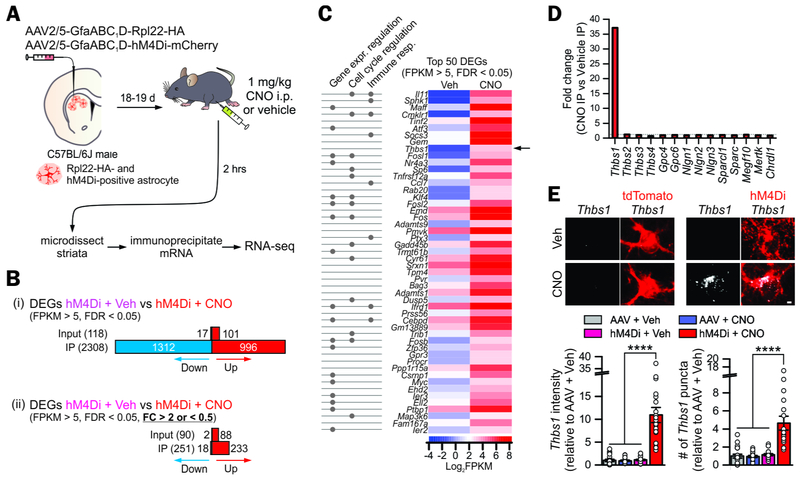

Activation of a synaptogenic cue (TSP1) by the astrocyte Gi pathway

There are no data to indicate the mechanism(s) by which Gi pathway activation in striatal astrocytes may lead to hyperlocomotion with disrupted attention, potentiated fast excitatory synaptic transmission and elevated firing of MSNs. We therefore performed RNA-seq to explore agnostically the mechanisms that underlie Gi-pathway mediated changes in striatal synapses, circuits and behavior (Figures 1–4). We used recently reported RiboTag AAVs (Yu et al., 2018) to deliver the ribosomal subunit Rpl22-HA to astrocytes that received hM4Di in the dorsal striatum (Figure 5A). In this approach (Chai et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018), we immunoprecipitated astrocyte specific RNA from cells following acute in vivo Gi pathway activation with CNO for 2 hrs and from vehicle controls (Figure 5A; Figure S5A; 4 mice; Supplementary Table 2). We analyzed the RNA-seq data by FPKM (>5) and with a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.05 to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) induced by Gi-pathway activation and identified ~2300 DEGs in the IP samples (Figure 5B). With a >2-fold change cut-off, we identified ~250 DEGs between control and hM4Di + CNO groups (Figure 5B). Fig 5C reports the top 50 altered genes between hM4Di + Veh and hM4Di + CNO groups, along with their proposed functions. Among the top 10, Thbs1 was notable because its gene product, thrombospondin 1 (TSP1), has roles in developmental synapse formation (Christopherson et al., 2005; Crawford et al., 2012; Eroglu et al., 2009). Figure 5D compares the fold-change in Thbs1 and 13 other astrocyte genes implicated in synapse formation or loss. Of these, only Thbs1 was significantly upregulated in the hM4Di + CNO groups by ~ 40-fold (Figure 5D; n = 4 mice). To further explore this, we performed RNAscope mRNA analysis in single cells and found Thbs1 was expressed at low levels within adult astrocytes in all three-control groups, but its expression was increased significantly in the hM4Di + CNO group (Figure 5E; n = 3 mice, P < 0.0001). Thus, Gi-pathway stimulation activates TSP1, a latent synaptic synaptogenic cue in adult mice (Christopherson et al., 2005).

Figure 5: Astrocyte transcriptomes following astrocyte Gi pathway activation revealed Thbs1 upregulation.

(A) Cartoon illustrating AAVs for selectively expressing Rpl22-HA and hM4Di-mCherry in astrocytes in the dorsal striatum via intracranial microinjections for RNA-seq 2 hrs after intraperitoneal administration of 1 mg/kg CNO or vehicle.

(B) The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in RNA-seq, with no fold-change cutoff and with a > 2-fold change cut off.

(C) Heatmaps of FPKM for the top 50 DEGs. Log2(FPKM) ranged from −4 (blue, relatively low expression) to 8 (red, relatively high expression). The proposed functions of the gene based on gene ontology analyses are also shown.

(D) Fold-change of genes implicated in astrocyte-dependent synapse formation and removal.

(E) RNAscope based assessment of Thbs1 mRNA expression in the dorsal striatum of the four experimental groups (n = 20-21 astrocytes from 4 mice per group). Significant upregulation of Thbs1 mRNA was observed in the hM4Di + CNO group.

Scale bars, 2 μm in panel (E). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. **** indicates P < 0.0001. See also Fig S5.

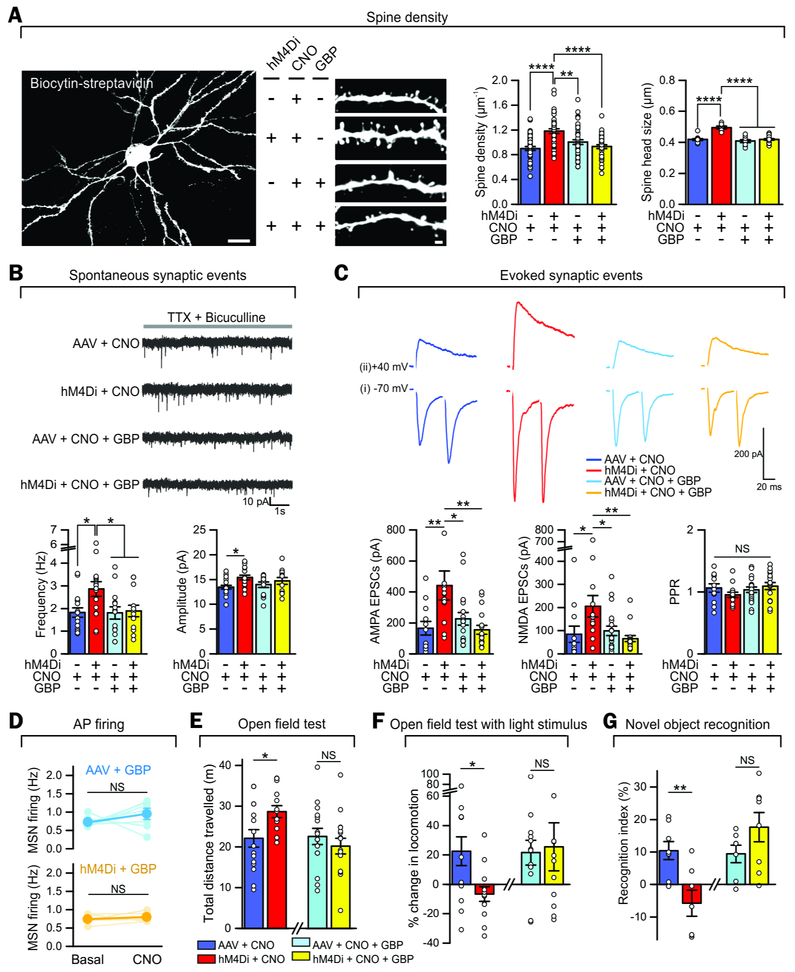

Rescue of astrocyte Gi-pathway mediated cellular, circuit and hyperactivity phenotypes

Gabapentin (GBP) is an antagonist of TSP1 receptor α2δ−1 on neurons and was used to selectively block TSP1 actions in vivo in adult wild-type mice (Crawford et al., 2012; Eroglu et al., 2009), because TSP1 and α2δ−1 deletion mice have quite severe baseline dysfunctions (Crawford et al., 1998; Risher et al., 2018) that vitiate behavioral and synaptic assessments in our experimental design. Using GBP and in support of a causal role for TSP1 in our observations, we measured significantly increased density of dendritic spines in the hM4Di + CNO group relative to the AAV + CNO control group (Figure 6A, P < 0.0001, 39–46 dendritic segments, 4 mice in each group). We also determined how persistent these synaptic effects were. We found that the increased density of dendritic spines in the hM4Di + CNO group was reversible 48 hrs after CNO administration in vivo (Figure S6A). In accord, the boosted AMPA and NMDA EPSCs and the behavioral hyperactivity were also reversible at 48 hrs (Figure S6B-F). Furthermore, this increase in dendritic spines in the hM4Di + CNO group was abolished by pretreatment with GBP (100 mg/kg) for 1 hr before the administration of CNO (Figure 6A). The increased numbers of dendritic spines were associated with vGlut1 positive presynaptic puncta, indicative of increased corticostriatal synapse formation (Figure S7A,B). Consistent with this, we recorded significantly increased frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in the hM4Di + CNO group, and this was rescued by GBP pretreatment (Figure 6B, n = 1518 MSNs, n = 5 – 6 mice).

Figure 6: Gabapentin (GBP) rescued astrocyte Gi pathway-induced morphological, electrophysiological, and behavioral phenotypes.

(A) Increase in spine density and spine head size of MSNs in hM4Di + CNO mice compared to AAV + CNO mice, which was rescued by GBP i.p. administration (n = 4 mice per group).

(B-C) Increased mEPSC frequency and evoked EPSC amplitude in hM4Di + CNO mice was rescued by GBP i.p. administration (n = 15-18 MSNs from 5-6 mice per group for B and 12-19 MSNs from 4 mice per group for C).

(D) CNO i.p. administration did not change MSN firing rate after in vivo administration of GBP (n = 7 mice for AAV + GBP, n = 5 mice for hM4Di + GBP).

(E-G) Increased ambulation in an open field (E), blunted responses to bright light stimuli (F) and novel objects (G) observed in hM4Di + CNO mice relative to controls were rescued by GBP i.p. administration (n = 14-16 mice per group for E, 12-13 mice per group for F and 7-8 mice per group for G). Scale bars, 20 μm in the left image and 2 μm in the right image (A). Full details of n numbers, precise P values and statistical tests are reported in Supplementary Table 1. * indicates P <0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, **** indicates P <0.0001, NS indicates not significantly different. See also Fig S6-7.

We next explored if the synaptic, circuit and behavioral phenotypes reported in Figures 3–4 were downstream of TSP1 given that its expression was elevated and resulted in increased excitatory synapses assessed with neuroanatomical or physiological measurements (Figure 6C-G). First, the larger AMPA and NMDA receptor mediated evoked EPSCs observed in the hM4Di + CNO group were rescued by GBP (Figure 6C; n = 12 – 19 MSNs, 4 mice). Second, following treatment with GBP, CNO failed to evoke increased MSN firing in vivo in hMD4i mice (Figure 6D; 7 & 5 mice, P > 0.05). Third, the increase in open-field activity (i.e. hyperlocomotion) caused by CNO in hM4Di mice was rescued by GBP (Figure 6E; 14 – 16 mice). Fourth, the diminished responses to bright light stimulation in the open-field for hM4Di + CNO mice (i.e. disturbed attention) were rescued by GBP (Figure 6F; 12 – 13 mice). Fifth, the diminished exploration of a novel object observed in the hM4Di + CNO group was rescued by GBP (Figure 6G; 7–8 mice). Moreover, although GBP reversed the synaptic, circuit and behavioral responses triggered by CNO in hM4Di mice, it did not affect any of these parameters in control mice (Figure 6), indicating the selectivity of TSP1 inhibition in mediating the observed phenotypes. We performed a set of experiments to determine if GBP affected CNO responses either when GBP was acutely applied to brain slices before and during CNO (Figure S7C), or following in vivo administration (Figure S7D). We detected no significant effect of GBP on CNO-evoked responses in either condition (Figure S7C,D; n = 22–36 cells from 4 mice in each condition). Taken together, our data provide strong molecular evidence for the activation of an astrocyte latent synaptogenic cue (TSP1) in adult mice following Gi-pathway activation with clear hyperactivity and disrupted attention related phenotypic readouts at cellular, circuit and in vivo levels.

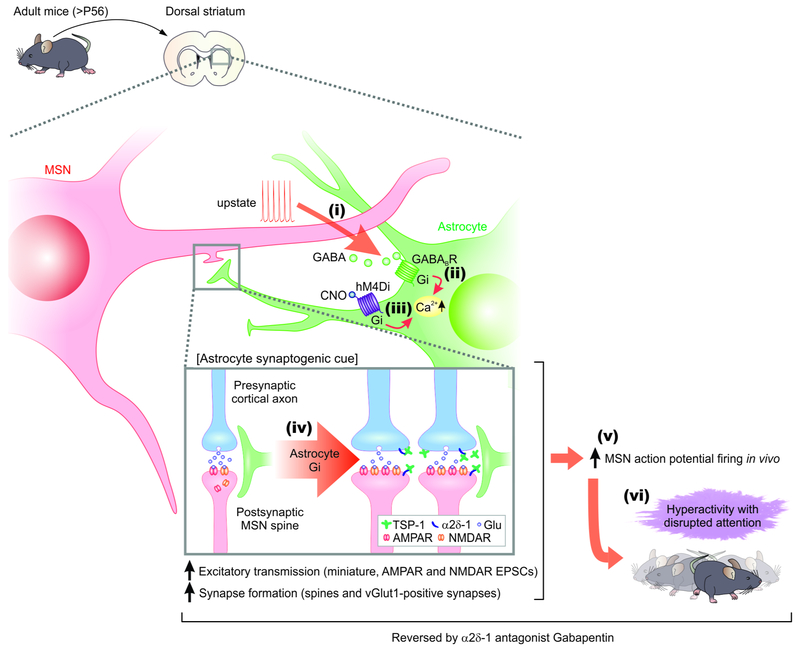

Discussion

We report a bidirectional astrocyte-neuron signaling mechanism that boosts fast excitatory synaptic transmission with clear neural circuit and behavioural effects in fully developed mice. As far as we know, this is the first example that an acute, selective and physiologically relevant manipulation of astrocytes can lead to psychiatric phenotypes of hyperactivity with disturbed attention in adult mice. The key findings are summarized in Figure 7. These data advance the concept that reactivation of latent astrocyte synaptogenic cues can reversibly drive psychiatric phenotypes in adults, portending the exploitation of such mechanisms for therapeutics.

Figure 7: Summary and model for Gi GPCR-mediated MSN-astrocyte bidirectional interactions.

When MSNs were depolarized to levels associated with upstates, they released GABA (step i) which activated Gi-protein coupled GABAB GPCRs on striatal astrocytes, leading to increase in intracellular Ca2+ signals (step ii). Selectively stimulating the Gi-pathway with DREADDS and CNO evoked Ca2+ signals in striatal astrocytes (step iii), upregulated the astrocyte synaptogenic molecule TSP-1, boosted excitatory synapse formation, boosted fast excitatory synaptic transmission (step iv) and increased firing of MSNs (step v), which together resulted in hyperactivity with disrupted attention phenotypes in mice (step vi). The synaptic, circuit and behavioral effects resulting from Gi-pathway activation in vivo (steps iv-vi) were all reversed by blocking TSP-1 actions on neuronal α2δ–1 receptors with gabapentin.

We propose a model in which MSNs communicate with astrocytes via the release of GABA during heightened activity such as upstate transitions. Such functional interactions are supported by the proximity of ~12 MSNs and ~51,000 excitatory synapses within the territory of single striatal astrocytes (Chai et al., 2017). Furthermore, astrocyte processes make extensive contacts with excitatory synapses onto MSNs, with 82% of such synapses being located within 100 nm of an astrocyte process (Octeau et al., 2018). Our data are most consistent with the hypothesis that GABA is released from MSN dendrites (Waters et al., 2005), which has been suggested for other neuroactive substances (Bernardinelli et al., 2011; Navarrete and Araque, 2008). Once released from MSNs, GABA activates Gi-coupled GABAB GPCRs, which are highly expressed in rodent and human astrocytes (Chai et al., 2017; Srinivasan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). GABAB receptor activation in turn results in the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels via release from stores (Jiang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018). In these regards, intracellular Ca2+ imaging represents a precise, quantifiable readout of GABAB receptor activation in living tissue, because multiple astrocyte GPCRs, including Gi-coupled GPCRs, result in Ca2+ elevations (Chai et al., 2017; Kang et al., 1998; Porter and McCarthy, 1997; Shigetomi et al., 2016). Selective activation of the Gi-pathway in astrocytes resulted in elevated Thbs1 gene expression, and the resultant TSP-1 actions increased excitatory synapse formation, synaptic function, increased MSN firing in vivo and for the behavioural hyperactivity and disturbed attention phenotypes triggered by the striatal astrocyte Gi-pathway. The effects on Thbs1 were selective in relation to a variety of other molecules implicated in synapse formation and removal (Allen and Lyons, 2018).

Advances with in vivo imaging and with mouse models of disease have fueled new hypotheses and have necessitated the need to understand how astrocytes regulate neural circuits and behavior (Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Nimmerjahn and Bergles, 2015). Indeed, it has long been suggested that astrocytes and neurons may functionally interact to regulate circuits (Barres, 2008; Kuffler, 1967; Smith, 1994) and ultimately behavior, but the mechanisms and consequences have been difficult to identify and study (Halassa and Haydon, 2010). In one proposed mechanism, astrocytes regulate neurons via GPCR mediated signaling that has been documented in vitro and in vivo in multiple species, including in human astrocytes (Shigetomi et al., 2016). There has been important progress in exploring hippocampal astrocytes and the release of d-serine gliotransmitter (Adamsky et al., 2018; Henneberger et al., 2010), but the biology of the Gi pathway that is preferentially enriched within striatal astrocytes relative to hippocampal astrocytes has been unknown (Chai et al., 2017). We found that this pathway is physiologically engaged in striatal astrocytes and we made the discovery that its activation regulates behavior associated with hyperactivity and disturbed attention phenotypes in mice. Our findings show that activation of a single astrocyte-derived synaptogenic cue (TSP1) in adult mice via Gi-pathway signaling causes acute behavioral hyperactivity with disrupted attention via a synaptic mechanism. The consequences of Gi-pathway activation in vivo were reversible. The finding that astrocyte signaling can reactivate latent synaptogenic cues provides an unappreciated mechanism by which astrocytes regulate synapses and circuits. This mechanism may operate in parallel with or separately from gliotransmission (Araque et al., 2014), but is the underlying cause of the responses reported herein.

We speculate on additional settings under which astrocyte Gi-pathway activation mediated by MSN GABA would occur. Our data suggest that astrocyte Ca2+ signaling would accompany heightened activity of MSNs such as during upstates. Upstates occur during convergent glutamatergic excitation from multiple synaptic inputs into the striatum, which overrides the influence of MSN inward rectifier K+ channels resulting in depolarized membrane voltages from which APs emerge (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). In addition, heightened MSN activity occurs during dopamine release from the nigro-striatal pathway: the consensus is that such modulation increases D1 MSN excitability (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). Dopamine plays known roles in the control of motor skills, higher cognitive functions and the appetitive and consummatory aspects of reward (Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012). Elevated and altered MSN activity is also observed in a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions such as Huntington’s disease (HD), Parkinson’s disease, OCD and addiction (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011; Kreitzer and Malenka, 2008), although the nature and magnitude of the change almost certainly varies with disease progression in some or all of these cases. With the exception of HD (Khakh et al., 2017), the contributions of astrocytes to these conditions are essentially unexplored. Our data raise the possibility that the TSP1-dependent bidirectional astrocyte-neuron signaling mechanism might contribute to the phenotypes associated with the aforementioned physiologies and pathologies, either causally and/or correlatively.

Overall, our findings show not only that physiological activity of neurons triggers astrocyte signaling, but that signaling from astrocytes to neurons is also sufficient per se to alter synapses, circuits and behavior in adults, which has broad relevance to brain plasticity and neural network dynamics on time scales beyond fast neuronal activity alone (Cui et al., 2018). More conceptually, therefore, the findings suggest that behavioral phenotypes accompanying diverse brain disorders that currently lack mechanistic understanding in adults may have an astrocytic component and that identifying and exploiting astrocyte based neuromodulation affords new therapeutic opportunities for ADHD-like and possibly other psychiatric diseases.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Baljit S. Khakh (bkhakh@mednet.ucla.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at the University of California, Los Angeles. All mice were housed with food and water available ad libitum in a 12 hr light/dark environment. All animals were healthy with no obvious behavioral phenotype, were not involved in previous studies, and were sacrificed during the light cycle. Data for experiments were collected from adult mice (8–14 weeks old). For behavior tests and in vivo electrophysiology, only male wild-type C57BL/6NJ mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories were used. For other experiments, both male and female C57BL/6NTac mice were used. Mice were generated from in house breeding colonies or purchased from Taconic Biosciences.

Mouse models

Dldla-tdTomato transgenic mice were kindly provided from Michael Levine’s laboratory at UCLA. To selectively express GCaMP6f in astrocytes, Ai95 mice were crossed with Aldh1l1-CreERT2 BAC mice (B6N.FVB-Tg(Aldh1l1-cre/ERT2)1Khakh/J, JAX Stock # 029655) and injected with 75 mg/kg tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil for 5 days at 6 weeks of age. Floxed Gabbr1 mice were kindly provided by Dr. Henriette van Praag at the NIH and maintained in the Balb/c genetic background at UCLA.

METHODS DETAILS

Stereotaxic microinjections of adeno-associated viruses (AAV)

All surgical procedures were conducted under general anesthesia using continuous isoflurane (induction at 5%, maintenance at 1–2.5% vol/vol). Depth of anesthesia was monitored continuously and adjusted when necessary. Following induction of anesthesia, the mice were fitted into a stereotaxic frame with their heads secured by blunt ear bars and their noses placed into a veterinary grade anesthesia and ventilation system (David Kopf Instruments). Mice were administered 0.1 mg/kg of buprenorphine (Buprenex, 0.1 mg/ml) subcutaneously before surgery. The surgical incision site was then cleaned three times with 10% povidone iodine and 70% ethanol (vol/vol). Skin incisions were made, followed by craniotomies of 2–3 mm in diameter above the left frontal or parietal cortex using a small steel burr (Fine Science Tools) powered by a high-speed drill (K.1070, Foredom). Saline (0.9%) was applied onto the skull to reduce heating caused by drilling. Unilateral viral injections were carried out by using a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments) to guide the placement of beveled glass pipettes (1B100–4, World Precision Instruments). For the left striatum: the coordinates were 0.8 mm anterior to bregma, 2 mm lateral to midline, and 2.4 mm from the pial surface. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) was injected by using a syringe pump (Pump11 PicoPlus Elite, Harvard Apparatus). Following AAV microinjections, glass pipettes were left in place for at least 10 min prior to slow withdrawal. Surgical wounds were closed with external 5–0 nylon sutures. Following surgery, animals were allowed to recover overnight in cages placed partially on a low-voltage heating pad. Buprenorphine was administered two times per day for up to 2 days after surgery. In addition, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole was provided in food to the mice for 1 week. Virus injected mice were used for experiments at least two weeks post surgery. Viruses used were: 0.5 μl of AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-cyto-GCaMP6f virus (2.3 × 1013 genome copies); 0.8 μl of AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-hM4Di-mCherry virus (1.1 × 1013 genome copies/ml); 0.4 μl of AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-tdTomato virus (1.0 × 1014 genome copies/ml); 0.7 μl of AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-PI-CRE virus (1.3 × 1013 genome copies/ml); 0.8 μl of AAV1 hSyn-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP virus (2.9 × 1013 genome copies); 0.7 μl of AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-Rpl22-HA virus (2.1 × 1013 genome copies/ml).

In vivo activation of hM4Di

Two to three weeks after appropriate microinjection of AAV2/5 hM4Di-mCherry into the striatum, CNO was administered to animals by intraperitoneal injection (1 mg/kg; dissolved in saline). Two hours after CNO administration, animals were used for behavior tests, or sacrificed for brain slice experiments or immunohistochemistry. For in vivo electrophysiology, CNO was intraperitoneally injected 30 min after baseline recording (please see In vivo electrophysiology section for details).

Optical stimulation of neurons in vivo

Construction of the fiber optic cannula:

we constructed a fiber optic cannula from the DIY-cannula kit (Prizmatix). Briefly, the fiber optic was cleaved into the desired length using a metal scribe. A small droplet of epoxy resin was applied on the flat opening of the cannula. The cleaved fiber optic was inserted through the epoxy into the cannula until it protruded approximately 1 mm from the opposite end of the cannula. Epoxy was then cured using a heat gun to secure the cannula in place. The fiber optic cannula was allowed to cool down for 2 hours and then made transparent using polishing paper of increasing grits (from 4500–60000 grits) on the convex end of cannula. The cannulated fibers were connected to the external LED source (Prizmatix) using a patch cord and tested for their integrity and maximum light output.

Fiber optic implantation surgery:

we implanted the cannula into the brain of anesthetized mice just after AAV microinjections. After the microinjection needle was removed, the cannula was slowly lowered into the striatum and secured in place using vetbondTM and a thin layer of dental cement. Thin and uniform layers of dental cement were applied around the cannula. The mouse was allowed to recover from the surgery for 3 weeks. Once the mouse had recovered and the virus had expressed, the mouse was connected to the optical stimulation system. The optical cannula was connected to the patch cord through the mating sleeve. An optical stimulation (3–4 mW) paradigm consisting of 2.5 s light-on and 27.5 s light-off (mimicking MSN up-state like excitability) for a period of 60 min was administered to each mouse. The mice were perfused at 8 hr post stimulation for IHC.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Frozen sections:

For transcardial perfusion, mice were euthanized with pentobarbitol (i.p.) and perfused with 10% buffered formalin (Fisher #SF100-20). Once all reflexes subsided, the abdominal cavity was opened and heparin (50 units) was injected into the heart to prevent blood clotting. The animal was perfused with 20 ml ice cold 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 60 ml 10% buffered formalin. After gentle removal from the skull, the brain was postfixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C. The tissue was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose PBS solution the following day for at least 48 hours at 4°C until use. 40 μm coronal sections were prepared using a cryostat microtome (Leica) at −20°C and processed for immunohistochemistry. Sections were washed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min each, and then incubated in a blocking solution containing 10% NGS in 0.1 M PBS with 0.5% Triton-X 100 for 1 hr at room temperature with agitation. Sections were then incubated with agitation in primary antibodies diluted in 0.1 M PBS with 0.5% Triton-X 100 overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-GFP (1:1000; Abcam ab13970), mouse anti-NeuN (1:500; Millipore MAB377), rabbit anti-S100b (1:1000; Abcam ab41548), rabbit anti-c-Fos (1:1000; Millipore ABE457), rabbit anti-RFP (1:1,000; Rockland 600–401-379). The next day the sections were washed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min each before incubation at room temperature for 2 hr with secondary antibodies diluted in 0.1 M PBS. Alexa conjugated (Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution except streptavidin conjugated Alexa 647 at 1:250 dilution. The sections were rinsed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min each before being mounted on microscope slides in fluoromount-G. Fluorescent images were taken using UplanSApo 20X 0.85 NA, UplanFL 40X 1.30 NA oil immersion or PlanApo N 60X 1.45 NA oil immersion objective lens on a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV10-ASW; Olympus). Laser settings were kept the same within each experiment. Images represent maximum intensity projections of optical sections with a step size of 1.0 μm. Images were processed with ImageJ. Cell counting was done on maximum intensity projections using the Cell Counter plugin; only cells with soma completely within the region of interest (ROI) were counted. For astrocyte-dendrite proximity analysis (Figure S2E,F), image was taken with a step size of 0.33 μm and maximum intensity projections of 3 slices (1 μm stack) was obtained. A line ROI was made across the dendrite that is apposed to astrocyte processes. The peak of obtained from each profile was defined as the center of dendrite or astrocyte process and the distance between them was measured. For Figure 1I, c-Fos expression in astrocytes were analyzed within 800 μm from the end of fiber optics.

Acute sections:

300 μm fresh brain slices were placed into 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C and processed as follows for IHC. Sections were washed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS with 2% Triton-X 100 for 5 min each, and then incubated in a blocking solution containing 10% NGS in 0.1 M PBS with 1% Triton-X 100 for 1 hr at room temperature with agitation. Sections were then incubated with agitation in primary antibodies diluted in 0.1 M PBS with 0.4% Triton-X 100 for 3 days at 4°C. The primary antibody was guinea pig anti-vGlut1 (1:2000; Synaptic Systems 135302). Sections were washed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS with 0.4% Triton-X 100 for 10 min each before incubation 3 days at 4°C with streptavidin conjugated Alexa 647 (1:250) diluted in 0.1 M PBS with 0.4% Triton-X 100. The sections were rinsed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min each before being mounted on microscope slides in fluoromount-G. Images were obtained in the same way as IHC for frozen sections except a step size of 0.33 μm. For quantification of spine density, we only analyzed spines on dendritic shafts that are parallel to the imaging plane to minimize the possibility of rotational artifacts. Spine density was calculated by dividing the number of spines by the length of the dendritic segment. For quantification of spine head size, a line ROI across the maximum diameter of the spine was made and a profile that has a single peak and is closer to a Gaussian curve was obtained. Full-Width Half-Maximum of that was defined as a spine head size to avoid the point spread function. For counting the number of vGlut1-positive synapse, only spines that are off from optical plane were analyzed. As shown in Figure S7A, a line ROI was made over MSN spine and vGlut-1 puncta that is closest to the spine. FWHM of each profile was measured. A MSN spine was recognized as forming vGlut-1-positive synapse when each FWHM is overlapped (see Figure S7A), while recognized as not forming vGlut-1-positive synapse when there is a gap between each FWHM (see Figure S7A). As a result, the ratio of vGlut-1-positive synapse number to total number of MSN spines was 47 ± 6%, which is reasonably matched with previous synapses analysis of MSN using EM (Doig et al., 2010).

Dual in situ hybridization (ISH) with RNAscope and IHC

Cryosections were prepared as described above and stored at −80°C. ISH was performed using Multiplex RNAscope (ACDBio 320851). Sections were washed at least for 15 min with 0.1 M PBS, and then incubated in 1X Target Retrieval Reagents (ACDBio 322000) for 5 min at 99–100°C. After washing with ddH2O twice for 1 min each, they were dehydrated with 100% ethanol for 2 min and dried at RT. Then, the sections were incubated with Protease Pretreat-4 solution (ACDBio 322340) for 30 min at 40°C. The slides were washed with ddH2O twice for 1 min each and then incubated with probe(s) for 2 hours at 40°C. The following probes were used: Mm-Gabbr1-C2 (ACDBio 425181-C2), Mm-Aldh1l1-C3 (ACDBio 405891-C3) and Mm-Thbs1-C3 (ACDBio 457891-C3). The sections were incubated in AMP 1-FL for 30 min, AMP2-FL for 15 min, AMP3-FL for 30 min and AMP4-FL for 15 min at 40°C with washing in 1X Wash Buffer (ACDBio 310091) twice for 2 min each prior to the first incubation and in between incubations. All the incubations at 40°C were performed in the HybEZ™ Hybridization System (ACDBio 310010). Slices were washed in 0.1 M PBS three times for 10 min each, followed by IHC that was performed as described above except with antibody dilutions. Following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-GFP (1:250; Abcam ab13970) to stain GCaMP and rabbit anti-RFP (1:250; Rockland 600–401-379) to stain tdTomato or mCherry. Images were obtained in the same way as IHC described above except a step size of 0.8 μm. Images were processed with ImageJ (NIH). Astrocyte somata were demarcated based on GFP or RFP signal, and number of puncta and intensity of probe signals within somata were measured.

Acute brain slice preparation for imaging and electrophysiology

Sagittal striatal slices were prepared from 8–11 week old C57 WT mice, or C57 WT mice with AAV injection plus CNO or vehicle I.P. injection for EPSCs recording. For other experiments, coronal striatal slices were prepared from 8–11 week old C57 WT mice with AAV injection or Aldh1l1-cre/ERT2 × Ai95 mice. Briefly, animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated with sharp shears. The brains were placed and sliced in ice-cold modified artificial CSF (aCSF) containing the following (in mM): 194 sucrose, 30 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 10 D-glucose, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. A vibratome (DSK-Zero1) was used to cut 300 μm brain sections. The slices were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min at 32–34°C in normal aCSF containing (in mM); 124 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 10 D-glucose continuously bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Slices were then stored at 21–23°C in the same buffer until use. All slices were used within 4–6 hours of slicing.

Electrophysiological recordings in the striatal slices

Electrophysiological recordings were performed using standard methods as described belows. Slices were placed in the recording chamber and continuously perfused with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 bubbled normal aCSF. pCLAMP10.4 software and a Multi-Clamp 700B amplifier was used for electrophysiology (Molecular Devices). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in the dorsolateral striatum using patch pipettes with a typical resistance of 56 MΩ. MSNs were morphologically and electrophysiologically identified. In some experiments, D1- and D2-MSNs were selected based on tdTomato fluorescence. The intracellular solution for MSN EPSCs recordings comprised the following (in mM) : 120 CsMeSO3, 15 CsCl, 8 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, 0.3 Na-GTP, 2 Mg-ATP, 10 TEA-Cl, with pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. The intracellular solution for other experiments comprised the following (in mM): 135 potassium gluconate, 5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP and 0.3 Na-GTP, pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH. To assess evoked EPSCs, electrical field stimulation (EFS) was achieved using a bipolar matrix electrode (FHC) that was placed on the dorsolateral corpus callosum to evoke glutamate release from the cortico-striatal pathway. The MSNs to be assessed were typically located ~300-400 μm away from the stimulation site to avoid the EFS-evoked astrocyte calcium increase that occurs nearby the stimulating electrode. In order to construct stimulus-response curves for each striatal slice, electrical stimulation current intensity was varied from 0 to 800 μA in 50 μA steps for each cell. We determined full stimulation-response curves for the AMPA EPSCs at −70 mV: cells in which the stimulation evoked antidromic spiking at current levels below 800 μA were recorded only over the current range that evoked EPSCs, i.e. none of the recordings shown in the study were contaminated with antidromic spiking. We could not determine full stimulation-response curves for NMDA EPSCs, because clamping the cells at +40 mV for the prolonged periods needed for such assessments decreased the quality of whole-cell recording. However, we evaluated AMPA and NMDA EPSCs equivalently when stimulation intensities were set to 250 μA that approximately evoke responses at 50% maximal amplitude of the AMPA EPSCs. To isolate the AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated evoked EPSCs, MSNs were voltage-clamped at −70 mV or +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM bicuculline. Paired pulses were delivered at 50 ms inter-pulse intervals. The AMPAR-mediated EPSC was measured at the peak amplitude of the EPSC at −70 mV, while the amplitude of the EPSC 50 ms after stimulation at +40 mV was used to estimate the NMDAR-mediated component. To isolate mEPSCs, MSNs were voltage-clamped at −70 mV and pre-incubated with 10 μM bicuculline and 300 nM TTX for 5 min before recording. In some cases, 1 mg/ml biocytin (Tocris, 3349) was added to the intracellular solution to subsequently visualize patched neuron. All recordings were performed at room temperature, using pCLAMP10 (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices) and a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices). Cells with Ra that exceeded 20 MΩ were excluded from analysis. Analysis was performed using ClampFit 10.4 software.

Astrocyte intracellular Ca2+ imaging

Imaging:

Slice preparation was performed as described above. Cells for all the experiments were imaged using a confocal microscope (Fluoview 1200; Olympus) with a 40X water-immersion objective lens with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.8 and at a digital zoom of two to three. We used the 488 nm line of an Argon laser, with the intensity adjusted to 9% of the maximum output of 10 mW. Astrocytes were typically ~20 to ~30 μm below the slice surface and scanned at 1 frame per second for imaging sessions. When imaging was performed along with MSN depolarization, astrocytes were located nearby (< 50 μm) from MSN somata or dendrites that were visualized by MSN dialysis with Alexa Fluor 568 hydrazide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A10441).

Drug applications:

the following agonists were applied in the bath: Phenylephrine (Tocris Bioscience 2838), γ-Aminobutyric acid (Sigma Aldrich A2129), R-Baclofen (Tocris Bioscience 0796), Clozapine N-oxide (CNO, Tocris Bioscience 4936). Inhibitors and antagonists were applied in the bath at least 5 min prior to recording to allow adequate equilibration. The following inhibitors and antagonists were used: Tetrodotoxin (Cayman Chemical 14964), CdCl2 (Sigma Aldrich 439800), Nimodipine (Tocris Bioscience CAS 0600), CGP55845 (Tocris Bioscience 1248), Bicuculline (Abcam ab120110 or Tocris Bioscience 0131) and NNC711 (Tocris Bioscience 1779). PLC inhibitor U73122 (Tocris Bioscience 1268) or its control analog U73433 (Tocris Bioscience 4133) was applied in bath for 40 min prior to recording. 1,2-Bis(2-Aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA from Sigma Aldrich A4926) or Recombinant Light Chain from Tetanus Toxin (List Biological Laboratories 650A) was dialyzed in MSN through patch pipette prior to MSN depolarization at least for 20 min or 10 min, respectively. A constant flow of fresh buffer perfused the imaging chamber at all times.

Neuron intracellular Ca2+ imaging

Slice preparation was performed as described above. MSNs were dialyzed via the whole-cell patch pipette with 100 μM Fluo-4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific F14200) at least 5 min before imaging. A line ROI was made on MSN somata and line scan imaging was performed at 500 Hz with a 40X water-immersion objective lens. Imaging and analyses were conducted using FV10-ASW from Olympus.

qPCR experiments

Amplified cDNA from RNA samples (RiboTag IP and FACS) was generated using Ovation PicoSL WTA System V2 (Nugen). The cDNA was then purified with a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and quantified with a Nanodrop 2000. qPCR was performed in a LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche). Amplified cDNA from eGFP-positive cell populations from three separate sorts was used. Ten nanograms of cDNA were loaded per well and the expression of Gabbr1, Gabbr2, and Arbp was analyzed using the primers shown below:

| Gene | Sequence | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Gabbr1 | Forward 5’ ACAGACCAAATCTACCGGGC 3’ Reverse 5’ GTGCTGTCGTAGTAGCCGAT 3’ |

152 |

| Gabbr2 | Forward 5’ AAGCTCAAGGGGAACGACG 3’ Reverse 5’ ACTTGCTGCCAAACATGCTC 3’ |

115 |

| Arbp | Forward 5’ TCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCA 3’ Reverse 5’ AGTCTTTATCAGCTGCACATCAC 3’ |

76 |

Arbp was used as an internal control to normalize RNA content. To calculate the expression of gene of interest, the following formula was used: 2-ΔCt (Gene of interest-Arbp).

Western blot analyses

Standard SDS-PAGE was performed. Each lane contained protein extracted from one fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) experiment. Aldh1l1-eGFP mice were used to purify astrocytes by FACS. Whole striata from heterozygous P30 mice were dissociated. Briefly, the striata from four mice (two male and two females) were dissected and digested together for 45 min at 36°C in a 35 mm Petri dish with 2.5 ml of papain solution (1x EBSS, 0.46% D-glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 50 mM EDTA, 75 U/ml DNase1, 200 units of papain for hippocampal and 300 units of papain for striatal tissue, and 2 mM L-cysteine) while bubbling with 5% CO2 and 95% O2. After digestion, the tissue was washed four times with ovomucoid solution (1x EBSS, 0.46% D-glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1 mg/ml ovomucoid, 1 mg/ml BSA, and 60 U/ml DNase1) and mechanically dissociated with two fire-polished borosilicate glass pipettes with different bore sizes. A bottom layer of concentrated ovomucoid solution (1× EBSS, 0.46% D-glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 5. mg/ml ovomucoid, 5.5 mg/ml BSA, and 25 U/ml DNase1) was added to the cell suspension. The tubes were centrifuged at room temperature at 300 g for 10 min and the resultant pellet was re-suspended in D-PBS with 0.02% BSA and 13 U/ml of DNase1, and filtered with a 20 μm mesh. FACS was performed in a FACSAria II (BD Bioscience) with a 70 μm nozzle using standard methods at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Cell Sorting Core. For protein extraction, cells were collected in D-PBS and, right after FACS, cells were incubated with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 12 mM Na+-Deoxycholate, 3.5 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris pH8, 1:100 Halt Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific)) at 4°C for 40 mins. The extracted protein was subsequently precipitated with trifluoroacetic acid and acetone. Protein pellet was dried and resuspended in a proteomics compatible buffer (0.5% Na-Deoxycholate, 12 mM N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt, 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate), boiled at 95 °C for 10 min and stored at −80°C. A total of six separate cell sorts from 26 mice were included in the analysis. We probed for GABAB1R and β-actin using guinea pig anti-GABAB1R (Millipore AB2256) and rabbit antî-actin (Abcam ab8227) primary antibodies at 1:1000 dilution. The secondary antibodies IRDye 680RD anti-guinea pig (Li-Cor 925–68077) and IRDye 800CW anti-rabbit (Li-Cor 827–08365) were added to visualize the proteins using a Li-Cor Odyssey imager. Signal intensities were quantified with Image J (NIH) and normalized to β-actin.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle. Only male mice were used in behavioral tests because of gender-dependent differences known for striatal physiology. All the experimental mice were transferred to the behavior testing room at least 30 min before the tests to acclimatize to the environment and to reduce stress. Temperature and humidity of the experimental rooms were kept at 23 ± 2°C and 55 ± 5%, respectively. The brightness of the experimental room was kept < 15 fc unless otherwise stated. Background noise (60–65 dB) was generated by Air Purifier 50150-N from Honeywell Enviracaire. 1 mg/kg CNO or vehicle (0.86% DMSO) was intraperitoneally injected to mice 2 hours before the initiation of test. 100 mg/kg Gabapentin (Tocris Bioscience 0806) or saline was intraperitoneally injected to mice 3 hours before the initiation of test.

Open field test:

For Figure 3, the open field chamber consisted of a square arena (28 × 28 cm) enclosed by walls made of Plexiglass (19 cm tall). Locomotor activity was then recorded for 20 min using an infrared camera located underneath the open field chamber. Recording camera was connected to a computer operating an automated video tracking software Noldus Ethovision. Parameters analyzed included distance traveled with 5 min and 20 min time bins. For Figure 6, the open field chamber consisted of a square arena (26.7 × 26.7 cm) enclosed by walls made of translucent polyethylene (20 cm tall). Locomotor activity was then recorded for 30min using an infrared camera located above the open field chamber. Recording camera was connected to a computer operating an automated video tracking software Topscan from CleverSys. Parameters analyzed included distance traveled with 5 and 30 min time bins.

Open field test with bright light stimulus:

As previously described (Godsil and Fanselow, 2004), the modified open-field arena was a white, translucent polyethylene box (Model CB-80, Iris USA, Pleasant Prairie, WI) with internal dimensions of 69 cm long × 34 cm wide × 30 cm high (Godsil et al., 2005a; Godsil and Fanselow, 2004; Godsil et al., 2005b). Three lamps containing single 100 W white light bulbs were positioned at one end of the table (see Figure 3D). One lamp was positioned 14 cm from the center of a short wall of the rectangular arena; one lamp flanked each long side of the arena, 14 cm from the long walls and 15 cm from the original short wall. All three lamps were situated 18 cm above the base of the arena. The test is divided into three phases. Illumination levels were measured with a light meter (Model 403125, Extech Instruments, Waltham, MA). Cameras suspended from the ceiling or floor monitored and captured activity of animals. Locomotive activity was measured using the software Topscan from CleverSys. Parameters analyzed included distance traveled with 1 min and 4 min time bins. Phase 1 minutes 1-4 is the dark phase where the lights are turned off (< 0.5 fc). Phase 2 is the light phase minutes 5-8 where the lights will be turned on and create an illumination gradient across the arena (~100 fc at one end of the open field with light). Phase 3 minutes 9-12 the lights will be turned off (< 0.5 fc). The change in locomotion was calculated as follows: distance travelled in Phase 1 divided by the distance travelled in Phase 2.

Rearing behavior:

Mice were placed individually into plastic cylinders (15 cm in diameter and 35 cm tall) and allowed to habituate for 20 min. Rearing behavior was recorded for 10 min. A timer was used to assess the cumulative time spent in rearing behavior, in which mice support their weight freely on its hind legs without using its tail or forepaws.

Rotarod test:

Mice were held by the tails and placed on a single lane rotarod apparatus (ENV-577M, Med Associates Inc.), facing away from the direction of rotation. Mice were habituated on the rod for 1 min just before the trial. The rotarod was set with a start speed of 4 rpm. Acceleration started 10 seconds later and was set to 20 rpm per minute with a maximum speed 40 rpm. Each mouse received 5 trials at least 5 min apart per day for two consecutive days and the latency to fall was recorded for each trial.

Footprint test:

A one-meter long runway (8 cm wide) was lined with paper. Each mouse with hind paws painted with non-toxic ink was placed at an open end of the runway and allowed to walk to the other end with a darkened box. For the gait analysis, stride length and width were measured and averaged for both left and right hindlimbs over 5 steps.

Marble burying test:

a fresh, unscented soft wood chip bedding was added to polycarbonate cages (21 cm × 43 cm × 20.5 cm) to a depth of 5 cm. Sanitized 15 glass marbles were gently placed on the surface of the bedding in 5 rows of 3 marbles. Mice were allowed to remain in the cage undisturbed for 30 min. A marble was scored as buried if two-thirds of its surface area was covered by bedding.

Novel Object Recognition test:

At day 1 and day 2, mice were placed in an empty open chamber (26.7 × 26.7 cm) for 10 minutes for habituation. At day 3 (training day), mice were placed in the same open chamber containing two identical objects evenly spaced apart; trial was video recorded for 10 minutes. At day 4 (testing day), 24 hours after training, mice were placed in the same open chamber, but one of the two objects has been replaced with a novel object; trial is video recorded for 10 minutes. Time exploring around the objects was measured. Recognition index was calculated as follows: (time exploring the novel object – time exploring the familiar object) / (time exploring both objects) – 50.

In vivo electrophysiology

Surgeries and habituation:

All animals underwent surgical procedures under aseptic conditions and isoflurane anesthesia on a stereotaxic apparatus. We attached rectangular head fixation bars on each side of the skull (9 × 7 × 0.76 mm dimensions, 0.6 g weight, laser cut from stainless steel at Fab2Order). Animals were allowed to recover for 2 weeks before beginning habituation. Carprofen (5 mg/kg, s.c.) was administered daily for the first three days post-operatively and Analgesics (ibuprofen) and antibiotics (amoxicillin) were administered in the drinking water for the first week post-operatively. Animals were habituated to the head fixation apparatus and the circular treadmill (a freely-rotating spherical styrofoam ball) in the dark for 4 days at least for 30 min per each day. To habituate to I.P. injection, saline was administered intraperitoneally on halfway through the habituation. No stimuli were present during habituation. On the recording day, animals underwent a brief craniotomy surgery above the striatum and cerebellum under isoflurane anesthesia. The dura was removed. During a recovery period, the craniotomies were sealed with a silicone elastomer compound (Kwik-Cast, World Precision Instruments).

Recording:

Neural recordings were carried out either with a 128 or 256-electrode silicon microprobe. The 128-electrode device consisted of 4 prongs spaced by 330 μm, 32 electrodes per prong in a staggered array pattern spanning a depth of 990 μm. The 256-electrode device consisted of 4 prongs spaced by 200 μm, 64 electrodes per prong in a honeycomb array pattern spanning a depth of 1.05 mm). Prior to their first use electrodes were gold plated with constant pulses (−2.5 V relative to a Pt wire reference, 1-5 s) until their impedence reached below 0.5 MΩ to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Subsequently, awake animals were head restrained, a silver/silver-chloride electrical reference wire was placed in contact with CSF above the cerebellum, and the microprobe was inserted into the striatum under the control of a motorized micromanipulator. The target coordinates of the most lateral silicon prong were 0.8 mm anterior, 2.5 mm lateral, 4.0 mm ventral to bregma. Mineral oil was placed on the craniotomy to prevent drying. Data acquisition commenced 30 min after device insertion, using custom-built hardware at a sampling rate of 25 kHz per electrode. Treadmill velocity was sampled at a rate of 10 kHz and animal speed was calculated as the mean rotational velocity. The distance the mice traveled was calculated as the integrated area of the speed. No stimuli were present during recording. The microprobe was cleaned after each recording session in a trypsin solution and deionized water and ethanol, and reused in subsequent experiments.

RNA-Seq analysis of striatal astrocyte transcriptomes

AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-hM4Di-mCherry virus and AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-Rpl22-HA virus were microinjected into the dorsal striatum of adult (P44–45) male C57Bl/6NJ mice. 18-19 days later, RNA was collected from striata of those mice (at P63). Briefly, freshly dissected tissues were collected from four animals and individually homogenized. RNA was extracted from 10-20% of cleared lysate as input. The remaining lysate was incubated with mouse anti-HA antibody (1:250; Covance #MMS-101R) with rocking for 4 hours at 4°C followed by addition of magnetic beads (Invitrogen Dynabeads #110.04D) and overnight incubation with rocking at 4°C. The beads were washed three times in high salt solution. RNA was purified from the IP and corresponding input samples (Qiagen Rneasy Plus Micro #74034). RNA concentration and quality were assessed with nanodrop and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. RNA samples were used for the Ribo-Zero rRNA reduction prep. Sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq 4000 using paired-end 75 bp reads. Data quality check was done on Illumina SAV. Demultiplexing was performed with Illumina Bcl2fastq2 v 2.17 program. Reads (60 to 84M per sample) were aligned to the latest mouse mm10 reference genome using the STAR spliced read aligner. Between 79 and 91% of the reads mapped uniquely to the mouse genome and were used for subsequent analyses. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with genes with FPKM > 5 at least 4 samples per condition and Log2FC > 1 or < −1, using Bioconductor packages edgeR and limmaVoom with false discovery rate (FDR) threshold set at < 0.1 or 0.05 (http://www.bioconductor.org) and Htseq-count were used (Anders et al., 2015; Law et al., 2014). RNAseq data has been deposited within the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession ID # of GSE119058.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In vivo electrophysiology data analysis:

Spike sorting and all neural activity analyses were carried out with custom MATLAB scripts. Striatal units were classified as putative medium spiny neurons (MSNs), fast spiking interneurons (FSIs), or tonically active neurons (TANs), based on spike waveform peak-to-trough width, and coefficient of variation of the baseline firing rate (Bakhurin et al., 2016). FSIs were characterized by a narrow spike waveform (maximum width = 0.475 ms). MSNs and TANs both have wider waveforms (minimum width = 0.55 ms, maximum width = 1.25 ms). TANs were separated from MSNs by the regularity of their baseline firing (maximum coefficient of variation = 1.5).

Imaging data analysis:

Analyses of time-lapse image series were performed using ImageJ (NIH). XY drift was corrected using ImageJ. The data were analyzed essentially as previously reported (Chai et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016; Octeau et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2018). Time traces of fluorescence intensity were extracted from the ROIs and converted to dF/F values. For analyzing spontaneous Ca2+ signaling, regions of interest (ROIs) were defined in normal aCSF (control). Using Origin 2016 (Synaptosoft), Ca2+ events were manually marked. Event amplitudes, half width, event frequency per ROI per min, the integrated area-under-the-curve (AUC) of dF/F traces were measured. Events were identified based on amplitudes that were at least 2-fold above the baseline noise of the dF/F trace.