Abstract

Introduction

Data indicate substantial excess mortality among female neonates in South Asia compared with males. We reviewed evidence on sex and gender differences in care-seeking behaviour for neonates as a driver for this.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of literature published between January 1st, 1996 and August 31st, 2016 in Pubmed, Embase, Eldis and Imsear databases, supplemented by grey literature searches. We included observational and experimental studies, and reviews. Two research team members independently screened titles, abstracts and then full texts for inclusion, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Study quality was assessed using National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) checklists and summary judgements given using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria. Data were extracted into Microsoft Excel.

Results

Of 614 studies initially identified, 17 studies were included. Low quality evidence across several South Asian countries suggests that care-seeking rates for female neonates are lower than males, especially in households with older female children. Parents are more likely to pay more, and seek care from providers perceived as higher quality, for males than females. Evidence on drivers of these care-seeking behaviours is limited. Care-seeking rates are suboptimal, ranging from 20% to 76% across male and female neonates.

Conclusion

Higher mortality observed among female neonates in South Asia may be partly explained by differences in care-seeking behaviour, though good quality evidence on drivers for this is lacking. Further research is needed, but policy interventions to improve awareness of causes of neonatal mortality, and work with households with predominantly female children may yield population health benefits. The social, economic and cultural norms that give greater value and preference to boys over girls must also be challenged through the creation of legislation and policy that support greater gender equality, as well as context-specific strategies in partnership with local influencers to change these practices.

PROSPERO registration number

Keywords: neonatal, neonate, paediatric, mortality, morbidity, gender, equality, care-seeking, care utilisation, healthcare, South Asia, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan

Key questions.

What is already known?

Previous research has demonstrated a markedly higher neonatal mortality rate among females in comparison to males in South Asia for which various explanations have been put forward, but this is the first systematic review to collate evidence specifically on gender differentials in care-seeking behaviour in the region.

What are the new findings?

We found some evidence to suggest that care-seeking rates for female neonates are lower than males in South Asia, especially in those households with older female children, and that families are more likely both to seek and to pay for care that is perceived as high quality for male neonates.

There is limited evidence identifying which determinants of care-seeking behaviour are driving differential care-seeking and completion rates among male and female neonates, although household composition and differences in illness perception seem to be contributing factors.

What do the new findings imply?

Policy interventions in South Asia should target improvements in (1) population level awareness of determinants of neonatal mortality and illness recognition, (2) improved access to care overall, and in particular, (3) focused work with larger households with predominantly female composition and (4) address gender discrimination and inequities at a wider societal level.

Further research is also needed, particularly of a qualitative nature, to address gender perceptions and drivers of care-seeking behaviour at household level in South Asian countries.

Introduction

Low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) account for around 99% of all deaths among neonates (during the first 28 days of life).1 Although the South Asian region saw a 50% reduction in the annual number of newborns dying in the first 28 days of life between 1990 and 2015,2 the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) in the region remains one of the highest in the world.3 The region will not achieve the Sustainable Development Goal target of no more than 12 deaths per 1000 live births by 2030 without substantial improvements.

Globally, neonatal morbidity and mortality are influenced by a range of factors, including congenital risks, inadequate dietary intake, variable access to care and social and political factors including maternal education and the status of women.3 Studies across high-income, middle-income and low-income countries have found that male newborns are at approximately 20% greater risk of neonatal mortality than female newborns as a result of underlying biological disadvantages.4 Despite their biological survival advantage, however, the NMR for females in South Asia is higher than males. Work by WHO and the United Nations has highlighted South Asian countries where there is substantial female disadvantage in newborn survival.5 6

Reasons for the gender-based inversion in NMR in South Asia are poorly characterised. Excess female mortality has been attributed to a complex interplay of sex-related and gender-related factors—where gender is understood to encompass sociocultural codes of behaviour rather than overt biological differences, that place numerous negative and often fatal constraints on the health, value, and status of female children.7–9 For example, women in South Asia generally find themselves in subordinate positions to men, and are largely excluded from decision-making, have limited access to and control over resources, and are restricted in their mobility.10 11 These established gender norms have implications for how female and male children are perceived: sons are perceived to have economic, social and religious utility compared with daughters whom can be felt to be an economic liability. This is exacerbated by the dowry system practiced in many South Asian countries.12 13 While it is well documented that societal beliefs and attitudes towards appropriate gender specific roles, and the choices of individuals and households on the basis of these factors, mean that women are disadvantaged with regard to health and healthcare,14 15 little exploration of impact on female newborn survival (post birth) has taken place.

The literature on newborn survival suggests that the most likely explanations for excess female mortality centre on gender differences in child-rearing and care-seeking behaviour.16 Differences in child-rearing practices could include, for example, better nutrition for male newborns leading to lower incidence and severity of infections, and ultimately lower mortality. Evidence on care-seeking across South Asia (irrespective of gender) suggests that geographical and financial barriers to care may be significant factors driving behaviour for patients of all ages,17 18 that awareness of the importance of clinical sign and symptom recognition in neonates in particular is low, that routine care is rarely sought for them, and that where care is sought it is often delivered by unqualified providers.19 20 Gender differences in care-seeking for neonates could affect mortality through differences in rates of preventive (eg, immunisation) and curative healthcare, especially differential rates of hospitalisation for severe illnesses.

There is a well-established association between delays in seeking care, or indeed not seeking care at all, and child mortality in LMICs.21–23 Systematic review evidence on the role of care-seeking behaviours in explaining mortality rates in children under five in LMICs points to various environmental, socioeconomic and cultural factors affecting individual and family-level decision-making when a child is unwell.24 The majority of studies explore care-seeking behaviour for all neonates (or all infants or all children) and do not disaggregate their analysis of determinants according to sex.25 26 Fewer still attempt to explore if and in what ways care-seeking is gendered. Understanding how care-seeking patterns differ for male and female neonates and the reasons underlying these differences is critical in ensuring effective intervention and policy design.16

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate existing evidence on gender differences in care-seeking among neonates in South Asia. We evaluated (1) evidence on gender differentials in care-seeking behaviour and care completion for neonates in South Asia and—where such differences exist—(2) evidence on reasons for these differences. While women’s and girl’s disadvantaged position at household and societal level is a key issue with important implications for care-seeking behaviours, the way in which the problem of gender bias manifests itself was not an explicit focus for this review. The overarching aim was to identify potential areas for policy and programme intervention to address gender differences.

Methodology

The review was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Identification of studies

This was a systematic review of literature published in English between January 1st, 1996 and August 31st, 2016. We searched for peer-reviewed literature in the Pubmed, Embase and Imsear databases, augmented by searches in Eldis to identify relevant grey literature reports (see online supplementary appendix 1 for details of keyword combinations used).

bmjgh-2018-001309supp001.pdf (487.6KB, pdf)

Definitions and inclusion/exclusion criteria

We defined the neonatal period as covering the first 28 days of life. Neonatal mortality was defined as the death of a child within that period.27 The term ‘gender’ is used throughout this paper to refer to the socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for boys and girls. What gender means varies over time and across contexts. This is in contrast to ‘sex’, which refers to the chromosomal characteristics that distinguish men, women, intersex and transgender people.28

Definitions relating to recognition of illness, care-seeking and provision of care drew on those used in a systematic review addressing a similar topic but spanning all LMICs.24 Recognition of illness was defined as identification of conditions requiring care from a health provider (either qualified or unqualified). Care-seeking behaviour was defined as including any care sought for a neonate from any health provider (qualified or non-qualified) inside or outside the home. With respect to healthcare-giving, we defined qualified health providers as including all government, private and non-governmental organisation health providers. Unqualified health providers included traditional and/or spiritual healers (including but not limited to unqualified herbalists, allopaths, homeopaths and quacks).29 We used the term ‘caregiver’ to refer to individuals who sought or would have sought care for a sick neonate, in line with usage in other papers on this topic, and to reflect their role as primary caregivers in the home.24

Studies were excluded if (1) they were based outside South Asia; (2) there was no reference to gender or sex differences in morbidity/mortality; (3) there was no reference to the neonatal period; (4) they did not adopt an observational, experimental or systematic review design; or (5) they were published before January 1st, 1996. Studies were also excluded if they reported differences in male and female neonatal mortality only, but did not explore reasons for any sex or gender difference. Studies that reported differences in mortality alone were excluded on the basis that we cannot assume that care was sought prior to a newborn death.

Selection of studies

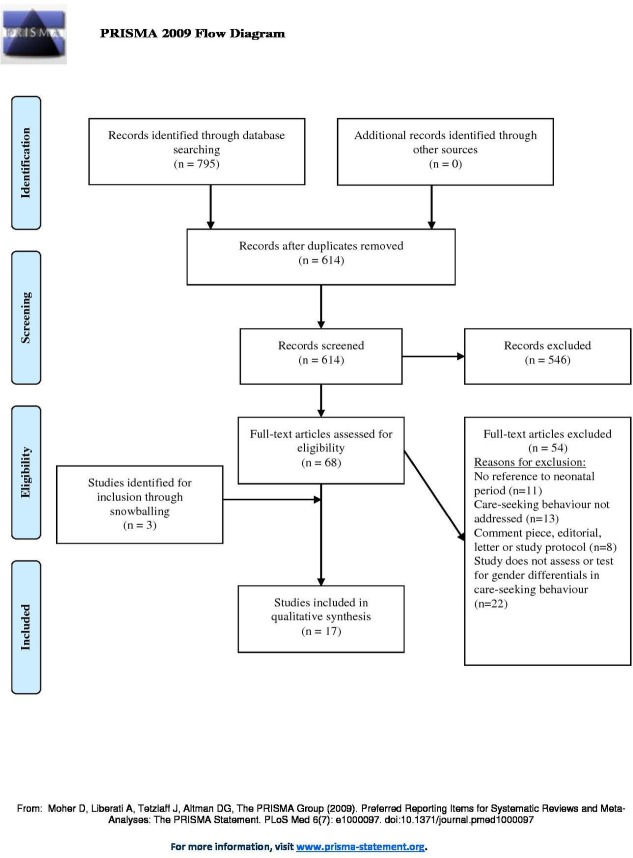

All titles returned by the searches were independently screened for inclusion or exclusion based on title and abstract by two researchers (AM and SAI), who then independently assessed full text papers. In the third stage of study selection, additional, potentially relevant studies were identified through snow-balling from reference lists of full-text articles included in the review, with inclusion based on agreement between both reviewers (AM and SAI). Level of agreement between reviewers was assessed using the Kappa statistic; instances of disagreement were resolved by consensus. Figure 1 summarises this process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the process of paper assessment in this systematic review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Assessment of study quality, data extraction and synthesis

Study quality was independently assessed by two researchers (AM and SAI). In view of the diversity of study designs included, a pragmatic approach to quality assessment was employed. The first phase involved using GRADE to assess the quality of each included study, and assign GRADE scores to each of the outcome areas.30 Data extraction was carried out by one study author directly into a MS Excel 2010 spreadsheet, in which all results were collated. Because of variation in the studies included, and heterogeneity in the populations they described, we adopted a narrative synthesis approach and did not perform a meta-analysis as part of this systematic review.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures of interest were the care-seeking and/or completion rates stratified by sex. Secondary outcome measures included recognition of illness for neonates who were thought to be unwell, and referral and care-completion rates for those who sought care (where these rates were reported).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, implementation or analysis of this work.

Results

Literature search and study inclusion

795 papers were identified by the literature searches, with 181 removed at title screening as duplicates. Of the remaining 614 unique studies, 546 were excluded on title and abstract review (Cohen’s kappa=0.41, moderate agreement between reviewers). Full text screening yielded 14 studies that met our inclusion criteria (Cohen’s kappa=0.83, very good agreement), with a further three papers added based on snowball searches through reference lists. A final total of 17 studies were included (see figure 1). Characteristics of included studies are given in the accompanying online supplementary table 1.

bmjgh-2018-001309supp002.pdf (410.9KB, pdf)

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Of the 17 studies included, 16 were observational (15 non-comparative, cross-sectional, observational analyses and one case-control study). The remaining study was a systematic review. 12 of the studies (all cross-sectional, observational analyses) were based on data drawn from household surveys; three were based on cross-sectional, health facility-based data. Four of the 15 cross-sectional studies were nested within larger randomised-controlled trials. Most studies came from Bangladesh (n=7), with some from India (n=5) and Nepal (n=4), and one (a systematic review) spanning a range of Asian and African countries. Around half of the studies (n=8) reported findings from rural populations; a smaller number (n=4) reported findings from urban, slum-dwelling populations. The remainder reported findings from mixed populations. Study sample sizes varied from 150 to more than 27 000.

Gender differences in care-seeking behaviour and care completion for neonates in South Asia

A majority of studies (n=10) reported numerically on gender-related differences in care-seeking behaviour for neonates.31–40 Of these 10 studies, four reported data from Bangladesh, four from India, one from Nepal and the remaining paper was a systematic review drawing together data from across Africa and Asia. For the eight studies assessing care-seeking rates,31–38 all but one33 found significantly greater care-seeking rates for male neonates than females (across all illness types and to all care providers), with ORs for males ranging from 1.75 to 3.81.35 37 The single study that explicitly differentiated between early and late neonatal periods found that males were less likely to be referred in the 0–7 day timeframe (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.96) but more likely to be referred between eight and 28 days (1.12, 1.06–1.20).37

Two studies assessed care completion rates. One study reported a rate of familial treatment denial (‘leaving against medical advice’) for neonates seen over a period of 3 years at a single neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in India where clinicians had made an explicit recommendation for admission following an initial clinical assessment.40 The odds of familial treatment denial were significantly higher for female neonates when compared with males in this study (OR 3.45, 2.49–4.78).40 Another study, a systematic review of referral completion rates in countries in Africa and South Asia, found statistically significant differences (p<0.001) between early neonatal referral completion rates (53% for male and 39% for female neonates) and overall neonatal referral completion rates in Nepal (54% for males and 41% for female neonates).39

Consultation rates with care providers who were perceived to offer higher quality care were also higher for male than female neonates. However, definitions of quality varied: some studies defined quality care as that offered by clinically (usually medically) qualified practitioners31 32 35–37; in one study, participants viewed private unqualified care as superior to lower cost, public care.33 In one large, cross-sectional survey of neonates registered in a health management information system covering several districts in rural Bangladesh, for example, the adjusted OR of seeking care from a medically qualified professional during the fatal neonatal illness for females was 0.48 (0.25–0.90, p=0.023)—with an equivalent figure for any care provider of 0.43 for females (0.26–0.71, p=0.001).31 A facility-based study from India found an unadjusted OR of care-seeking from qualified health professionals for male neonates of 3.81 (1.05, 13.94).35 In two studies,33 36 this translated into higher household spending on treatment for male neonates compared with females.

Determinants of gender-based differences in care-seeking behaviour

Reasons for gender differentials in care-seeking behaviour were formally tested in two of the included studies.33 37 One of these studies described differences in care-seeking behaviour according to the type of clinical presentation. This large, cross-sectional study from Nepal found that male neonates were more likely than female neonates to be referred for symptoms suggestive of infection or jaundice. The authors suggest a biological cause for differential care-seeking behaviours for males is that males are more susceptible to infection than females particularly in the early neonatal period.37 The second study reported explicitly on gender differentials in illness perception for neonates.33 This study question addressed a population of 255 mothers participating in a randomised controlled trial of an essential newborn care package in rural Uttar Pradesh in India, who became pregnant during the course of the trial.33 Perception of illness necessitating care was found to be significantly lower in households with a female neonate in comparison to a male after controlling for a range of demographic, household and clinical factors (adjusted OR 0.56, 0.33–0.94).

Other studies referred implicitly to determinants of gender-based differences in care-seeking behaviour in their discussions although they did not formally test associations. One cross-sectional study set in urban India using facility-based survey methods40 stratified by sex to explore associations between sociodemographic factors and denial of NICU treatment. The authors found that female neonates denied treatment (by their family) were born to families that had a higher proportion of maternal illiteracy (83% for female neonates vs 13% for males), a previous female child in the family (76% for female neonates and 24% for males) and low (rather than middle/high) socioeconomic status (87% for female neonates and 11% for males) among other factors. Other studies described associations between household composition and care-seeking behaviour by sex. In particular, care-seeking for female neonates was lower in households where the neonate’s sibling(s) were female.4 37 39 40 Two cross-sectional studies reporting on the same study population in a rural district in Nepal, both found that the observed differences in care-seeking were more notable when the family of a female neonate had only female children already. The authors of these studies linked this finding to prevailing social attitudes towards girls among the ethnic groups in Nepal on which they focused: that additional female children are perceived as a burden requiring a dowry at marriage and contributing only to their spouse’s household after marriage.4 37

There was greater agreement on factors influencing neonatal mortality (irrespective of gender). These included maternal education level, birth order and household size41; cultural restrictions on the mobility of women during the neonatal period31; the perceived dominant role of fathers in household decision-making on whether to seek care outside the home (combined with a cultural proclivity to son-preference)32; and whether or not specific forms of antenatal care or postnatal immunisation had been received.39

Discussion

Summary of main findings

There is consistent evidence of gender-differentials in care-seeking behaviour in South Asia, with most included studies broadly agreeing that care-seeking rates for female neonates are lower than for males—particularly so in households where there are older female sibling(s). This preference is further observed in (1) a tendency to seek care for male neonates from providers perceived to offer better qualified care; (2) recurrent care-seeking for males; (3) higher expenditure on male neonates (see table 1). This should, however, be weighed against the broader observation that care-seeking rates for neonates in general across the region are very low, ranging from around 20%32 up to 76%33 for care from any provider, qualified or otherwise.

Table 1.

Summary assessments of evidence relating to each of the outcome areas in this review, and the GRADE strength of the evidence supporting each statement.

| Topic | Summary assessment | GRADE confidence level |

| Gender differences in care-seeking rates among neonates in South Asia | There is some evidence across a number of South Asian countries that care-seeking rates for female neonates are lower than males, especially in those households with older female children. Care-seeking from qualified care providers or those perceived to be of better quality is also greater for male neonates, as are the frequency of consultations and the amount of money spent on care-seeking | Low |

| Gender differences in determinants of care-seeking rates among neonates in South Asia | There is very limited evidence on which specific determinants of care-seeking behaviour are driving differential referral and care-completion rates among male and female neonates. Potential contributors include household composition which is identified as a statistically significant factor in two studies,4 37 and perception of illness necessitating care, which was found to be significantly lower in households with a female neonate in comparison to a male | Very low |

The evidence on determinants of gender differentials in care-seeking behaviour is limited, largely because so few studies carried out meaningful statistical analyses stratified by gender to test associations with other markers. However, data suggest that household composition and illness perception are contributing factors. Perception of illness necessitating care was found to be significantly lower in households with a female neonate in comparison to a male. The probability of care-seeking for male neonates in households with female siblings only was markedly higher than in others—and hints at a continued role for son-preference in determining care-seeking behaviour. This finding is supported by qualitative research findings from India,42 and by the wider literature on care-seeking for infants. A Unicef commissioned report in 2011,43 for example, cites evidence from China where a 1990 census and studies of rural China between 2003 and 2007 show that discrimination against female infants was greatest for those who had older female siblings. It may also reflect the dominant role that males exercise in decision-making on care-seeking within the household in South Asia. Studies indicate that female participation in decisions is often limited even where care-seeking relates to their own care needs.15

The findings of this study support broader evidence of social, economic and cultural norms that give greater value and preference to boys compared with girls, including among migrant populations from South Asia.44–47 There is good evidence from development studies showing that intrahousehold resource allocation and decisions favour boys, as bearers of the family name, lineage and presumed future principal breadwinners.48 Unicef’s State of the World’s Children Report 2016, also highlights the ways in which women and girls are constrained compared with men and boys in relation to education, access to services and their income-earning capacity.49

Only two of the studies that reported differentials in care-seeking behaviour explicitly tested associations with potential explanatory variables stratified by sex. Observations on drivers of care-seeking were mostly restricted to broad comments on the importance of parental gender roles (in particular, the perceived dominance of fathers in decision-making on care-seeking outside the home, and cultural restrictions on the movements of women during the neonatal period), or perceived son preference, but these were not included as proxy variables in any of the analyses.

Strengths and limitations of the study

An important strength of this analysis is that it is the first systematic review to focus explicitly on gender differences in care-seeking behaviour as a driver for differential NMRs in South Asia (as opposed to child mortality more generally). It broadens understanding on this important topic by incorporating pan-regional evidence, and by drawing on grey as well as peer-reviewed literature.

The principal caveats to the findings outlined above are that (1) the evidence base identified was small, (2) data derived mainly from rural settings in particular South Asian countries and not from others, (3) the quality of included studies was in general of low or very low quality. Many studies were excluded at selection phase because they did not report on gender differences in care-seeking or it was not possible to extract data specifically for the neonatal period.43 For those studies that did report on gender differences in care-seeking, only two conducted stratified statistical analyses to help identify determinants of care-seeking by gender.33 37 From a geographical perspective, we found no research from Pakistan, Bhutan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka or the Maldives that met the review criteria, and data from urban settings were limited. Included studies were overwhelmingly observational in design, frequently based on convenience sampling methods (with attendant risk of selection bias) and relied on participant-reported measures (eg, for illness recognition) rather than objective, independently verifiable ones—although some did gather data based on clinical examination in addition. None of the studies incorporated cross-national or cross-area comparisons. The degree of heterogeneity in study populations meant that quantitative synthesis of findings was not possible. Finally, although careful measures were taken in this study to ensure all relevant research was captured, the focus on English-language only papers in particular means that it is possible some relevant literature was missed.

Policy implications and future research directions

Notwithstanding limitations in the evidence base, findings from this study point to potential policy interventions that seek to (1) improve, at the population level, newborn illness recognition and awareness of the importance of care-seeking, (2) improve access to qualified care for all neonates—in particular through focused work with larger households with predominantly female composition and (3) address gender discrimination and inequities at a wider societal level.

Illness recognition and particularly care-seeking rates were strikingly low across included studies, in common with other recent systematic reviews on this topic.24 50 Low public understanding of high-risk clinical presentations in the neonatal period, and the importance of care-seeking, could be ameliorated by appropriately designed information, communication and education campaigns. These should seek to learn from other campaigns and approaches that have sought to influence and change attitudes and behaviours, including campaigns on childhood vaccination,51 sudden infant death syndrome,52 and the ‘Care for Girls’ campaign in China that sought to improve gender equity by focusing on the advantages of having female children.53 As with all such campaigns, they should be part of a multifacetted approach, and should be informed by social science theories and models of behaviour change, and an understanding of the particular beliefs, perceptions and behaviours of the intended audience. The latter can be achieved through actively engaging caregivers and key community members in populations where care-seeking is low, in the design, implementation and evaluation of programmes. This may lead to adjustments in service provision to improve the experiences of, and therefore utilisation by, families, including strategies to reduce the physical, geographic and time barriers that the many vulnerable populations face in accessing services. As well as taking a universal approach, lower care-seeking rates in larger households with predominantly female children suggest a targeted approach from local services to support these families may be required.

The findings of this review are consistent with broader evidence of social, economic and cultural norms that give greater value and preference to boys compared with girls. In order to ensure that interventions to increase care-seeking for both female and male neonates are effective and sustainable, and do not disproportionately benefit males to the detriment of females, action is required to address gender discrimination and inequities at a wider societal level. This should include policy and programmes that seek to empower girls and women, and gender transformative approaches. Engaging men in the role of caregivers to support maternal and child health, for example, will be critical in confronting adverse social norms and reducing the root causes of gender inequities. The creation of legislation and policy approaches that support opportunities to change, and which challenge structural and cultural norms, are also key.

Gender-sensitive health interventions cannot be effective, however, if we do not fully understand gender differences in neonatal health. From a research perspective, there is a pressing need for improved understanding of how gender preference affects care-seeking, and why care-givers in some countries and communities seek medical care for female neonates less often. A striking feature of the evidence considered in this review was the reliance on cross-sectional study design and limited nature of statistical analysis making clear judgement on determinants of gender differences in neonatal care-seeking difficult. Future quantitative work incorporating longitudinal analysis and in particular gender-stratified analyses of determinants of care-seeking could do much to improve the robustness of the evidence base. Qualitative work exploring gender perceptions and drivers of care-seeking behaviour at household level has also been limited to date, and important questions remain regarding which neonates access service resources, at what point (ie, early or late neonatal period) and why (levels and patterns of care), who seeks care on their behalf, who makes the decisions, and how their values are defined (sociocultural norms). Research should seek to better understand the role of women and their sociopolitical empowerment at the household and community level, as well as seeking to empower women in the process of undertaking research. Understanding context-specific household and community-level decision-making dynamics will help to inform the planning, implementation and evaluation of newborn health programmes and policies that challenge gender inequity.

Conclusion

Evidence on gender differences in care-seeking behaviour for neonates in the South Asia region is limited, but across countries there are marked differences in care-seeking behaviour for males and females. Further research is needed, but campaigns, programmes and approaches that seek improve illness perception and access to qualified care, and which address gender discrimination and inequity may yield improvements in population health. Markedly lower care-seeking rates in larger households with predominantly female children suggests that a targeted approach by local services to support these families—especially where contact has already been established in the neonatal period—will be beneficial. The social, economic and cultural norms that giver greater value and preference to boys over girls must also be challenged through the creation of legislation and policy that support greater gender equality, as well as context-specific strategies in partnership with local influencers to change these practices.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks are due to Susan Wray, Assistant Librarian at the Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust for support in running the literature searches on which this paper was based.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: AM, SG, AS and SH conceived the study and devised the research questions. AM then developed the research protocol and identified keywords to support literature searches. AM and SI collated search results, and screened papers based on title and abstract, and ultimately full text—including quality assessment. SI performed the data extraction. All authors contributed to the first draft of the manuscript and to revisions in subsequent versions. AM completed the edit of the revised manuscript.

Funding: This study was carried out independently by the authors without specific funding. SAI was supported by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellowship based at Imperial College London in the UK for part of the time that this study was conducted (Award no ACF-2015-21-024). The Newborn Health Specialist (SG) in Unicef’s Regional Office for South Asia was supported by funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant no SC140844).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: As this study was based purely on secondary analysis of data and involved no primary data collection involving patients or vulnerable groups, ethical approval was neither required nor sought.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data come from peer-reviewed and grey literature sources. Extracted data are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. The Lancet 2012;379:2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. . Levels and trends in child mortality. Report 2015. Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF The state of the world's children 2009: maternal and newborn health. New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenstock S, Katz J, Mullany LC, et al. . Sex differences in neonatal mortality in Sarlahi, Nepal: the role of biology and environment. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:986–91. 10.1136/jech-2013-202646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alkema L, Zhang S, Chou D, et al. . A Bayesian approach to the global estimation of maternal mortality. Ann Appl Stat 2017;11:1245–74. 10.1214/16-AOAS1014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DESA U. Sex differentials in childhood mortality. New York: United Nations, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed SM, Adams AM, Chowdhury M, et al. . Gender, socioeconomic development and health-seeking behaviour in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:361–71. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00461-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basu AM. The status of women and the quality of life among the poor. Camb J Econ 1992;16:249–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen LC, Huq E, D'Souza S. Sex bias in the family allocation of food and health care in rural Bangladesh. Popul Dev Rev 1981;7:55–70. 10.2307/1972764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jejeebhoy SJ, Sathar ZA. Women's autonomy in India and Pakistan: the influence of religion and region. Popul Dev Rev 2001;27:687–712. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00687.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strachan G, Adikaram A, Kailasapathy P. Gender (In)Equality in South Asia: Problems, Prospects and Pathways. SAJHRM 2015;2:1–11. 10.1177/2322093715580222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arnold F, Choe MK, Roy TK. Son preference, the Family-building process and child mortality in India. Popul Stud 1998;52:301–15. 10.1080/0032472031000150486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robitaille M-C. Determinants of stated son preference in India: are men and women different? J Dev Stud 2013;49:657–69. 10.1080/00220388.2012.682986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fikree FF, Pasha O. Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context. BMJ 2004;328:823–6. 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senarath U, Gunawardena NS. Women's autonomy in decision making for health care in South Asia. Asia Pac J Public Health 2009;21:137–43. 10.1177/1010539509331590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhan G, Bhandari N, Taneja S, et al. . The effect of maternal education on gender bias in care-seeking for common childhood illnesses. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:715–24. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Qureshi RN, Sheikh S, Khowaja AR, et al. . Health care seeking behaviours in pregnancy in rural Sindh, Pakistan: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 2016;13 10.1186/s12978-016-0140-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Killewo J, Anwar I, Bashir I, et al. . Perceived delay in healthcare-seeking for episodes of serious illness and its implications for safe motherhood interventions in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;24:403–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Syed U, Khadka N, Khan A, et al. . Care-seeking practices in South Asia: using formative research to design program interventions to save newborn lives. J Perinatol 2008;28(Suppl 2):S9–S13. 10.1038/jp.2008.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chowdhury SK, Billah SM, Arifeen SE, et al. . Care-seeking practices for sick neonates: findings from cross-sectional survey in 14 rural sub-districts of Bangladesh. PLoS One 2018;13:e0204902 10.1371/journal.pone.0204902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, et al. . Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates--a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:952–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D'Souza RM. Role of health-seeking behaviour in child mortality in the slums of Karachi, Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci 2003;35:131–44. 10.1017/S0021932003001317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Terra de Souza AC, Peterson KE, Andrade FMO, et al. . Circumstances of post-neonatal deaths in Ceara, Northeast Brazil: mothers’ health care-seeking behaviors during their infants’ fatal illness. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1675–93. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00100-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herbert HK, Lee ACC, Chandran A, et al. . Care seeking for neonatal illness in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001183 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. Perceptions and health care seeking about newborn danger signs among mothers in rural Wardha. Indian J Pediatr 2008;75:325–9. 10.1007/s12098-008-0032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hildenwall H, Nantanda R, Tumwine JK, et al. . Care-seeking in the development of severe community acquired pneumonia in Ugandan children. Ann Trop Paediatr 2009;29:281–9. 10.1179/027249309X12547917869005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. WHO Newborns: reducing mortality, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality

- 28. Peters SAE, Norton R. Sex and gender reporting in global health: new editorial policies. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e001038 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Awasthi S, Srivastava NM, Agarwal GG, et al. . Effect of behaviour change communication on qualified medical care-seeking for sick neonates among urban poor in Lucknow, Northern India: a before and after intervention study. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:1199–209. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02365.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chowdhury HR, Thompson SC, Ali M, et al. . Care seeking for fatal illness episodes in neonates: a population-based study in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr 2011;11 10.1186/1471-2431-11-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shah R, Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, et al. . Determinants and pattern of care seeking for preterm newborns in a rural Bangladeshi cohort. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14 10.1186/1472-6963-14-417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Willis JR, Kumar V, Mohanty S, et al. . Gender differences in perception and Care-seeking for illness of newborns in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J Health Popul Nutr 2009;27:62–71. 10.3329/jhpn.v27i1.3318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saini AG, Bharti B, Gautam S. Healthcare behavior and expenditure in an urban slum in relation to birth experience and newborn care. J Trop Pediatr 2012;58:214–9. 10.1093/tropej/fmr073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Srivastava NM, Awasthi S, Mishra R. Neonatal morbidity and care-seeking behavior in urban Lucknow. Indian Pediatr 2008;45:229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ahmed S, Sobhan F, Islam A, et al. . And Care‐seeking behaviour in rural Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr 2001;47:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosenstock S, Katz J, Mullany LC, et al. . Sex differences in morbidity and care-seeking during the neonatal period in rural southern Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr 2015;33 10.1186/s41043-015-0014-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halim A, Dewez JE, Biswas A, et al. . When, where, and why are babies dying? neonatal death surveillance and review in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159388 10.1371/journal.pone.0159388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kozuki N, Guenther T, Vaz L, et al. . A systematic review of community-to-facility neonatal referral completion rates in Africa and Asia. BMC Public Health 2015;15 10.1186/s12889-015-2330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kshirsagar VY, Ahmed M, Colaco SM. A study of gender differences in treatment of critically ill newborns in NICU of Krishna Hospital, Karad, Maharashtra. National J Community Med 2013;4:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rahman M, Huq SS. Biodemographic and health seeking behaviour factors influencing neonatal and postneonatal mortality in Bangladesh: evidence from DHS data. East Afr J Public Health 2009;6:77–84. 10.4314/eajph.v6i1.45754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miljeteig I, Sayeed SA, Jesani A, et al. . Impact of ethics and economics on end-of-life decisions in an Indian neonatal unit. Pediatrics 2009;124:e322–8. 10.1542/peds.2008-3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. UNICEF Boys and girls in the life cycle. New York: UNICEF, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Das Gupta M, Zhenghua J, Bohua L, et al. . Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. J Dev Stud 2003;40:153–87. 10.1080/00220380412331293807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Puri S, Adams V, Ivey S, et al. . “There is such a thing as too many daughters, but not too many sons”: A qualitative study of son preference and fetal sex selection among Indian immigrants in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1169–76. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brunson J. Son preference in the context of fertility decline: limits to new constructions of gender and kinship in Nepal. Stud Fam Plann 2010;41:89–98. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00229.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iyer A, Sen G, Östlin P. The intersections of gender and class in health status and health care. Glob Public Health 2008;3(Suppl 1):13–24. 10.1080/17441690801892174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. O'Connell H. Women and the family. Zed Books, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 49. UNICEF The State of the World’s Children 2016: A fair chance for every child. New York: UNICEF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Geldsetzer P, Williams TC, Kirolos A, et al. . The recognition of and care seeking behaviour for childhood illness in developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e93427 10.1371/journal.pone.0093427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hornik R. Public health communication: evidence for behavior change. Routledge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. The Lancet 2010;376:1261–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hesketh T, Lu L, Xing ZW. The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries. CMAJ 2011;183:1374–7. 10.1503/cmaj.101368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2018-001309supp001.pdf (487.6KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2018-001309supp002.pdf (410.9KB, pdf)