Abstract

Introduction

Despite the frequent use of therapies in acute bronchitis, the evidence of their benefit is lacking, since only a few clinical trials have been published, with low sample sizes, poor methodological quality and mainly in children. The objective of this study is to compare the effectiveness of three symptomatic therapies (dextromethorphan, ipratropium or honey) associated with usual care and the usual care in adults with acute bronchitis.

Methods and analysis

This will be a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, open randomised trial. Patients aged 18 or over with uncomplicated acute bronchitis, with cough for less than 3 weeks as the main symptom, scoring ≥4 in either daytime or nocturnal cough on a 7-point Likert scale, will be randomised to one of the following four groups: usual care, dextromethorphan 30 mg three times a day, ipratropium bromide inhaler 20 µg two puffs three times a day or honey 30 mg (a spoonful) three times a day, all taken for up to 14 days. The exclusion criteria will be pneumonia, criteria for hospital admission, pregnancy or lactation, concomitant pulmonary disease, associated significant comorbidity, allergy, intolerance or contraindication to any of the study drugs or admitted to a long-term residence. Sample: 668 patients. The primary outcome will be the number of days with moderate-to-severe cough. All patients will be given a paper-based symptom diary to be self-administered. A second visit will be scheduled at day 2 or 3 for assessing evolution, with two more visits at days 15 and 29 for clinical assessment, evaluation of adverse effects, re-attendance and complications. Patients still with symptoms at day 29 will be called 6 weeks after the baseline visit.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Ethical Board of IDIAP Jordi Gol (reference number: AC18/002). The findings of this trial will be disseminated through research conferences and peer-review journals.

Trial registration number

NCT03738917; Pre-results.

Keywords: infectious diseases, therapeutics, respiratory infections

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Since this is a pragmatic clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of different symptomatic therapies, masking techniques will not be used.

A microbiological study will not be carried out as most cases of acute bronchitis have a viral aetiology, and sputum samples are not routinely collected in the primary care setting.

The main objective as well as some of the secondary objectives of the study are based on information provided by the patients themselves in the symptom diaries. However, clinicians will encourage patients to fill them out appropriately and return them at the different follow-up visits scheduled.

Since one-quarter of patients with uncomplicated acute bronchitis still have cough after the first month, these patients will be followed and called 2 weeks later.

Background

Lower respiratory tract infections are common conditions in primary care. These infections affect approximately 5% of adults per year, and although they occur throughout the year, the incidence is higher in the autumn and winter.1 The most frequent of these infections is acute bronchitis, which is a self-limiting infection of the lower airways that is characterised by clinical manifestations of cough with or without sputum and the absence of symptoms or signs of pneumonia. Other symptoms associated with acute bronchitis include fatigue, wheezing, headache, myalgias, hoarseness and general discomfort.2 As there are no specific diagnostic criteria for acute bronchitis, the diagnosis is primarily clinical and requires thorough assessment for differentiation from pneumonia, as well as other upper respiratory tract infections such as the common cold or sore throat.3 However, cough is not the prominent symptom in the latter infections. Conversely, cough constitutes the most prominent manifestation of acute bronchitis and lasts an average of 3 weeks, but may persist for more than 1 month in 25% of the patients.4 Initially, the cough is non-productive, but after about a week there is an increase in mucus production, and in the second week, the colour of the sputum often changes from grey-white to purulent. Despite being a self-limiting condition, most patients with acute bronchitis seek medical advice, mainly because of bothersome cough.5

Treatment of acute bronchitis is usually symptomatic and is aimed at relieving annoying respiratory symptoms. Treatment should include good hand hygiene, increased fluid intake, avoidance of smoking and the elimination of environmental cough triggers (for instance, dust), and the use of vapours, particularly in low-humidity environments, mainly if symptoms include nasal stuffiness and nasal discharge. Many general practitioners (GPs) prescribe antibiotics, despite evidence of little or no benefit, since up to 90% of acute bronchitis are of viral aetiology, thereby contributing to the emergence of bacterial resistance.6

There are many approaches to the treatment of cough, including analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), expectorants, mucolytics, antihistamines, decongestants, as well as antitussives, β2-agonists or other bronchodilators, alternative therapies and natural treatment.3 In general, these therapies are available as over-the-counter medicines in many countries, and their use is very widespread, particularly in southern European countries. In a recent observational study conducted in 12 European areas, Catalonia was one of the zones with the highest consumption of mucolytics, bronchodilators and antitussives.7

According to the guidelines of the European Respiratory Society, acute cough can be treated with dextromethorphan or codeine, but mucolytics, antihistamines and bronchodilators should not be prescribed in acute lower respiratory tract infections.1 The reviews carried out so far conclude that the benefit of these therapies is lacking. In general, the studies performed had small sample sizes and methodological flaws that make their comparison difficult.8 It should be considered that over-the-counter preparations contain different drugs with a variety of modes of action that can make them difficult to compare.9 Most clinicians recommend the use of analgesics to alleviate mainly fever, headache, myalgia and chest pain. NSAIDs are also frequently prescribed in patients with lower respiratory infections, mainly for relieving cough. However, two recent randomised clinical trials have shown that the number of days with cough among patients taking NSAIDs is not significantly lower than placebo.10 11 Some trials with inhaled corticosteroids have also shown a very marginal benefit, but the number of patients included in these studies was small.12 The clinical efficacy of other symptomatic drugs is also questionable. For example, trials assessing the effect of expectorants and mucolytics have not shown favourable effects on cough associated with acute bronchitis.8 Despite being widely used, antihistamines have been evaluated primarily in the common cold and were not found to be beneficial to alleviate the symptoms of cough.13 Studies assessing the benefits of Echinacea, Chinese herbs, Pelargonium sidoides, ivy leaf extracts and other herbal treatments have obtained contradictory results, mainly in patients with common cold, with low quality of evidence and some problems related to safety, and therefore, they are not recommended in patients with acute bronchitis.14–17

Most studies that have assessed the benefit of antitussives in adults, mainly codeine and dextromethorphan, have been performed in patients with acute cough in the context of upper airway infections, thus limiting the external validity to patients with acute bronchitis. The benefit of dextromethorphan in acute bronchitis is controversial. A review published by Parvez et al, including 451 adults, found that a single dose of dextromethorphan 30 mg reduced the number of cough bouts measured with a microphone by between 19% and 36% within the first 3 hours compared with placebo,18 but a meta-analysis of six studies in adults with upper airway infections found that a single dose of dextromethorphan was slightly more effective than placebo in terms of intensity, effort and latency within the first 3 hours after intake (between 12% and 17% more effective), although the clinical relevance of this observation is unclear.19 Studies carried out with codeine in adults with acute bronchitis have not been shown to be beneficial.20 In children, dextromethorphan has not proven to be more effective than placebo.21 In a Scandinavian study conducted in 50 children followed for 3 days, the average cough score was slightly lower than placebo, although statistically significant differences were not observed between those taking the antitussive and those assigned to placebo.22 Despite this, some guidelines recommend a short course of antitussives to reduce severe cough during acute illness in adults and children over the age of six, but evidence related to their effectiveness remains unclear.23

A non-negligible per cent of patients with acute bronchitis present exaggerated bronchial responsiveness, which is mainly reported when the infection is caused by viruses and atypical germs.24 However, a recent review does not support the routine use of β2-adrenergic inhalers in patients with acute bronchitis.25 On the other hand, in one of the clinical trials included in this review a significant improvement in symptom scores was observed in adults who received fenoterol 0.2 mg four times a day for 7 days when there was bronchial hyper-reactiveness, wheezing or a decrease in the forced expiratory volume in one second compared with the same group of patients who had received placebo. This effect, however, was not observed among patients not presenting airflow obstruction.26 This same effect has been described with inhaled anticholinergics, such as ipratropium and tiotropium alone or associated with β2-agonists, but these studies were primarily conducted in patients with cough due to upper airway infections.27 28 The release of acetylcholine in the airways by parasympathetic stimulation could trigger hyper-reactiveness and increase mucosal secretion on the walls of the airways, and this might explain the possible antitussive properties of inhaled anticholinergic drugs.29 Other drugs such as leukotriene inhibitors have not shown to be useful in acute cough.30 Despite all these limitations, the guidelines recommend that bronchodilators can only be used in patients with bronchial hyper-reactiveness, outweighing the adverse effects, such as tremors or nervousness, that these drugs can cause.31

In recent years, some studies using honey in children have found favourable results on the frequency of cough, patient quality of life and the quality of sleep of both parents and children. In a recent meta-analysis, including six clinical trials and a total of nearly 900 children, honey alleviated cough symptoms compared with no treatment or diphenhydramine, but was not found to be more effective than dextromethorphan. Apart from the limitations of the small sample sizes of these studies, most children received active treatment (different types of honey depending on the studies) for only one night, and studies evaluating their use in adult population are lacking.32 There is no clear evidence that some types of honey have superior antimicrobial properties to others as described in some papers.33 34

Therefore, we believe that this clinical trial is justified, since evidence of the benefit of these treatments in adults with acute bronchitis, with cough as a predominant symptom, is unclear. We prioritise the use of dextromethorphan, as this antitussive is recommended by clinical guidelines at the usual dose of 15 mg three times a day in the adult population, and ipratropium bromide inhalers, since the majority of studies carried out so far have considered β2-agonists, with very poor results on effectiveness, and the fact that anticholinergics are frequently used in primary care in our country. In our study, we want to evaluate the effectiveness of honey at the recommended dose of 30 g three times a day in the adult population, since their benefit has only been explored in paediatrics. Unlike most published studies, these treatments will be recommended for a maximum of 14 days, because as discussed earlier the average duration of symptoms with cough due to acute bronchitis is 3 weeks.

Objectives

The main aim of the trial is to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of adding three symptomatic treatments (dextromethorphan, ipratropium bromide or honey) to usual care in reducing days with moderate-to-severe cough compared with usual care. The secondary objectives are aimed at evaluating the clinical effectiveness of adding three symptomatic treatments to usual care compared with usual care in the reduction of days: (1) with cough, (2) with moderate-to-severe daytime cough, (3) with moderate-to-severe nocturnal cough, (4) severe or moderate symptoms, (5) severe symptoms, (6) until the complete resolution of symptoms, (7) according to the baseline degree of bronchial hyper-reactiveness measured with peak-flow and also (8) to evaluate the utilisation of antibiotics and different symptomatic treatments in the four arms, (9) to evaluate the number of days of absence from work in the four study arms, (10) to assess the number of times patients re-attend for symptoms related to the episode of acute bronchitis, (11) to assess the number of complications related to the episode of acute bronchitis, (12) to assess patient satisfaction in the four study arms and (13) to assess the number of adverse events in the four study arms.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

This study is a phase IV, multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, open randomised trial.

Study arms

Once the patients are included in the trial, they will be randomised into one of the four treatment groups: (1) usual clinical practice group, (2) usual clinical practice +dextromethorphan (15 mg unit), one 15 mg tablet three times a day up to a maximum of 14 days, (3) usual clinical practice +ipratropium bromide (20 µg each puff), two puffs three times a day up to a maximum of 14 days, and (4) usual clinical practice +30 g of honey (one tablespoon) three times a day up to a maximum of 14 days, two 750 mg bottles of wildflower honey (the most frequent type of honey used in our country) will be provided and patients will be recommended to add the honey to a cup of lemon or thyme juice, milk herbal tea, yoghourt, herbal teas, etc. All the drugs and products used in this study are already marketed, and therefore, the manufacturers are responsible for the elaboration and control of samples. The study drugs will be provided free to the participants by the sponsor. The provision, secondary conditioning and distribution of the study drugs and products will be performed by the Barcelona primary care pharmacy service. All the study drugs as well as the honey will be kept at room temperature. To improve compliance, participants will be asked to record their daily dosage in the symptom diary.

Sample size

For the sample size calculation, a recent publication about delayed antibiotic prescribing carried out in Spain using the same symptom diaries with specific data from the group of patients with acute bronchitis has been considered, from which an average duration of 5.5 days of moderate-to-severe cough was obtained, with a SD of 4.5 days.35 Considering a reduction of 1.5 days as a clinically relevant outcome, a sample of 167 patients per group is estimated (a total of 668). The power to detect the difference was assumed to be 0.8, with a two-sided significance level of 0.05. The allocation ratio of subjects into the groups is 1:1:1:1. We expect a 15% of loss to follow-up. Calculations have been performed with the aid of GRANMO software, V.7.12 April 2012 (https://www.imim.cat/ofertadeserveis/software-public/granmo/).

Recruitment

The trial will be conducted in different primary care centres in Catalonia, Spain. A large geographical area of practices throughout Catalonia will be invited to participate to maximise the generalisability of the sample of adults with uncomplicated acute bronchitis and to avoid saturation of research studies in some practices. The recruiting GPs will commence the study in January 2019 and will attempt to recruit all eligible patients until October 2020. Provided the necessary sample is met before this date, the recruitment period will end at the time of the inclusion of the last patient. The sponsor reserves the right to prematurely discontinue this trial at any time in case (1) the expected inclusion objectives are not met or (2) new information appears regarding the efficacy or safety of any of the study medications that could significantly affect the continuation of the trial or overrules the previous positive evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Potential participants who meet the following criteria will be included in this trial: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) symptoms of acute bronchitis, defined as an acute lower-respiratory-tract infection with cough as the predominant symptom, starting within 3 weeks before study inclusion, (3) patients who score ≥4 in either the daytime and/or nocturnal cough on a 7-point Likert scale and (4) patients who consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any of the following criteria will be excluded from this trial: (1) suspected pneumonia; if the professional suspects pneumonia, a chest X-ray will be recommended and the patient will be randomised if this diagnosis is discarded, (2) criteria for hospital admission (impaired consciousness, respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, pulse >125 beats/min, systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure <60 mm Hg, temperature >40°C or oxygen saturation <92%), (3) pregnancy or breast feeding, (4) baseline respiratory disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, tuberculosis or bronchiectasis, (5) associated significant comorbidity, such as moderate-to-severe heart failure, dementia, acute myocardial infarction/recent cerebral vascular accident (<3 months), severe liver failure, severe renal failure, (6) immunosuppression, such as chronic infection by HIV, transplanted, neutropenic, or patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment, (7) active neoplasm, (8) terminal illness, (9) history of intolerance or allergy to any of the study treatments, (10) patients in whom, in the opinion of the investigator, treatment with dextromethorphan, ipratropium bromide or honey is contraindicated, (11) patients living in long-term institutions and (12) difficulty in conducting scheduled follow-up visits.

Following the usual clinical practice, participating GPs may prescribe the concomitant therapy they consider appropriate, including analgesics such as NSAIDs or paracetamol, mucolytics, expectorants, antihistamines and also antibiotics. However, they will not be allowed to prescribe antitussives, including codeine, anticholinergic inhalers and they will not be allowed to recommend the use of honey, including honey candies, tablets or infusions with honey. All drug information (name of product, purpose of administration, dosage, duration of administration, etc) will be recorded on the patient case report form (CRF) and patients will fill out any other treatment they obtain or purchase from the pharmacy in their symptom diaries.

Randomisation

Patients will be assigned sequentially as they enter the study. Randomisation of patients will be performed by registering the patient in an electronic CRF during the index visit. Patients will be stratified based on the previous duration of symptoms (≤1 week, >1 week). Once a patient is included in the trial and the randomisation has been centrally made, the investigator will provide the assigned treatment and record the dispensing and medication code in the electronic CRF. Since this is a multicentre study, a block procedure will be performed to assign patients to each of the health centres at a 1:1:1:1 ratio.

Blinding

This is an open study. Neither physicians nor patients will be blind to the patient’s assignment to the study group. The open nature of the clinical trial ensures that the results obtained in this study are very close to the reality of primary care, considering that both the participating GPs and the patients with uncomplicated acute bronchitis will be aware of the treatment given. However, the main outcome will be assessed by the patients themselves.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Duration (days) of moderate-to-severe cough in days. Each symptom will be scored by the patient on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = not affected, 1 = very little problem, 2 = slight problem, 3 = moderately bad, 4 = bad, 5 = very bad, 6 = as bad as it could be). The number of days until the last day the patient scores 3 in either daytime cough or nocturnal cough in the paper-based symptom diary will be considered for the main outcome. We will use validated questionnaires, which have also been used in a previous study.36

Secondary outcomes

Different secondary outcomes will be taken into account: (1) duration of symptoms (number of days until the last day the patient scores 2 in any of the symptoms), (2) duration of moderate-to-severe daytime cough (number of days until the last day the patient scores 3 in daytime cough), (3) duration of moderate-to-severe nocturnal cough (number of days until the last day the patient scores 3 in nocturnal cough), (4) duration of cough (number of days until the last day the patient scores 2 in either daytime or nocturnal cough), (5) duration of severe symptoms (number of days until the last day the patient scores 5 in any of the symptoms), (6) duration of moderate-to-severe symptoms (number of days until the last day the patient scores 3 in any of the symptoms), (7) duration of moderate-to-severe cough in days according to the basal degree of bronchial hyper-reactiveness at the baseline visit, measured with peak flow (the greatest of three determinations will be considered), (8) utilisation of antibiotics and other symptomatic therapies within the first 4 weeks, (9) duration of work or school absenteeism due to the episode of acute bronchitis, (10) number of re-attendances to any doctor regarding the episode of acute bronchitis within the first 4 weeks, (11) number of complications related to the episode of acute bronchitis within the first 4 weeks, such as pneumonias, visits to emergency departments, hospital admissions, (12) patient satisfaction and (13) adverse reactions.

Withdrawal

Patients will be free to withdraw from the study at any time for any reason without prejudice to future care, and with no obligation to provide the reason for withdrawal. In addition, the investigator may withdraw a participant from the trial at any time if deemed necessary by any of the following reasons: (1) intercurrent process or illness that in the opinion of the investigator requires the withdrawal of the patient’s treatment, (2) the presence of an adverse event that requires the withdrawal of the patient’s treatment, (3) those who require a concomitant treatment not allowed during study participation (antitussives, anticholinergic inhalers, honey) or (4) protocol violation.

During the trial, patients will be asked to inform about any signs of worsening symptoms, and investigators will evaluate appropriate measures if they need additional therapy. Since this is a pragmatic trial, patients who decide interrupting the study drug treatment but want to continue with the study procedures, will be followed in the same way as the other patients.

Data management and monitoring

The investigators will follow the standard operating procedures of the trial for better quality of assessment and outcome data collection. The investigators who evaluate outcome measures should be restricted to only those GPs who have attended the training meetings. All assessment data and case reports will be collected at baseline (day 1) and at the various follow-up visits in the intervention arms and control group. Collected documents and data will be managed by electronic CRF. Only the principal investigator or those who have permission will be able to access the data. The CRFs and other documents will be stored at a separate and secure location for 25 years after trial completion. Multicentre clinical trial monitoring will be conducted via periodic on-site/online visits, and all the patients recruited will be monitored following a risk approach monitoring plan.

Ascertainment of visits

The patients will be randomised to one of the four treatment strategies. To standardise data collection, all of the participating GPs will be trained by the coordinating centre. The patients will receive information on the study by the participating GPs, and if they are interested in participating, they will be provided with an informed consent form to read and sign. A maximum length of 10 to 15 min is expected for the interview, randomisation and the introduction of the data. The participating GPs will explain the study scheme and the visit programme to the patient (table 1). After randomisation, information on the strategy to which they have been allocated will be given to the participants, and they will be given the free study medication and will be informed as to the appropriate measures to take in case of worsening or no improvement of their condition. In addition, they will be given a paper-based diary to be completed by themselves on a daily basis. The information collected in the diary includes: times in which study medication is taken, concomitant treatments used and a questionnaire of symptoms, which has been previously used in other studies.35 Patients will complete the diary while symptoms related to the respiratory condition are present.

Table 1.

Timetable of study period

| Day | Day 1 | Day 2 to 4 | Day 15 | Day 29* | Day 43† | |

| Visit | Visit 1 | Phone visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Phone visit 2 | Phone visit 3 |

| Visit at the centre | X | X | X‡ | |||

| Medical history and physical examination | X | |||||

| Explanation of the study and informed consent | X | |||||

| Initial CRF | X | |||||

| Randomisation | X | |||||

| Dispensing the study treatment | X | |||||

| Peak flow determination | X | |||||

| Giving out of the first symptom diary, up to day 15 | X | |||||

| Assessment of the clinical outcome | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Adherence to the study drug | X | X | ||||

| Evaluation of adverse events | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Collection of the first symptom diary and giving out of the second symptom diary from day 16 to day 29§ | X | |||||

| Collection of the second symptom diary | X | |||||

| Evaluation of re-attendance to healthcare services due to infectious condition | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Evaluation of complications | X | X | X | X | X | |

*Final visit if the symptoms have disappeared.

†Only if the visit at day 29 is at the centre and a cure or improvement is recorded.

‡Phone visit if a cure is recorded at day 15.

§Only if the patient still has symptoms of infection (improvement).

CRF, case report form.

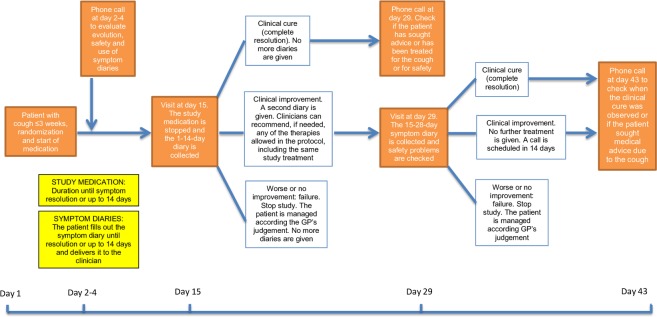

GPs will call patients 2 to 3 days after their inclusion in the study to monitor their progress and resolve possible doubts regarding the completion of the diary. Patients will be scheduled for a second visit at day 15 (2 weeks after the patient inclusion) to evaluate their clinical evolution. Depending on the patient’s clinical evolution, the follow-up will be different: (1) clinical cure, defined as absence of symptoms; the diary will be collected and they will be called 2 weeks later to check if they have sought medical advice again due to the episode of acute bronchitis, (2) clinical improvement, defined as the persistence of symptoms but with improvement with respect to the index visit. Patients will be given a new symptom diary to be completed in the following 14 days and will be asked to return at day 29 to evaluate their condition. Participating GPs may prescribe any of the medications allowed by the study protocol, the same treatment as that which was previously received by the patient, or nothing if not necessary. If the doctor deems it necessary to prescribe any of the therapies under study (with the exception of the arm in which the patient is located), the patient will discontinue the trial and follow the usual clinical practice, (3) failure, when the patient is worse or presents the same symptoms as those presented at the index visit; patients will be withdrawn from the study and will be managed according to the clinician’s best judgement. At day 29, patients who improved at day 15 will be similarly categorised as (1) clinical cure, (2) improvement or (3) failure. Patients with clinical cure or improvement will be contacted again at day 43 (6 weeks after the baseline visit) to record if they have consulted with a professional regarding the episode of cough and to assess safety (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study scheme. GPs, general practitioners.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study population will be described using frequencies for categorical variables and mean and SD for quantitative variables. To compare the different strategies with the usual treatment, we will use the chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Student t-test and variance analysis for continuous variables. Effectiveness evaluation will be primarily based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis in such a way that any event in any patient will be included in the group to which the patient was randomised, and per protocol (PP) analysis will be used as a secondary analysis. ITT analysis will be conducted in all subjects randomised, and PP analysis will be conducted in those who complete the entire trial without violating the protocol.

To avoid the effect of potential confounders, the effectiveness of each treatment with respect to the usual clinical practice will be analysed through Cox proportional risk survival analysis, reporting both crude and adjusted relative risk. The effect of the treatment will be adjusted for variables collected at baseline, such as age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, peak-flow measurement, previous treatment, previous vaccination, comorbidity and previous number of acute bronchitis.

Censoring and missing data: Those who discontinue, miss follow-up or, for whatever reason, are not evaluated for the main variable will be considered censored at the last follow-up date. In addition, patients who do not show symptoms of improvement along the study will also be censored at the last day of follow-up. We do not plan to make imputation of missing data.

Sub-analysis: To assess the consistency of the data collected by telephone (in subjects not attending the visit of the 15th and 29th), a sub-analysis will be carried out using only the data from the diary. A sub-analysis with the patients taking antibiotics will also be studied.

All the analyses will be done with the statistical software R (V.3.2 or higher) and the level of significance will be 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public are not actively involved in the process of this study. However, the participants will be informed of the study results at the end of the trial.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical issues

The trial will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines. If the protocol needs relevant modifications, the investigators are required to inform the institutional review board (IDIAP Jordi Gol, Barcelona, Spain) and the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Healthcare Products as well as participants and receive reapproval. Before the trial, investigators are required to provide all information related to the clinical trial to every patient, including the possible benefits and harms, other therapeutic choices and right to withdraw, via a written consent form approved by the institutional review board. After being provided with enough time and opportunity to ask questions and decide whether or not to participate, written informed consent will be obtained from all participants before study inclusion. Data confidentiality will be ensured at all times, as stated in the researcher’s commitment sheet, as will compliance with the current legislation regarding the protection of personal data. This is a clinical trial based on the outpatient setting, and neither patients nor researchers will receive any monetary compensation.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

This is a low intervention clinical trial meaning that the drugs administered are used in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorisation with a well-known safety profile and that the intervention on the patient poses no additional risk to the subject compared with usual clinical practice. The study medications used in this clinical trial have been widely prescribed and consumed for a long time, and the safety profile of these drugs is well-documented.

Adverse events will be recorded and followed if they are found to be serious or/and related to the study drug. The occurrence of this kind of adverse events will be monitored. The rest of the adverse events will be treated as they are during the normal clinical practice, but will not be collected in the CRF.

Dissemination

A range of dissemination activities are planned at national and international conferences. At the end of the trial, we will publish the final report in an open access peer-review journal even in the case of negative results, and the study results will also be disseminated via conference presentations. A summary of the findings will be sent to the participating practices on completion of the acute bronchitis 4 treatments (AB4T) study, and the participants will also be informed of the results.

Discussion

Acute bronchitis is the most common respiratory tract infection seen in outpatient departments as approximately 5% of the general population develop this infectious condition. Despite problems associated with antibiotic overuse in Western countries and the substantial economic burden associated with acute bronchitis, currently no definitive medication is recommended. There are many studies exploring the efficacy of symptomatic therapies, but different systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of antitussives, bronchodilators, herbs and natural remedies found that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of these treatments because of the high risk of bias, small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of the patients included in these studies as many of these patients had an infection other than acute bronchitis. This study is a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, open randomised placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of usual care plus three different symptomatic treatments that are widely consumed by patients with acute cough due to an uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infection in a rigorous and adequately powered study.

There are some limitations to this protocol. A microbiological study is not carried out, but since nearly 90% of the episodes of acute bronchitis are of viral aetiology, treatment with antibiotics is not indicated and the microbiological study is therefore not necessary, similar to the usual practice in primary care, in which this procedure is not routinely performed. In addition, the study is pragmatic and replicates current primary care. It is an open and unblinded study, in which doctors and patients will know the randomised study treatment assigned. The main objective of this study, as well as some of the secondary objectives are based on information provided by the patients themselves in the symptom diaries. However, at the baseline visit, GPs will be encouraged to explain how to fill in the diaries and will supervise how patients register the symptom diary. They will ask patients to return them at the various follow-up visits (days 15 and 29). We have previously found that the diary return rate is greater if we make patients come to follow-up visits. Notwithstanding, in the case of patients not returning the diaries, the doctor will contact them by phone to complete a short form in which the main study variables will be collected, in an attempt to minimise the number of losses.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JMC, AGS, RM and CL drafted the research protocol and both AGS and CL wrote the manuscript. AM, AGS, RM, HP, AGL and CL were involved in the protocol development. JMC, AM, JP, CB, MPA and CL will be involved in trial conduct and recruitment. DO contributed to the statistical design and analysis. All authors have contributed to the conception of this clinical trial.

Funding: The AB4T study received a research grant from the Carlos III Institute of Health (ISCIII), Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain), awarded on the 2017 call under the Health Strategy Action 2013-2016, within the National Research Program oriented to Societal Challenges, within the Technical, Scientific and Innovation Research National Plan 2013-2016, with reference PI17/01345, co-funded with European Union ERDF funds (European Regional Development Fund). This study is also supported by the Spanish Clinical Research Network (SCReN), funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación, project number PT17/0017/0005, within the National Research Program I+D+I 2013-2016 and co-funded with European Union ERDF funds (European Regional Development Fund).

Competing interests: AM and CL report receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics.

Ethics approval: Ethical Board of IDIAP Jordi Gol (reference number: AC18/002).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, et al. . Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections--full version. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17(Suppl.6):E1–59. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03672.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Gard P, et al. . Prospective study of the incidence, aetiology and outcome of adult lower respiratory tract illness in the community. Thorax 2001;56:109–14. 10.1136/thorax.56.2.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician 2010;82:1345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tackett KL, Atkins A. Evidence-based acute bronchitis therapy. J Pharm Pract 2012;25:586–90. 10.1177/0897190012460826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Investigation of "non-responding" presumed lower respiratory tract infection in primary care. BMJ 2011;343:d5840 10.1136/bmj.d5840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith SM, Fahey T, Smucny J, et al. . Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD000245 10.1002/14651858.CD000245.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamoen M, Broekhuizen BD, Little P, et al. . Medication use in European primary care patients with lower respiratory tract infection: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e81–91. 10.3399/bjgp14X677130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD001831 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morice A, Abdul-Manap R. Drug treatments for coughs and colds. Prescriber 1998;9:74–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Llor C, Moragas A, Bayona C, et al. . Efficacy of anti-inflammatory or antibiotic treatment in patients with non-complicated acute bronchitis and discoloured sputum: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2013;347:f5762 10.1136/bmj.f5762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Little P, Moore M, Kelly J, et al. . Ibuprofen, paracetamol, and steam for patients with respiratory tract infections in primary care: pragmatic randomised factorial trial. BMJ 2013;347:f6041 10.1136/bmj.f6041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Gohary M, Hay AD, Coventry P, et al. . Corticosteroids for acute and subacute cough following respiratory tract infection: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2013;30:492–500. 10.1093/fampra/cmt034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Björnsdóttir I, Einarson TR, Gudmundsson LS, et al. . Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review. Pharm World Sci 2007;29:577–83. 10.1007/s11096-007-9122-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yale SH, Liu K. Echinacea purpurea therapy for the treatment of the common cold: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1237–41. 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Timmer A, Günther J, Motschall E, et al. . Pelargonium sidoides extract for treating acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;10:CD006323 10.1002/14651858.CD006323.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang L, Li K, Wu T. Chinese medicinal herbs for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2:CD004560 10.1002/14651858.CD004560.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holzinger F, Chenot JF. Systematic review of clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of ivy leaf (hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:1–9. 10.1155/2011/382789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parvez L, Vaidya M, Sakhardande A, et al. . Evaluation of antitussive agents in man. Pulm Pharmacol 1996;9:299–308. 10.1006/pulp.1996.0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pavesi L, Subburaj S, Porter-Shaw K. Application and validation of a computerized cough acquisition system for objective monitoring of acute cough: a meta-analysis. Chest 2001;120:1121–8. 10.1378/chest.120.4.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freestone C, Eccles R. Assessment of the antitussive efficacy of codeine in cough associated with common cold. J Pharm Pharmacol 1997;49:1045–9. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paul IM, Yoder KE, Crowell KR, et al. . Effect of dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, and placebo on nocturnal cough and sleep quality for coughing children and their parents. Pediatrics 2004;114:e85–e90. 10.1542/peds.114.1.e85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Korppi M, Laurikainen K, Pietikäinen M, et al. . Antitussives in the treatment of acute transient cough in children. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991;80:969–71. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braman SS. Chronic cough due to acute bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:95S–103. 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.95S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Melbye H, Kongerud J, Vorland L. Reversible airflow limitation in adults with respiratory infection. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1239–45. 10.1183/09031936.94.07071239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Becker LA, Hom J, Villasis-Keever M, et al. . Beta2-agonists for acute cough or a clinical diagnosis of acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;9:CD001726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melbye H, Aasebø U, Straume B. Symptomatic effect of inhaled fenoterol in acute bronchitis: a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Fam Pract 1991;8:216–22. 10.1093/fampra/8.3.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higenbottam TW. Anticholinergics and cough. Postgrad Med J 1987;63(Suppl 1):75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zanasi A, Lecchi M, Del Forno M, et al. . A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial on the management of post-infective cough by inhaled ipratropium and salbutamol administered in combination. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014;29:224–32. 10.1016/j.pupt.2014.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coulson FR, Fryer AD. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and airway diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2003;98:59–69. 10.1016/S0163-7258(03)00004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang K, Birring SS, Taylor K, et al. . Montelukast for postinfectious cough in adults: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:35–43. 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70245-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cayley WE. Beta2 Agonists for Acute Cough or a Clinical Diagnosis of Acute Bronchitis. Am Fam Physician 2017;95:551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oduwole O, Udoh EE, Oyo-Ita A, et al. . Honey for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4:CD007094 10.1002/14651858.CD007094.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khan RU, Naz S, Abudabos AM. Towards a better understanding of the therapeutic applications and corresponding mechanisms of action of honey. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2017;24:27755–66. 10.1007/s11356-017-0567-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lusby PE, Coombes AL, Wilkinson JM. Bactericidal activity of different honeys against pathogenic bacteria. Arch Med Res 2005;36:464–7. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de la Poza Abad M, Mas Dalmau G, Moreno Bakedano M, et al. . Prescription Strategies in Acute Uncomplicated Respiratory Infections: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:21–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de la Poza Abad M, Mas Dalmau G, Moreno Bakedano M, et al. . Rationale, design and organization of the delayed antibiotic prescription (DAP) trial: a randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies in the non-complicated acute respiratory tract infections in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:63 10.1186/1471-2296-14-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.