Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence, clustering and sociodemographic distribution of non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors in adolescents in Nepal.

Design

Data originated from Global School Based Student Health Survey, Nepal conducted in 2015–2016.

Setting

The study sites were the secondary schools in Nepal; 74 schools were selected based on the probability proportional to school enrolment size throughout Nepal.

Participants

5795 school-going children aged 13–17 years were included in the study.

Primary outcomes

NCD risk factors: smoking, alcohol consumption, insufficient fruit and vegetable intake, insufficient physical activity and overweight/obesity were the primary outcomes. Sociodemographic distributions of the combined and individual NCD risk factors were determined by Poisson regression analysis.

Results

Findings revealed the prevalence of smoking (6.04%; CI 4.62 to 7.88), alcohol consumption (5.29%; CI 4.03 to 6.92), insufficient fruit and vegetable intake (95.33%; CI 93.89 to 96.45), insufficiently physical activity (84.77%; CI 81.04 to 87.88) and overweight/obesity (6.66%; CI 4.65 to 9.45). One or more risk factors were present in 99.6%, ≥2 were in 83% and ≥3 were in 11.2%. Risk factors were more likely to cluster in male, 17 years of age and grade 7. Prevalence of smoking (adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR)=2.38; CI 1.6 to 3.51) and alcohol consumption (aPR=1.81; CI 1.29 to 2.53) was significantly high in male, and in 16 and 17 years of age. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity and overweight/obesity was significantly lower in higher grades.

Conclusion

Insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient physical activity were highly prevalent in the populations studied. Risk factors were disproportionately distributed and clustered in particular gender, age and grade. The study population requires an age and gender specific preventive public health intervention.

Keywords: adolescents, alcohol, fruit and vegetable intake, obesity, physical activity, smoking, Nepal

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to assess the clustering and sociodemographic distribution of non-communicable disease risk factors in Nepalese adolescents.

Respondents are the national representative sample of grade 7–11 school children in Nepal.

Information collected from past events is subject to errors and recall bias.

Study findings should cautiously be generalised to out-of-school adolescents.

Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death worldwide accounting for 71% deaths globally.1 Most of these deaths (31.5 million out of 40.5 million) occur in low income and middle income countries (LMICs) like Nepal.1 2 NCDs are also the major cause of morbidity and are responsible for devastating, long-term economic consequences for individuals and households in LMICs.1 3 In Nepal, the rate of deaths due to NCDs is increasing; out of total deaths, NCDs were responsible for 60% deaths in 20144 and 66% deaths in 2016.5

Most of the NCDs have a causal link with behavioural and metabolic risk factors including smoking, harmful use of alcohol, low physical activity, unhealthy diets and overweight/obesity.6 Overweight, for example, contributes 44% of diabetes, 23% of ischaemic heart disease and 7%–41% of certain cancer burdens globally.6 Recent review articles indicate that NCD risk factors are highly prevalent among adolescents in LMICs. The findings showed that 13.6% are current tobacco users7; 25% indulges to episodic drinking8; 80% are physically less active9; and 8.5% are obese.10 An accumulating body of literature suggests that early age exposure to behavioural risk factors increases the risk of developing NCDs at later ages.6 11 12

Clustering of NCD risk factors, on the other hand, multiply the risk of developing diseases and mortality.13 For instance, the incidence of ischaemic heart disease rose from 0% to 40% as the number of risk factors increased from 0 to 5.14 Similarly, having hypertension in an individual with diabetes was associated with a 72% increase in risk of all-cause death and a 57% increase in risk of any cardiovascular event.15

Likewise, risk profile and incidence of NCDs can significantly vary with different sociodemographic factors.6 16 17 In most countries, more boys than girls and more adolescents aged 14–15 years than those aged 12–13 years were likely to be current tobacco users.7 Similarly, the prevalence of alcohol consumption was higher for boys than girls, and higher at age 14–15 years than at 12–13 years.8

A few of our previous studies discussed the clustering, and age, sex and geographical variation of NCD risk factors in adults.18 19 However, no information is available on the prevalence and clustering of NCD risk factors in Nepalese adolescents. Even scarcer is our understanding of their sociodemographic distributions in this population. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude and distribution of five major NCD risk factors, individually or as a cluster, in adolescents in Nepal. This paper will have important policy implications in terms of identifying the at-risk population and implementing targeted interventions for primordial and primary prevention of NCDs among school-going children in Nepal. Furthermore, exploring clustering phenomena will facilitate the design of integrated approaches to tackle multiple risk factors in a cost-effective way.

Methods

Data source, study participants and sampling

We used the data from the first Global School Based Students Health Survey (GSHS), Nepal conducted between 2015 and 2016. The cross-sectional survey was carried out in assistance of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO using globally standardised methodology.20 The purpose of the GSHS survey is to assess the health behaviours of adolescents globally using standardised procedures across countries.

The GSHS had the nationally representative sample of all school-going children in Nepal. The survey participants consisted of a total 6529 school children selected from grades 7 to 11 of 74 schools throughout Nepal using a two-stage cluster sampling method. The number of the participants from grade 11 was comparatively small as only selected schools had upgraded themselves as higher secondary schools (school with grades 11–12). Details of the sampling procedure and survey reports are available elsewhere.21 Our study included 5795 of 6529 participants aged between 13 and 17 years.

Data collection

The GSHS survey uses the same standardised self-administered questionnaires globally. The 58 core and 33 expanded questions aim to collect different aspects of health related information including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, dietary behaviours and physical activity. To assess the NCD risk factors profile, we extracted data related to current smoking, current alcohol user, fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity, overweight and obesity for this study and redefined them based on the standard criteria.

The survey defines current smoking as smoking for at least 1 day during the past 30 days.22 Similarly, current alcohol users were those who had had at least one drink of alcohol during the 30 days before the survey.23 The cut-off for sufficient physical activity was being physically active at least 60 min per day during the 7 days before the survey.24 Likewise, eating fruit and vegetable for five and more times per day was regarded as sufficient intake.25 Overweight and obesity definitions correspond to the WHO criteria of +1 SD and +2 SD from the median for body mass index (BMI), respectively.26

Data analysis

We used the GSHS information on primary sample units, strata and sampling weight to construct the complex survey weight and performed data analysis using STATA software V.15.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). All estimates are presented with 95% CIs. Sociodemographic distribution and clustering of NCD risk factors are presented graphically. To better understand the independent effects of covariates on risk factor clustering within individuals, we considered the number of NCD risk factors present in each participant as count data and applied multiple Poisson regression to report the adjusted relative risk (aRR) of having x number risk factors. We used the same analytical method for testing the differences in the prevalence of NCD risk factors and reported the adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) across age, gender and education as suggested by Barros and Hirakata.27 A p value <0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Ethics

Prior to student participation in the survey, administrative permission from respective schools and informed consent from the student’s parent were obtained ensuring voluntary participation, privacy and confidentiality.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of this study, and nor were members of the general public.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 5795 participants, 51% were female. The majority of the participants were aged between 13 and 15 years (13 years, 23%; 14 years, 29%; 15 years, 23%) (table 1). Participants were almost equally distributed among grades 7, 8, 9 and 10, with the lowest representation from grade 11 (2%). Mountain region had the highest weighted proportion of the participants (49.3%), followed by Hill (42.9%) and Tarai (7.8%). No statistically significant gender variations were observed in age, education and ecological region (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics by gender (n=5795)

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Male | Female | Total | P value |

| n+ (%++) | n+ (%++) | n+ | ||

| Age (in year) | ||||

| 13 | 526 (46.91) | 639 (53.09) | 1165 | 0.07 |

| 14 | 667 (46.41) | 812 (53.59) | 1479 | |

| 15 | 651 (48.78) | 782 (51.22) | 1433 | |

| 16 | 565 (54.5) | 534 (45.5) | 1099 | |

| 17 | 259 (52.56) | 247 (47.44) | 506 | |

| Education (in grade) | ||||

| 7 | 500 (49.62) | 488 (50.38) | 988 | 0.59 |

| 8 | 753 (49.50) | 877 (50.50) | 1630 | |

| 9 | 636 (49.90) | 803 (51.11) | 1439 | |

| 10 | 725 (37.58) | 762 (62.42) | 1487 | |

| 11 | 45 (49.0) | 68 (51.0) | 113 | |

| Ecological region | ||||

| Mountain | 842 (49.02) | 961 (50.98) | 1803 | 0.76 |

| Hill | 955 (48.75) | 991 (51.25) | 1946 | |

| Tarai | 884 (50.27) | 1071 (49.73) | 1955 | |

Note: +, unweighted frequency; ++, weighted percentage.

Prevalence and clustering of NCD risk factors

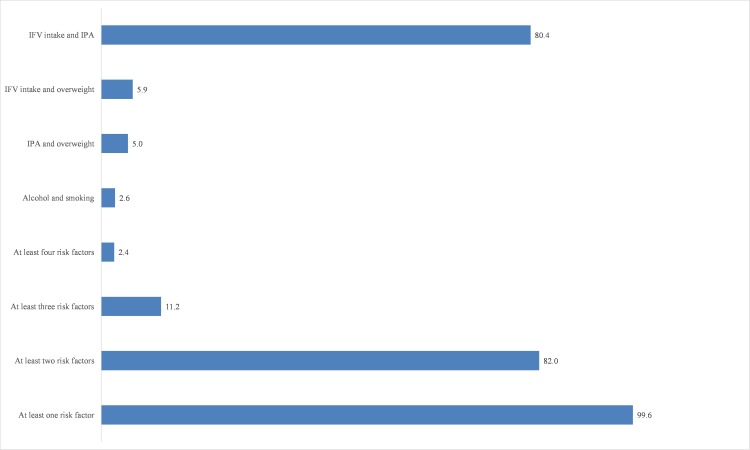

The prevalence of current smoking and alcohol consumption were 6.04% (4.62–7.88) and 5.29% (4.03–6.92), respectively (table 2). The prevalence was 95.33% (93.89–96.45) in the case of insufficient fruit and vegetable intake. More than two-thirds of the participants were not sufficiently active. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 6.66% (4.65–9.45), where 0.6% of the participants were obese. Nearly all participants (99.6%) had at least one NCD risk factor, whereas 82% were with at least two risk factors and 11.2% with at least three risk factors (figure 1). A very small proportion of the participants (2.4%) possessed at least four risk factors. Smoking and alcohol was present in 2.6%, insufficient physical activity and overweight/obesity was seen in 4.8% and insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and overweight/obesity was observed in 5.9% of the participants (figure 1).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic distribution of NCD risk factors

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Smoking | Alcohol consumption | Insufficient fruit and vegetable | Insufficient physical activity | Overweight and obesity |

| % (CI) | % (CI) | % (CI) | % (CI) | % (CI) | |

| Total | 6.04 (4.62 to 7.88) | 5.29 (4.03 to 6.92) | 95.33 (93.89 to 96.45) | 84.77 (81.04 to 87.88) | 6.66 (4.65 to 9.45) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 8.44 | 6.74 | 96.19 | 82.59 | 7.04 |

| Female | 3.43 | 3.61 | 94.54 | 86.60 | 5.25 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Age group (in years) | |||||

| 13 | 2.63 | 2.97 | 96.65 | 87.48 | 10.31 |

| 14 | 6.43 | 5.71 | 94.44 | 86.89 | 6.01 |

| 15 | 5.41 | 4.79 | 95.55 | 82.50 | 3.99 |

| 16 | 8.31 | 6.85 | 95.11 | 81.21 | 5.21 |

| 17 | 10.02 | 7.68 | 94.68 | 83.98 | 3.31 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.025 | <0.01 |

| Education (in grade) | |||||

| 7 | 6.46 | 6.48 | 93.87 | 93.24 | 10.84 |

| 8 | 6.14 | 3.85 | 95.19 | 87.41 | 4.69 |

| 9 | 5.41 | 5.29 | 96.03 | 81.11 | 5.49 |

| 10 | 6.57 | 5.92 | 95.74 | 76.90 | 3.41 |

| 11 | 4.61 | 5.56 | 96.17 | 78.61 | 9.51 |

| P value | 0.87 | 0.58 | 0.48 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| Ecological region | |||||

| Mountain | 5.21 | 4.74 | 95.87 | 87.51 | 5.56 |

| Hill | 7.23 | 6.16 | 94.65 | 81.71 | 7.12 |

| Tarai | 4.83 | 4.06 | 95.69 | 84.14 | 3.77 |

| P value | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 0.44 |

NCD, non-communicable disease.

Figure 1.

Clustering of NCD risk factors. Alcohol, current alcohol users; IFV intake, insufficient fruit and vegetable intake; IPA, insufficient physical activity; Smoking, current smoking. NCD, non-communicable disease.

Males were more likely to experience NCD risk factors than females (aRR=1.05; CI 1.01 to 1.09). Compared with the participants having 13 years of age, the risk ratios were greater than 1 for all higher age groups except 15 years one, but only 17 years of age was significantly associated with 8% increased likelihood of getting the risk factors (table 3). The adjusted risk ratio was significantly lesser in 8 (aRR=0.94; CI 0.89 to 0.98), 9 (aRR=0.92; CI 0.85 to 0.99), 10 (aRR=0.88; CI 0.82 to 0.95) and 11 (aRR=0.89; CI 0.81 to 0.99) grade participants in reference to the grade 7 students. The NCD risk factors prevalence were not significantly varied with the ecological region.

Table 3.

Clustering of NCD risk factors by sociodemographic characteristics (Poisson regression analysis)

| Sociodemographic characteristic | Mean of risk factors | aRR (CI) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.84 | Reference |

| Male | 1.94 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09)* |

| Age group (in years) | ||

| 13 | 1.94 | Reference |

| 14 | 1.92 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) |

| 15 | 1.82 | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) |

| 16 | 1.89 | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) |

| 17 | 1.95 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14)* |

| Education (in grade) | ||

| 7 | 2.05 | Reference |

| 8 | 1.91 | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.98)** |

| 9 | 1.85 | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99)* |

| 10 | 1.79 | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95)** |

| 11 | 1.88 | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.99)* |

| Ecological region | ||

| Mountain | 1.92 | Reference |

| Hill | 1.89 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.05) |

| Tarai | 1.85 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) |

*P<0.05; **P<0.01.

aRR, adjusted relative risk; NCD, non-communicable disease.

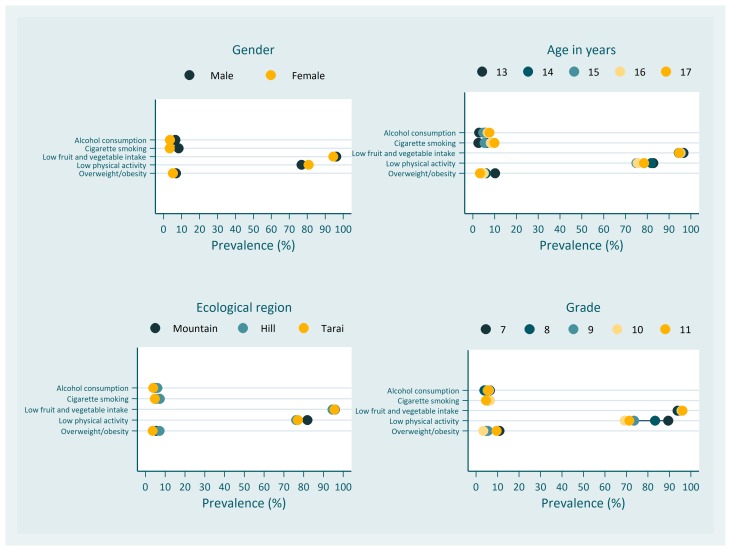

Sociodemographic distribution of the NCD risk factors

Gender disparity in terms of smoking and alcohol consumption was apparent (figure 2). Males were more than twice (aPR=2.38; CI 1.6 to 3.51) as likely as females to be the current smokers (table 4). Alcohol consumption prevalence in male was also 1.81(CI 1.29 to 2.53) times than that of female. The prevalence ratios of insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient physical activity by gender were very small (table 4). Males also had a higher probability of being overweight and obese than females, but the difference was not statistically significant (aPR=1.39; CI 1.0 to 1.93).

Figure 2.

Sociodemographic distribution of non-communicable disease risk factors.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis for NCD risk factors

| Variable | Smoking | Alcohol consumption | Insufficient fruit and vegetable intake | Insufficient physical activity | Overweight/obesity |

| aPR (CI) | aPR (CI) | aPR (CI) | aPR (CI) | aPR(CI) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | Reference | ||||

| Male | 2.38 (1.6 to 3.51)*** | 1.81 (1.29 to 2.53)** | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.03)* | 0.95 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.39 (1.0 to 1.93) |

| Age (in years) | |||||

| 13 | Reference | ||||

| 14 | 2.58 (1.25 to 5.3)* | 2.06 (0.99 to 4.25) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99)* | 1.03 (1.0 to 1.06) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.97)* |

| 15 | 2.58 (1.38 to 4.83)** | 1.91 (0.97 to 3.77) | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99)* | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 0.49 (0.3 to 0.81)** |

| 16 | 4.15 (2.1 to 8.21)*** | 2.56 (1.25 to 5.24)* | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.0) | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) | 0.64 (0.35 to 1.19) |

| 17 | 5.23 (1.97 to 13.88)** | 3.17 (1.35 to 7.48)* | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.99)* | 1.1 (1.02 to 1.18)* | 0.35 (0.13 to 0.96)* |

| Education (in grade) | |||||

| 7 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 8 | 0.72 (0.34 to 1.53) | 0.49 (0.241 to 0.99)* | 1.02 (1.0 to 1.04) | 0.93 (0.9 to 0.97)** | 0.49 (0.29 to 0.83)** |

| 9 | 0.56 (0.26 to 1.21) | 0.61 (0.27 to 1.37) | 1.03 (1.0 to 1.08) | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95)*** | 0.65 (0.4 to 1.05) |

| 10 | 0.524 (0.25 to 1.08) | 0.59 (0.23 to 1.53) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.74 to 0.87)*** | 0.47 (0.25 to 0.89)* |

| 11 | 0.38 (0.19 to 1.17) | 0.57 (0.14 to 2.46) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12)* | 0.79 (0.65 to 0.96)* | 1.48 (0.36 to 6.06) |

| Ecological region | |||||

| Mountain | Reference | ||||

| Hill | 1.39 (0.84 to 2.31) | 1.32 (0.81 to 2.15) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) | 1.22 (0.59 to 2.55) |

| Tarai | 0.94 (0.51 to 1.72) | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.65) | 1.0 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.0) | 0.69 (0.32 to 1.45) |

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; NCD, non-communicable disease.

With increasing age, the prevalence of smoking also tended to be high among the study participants (figure 2). The prevalence ratios of smoking of 14 years and 15 years to 13 years were 4.15 (CI 2.1 to 8.21) and 5.23 (CI 1.97 to 13.88), respectively. The prevalence of alcohol consumption for 16 years and 17 years were 2.56 (CI 1.25 to 5.24) and 3.17 (CI 1.35 to 7.48) times than that of 13 years. For insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient physical activity, the minimal difference across the age groups was observed (table 4). However, overweight and obesity had a tendency to decrease with growing age. The aPR for overweight/obesity in 17 years was 0.35 (CI 0.13 to 0.96).

After adjusting gender, age and ecological region, education did not have a significant association with smoking, alcohol consumption and insufficient fruit and vegetable intake (table 4). However, there was a gradual decrease in aPR of insufficient physical activity by grade: 0.93 (CI 0.89 to 0.97) in class 8, 0.86 (CI 0.77 to 0.95) in class 9, 0.8 (CI 0.74 to 0.87) in class 10 and 0.79 (CI 0.65 to 0.96) in class 11. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was also significantly less in class 8 (aPR=0.49; CI 0.29 to 0.83) and class 10 (aPR=0.47; CI 0.25 to 0.89) compared with class 7.

The distribution of prevalence of NCD risk factors across three ecological regions remained almost overlapped (figure 2). In the regression model, none of the risk factors had a statistically significant association with the ecological region (table 4).

Discussion

This study is based on the data from a nationally representative survey and assessed the prevalence, clustering and sociodemographic distribution of the NCD risk factors among adolescents in Nepal. The findings demonstrate the burden of NCD risk factors in Nepalese school children and highlight a disproportional distribution of the burden across gender, age and education. This is the first nationwide study to explore the NCD risk factors profile in this population; however, the findings are restricted to only five major NCD risk factors: smoking, alcohol consumption, insufficient fruit and vegetable intake, low physical activity and overweight/obesity.

The prevalence of current smoking was 6.04 (4.62–7.88) among the participants. This is considerably higher compared with that of 12–15 years children in other Southeast Asian countries such as India (1.1%) and Myanmar (1.7%).7 But, the rate is, by and large, consistent with the global status in current smoking, where most of the countries reported smoking prevalence between 4% and 11%, with an extremely low and high rate in Tajikistan (0.7%) and Samoa (32.2%).7 It is worth noting that the current prevalence is around two times higher than the national estimates measured among 13–15 years of age school children in 2001 (2.6%), 2007 (3.9%) and 2011 (3.1%).28 The huge gap between the current and the previous findings suggests that despite a significant decline in tobacco smoking across the globe,29 the prevalence of current smoking is still on the rise in adolescents in Nepal. The downward trend in smoking prevalence was associated with an effective implementation of tobacco-free initiatives.29 As expected, our study also found that young males were more likely to indulge in cigarette smoking than females. Likewise, age was a significant factor associated with smoking, the prevalence rose from 2.6% at 13 years to 10% at 17 years. However, this study did not find a noticeable difference in the prevalence of current smoking by education and geographical regions.

Similarly, this study found that 5% of the participants were current alcohol users. Southeast Asian countries, particularly Bangladesh (1.4%),30 Indonesia (2.5%), Maldives (4.9%) and Myanmar (0.9%) had a lower percentage of current alcohol users in adolescent age segment.8 But, the pooled prevalence of current alcohol users (25%) among adolescents in low and middle income countries is remarkably higher than the current study.8 No nationally representative study is available that can describe temporal trends in alcohol consumption in Nepal. However, evidence from outside Nepal indicates a recent decline in adolescent drinking globally.31 In line with the findings reported by a pooled analysis of GSHS data from 57 countries,8 the present study also demonstrated that the prevalence of current alcohol use was higher among boys than girls, and higher at later age (16–17 years) than earlier (13 years).

Regarding the recommended amount of fruit and vegetable consumption, the current and the previous studies revealed that insufficient intake is present in the almost entire population in Nepal irrespective of age, sex and other sociodemographic characteristics. Some of the previous studies reported its prevalence as 99% (nationwide),19 96.6% (rural),32 98% (peri-urban)33 and 97% (urban)19 based on different study settings in Nepal. Compared with our study findings, studies from other Southeast Asian Region countries such as India (85.1%), Indonesia (75.2%), Myanmar (83.3%), Sri Lanka (77.1%) and Thailand (67.1%) reported significantly lower prevalence of insufficient fruit and vegetable intake among school going children aged 13–15 years.34 The possible explanations for such widespread unhealthy dietary practice in Nepal could be the culturally diverse dietary behaviours, lack of awareness on potential benefits and limited access to fruit and vegetable,34 35 among others.

In the same way, low physical activity remained another concerning unhealthy practice among the study participants in Nepal. More than two-thirds of the participants (84%) were not as physically active as recommended. The finding is twice as high as the rate of the neighbouring country, Bangladesh (41.2%)30 and is also above the margin of global physical inactivity level in adolescents (80.3%).9 Hallal et al analysed data from 105 countries and concluded that 80.3% of 13–15 year-old children were doing fewer than 60 min of physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity per day.9 Our finding on low physical activity level was much higher than was that reported in the Nepalese adults (3%).19 However, it is important to note that the physical inactivity in adults is defined differently: not doing at least 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity throughout the week.24 Unlike the other studies,9 19 our study did not find a significant variation in insufficient physical activity rate between male and female. On the other hand, this survey showed that the prevalence of physical activity increased with increase in age or grade.

Our study recorded lower prevalence of obesity (0.6%) than the global age standardised rate (5.6%).36 A recent systematic analysis also showed Nepal had the lowest prevalence of overweight and obesity (4.6%) in <20 years boys among South Asian countries.37 Nonetheless, the current combined prevalence of overweight and obesity (7.0%) was significantly higher than that of the 2006 estimates (1.0%) in Nepal.38 As discussed by NCD Risk Factor Collaboration team,36 like other low and middle income countries, Nepal is still going through the nutrition transition, and yet to experience the escalating burden of overnutrition in adolescents. Therefore, it seems to be high time to concentrate behaviour change intervention for obesity prevention in school children in Nepal. Furthermore, as children with normal BMI in early age have a lower tendency to be overweight and obese by age 15 years and later, it is prudent to launch such behaviour change strategies in lower grade children.39 40

Co-occurrence of two and more afore-discussed NCD risk factors was highly prevalent in the study participants. More than two-thirds of the participants had at least two risk factors. The most frequent combination of risk factors was insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient physical activity. The risk factors clustering was high in males, among grade 7 students and in 17 years of age. Co-occurrence and clustering of risk factors among study participants signify the importance of designing an integrative intervention to tackle the multiple risk factors. Package of essential non-communicable disease interventions is an example of such cost-effective integrative approach for primary healthcare, which is being carried out as a pilot project in Nepal to deal with emerging burden of NCDs.41 But, there is a need for more adolescents specific, evidence-based community or school-based interventions focusing on primary prevention of NCDs in school children in Nepal.

This study has some limitations. Responses that require to report past events or experiences such as fruit and vegetable intake during past 30 days, physical activity during past 7 days, can sometimes lead to recall bias. The possibility of the under-reporting in terms smoking and alcohol use cannot be neglected in school settings because of social desirability bias. Similarly, as the participants were selected from school-going children, study findings should cautiously be generalised to out-of-school adolescents.

Conclusion

This study determines the extent of NCD risk factors burden among adolescents in Nepal. Findings suggest that NCD risk factors, particularly insufficient fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient physical activity are highly prevalent among the study population. This study shows that NCD risk factors are, individually or as a cluster disproportionally distributed across gender, age and grade, which indicates a need of age and gender specific, integrative health promotion strategies to forestall the impending NCD epidemic in Nepal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr Muhammad Islam, Biostatistical Analyst, Centre for Global Child Health for the support in plotting the equity graphs in Stata.

Footnotes

Contributors: RRD conceptualised the study, analysed the data, interpreted the findings and prepared the first draft. BB, ARP and MdC had an input in the conception and execution of the study and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The GSHS survey got ethical approval from the Ethical Review Board of Nepal Health Research Council.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: GSHS tools, data and reports are publicly available at WHO or CDC data repositories and can be accessed freely at https://nada.searo.who.int/index.php/catalog/29?fbclid=IwAR0KmcBc7ab4PtXhQba6AB3X0nJ_AHgp7aWwr6U53GJH904_NDQugTj0Di8 or https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/countries/seasian/index.htm. The data used in the study are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global health estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000-2016. Secondary Global health estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000-2016. 2018. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/

- 2. Di Cesare M, Khang YH, Asaria P, et al. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet 2013;381:585–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61851-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jan S, Laba TL, Essue BM, et al. Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2018;391:2047–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30323-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2014. Secondary Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2014. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128038/9789241507509_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 5. World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Secondary Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. 2018. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/2018/npl_en.pdf?ua=1

- 6. World Health Organization (WHO). Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xi B, Liang Y, Liu Y, et al. Tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in young adolescents aged 12–15 years: data from 68 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e795–e805. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30187-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ma C, Bovet P, Yang L, et al. Alcohol use among young adolescents in low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:415–29. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380:247–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang L, Bovet P, Ma C, et al. Prevalence of underweight and overweight among young adolescents aged 12-15 years in 58 low-income and middle-income countries. Pediatr Obes 2019;14 10.1111/ijpo.12468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patton GC, Viner RM, Linh leC, et al. Mapping a global agenda for adolescent health. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:427–32. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fleming TP, Watkins AJ, Velazquez MA, et al. Origins of lifetime health around the time of conception: causes and consequences. Lancet 2018;391:1842–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30312-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:743–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaukua J, Turpeinen A, Uusitupa M, et al. Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prognostic significance and tracking. Diabetes Obes Metab 2001;3:17–23. 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen G, McAlister FA, Walker RL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in framingham participants with diabetes: the importance of blood pressure. Hypertension 2011;57:891–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Safford MM, Brown TM, Muntner PM, et al. Association of race and sex with risk of incident acute coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2012;308:1768–74. 10.1001/jama.2012.14306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sliwa K, Acquah L, Gersh BJ, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and urbanization on risk factor profiles of cardiovascular disease in Africa. Circulation 2016;133:1199–208. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khanal MK, Mansur Ahmed MSA, Moniruzzaman M, et al. Prevalence and clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors in rural Nepalese population aged 40-80 years. BMC Public Health 2018;18:677 10.1186/s12889-018-5600-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aryal KK, Mehata S, Neupane S, et al. The burden and determinants of non communicable diseases risk factors in Nepal: findings from a nationwide STEPS Survey. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134834 10.1371/journal.pone.0134834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS). Secondary Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/

- 21. Aryal KK, Bista B, Khadka BB, et al. Global School Based Student Health Survey Nepal, 2015. Kathmandu: Nepal Health Research Council, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Indicator Definitions - Tobacco. Secondary Indicator Definitions - Tobacco, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/definitions/tobacco.html

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Indicator Definitions - Alcohol. Secondary Indicator Definitions - Alcohol, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/definitions/alcohol.html

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Physical Activity Basics. Secondary Physical Activity Basics, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/index.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcancer%2Fdcpc%2Fprevention%2Fpolicies_practices%2Fphysical_activity%2Fguidelines.htm

- 25. Hall JN, Moore S, Harper SB, et al. Global variability in fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:402–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:660–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data (GTSSData)- Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Nepal. Secondary Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data (GTSSData)- Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Nepal. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gtss/gtssdata/index.html

- 29. Islami F, Stoklosa M, Drope J, et al. Global and regional patterns of tobacco smoking and tobacco control policies. Eur Urol Focus 2015;1:3–16. 10.1016/j.euf.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World health Organization. Global School-based Student Health Survey-Bangladesh: 2014 Fact Sheet. Secondary Global School-based Student Health Survey-Bangladesh: 2014 Fact Sheet. 2014. https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/2014-Bangladesh-fact-sheet.pdf

- 31. Pennay A, Holmes J, Törrönen J, et al. Researching the decline in adolescent drinking: The need for a global and generational approach. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37(Suppl 1):S115–S119. 10.1111/dar.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dhungana RR, Devkota S, Khanal MK, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular health risk behaviors in a remote rural community of Sindhuli district, Nepal. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:92 10.1186/1471-2261-14-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dhungana RR, Thapa P, Devkota S, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors: A community-based cross-sectional study in a peri-urban community of Kathmandu, Nepal. Indian Heart J 2018;70:S20–S27. 10.1016/j.ihj.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Fruits and vegetables consumption and associated factors among in-school adolescents in five Southeast Asian countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:3575–87. 10.3390/ijerph9103575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sacks R, Yi SS, Nonas C. Increasing access to fruits and vegetables: perspectives from the New York City experience. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e29–e37. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 2017;390:2627–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2014;384:766–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart CP, Christian P, Wu LS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of elevated blood pressure, overweight, and dyslipidemia in adolescent and young adults in rural Nepal. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2013;11:319–28. 10.1089/met.2013.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tran MK, Krueger PM, McCormick E, et al. Body Mass Transitions Through Childhood and Early Adolescence: A Multistate Life Table Approach. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:643–9. 10.1093/aje/kwv233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Buscot MJ, Thomson RJ, Juonala M, et al. BMI trajectories associated with resolution of elevated youth BMI and incident adult obesity. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172003 10.1542/peds.2017-2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization (WHO). Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings. Secondary Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings, 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44260/9789241598996_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.