ABSTRACT

The Bacillus cereus group includes several Bacillus species with closely related phylogeny. The most well-studied members of the group, B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis, are known for their pathogenic potential. Here, we present the historical rationale for speciation and discuss shared and unique features of these bacteria. Aspects of cell morphology and physiology, and genome sequence similarity and gene synteny support close evolutionary relationships for these three species. For many strains, distinct differences in virulence factor synthesis provide facile means for species assignment. B. anthracis is the causative agent of anthrax. Some B. cereus strains are commonly recognized as food poisoning agents, but strains can also cause localized wound and eye infections as well as systemic disease. Certain B. thuringiensis strains are entomopathogens and have been commercialized for use as biopesticides, while some strains have been reported to cause infection in immunocompromised individuals. In this article we compare and contrast B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis, including ecology, cell structure and development, virulence attributes, gene regulation and genetic exchange systems, and experimental models of disease.

TAXONOMY: HISTORICAL AND SOCIOECONOMIC ASPECTS

The microorganisms constituting the Bacillus cereus group are Gram-positive low-GC-content bacteria belonging to the phylum Firmicutes. The group of spore-forming, aerobic, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria comprises at least eight closely related species: B. anthracis, B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, B. weihenstephanensis, B. cytotoxicus, and B. toyonensis (1). With the exception of B. cytotoxicus, which is the most divergent of the group, with a chromosome of 4.085 Mb (2), the genomes of the B. cereus group species are highly conserved, with sizes of 5.2- to 5.9-Mb and very similar 16S rRNA gene sequences.

The definition of these species and the distribution of the strains within them were based on phenotypes and their clinical and economic significance and mainly associated with plasmid content (3, 4). B. anthracis harbors two plasmids, pXO1 (182 kb) and pXO2 (95 kb), carrying the structural genes for the toxin proteins and the biosynthetic genes for capsule formation, respectively (5). The emetic B. cereus strains harbor plasmid pCER270, encoding enzymatic components required for the nonribosomal biosynthesis of the toxin cereulide (6, 7). B. thuringiensis harbors several plasmids encoding a large variety of the insecticidal toxins Cry and Cyt, which form the parasporal crystal characteristic of the species (8–10). The other five species are discriminated by morphological or physiological traits. B. mycoides and B. pseudomycoides have typical rhizoid growth (11, 12). B. weihenstephanensis strains are psychrotolerant. Like the mostly mesophilic members of the B. cereus group, the optimal growth temperature for B. weihenstephanensis is between 25 and 35°C, but the species is distinguished by its ability to grow at temperatures as low as 4°C (13). On the other hand, B. cytotoxicus strains are thermotolerant and can grow in up to 50°C (14). Finally, B. toyonensis was characterized for probiotic properties and is used as such in animal feed (15).

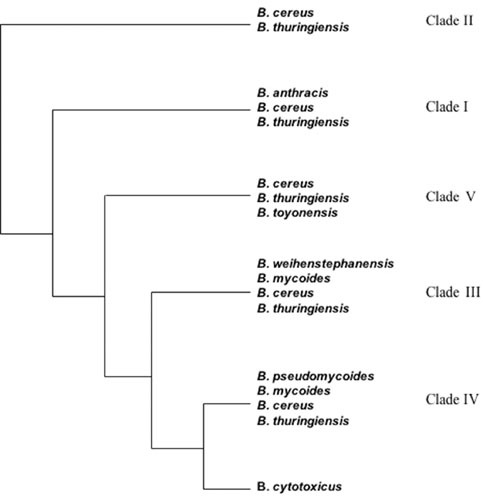

Speciation based on plasmid content and on morphologic or certain physiological features is confusing and can result in subjective conclusions. A recent genomic analysis of 224 strains shows that the B. cereus group can be divided into 5 major clades which do not match the 8 species described above (see Fig. 1). This lack of congruence between genomic-based phylogenetic analysis and specific phenotypes leads to the conclusion that plasmids carrying toxin genes such as the pXO plasmids of B. anthracis and the cry plasmids of B. thuringiensis cannot serve as signatures for species identification (1). As proposed by Helgason and colleagues (16) and by Rasko and coworkers (4), it is more useful to consider the B. cereus group a unique species comprising extremely diverse strains whose properties differ due to plasmid content or gene expression associated with key regulatory genes. For example, the global transcription regulator PlcR is active in B. cereus and B. thuringiensis but inactive in B. anthracis, abolishing the expression of a major regulon in that species (17, 18).

FIGURE 1.

The five major phylogenetic clades of the B. cereus group. Clade I is known as the B. anthracis clade but also includes emetic B. cereus and several clinical B. thuringiensis isolates. Clade II is known as the B. cereus/B. thuringiensis clade and includes most of the commercially used B thurigiensis as well as the B. cereus and B. thuringiensis type strains. Clade III is known as the B. weihenstephanensis clade and comprises most of the psychrotolerant isolates of the B. cereus group. Clade IV includes strains belonging to various B. cereus group species. These clades are based on multilocus sequence typing, amplified fragment length polymorphism, and whole-genome sequence data (429–431). The thermotolerant strains belonging to the species B. cytotoxicus cluster together in a separate group.

While it is arguably appropriate to refer to members of this highly related group of bacteria as B. cereus subsp. cereus, B. cereus subsps. anthracis, B. cereus subsp. thuringiensis, etc., in keeping with current practice, we will refer to the individual subspecies by their traditional names. We focus here on B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis because of the abundance of research related to their clinical and socioeconomic importance. We first present some unique and overlapping traits of these bacteria.

B. anthracis

B. anthracis, a major scourge of humanity, was first characterized by Koch and Pasteur as the etiologic agent of anthrax. Their investigations of this bacterium in the late 19th century represented early breakthroughs in microbiology and vaccination. Koch’s postulates, criteria designed to establish specific causal relationships between microbes and diseases, were based on studies of B. anthracis. In addition, an attenuated strain of B. anthracis served as the first live bacterial vaccine (19, 20).

Historically, strains harboring pXO1 and/or pXO2 were designated B. anthracis. However, recent reports of closely related species harboring similar plasmids indicate that speciation can be complex. B. cereus strains that harbor pXO1- and pXO2-like plasmids, named B. cereus bv. anthracis, have been isolated as the causative agents of anthrax-like infections in primates in Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire (21, 22). Similar B. cereus strains that produce the anthrax toxins were identified as the etiological agents of an anthrax-like cutaneous infection and anthrax-like respiratory infections in metalworkers (23–27). The well-studied B. cereus strain G9241, isolated from a welder with a severe anthrax-like respiratory illness, contains two virulence plasmids, pBCXO1 and pBC210 (also known as pBC218), as well as pBClin29, a linear plasmid that harbors cryptic prophage genes. The plasmid pBCXO1 has high similarity to pXO1 and contains the toxin genes pagA, lef, and cya, encoding toxin proteins with amino acid sequences of 96% or greater identity to their counterparts in B. anthracis (24). Plasmid pBC210 encodes a toxin protein paralogue, PA2, and the novel ADP-ribosyltransferase certhrax (24, 28–30). Each plasmid contains genes required for synthesis of a unique polysaccharide capsule; the enzymes needed for hyaluronic acid capsule production are encoded by the hasACB operon on pBCXO1, and the proteins required for elaboration of a putative tetrasaccharide capsule are encoded by the bps locus on pBC210 (24, 31). Interestingly, although B. cereus G9241 and B. anthracis Ames both produce capsule(s) and the anthrax toxin proteins, the virulence of G9241 in rabbits is more similar to that of B. anthracis Sterne strain 34F2 (pXO2–), which produces the toxins but not capsule (32).

B. cereus

B. cereus was first isolated from air in a cow shed and was characterized as a highly motile bacterium, generally appearing as single cells but occasionally forming longer threads and causing rapid liquefaction of gelatin (33). In the second half of the 20th century, B. cereus was recognized as a common food contaminant responsible for two types of poisonings. More recently, B. cereus has been increasingly recognized as an etiological agent of localized wound and eye infections as well as systemic infections (34, 35).

In the 1950s, Hauge showed that consumption of B. cereus-contaminated vanilla sauce could cause diarrhea (36). Since Hauges’ remarkable discovery, two protein toxin complexes (Nhe and Hbl) and a single-protein toxin (CytK) have been described, which are generally thought to contribute to the diarrheal type of food poisoning (37). More recently, several exoproteins with enzymatic activities, such as proteases or phospholipases, have been discussed as putative virulence factors contributing to the diarrheal syndrome (38, 39). Notably, these diarrhea-associated known and putative virulence factors are encoded by chromosome genes. In contrast, genes encoding the biosynthetic machinery for production of the depsipeptide toxin cereulide, which is the causative agent of the emetic type of B. cereus-mediated food poisoning, are on the 270-kb megaplasmid pCER270 (35). In contrast to the enterotoxin genes, which are broadly distributed among the members of the B. cereus group and show a high degree of molecular diversity (40), the cereulide synthetase gene is restricted to genetically closely related strains and shows rather low molecular diversity (41, 42). The ecological and evolutionary mechanisms driving the diversification processes of B. cereus virulence were hitherto poorly understood.

B. thuringiensis

B. thuringiensis was first isolated in 1901 in Japan from infected silkworm larvae (Bombyx mori). The bacterium was identified as the causal agent of the sotto disease (sudden-collapse disease), a lethal infection of this economically important insect (43). Subsequently, Berliner isolated the bacterium from the cadavers of flour moth larvae (Ephestia kuehniella) collected in a mill in Thuringia (44) and named it Bacillus thuringiensis, after the German province.

Based on its entomopathogenic properties, B. thuringiensis was rapidly commercialized and used as a biopesticide for pest control. The insecticidal activity spectrum of the bacterium was initially thought to be restricted to a few lepidopteran species. However, in 1977 discovery of the israelensis strain of B. thuringiensis, which is active against mosquitoes (45), accelerated a search for additional strains active against several species of insects and other invertebrates.

Today, a large number of strains have been shown to have activity against coleopteran insects or nematodes (46, 47). B. thuringiensis-based biopesticides account for approximately 75% of the global bioinsecticide market, representing about 4% of global insecticides (48). Several thousand B. thuringiensis strains have been shown to form crystalline Cry protein inclusions during sporulation, which in many cases are key to the insecticidal or nematicidal activity of the bacteria. However, not all B. thuringiensis isolates that produce Cry proteins have been found to be toxic. It is possible that some Cry proteins are inactive or have unidentified target hosts.

All the insecticidal toxin genes (cry, cyt, and vip) of B. thuringiensis are located on large plasmids (9, 49, 50). Generally, these plasmids are conjugative (51), and the cry genes are frequently found in the vicinity of various mobile genetic elements, such as the transposon Tn4430 and the insertion sequences IS231 and IS232 (8, 52, 53). The localization of the insecticidal toxin genes on elements associated with horizontal gene transfer is likely responsible for the great diversity of these genes and their multiplicity within the B. thuringiensis strains.

ECOLOGY: ENVIRONMENTS AND PATHOGENICITY

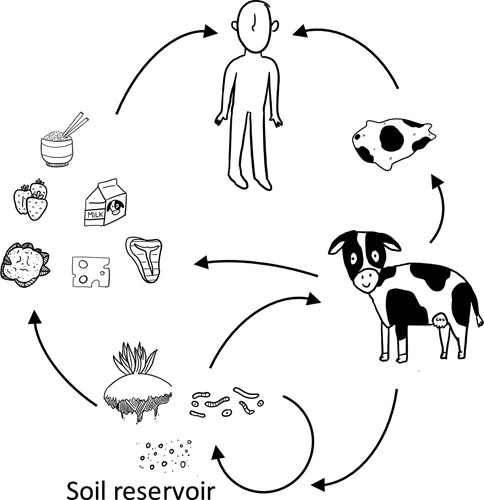

The B. cereus group species are endemic soil bacteria that occupy diverse ecological habitats as depicted in Fig. 2 (41, 54). Due to the formation of heat-, UV-, acid-, and desiccation-resistant endospores, the bacteria can persist in a dormant state, making it difficult to elucidate their primary ecological niches. In addition to soil, the species have been isolated from fresh and stored foods, invertebrates, and plants (55–60). Some reports suggest that the B. cereus group species do not germinate and grow in nonsterile soils unless a nutrient source, such as decomposing plants, insects, or animals is present (61–64). Reports of the isolation of B. cereus associated with plants may even point toward an endophytic lifestyle as an alternative niche for B. cereus (65, 66). Due to their ubiquitous presence, these organisms are hard to control and can enter food production and processing at various points (Fig. 2). Certain B. cereus strains have been reported to promote plant growth and to suppress plant diseases (67, 68). Recently, it was reported that the B. cereus AR156 strain induces systemic resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in Arabidopsis thaliana (69), suggesting that plant rhizospheres represent a natural niche for B. cereus.

FIGURE 2.

Transmission of the B. cereus group species from the soil reservoir to humans via food and textile production. Soil and soil-associated organisms including plants, insects, nematodes, and amoebae, serve as the major reservoirs for acquisition of spores. The bacteria are transferred to humans through agricultural products including food and animal-associated textiles, entering humans and other mammals through ingestion, inhalation, and breaks in the skin. Illustration credit: Olive E. Morrison.

Genome and physiology studies revealed that unlike true soil microorganisms, bacteria of the B. cereus group have few genes involved in the degradation of carbohydrate polymers. Conversely, these species contain a wide arsenal of genes encoding extracellular factors such as degradative enzymes (phospholipases, proteases, and chitinases), cytotoxic proteins (hemolysins, enterotoxins, and cytotoxins), and cell surface proteins (70, 71). These factors are potentially involved in the virulence and propagation of the bacteria in an animal host, thus conferring an obvious pathogenic lifestyle to the species (72). Outside of their hosts, the B. cereus group species are generally considered to reside as spores. Nevertheless, it is likely that the bacteria undergo some cycling of saprophytic growth, sporulation and germination in the soil. Epidemiological studies of clinical and nonclinical isolates suggest loss and horizontal movement of plasmids (22, 73–75).

The ecology of B. thuringiensis remains unclear despite multiple investigations (54, 76), and B. cereus ecology is even less explored (66). Studies of B. anthracis ecology have been fueled by the severity and worldwide occurrence of anthrax disease. B. anthracis can infect all mammals, some birds, and possibly even reptiles. The most severely affected parts of the world are central Asia and western areas of Africa. An “anthrax belt” exists from Turkey to Pakistan. In North America, anthrax is endemic in northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories. In the United States, sporadic outbreaks of anthrax occur in northwest Mississippi/southeast Arkansas and western Texas. The disease is also endemic throughout Mexico, Central America, and many South American countries. “Anthrax seasons” are characterized by hot dry weather which stresses animals and reduces their innate resistance to infection. Data from studies of central Asia support seasonal outbreaks, with the largest number of cases occurring in late summer (77, 78).

The prevalence of B. anthracis spores in the soil is affected by mean annual temperature, annual precipitation, elevation, amount of vegetation, soil moisture content, and soil pH (77, 78). Multiplication of B. anthracis outside of the host has been controversial. Concentrations of spores following disease outbreaks are thought to result from rains that pool spores in low-lying areas, as opposed to bacterial proliferation. Decomposition of infected animals at anthrax carcass sites leads to increased numbers of vegetative cells, but ultimately the numbers decrease as cells sporulate or die (79). Some studies suggest that B. anthracis competes poorly against indigenous bacteria; however, germination and amplification of anthrax spores by soil-dwelling amoebas and in the context of the plant rhizosphere have been reported (63, 80).

Humans and scavenging animals acquire gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax by ingesting spores in meat from infected animals, while wild and domestic herbivores ingest or inhale B. anthracis spores from the soil while grazing (81). Acquisition of spores from water appears to be less common (82). The infectious dose and severity of disease vary widely in different hosts. Domestic livestock, including sheep and cattle, and wild herbivores, such as bison, elephants, hippopotami, and kudu, are particularly susceptible to infection (83).

Inhalation anthrax in humans, also known as wool-sorter’s disease, was once common among textile workers who inhaled spores in dust generated from contaminated wool and animal hides. Today, most naturally acquired human cases of anthrax are cutaneous infections resulting from contact with dead infected animals or their products. Intentional dissemination of B. anthracis spores occurred in the United States in 2001. Eleven inhalation and eleven cutaneous cases of anthrax in humans were traced to four envelopes containing B. anthracis spores in powder form. The envelopes were sent to different locations via the U.S. Postal Service, and most of the patients were either mail-handlers or were exposed at worksites where contaminated letters were processed or received. Others are thought to have been exposed to cross-contaminated mail (84). This tragic event demonstrated the apparent ease with which the organism can be dispersed and solidified the placement of B. anthracis on the list of biothreat agents.

B. anthracis: the Anthrax Pathogen

Systemic anthrax, generally resulting from inhalation or ingestion of B. anthracis spores, has a high fatality rate. When B. anthracis spores are inhaled, alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells transport the organism to the proximal lymph nodes. Following spore germination, vegetative cells produce the antiphagocytic capsule and the anthrax toxin proteins, virulence factors which are critical for initiation of systemic disease (85, 86). In humans, bacteremia begins after an asymptomatic incubation period of 1 to 6 days. Following the onset of bacteremia, patients can experience flu-like symptoms for 1 to 5 days prior to an acute disease stage that lasts 1 to 2 days. Ultimately, death results from respiratory failure, sepsis, and shock (84, 87).

B. anthracis virulence is attributed primarily to production of anthrax toxin and capsule. The toxin structural genes and capsule biosynthesis genes are encoded by plasmids pXO1 and pXO2, respectively, and both plasmids are required for full virulence in immunocompetent hosts. The tripartite anthrax toxin, which comprises three secreted proteins—protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF), and lethal factor (LF)—has been the focus of investigations of anthrax disease. PA facilitates entry of EF and LF into host cells. EF is a calmodulin-dependent adenyl cyclase, and LF is a zinc protease. Together, the toxins disable the host’s innate and adaptive immune systems to induce lethal disease (88, 89).

The poly-γ-d-glutamic acid (PGA) capsule of B. anthracis, provides protection of the bacterium from phagocytosis, as is true for many bacterial capsules which are more commonly made of polysaccharide. High concentrations of capsule released from B. anthracis cells during infection are important also for host-pathogen interactions (90–93). The PGA capsule has been shown to augment lethal toxin-mediated cytotoxicity and induce production of inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide, which likely contribute to systemic inflammation and sepsis at the terminal stage of infection (94–97).

In addition to toxin and capsule, other secreted and nonsecreted factors have been reported to affect host-pathogen interactions and affect host pathology (98, 99). Among these are extracellular proteases that interfere with the immune response by cleaving antimicrobial peptides (100). The proteases NprB/Npr599 (also designated NprA in B. thuringiensis and B. cereus) and InhA1 can degrade host tissues, resulting in increasing barrier permeability (101–103). Crossing of the brain barrier is considered to be key to the extensive brain pathology that has been reported for human disease (104).

B. cereus and Gastrointestinal Disease

B. cereus pathogenicity is based on a panoply of virulence factors, which are far from understood, contributing to a range of human disease. B. cereus can cause two types of food poisoning, which are primarily characterized by diarrhea and emesis (37, 105, 106). The diarrheal syndrome has been linked to different enterotoxins thought to be produced after outgrowth of spores, taken up with contaminated foods, and active in the small intestine. The emetic syndrome is the result of an intoxication caused by the single depsipeptide toxin cereulide, which is preformed in food. The genes encoding the cereulide synthetase toxin genes are primarily found in a distinct subgroup of B. cereus, while the enterotoxin genes are broadly distributed among the members of the B. cereus group (41, 107). Usually, these GI-related diseases are self-limiting, but more severe forms require hospitalization, and occasionally fatalities have been reported (58, 108, 109). Intoxication related to cereulide has been linked to severe clinical manifestation, such as acute liver failures and acute encephalopathy (110). Due to the high biological activity of the cereulide toxin, occasionally liver transplantation is necessary as a life saving measure (111, 112). Generally, the pathogenic potential of B. cereus strains is highly variable and ranges from strains that show no cytotoxic activity in cell culture assays to strains that are highly cytotoxic (113, 114). In addition to intrinsic strain-associated differences in pathogenic potential, virulence is affected by environmental factors (58, 115, 116).

Apart from its food poisoning potential, B. cereus is increasingly recognized as an opportunistic pathogen that can cause local as well as systemic infections. Immunocompromised people and neonates are at special risk for hospital-acquired B. cereus infections, such as infections of the central nervous system, endocarditis, respiratory and urinary tract infections, wound infections, and septicemia (34). Outside of hospital-acquired infections, B. cereus has been linked to eye infections, such as endophthalmitis and keratitis (117). Furthermore, B. cereus can cause severe mammary gland infections in ruminants (118, 119). The virulence factors contributing to infections in ruminants and to most non-GI-related human infections are unknown.

B. thuringiensis Infection of Invertebrates

In addition to virulence genes common to the B. cereus group and to specific insecticidal toxin genes, the B. thuringiensis genome contains several genes encoding chitinases, suggesting a close relationship between this bacterium and the insects. Many well-studied B. thuringiensis strains were isolated from insects (44–46), and large screens of natural environments have shown that insects were more fruitful sources of the bacterium than soil samples (120). About 40% of the invertebrates tested were found to harbor B. thuringiensis spores. While insects appear to be the preferred target of B. thuringiensis, the bacterium can propagate in other invertebrates (121, 122). Nematode-B. thuringiensis association is highly probable in soil and other natural environments, and several B. thuringiensis strains harbor cry genes that are specifically active against nematodes (123). When nutrients are available, B. thuringiensis might be a multihost pathogen (124) with two pathogenic lifestyles: one resulting from its specific toxins (Cry or Vip) encoded by plasmid genes and targeting insects, nematodes, and other invertebrates (49, 125) and one nonspecific, depending on various chromosomal factors providing opportunistic properties. These nonspecific factors may allow the bacteria to propagate and eventually to kill various organisms if they are weakened by any cause, for example, by Cry toxins in the case of insects (126). This second pathogenic lifestyle may be shared with B. cereus, which possesses the same chromosome-encoded virulence factors (70). In this point of view, the Cry toxins of B. thuringiensis are “public goods” which can act cooperatively and thus profit cheater bacteria such as B. cereus (127).

The genome of B. thuringiensis contains a 41-gene regulon devoted to its saprophytic or necrotrophic lifestyle (128). This regulon, which includes genes encoding various degradative enzymes, is activated by the quorum sensing regulator NprR and allows B. thuringiensis to survive in the insect cadaver. The NprR regulon is also transcribed in all other B. cereus group species, suggesting that the bacteria of this group have similar saprophytic properties (129). Altogether, these pathogenic and saprophytic functions are highly efficient adaptive traits that allow the species to grow and survive in various natural conditions and niches.

CELL STRUCTURE AND DEVELOPMENT

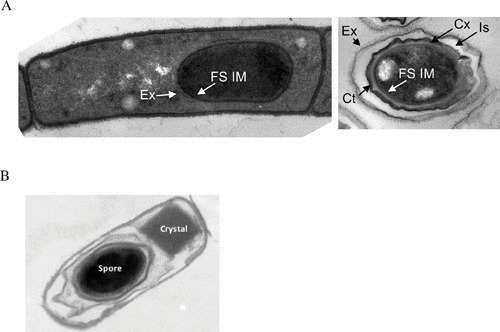

Vegetative cell and spore structures do not vary greatly among the B. cereus group species. Generally, vegetative cells appear in chains, with the square ends of the cells fitting closely together. Variations in chain length occur as a normal aspect of growth in different media and environments (34, 130). Interestingly, B. anthracis vegetative cell chains in infected tissues are generally shorter than those formed during growth in vitro. Chaining of B. anthracis cells impedes invasion of host cells and is associated with escape from phagocytic clearance (131). Spores of the three species also have similar morphology. Spore size and morphology can vary between strains of the same species, but most strains produce spores with diameters of approximately 1 μm that are surrounded by a loose-fitting outer layer termed the exosporium (Fig. 3). Fine features of spores can be altered in different growth and sporulation conditions.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Thin-section transmission electron micrograph of B. anthracis cell after 5 hours of sporulation (left image) and a mature spore (right image). The forespore inner membrane (FS IM) and nascent exosporium (Ex) (left image), and forespore inner membrane (FS IM), mature exosporium (Ex), coat (Ct), interspace, (Is), and cortex (Cx) (right image) are labeled. (B) B. thuringiensis sporulating cell with parasporal crystal. Cells were sporulated, prepared, and imaged as described in reference 432. Image credit: (A) Tyler Boone and Adam Driks. (B) Fuping Song.

Vegetative Cell Envelope

The surface of B. anthracis, including secondary cell wall polysaccharides (SCWPs), the surface layer (S-layer), and capsule, has been the most well studied of the B. cereus group species. The B. anthracis SCWP comprises trisaccharide repeats [→4(-β-ManNAc-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→6)-α-GlcNAc-)1→] with α-Gal and β-Gal substitutions tethered to the peptidoglycan by acid-labile phosphodiester bonds. SCWP is essential for cell growth, shape, and division. Although the enzymes for SCWP synthesis have not been fully characterized, two proteins, WpaA and WpaB, have been proposed as glycosyltransferases that act to assemble the SCWP polymers prior to attachment to the peptidoglycan. The B. anthracis SCWP is critical for maintenance of cell shape and for full virulence. Depletion of the glycosyltransferases results in irregularly shaped, nonviable cells (132). In addition, a mutant lacking a UDP-glucose 4-epimerase required for SCWP galactosylation exhibited reduced encapsulation and decreased virulence in a murine model of anthrax (133). Recent investigations of B. cereus isolates causing anthrax-like disease indicate SCWP with a structure similar to that of B. anthracis but with an additional α-Gal substitution at O3 of N-acetylmannosamine (134).

In B. anthracis and some pathogenic B. cereus strains, S-layer proteins have been shown to attach to the cell wall via noncovalent interactions with SCWPs (135). The S-layers are paracrystalline arrays of protein that serve as protective barriers and as scaffolds for housekeeping enzymes and virulence factors (136). Major S-layer proteins of B. anthracis are Sap (for surface associated protein) and EA1 (for extractable antigen 1). Fully assembled and acetylated SCWP is important for assembly of some S-layer proteins. Mutants deleted for putative acetyltransferases are unable to deposit the S-layer-associated murein hydrolase BslO at cell division septa and have altered chain lengths (137).

Finally, a key distinguishing feature of B. anthracis is its capsule. The B. anthracis capsule comprises PGA. As is true for typical polysaccharide capsules, the B. anthracis capsule protects cells from phagocytosis during infection. In addition, the B. anthracis capsule renders the bacterium somewhat resistant to mammalian proteases and is a poor immunogen (138, 139). An immunoassay for PGA using monoclonal antibodies has revealed that PGA is shed into the blood during infection of mice and nonhuman primates (91, 140, 141), likely due to the activity of a capsule depolymerizing enzyme, CapD, that is coexpressed with the capsule biosynthesis operon. The capsule degradation products are thought to inhibit the innate immune response through targeting of cytokine pathways (142).

The PGA capsule is also produced by some but not all B. cereus isolates that cause anthrax-like disease. These strains harbor plasmids that allow strain-specific differences in synthesis of the PGA capsule, a hyaluronic acid capsule, and a tetrasaccharide capsule. The results of virulence studies to assess the role(s) of the B. cereus capsules are somewhat contradictory and incomplete (22, 24, 31, 75). Further investigations are needed to determine the specific functions of these capsules.

Spore Architecture

The architecture of the B. cereus group species spore is comparable to the spores of other Bacillus species. The innermost compartment of the spore contains the DNA. The DNA is housed with cations and pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid in a 1:1 chelate with divalent calcium ions, which serve to maintain the spore’s dormant state and resistance to DNA-damaging agents. Germinant receptors in the inner membrane initiate the signal transduction pathway that leads to outgrowth of the spore and the vegetative cell state (143). Germinants of the B. cereus group species can be a subset of sugars, amino acids, and ribonucleosides, as well as other small molecules, depending on the species and strain (144). A shell of peptidoglycan containing two sublayers, the cortex and the germ cell wall, surrounds the inner membrane. The cortex constricts the core’s volume to retain the relatively dry state of the core. At outgrowth of the spore, the germ cell wall becomes the nascent cell wall of the vegetative cell. Surrounding the cortex is the spore coat, which contains approximately 70 proteins arranged in layers to form a somewhat flexible structure (143).

The exosporium, an additional layer surrounding the spore coat of some Bacillus species that has been most well studied in B. cereus and B. anthracis (145), can respond to changes in spore hydration. The exosporium comprises a crystalline basal layer overlaid by a “hairy nap.” The composition and assembly process of the exosporium are poorly understood. BclA and related proteins form the hairy nap. Among the approximately 20 proteins of the basal layer is ExsY, which can self-assemble into structures resembling the intact basal layer and thus appears to be a key player in exosporium formation (146). The exosporium excludes large molecules. It also provides resistance to specific chemicals in vitro and to nitric oxide in the context of the macrophage (147–149). Removal of the exosporium from B. anthracis spores does not impede virulence in several animal models (150–152). However, the exosporium protein BclA binds macrophage receptors to mediate interactions with epithelial cells and extracellular matrix proteins (153, 154), suggesting a role for the exosporium in pathogenesis (145).

Germination Dynamics and Signals

The overall process of germination, in which spores transition to metabolically active vegetative cells, is highly conserved in the Bacillus genus, but the specific signals and associated receptors vary among species. B. anthracis germinates in response to alanine or purine ribonucleotides, with one or more additional amino acids acting as cogerminants (155–157). Many germinant receptors have been described in the inner membrane of Bacillus species. Notably, a unique set of germination genes, the gerX operon, is located on pXO1 of B. anthracis. Mutants missing the operon are altered for germination in vivo (158, 159). Once Bacillus spores germinate, spore cortex lytic enzymes degrade the cortex peptidoglycan, allowing core rehydration and cell outgrowth (160). B. anthracis differs from other species examined in that it contains an additional spore coat lytic enzyme which appears to work synergistically with the common enzymes (161).

Germination in the Host

Multiple routes of infection with B. anthracis spores lead to disease, suggesting that germination can be triggered by signals in different host niches. Studies of B. anthracis germination in vivo have yielded intriguing results. Inhalation anthrax models have shown that phagocytes and dendritic cells phagocytose spores and transport the bacteria to the lymph nodes (162, 163). Spores and vegetative cells appear in phagocytic cells, but it is unclear whether spores germinate before or after phagocytosis. Moreover, some strains germinate quickly in the lung, while others remain ungerminated for days (164, 165), suggesting that germinants plus additional unknown factors influence development in vivo. Finally, germination occurs in cell-free macrophage-conditioned media, indicating that phagocytes are not required for B. anthracis spore germination (157).

Studies of B. thuringiensis germination include experiments simulating conditions encountered in the insect midgut. The pH of the lepidopteran midgut is 10, and pretreatment of B. thuringiensis spores with larval midgut fluid or with an alkaline buffer stimulates germination (166, 167). This alkaline activation of spores requires plasmid-encoded germination genes (168). Cry proteins associated with the spore surface allow B. thuringiensis spores to bind brush border membrane vesicles prepared from lepidopteran insects, and the binding has been proposed to be responsible for stimulation of alkali-activated germination (169). It should be noted however, that the spore surface-Cry protein association may simply result from concomitant synthesis rather than from a specific interaction. Finally, germination of B. thuringiensis spores in the intestines of nematodes has also been reported (122).

Sporulation

The sporulation signal cascade has been well studied in Bacillus subtilis, and the pathways and regulators of sporulation in the B. cereus group species appear to be similar to those of B. subtilis. Nevertheless, variations among species have evolved with specific niches. B. anthracis does not sporulate during infection. In the wild, spores (which are the infectious form of the bacterium) only form when the blood of an infected carcass is exposed to the environment (78). The lack of sporulation in the mammalian host appears to result from a specific configuration of the phosphorylation cascade in this species (170–172). In contrast, it has been shown that part of the B. thuringiensis population sporulates during infection in insect larvae, and this process is under the control of the bifunctional regulator NprR (173, 174). The Rap phosphatases negatively control sporulation by stimulating a component of the phosphorelay involved in the phosphorylation of Spo0A, the master regulator of sporulation initiation (175). Rap activity is controlled by the Phr signaling peptides through a quorum sensing system. In B. anthracis and B. thuringiensis, plasmids harbor rap-phr genes involved in sporulation (176). These plasmid-borne Rap-Phr systems may provide advantages for adaptation of these pathogenic bacteria to their respective ecological niches.

TOXINS

Toxins, the first bacterial virulence factors to be described (177), represent the major drivers of pathogenicity within the B. cereus group. A variety of chromosome- and plasmid-encoded toxins, some shared among the species and some species specific, have been described. Table 1 shows an overview on the most important B. cereus group exotoxins. The species-specific toxins, namely, the B. anthracis tripartite anthrax toxin complex and the B. thuringiensis insecticidal Cry toxins, as well as the depsipeptide toxin cereulide of the emetic type of B. cereus, are encoded on plasmids, while many other B. cereus group toxins are encoded by the chromosome. Some B. anthracis and B. cereus isolates harbor duplicated and/or closely related toxin genes (35, 178), and B. thuringiensis strains can harbor several cry genes.

TABLE 1.

Exotoxins, the major virulence factors of the B. cereus group

| Toxin | Toxin type | B. anthracis | B. cereus | B. thuringiensis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthrax toxin (PA, LF, EF) | AB toxin | + | +a | – |

| Emetic toxin (cereulide) | Heat-stable depsipeptide toxin | – | + | – |

| Enterotoxins (Nhe, Hbl, CytK) | Pore-forming toxins | –b | + | + |

| Insecticidal toxins (Cry, Cyt, Vip, Sip) | Pore-forming toxins | – | – | + |

Some rare strains.

nhe genes are present but inactive.

B. anthracis Toxins

Anthrax toxin has been a major focus of anthrax research since the initial discovery of the toxigenic potential of B. anthracis culture supernates. B. anthracis secretes three proteins, PA, LF, and EF, known collectively as anthrax toxin. Purified toxin proteins in binary combinations have distinct effects when injected into experimental animals. Lethal toxin (LeTx), a mixture of LF and PA, causes death, while edema toxin (EdTx), a mixture of EF and PA, produces edema. PA (83 kD) mediates binding and translocation of the enzymatic proteins LF (90 kD) and EF (89 kD) into host cells.

PA is a nonenzymatic but critical component of LeTx and EdTX because it mediates toxin binding to host cells and facilitates translocation of LF and EF into cells. PA binds to one of two related proteins, capillary morphogenesis protein 2 (CMG2 or ANTRX2) and tumor endothelial marker 8 (TEM8 or ANTRX1), which are found on cells of many different tissues. CMG-2 is the most important for pathogenesis, while TEM-8 has a minor role (179, 180). In the model of anthrax toxin entry, furin and possibly additional host-associated proteases cleave PA into two fragments, PA63 (63 kDa) and PA20 (20 kDa) (89). The receptor-bound carboxyterminal 63-kDa fragment (PA63) oligomerizes to form a ring-shaped structure comprising seven or eight PA63 molecules. One to three molecules of LF and/or EF bind to the PA ring, and the complex is endocytosed by clathrin-coated vesicles. Endosome acidification induces a conformational change in the ring such that it converts from a “prepore” to a pore (channel) in the membrane, facilitating translocation of EF and LF across the membrane (181).

LF, a zinc-dependent metalloproteinase, is the central effector of shock and death from systemic anthrax. Initial investigations of LF activity revealed that the protein cleaves mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases, resulting in disruption of multiple signaling pathways and causing broad downstream effects on cell physiology (182). More recent reports show that low levels of LeTx inhibit the glucocorticoid receptor, an important component of host defense against inflammation. LF targets the inflammasome sensor NLRP1, causing activation of the caspase-1-dependent cell death signaling pathway (183). Finally, murine susceptibility to lethal toxin has been associated with genetic polymorphisms in the Ltx gene on mouse chromosome 11. The Ltx gene encodes a kinesin-like motor protein, Kif1C, but the relationship between lethal toxin and Kif1C is not clear (184).

EF is a calmodulin-dependent, Ca+2-dependent adenylyl cyclase (185). As is true for other bacterial toxins that elevate cAMP levels, disruption of normal second-messenger signaling has many effects on host cell physiology. EdTx weakens antibacterial responses of phagocytes, impairing apoptosis, motility, and release of inflammatory cytokines. Human neutrophils treated with the toxin have reduced phagocytic and oxidative burst abilities (186).

A comprehensive model of the molecular basis of anthrax toxin effects on mammalian hosts is still evolving, but a wealth of current information reveals that together, the toxin components severely impinge on the immune functions of susceptible hosts, which are key to the outcome of B. anthracis infection (89, 187, 188).

Anthrolysin O is a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin with properties similar to the pore-forming toxins of other Gram-positive pathogens (189). Initially discovered as a hemolysin (190), ALO has lytic activity against phagocytes (191), decreases the barrier function of human polarized epithelial cells (192), and appears to play a role in gut epithelial disruption during B. anthracis infection (193). Expression of the alo gene is highly responsive to in vitro growth conditions (190). During infection, alo transcripts are present in newly germinated bacteria after phagocytosis of the spores by mouse macrophages (194, 195). Concurrent deletion of alo and phospholipase genes attenuates virulence and reduces growth and survival in phagocytes, suggesting a role for the toxin in destabilization of the phagocytic membrane (196).

B. cereus Toxins

Various B. cereus exotoxins have been associated with pathogenicity, but the actual contribution and importance of these toxins for GI and non-GI related diseases is largely unknown. So far, four B. cereus exotoxins have been clearly linked to food poisoning. Three pore-forming enterotoxins (Nhe, a three-component nonhemolytic enterototoxin, Hbl, a three-component hemolytic enterotoxin, and the single protein cytotoxin CytK) are thought to provoke diarrhea after toxicoinfections with B. cereus spore-contaminated food (37). Hbl enterotoxic activity has been demonstrated in vivo on rabbit intestine (197), but direct in vivo proof for Nhe and CytK activity is lacking. Nhe was identified from a strain isolated from a foodborne outbreak in Norway (198), and CytK was originally isolated from a B. cereus strain that was responsible for a severe foodborne outbreak in which several people developed bloody diarrhea and three elderly people died (199). Enterotoxins may act synergistically with each other and with other virulence factors, making it difficult to predict the overall enterotoxic potential of a given strain (39, 106, 200–204). Nhe, Hbl, and CytK show cytotoxic activity on Vero and Caco2 cells as well as on other human cells. Different cell lines show distinct susceptibilities to the different toxins (205), suggesting different modes of toxin action.

Typically, symptoms occur after 6 to 12 hours and are self-limiting. However, in rare cases the severity of symptoms requires hospitalization, and fatalities among neonates and immunocompromised patients have been reported (108, 109, 199).

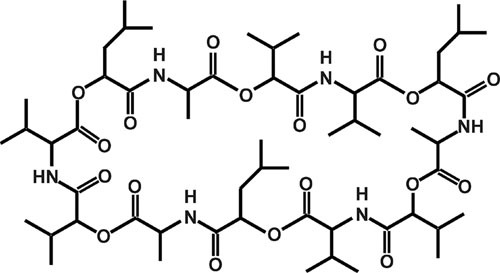

The fourth toxin, the so-called cereulide, is linked to the emetic type of B. cereus food poisoning (206). Cereulide is a depsipeptide toxin, composed of alternating α-amino and α-hydroxy acids (d-O-Leu–d-Ala–l-O-Val–l-Val)3 (Fig. 4), that is structurally related to the potassium ionophore valinomycin (206). It is produced by the cereulide peptide synthetase Ces (6, 42, 207, 208), which represents a novel type of nonribosomal peptide synthetase (6, 207–209). Cereulide is usually preformed in food, and the onset of symptoms occurs between 15 minutes and 6 hours after uptake of contaminated food (105). In the past, quantification of cereulide has been hampered by the lack of appropriate methods (58). The recently developed ISO method (EN ISO 18465), based on a stable isotope mass spectrometry-based dilution assay (210), will allow accurate cereulide quantitation in the future. Recently, 18 cereulide isoforms were described, with cytotoxic potential ranging from nontoxic to 10-fold more toxic than the classic cereulide (211). Cereulide is not inactivated during stomach passage in the host because it is resistant to cleavage by pepsin and trypsin (105, 212). Due to its hepatotoxic activity, cereulide can cause rhabdomyolysis, liver damage, and severe multiorgan failure (110, 112). Recently, cereulide was linked to the induction of diabetes by causing beta cell dysfunctions (213).

FIGURE 4.

Cereulide, the emetic toxin of B. cereus.

B. thuringiensis Toxins

Except for the cereulide toxin, B. thuringiensis strains generally produce the same toxins as B. cereus (214). The phenotype distinguishing B. thuringiensis from the other species of the B. cereus group is the production of a crystal inclusion during sporulation (Fig. 3). This crystal generally appears beside the spore in the mother cell compartment of the bacteria (215), but other situations have been reported in a few strains, including a crystal between the exosporium and the spore coat (216), and production of spores and crystals in two distinct subpopulations of bacterial cells (217). The crystal inclusion can account for up to 25% of the dry weight of B. thuringiensis cells, which means that a massive production of proteins should occur during sporulation or stationary phase. This massive protein production results from several mechanisms, including efficient transcription regulation, an exceptionally high stability of cry gene mRNA, and the crystallization of the proteins (218). In most of the B. thuringiensis strains the expression of the cry genes depends on sporulation-specific sigma factors, Sigma E and Sigma K, which are functional in the mother cell compartment during a long period of the sporulation process. Some exceptions have been observed. For example, the cry3 genes encoding coleopteran-active toxins are expressed during stationary phase independently of the sporulation sigma factors (218).

The crystal inclusions are composed mainly of two types of proteins, the Cry and the Cyt proteins, also called δ-endotoxins (49, 219). Various combinations of toxins can be found on the crystal, depending on the B. thuringiensis strain. The commercial strain kurstaki HD1 Dipel® contains five cry genes (cry1Aa, cry1Ab, cry1Ac, cry2Aa, and cry2Ab), all encoding proteins active against lepidopteran larvae (220). The strain israelensis contains four cry genes (cry4Aa, cry4Ba, cry10Aa, cry11Aa) and two cyt genes (cyt1Aa and cyt2Ba), all encoding proteins toxic for the mosquito larvae (9). The Cry proteins are distributed into 75 distinct classes, with less than 45% identity between them (http://www.lifesci.sussex.ac.uk/home/Neil_Crickmore/Bt/). They are pore-forming proteins whose activity requires the binding to specific receptors on the surface of midgut cells (194). The Cyt toxins are cytotoxins specifically active against dipteran larvae (199); they also have a synergistic action by serving as receptors for dipteran-active Cry proteins (221).

In addition to the Cry proteins forming parasporal inclusions, some B. thuringiensis strains secrete insecticidal proteins: the Sip (secreted insecticidal protein) and Vip (vegetative insecticidal protein) proteins. Sip1A is active against coleopteran insects and was isolated from a B. thuringiensis strain harboring a coleopteran-specific cry3 gene (207). The toxin Vip3A is specifically toxic against lepidopteran insects and is generally produced by strains that also produce Cry1A lepidopteran-active toxins (209). The insecticidal activity of the exported proteins Vip and Sip and their association with Cry proteins showing related activity spectra suggest that the larvicidal activity of the Cry proteins is reinforced by the secretion of Sip and Vip proteins, thus increasing the entomopathogenicity of the B. thuringiensis cells multiplying in the infected insect larvae.

Common Secreted Enzymes of the B. cereus Group Species

Phospholipases, sphingomyelinases, hemolysins, proteinases, and peptidases likely represent additional virulence factors of the B. cereus group species (39, 106, 202–204). In a murine model of anthrax, protease inhibitors enhance the positive effect of antibiotics, suggesting that one or more proteases contribute to anthrax disease (222).

Immune inhibitor A (InhA1) is a particularly well-studied protease that has homologues in all three species. B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis each carry multiple apparent inhA genes, with transcription of each gene being subject to different regulation (223, 224). Autolytically processed active InhA1 of B. anthracis cleaves multiple host proteins and other proteins in the B. anthracis secretome (225, 226). A B. anthracis inhA1-null mutant is attenuated in a murine model of anthrax (227). The reduced virulence of the mutant likely results from its broad activity on multiple targets, ultimately facilitating bacterial dissemination. InhA1 disturbs the host coagulation machinery by cleaving von Willebrand factor and its regulator ADAMTS13 (102). The enzyme also cleaves zonula occluden-1, resulting in disruption of the blood-brain barrier (103). Degradation of hemoglobin by InhA in the bloodstream has been proposed to allow B. anthracis access to essential amino acids required for proliferation in the blood (227). In B. cereus and B. thuringiensis, deletion of the three inhA genes strongly affects virulence (202). InhA1 is required for efficient escape from macrophages (228).

MODELLING HOST INTERACTIONS

Animal Models of Anthrax

Multiple animal models differing in host species, bacterial strain, and delivery route are used to investigate B. anthracis-host interactions. The significant variability among laboratory animals in susceptibility to B. anthracis infection makes modeling human anthrax particularly challenging. Nonhuman primates are considered superior models for studies of potential therapeutics and vaccines, but the high cost and ethical considerations limit their use. Rabbits serve as good models because the disease pathology is similar to that observed in nonhuman primate and clinical human cases of anthrax. Mice and guinea pig models are used frequently because of experimental ease and moderate cost. For most animal studies, the spore form of the bacterium is used as the infectious agent, modeling natural infection. Methods for pulmonary delivery of spores include intranasal inoculation, aerosol exposure, and tracheal injection. Spores can also be introduced subcutaneously. To model late-stage disease, vegetative cells are inoculated directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the requirement for in vivo germination of spores (229).

Mice are the most common experimental animal for investigations of B. anthracis. Inbred mice infected via the parenteral and pulmonary routes develop acute disease, with vegetative cells in multiple tissues. Immunodeficient (C5–) mouse strains such as A/J and DBA/2J are susceptible to relatively low doses (103 to 104 CFU) of capsule-deficient (pXO1+pXO2–) Sterne-type strains and are used often for studies of the roles of anthrax toxin in vivo and for testing the efficacy of toxin-based therapeutics and vaccines. Exposure of C5– mice to aerosolized Sterne spores results in pathology similar to that observed in rabbit and nonhuman primate models, with lethal toxin required for dissemination and development of protective immunity (230).

Studies of pathogenesis and host responses related to nontoxin factors have been commonly assessed in infections of immunocompetent mice with nontoxigenic (pXO1–pXO2+) strains. Interestingly, guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates are not susceptible to infection by pXO1–pXO2+ strains (231). It is also notable that mice are not protected from fully virulent (pXO1+ pXO2+) strains by the PA-based vaccine AVA, whereas AVA is fully protective for rabbits and nonhuman primates but only partially protective for guinea pigs (232, 233).

Mouse models have revealed interesting aspects of germination and dissemination of B. anthracis during infection (229). Carr and coworkers (234) demonstrated functional redundancy among the five known germinant receptors, and McKevitt and coworkers (159) showed that the germination inhibitor d-alanine reduced the infectious dose of spores, suggesting that timing of germination is important for disease. Experiments conducted by Glomski and colleagues (235, 236) using luminescent recombinant strains showed that germination and dissemination from pulmonary, skin, and GI entry points does not require transport to lymph nodes, but spore dose and method of delivery can affect the timing and location of germination. Their data also revealed a role for capsule in dissemination.

Inbred mice have also been used extensively to explore the host response to B. anthracis infections. Investigations of host systems important for recognition of bacterial factors and activation of immunity have revealed a model in which B. anthracis activates Toll-like receptors and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) inflammasome, resulting in tumor necrosis factor alpha production by a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. LeTx suppresses this response by cleaving mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases. EdTx-mediated increases in cAMP also disrupt cell signaling pathways. In the battle between host and pathogen, the immunosuppressive effects of LeTx are countered by Nlrp1b, the product of a “lethal toxin sensitivity” locus on chromosome 11. In response to lethal toxin, the lethal toxin-sensitive Nlrp1b allele activates caspase-1, inducing proinflammatory cytokines that recruit neutrophils and mononuclear cells. Thus, in mice, LeTx-mediated Nlrp1b-dependent activation of caspase-1 is a major factor in the control of B. anthracis infection (229).

Guinea pigs are keenly susceptible to B. anthracis spore infection but not very sensitive to the anthrax toxins. While other animal models show some inconsistencies in terminal loads of bacteria, intramuscular challenge of guinea pigs with a fully virulent (pXO1+ pXO2+) strain leads to specially and temporally consistent infections. Aerosol infection of guinea pigs results in edema and hemorrhage in the spleen, lungs, and lymph nodes, facilitating studies of pathology. Guinea pigs have been used in competitive infection studies employing different strains and mutants. These experiments have revealed roles for biosynthetic genes and surface proteins in disease (229).

Rabbits have been useful to determine virulence differences in B. anthracis strains and mutants and to examine pathology, which is similar to that observed in humans and nonhuman primates. Multiple investigations of vaccines and therapeutics have employed rabbit models. Rabbits exhibit a strong immune response to PA and have played a key role in the development of correlates of immunity. A quantitative anti-PA IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and a toxin neutralization assay developed using sera from vaccinated rabbits are used to evaluate the human immune response to PA-based vaccines (237–240).

Nonhuman primates provide a valuable model for anthrax disease because infection with aerosolized spores results in a disease course that most closely matches human infection. Nonhuman primates, including rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques, African green monkeys, and marmosets, represent the only animal models of inhalational anthrax in which anthrax meningitis is consistently observed. Infected nonhuman primates, like humans, also develop bacteremia, lymphadenitis, splenitis, mediastinitis, pneumonia, pleural effusions, hepatitis, adenitis, and vasculitis. Tissues of diseased animals and humans also show hemorrhage, necrosis, and edema. Sera from infected nonhuman primates have been used to develop biomarkers for early diagnosis of infection. Capsule and toxin, detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, chemiluminescence, and mass spectrometry, serve as reliable markers.

Because nonhuman primate responses to infection most closely resemble human physiological and immune responses, these animals are best suited for immunogenicity, toxicity, and safety testing of vaccines and therapeutics for anthrax. Nonhuman primates have been used extensively for studies of antibiotic efficiency. Investigations of the dose, pharmacokinetics, and time course of antibiotic treatment have shown that antibiotics are only effective against germinating spores and vegetative cells. The long-term persistence of spores and extended time periods to germination mean that complete protection from high doses of aerosolized spores requires prolonged antibiotic treatments over more than 30 days.

Rats are somewhat resistant to challenge with B. anthracis spores, but they are exquisitely sensitive to injection of LeTx. Thus, the Fisher 344 strain has been used as a model system for toxin activity. The rat toxin model was key to determining the role of the NLR sensor Nlrp1 in animal susceptibility to LeTx (241, 242). The model also provides a sensitive means to test the efficacy of small-molecule toxin inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, dominant-negative toxin components, and other potential antitoxin countermeasures (229).

Animal Models of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus Infection

The opportunistic properties of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus have been investigated using nasal instillation in mice (243, 244) and intraocular infection in mice and rabbits (245). In all cases, the results highlight the importance of the PlcR regulon in the pathogenic properties of these bacteria. However, established mammalian models of GI infections caused by B. cereus are lacking. It has been hypothesized that rodents are not suitable models of GI-related B. cereus infection because their gut physiology does not support germination of spores and subsequent enterotoxin production (246). In a more recent study, Rolny et al. (247) used intragastric gavage to test the effect of vegetative B. cereus cells on the host immune system. They found some modifications in immune cells in the spleen, Peyer’s patches, and mesenteric lymph nodes but did not report any enterotoxin production. Thus, an appropriate mammal model for enterotoxigenic B. cereus awaits development.

The emetic activity of the B. cereus toxin cereulide was first shown in a rhesus monkey model (248, 249). Results from a study in Suncus murinus suggest that cereulide causes emesis through the 5-HT receptor (206). However, it is still unclear if the S. murinus model reflects the physiology of the human gut. Thus, further studies will be needed using model organisms, such as pig, more closely resembling the human gut physiology.

Insect Models of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis Infection

In insects susceptible to B. thuringiensis infection, the first stage of the disease results from gut paralysis due to the crystal inclusion (250, 251). Cry toxins are responsible for this initial step. The toxins damage the peritrophic membrane and cause lysis of the intestinal cells by producing osmotic shock (252–254). Depending on the amount of Cry toxins and the susceptibility of the insect larvae to a given Cry toxin, the toxemia resulting from toxin ingestion may result in insect death. This toxemia and the paralysis of the gut allow spore germination. Several studies have shown that the presence of B. thuringiensis cells synergizes the toxic effect of the crystals (243, 255–259).

As natural targets of B. thuringiensis, insect larvae are a valuable model for studying the virulence of these bacteria. The utility of this infection model is increased by using insects that are poorly susceptible to the ingestion of crystals alone. A commonly used insect is the lepidopteran species Galleria mellonella (the greater wax moth) because the larvae are killed by the ingestion of B. thuringiensis spore-crystal mixtures but are only weakly affected by the ingestion of crystals alone (243, 258, 259). This model host has also been used to assess the virulence of B. cereus. Many other human pathogens are unable to kill G. mellonella in this infection model, reflecting the entomopathogenic specificity of these two species (260).

The G. mellonella host can be used in two infection methods. In association with Cry toxins to impair the insect defenses, the pathogenicity of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus can be assayed via the oral route. At the last instar, G. mellonella larvae are large enough (2 cm long and 250 mg) to be force-fed, thus allowing the ingestion of defined doses of bacteria (243). Larvae can be raised at various temperatures to mimic different natural conditions, including the mammal environment. This infection model allows determination of a 50% lethal concentration, measurement of bacterial survival, and assessment of the infectious process. The behavior of the bacteria in the intestinal environment, including bacterial factors interacting with the intestinal barrier, can be investigated (261). G. mellonella was used to demonstrate the major role of the PlcR regulon in the virulence of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus (243). The regulon consists of 45 genes encoding a large number of extracellular virulence factors such as degradative enzymes, hemolysins, and cytotoxins (17, 70). The PlcR-regulated metalloproteases InhA2, Bel, and ColB were demonstrated to be involved in B. thuringiensis virulence (38, 262, 263). In addition to G. mellonella, a nematode oral infection model in association with Cry proteins has also revealed virulence factors of B. thuringiensis (264). The ColB protease and another metalloprotease (Bmp1) were found to be involved in the pathogenicity of B. thuringiensis against Caenorhabditis elegans (262, 265).

A second mode of insect infection is direct injection of the bacteria into the hemocoelic cavity of the larva. This model bypasses the intestinal barrier and therefore does not require the crystal proteins. In addition to G. mellonella, the silk worm, B. mori, and several other insect species can be used. Bacteria are injected through the intersegmental membrane between the fourth and fifth abdominal legs of fourth-instar larvae (38). Most insect larvae are highly susceptible to the direct injection of vegetative cells or spores of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus into the hemocoel. This mode of infection led to the identification of multiple virulence factors, including genes associated with (i) iron metabolism and acquisition (266–268), (ii) resistance to the host defenses, including antimicrobial peptides, phagocytic cells, or nitric stress (202, 269–271), (iii) motility (272), and (iv) key transcription factors for B. cereus pathogenicity (273). The major role of the sphingomyelinase in the pathogenicity of B. cereus was also revealed by this method (39), thus confirming the observation that clinical strains of B. cereus overproducing sphingomyelinase were more virulent than environmental strains (203).

Data from these experimental infections clearly demonstrate that B. thuringiensis is a true entomopathogenic bacterium (Fig. 5), producing specific toxins that weaken or kill invertebrates and other virulence factors, shared with other B. cereus group isolates, that allow bacteria to provoke septicemia and death of the host (72). Moreover, it has been shown that these bacteria harbor a regulon conferring the ability to survive in the insect cadaver through a pathway independent of the sporulation and corresponding to a necrotrophic lifestyle (128, 174). This regulon is activated during the stationary phase of the bacteria by the NprR-NprX quorum sensing system and consists of 41 genes encoding several degradative enzymes, including proteases and chitinases. Although the role of each component is not determined, altogether they should contribute to maximizing the consumption of the nutriments found in the host cadaver. Furthermore, the insect model was successfully employed to demonstrate antibiotic-induced small colony variants, a novel persister phenotype of B. cereus (274).

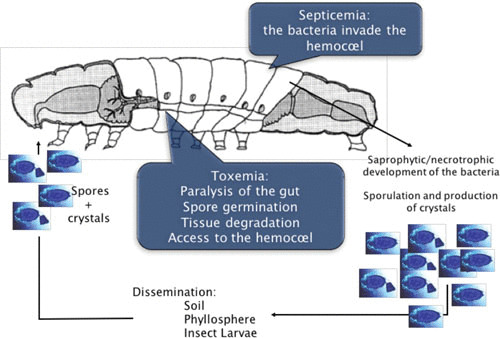

FIGURE 5.

The infectious cycle of B. thuringiensis in a susceptible insect larva. Ingestion of spores and crystals is followed by the dissolution of the crystal in the alkaline environment of the midgut. Insect proteases activate Cry proteins. Spores germinate in the paralyzed insect gut. Cry toxins degrade the peritrophic membrane. Bacteria multiply and express PlcR-regulated genes. The intestinal barrier is disrupted and bacteria gain access to the hemocoel. The bacteria resist host defenses and cause a fatal septicemia. The NprR regulon is activated, and the bacteria survive in the host cadaver. Finally, spores and vegetative cells are disseminated outside of the host.

Cell Culture

Immortalized cell lines are employed for testing the cytotoxic potential of B. cereus strains. Hep2 cells are used to check strains for the emetic toxin cereulide, while Vero cells are commonly used to check strains for their enterotoxic potential (35). However, more recently, it has been reported that different human cell lines show distinct susceptibility for specific enterotoxins, which must be taken into consideration when functional studies on enterotoxins are carried out (205). These results are in line with a previous study from Doll et al. (39) showing that in polarized colon epithelial cells B. cereus sphingomyelinase is a strong inducer of epithelial cell death, by synergistically interacting with Nhe, while most of the cytotoxic effect on primary endothelial cells can be explained by the cytotoxic activity of Nhe (205). Studies carried out on pancreatic beta cells revealed a detrimental effect of cereulide toxin on these cells, even in low concentrations, rendering it possible that long-term uptake of cereulide could have some implications in diabetes (213). Since beta cell dysfunction and cell death play key roles in the pathophysiology of diabetes, it will be important to study the long-term effects of subemetic doses of cereulide in more detail in appropriate eukaryotic cell models.

Furthermore, boar sperm has been used to show the mitochondrial activity of the B. cereus emetic toxin cereulide (275), and the enterotoxic activity of Hbl has been demonstrated in a rabbit ligated ileal loop test (197).

In vitro Simulation of GI Transit

Several systems that mimic gastric passage of B. cereus have been described (276–278). B. cereus spores, and to a certain extent vegetative cells, survive in these models, but enterotoxin production has not been detected, making these models suboptimal for studies of B. cereus enteropathogenicity. Such systems mimicking the physicochemical conditions from mouth to ileum have been successfully used to study probiotic bacteria (279) but lack the influence of host factors, which have been shown to be important for enterotoxin production in B. cereus (116).

VIRULENCE GENE EXPRESSION

Virulence gene expression within the B. cereus group is controlled by complex regulatory circuits. In addition to global transcription regulators, such as CodY and AbrB, that play key roles in the integration of virulence and bacterial metabolism (273, 280, 281), B. cereus group-specific regulators exert control of virulence gene expression on the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. The global transcriptional regulator AtxA, encoded by pXO1 of B. anthracis, plays a key role in the pathogenicity of B. anthracis, while the chromosome-encoded pleiotropic transcriptional regulator PlcR is the key regulator in B. cereus virulence (70, 282). Most of the virulence factors in B. cereus described so far are at least partially under the control of PlcR, except cereulide toxin synthesis, which belongs to the Spo0A-AbrB regulon (283). In addition, some reports highlight the importance of posttranscriptional regulation of virulence factor expression, which is largely unexplored (114, 284, 285).

Global Transcription Regulators

CodY, a global transcriptional regulator integrating virulence and metabolism, plays an essential role in regulation and timing of virulence gene expression in the B. cereus group. CodY, which is highly conserved in low-G+C-content Gram-positive bacteria, senses the nutritional and energetic status of a cell by binding to branched chain amino acids and GTP (286, 287). It often exerts control of virulence factors indirectly by acting on downstream regulators (288, 289). Although the majority of CodY-regulated genes are repressed during rapid growth, CodY is a positive regulator of some virulence genes (286, 290). In B. cereus, CodY governs the expression of virulence factors by impacting key regulatory circuits (66). CodY directly represses cereulide toxin synthesis in emetic B. cereus during early growth stages but acts indirectly on virulence genes belonging to the PlcR regulon by controlling import of the signaling peptide PapR, which is required for PlcR activity (273, 281, 433). CodY was also reported to be essential for full virulence of B. anthracis. Data suggest that CodY exerts indirect positive control on posttranslational regulation of AtxA accumulation (284). By acting, either directly or indirectly, on other virulence regulators, CodY adds an additional level of complexity to the regulatory circuits governing metabolic activities and virulence within the B. cereus group.

AbrB is a global transition state regulator that links virulence and cell development. It has been extensively characterized in B. subtilis but also highly conserved in other Gram-positive bacteria (291, 292). As is true for B. subtilis, AbrB is negatively regulated in the B. cereus group by the response regulator Spo0A at the onset of the transition phase. AbrB has been shown to control the expression of the anthrax toxin genes pagA, lef, and cya in B. anthracis as well as the cereulide (ces) synthetase genes in emetic B. cereus. In B. thuringiensis, abrB represses expression of inhA1 during vegetative growth (293). During early exponential growth phase, abrB-null mutants synthesize elevated levels of anthrax toxin in B. anthracis and cereulide levels in emetic B. cereus (283, 294). Thus, it can be assumed that AbrB plays a pivotal role in the correct timing of toxin expression in B. anthracis as well as in emetic B. cereus.

Alternative sigma factors have also been implicated in transcription of virulence factors of the B. cereus group. The sporulation gene regulator SigH represents a target of the AbrB repressor in B. subtilis (295), and it has been postulated that AbrB acts on anthrax toxin gene expression via control of sigH (296). However, the B. subtilis consensus sequence for recognition by SigH has not been found upstream of the anthrax toxin genes nor upstream of the ces genes in emetic B. cereus, and no direct SigH-dependent toxin promotor activity could be shown (283, 297). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that SigH is not directly linked to toxin gene regulation in B. anthracis or emetic B. cereus. SigB, another alternative sigma factor, may be a minor regulator of virulence in B. anthracis. Although there is no evidence that SigB affects toxin or capsule gene expression, a sigB mutant exhibits reduced virulence in a mouse model of anthrax (298).

RNPP Quorum Sensors

A major trait of the B. cereus group is the unique presence of two transcriptional regulators, PlcR and NprR, forming two distinct quorum sensing systems in association with their cognate signaling peptides, PapR and NprX, respectively (129, 299). In addition to these specific regulators, the bacteria of the B. cereus group produce proteins homologous to the Rap phosphatases of B. subtilis (175, 300). These quorum sensors define the RNPP family according to the name of the prototypical members Rap, NprR, PlcR, and PrgX (301). Quorum sensing systems connect gene expression to cell density, thus coordinating the behavior of the whole bacterial community able to respond to the same signaling peptide. In insects, it was shown that the sequential activity of RNPP regulators (PlcR, NprR, and Rap) controls the physiological stages of B. thuringiensis throughout the infectious cycle, from virulence to sporulation (302).

PlcR positively regulates 45 genes, most of which encode exported virulence factors such as the enterotoxins Hbl and Nhe, the cytotoxin CytK, the cholesterol-dependent hemolysins, and several degradative enzymes (70). As discussed above, PlcR plays a key role in the virulence of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus in their invertebrate or mammal hosts (70, 72, 245). The plcR gene is present in all B. cereus group species but does not always produce a functional protein (303). Notably, in B. anthracis a nonsense mutation inactivates the PlcR function (17, 18). PlcR is a 34-kDa helix-turn-helix-type transcription factor activated upon binding of PapR. This binding induces a drastic conformational change of the dimeric form of PlcR, allowing an appropriate positioning of the helix-turn-helix domains and their binding to the PlcR-boxes located upstream from the −10 region of the PlcR-regulated promoters (299, 301, 304). Binding of PapR to PlcR is highly specific, and polymorphisms exist within the B. cereus group. Four specificity groups, or pherotypes, can be distinguished (305, 306).

NprR is also found in all B. cereus group species and acts as a transcriptional regulator at the onset of sporulation (128). As indicated above, NprR is an RNPP regulator whose transcriptional activity depends on a signaling peptide (NprX) that switches NprR from a dimeric apo form to a tetrameric form (307). Similar to PlcR-PapR, the NprR-NprX system is strain specific, and seven pherotypes were defined within the B. cereus group (129). NprR-NprX activates the transcription of a regulon including genes encoding degradative enzymes (proteases, lipases, and chitinases) and a lipopeptide (kurstakin) involved in biofilm formation (128, 308). Using insect larvae as an infection model, it was shown that the NprR regulon allows bacteria to enter in a necrotrophic lifestyle essential for the survival of the bacilli in the cadavers of infected insects. In the absence of its cognate peptide, the apo form of NprR functions as a phosphatase inhibiting the sporulation process (309). It has been shown that sporulation occurs only in bacteria expressing the NprR regulon and following a necrotrophic lifestyle in the insect cadaver (174). These results are in agreement with the dual function of NprR and indicate that its phosphatase activity should be turned off by NprX to allow the sporulation of the bacteria.

AtxA, the Key Regulator in B. anthracis Virulence

AtxA, named for its control of toxin gene expression (310) and encoded by a pXO1 gene, is the master virulence regulator of B. anthracis. AtxA positively controls transcript levels of the structural genes for anthrax toxin, pagA, lef, and cya, located on pXO1; the capsule biosynthetic operon capBCADE located on pXO2; and multiple other genes on the plasmids and chromosome (5, 282, 311–318). An atxA-null B. anthracis strain is highly attenuated in a murine model of anthrax disease (318, 319). The atxA gene has also been associated with control of B. anthracis development. AtxA activates expression of a pXO2-encoded sporulation kinase inhibitor to repress sporulation in conditions in which AtxA is highly expressed and active (320). This activity may be related to the lack of B. anthracis sporulation during infection.

Paralogous regulators, AcpA and AcpB encoded by pXO2 genes, were first identified as regulators of capBCADE (321, 322). AcpA and AcpB do not appear to affect toxin gene expression but may affect expression of noncapsule genes (282, 323). Data from experiments employing null mutants reveal that expression of the atxA, acpA, and acpB genes is interdependent and suggest that AcpA and AcpB have similar functions. The primary means for AtxA control of capBCADE is via positive regulation of acpA transcription. The acpA gene is located upstream of the cap locus and in the opposite orientation. Two apparent transcriptional start sites, one expressed at a low constitutive level and one controlled positively by AtxA, drive expression of acpA. AcpA can positively affect transcription of capBCADE in the absence of AtxA and AcpB. The acpB gene, located downstream of capBCADE and in the same orientation, is expressed as a monocistronic transcript initiated from a weak constitutive promoter. AcpB, like AcpA, can positively affect capBCADE expression in the absence of the other regulators. A weak transcription terminator located between capE and acpB results in cotranscription of acpB, with capBCADE in roughly 10% of transcripts, thus forming a positive feedback loop (324).

AtxA expression is also subject to complex regulation. Transcription of atxA is affected by temperature, carbohydrate availability, redox potential, metabolic state, and growth phase (325–328). In addition, CodY controls AtxA protein levels posttranscriptionally by an unknown mechanism (284), and AbrB represses atxA expression by binding to the atxA promoter region upstream of the P1 transcriptional start site (294, 329). Finally, an unknown additional repressor binds to the atxA promoter to negatively regulate expression (319).

AtxA, AcpA, and AcpB belong to an emerging class of regulators termed PCVRs (phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system regulation domain [PRD]-containing virulence regulators) (330, 331). Generally, PCVRs contain nucleic acid-binding domains and PRDs subject to phosphorylation by the phosphotransferase system (332). AtxA crystalizes as a dimer, and distinct associated folds predicted that DNA-binding domains and PRDs are apparent in each chain. The model for PRD control of AtxA function is that phosphorylation events at two specific histidines, one in each PRD, have opposing effects on AtxA function.