Abstract

Bacillus cereus is a food-borne opportunistic pathogen that can induce diarrheal and emetic symptoms. It is widely distributed in different environments and can be found in various foods, including fresh vegetables. As their popularity grows worldwide, the risk of bacterial contamination in fresh vegetables should be fully evaluated, particularly in vegetables that are consumed raw or processed minimally, which are not commonly sterilized by enough heat treatment. Thereby, it is necessary to perform potential risk evaluation of B. cereus in vegetables. In this study, 294 B. cereus strains were isolated from vegetables in different cities in China to analyze incidence, genetic polymorphism, presence of virulence genes, and antimicrobial resistance. B. cereus was detected in 50% of all the samples, and 21/211 (9.95%) of all the samples had contamination levels of more than 1,100 MPN/g. Virulence gene detection revealed that 95 and 82% of the isolates harbored nheABC and hblACD gene clusters, respectively. Additionally, 87% of the isolates harbored cytK gene, and 3% of the isolates possessed cesB. Most strains were resistant to rifampicin and β-lactam antimicrobials but were sensitive to imipenem, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, kanamycin, telithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol. In addition, more than 95.6% of the isolates displayed resistance to three kinds of antibiotics. Based on multilocus sequence typing, all strains were classified into 210 different sequence types (STs), of which 145 isolates were assigned to 137 new STs. The most prevalent ST was ST770, but it included only eight isolates. Taken together, our research provides the first reference for the incidence and characteristics of B. cereus in vegetables collected throughout China, indicating a potential hazard of B. cereus when consuming vegetables without proper handling.

Keywords: Bacillus cereus, food-borne pathogen, vegetables, incidence, MLST

Introduction

Bacillus cereus is a Gram-positive, spore-forming opportunistic pathogen that is widespread in different environments and known to cause foodborne outbreaks in humans (Bottone, 2010; Osimani et al., 2018). B. cereus in food products at concentrations exceeding 104 spores or vegetative cells per gram can cause food poisoning (Ehling-Schulz et al., 2006; Fricker et al., 2007; Meldrum et al., 2009). Prevalence of potential emetic and diarrheal B. cereus in different foods has been reported in Finland (Shaheen et al., 2010), Belgium (Rajkovic et al., 2006), Thailand (Chitov et al., 2008), the United Kingdom (Altayar and Sutherland, 2006; Meldrum et al., 2009), the United States (Ankolekar et al., 2009), South Korea (Park et al., 2009), and Africa (Ouoba et al., 2008). B. cereus is also one of the most prevalent foodborne pathogens in France and China (Glasset et al., 2016; Paudyal et al., 2018). From 1994 to 2005, 1,082 food poisoning cases caused by foodborne pathogens had been reported in China. B. cereus caused 145 (13.4%) of these cases, leading to six deaths (Wang et al., 2007).

Vegetables are an indispensable part for human food and nutrition. The World Health Organization recommends taking 400 g of fresh vegetables and fruits daily to promote human health (World Health Organization, 2003). Vegetables are often consumed directly or only with minimal processing that does not eliminate pathogenic bacteria, such as B. cereus (Goodburn and Wallace, 2013; Mogren et al., 2018). Since consumption of fresh vegetable has increased dramatically over the last few decades (Olaimat and Holley, 2012; Hackl et al., 2013), more foodborne outbreaks resulting from contaminated vegetables have simultaneously emerged (Berger et al., 2010; Castro-Ibáñez et al., 2016). For example, food poisoning outbreaks associated with vegetables contaminated by foodborne pathogens in Korea increased from 119 in 1998 to 271 in 2010 (Park et al., 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the contamination level of B. cereus in vegetables.

Consuming food contaminated by B. cereus can lead to gastrointestinal diseases, including diarrhea and emesis. Diarrhea is caused by different enterotoxins, including non-hemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe; Ehling-Schulz et al., 2006), hemolysin BL (Hbl; Ehling-Schulz et al., 2006), and cytotoxin K (CytK; Fagerlund et al., 2004), and emesis is due to a thermo- and acidic-stable non-ribosomal peptide, cereulide, which is encoded by the ces gene cluster (Ehling-Schulz et al., 2005; Ehlingschulz et al., 2015). In addition, B. cereus can induce other non-gastrointestinal-tract infections (Bottone, 2010; Rishi et al., 2013) and may even lead to death (Lund et al., 2000; Posfay-Barbe et al., 2008).

Antimicrobial treatment is the main method to eliminate foodborne pathogens, including B. cereus, in patients with food poisoning. However, antibiotic resistance in B. cereus has already emerged due to the abuse of antibiotics. The therapeutic effect of some antibiotics against antimicrobial-resistant isolates decreases or even disappears, leading to the failure of clinical treatment (Brown et al., 2003; Friedman, 2015; Torkar and Bedenić, 2018). As the consumption of vegetables contaminated with antimicrobial-resistant isolates may lead to more severe infection (Berthold-Pluta et al., 2017), it is important to test the antibiotic resistance of B. cereus in vegetables for food safety and human health.

B. cereus is widely distributed in nature and can contaminate foods primarily through soil and air (European Food Safety Authority [EFSA], 2005; Arnesen et al., 2008). Vegetables are generally planted in fields, where they are exposed to soil, and they are exposed to air during transportation and sale; they can therefore be easily contaminated by this pathogenic bacterium. B. cereus contamination in vegetables has been reported. The contamination rate in different vegetables ranged from 29.0 to 70.0% in South Korea (Chon et al., 2012, 2015; Kim H. J. et al., 2016; Kim Y. J. et al., 2016). In Mexico City, B. cereus was identified in 57% of the 100 analyzed samples (Flores-Urban et al., 2014). The contamination rate in different vegetables in southeast of Spain varied greatly (Valero et al., 2002).

As an essential daily nutrient, to date, no study has evaluated the occurrence rate of B. cereus in vegetables accounting for the whole of China. Therefore, in this study, we analyzed the contamination, genotypic diversity, pathogenic potential, and antimicrobial resistance of B. cereus isolated from vegetables in China to obtain an overview on the potential risk.

Materials and Methods

Vegetable Sample Collection

A total of 419 vegetable samples (89 Coriandrum sativum L samples, 85 var. ramosa Hort. samples, 134 Cucumis sativus L. samples, and 111 Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. samples) were collected from the local markets and supermarkets of 39 major cities in China (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1) from 2011 to 2016, according to the general sample collection guidelines of the National Food Safety Standard (The Hygiene Ministry of China, 2010b). The samples were placed in sealed bags, transferred to the laboratory in a low-temperature (below 4°C) sampling box, and immediately subjected to microbiological analysis after sending back to the laboratory.

Table 1.

Prevalence and contamination level of B. cereus in different vegetables.

| Type of vegetable | Contamination rate (%)a | MPN value (MPN/g)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPN < 3 (%) | 3 ≤ MPN < 1100 (%) | 1100 ≤ MPN (%) | ||

| Coriandrum sativum L | 56/89 (62.92) | 1/56 (1.79) | 38/56 (67.86) | 17/56 (30.36) |

| var. ramosa Hort. | 49/85 (57.65) | 5/49 (10.20) | 41/49 (83.67) | 3/49 (6.12) |

| Cucumis sativus L. | 63/134 (47.01) | 12/63 (19.05) | 50/63 (79.37) | 1/63 (1.59) |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | 43/111 (38.74) | 19/43 (44.19) | 24/43 (55.81) | 0/43 (0.00) |

| Total | 211/419 (50.36) | 37/211 (17.54) | 153/211 (72.51) | 21/211 (9.95) |

aContamination rate = number of positive samples/total samples. bMPN value (MPN/g) = most probable number of B. cereus per gram sample.

Isolation and Identification of B. cereus

Twenty-five grams of vegetable samples was cut into pieces, transferred into a sterile homogenizer containing 225 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 mol/L), and then homogenized at 8,000 rpm for 2 min using a rotary blade homogenizer. The homogenized solution and its 1/10 and 1/100 dilutions were used to detect B. cereus qualitatively and quantitatively according to the B. cereus test rules given by the National Food Safety Standard (The Hygiene Ministry of China, 2010a), as described previously (Gao et al., 2018). Mannitol yolk polymyxin (MYP) agar plate test, parasporal crystal observation (to distinguish between B. cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis), root growth observation, hemolysis test, catalase test, motility test, nitrate reduction test, casein decomposition test, lysozyme tolerance test, glucose utilization test, and acetyl methyl alcohol test were conducted for species detection. The most probable number (MPN) method was adopted for quantitative detection of species. Briefly, 1 ml of the homogenized solution and its 1/10 and 1/100 dilutions were inoculated into three tubes each containing 10 ml peptone soy polymyxin broth medium. The nine cultures were incubated at 30°C for 48 h. Then, the cultures were streaked onto MYP plates and incubated at 30°C for at least 24 h. Presumptive colonies were picked for species identification. MPN was determined based on the MPN table provided by the National Food Safety Standard (The Hygiene Ministry of China, 2010a) and the number of positive culture(s) to calculate the MPN of B. cereus per gram sample (MPN/g).

Detection of Emetic and Enterotoxin Toxin Genes

Genomic DNA was obtained using the HiPure Bacterial DNA Kit (Magene, United States) following the manufacturer’s specifications. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was conducted to detect the cereulide synthetase gene (cesB) and seven enterotoxin genes (nheA, nheB, nheC, hblA, hblC, hblD, and cytK) with a 20 μl reaction mixture consisting of 50 ng genomic DNA, 12.5 μl PCR Premix TaqTM (Takara, China), and 2 μM of each primer (Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001; Fagerlund et al., 2004; Ehling-Schulz et al., 2005; Oltuszak-Walczak and Walczak, 2013). The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Target fragment length (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HblA-F | GTGCAGATGTTGATGCCGAT | 320 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| HblA-R | ATGCCACTGCGTGGACATAT | |||

| HblC-F | AATGGTCATCGGAACTCTAT | 750 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| HblC-R | CTCGCTGTTCTGCTGTTAAT | |||

| HblD-F | AATCAAGAGCTGTCACGAAT | 430 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| HblD-R | CACCAATTGACCATGCTAAT | |||

| NheA-F | TACGCTAAGGAGGGGCA | 500 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| NheA-R | GTTTTTATTGCTTCATCGGCT | |||

| NheB-F | CTATCAGCACTTATGGCAG | 770 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| NheB-R | ACTCCTAGCGGTGTTCC | |||

| NheC-F | CGGTAGTGATTGCTGGG | 583 | 55 | Hansen and Hendriksen, 2001 |

| NheC-R | CAGCATTCGTACTTGCCAA | |||

| cytK-F | AAAATGTTTAGCATTATCCGCTGT | 238 | 55 | Oltuszak-Walczak and Walczak, 2013 |

| cytK-R | ACCAGTTGTATTAATAACGGCAATC | |||

| cesB-F | GGTGACACATTATCATATAAGGTG | 1271 | 58 | Ehling-Schulz et al., 2005 |

| cesB-R | GTAAGCGAACCTGTCTGTAACAACA | |||

| glpF-F | GCGTTTGTGCTGGTGTAAGT | 549 | 59 | PubMLST (http://pubmlst.org/bcereus/info/primers.shtml) |

| glpF-R | CTG CAATCGGAAGGAAGAAG | |||

| gmk-F | TTAAGTGAGGAAGGGTAGG | 600 | 56 | |

| gmk-R | AATGTTCACCAACCACAA | |||

| ilvD-F | GGGCAAACATTAAGAGAA | 556 | 58 | |

| ilvD-R | TTCTGGTCGTTTCCATTC | |||

| pta-F | AGAGCGTTTAGCAAAAGAA | 576 | 56 | |

| pta-R | CAATGCGAGTTGCTTCTA | |||

| pur-F | GCTGCGAAAAATCACAAA | 536 | 56 | |

| pur-R | CACGATTCGCTGCAATAA | |||

| pycA-F | GTTAGGTGGAAACGAAAG | 550 | 57 | |

| pycA-R | CGTCCAAGTTTATGGAAT | |||

| tpi-F | CCAGTAGCACTTAGCGAC | 553 | 58 | |

| tpi-R | GAAACCGTCAAGAATGAT |

Antimicrobial Resistance Testing

The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method was employed to evaluate the antimicrobial resistant, intermediate, and sensitive profiles of the isolates to 20 selected antibiotics as previously described (The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2010; Gao et al., 2018). The zone diameter interpretive standards were referred to the standard for Staphylococcus aureus (The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2010).

Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) Gene Amplification, Sequencing, and Determination

Seven housekeeping genes, namely glp, gmk, ilvD, pta, pur, pycA, and tpi, were amplified with different primers and conditions (Table 2) according to MLST protocol for B. cereus in PubMLST1. The sequence of each PCR product was sequenced and submitted to the PubMLST database to get the corresponding allele number. The multilocus sequence type (ST) of each isolate was obtained by ranking and submitting seven housekeeping gene allele numbers. New STs were assigned by the MLST website administrator. A minimum spanning tree was constructed with PHYLOViZ 2.0 software (Instituto de Microbiologia, Portugal) according to the relationships between MLST alleles (Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al., 2016) and to visualize the relatedness and genetic diversity of different isolates.

Results

Prevalence Analysis of B. cereus in Vegetables

B. cereus was detected in 211 of 419 (50%) vegetable samples (Table 1), and the contaminated samples were distributed in all 39 different cities in China from where the samples were collected. The contamination rate was higher than 60% in 15 cities presented, and only three cities had a contamination rate below 20% (Supplementary Figure S1).

The positive rates of B. cereus were 62.92% (56/89) for C. sativum L, 57.65% (49/85) for var. ramosa Hort., 47.01% (63/134) for C. sativus L., and 38.74% (43/111) for L. esculentum Mill., respectively. Contamination levels of 9.95% (21/211) of all the samples exceeded 1,100 MPN/g. Among all positive samples, the contamination levels for the C. sativum L (30.36%; 17/56) and var. ramosa Hort. (6.12%; 3/49) samples exceeded 1,100 MPN/g, which was higher than the contamination levels for the C. sativus L. and L. esculentum Mill. samples.

Distribution of Virulence Genes Among B. cereus Isolates

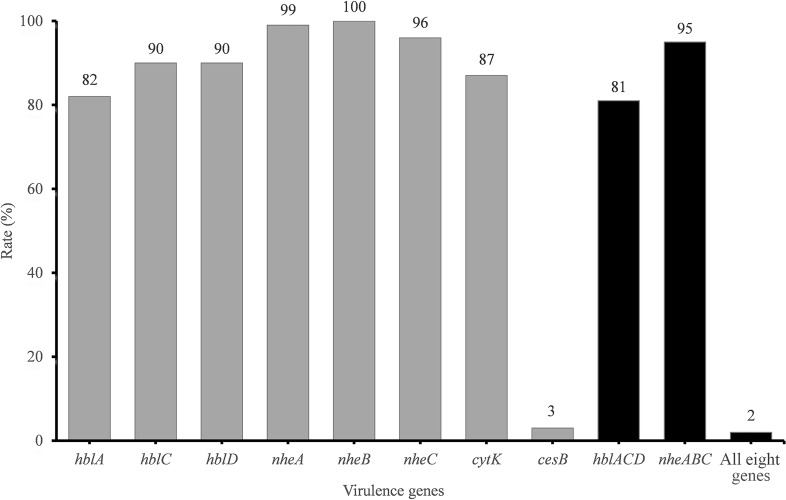

The presence of toxin genes is summarized in Figure 1. The cereulide synthetase gene cesB was detected in only 3% of isolates. In contrast, the rate of enterotoxin gene detection was very high. hbl genes encoding the Hbl toxin complex were detected in 81% of the samples. Additionally, 99, 100, and 96% of all isolates harbored nheA, nheB, and nheC, respectively. However, only 95% of the isolates harbored the integrated Nhe-encoding gene cluster nheABC. cytK was detected in 87% of the strains.

FIGURE 1.

Detection rate of virulence genes in B. cereus from vegetables. The number at the top of the bars represents the positive rate of corresponding toxin genes. hblACD and nheABC mean that the strains are positive for hblA, hblC, and hblD or for nheA, nheB, and nheC at the same time, respectively. “All eight genes” presents the strains with all the detected toxin genes.

The virulence gene distribution could be divided into 20 different profiles. Only five isolates, namely, 2841-1B, 3713, 3715, 3715-2A, and 3740, possessed all eight virulence genes. Two isolates (3265 and 3463) harbored the least virulence gene list (nheA-nheB). The main gene profile (70.1% of all isolates) was hblA-hblC-hblD-nheA-nheB-nheC-cytK.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test of B. cereus Isolates

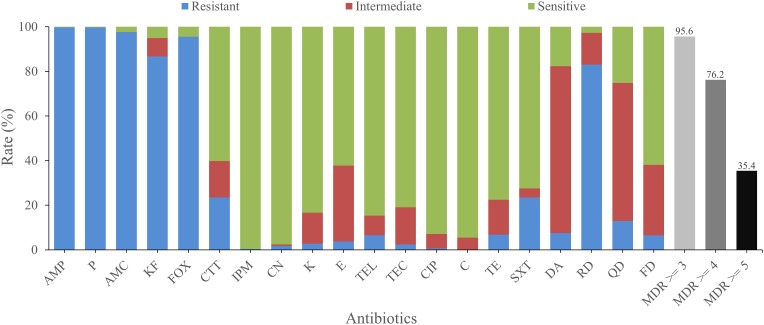

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of all isolates were tested with 20 antimicrobials. Most isolates were found to be resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanic (AMC; 97.6%), cephalothin (KF; 86.7%), penicillin (P; 99.7%), ampicillin (AMP; 99.7%), cefoxitin (FOX; 95.6%), which belong to β-lactams, as well as rifampin (RD, 83.0%), an ansamycin. On the other hand, most isolates were sensitive to some other antimicrobials, such as kanamycin (K; 83.3%), gentamicin (CN; 97.6%), telithromycin (TEL; 84.7%), imipenem (IPM; 99.7%), ciprofloxacin (CIP; 92.9%), chloramphenicol (C; 94.6%), and teicoplanin (TEC; 81.0%). Besides, most isolates exhibited intermediate resistance to quinupristin (QD; 61.9%) and clindamycin (DA; 74.8%; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Antimicrobial resistance of B. cereus from vegetables. The blue, red, and green bars represent the proportion of resistant, moderately resistant, and sensitive strains, respectively. The light gray, gray, or dark bar represents the proportion of strains with multidrug resistance (MDR) to at least three, four, and five classes of antibiotics, respectively.

There were 74 antimicrobial resistant profiles for all isolates. The strain 41-1 and 1515-1A turned out to be the most highly resistant isolates, which were resistant to 12 antibiotics (AMP-KF-FOX-P-AMC-CTT-SXT-DA-RD-QD-TEL-FD and AMP-KF-FOX-P-AMC-TE-CTT-DA-RD-QD-TEL-FD, respectively). In contrast, the most sensitive strain, 3763, showed resistance to only two antibiotics (FOX-TE). AMP-KF-FOX-P-AMC-RD was the most common antimicrobial resistant profile (91 of 294 strains). We also evaluated the multidrug resistance (MDR; Magiorakos et al., 2012) profiles and found that 95.6, 76.2, and 35.4% of isolates displayed simultaneous resistance to more than three, four, and five types of antimicrobials, respectively (Figure 2).

Multilocus Sequence Typing and Cluster Analysis

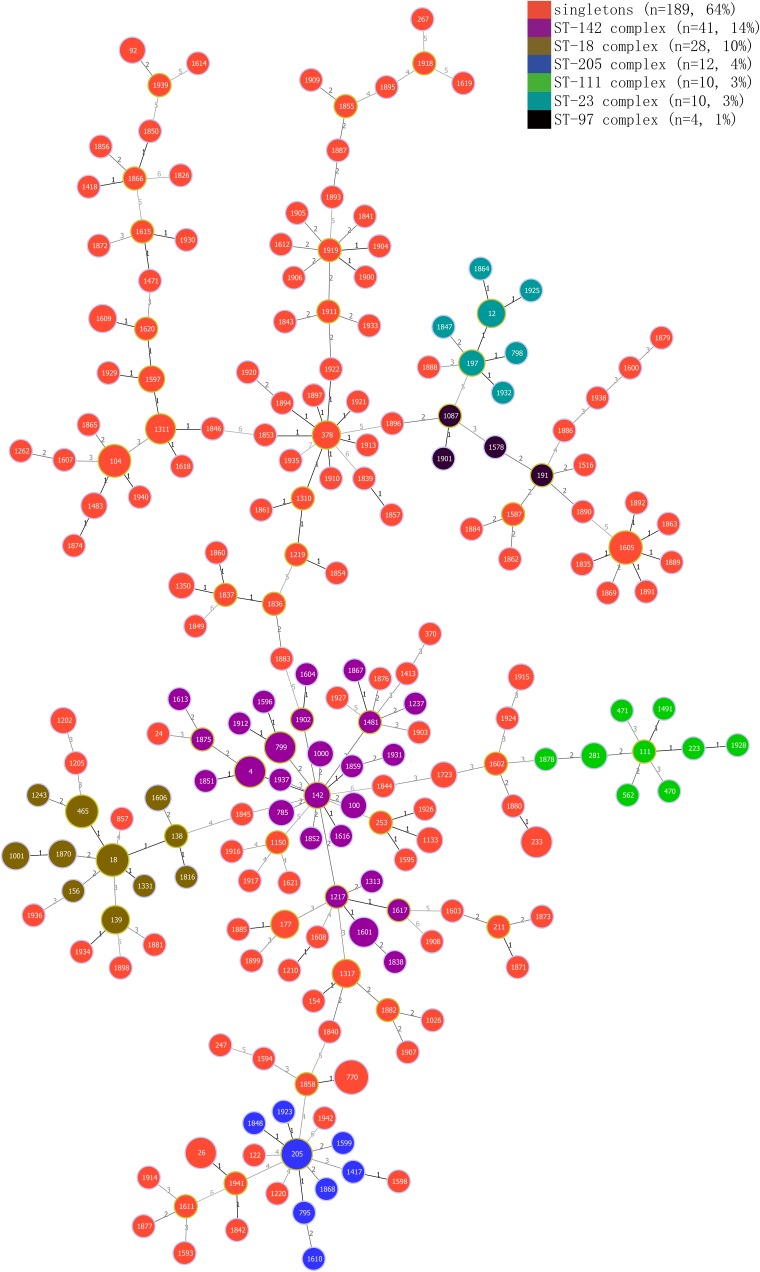

Genetic diversity was analyzed by the MLST method. Among all 294 strains, 210 STs were assigned, and 145 strains were assigned to 137 new STs. Additionally, 175 of all the 210 (83%) STs included a single strain, 35 STs included two to eight isolates, and only ST-770 included eight isolates, followed by ST-1605, which included seven strains. Five isolates belonged to ST-26, which is associated with clinical isolates. All 210 STs were grouped into six clonal complexes (CCs) and 189 singletons. The ST-142 complex was most frequent, including 41 isolates, while the ST-18, ST-23, ST-97, ST-111, and ST-205 complexes contained 28, 10, 4, 10, and 12 isolates, respectively (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Minimum spanning tree and genetic diversity of B. cereus from vegetables. Different colors inside the circles represent different clonal complexes and singletons. The numbers inside the circles represent the corresponding sequence types (STs). Gradation of the line color and the corresponding number along the line represent variation of the seven loci between two strains at both ends of the line. The dominant STs are represented by the circles with larger diameters.

Discussion

Prevalence of B. cereus Isolates in Vegetables

Few studies have evaluated pathogenic B. cereus in vegetables worldwide and no report has focused on the whole of China. In our study here, we found that 50% of all vegetable samples collected from 39 major cities in China contained B. cereus. The contamination level was more or less the same as those of previous surveys in other countries, i.e., 20–48% in Korea (Chon et al., 2015; Kim H. J. et al., 2016; Park et al., 2018), 57% in Mexico City (Flores-Urban et al., 2014), and 52% in the southeast of Spain (Valero et al., 2002). These reports, together with ours, indicate that B. cereus contamination in vegetables is common in several countries and suggest that consumption of vegetables contaminated with B. cereus is a potential health hazard (Valero et al., 2002; Kim Y. J. et al., 2016). The high level of contamination by B. cereus may be partly attributed to contact with soil or air during field planting (European Food Safety Authority [EFSA], 2005; Arnesen et al., 2008) and exposure to air during transportation and sale. Upon contamination, B. cereus may form a biofilm on the surface of vegetables, resulting in its persistent difficulty to be eliminated (Majed et al., 2016). B. cereus-positive samples may also contaminate other vegetables by contact transmission. According to the Microbiological Guidelines for Food of Hong Kong, China (Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, 2014), even though the amounts of B. cereus between 103 and 105 CFU/g in ready-to-eat foods are considered to be “acceptable,” they pose potential risks, and the raw materials, processing period, and environment should be examined to investigate the reason why these foods are contaminated; if the amounts of B. cereus in ready-to-eat foods are more than 105 CFU/g, their quality is considered to be “unsatisfactory” and their sale should be stopped. The standards of microbiological limits for ready-to-eat foods in Australia and New Zealand (New South Wales Food Authority, 2009), however, stipulate that the “acceptable” level of B. cereus is 102–103 CFU/g, and an “unsatisfactory” level is 103–104 CFU/g. The United Kingdom microbiological testing standards (Health Protection Agency, 2009) for ready-to-eat foods stipulate that the “acceptable” level of B. cereus in ready-to-eat foods is 103–105 CFU/g, and a level of more than 105 CFU/g of B. cereus is considered to be “unsatisfactory.” Of all the B. cereus-positive samples in this study, 9.95% (21/211), mainly of C. sativum L and var. ramosa Hort., had contamination levels of more than 1,100 MPN/g. The contamination levels of these samples were at least at the “acceptable” level according to Hong Kong and United Kingdom standards and at the “unsatisfactory” level according to Australia and New Zealand standards. This suggests that B. cereus-contaminated vegetables pose a potential risk of causing foodborne disease, and care needs to be taken when consuming them directly or with minimal processing.

Multilocus Sequence Typing and Genetic Diversity

MLST is a crucial epidemiological typing method based on the sequences of seven different housekeeping gene loci; it is used in studies of evolution and population diversity of B. cereus isolates (Erlendur et al., 2004; Cardazzo et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). In this study, we employed MLST to analyze genetic polymorphism in isolates from vegetables. Most of the isolates were assigned to singleton (Figure 3). The six CCs were distributed in separate samples, except ST-23 complex and ST-97 complex. ST-18 complex, ST-23 complex, ST-142 complex, and ST-205 complex even crossed with some singletons, indicating high genetic diversity of the isolates. However, we could not find any unique STs that existed in only one particular vegetable variety. Five strains, two of which were isolated from var. ramosa Hort, one from C. sativum L, and the remaining two from C. sativus L., were assigned to ST26, the same molecular type of clinical isolates NC7401 and F4810/72 (Agata et al., 2002; Fricker et al., 2007). Three out of these five isolates were identified as potential emetic strains. As the preformed cereulide in foods is persistent and may also lead to food poisoning (Agata et al., 1995), there is a potential risk when consuming these vegetables directly or with minimal processing. Interestingly, we found that all isolates that belonged to the ST-18 complex, ST-97 complex, and ST-142 complex harbored the same virulence gene profile (hblA-hblC-hblD-nheA-nheB-nheC-cytK), while other CCs showed no such phenomenon. Additionally, 30 of 32 isolates belonging to ST-18 and ST-97 complexes showed resistance to cefotetan (CTT, 30 μg), whereas only 10 of 73 isolates belonging to the other four CCs showed similar resistance, which may be explained by the properties of founder clones of different CCs.

Virulence Gene Detection and Potential Toxicity

Diarrhea caused by B. cereus is attributed to different enterotoxins produced by these strains in the small intestine (Jeßberger et al., 2015), including Hbl, Nhe (Lund and Granum, 1997), and CytK (Lund et al., 2000). In this study, we evaluated seven enterotoxin genes in B. cereus, and the positive rates of nheABC, hblACD, and cytK were 95, 81, and 87%, respectively (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S1). The positive rates of nheABC, hblACD, and cytK were higher than those found in Korea (69.5, 41.7, and 74.2%; Park et al., 2018), but the hblA gene was detected in only 82% of isolates, which is lower than that reported in Mexico City (Flores-Urban et al., 2014). When considering different kinds of food, the nheABC frequency in our vegetables was lower than in Sunsik from Korea (Chon et al., 2012) or in pasteurized milk from China (Gao et al., 2018), but the cytK detection rate was much higher than those in rice and cereals from Korea (55%; Park et al., 2009), in Sunsik from Korea (77%; Chon et al., 2012), and in pasteurized milk from China (73%; Gao et al., 2018). Owing to the properties of foods consumed raw or processed minimally, the wider distribution of diarrheal B. cereus in these vegetables and their potential hazard cannot be neglected.

Emetic symptoms are caused by the emetic toxin cereulide. The positive rate of cesB was 3%, which is higher than those reported in Korea and Mexico City (Flores-Urban et al., 2014; Chon et al., 2015; Park et al., 2018), almost the same as that (2.9%) in Sunsik of Korea (Chon et al., 2012), but slightly lower than the 5% in pasteurized milk of China (Gao et al., 2018). Although the positive rate of cesB was quite low when compared with the rates of enterotoxins, cereulide is very persistent and heat-stable. Even emetic toxin remaining in sterilized food can cause emetic symptoms accordingly (Agata et al., 1995), the emetic isolates in these raw consuming vegetables are still potential risks.

Antimicrobial Resistance of B. cereus Isolates

B. cereus infection may lead to diarrhea, vomiting, and even death (Hilliard et al., 2003; Evreux et al., 2007; Jean-Winoc et al., 2013; Ramarao et al., 2014). Antibiotic resistance test may provide a theoretical reference for the clinical treatment of B. cereus food poisoning and infection. Detailed antimicrobial resistance information of the isolates from vegetables is shown in Supplementary Table S2. More than 72.5% of all isolates were susceptible to six classes of antimicrobial agents, including aminoglycosides (CN, K), ketolide (TEL), glycopeptides (TEC), quinolones (CIP), phenylpropanol (C), tetracyclines (TE), and folate pathway inhibitors (SXT). A total of 60.2 and 99.7% of the strains were also susceptible to third-generation cephalosporin (CTT) and penems (IPM), respectively. More than 83.0% of the isolates showed resistance to other β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins (AMP, P), β-Lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (AMC), cephems (KF, FOX), and ansamycins (RD). The high resistance of B. cereus to β-lactam antimicrobials has been widely reported and may be due to the synthesis of β-lactamase (Philippon et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2004; Park et al., 2018). Notably, 83.0% of the isolates showed resistance to rifampin (RD), which is much higher than the resistance rates of vegetables in Korea (only 48.7%; Park et al., 2018) and even higher than those of different kinds of foods, including rice and cereal (62%; Park et al., 2009), ready-to-eat foods (0%; Agwa et al., 2012), and traditional dairy products (0%; Owusu-Kwarteng et al., 2017). This may be ascribed to the usage of antibiotics in different countries or the evolution of strains toward rifampicin resistance. These results emphasize the need for caution when using β-lactams and ansamycins (such as RD) for the clinical treatment of B. cereus. On the other hand, 95.6, 76.2, and 35.4% of isolates showed resistance to more than three, four, and five classes of antibiotics simultaneously, respectively, suggesting the need to monitor multiple drug resistance in B. cereus.

Conclusion

Vegetables such as L. esculentum Mill., C. sativus L., var. ramosa Hort., and so on are usually consumed directly or with minimal processing, so potential hazards associated with B. cereus-contaminated vegetables should not be ignored. The results in this study revealed a high incidence of B. cereus in vegetable samples collected from across China, for the first time as we know. Of all the samples, 21/211 (9.95%), mainly of C. sativum L and var. ramosa Hort., had contamination levels of more than 1,100 MPN/g. According to the Microbiological Guidelines for Food of Hong Kong, China (Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, 2014), the United Kingdom microbiological testing standards for ready-to-eat foods (Health Protection Agency, 2009), and the standards of microbiological limits for ready-to-eat foods in Australia and New Zealand (New South Wales Food Authority, 2009), the contamination levels of these samples were at the “acceptable” level according to Hong Kong and United Kingdom standards and at the “unsatisfactory” level according to the Australia and New Zealand standards. These contamination levels indicate a potential risk caused by the consumption of B. cereus-contaminated vegetables either directly or with minimal processing and should be kept in mind while assessing the quality of vegetables. If necessary, the reason for the contamination should also be traced. The pathogenic ST ST26 was detected in vegetable isolates. Seven enterotoxin genes associated with diarrheal symptoms were widespread among isolates, and the emetic toxin gene was also detected. In addition, most isolates were resistant to β-lactam antimicrobials, such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, penicillin, ampicillin, cephalothin, cefoxitin, and rifampin. Our results indicate a potential risk of consuming vegetables without sufficient processing and the increasing difficulties in eliminating B. cereus with antibiotics. To ensure the health and safety for the public, it is therefore necessary to develop new methods to prevent contamination and consequent potential foodborne outbreak induced by B. cereus in raw consuming vegetables.

Author Contributions

QW, YD, JW, JMZ, and PY conceived the project and designed the experiments. PY, SY, HG, YZ, XL, JHZ, SW, QG, LX, HZ, RP, and TL performed the experiments. QW and YD supervised the project. PY and YD analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. QW, JW, and YD complemented the writing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

YD is awarded the 1000-Youth Elite Program (The Recruitment Program of Global Experts in China).

Funding. We would like to acknowledge the financial support of the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFC1602500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31730070), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (Grant No. 201604016068), State Key Laboratory of Applied Microbiology Southern China (Grant Nos. SKLAM004-2016 and SKLAM006-2016), GDAS’ Special Project of Science and Technology Development (Grant No. 2017GDASCX-0201), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the 111 Project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00948/full#supplementary-material

Sampling cities where the vegetables were collected.

Prevalence of virulence genes in B. cereus isolated from vegetables in China.

Results of antimicrobial resistance test for B. cereus isolates in the study.

References

- Agata N., Ohta M., Mori M., Isobe M. (1995). A novel dodecadepsipeptide, cereulide, is an emetic toxin of Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 129 17–19. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata N., Ohta M., Yokoyama K. (2002). Production of Bacillus cereus emetic toxin (cereulide) in various foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 73 23–27. 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agwa O. K., Uzoigwe C. I., Wokoma E. C. (2012). Incidence and antibiotic sensitivity of Bacillus cereus isolated from ready to eat foods sold in some markets in Portharcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Asian J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Environ. Sci. 14 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Altayar M., Sutherland A. D. (2006). Bacillus cereus is common in the environment but emetic toxin producing isolates are rare. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100 7–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankolekar C., Rahmati T., Labbé R. G. (2009). Detection of toxigenic Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis spores in U.S. rice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 128 460–466. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen L. P. S., Fagerlund A., Granum P. E. (2008). From soil to gut: Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32 579–606. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C. N., Sodha S. V., Shaw R. K., Griffin P. M., Pink D., Hand P., et al. (2010). Fresh fruit and vegetables as vehicles for the transmission of human pathogens. Environ. Microbiol. 12 2385–2397. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold-Pluta A., Garbowska M., Stefańska I., Pluta A. (2017). Microbiological quality of selected ready-to-eat leaf vegetables, sprouts and non-pasteurized fresh fruit-vegetable juices including the presence of Cronobacter spp. Food Microbiol. 65 221–230. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottone E. J. (2010). Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 382–398. 10.1128/CMR.00073-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R., Gentry D., Becker J. A., Ingraham K., Holmes D. J., Stanhope M. J. (2003). Horizontal transfer of drug-resistant aminoacyl-transfer-RNA synthetases of anthrax and Gram-positive pathogens. EMBO Rep. 4 692–698. 10.1038/sj.embor.embor881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardazzo B., Negrisolo E., Carraro L., Alberghini L., Patarnello T., Giaccone V. (2008). Multiple-locus sequence typing and analysis of toxin genes in Bacillus cereus food-borne isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 850–860. 10.1128/aem.01495-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Ibáñez I., Gil M. I., Allende A. (2016). Ready-to-eat vegetables: current problems and potential solutions to reduce microbial risk in the production chain. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 85(Part B), 284–292. 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.11.073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. H., Tenover F. C., Koehler T. M. (2004). Beta-lactamase gene expression in a penicillin-resistant Bacillus anthracis strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 4873–4877. 10.1128/aac.48.12.4873-4877.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitov T., Dispan R., Kasinrerk W. (2008). Incidence and diarrhegenic potential of Bacillus cereus in pasteurized milk and cereal products in Thailand. J. Food Saf. 28 467–481. 10.1111/j.1745-4565.2008.00125.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chon J. W., Kim J. H., Lee S. J., Hyeon J. Y., Seo K. H. (2012). Toxin profile, antibiotic resistance, and phenotypic and molecular characterization of Bacillus cereus in Sunsik. Food Microbiol. 32 217–222. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon J. W., Yim J. H., Kim H. S., Kim D. H., Kim H., Oh D. H., et al. (2015). Quantitative prevalence and toxin gene profile of Bacillus cereus from ready-to-eat vegetables in South Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 12 795–799. 10.1089/fpd.2015.1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlingschulz M., Frenzel E., Gohar M. (2015). Food-bacteria interplay: pathometabolism of emetic Bacillus cereus. Front. Microbiol. 6:704. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehling-Schulz M., Guinebretiere M. H., Monthan A., Berge O., Fricker M., Svensson B. (2006). Toxin gene profiling of enterotoxic and emetic Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 260 232–240. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehling-Schulz M., Vukov N., Schulz A., Shaheen R., Andersson M., Martlbauer E., et al. (2005). Identification and partial characterization of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene responsible for cereulide production in emetic Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 105–113. 10.1128/aem.71.1.105-113.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlendur H., Tourasse N. J., Roger M., Caugant D. A., Anne-Brit K. (2004). Multilocus sequence typing scheme for bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 191–201. 10.1128/AEM.70.1.191-201.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority [EFSA] (2005). Opinion of the scientific panel on biological hazards on Bacillus cereus and other Bacillus spp. in foodstuffs. EFSA J. 175 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Evreux F., Delaporte B., Leret N., Buffet-Janvresse C., Morel A. (2007). A case of fatal neonatal Bacillus cereus meningitis. Arch. Pediatr. 14 365–368. 10.1016/j.arcped.2007.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlund A., Ween O., Lund T., Hardy S. P., Granum P. E. (2004). Genetic and functional analysis of the cytK family of genes in Bacillus cereus. Microbiology 150 2689–2697. 10.1099/mic.0.26975-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Urban K. A., Natividad-Bonifacio I., Vazquez-Quinones C. R., Vazquez-Salinas C., Quinones-Ramirez E. I. (2014). Detection of toxigenic Bacillus cereus strains isolated from vegetables in Mexico City. J. Food Prot. 77 2144–2147. 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-13-479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and environmental hygiene department (2014). Microbiological Guidelines for Food. Hong Kong: Food and environmental hygiene department. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M., Messelhäußer U., Busch U., Scherer S., Ehling-Schulz A. M. (2007). Diagnostic real-time PCR assays for the detection of emetic Bacillus cereus strains in foods and recent food-borne outbreaks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 1892–1898. 10.1128/AEM.02219-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. (2015). Antibiotic-resistant bacteria: prevalence in food and inactivation by food-compatible compounds and plant extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63 3805–3822. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T., Ding Y., Wu Q., Wang J., Zhang J., Yu S., et al. (2018). Prevalence, virulence genes, antimicrobial susceptibility, and genetic diversity of Bacillus cereus isolated from pasteurized milk in China. Front. Microbiol. 9:533. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasset B., Herbin S., Guillier L., Cadelsix S., Vignaud M., Grout J., et al. (2016). Bacillus cereus-induced food-borne outbreaks in France, 2007 to 2014: epidemiology and genetic characterisation. Euro Surveill. 21:30413. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.48.30413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodburn C., Wallace C. A. (2013). The microbiological efficacy of decontamination methodologies for fresh produce: a review. Food Control 32 418–427. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.12.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackl E., Ribarits A., Angerer N., Gansberger M., Hölzl C., Konlechner C., et al. (2013). Food of plant origin: production methods and microbiological hazards linked to food-borne disease. Reference: CFT/EFSA/BIOHAZ/2012/01 Lot 2 (Food of plant origin with low water content such as seeds, nuts, cereals, and spices). EFSA J. 10:403E 10.2903/sp.efsa.2013.EN-403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B. M., Hendriksen N. B. (2001). Detection of enterotoxic Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis strains by PCR analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 185–189. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.185-189.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Protection Agency (2009). Guidelines for Assessing the Microbiological Safety of Ready-to-Eat Foods Placed on the Market [S/OL]. London: Health Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard N. J., Schelonka R. L., Waites K. B. (2003). Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a preterm neonate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 3441–3444. 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3441-3444.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Winoc D., Nalini R., Claudine D., Marie D., Nadège B. N., Marie-Hélène G., et al. (2013). Bacillus cereus and severe intestinal infections in preterm neonates: putative role of pooled breast milk. Am. J. Infect. Control 41 918–921. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeßberger N., Krey V. M., Rademacher C., Böhm M. E., Mohr A. K., Ehling-Schulz M., et al. (2015). From genome to toxicity: a combinatory approach highlights the complexity of enterotoxin production in Bacillus cereus. Front. Microbiol. 6:560. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Koo M., Hwang D., Choi J. H., Kim S. M., Oh S. W. (2016). Contamination patterns and molecular typing of Bacillus cereus in fresh-cut vegetable salad processing. Appl. Biol. Chem. 59 573–577. 10.1007/s13765-016-0198-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J., Kim H. S., Kim K. Y., Chon J. W., Kim D. H., Seo K. H. (2016). High occurrence rate and contamination level of Bacillus cereus in organic vegetables on sale in retail markets. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 13 656–660. 10.1089/fpd.2016.2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Lai Q., Du J., Shao Z. (2017). Genetic diversity and population structure of the Bacillus cereus group bacteria from diverse marine environments. Sci. Rep. 7:689. 10.1038/s41598-017-00817-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T., De Buyser M. L., Granum P. E. (2000). A new cytotoxin from Bacillus cereus that may cause necrotic enteritis. Mol. Microbiol. 38 254–261. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T., Granum P. E. (1997). Comparison of biological effect of the two different enterotoxin complexes isolated from three different strains of Bacillus cereus. Microbiology 143(Pt 10), 3329–3336. 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R. B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M. E., Giske C. G., et al. (2012). Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 268–281. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majed R., Faille C., Kallassy M., Gohar M. (2016). Bacillus cereus biofilms—same, only different. Front. Microbiol. 7:1054 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum R. J., Little C. L., Sagoo S., Mithani V., Mclauchlin J., De P. E. (2009). Assessment of the microbiological safety of salad vegetables and sauces from kebab take-away restaurants in the United Kingdom. Food Microbiol. 26 573–577. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogren L., Windstam S., Boqvist S., Vagsholm I., Soderqvist K., Rosberg A. K., et al. (2018). The hurdle approach—a holistic concept for controlling food safety risks associated with pathogenic bacterial contamination of leafy green vegetables. A review. Front. Microbiol. 9:1965 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Food Authority (2009). Microbiological Quality Guide for Ready-to-Eat Foods. A Guide to Interpreting Microbiological Results [S/OL]. [2017-01-20]. NSW/FA/CP028/0906. Newington, CT: New South Wales Food Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Olaimat A. N., Holley R. A. (2012). Factors influencing the microbial safety of fresh produce: a review. Food Microbiol. 32 1–19. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltuszak-Walczak E., Walczak P. (2013). PCR detection of cytK gene in Bacillus cereus group strains isolated from food samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 95 295–301. 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osimani A., Aquilanti L., Clementi F. (2018). Bacillus cereus foodborne outbreaks in mass catering. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 72 145–153. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.01.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouoba L. I., Thorsen L., Varnam A. H. (2008). Enterotoxins and emetic toxins production by Bacillus cereus and other species of Bacillus isolated from Soumbala and Bikalga, African alkaline fermented food condiments. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124 224–230. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Kwarteng J., Wuni A., Akabanda F., Tano-Debrah K., Jespersen L. (2017). Prevalence, virulence factor genes and antibiotic resistance of Bacillus cereus sensu lato isolated from dairy farms and traditional dairy products. BMC Microbiol. 17:65. 10.1186/s12866-017-0975-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. M., Jeong M., Park K. J., Koo M. (2018). Prevalence, enterotoxin genes, and antibiotic resistance of Bacillus cereus isolated from raw vegetables in Korea. J. Food Prot. 81 1590–1597. 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-18-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. B., Kim J. B., Shin S. W., Kim J. C., Cho S. H., Lee B. K., et al. (2009). Prevalence, genetic diversity, and antibiotic susceptibility of Bacillus cereus strains isolated from rice and cereals collected in Korea. J. Food Prot. 72 612–617. 10.1089/cmb.2008.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal N., Pan H., Liao X., Zhang X., Li X., Fang W., et al. (2018). A meta-analysis of major foodborne pathogens in Chinese food commodities between 2006 and 2016. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 15 187–197. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippon A., Dusart J., Joris B., Frere J. M. (1998). The diversity, structure and regulation of beta-lactamases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 54 341–346. 10.1007/s000180050161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posfay-Barbe K., Schrenzel J., Studer R., Korff C., Belli D., Parvex P., et al. (2008). Food poisoning as a cause of acute liver failure. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 27 846–847. 10.1097/inf.0b013e318170f2ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic A., Uyttendaele M., Courtens T., Heyndrickx M., Debevere J. (2006). Prevalence and characterisation of Bacillus cereus in vacuum packed potato puree. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 41 878–884. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.01129.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramarao N., Belotti L., Deboscker S., Ennahar-Vuillemin M., Launay J. D., Lavigne T., et al. (2014). Two unrelated episodes of Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am. J. Infect. Control 42 694–695. 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Gonçalves B., Francisco A. P., Vaz C., Ramirez M., Carriço J. A. (2016). PHYLOViZ Online: web-based tool for visualization, phylogenetic inference, analysis and sharing of minimum spanning trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W246–W251. 10.1093/nar/gkw359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishi E., Rishi P., Sengupta S., Jambulingam M., Madhavan H. N., Gopal L., et al. (2013). Acute postoperative Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis mimicking toxic anterior segment syndrome. Ophthalmology 120 181–185. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen R., Svensson B., Andersson M. A., Christiansson A., Salkinoja-Salonen M. (2010). Persistence strategies of Bacillus cereus spores isolated from dairy silo tanks. Food Microbiol. 27 347–355. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2010). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twentieth Informational Supplement. Approved Standard-M100-S20. Wayne, PA: The clinical and laboratory standards institute. [Google Scholar]

- The Hygiene Ministry of China (2010a). National Food Safety Standard. Food Microbiological Examination: Bacillus cereus Test. Beijing: The Hygiene Ministry of China. [Google Scholar]

- The Hygiene Ministry of China (2010b). National Food Safety Standard. Food Microbiological Examination: General Guidelines. Beijing: The Hygiene Ministry of China. [Google Scholar]

- Torkar K. G., Bedenić B. (2018). Antimicrobial susceptibility and characterization of metallo-β-lactamases, extended-spectrum β-lactamases, and carbapenemases of Bacillus cereus isolates. Microb. Pathog. 118 140–145. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero M., Hernandez-Herrero L. A., Fernandez P. S., Salmeron M. C. (2002). Characterization of Bacillus cereus isolates from fresh vegetables and refrigerated minimally processed foods by biochemical and physiological tests. Food Microbiol. 19 491–499. 10.1006/yfmic.507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Duan H., Zhang W., Li J. W. (2013). Analysis of bacterial foodborne disease outbreaks in China between 1994 and 2005. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51 8–13. 10.1111/j.1574-695x.2007.00305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003). Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Around the World. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/fruit/en (accessed August 6, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yu X., Zhan L., Chen J., Zhang Y., Zhang J., et al. (2017). Multilocus sequence type profiles of Bacillus cereus isolates from infant formula in China. Food Microbiol. 62 46–50. 10.1016/j.fm.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sampling cities where the vegetables were collected.

Prevalence of virulence genes in B. cereus isolated from vegetables in China.

Results of antimicrobial resistance test for B. cereus isolates in the study.