The human cytomegalovirus is a highly prevalent pathogen that can cause severe disease in immunocompromised hosts. Currently used drugs successfully target the viral replication within the host cell, but their use is restricted due to side effects and the development of resistance. An alternative approach is the inhibition of virus entry, for which understanding the details of the initial virus-cell interaction is desirable. As binding of the viral gH/gL/gO complex to the cellular PDGFRα drives infection of fibroblasts, this is a potential target for inhibition of infection. Our mutational mapping approach suggests the N terminus as the receptor binding portion of the protein. The respective mutants were partially resistant to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc but also attenuated for infection of fibroblasts, indicating that such mutations have little if any benefit for the virus. These findings highlight the potential of targeting the interaction of gH/gL/gO with PDGFRα for therapeutic inhibition of HCMV.

KEYWORDS: cytomegalovirus, glycoproteins, receptors, virus entry

ABSTRACT

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) glycoprotein complex gH/gL/gO is required for the infection of cells by cell-free virions. It was recently shown that entry into fibroblasts depends on the interaction of gO with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα). This interaction can be blocked with soluble PDGFRα-Fc, which binds to HCMV virions and inhibits entry. The aim of this study was to identify parts of gO that contribute to PDGFRα binding. In a systematic mutational approach, we targeted potential interaction sites by exchanging conserved clusters of charged amino acids of gO with alanines. To screen for impaired interaction with PDGFRα, virus mutants were tested for sensitivity to inhibition by soluble PDGFRα-Fc. Two mutants with mutations within the N terminus of gO (amino acids 56 to 61 and 117 to 121) were partially resistant to neutralization. To validate whether these mutations impair interaction with PDGFRα-Fc, we compared binding of PDGFRα-Fc to mutant and wild-type virions via quantitative immunofluorescence analysis. PDGFRα-Fc staining intensities were reduced by 30% to 60% with mutant virus particles compared to wild-type particles. In concordance with the reduced binding to the soluble receptor, virus penetration into fibroblasts, which relies on binding to the cellular PDGFRα, was also reduced. In contrast, PDGFRα-independent penetration into endothelial cells was unaltered, demonstrating that the phenotypes of the gO mutant viruses were specific for the interaction with PDGFRα. In conclusion, the mutational screening of gO revealed that the N terminus of gO contributes to efficient spread in fibroblasts by promoting the interaction of virions with its cellular receptor.

IMPORTANCE The human cytomegalovirus is a highly prevalent pathogen that can cause severe disease in immunocompromised hosts. Currently used drugs successfully target the viral replication within the host cell, but their use is restricted due to side effects and the development of resistance. An alternative approach is the inhibition of virus entry, for which understanding the details of the initial virus-cell interaction is desirable. As binding of the viral gH/gL/gO complex to the cellular PDGFRα drives infection of fibroblasts, this is a potential target for inhibition of infection. Our mutational mapping approach suggests the N terminus as the receptor binding portion of the protein. The respective mutants were partially resistant to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc but also attenuated for infection of fibroblasts, indicating that such mutations have little if any benefit for the virus. These findings highlight the potential of targeting the interaction of gH/gL/gO with PDGFRα for therapeutic inhibition of HCMV.

INTRODUCTION

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a widely distributed pathogen posing a major health threat for those with insufficient immune protection, such as fetuses in utero or transplant recipients. HCMV can infect most organs and cell types and thus causes a variety of diseases (1, 2). Antivirals such as ganciclovir, cidofovir, and foscarnet are frequently used to treat or prevent HCMV disease in transplant recipients and AIDS patients. However, their use is limited due to adverse effects such as myelosuppression and nephrotoxicity (3–5). For the moment, these limitations can be overcome using the novel terminase inhibitor letermovir, yet this therapeutic also is associated with the rapid development of resistance (6–9). Furthermore, prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus disease is a still unsolved problem (10). Therefore, the development of alternative anti-HCMV strategies is important. One approach is the inhibition of the first step of HCMV infection, the entry into host cells. For entry into different target cells, HCMV uses two distinct gH/gL complexes. A trimeric complex of gH, gL, and gO is sufficient for infection of fibroblasts and necessary for infection of endothelial and epithelial cells. Additionally, infection of these cell types requires a pentameric complex of gH, gL, pUL128, pUL130, and pUL131A (11–15). These dependencies were demonstrated by analysis of viruses lacking one or the other complex. The infectivity of gO-null viruses, devoid of the trimeric complex, was strongly reduced in all cell types tested. In contrast, viruses lacking the pentamer can still infect fibroblasts efficiently but are strongly attenuated in endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and myeloid cells (11, 12, 15–19). A model has been proposed in which the two gH/gL complexes bind to specific receptors on the host cells and this interaction triggers fusion via gB (1, 20). Expression of the pentameric complex and addition of soluble pentameric complex were shown to inhibit HCMV infection in endothelial cell cultures, suggesting that this complex interacts with a receptor on this cell type (21–25). Recent evidence suggests that this receptor could be neuropilin 2 (26). On fibroblasts the trimeric complex is sufficient for both receptor interaction and fusion triggering (27–29). It has been proven that the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) serves as an entry receptor for HCMV on fibroblasts (22, 28, 30–32). While gB was initially suggested as the receptor binding envelope protein (30), more recent data, including electron microscopy, coimmunoprecipitation, and analysis of binding to gO-null virus particles, identified gH/gL/gO and more specifically gO as the interaction partner of PDGFRα (22, 28, 31). PDGFRα is strongly expressed on fibroblasts but not on endothelial cells and at only very low levels on epithelial cells (see, e.g., GEO Data Set GDS1402) (22, 28, 31, 33). The finding that blocking of the trimer by soluble PDGFRα-Fc potently inhibits HCMV infection irrespective of the cell type (31) is concordant with the notion that the trimer contributes to entry into endothelial cells, albeit not via receptor binding. Consequently, the mode of action of PDGFRα-Fc differed between these cell types, with adsorption being inhibited in both cell types while penetration was affected specifically in fibroblasts (31). Notably, PDGFRα-Fc inhibits HCMV infection in different cell types with similar efficiencies, while monoclonal antibodies usually inhibit infection of fibroblasts 5- to 10-fold less efficiently than infection of endothelial or epithelial cells (34–36). In line with that, the vast majority of human sera have a much higher neutralizing capacity for endothelial and epithelial cells than for fibroblasts (35, 37–39). This is most likely explained by the observation that human serum contains potent neutralizing antibodies against the accessory proteins of the pentamer (24, 40), whereas neutralizing antibodies against gO are rare. Until now, only one study has described the identification of human antibodies against gO (41). This could be explained by the special characteristics of glycoprotein O: it is highly polymorphic, with up to 40% variance between the genotypes, and is strongly glycosylated; both features can prevent antibody recognition (42–46). Identification of functional and perhaps vulnerable sites within gO might provide a basis for the future development of antiviral strategies targeting this protein.

As a starting point to understand the interaction of gO with PDGFRα, which is a key factor for fibroblast infection, this project now aimed at identification of the receptor binding site within gO that drives infection of fibroblasts. By charge cluster-to-alanine (ccta) mapping, two mutations in the N terminus of gO that caused partial resistance to inhibition by and reduced binding to PDGFRα-Fc were identified. The same virus mutants were also impaired for penetration into fibroblasts, indicating that mutations that induce resistance to PDGFRα-Fc also attenuate the virus.

(This work was previously published as part of Cora Stegmann's dissertation [47].)

RESULTS

The majority of the ccta mutants are moderately attenuated for spread in fibroblasts.

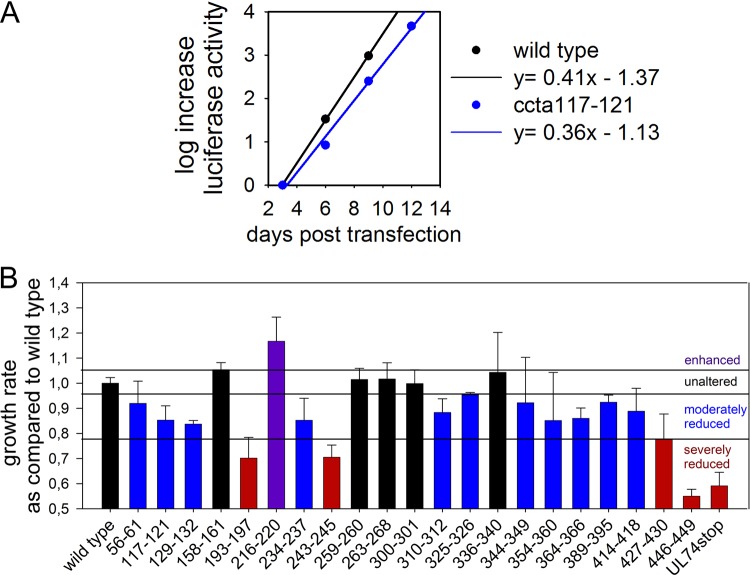

To determine which parts of gO are involved in binding to PDGFRα, a systematic mutational screening of HCMV gO was performed, based on a “charge cluster-to-alanine” (ccta) approach. As charged amino acids are often located at the surfaces of proteins, replacing them by small, neutral alanines is likely to weaken charge interactions without disrupting the protein’s conformation (48). In this study, a charge cluster was defined as a part of the protein in which at least 2 out of 5 amino acids (aa) are charged. As binding to PDGFRα is conserved among different HCMV strains (22, 31, 32), the study was focused on conserved amino acids. In total, 21 ccta mutants were generated (Fig. 1). All mutations were introduced into TB40-BAC4-IE-GLuc, which expresses the luciferase of Gaussia princeps (GLuc) under the control of the major immediate early (IE) promoter, thereby allowing detection of infection directly in cell culture supernatants without cell lysis or fixation (49). As reduced receptor binding is expected to impair the efficiency of viral spread in fibroblasts, mutant viruses were screened for spreading deficiencies in fibroblasts immediately after reconstitution by monitoring GLuc expression (49). Mutated viral genomes were transfected into human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), and samples of the supernatants were taken every 3 days starting from day 2 after transfection. The GLuc activity was measured and plotted against the time posttransfection to calculate the growth rate of the virus by linear regression, as exemplified in Fig. 2A. Using this method, each mutation was tested three times, and the growth rates were normalized to those of the wild type in the respective experiment (Fig. 2B). Of 21 virus mutants, only one showed an increased viral fitness (increased by >2 standard errors of the mean [SEM]), five mutants resembled the wild type (difference of <2 SEM), the majority (11 mutants) were moderately attenuated (reduced by 2 to 10 SEM), and four mutants resembled a complete gO-null phenotype (reduced by >10 SEM). Such a severe attenuation can be indicative of impaired formation of the trimeric complex (50), while particularly the moderately attenuated virus mutants were promising candidates for potential receptor binding site mutations.

FIG 1.

Charge cluster-to-alanine scanning of pUL74. A charge cluster was defined as two or more charged amino acids within a group of five amino acids. A gray background indicates conservation among various HCMV strains. Purple amino acids are negatively charged, and blue amino acids are positively charged. The boxes indicate peptide sites at which charged amino acids were exchanged with alanines.

FIG 2.

Spread of charge cluster-to-alanine mutants in fibroblasts. Mutated viral genomes based on TB40-BAC4-IE-GLuc were transfected into fibroblasts, and samples of the GLuc-containing supernatants were drawn every 3 days. GLuc activity was measured after the last sample was taken. Linear regression of the increase of GLuc activity over time allowed determination of the growth rate of the respective virus. (A) One example of the calculation by linear regression; (B) mean growth rates of all mutant viruses in three experiments relative to the growth rate of wild-type virus in the respective experiment. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. The phenotypes of the mutants were defined according to their growth rates in comparison with that of the wild type (far left) as follows: unaltered (black; difference of <2 SEM), moderately impaired (blue; reduced by 2 to 10 SEM), severely impaired (red; reduced by >10 SEM), or enhanced (purple; increased by >2 SEM).

Mutation of aa 56 to 61 and 117 to 121 reduces the sensitivity to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc.

To test whether some of the ccta mutants were impaired in binding to PDGFRα, a neutralization assay with soluble PDGFRα-Fc was performed. Soluble PDGFRα-Fc inhibits infection at a half-maximal concentration (EC50) of about 20 ng/ml (31). Charge cluster-to-alanine mutations within the PDGFRα binding site of gO are expected to weaken the binding of soluble PDGFRα-Fc and thereby decrease sensitivity to inhibition, which would translate into an increased EC50. To test for this, infectious supernatants were diluted to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 or were used at the maximal achievable MOI if the MOI of undiluted supernatant was <1. With the severely attenuated virus mutants (ccta193–197, ccta243–245, ccta427–430, and ccta446–449), the maximal MOI was below 0.1, and this group was hence excluded because meaningful dose-response curves could not be generated. Virus preparations of the remaining mutants were mixed with PDGFRα-Fc at concentrations of 3 to 200 ng/ml, and binding of PDGFRα-Fc to virus particles was allowed for 2 h at 37°C. The mixtures were then added to HFFs 2 h before the medium was exchanged. One day later, the cells were fixed and stained for the viral IE antigens to determine the percentage of infected cells. For most of the analyzed virus mutants, the EC50 for inhibition was between 12 and 25 ng/ml, and infection was almost completely prevented at 100 ng/ml PDGFRα-Fc, thus resembling the results for wild-type virus (Fig. 3). Only the two viruses with mutations at positions 56 to 61 (KLEILK → ALAILA) and 117 to 121 (RKPAK → AAPAA) retained some infectivity even at 200 ng/ml, and the EC50s for inhibition were increased from 18 ng/ml for the wild-type virus to 46 and 62 ng/ml, respectively. This result demonstrated that the two mutants ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 are partially resistant to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc, indicating impaired binding of the soluble receptor.

FIG 3.

Mutations of aa 56 to 61 and 117 to 121 confer resistance to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc. Virus stocks were preincubated with various concentrations (3 to 200 ng/ml) of PDGFRα-Fc for 2 h at 37°C before infection of fibroblasts. The inhibitory effect of PDGFRα-Fc on the different virus mutants was assessed by the visualization of infected cells via indirect immunofluorescence against the viral IE antigens at 1 day postinfection. (A) Dose-response curves normalized to untreated control. Each curve represents mean values from 3 to 4 independent experiments. (B) In a total of 4 experiments, the EC50 of PDGFRα for inhibition of mutants was compared to that for wild-type virus. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. The wild type is shown in black, ccta56–61 in turquois, and ccta117–121 in blue. *, P < 0.05.

Binding of PDGFRα-Fc is reduced upon mutation of aa 56 to 61 and 117 to 121.

To test whether the reduced susceptibility to inhibition by PDGFRα was actually due to impaired binding of the receptor-Fc molecule, virus particles were stained with PDGFRα-Fc and staining intensities were compared to those for wild-type particles. First, freshly produced virus particles were mixed with PDGFRα-Fc and binding was allowed for 2 h at 37°C. The virus particles were then adsorbed to HFFs for 90 min on ice, using unspecific attachment to, e.g., heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the surface of HFFs as a tool to immobilize the virions for further analysis. After fixation, all virus particles were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence for the viral capsid-associated protein pp150. Bound PDGFRα-Fc was visualized directly with an anti-human antibody (Fig. 4A). For quantification, virus particles were chosen according to their pp150 signal, and the intensity of the PDGFRα-Fc staining of each individual particle was then measured. The experiment was performed with 0, 20, 100, and 500 ng/ml of PDGFRα-Fc, and the signal intensities of 100 particles per condition were determined. On average, PDGFRα-Fc bound less efficiently to mutant virus particles than to wild-type particles. The difference was more pronounced with higher PDGFRα-Fc concentrations. At the highest concentration, PDGFRα-Fc bound 30% less efficiently to ccta56–61 virus particles and 50% less efficiently to ccta117–121 particles, demonstrating that both mutations indeed reduce binding of PDGFRα-Fc to gO (Fig. 4B). To test whether the reduced binding of PDGFRα-Fc is specific for the two N-terminal mutations, we repeated the experiment with virus particles of ccta414–418, whose growth kinetics resembled those of ccta117–121 in the initial screen but which did not show reduced susceptibility to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc, indicating unchanged binding by the soluble receptor. As expected, this virus mutant was bound by PDGFRα-Fc with an efficiency similar to that for the wild type, while signal intensities measured for the negative control UL74stop did not exceed the background level (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that the reduction in signal intensities observed with ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 is specifically caused by reduced binding of PDGFRα-Fc.

FIG 4.

PDGFRα-Fc binds ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 virus particles less efficiently. Freshly produced wild-type and mutant virus particles were preincubated with 20, 100, or 500 ng/ml PDGFRα-Fc for 2 h. To allow for easy visualization, the virus particles were attached to fibroblasts on ice for 90 min before fixation with 80% acetone. Virus particles were indirectly stained with a mouse anti-pp150 antibody and rabbit anti-mouse Cy3. Bound PDGFRα-Fc was detected using Alexa488-labeled goat anti-human-Ig antibodies. (A) Representative examples of virus particles treated with 500 ng/ml of PDGFRα-Fc. (B) Mean particle intensities of 100 virus particles per condition for the different viruses. Particles were chosen for quantification according to their pp150 signal and low background in the surrounding area. (C) To control for specificity of the observed reduction in PDGFRα-Fc binding, signal intensities of the two N-terminal ccta mutants, a mutant without a phenotype, and UL74stop were compared to those of the wild-type virus after treatment with 500 ng/ml of PDGFR. One hundred particles per condition were quantified. The signal intensities of the corresponding PDGFRα-Fc signals were measured using AxioVision software. Error bars indicate the standard error of the median. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with the wild type.

Although this result suggests that the two N-terminal peptide sites overlap the receptor binding site, reduced binding of the soluble receptor to mutant virus particles could in principle also be explained by impaired incorporation of the trimer, as binding of PDGFRα-Fc depends on the gH/gL/gO complex. Therefore, the gH/gL/gO trimer content in the mutant viruses was analyzed. Virions of wild-type virus, the two mutants that showed decreased susceptibility to PDGFRα-Fc (ccta56–61 and ccta117–121), two mutants with severely reduced growth in fibroblasts (ccta193–197, ccta427–430), and UL74stop (gO null) were gradient purified from infected cell culture supernatants and analyzed under nonreducing conditions by SDS-PAGE. The upper parts of the membranes were stained with an anti-gO antibody to detect the gH/gL/gO complex, and in the lower parts the major capsid protein (MCP) was detected to control for equal loading (Fig. 5A). No difference in the amount of the trimeric complex could be observed for the N-terminal mutations (ccta56–61 and ccta117–121), while the other mutations (ccta193–197 and ccta427–430) obviously decreased the incorporation of the trimeric complex. As immunoblot results tend to have a high interexperimental variance, which could mask mild differences, it was important to repeat the analysis of the ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 virions with two independent virus preparations and to use different amounts of the lysates to exclude saturation to validate that these mutations do not reduce the amount of trimer. Quantification of the signals was performed in a total of 6 experiments. For each experiment, the amount of gO signal was calculated relative to the corresponding MCP signal for the wild type and the two potential receptor binding site mutants (Fig. 5B). No significant difference in the relative amount of gH/gL/gO was detected between the mutant virions and the wild type, indicating that the mutations ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 do not impair complex formation but rather directly interfere with binding of PDGFRα-Fc.

FIG 5.

UL74ccta56–61 and UL74ccta117–121 virions contain normal amounts of the gH/gL/gO trimer. Gradient-purified virions were subjected to SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. The gH/gL/gO complex was detected using rabbit anti-gO polyclonal antibodies. As a reference, the lower parts of the membranes were stained with a murine monoclonal antibody recognizing the viral major capsid protein (MCP). For comparison, virus mutants with severely impaired spreading capacities were included. (A) Representative example of an immunoblot as used for quantification of signals. (B) Quantification of six experiments, as described in panel A, using various volumes of two biologically independent virion preparations of wild-type, ccta56–61, and ccta117–121 virions. The ratios of gH/gL/gO signals and MCP signals were normalized to the wild type in each experiment. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. (C) Virion preparations were titrated on fibroblasts to determine the number of infectious units per milliliter. The number of HCMV genomes in an aliquot of the virion preparation was determined. Shown are the mean infectivity/particle ratios determined for at least three independent virion preparations. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with the wild type.

aa 56 to 61 and 117 to 121 of gO are important for entry into fibroblasts.

The initial characterization of the ccta mutants in transfected cultures had already indicated that the mutations ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 moderately impaired virus growth in fibroblasts. The determination of the growth rate in fibroblasts integrates both cell-associated and cell-free spread, yet the trimer is involved mainly in cell-free spread. Therefore, the latter route of infection was analyzed in more detail. To directly quantify the capability of the ccta mutants for cell-free infection, the infectivity of virions was determined in relation to the number of particles (infectivity/particle ratio). Freshly produced virions were gradient purified, and one part was then titrated on HFFs to determine the number of infectious units while the other was used for DNA isolation and genome quantification. Four independent virion preparations were tested. For each virion preparation, the ratio of infectious units to genomes of the virus mutants was determined and compared to that for the wild type (Fig. 5C). As positive controls, the two mutations that reduced the incorporation of the trimeric complex were also tested. As expected, both control mutants showed a strongly reduced infectivity per particle (95%) compared to that of the wild type. A slight yet nonsignificant difference from the wild type was observed with ccta56–61, while the mutation of aa 117 to 121 significantly reduced the infectivity per particle ratio, by 50%. In absolute numbers, 420 virions in the inoculum were necessary for one infectious unit of the ccta117–121 mutant, whereas 230 virions were needed with wild-type virus. This demonstrates that the mutation ccta117–121 indeed impairs infectivity of the respective virus in fibroblasts.

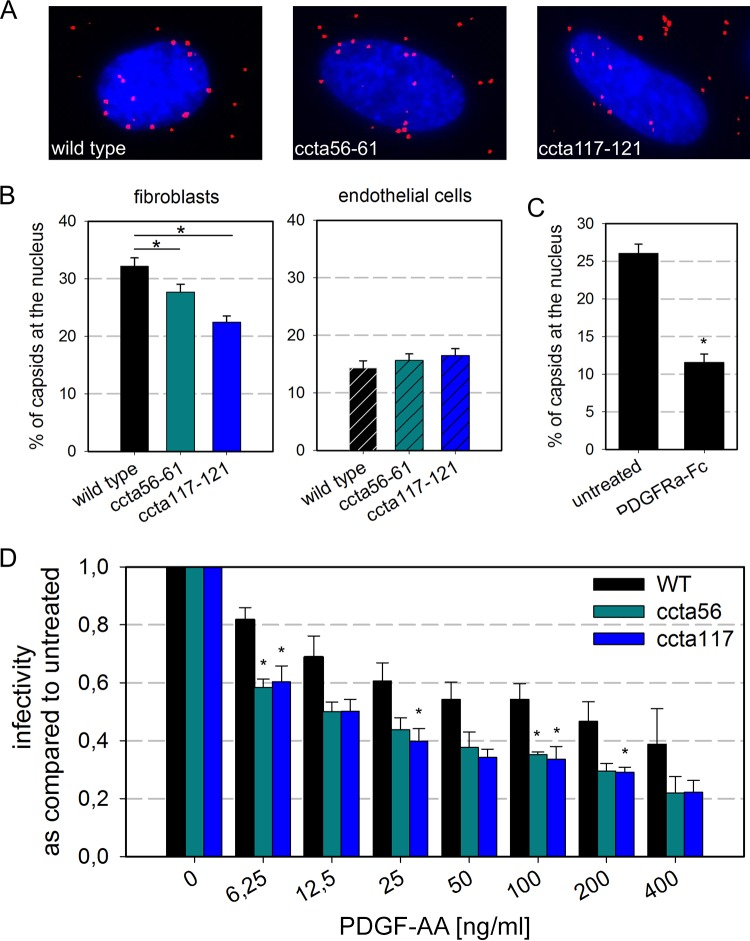

As we have shown previously that preincubation of virions with PDGFRα-Fc inhibits penetration into fibroblasts (31), we hypothesized that the reduced infectivity observed upon N-terminal mutation was at least partially due to reduced efficiency of penetration. As a surrogate marker for penetration of the virions into the cytoplasm, nuclear translocation of incoming virus particles was quantified. This approach also allowed us to achieve larger sample sizes, which might help to clarify whether the slight, nonsignificant reduction of the infectivity/particle ratio by mutation of aa 56 to 61 was due to a relevant effect on virus infectivity. To control for unspecific defects which are not due to reduced binding to PDGFRα, the experiments were performed not only in fibroblasts but also in endothelial cells, in which penetration is independent of PDGFRα (31, 32). Gradient-purified virions were first bound to the cells for 20 min at 37°C, and then the virus-containing medium was removed and penetration and translocation to the nucleus were allowed until 6 h postinfection, when the cells were fixed and stained for pp150 to visualize viral capsids (Fig. 6A). Two independent experiments were performed, and the number of total bound particles and the number of particles at the nucleus were determined in about 80 cells for each condition (Fig. 6B). While 32% of the wild-type virus particles were found at the nucleus, only about 22% of ccta117–121 particles had successfully translocated. The mutation of aa 56 to 61 caused a weaker yet significant reduction of the translocation efficiency to 28%. In contrast, no differences were observed for nuclear translocation in endothelial cells, supporting the idea that the effect in fibroblasts was due to reduced interaction with PDGFRα, which is not expressed on endothelial cells. As a positive control for the full effect of disrupted gO-PDGFRα interaction, wild-type virions were pretreated with 500 ng/ml PDGFRα-Fc and the nuclear translocation of pretreated virions was quantified. In this control experiment, the number of virus capsids at the nucleus was reduced by 50% (Fig. 6C), indicating that the ccta mutations had an intermediate effect on viral entry. These experiments demonstrated that the reduced infectivity of the ccta mutants is indeed due to reduced efficiency of penetration and that this reduced penetration is most likely caused by reduced binding to the cellular PDGFRα.

FIG 6.

The mutations ccta56–61 and ccta117–121 impair PDGFRα-mediated penetration into fibroblasts. (A) Representative images of the nuclear translocation assay (as described for panel B) in fibroblasts. (B) To determine the number of particles that successfully penetrated into the cells, gradient-purified virions of the wild type, ccta56–61 (turquoise), and ccta117–121 (blue) were incubated with fibroblasts or endothelial cells for 6 h. Fixed cultures were than stained for pp150 to visualize the particle distribution. The percentage of particles that have successfully translocated to the nucleus in a total of 80 cells per condition in 2 independent experiments is shown. (C) Gradient-purified wild-type virions were pretreated with 500 ng/ml PDGFRα-Fc for 2 h before incubation with fibroblasts. After 6 h, the efficiency of nuclear translocation was determined as for panel B. About 60 cells per condition were analyzed. (D) Fibroblasts were preincubated with PDGF-AA for 1 h on ice before infection. Infection with wild-type virus (black), ccta56–61 (turquoise), and ccta117–121 (blue) was performed for 2 h at 37°C in the presence of PDGF-AA. At 1day postinfection, the cells were fixed and stained for the viral immediate early antigens. Shown is the percentage of infected cells normalized to the untreated control (no PDGF-AA). All error bars indicate standard error of the mean determined from 3 experiments. *, P < 0.05.

It has been previously shown that PDGF-AA inhibits HCMV infection (28), most likely by occupying shared binding sites. This finding was utilized to further corroborate that the observed reductions in viral fitness are indeed due to reduced interaction with PDGFRα. HFFs were preincubated with various concentrations (6 to 400 ng/ml) of PDGF-AA on ice to allow binding but not internalization. Infection with wild-type, ccta56–61, and ccta117–121 virus preparations was performed in the presence of PDGF-AA for 2 h at 37°C. Infection efficiency was assessed by immunofluorescence staining for the viral IE antigens. As expected, pretreatment of cells with PDGF-AA reduced infection, and this competitive effect was significantly more pronounced with the mutant viruses than with the wild type (Fig. 6D). At the highest PDGF-AA concentration (400 ng/ml), infection by the mutant viruses was reduced about 50% compared to that by the wild type, demonstrating higher sensitivity to inhibition by PDGF-AA and in turn lower affinity for cellular PDGFRα. This result thereby further supported the conclusion that the two N-terminal charge clusters are involved in binding to PDGFRα.

The sites of interaction of gO with PDGFRα are conserved among HCMV strains.

The HCMV glycoprotein O is a highly polymorphic glycoprotein. Four genotypes of gO with a total of eight isoforms have been identified, with up to 50% difference on the amino acid level (44, 45, 50). Both potential receptor binding sites are located in the N terminus of gO (first 130 aa), which is the most polymorphic part of the protein. As the charge cluster-to-alanine screening was designed to focus on charge clusters that are conserved among different HCMV strains, these particular sites also are conserved. To test the hypothesis that the N-terminal charge clusters are important for binding to PDGFRα independent of the gO isoform, the respective mutations were introduced into two virus strains that encode isoforms of gO other than 1c, which is represented by TB40. AD169 was included because it is one of the most-studied HCMV strains and encodes gO isoform 1a. To also include a different genotype, a previously unpublished bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) of HCMV strain VHL/E was utilized, which represents genotype 2. In principle, both charge clusters that were shown to be important for binding to PDGFRα are conserved among these strains, either absolutely (aa 117 to 121) or with regard to the charge (aa 56 to 61) (Fig. 7A). To test whether the mutation of the N-terminal charge clusters is important for PDGFRα binding irrespective of the gO genotype, markerless mutagenesis was performed to introduce the respective mutations into AD169-pHB5 and VHL/E-BAC19. To corroborate the assumption that mutation of the two N-terminal charge clusters would lead to impaired binding to PDGFRα also in the context of AD169 and VHL/E, the sensitivity of the reconstituted mutant viruses to PDGFRα-Fc was tested. In all three virus strains (TB40, AD169, and VHL/E), mutation of the two conserved N-terminal charge clusters promoted partial resistance to PDGFRα (Fig. 7B). These experiments thereby demonstrate that the N terminus of gO is important for receptor binding, independent of the genotype.

FIG 7.

Mutation of N-terminal charge clusters also confers partial resistance in other HCMV strains. (A) Sequence alignment of three different HCMV strains, TB40, AD169, and VHL/E, shows that the putative receptor binding sites (blue boxes) are conserved. The charged amino acids that were exchanged with alanines are shown in blue (positively charged) and purple (negatively charged). Numbering is based on the TB40 sequence. (B) Stocks of TB40-BAC4, AD169-pHB5, and VHL/E-BAC19 and the respective ccta mutants were diluted to an MOI of 1 and preincubated with 3 to 200 ng/ml of PDGFRα-Fc for 2 h at 37°C before infection of fibroblasts. The inhibitory effect of PDGFRα-Fc on the viruses was assessed by the visualization of infected cells via indirect immunofluorescence against the viral IE antigens at 1 day postinfection. The infection rates were normalized to the respective untreated control. The gray lines indicate the EC50. Each curve represents mean values from 3 biologically independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We and others have demonstrated that HCMV enters fibroblasts by interaction of the viral gH/gL/gO complex with the cellular surface molecule PDGFRα. In this study, we show that the interaction of gO with PDGFRα is most probably mediated by the N terminus of gO. In particular, mutation of aa 117 to 121 interfered with binding of PDGFRα, thereby causing reduced sensitivity to inhibition by PDGFRα-Fc as well as reduced infectivity for fibroblasts.

PDGFRα has been identified as a receptor for HCMV (30), and multiple evidence demonstrated that gO is the viral interaction partner of PDGFRα (22, 28, 31). However, it was unknown which parts of gO are involved in receptor binding. To answer this question, we performed a charge cluster-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of gO. As a first step, the spread in fibroblasts was analyzed, and this screening demonstrated that a central part of the protein as well as the very C terminus are especially important for gO function. Our data indicate that the severe growth disadvantage caused by mutations in these parts of the protein was due to reduced formation of the trimeric complex. These results confirm and extend our previous finding that a conserved core domain of gO (from aa 181 to 254) is crucial for infectivity (50). While the majority of ccta mutations impaired the spread in fibroblasts to some extent, resistance to PDGFRα treatment was rare, which may indicate a certain degree of specificity of this phenotype. Out of 21 ccta mutations, only the two most N-terminal mutations reduced the sensitivity to inhibition by a soluble PDGFRα-Fc chimera. Not only partial resistance to PDGFRα-Fc but also reduced binding of PDGFRα to virions was found. Reduced binding occurred not only with the soluble dimeric receptor but also with cell-bound PDGFRα, as indicated by the reduced ability to compete with PDGF for binding to PDGFRα, decreased infectivity/particle ratios, and impaired penetration in fibroblasts. Interestingly, the two mutations differed in the extent of the effect on particle infectivity and penetration efficiency, with ccta117–121 causing a stronger reduction than ccta56–61. It is conceivably that the latter mutation affects binding to the soluble PDGFRα-Fc more than binding to the natural full-length protein on the cell surface, whereas the former has a similar effect on interaction with both molecules.

As resistance to PDGFRα-Fc, reduced binding of PDGFRα, and decreased infectivity/particle ratios could also be caused by smaller amounts of the trimeric gH/gL/gO complex in the envelopes of mutant virions (13, 28, 31), it was important to test whether incorporation of gH/gL/gO was unaltered by the respective mutations in gO. The amount of trimer was quantified by measurement of signal intensities of the trimer relative to pp150 in several experiments with various amounts of total virion lysates, thereby avoiding obscuration of differences by saturation. This analysis demonstrated that the wild-type and mutant viruses did not differ in gH/gL/gO incorporation. Although this approach does not exclude minor differences in the amount of trimer, it is highly unlikely that they would account for the 50% reduced binding of PDGFRα-Fc observed in our immunofluorescence analyses on the single-particle level. Furthermore, the finding that penetration into endothelial cells was unaffected by the mutations also argues against an unspecific effect of the mutations on trimer formation, as it has been demonstrated that the trimeric complex is necessary for penetration into all cell types (13). As the impact of mutations depends on the location of the mutated site within the protein, it would be interesting to pinpoint these sites within the tertiary structure of the protein. However, only limited information is available, because the crystal structure of gO has not been solved. Structure prediction (by I-TASSER [51]) suggests that gO is a rather globular protein, which is in line with the results obtained by cryoelectron microscopy of the trimeric complex (22, 52). Prediction of surface exposure for globular proteins (53) suggests that the two putative receptor binding sites are most likely located at the protein surface. In addition, five other sites within gO scored similarly high, of which we have previously identified two (aa 245 to 271 and aa 340 to 348) to be especially important for gO function (50), thereby increasing confidence regarding this prediction. Amino acids that are located to the surface of a protein are assumed to have a lower impact on overall protein structure and are more likely to be involved in protein-protein interactions. Therefore, the prediction that the two N-terminal charge clusters are located at the surface indirectly argues against unspecific effects on protein folding and supports the assumption of a direct involvement in receptor binding. The presumable surface localization together with the above-described experimental evidence on the sustained infectivity for PDGFRα-negative cells and the reduced binding by PDGFRα-Fc led us to the conclusion that mutation of the two identified N-terminal charge clusters interferes directly with binding of PDGFRα.

Concerning the question of why both mutants only partially reduced sensitivity to PDGFRα-Fc, several explanations are possible. On one hand, the charged amino acids that remained intact in each of the mutants might rescue partial binding of the receptor. On the other hand, receptor binding is most likely driven not only by interaction of these charged amino acids with complementary structures on PDGFRα. The binding of PDGFRβ to PDGF-BB is mediated by hydrophobic interactions (54), and similar mechanisms could also contribute to binding of PDGFRα to gH/gL/gO. Preincubation of cells with PDGFs inhibits infection, indicating that gO binds to the same or adjacent structures on PDGFRα (28, 30). To date it is still unclear how the interaction of gO with PDGFRα mediates penetration into fibroblasts. Initial studies have suggested that PDGFRα signaling might play a role, yet this has been challenged by the findings that the cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain of PDGFRα is not required for promoting HCMV entry and that HCMV binding does not induce phosphorylation in the absence of other stimulants (28, 30). Therefore, one potential mechanism could be that the binding to PDGFRα mediates close contact of the membranes and thus causes a conformational change that would trigger gB to exert fusion. To understand the interplay between the receptor and the trimeric complex, structural information on gO and PDGFRα would be desirable. For the validation of structural predictions or crystallographic measures, information about the location of the interaction between gO and PDGFRα might be valuable.

Our data strongly suggest that the N terminus of gO is the receptor binding domain of the protein. Notably, the N terminus of gO (the first 150 aa) is the most polymorphic part of the protein and shows signs of positive selection (45). It should be noted in this context that phenotypical analysis of various HCMV isolates has demonstrated that gO genotypes are stable, meaning that this positive selection is not due to selective pressure that occurs readily upon antibody response (45, 55). Nonetheless, this high variability in the N terminus might explain why a recent report about a neutralizing antibody directed against gO showed EC50s that were more than 1 log different for the inhibition of two different virus strains (22). Based on this observation, it is tempting to speculate that the high divergence between different gO genotypes could allow for superinfection of hosts with preexisting immunity. This hypothesis, however, needs validation by genomic analysis of different strains in superinfection or systematic analysis of different gO genotypes regarding neutralization. In contrast to the gO antibody, soluble PDGFRα-Fc inhibits all gO genotypes similarly efficiently, most likely because all HCMV strains depend on interaction with PDGFRα for infection of fibroblasts (31). In support of this assumption, we could demonstrate that both N-terminal charge cluster mutations also reduced the inhibitory capacity of PDGFRα in the context of other gO isoforms. PDGFRα-Fc not only is effective against different virus strains but also is very promising as an alternative to anti-gO antibodies, as mutations that impair the binding of the soluble receptor would most likely also reduce binding to the cellular receptor, thereby reducing infectivity. This assumption is supported by our finding that both mutations conferring resistance also reduced penetration into fibroblasts. Although the role of fibroblasts in HCMV pathogenesis within the host is not fully resolved, fibroblasts are a predominant target cell of HCMV in various organ tissues and were suggested as reservoirs for virus dissemination (1, 56, 57). In the murine CMV model, it was demonstrated that the gH/gL/gO complex is important for transmission of the virus to new hosts as well as spread within the host (58, 59). This suggests that viruses that acquire resistance to PDGFRα-Fc due to reduced binding would most likely not prevail in the population. At what frequency and at what cost resistances against PDGFRα-Fc can be selected in vitro need to be investigated.

In conclusion, the mutational screening of gO revealed that the N terminus of gO is important for interaction with the cellular receptor PDGFRα. Mutations that induced resistance to PDGFRα-Fc also affected entry into fibroblasts, suggesting that such “escape” mutations would impair viral fitness to some extent. Together these findings highlight the potential of targeting the interaction of gH/gL/gO and PDGFRα for inhibition of HCMV at the entry level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing GlutaMAX (Gibco), 5% fetal bovine serum (PAN-Biotech), 100 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma), and 0.5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Life Technologies). For infection assays, cells were seeded on vessels coated with 0.1% gelatin 1 day prior to infection in MEM plus 5% serum and 100 μg/ml gentamicin (MEM5G). Conditionally immortalized human endothelial cells (HEC-LTTs) (60, 61) were propagated in endothelial growth medium (EGM) (BulletKit; Lonza) in the presence of 2 μg/ml doxycycline. For experiments, the cells were seeded in medium without doxycycline. Because of inhibitory concentrations of heparin in EGM, HEC-LTTs were preincubated for 30 min with MEM5G before infection.

The charge cluster-to-alanine screening was performed on the background of HCMV strain TB40-BAC4-IE-Gluc (37). TB40-BAC4-IE-GLuc-UL74stop carries two stop codons instead of M7 and K12 (50). Validation of the putative receptor interaction sites was performed on the background of AD169-derived BAC clone pHB5 (62) and a novel, previously unpublished BAC construct of the highly endotheliotropic strain VHL/E (63). The recombinant VHL/E-BAC19 construct was generated by homologous recombination in HFFs using the vector plasmid pEB1097 as described previously (64). A single clone was chosen according to the prototype orientation of the genome and was transferred into bacterial strain GS1783 (65) for further mutagenesis.

All virus mutants were generated by markerless mutagenesis (65) and the integrity of the mutated genomes was checked by restriction fragment length analysis (RFLA) using enzymes BamHI and EcoRI. Viruses were reconstituted in HFFs by transfection of isolated BAC DNA with K2 transfection reagents (Biontex). UL74 was sequenced in all reconstituted viruses after DNA isolation from supernatants of infected cell cultures (DNeasy blood and tissue kit; Qiagen). For each mutation, two different clones were reconstituted and analyzed. For the mutations of aa 129 to 132 and aa 234 to 237, one of the two virus clones carried an additional mutation, and therefore only one clone was analyzed.

Characterization of virus growth directly after reconstitution.

HFFs were transfected with DNA of TB40-BAC4-IE-GLuc-derived mutants for reconstitution of virus. At 1 day posttransfection, cells were detached and reseeded in the same culture volume. At 6 days posttransfection, the cells were detached and reseeded on a larger growth area, with the culture volume being doubled. Afterwards, cells were detached and reseeded in the same volume every third day until the cultures displayed about 90% cytopathic effect. At that point, supernatants were harvested, centrifuged for 10 min at 3,790 × g to remove cells and large cell debris, and stored at −80°C for further experiments. Measurement of virus spread within the transfected cultures was performed as described previously (49). Briefly, aliquots of the GLuc-containing supernatants were harvested at 24 h after each reseeding and stored at −20°C until measurement. GLuc activity was assessed by addition of the substrate coelenterazine (PJK GmbH) and detection of luminescence in a plate reader (Hidex Chameleon). The log increase of luminescence was plotted against time, and linear transformation was used to determine the growth rate, which is given by the slope.

Recombinant proteins.

A PDGFRα-Fc expression plasmid was constructed by introducing aa 24 to 524 of the human PDGFRα (CD140a), corresponding to the extracellular domain, into the multiple-cloning site of pFuse-hIgG1-Fc2. The PDGFRα cDNA was amplified from pCMV/hygro PDGFRα using primers that introduce PciI and BamHI restriction sites. Double digestion of pFuse with NcoI and BglII followed by ligation resulted in pFuse-PDGFRα-hIgG1-Fc2. For expression of the Fc fusion protein, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected by lipofection (K2 kit; Biontex). At 1 day after transfection, the medium was exchanged with Pro293a serum-free medium (Lonza) supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine. The protein-containing supernatants were collected at 5 days posttransfection, and the Fc fusion protein was purified using protein A-Sepharose according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Quantification was performed using colorimetric bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). Quantity and purity were validated by SDS-PAGE and 2,2,2-trichloroethanol (TCE) staining of the protein.

PDGF-AA was purchased from R&D.

Inhibition assay.

To measure the sensitivity of viruses to PDGFRα-Fc, virus-containing supernatants were diluted to a maximal MOI of 1, mixed with various concentrations of PDGFRα-Fc (3 to 200 ng/ml), and preincubated for 2 h at 37°C. The mixtures were then added to HFFs seeded the day before on 96-well plates. Infection was allowed for 2 h at 37°C, and then the virus was removed and exchanged with MEM5G. At 1 day after infection, the cells were fixed with 80% acetone for later immunofluorescence analysis.

The ability of the virus mutants to outcompete PDGF-AA was analyzed as described previously (28). Several dilutions of PDGF-AA (12 to 800 ng/ml) were prepared and precooled on ice, and then PDGF-AA was incubated with the cells on ice for 1 h to allow binding of PDGF-AA to PDGFRα but not internalization of the receptor. The viruses were diluted to an MOI of 2 and mixed with equal volumes of PDGF-AA, resulting in a final MOI of 1 and PDGF-AA concentrations of 6 to 400 ng/ml. This mixture was then incubated with the cells for 2 h at 370C. After a medium exchange with MEM5G, the cells were further incubated overnight before fixation with acetone and immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence.

For quantification of infection, cells were stained with a primary antibody detecting the viral immediate early (IE) antigens (E13; Argene), followed by incubation with a secondary Cy3-goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 antibody (Jackson Immuno Research). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Three images were taken per condition, and the infection was calculated as the number of IE-positive nuclei divided by the total number of nuclei.

To quantify PDGFRα-Fc binding to virus particles, the particles were stained subsequently with a primary monoclonal antibody (MAb) detecting the capsid-associated tegument protein pp150 (MAb 36-14, generously provided by W. Britt [66]) and Cy3-goat anti-mouse Fab fragments (Jackson Immuno Research) as a secondary antibody. Bound PDGFRα-Fc was stained with a goat anti-human Alexa488-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen). Particles were chosen for quantification according to their pp150 signal, and then the gray values of corresponding Alexa488 signals were measured with AxioVision software (Zeiss).

Immunoblotting.

For protein analysis, virions were gradient purified as described previously (67, 68). Virions were lysed in 2× Laemmli buffer (4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 0.01% bromphenol blue, 125 mM Tris, pH 6.8) and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. Electrophoresis and transfer of the proteins were performed in Tris-glycine buffers as described previously (50). For the detection of the gH/gL/gO complex, a rabbit anti-gO antiserum (generously shared by B. Ryckman [42]) was used. MCP was detected with a mouse anti-MCP antibody (clone 28-4, kindly shared by W. Britt [69]). Horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies were obtained from Dako (P0260) or Santa Cruz (2055). All antibodies were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween (PBS-T) with 0.5% skim milk powder and incubated with the membranes for 2 h at room temperature. Detection of the chemiluminescence signal was performed with Super Signal West Dura extended-duration substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For quantification of chemiluminescence signals, FusionCapt Advance Solo 4 software was used. The signal intensity for the gH/gL/gO complex of each sample was compared to the corresponding MCP signal intensity.

Quantification of virion infectivity.

For retaining the infectivity of virions throughout gradient purification, the protocol was adjusted to keep the virions in MEM (70). Supernatants of infected HFFs were collected and centrifuged at 3,790 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. Then particles were pelleted at 70,000 × g for 70 min. Pellets were resuspended in MEM and carefully loaded onto glycerol-tartrate gradients (4 ml of 35% sodium tartrate in MEM and 5 ml of 15% sodium tartrate and 30% glycerol in MEM). Fractionation was done by centrifugation at 70,000 × g for 45 min. The virions were extracted with a syringe and diluted in MEM. The glycerol was washed out by another round of centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min. Virus pellets were immediately resuspended in MEM and added to HFFs in serial dilutions. At 1 day postinfection, the cells were fixed with 80% acetone and stained for viral IE antigens for visualization of infected cells. The infectivity was determined as infectious units per milliliter.

Genome quantification.

For the quantification of viral genomes, DNA was isolated from gradient-purified virions with a commercially available DNA extraction kit (DNeasy blood and tissue kit; Qiagen). DNA amplification was performed as described previously (71) using Brilliant II QPCR 2× Mastermix (Agilent). The primers and 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-conjugated probe bind to UL54. Detection was performed with Mx3005P (Agilent).

Nuclear translocation assay.

At 1 day prior to infection, cells were seeded on gelatin-coated 8-well μ-slides (Ibidi). The next day, freshly produced virions were gradient purified (see “Quantification of virion infectivity” above) and incubated with the cells for 6 h at 37°C. The cells were fixed with 80% acetone, and virus particles were subsequently stained with MAb 36-14 directed against pp150 (66) and Cy3-goat anti-mouse Fab fragments (Jackson Immuno Research). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Penetration was assessed by counting the number of total particles per cell and the number of particles localizing at the nucleus.

Similarly, to assess the effect of PDGFRα-Fc on the efficiency of nuclear translocation of virus particles, the gradient-purified virions were preincubated with 500 ng/ml PDGFRα-Fc for 2 h at 37°C before incubation with the cells for 6 h at 37°C followed by fixation and immunofluorescence staining of viral capsids.

Statistics.

Differences between wild-type and mutant viruses were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks and multiple comparisons versus the control group (Dunnett’s method). Only for the comparison of penetration efficiencies was Dunn’s post hoc test used due to differences in the number of cells that were analyzed. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05, as indicated by asterisks in all images. A lack of asterisks indicates a P value of >0.05.

Data availability.

The complete sequence of VHL/E-BAC19 is available at the NCBI GenBank under accession no. MK425187.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nene Ndukwe and Dagmar Stöhr for their technical assistance. We thank W. Britt and B. Ryckman for kindly providing antibodies.

This work was funded by the Wilhelm-Sander-Foundation (Projekt 2013.002.1 and 2013.002.2).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, or interpretation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler B, Sinzger C. 2013. Cytomegalovirus interstrain variance in cell type tropism, p 297–321. In Reddehase MM, Lemmermann NAW (ed), Cytomegaloviruses: from molecular pathogenesis to intervention. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boppana SB, Britt WJ. 2013. Synopsis of clinical aspects of human cytomegalovirus disease, p 1–25. In Reddehase MJ, Lemmermann NAW (ed), Cytomegaloviruses: from molecular pathogenesis to intervention. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razonable RR, Humar A. 2013. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 13:93–106. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodson EM, Ladhani M, Webster AC, Strippoli GF, Craig JC. 2013. Antiviral medications for preventing cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD003774. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003774.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bainbridge JW, Raina J, Shah SM, Ainsworth J, Pinching AJ. 1999. Ocular complications of intravenous cidofovir for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Eye 13:353–356. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marty FM, Ljungman P, Chemaly RF, Maertens J, Dadwal SS, Duarte RF, Haider S, Ullmann AJ, Katayama Y, Brown J, Mullane KM, Boeckh M, Blumberg EA, Einsele H, Snydman DR, Kanda Y, DiNubile MJ, Teal VL, Wan H, Murata Y, Kartsonis NA, Leavitt RY, Badshah C. 2017. Letermovir prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 377:2433–2444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lischka P, Michel D, Zimmermann H. 2016. Characterization of cytomegalovirus breakthrough events in a phase 2 prophylaxis trial of letermovir (AIC246, MK 8228). J Infect Dis 213:23–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong PP, Teiber D, Prokesch BC, Arasaratnam RJ, Peltz M, Drazner MH, Garg S. 2018. Letermovir successfully used for secondary prophylaxis in a heart transplant recipient with ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus syndrome (UL97 mutation). Transpl Infect Dis 20:e12965. doi: 10.1111/tid.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherrier L, Nasar A, Goodlet KJ, Nailor MD, Tokman S, Chou S. 2018. Emergence of letermovir resistance in a lung transplant recipient with ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Transplant 18:3060–3064. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawlinson WD, Boppana SB, Fowler KB, Kimberlin DW, Lazzarotto T, Alain S, Daly K, Doutré S, Gibson L, Giles ML, Greenlee J, Hamilton ST, Harrison GJ, Hui L, Jones CA, Palasanthiran P, Schleiss MR, Shand AW, van Zuylen WJ. 2017. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis 17:e177–e188. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang XJ, Adler B, Sampaio KL, Digel M, Jahn G, Ettischer N, Stierhof Y-D, Scrivano L, Koszinowski U, Mach M, Sinzger C. 2008. UL74 of human cytomegalovirus contributes to virus release by promoting secondary envelopment of virions. J Virol 82:2802–2812. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01550-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wille PT, Knoche AJ, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Johnson DC. 2010. A human cytomegalovirus gO-null mutant fails to incorporate gH/gL into the virion envelope and is unable to enter fibroblasts and epithelial and endothelial cells. J Virol 84:2585–2596. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02249-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou M, Lanchy J-M, Ryckman BJ. 2015. Human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/gO promotes the fusion step of entry into all cell types, whereas gH/gL/UL128-131 broadens virus tropism through a distinct mechanism. J Virol 89:8999–9009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01325-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Shenk T. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:18153–18158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn G, Revello MG, Patrone M, Percivalle E, Campanini G, Sarasini A, Wagner M, Gallina A, Milanesi G, Koszinowski U, Baldanti F, Gerna G. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J Virol 78:10023–10033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.10023-10033.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobom U, Brune W, Messerle M, Hahn G, Koszinowski UH. 2000. Fast screening procedures for random transposon libraries of cloned herpesvirus genomes: mutational analysis of human cytomegalovirus envelope glycoprotein genes. J Virol 74:7720–7729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.17.7720-7729.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn W, Chou C, Li H, Hai R, Patterson D, Stolc V, Zhu H, Liu F. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:14223–14228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334032100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerna G, Percivalle E, Lilleri D, Lozza L, Fornara C, Hahn G, Baldanti F, Revello MG. 2005. Dendritic-cell infection by human cytomegalovirus is restricted to strains carrying functional UL131-128 genes and mediates efficient viral antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. J Gen Virol 86:275–284. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler B, Scrivano L, Ruzcics Z, Rupp B, Sinzger C, Koszinowski U, Ulrich Koszinowski C. 2006. Role of human cytomegalovirus UL131A in cell type-specific virus entry and release. J Gen Virol 87:2451–2460. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanarsdall AL, Johnson DC. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus entry into cells. Curr Opin Virol 2:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanarsdall AL, Chase MC, Johnson DC. 2011. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein gO complexes with gH/gL, promoting interference with viral entry into human fibroblasts but not entry into epithelial cells. J Virol 85:11638–11645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05659-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabanova A, Marcandalli J, Zhou T, Bianchi S, Baxa U, Tsybovsky Y, Lilleri D, Silacci-Fregni C, Foglierini M, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Druz A, Zhang B, Geiger R, Pagani M, Sallusto F, Kwong PD, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Perez L. 2016. Platelet-derived growth factor-α receptor is the cellular receptor for human cytomegalovirus gHgLgO trimer. Nat Microbiol 1:16082. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryckman BJ, Chase MC, Johnson DC. 2008. HCMV gH/gL/UL128-131 interferes with virus entry into epithelial cells: evidence for cell type-specific receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:14118–14123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804365105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loughney JW, Rustandi RR, Wang D, Troutman MC, Dick LW, Li G, Liu Z, Li F, Freed DC, Price CE, Hoang VM, Culp TD, De Phillips PA, Fu TM, Ha S. 2015. Soluble human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/pUL128-131 pentameric complex, but not gH/gL, inhibits viral entry to epithelial cells and presents dominant native neutralizing epitopes. J Biol Chem 290:15985–15995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.652230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Jardetzky TS, Chin AL, Johnson DC, Vanarsdall AL. 2018. The human cytomegalovirus trimer and pentamer promote sequential steps in entry into epithelial and endothelial cells at cell surfaces and endosomes. J Virol 92:e01336-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01336-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Martin N, Marcandalli J, Huang CS, Arthur CP, Perotti M, Foglierini M, Ho H, Dosey AM, Shriver S, Payandeh J, Leitner A, Lanzavecchia A, Perez L, Ciferri C. 2018. An unbiased screen for human cytomegalovirus identifies neuropilin-2 as a central viral receptor. Cell 174:1158–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryckman BJ, Jarvis MA, Drummond DD, Nelson JA, Johnson DC. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells depends on genes UL128 to UL150 and occurs by endocytosis and low-pH fusion. J Virol 80:710–722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.710-722.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y, Prager A, Boos S, Resch M, Brizic I, Mach M, Wildner S, Scrivano L, Adler B. 2017. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complex gH/gL/gO uses PDGFR-α as a key for entry. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006281. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinzger C, Kahl M, Laib K, Klingel K, Rieger P, Plachter B, Jahn G. 2000. Tropism of human cytomegalovirus for endothelial cells is determined by a post-entry step dependent on efficient translocation to the nucleus. J Gen Virol 1249:41–3021. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-12-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soroceanu L, Akhavan A, Cobbs CS. 2008. Platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor activation is required for human cytomegalovirus infection. Nature 455:391–395. doi: 10.1038/nature07209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stegmann C, Hochdorfer D, Lieber D, Subramanian N, Stöhr D, Laib Sampaio K, Sinzger C. 2017. A derivative of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha binds to the trimer of human cytomegalovirus and inhibits entry into fibroblasts and endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006273. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu K, Oberstein A, Wang W, Shenk T. 2018. Role of PDGF receptor-alpha during human cytomegalovirus entry into fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E9889–E9898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806305115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanarsdall AL, Wisner TW, Lei H, Kazlauskas A, Johnson DC. 2012. PDGF receptor-α does not promote HCMV entry into epithelial and endothelial cells but increased quantities stimulate entry by an abnormal pathway. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002905. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida JH, Burgess T, Derby MA, Brown PA, Maia M, Deng R, Emu B, Feierbach B, Fouts AE, Liao XC, Tavel JA. 2015. Phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of RG7667, an anticytomegalovirus combination monoclonal antibody therapy, in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4919–4929. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00523-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed DC, Tang Q, Tang A, Li F, He X, Huang Z, Meng W, Xia L, Finnefrock AC, Durr E, Espeseth AS, Casimiro DR, Zhang N, Shiver JW, Wang D, An Z, Fu T-M. 2013. Pentameric complex of viral glycoprotein H is the primary target for potent neutralization by a human cytomegalovirus vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E4997–E5005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316517110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel HD, Nikitin P, Gesner T, Lin JJ, Barkan DT, Ciferri C, Carfi A, Akbarnejad Yazdi T, Skewes-Cox P, Wiedmann B, Jarousse N, Zhong W, Feire A, Hebner CM. 2016. In vitro characterization of human cytomegalovirus-targeting therapeutic monoclonal antibodies LJP538 and LJP539. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4961–4971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00382-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerna G, Sarasini A, Patrone M, Percivalle E, Fiorina L, Campanini G, Gallina A, Baldanti F, Revello MG. 2008. Human cytomegalovirus serum neutralizing antibodies block virus infection of endothelial/epithelial cells, but not fibroblasts, early during primary infection. J Gen Virol 89:853–865. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui X, Freed DC, Wang D, Qiu P, Li F, Fu T-M, Kauvar LM, McVoy MA. 2017. Impact of Antibodies and Strain Polymorphisms on Cytomegalovirus Entry and Spread in Fibroblasts and Epithelial Cells. J Virol 91:e01650-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01650-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falk JJ, Winkelmann M, Schrezenmeier H, Stöhr D, Sinzger C, Lotfi R. 2017. A two-step screening approach for the identification of blood donors with highly and broadly neutralizing capacities against human cytomegalovirus. Transfusion 57:412–422. doi: 10.1111/trf.13906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schampera MS, Arellano-Galindo J, Kagan KO, Adler SP, Jahn G, Hamprecht K. 2018. Role of pentamer complex-specific and IgG subclass 3 antibodies in HCMV hyperimmunoglobulin and standard intravenous IgG preparations. Med Microbiol Immunol 208:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s00430-018-0558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerna G, Percivalle E, Perez L, Lanzavecchia A, Lilleri D. 2016. Monoclonal antibodies to different components of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) pentamer gH/gL/pUL128L and trimer gH/gL/gO as well as antibodies elicited during primary HCMV infection prevent epithelial cell syncytium formation. J Virol 90:6216–6223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00121-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou M, Yu Q, Wechsler A, Ryckman BJ. 2013. Comparative analysis of gO isoforms reveals that strains of human cytomegalovirus differ in the ratio of gH/gL/gO and gH/gL/UL128-131 in the virion envelope. J Virol 87:9680–9690. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang XJ, Sampaio KL, Ettischer N, Stierhof YD, Jahn G, Kropff B, Mach M, Sinzger C. 2011. UL74 of human cytomegalovirus reduces the inhibitory effect of gH-specific and gB-specific antibodies. Arch Virol 156:2145–2155. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasmussen L, Geissler A, Cowan C, Chase A, Winters M. 2002. The genes encoding the gCIII complex of human cytomegalovirus exist in highly diverse combinations in clinical isolates. J Virol 76:10841–10848. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10841-10848.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattick C, Dewin D, Polley S, Sevilla-Reyes E, Pignatelli S, Rawlinson W, Wilkinson G, Dal Monte P, Gompels UA. 2004. Linkage of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein gO variant groups identified from worldwide clinical isolates with gN genotypes, implications for disease associations and evidence for N-terminal sites of positive selection. Virology 318:582–597. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huber MT, Compton T. 1999. Intracellular formation and processing of the heterotrimeric gH-gL-gO (gCIII) glycoprotein envelope complex of human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 73:3886–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stegmann C. 2017. Dissertation. University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Condit RC. 2007. Principles of virology, p 25–55. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falk JJ, Laib Sampaio K, Stegmann C, Lieber D, Kropff B, Mach M, Sinzger C. 2016. Generation of a Gaussia luciferase-expressing endotheliotropic cytomegalovirus for screening approaches and mutant analyses. J Virol Methods 235:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stegmann C, Abdellatif MEA, Laib Sampaio K, Walther P, Sinzger C. 2016. Importance of highly conserved peptide sites of HCMV gO for the formation of the gH/gL/gO complex. J Virol 91:e01339-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01339-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y. 2008. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciferri C, Chandramouli S, Donnarumma D, Nikitin PA, Cianfrocco MA, Gerrein R, Feire AL, Barnett SW, Lilja AE, Rappuoli R, Norais N, Settembre EC, Carfi A, Arvin AM, Cohen GH. 2015. Structural and biochemical studies of HCMV gH/gL/gO and pentamer reveal mutually exclusive cell entry complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1767–1772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424818112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janin J. 1979. Surface and inside volumes in globular proteins. Nature 277:491–492. doi: 10.1038/277491a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen P-H, Chen X, He X. 2013. Platelet-derived growth factors and their receptors: structural and functional perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834:2176–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanton R, Westmoreland D, Fox JD, Davison AJ, Wilkinson G. 2005. Stability of human cytomegalovirus genotypes in persistently infected renal transplant recipients. J Med Virol 75:42–46. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinzger C, Grefte A, Plachter B, Gouw ASH, The TH, Jahn G. 1995. Fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are major targets of human cytomegalovirus infection in lung and gastrointestinal tissues. J Gen Virol 76:741–750. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soland MA, Keyes LR, Bayne R, Moon J, Porada CD, St Jeor S, Almeida-Porada G. 2014. Perivascular stromal cells as a potential reservoir of human cytomegalovirus. Am J Transplant 14:820–830. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lemmermann NAW, Krmpotic A, Podlech J, Brizic I, Prager A, Adler H, Karbach A, Wu Y, Jonjic S, Reddehase MJ, Adler B. 2015. Non-redundant and redundant roles of cytomegalovirus gH/gL complexes in host organ entry and intra-tissue spread. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004640. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yunis J, Farrell HE, Bruce K, Lawler C, Wyer O, Davis-Poynter N, Brizic I, Jonjic S, Adler B, Stevenson PG. 7 November 2018. Murine cytomegalovirus glycoprotein O promotes epithelial cell infection in vivo. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01378-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.May T, Butueva M, Bantner S, Markusic D, Seppen J, MacLeod RA, Weich H, Hauser H, Wirth D. 2010. Synthetic gene regulation circuits for control of cell expansion. Tissue Eng Part A 16:441–452. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lieber D, Hochdorfer D, Stoehr D, Schubert A, Lotfi R, May T, Wirth D, Sinzger C. 2015. A permanently growing human endothelial cell line supports productive infection with human cytomegalovirus under conditional cell growth arrest. Biotechniques 59:127–136. doi: 10.2144/000114326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borst E-M, Hahn G, Koszinowski UH, Messerle M. 1999. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J Virol 73:8320–8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waldman WJ, Roberts WH, Davis DH, Williams MV, Sedmak DD, Stephens RE. 1991. Preservation of natural endothelial cytopathogenicity of cytomegalovirus by propagation in endothelial cells. Arch Virol 117:143–164. doi: 10.1007/BF01310761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sampaio KL, Weyell A, Subramanian N, Wu Z, Sinzger C. 2017. A TB40/E-derived human cytomegalovirus genome with an intact US-gene region and a self-excisable BAC cassette for immunological research. Biotechniques 63:205–214. doi: 10.2144/000114606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tischer KB, Smith GA, Osterrieder N. 2010. En passant mutagenesis: a two markerless red recombination system. Methods Mol Biol 634:421–430. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-652-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanchez V, Greis KD, Sztul E, Britt WJ. 2000. Accumulation of virion tegument and envelope proteins in a stable cytoplasmic compartment during human cytomegalovirus replication: characterization of a potential site of virus assembly. J Virol 74:975–986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.2.975-986.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talbot P, Almeida JD. 1977. Human cytomegalovirus: purification of enveloped virions and dense bodies. J Gen Virol 36:345–349. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-2-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haspot F, Lie Lavault A, Sinzger C, Sampaio KL, Stierhof Y-D, Pilet P, Line Bressolette-Bodin C, Halary F, Kremer EJ. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus entry into dendritic cells occurs via a macropinocytosis-like pathway in a pH-independent and cholesterol-dependent manner. PloS One 7:e34795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chee M, Rudolph SA, Plachter B, Barrell B, Jahn G. 1989. Identification of the major capsid protein gene of human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 63:1345–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Digel M. 2007. Mechanismus und genetische Grundlage der zellassoziierten Ausbreitung des humanen Cytomegalovirus in verschiedenen Zelltypen. Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sassenscheidt J, Rohayem J, Illmer T, Bandt D. 2006. Detection of betaherpesviruses in allogenic stem cell recipients by quantitative real-time PCR. J Virol Methods 138:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The complete sequence of VHL/E-BAC19 is available at the NCBI GenBank under accession no. MK425187.