HIV-1 fuses with cells when the gp41 subunit of Env refolds into a 6HB after binding to cellular receptors. Peptides corresponding to HR1 or HR2 interrupt gp41 refolding and inhibit HIV infection. Previously, we found that a CCR5 coreceptor-tropic HIV-1 acquired a key HR1 or HR2 resistance mutation to escape HR1 peptide inhibitors but only the key HR1 mutation to escape a trimer-stabilized HR1 peptide inhibitor. Here, we report that a CXCR4 coreceptor-tropic HIV-1 selected the same key HR1 or HR2 mutations to escape inhibition by the HR1 peptide but different combinations of HR1 and HR2 mutations to escape the trimer-stabilized HR1 peptide. All gp41 mutations enhance 6HB stability to outcompete inhibitors, but gp120 adaptive mutations differed between these R5 and X4 viruses, providing new insights into gp120-gp41 functional interactions affecting Env refolding during HIV entry.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, conformational changes, fusion, fusion inhibitor, gp41, resistance

ABSTRACT

Binding of the gp120 surface subunit of the envelope glycoprotein (Env) of HIV-1 to CD4 and chemokine receptors on target cells triggers refolding of the gp41 transmembrane subunit into a six-helix bundle (6HB) that promotes fusion between virus and host cell membranes. To elucidate details of Env entry and potential differences between viruses that use CXCR4 (X4) or CCR5 (R5) coreceptors, we generated viruses that are resistant to peptide fusion inhibitors corresponding to the first heptad repeat region (HR1) of gp41 that target fusion-intermediate conformations of Env. Previously we reported that an R5 virus selected two resistance pathways, each defined by an early gp41 resistance mutation in either HR1 or the second heptad repeat (HR2), to escape inhibition by an HR1 peptide, but preferentially selected the HR1 pathway to escape inhibition by a trimer-stabilized HR1 peptide. Here, we report that an X4 virus selected the same HR1 and HR2 resistance pathways as the R5 virus to escape inhibition by the HR1 peptide. However, in contrast to the R5 virus, the X4 virus selected a unique mutation in HR2 to escape inhibition by the trimer-stabilized peptide. Significantly, both of these X4 and R5 viruses acquired gp41 resistance mutations that improved the thermostability of the six-helix bundle, but they selected different gp120 adaptive mutations. These findings show that these X4 and R5 viruses use a similar resistance mechanism to escape from HR1 peptide inhibition but different gp120-gp41 interactions to regulate Env conformational changes.

IMPORTANCE HIV-1 fuses with cells when the gp41 subunit of Env refolds into a 6HB after binding to cellular receptors. Peptides corresponding to HR1 or HR2 interrupt gp41 refolding and inhibit HIV infection. Previously, we found that a CCR5 coreceptor-tropic HIV-1 acquired a key HR1 or HR2 resistance mutation to escape HR1 peptide inhibitors but only the key HR1 mutation to escape a trimer-stabilized HR1 peptide inhibitor. Here, we report that a CXCR4 coreceptor-tropic HIV-1 selected the same key HR1 or HR2 mutations to escape inhibition by the HR1 peptide but different combinations of HR1 and HR2 mutations to escape the trimer-stabilized HR1 peptide. All gp41 mutations enhance 6HB stability to outcompete inhibitors, but gp120 adaptive mutations differed between these R5 and X4 viruses, providing new insights into gp120-gp41 functional interactions affecting Env refolding during HIV entry.

INTRODUCTION

The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) assembles as a trimer of two noncovalently associated subunits, gp120 and gp41. Binding of the gp120 surface subunit to the CD4 receptor on host cells triggers the conformational changes in Env that facilitate gp120 binding to the CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptor. These conformational changes release the hydrophobic fusion peptide at the N terminus of the gp41 transmembrane subunit, allowing it to insert into the host cell membrane. While gp41 is embedded in host and viral membranes, the HR1 and HR2 regions refold into the more stable, six-helix bundle (6HB) conformation, consisting of an internal, trimeric HR1 coiled-coil core with three HR2 helices packed into the grooves of the coiled-coil core in an antiparallel manner. Formation of the 6HB draws the virus and cell membranes together, facilitating formation of a fusion pore that allows passage of the viral core to the host cell cytoplasm (1–4).

The entry process provides opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Peptides corresponding to HR1 and HR2 bind to gp41 to form an inhibitor-gp41, 6HB-like complex (inhibitor bundle) that interferes with formation of the gp41 6HB (endogenous bundle) in a dominant-negative manner (5). The HR2 peptide enfuvirtide (Fuzeon; corresponding to T20 or DP178 peptides) has been available for clinical use as an antiretroviral drug since 2003 (6). However, as is the case with other antiretroviral drugs, HIV can develop resistance to enfuvirtide.

HR1 peptides are not yet approved for clinical use, and information about their inhibitory and resistance mechanisms is limited. HR1 peptides are poorly soluble in aqueous buffers and exist in multiple oligomeric forms and aggregates (7), which complicates their clinical development and may explain their lower inhibitory potency compared to those of HR2 peptides. HR1 peptide monomers or dimers could bind to the gp41 HR1 to interrupt formation of the gp41 (endogenous) coiled coil, or HR1 peptide trimers could bind to the gp41 HR2 to interrupt formation of the endogenous 6HB (8–10). Restrained HR1 peptides with modifications that stabilize the trimeric, coiled-coil structure, such as IZN36 or IQN36, improve solubility and have inhibitory potency similar to that of HR2 peptides (11).

To investigate the mechanisms of HIV entry and resistance to HR1 peptides, we previously generated R5 viruses that are resistant to a trimer-stabilized (IZN36) or unrestrained (N36 or N44) HR1 peptide. Among sixteen independent resistance cultures with the JRCSF strain, two genetic pathways of resistance consistently emerged, defined by a glutamic acid-to-lysine substitution at either residue 560 (E560K; HXB2 gp160 numbering) in HR1 or residue 648 (E648K; HXB2 gp160 numbering) in HR2 (10, 12, 13). Resistance mutations to HR2 peptides have been widely reported and typically involve mutations in HR1 that directly impair peptide binding to Env and decrease stability of the 6HB (14–17). In contrast, we found that mutations conferring resistance to HR1 peptides stabilize the gp41 coiled-coil core and 6HB, demonstrating that there are distinct mechanisms of resistance to different inhibitors that target fusion-intermediate conformations of Env.

Here, using the LAI HIV-1 strain, we generated X4 viruses resistant to either the N36 or IZN36 peptide to discern how coreceptor use may affect selection of resistance and compensatory mutations. As seen for the R5 virus, the X4 virus selected either the E560K or E648K pathway for N36 resistance. However, in contrast to the R5 virus, the X4 virus selected an alternative HR2 pathway that involved an asparagine-to-lysine substitution at residue 637 (N637K) for IZN36 resistance, sometimes with an additional E560K mutation. Significantly, each of the gp41 resistance mutations increased thermostability of the LAI 6HB, suggesting a shared mechanism of HR1-peptide resistance for both X4 and R5 viruses. However, different gp120 adaptive or compensatory mutations emerged, revealing differences in functional interactions between gp41 and gp120 between these X4 and R5 viruses.

RESULTS

X4 HIV-1 selects three genetic pathways of resistance to HR1 peptide fusion inhibitors.

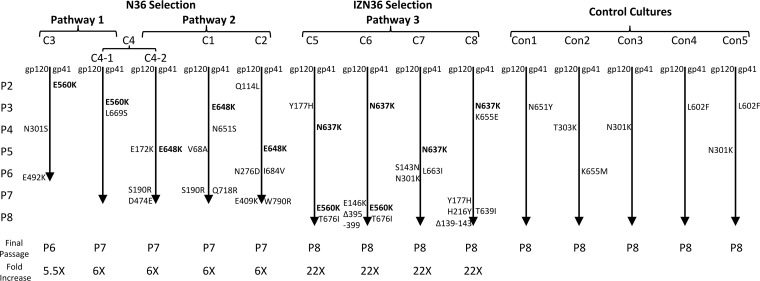

To gain insights into how the Env entry mechanism of an X4 HIV-1 might differ from that of an R5 HIV-1, we generated eight independent resistance cultures for the X4 HIV-1 LAI strain by selecting four cultures with the N36 peptide fusion inhibitor and another four cultures with a trimer-stabilized IZN36 peptide fusion inhibitor. Both inhibitors target fusion-intermediate conformations of Env (11). As seen with the R5 HIV-1 JRCSF strain selected with the same peptides, with the X4 HIV-1 LAI strain resistance emerged much more quickly and to a greater extent to the more potent IZN36 peptide than the N36 peptide. Remarkably, despite differences in sequence and coreceptor use for the two viruses, the LAI virus selected the same two genetic pathways with the same frequency against the N36 peptide (Fig. 1) as the JRCSF virus (10). The glutamic acid-to-lysine substitution at position 560 (E560K) in HR1 (pathway 1) emerged as an early (founding) mutation in two of the cultures, while the glutamic acid-to-lysine substitution at position 648 (E648K) in HR2 (pathway 2) emerged as a founding mutation in the remaining N36 selection cultures. Additionally, as seen for the JRCSF strain, IZN36 selected predominantly one pathway. However, the founding mutation in the IZN36 resistance cultures resided in different HRs for these two strains; the JRCSF strain selected E560K in HR1, but the LAI strain selected an asparagine-to-lysine substitution at position 637 (N637K) in HR2 (pathway 3). The latter mutation destroys a canonical glycosylation site that was previously reported to confer resistance to T20, C34, and N36 (18–20). The E560K mutation in HR1 additionally emerged in two of the IZN36 selection cultures. Curiously, the combination of E560K with an HR2 founding mutation was never seen in the JRCSF resistance cultures. None of the gp41 founding mutations arose in the control cultures (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Resistance pathways of LAI HIV-1 after selection with N36 and IZN36 peptide fusion inhibitors. Mutations are noted from top to bottom as they emerged in each culture. Passage number (P) and fold increase (x) in inhibitor concentration over the initial concentration are shown. Control cultures shown were passaged without peptides. The glutamic acid-to-lysine substitutions at residues 560 (E560K) and 648 (E648K) define pathways 1 and 2, respectively. The asparagine-to-lysine substitution at residue 637 (N637K) defines pathway 3. C, culture. Con, control.

A few additional substitutions in several regions of gp41 also emerged. In HR2, a leucine-to-serine substitution at position 669 (L669S, C4-1 Env) and an asparagine-to-serine substitution at position 651 (N651S, C1 Env) each emerged in a single pathway 1 and 2 culture, respectively, while a leucine-to-isoleucine substitution at position 663 (L663I, C7 Env) emerged in a pathway 3 culture. A substitution at location 651 (Con1 Env) also emerged in one of the control cultures, indicating that it is an adaptive mutation to growth in cell culture. Other gp41 mutations that arose in pathway 3 cultures were a threonine-to-isoleucine substitution at position 676 (T676I, C5 and C6 Envs), an isoleucine-to-valine substitution at position 684 (I684V, C2 Env) near the transmembrane domain, and in the cytoplasmic domain, a glutamine-to-arginine substitution at position 718 (Q718R, C1 Env) and a tryptophan-to-arginine substitution at position 790 (W790R, C2 Env). None of these mutations were seen in the control cultures.

Several mutations in different regions of gp120 also emerged in many of the resistance cultures, likely reflecting adaptation to PM-1 cells containing low levels of receptors and possibly also compensation for the gp41 resistance mutations. In the constant 1 region, a valine-to-alanine substitution at position 68 (V68A, C1 Env) and a glutamine-to-leucine substitution at position 114 (Q114L, C2 Env) emerged. In the V1V2 loop, the following mutations emerged: a serine-to-asparagine substitution at position 143 (S143N, C7 Env), a glutamic acid-to-lysine substitution at position 146 (E146K, C6 Env), a tyrosine-to-histidine substitution at position 177 (Y177H, C5 Env), and a serine-to-arginine substitution at position 190 (S190R, C1 and C4-2 Envs). In the constant 2 region, a histidine-to-tyrosine substitution at position 216 (H216Y, C8 Env) and an asparagine-to-aspartic acid substitution at position 276 (N276D, C2 Env) emerged. The N276 potential N-linked glycosylation site (PNGS) is required for neutralization by the CD4-binding site-specific HJ16 monoclonal antibody (21). Several other Envs acquired mutations that abolished PNGS, including the asparagine-to-serine or -lysine mutation at position 301 (N301S/K, C3, C7, Con3, and Con5 Envs) in the V3 loop, as well as deletions of five residues starting at position 395 (loss of WFNST) in the V4 loop or five residues starting at position 139 (loss of NTNSS) in the V1 loop, which occurred in two additional Envs from pathway 3 (C6 and C8 Envs). PNGS mutations at N301 were previously reported to cause the virus to be more susceptible to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that recognize the CD4 binding site (22). Additional mutations included a glutamic acid-to-lysine mutation (E409K, C2 Env) in the V4 loop and an aspartic acid-to-glutamic acid substitution and a glutamic acid-to-lysine substitution at positions 474 (D474E, C4-2 Env) and 492 (E492K, C3 Env), respectively, in the V4 loop. These residues reside in the vicinity of the CD4 binding site and have been reported to affect viral fusion and fitness (19).

In the five control cultures, a few adaptive mutations emerged in the V3 region, in the loop region connecting HR1 and HR2, and in the HR. These substitutions involved an asparagine-to-tyrosine substitution at position 651 (N651Y, Con1 Env), a lysine-to-methionine substitution at position 655 (K655M, Con2 Env), and a leucine-to-phenylalanine mutation at position 602 (L602F, Con4 and Con5 Envs) in gp41. In the gp120 V3 region, an asparagine-to-lysine substitution at position 301 (N301K, Con3 and Con5 Envs) and a threonine-to-lysine substitution at position 303 (T303K, Con2 Env) emerged, which results in a loss of a PNGS.

Founding resistance mutations reside in HR1 and HR2.

Envs containing mutations present in the final resistance cultures (EnvRs) were incorporated into pseudoviruses and assessed for resistance in single-round infections using Affinofile cells with low levels of CD4 and CXCR4 receptors, comparable to levels in the PM-1 cells used in the resistance cultures. The PM-1 cells used in the resistance cultures did not support robust infections of pseudoviruses, making them unsuitable for generating dose-response curves. In the Affinofile cells with low levels of CD4 and CCR5, pseudoviruses with EnvRs had higher titers than pseudoviruses with the parental wild-type Env (data not shown), consistent with acquisition of adaptive mutations due to growth in culture. Because our prior studies using the JRCSF strain showed that the gp120 adaptive mutations segregated into different regions of gp120 depending on the gp41 resistance pathway that was selected (10, 13), we were interested in determining whether the same pattern of gp120 adaptive mutations would be selected in the LAI strain grown under selection conditions identical to those for the JRCSF strain.

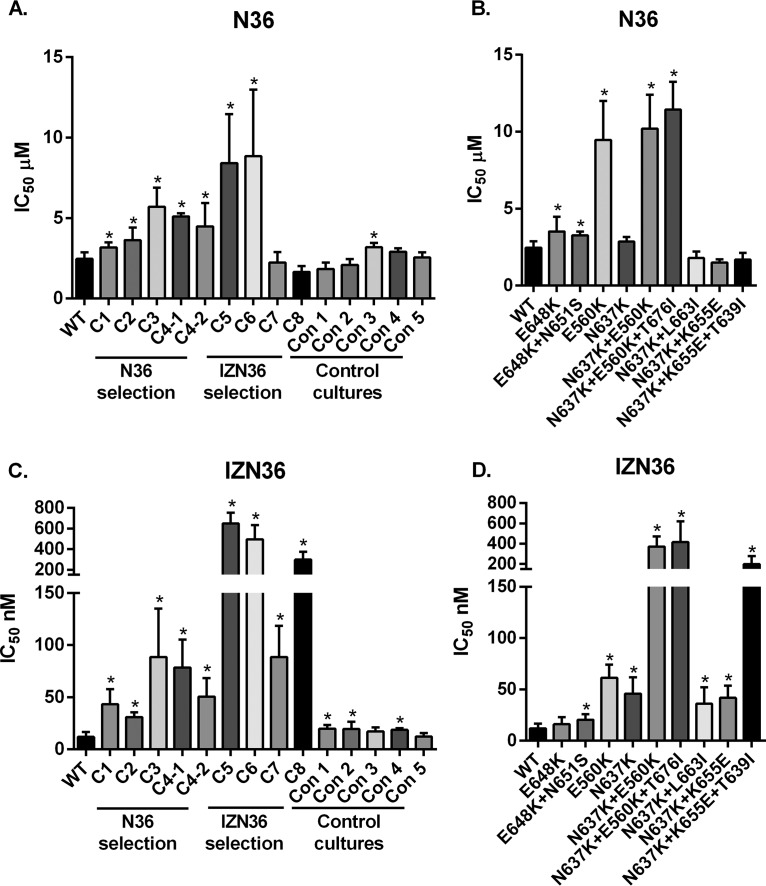

All EnvRs conferred resistance to the selecting peptide, and many exhibited cross-resistance to the other HR1 peptide inhibitor (Fig. 2). Pseudoviruses with EnvRs from cultures selected with N36 (C1, C2, C3, C4-1, and C4-2) exhibited modest resistance to N36 (Fig. 2A), ranging from 1.3- to 2.3-fold increased resistance compared to that of the WT. Envs with the E560K mutation showed the highest levels of resistance (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, pseudoviruses with C1 to C4 EnvRs were even more resistant to IZN36, exhibiting 2.6- to 7.5-fold increased resistance compared to that of the WT (Fig. 2C). C5 to C8 EnvRs from cultures selected with IZN36 conferred high-level resistance to IZN36, ranging from 7.5- to 55-fold increased resistance compared to that of the WT (Fig. 2C). The combination of N637K and E560K mutations synergized to confer the highest levels of resistance (Fig. 2D). Pseudoviruses with C5 and C6 EnvRs were also cross-resistant to N36 (Fig. 2A), likely due to the E560K mutation. We also observed low-level resistance against the N36 peptide in pseudoviruses with the Env from control culture 3 (Con3) and against the IZN36 peptide in pseudoviruses with Envs from control cultures 1, 2, and 4 (Con1, Con2, and Con4). These mutations in the control cultures likely reflect adaptive mutations to cells with low receptor levels, suggesting that more efficient use of receptors can modestly influence fusion inhibitor potency.

FIG 2.

N36 and IZN36 peptide inhibition of pseudovirus bearing Envs with mutations that emerged in the resistance cultures. The IC50 values for the N36 and IZN36 peptides were determined using pseudoviruses with Envs containing various combinations of the mutations found in the resistance cultures and control cultures, normalized to the IC50 for the wild-type pseudovirus (WT). Pseudoviruses bearing Envs containing all mutations from each culture (A and C) or specified gp41 mutations (B and D) are shown. Averages and standard deviations (error bars) from at least three independent experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05 compared with the WT.

In summary, these results indicate that an X4 strain selects the same key resistance mutations in either HR1 or HR2 as an R5 strain for conferring resistance to the unmodified HR1 peptide. Like the R5 virus, the X4 virus preferentially selected one genetic pathway to acquire resistance to the trimeric IZN36 peptide. However, in contrast to the R5 virus that selected the key HR1 resistance mutation for IZN36 resistance, the X4 virus selected a key HR2 resistance mutation. The IZN36 trimeric peptide is believed to target the HR2 region of gp41. While there are several sequence differences in HR2 between the X4 and R5 viruses used for selections, it is unclear how these differences might affect selection of different resistance pathways. Nonetheless, use of a different HR2 resistance pathway for the IZN36 peptide suggests that these X4 and R5 viruses differ in how they refold to form the 6HB. It has been reported that Env conformational changes from the native, prefusion structure through prehairpin fusion intermediates to the 6HB may occur in an asymmetric manner depending on receptor engagement (23).

Mutations in resistant Envs alter sensitivity to inhibition by an HR2 peptide fusion inhibitor and sCD4.

Since the resistance mutations likely affect the ability of peptides to bind to fusion-intermediate conformations of Env, we investigated how these mutations affect inhibition by an HR2 peptide fusion inhibitor and soluble CD4 (sCD4). Among the eight cultures selected for N36 or IZN36 resistance, only the EnvRs selected for resistance to IZN36 (pathway 3) conferred cross-resistance to T20 (Table 1). The C5, C6, C7, and C8 EnvRs conferred 1.96-, 2.70-, 11.29-, and 2.47-fold increased resistance to T20, respectively, compared to that of the WT. We note that a mutation at residue 637 was previously reported to be involved in resistance to N36 (18). This mutation was also reported to compensate for resistance mutations against C34 (19). On the other hand, pathway 1 EnvRs with HR1 mutations were slightly more sensitive to T20. T20 is expected to bind to the trimeric HR1 coiled coil of gp41, while IZN36 is expected to bind to the HR2 region of gp41. The C5 and C6 EnvRs have mutations in both HR1 and HR2, but the C7 and C8 EnvRs only have gp41 mutations in HR2. Therefore, cross-resistance to T20 appears to be due to an indirect mechanism involving primarily HR2 mutations.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of pseudoviruses with resistance mutations by sCD4 and T20

| Pseudovirus | sCD4 IC50 (μg/ml) |

T20 IC50 (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P valuea | Ratio to WT | Mean ± SDb | P valuea | Ratio to WT | |

| Env | ||||||

| WT | 2.694 ± 1.258 | 1 | 361 ± 141 | 1 | ||

| C1 | 0.025 ± 0.006 | 0.015* | 0.009 | 364 ± 121 | 0.978 | 1.01 |

| C2 | 0.247 ± 0.015 | 0.024* | 0.092 | 380 ± 188 | 0.876 | 1.05 |

| C3 | 0.052 ± 0.011 | 0.016* | 0.019 | 172 ± 39 | 0.042* | 0.48 |

| C4-1 | 0.046 ± 0.006 | 0.016* | 0.017 | 195 ± 92 | 0.095 | 0.54 |

| C4-2 | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 0.016* | 0.005 | 339 ± 50 | 0.78 | 0.94 |

| C5 | 0.038 ± 0.011 | 0.015* | 0.014 | 707 ± 334 | 0.105 | 1.96 |

| C6 | 0.051 ± 0.025 | 0.016* | 0.019 | 973 ± 312 | 0.012* | 2.7 |

| C7 | 0.035 ± 0.013 | 0.016* | 0.013 | 4077 ± 544 | <0.001* | 11.29 |

| C8 | 0.046 ± 0.020 | 0.015* | 0.017 | 893 ± 486 | 0.08 | 2.47 |

| Con1 | 0.065 ± 0.030 | 0.017* | 0.024 | 130 ± 39 | 0.019* | 0.36 |

| Con2 | 0.024 ± 0.008 | 0.015* | 0.009 | 129 ± 76 | 0.027* | 0.36 |

| Selected mutations | ||||||

| E648K | 1.754 ± 0.999 | 0.577 | 0.651 | ND | ||

| E648K+N651S | 0.152 ± 0.056 | 0.020* | 0.056 | ND | ||

| E560K | 0.393 ± 0.052 | 0.034* | 0.146 | ND | ||

| N637K | 1.249 ± 0.373 | 0.219 | 0.464 | ND | ||

| N637K+E560K | 0.260 ± 0.096 | 0.025* | 0.097 | ND | ||

| N637K+E560K+T676I | 0.044 ± 0.009 | 0.016* | 0.016 | ND | ||

| N637K+L663I | 0.057 ± 0.006 | 0.016* | 0.021 | ND | ||

| N637K+K655E | 0.036 ± 0.003 | 0.016* | 0.013 | ND | ||

| N637K+K655E+T639I | 0.036 ± 0.018 | 0.016* | 0.013 | ND | ||

*, P < 0.05.

ND, not done.

We next investigated whether the mutations changed sensitivity to sCD4. All EnvRs were orders of magnitude more sensitive to sCD4 than the WT (Table 1), including the C4-1 EnvR, which only contains gp41 mutations. Further analysis of single mutations and combinations of gp41 mutations showed that among the key pathway mutations, only the E560K, but not E648K or N637K, mutation conferred greatly increased sensitivity to sCD4. However, combination of E648K or N637K with other gp41 mutations greatly increased sensitivity to sCD4. These results suggest that specific residues in either HR1 or HR2 can influence Env interactions with or responses to CD4.

Resistance mutations affect 6HB stability.

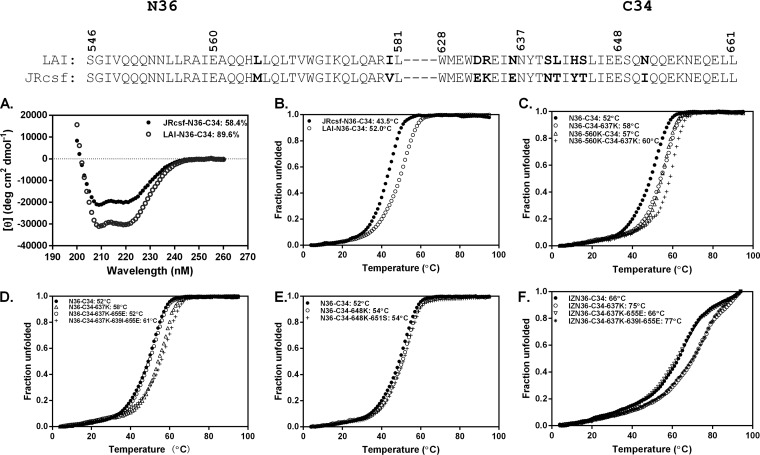

HR1 and HR2 peptide mixtures corresponding to the LAI and JRCSF strains self-assemble in solution and produce spectral tracings with high helical content consistent with coiled coils and formation of a 6HB (Fig. 3A). Thermal denaturation experiments further indicate that these helical bundles have high thermostabilities (Fig. 3B). Using mixtures of HR1 and HR2 peptides to model the 6HB, we investigated whether the resistance mutations directly impair inhibitor binding to gp41 by measuring the thermostability of inhibitor 6HB formed by mixtures of N36 or IZN36 peptides with HR2 peptides containing various resistance mutations. We also compared the thermostabilities of the inhibitor 6HBs to the thermostability of the wild-type and resistant, endogenous 6HBs (Fig. 3C to F and Table 2).

FIG 3.

Thermal denaturation studies of the α-helical complexes formed with HR1 and HR2 peptides. The α-helical content was calculated from the circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy signal at the indicated wavelengths. Unfolding was recorded at 222 nm by CD spectroscopy at the indicated temperatures, with calculated Tm values shown. (A and B) The CD of the complexes formed by mixing the C34 peptide corresponding to the LAI strain with the N36 peptide corresponding to the JRCSF or LAI strain (A) and their melting curves (B). (C) The melting curves of the complexes formed by mixing the C34 or C34-637K peptide with the N36 or N36-560K peptide. (D and E) The melting curves of the complexes formed by mixing the N36 peptide with the indicated C34 peptide. (F) The melting curves of the complexes formed by mixing the IZN36 peptide with the indicated C34 peptides. Results shown are representative of two experiments.

TABLE 2.

Thermal denaturation of the six-helix bundles formed by mixtures of HR1 (N36 or IZN36) and HR2 (C34) peptides with or without resistance mutations

| Selection inhibitor and culture | Endogenous bundle |

Inhibitor bundle |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide |

Tm (oC) | ΔTm (oC) | Peptide |

Tm (oC) | ΔTm (oC) | |||

| HR1 | HR2 | HR1 | HR2 | |||||

| N36 | ||||||||

| WT | N36 | C34 | 52 | N36 | C34 | 52 | ||

| C1, C2 | N36 | C34-648K | 54 | 2 | N36 | C34-648K | 54 | 2 |

| C1 | N36 | C34-648K-651S | 54 | 2 | N36 | C34-648K-651S | 54 | 2 |

| C3, C4 | N36-560K | C34 | 57 | 5 | N36 | C34 | 52 | |

| IZN36 | ||||||||

| WT | IZN36 | C34 | 66 | |||||

| C5, C6, C7, C8 | N36 | C34-637K | 58 | 6 | IZN36 | C34-637K | 75 | 9 |

| C5, C6 | N36-560K | C34-637K | 60 | 8 | IZN36 | C34-637K | 75 | 9 |

| C8 | N36 | C34-637K-655E | 52 | 0 | IZN36 | C34-637K-655E | 66 | 0 |

| C8 | N36 | C34-637K-639I-655E | 61 | 9 | IZN36 | C34-637K-639I-655E | 77 | 11 |

In thermal denaturation experiments, the 6HB with 560K (pathway 1), which corresponds to the resistant, endogenous 6HB, had a midpoint of the thermal unfolding transition (Tm) that was 5°C higher than that of the 6HB formed with the N36 inhibitor. The 6HB formed with C34 containing 637K (pathway 3), which corresponds to either the N36 inhibitor 6HB or resistant, endogenous 6HB, had a Tm that was 6°C higher than that of the wild-type 6HB (Fig. 3C). The combination of 560K and 637K increased thermostability of the resistant endogenous 6HB by an additional 2°C (Fig. 3C). The 655E residue in combination with 637K decreased 6HB thermostability, but it was greatly increased by the additional 639I residue (Fig. 3D). Mixtures of C34 peptides with 648K (pathway 2) and the N36 peptide formed 6HBs corresponding to either the N36 inhibitor 6HB or the resistant, endogenous 6HB. These 6HBs had thermostabilities that were 2°C higher than that of the wild-type 6HB (Fig. 3E).

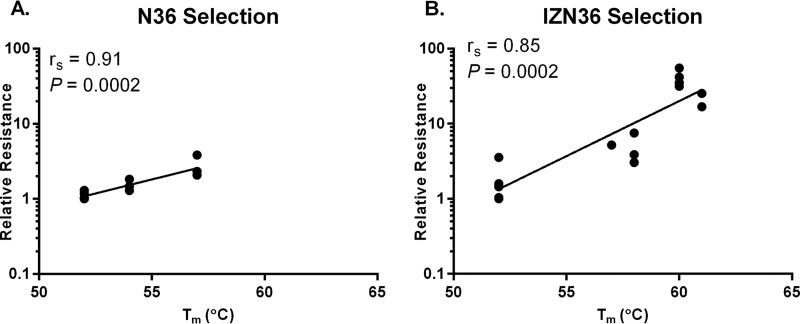

The inhibitor bundle formed with IZN36 and C34 had much higher thermostability than the wild-type 6HB, consistent with the trimer-stabilizing effect of the IZ motif on the N36 peptide. However, the melting curve indicates a more complicated unfolding pattern, perhaps due to the stability of the IZN36 trimer alone. The key 637K resistance residue (pathway 3) further increased the thermostability (Fig. 3F). Like the N36 inhibitor 6HB, the 655E residues reduced IZN36 6HB thermostability, but the additional 639I mutation greatly increased it (Fig. 3F). Taken together, mutations emerging in the EnvRs tended to increase the endogenous bundle stability in a stepwise manner. Moreover, we found a correlation between the Tm of the bundles containing resistance mutations from the respective selection cultures and the logarithmic 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) means of the peptides used for the selections (for N36, Spearman correlation coefficient [rs] of 0.91 and P = 0.0002; for IZN36, rs = 0.85 and P = 0.0002) (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). Interestingly, the correlation between Tm for the bundles with mutations selected by N36 and the IC50 for the IZN36 peptide was also significant, but there was only a trend in the correlation between Tm of the bundles with mutations selected by IZN36 and the IC50 for the N36 peptide (data not shown). This finding suggests that the loss of a PNGS from the key IZN36 resistance mutation (N637K) has an additional effect on IZN36 resistance. We also note that the 6HB formed with IZN36 and C34 peptides with or without resistance mutations showed higher thermostabilities than the endogenous 6HBs. Thus, for the IZN36 inhibitor, endogenous 6HB stability alone apparently does not fully account for resistance. Factors such as the IZ trimer extension in IZN36 or glycosylation-dependent alterations in gp41 conformational changes or coiled-coil dynamics appear to affect interactions of IZN36 with gp41.

FIG 4.

Correlation between stability of 6HB and resistance to HR1 peptide inhibitors. Correlations between Tm and the logarithmic mean IC50 of Env clones and single mutants relative to that of the WT (relative resistance) selected by N36 (A) and IZN36 (B). rs, Spearman correlation coefficient.

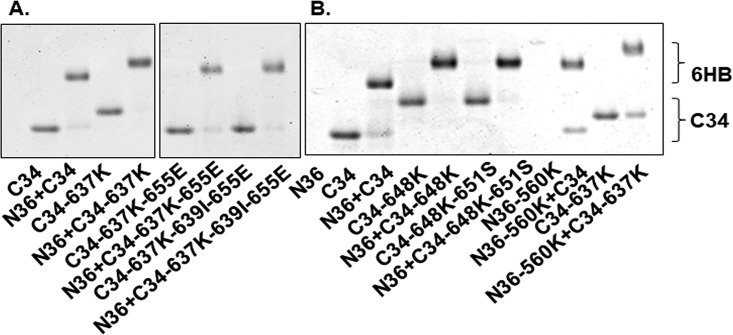

We also assessed the 6HB formed by mixing the HR1 and HR2 peptides using native PAGE (Fig. 5). Because the HR1 peptides have net positive charges and migrated out of the native gel, no bands could be visualized for the HR1 peptides alone. However, when HR1 peptides are mixed with an HR2 peptide, slower-migrating bands above the HR2 peptides alone indicate formation of the 6HB. The different migration of bands for C34 peptides alone or 6HBs formed by HR1 and HR2 peptide mixtures are due to the different charges and molecular masses of peptides with various mutations (Fig. 5). In all peptide mixtures involving N36 and C34 containing 637K and various additional residues that emerged in the resistance cultures from pathway 3, the C34 band with 637K shifted upwards, which is consistent with 6HB formation (Fig. 5A). Similarly, peptide mixtures involving N36 and C34 containing 648K and various additional residues that emerged in resistance cultures from pathway 2 also resulted in bands with slower mobility (Fig. 5B). The bands formed by the IZN36 and C34 peptide mixtures were not well resolved and migrated much more slowly than C34 alone or the N36 and C34 mixtures, consistent with the larger molecular mass of IZN36 compared with that of N36 (data not shown).

FIG 5.

Six-helix bundle complexes formed by mixing HR1 and HR2 peptides visualized using native PAGE electrophoresis. HR1 N36 peptides migrated off the gel due to their net positive charge. N36 and C34 peptides corresponding to mutations selected in pathway 3 (A) and pathways 2 and 3 (B). The upward migration of the C34 peptide bands reflects interactions with the N36 peptide. In panel A, both images are from the same gel, but lanes with irrelevant peptides were removed.

DISCUSSION

HR peptide fusion inhibitors are valuable probes for studying Env conformational changes and have potential as therapeutic agents. An HR2 peptide fusion inhibitor (T20) is available for clinical use, and its resistance profile has been well-characterized (17, 24). However, HR1 peptide fusion inhibitors have lagged in development, and less is known about their mechanisms of inhibition and resistance. Here, we characterized the genetic and mechanistic resistance pathways of HR1 peptide inhibitors. Our findings provide new insights into potential differences between X4 and R5 viruses in gp120-gp41 interactions that regulate receptor-induced conformational changes leading to formation of the 6HB.

Using the same two HR1 peptide fusion inhibitors that were used to select resistance in an R5 virus, we found that an X4 virus uses that same two genetic pathways, defined by the HR1 E560K (pathway 1) or HR2 E648K (pathway 2) key resistance mutation, to escape inhibition by the N36 HR1 peptide. However, in contrast to the R5 virus, the X4 virus selected the alternative N637K key HR2 resistance mutation (pathway 3) to escape the trimer-stabilized IZN36 HR1 peptide fusion inhibitor. Significantly, each of the pathway-defining mutations enhanced the thermostability of the 6HB, suggesting a shared mechanism of HR1 peptide resistance for X4 and R5 viruses. This mode of resistance that involves enhanced 6HB stability is distinct from the resistance mechanism of escape from an HR2 peptide inhibitor (enfuvirtide), which involves an initial resistance mutation that directly impairs inhibitor binding and decreases 6HB stability.

Details of how enhanced 6HB stability confers resistance are not entirely clear, but it apparently favors refolding of gp41 to form the endogenous 6HB over the inhibitor 6HB. The N36 peptide potentially interferes with refolding of the gp41 fusion intermediate to the 6HB in two ways: (i) by intercalating into the HR1 coiled-coil trimer and/or (ii) by forming a trimeric HR1 coiled coil that can bind to the HR2 in gp41 (11). Rather than selecting mutations that would directly impair peptide binding at two different sites in the gp41 prehairpin intermediate and consequently reducing the stability of the endogenous 6HB, both X4 and R5 viruses selected mutations that improved 6HB stability in a way that advantages the virus over inhibitors in an indirect yet efficient manner.

Curiously, the X4 and R5 viruses that we studied selected resistance mutations in different HRs to escape the trimeric IZN36 peptide inhibitor, which is expected to bind only the HR2 region of gp41; the R5 virus selected the HR1 E560K mutation (pathway 1) to escape IZN36, whereas the X4 virus selected the HR2 N637K (pathway 3) mutation. The latter mutation abolishes a potential glycosylation site and has been previously reported to confer resistance to peptide fusion inhibitors (18, 24). Changes in glycosylation may impair inhibitor binding by direct steric interference and/or by altering the kinetics of gp41 refolding, while the residue change itself also increases 6HB stability independent of glycosylation (Fig. 3). Among the twelve resistance cultures that we previously generated against HR1 peptide inhibitors using an R5 virus, we never detected the N637K mutation. We note that the N637K mutation does not confer significant resistance to N36 peptide in the LAI X4 HIV-1 Env without the E560K mutation, even though it does confer resistance to trimeric IZN36 peptide. Because N637K results in a significant increase in 6HB stability (Fig. 3D), lack of cross-resistance to N36 implies that increased 6HB stability alone is not sufficient to confer N36 resistance. Additional studies are needed to determine whether this resistance mutation is favorable only to X4 viruses.

In our prior study (12), we modeled the key gp41 resistance mutations E560K (HR1) and E648K (HR2) using available high-resolution 6HB structures and suggested that these mutations increase 6HB stability through rearrangements of hydrogen bond networks (10, 12). Notably, the Q577R mutation that frequently emerged in both pathways in the R5 HIV-1 resistance cultures did not appear in any of the X4 HIV-1 resistance cultures. We previously found that Q577R greatly increased 6HB stability while also reducing CD4-induced triggering to the six-helix bundle (25). The conspicuous absence of this resistance mutation in the LAI selections suggests that the X4 virus does not tolerate this change, raising the possibility that CXCR4 coreceptor use requires different modes of regulating Env conformational changes than CCR5 coreceptor use.

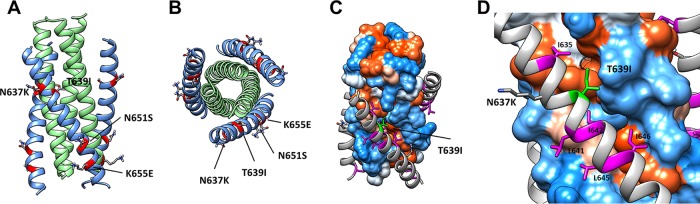

New gp41 mutations that emerged in pathways 1 and 2 in the X4 HIV-1 resistance cultures include N651S, L669S, and I684V. In high-resolution structures, the side chain of N651 is directed away from the 6HB core (Fig. 6). This mutation does not have a major effect on resistance or increase the thermostability of the 6HB (Table 2), and modeling does not reveal additional interactions that suggest a role in 6HB formation. Therefore, this mutation may be adaptive and/or compensate for other mutations. Residues 669 and 684 are not resolved in the available structures.

FIG 6.

Pathway 3 resistance mutations modeled in the six-helix bundle conformation. Mutations N637K, T639I, N651S, and K655E are modeled in the six-helix bundle conformation (PDB entry 1AIK) in a ribbon model in longitudinal view (A) and cross-section view (B) and in a hydrophobic surface rendition (Kyte & Doolittle scale) in longitudinal view (C), with the inset showing a close-up (D). Mutations N637K and K655E occupy positions c and g of the heptad repeat without obvious interactions affecting six-helix bundle stability. The T639I mutation in HR2 likely contributes additional hydrophobic interactions, with the hydrophobic cleft running between HR1 protomers. (D) HR2 hydrophobic residues are colored magenta and labeled. The T639I is labeled green.

Additional gp41 mutations that emerged in pathway 3 are T639I, K655E, L663I, and T676I. Modeling these residues shows that the side chain of T639I is positioned along a hydrophobic cleft formed by the interface of the underlying HR1 trimeric coiled coil (Fig. 6), possibly contributing additional hydrophobic interactions that increase 6HB stability (Fig. 3D) and resistance (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, the side chain of K655 is solvent exposed outside the 6HB core (Fig. 6) without apparent interactions that can readily explain changes in 6HB stability. This mutation does not increase resistance and may represent an adaptive mutation, consistent with a change in this residue in a control culture (Con2). Similarly, residues 663 and 676, which are not present in the high-resolution structure, also do not appear to play a significant role in resistance and may represent adaptive and/or compensatory mutations.

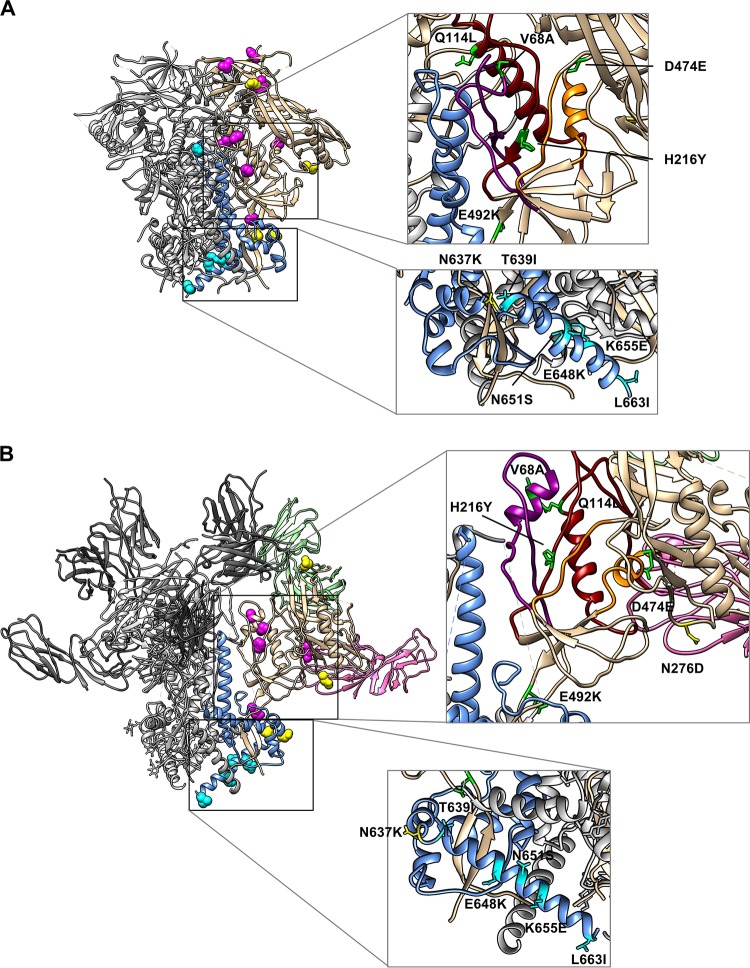

Assembly of the 6HB also depends on changes in gp120-gp41 interactions that release the gp120 hold on gp41, allowing gp41 to assume its low-energy 6HB conformation. In resistance cultures involving the R5 virus, we noted that each gp41 resistance pathway was associated with a different pattern of gp120 mutations. In contrast, the X4 virus selected a range of gp120 mutations without a clear pattern associated with the gp41 resistance pathways. While both X4 and R5 viruses selected mutations in the V3 and V1V2 trimer apex, only the X4 virus selected mutations in the gp120 inner domain layers that have been reported to be involved in the transition from native and CD4-bound conformations of Env (26). The V68A and Q114L mutations (C1 and C2 EnvRs, respectively) reside in topological layer 1, while H216Y (C2 EnvR) resides in topological layer 2 (Fig. 7A, upper inset, unliganded Env, and B, upper inset, liganded Env). Mutations at V68 and Q114 have been reported to reduce gp120-gp41 association (26). H216 is adjacent to Y217, which has been identified as having a significant role in gp120 response to CD4 binding in the R5 YU2 HIV-1 strain (26). The D474E mutation (C4-2 EnvR) is located adjacent to topological layer 3 (Fig. 7A and B, upper insets), lining the edge of the Phe43 cavity in the CD4-liganded state of gp120, that may alter Env interactions with CD4, as has been shown for other layer 3 residues (27). Overall, all Envs acquired gp120 mutations that increased sensitivity to sCD4 inhibition (Table 1), suggesting that these mutations enhance CD4 binding and/or increase Env conformational reactivity to receptor binding to improve growth in culture.

FIG 7.

Mutations from the HR1 resistance cultures modeled in Env trimers. Fusion inhibitor resistance mutations are modeled in the unliganded Env SOSIP trimer (PDB entry 5CEZ) (A) and the CD4- and 17b-liganded Env SOSIP trimer (PDB entry 5VN3) (B). In both panels, one protomer of gp120 is colored tan and one protomer of gp41 is colored light blue. The remaining protomers are colored gray. Mutations in gp120 are colored magenta, and mutations in gp41 are colored cyan. Mutations affecting N-linked glycosylation are colored yellow. Zoomed-in views of the gp120 inner domain and gp41 HR1 region highlight gp120 mutations located in and around its potential interaction sites with gp41 and gp120 topological layers (upper insets). The following color scheme was used for gp120 inner domain topological layers: layer 1, purple; layer 2, red; layer 3, orange. The HR2 gp41 mutations are amphipathic, perhaps allowing different interactions in different Env conformations (lower insets, shown rotated 180° from the trimer).

We also observed gp41 mutations that affected sCD4 sensitivity. As discussed above, the N651S mutation in HR2, which was identified in pathway 2 (C1 EnvR), had no apparent effect on 6HB formation or N36/IZN36 resistance (Fig. 2), but it affected sCD4 sensitivity (Table 1). The K655E (C8 EnvR), L663I (C7 EnvR), and T676I (C5 and 6 EnvR) mutations from pathway 3 appear to play a similar role, enhancing sCD4 sensitivity rather than increasing fusion peptide inhibitor resistance (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Whether these mutations are adaptive mutations independent of the resistance mutations or compensatory for resistance mutations is not clear. Regardless, these findings suggest these residues play a role in modulating the native structure or responsiveness of Env receptor binding. These residues are near, or beyond, the C-terminal end of available high-resolution native trimer structures, limiting the ability to model their potential interactions (Fig. 7A and B, lower insets). In the R5 virus resistance cultures, a glutamine-to-arginine substitution at residue 577 (Q577R) in HR1 emerged frequently in both pathways 1 and 2. This mutation increased sensitivity to inhibition by sCD4 but reduced CD4-induced conformational reactivity of Env (25). While this mutation was never seen in the resistance cultures of the X4 virus, the gp120 inner domain mutations and selected gp41 HR2 mutations observed in the resistance cultures for the X4 virus offer an alternative mechanism for modulating Env responses to CD4. The relationships between resistance mutations and associated compensatory or independent adaptive mutations are complex. Nevertheless, the coevolving mutations shed light on functional interactions across different regions of Env.

In summary, our selection studies that force HIV to escape inhibitors targeting Env fusion intermediates reveal a shared mechanism of resistance for an X4 and R5 HIV-1 but different patterns of mutations. Resistance involves gp41 mutations that increase thermostability of the 6HB for both the X4 and R5 viruses, but many of the associated gp120 mutations in these viruses reside in different regions of gp120. These findings highlight Env’s high degree of plasticity and suggest that CXCR4 and CCR5 coreceptor use require different gp120-gp41 networks for regulating Env conformational changes. Additional studies involving more strains are needed to determine whether these findings are more broadly representative of X4 and R5 HIV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

293T cells were provided by Dan Littman (New York University, New York, NY). Affinofile cells with inducible levels of CD4 and CCR5 (28) were provided by Benhur Lee (Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY). PM-1 lymphoid cells expressing CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 receptors (22) were obtained from Michael Norcross (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD). The proviral plasmid pLAI, expressing the LAI genome, was provided by Keith Peden (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD). The expression vector pCMV/R, the Env-deficient HIV genome plasmid pCMVΔ8.2, and the pHR’-Luc plasmid that contains the reporter gene were provided by Gary Nabel (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The LAI Env expression plasmid with wild-type sequence or selected mutations was made by inserting the env gene into the NotI and EcoRV restriction sites of the pCMV/R plasmid as described previously (10).

Reagents.

Synthetic peptides N36 for the LAI strain (corresponding to HXB2 residues 546 to 581; SGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQLTVWGIKQLQARIL) and its mutant (E560K), IZN36 (IKKEIEAIKKEQEAIKKKIEAIEKEISGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQLTVWGIKQLQARIL), C34 for the LAI strain (corresponding to HXB2 residues 628 to 661; WMEWDREINNYTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELL) and its mutants (N637K; N637K combined either with K655E or T639I and K655E; E648K; or E648K combined with N651S), N36 for the JRCSF strain (corresponding to HXB2 residues 546 to 581; SGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHMLQLTVWGIKQLQARIL), C34 for the JRCSF strain (corresponding to HXB2 residues 628 to 661; WMEWEKEIENYTNTIYTLIEESQIQQEKNEQELL), and T20 (YTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELLELDKWASLWNWF) were made by standard N-(9-fluorenyl) methoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry and purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography (CBER Facility for Biotechnology Resources, Silver Spring, MD). SDS-PAGE and analytic high-pressure liquid chromatography indicated that all the peptides were greater than 95% pure. All peptides were confirmed to have the expected molecular weight by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectroscopy. sCD4 was purchased from Progenics Pharmaceuticals (Tarrytown, NY).

Viruses.

Viral stocks of LAI HIV-1 were generated by transfecting the proviral molecular clone pLAI (GenBank accession number K02013.1) into 293T cells using Fugene 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and collecting filtered culture supernatants after 2 days. Virus was quantified by an HIV-1 p24 antigen capture assay (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) and stored at −80°C. HIV-1 LAI was passaged on PM-1 cells under increasing drug concentrations, starting at approximately the 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90; 10 μM for N36 and 100 nM for IZN36), as described previously (10). Briefly, resistant virus was generated by infecting 106 PM-1 cells with 30 ng of p24 from LAI HIV-1 stock in 4 ml of RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of each inhibitor overnight. The cells were washed once the next day by centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 min and resuspended with 4 ml of medium containing the same concentration of peptide. Three days later, half of the supernatant was exchanged with fresh medium containing peptide. After the first week, half of the cells and supernatant were removed every 3 days and replaced with an equal volume of peptide-containing medium. Cell supernatants were sampled every 3 days for virus production by p24 detection. Supernatants containing the highest level of p24 were then used to establish subsequent passages, using 30 ng of p24-containing supernatant, according to the infection protocol described above but with escalating peptide concentrations. Control viruses were passaged in the same manner but without peptide selection.

Env clones.

Genomic DNA from infected PM-1 cells was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen Group, Germantown, MD). The proviral DNA from each culture was amplified by PCR and sequenced, and chromatograms were inspected to confirm the dominant mutations arising in the env gene after each passage. env clones were created in the final passages by amplifying the env gene from the proviral genome using the Phusion kit (New England Bio labs, Inc., Ipswich, MA) and the pair of primers Env f (TATCCGATATCGCCGCCACCATGAGAGTGAAGGAGAAATATC) and Env r (TCTAGAGCGGCCGCTTATAGCAAAATCCTTTCCAAGC). The PCR product was inserted into the EcoRV and NotI sites in the Env expression plasmid pCMV/R-JRCSF-Env to replace the env gene. Clones used in the studies were verified to have the mutations that were present in the proviral DNA by sequencing the entire env gene. Two different clones corresponding to different genetic pathways were identified in culture 4 and were analyzed separately as C4-1 and C4-2. To confirm the contribution of each mutation in HR1 or HR2 for resistance, the mutations or selected combinations were introduced into the LAI env expression vector by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange II mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA).

Pseudovirus inhibition assay.

Pseudoviruses with WT or mutant Env proteins were generated and assessed for infectivity and neutralization by inhibitors as described previously (10). Briefly, 5 × 106 293T cells in 10-cm-diameter dishes were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of the env expression vector, 5 μg of the Env-deficient viral vector (pCMVΔ8.2), and 5 μg of reporter vector (pHR’-Luc). The supernatants were collected at 48 h posttransfection and filtered, and aliquots were stored at −80°C. Target cells (3 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates) were inoculated with approximately 0.5 × 105 relative light units of pseudovirus stocks in the presence or absence of peptide or sCD4 in a total volume of 100 μl supplemented with 8.0 μg of Polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per ml. Forty-eight h after infection, the luciferase activity was measured using luciferase substrate (Promega, Madison, WI) on a Spectramax-L luminometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

CD spectroscopy.

HR1 and HR2 peptides were mixed (10 μM each) in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 150 mM NaCl and incubated at 37°C for 30 min (final volume, 0.2 ml) prior to analysis. The isolated HR1 and HR2 peptides were also tested. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of these peptides or peptide mixtures were acquired on a Jasco spectropolarimeter (model J-810; Jasco, Inc.) at room temperature as describe previously (10). The α-helical content was calculated from the CD signal by dividing the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm by the value expected for 100% helix formation (33,000 degrees cm2 dmol−1). Thermal denaturation was monitored at 222 nm by applying a thermal gradient of 2°C/min in the range of 4 to 95°C. Reverse melt from 95 to 4°C was also detected. The melting curve was smoothed, and the midpoint of the thermal unfolding transition (Tm) value was determined using Jasco software. The Tm averages of at least two measurements for each complex were calculated. The fraction of unfolded molecules was analyzed according to a two-state N⇆U mechanism (29).

Native PAGE.

The 6HBs formed with HR1 and HR2 peptides were detected by native PAGE as described previously (10). The peptide pairs of N36 and C34 of each variant were incubated at a final concentration of 40 μM at 37°C for 30 min. The mixture was loaded onto a precast 18% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen). The gel was then stained with Coomassie blue before imaging (Odyssey LI-COR imaging system; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Statistics.

At least three independent dose-response curves were generated for each inhibitor. The IC50 values relative to no inhibitor for each individual pseudovirus were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis (GraphPad Prism Software, La Jolla, CA). The average IC50 was determined for each pseudovirus and inhibitor. The IC50 for each mutant was compared with that for the wild type using a t test with nonparametric assumption and no correction for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism Software, La Jolla, CA). P values equal to or less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ira Berkower and Konstantin Virnik (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research) for critical readings of the manuscript.

C.D.W. conceived the experiments. C.D.W. and M.Z. designed the experiments. M.Z., R.V., and C.Y. performed the experiments. M.Z., R.V., P.W.K., H.L., and W.W. analyzed the data. M.Z., P.W.K., and C.D.W. wrote the paper.

This work was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81201321 and 81871654), and the 46th Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars of State Education Ministry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta RA, Wild CT, Weng Y, Weiss CD. 1998. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat Struct Mol Biol 5:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He Y, Vassell R, Zaitseva M, Nguyen N, Yang Z, Weng Y, Weiss CD. 2003. Peptides trap the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein fusion intermediate at two sites. J Virol 77:1666–1671. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1666-1671.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koshiba T, Chan DC. 2003. The prefusogenic intermediate of HIV-1 gp41 contains exposed C-peptide regions. J Biol Chem 278:7573–7579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan DC, Kim PS. 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilgore NR, Salzwedel K, Reddick M, Allaway GP, Wild CT. 2003. Direct evidence that C-peptide inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry bind to the gp41 N-helical domain in receptor-activated viral envelope. J Virol 77:7669–7672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7669-7672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu M, Kim PS. 1997. A trimeric structural subdomain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. J Biomol Struct Dyn 15:465–471. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1997.10508958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bewley CA, Louis JM, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. 2002. Design of a novel peptide inhibitor of HIV fusion that disrupts the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. J Biol Chem 277:14238–14245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Root MJ, Kay MS, Kim PS. 2001. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science 291:884–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1057453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang M, Wang W, De Feo CJ, Vassell R, Weiss CD. 2012. Trimeric, coiled-coil extension on peptide fusion inhibitor of HIV-1 influences selection of resistance pathways. J Biol Chem 287:8297–8309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert DM, Kim PS. 2001. Design of potent inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from the gp41 N-peptide region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:11187–11192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201392898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Feo CJ, Wang W, Hsieh ML, Zhuang M, Vassell R, Weiss CD. 2014. Resistance to N-peptide fusion inhibitors correlates with thermodynamic stability of the gp41 six-helix bundle but not HIV entry kinetics. Retrovirology 11:86. doi: 10.1186/PREACCEPT-1715264856128511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, De Feo CJ, Zhuang M, Vassell R, Weiss CD. 2011. Selection with a peptide fusion inhibitor corresponding to the first heptad repeat of HIV-1 gp41 identifies two genetic pathways conferring cross-resistance to peptide fusion inhibitors corresponding to the first and second heptad repeats (HR1 and HR2) of gp41. J Virol 85:12929–12938. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05391-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg ML, Cammack N. 2004. Resistance to enfuvirtide, the first HIV fusion inhibitor. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:333–340. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mink M, Mosier SM, Janumpalli S, Davison D, Jin L, Melby T, Sista P, Erickson J, Lambert D, Stanfield-Oakley SA, Salgo M, Cammack N, Matthews T, Greenberg ML. 2005. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 amino acid substitutions selected during enfuvirtide treatment on gp41 binding and antiviral potency of enfuvirtide in vitro. J Virol 79:12447–12454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12447-12454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poveda E, Rodes B, Toro C, Martin-Carbonero L, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, Soriano V. 2002. Evolution of the gp41 env region in HIV-infected patients receiving T-20, a fusion inhibitor. AIDS 16:1959–1961. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izumi K, Nakamura S, Nakano H, Shimura K, Sakagami Y, Oishi S, Uchiyama S, Ohkubo T, Kobayashi Y, Fujii N, Matsuoka M, Kodama EN. 2010. Characterization of HIV-1 resistance to a fusion inhibitor, N36, derived from the gp41 amino-terminal heptad repeat. Antiviral Res 87:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nameki D, Kodama E, Ikeuchi M, Mabuchi N, Otaka A, Tamamura H, Ohno M, Fujii N, Matsuoka M. 2005. Mutations conferring resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion inhibitors are restricted by gp41 and Rev-responsive element functions. J Virol 79:764–770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.764-770.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Root MJ, Hamer DH. 2003. Targeting therapeutics to an exposed and conserved binding element of the HIV-1 fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:5016–5021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0936926100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh SS, Corti D, Heyndrickx L, Willems E, Vereecken K, Davis D, Vanham G. 2013. The N276 glycosylation site is required for HIV-1 neutralization by the CD4 binding site specific HJ16 monoclonal antibody. PLoS One 8:e68863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W, Nie J, Prochnow C, Truong C, Jia Z, Wang S, Chen XS, Wang Y. 2013. A systematic study of the N-glycosylation sites of HIV-1 envelope protein on infectivity and antibody-mediated neutralization. Retrovirology 10:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khasnis MD, Halkidis K, Bhardwaj A, Root MJ. 2016. Receptor activation of HIV-1 Env leads to asymmetric exposure of the gp41 trimer. PLoS Pathog 12:e1006098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldwin CE, Sanders RW, Deng Y, Jurriaans S, Lange JM, Lu M, Berkhout B. 2004. Emergence of a drug-dependent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant during therapy with the T20 fusion inhibitor. J Virol 78:12428–12437. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12428-12437.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller PW, Morrison O, Vassell R, Weiss CD. 2018. HIV-1 gp41 residues modulate CD4-induced conformational changes in the envelope glycoprotein and evolution of a relaxed conformation of gp120. J Virol 92:e00583-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00583-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finzi A, Xiang SH, Pacheco B, Wang L, Haight J, Kassa A, Danek B, Pancera M, Kwong PD, Sodroski J. 2010. Topological layers in the HIV-1 gp120 inner domain regulate gp41 interaction and CD4-triggered conformational transitions. Mol Cell 37:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desormeaux A, Coutu M, Medjahed H, Pacheco B, Herschhorn A, Gu C, Xiang SH, Mao Y, Sodroski J, Finzi A. 2013. The highly conserved layer-3 component of the HIV-1 gp120 inner domain is critical for CD4-required conformational transitions. J Virol 87:2549–2562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03104-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wild CT, Shugars DC, Greenwell TK, McDanal CB, Matthews TJ. 1994. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agashe VR, Udgaonkar JB. 1995. Thermodynamics of denaturation of barstar: evidence for cold denaturation and evaluation of the interaction with guanidine hydrochloride. Biochemistry 34:3286–3299. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]