Abstract

Background

Non‐adherence to tuberculosis treatment can lead to prolonged periods of infectiousness, relapse, emergence of drug‐resistance, and increased morbidity and mortality. In this review, we assess whether patient education or counselling, or both, promotes adherence to tuberculosis treatment.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of patient education or counselling, or both, on treatment completion and cure in people requiring treatment for active or latent tuberculosis.

Search methods

Without language restriction, we searched for eligible studies in the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and LILACS; checked reference lists of relevant articles; and contacted relevant researchers and organizations up to 24 November 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials examining the effects of education or counselling, or both, on treatment completion and cure in people with clinical tuberculosis; and treatment completion and clinical tuberculosis in people with latent disease.

Data collection and analysis

We independently screened identified studies for eligibility, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data; with differences resolved by consensus. We expressed study results as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We found three trials, with a total of 1437 participants, which examined the effects of different educational and counselling interventions on adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis.

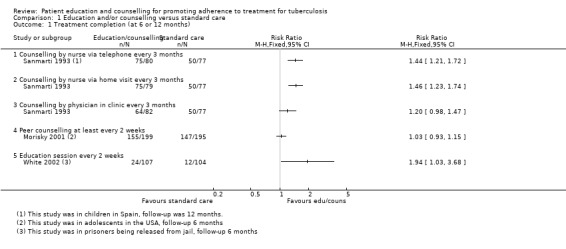

All three trials reported the proportion of people who successfully completed treatment for latent tuberculosis. Overall, education or counselling interventions may increase successful treatment completion but the magnitude of benefit is likely to vary depending on the nature of the intervention, and the setting (data not pooled, 923 participants, three trials, low quality evidence).

In a four‐arm trial in children from Spain, counselling by nurses via telephone increased the proportion of children completing treatment from 65% to 94% (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.72; 157 participants, one trial), and counselling by nurses through home visits increased completion to 95% (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.74; 156 participants, one trial). Both of these interventions were superior to counselling by physicians at the tuberculosis clinic (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.47; 159 participants, one trial).

In the USA, a programme of peer counselling for adolescents failed to show an effect on treatment completion rates at six months (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.13; 394 participants, one trial). In this trial treatment completion was around 75% even in the control group.

In the third study, in prisoners from the USA, treatment completion was very low in the control group (12%), and although counselling significantly improved this, completion in the intervention group remained low at 24% (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.68; 211 participants, one trial).

None of these trials aimed to assess the effect of these interventions on the subsequent development of active tuberculosis, and we found no trials that assessed the effects of patient education or counselling on adherence to treatment for active tuberculosis.

Authors' conclusions

Educational or counselling interventions may improve completion of treatment for latent tuberculosis. As would be expected, the magnitude of the benefit is likely to depend on the nature of the intervention, and the reasons for low completion rates in the specific setting.

17 April 2019

Update pending

Studies awaiting assessment

The CIDG is currently examining a search conducted up to 18 July, 2018 for potentially relevant studies. These studies have not yet been incorporated into this Cochrane Review.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Humans; Medication Adherence; Counseling; Counseling/methods; Latent Tuberculosis; Latent Tuberculosis/drug therapy; Patient Education as Topic; Patient Education as Topic/methods; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Counselling and education interventions for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis

Many people do not take their medication as prescribed. The consequences of this for chronic and debilitating infections like tuberculosis are serious and can include prolonged periods of infectiousness, relapse, emergence of drug‐resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates, and increased morbidity and mortality. Our review considered trials of education and counselling in promoting adherence to the treatment of both latent (dormant) and active tuberculosis.

We identified three very low quality evidence trials involving a total of 1437 participants that evaluated education and counselling interventions in promoting adherence to completion of medication for treatment of latent tuberculosis. Two of these studies demonstrated a beneficial effect of education and counselling upon adherence to drug treatment, whereas one did not.

There were substantial differences between trials with respect to populations targeted, interventions chosen and outcomes measured. The existing evidence is insufficient to guide policy on the use of education and counselling to promote adherence to tuberculosis therapy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings table 1.

| In people requiring treatment for latent tuberculosis, does education/counselling improve treatment completion? | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with latent tuberculosis Settings: Low and high resources settings Intervention: Any educational or counselling intervention Comparison: Standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard care | Education/counselling | |||||

| Completion of treatment | ‐ | ‐ | Not pooled | 923 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | Education or counselling may improve treatment completion in some circumstances |

| Incidence of active tuberculosis | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias: Allocation concealment was not adequately described in any of the studies 2 Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency: The effects varied between the studies as would be expected with different populations and different interventions. However there was a positive effect in two studies and no effect in a single study in adolescents where completion was high (75%) in the control group. 3 These studies were conducted in Spain and the USA. One study was among prisoners being released from prison, one among adolescents and one among tuberculin positive children

Background

Description of the condition

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease which may be caused by a variety of strains of mycobacteria, but usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body, such as the brain, the kidneys, or the spine. When a person with infectious tuberculosis coughs or sneezes, droplet nuclei containing M. tuberculosis are expelled into the air. If another person inhales air containing these droplet nuclei, he or she may become infected. However, not everyone infected with tuberculosis bacteria becomes sick. As a result, two tuberculosis‐related conditions exist: latent tuberculosis infection and tuberculosis disease (CDC 2012).

In latent tuberculosis, the person is infected with M. tuberculosis but does not feel sick and has no symptoms. The only sign of tuberculosis infection is a positive reaction to the tuberculin skin test. Persons with latent tuberculosis infection are not infectious and cannot spread tuberculosis infection to others. However, if tuberculosis bacteria become active in the body and multiply, the person will develop tuberculosis disease. The general symptoms of tuberculosis disease include: night sweats, weight loss, unexplained, fever, loss of appetite, fatigue, chills, chest pain, coughing for 3 weeks or longer and haemoptysis. Left untreated, each person with active tuberculosis disease will infect on average between 10 and 15 people every year.

Overall, one‐third of the world's population is currently infected with the tuberculosis bacillus. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the largest number of new tuberculosis cases in 2008 occurred in the Southeast Asia region, which accounted for 35% of incident cases globally. However, the estimated incidence rate in sub‐Saharan Africa is nearly twice that of Southeast Asia with over 350 cases per 100,000 population (WHO 2012).

Tuberculosis treatment regimens can vary, but they generally require the use of multiple drugs for a minimum of six months (Harries 2004). Regardless of which regimen is in place, patients often find it difficult to complete their course of drug treatment. Frequently they feel well after the first few months of treatment, when most of the tubercle bacilli have been killed, and stop taking the prescribed regimen of drugs. Personal factors (eg poor understanding of the disease or treatment requirements), drug side effects, drug resistance leading to protracted treatment periods, social and economic factors (eg stigma, lack of family support, and poverty), and health system factors (eg inconvenient treatment arrangements, poor patient‐provider relationships, and non‐availability of drugs) can further contribute to poor adherence to treatment (Atkins 2010; Comolet 1998; Rideout 1994). The consequences of not completing drug therapy are serious and can include a prolonged period of infectiousness, relapse, emergence of drug‐resistant M. tuberculosis isolates, and increased morbidity and mortality. Poor adherence to drug treatment therefore poses a serious risk to the community and contributes to failure in eradicating the disease globally (Addington 1979; Cuneo 1989; Fox 1983; WHO 2006).

In high‐risk groups, such as the homeless, intravenous drug users, people infected with HIV, and prisoners, completion of the drug treatment regimen poses special challenges. These groups contribute significantly to the global burden of tuberculosis and spread of the disease, and therefore warrant special attention within tuberculosis control and treatment programmes.

People at high risk of developing clinical tuberculosis who require preventive therapy (also referred to as chemoprophylaxis or treatment of latent tuberculosis) constitute yet another group for whom adherence to treatment is important (Chaisson 2001; Sanmarti 1993). The most common preventive therapy regimen is daily isoniazid for a period of 6 to 12 months, but other effective regimens also exist (Akolo 2010; Smieja 1999). The choice of regimen will depend on factors such as cost, the likelihood of adverse effects, adherence and drug resistance.

Treatment adherence can be defined as the extent to which people follow the instructions they are given regarding prescribed treatments. The term is intended to be non‐judgemental, a statement of fact rather than one of blame. Various strategies have been employed in an attempt to improve adherence to tuberculosis treatment. Many of these strategies target patients (eg reminders and prompts, defaulter action, education and counselling, incentives and reimbursements, contracts, peer assistance, and directly observed therapy). Other interventions are directed at healthcare providers (eg staff motivation and supervision) or the mode of treatment delivery (eg intermittent dosing and drug packaging). The cost of implementation of some adherence promoting strategies may be prohibitive, particularly in low‐resource settings in sub‐Saharan Africa and Asia where most of the burden of tuberculosis occurs (WHO 2006). Decisions should therefore be informed by solid evidence on what works, under what operational conditions they work, and at what cost, so that tuberculosis management policies and programmes can be aligned with available resources.

Description of the intervention

Techniques used in delivering patient education cover a wide spectrum of means, including dissemination of information via the mass media, provision of written, audiovisual, and computer‐based patient education materials by healthcare providers or institutions, and individualized counselling approaches.

A number of interventions have been used to promote adherence. This Cochrane Review is one of several published, planned, or in progress to evaluate each type of intervention:

Patient education and counselling: provision of information or one‐to‐one or group counselling about tuberculosis and the need to complete treatment (this review).

Staff motivation and supervision: training and management processes that aim to improve how providers care for people with tuberculosis.

Reminder systems and late patient tracers in the diagnosis and management of tuberculosis: routinely reminding patients to keep an appointment and actions taken when patients fail to keep an appointment (Liu 2008).

Incentives and reimbursements: money or cash to reimburse expenses of attending services, or to improve the attractiveness of visiting the service.

Contracts: written or verbal agreements to return for an appointment or course of treatment (Bosch‐Capblanch 2007).

Peer assistance: people from the same social group helping someone with tuberculosis return to the health service by prompting or accompanying them.

Directly observed therapy (DOT): an appointed agent (health worker, community volunteer, family member) directly monitors people swallowing their antituberculous drugs (Volmink 2007).

Material incentives and enablers in the management of tuberculosis (Lutge 2012).

How the intervention might work

Patient education and counselling aims to ensure that people have sufficient knowledge and understanding to make informed choices and actively participate in their own health care. In this review, we evaluated the impact of these interventions on adherence to drug treatment for active and latent tuberculosis. Patient education has been defined as a deliberate process of influencing patient behaviour and producing the changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices necessary to maintain or improve health (AAFP 2000). Providing patients with complete and current information about their health helps create an atmosphere of trust, enhances the healthcare provider‐patient relationship, and empowers patients to participate in their own health care. In this review, counselling refers to one‐on‐one or group interaction between the study participant(s) and a trained counsellor with the aim of providing tailored guidance and problem‐solving skills to help patients manage their health problem better. During the counselling sessions, attempts are made to understand the patient's level of understanding of tuberculosis and its treatment, and also explore any misconceptions. Emphasis is put on the tuberculosis infection, the importance of therapy and adherence to therapy, the possible adverse effects, and dietary habits. It is assumed that gains made at this level would be further strengthened during subsequent visits through education sessions.

Why it is important to do this review

Patient education and counselling strategies have been shown to improve treatment outcomes for certain conditions (Haynes 2008). However, their value for people with tuberculosis is unclear. Non‐adherence to drug treatment for tuberculosis has the potential to impact negatively on both the individual patient and on the broader health of the community. It is therefore important to evaluate which interventions are effective in supporting adherence and completion of tuberculosis drug treatment regimens.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to evaluate the effects of education or counselling, or both, on:

treatment completion and cure in people with clinical tuberculosis.

treatment completion and the incidence of clinical tuberculosis in people receiving antituberculosis preventive therapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (where the unit of randomization was the individual or a cluster).

Types of participants

Adults and children receiving treatment for active tuberculosis. Active tuberculosis is defined as having sputum smear‐positive sample, sputum culture‐positive sample, or if negative for the latter two, typical tuberculosis clinical findings coupled with radiographic assessment reports (WHO 2008).

Adults and children at risk of acquiring active tuberculosis (those with positive tuberculin skin test) who were receiving medication for prevention of the disease (chemoprophylaxis or treatment of latent tuberculosis).

Types of interventions

Intervention

Any educational or counselling intervention alone or in combination with each other aimed at improving adherence to antituberculous treatment or preventive chemotherapy. Trials in which education or counselling or both interventions were confounded by other types of interventions were excluded.

Control

Any alternative educational or counselling intervention, or 'no educational or counselling intervention' or 'usual care'.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Treatment for active tuberculosis:

Cure (for smear positive): defined as negative sputum smears in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion.

Adherence as measured by treatment completion (defined as completion of the antituberculous treatment and not classifiable as either cure or treatment failure, with failure taken to be a positive smear at five months or later during treatment).

Preventive therapy

Incidence of active tuberculosis: based upon microbiological diagnosis, histological diagnosis, or as a defined clinical syndrome by the trial authors.

Adherence as measured by treatment completion or as defined by trial authors.

Secondary outcomes

Treatment of active tuberculosis:

Incidence of resistance to antituberculous treatment, as reported by trial authors.

Death from any cause during the treatment period.

Preventive therapy:

Interval to active tuberculosis from initiation of preventive therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

We searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy described in Table 2: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (24 November 2011); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library (2011, Issue 11; MEDLINE (1966 to 24 November 2011); EMBASE (1974 to 24 November 2011); and LILACS (1982 to 24 November 2011).

1. Detailed search strategies.

| Search set | CIDG SRa | CENTRAL | MEDLINEb | EMBASEb | LILACSb |

| 1 | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis | tuberculosis |

| 2 | adherence | PATIENT COMPLIANCE | PATIENT COMPLIANCE | TUBERCULOSIS | adherence |

| 3 | compliance | PATIENT PARTICIPATION | COOPERATIVE BEHAVIOUR | PATIENT COMPLIANCE | compliance |

| 4 | counselling | HEALTH EDUCATION | TREATMENT REFUSAL | medication adherence | education |

| 5 | education | 2 or 3 | medication adherence | PATIENT‐EDUCATION | counselling |

| 6 | ‐ | 1 and 4 and 5 | 1 & 2 | HEALTH‐EDUCATION | 2 or 3 |

| 7 | ‐ | ‐ | 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 | counsel$ | 4 or 5 |

| 8 | ‐ | ‐ | HEALTH EDUCATION | 1 or 2 | 1 and 6 and 7 |

| 9 | ‐ | ‐ | COUNSELING | 3 or 4 | ‐ |

| 10 | ‐ | ‐ | HEALTH PROMOTION | 5 or 6 or 7 | ‐ |

| 11 | ‐ | ‐ | education | 8 and 9 and 10 | ‐ |

| 12 | ‐ | ‐‐ | counsel* | ‐ | ‐ |

| 13 | ‐ | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| 14 | ‐ | ‐ | 1 and 9 and 15 | ‐ | ‐ |

| aCochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register | bSearch terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Lefebvre 2011). upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term |

We searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) using 'tuberculosis', 'education', 'counselling', and 'adherence' as search terms.

We contacted researchers, authors of included trials, and other experts in the field of tuberculosis and adherence research. We also contacted relevant organizations, including the WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Tuberculosis Trials Consortium (TBTC), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD), and the Stop TB Partnership, for unpublished and ongoing trials. We checked the reference lists of all studies identified by the above methods.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We independently screened all citations and abstracts identified by the search strategy for potentially eligible studies. Subsequently, we used the titles and abstracts of the identified studies to exclude trials that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. We independently assessed the full text articles of potentially relevant trials using a pre‐specified trial inclusion criteria based on the study design features, type of participants, and features of interventions and controls. If a study's eligibility was unclear, we contacted the study authors for clarification. We excluded studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and documented the reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion.

Data extraction and management

Using a pre‐designed data extraction form, we independently extracted data from the selected trials. For each of the trials, the data we extracted included: methods, participant characteristics, interventions, and outcomes. For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the number of participants with the event of interest, the number randomized to each group, and the number analysed for each trial. Where study findings were uncertain or missing, we contacted trial authors for clarification and details. We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We independently assessed the risk of bias of each trial using a pre‐designed assessment form based on sequence generation (randomization); allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective reporting; and other potential threats to internal validity.

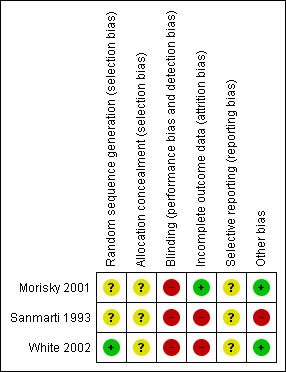

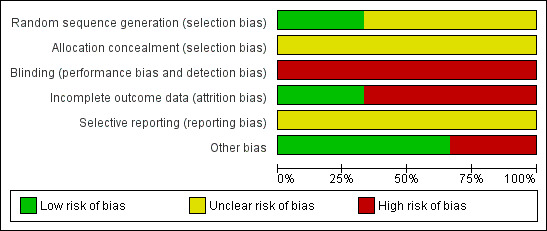

For each risk of bias component, we classified each trial as 'unclear’, 'yes', or 'no', corresponding with an unclear, low, or high risk of bias respectively, as described in Higgins 2008. The results of the assessment are summarized in the risk of bias table of Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1 and Figure 2. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of assessed trials for clarification. We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous data.

Dealing with missing data

We present the results of the studies individually using an available case analysis. We also conducted a best and worst case scenario to explore the effect of the missing data (losses to follow‐up) on the results for the only reported primary outcome, adherence.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by comparing patient and trial characteristics. The included trials were both clinically and methodologically variable. The populations in the three trials included children, adolescents and prisoners all having different issues for adherence. The peer counselling and educational interventions also differed substantially, and therefore we did not conduct a meta‐analysis and statistical heterogeneity is not reported.

Assessment of reporting biases

Statistical assessment of potential publication bias was not possible given the small number of eligible studies.

Data synthesis

Data analysis was conducted using Review Manager 5. We considered it inappropriate to pool the results of the three included studies given the substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity. The findings were therefore reported narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to perform subgroup analysis, with subgroups defined by the age, sex, and HIV status (positive/negative) of study participants, country income level (low‐, middle‐, and high‐income), and type of education or counselling, or both used. However, due to the small number of studies included in the review, we could not investigate heterogeneity using subgroups as previously planned.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

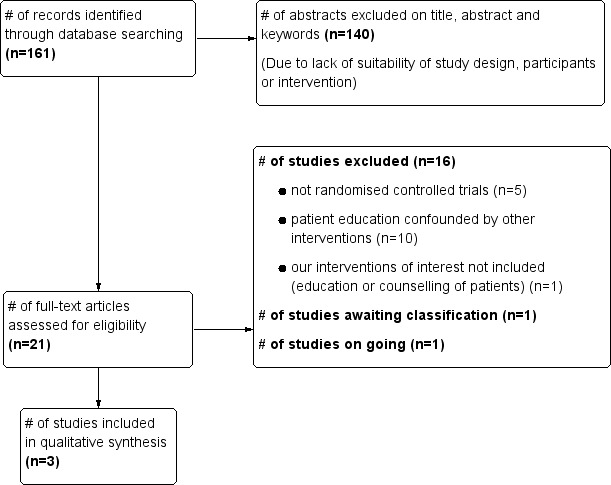

Figure 3 shows the summary of the trial selection process.

3.

Study flow diagram.

We performed a systematic search of electronic databases and other sources on five occasions between 25 April 2007 and 24 November 2011. We retrieved a total of 161 citations, 21 of which were judged to merit scrutiny of the full articles. Three of these, (Morisky 2001; Sanmarti 1993 and White 2002) met all review inclusion criteria. One, Megias 1990, is awaiting classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). This report was translated from Spanish to English to enable us to conduct a full assessment and data extraction. From the available information, it is not clear whether Megias 1990 and Sanmarti 1993 are duplicate papers and we have therefore written to the two primary authors to seek clarification. One study (Hovell 2003c) is ongoing (Ongoing studies). All of the other studies were excluded and their details provided in the table of Characteristics of excluded studies.

Included studies

Participants

We included three RCTs, with a total of 1437 participants on chemoprophylaxis for tuberculosis, and these are described in the Characteristics of included studies section. No studies involving patients on treatment for active tuberculosis met our inclusion criteria.

In Morisky 2001, participants were adolescents, with a mean age of 15.2 years. White 2002 studied prison inmates, with a median age of 29 years. In Sanmarti 1993, participants were children selected from a population with mean age of 6.5 years with education messages delivered to their mothers.

The included trials were conducted in the US (Morisky 2001; White 2002) and in Spain (Sanmarti 1993).

Interventions

Interventions were either education alone (Sanmarti 1993; White 2002) or education combined with counselling (Morisky 2001). In White 2002, education was delivered by research assistants and consisted of a one‐to‐one session in English or Spanish based on Centres for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines focusing on latent tuberculosis therapy, adverse effects, availability of free care after release, and location of, transportation to, and hours of the tuberculosis clinic. In Sanmarti 1993, education consisted of discussions on the importance and need for chemoprophylaxis and re‐issuing informative leaflets, and was delivered to mothers by a specialized nurse through telephone calls or home visits, or by a physician at the tuberculosis clinic. In Morisky 2001, education and counselling interventions based on a pre‐prepared protocol were provided by specially trained peer counsellors.

Outcomes

Preventative therapy

Incidence of active tuberculosis:

No studies measured the interval to active tuberculosis from initiation of preventive therapy.

Adherence:

Adherence measures were dichotomous in all the three studies. White 2002 assessed completion of the first visit to the tuberculosis clinic scheduled for one month after release from jail and completion rate of isoniazid at six months. Sanmarti 1993, evaluated clinic attendance at the final visit at 12 months, as well as the presence of positive Eidus‐Hamilton reaction in the urine at that visit. Morisky 2001 measured adherence by completion of the course of isoniazid after six months, measured using the discharge summary in the patient’s medical chart.

Treatment for active tuberculosis

No studies included patients on treatment for active tuberculosis.

Excluded studies

Sixteen studies that initially seemed to fit the inclusion criteria were eventually excluded from our review. The reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

The most common reasons for exclusion were the presence of confounding interventions and inappropriate study designs (ie non‐randomized clinical trials).

Risk of bias in included studies

The summary of risk of bias is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

White 2002 used an adequate method for generating the allocation sequence − a table of random numbers. The remaining two trial reports (Morisky 2001 and Sanmarti 1993) did not provide information on generation of allocation sequence and this aspect of the study was therefore judged as unclear. Allocation concealment, intended to prevent investigators from anticipating and influencing which group the participants might be allocated to, was unclear in all the three included studies as the process was not adequately described.

Blinding

Participants, personnel and assessors were not blinded in any of the included trials.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome reporting was adequate in two trials (Sanmarti 1993; Morisky 2001) and inadequate in (White 2002) (see Characteristics of included studies for details of individual studies).

Selective reporting

We were unable to access the protocols for the studies and have judged the reporting of outcomes as 'unclear'. However, there was no clear evidence of selective reporting in the included studies and all of the outcomes specified in the trials methods sections have been reported.

Other potential sources of bias

In one of the trials (Sanmarti 1993), participants in the experimental groups were contacted or seen every three months (thus, received additional attention) and an Eidus‐Hamilton reaction was performed at every visit, in addition to receiving the educational interventions. These additional interventions, which were not received by participants in the control group, could have introduced confounding.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Preventative therapy

Incidence of active tuberculosis

No studies measured the incidence of active tuberculosis from initiation of preventive therapy.

Adherence

In Sanmarti 1993, after 12 months of follow‐up all of those patients randomized (318) were included in the analysis. Adherence, measured by attendance at the last clinic visit, was significantly better in the group that received education by nursing personnel either by telephone (75/80) (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.72) or through home visits (75/79) (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.74). For those receiving education by physicians at the clinic, there was no statistically significant increase in attendance (64/82) (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.47). Compared to the control group, all three educational strategies had improved adherence as measured by the Eidus‐Hamilton reaction in the urine in the nursing education by telephone arm (68/80) (RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.89); in the education with home visits by a nurse (71/79) (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.99); and for those receiving education by a physician (61/82) (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.69).

In White 2002, of the 558 originally randomized to education (185), incentives (185) or a control group (188), 322 (57.7%) were included in the analysis. In the available case analysis in the paper, those in the education group (24/107) were almost twice as likely to complete therapy for latent tuberculosis at six months compared to those in the control group (12/104) (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.68). In addition, education increased the likelihood of completing the first tuberculosis clinic visit one month after release from jail (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.37). In a best case scenario analysis, assuming that all of those lost to follow‐up did in fact complete treatment, there was no statistical difference between the groups, education (103/185) versus control (97/188) (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.30); for a worst case scenario analysis assuming that those who were not reported did not complete therapy, those in the education group completed treatment (24/185) significantly more often than those in the control group (12/188) (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.94).

In Morisky 2001, 794 participants were randomized to four groups: peer counselling (199); contingency contracting (204), a combination of both (196), and usual care (195). The total percentage of randomized participants included in the analysis was 96.6% (767/794).The analysis was described as an intention‐to‐treat analysis, whereby all patients who did not have a measure for completion of care were assumed to have discontinued therapy and were coded as having not completed care. The authors then referred to exceptions in which patients whose treatment was discontinued by the physician, or who informed the clinics that they were moving, were analysed differently. It is unclear whether these patients were excluded from the analysis or were considered to have completed care. The results that are reported do not include all 794 initially randomized patients, and is therefore likely a modified intention‐to‐treat analysis. There was no statistically significant difference reported between the peer counselling and usual care groups. In a best case scenario, assuming that all those lost to follow up in either group did complete therapy, there was no significant difference between the peer counselling group (166/199) compared to the usual care group (153/195) (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.17). For a worst case scenario analysis, considering that all of those lost to follow up did not complete therapy, there was no statistical difference between the peer counselling (155/199) and the usual care (147/195) groups (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.15).

Treatment for active tuberculosis

No studies included patients on treatment for active tuberculosis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

There is very low quality evidence that in children at risk of tuberculosis, treatment adherence (as measured by attendance at the clinic at one year) is improved by mothers receiving an educational intervention delivered by nurses by telephone or by a home visit (Sanmarti 1993). Another study found that prison inmates receiving an educational intervention were more likely to complete treatment for latent tuberculosis than those who do not (White 2002). There is no evidence that peer counselling improves completion of treatment in adolescents with latent tuberculosis (Morisky 2001).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We did not find any eligible studies of patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment in patients with active tuberculosis. The three trials of participants with latent tuberculosis were conducted in the USA and Spain. The evidence base currently does not include participants living in low resource countries or those in special risk groups, such as HIV‐infected patients, intravenous drug users, the homeless, and others. Furthermore, to avoid high risk of bias we excluded a number of studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria, as described under Characteristics of excluded studies.

A key issue with the application of an educational and counselling intervention is the possible cost implications, particularly in settings already poorly resources in terms of staff or funds. A cost‐effectiveness study linked with Morisky 2001 described the direct costs of the counselling intervention relative to standard of care (Kominsky 2007). Direct costs included clinic visits, mantoux testing, chest X‐rays, costs of staffing and hiring of peer counsellors, and travel to the clinic for the patient. The usual cost of care in this American setting was $199, whereas the addition of peer counselling increased the cost to $277. It is difficult to extrapolate from this study the possible costs in other settings, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income settings where tuberculosis is most prevalent. However, this gives a good indication that the intervention would add costs, both in terms of human resources and necessary funding. The current data is insufficient to provide a relevant cost‐benefit assessment. Decision makers aiming to implement educational programmes based on evidence from other settings would have to consider the additional costs.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the GRADE quality of evidence for the outcomes assessed was rated as 'very low' and highlights the need for further large randomized controlled trials of education and counselling in people on drug treatment for active or latent tuberculosis. (Guyatt 2008) (Table 1). Only one included trial (White 2002) reported the method of randomization with adequate sequence generation, and none of them mentioned a method of treatment allocation which allowed for the concealment of study groups allocation. Furthermore, only one trial (Morisky 2001) addressed incomplete outcome data. Bias due to selective reporting was unclear in all three trials; however, two of them (Morisky 2001; White 2002) were free from bias from other sources while one, Sanmarti 1993, was not (Figure 1 & Figure 2). The sample sizes of the included trials were relatively small. Small trials are more likely than larger trials to be insufficiently powered to detect clinically and statistically significant differences between groups. Poor quality trials are more likely to be subject to bias and therefore the results are less reliable than those from better quality trials (Schulz 1995).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is very low quality evidence that education or counselling or both promotes adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis. We found no studies that examined the effectiveness of education or counselling or both interventions for improving adherence in patients with active tuberculosis.

There is therefore insufficient evidence to recommend the widespread use of education and counselling in tuberculosis services. Future efforts may need to look at the effectiveness and benefits of these interventions as there is some evidence in other disease conditions (Haynes 2008).

Implications for research.

There is a need for adequately powered, good quality, randomized controlled trials that evaluate education and counselling in people with latent and active tuberculosis. These studies should be designed to assess the effects of the interventions on the important clinical outcomes such as cure or tuberculosis incidence in participants living in countries with a high burden of tuberculosis. It may be more relevant to evaluate education and counselling as part of packages of care or interventions that support adherence.

Acknowledgements

Dr. James Machoki M'Imunya was awarded a Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm), funded by a grant from the Nuffield Commonwealth Programme, through The Nuffield Foundation. The editorial base for the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Education and/or counselling versus standard care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment completion (at 6 or 12 months) | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Counselling by nurse via telephone every 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Counselling by nurse via home visit every 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Counselling by physician in clinic every 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Peer counselling at least every 2 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Education session every 2 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education and/or counselling versus standard care, Outcome 1 Treatment completion (at 6 or 12 months).

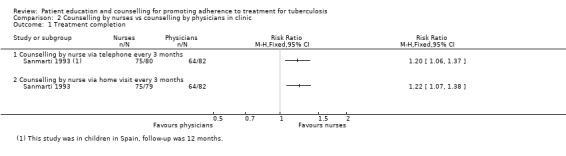

Comparison 2. Counselling by nurses vs counselling by physicians in clinic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment completion | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Counselling by nurse via telephone every 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Counselling by nurse via home visit every 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Counselling by nurses vs counselling by physicians in clinic, Outcome 1 Treatment completion.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Morisky 2001.

| Methods |

Randomized controlled trial; parallel group design. Duration: 6 months (1995 through 1998: recruitment and data collection) |

|

| Participants | Number enrolled: 794 Number available for analysis: 767 Inclusion criteria: Latent tuberculosis Exclusion criteria: Active tuberculosis Method of screening/confirmation: not indicated |

|

| Interventions |

Peer counselling: Specially trained adolescent peer counsellors who had previously completed treatment for latent tuberculosis, following a standardized protocol, contacted by telephone all participants assigned to them one week after commencement of treatment and at least every two weeks thereafter. The initial contact aimed to establish rapport and explain the role of the peer educator, and stressed the importance of clinic attendance and medication‐taking. Later contacts focused on addressing beliefs, problems or concerns. Parent‐participant contingency contract: With the assistance of program staff, parents and adolescents negotiated an incentive provided by the parent to be received if the adolescent adhered to the prescribed tuberculosis treatment ie keeping appointments with tuberculosis clinic and taking the tuberculosis medication every day. Combined use of peer counselling and incentives: Received both peer counselling and parent‐participant contingency contract interventions. Control (Usual Care): Received all of the treatment and educational services usually provided by the clinic, eg face‐to face health education from tuberculosis staff and assessment and health checks in response to treatment. All participants received US $15 as reimbursement for their time spent completing the baseline and post‐test interviews. All participants were also interviewed three times during the six months of their treatment. |

|

| Outcomes | Treatment adherence measured by treatment completion as reported in the participant's discharge medical summary. | |

| Notes |

Location: USA Setting: Two public clinics in Los Angeles, California, both serving large numbers of adolescents receiving care for latent tuberculosis infection Results of contingency contract and combined arms not reported in this review |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Participants were randomly assigned to one of four intervention groups". It is unclear how this was done. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It was not possible to blind the participants and personnel. Not stated if assessors were blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | At the end of the study (6 months) 96.6% participants were included in the analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not available. Results for all the outcomes listed under methods section were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Sanmarti 1993.

| Methods |

Randomized controlled trial; parallel group design. Duration: One year (1985 through 1987: recruitment and data collection) |

|

| Participants | Number enrolled: 318 Number analyzed: 264 Inclusion criteria: School children, both sexes in their first year of primary education with latent tuberculosis Method of screening: Mantoux test with 5 Tuberculin Units (TU) of Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) RT 23. A reaction of ≥ 6mm of induration was considered to be significant Exclusion criteria: Active tuberculosis; previous vaccination with BCG and; any contraindication to preventive therapy with isoniazid |

|

| Interventions |

Education by nurse via telephone: Mothers were telephoned by specialized nursing personnel every three months, who informed them of the advantages of chemoprophylaxis for their child’s health and encouraged them to continue with this preventive measure. Education by nurse via home visit: Specialized nurse visited the participant's home every three months, providing health education to mother and child, encouraging them to continue with the preventive therapy, and re‐issuing informative leaflets given at the first visit. Also, the Eidus‐Hamilton reaction was performed to objectively verify compliance with the therapy. Possible adverse reactions were monitored. Education by doctor at clinic: The child was seen by the physician every three months at the Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Centre. At each visit, the doctor gave educational messages to both mother and child, provided the same informative leaflets given at the first visit, monitored possible drug adverse reactions, and performed the Eidus‐Hamilton reaction. Education messages were standardized through use of the same health education script by both the physician and the nurses, and participants were given the same pamphlets. Control group: No health education activity was performed. After the first visit, the mothers were informed that unless they considered it appropriate there was no need to come back until after they had followed the treatment for 12 months. At recruitment, all the groups received the following: Parents were told how their children had to take isoniazid and given informative leaflets regarding tuberculosis and its prevention. They were also informed what symptoms to look for and to see the doctor if they suspected the existence of any of these symptoms or if they considered it advisable. For all the groups, the final visit consisted of medical history and examination, a chest X‐ray and the performance of the Eidus‐Hamilton reaction. |

|

| Outcomes | Treatment adherence measured by: Attendance at the last visit scheduled one year after starting treatment. Presence of positive Eidus‐Hamilton reaction in the urine during follow‐up (Groups II & III), and at last visit. |

|

| Notes |

Location: Spain. Setting: Public and private sector primary schools and referred to a Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Centre in the province of Barcelona. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomized", no further details provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It was not possible to blind the participants and personnel. Not stated if assessors were blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | At the end of the study (12 months) 83% participants were included in the analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not available. Results for all the outcomes listed under methods section were reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | There were two additional interventions given to Groups I, II & III that were not provided to the control group:1) contacted or seen every three months (thus, additional attention); and 2) Eidus‐Hamilton reaction performed at every visit. There is therefore a risk of confounding by these additional interventions. |

White 2002.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial; parallel group design. Duration: 6 months (March 1 1998 ‐ May 31 1999, recruitment and data collection). |

|

| Participants | Number enrolled: 558 Number released from jail on treatment for follow‐up: 325 Inclusion criteria: Jail inmates with latent tuberculosis infection and released into the community while still undergoing therapy. Method of screening/confirmation: not indicated Exclusion criteria: inmates whose jail term was for the duration of therapy; non‐English and non‐French speakers; violent, serious psychiatric illness, known HIV‐positive status. |

|

| Interventions |

Educational reminders: Visited by research assistant every two weeks for the duration of their jail stay to reinforce the initial information and messages of the first session. Incentive: Except for the first session, had no further contact with the study personnel in jail but were told they would receive a $25 equivalent in food or transportation vouchers if they went to the tuberculosis clinic within one month of release from jail. Clinic personnel contacted research assistants who met them to provide the incentives as arranged. Control: After the usual care during the first session, participants received no further contact with study personnel while in jail. All study participants in the intervention groups received from a research assistant a one‐to‐one session of education in English or Spanish based on Centres for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines focusing on LTBI (Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Where the person is infected with M. tuberculosis but does not feel sick and has no symptoms) therapy, adverse effects, availability of free care after release, and location of, transportation to, and hours of the tuberculosis clinic. The session emphasised that completing therapy could eliminate future risk of tuberculosis infection and ensured understanding of the messages. After this, the jail pharmacy personnel prepared a one‐month supply of isoniazid to be given to the inmate at release. |

|

| Outcomes | Treatment adherence measured by: First visit to the tuberculosis clinic within one month after release from jail. Completion of a full course of six months isoniazid therapy among those who went to the clinic. |

|

| Notes |

Location: USA Setting: Inmates of a prison in San Francisco. California All three intervention groups of inmates received DOT. The incentives group was excluded from the analysis in this review. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation determined by a random numbers table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Subjects were randomized using ordered sealed envelopes containing the allocation. Unclear whether envelopes were opaque. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It was not possible to blind the participants and personnel. Not stated if assessors were blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Less than 85% of the randomized participants were included in the final analysis. Of 558 participants randomized, 322 (57.7%) were assessed for completion of therapy. Reasons for exclusion of 236 participants were: finished isoniazid while in jail = 51; sent to another facility = 123; isoniazid discontinued = 60; and security reasons = 2. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not available. Results for all the outcomes listed under methods section were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alvarez 2003 | Patient education is confounded by provider education. |

| Barnwell 1992 | Not a RCT |

| Chaisson 2001 | Education and counselling confounded by multiple interventions including incentives. |

| Clark 2007 | Not RCT, selection was by consecutive admission into the hospital, no‐education group received supervision while taking the medications. |

| Hovell 2003a | Adherence coaching confounded by other interventions such as contingency contracting, shaping procedures, and interviewing. |

| Hovell 2003b | Not RCT, the sample consisted only of adolescents from 10 high/middle schools and whose parents had consented to their tuberculosis infection testing. |

| Janmeja 2005 | Intervention was behaviour modification by psychotherapy and not education or counselling or both as defined in the protocol. |

| Kominsky 2007 | This was a cost‐effectiveness and costs study of the same population described in the Morisky 2001 study and was therefore excluded. |

| Liefooghe 1998 | Counselling in the study involved additional intervention of activating the social networks and involvement of family members in motivating the patient and monitoring correct drug intake. |

| Malotte 1994 | Additional intervention of incentives was given to the special education intervention group (SI). |

| Morisky 1990 | Additional intervention of incentive of US $5 was given to the special education intervention group (SI). |

| Roy 2011 | Not an RCT, but rather participants were subjectively allocated to each arm. The outcome is increased knowledge of tuberculosis, rather than adherence. |

| Seetfa 1981 | Trial on patients "motivation" along with their household members. |

| Thiam 2007 | Confounded by additional multifaceted interventions: reinforced counselling through improved communication between health personnel and patients, decentralization of treatment, choice of DOT supporter by the patient, and reinforcement of supervision activities. |

| White 1998 | Confounded by additional intervention of financial incentive to the education group. |

| White 2005 | Not a RCT but a comparison of data from two previous studies: White 1998 and White 2002. |

| Wobeser 1989 | Additional intervention of daily observed prophylaxis to the education group. |

| Zwarenstein 2011 | Education was delivered to the staff, therefore would not be eligible on basis of the participants being staff, rather than patients. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Megias 1990.

| Methods |

RCT; parallel group design. Follow‐up: Until end of 12 months therapy. Sample size calculation: Done a priori |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: Asymptomatic tuberculin‐positive children, identified in routine screening surveys in schools of Cataluña, Spain by the Health and Social Security Department of the region, whose parents agreed to participate in the study. Number enrolled: 564: (Control = 160; Intervention 1 = 127, intervention 2 = 118 & intervention 3 = 159 ). Only 454 who turned up at the last clinic visit were included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics: Distribution by sex, age and race not given. |

| Interventions |

Intervention 1:Education by nurse via telephone: A follow‐up phone call by a nurse to the participant's mother, informing her of the advantages of the treatment for her child’s health and motivating her to continue treatment. The point at which this call was made is not given (as per the translation). Intervention 2:Education by nurse via home visit: A follow‐up visit every three months from a nurse who explained the advantages of the treatment and left some explanatory pamphlets. The nurse also tested the patient’s urine using the Eldus‐Hamilton reaction to check if treatment was being followed. Intervention 3:Education by doctor at clinic: Each participant was given an appointment to be examined by a doctor every three months. During the follow‐up, the doctor provided the same information, pamphlets included, as for group 2, and tested the patient’s urine with the Eldus‐Hamilton reaction. Control group (routine care): Participants were not given any educational materials or information during the twelve months of the study. Other than the first visit, they were not seen again until the end of the study 12 months later, when their urine was tested by the Eldus‐Hamilton reaction. To standardise educational messages imparted by the doctors and nurses, a health education guide was used. Participants in all comparison groups received a prescription for isoniazid prophylaxis at recruitment. |

| Outcomes | Completion of a full course of 12 months isoniazid therapy among those who went to the clinic at last visit. Completion of treatment was evaluated based on response to urine testing by the Eldus‐Hamilton reaction at the final visit to the clinic. Percentage compliance = (% E‐H +ve test in intervention group) ‐ (% E‐H +ve test in control group) |

| Notes |

Location: Spain Setting: School children in Cataluña Region Dates: Late 1980s The number of participants far exceeded the sample size which had been calculated at 214. We have written to both Megias and Sanmarti to confirm if their papers are duplicates. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Hovell 2003c.

| Trial name or title | Promoting Adherence to Tuberculosis Regimens in High Risk Youth: Effectiveness of Public Health Model of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Control for High‐Risk Adolescents |

| Methods |

Study design: Randomized, double blind (subject, caregiver, investigator, outcomes assessor), efficacy study, parallel assignment Inclusion Criteria: PPD positive ‐ San Diego County residents (without plans to relocate out of the county in the 12 months after study entry) ‐ able to respond to the interview questions in English or Spanish ‐ eligible for INH treatment. Exclusion Criteria: Receiving treatment in Mexico (due to differing medications and length of treatment). |

| Participants | Targetted sample size: 263, boys and girls, age: 13‐18 years. |

| Interventions | Behavioral: Adherence Program Behavioral: Life Skills and Self‐Esteem Training Program (Attention Control Arm) |

| Outcomes |

Primary: Adherence to an INH treatment regimen: assessed every 30 days, with the final outcome determined 12 months after treatment start date. Assessed using participant recall, urine testing for INH metabolites, pill counts, and medication event monitoring system (MEMS) caps. Secondary: Parent knowledge and practice of intervention support procedures, parent knowledge of tuberculosis, self‐esteem effects and life skills acquisition, cost and cost effectiveness of the intervention, and knowledge and practice of LTBI (Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Where the person is infected with M. tuberculosis but does not feel sick and has no symptoms) care by providers at participating community clinics. |

| Starting date |

Date of first enrolment: September 2003 Date of registration: 03/10/2005 Anticipated end date: Not given Last refreshed on: 17 March, 2009 |

| Contact information |

URL:http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00233168 Melbourne Hovell, (Study chair) San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA 92123 |

| Study ID |

NCT00233168 Register: ClinicalTrials.gov |

| Notes |

Location: USA Trial Registration No: NCT00233168 Source of funding: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) |

Differences between protocol and review

Amendment of the scope of the review: To include people receiving antituberculosis preventive therapy. After the initial publication of the protocol for this review, which considered only people with clinical tuberculosis, preliminary search and screening indicated that there were no controlled trials eligible for inclusion. Consequently the following were amended: (i) The title changed to: "Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis"; (ii) "Objectives", "outcome measures" and the "Criteria for considering studies for this review" sections were revised to include people receiving antituberculosis preventive therapy.

Inclusion of Tamara Kredo as a co‐author.

Contributions of authors

JMM drafted the protocol, and JV provided comments and suggestions. All three authors contributed to the various stages of the review process and the final version.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

South African Cochrane Centre, South Africa.

University of Nairobi Institute of Tropical and Infectious Diseases (UNITID), Kenya.

External sources

Nuffield Commonwealth Foundation, UK.

Department for International Development (DFID), UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Unchanged

References

References to studies included in this review

Morisky 2001 {published data only}

- Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Ebin V, Davidson P, Cabrera D, Trout PT, et al. Behavioral interventions for the control of tuberculosis among adolescents. Public Health Reports 2001;116(6):568‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sanmarti 1993 {published data only}

- Sanmarti SL, Megias JA, Gomez MN, Soler JC, Alcala EN, Puigbo MR, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of health education on the compliance with antituberculous chemoprophylaxis in school children: A randomized clinical trial. Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 1993;74:28‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

White 2002 {published data only}

- White MC, Tulsky JP, Goldenson J, Portillo CJ, Kawamura M, Menendez E. Randomized controlled trial of interventions to improve follow‐up for latent tuberculosis infection after release from jail. Archives of Internal Medicine 2002;162(9):1044‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Alvarez 2003 {published data only}

- Alvarez Gordillo Gdel C, Alvarez Gordillo JF, Dorantes Jimenez JE. Education strategy for improving patient compliance with the tuberculosis treatment regimen in Chiapas, Mexico [Estrategia educativa para incremantar el cumplimiento del regimen antituberculosa en Chiapas, Mexico]. Pan American Journal of Public Health 2003;14(6):402‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barnwell 1992 {published data only}

- Barnwell MD, Chitkara R, Lamberta F. Tuberculosis prevention project. Journal of the National Medical Association 1992;84(12):1014‐8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaisson 2001 {published data only}

- Chaisson RE, Barnes GL, Hackman J, Watkinson L, Kimbrough L, Metha S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of interventions to improve adherence to isoniazid therapy to prevent tuberculosis in injection drug users. American Journal of Medicine 2001;110(8):610‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clark 2007 {published data only}

- Clark PM, Karagoz T, Apikoglu‐Rabus S, Izzettin FV. Effect of pharmacist‐led patient education on adherence to tuberculosis treatment. American Journal of Health‐System Pharmacy 2007;64(5):497‐505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hovell 2003a {published data only}

- Hovell MF, Sipan CL, Blumberg EJ, Hofstetter CR, Slymen D, Friedman L, et al. Increasing Latino adolescents' adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: a controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health 2003;93(11):1871‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hovell 2003b {published data only}

- Hovell MF, Sipan CL, Blumberg EJ, Gil‐Trejo L, Vera A, Kelly N, et al. Predictors of adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection in high‐risk Latino adolescents: a behavioral epidemiological analysis. Social Science & Medicine 2003;56:1789‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Janmeja 2005 {published data only}

- Janmeja AK, Das SK, Bhargava R, Chavan BS. Psychotherapy improves compliance with tuberculosis treatment. Respiration 2005;72(4):375‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kominsky 2007 {published data only}

- Kominsky GF, Varon SF, Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Ebin VJ, Coly A, et al. Costs and cost‐effectiveness of adolescent compliance with treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: results from a randomized trial. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;40(1):61‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liefooghe 1998 {published data only}

- Liefooghe R, Suetens C, Meulemans H, Moran MB, Muynck A. A randomised trial of the impact of counselling on treatment adherence of tuberculosis patients in Sialkot, Pakistan. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 1999;3(12):1073‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malotte 1994 {published data only}

- Malotte CK, Morisky DE. Using an unobtrusively monitored comparison study group in a longitudinal design. Health Education Research 1994;9(1):153‐9. [Google Scholar]

Morisky 1990 {published data only}

- Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Choi P, Davidson P, Rigler S, Sugland B, et al. A patient education programme to improve adherence rates with antituberculosis drug regimens. Health Education Quarterly 1990;17(3):253‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roy 2011 {published data only}

- Roy A, Abubakar I, Chapman A, Andrews N, Pattinson M, Lipman M, et al. A controlled trial of the knowledge impact of tuberculosis information leaflets among staff supporting substance misusers: pilot study. PLoS One 2011;6(6):e20875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seetfa 1981 {published data only}

- Seetfa MA, Srikantaramu N, Aneja KS, Singh H. Influence of motivation of patients and their family members on the drug collection by patients. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis 1981;28(4):182‐190. [Google Scholar]

Thiam 2007 {published data only}

- Thiam S, LeFevre AM, Hane F, Ndiaye A, Ba F, Fielding KL, et al. Effectiveness of a strategy to improve adherence to tuberculosis treatment in a resource‐poor setting: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297(4):380‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

White 1998 {published data only}

- White MC, Tulsky JP, Reilly P, McIntosh HW, Hoynes TM, Goldenson J. A clinical trial of a financial incentive to go to the tuberculosis clinic for isoniazid after release from jail. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 1998;2(6):506‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

White 2005 {published data only}

- White MC, Tulsky JP, Menendez E, Arai S, Goldenson J, Kawamura LM. Improving tuberculosis therapy completion after jail: translation of research to practice. Health Education Research 2005;20(2):163‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wobeser 1989 {published data only}

- Wobeser W, To T, Hoeppner VH. The outcome of chemoprophylaxis on tuberculosis prevention in the Canadian Plains. Indian Clinical and Investigative Medicine 1989;12(3):149‐53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zwarenstein 2011 {published data only}

- Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, Mayers P, Bheekie A, English RG, et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Megias 1990 {published data only}

- Alcaide Megías J, Gómez MNA, Soler JC, Majen L S, Morales PG, Alcalá EN, Suñé Puigbó MR, Samarti SL. Influence of health education on compliance with anti‐tuberculosis chemoprophylaxis in children: a community trial. Revista Clínica Española 1990;187(2):89‐93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Hovell 2003c {published and unpublished data}

- Promoting Adherence to Tuberculosis Regimens in High Risk Youth: Effectiveness of Public Health Model of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Control for High‐Risk Adolescents. Ongoing study Date of first enrolment: September 2003 Date of registration: 03/10/2005 Anticipated end date: Not given Last refreshed on: 17 March, 2009.

Additional references

AAFP 2000

- Anonymous. Patient education. American Academy of Family Physician (AAFP). American Academy of Family Physician 2000;62(7):1712‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Addington 1979

- Addington WW. Patient compliance: the most serious remaining problem in the control of tuberculosis in the United States. Chest 1979;76 Suppl(6):741‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Akolo 2010

- Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Atkins 2010

- Salla Atkins, David Biles, Simon Lewin, Karin Ringsberg, Anna Thorson. Patients' experiences of an intervention to support tuberculosis treatment adherence in South Africa. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 2010;15(3):163‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bosch‐Capblanch 2007

- Bosch‐Capblanch X, Abba K, Prictor M, Garner P. Contracts between patients and healthcare practitioners for improving patients' adherence to treatment, prevention and health promotion activities. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004808.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CDC 2012

- [Database] 2012. (http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm)(Accessed on 09‐03‐2012).

Comolet 1998

- Comolet TM, Rakotomalala R, Rajaonarioa H. Factors determining compliance with tuberculosis treatment in an urban environment, Tamatave, Madagascar. International Journal of Tuberculosis Lung Disease 1998;2(11):891‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cuneo 1989

- Cuneo WD, Snider DE. Enhancing patient compliance with tuberculosis therapy. Clinics in Chest Medicine 1989;10(3):375‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fox 1983

- Fox W. Compliance of patients and physicians: experience and lessons from tuberculosis‐ I. BMJ 1983;287(6384):33‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Alonso‐Coello P, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harries 2004

- Harries AD, Maher D, Graham S. TB/HIV: a clinical manual [WHO/HTM/TB/2004.329]. 2nd Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Haynes 2008

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.0.1. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org, [Updated September 2008]. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Liu 2008

- Liu Q, Abba K, Alejandria Marissa M, Balanag Vincent M, Berba Regina P, Lansang Mary Ann D. Reminder systems and late patient tracers in the diagnosis and management of tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006594.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lutge 2012

- Lutge EE, Wiysonge CS, Knight SE, Volmink J. Material incentives and enablers in the management of tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007952.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Review Manager 5

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5 Copenhagen. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2008.

Rideout 1994

- Rideout M, Menzies R. Factors affecting compliance with preventive treatment for tuberculosis at Mistassini Lake, Quebec, Canada. Clinical Investigations in Medicine 1994;17(1):31‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 9952;273:408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smieja 1999

- Smieja MJ, Marchetti CA, Cook DJ, Smaill FM. Isiniazid for preventing tuberculosis in non‐HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1999, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001363] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Volmink 2007

- Volmink J, Garner P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003343.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2006

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme. Global tuberculosis control, surveillance, planning and financing. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing: WHO Report 2006 [WHO/HTM/TB/2006.362]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

WHO 2008

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Programm. Implementing the stop TB strategy ; a handbook for national tuberculosis control programmes. Implementing the stop TB strategy ; a handbook for national tuberculosis control programmes, World Health Organization, 2008. (WHO/HTM/2008.401). World Health Organization, 2008:Chap 1: Case detection:13‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2012

- [Database] 2012. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/) (Accessed on 09‐03‐2012).