Abstract

Background

Schistosoma mansoni is a parasitic infection common in the tropics and sub‐tropics. Chronic and advanced disease includes abdominal pain, diarrhoea, blood in the stool, liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and premature death.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of antischistosomal drugs, used alone or in combination, for treating S. mansoni infection.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and LILACS from inception to October 2012, with no language restrictions. We also searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2012) and mRCT. The reference lists of articles were reviewed and experts were contacted for unpublished studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials of antischistosomal drugs, used alone or in combination, versus placebo, different antischistosomal drugs, or different doses of the same antischistosomal drug for treating S. mansoni infection.

Data collection and analysis

One author extracted data and assessed eligibility and risk of bias in the included studies, which were independently checked by a second author. We combined dichotomous outcomes using risk ratio (RR) and continuous data weighted mean difference (WMD); we presented both with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Fifty‐two trials enrolling 10,269 participants were included. The evidence was of moderate or low quality due to the trial methods and small numbers of included participants.

Praziquantel

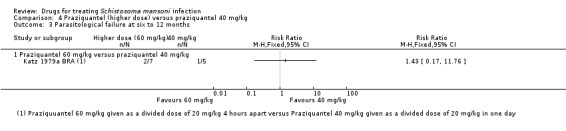

Compared to placebo, praziquantel 40 mg/kg probably reduces parasitological treatment failure at one month post‐treatment (RR 3.13, 95% CI 1.03 to 9.53, two trials, 414 participants, moderate quality evidence). Compared to this standard dose, lower doses may be inferior (30 mg/kg: RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.01, three trials, 521 participants, low quality evidence; 20 mg/kg: RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.64 to 3.02, two trials, 341 participants, low quality evidence); and higher doses, up to 60 mg/kg, do not appear to show any advantage (four trials, 783 participants, moderate quality evidence).

The absolute parasitological cure rate at one month with praziquantel 40 mg/kg varied substantially across studies, ranging from 52% in Senegal in 1993 to 92% in Brazil in 2006/2007.

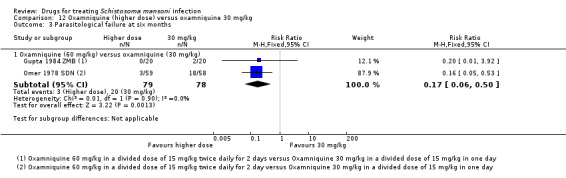

Oxamniquine

Compared to placebo, oxamniquine 40 mg/kg probably reduces parasitological treatment failure at three months (RR 8.74, 95% CI 3.74 to 20.43, two trials, 82 participants, moderate quality evidence). Lower doses than 40 mg/kg may be inferior at one month (30 mg/kg: RR 1.78, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.75, four trials, 268 participants, low quality evidence; 20 mg/kg: RR 3.78, 95% CI 2.05 to 6.99, two trials, 190 participants, low quality evidence), and higher doses, such as 60 mg/kg, do not show a consistent benefit (four trials, 317 participants, low quality evidence).

These trials are now over 20 years old and only limited information was provided on the study designs and methods.

Praziquantel versus oxamniquine

Only one small study directly compared praziquantel 40 mg/kg with oxamniquine 40 mg/kg and we are uncertain which treatment is more effective in reducing parasitological failure (one trial, 33 participants, very low quality evidence). A further 10 trials compared oxamniquine at 20, 30 and 60 mg/kg with praziquantel 40 mg/kg and did not show any marked differences in failure rate or percent egg reduction.

Combination treatments

We are uncertain whether combining praziquantel with artesunate reduces failures compared to praziquantel alone at one month (one trial, 75 participants, very low quality evidence).

Two trials also compared combinations of praziquantel and oxamniquine in different doses, but did not find statistically significant differences in failure (two trials, 87 participants).

Other outcomes and analyses

In trials reporting clinical improvement evaluating lower doses (20 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg) against the standard 40 mg/kg for both praziquantel or oxamniquine, no dose effect was demonstrable in resolving abdominal pain, diarrhoea, blood in stool, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly (follow up at one, three, six, 12, and 24 months; three trials, 655 participants).

Adverse events were not well‐reported but were mostly described as minor and transient.

In an additional analysis of treatment failure in the treatment arm of individual studies stratified by age, failure rates with 40 mg/kg of both praziquantel and oxamniquine were higher in children.

Authors' conclusions

Praziquantel 40 mg/kg as the standard treatment for S. mansoni infection is consistent with the evidence. Oxamniquine, a largely discarded alternative, also appears effective.

Further research will help find the optimal dosing regimen of both these drugs in children.

Combination therapy, ideally with drugs with unrelated mechanisms of action and targeting the different developmental stages of the schistosomes in the human host should be pursued as an area for future research.

15 April 2019

Update pending

Studies awaiting assessment

The CIDG is currently examining a new search conducted in April 2019 for potentially relevant studies. These studies have not yet been incorporated into this Cochrane Review.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Humans; Commiphora; Oxamniquine; Oxamniquine/therapeutic use; Plant Extracts; Plant Extracts/therapeutic use; Praziquantel; Praziquantel/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Resins, Plant; Schistosomiasis mansoni; Schistosomiasis mansoni/drug therapy; Schistosomicides; Schistosomicides/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Drugs for treating Schistosoma mansoni infection

Schistosoma mansoni is a parasitic worm common in Africa, the Middle East and parts of South America. The worm larvae live in ponds and lakes contaminated by faeces, and can penetrate a persons’ skin when they swim or bathe. Inside the host, the larvae grow into adult worms; these produce eggs, which are excreted in the faeces. Eggs rather than worms cause disease. Long‐term infection can cause bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pains, and enlargement of the liver and spleen.

In this review, researchers in the Cochrane Collaboration evaluated drug treatments for people infected with Schistosoma mansoni. After searching for all relevant studies, they found 52 trials, including 10,269 people, conducted in Africa, Brazil and the Middle East. Most trials report on whether or not the treatment stops eggs excretion; three reported the persons recovery from symptoms.

The results show that a single dose of praziquantel (40 mg/kg), as recommended by the World Health Organization, is an effective treatment for Schistosoma mansoni infection. Lower doses may be less effective, and higher doses probably have no additional benefit.

Oxamniquine (40 mg/kg), though now rarely used, is also effective. Again, lower doses may be less effective and no advantage has been demonstrated with higher doses.

Only one study directly compared praziquantel 40 mg/kg with oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, and based on this limited evidence, we are uncertain which intervention is more effective. Adverse events were not well reported for either drug, but were mostly described as minor and transient.

In children aged less than 5 years, there is limited evidence that these doses may be less effective, and further research will help optimise the dose for this age‐group.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Praziquantel 40 mg/kg for treating S. mansoni infection.

| Praziquantel 40 mg/kg for treating S. mansoni infection | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with S. mansoni infection Settings: Endemic settings Intervention: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg | ||||||

| Outcomes | Comparison | Illustrative comparative risks1 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Praziquantel 40 mg/kg | Comparator | |||||

|

Parasitological failure at 1 month |

versus placebo | 22 per 100 | 69 per 100 (23 to 100) | RR 3.13 (1.03 to 9.53) | 414 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4 |

| versus 20 mg/kg | 22 per 100 | 50 per 100 (34 to 72) | RR 2.23 (1.64 to 3.02) | 341 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | |

| versus 30 mg/kg | 22 per 100 | 33 per 100 (25 to 44) | RR 1.52 (1.15 to 2.01) | 521 (3 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | |

| versus 60 mg/kg | 22 per 100 | 21 per 100 (16 to 28) | RR 0.97 (0.73 to 1.29) | 783 (4 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6,7 | |

| versus split dose | 22 per 100 | 10 per 100 (3 to 37) | RR 0.47 (0.13 to 1.69) | 525 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,8 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is given in the footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Treatment failure with praziquantel 40 mg/kg ranged from 5% to 48% in the included studies. The risk given here is the median risk in these studies and is given for illustrative purposes. 2 No serious risk of bias. Both studies adequately concealed allocation and blinded participants and investigators. Loss to follow‐up was high in one study. 3 No serious inconsistency: Both trials showed statistically significant benefits with praziquantel but the size of the effect varied. In Kenya in 1999 failure with praziquantel was 43% at one month and in Uganda in 2009 it was 18%. 4 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: Only two trials from limited settings have evaluated this comparison. 5 Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias: These trials are more than twenty years old and do not provide an adequate description of methods to reduce the risk of bias. 6 No serious risk of bias: The three trials by Olliaro in 2010 adequately concealed allocation and blinded participants and investigators to be considered at low risk of bias. 7 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: The trials so far do not indicate a benefit with higher doses than 40 mg/kg. However, we cannot be certain that there might not be some benefit in specific settings. 8 Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency: One trial found a significant benefit with splitting the dose and one did not. The trials were of similar size and power.

Summary of findings 2. Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg for treating S. mansoni infection.

| Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg for treating S. mansoni infection | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with S. mansoni infection Settings: Endemic settings Intervention: Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg | ||||||

| Outcomes | Comparison | Illustrative comparative risks1 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg | Comparator | |||||

|

Parasitological failure at 1 month |

versus placebo2 | 18 per 100 | 100 per 100 (66 to 100) | RR 8.74 (3.74 to 20.43) | 82 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3,4 |

| versus 20 mg/kg | 18 per 100 | 68 per 100 (37 to 100) | RR 3.78 (2.05 to 6.99) | 190 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | |

| versus 30 mg/kg | 18 per 100 | 32 per 100 (21 to 50) | RR 1.78 (1.15 to 2.75) | 268 (4 trials) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | |

| versus 60 mg/kg | 18 per 100 | 8 per 100 (2 to 38) | RR 0.45 (0.09 to 2.11) | 317 (4 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is given in the footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Treatment failure with oxamniquine 40 mg/kg ranged from 5% to 24% in the included studies. The risk given here is the median risk in these studies and is given for illustrative purposes. 2 Parasitological failure for the comparison with placebo was only reported at three months. 3 Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: These studies did not adequately describe any methods to reduce the risk of bias. 4 Only two small studies have assessed this comparison. However, due to the very large effect size we have not downgraded further for indirectness or imprecision. 5 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: These studies are either too few, too small, or too old to have full confidence that the results can be generalized to widespread control of S. mansoni today.

Summary of findings 3. Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg.

| Praziquantel 40 mg/kg versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg for treating S. mansoni infection | |||||

|

Patient or population: People with S. mansoni infection

Settings: Endemic settings

Intervention: Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg Control: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

|

Praziquantel 40 mg/kg |

Oxamniquine 40 mg/kg |

||||

|

Parasitological failure at 1 month |

50 per 100 | 20 per 100 (7 to 61) | RR 0.40 (0.13 to 1.22) | 33 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: This study did not adequately describe any methods to reduce the risk of bias. 2 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: This single study is over 20 years old. 3 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: This trial is underpowered to detect what might be important differences in effect.

Summary of findings 4. Artesunate (12 mg/kg) plus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) versus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) alone.

| Artesunate (12 mg/kg) plus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) versus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) alone for treating S. mansoni infection | |||||

|

Patient or population: People with S. mansoni infection

Settings: Endemic settings

Intervention: Artesunate (12 mg/kg) plus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) Control: Praziquantel (40 mg/kg) | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Praziquantel | Artesunate plus praziquantel | ||||

|

Parasitological failure at 1 month |

50 per 100 | 31 per 100 (17 to 55) | RR 0.62 (0.35 to 1.09) | 75 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: This study did not adequately describe any methods to reduce the risk of bias. 2 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: This is a single study and the result is not easily generalized. 3 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: This trial is underpowered to detect what might be important differences in effect.

Background

Description of the condition

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic blood fluke infection, of which three species commonly infect humans; Schistosoma mansoni (common in the tropics and sub‐tropics), S. haematobium (mostly endemic in Africa and the Middle East) and S. japonicum (endemic in the People's Republic of China and the Philippines) (Engels 2002; WHO 2002; Gryseels 2006; Steinmann 2006; Utzinger 2009). It has been estimated that 779 million people are at risk of schistosomiasis worldwide and 207 million people may be infected (Steinmann 2006). Of these, 120 million people are estimated to be symptomatic and 20 million suffer from long‐term complications (Chitsulo 2000; WHO 2002; van der Werf 2003). In global burden of disease estimates, schistosomiasis causes 1.7 to 4.5 million disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) (WHO 2002; WHO 2004; Hotez 2006; Steinmann 2006; Utzinger 2009). Some suggest that this value may underestimate the true burden of schistosomiasis (WHO 2002; van der Werf 2003; King 2005; King 2007; King 2008a; King 2010).

People infected with S. mansoni excrete the fluke eggs in their faeces, and faecal contamination of freshwater allows these eggs to hatch into larvae (miracidia) which penetrate a specific freshwater snail (the intermediate host). Within the snail, the miracidia develop into cercariae (the infective larvae), which can penetrate a person’s skin upon contact with contaminated water bodies.

Following infection, the worms migrate through the human venous system, via the right chamber of the heart and the lungs, and through the mesenteric arteries and the liver via the portal vein, before finally settling in the superior mesenteric veins which drain the large intestine. Here, male and female worms mature, pair up and the female worms start to produce eggs (≂ 300 per day) (Davis 2009). An adult worm usually lives for three to five years, but some can live up to 30 years (Gryseels 2006). The eggs produced by the worms traverse the intestinal wall to be excreted in the faeces, and in the process some become trapped and initiate inflammatory reactions, which cause the underlying pathology and symptomatic illness (Richter 2003a; King 2008b). Early symptoms depend on the severity of infection (Gryseels 1987), and if treatment is not provided early, chronic illness and long‐term serious disease can follow.

Symptoms and effects

Schistosomiasis mansoni can present as an acute or chronic illness. The acute illness, or Katayama syndrome, is caused by migrating and maturing schistosomula that may result in a systemic hypersensitivity reaction characterized by fever, feeling of general discomfort (malaise), muscle pain (myalgia), fatigue, non‐productive cough, diarrhoea (with or without blood), and pain in the upper right part of the abdomen just below the rib cage. Chronic and advanced disease results from the host's immune response to schistosome eggs deposited in tissues and the granulomatous reaction evoked by the antigens they secrete and is characterized by non‐specific intestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and blood in the stool (Gryseels 1992; Gray 2011; Gryseels 2012).

Inflammatory reactions in the liver lead to hepatosplenic schistosomiasis, a key feature of chronic infection, which can manifest within a couple of months for heavy infections or many years after light infections. The chronic inflammation produces fibrotic lesions, which in turn lead to liver cirrhosis that progressively occludes the portal system giving rise to portal hypertension. The portal hypertension eventually leads to enlargement of hepatic arteries, and the associated oesophageal varices may rupture with heavy blood loss, haemorrhagic shock and death. The patient may also suffer repeated episodes of variceal bleeding – the primary cause of death in hepatic schistosomiasis (Andersson 2007). Severity of disease depends upon the intensity and duration of infection (Naus 2003), but recent evidence suggests the presence of the infection alone determines morbidity (King 2008a).

S. mansoni infection overlaps in distribution with S. haematobium in some areas of sub‐Saharan Africa resulting in mixed infections (WHO 2002). Unlike S. mansoni, the main early symptoms of S. haematobium infection are blood in urine (haematuria) and painful urination (dysuria). Chronic and advanced disease is insidious and may result in structural damage to the bladder wall which may eventually lead to kidney failure.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of S. mansoni infection is by microscopy for parasite eggs in the stool. Quantitative methods are recommended for epidemiological purposes because they allow estimation of intensity and evaluation of the impact of control programmes not only in terms of cure rate but also egg reduction rate (WHO 1985; Doenhoff 2004; Bergquist 2009). The Kato‐Katz technique (Katz 1972) is the most common quantitative technique (Booth 2003). Recently, the FLOTAC technique has been applied for the detection and quantification of S. mansoni eggs in stools with promising results and hence warranting further investigation (Glinz 2010).

Egg output can be influenced by several factors, such as day‐to‐day, intra‐stool, and seasonal variations as well as environmental conditions (Braun‐Munzinger 1992; Engels 1996; Engels 1997; Enk 2008). Therefore negative results following microscopic examination of a single stool are unreliable (de Vlas 1992; Kongs 2001; Booth 2003; Enk 2008), and measurement of prevalence and intensity of infection by egg count has shortcomings (Gryseels 1996; de Vlas 1997; Utzinger 2001a). Rectal biopsy is more sensitive than microscopy and is occasionally done when repeated stool examinations are negative for eggs. However, this method is unsuitable for use in population‐based control programmes (Allan 2001).

A monoclonal antibody‐based dipstick is increasingly being used for the diagnosis of the infection with promising results (Polman 2001; Legesse 2007; Legesse 2008; Caulibaly 2011). A more specific and sensitive diagnostic technique based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is increasingly being used in some reference laboratories in Europe (Sandoval 2006; Cnops 2012; Enk 2012). Ultrasound is used for diagnosing and assessing infection‐related pathology (Hatz 1990; Mohamed‐Ali 1991; Doehring‐Schwerdtfeger 1992; Hatz 2001; Richter 2003b).

Clinically, intestinal schistosomiasis is diagnosed on the basis of presence of blood in stool, (bloody) diarrhoea, and abdominal pain, but these are non‐sensitive and non‐specific (Gryseels 1992; Utzinger 2000c; Danso‐Appiah 2004) as diarrhoea or blood in stool can be due to other causes such as hookworm infection, dysentery and typhoid fever.

Description of the intervention

Schistosomiasis control measures implemented before the 1970s – when efficacious antischistosomal drugs were not available – focused mainly on interrupting transmission with molluscicides to kill the intermediate host snails (WHO 1985; Sturrock 2001). The 1970s marked the turning point in schistosomiasis control when efficacious drugs that can be applied in a single oral dose were discovered, shifting the control emphasis from transmission control to chemotherapy‐based morbidity control (WHO 1985; Cioli 1995). A body of evidence suggests that morbidity due to schistosomiasis can be prevented and pathology reversed with available antischistosomal treatments (Mohamed‐Ali 1991; Doehring‐Schwerdtfeger 1992; Savioli 2004; Zhang 2007; Webster 2009; Koukounari 2010).

Mass drug administration, or treatment of infected individuals or entire 'at‐risk' populations (eg school‐aged children), usually without prior diagnosis ‐ an approach termed 'preventive chemotherapy', is the control strategy currently pursued by the World Health Organization (WHO) and applied in many endemic countries (WHO 2006). Usually, praziquantel at a single 40 mg/kg oral dose is used (Fenwick 2009), but still there are uncertainties regarding this dose. An exception is Brazil where the national policy adopted since 1995 recommends a single oral dose of 60 mg/kg for children aged between two and 15 years, and 50 mg/kg for adolescents and adults (Favre 2009). The recently adopted policy for schistosomiasis control in Brazil disapproves of treatment without prior diagnosis, and therefore the preventive chemotherapy strategy is no longer applied in Brazil (Favre 2009).

Oxamniquine has also been used extensively for the control of schistosomiasis mansoni in different endemic countries, most notably Brazil, where more than 12 million doses of oxamniquine have been administered by the national schistosomiasis control programme (Katz 2008). There are uncertainties around the standard dose of oxamniquine (Foster 1987; Cioli 1995). Therefore, the WHO recommends total doses of 20 to 60 mg/kg (in divided doses of up to 20 mg/kg) (WHO 2001).

More recently, the artemisinin derivatives used in the treatment of malaria have been shown to have antischistosomal properties, particularly against the immature developing stages of the schistosome parasites (Borrmann 2001; Utzinger 2007). Praziquantel, in contrast, acts against the adult worms and the very young schistosomula just after skin penetration (Sabah 1986; Utzinger 2007).

The current emphasis of schistosomiasis control is to reduce the burden of disease in high endemicity areas and to interrupt transmission in low endemicity areas (WHO 2002). Intensity of infection is highest in school‐aged children and adolescents, therefore preventive chemotherapy is targeted especially to these at‐risk groups (Magnussen 2001; WHO 2002; Savioli 2004; Savioli 2009).

The efficacy of myrrh (Mirazid) in the treatment of intestinal schistosomiasis has been evaluated in Egypt (Barakat 2005 EGY; Botros 2005 EGY).

Why it is important to do this review

Currently, entire control and treatment programmes are based on praziquantel and there is risk of drug resistance and perhaps shortages of praziquantel. There is a need to assess alternative drugs or combinations. Still there are uncertainties around effective and safe dosage of praziquantel and standard doses of oxamniquine. There are also uncertainties about adequacy of current adult doses used in children.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of antischistosomal drugs, used alone or in combination, for treating S. mansoni infection.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Individuals infected with S. mansoni diagnosed microscopically for the presence of S. mansoni eggs in stool using the Kato‐Katz technique (Katz 1972), or any other quantitative diagnostic method, such as the quantitative oogram and FLOTAC techniques.

Types of interventions

The following comparisons are evaluated in this review:

Antischistosomal drugs alone or in combination versus placebo;

Antischistosomal drugs alone or in combination versus a different dose of the same antischistosomal drug; and

Antischistosomal drugs alone or in combination versus different antischistosomal drugs alone or in combination.

Trials that allocated non‐schistosomal drug or interventions in addition to the treatment and control of interest were eligible provided the same drug was allocated to both treatment and control groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Parasitological failure, defined as treated individuals who remained positive for S. mansoni eggs in stool using the standard Kato‐Katz or other quantitative techniques (follow‐up: up to one month).

Egg reduction rate, defined as percent reduction in S. mansoni egg count after treatment (follow‐up: up to 12 months).

Secondary outcomes

Parasitological failure (follow‐up: greater than one month).

Resolution of symptoms (eg abdominal pain, diarrhoea and bloody diarrhoea).

Resolution of pathology (eg hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, portal fibrosis, cirrhosis of the liver or colonic polyps) measured by ultrasound, by standard international classification or other standardized methods (CWG 1992).

Adverse events

Non‐serious adverse events.

Serious adverse events (ie any untoward medical occurrence or effect that at any dose: results in death; is life‐threatening; requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatients' hospitalisation; results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; is a congenital anomaly or birth defect).

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, under review and in progress).

Electronic searches

Databases

We searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy described in Table 5: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (October 2012); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (1966 to October 2012); EMBASE (1974 to October 2012); and LILACS (1982 to October 2012). We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) in October 2012 using ’Schisto * mansoni' as the search term.

1. Detailed search strategies.

| Search set | CIDG SR^ | CENTRAL | MEDLINE^^ | EMBASE^^ | LILACS^^ |

| 1 | Schisto* mansoni | SCHISTOSOMA MANSONI | SCHISTOSOMA MANSONI | SCHISTOSOMA MANSONI | Schisto$ mansoni |

| 2 | Esquistossomose | SCHISTOSOMIASIS MANSONI | SCHISTOSOMIASIS MANSONI | SCHISTOSOMIASIS MANSONI | Esquistossomose |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | Intestinal schistosom* ti, ab | Intestinal schistosom* ti, ab | Intestinal schistosom$ ti, ab | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | Bilharzia* | Bilharzia* | Bilharzia$ | ||

| 5 | Esquistossomose ti, ab | Esquistossomose ti, ab | Esquistossomose ti, ab | ||

| 6 | Schistosomicide* | Schistosomicide* | Schistosomicide$ | ||

| 7 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | ||

| 8 | Limit 7 to humans | Limit 7 to humans | |||

| ^Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register | ^^Search terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011); Upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; Lower case: free text term |

Searching other resources

Researchers and organizations

We contacted individual researchers working on antischistosomal drugs, pharmaceutical industries and experts from the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) for unpublished data and ongoing trials.

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all studies identified by the aforementioned methods for additional relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Vittoria Lutje, the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (CIDG) Information Retrieval Specialist, searched the literature and retrieved studies using the search strategy outlined in Table 5. Anthony Danso‐Appiah (ADA) screened the results to identify potentially relevant trials, obtained the full trial reports and assessed the eligibility of trials for inclusion in the review using an eligibility form based on the inclusion criteria. Jürg Utzinger (JU) independently verified the eligibility assessment results.

ADA contacted the authors of potentially relevant trials for clarification if eligibility was unclear. We excluded studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria and we have detailed the reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies. This was verified independently by JU and Piero L. Olliaro (PLO). We resolved any discrepancies through discussion between the authors.

Data extraction and management

ADA extracted trial characteristics such as methods, participants, interventions and outcomes, and recorded on standard forms, which were independently verified by JU. ADA and JU resolved discrepancies through discussion, and where necessary contacted a third author (PLO). ADA contacted trial authors for clarification, or insufficient or missing data when necessary.

We extracted the number of participants randomized and the number of patients followed‐up in each treatment arm. For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants experiencing the event in each treatment group of the trial. For continuous outcomes summarized as geometric means, we extracted means and their standard deviations (SD) on the log scale. If the data were summarized as arithmetic mean, we extracted the means and their SDs. We extracted medians or ranges when they were reported to summarize the data.

For each outcome, we extracted data for each follow‐up time reported in the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

ADA assessed the risk of bias of each trial using The Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011) and the assessment results were verified independently by Dave Sinclair (DS). Where information in the trial report was unclear, we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification. We assessed the risk of bias for six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (investigators, outcome assessors and participants), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. For each domain, we made a judgment of 'low risk' of bias, 'high risk' of bias or 'unclear'. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion between the authors.

Measures of treatment effect

We presented dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios (RR). Mean differences (MD) were used as the measure of effect for continuous outcomes that were summarized as arithmetic means. We used geometric mean ratios for continuous outcomes that were summarized as geometric means. We presented all results with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Dealing with missing data

We analysed data based on the number of patients for whom an outcome was recorded (complete case analysis).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by inspecting the forest plots for overlapping CIs and outlying data; using the Chi2 test with a P value < 0.1 to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity; and using the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

We would have attempted to explore publication bias using funnel plots if there were sufficient number of trials in the comparisons.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager (RevMan) to perform the statistical analyses. We stratified the analyses by: comparison; the dose of the drug; and the length of follow‐up time. We used meta‐analysis to combine the results across trials. When heterogeneity was detected, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis approach; otherwise a fixed‐effect approach was adopted. We tabulated adverse events and also data that could not be meta‐analysed.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When heterogeneity was detected, we planned to carry out subgroup analyses to explore potential causes. Subgroupings would be as follows: patient age (children versus adults); and intensity of infection (< 500 eggs per gram of stool versus > 500 eggs per gram of stool).

We conducted a subsidiary, non‐randomized comparison of failure rates in children with failure rates in adults for the same drug and same dose (mg/kg) to explore issues around dose applicability in children.

Sensitivity analysis

Where data were sufficient we planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results to the risk of bias components.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 52 trials (10,269 participants) which met the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of included studies). We managed one multicentre trial carried out in Brazil, Mauritania and Tanzania as three separate trials in the analysis (Olliaro 2011 BRA; Olliaro 2011 MRT; Olliaro 2011 TZA), and three papers contained multiple individual studies which we again managed separately (de Clarke 1976a ZWE; de Clarke 1976b ZWE; de Clarke 1976c ZWE; de Clarke 1976d ZWE; Katz 1979a BRA; Katz 1979b BRA; Gryseels 1989a BDI; Gryseels 1989b BDI; Gryseels 1989c BDI).

Of the 52 trials we identified, 19 evaluated praziquantel, 17 evaluated oxamniquine and 12 directly compared praziquantel with oxamniquine. In addition, two compared myrrh (mirazid) with praziquantel, and two compared different brands of praziquantel.

Three trials assessed combination therapies: including praziquantel plus oxamniquine (Creasey 1986 ZWE; Zwingenberger 1987 BRA) and praziquantel plus artesunate (De Clercq 2000 SEN).

For the two primary outcomes, 47 trials reported cure rate or failure rate, 34 trials reported egg reduction rate and 33 trials reported both outcomes. Only Sukwa 1993 ZMB reported reinfection rate.

For secondary outcomes, five trials (Rugemalila 1984 TZA; Gryseels 1989a BDI; Gryseels 1989b BDI; Gryseels 1989c BDI; Sukwa 1993 ZMB) reported clinical improvement or functional indices, but we could not include Rugemalila 1984 TZA and Sukwa 1993 ZMB in the meta‐analysis because of insufficient information. Thirty‐three trials reported adverse events.

In the study by de Jonge 1990 SDN, we excluded the two arms that received metrifonate and placebo respectively from the analysis. Also, we excluded one arm of the study by Ibrahim 1980 SDN involving participants who did not have S. mansoni infection and also one arm each of the trials by Rugemalila 1984 TZA and Taylor 1988 ZWE that did not receive treatment from the analysis.

The trial by Tweyongyere 2009 UGA assessing the effects of praziquantel was a nested cohort study within a larger mother and baby cohort study in which pregnant women found to be infected with S. mansoni were randomized to receive praziquantel or placebo. We obtained data on parasitological failure rate and clinical improvement from figures (Gryseels 1989a BDI; Gryseels 1989b BDI; Gryseels 1989c BDI), but it was not possible to extract egg count data.

Trial setting and participants

The trials were conducted in Africa (n = 36), South America (n = 15; all in Brazil) and the Middle East (n = 1). Eight trials were conducted in the late 1970s, 28 in the 1980s, seven in the 1990s and only nine since the year 2000.

Eighteen trials involved children, 12 trials recruited adults, and 22 recruited whole populations comprising children, adolescents and adults.

Seventeen trials recruited participants from the outpatient clinics, six did not specify the setting whilst one trial (Omer 1981 SDN) consisted of both participants identified in a field survey and those attending the hospital; two trials (Katz 1979a BRA; Katz 1979b BRA) involved military officers in a Barracks who became exposed to the infection during training and another trial (Ibrahim 1980 SDN) recruited university students on campus. The remaining 25 trials recruited participants through community surveys.

Risk of bias in included studies

For risk of bias of included studies see the Characteristics of included studies and summary of the risk of bias graph (Figure 1) and risk of bias summary (Figure 2).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We considered 16 trials as low risk of bias with regard to the generation of the randomization sequence (Figure 2). In the remaining 36 trials, the methods used to generate the sequence of allocation were not described and therefore the risk of bias is unclear.

Fourteen trials adequately described allocation concealment and had a low risk of bias. One trial did not conceal allocation (Fernandes 1986 BRA); and the methods were unclear in the remaining 37 trials (Figure 2).

Blinding

Twenty‐seven trials employed blinding and stated who was blinded. However, none described the methods of blinding. Nevertheless, the studies were considered to be at low risk of bias. One trial did not employ blinding (Fernandes 1986 BRA) and we therefore classed it at high risk of bias; whereas in 25 trials blinding was unclear (Figure 2).

Incomplete outcome data

We considered the risk of bias for incomplete outcome data to be low in 17 trials (Figure 2). We deemed the risk of bias to be high in 19 trials, and in the remaining 16 trials as unclear.

Selective reporting

All 52 trials had low risk of selective outcome reporting (Figure 2).

Other potential sources of bias

Overall, 42 trials were considered to be free from other biases and the level of bias was unclear in the remaining 10 trials (Figure 2).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Section 1. Monotherapies

Praziquantel

Nineteen trials, conducted in Africa, Brazil and the Arabian Penunsula, evaluated praziquantel. Four studies compared praziquantel with placebo, and 17 trials directly compared different dosing schedules of praziquantel with the standard dose of 40 mg/kg.

Analysis 1: Praziquantel versus placebo

Parasitological failure

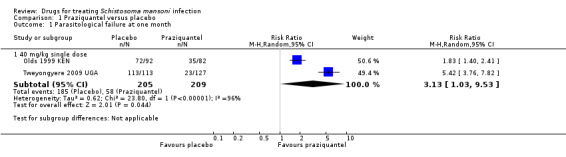

Two trials from Kenya and Uganda used the WHO recommended dose of 40 mg/kg. Praziquantel 40 mg/kg achieved parasitological cure in 57% and 82% of the patients respectively, compared to placebo where almost all continued to excrete eggs at one to two months (RR 3.13, 95% CI 1.03 to 9.53, two trials, 414 participants, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Praziquantel versus placebo, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

In addition, one small trial from Brazil compared three different doses of praziquantel with placebo and presented outcomes at six and 12 months. All patients given 40 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg praziquantel achieved parasitological cure at six months, while two out of five patients given 20 mg/kg and almost all those given placebo continued to excrete eggs (one trial, 40 participants, Analysis 1.2). At 12 months, reinfection was demonstrable in some of those given praziquantel (Analysis 1.3). One further trial from Brazil gave 60 mg/kg praziquantel each day for three days and achieved 100% parasitological cure at six months compared to almost complete failure with placebo (one trial, 55 participants, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Praziquantel versus placebo, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at six months.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Praziquantel versus placebo, Outcome 3 Parasitological failure at 12 months.

Egg reduction

None of these trials reported on percentage egg reduction.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were recorded in these trials but transient dizziness and abdominal pain appeared to be more commonly reported with praziquantel than placebo (seven trials, 1255 participants, Table 6).

2. Adverse events: Praziquantel versus placebo.

| Trial | No. of participants | Praziquantel dose | Remarks |

| Jaoko 1996 KEN | 436 | 40 mg/kg single dose | Adverse events described as minor and transient. Dizziness: Praziquantel 36% versus 6% control Abdominal pain 35% versus 14 % control |

| Katz 1979a BRA | 55 | 20 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in one day 60 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg three times in one day |

Adverse events were minor, did not differ between intervention and placebo groups, but were not reported separately for the different dose schedules. |

| Katz 1979b BRA | 61 | 50 mg/kg single dose 60 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg three times in one day |

Adverse events were minor, did not differ between the two intervention groups, but were not reported separately for the two dosing schedules. |

| Olds 1999 KEN | 174 | 40 mg/kg single dose | Abdominal pain: Praziquantel 80% versus 50% control Diarrhoea: Praziquantel 54% versus 25% control |

| Tweyongyere 2009 UGA | 387 | 40 mg/kg single dose | Adverse events were minor and transient. The authors pooled adverse events together over the intervention and placebo groups. Event rates were not reported. |

| Branchini 1982 BRA | 70 | 41.2 to 51.6 mg/kg single dose | No serious adverse events. Dizziness: Praziquantel 46.9% (control group not reported). Abdominal pain: Praziquantel 24.5% versus 17.6% control |

| Ferrari 2003 BRA | 72 | 180 mg/kg: 60 mg/kg once daily for three days | No serious adverse events. Events were mostly headache, dizziness, drowsiness and abdominal pain. Patients from the placebo group also reported having abdominal pain and drowsiness. |

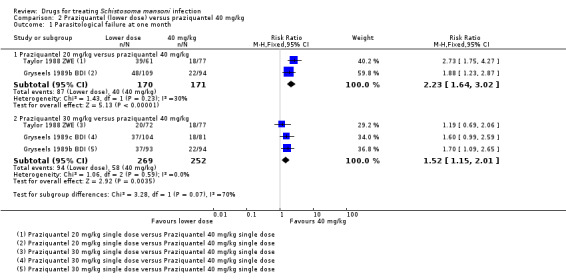

Analyses 2 and 3: Lower doses praziquantel versus 40 mg/kg

Parasitological failure

Lower doses (20 mg/kg to 30 mg/kg) have been evaluated in Zimbabwe, Burundi, Sudan and Brazil. Compared to 40 mg/kg, parasitological failure at one month was more than double with the 20 mg/kg dose, and 50% higher with the 30 mg/kg dose (20 mg/kg: RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.64 to 3.02, two trials, 341 participants; 30 mg/kg: RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.01, three trials, 521 participants; Analysis 2.1). Follow‐up at three months (Analysis 2.2) and at six to 12 months showed a similar pattern (Analysis 2.3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel (lower dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel (lower dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at three months.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel (lower dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 3 Parasitological failure at six to 12 months.

Egg reduction

In one trial from Brazil evaluating 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg, geometric mean egg reductions were high in both groups, at six months (92.5% versus 97.7%, statistical significance not reported (one trial, 138 participants, Analysis 2.4)).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel (lower dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Percent egg reduction.

| Percent egg reduction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Geometric mean % egg reduction at 6 months 30 mg/kg | Geometric mean % egg reduction at 6 months 40 mg/kg | P‐value | Comment |

| Katz 1981 BRA | 138 | 92.5% | 97.7% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

Symptom resolution

One trial compared a lower dose of praziquantel at 20 mg/kg with 40 mg/kg and showed no difference in resolving symptoms at three, six, 12 and 24 months of follow‐up: diarrhoea (one trial, 44 participants, Analysis 3.3), blood in stool (one trial, 37 participants, Analysis 3.5), hepatomegaly (one trial, 55 participants, Analysis 3.7) and splenomegaly (one trial, 73 participants, Analysis 3.9), except one study that showed that 40 mg/kg significantly improved abdominal pain at one month (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.98, one trial, 169 participants, Analysis 3.1).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 3 Resolution of diarrhoea: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 5 Resolution of blood in stool: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 7 Resolution of hepatomegaly: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 9 Resolution of splenomegaly: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Resolution of abdominal pain: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

Two trials compared 30 mg/kg with 40 mg/kg and did not show any difference in resolving symptoms at one, three, six, 12 and 24 months of follow‐up: abdominal pain (two trials, 318 participants, Analysis 3.2), diarrhoea (two trials, 48 participants, Analysis 3.4), blood in stool (two trials, 82 participants, Analysis 3.6), hepatomegaly (two trials, 109 participants, Analysis 3.8) and splenomegaly (two trials, 122 participants, Analysis 3.10).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 2 Resolution of abdominal pain: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Resolution of diarrhoea: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 6 Resolution of blood in stool: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 8 Resolution of hepatomegaly: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Praziquantel lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 10 Resolution of splenomegaly: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

Adverse events

In the three trials reporting adverse events, consistent differences in frequency or severity between 20, 30 and 40 mg/kg doses have not been shown (three trials, 319 participants, Table 7).

3. Adverse events: praziquantel (lower dose) versus 40 mg/kg.

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| Katz 1979a BRA | 28 | 20 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in one day |

No serious adverse events. Minor adverse events, did not differ between intervention and control groups. |

| Katz 1981 BRA | 138 | 30 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse events. Minor adverse events (lower dose first): Abdominal pain: 42.6% versus 44.4% Giddiness: 14.9% versus 26.7% |

| Omer 1981 SDN | 153 | 30 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse events. Diarrhoea, vomiting, nausea and abdominal pain were commonly reported but these were transient. |

Analysis 4: Higher doses praziquantel versus 40 mg/kg

Parasitological failure

Higher doses (50 mg/kg to 60 mg/kg) have been evaluated in Brazil (three trials), Mauritania, Senegal and Tanzania. Compared to 40 mg/kg, parasitological failure has not been shown to be improved with higher doses at one month (five trials, 783 participants, Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Praziquantel (higher dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

Egg reduction

Among participants still excreting eggs, percentage egg reductions were similar in both groups at one month (four trials, 786 participants, Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Praziquantel (higher dose) versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Percent egg reduction at one month.

| Percent egg reduction at one month | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Praziquantel (60 mg/kg) | Praziquantel (40 mg/kg) | P‐value | Comment |

| Guisse 1997 SEN | 130 | 99% | 99% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Olliaro 2011 BRA | 196 | 91.8% | 91.7% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs and those not excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Olliaro 2011 MRT | 186 | 89.6% | 89.2% | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG of participants excreting eggs and those not excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Olliaro 2011 TZA | 271 | 92.3% | 91.9% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs and those not excreting eggs at follow‐up |

Adverse events

One multi‐country trial reported adverse events and recorded one serious event (a seizure) with the higher dose. At the trial site in Brazil, non‐severe adverse events appeared to be more common with the higher dose but this was not seen consistently at the trial sites in Mauritania or Tanzania (one trial, 653 participants, see Table 8).

4. Adverse events: praziquantel (higher dose) versus 40 mg/kg.

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| Olliaro 2011 BRA | 196 | 60 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse event. Minor adverse events (highest dose first): Abdominal pain: 48 versus 47.9% Nausea: 20.4% versus 18.4% Dizziness: 20.4% versus 11.2% Headache: 14.3% versus 12.2% Vomiting: 11.2% versus 5.19% Diarrhoea: 8.2% versus 4.1% Rarely sleepiness was also reported. |

| Olliaro 2011 MRT | 186 | 60 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

One incidence of serious event was recorded in the higher dose (60 mg/kg). The rest of the events were minor. Transient dizziness, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting and headache were commonly reported (highest dose first): Dizziness: 77.8% versus 9.7% Abdominal pain:79.6% versus 71.0% Diarrhoea: 41.9% versus 49.5% Vomiting: 10.7% versus 32.3% Headache: 9.7% versus 14.0% |

| Olliaro 2011 TZA | 271 | 60 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

Minor adverse events (highest dose first): Abdominal pain: 88.9% versus 83.8% Diarrhoea: 47.4% versus 49.3% Nausea: 26.7% versus 30.9% Headache: 14.1% versus 9.6% Vomiting: 11.1% versus 16.9% Dizziness: 6.7% versus 9.6% Fever: 0% versus 1.5%. |

Analysis 5: Split dose praziquantel versus 40 mg/kg in a single dose

Splitting 40 mg/kg into divided doses given on the same day was evaluated in the 1980s in three trials in Sudan.

Parasitological failure

At one month, two trials did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit with the split dose regimen compared to a single 40 mg/kg dose (two trials, 525 participants, Analysis 5.1), but showed benefit at three months (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.53, two trials, 516 participants, Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Praziquantel 40 mg/kg divided dose versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Praziquantel 40 mg/kg divided dose versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at three months.

One further small trial, only reported the outcome at six months and found no difference (one trial, 64 participants, Analysis 5.3).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Praziquantel 40 mg/kg divided dose versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose, Outcome 3 Parasitological failure at six months.

Egg reduction

In the only trial reporting egg count, the mean percent reduction at one month was higher with the divided dose but statistical significance was not reported (divided dose 93.2% versus single dose 86.5%, one trial, 350 participants, Analysis 5.4).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Praziquantel 40 mg/kg divided dose versus praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose, Outcome 4 Percent egg reduction at one month.

| Percent egg reduction at one month | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Praziquantel (40 mg/kg) in a divided dose of 20 mg/kg | Praziquantel (40 mg/kg) single dose | P‐value | Comment |

| Kardaman 1983 SDN | 350 | 93.2% | 86.5% | P > 0.1 | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in these trials. Only one trial reported the frequency of adverse events in each treatment group (Kardaman 1983 SDN). Mild abdominal pain and diarrhoea were less common when the dose was given in divided doses but vomiting was more common (one trial, 350 participants, Table 9).

5. Adverse events: praziquantel (40 mg/kg in a divided dose) versus praziquantel (40 mg/kg) single dose.

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| Kardaman 1983 SDN | 350 | 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in a day 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse events. Events were transient (divided dose first): Abdominal pain: 13.5% versus 24.6% Vomiting: 7.6% versus 4% Diarrhoea: 7.6% versus 12.8% |

| Omer 1981 SDN | 306 | 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in a day 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse events. Adverse events were transient and required no additional intervention. |

Analysis 6: Other praziquantel dosing regimens

Several trials from Brazil have evaluated higher praziquantel dosing regimens with 30 mg/kg to 60 mg/kg given for up to six days (see Analysis 6.1). It is difficult to draw conclusions from these studies as the comparator dose is also a non‐standard regimen, but one trial did demonstrate improved parasitological cure rates with prolonged courses given over three to six days compared to courses lasting one day.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Praziquantel alternative dosing (Brazil), Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at six months.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in these trials, events were mainly transient dizziness and nausea (one trial, 79 participants, Table 10).

6. Adverse events: praziquantel alternative dosing (Brazil).

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| da Cunha 1987 BRA | 79 | 180 mg/kg: 30 mg/kg twice daily for three days 180 mg/kg: 30 mg/kg daily for six days 120 mg/kg: 30 mg/kg twice daily for two days 60 mg/kg: 30 mg/kg twice in one day |

No serious adverse events. Minor and transient events (highest dose first): Dizziness: 65%, 15%, 45% versus 15% Nausea: 55%, 15, 20% versus 20% |

Oxamniquine

Seventeen trials evaluated oxamniquine, with the most recent conducted in the 1980s. Oxamniquine has since fallen out of use in favour of praziquantel. Four trials compared oxamniquine with placebo and 12 trials directly compared different dosing schedules of oxamniquine in different geographical locations in Africa and Brazil. The most common comparator dose was 40 mg/kg.

Analysis 7: Oxamniquine versus placebo

Parasitological failure

In two trials in Brazil, 20 mg/kg was significantly superior to placebo at longer timepoints (RR 3.68, 95% CI 2.53 to 5.36, two trials, 146 participants, Analysis 7.2). In two trials from Ethiopia, oxamniquine achieved parasitological cure rates of > 75% with 30, 40, and 60 mg/kg at three to four months, compared to placebo where almost all participants continued to excrete eggs (30 mg/kg: RR 4.34, 95% CI 2.47 to 7.65, two trials, 82 participants; 40 mg/kg: RR 8.74, 95% CI 3.74 to 20.43, two trials, 82 participants; 60 mg/kg: RR 19.38, 95% CI 5.79 to 64.79, two trials, 89 participants; Analysis 7.1).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oxamniquine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at six to 10 months.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oxamniquine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at three to four months.

Egg reduction

Among those still excreting eggs at three to four months, two trials from Ethiopia reported significant reductions in egg numbers in those given oxamniquine (68.1% to 100%), compared to increases of 59 to 80.6% in the placebo groups (two trials, 227 participants, Analysis 7.3).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oxamniquine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Percent egg reduction at three to four months.

| Percent egg reduction at three to four months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Intervention | Placebo | p‐value | Comment |

| Oxamniquine (40 mg/kg) versus placebo | |||||

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 100% | 59% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 162 | 42.7% | 80.6% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Oxamniquine (20 to 30 mg/kg) versus placebo | |||||

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 73.7% | 59% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 162 | 68.1% | 80.6% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Oxamniquine (60 mg/kg) versus placebo | |||||

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 100% | 59% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 162 | 82% | 80.6% increase | Not reported | Geometric mean EPG based on participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in these trials. Dizziness was more commonly reported with oxamniquine than placebo but is described as transient, with most resolving within 24 hours (five trials, 425 participants, Table 11).

7. Adverse events: oxamniquine versus placebo.

| Trial | No. of participants | Oxamniquine dose | Remarks |

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for two days 40 mg/kg: 10 mg/kg twice daily for two days 30 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice in one day |

Adverse events were minor and transient. Dizziness: Oxamniquine (15 mg/kg BD for 2 days) 50% versus 38.9% (10 mg/kg BD for two days) versus 30% control. |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 128 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for two days 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in one day 30 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice in one day |

All the doses were well tolerated and accepted. Dizziness was the most frequently reported complaint, but this was mild and transient. |

| Lambertucci 1982 BRA | 91 | 20 mg/kg single dose | Adverse events were minor and transient. Dizziness: Oxamniquine 14.6% versus 2.8% control Nausea: Oxamniquine 14.6% versus 5.6% control. |

| Branchini 1982 BRA | 71 | 14 mg/kg single dose | Adverse events were few and minor. Dizziness: Oxamniquine 44.2% (control not reported) Abdominal pain: Oxamniquine 11.5% versus 17.6% control. |

| Ferrari 2003 BRA | 70 | 20 mg/kg: 10 mg/kg twice in one day | No serious adverse events. Adverse events were mild, mostly headache, dizziness, drowsiness and abdominal pain. Patients from the placebo group also had abdominal pain and drowsiness. |

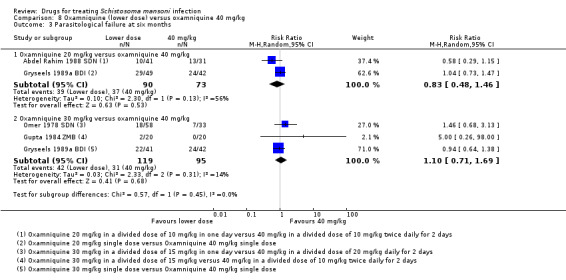

Analyses 8 and 9: Lower doses oxamniquine versus 40 mg/kg

Lower doses of oxamniquine (20 to 30 mg/kg) have been compared to 40 mg/kg in Ethiopia (two trials), Sudan (two trials), Zimbabwe (two trials), Burundi and Malawi.

Parasitological failure

Compared to 40 mg/kg, both 20 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg of oxamniquine resulted in significantly more parasitological failures at one month (20 mg/kg: RR 3.78, 95% CI 2.05 to 6.99, two trials, 190 participants; 30 mg/kg: RR 1.78, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.75, four trials, 268 participants, Analysis 8.1), and at three to four months (20 mg/kg: RR 2.28, 95% CI 1.40 to 3.71, three trials, 209 participants; 30 mg/kg: RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.43, seven trials, 373 participants, Analysis 8.2).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oxamniquine (lower dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oxamniquine (lower dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at three to four months.

At later time points, no statistically significant differences were shown: six months (20 mg/kg: two trials, 163 participants; 30 mg/kg: three trials, 214 participants, Analysis 8.3) and 12 months (20 mg/kg: two trials, 144 participants; 30 mg/kg: one trial, 77 participants, Analysis 8.4).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oxamniquine (lower dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 3 Parasitological failure at six months.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oxamniquine (lower dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Parasitological failure at 12 months.

Egg reduction

Percent egg reduction was evaluated in six of these trials and both lower dose and 40 mg/kg showed a wide range of benefit at one, three and six months: lower dose (57.1% to 99%) and 40 mg/kg (42.7 to 100%) (six trials, 878 participants, Analysis 8.5).

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oxamniquine (lower dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 5 Percent egg reduction.

| Percent egg reduction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Dose (mg/kg) | Oxamniquine (lower dose) | Oxamniquine (40 mg/kg) | P‐value | Comment |

| One month | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 20 | 81.7% | 80% | No significant difference with H‐ and Wilcoxon‐tests | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 30 | 93.6% | 78.8% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 119 | 30 | 99.4% | 99.1% | Not statistically significant | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Three to four months | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 20 | 78.1% | 67.5% | Not statistically significant with H‐ and Wilcoxon‐ tests | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 30 | 73.7% | 100% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 162 | 30 | 68.1 | 42.7% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 30 | 93.6% | 99.4% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 119 | 30 | 97.6% | 99.1% | Not statistically significant | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Six months | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 20 | 57.1% | 56.8% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 30 | 95.2% | 100% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Omer 1978 SDN | 176 | 30 | 84% | 89% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

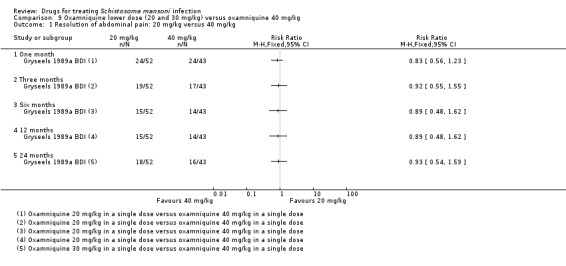

Symptom resolution

One trial compared a lower dose of 20 mg/kg oxamniquine with 40 mg/kg and did not find any difference between the two doses in resolving symptoms at one, three, six, 12 and 24 months of follow‐up: abdominal pain (one trial, 95 participants, Analysis 9.1), diarrhoea (one trial, 16 participants, Analysis 9.3), blood in stool (one trial, 85 participants, Analysis 9.5), hepatomegaly (one trial, 64 participants, Analysis 9.7) and splenomegaly (one trial, 69 participants, Analysis 9.9).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Resolution of abdominal pain: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 3 Resolution of diarrhoea: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 5 Resolution of blood in stool: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.7. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 7 Resolution of hepatomegaly: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.9. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 9 Resolution of splenomegaly: 20 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

Also, 30 mg/kg did not show any difference statistically compared with 40 mg/kg in resolving symptoms at one, three, six, 12 and 24 months of follow‐up: abdominal pain (one trial, 95 participants, Analysis 9.2), diarrhoea (one trial, 15 participants, Analysis 9.4), blood in stool (one trial, 41 participants, Analysis 9.6), hepatomegaly (one trial, 51 participants, Analysis 9.8) and splenomegaly (one trial, 54 participants, Analysis 9.10).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 2 Resolution of abdominal pain: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Resolution of diarrhoea: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 6 Resolution of blood in stool: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 8 Resolution of hepatomegaly: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

9.10. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oxamniquine lower dose (20 and 30 mg/kg) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 10 Resolution of splenomegaly: 30 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg.

Adverse events

Six trials from Ethiopia (two trials), and one trial each from Malawi, Sudan, Zambia and Zimbabwe assessed adverse events and reported no serious events. Dizziness was most commonly reported, but the event rate and severity did not differ between doses (six trials, 508 participants, Table 12).

8. Adverse events: oxamniquine (lower dose) versus 40 mg/kg.

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 55 | 30 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice in one day. | No serious adverse events were reported. Transient dizziness and nausea were commonly reported (lower dose first): Dizziness: 38.9% versus 42% Nausea: 22.2% versus 26.3% A few mild headaches and abdominal pain were also reported. |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 96 | 30 mg/kg:15 mg/kg twice in one day. | All doses were well tolerated and no serious event was recorded. Dizziness was more commonly reported, but this was transient. |

| de Clarke 1976b ZWE | 26 | 20 mg/kg: 5 x 2 mg/kg daily for two days 30 mg/kg: 7.5 x 2 mg/kg daily for two days. |

No serious adverse events were recorded. Transient dizziness was more commonly reported and very rarely headache, nausea, and vomiting. Adverse events did not differ between dose. |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 30 mg/kg:15 mg/kg twice in one day 40 mg/kg: 10 mg/kg twice daily for two days |

No serious events were reported. Adverse events were mainly dizziness and nausea, but were minor and transient (lower dose first): Dizziness: 20% versus 25% Nausea: 15% versus 30% A few events of vomiting, headache and abdominal pain were also reported. |

| Omer 1978 SDN | 176 | 30 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice in one day 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg daily for 2 days |

No serious adverse events were recorded. Asthenia (weakness) was reported among a few receiving 40 mg/kg, but this did not require additional intervention. Transient dizziness was more commonly reported (lower dose first) Dizziness: 3% versus 8% Minor abdominal pain, headache and vomiting also reported. |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 95 | 20 mg/kg single dose 30 mg/kg single dose |

Noserious adverse events were recorded. Transient dizziness, nausea and vomiting were most commonly reported. |

Analysis 10: Higher doses oxamniquine versus 40 mg/kg

Higher doses of oxamniquine (50 mg/kg to 60 mg/kg) have been compared to 40 mg/kg in six trials from three countries; Sudan (three trials), Ethiopia (two trials) and Zambia (one trial).

Parasitological failure

Higher doses of oxamniquine have not shown consistent statistically significant benefits over 40 mg/kg at one month (five trials, 349 participants, Analysis 10.1), at three to four months (six trials, 397 participants, Analysis 10.2), or six months (two trials, 177 participants, Analysis 10.3).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxamniquine (higher dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure at one month.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxamniquine (higher dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 2 Parasitological failure at three to four months.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxamniquine (higher dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 3 Parasitological failure at six months.

Losses to follow‐up were high in the trial investigating 50 mg/kg, reaching 76.9% at three months, and heterogeneity between the trials was significant (I2= 64% to 82%).

Egg reduction

Seven trials evaluated egg count and reported a wide range of percent mean reductions among those not cured at one month (86% to 100% versus 56% to 99.1%, four trials, 561 participants, Analysis 10.4), three to four months (82% to 100% versus 42% to 100%, six trials, 791 participants, Analysis 10.4) and six months (62.% to 100% versus 75% to 100%, four trials, 561 participants, Analysis 10.4).

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oxamniquine (higher dose) versus oxamniquine 40 mg/kg, Outcome 4 Percent egg reduction.

| Percent egg reduction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Dose (mg/kg) | Oxamniquine (higher dose) | Oxamniquine (40 mg/kg) | P‐value | Comment |

| One month | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 60 | 95.7% | 80% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 60 | 100% | 78.8% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Ibrahim 1980 SDN | 89 | 60 | 86% | 56% | Not reported | EPG (Arithmetic Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 119 | 50 | 99.9% | 99.1% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Three to four months | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 60 | 89.7% | 67.5% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 65 | 60 | 100% | 100% | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up | |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 162 | 60 | 82% | 42.7% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 60 | 100% | 99.4% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Ibrahim 1980 SDN | 89 | 60 | 92% | 65% | Not reported | EPG (Arithmetic Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 119 | 50 | 99.5% | 99.1% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Six months | ||||||

| Abdel Rahim 1988 SDN | 296 | 60 | 62.1% | 56.8% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 60 | 100% | 100% | Not reported | Not reported how EPG was calculated |

| Ibrahim 1980 SDN | 89 | 60 | 97% | 75% | Not reported | EPG (Arithmetic Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

| Omer 1978 SDN | 176 | 60 | 93% | 89% | Not reported | EPG (Geometric Mean) of participants excreting eggs at follow‐up |

Adverse events

In five trials reporting adverse events, no serious events were recorded. Dizziness and nausea were most commonly reported, but these were transient and did not require additional interventions (one trial, 482 participants, Table 13).

9. Adverse events: oxamniquine (higher dose) versus 40 mg/kg.

| Trial | No. of participants | Comparison | Remarks |

| Ayele 1984 ETH | 55 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for two days 40 mg/kg: 10 mg/kg twice daily for two days |

No serious adverse event was recorded. Dizziness and nausea were commonly reported but these were transient (higher dose first): Dizziness: 50% versus 42% Nausea: 11% versus 26.3% A few mild headaches and abdominal pain were also reported. |

| Ayele 1986 ETH | 96 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for 2 days 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg twice in one day |

No serious adverse events were recorded. Dizziness was more commonly reported, but this was transient and did not differ between dose. |

| Gupta 1984 ZMB | 60 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for two days 40 mg/kg: 10 mg/kg twice for daily for two days |

No serious events were reported. Transient dizziness and nausea were more commonly reported (higher dose first): Dizziness: 40% versus 25% Nausea: 25% versus 30% A few events of vomiting, headache and abdominal pain were also reported. |

| Omer 1978 SDN | 176 | 60 mg/kg: 15 mg/kg twice daily for 2 days 40 mg/kg: 20 mg/kg daily for 2 days |

No serious adverse events was recorded. Transient dizziness was more commonly reported (higher dose first): Dizziness: 15% versus 8% Few minor abdominal pain, headache and vomiting were also reported. |

| Teesdale 1984 MWI | 95 | 50 mg/kg single dose 40 mg/kg single dose |

No serious adverse events was recorded. Transient dizziness, nausea and vomiting were most commonly reported and did not differ between dose. |

Analyses 11 and 12: Other oxamniquine dosing regimes

Nine additional trials compared 30 mg/kg oxamniquine with higher and lower doses in Ethiopia (three trials), Zimbabwe (two trials), Burundi (one trial), Nigeria (one trial), Sudan (one trial) and Zambia (one trial).

Lower doses versus 30 mg/kg

Compared to 30 mg/kg, parasitological failure was higher with 15 mg/kg to 20 mg/kg oxamniquine at one month (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.74, two trials, 230 participants), and at three to four months (RR 2.16, 95% CI 1.40 to 3.32, four trials, 249 participants, Analysis 11.1).

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oxamniquine (lower dose) 15 to 20 mg/kg versus oxamniquine 30 mg/kg, Outcome 1 Parasitological failure.

At later follow‐up times, no statistically significant difference were demonstrated (six months: two trials, 179 participants; and 12 months: one trial, 95 participants, Analysis 11.1).

Higher doses versus 30 mg/kg