Abstract

Background

Infection with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) bacteria is a common cause of diarrhoea in adults and children in developing countries and is a major cause of 'travellers' diarrhoea' in people visiting or returning from endemic regions. A killed whole cell vaccine (Dukoral®), primarily designed and licensed to prevent cholera, has been recommended by some groups to prevent travellers' diarrhoea in people visiting endemic regions. This vaccine contains a recombinant B subunit of the cholera toxin that is antigenically similar to the heat labile toxin of ETEC. This review aims to evaluate the clinical efficacy of this vaccine and other vaccines designed specifically to protect people against diarrhoea caused by ETEC infection.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of vaccines for preventing ETEC diarrhoea.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Disease Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and http://clinicaltrials.gov up to December 2012.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing use of vaccines to prevent ETEC with use of no intervention, a control vaccine (either an inert vaccine or a vaccine normally given to prevent an unrelated infection), an alternative ETEC vaccine, or a different dose or schedule of the same ETEC vaccine in healthy adults and children living in endemic regions, intending to travel to endemic regions, or volunteering to receive an artificial challenge of ETEC bacteria.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed each trial for eligibility and risk of bias. Two independent reviewers extracted data from the included studies and analyzed the data using Review Manager (RevMan) software. We reported outcomes as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Twenty‐four RCTs, including 53,247 participants, met the inclusion criteria. Four studies assessed the protective efficacy of oral cholera vaccines when used to prevent diarrhoea due to ETEC and seven studies assessed the protective efficacy of ETEC‐specific vaccines. Of these 11 studies, seven studies presented efficacy data from field trials and four studies presented efficacy data from artificial challenge studies. An additional 13 trials contributed safety and immunological data only.

Cholera vaccines

The currently available, oral cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Dukoral®) was evaluated for protection of people against 'travellers' diarrhoea' in a single RCT in people arriving in Mexico from the USA. We did not identify any statistically significant effects on ETEC diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea (one trial, 502 participants, low quality evidence).

Two earlier trials, one undertaken in an endemic population in Bangladesh and one undertaken in people travelling from Finland to Morocco, evaluated a precursor of this vaccine containing purified cholera toxin B subunit rather than the recombinant subunit in Dukoral®. Short term protective efficacy against ETEC diarrhoea was demonstrated, lasting for around three months (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.71; two trials, 50,227 participants). This vaccine is no longer available.

ETEC vaccines

An ETEC‐specific, killed whole cell vaccine, which also contains the recombinant cholera toxin B‐subunit, was evaluated in people travelling from the USA to Mexico or Guatemala, and from Austria to Latin America, Africa, or Asia. We did not identify any statistically significant differences in ETEC‐specific diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 799 participants), and the vaccine was associated with increased vomiting (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.45; nine trials, 1528 participants). The other ETEC‐specific vaccines in development have not yet demonstrated clinically important benefits.

Authors' conclusions

There is currently insufficient evidence from RCTs to support the use of the oral cholera vaccine Dukoral® for protecting travellers against ETEC diarrhoea. Further research is needed to develop safe and effective vaccines to provide both short and long‐term protection against ETEC diarrhoea.

23 April 2019

No update planned

Other

This is not a current question.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Humans; Cholera Toxin; Cholera Toxin/adverse effects; Cholera Toxin/immunology; Cholera Vaccines; Cholera Vaccines/adverse effects; Cholera Vaccines/therapeutic use; Developing Countries; Diarrhea; Diarrhea/microbiology; Diarrhea/prevention & control; Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli; Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli/immunology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Travel; Vaccines, Inactivated; Vaccines, Inactivated/adverse effects; Vaccines, Inactivated/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Vaccines for preventing diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli bacteria

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is a type of bacteria that can infect both children and adults, causing diarrhoea. In particular, it affects people in developing countries. However, it is also a major cause of 'travellers' diarrhoea' in people visiting or returning from regions where this infection is common. It is transmitted from person to person by eating or drinking unclean food or water. Typically it causes watery diarrhoea, with abdominal pains and vomiting, that can last for several days. Vaccines are being considered as a way to prevent diarrhoea caused by ETEC bacteria. ETEC bacteria share some similarities with the bacteria that cause cholera. In this review, we examined the effectiveness of either vaccines designed to prevent cholera or vaccines designed specifically to prevent ETEC infection for preventing ETEC diarrhoea. We compared these vaccines against the use of a control vaccine (either an inert vaccine or a vaccine normally given to prevent an unrelated infection), no intervention, an alternative ETEC vaccine, or a different dose or schedule of the same ETEC vaccine.

We examined the research published up to 07 December 2012. We included 24 randomized controlled trials and 53,247 participants in this review. Four studies assessed the use of oral cholera vaccines to prevent diarrhoea caused by ETEC and eight trials assessed the use of ETEC‐specific vaccines to prevent diarrhoea. Seven studies presented data from field trials and four studies presented data from studies where people were artificially infected with ETEC bacteria. Also, 13 trials gave safety and immunological data only.

There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of the oral cholera vaccine Dukoral® to protect travellers against ETEC diarrhoea. Based on a single trial in people travelling from the USA to Mexico, the oral cholera vaccine Dukoral® may have little or no effect in preventing ETEC diarrhoea (one trial, 502 participants, low quality evidence). Two earlier trials, one undertaken in an endemic population in Bangladesh and one undertaken in people travelling from Finland to Morocco, evaluated a precursor of the oral cholera vaccine Dukoral®. Short term protection against ETEC diarrhoea was demonstrated, lasting for around three months (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.71; two trials, 50,227 participants). However, this vaccine is no longer available.

An ETEC‐specific, killed whole cell vaccine, which also contains the recombinant cholera toxin B‐subunit, was evaluated in people travelling from the USA to Mexico or Guatemala, and from Austria to Latin America, Africa, or Asia. There were no statistically significant differences in ETEC‐specific diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 799 participants) found and the vaccine was associated with increased vomiting (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.45; nine trials, 1528 participants). The other ETEC‐specific vaccines in development have not yet demonstrated clinically important benefits. Further research is needed to develop safe and effective vaccines to provide both short and long‐term protection against ETEC diarrhoea.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cholera WC‐rCTB vaccine for preventing enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) diarrhoea.

| Cholera killed whole cells plus recombinant B‐subunit vaccine for enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) diarrhoea | ||||||

| Patient or population: People travelling from non‐endemic settings Settings: Endemic settings Intervention: Cholera killed whole cells plus recombinant B‐subunit vaccine (WC‐rCTB Cholera) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Vaccine | |||||

| ETEC diarrhoea | 99 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (72 to 198) | RR 0.93 (0.61 to 1.41) | 502 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,4 | |

| Severe ETEC diarrhoea | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| All‐cause diarrhoea | 492 per 1000 | 512 per 1000 (428 to 610) | RR 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24) | 502 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4,5 | |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 502 (1 study) | 6 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 This single study was conducted in adults travelling from the USA to Mexico (Scerpella 1995). Although the paper does not clearly describe the methods used to prevent selection bias, we have not downgraded the evidence as selection bias is probably unlikely in a trial where everyone is healthy at enrolment. 2 Two older trials evaluated a prototype of this vaccine which contained purified cholera B‐subunit rather than the recombinant subunit contained in this vaccine. Although both trials found some evidence of benefit, the evidence may no longer be applicable due to changes in both composition and dosing of the vaccine. 3 Downgraded by one for indirectness: in this study the vaccine was provided in two doses 10 days apart after the travellers had arrived in Mexico. Most cases of ETEC diarrhoea occurred between doses or within seven days of administration of the second dose. The authors conducted a subgroup analysis of only those participants who had diarrhoea > 7 days after the second dose, which excluded 75% of cases. We did not find a statistically significant difference in our analysis of this data. 4 Downgraded by one for imprecision: this trial was small and underpowered to reliably prove or exclude a clinically important effect with the vaccine. 5 Downgraded by one for indirectness: in this study the vaccine was provided in two doses 10 days apart after the travellers had arrived in Mexico. Further studies are required which assess administration prior to travel to a variety of destinations. 6Scerpella 1995 reported no differences in the frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, or febrile illnesses between vaccinees, or placebo recipients but data were not presented.

Background

Description of the condition

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is the most common bacterial cause of diarrhoea in adults and children in developing countries (Qadri 2005; Walker 2007). The annual incidence of this disease is highest in young children and susceptibility to the disease declines with age. Children born in endemic regions are likely to experience two to three episodes of ETEC diarrhoea before their fifth birthday (Wennerås 2004). The practical difficulties associated with making an accurate diagnosis of ETEC in low‐resource settings mean that its significance has often been underestimated (Wennerås 2004; Qadri 2005). However, a review of microbiological studies conducted in endemic regions between 1992 and 2000 found that ETEC was the causative organism in approximately 25% of all diarrhoeal episodes in children aged between one and four years (Wennerås 2004). Many more children were shown to carry the organism asymptomatically in their gut (Walker 2007). A global burden of approximately 280 million clinical episodes and 380,000 deaths annually are estimated (WHO 2009).

Person‐to‐person transmission of ETEC occurs via ingestion of faecally‐contaminated food or water. In developed countries where sanitation standards are usually higher, ETEC infection is rare. However, it remains a major cause of 'travellers' diarrhoea' which occurs in people visiting or returning from ETEC‐endemic regions (Qadri 2005; DuPont 2008; Widermann 2009). Epidemics of ETEC diarrhoea have also occurred during natural disasters, such as floods, where there has been an acute deterioration in the quality of drinking water and sanitation (Schwartz 2006; Harris 2008).

The clinical illness is characterized by a profuse watery diarrhoea that lasts for several days and may be associated with abdominal cramp, malaise, vomiting, and a low grade fever. Without adequate treatment this can lead to dehydration. If people have a prolonged infection or are infected again, this can lead to malnutrition or growth inhibition in young children (Black 1984; Qadri 2005; Qadri 2007).

Following ingestion, ETEC bacteria adhere to the lining of the gut and secrete either one or both types of enterotoxins: the heat labile toxin (LT) and the heat stable toxin (ST). These toxins induce the hypersecretion of fluids and electrolytes, which cause the typical watery diarrhoea (Gill 1980). Different strains of ETEC can be further characterized on the basis of the antigens expressed on the cell surface: the colonization factor (CF), and the 'O' and 'H' antigens (Wolf 1997). Some of these antigens have been shown to be important in inducing natural immunity and therefore represent key targets for vaccine development (Rao 2005; Svennerholm 2008). Over 100 different "O'' antigens can be present on ETEC and therefore have not been considered important for vaccine development. Since both antitoxic and antibacterial antibodies are important for protection, most vaccine formulations have been based on the enterotoxins and CFs of ETEC (Svennerholm 1984; Ahren 1998). Important antigens considered until now for vaccine development include the LT and CFs. Over 25 CFs that have been characterized and most common CFs present on clinical isolates include CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS3, CS5, and CS6. These CFs have been included as vaccine antigens on ETEC vaccines to date (Harro 2011; Tobias 2011; Tobias 2012).

Improvements in public health and sanitation conditions represent the ideal solution to preventing transmission of ETEC and other faecally‐transmitted organisms. However, this can be difficult to achieve given the financial and logistical constraints in low‐resource regions. Thus prophylactic measures, including vaccines, are being considered as alternative short‐term strategies (Walker 2007).

Description of the intervention

Only one vaccine (Dukoral® produced by SBL Sweden) is currently available for the prevention of ETEC diarrhoea. This vaccine has been recommended to prevent 'travellers' diarrhoea' in people visiting endemic regions from developed countries (Steffen 2005). This vaccine is primarily designed and licensed to prevent diarrhoea due to Vibrio cholerae (cholera), but it contains a recombinant B subunit of the cholera toxin that is antigenically very similar to the LT of ETEC (Walker 2007). In an early clinical trial, using a prototype of this vaccine which contained purified cholera B subunit rather than the recombinant form, significant cross protection against ETEC diarrhoea was demonstrated (Clemens 1988).

Many alternative vaccine candidates designed specifically to protect people against ETEC diarrhoea are now at various stages of clinical development (Table 2). The vaccine candidates can be broadly categorized in to two groups: inactivated vaccines containing killed whole cells, purified CF antigens, or inactivated LT; and live attenuated vaccines containing genetically modified, non‐pathogenic strains of ETEC, or alternative carrier bacteria expressing the important ETEC antigens (Svennerholm 2008). Given the number of antigenically different strains of ETEC, it is likely that a vaccine formulation capable of providing broad protection would need to contain a combination of the most commonly expressed antigens (Walker 2007; Svennerholm 2008).

1. Currently available and experimental ETEC vaccines.

Oral inactivated vaccines

|

Oral live attenuated vaccines

|

Other ETEC vaccines under development include

|

WC/rCTB: whole cell/recombinant cholera toxin B subunit; ETEC: enterotoxigenic E. coli; CFA: colonization factor antigen; CS: E. coli surface antigen; LT: heat labile toxin; CT: cholera toxin; LTB/ST: heat labile toxin B subunit/heat stable toxin.

How the intervention might work

Epidemiological and experimental data suggest that natural immunity to ETEC does occur following natural infection and antibodies against CF antigens and the B subunit of LT have been detected (Qadri 2005; Rao 2005). Vaccine candidates aim to induce similar immunity (without the associated clinical illness) and to provide lasting protection against a broad range of the pathogenic ETEC strains (Svennerholm 2008). Attempts have been made to find immunological markers of protection, including toxin‐ or CF‐specific immune responses, or both. CF‐specific antibodies have been used to determine 'take rates' (the proportion of vaccinations that induce high antibody levels to vaccine) for ETEC vaccines containing CFs as components (Wenneras 1999; Qadri 2003; Rao 2005). However, adequate and lasting protection cannot be assumed without demonstrating reduced incidence of the clinical illness in large, well conducted clinical trials.

The route of administration of a vaccine may influence both its immunogenicity and acceptability. Oral vaccines have the potential to stimulate local immunity within the mucosa of the gut, preventing the colonization and multiplication of the bacteria. ETEC is transmitted through the faecal‐oral route and vaccines designed to be given orally have been developed (Holmgren 2005). Such vaccines are easy to administer in all settings and have a reduced risk of transmitting blood‐borne infections.

Why it is important to do this review

Assessment of the level of mortality and morbidity associated with ETEC diarrhoea and the extent of the global disease burden has resulted in several initiatives to develop effective vaccines (Walker 2007). ETEC vaccine development is at an earlier stage than some other vaccines (eg cholera vaccine) but data from phase II and phase III trials in endemic areas and non‐primed participants are available and these need to be reviewed.

This review aims to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of current vaccine candidates tested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including the oral cholera vaccine Dukoral®, when used to protect against ETEC diarrhoea.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of vaccines for preventing enterotoxigenic ETEC diarrhoea.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs and quasi‐RCTs, for which the unit of randomization is the individual participant or a cluster of participants.

Types of participants

Healthy adults and children living in endemic regions, intending to travel to endemic regions, or receiving an artificial challenge.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Any vaccine being used to prevent ETEC diarrhoea. Studies evaluating vaccines which have not yet been evaluated for clinical outcomes will be excluded.

Control

No intervention, a control vaccine (either an inert vaccine or a vaccine normally given to prevent an unrelated infection), an alternative ETEC vaccine, or a different dose or schedule of the same ETEC vaccine.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Protective efficacy as measured against:

Episodes of ETEC diarrhoea (any severity)

Severe episodes of ETEC diarrhoea

Secondary outcomes

Protective efficacy as measured against:

Episodes of all‐cause diarrhoea

Severe episodes of all‐cause diarrhoea

Safety measured as:

The number of adverse events, including systemic and local reactions.

Immunological outcomes:

Any immunological measure of response to vaccination, eg an increase in CF, or toxin‐specific, immune responses in serum/plasma, or both, or an increase in antibody‐secreting cell responses in lymphocytes.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

Published studies

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Disease Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS and http://clinicaltrials.gov/, using the search terms detailed in Table 3.

2. Detailed Search Strategy.

| Search set | CIDG SR¹ | CENTRAL | MEDLINE² | EMBASE² | LILACS² |

| 1 | E.coli | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli [MeSH] | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli [MeSH] | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli [Emtree] | E.coli |

| 2 | Enterotoxigenic | ETEC | ETEC ti, ab | ETEC ti, ab | Enterotoxigenic |

| 3 | ETEC | Enterotoxigenic E coli | Enterotoxigenic E coli ti, ab | Enterotoxigenic E coli ti, ab | ETEC |

| 4 | Travel* diarrh* | Travel* diarrh* | Travel* diarrh* ti, ab | Traveller diarrhea [Emtree] | Travel$ diarrh$ |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 |

| 6 | Vaccin* | Vaccin* | Vaccin* ti, ab | Vaccin* ti, ab | Vaccin$ |

| 7 | 5 and 6 | 5 and 6 | 5 and 6 | 5 and 6 | 5 and 6 |

| 8 | Escherichia coli vaccines [MeSH] | Escherichia coli vaccines [MeSH] | Escherichia coli vaccine [Emtree] | ||

| 9 | 7 or 8 | 7 or 8 | 7 or 8 | ||

| 10 | Limit 9 to humans | Limit 9 to Human |

¹Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register.

²Search terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2008).

Ongoing studies

We searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for ongoing trials using 'Enterotoxigenic' and 'vaccin*' as search terms.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We searched the reference lists of all included studies for additional references relevant to this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Tanvir Ahmed (TA) and Taufiqur Bhuiyan (TB) independently screened all citations and abstracts identified by the search strategy to identify potentially eligible studies. We obtained full‐text articles of potentially eligible studies. TA and TB independently assessed these articles for inclusion in the review using a pre‐designed eligibility form based on the inclusion criteria.

In the event that it was unclear whether a trial was eligible for the review, we resolved any differences in opinion through discussion with Firdausi Qadri (FQ). We excluded any studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and we documented the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

For each included trial, TA and TB independently extracted information on the characteristics of the trial (study design, study dates and duration, study location, setting, and source of funding), the participants recruited (the inclusion and exclusion criteria), and the intervention (the type of vaccine, type of placebo, dose, and immunization schedule), and listed the outcomes presented in the papers using a pre‐tested data extraction form. For all outcomes, we extracted the number of patients randomized to each treatment group and the number of patients for whom an outcome was available. For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the number of participants that experienced the event and the number of patients in each treatment group. We extracted adverse event data for each individual type of event wherever possible. Where adverse events were reported for more than one dose, the number of people reporting each side‐effect after each dose was recorded. Where trials reported the occurrence of adverse events over time following a single dose, we recorded the proportion of people affected during each time period. If the denominator or total number of people affected for each time period was not clear, then we only recorded the events that occurred in the first time period (typically 72 hours) after each dose. Where data were missing or incomplete, we contacted the authors for clarification. In cases of disagreement, we double‐checked the data extraction and we resolved any disagreements through discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (TA and TB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each trial using 'The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias' (Higgins 2008). We followed the guidance to assess whether steps were taken to reduce the risk of bias across six domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias.

For sequence generation and allocation concealment, we reported the methods used. For blinding, we described who was blinded and the blinding method. For incomplete outcome data, we reported the percentage and proportion lost to follow‐up in each group. For selective outcome reporting, we stated any discrepancies between the methods used and the results, in terms of the outcomes measured or the outcomes reported. For other biases, we described any other trial features that we thought could have affected the trial result (eg if the trial was stopped early).

We categorized our judgements as either low, high, or unclear risk of bias. We used this information to guide our interpretation of the data. Where our judgement was unclear risk of bias, we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification and we resolved any differences of opinion through discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios (RR), and presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

We ensured that the same patients were not included in the same meta‐analysis more than once, by grouping or splitting the data in multi‐arm trials as appropriate.

Dealing with missing data

If data from the trial reports were insufficient, unclear, or missing, we attempted to contact the trial authors for additional information. We aimed to carry out an intention‐to‐treat analysis. However if the duration of follow‐up of all patients was not known, we carried out a complete case analysis, in which we only included patients for whom an outcome was available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between the trials by examining the forest plot to check for overlapping CIs, by using the Chi2 test for heterogeneity with a 10% level of significance, and by using the I2 statistic with a value of 50% to represent moderate levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess publication bias using funnel plots because the number of trials per comparison were insufficient.

Data synthesis

We analyzed the data using Review Manager (RevMan).

We used the Mantel‐Haenszel method to combine dichotomous data. If there was no heterogeneity present, we used a fixed‐effect model. If there was moderate heterogeneity and it was still appropriate to combine studies, we used a random‐effects model. When it was deemed inappropriate to combine studies due to methodological or statistical heterogeneity, we presented the data in tables. We stratified the primary analysis by vaccine type.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses to investigate causes of heterogeneity but the data were too limited.

Sensitivity analysis

As the number of trials per comparison were insufficient, we did not conduct the pre‐planned sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the results against risk of bias judgements.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008). The GRADE system considers ‘quality’ to be a judgment of the extent to which we can be confident that the estimates of effect are correct. The level of ‘quality’ is judged on a four‐point scale. Evidence from RCTs is initially graded as high and downgraded by either one, two, or three levels after full consideration of: any limitations in the design of the studies, the directness (or applicability) of the evidence, the consistency and precision of the results, and the possibility of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

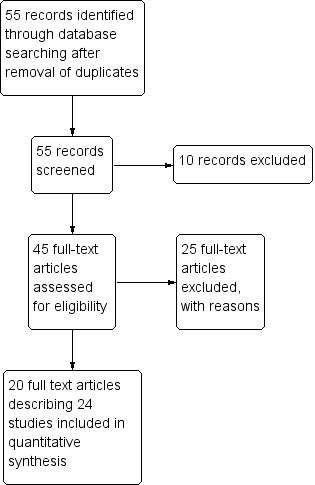

We identified 55 potentially relevant articles for inclusion. We assessed these articles using the pre‐stated inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 20 individual papers describing 24 trials which evaluated eight different vaccines. Of these, seven trials presented efficacy data from field trials (Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991; Scerpella 1995; Wiedermann 2000; Sack 2007; Leyten 2005; Frech 2008), and four trials presented efficacy data from artificial challenge studies (Freedman 1998; Tacket 1999; McKenzie 2007; McKenzie 2008). A summary of the main characteristics of these trials is given in Table 4. For further details see the Characteristics of included studies tables. An additional 13 trials only contributed safety and immunogenicity data.

3. Characteristics of trials assessing clinical efficacy.

| Vaccine details | Study ID | Population details | Challenge | |||||

| Type | Name | Route | Schedule | Age | Group | Country setting | ||

| Inactivated | Cholera WC‐BS | Oral | Three doses, at 6 week intervals | Clemens 1988 | Children aged 2 to 15 years Women aged > 15 years |

Endemic | Bangladesh | Natural |

| Oral | Two doses two weeks apart | Peltola 1991 | Adults | Travellers | From Finland to Morocco | Natural | ||

|

Cholera WC‐rCTB (Dukoral®) |

Oral | Two doses, 10 days apart | Scerpella 1995 | Adults | Travellers | From USA to Mexico | Natural | |

| ETEC WC‐rCTB | Oral | Two doses, 7 to 21 days apart | Sack 2007 | Adults | Travellers | From USA to Mexico or Guatemala | Natural | |

| Oral | Two doses, 7 to 21 days apart | Wiedermann 2000 | All ages | Travellers | From Austria to Latin America, Africa, and Asia. | Natural | ||

| Live attenuated | CVD 103‐HgR | Oral | Single dose | Leyten 2005 | Adults | Travellers | From Holland to Indonesia, Thailand, India, or West Africa | Natural |

| PTL‐003 | Oral | 2 doses, 10 days apart | McKenzie 2008 | Adults | Volunteers | USA | Artificial | |

| Other | Transcutaneous LT‐ETEC patch | Patch | 2 to 3 doses, at 2 to 3 week intervals | Frech 2008 | Adults | Travellers | From USA to Mexico and Guatemala | Natural |

| Patch | 2 to 3 doses, at 2 to 3 week intervals | McKenzie 2007 | Adults | Volunteers | USA | Artificial | ||

| Hyper immune Anti‐E coli. CFA | Oral | 3 times daily for 5 to 7 days | Freedman 1998 | Adults | Volunteers | USA | Artificial | |

| Oral | 3 times daily for 5 to 7 days | Tacket 1999 | Adults | Volunteers | USA | Artificial | ||

WC = killed whole cell, BS = cholera toxin B subunit, rCTB = recombinant cholera toxin B subunit.

Interventions

Three different killed whole cell vaccines were evaluated in efficacy trials: the oral cholera vaccine with purified B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐BS: Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991), the oral cholera vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB: Scerpella 1995), and an ETEC vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB: Wiedermann 2000; Sack 2007). Two live attenuated vaccines have undergone evaluation of clinical efficacy: one oral cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR: Leyten 2005) and one ETEC‐specific vaccine (PTL‐003: McKenzie 2008). Two additional studies evaluated an LT subunit vaccine delivered by transcutaneous patch (McKenzie 2007; Frech 2008) and two evaluated passive immunization using hyperimmune anti‐E. coli CFA (Freedman 1998; Tacket 1999).

Populations

Only one vaccine was evaluated for use among an endemic population in a low income country and this vaccine is no longer available (Cholera WC‐BS: Clemens 1988). Five vaccines were evaluated among travellers to endemic settings: Cholera WC‐BS (Peltola 1991). Cholera WC‐rCTB (Scerpella 1995), ETEC WC‐rCTB (Wiedermann 2000; Sack 2007), CVD 103‐HgR (Leyten 2005), and the LT transcutaneous patch (Frech 2008). The remaining three vaccines were evaluated among volunteers in artifical challenge studies.

Outcomes

Ten trials reported episodes of ETEC diarrhoea, six reported on severe ETEC diarrhoea, and ten reported on all‐cause diarrhoea. The definitions of these outcomes varied between trials and we have presented these in Table 5.

4. Outcome definitions for primary and secondary measures of clinical efficacy.

| Vaccine | Study ID | Trial definitions | Challenge type | Confirmation of ETEC | |

| DIarrhoea | Moderate or Severe Diarrhoea | ||||

| Cholera WC‐BS | Clemens 1988 | ≥ 3 non‐bloody loose stools in 24 hours, or fewer episodes with signs of dehydration | Severe diarrhoea = absent or feeble pulse plus one other sign of dehydration. | Natural | Faecal culture |

| Peltola 1991 | Any diarrhoea confirmed by the physician as abnormally loose | Not reported. | Natural | Faecal culture | |

|

Cholera WC‐rCTB (Dukoral®) |

Scerpella 1995 | ≥ 4 unformed stools in 24 hours, or ≥3 unformed stools in 8 hours, plus an additional symptom (nausea. pain, fever, urgency, tenesmus) | Not reported. | Natural | Faecal culture |

| ETEC WC‐rCTB | Sack 2007 | ≥ 3 loose stools in 24 hours, plus at least one other symptom, such as abdominal pain, cramps or nausea. | Severe diarrhoea = ≥ 5 loose stools in 24 hours, or illness episodes with abdominal cramps, pain, or vomiting that interfered with daily activities. | Natural | Faecal culture |

| Wiedermann 2000: | ≥ 3 liquid stools | Not reported. | Natural | Faecal culture | |

| CVD 103‐HgR | Leyten 2005 | ≥ 3 unformed stools in 24 hours, or 2 unformed stools accompanied by vomiting, abdominal cramps or subjective fever, | Moderate diarrhoea = 3 to 6 stools per day Severe diarrhoea = ≥ 6 stools per day |

Natural | Faecal culture |

| PTL‐003 | McKenzie 2008 | 1 loose stool weighing ≥ 300 g, or ≥ 2 loose stools in 48 h with a combined weight of ≥200 g, | Moderate diarrhoea = 4 to 5 loose stools, or 401 to 800 g of loose stool, in 24 hours Severe diarrhoea = ≥ 6 loose stools, or > 800 g of loose stools, in 24 hours Or mild diarrhoea plus one of these symptoms rated as moderate or severe: nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, or cramps. |

Artificial | Assumed all |

| Transcutaneous LT‐ETEC patch | Frech 2008 | ≥ 3 loose stools in 24 hours | Moderate diarrhoea = 4 to 5 loose stools Severe diarrhoea = 6 or more loose stools |

Natural | Faecal culture |

| McKenzie 2007 | 1 loose stool weighing ≥ 300 g or ≥ 2 loose stools in 48 hours weighing a total of ≥200 g, within 120 hours after challenge. | Moderate/severe diarrhoea = > 400 g of loose stool in 24 hours, or ≥ 4 loose stools in 24 hours, or ≥ 2 loose stools within a 48 hour period totaling ≥ 200 g, or a single loose stool weighing ≥ 300 g plus one of the following symptoms rated as moderate or severe: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or cramps. | Artificial | Assumed all | |

| Hyperimmune Anti‐E coli. CFA | Freedman 1998 | 1 liquid stool of ≥ 300 mL or 2 liquid stools totaling > 200 mL during any 48 hour period within 120 hours after challenge. | Not reported. | Artificial | Assumed all |

| Tacket 1999 | 1 diarrhoeal stool of > 300 mL or 2 diarrhoeal stools totaling > 200 mL passed during a 48 hour period within 96 hours after challenge. | Not reported. | Artificial | Assumed all | |

Excluded studies

We excluded 35 studies and we listed the reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

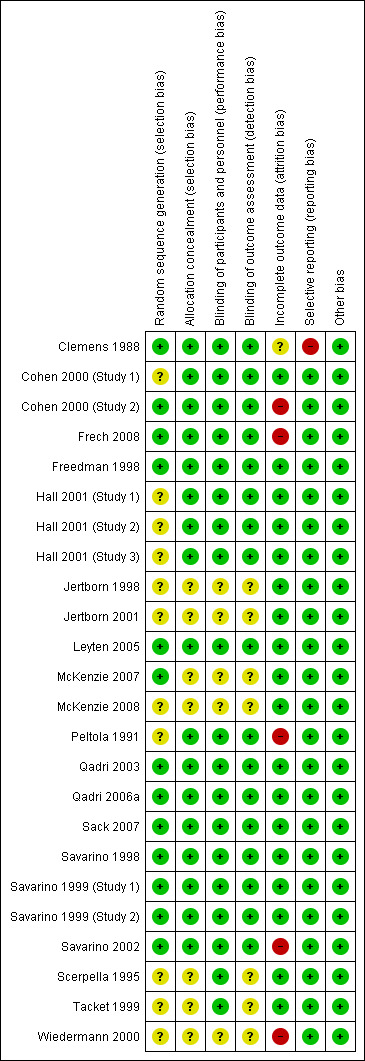

We summarized the risk of bias assessments in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Efficacy studies

We judged five natural challenge studies to have adequately described allocation concealment and we considered them to be at low risk for selection bias (Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991; Sack 2007; Leyten 2005; Frech 2008). In two natural challenge studies we judged the risk of bias to be unclear (Scerpella 1995; Wiedermann 2000). Of the five artificial challenge studies, only one adequately described a method of allocation concealment (Freedman 1998).

Safety and immunogenicity only studies

We judged 11 of the 13 safety and immunogenicity studies at low risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Efficacy studies

We found that blinding of participants and study personnel was clearly described in eight out of 11 efficacy trials (Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991; Scerpella 1995; Freedman 1998; Tacket 1999; Leyten 2005; Sack 2007; Frech 2008), and was unclear in three. Outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation in six trials (Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991; Freedman 1998; Leyten 2005; Sack 2007; Frech 2008), and was unclear in five trials (Scerpella 1995; Tacket 1999; Wiedermann 2000; McKenzie 2007; McKenzie 2008).

Safety and immunogenicity studies

Most studies (11 out of 13) used placebos which were identical in appearance to the vaccine. We considered these studies to be at low risk of bias for safety outcomes. In two studies assessors were not blinded to make a judgement and so we classified these studies at 'unclear' risk of bias (Jertborn 1998; Jertborn 2001).

Incomplete outcome data

Efficacy studies

Seven efficacy trials had low losses to follow‐up and we considered these trials at low risk of attrition bias (Scerpella 1995; Freedman 1998; Tacket 1999; Leyten 2005; McKenzie 2007; Sack 2007; McKenzie 2008). We found that three trials had high losses to follow‐up (Peltola 1991; Wiedermann 2000; Frech 2008) and we judged these trials at high risk of attrition bias. One trial was unclear about the number of participants lost to follow‐up (Clemens 1988).

Safety and immunogenicity studies

Eleven studies out of 13 reported minimal losses to follow‐up. We considered these trials at low risk of bias. Two studies had high losses to follow‐up and we judged these trials at high risk of bias (Cohen 2000 (Study 2); Savarino 2002).

Selective reporting

We found no evidence of selective reporting bias in any of the included studies.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no evidence of other potential sources of bias in the trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Cholera killed whole cell vaccines versus placebo

Two oral vaccines containing killed whole cells of V. cholerae have been evaluated. The first contained 1 mg of purified cholera B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐BS). This vaccine was further developed with a recombinant cholera B‐subunit and is commercially available (Cholera WC‐rBS).

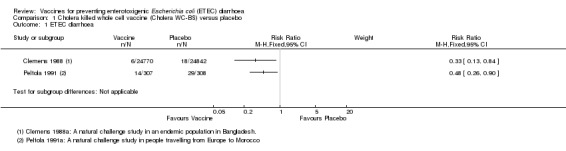

Analysis 1: Cholera killed whole cells plus purified B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐BS)

Clinical efficacy

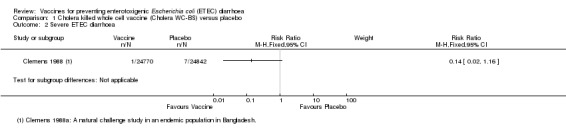

In Bangladesh, in a passive surveillance study in a community endemic with ETEC diarrhoea, Clemens 1988 found that the oral Cholera WC‐BS vaccine provided short‐term protection against LT‐ETEC diarrhoea at three months' follow‐up compared to the same whole cell vaccine without the B‐subunit (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.84; one trial, 49,612 participants, Analysis 1.1). However, only 24 episodes of ETEC diarrhoea were reported in this study (18 in the placebo group versus six in the vaccine group). Eight episodes of severe ETEC diarrhoea were reported (seven in the placebo group versus one in the vaccine group) and this result was not statistically significant (one trial, 49,612 participants, Analysis 1.2). No protective efficacy was demonstrated at later time points.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Cholera WC‐BS) versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Cholera WC‐BS) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Severe ETEC diarrhoea.

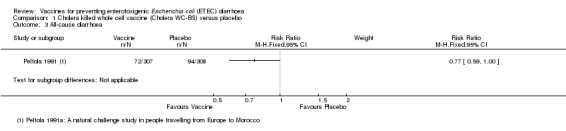

One additional trial evaluated the same vaccine given to people intending to travel from Europe to Morocco (Peltola 1991). The authors found a statistically significant reduction in ETEC diarrhoea (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.90; one trial, 615 participants, Analysis 1.1) and all‐cause diarrhoea (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.00; one trial, 615 participants, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Cholera WC‐BS) versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause diarrhoea.

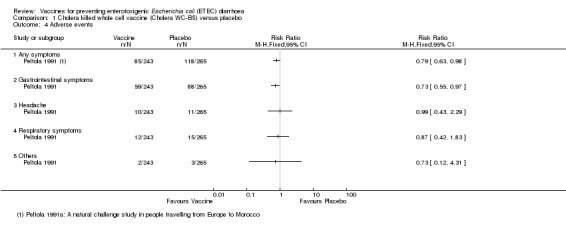

Safety

Safety data were only available from 508 participants in Peltola 1991. 'Gastrointestinal symptoms' were higher in those receiving the placebo than the vaccine during the first three days after vaccination (P = 0.03, Analysis 1.4). No other significant reactogenicity was observed.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Cholera WC‐BS) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

Immunological response

The studies did not report on the outcome of immunological response.

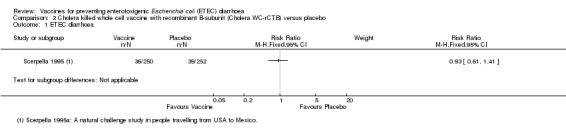

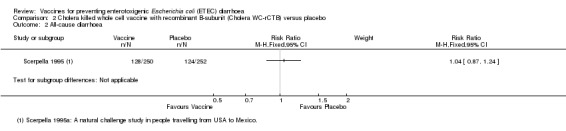

Analysis 2: Cholera killed whole cells plus recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB; Dukoral®)

Clinical efficacy

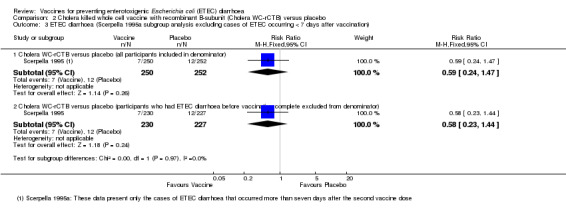

The currently available oral Cholera WC‐rCTB vaccine was evaluated in a single RCT in people arriving in Mexico from the USA (Scerpella 1995). There were no statistically significant differences in episodes of either ETEC‐specific diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea between those receiving vaccine and placebo (one trial, 502 participants, Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2). However, in this trial the vaccine was only administered after arrival in Mexico and most episodes of diarrhoea occurred before completion of the two dose regimen or within 7 days of the second dose.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 2 All‐cause diarrhoea.

The authors of this paper considered that adequate protection would not be attained until seven days after the second dose. They reported a 50% protective effect in a subgroup analysis of cases occurring after this timepoint (95% CI 14 to 71%, authors' own figures). However, it should be noted that this subgroup analysis excluded 75% of the observed cases of ETEC diarrhoea. Only 19 episodes of ETEC diarrhoea were included (12 with placebo and seven with vaccine), and our re‐analysis of this data suggested that this difference was not statistically significant (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 3 ETEC diarrhoea (Scerpella 1995a subgroup analysis excluding cases of ETEC occurring < 7 days after vaccination).

Safety

Scerpella 1995 reported that there were no differences in the frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, or febrile illnesses between people that received either the vaccine or placebo, but data were not presented.

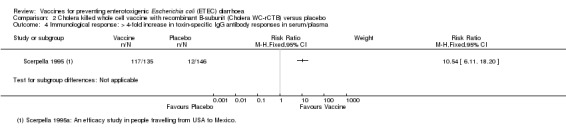

Immunological response

Toxin‐specific IgG antibody (TSA) responses were available from 281 participants. A greater than four‐fold increase was observed in 87% of the participants who received Cholera WC‐rCTB vaccine compared to 8% in controls (RR 10.54, 95% CI 6.11 to 18.20; one trial, 281 participants, Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cholera killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Immunological response: > 4‐fold increase in toxin‐specific IgG antibody responses in serum/plasma.

ETEC killed whole cell vaccines versus placebo

Analysis 3: ETEC killed whole cells plus recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB)

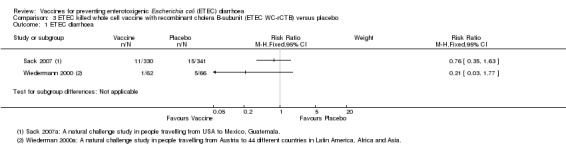

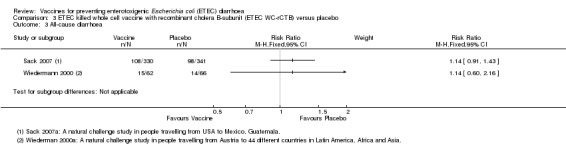

Clinical efficacy

Two studies have evaluated this oral ETEC vaccine (ETEC WC‐rCTB); in people travelling from the USA to Mexico or Guatemala (Sack 2007), and from Austria to one of 44 different countries in Latin America, Africa, or Asia (Wiedermann 2000). There were no statistically significant differences in ETEC‐specific diarrhoea, or all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 799 participants, Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause diarrhoea.

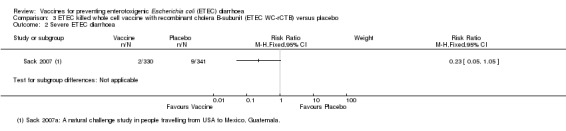

In Sack 2007 a small number of severe ETEC episodes are recorded (two in the vaccine group and nine in the placebo group), and this difference approached statistical significance (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.05; one trial, 671 participants, Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Severe ETEC diarrhoea.

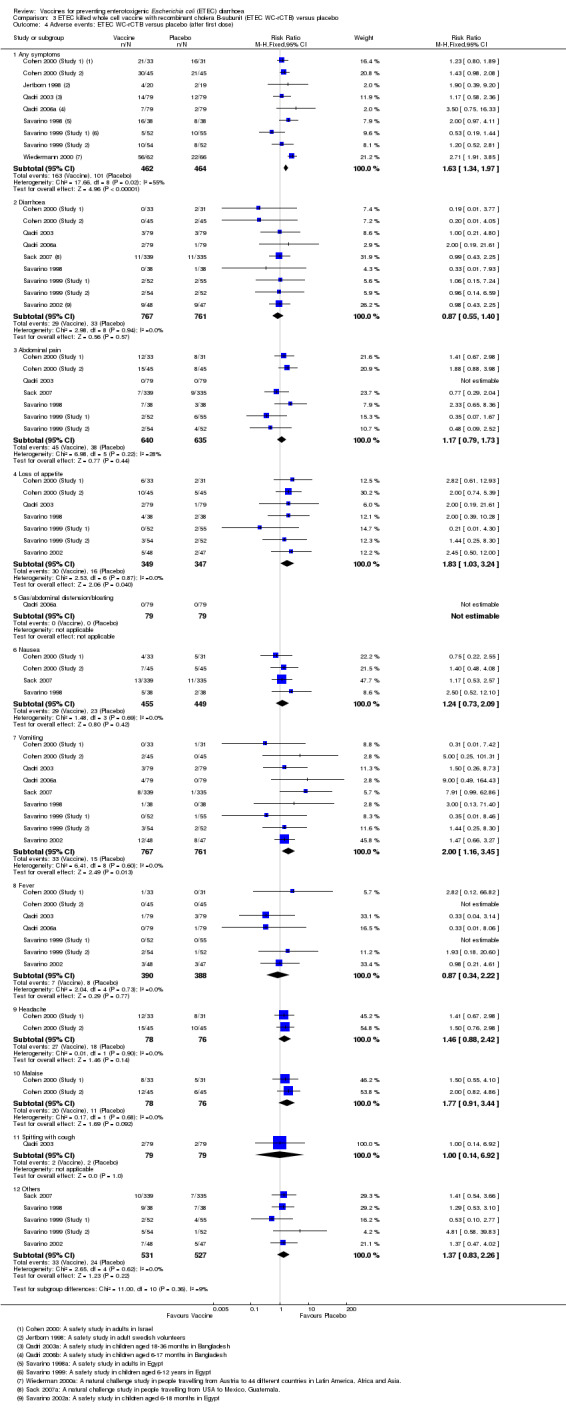

Safety

A total of 1695 participants have received ETEC WC‐rCTB or placebo in 11 RCTs. Vomiting was the only symptom significantly more common in those receiving the vaccine compared to placebo (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.45; nine trials, 1528 participants, Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Adverse events: ETEC WC‐rCTB versus placebo (after first dose).

Immunological response

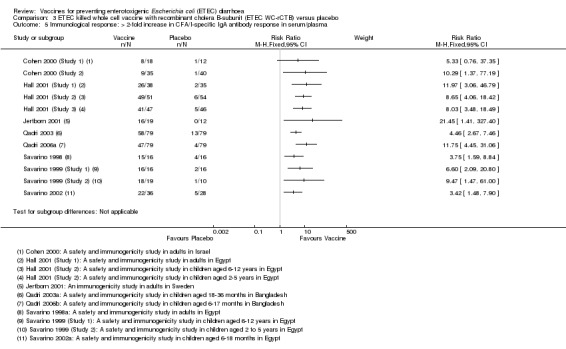

CFA/I‐specific antibody response:

Anti‐CFA/I antibody responses were evaluated in 880 participants in 12 RCTs. CFA/I‐specific IgA antibody responses were evaluated in serum, plasma, or antibody secreting cells (ASCs). They were found to be statistically higher in the vaccine group compared to controls (RR 6.78, 95% CI 5.12 to 8.98, P < 0.00001; 12 trials, 880 participants, Analysis 3.5). In individual studies, the proportion of participants with a greater than two‐fold increase following vaccination ranged from: 26% to 94% in adults; 96% to 100% in children aged between 6 to 12 years; 73% to 95% in children aged between 18 months to 5 years; and 59% to 61% in infants aged between 6 to 18 months (Table 6).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in CFA/I‐specific IgA antibody response in serum/plasma.

5. Additional immunological data for responses to CFs in the IgA isotype to ETEC WC‐rCTB vaccine.

| Study ID | Age group | Trial setting | Number of participants with a > 2‐fold increase in immunological response after the second dose of oral ETEC‐rCTB (%) | ||||||||||

| CFA/I | CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | CS4 | Remarks | ||||||||

| V | P | V | P | V | P | V | P | V | P | ||||

| Savarino 1998 | Adults | Egypt | 15/16 (94%) |

4/16 (25%) |

11/16 (69%) |

1/16 (6%) |

13/16 (81%) |

2/16 (13%) |

ND | ND | 16/16 (100%) |

6/16 (38%) |

Serum |

| Cohen 2000 (Study 2) | Adults | Israel | 9/35 (26%) |

1/40 (3%) |

11/35 (31%) |

2/40 (5%) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Serum |

| Jertborn 2001 | Adults | Sweden | 16/19 (84%) |

0/12 (0%) |

4/19 (21%) |

1/12 (8%) |

10/19 (53%) |

0/12 (0%) |

ND | ND | 12/19 (63%) |

0/12 (0%) |

Serum |

| Hall 2001 (Study 1) | Adults | Egypt | 26/38 (68%) |

2/35 (6%) |

21/38 (56%) |

0/35 (0%) |

12/38 (31%) |

2/35 (6%) |

ND | ND | 26/38 (69%) |

4/35 (12%) |

Serum |

| Savarino 1999 (Study 1) | Children 6‐12 Y |

Egypt | 16/16 (100%) |

2/16 (13%) |

3/8 (38%) |

1/9 (11%) |

12/13 (92%) |

2/12 (17%) |

ND | ND | 14/15 (93%) |

4/16 (25%) |

ASC |

| Hall 2001 (Study 2) | Children 6‐12 Y |

Egypt | 49/51 (96%) |

6/54 (11%) |

47/51 (92%) |

4/54 (7%) |

40/51 (78%) |

5/54 (9%) |

ND | ND | 43/51 (84%) |

3/54 (6%) |

Serum |

| Savarino 1999 (Study 2) | Children 2‐5 Y |

Egypt | 18/19 (95%) |

1/10 (10%) |

ND | ND | 15/18 (83%) |

1/10 (10%) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ASC |

| Hall 2001 (Study 3) | Children 2‐5 Y |

Egypt | 41/47 (87%) |

5/46 (11%) |

43/47 (91%) |

1/46 (2%) |

37/47 (79%) |

6/46 (12%) |

ND | ND | 33/47 (70%) |

3/46 (7%) |

Serum |

| Qadri 2003 | Children 18‐36 M |

Bangladesh | 58/79 (73%) |

13/79 (16%) |

61/79 (77%) |

10/79 (13%) |

69/79 (87%) |

8/79 (10%) |

ND | ND | 55/79 (70%) |

2/79 (3%) |

Plasma |

| Savarino 2002 | Children 6‐18 M |

Egypt | 22/36 (61%) |

5/28 (18%) |

7/36 (20%) |

1/28 (4%) |

9/36 (26%) |

1/28 (4%) |

ND | ND | 14/36 (39%) |

2/28 (7%) |

Serum |

| Qadri 2006a | Children 6‐17 M |

Bangladesh | 47/79 (59%) |

4/79 (5%) |

53/79 (67%) |

26/79 (33%) |

37/79 (47%) |

16/79 (20%) |

40/79 (50%) |

12/79 (15%) |

ND | ND | Plasma |

V = vaccine, P = placebo, CS = colonization surface antigen, ND = not done , ASC = antibody secreting cell, CFA = colonization factor antibody

CF‐specific IgA antibody responses were also reported to anti‐CS1 (10 trials), anti‐CS2 (10 trials), anti‐CS3 (one study), and anti‐CS4 (eight trials). These data are summarized in Table 6.

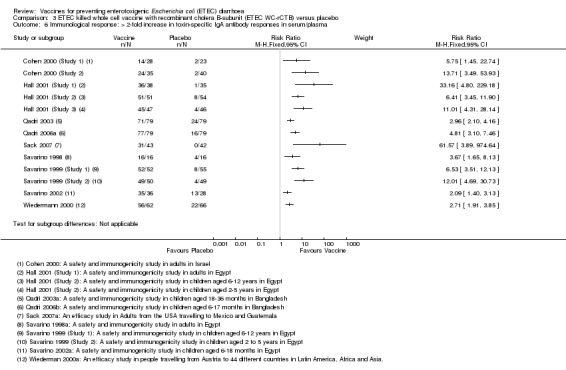

Toxin‐specific antibody response:

Either CT or LT toxin‐specific IgA antibody responses were evaluated in a total of 1228 participants in 13 RCTs. In individual studies, the percentage of participants with > two‐fold increases in toxin‐specific antibodies ranged from 50% to 100% in those receiving the vaccine compared to 0% to 33% in controls (RR 5.03, 95% CI 4.25 to 5.96, P < 0.00001; 13 trials, 1228 participants, Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in toxin‐specific IgA antibody responses in serum/plasma.

Live attenuated vaccines versus placebo

Two live attenuated vaccines have been evaluated in placebo controlled trials: the oral cholera vaccine CVD 103‐HgR in a natural challenge study in travellers (Leyten 2005) and the oral ETEC vaccine PTL‐003 in a small artificial challenge study (McKenzie 2008).

Analysis 4: Live attenuated cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR)

Clinical efficacy

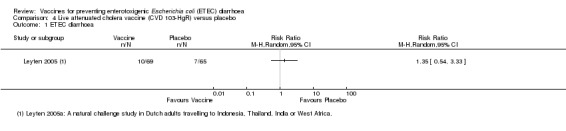

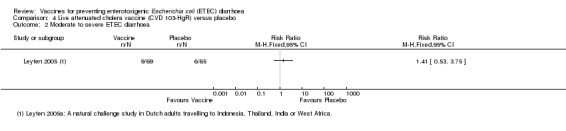

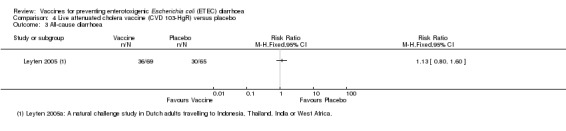

Leyten 2005 evaluated CVD 103‐HgR, a live oral cholera vaccine, in Dutch volunteers intending to travel to Indonesia, Thailand, the Indian subcontinent, or West Africa. This study reported no significant differences in ETEC diarrhoea, severe ETEC diarrhoea, or all‐cause diarrhoea (one trial, 134 participants, Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Live attenuated cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR) versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Live attenuated cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Live attenuated cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR) versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause diarrhoea.

Safety

This outcome was not reported.

Immunological response

This outcome was not reported.

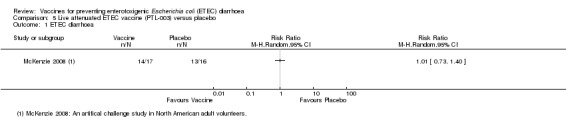

Analysis 5: Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003)

Clinical efficacy

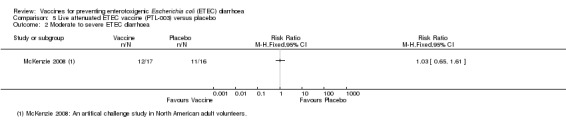

McKenzie 2008 evaluated PTL‐003, a live attenuated ETEC‐specific vaccine, in a small artificial challenge study in North American volunteers. The authors reported no statistically significant reduction in ETEC diarrhoea (one trial, 33 participants, Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003) versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea.

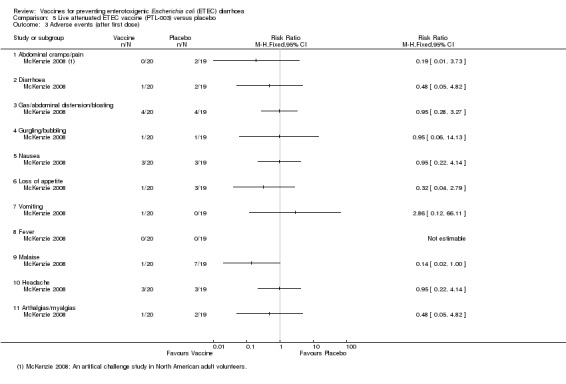

Safety

McKenzie 2008 reported safety data. No statistically significant differences in adverse events were observed between vaccine and control groups (one trial, 33 participants, Analysis 5.3).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Adverse events (after first dose).

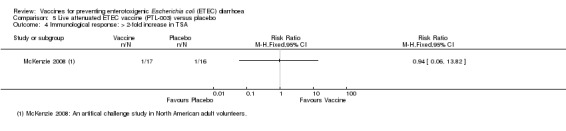

Immunological response

McKenzie 2008 reported the proportion of participants with a > two‐fold increase in CF‐specific antibody responses against CS1 and CS3 and found significantly higher IgA titres in vaccinees compared to controls (see Table 7). There were no significant differences in toxin‐specific antibody responses (Analysis 5.4).

6. Additional immunological data for IgA response to CFs to live oral attenuated vaccine.

| Study ID | Number of participants with > 2‐fold increase in immunological response (%) | ||||||||

| CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | CS4 | Remarks | |||||

| V | P | V | P | V | P | V | P | ||

| McKenzie 2008 | 7/17 (41%) |

1/16 (6%) |

ND | ND | 7/17 (41%) |

0/16 (0%) |

ND | ND | Serum |

V = vaccine, P = placebo, CS = colonization surface antigen, ND = not done

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in TSA.

Transcutaneous vaccines versus placebo

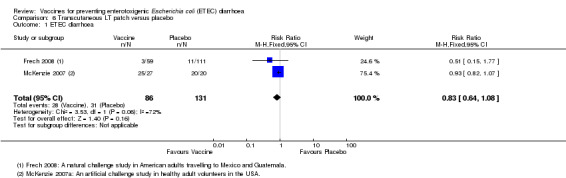

Analysis 6: Transcutaneous LT patch

Clinical efficacy

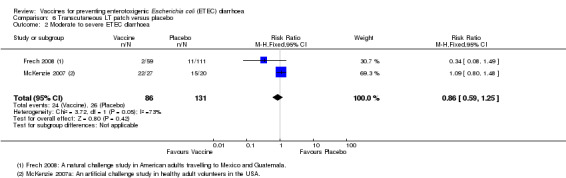

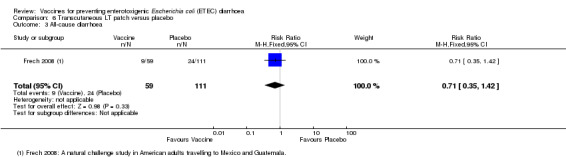

An LT‐ETEC vaccine delivered via a transcutaneous patch was evaluated in one natural challenge study in American adults intending to travel to Mexico and Guatemala (Frech 2008) and in one artificial challenge study in North American volunteers (McKenzie 2007). No statistically significant differences were reported for ETEC diarrhoea, severe ETEC diarrhoea, or all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 217 participants, Analysis 6.1; Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo, Outcome 1 ETEC diarrhoea.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo, Outcome 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause diarrhoea.

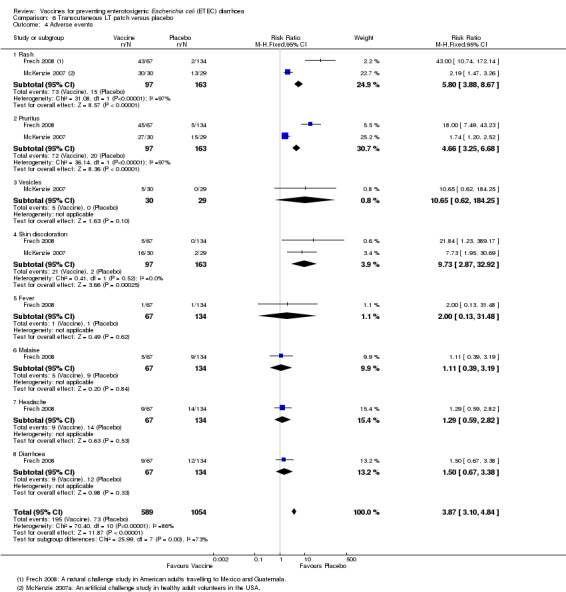

Safety

A total of 260 participants from two studies were evaluated for safety data, particularly regarding reactogenicity at the application site and other systemic adverse events (McKenzie 2007; Frech 2008). A significantly higher number of local immune reactions in the form of rash (P < 0.00001), pruritus (P < 0.00001), and skin discolouration (P = 0.0003) were observed in people that received the vaccine compared to placebo recipients (Analysis 6.4). For other events, there were no significant differences (Analysis 6.4).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

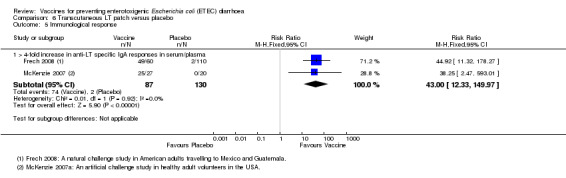

Immunological Response

Frech 2008 and McKenzie 2007 reported a > four‐fold increase in toxin‐specific IgA antibody responses in 82% and 93% of people vaccinated, respectively (RR 43.0, 95% CI 12.33 to 149.97, P < 0.00001; two trials, 217 participants, Analysis 6.5).

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo, Outcome 5 Immunological response.

Passive immunization versus placebo

Analysis 7: Hyperimmune anti‐ETEC CFA

Clinical efficacy

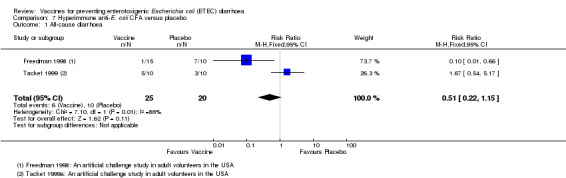

Two artificial challenge studies reported passive immunization using bovine hyperimmune anti‐ETEC CFA in North American volunteers (Freedman 1998; Tacket 1999). The authors did not find any significant protective efficacy against all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 45 participants, Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Hyperimmune anti‐E. coli CFA versus placebo, Outcome 1 All‐cause diarrhoea.

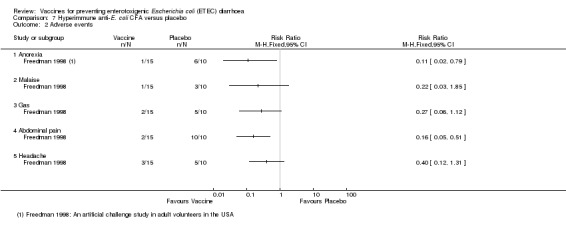

Safety

A total of 45 participants from the studies by Freedman 1998 and Tacket 1999 were evaluated for safety data. A significantly higher number of events occurred in people that were vaccinated compared to those that received a placebo regarding the events of anorexia (P = 0.01) and abdominal pain (P = 0.003) (Analysis 7.2). For other events, there were no significant differences between people that were vaccinated and those that received a placebo (Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Hyperimmune anti‐E. coli CFA versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

Immunological Response

No immunological data were reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, we included 24 trials and 53,247 participants. Four studies assessed the protective efficacy of oral cholera vaccines when used to also prevent diarrhoea due to ETEC and eight trials assessed the protective efficacy of ETEC‐specific vaccines.

Cholera vaccines

A single RCT evaluated the currently available oral cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Dukoral®) for protection against 'travellers' diarrhoea' in people arriving in Mexico from the USA. There were no statistically significant effects on ETEC diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea (one trial (Scerpella 1995), 502 participants, low quality evidence).

Two earlier trials, one in an endemic population in Bangladesh (Clemens 1988) and one in travellers from Finland to Morocco (Peltola 1991), evaluated a precursor of this vaccine containing purified cholera toxin B subunit, rather than the recombinant subunit in Dukoral®. Short term protective efficacy against ETEC diarrhoea was demonstrated lasting for around three months (two trials, 50,227 participants). This vaccine is no longer available.

ETEC vaccines

An ETEC‐specific killed whole cell vaccine, also containing the recombinant cholera toxin B‐subunit, was evaluated in people travelling from the USA to Mexico or Guatemala (Sack 2007), and from Austria to Latin America, Africa, or Asia (Wiedermann 2000). There were no statistically significant differences in ETEC‐specific diarrhoea or all‐cause diarrhoea (two trials, 799 participants) and the vaccine was associated with increased vomiting (nine trials, 1528 participants) (Cohen 2000 (Study 1); Cohen 2000 (Study 2); Qadri 2003; Qadri 2006a; Sack 2007; Savarino 1998; Savarino 1999 (Study 1); Savarino 1999 (Study 2); Savarino 2002). The other ETEC‐specific vaccines in development have not yet demonstrated clinically important benefits.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The use of the oral cholera WC‐rCTB vaccine for preventing 'travellers' diarrhoea' has been based on the findings of two trials that demonstrated some short term protection against ETEC diarrhoea (Clemens 1988; Peltola 1991). The vaccine used in both of these trials contained 1 mg of purified cholera B‐subunit, rather than the recombinant B‐subunit in the current vaccine. It should be noted that the cholera B‐subunit is the only element of this vaccine which could be expected to induce immunity to ETEC. These two vaccines were directly compared in a single trial of 41 Swedish volunteers (Jertborn 1992), which reported comparable cholera‐specific antibody responses but did not evaluate either clinical or immunological protection against ETEC. The finding of limited protective benefit with the cholera WC‐rCTB vaccine (Scerpella 1995) is supported by two further trials evaluating the ETEC WC‐rCTB vaccine which contains the same recombinant cholera B‐subunit, and also found no evidence of clinical protection in travellers (Wiedermann 2000; Sack 2007). These three trials raise concerns that the earlier findings may not be applied to the current vaccine.

In addition, the large study from Bangladesh (Clemens 1988), which contributed over 90% of participants included in this review, aimed primarily to assess the protective efficacy against cholera not ETEC. The assessment of protective efficacy against ETEC therefore represented a post‐hoc analysis. This trial was conducted among an endemic population who were likely to have acquired some natural immunity against ETEC. The results of this study may therefore be poorly applicable to travellers.

The ETEC‐specific vaccines are now primarily being designed for use in developing country settings for prevention of ETEC diarrhoea in infants and young children, although protection of travellers remains important (Holmgren 2012). Promising CFs and toxin‐specific immune responses to the ETEC WC‐rCTB vaccine have been observed. However, following failure to demonstrate clinical protective efficacy and safety concerns, further pre‐clinical development of this vaccine is underway (Tobias 2012). Several additional vaccine candidates not included in this review are currently at early stages of development. In Sweden, an oral inactivated tetravalent ETEC vaccine alone or together with double mutant heat labile toxin (dmLT) adjuvant is undergoing testing in Phase I/II studies. In the USA an oral live attenuated three strain recombinant ETEC vaccine, ACE527, is undergoing testing with plans for moving field sites in developing countries (Darsley 2012).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for the oral cholera vaccine (Dukoral®) was assessed using the GRADE approach. Clinically important benefits of this vaccine have not yet been demonstrated and the quality of this evidence was downgraded to 'low'. This means that use of this vaccine may have little or no difference in preventing ETEC diarrhoea but further research may change this result. The quality was downgraded due to concerns about the applicability of the evidence. Most cases of ETEC diarrhoea occurred prior to completion of the vaccine schedule (indirectness) and the sample size was small (imprecision) (Table 1).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A previous review of vaccination to prevent ETEC diarrhoea concluded that the protective effect of Dukoral® was up to 43% and that it should be recommended for travellers (Jelinek 2008). However, this conclusion was based predominantly on positive findings from the older trials assessing prototypes of the Dukoral® vaccine, on subgroup analyses which may or may not have been pre‐planned, or on the findings of non‐randomized retrospective studies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is currently insufficient evidence from RCTs to support the use of the oral cholera vaccine (Dukoral®) for protecting travellers against ETEC diarrhoea.

Implications for research.

Further research is needed to develop safe, immunogenic, and effective vaccines to provide both short and long term protection against ETEC diarrhoea.

More studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of new and candidate vaccines for safety and immunogenicity in naive adult travellers, and exposed and primed populations in a developing country setting where children and infants will be the major targets for future vaccination. ETEC vaccine development needs to include plans for overcoming barriers to oral vaccination in children. Also, strategies are needed to deliver the vaccines using the existing national immunization system of these countries, including the EPI, the cold chain facilities, and other national health facilities. In addition, the use of different modes of delivery of vaccines (including use of mucosal adjuvants) needs to be studied to improve immunogenicity and efficacy of ETEC vaccines.

Acknowledgements

The academic editor for this review was Dr Patricia Graves.

The editorial base for the Cochrane Infectious Disease Group is funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), UK, for the benefit of developing countries. This work was also supported by the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) and by funding from the Effective Health Research Consortium, and a grant from the Department for International Development, UK.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Cholera killed whole cell vaccine (Cholera WC‐BS) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Severe ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 All‐cause diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Any symptoms | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Gastrointestinal symptoms | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Headache | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Respiratory symptoms | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.5 Others | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Cholera killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant B‐subunit (Cholera WC‐rCTB) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 All‐cause diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 ETEC diarrhoea (Scerpella 1995a subgroup analysis excluding cases of ETEC occurring < 7 days after vaccination) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Cholera WC‐rCTB versus placebo (all participants included in denominator) | 1 | 502 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.24, 1.47] |

| 3.2 Cholera WC‐rCTB versus placebo (participants who had ETEC diarrhoea before vaccination complete excluded from denominator) | 1 | 457 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.23, 1.44] |

| 4 Immunological response: > 4‐fold increase in toxin‐specific IgG antibody responses in serum/plasma | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 3. ETEC killed whole cell vaccine with recombinant cholera B‐subunit (ETEC WC‐rCTB) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Severe ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 All‐cause diarrhoea | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Adverse events: ETEC WC‐rCTB versus placebo (after first dose) | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Any symptoms | 9 | 926 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.34, 1.97] |

| 4.2 Diarrhoea | 9 | 1528 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.55, 1.40] |

| 4.3 Abdominal pain | 7 | 1275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.79, 1.73] |

| 4.4 Loss of appetite | 7 | 696 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.83 [1.03, 3.24] |

| 4.5 Gas/abdominal distension/bloating | 1 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.6 Nausea | 4 | 904 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.73, 2.09] |

| 4.7 Vomiting | 9 | 1528 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [1.16, 3.45] |

| 4.8 Fever | 7 | 778 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.34, 2.22] |

| 4.9 Headache | 2 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.88, 2.42] |

| 4.10 Malaise | 2 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [0.91, 3.44] |

| 4.11 Spitting with cough | 1 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.14, 6.92] |

| 4.12 Others | 5 | 1058 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.83, 2.26] |

| 5 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in CFA/I‐specific IgA antibody response in serum/plasma | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in toxin‐specific IgA antibody responses in serum/plasma | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 4. Live attenuated cholera vaccine (CVD 103‐HgR) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 All‐cause diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 5. Live attenuated ETEC vaccine (PTL‐003) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Adverse events (after first dose) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Abdominal cramps/pain | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Gas/abdominal distension/bloating | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Gurgling/bubbling | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Nausea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Loss of appetite | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.7 Vomiting | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.8 Fever | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.9 Malaise | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.10 Headache | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.11 Arthalgias/myalgias | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Immunological response: > 2‐fold increase in TSA | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 6. Transcutaneous LT patch versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ETEC diarrhoea | 2 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.64, 1.08] |

| 2 Moderate to severe ETEC diarrhoea | 2 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.59, 1.25] |

| 3 All‐cause diarrhoea | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.35, 1.42] |

| 4 Adverse events | 2 | 1643 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.87 [3.10, 4.84] |

| 4.1 Rash | 2 | 260 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.80 [3.88, 8.67] |

| 4.2 Pruritus | 2 | 260 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.66 [3.25, 6.68] |

| 4.3 Vesicles | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.65 [0.62, 184.25] |

| 4.4 Skin discoloration | 2 | 260 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.73 [2.87, 32.92] |

| 4.5 Fever | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.13, 31.48] |

| 4.6 Malaise | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.39, 3.19] |

| 4.7 Headache | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.59, 2.82] |

| 4.8 Diarrhoea | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.67, 3.38] |

| 5 Immunological response | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 > 4‐fold increase in anti‐LT specific IgA responses in serum/plasma | 2 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 43.00 [12.33, 149.97] |

Comparison 7. Hyperimmune anti‐E. coli CFA versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause diarrhoea | 2 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.22, 1.15] |

| 2 Adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Anorexia | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Malaise | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Gas | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Abdominal pain | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Headache | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Clemens 1988.

| Methods | Study type: Randomized, natural challenge, efficacy study in an endemic population Trial dates and duration: From January 1985 to May 1986 Surveillance: Surveillance for diarrhoea was done at treatment centres serving the study participants at Matlab for 365 post‐vaccination days |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 49,612 Inclusion criteria: People aged between 2 to 15 years of age and female subjects > 15 years of age residing in Matlab Exclusion criteria: Persons who were absent or refused to participate, pregnant, or suffering from any other illness |

|

| Interventions | Vaccine: Cholera toxin B subunit plus killed cholera whole cells (BS‐WC) Control: Killed cholera whole cells (WC) Additional details: In this study participants received 3 doses of vaccine at 6 weeks apart, of BS‐WC vaccine, WC vaccine only, or an E. coli K12 strain placebo. However, protective efficacy was calculated based on WC vaccine as control and BS‐WC as study intervention group, because the killed cholera whole cells, which were identical for the BS‐WC and WC vaccines, were not anticipated to have any protective effects against LT‐ETEC |

|

| Outcomes |

Included in review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: Matlab, Bangladesh Setting: Three different treatment centres at Matlab, a rural setting of Bangladesh Source of funding: US agency for International Development, the Government of Japan, the Swedish agency for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries and the World Health Organization (WHO) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "After computerisation of the census, we assigned every person in the eligible age‐gender categories to letters A, B or C, using simple randomisation" (from additional paper describing this study). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The agents were identified only by the letters A, B and C" (from an additional paper describing this study). Allocation concealed. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "During the conduct of the study, the identities of these letter...were unknown to all persons connected with the trial in Bangladesh". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "During the conduct of the study, the identities of these letter...were unknown to all persons connected with the trial in Bangladesh". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Losses to follow‐up were not clearly described. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | This was a three arm study. It was unclear why the group given the cholera WC vaccine was selected as the control arm rather than the group given a placebo. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Cohen 2000 (Study 1).

| Methods | Study type: Randomized safety and immunogenicity study in volunteers Trial dates and duration: Between May 22 and July 10 1995 |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 65 Inclusion criteria: Healthy men and women and were recruited among the School of Military Medicine cadets or the Medical Corps Headquarters staff. Exclusion criteria: Not described. |

|

| Interventions | Vaccine: Contained 1.0 mg of rCTB plus a final count of ∼1011 formalin‐inactivated bacteria. Each vaccine dose included the following inactivated ETEC strains: SBL 101 (O78, CFA/I, LT2/ST1), SBL 106 (O6, CS1, LT2/ST2), SBL 107 (OR, CS2, CS3, LT2/ST2), SBL 104 (O25, CS41CS6, LT2/ST2) and SBL 105 (O167, CS51CS6, LT2/ST2). Placebo: Heat‐killed E. coli K12 with an optical density (OD) equivalent to that of the ETEC vaccine, was administered in the same buffered solution as the vaccine. Additional details: Each dose of lot E003 was given in 150 mL of water with a raspberry‐flavoured bicarbonate‐citric acid buffer containing 4 g of sodium bicarbonate per dose (Recip AB, Stockholm, Sweden). |

|

| Outcomes |

Included in review:

Not included in the review:

|

|

| Notes | Location: Israel Setting: Israel Defence Force (IDF), Medical Corps, Army Health Branch Research Unit, and the IDF, Medical Corps, School of Military Medicine Source of funding: US Army Medical Research & Material Command (DAMD 17‐93‐V‐3001) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Group randomization was used so that each group was assigned two letters, and each volunteer was openly allotted to one of the four resulting letter groups". It is unclear if this method was truly random. |