Abstract

Objective:

The current review provides an evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (SITBs) in youth.

Method:

A systematic search was conducted of two major scientific databases (PsycInfo and PubMed) and ClinicalTrials.gov for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published prior to June 2018.

Results:

The search identified 26 RCTs examining interventions for SITBs in youth: 17 were included in the 2015 review and 9 trials were new to this update. The biggest change since the prior review was the evaluation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A) as the first Level 1: Well-established intervention for reducing deliberate self-harm (composite of nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury) and suicide ideation in youth and Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts. Five other interventions were rated as Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing SITBs in youth, with the new addition of Integrated Family Therapy.

Conclusions:

This evidence base update indicates that there are a few promising treatments for reducing SITBs in youth. Efficacious interventions typically include a significant family or parent training component as well as skills training (e.g., emotion regulation skills). Aside from DBT-A, few treatments have been examined in more than one RCT. Given that replication by independent research groups is needed to evaluate an intervention as Well-established, future research should focus on replicating the five promising interventions currently evaluated as Probably efficacious. In addition, an important future direction is to develop brief efficacious interventions that may be scalable to reach large numbers of youth.

Keywords: nonsuicidal self-injury, randomized controlled trial, suicide, treatment, treatment effectiveness

Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (SITBs) refers to a range of thoughts and actions related to deliberate, self-directed, and non-fatal harm (Nock, 2010). This broad class can be divided into two subcategories—nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal self-injury—both of which are highly prevalent and impairing among youth. Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to cognitions and behaviors related to self-inflicted harm without any intent to die, such as nonsuicidal cutting, burning, and scratching (Nock, 2010; Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O’Carroll, & Joiner, 2007). Cross-national estimates indicate that approximately 17–18% of youth will engage in NSSI in their lifetime (Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape, & Plener, 2012; Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St John, 2014). Suicidal self-injury refers to cognitions (suicide ideation) and behaviors (suicide attempts) related to self-inflicted harm with at least some intent to die (Nock, 2010; Silverman et al., 2007). In 2017 in the U.S., approximately 17.2% of youth seriously considered suicide and 7.4% made at least one suicide attempt (CDC, 2017b).

SITBs are relatively rare in childhood but increase significantly during the transition to and throughout adolescence (Glenn et al., 2017; Nock et al., 2008; Nock et al., 2013). Among youth 10–19 years old, SITBs are associated with significant academic and social impairment (Copeland, Goldston, & Costello, 2017; Foley, Goldston, Costello, & Angold, 2006), substantial burden to the healthcare system (CDC, 2017a), and significantly increased risk for suicide death—the 2nd leading cause of death among this age group (CDC, 2017a). Taken together, adolescence is a developmental period where SITBs typically begin, increase in prevalence, and significantly impair functioning. As such, this period represents a critical opportunity for effective intervention and prevention of SITBs (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (NAASP): Research Prioritization Task Force, 2014; Wyman, 2014).

Interventions specifically designed for reducing SITBs in children and adolescents have increased significantly over the past 15 years. The 2015 review on this topic (Glenn, Franklin, & Nock, 2015) was the first JCCAP Evidence-Base Update of psychosocial treatments for SITBs in youth. This prior review included 18 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), five non-randomized controlled trials, and six pilot studies of various psychological interventions for reducing SITBs in youth. No treatments were identified as Well-established, or leading, interventions for SITBs in children and adolescents. However, a number of interventions were identified as Probably efficacious, but most had only been tested in one RCT.

The purpose of the current Evidence Base Update is to provide an updated review of psychosocial treatments for SITBs in youth (i.e., covering the past five years since the prior review ended in September 2013). Given the increasing number of RCTs, and because such research designs provide the best test of treatment efficacy, we chose to focus this review exclusively on RCTs. When evaluating the overall research literature, we briefly review the RCTs that were included in the 2015 review (and refer the reader to that review for additional details). The focus of this review is on the new trials identified since the prior review and changes in treatment efficacy based on this new research.

Update Review Parameters

To identify all relevant trials that examined a psychosocial intervention aimed at reducing SITBs in children or adolescents, we performed a comprehensive search of two major scientific databases (PsycInfo and PubMed) for journal articles in English published or in press prior to June 1, 2018. Searches included combinations of terms for SITBs (NSSI, nonsuicidal self-injury, cutting, parasuicide, self-harm, self-injury, self-injurious, self-mutilation, self-poisoning, suicide, suicide ideation, suicidal thoughts, suicide gesture, suicide attempt, suicidal behavior, suicide event, suicide plan, suicidality), interventions (clinical trial, counseling, counselling, intervention, program, randomized, psychotherapy, therapy, therapeutic, treatment), and children and adolescents (adolescence, adolescent, child, childhood, children, teen, teenagers, student, young people, youth). In addition to these online databases, we also searched ClinicalTrials.gov for any relevant ongoing or recently completed clinical trials that may be relevant to this review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they: (1) targeted children and/or adolescents under the age of 19, (2) examined a psychosocial intervention (i.e., medication trials were excluded) specifically designed to treat SITBs, (3) measured a specific SITB outcome, (4) included a control or comparison group to the experimental intervention, (5) randomly assigned participants to treatment groups, and (6) included sample sizes larger than or equal to 20 subjects per group at the point of randomization (Hsu, 2016). First, we restricted our review to interventions that explicitly targeted children and adolescents. Given that SITBs are relatively rare in childhood, most studies focused on treating SITBs in adolescents. A few studies included children as young as age 10 (Asarnow et al., 2011; Harrington et al., 1998; Huey et al., 2004). Some of the reviewed studies included participants who were older than 19 years of age (Morthorst, Krogh, Erlangsen, Alberdi, & Nordentoft, 2012; Robinson et al., 2012; Rudd et al., 1996). However, these studies were only included if they assessed a SITB outcome in a subset of participants who were younger than 19.

Second, and consistent with the 2015 review (Glenn et al., 2015), we elected to only include interventions specifically designed to treat SITBs in at-risk youth. Thus, we excluded treatments that were designed to treat specific psychiatric disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder, major depressive disorder) and school-based prevention programs. The rationale for this decision was twofold. First, SITBs are transdiagnostic, and as such, we did not want to include studies in which participants were recruited based on a particular diagnostic status. Doing so would give preferential attention to treatments for some disorders over others, which would potentially bias our review of existing evidence. Second, we excluded school-based prevention programs, as such programs are generally aimed to prevent incidents or reduce overall rates of SITBs in a group that includes both at-risk and healthy youth, rather than to intervene among youth who were already determined to be at high-risk (for reviews of prevention programs: see Katz et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2013; Singer, Erbacher, & Rosen, 2018).

Third, we included studies that reported at least one of the following specific SITB outcomes: (a) suicide ideation (SI: active thoughts of ending one’s life), (b) suicide attempts (SAs: self-injurious behavior engaged in with some intent to die), (c) suicide-related behavior (SRB: refers collectively to suicide ideation, plans/preparations, and attempts), (d) nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI: self-injurious behavior engaged in without intent to die), or (e) deliberate self-harm (DSH: refers collectively to self-injurious behaviors performed with OR without intent to die). Our search also included studies that examined suicide planning and suicide gestures, but no such studies met the other inclusion criteria for the current review. It is important to note that most studies in this review recruited youth based on prior history of SITBs. Thus, treatment efficacy for most studies was evaluated by examining between-group differences in the recurrence of SITBs over the treatment period (e.g., repetition of DSH, suicide reattempts). Moreover, because our review was focused on treatments for SITBs, we report changes in SITB outcomes specifically, and not changes in all potentially relevant clinical symptoms or indices of functioning/impairment.

Finally, the current review focused on RCTs with sample sizes of at least 20 subjects per group (at randomization). We chose to exclude studies with smaller sample sizes due to problems of group nonequivalence that often arise in such cases (Hsu, 2016). That is, when groups have small sample sizes, random assignment often fails to account for all possible nuisance variables. Thus, any differences that are detected between groups may be due to factors other than the effects of the treatment under investigation. We do note, however, promising randomized trials that included smaller sample sizes where relevant.

Evaluation criteria

Psychosocial interventions were evaluated using the JCCAP Evidence Base Update EBT evaluation criteria (see Table 1). JCCAP uses a 5-level ranking system (Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014), adapted from the APA Division 12 Task Force on the Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures to determine intervention potency (Chambless et al., 1998; Chambless & Hollon, 1998; Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008). Using these criteria, intervention efficacy is evaluated by the number and quality of studies. RCTs are the highest-quality studies comparing the experimental treatment to another active treatment/psychological placebo or to a wait list/no treatment control. Table 1 displays the criteria for the five levels of treatment efficacy—Level 1: Well-established, Level 2: Probably efficacious, Level 3: Possibly efficacious, Level 4: Experimental, and Level 5: Questionable efficacy.

Table 1.

JCCAP Evidence Base Updates EBT Evaluation Criteria.

| Methods criteria |

| M.1. Group design: Study involved a randomized controlled design |

| M.2. Independent variable defined: Treatment manuals or logical equivalent were used for the treatment |

| M.3. Population clarified: Conducted with a population, treated for specified problems, for whom inclusion criteria have been clearly delineated |

| M.4. Outcomes assessed: Reliable and valid outcome assessment measures gauging the problems targeted (at a minimum) were used |

| M.5. Analysis adequacy: Appropriate data analyses were used and sample size was sufficient to detect expected effects |

| Level 1: Well-Established Treatments |

| Evidence criteria |

| 1.1 Efficacy demonstrated for the treatment by showing the treatment to be either: |

| 1.1.a. Statistically significantly superior to pill or psychological placebo or to another active treatment |

| OR |

| 1.1.b. Equivalent (or not significantly different) to an already well-established treatment in experiments |

| AND |

| 1.1c In at least two (2) independent research settings and by two (2) independent investigatory teams demonstrating efficacy |

| AND |

| 1.2 All five (5) of the Methods Criteria |

| Level 2: Probably Efficacious Treatments |

| Evidence criteria |

| 2.1 There must be at least two good experiments showing the treatment is superior (statistically significantly so) to a wait-list control group |

| OR |

| 2.2 One (or more) good experiments meeting the Well-Established Treatment level except for criterion 1.1c (i.e., Level 2 treatments will not involve independent investigatory teams) |

| AND |

| 2.3 All five (5) of the Methods Criteria |

| Level 3: Possibly Efficacious Treatments |

| Evidence criterion |

| 3.1 At least one good randomized controlled trial showing the treatment to be superior to a wait list or no-treatment control group |

| AND |

| 3.2 All five (5) of the Methods Criteria |

| OR |

| 3.3 Two or more clinical studies showing the treatment to be efficacious, with two or more meeting the last four (of five) Methods Criteria, but none being randomized controlled trials |

| Level 4: Experimental Treatments |

| Evidence criteria |

| 4.1. Not yet tested in a randomized controlled trial |

| OR |

| 4.2. Tested in 1 or more clinical studies but not sufficient to meet level 3 criteria. |

| Level 5: Treatments of Questionable Efficacy |

| 5.1. Tested in good group-design experiments and found to be inferior to other treatment group and/or wait-list control group; i.e., only evidence available from experimental studies suggests the treatment produces no beneficial effect. |

Adapted from Silverman and Hinshaw (2008) and Division 12 Task Force on Psychological Interventions’ reports (Chambless et al., 1996, 1998), from Chambless and Hollon (1998), and from Chambless and Ollendick (2001). Chambless and Hollon (1998) described criteria for methodology.

For JCCAP Evidence Base Updates, interventions are classified into broad families of treatments based on the type and mode of treatment (e.g., Cognitive behavioral therapy—Individual) rather than by treatment “brand names” (e.g., Reframe-IT; Hetrick et al., 2017). The rationale for this classification is provided in Southam-Gerow and Prinstein (2014). It is important to note that some of the treatment family names have changed since the 2015 review to best reflect the RCTs included in this updated review. When applicable, we note both the old and new treatment family names.

Evaluations of treatment families were made by two authors (CG, EE, DP) independently with discrepancies resolved in consensus coding meetings with all three authors. For treatment families with mixed results, we evaluated whether the majority of evidence suggests an intervention is efficacious (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). If comparable designs yielded conflicting findings, we evaluated interventions conservatively and did not classify them as Level 1: Well-established or Level 2: Probably efficacious. We were also conservative when classifying interventions as Level 5: Questionable efficacy and only did so when there were at least two trials indicating that the experimental intervention was not beneficial as compared to the control/comparison treatment group.

In the sections that follow, we review the existing RCTs testing treatments for SITBs in youth in two ways. Consistent with the guidelines for JCCAP Evidence Base Updates, we review and evaluate the broad treatment families (type and mode) using the JCCAP criteria in Table 1. However, we recognize that this classification method requires collapsing across different types of interventions, thereby minimizing differences across treatment programs that may be important. Therefore, we also discuss each individual trial using its “brand name” and specific aspects of the treatment package and trial that may be important for evaluating its efficacy.

Review of Interventions for Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors

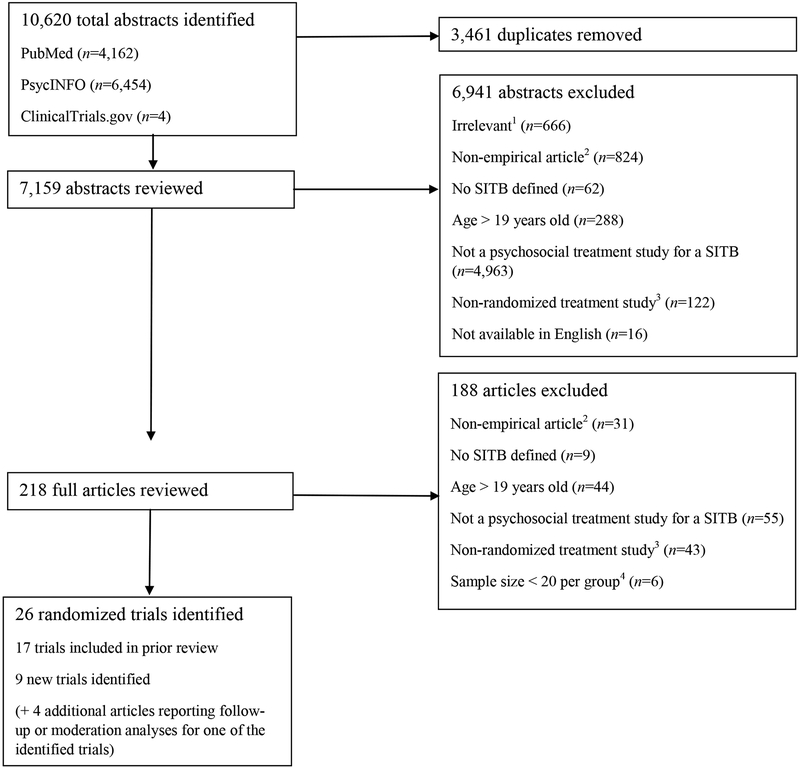

Based on the review parameters described above, our comprehensive search yielded 26 RCTs of psychosocial interventions for youth SITBs: 17 RCTs were included in the 2015 review and 9 RCTs are new to this review (see Figure 1 PRISMA diagram). Table 2 provides the following detailed information for each trial: sample size, sample demographic characteristics, recruitment setting, sample inclusion and exclusion criteria, major diagnoses of the sample, SITB outcomes assessed and how they were measured, treatment type, treatment dose, number of assessments in the trial, treatment completion and study attrition (when available), and main trial results. Table 3 displays the treatment efficacy ratings for the broad treatment families and references for the trials that were evaluated when making these ratings.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for systematic literature review.

SITB=self-injurious thought and behavior

1 Irrelevant refers to abstracts that resulted from the search terms but were not relevant for our review (e.g., cell death, suicide gene, general mortality data, medical procedures referred to as “cutting-edge”).

2 Non-empirical refers to review papers, opinion pieces, commentaries, and procedure descriptions.

3 Non-randomized treatment study refers to case studies, pilot studies, or non-randomized control studies.

4 Studies with less than 20 subjects per group were removed due to the increased likelihood of nonequivalence between groups (Hsu, 2016).

Table 2.

Randomized Trials of Psychosocial Interventions for Self-injurious Thoughts and Behaviors in Youth.

| Treatment Family | Citation | Sample Size (at randomization) | Sample Characteristics | Recruitment Setting | Inclusion (In) and Exclusion (Ex) Criteria | Major Diagnoses | SITB Outcomes (Measures) |

Treatment Conditions, Dose, and Assessments | Treatment Attrition and Completion (if available) | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBT-A | McCauley et al. (2018) | 173; T=86, C=87 |

12–18 years old; 95% female; 56% Caucasian, 27% Hispanic, 7% African American, 6% Asian American, <1% Native American, 2% other | ED, inpatient, outpatient, community | In: Lifetime SA≥1; elevated past-month SI (SIQ-Jr≥24); DSH lifetime≥3 episodes + at least 1 DSH episode in past 12 weeks; meet at least 3 BPD criteria Ex: IQ<70; psychosis; mania; AN; life-threatening condition; youth not fluent in English; parent not fluent in English or Spanish |

MDD (84%); ANX (54%); BPD (53%); ED (<1%) |

SI (SIQ-Jr); SA (SASII); NSSI (SASII); DSH (SASII) |

T: DBT-A (individual sessions, multifamily group skills training, youth and parent telephone coaching, individual parent session, family sessions [as needed]); Dose: 6 months of weekly individual and group sessions, weekly therapist team consultation C: Individual and Group Supportive Therapy (IGST; individual and group sessions, parent sessions [as needed]); Dose: 6 months of weekly individual and group sessions, weekly therapist team consultation Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), mid-treatment (3 months), post-treatment (6 months), F/U at 9 and 12 months |

Treatment completion (≥24 adolescent sessions): T: 45.4% C: 16.1% Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 10.5% C: 24.1% 12-month F/U: T: 19.8% C: 26.4% |

Significantly greater decrease in SI and SA, NSSI, and DSH frequency for T as compared to C at post-treatment. NS between group differences in SI, SA, NSSI, or DSH from post-treatment to 12-month F/U. |

| DBT-A | Mehlum et al. (2014; 2016) | 77; T=39, C=38 |

12–18 years old; 88% female; 85% Norwegian | Outpatient | In: Lifetime DSH≥2 episodes + at least 1 DSH episode in past 16 weeks; at least 2 DSM-IV BPD criteria or 1 BPD criterion + 2 sub-threshold-level criteria; fluent in Norwegian Ex: BP; SZ; SCAD; psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; intellectual disability; Asperger syndrome |

ANX (43%); Other depressive disorder (38%); MDD (22%); BPD (21%); PTSD (17%); PD (9%); ED (8%); SUD (3%) |

DSH (LPC); SI (SIQ-Jr) |

T: DBT-A (individual sessions, multifamily skills training, family therapy or telephone coaching [as needed]); Dose: 19 weeks of weekly individual sessions (1 hour), weekly multi-family skills training (1.5 hours) C: EUC (TAU + therapists agreed to minimum dose); Dose: 19 weeks (minimum) of weekly individual sessions Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 9 and 15 weeks (during treatment), post-treatment (19 weeks), F/U at 71 weeks (1-year post-treatment) |

Treatment completion (≥ 50% of sessions): T: 74.4% C: 71% Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 0% C: 0% 71-week F/U: T: 2.6% C: 2.6% |

Significantly fewer DSH episodes and significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at post-treatment. Significantly fewer DSH episodes in T as compared to C from post-treatment to 71-week F/U. NS between group differences in SI at 71-week F/U. |

| CBT—Individual | Hetrick et al. (2017) | 50; T=26, C=24 |

13–19 years old; high school students; 82% female; race/ethnicity NR | High school | In: High school student; engaged with a well-being staff member (i.e., school counselor); experienced any level of SI in past 4-week period Ex: Intellectual disability; psychotic symptoms; youth not fluent in English |

NR | SI (SIQ); SA (2-item questionnaire) |

T: Reframe-IT (online CBT modules), TAU; Dose: 8 modules of CBT delivered over 10 weeks C: TAU (contact with school well-being staff, outpatient mental health counseling and medication management); Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), post-treatment (10 weeks), F/U at 22 weeks |

Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 30.8% C: 12.5% 22-week F/U: T: 50% C: 29.2% |

NS between group differences in SI or SA from BL to post-treatment or BL to 22-week F/U. |

| CBT— Individual + Family | Esposito-Smythers, Spirito, Kahler, Hunt, & Monti (2011)1 | 40; T=20, C=20 |

13–17 years old; 67% female; 89% Caucasian, 14% Hispanic | Inpatient | In: SA in past 3 months or significant SI (SIQ-Sn≥41); AUD or CUD; lived in the home with a parent/guardian willing to participate Ex: Verbal IQ<70; active psychosis; current homicidal ideation; BP; SUD other than AUD or CUD |

UMD (94%); CUD (83%); AUD (64%); ANX (56%); DBD (50%) |

SA (K-SADS-PL; depression module suicide items); SI (SIQ-Sn) |

T: Integrated CBT for AUD/SUD and suicide (CBT skills, family and parent training, [1] MI session), 18 months of free medication management; Dose: 6 months of weekly individual and weekly-biweekly parent sessions, 3 months of biweekly individual and biweekly-monthly parent sessions, 3 months of monthly individual sessions (monthly parent sessions as needed), conjoint family sessions as needed C: Enhanced TAU – diagnostic evaluation, offer for 18 months of free medication management, community-based TAU; Dose: Varied over 12 months Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months post-enrollment |

Treatment completion (≥24 adolescent sessions, ≥12 parent sessions): T: 74% adolescents + 90% parents C: 44% adolescents + 25% parents Attrition: 18-month F/U: T: 25% C: 15% |

Significantly fewer T participants made a SA as compared to C over 18-month F/U. NS between group difference in SI over 18-month F/U. |

| IPT-A—Individual | Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang, & Yen (2009)1 | 73; T=35, C=38 |

12–18 years old; high school students; 66% female; race/ethnicity NR (study conducted in Taiwan) | High school | In: Moderate to severe MDD (BDI>19); SI or lifetime history of SA (BSS>0); moderate to severe ANX (BAI>16); significant hopelessness (BHS>8) in past 2 weeks Ex: Acute psychosis; drug abuse; PD; serious medical condition; severe (e.g., high-lethality) suicidal behaviors; lack of proper care for suicidal risk by family |

MDD (100%) | SI (BSS) |

T: Intensive Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicide risk (IPT-A-IN; school-based intervention); Dose: 2 sessions weekly, 30-minute phone F/U for 6 weeks C: TAU in schools (psychoeducation, irregular supportive counseling [parent included as needed]); Dose: 30- to 60-minute sessions once or twice weekly for 6 weeks Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), post-treatment (6 weeks) |

Treatment completion: T: 100% C: 92.1% Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 0% C: 7.9% |

Significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at post-treatment. |

| Psychodynamic Therapy —Individual + Family | Rossouw & Fonagy (2012)1 | 80; T=40, C=40 |

12–17 years old; 85% female; 75% Caucasian, 10% Asian, 5% African American, 8% mixed race, 3% other | ED, community mental health | In: ≥1 DSH episode in past month Ex: Required inpatient care; ED (in the absence of self-harm); PDD; psychosis; severe learning disability (IQ<65); chemical dependence |

MDD (96%); BPD (73%); Alcohol problems (44%); Substance misuse (28%) |

DSH (RTSHI) |

T: Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT-A; individual + family therapy) for self-harm; Dose: Weekly individual + monthly family therapy for 12 months C: Community-based TAU (varied, [e.g., individual counseling, family therapy]); Dose: 12 months, varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), 3, 6, and 9 months after randomization, post-treatment (12 months) |

Treatment completion: T: 50% C: 42.5% Attrition: 3-month F/U: T: 13% C: 8% 6-month F/U: T: 3% C: 10% 9-month F/U: T: 13% C: 15% 12-month F/U: T: 10% C: 13% |

Significantly greater decrease in DSH (RTSHI scores) for T as compared to C at post-treatment. Significantly lower odds of reporting ≥ 1 DSH episode in past 3 months for T as compared to C at post-treatment. Significantly greater rate of decline in DSH (RTSHI scores) for T as compared to C over treatment period. |

| Psychodynamic Therapy—Family-Based | Diamond et al. (2010)1 | 66; T=35, C=31 |

12–17 years old; 83% female; 74% African American | ED, primary care | In: SI (SIQ-Jr>31) and moderate depression (BDI-II >20) at 2 pre-BL screenings Ex: Needed psychiatric hospitalization; recent discharge from psychiatric hospital; psychosis; mental retardation or borderline intellectual functioning |

ANX (67%); ADHD or DBD (58%); MDD (39%) |

SI (SIQ-Jr, self-report; SSI, clinician-report) | T: Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT; individual youth and parent sessions, joint parent-youth sessions); Dose: Weekly sessions for 3 months C: Enhanced TAU (E-TAU; referral to care, clinical monitoring); Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), mid-treatment (6 weeks), post-treatment (12 weeks), F/U at 24 weeks |

Treatment completion: ≥ 1 session: T: 91.4% C: 67.7% ≥ 6 sessions: T: 68.6% C: 19.4% ≥ 10 sessions: T: 62.9% C: 6.5% Attrition: Mid-treatment: T: 5.7% C: 12.9% Post-treatment: T: 11.4% C: 6.5% 24-week F/U: T: 11.4% C: 16.1% |

Significant decrease in SI (self- and clinician-reported) for T as compared to C at post-treatment and 24-week F/U. Significantly greater rate of change in SI over treatment period for T as compared to C. Significantly greater proportion of T reported no past-week SI as compared to C at post-treatment and 24-week F/U (self- and clinician-reported). |

| Psychodynamic Therapy — Family-Based | Diamond et al. (2018) | 129; T=66, C=63 |

12–18 years old; 82% female; 50% African American, 29% Caucasian, 2% Asian, 2% American Indian or Alaskan Native, <1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 8% mixed race, 9% other; 31% identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual | ED, inpatient, mental health agencies, primary care, schools, community | In: SI (SIQ-Jr≥31) and moderate depressive symptoms (BDI-II >20) at 2 pre-BL screenings Ex: Imminent risk of harm to self or others; psychosis; severe cognitive impairment; start psychiatric medication within 3-weeks of BL; parent not fluent in English |

ANX (47%); MDD (41%) |

SI (SIQ-Jr); SA (C-SSRS); NSSI (C-SSRS) |

T: Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT; individual youth and parent sessions, joint parent-youth sessions); Dose: 16 weeks C: Family-enhanced nondirective supportive therapy (FE-NST; individual youth and parent sessions, joint parent-youth sessions); Dose: 16 weekly individual sessions, 1 joint youth-parent session, 4 parent education sessions Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), post-treatment (4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks), (F/U data collected at 24, 32, 40, and 52 weeks not reported here) |

Treatment completion: T: 81.8% C: 82.5% Attrition: T: 18.2% C: 17.5% |

NS between group differences in rate of change of SI, SI remission rate (SIQ-Jr <12), and SI response rate (≥50% decrease from BL SIQ-Jr) over treatment period. NS between group difference in SA over treatment period. |

| Family Therapy | Cottrell et al. (2018) | 832; T=415, C=417 |

11–17 years old; 89% female; race/ethnicity NR | Mental health services | In: ≥2 DSH episodes prior to referral to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS); living with primary caregiver willing to participate Ex: Severe suicide risk; ongoing child protection investigation; pregnancy; treatment by CAMHS specialist; residence in short-term foster care; learning disabilities; involvement in another study in past 6 months; sibling participation in other CAMHS family therapy trial; youth not proficient in English |

NR | SI (BSS); DSH (SASII) |

T: Self-Harm Intervention Family Therapy (SHIFT); Dose: 6–8, 1.25-hour sessions over 6 months C: TAU; Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 1 session): T: 94.9% C: 81.3% Attrition: 3-month F/U: T: 45.1% C: 52.5% 6-month F/U: T: 50.8% C: 64.3% 12-month F/U: T: 40.2% C: 54.7% 18-month F/U: T: 50.8% C: 60.4% Withdrew over F/U: T: 26% C: 46.5% |

Significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at 12-month F/U. NS between group differences in SI at 18-month F/U. NS between group differences in hospitalizations for DSH at 12- or 18-month F/U. |

| Family Therapy | Harrington et al. (1998)1 | 162; T=85, C=77 |

10–16 years old; 90% female; race/ethnicity NR | Inpatient | In: DSP Ex: DSH (other than DSP); inability to engage in family intervention; psychiatrist decided participation was contraindicated (e.g., psychosis); cases where unclear if overdose was deliberate |

MDD (67%); CD (10%) |

SI (SIQ) |

T: Family-based problem solving (youth and at least 1 parent present at all sessions), TAU; Dose: 5 home sessions C: TAU; Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 2 and 6 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 1 session): T: 74% C: NR Attrition (Total sample): 2-month F/U: 4% 6-month F/U: 8% |

NS between group difference in SI at 2- and 6-month F/U. Significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at 2- and 6-month F/U in a subsample of non-depressed adolescents. |

| Multiple Systems Therapy | Huey et al. (2004)1 | T and C sample size NR | 10–17 years old; 35% female; 65% African American, 33% Caucasian |

ED, inpatient | In: Hospitalization for SA, SI, or SP; homicidal ideation or behavior; psychosis; threat to harm self or others; Medicaid-funded or w/out health insurance; residing in non-institutional environment Ex: ASD |

NR | DSH or SA (CBCL – caregiver-reported); SA (YRBS – self-reported); SI (BSI and YRBS) |

T: Multisystemic Therapy; Dose: Daily contact if needed for 3–6 months C: Inpatient hospitalization; Dose: Daily behaviorally-based milieu program Assessments: Pre-treatment, 4 months post-recruitment, F/U at 1 year post-treatment |

NR | Reduced SAs from pre- to post-treatment in T as compared to C (YRBS only); NS for SI. |

| Integrated Family Therapy | Asarnow, Hughes, Babeva, & Sugar (2017) | 42; T=20, C=22 |

11–18 years old; 88% female; 83% Caucasian, 21% Hispanic, 12% Asian, 5% African American, 7% other; 22% identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual | ED, inpatient, partial hospitalization, outpatient | In: NSSI as primary problem (with ≥3 lifetime DSH episodes) or SA in past 3 months; stable family situation; parent willing to participate in treatment Ex: Psychosis; substance dependence; youth not fluent in English |

MDD (55%); Problematic substance use (48%) |

SA (C-SSRS); DSH (C-SSRS) |

T: Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths (SAFETY; youth and parent individual sessions + joint parent-youth sessions; CBT + DBT skills + homework); Dose: 12 weeks C: Enhanced TAU (E-TAU; in-clinic parent session, phone calls ensuring treatment adherence); Dose: In-clinic parent session and >3 telephone calls Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 3 months and between 6 and 12 months |

Treatment completion: T (9–12 sessions): 70% C: 95.5% received in-clinic parent session (M=1.56 F/U calls) Attrition (Youth report): T: 0% C: 45% |

Significantly longer time to first SA for T as compared to C over 3-month F/U. NS between group differences in NSSI or in time to first NSSI event at any F/U time point. |

| Brief Family-Based Therapy | Asarnow et al. (2011)1 | 181; T=89, C=92 |

10–18 years old; 69% female; 45% Hispanic, 33% Caucasian, 13% African American, 9% other |

ED | In: Presented to ED with SA and/or SI Ex: Acute Psychosis; symptoms or other factors that interfered with ability to provide consent; no parent/guardian to provide consent; youth not fluent in English |

UMD (40%) | SA (DISC-IV and HASS); SI (HASS) |

T: Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention; Dose: One family-based CBT session in ED, phone contact 48 hours post-discharge and several other times over 1 month C: Enhanced ED TAU; Dose: ED usual care, specialized staff training Assessments: Pre-treatment, F/U at 2 months |

Treatment completion: 100% Attrition: 2-month F/U: T: 15% C: 9% |

NS differences between groups for all SITB outcomes. |

| Brief Family-Based Therapy | Ougrin et al. (2011; 2013)1 | 69; T=35, C=34 Originally randomized 70 (35 in each group) but analysis done with 69 |

12–18 years old; 80% female; 53% Caucasian, 20% African American, 11% Asian | Mental health services | In: Recent DSH or DSP but not currently receiving psychiatric services Ex: Gross reality distortion; history of at least moderately severe intellectual disability; imminent violence or suicide risk; need for inpatient psychiatric admission; youth not fluent in English |

EMD (60%); DBD (13%) |

DSH (accident and ED reports and patient health records) | T: Therapeutic Assessment; Dose: 1-hour Psychosocial history and risk assessment (“Assessment as Usual” per NICE guidelines), 30-minute session using cognitive analytic therapy paradigm with family C: Assessment as Usual; Dose: 1-hour Psychosocial history and risk assessment Assessments: Data on SITB outcomes were collected 2 years post-intervention via electronic hospital, primary care, and patient health records |

Treatment completion: 100% Attrition: F/U: T: 6% C: 9% |

NS between groups for all DSH outcomes. |

| Parent Training | Pineda & Dadds (2013)1 | 48; T=24, C=24 |

12–17 years old; T: 73% female; C: 78% female; T: 64% Caucasian, 27% mixed race; C: 50% Caucasian, 44% mixed race | ED | In: Residing with at least one parent; ≥1 SITBs in past two months; primary diagnosis of MDD, PTSD, or ANX Ex: PDD; psychosis; poisoning from recreational drugs |

MDD (100%); At least 2 psychiatric diagnoses (38%) |

SITB (ASQ-R) | T: Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program (RAP-P); Dose: Four 2-hour sessions weekly or biweekly, crisis management and safety planning, parents invited to all programs C: TAU; Dose: Varied outpatient treatment, family intervention limited to crisis management and safety planning only Assessments: Pre- and post-treatment, F/U at 6 months |

Treatment completion (all four sessions): 100% Attrition: 6-month F/U: T: 8.3% C: 25% |

Reduced SITBs in T as compared to C from pre- to post-treatment; reductions maintained at 6-month F/U. |

| Support-Based Therapy | King et al. (2006)1 | 289; T=151, C=138 |

12–17 years old; 68% female; 82% Caucasian, 10% African American, 7% other | Inpatient | In: Recent psychiatric hospitalization; past month SA or SI; CAFAS self-harm subscale = 20 or 30 Ex: Psychosis; severe mental disability |

NR | SI (SIQ-Jr, SSBS); SA (SSBS) |

T: Youth-nominated Support Team-I + TAU (varied); Dose: Psychoeducation for supports, weekly contact between supports and adolescents, supports contacted by intervention specialists over 6 months C: TAU (varied); Dose: 6 months Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), post-treatment (6 months) |

Treatment completion: T: 76% C: 87% Attrition: T: 25.1% C: 10.9% |

NS between group differences in SI and the proportion of participants reporting ≥ 1 SA at post-treatment. Significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at post-treatment in a subsample of female adolescents. |

| Support-Based Therapy | King et al. (2009)1 | 448; T=223, C=225 |

13–17 years old; 71% female; 84% Caucasian, 6% African American, 2% Hispanic, 8% other | Inpatient | In: Recent psychiatric hospitalization; past month SA or frequent (“many times”) SI Ex: Severe cognitive impairment; psychosis; medical instability; residential placement; no legal guardian available |

UMD (88%); DBD (42%); ANX (29%); PTSD or acute stress disorder (25%); AUD or SUD (21%) |

SI (SIQ-Jr); SA (DISC-IV) |

T: Youth-nominated Support Team-II, TAU (varied); Dose: Psychoeducation for supports, weekly contact between supports and adolescents for 3 months C: TAU (varied); Dose: 3 months Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), mid-treatment (6 weeks), post-treatment (3 months), F/U at 6 and 12 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 2 support people for 12 weeks): T: 74% Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 23.7% C: 21.8% 12-month F/U: T: 19.3% C: 21.8% |

Significantly greater decrease in SI for T as compared to C at mid-treatment. NS between group differences in SI at post-treatment and over 12-month F/U. NS between group differences in frequency of SA or SA rate over 12-month F/U. |

| Eclectic Group Therapy | Green et al. (2011)1 | 366; T=183, C=183 |

12–17 years old; 89% female; 94% Caucasian | Mental health service | In: ≥2 DSH episodes in past year Ex: Severe AN; active psychosis; current confinement in secure care; attendance at special learning disability school; youth not fluent in English |

UMD (62%); DBD (33%) |

DSH (interview validated in Harrington et al., 1998); SI (SIQ) |

T: DGT (see Wood et al., 2001), TAU; Dose: (see Wood et al.) C: TAU, no group therapy permitted during trial; Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 6 and 12 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 5 sessions): T: 79% C: 63% Attrition: T: 1.6% C: 2.3% |

NS between group differences in frequency of DSH, severity of DSH, or SI at 6- and 12-month F/U. |

| Eclectic Group Therapy | Hazell et al. (2009)1 | 72; T=35, C=37 |

12–16 years old; 90% female; race/ethnicity NR | Mental health service | In: ≥2 DSH episodes in past year + at least 1 DSH episode in past 3 months Ex: More intensive treatment required; active psychosis; inability to attend groups; intellectual disability |

MDD (57%); DBD (7%); Alcohol problems (4%) |

DSH (PHI); SI (SIQ) |

T: DGT (see Wood et al.) + TAU; Dose: 1 hour/week for 6 sessions for up to 1 year (see Wood et al.) C: TAU (individual or family sessions); Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 2, 6, and 12 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 4 sessions): T: 71.4% C: 62.2% Attrition: T: 2.8% C: 8.1% |

Significantly more participants in T reported DSH behavior as compared to C at 6-month F/U. NS between group difference in the proportion of participants reporting DSH behavior between 6- and 12-month F/U. NS between group differences in the proportion of participants engaging in >1 DSH episode between BL and 6-month F/U or between 6- and 12-month F/U. NS between group difference in SI over 12-month F/U. |

| Eclectic Group Therapy | Rudd et al. (1996)1 | 264; T=143, C=121 |

15–24 years old; 18% female; 61% Caucasian, 26% African American, 11% Hispanic | Mental health service | In: Previous SA; UMD + SI; AUD + SI Ex: SUD or chronic abuse; psychosis or thought disorder; severe PD |

MD (72%); AUD (44%); ANX (37%) |

SI (MSSI) | T: Time-limited CBT group therapy (psychoeducation classes, problem-solving group, experiential-affective group, homework), TAU; Dose: 9 hours daily for 2 weeks C: TAU (inpatient, outpatient); Dose: Varied combination of individual and group therapy Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), post-treatment (1 month), F/U at 6 and 12 months (18- and 24-month F/U data not reported here) |

Treatment completion: T: 79% C: NR Attrition: Post-treatment: T: 16.1% C: 24.8% 6-month F/U: T: 47.6% C: 54.5% 12-month F/U: T: 67.8% C: 79.3% |

NS between group differences in SI at post-treatment and at 6- and 12-month F/U. |

| Eclectic Group Therapy | Wood, Trainor, Rothwell, Moore, & Harrington (2001)1 | 63; T=32, C=31 |

12–16 years old; 78% female; race/ethnicity NR | Mental health service | In: ≥1 DSH episode in past year; referred to mental health services following DSH incident Ex: Severe suicide risk; inability to attend groups; psychosis; significant learning problems |

MDD (83%); DBD (67%) |

DSH (interview-see Kerfoot, 1984); SI (SIQ) |

T: Developmental group psychotherapy (DGT; acute and long-term groups, individual sessions [as needed]), TAU; Dose: 6 acute sessions, weekly long-term group as needed for 6 months C: TAU; Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 6 weeks and 7 months |

Treatment completion (≥ 4 sessions): T: 71.9% C: 61.3% Attrition: 7-month F/U: T: 3.1% C: 0% |

Significantly greater decrease in DSH episodes for T as compared to C. Significantly longer time to first DSH episode for T as compared to C over 7-month F/U. NS between group differences in SI at post-treatment and at 7-month F/U. |

| Resource Intervention | Cotgrove, Zirinsky, Black, & Weston (1995)1 | 105; T=47, C=58 |

12–16 years old; 85% female; race/ethnicity NR | Inpatient | In: Admitted for DSH, DSP, or SA Ex: NR |

NR | SA (unspecified psychiatrist questionnaire) | T: Green card for re-admission to the hospital C: Clinic or child psychiatry department TAU Assessments: Pre-treatment and F/U at 1 year |

Treatment completion: T: 11% used green card Attrition: Total sample: 0% |

NS between group differences in SA (statistically), but some lower rates of SA in treatment group. |

| Resource Intervention | Morthorst, Krogh, Erlangsen, Alberdi, & Nordentoft (2012) | 243; T=123, C=120 |

≥ 12 years old; 76% female; 68% Danish, 14% Middle Eastern, 8% European and American, 10% other | ED, intensive care, pediatric units | In: Admitted to hospital after SA (within past 14 days); self-injuries included if they met WHO definition of SA Ex: Admitted to psychiatric ward for more than 14 days after attempt; SZ spectrum disorders; severe MDD; severe BP; severe dementia; needed inpatient care; receiving outreach services from social services; living in institutions |

NR | SA (unspecified self-report) | T: Assertive Intervention for Deliberate Self-harm (AID), TAU; Dose: 8–20 outreach consultations over 6 months C: TAU; Dose: Optional 6–8 sessions for those not receiving other care Assessment: Pre-treatment, F/U at 1 year |

Treatment completion: T: 96% C: 100% Attrition: F/U: T: 22.8% C: 38.3% |

NS between rates of subsequent suicide attempts in treatment and control groups. |

| Resource Intervention | Robinson et al. (2012)1 | 164; T=81, C=83 |

15–24 years old; 65% female; race/ethnicity NR | Community | In: Living inside target area; did not meet entry criteria for mental health service; history of DSH or SRB Ex: Known organic cause for DSH/SRB; intellectual disability; youth not fluent in English |

MD (67%); ANX (63%); SUD (25%) |

DSH (SBQ-14, BRFL-Adolescent); SA (SBQ-14, BRFL-Adolescent); SI (BSS) |

T: Post cards promoting well-being and evidence-based skills use, community-based TAU; Dose: Monthly for 12 months C: Community-based TAU; Dose: 12 months Assessments: Pre-treatment, F/U at 12 and 18 months |

Attrition: 12-month F/U: T: 25.9% C: 37.4% 18-month F/U: T: 38.3% C: 55.4% |

Reduced DSH and SI in both groups, but NS between groups. |

| Motivational Interviewing | King et al. (2015) | 49; T=27, C=22 |

14–19 years old; 80% female; 57% African American, 39% Caucasian, 4% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 2% Hispanic, 2% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 2% other | ED | In: Positive suicide risk screen (SI, recent SA, or depression and substance abuse); presented with non-psychiatric complaint Ex: Level 1 trauma; significant cognitive impairment; psychiatric hospitalization |

NR | SI (SIQ-Jr) | T: Teen Options for Change (TOC); Dose: Crisis card + resources, feedback on screenings, 35–45 minute adapted motivational interview C: Enhanced TAU (crisis card for suicidal emergency support) Assessments: Pre-treatment (BL), F/U at 2 months |

Treatment completion: Total: 85% Attrition: Total: 6% |

NS between-group differences in SI. |

| Brief Skills Training | Kennard et al. (2018) | 66; T=34, C=32 |

12–18 years old; 89% female; 77% Caucasian | Inpatient | In: Presented to psychiatric inpatient unit with recent SP or recent SA Ex: Needed residential treatment; active involvement in child protective services; mania; psychosis; autism; intellectual disability |

MDD (86%); Of those with MDD, 58% had a comorbid ANX |

SI (SIQ-Jr); SA (C-SSRS); NSSI (C-SSRS) |

T: As Safe as Possible (ASAP), TAU; Dose: 3-hour ASAP intervention, BRITE app use C: TAU; Dose: Varied Assessments: Pre-treatment, F/U at 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-discharge |

Treatment completion: Varies based on treatment component Attrition: 4-week F/U: T: 8.8% C: 21.9% 12-week F/U: T: 20.6% C: 28.1% 24-week F/U: T: 17.6% C: 18.8% |

NS for all SITB outcomes. |

BL=baseline assessment; ED=emergency department; F/U=follow-up; NR=not reported; NS=non-significant

Major Diagnoses: ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AN=anorexia nervosa; ANX=anxiety disorder–type not specified; ASD=autism spectrum disorder; AUD=alcohol use disorder; BP=bipolar disorder; BPD=borderline personality disorder; CD=conduct disorder; CUD=cannabis use disorder; DBD=disruptive behavior disorder; ED=eating disorder; EMD=emotional disorder; MD=mood disorder (bipolar or unipolar); MDD=major depressive disorder; PD=personality disorder; PDD=pervasive developmental disorder; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; SCAD=schizoaffective disorder; SUD=substance use disorder; SZ=schizophrenia; UMD=unipolar mood disorder

Measures: ASQ-R=Adolescent Suicide Questionnaire Revised; BAI=Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; BHS=Beck Hopelessness Scale; BRFL=Brief Reasons for Living Inventory; BSI=Brief Symptom Inventory; BSS=Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; CAFAS=Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale; CBCL=Children Behavior Checklist; C-SSRS=Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; DISC-IV=Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV; HASS=Harkavy-Asnis Suicide Scale; K-SADS-PL=Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version; LPC=Lifetime Parasuicide Count; MSSI=Modified Scale for Suicide Ideation; PHI=Parasuicide History Interview; RTSHI=Risk Taking and Self Harm Inventory; SASII=Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview; SBQ-14=Suicide Behavior Questionnaire; SIQ (Jr or Sn)=Suicide Ideation Questionnaire; SSBS=Spectrum of Suicide Behavior Scale; SSI=Scale for Suicidal Ideation; YRBS=Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Self-Injurious Outcomes: DSH=deliberate self-harm; DSP=deliberate self-poisoning; NSSI=nonsuicidal self-injury; SA=suicide attempt; SI=suicide ideation; SITB=self-injurious thought or behavior (suicidal and nonsuicidal); SP=suicide planning or preparation; SRB=suicide-related behavior (suicide thoughts, plans, attempts)

Treatments and Conditions: C=control or comparison group; CBT=Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; DBT-A=Dialectical Behavior Therapy for adolescents; EUC=Enhanced Usual Care; IPT-A=interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents; MI=Motivational Interviewing; T=experimental treatment group; TAU=treatment as usual

Trial was included in the prior JCCAP Evidence Base Update (Glenn et al., 2015).

Table 3.

Efficacy of Psychosocial Treatments for Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors in Youth: Summary1

| Level 1: Well-Established |

Level 2: Probably Efficacious |

Level 3: Possibly Efficacious |

Level 4: Experimental |

Level 5: Questionable Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DBT-A (DSH, SI) McCauley et al. (2018) Mehlum et al. (2014) |

DBT-A (NSSI, SA) McCauley et al. (2018) CBT–Individual + Family (SA) Esposito-Smythers et al. (2011) Integrated Family Therapy (SA) Asarnow et al. (2017) IPT-A–Individual (SI) Tang et al. (2009) Psychodynamic Therapy–Individual + Family (DSH) Rossouw & Fonagy (2012) Parent Training (SITB) Pineda & Dadds (2013) |

Multiple Systems Therapy (SA) Huey et al. (2004) |

CBT–Individual (SA, SI) Hetrick et al. (2017) CBT–Individual + Family (SI) Esposito-Smythers et al. (2011) Psychodynamic Therapy–Family-Based Diamond et al. (2010) (SI) Diamond et al. (2018) (SA, SI) Integrated Family Therapy (NSSI) Asarnow et al. (2017) Family Therapy Harrington et al. (1998) (SI) Cottrell et al. (2018) (DSH, SI) Multiple Systems Therapy (SI) Huey et al. (2004) Brief Family-Based therapy Asarnow et al. (2011) (SA, SI) Ougrin et al. (2013) (DSH) Support-Based Therapy (SI) King et al. (2006) King et al. (2009) Brief Skills Training (NSSI, SA, SI) Kennard et al. (2018) Motivational Interviewing (SI) King et al. (2015) Resource Interventions (DSH, SI) Robinson et al. (2012) |

Eclectic Group Therapy Green et al. (2011) (DSH, SI) Hazell et al. (2009) (DSH, SI) Rudd et al. (1996) (SI) Wood et al. (2001) (DSH, SI) Support-Based therapy (SA) King et al. (2006) King et al. (2009) Resource Intervention (SA) Cotgrove et al. (1995) Morthorst et al. (2012) Robinson et al. (2012) |

Treatments: CBT=Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; DBT-A=Dialectical Behavior Therapy for adolescents; IPT-A=interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents

Self-Injurious Outcomes: DSH=deliberate self-harm; NSSI=nonsuicidal self-injury; SA=suicide attempt; SI=suicide ideation; SITB=self-injurious thought or behavior (suicidal and nonsuicidal)

For each treatment family, the SITB outcomes examined in the relevant trials are listed in parentheses. In cases where efficacy ratings for a specific SITB outcome were based on a subset of articles in a broader treatment family, the SITB outcomes are listed separately for each contributing trial. For some treatments, there are different efficacy ratings based on the SITB outcome. In these cases, a treatment family may appear twice in the summary table illustrating a different level of evidence for a specific SITB outcome (e.g., DBT-A Level 1 for DSH and SI; Level 2 for NSSI and SA).

Five considerations should be kept in mind when evaluating the treatment literature. First, broad classification of interventions based on treatment type and mode were complicated in a number of ways. Most notably, categorization based on the role of the adolescent’s family was challenging as most interventions designed for youth include at least a small family component, even if primarily designed as an individual treatment package. Consistent with decisions made in the prior review (Glenn et al., 2015) and other Evidence Base Updates (e.g., Freeman et al., 2014), we classified interventions in the following ways: (1) interventions in which the adolescent was the main target of treatment, and family sessions were optional or included as needed, were classified as individual interventions (e.g., Cognitive-behavioral therapy—Individual; Hetrick et al., 2017), (2) interventions in which individual therapy was augmented with a family component were classified as individual + family treatments (e.g., Cognitive-behavioral therapy—Individual + Family; Esposito-Smythers, Spirito, Kahler, Hunt, & Monti, 2011), and (3) interventions in which the family was the primary focus of the intervention were classified as family-based therapy (e.g., Psychodynamic therapy—Family-based; Diamond et al., 2010; 2018).

Second, although every effort was made to combine similar interventions when possible, few RCTs have examined the same intervention for SITBs in youth. Therefore, many broad treatment categories only contain a single trial.

Third, interventions included in this review targeted a range of SITBs from nonsuicidal (NSSI) to suicidal outcomes (SI, SA). The specific SITB outcomes are specified for each trial in Table 2 and treatment efficacy is evaluated with respect to each of these outcomes. This means that in some cases an intervention may have greater efficacy for reducing one SITB outcome but not a separate SITB outcome (e.g., significant reduction in SI but no significant reduction in SA).

Fourth, it is not uncommon in intervention research for both treatment groups (experimental and control/comparison groups) to exhibit a reduction in symptoms over time (e.g., regression to the mean; Morton & Torgerson, 2005). Given that our review included only RCTs, we were able to focus our evaluation on between-group differences and specifically whether the experimental treatment led to significant reductions in SITBs compared to the control/comparison treatment.

Fifth, and finally, treatment attrition is a significant concern in intervention research with youth (Kazdin, 1996), and becomes even more problematic when dropout rates differ between experimental and control groups (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). In Table 2, we provide details regarding treatment completion and study attrition when reported. Moreover, in our discussion of each trial, we examine the dropout rates for each intervention and report intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses when available. ITT analyses evaluate treatment outcomes for all youth randomized to a specific intervention group, which provides a more conservative test of a treatment’s efficacy (Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents (DBT-A)

DBT was one of the first treatments designed specifically to target SITBs (Linehan, 1993). This intervention was originally developed to treat adults with borderline personality disorder (BPD), but has since been adapted for other demographic and diagnostic groups including suicidal adolescents (DBT-A) with or without BPD (Miller, Rathus, Linehan, Wetzler, & Leigh, 1997; Rathus & Miller, 2014). The full DBT-A treatment package includes weekly individual therapy, weekly multifamily group skills training (i.e., mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness skills), telephone coaching with the therapist when needed, and weekly consultation among the treatment team. DBT aims to reduce the emotional, interpersonal, and behavioral dysregulation that leads to maladaptive behaviors, such as SITBs, and has demonstrated good efficacy in adults for reducing these outcomes (Kliem, Kröger, & Kosfelder, 2010; Linehan et al., 2006; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong, 1993).

There have been significant changes in the evaluation of this intervention for youth since the prior review. At the time of the 2015 review, no RCTs had tested the efficacy of DBT-A in youth. Therefore, the prior review evaluated DBT-A based on four pilot studies (one was a DBT skills only group) and two non-randomized trials. Based on the evidence at that time, DBT-A was evaluated as Level 4: Experimental for reducing DSH, NSSI, and SI in youth. Since the prior review, two RCTs, conducted by two independent research groups have examined a form of DBT-A for reducing SITBs in youth. Details of these trials are provided below.

In the first RCT (Mehlum et al., 2014), a shortened form of DBT-A (19 weeks vs. typical six-month package) was compared to enhanced usual care (EUC; weekly therapy ranging from psychodynamic to cognitive-behavioral therapy, plus medication as needed) among 77 adolescents with a history of repetitive DSH and BPD features who were receiving outpatient care. Over the course of treatment, the DBT-A group reported reductions in DSH that were significantly greater than those observed in the EUC group (ITT analyses). In addition, the DBT-A group also had significantly greater reduction in SI over the course of treatment, most notably at the end of the treatment period (19 weeks). Importantly, treatment effects for DSH held over a 52-week follow-up; the DBT-A group reported a significantly lower frequency of DSH over follow-up compared to the EUC group (Mehlum et al., 2016). However, between-groups differences in SI were not maintained over this follow-up period; DBT-A maintained reductions in SI but EUC also led to significantly reduced SI over the 52-week follow-up (Mehlum et al., 2016).

It is important to note a few limitations of the comparison treatment for this study. EUC required weekly individual treatment but not a group skills component, unlike the DBT-A group. Therefore, the DBT-A received a higher dose of treatment than the control group given the inclusion of a multifamily group skills component in the treatment package. In addition, EUC was not a manualized treatment nor was it monitored for fidelity, which means that control participants likely did not receive the same type or dose of treatment. Some of these limitations were addressed in a recent and independent DBT-A trial.

A second RCT compared DBT-A (six-month package) to individual and group supportive therapy (IGST, also six months) in a large (N=173) sample of adolescents with a history of suicide attempts recruited across four medical centers (McCauley et al., 2018). IGST is a manualized intervention that aims to match the dose of treatment provided in DBT-A, addressing the limitations of the control intervention used in the Mehlum et al. (2014) trial. Specifically, IGST provides individual supportive therapy (focused on validation, acceptance, and connectedness), supportive group therapy, parent sessions as needed, and therapist team consultation. Gains for DBT-A were observed across all SITB outcomes compared to the control condition from pre- to post-treatment (ITT analyses): the DBT-A group reported significantly fewer instances of DSH, NSSI, and SA and significantly greater reductions in SI from baseline to 6 months compared to the IGST group—all effects were small to moderate in size. However, these between-groups differences were not significant at the final 12-month follow-up because adolescents in both treatment conditions improved over time. Although IGST was a conservative control for DBT-A (i.e., manualized and matched in treatment length and modality), youth receiving DBT-A were more likely to participate in treatment and remained in treatment longer than in IGST. Differences in treatment engagement and retention are important to consider when evaluating intervention effects. For instance, greater treatment engagement may suggest that an intervention has more promise for being “scaled up” or easily disseminated outside of an RCT (Becker, Boustani, Gellatly, & Chorpita, 2018). Notably, a recent pilot study found initial evidence for the effectiveness of DBT-A for reducing SITBs among youth in a community clinic (Berk, Starace, Black, & Avina, 2018).

Based on these two high-quality RCTs conducted by two independent research groups, DBT is evaluated as a Level 1: Well-established intervention for reducing DSH and SI in youth (the two SITBs that were examined across both trials). NSSI and SA were examined separately in the second RCT only and therefore DBT is evaluated as a Level 2: Probably efficacious intervention for reducing NSSI and SA in youth.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBT is a short-term, problem-oriented treatment approach that aims to modify distorted cognitions and maladaptive behaviors to improve aversive emotional states. To reduce SITBs, CBT approaches focus on restructuring maladaptive thinking patterns and enhancing emotion regulation, problem-solving, and communication skills to increase adaptive coping. Some trials included in the CBT section have changed since the prior review. Given our emphasis on RCTs, we have removed discussion of the pilots and non-randomized trials from the prior review. In addition, we excluded trials with small sample sizes (< 20 adolescents per group; Hsu, 2016), which removed a number of smaller CBT trials (Alavi, Sharifi, Ghanizadeh, & Dehbozorgi, 2013; Donaldson, Spirito, & Esposito-Smythers, 2005; Högberg & Hällström, 2018; Spirito et al., 2015) from the current review. However, we discuss these trials briefly when applicable as potentially promising interventions to be explored in future research.

Based on the more stringent inclusion criteria for this review, two RCTs examining a form of CBT for reducing SITBs in youth met inclusion criteria. One trial examining CBT—Individual is new to this review and the second trial examining CBT—Individual + Family was included in the prior review.

CBT—Individual.

Since the prior review, a new RCT (Hetrick et al., 2017) has examined an internet-based CBT package for suicidal youth called Reframe-IT. Reframe-IT is a 10-week CBT package with a specific focus on SITBs. Modules delivered over the internet include behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, distress tolerance, and problem-solving skills (Robinson et al., 2014). Students with SI were recruited from schools in Melbourne, Australia and were randomly assigned to either Reframe-IT plus treatment-as-usual (TAU) or TAU only (i.e., school staff support, additional mental health support, and medication if needed). In pilot trials, Reframe-IT was determined to be safe and acceptable (Robinson et al., 2015) and significantly reduced SI in youth (Robinson et al., 2016). Although the Reframe-IT group reported larger reductions in SI over the course of treatment, the differences between treatment groups were not statistically significant post-treatment or at 22-week follow-up (ITT analyses). In addition, although fewer adolescents in the experimental treatment group attempted suicide compared to the control group, differences were not statistically significant post-treatment or at 22-week follow-up.

A few limitations of this trial are important to note when interpreting the findings. First, the trial was underpowered. The targeted sample size was 169 adolescents, but only 50 were randomized with 30 completing the 22-week follow-up, which significantly reduced power to detect effects. This is important to note given that all findings were in the expected direction. Second, TAU, received by both treatment groups, could have included a range of psychotherapies and/or medication. Unrestricted TAU may have made it difficult to detect meaningful effects of the new intervention. Moreover, given the small sample size, differences in TAU across groups could not be controlled.

Although different trials were used to evaluate the efficacy of this intervention type between the 2015 review and current review, CBT—Individual remains classified as Level 4: Experimental for reducing SA and SI in youth.

One additional trial did not meet inclusion criteria for our review based on the small sample size, but is worth mentioning given that it also examined a CBT—Individual treatment. In a small (N=32; 12–15 per group) RCT with depressed youth in outpatient care, mood regulation focused CBT (MR-CBT) was compared to TAU (standard practice in psychiatry; Högberg, &Hällström, 2018). MR-CBT is a treatment based on memory reconsolidation that aims to increase positive and decrease negative emotions related to autobiographical memories. The MR-CBT group reported significantly fewer suicide events (active suicide ideation with any method and/or suicide attempts) over the course of treatment but this change was not significantly different than the TAU group. This trial was underpowered and therefore further testing of this intervention is needed before rating its efficacy.

CBT—Individual + Family.

The evaluation of this intervention type and mode has not changed since the prior review (of note, it was previously labeled “CBT-Individual + CBT-Family + Parent Training” due to the addition of parent training compared to earlier iterations of the treatment package; Donaldson, Spirito, & Esposito-Smythers, 2005; Esposito-Smythers, Spirito, Uth, & LaChance, 2006). In a small (N=40) RCT, Esposito-Smythers et al. (2011) compared integrated CBT (I-CBT), combining individual CBT (e.g., refusal skills), family CBT (e.g., communication), and parent training (e.g., emotion regulation), to enhanced TAU (E-TAU; community TAU enhanced with a diagnostic report shared with the TAU provider, medication management, and additional clinical referrals as needed). Compared to E-TAU, significantly fewer youth receiving I-CBT reported SAs over the 18-month follow-up period (ITT analyses). Both treatment groups reported decreased SI over the course of treatment, but reductions were not significantly greater in the I-CBT group. Therefore, CBT–Individual + Family remains classified as Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing SAs in youth and Level 4: Experimental for reducing SI in youth.

Two other trials did not meet inclusion criteria for our review due to sample sizes, but are worth discussing as potentially promising CBT interventions for adolescents and families. The first trial tested Parent-Adolescent CBT (PA-CBT), which provides concurrent CBT for depressed adolescents and their parents (Spirito et al., 2015). In a small trial (N=24 adolescent-parent dyads), PA-CBT was compared to adolescent only CBT. PA-CBT was feasible and acceptable for most families with the largest treatment effect on parents’ depression. Adolescents in both groups exhibited significant reductions in SI over the course of treatment, but effects were not significantly greater for the PA-CBT group. Replication in a larger trial is needed to test the efficacy of this new intervention for suicidal youth and families.

A second, small (N=30, 15 per group) clinical trial compared CBT for suicide prevention (CBT-SP; Stanley et al., 2009) to a waitlist control among adolescents who had attempted suicide in the past three months (Alavi et al., 2013). CBT-SP is a 12-session treatment package delivered in three phases: (1) psychoeducation, chain analysis, safety planning, reasons for living, and case conceptualization, (2) a menu of optional CBT modules to enhance individual skills training (e.g., behavioral activation, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving) and family skills (e.g., family communication, family emotion regulation, and family problem solving), and (3) relapse prevention. From pre- to post-treatment, youth receiving CBT-SP reported significant reductions in SI compared to the waitlist control group. Although promising, replication of this intervention in a larger trial with an active control group is needed.

Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A)

IPT-A—Individual.

There have been no changes in the status of IPT-A since the prior review. Only one trial has examined individual IPT-A for adolescents (IPT-A) at risk for SITBs (Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang, & Yen, 2009). IPT-A focuses on enhancing interpersonal functioning and resolving interpersonal problems with an emphasis on youth-specific difficulties (e.g., peer pressure; Mufson, Moreau, Weissman, & Klerman, 1993). Tang et al. (2009) found that school-based IPT-A significantly reduced SI over the course of treatment compared to TAU (i.e., psychoeducation and supportive counseling). Based on this trial, IPT-A remains classified as Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing SI in youth.

Psychodynamic therapy

Psychodynamic therapy—Individual + Family.

The efficacy rating of this mode of psychodynamic therapy has not changed since the prior review. Only one trial has examined a psychodynamic intervention including individual and family components for reducing DSH in adolescents – Mentalization-Based Treatment for Adolescents (MBT-A: Rossouw & Fonagy, 2012). MBT-A aims to reduce DSH by improving mentalization, or the ability to understand the connection between behaviors, thoughts, and feeling among themselves and others. Compared to community-based TAU, MBT-A significantly reduced DSH in adolescents and did so at a significantly faster rate during treatment (ITT analyses). Given that Psychodynamic therapy—Individual + Family was tested in an RCT and found to be superior to an active treatment control, it remains classified as Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing DSH in youth.

Psychodynamic therapy—Family-based.

Two RCTs conducted by the same research group have examined the same Family-based psychodynamic therapy (previously called “FBT-Attachment”), “brand name” Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT: Diamond, Reis, Diamond, Siqueland, & Isaacs, 2002). ABFT aims to reduce SITBs by enhancing parent-adolescent relationships through process-oriented, cognitive-behavioral, and emotion-focused techniques. One RCT (Diamond et al., 2010) was included in the prior review and the second RCT is new to this review (Diamond et al., 2018). In the first RCT, Diamond et al. (2010) found that youth receiving ABFT reported significantly greater reductions in SI compared to enhanced TAU (referrals and clinical monitoring) over the course of treatment and effects were maintained 12 weeks post-treatment (ITT analyses). SA rates were too small to examine between treatment groups.

However, findings from a second, larger RCT compared ABFT to a more active comparison treatment were not as promising. In this second RCT, Diamond et al. (2018) compared ABFT to family-enhanced nondirective supportive therapy (FE-NST). FE-NST focuses on developing a supportive adolescent-therapist relationship and parent education. The intervention includes individual sessions with the adolescent, individual sessions with the parent, and one joint parent-youth session. Compared to the enhanced TAU control included in the initial trial (Diamond et al., 2010), FE-NST was a more conservative comparison intervention because it is manualized and matches ABFT in treatment dose while targeting different content. Over the course of treatment, both groups reported significant reductions in SI, but this decrease was not significantly greater in the ABFT group (ITT analyses). There were no significant differences between groups in SA rates.

This intervention was previously evaluated as Level 2: Probably efficacious for SI in youth based on the first RCT (Diamond et al., 2010). However, taken together with the null findings from the second RCT (Diamond et al., 2018), Psychodynamic therapy—Family-based is now evaluated as Level 4: Experimental for reducing SA and SI in youth.

Family therapy

Two trials, one reviewed previously (Harrington et al., 1998) and one new to this review (Cottrell et al., 2018), tested a family-focused treatment program that targeted family functioning as a means to decrease SITBs. Therefore, we combined these two trials into one treatment family—Family Therapy. However, specific differences between the intervention packages are also described.

Harrington et al. (1998), reviewed previously, compared a brief (5-session), home-based family intervention (Kerfoot, Harrington, & Dyer, 1995) plus usual outpatient care to outpatient care alone in a large (N=162) RCT with adolescents who recently engaged in deliberate self-poisoning. The intervention focused on family problem-solving, family communication, and addressing family problems that contributed to adolescents’ DSH. The experimental intervention was not superior to TAU for reducing SI (ITT analyses).

The second RCT is new to this review. Among adolescents referred to mental health services for repetitive self-harm, Cottrell et al. (2018) compared Family Therapy (FT) for self-harm to community TAU in the largest (N=832) multi-site RCT included in this review (Self-Harm Intervention: Family Therapy: SHIFT; Wright-Hughes et al., 2015). To reduce adolescents’ DSH, FT included approximately eight 75-minute sessions over six months to enhance family strengths and resources (Wright-Hughes et al., 2015). FT was not significantly more effective than TAU for reducing DSH in youth during treatment or over the 18-month follow-up (ITT analyses). However, FT did reduce SI significantly more than TAU at the 12-month follow-up, but treatment effects did not hold at the 18-month follow-up. Limitations of this trial that may have contributed to the null findings include the relatively low dose of treatment (on average, treatment was monthly for six months), unrestricted TAU that could have included CBT or general (non-manualized) family therapy, and substantial attrition (50–60%) over the long (18-month) follow-up.

Taken together, the efficacy of Family Therapy for reducing SI is mixed across two studies and nonsignificant for DSH in one study (Cottrell et al., 2018). Therefore, the evaluation of Family Therapy is Level 4: Experimental for reducing DSH and SI in youth.

Multiple systems therapy

There have been no changes in the efficacy of Multiple Systems Therapy since the prior review (referred in the prior review as Family-based therapy—Ecological). Only one trial has examined multisystemic therapy (MST) for reducing SAs in youth (Huey et al., 2004). MST is an intensive home-based intervention to reduce problem behaviors among youth by targeting the multiple systems (e.g., peers, family, school, community) that contribute to these behaviors (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2009). Huey et al. (2004) found that adolescents receiving MST reported fewer SAs over the course of treatment compared to a hospitalization control. A range of limitations were noted in the 2015 review (e.g., inclusion criteria based on self- or other-directed violence risk, a significant portion of MST group was also hospitalized) that led to Multiple Systems Therapy remaining classified as Level 3: Possibly efficacious for reducing SAs in youth and Level 4: Experimental for reducing SI in youth.

Integrated family therapy

New to this review, Asarnow et al. (2017) tested a novel family-centered treatment informed by CBT, DBT, and family therapy approaches, as well as social-ecological theory (Asarnow, Berk, Hughes, & Anderson, 2015). Given that this treatment package integrated multiple approaches into a family-based intervention, it did not seem appropriate to combine it with DBT, CBT, or family therapy. Therefore, a new category was created for this intervention: Integrated Family Therapy.

In a small RCT (N=42), Asarnow et al. (2017) compared their novel treatment program, Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth (SAFETY; Asarnow, Berk, Hughes, & Anderson, 2015), to TAU enhanced with parent psychoeducation and telephone calls to increase motivation for follow-up care (E-TAU). Adolescents were recruited from mental health services across the continuum of care (emergency department, inpatient, partial hospitalization, or outpatient services) if they had attempted suicide in the past three months, or NSSI was identified as a primary problem, and they had engaged in repetitive DSH (3+ lifetime episodes). The SAFETY treatment program is a 12-week, family-centered intervention administered by two therapists—one for the adolescent and one for the parent/guardian. A variety of techniques are used to tailor the intervention for each family including a functional, or chain, analysis to identify antecedents or triggers of the index SA or DSH. In addition, a strong emphasis is placed on addressing practical barriers to care. The first session is conducted in the home and treatment for the family includes motivational enhancement and reducing barriers to care. The treatment program includes a range of skills and techniques to foster SAFE: (1) settings (e.g., means restriction), (2) people (e.g., enhancing social support), (3) activities (e.g., behavioral activation), (4) thoughts (e.g., cognitive restructuring), and (5) stress reactions (e.g., distress tolerance; Asarnow et al., 2015).

Results indicated that the SAFETY treatment program significantly reduced risk for SA compared to E-TAU (ITT analyses). Specifically, there was significantly longer time to SA for adolescents in the SAFETY group as compared to E-TAU over the 3-month follow-up period. Moreover, there were no SAs among adolescents in the SAFETY group over the 3-month intervention period. However, the intervention effect (i.e., between-group difference) weakened after the treatment ended. In addition, the SAFETY intervention did not have a significant effect on NSSI, which was frequent across both treatment groups.

Although promising, some limitations of this first RCT testing SAFETY are worth noting. First, the sample size was small (ns=20–22 per group), and just met the cutoff for inclusion in this review. Further replication in larger trials is needed. In addition, replication by an independent research group is needed to evaluate the intervention as Level 1: Well-established for reducing SA in youth. Second, like many trials in this review, the E-TAU control was not an ideal comparison intervention due to high attrition (45% of youth post-treatment assessments were unavailable). Although this tempers conclusions about the superiority of SAFETY to active intervention, the main analyses did take censoring into account and were significant even with the most conservative assumption about adolescents with unavailable data.

Based on the promising findings from this single RCT, Integrated Family Therapy is evaluated as Level 2: Probably efficacious for reducing SA in youth and Level 4: Experimental for reducing NSSI in youth.

Brief family-based therapy