Abstract

Black race and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with lower rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) to interferon-based treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus infection, whereas Asian race was associated with higher SVR rates compared to white patients. We aimed to describe the association between race/ethnicity and effectiveness of new direct-acting antiviral regimens in the Veterans Affairs health care system nationally. We identified 21,095 hepatitis C virus-infected patients (11,029 [52%] white, 6,171 [29%] black, 1,187 [6%] Hispanic, 348 [2%] Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Alaska Native, and 2,360 [11%] declined/missing race or ethnicity) who initiated antiviral treatment with regimens containing sofosbuvir, simeprevir + sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir during the 18-month period from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Overall SVR rates were 89.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] 89.2–90.4) in white, 89.8% (95% CI 89.0–90.6) in black, 86.0% (95% CI 83.7–88.0) in Hispanic, and 90.7% (95% CI 87.0–93.5) in Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Alaska Native patients. However, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, black (adjusted odds ratio = 0.77, P< 0.001) and Hispanic (adjusted odds ratio = 0.76, P = 0.007) patients were less likely to achieve SVR than white patients, a difference that was not explained by early treatment discontinuations. Among genotype 1–infected patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir monotherapy, black patients had significantly lower SVR than white patients when treated for 8 weeks but not when treated for 12 weeks. Conclusion: Direct-acting antivirals produce high SVR rates in white, black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Alaska Native patients; but after adjusting for baseline characteristics, black race and Hispanic ethnicity remain independent predictors of treatment failure. Short 8-week ledipasvir/sofosbuvir monotherapy regimens should perhaps be avoided in black patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. (HEPATOLOGY 2017;65:426–438).

New direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have substantially changed the hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment landscape. Clinical trials report rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) in excess of 90% for ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF), paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir and dasabuvir (PrOD), and simeprevir plus SOF (SMV+SOF) regimens.(1–11) Given their high efficacy, short treatment duration, and improved side effect profile, DAAs have the potential to narrow the SVR gap between patient groups who have historically responded poorly to treatment and those who have better response.

Different racial and ethnic groups in the United States are known to have different responses to traditional, interferon-based HCV regimens. Interferon-based regimens, including those using the protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir, resulted in much lower rates of SVR among black(12–16) and Hispanic(17–19) patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients. Asian ethnicity, on the other hand, has generally been associated with higher SVRs compared to other races and ethnicities.(18)

It is not yet clear whether the effectiveness of DAAs varies between racial and ethnic groups in the United States. A recent analysis of pooled data from the ION-1, ION-2, and ION-3 clinical trials, which evaluated the efficacy of LDV/SOF with or without ribavirin (RIBA) for treatment of genotype 1 HCV infection, found that black patients had similar rates of SVR12 (95%) compared to nonblack patients (97%).(20) However, these data are limited by inclusion of only a small number of black patients (n = 308) and furthermore do not capture real-world outcomes. Disparities in difficult-to-treat populations are often accentuated in real-world practice compared to clinical trials.(21,22)

In this study we aimed to compare the real-world effectiveness of SOF, SMV+SOF, LDV/SOF, and PrOD-based regimens among different racial and ethnic groups treated in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system nationally. The VA provides an optimal setting to study race/ethnicity-related disparities in DAA effectiveness due to the high prevalence of HCV among veterans, the large population of racial and ethnic minorities, the nationwide distribution of the VA system, and the lack of confounding factors related to health insurance coverage.

Patients and Methods

DATA SOURCE: THE VA CORPORATE DATA WAREHOUSE

We extracted data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, a national repository of data obtained from the VA electronic medical records.(23) Data extracted included all pharmacy prescriptions, demographics, inpatient and outpatient visits, problem lists, procedures, vital signs, diagnostic tests, and laboratory tests. Data were extended back to October 1, 1999, to determine whether patients had received prior HCV treatments, and extended forward to April 15, 2016, to allow for completion of treatments and ascertainment of SVR.

STUDY POPULATION AND ANTIVIRAL REGIMENS

Out of 24,089 HCV antiviral regimens initiated in the VA nationally from January 1, 2014 (the month after SOF was approved by the Food and Drug Administration), to June 30, 2015, and completed before October 1, 2015, we excluded 2,585 regimens that were no longer used or recommended by the time we analyzed our data (e.g., SOF + pegylated interferon [PEG]/RIBA and SOF+RIBA for genotype 1–infected patients and all PEG/RIBA regimens). We additionally excluded 409 “duplicate” regimens, in which the same patient appeared to have received one very short “regimen” (e.g., 14-day regimen) followed at a later date by a longer course of the same regimen (these short, “duplicate” regimens were most likely erroneous or postponed prescriptions), leaving 21,095 patients in the current analysis, all of whom were treated with the direct antiviral agents SOF, SMV+SOF, LDV/SOF, or PrOD.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

We ascertained race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Alaska Native [Asian/PI/AI/AN]), age, gender, HCV genotype, baseline HCV viral load, and all of the baseline laboratory tests shown in Table 1 using the value of the test closest to the date treatment was initiated within the preceding 6 months. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score, a marker of hepatic fibrosis, was calculated using the formula FIB-4 = (age × aspartate aminotransferase)/(platelets × alanine aminotransferase½).(24)

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated With DAAs by Race/Ethnicity

| All Patients (n = 21,095), n |

White (n = 11,029) (%) |

Black (n = 6,171) (%) |

Hispanic (n = 1,187) (%) |

Asian/PI/AI/AN (n = 348) (%) |

Declined/ Missing (n = 2,360) (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 20,407 | 97.0 | 96.5 | 98.3 | 97.4 | 96.2 |

| Age category (years) | 21,030 | |||||

| <55 | 2,235 | 12.9 | 7.0 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 9.1 |

| 55–<60 | 5,399 | 26.1 | 25.9 | 28.6 | 28.5 | 21.0 |

| 60–<65 | 7,681 | 35.1 | 38.5 | 36.0 | 34.2 | 38.7 |

| 65–<70 | 4,907 | 22.5 | 24.3 | 19.8 | 21.8 | 27.0 |

| 70–<75 | 607 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| ≥75 | 201 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Treatment-experienced | 5,109 | 23.5 | 23.6 | 28.4 | 21.3 | 27.5 |

| Genotype (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 17,582 | 77.2 | 95.5 | 80.6 | 80.5 | 82.1 |

| 2 | 2,131 | 13.6 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 12.0 |

| 3 | 1,247 | 8.6 | 0.7 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 5.7 |

| 4 | 135 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Regimen (%) | ||||||

| LDV/SOF | 8,222 | 34.7 | 48.1 | 29.8 | 33.3 | 40.6 |

| LDV/SOF+RIBA | 3,105 | 15.3 | 12.0 | 18.2 | 16.4 | 16.9 |

| PrOD | 777 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 3.8 |

| PrOD+RIBA | 2,397 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 10.8 | 13.5 | 12.5 |

| SOF+RIBA | 2,846 | 18.6 | 3.5 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 14.7 |

| PEG+SOF+RIBA | 140 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| SMV+SOF | 3,021 | 14.2 | 15.6 | 20.0 | 16.4 | 8.6 |

| SMV+SOF+RIBA | 587 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| HCV RNA viral load >6 million, IU/mL (%) | 6,857 | 32.4 | 34.7 | 33.7 | 32.2 | 26.8 |

| HIV coinfection | 826 | 1.8 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 3.9 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 7,257 | 35.2 | 30.7 | 48.7 | 35.1 | 33.2 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (%) | 2,093 | 11.5 | 5.6 | 17.9 | 11.5 | 9.7 |

| HCC (%) | 676 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 2.8 |

| Liver transplantation (%) | 615 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| Diabetes (%) | 6,452 | 25.8 | 38.2 | 34.5 | 30.5 | 31.2 |

| Alcohol use disorder (%) | 9,318 | 42.6 | 47.6 | 43.2 | 38.5 | 44.1 |

| Substance use disorder (%) | 7,712 | 32.0 | 45.1 | 35.6 | 33.6 | 36.7 |

| Depression (%) | 10,061 | 46.8 | 48.4 | 51.1 | 45.1 | 48.6 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (%) | 5,731 | 24.2 | 29.0 | 28.5 | 29.9 | 35.5 |

| Anxiety/panic (%) | 7,225 | 36.3 | 30.3 | 35.7 | 32.2 | 34.8 |

| Schizophrenia (%) | 1,153 | 3.6 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 9.1 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||

| Anemia* (%) | 3,419 | 13.7 | 21.1 | 17.2 | 14.1 | 14.9 |

| Platelet count < 100 k/μL (%) | 3,523 | 19.4 | 10.1 | 25.4 | 19.3 | 16.5 |

| Creatinine >1.1 mg/dL (%) | 4,222 | 15.2 | 31.6 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 18.9 |

| Bilirubin >1.1 g/dL (%) | 3,221 | 17.4 | 11.6 | 21.6 | 13.2 | 14.2 |

| Albumin <3.6 g/dL (%) | 4,936 | 22.2 | 26.0 | 25.1 | 20.4 | 22.1 |

| International normalized | 4,905 | 25.2 | 22.1 | 30.4 | 20.5 | 23.4 |

| ratio >1.1 (%) | ||||||

| FIB-4† score > 3.25 (%) | 8,022 | 42.4 | 33.0 | 49.5 | 43.3 | 39.5 |

Anemia is defined as a hemoglobin concentration <13 g/dL in men or <12 g/dL in women.

FIB-4 score(24) = (age × aspartate aminotransferase)/(platelets × alanine aminotransferase½).

Cirrhosis was defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes for “cirrhosis with alcoholism” (571.2) or “cirrhosis no mention of alcohol” (571.5). Decompensated cirrhosis was defined by “esophageal varices with or without bleeding” (456.0–456.21), ascites (789.5), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (567.23), hepatic encephalopathy (572.2), or hepatorenal syndrome (572.4). The presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; 155.0), the presence of diabetes (250.0–250.92 or prescription of diabetes medications), and liver transplantation status (996.82, V42.7) were also determined. Patients with cirrhosis or HCC who underwent liver transplantation were excluded from the cirrhosis and HCC categories. Additionally, the following comorbidities were ascertained using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes noted in parentheses: depression (311.0–311.9), posttraumatic stress disorder (309.81), anxiety or panic (300.0–300.9), schizophrenia (295.0–295.9), alcohol use disorders (defined by “alcohol abuse” 305.00–305.03, “dependence” 303.90–303.93, or “withdrawal” 291.81), and substance use disorders (defined by “substance abuse” 305.2–305.9, “dependence” 304.0–304.9, or “drug withdrawal” 292.0). The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes used to ascertain cirrhosis, HCC(25–30) and other comorbidities(27,31–35) have been widely used and validated in national VA data. These conditions were noted only if recorded at least twice prior to treatment initiation.

SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

SVR was defined by a viral load below the limit of quantification performed >12 weeks after the end of treatment.(36) If no viral load test was available >12 weeks after the end of treatment, then SVR was defined by a viral load performed 4–12 weeks after the end of treatment, which accounted for an additional 1,126 SVR determinations. This was justified because SVR ascertained based on viral load 4 weeks after the end of treatment was shown to have 98% concordance (positive predictive value 98%, negative predictive value 100%) with SVR ascertained based on viral load >12 weeks after the end of treatment in SOF-treated patients.(36) Duration of therapy and end of treatment were defined by the total duration of DAA prescriptions filled.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SVR rates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined by race/ethnicity group and by subgroups defined by genotype, treatment regimen, prior treatment, cirrhosis, and other clinically relevant characteristics. We used multivariable logistic regression to determine whether race/ethnicity was a predictor of SVR after adjusting for the following baseline characteristics selected a priori because they are known or suspected to be associated with both race/ethnicity and SVR: age, genotype/subgenotype, regimen, gender, HCV viral load, platelet count, serum bilirubin level, serum albumin level, alcohol use disorder, diabetes, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, and prior treatment. In exploratory models we additionally adjusted for treatment duration to investigate whether early treatment discontinuation could account for any differences between racial/ethnic groups in SVR.

We included interaction terms between race/ethnicity and genotype, cirrhosis, treatment experience, liver transplantation, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection in the multivariable models to determine whether the association between race/ethnicity and SVR was significantly different among subgroups defined by these characteristics.

In prior VA studies, as well as other real-world studies, viral load testing necessary to ascertain SVR was missing in a significant proportion of patients. To estimate the impact that missing SVR data might have, we used multiple imputation to impute missing SVR values in secondary analyses. Missing SVR values were imputed using a logistic regression model that included the baseline patient characteristics shown in Table 1 (24 characteristics including regimen, genotype, treatment-experienced or treatment-naive, cirrhosis, HCC) and importantly included the duration of treatment. The number of imputations was varied from 10 to 200, resulting in estimates that were identical up to four significant digits. The model was determined to be stable, and 20 imputations were used. Data were assumed to be missing at random. This assumption was found to be reasonable using the observed data.

Analyses were performed using Stata/MP version 14.1 (64-bit) (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

DIFFERENCES IN BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS BY RACIAL/ETHNIC GROUPS

Of the 21,095 patients included in the study, 11,029 (52%) were white, 6,171 (29%) were black, 1,187 (6%) were Hispanic, and 348 (2%) were Asian/PI/AI/AN (Table 1). There were an additional 2,360 (11%) patients with declined or missing race/ethnicity designation. Among black patients, 95.5% had genotype 1 HCV compared to approximately 80% of white, Hispanic, and Asian/PI/AI/AN patients. A far smaller proportion of black patients had genotype 2 (3.0%) or genotype 3 (0.7%) HCV compared to other race/ethnicity groups. A higher proportion of Hispanic patients had received prior HCV treatment (28.4%) compared to other groups (23.5% of whites, 23.6% of blacks, and 21.3% of Asian/PI/AI/AN patients). Hispanics also appeared to have more severe liver disease, as shown by a substantially higher prevalence of cirrhosis (48.7%) and decompensated cirrhosis (17.9%), high FIB-4 scores (49.5%), and abnormal bilirubin, international normalized ratio, and platelet counts. In contrast, black patients were least likely to have cirrhosis (30.7%), decompensated cirrhosis (5.6%), and elevated FIB-4 scores (33.0%). There was a higher prevalence of HIV coinfection in black and Hispanic patients (7.5% and 5.8%, respectively) as well as diabetes (38.2% and 34.5%, respectively) than in white patients (1.8% with HIV coinfection and 25.8% with diabetes) or Asian/PI/AI/AN patients (2.0% with HIV coinfection and 30.5% with diabetes).

SVR BY RACE/ETHNICITY, OVERALL AND IN SUBGROUPS DEFINED BY GENOTYPE AND TREATMENT REGIMEN

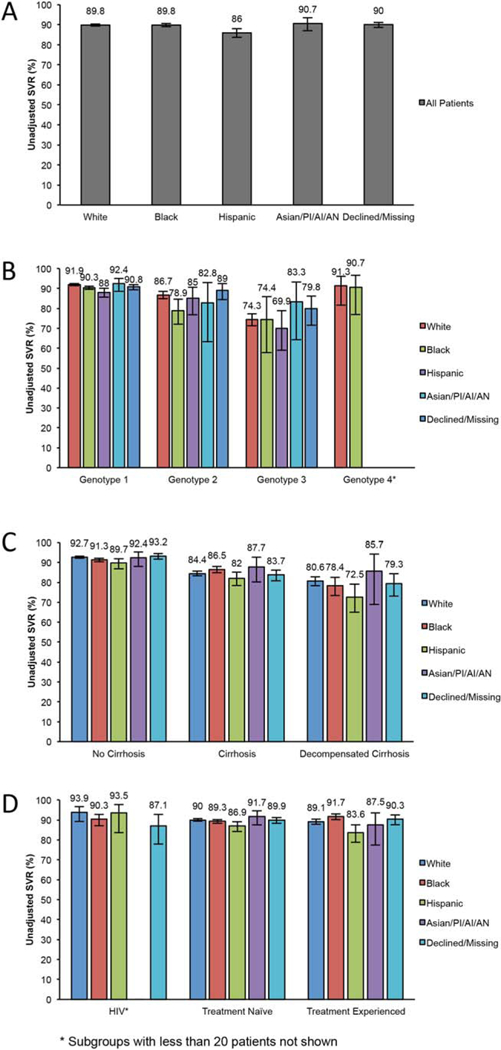

Of the 21,095 patients in this study, SVR data were available in 19,286 (91.4%). Overall SVR rates were similar in white (89.8), black (89.8%), and Asian/PI/AI/AN (90.7%) patients and slightly lower in Hispanic patients (86.0%) (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

SVR Rates (and 95% Cl) by Race/Ethnicity Among Clinically Relevant Subgroups

| All Patients (n = 19,286) |

White (n = 10,180) |

Black (n = 5,615) |

Hispanic (n = 1,013) |

Asian/PI/AI/AN (n = 324) |

Declined/ Missing (n = 2,154) (%, 95% Cl) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 89.6 (89.2–90.1) | 89.8 (89.2–90.4) | 89.8 (89.0–90.6) | 86.0 (83.7–88.0) | 90.7 (87.0–93.5) | 90.0 (88.6–91.2) | ||

| Genotype/regimen | ||||||||

| 1 | 91.1 (90.6–91.5) | 91.9 (91.3–92.5) | 90.3 (89.5–91.1) | 88.0 (85.6–90.1) | 92.4 (88.5–95.1) | 90.8 (89.3–92.0) | ||

| SMV + SOF | 84.4 (83.1–85.7) | 86.0 (84.2–87.7) | 82.1 (79.4–84.5) | 81.3 (75.5–86.0) | 90.9 (79.5–96.3) | 84.6 (78.6–89.1) | ||

| SMV+SOF+RIBA | 87.0 (84.0–89.6) | 88.1 (84.0–91.3) | 86.1 (79.8–90.6) | 78.1 (59.6–89.7) | N/A | 86.4 (72.1–93.9) | ||

| LDV/SOF | 92.8 (92.2–93.4) | 94.1 (93.3–94.9) | 92.0 (90.9–93.0) | 89.7 (85.5–92.7) | 91.5 (84.3–95.6) | 91.3 (89.2–93.0) | ||

| LDV/SOF+RIBA | 92.0 (90.9–93.0) | 92.4 (90.8–93.7) | 92.1 (89.8–94.0) | 91.1 (85.7–94.6) | 95.6 (83.1–98.9) | 90.5 (86.9–93.3) | ||

| PrOD | 94.9 (93.0–96.3) | 96.1 (93.1–97.8) | 93.4 (90.1–95.7) | N/A | N/A | 95.4 (88.2–98.3) | ||

| PrOD+RIBA | 92.5 (91.3–93.5) | 92.5 (90.7–93.9) | 92.3 (90.0–94.1) | 93.5 (86.9–96.9) | 90.7 (76.9–96.6) | 92.9 (89.1–95.4) | ||

| 2 | 86.2 (84.5–87.7) | 86.7 (84.8–88.4) | 78.9 (72.0–84.5) | 85.0 (76.8–90.7) | 82.8 (63.3–93.0) | 89.0 (84.4–92.4) | ||

| SOF+RIBA | ||||||||

| 3 | 74.8 (72.2–77.3) | 74.3 (71.3–77.2) | 74.4 (57.8–86.0) | 69.9 (59.0–78.9) | 83.3 (64.3–93.3) | 79.8 (71.5–86.2) | ||

| LDV/SOF+RIBA | 77.9 (73.2–82.0) | 76.8 (71.1–81.6) | N/A | 67.9 (47.5–83.1) | N/A | 84.4 (70.1–92.6) | ||

| SOF+PEG+RIBA | 87.0 (80.0–91.8) | 87.5 (78.6–93.0) | 87.5 (31.9–99.1) | 91.7 (49.9–99.2) | 100 | 78.9 (52.7–92.7) | ||

| SOF+RIBA | 70.6 (66.9–74.1) | 70.7 (66.5–74.6) | 62.5 (40.6–80.2) | 65.1 (49.3–78.2) | 75.0 (45.7–91.4) | 76.4 (63.0–86.0) | ||

| 4 | 89.6 (82.8–93.9) | 91.3 (81.6–96.1) | 90.7 (76.9–96.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| LDV/SOF or PrOD ± RIBA | ||||||||

| No cirrhosis | 92.2 (91.7–92.7) | 92.7 (92.1–93.3) | 91.3 (90.4–92.2) | 89.7 (86.8–92.0) | 92.4 (87.9–95.3) | 93.2 (91.7–94.4) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 84.8 (83.9–85.6) | 84.4 (83.2–85.6) | 86.5 (84.8–88.0) | 82.0 (78.4–85.2) | 87.7 (80.2–92.6) | 83.7 (80.8–86.2) | ||

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 79.5 (77.6–81.3) | 80.6 (78.2–82.7) | 78.4 (73.4–82.6) | 72.5 (64.9–79.1) | 85.7 (68.9–94.2) | 79.3 (73.1–84.4) | ||

| HIV | 91.1 (88.9–92.9) | 93.9 (89.2–96.6) | 90.3 (87.1–92.7) | 93.5 (83.6–97.6) | N/A | 87.1 (77.9–92.8) | ||

| Liver transplantation | 93.8 (91.5–95.5) | 95.7 (93.0–97.3) | 89.1 (80.8–94.1) | 86.0 (71.5–93.8) | N/A | 93.5 (83.6–97.6) | ||

| Treatment-naive | 89.6 (89.1–90.1) | 90.0 (89.3–90.7) | 89.3 (88.3–90.2) | 86.9 (84.2–89.1) | 91.7 (87.5–94.5) | 89.9 (88.2–91.3) | ||

| Treatment-experienced | 89.7 (88.7–90.5) | 89.1 (87.8–90.3) | 91.7 (90.1–93.1) | 83.6 (78.8–87.5) | 87.5 (77.4–93.5) | 90.3 (87.6–92.4) | ||

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable due to fewer than 15 patients in this subgroup.

FIG. 1.

SVR rates by racial/ethnic group. (A) Overall SVR rates by race/ethnic group. (B) SVR by race/ethnic group and genotype. (C) SVR by race/ethnic group and presence of cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis. (D) SVR by race/ethnic group and HIV status or receipt of prior treatment.

Among genotype 1–infected patients, the lowest SVR rate was observed in Hispanic (88.0%) followed by black (90.3%), white (91.9%), and Asian/PI/AI/AN (92.4%) patients. SMV+SOF regimens with or without RIBA resulted in lower SVR rates than LDV/SOF or PrOD-based regimens in all racial/ethnic groups (Table 2). However, it is important to emphasize that our analyses were not designed to compare regimens with respect to SVR (i.e., multivariate or propensity score adjusted results of the associations between regimen and SVR are not reported as this was not the aim of the study).

Among genotype 2–infected patients, who were all treated with SOF+RIBA, black patients had a lower SVR (78.9%) than white (86.7%), Hispanic (85.0%), and Asian/PI/AI/AN (82.8%) patients.

Hispanic patients with genotype 3 disease had a lower rate of SVR (69.9%) than white (74.3%), black (74.4%), or Asian/PI/AI/AN (83.3%) patients (Table 2), although there were far fewer black (n = 39), Hispanic (n = 28), or Asian/PI/AI/AN (n = 30) patients with genotype 3 HCV than white patients (n = 834), resulting in wide confidence intervals for SVRs.

The 69 white and 43 black patients with genotype 4 who were treated with LDV/SOF or PrOD with or without RIBA had very similar SVRs of 91.3% (95% CI 81.6–96.1) and 90.7% (95% CI 76.9–96.6), respectively; only 7 Hispanic and 3 Asian/PI/AI/AN patients had genotype 4 HCV.

SVR BY RACE/ETHNICITY IN SUBGROUPS DEFINED BY CIRRHOSIS, HIV COINFECTION, LIVER TRANSPLANTATION, OR PRIOR ANTIVIRAL THERAPY

We investigated whether differences in SVR by racial/ethnic group were accentuated in certain patient subgroups that were traditionally considered “difficult to treat” (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In all races/ethnicities, those without cirrhosis had higher SVRs than those with cirrhosis, who in turn had higher SVRs than those with decompensated cirrhosis. Hispanic patients had similar SVR as other race/ethnicity groups among those without cirrhosis (89.7%, 95% CI 86.8–92.0) but lower SVR than other groups among those with cirrhosis (82.0%, 95% CI 78.4–85.2) and substantially lower SVRs among those with decompensated cirrhosis (72.5%, 95% CI 64.9–79.1) (Table 2).

Among those with HIV coinfection, black patients had slightly lower SVR (90.3%, 95% CI 87.1–92.7) than white (93.9%, 95% CI 89.2–96.6) or Hispanic (93.5%, 95% CI 83.6–97.6) patients, but all groups attained remarkable SVR rates of >90% (Table 2). Among those who had received a liver transplant, Hispanic (86.0%, 95% CI 71.5–93.8) and black (89.1%, 95% CI 80.8–94.1) patients had lower SVRs compared to white patients (93.9%, 95% CI 93.0–97.3) (there were only 10 Asian/PI/AI/AN patients with prior liver transplant, all of whom achieved SVR).

Among both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, Hispanic patients had lower SVR than other racial/ethnic groups.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN RACE/ETHNICITY AND SVR IN MULTIVARIABLE MODELS

After adjustment for baseline characteristics in multivariable logistic regression models, black (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.77, 95% CI 0.69–0.87) and Hispanic (AOR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.62–0.93) patients had significantly lower likelihood of SVR compared to white patients (Table 3). Although the unadjusted odds ratio for SVR comparing black to white patients was essentially equal to 1 and nonsignificant (1.01, P= 0.9), important negative predictors of SVR, such as cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and, most importantly, HCV genotype 2 or 3 infection, were less common in black patients than in other racial groups. Therefore, adjusting for these characteristics reduced the AOR for black race. When additionally adjusting for duration of antiviral treatment, the AOR for black race was attenuated only very slightly to 0.80 (95% CI 0.70–0.91) and the AOR for Hispanic ethnicity to 0.82 (95% CI 0.66–0.99), suggesting that differences in early discontinuation of treatment did not account for the association between race/ethnicity and lower SVR.

TABLE 3.

Association Between Race/Ethnicity and SVR in Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Presented Overall and by Genotype*

| All Patieints |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Odds Ratio |

P | AOR† | P | |

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 1.01 | 0.9 | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.70 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.007 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 1.11 | 0.6 | 1.09 | 0.7 |

| Declined/missing | 1.02 | 0.8 | 0.89 | 0.2 |

| Genotype 1 | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 0.82 | 0.001 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 0.006 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 1.07 | 0.8 | 1.11 | 0.7 |

| Declined/missing | 0.86 | 0.1 | 0.77 | 0.007 |

| Genotype 2 | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 0.57 | 0.007 | 0.49 | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.87 | 0.6 | 1.14 | 0.7 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 0.74 | 0.5 | 0.67 | 0.4 |

| Declined/missing | 1.24 | 0.3 | 1.42 | 0.1 |

| Genotype 3 | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 1.00 | 0.998 | 0.76 | 0.5 |

| Hispanic | 0.80 | 0.4 | 0.80 | 0.4 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 1.73 | 0.3 | 1.77 | 0.3 |

| Declined/missing | 1.37 | 0.2 | 1.31 | 0.3 |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 1.18 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.1 |

| Hispanic | 0.84 | 0.2 | 0.83 | 0.2 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 1.31 | 0.3 | 1.27 | 0.4 |

| Declined/missing | 0.95 | 0.6 | 0.78 | 0.04 |

| Treatment-experienced | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 1.35 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.3 |

| Hispanic | 0.62 | 0.007 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 0.86 | 0.7 | 0.95 | 0.9 |

| Declined/missing | 1.14 | 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.8 |

| HIV coinfection | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 0.61 | 0.2 | 0.55 | 0.3 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.9 | 1.07 | 0.3 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Declined/missing | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.1 |

Genotype 4–infected patients were not modeled separately as there were too few for robust multivariable models.

Adjusted by multivariable logistic regression modeling including race/ethnicity, age, genotype/subgenotype, regimen, gender, HCV viral load, platelet count, serum bilirubin level, serum albumin level, alcohol use disorder, diabetes, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, and prior treatment.

Among the patient subgroups shown in Table 3, black race was also significantly associated with lower likelihood of SVR in patients with genotype 1 or 2 HCV infection, while Hispanic ethnicity was significantly associated with lower likelihood of SVR in patients with genotype 1 HCV and those with prior treatment in multivariable models. Among HIV coinfected patients, blacks were less likely to achieve SVR than whites (AOR = 0.55), but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.3) in this relatively small subgroup. Overall, there was no subgroup in which the association between race/ethnicity and SVR was especially striking and formal tests of interaction were not significant for the interaction between race/ethnicity and genotype, cirrhosis, treatment experience, liver transplantation, or HIV coinfection.

EARLY TREATMENT DISCONTINUATION BY RACIAL/ETHNIC GROUPS

Among all patients who initiated treatment (n = 21,095), early discontinuation of treatment in <8 weeks was slightly more common in black (7.3%), Hispanic (7.9%), and Asian/PI/AI/AN (7.2%) patients than in white patients (5.8%) (Supporting Table S1). Mean duration of treatment was 88 days in white, 83 days in black, 89 days in Hispanic, and 87 days in Asian/PI/AI/AN patients. Among patients with available SVR data (n = 19,286), whose SVR results are shown in Tables 2 and 3, early treatment discontinuation in <8 weeks occurred in 4.3% of white, 5.4% of black, 6.3% of Hispanic, and 5.3% of Asian/PI/AI/AN patients.

LDV/SOF TREATMENT FOR 8 WEEKS IN GENOTYPE 1 PATIENTS AND ASSOCIATION WITH SVR

Food and Drug Administration guidelines and the LDV/SOF package insert suggest that 8 weeks of LDV/SOF monotherapy may be considered among genotype 1–infected patients who are treatment-naive, do not have cirrhosis, and do have a viral load <6 million IU/mL(37); however, this regimen is based on a post hoc analysis of the ION-3 study,(3) and it is unclear if it is widely used. Among 8,140 patients treated with LDV/SOF monotherapy, a similar proportion of white (28.7%), black (26.3%), and Asian/PI/AI/AN (27.6%) patients received 8 weeks of therapy compared to 20.3% of Hispanic patients. SVR rates were very similar in white, Hispanic, and Asian/PI/AI/AN patients who received 8 and 12 weeks of therapy; but they were slightly lower in blacks who received 8 weeks (92.0%, 95% CI 89.7–93.8) versus 12 weeks (95.2%, 95% CI 93.9–96.2) (Table 4). Also, when limiting to treatment-naive patients without cirrhosis with a viral load <6 million who received 8 weeks of LDV/SOF, SVR rates were lower in black (93.1%) than in white (96.4%) or Hispanic (96.4%) patients. In multivariate analysis, black race was associated with lower likelihood of SVR among patients who received 8 weeks of therapy (AOR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.36–0.88) but not among patients who receive 12 weeks of therapy (AOR = 0.89,95% CI 0.63–1.27) (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

SVR Rates Among Genotype 1 Patients Treated With 8 Versus 12 Weeks of LDV/SOF

| White SVR % (95% CI) |

Black SVR % (95% CI) |

Hispanic SVR % (95% CI) |

Asian/AI/PI/AN SVR % (95% CI) |

Declined SVR % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDV/SOF 8 weeks (n = 2,027) | 96.3 (94.9–97.3) | 92.0 (89.7–93.8) | 95.2 (85.6–98.5) | 93.1 (74.6–98.4) | 93.2 (89.1–95.8) |

| LDV/SOF 8 weeks* (n = 1,813) | 96.4 (95.0–97.5) | 93.1 (90.8–94.9) | 96.4 (86.3–99.1) | 92.0 (70.9–98.2) | 95.3 (91.4–97.4) |

| LDV/SOF 12 weeks (n = 3,832) | 95.5 (94.4–96.4) | 95.2 (93.9–96.2) | 93.8 (88.4–96.8) | 93.9 (82.0–98.1) | 93.4 (90.7–95.4) |

LDV/SOF 8-week treatment in treatment-naive, patients without cirrhosis with viral load <6 million IU/mL.

TABLE 5.

Association Between Race/Ethnicity and SVR Among Genotype 1 Patients Treated With 8 Versus 12 Weeks of LDV/SOF

| Genotype 1 LDV/SOF 8 weeks |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Odds Ratio |

P | AOR* | P | |

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 0.44 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 0.76 | 0.7 | 0.71 | 0.6 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 0.52 | 0.4 | 0.60 | 0.5 |

| Declined/missing | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.2 |

| Genotype 1 LDV/SOF | 12 weeks | |||

| White | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 0.93 | 0.7 | 0.89 | 0.5 |

| Hispanic | 0.71 | 0.4 | 0.79 | 0.5 |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 0.72 | 0.6 | 1.08 | 0.9 |

| Declined/missing | 0.67 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.1 |

Adjusted by multivariable logistic regression modeling including race/ethnicity, age, gender, HCV viral load, platelet count, serum bilirubin level, serum albumin level, alcohol use disorder, diabetes, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, and prior treatment.

IMPACT OF MISSING SVR DATA AND IMPUTATION FOR MISSING SVR

SVR data were missing in 8.6% (1809/21,095) of patients who received antiviral treatment, a proportion that was higher in black (9.0%) and Hispanic (14.7%) than in white (7.7%) or Asian/PI/AI/AN (6.9%) patients. It is possible that patients lacking data on SVR may be more likely to have been lost to follow-up or to discontinue therapy early or to have other predictors of poor response, which would mean that the observed SVR rates we report in Table 2 and Fig. 1 are overestimates. However, patients with versus without SVR data had very similar characteristics with respect to race/ethnicity, age, HCV genotype, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and most other baseline characteristics (Supporting Table S2). Patients with missing SVR did indeed have a higher rate of early treatment discontinuation <8 weeks compared to those with available SVR data (24.8% versus 4.4%); however, the majority completed their treatment, with mean duration of treatment for those without SVR data of 72.5 6 38 days and for those with SVR data of 87.6 6 32 days. Thus, the majority of patients without SVR data were not patients who dropped out of treatment but rather patients who simply had not yet had their follow-up HCV viral load performed in the relatively short follow-up period of our study.

When multiple imputation was used to derive missing SVR values using baseline characteristics as well as duration of treatment, the results that included imputed and observed SVR were only slightly lower than those with observed SVR (Table 6), again suggesting that it is unlikely that our results of observed SVR are biased substantially toward overestimation due to the missing SVR data.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of Observed SVR Among Patients With Available SVR Data and Combined Observed or Imputed SVR Among All Patients Who Initiated Antiviral Treatment

| Observed SVR (n = 19,286) (%, 95% CI) |

Observed or Imputed SVR (n = 20,703) (%, 95% CI)* |

|

|---|---|---|

| All patients | 89.6 (89.2–90.1) | 88.8 (88.4–89.3) |

| White | 89.8 (89.2–90.4) | 89.1 (88.5–89.7) |

| Black | 89.8 (89.1–90.6) | 89.0 (88.2–89.9) |

| Hispanic | 86.0 (83.8–88.1) | 85.2 (83.0–87.3) |

| Asian/PI/AI/AN | 90.7 (87.6–93.9) | 90.3 (87.0–93.6) |

| Declined/missing | 90.0 (88.7–91.2) | 89.0 (87.7–90.3) |

Imputed by multiple imputation using a logistic regression model that included duration of treatment together with 25 baseline patient characteristics shown in Table 1. The number of patients is slightly less than 21,095 due to missing data in the characteristics used to impute SVR.

Discussion

LDV/SOF, PrOD, SMV+SOF, and SOF-based antiviral regimens resulted in high SVR rates in all racial/ethnic groups among 21,095 veterans with HCV treated in the VA national health care system in 2014 and 2015. However, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, black (AOR = 0.77, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (AOR = 0.76, P = 0.007) patients were less likely to achieve SVR than white patients, a difference that was not explained by early treatment discontinuations. Among genotype 1–infected patients treated with LDV/SOF monotherapy, black patients had significantly lower SVR than white patients when treated for 8 weeks but not when treated for 12 weeks.

Our results represent a dramatic deviation from the interferon-based antiviral treatments, which consistently reported much larger gaps in SVR between white patients and black or Hispanic patients, in both clinical trials and real-world studies.(21) The narrowing of the SVR gap between black and white patients may be related to the fact that the efficacy of DAA-based regimens does not appear to be dependent on interleukin-28B gene (IL28B) polymorphisms, which strongly influence response to interferon. Disparities between black and white patients in treatment responses were in part related to the lower prevalence of the CC allele of the IL28B gene in black patients, which is associated with higher rates of SVR in response to interferon-based regimens.(38) In clinical trials of DAA regimens, however, SVR rates are very similar between IL28B CC and non-CC patients.(1,3–8,39–41)

Racial/ethnic “minority” groups, such as blacks and Hispanics, are underrepresented in antiviral treatment clinical trials, despite the fact that black patients and some Hispanic groups, such as Puerto Ricans, are overrepresented among HCV-infected patients. Thus, it is frequently unclear whether the results of clinical trials that are based mostly on white patients will apply to racial/ethnic “minority” groups in real-world clinical practice. Our results offer some reassurance that black and Hispanic patients achieve SVR rates comparable to those of white patients in real-world clinical practice, although small gaps still exist.

Some differences in baseline characteristics by racial/ethnic group are important to highlight and inform the interpretation of differences in SVR rates. First, the prevalence of genotype 2 or 3 HCV infection was dramatically lower in black patients (3.0% and 0.7%, respectively) than other racial/ethnic groups. These differences in genotype distribution by race have been reported.(12–16) Genotypes 2 and 3 were regarded as “favorable” in the interferon era but are now associated with the lowest SVR rates in response to DAA therapy. It is therefore critical to stratify or adjust for genotype when comparing different racial groups. Second, the prevalence of cirrhosis was lower in black patients (30.7%) and higher in Hispanic patients (48.7%) compared to white (35.2%) or Asian/PI/AI/AN (35.1%) patients (Table 1). The differences in prevalence of cirrhosis by race/ethnicity are consistent with previous reports(42,43) and were mirrored in the proportions with elevated FIB-4 scores, elevated serum bilirubin levels, or reduced platelet count (Table 1). It has been speculated that the higher prevalence in Hispanics and the lower prevalence in blacks of fatty liver disease, visceral obesity, and insulin resistance contribute to the corresponding risk of cirrhosis among HCV-infected patients.(42,43) Cirrhosis is associated with lower SVR rates and therefore has to be adjusted for when investigating the associations between race/ethnicity and SVR. Indeed, adjustment for genotype and cirrhosis is responsible for “reversing” the unadjusted odds ratio in black patients from a value slightly greater than 1 (i.e., more likely to respond) to an AOR <1 (i.e., less likely to respond) (Table 3).

We explored whether the disparity between white, black, and Hispanic patients could be related to different rates of early treatment discontinuation. With interferon-based regimens, rates of early discontinuation were very high but similar between black and white patients (16,33) and therefore did not contribute to the racial gap in SVR. Rates of early discontinuation of DAA regimens in our study are much lower than what has been observed with interferon. Although early discontinuation was slightly more common in black and Hispanic patients compared to white patients, when we adjusted for duration of antiviral treatment (which accurately captures early discontinuations), there was minimal impact on the AORs for the association between race/ethnicity and SVR. Thus, differences in early discontinuation of treatment do not account for the association between race/ethnicity and SVR that we identified in multivariable analyses.

In the ION-4 clinical trial of HIV/HCV coinfected patients treated with 12 weeks of LDV/SOF monotherapy, SVR rates were significantly lower in black (90%, 95% CI 83–95) than in white (99%, 95% CI 97–100) patients.(9) We also found a difference in SVR between black (90.3%, 95% CI 87.1–92.7) and white (93.9%, 95% CI 89.2–96.6) patients, but it was smaller and did not reach statistical significance in either crude or adjusted analyses. Limiting to genotype 1–infected patients who received LDV/SOF monotherapy, as in the ION-4 trial, black patients again had a lower SVR (92.0%, 95% CI 88.3–94.7) than white patients (95.1%, 95% CI 87.3–98.1), which was nonsignificant.

It is recommended that a short, 8-week LDV/SOF monotherapy regimen “can be considered,”(44) “with caution and at the discretion of the practitioner,”(37) in treatment-naive, genotype 1–infected patients without cirrhosis with an HCV viral load <6 million. Indeed, these 8-week regimens were commonly used in the VA and resulted in high overall SVR rates.(45) However, our results as well as other recent VA studies,(46) show that black patients had significantly lower SVR than white patients when treated with 8 weeks but not when treated with 12 weeks of LDV/SOF. Furthermore, recent pooled analyses of data from the ION-1, ION-2, and ION-3 clinical trials, which evaluated the efficacy of LDV/SOF with or without RIBA for treatment of genotype 1 HCV infection, reported that among patients treated with LDV/SOF monotherapy for 8 weeks, the relapse rate was higher (7/81 or 8.6%) and the SVR rate lower (91.3%) in black patients than nonblack patients (relapse rate 13/348 [3.7%] and SVR rate 96.2%).(20,47) Collectively, these results suggest that the 8-week regimens should perhaps be avoided in black patients and are in agreement with the most recent combined guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America,(44) which suggest that “shortening treatment to less than 12 weeks is not recommended for HIV-infected patients, African-American patients, or those with known IL28 polymorphism CT or TT.”

In multivariate models, patients in the Asian/PI/AI/AN race/ethnicity group did not have a statistically significant difference in likelihood of SVR compared to white patients (Table 3). Unadjusted SVR rates in Asian/PI/AI/AN patients were also similar to other groups (Table 2). This is a slight departure from trends seen with interferon-based treatments, which typically produced significantly higher rates of SVR in Asian patients than in white, black, and Hispanic patients.(18,48) Asian patients have a higher frequency of the favorable CC IL28B allele,(38) partly accounting for better response to interferon-based treatments. The elimination of the SVR gap between Asian patients and white patients may be due to the lack of impact of the IL28B genotype on response to DAA-based regimens.

An important limitation of our study is that a significant proportion (12%) of patients had a missing or declined race/ethnicity designation. This could potentially have biased our results if one race/ethnicity group was more likely than others to have a missing race designation, leading to a high proportion of missing results for that particular group. However, the baseline characteristics and SVR rates of patients with missing race/ethnicity data did not mirror any one particular race group and instead were generally an average of all the race groups. It is therefore unlikely that the missing data biased our results in any particular direction.

Also, our study is limited by missing SVR data in 8.6% of patients, which may lead to overestimated SVR rates among those with available SVR data, if those with missing SVR data are significantly less likely to have achieved SVR. We think this is unlikely for two reasons. First, patients with missing SVR data were very similar to those with available SVR data in baseline characteristics that predict SVR (Supporting Table S2). Although early discontinuation of treatment in <8 weeks was more common in patients with missing SVR data (24.8% versus 4.4%), the majority of patients with missing SVR completed 8 or more weeks of treatment, demonstrating that patients with missing SVR data were not patients who “dropped out” of treatment or were “lost to follow-up” but rather patients (or physicians) who were simply delinquent in getting their SVR viral load measured after the end of their treatment—not an uncommon phenomenon outside of clinical trials. Second, we used comprehensive multiple imputation models that included duration of treatment in addition to baseline, pretreatment characteristics to impute the missing SVR data and found only an insubstantial reduction in SVR after imputation (Table 4), suggesting that it is unlikely that our results of observed SVR are biased toward overestimation due to the missing SVR data.

Our results demonstrate that DAA-based regimens are highly effective for treatment of chronic HCV among all race and ethnicity groups in real-world practice. Although black race and Hispanic ethnicity are still associated with lower likelihood of SVR in multivariate analysis, DAAs hold promise in closing the SVR gap between different race/ethnicity groups. Future studies of HCV treatment regimens should ensure adequate inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities in study populations to better detect differences in clinical subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Clinical Science Research and Development, Office of Research and Development, US Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit Review grants I01CX000320 and I01CX001156, to G.N.I.).

Abbreviations:

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- Asian/PI/AI/AN

Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Alaska Native

- CI

confidence interval

- DAA

direct-acting antiviral

- FIB-4

Fibrosis-4

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IL

interleukin

- LDV

ledipasvir

- PEG

pegylated interferon

- PrOD

paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir

- RIBA

ribavirin

- SMV

simeprevir

- SOF

sofosbuvir

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- VA

Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.28901/suppinfo.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

REFERENCES

- 1 ).Andreone P, Colombo MG, Enejosa JV, Koksal I, Ferenci P, Maieron A, et al. ABT-450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infection. Gastroenterology 2014;147:359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 ).Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J, Cohen D, Luo Y, Cooper C, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3 ).Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Rossaro L, Bernstein D, Lawitz E, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1879–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 ).Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R, Kowdley KV, Zeuzem S, Agarwal K, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370: 1973–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 ).Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykal T, Marinho RT, Poordad F, Bourliere M, et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014;370: 1604–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 ).Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 ).Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 ).Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, Sigal S, Nelson DR, Crawford D, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1594–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9 ).Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M, Workowski K, Ruane P, Towner WJ, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2015;373:705–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 ).Kwo P, Gitlin N, Nahass R, Bernstein D, Etzkorn K, Rojter S, et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir (12 and 8 weeks) in hepatitis C virus genotype 1-infected patients without cirrhosis: OPTIMIST-1, a phase 3, randomized study. HEPATOLOGY 2016;64:370–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 ).Lawitz E, Matusow G, DeJesus E, Yoshida EM, Felizarta F, Ghalib R, et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: a phase 3 study (OPTIMIST-2). HEPATOLOGY 2016;64:360–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 ).Brau N, Bini EJ, Currie S, Shen H, Schmidt WN, King PD, et al. Black patients with chronic hepatitis C have a lower sustained viral response rate than non-blacks with genotype 1, but the same with genotypes 2/3, and this is not explained by more frequent dose reductions of interferon and ribavirin. J Viral Hepat 2006;13:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13 ).Jeffers LJ, Cassidy W, Howell CD, Hu S, Reddy KR. Peginter-feron alfa-2a (40 kd) and ribavirin for black American patients with chronic HCV genotype 1. HEPATOLOGY 2004;39:1702–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 ).Flamm SL, Muir AJ, Fried MW, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Bzowej NH, et al. Sustained virologic response rates with telaprevir-based therapy in treatment-naive patients evaluated by race or ethnicity. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15 ).Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16 ).Muir AJ, Bornstein JD, Killenberg PG. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-Hispanic whites. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2265–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17 ).Rodriguez-Torres M, Jeffers LJ, Sheikh MY, Rossaro L, Ankoma-Sey V, Hamzeh FM, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in Latino and non-Latino whites with hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2009;360:257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18 ).Hu KQ, Freilich B, Brown RS, Brass C, Jacobson IM. Impact of Hispanic or Asian ethnicity on the treatment outcomes of chronic hepatitis C: results from the WIN-R trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19 ).Feuerstadt P, Bunim AL, Garcia H, Karlitz JJ, Massoumi H, Thosani AJ, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis C treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in urban minority patients. Hepatology 2010;51:1137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20 ).Wilder JM, Jeffers LJ, Ravendhran N, Shiffman ML, Poulos J, Sulkowski MS, et al. Safety and efficacy of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in black patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a retrospective analysis of phase 3 data. Hepatology 2016;63:437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 ).Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Green PK. Similar effectiveness of boceprevir and telaprevir treatment regimens for hepatitis C virus infection on the basis of a nationwide study of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1371–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22 ).Ioannou GN, Scott JD, Yang Y, Green PK, Beste LA. Rates and predictors of response to anti-viral treatment for hepatitis C virus in HIV/HCV co-infection in a nationwide study of 619 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:1373–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23 ).US Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Services Research & Development. Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure; Available at: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 24 ).Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and FibroTest. Hepatology 2007;46:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 ).Kramer JR, Giordano TP, Souchek J, Richardson P, Hwang LY, El-Serag HB. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26 ).Ioannou GN, Splan MF, Weiss NS, McDonald GB, Beretta L, Lee SP. Incidence and predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27 ).Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson PA, Duan Z, et al. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28 ).Ioannou GN, Bryson CL, Weiss NS, Miller R, Scott JD, Boyko EJ. The prevalence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. HEPATOLOGY 2013;57:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29 ).Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30 ).Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001–2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1471–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31 ).Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Mole LA. Predictors of response of US veterans to treatment for the hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2007;46:37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32 ).Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Giordano TP, Petersen LA, El-Serag HB. Importance of patient, provider, and facility predictors of hepatitis C virus treatment in veterans: a national study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33 ).Beste LA, Ioannou GN, Larson MS, Chapko M, Dominitz JA. Predictors of early treatment discontinuation among patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C and implications for viral eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34 ).Kanwal F, Hoang T, Kramer JR, Asch SM, Goetz MB, Zeringue A, et al. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1182–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35 ).Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(Suppl. 2):B10–B21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36 ).Yoshida EM, Sulkowski MS, Gane EJ, Herring RW Jr, Ratziu V, Ding X, et al. Concordance of sustained virological response 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2015;61:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37 ).Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2016. Available at: https://www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/harvoni/harvoni_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38 ).Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009;461:399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39 ).Zeuzem S, Dusheiko GM, Salupere R, Mangia A, Flisiak R, Hyland RH, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1993–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40 ).Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1878–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41 ).Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1867–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42 ).Verma S, Bonacini M, Govindarajan S, Kanel G, Lindsay KL, Redeker A. More advanced hepatic fibrosis in hispanics with chronic hepatitis C infection: role of patient demographics, hepatic necroinflammation, and steatosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1817–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43 ).El-Serag HB, Kramer J, Duan Z, Kaneal F. Racial differences in the progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1427–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44 ).American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Available at: http://www.hcvguidelines.org Accessed January 25, 2016.

- 45 ).Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Chang MF, Green PK, Lowy E, Tsui JI, et al. Effectiveness of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir regimens for treatment of patients with hepatitis C in the Veterans Affairs National Health Care System. Gastroenterology 2016;151:457–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46 ).Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA. Real-world effectiveness of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in 4,365 treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C-infected patients. HEPATOLOGY 2016;64:405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47 ).O’Brien TR, Lang Kuhs KA, Pfeiffer RM. Subgroup differences in response to 8 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for chronic hepatitis C. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014;1:ofu110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48 ).Missiha S, Heathcote J, Arenovich T, Khan K; Canadian Pegasys Expanded Access Group. Impact of Asian race on response to combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102: 2181–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.