Abstract

Purpose

The loss of nutrient supply is a suspected contributor of intervertebral disc degeneration. However, the extent to which low nutrition affects disc annulus fibrosus (AF) cells is unknown as nutrient deprivation has mainly been investigated in disc nucleus pulposus cells. Hence, an experimental study was designed to clarify effects of limited nutrients on disc AF cell fate, including autophagy, the process by which cells recycle their own damaged components.

Methods

Rabbit disc AF cells were cultured in different media with varying serum concentrations under 5% oxygen. Cellular responses to changes in serum and nutrient concentrations were determined by measuring proliferation and metabolic activity. Autophagic flux in AF cells was longitudinally monitored using imaging cytometry and Western blotting for LC3, HMGB1, and p62/SQSTM1. Apoptosis (TUNEL staining and cleaved caspase-3 immunodetection) and cellular senescence (senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay and pl6/INK4A immunodetection) were measured.

Results

Markers of apoptosis and senescence increased while cell proliferation and metabolic activity decreased under the withdrawal of serum and of nutrients other than oxygen, confirming cellular stress. Time-dependent increases in autophagy markers, including LC3 puncta number per cell, LC3-II expression, and cytoplasmic HMGB1 were observed under conditions of reduced nutrition while an autophagy substrate, p62/SQSTM1, decreased over time. Collectively, these findings suggest increased autophagic flux in disc AF cells under serum and nutrient deprivation.

Conclusions

Disc AF cells exhibit distinct responses to serum and nutrient deprivation. Cellular responses include cell death and quiescence in addition to reduced proliferation and metabolic activity, as well as activation of autophagy under conditions of nutritional stress

Keywords: Intervertebral disc, Annulus fibrosus (AF) cells, Serum and nutrient deprivation, Autophagy, Apoptosis, Senescence

INTRODUCTION

The intervertebral disc is the largest avascular organ in the body [1]. Disc cells, and in particular innulus fibrosus (AF) cells, depend on the diffusion from blood vessels at the disc margins to obtain nutrients [1]. Therefore, decreased blood supply, subchondral bone sclerosis, and endplate calcification, all of which occur with mechanical stress, injury, smoking, and aging, can reduce transport of nutrients to the disc. The loss of nutrient supply is a suspected initiator of disc degeneration.

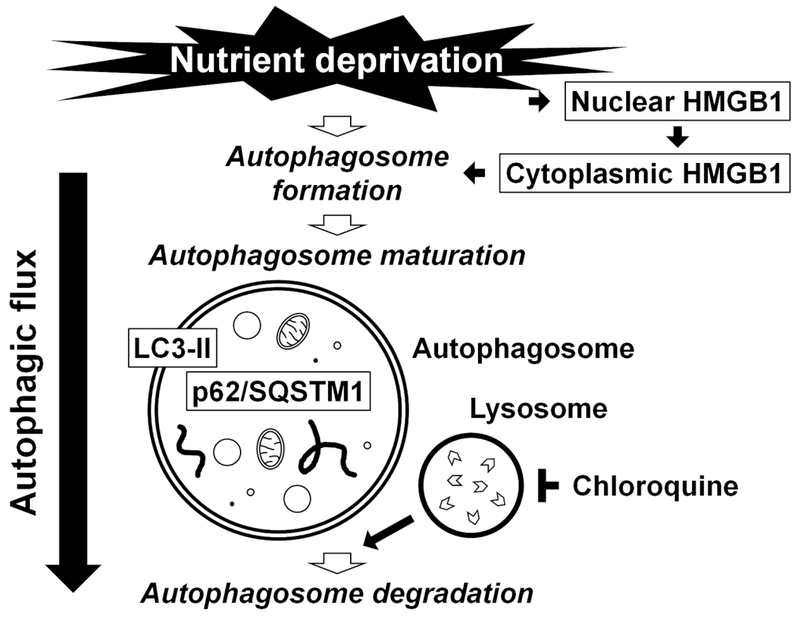

Growing evidence suggests a close link between nutrient deprivation and the resultant cellular stress and disc cell fate. For example, the loss of functional cells with proliferative capacity in response to stress may play a role in driving age-related disc degeneration [6]. In fact, programmed cell death (apoptosis) [2] and irreversible cell growth arrest (senescence) [3] increase with disc degeneration [4,5] and may represent an important cellular response to stress in the intervertebral disc. In addition to these cell fates, the harsh environment of low nutrition, pH, and oxygen concentration in the disc [1] raises the question of whether resident cells utilize autophagy to cope with these stressful conditions. In fact, disc cellular autophagy has recently received increasing interest [10–12]. Autophagy, the intracellular process by which cells degrade and recycle their own damaged components to provide building blocks for biosynthesis or to maintain cellular energy levels, is an important cell stress-response mechanism for survival [7]. Under stress, especially nutrient deprivation, autophagy-related proteins are activated for the formation and maturation of the autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome, the enclosed cargo is degraded, and its constituents are released and reutilized. The microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) is a ubiquitin-like protein that is present in the cytosolic form, LC3-I, or the phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form, LC3-II. The LC3-II is the only protein marker reliably associated with autophagosome maturation [8]. High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) is a DNA-binding nuclear protein that is also an extracellular damage-associated molecular pattern molecule. Released cytoplasmic HMGB1 directly interacts with autophagy-related proteins, resulting in the autophagosome formation [9]. The p62/sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1) is a ubiquitin-binding protein that serves as a link between LC3 and ubiquitinated substrates. The P62/SQSTM1 and p62/SQSTM 1-bound polyubiquitinated proteins become incorporated into the completed autophagosome and are degraded in the autolysosome, thus demonstrating that their expression inversely correlates with levels of the autophagosome degradation [8]. Monitoring this dynamic process, autophagic flux, is essential to understand roles of autophagy in disc degeneration (Fig. 1), and published studies have not been conducted to unequivocally confirm and mechanistically examine disc AF cell autophagic flux. Furthermore, many in-vitro studies have been performed under conventional cell-culture conditions, e.g. 10–20% serum supplementation and normoxia, which are considerably different from the in-vivo situation [1]. Therefore, we here carefully and systematically examined AF cell fate using a cell-culture model system. We conducted detailed time-course experiments to measure autophagic flux in AF cells under varying degrees of nutrient withdrawal to clarify the fundamental relationships between nutrient supply and levels of AF cellular autophagy, apoptosis, and senescence.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration summarizing the process of autophagy examined in this study.

Under nutrient deprivation, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, resulting in the initiation of the autophagosome formation. The autophagosome maturation is driven by the conjugation of phosphatidylethanolamine with light chain 3 (LC3), leading to the formation of its autophagosome membrane-bound form, LC3-II. The p62/sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1) and p62/SQSTM1-bound polyubiquitinated proteins become incorporated into completed autophagosomes. The completed autophagosome fuses with the lysosome (inhibited by chloroquine), the enclosed cargo is degraded, and its constituents are released and reutilized. Understanding of autophagy requires monitoring this dynamic, multi-step process of autophagic flux.

Another motivation of our study was to clarify characteristics of disc annulus fibrosus (AF) cells under a limited supply of serum-related nutrients. Although it is known that the peripheral AF have a more abundant supply of oxygen and nutrients than the central nucleus pulposus (NP) [1], and under healthy conditions this is thought to be adequate, nutrient deprivation in the AF could arise from processes associated with degeneration. Therefore, in addition to the known importance of nutrient deprivation for NP cells, limited nutritional supply also has the potential to adversely affect AF cells, which has not been extensively studied. Hence, an experimental study was designed to assess disc AF cell fate by culturing in different media with varying serum concentrations to provide a graded supply of serum-related nutrients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

All animal and human cell harvesting were performed under the approval and guidance of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (1001336A-2 and 1001336B-2) and the Institutional Review Board (PRO12100603).

Antibodies and Reagents

The antibodies for LC3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), HMGB1 (Sigma-Aldrich), p62/SQSTM1 (Abeam, Cambridge, UK), cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), pl6/INK4A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were purchased and used per manufacturer instructions. The fluorescein-labeled terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) assay, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan), and PicoGreen double-stranded DNA quantification assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were purchased and used per manufacturer instructions. Immunofluorescent reagents including donkey-derived Alexa Fluor 488, 647, and 555 dyes and Hoechst 33342 and Western blotting reagents were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cell-culture reagents including Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture medium (F-12), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Four different lots of fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Penicillin and streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to all media at 1%. Chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 15 μM was used for autophagic LC3 turnover assay.

Concentrations of glucose and glutamine in media were reported by the manufacturer, with F-12 containing 10.01-mM D-glucose and 1-mM L-glutamine, DMEM containing 25-mM D-glucose and 4-mM L-glutamine, and HBSS containing 5.56-mM D-glucose and no addition of L-glutamine.

Cells

Discs from lumbar spines of six-month-old female New Zealand White rabbits (~2.5 kg) were harvested immediately postmortem. Human disc specimens were obtained from four patients undergoing cervical spinal canal stenosis surgery (age, 49.3 ± 7.5 yr; all male; Pfirrmann disc degeneration grade [13], 2.8 ± 0.5). The AF tissue from each disc was dissected and digested at 37°C in F-12 with 5% FBS and 0.2% pronase for 1 h and then 0.02% collagenase-P for 12 h. Isolated cells were cultured in F-12 with 10% FBS under 5% O2, and 80%-confluent cells were prepared for experiments.

First passage, monolayer rabbit or human disc AF cells were cultured under varying concentrations of nutrients and serum. HBSS or DMEM with the addition of 0 to 20% FBS were used. To test the influence of variability of serum factors, experiments were repeated andresults confirmed by using FBS from multiple lots. For cell proliferation assay, 5 × 104 cells/we were directly cultured for up to 336 h with media change every 48 h. For other assays, cells were pre-cultured in DMEM with 1% FBS 24 h followed by 10% FBS for 72 h (~80% confluence) and then cultured for up to 48 h. All experiments were carried out under 5% O2 to simulate the physiological environment of disc AF cells [14].

Cell proliferation assay

In a 6-well plate, 5 × 104 cells/well were cultured in HBSS or DMEM with 0–10% FBS for 0–336 h with media change every 48h. Cells were trypsinized and the cell number was counted using the trypan blue exclusion method.

Dehydrogenase activity, DNA amount, and cell metabolic activity assays

Total dehydrogenase activity and DNA amount was assessed by CCK-8 and PicoGreen, respectively. The CCK-8 absorbance (450 nm) and PicoGreen fluorescence (fluorescein) were measured using the VICTOR X3 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham. MA). Cell metabolic activity was calculated as dehydrogenase activity normalized to DNA amount.

Imaging cytometry

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with primary antibodies for autophagy markers LC3 [8] and HMGB1 [9] followed by staining with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies. Hoechst was used for counterstaining. The number of LC3 puncta and nuclear and cytoplasmic intensity of HMGB1 per cell were measured by the Cellomics ArrayScan VTI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described previously [9]. Imaging data were collected at ×20 at 25°C using the ArrayScan and Compartmental Analysis BioApplication version 3.5 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Up to 36 images of 500–1,000 cells for each treatment group were analyzed to obtain the mean nuclear and cytosolic HMGB1 intensity and LC3 fluorescence puncta number.

Western blotting

Total protein extracts were resolved on a 4–20% denaturing gel. Separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies for autophagy-related LC3 [8], HMGB1 [9], and p62/SQSTM1 [8], apoptosis-related cleaved caspase-3 [15], senescence-related pl6/INK4A [16], and actin loading control followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and images were taken using the ChemiDocXRS+ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Relative band intensity was quantified using the ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Immunofluorescence

After fixation, apoptotic cells were determined by TUNEL [17] or nuclear translocation of cleaved caspase-3 [15]. Senescent cells were identified by pl6/INK4A expression [16]. Hoechst was used for counterstaining. Images were obtained by the Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and Northern Eclipse software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, Canada). The number of TUNEL-positive cells and immunopositive cells for cleaved caspase-3 and pl6/INK4A was divided by total cell number, counted in ten random low-power fields (×100) using ImageJ. Multi-color immunofluorescence for autophagic LC3 and HMGB1, apoptotic cleaved caspase-3, and senescent pl6/INK4A was also performed. The percentage of immunopositive cells for LC3 and for pl6/INK4A in nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells was calculated similarly.

Colorimetric senescence assay

Senescent cells were identified by SA-β-gal assay using 1-mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside [18].

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD of four independent sample values (4 biological replicates). Each sample value was the average of duplicate or triplicate experiments using the same sample (2 or 3 technical replicates), unless otherwise indicated. Multi-way analysis of variance with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used to assess changes for effects of nutrient deprivation and time (n = 4). A mixed-design model was applied to dehydrogenase activity, DNA amount, and cell metabolic activity assays because of within-subject variability (n = 4). The Student t-test was utilized to compare immunopositivity (n = 4). The normality of distribution and homogeneity of variance were assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene test, respectively. When unequal, the Welch method was applied. Statistical significance was assessed with P<0.05 and P<0.01 using SPSS Statistics 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Reduced serum and nutrients decrease AF cell proliferation and metabolic activity

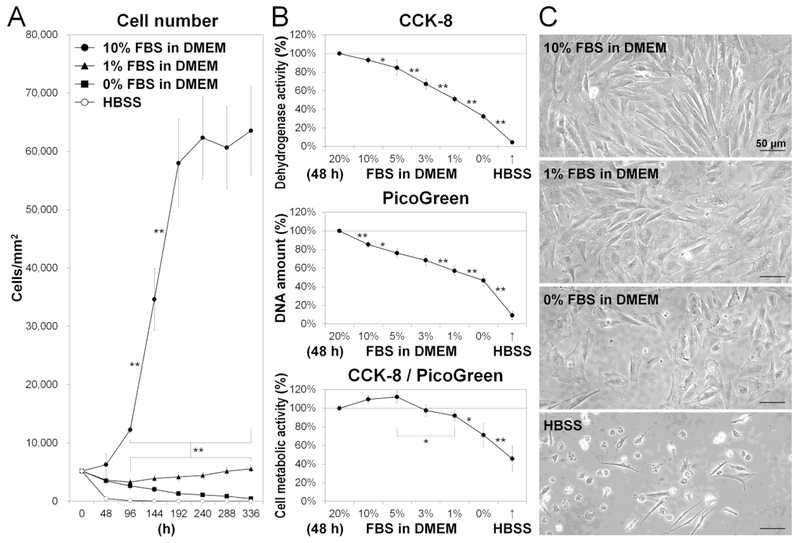

To characterize cellular responses to changes in serum-related nutrient supply, we investigated cell proliferation in HBSS, or DMEM with varying serum concentrations (0–10% FBS). Cell number decreased in HBSS and 0% FBS-supplemented DMEM, remained unchanged in 1% FBS-supplemented DMEM, and increased in 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM, although it reached confluence at 192 h, a limitation of the design (Fig. 2A). Hence, while serum starvation reduces cell number, nutrients supplied by DMEM with 1% FBS are sufficient to maintain the number of disc AF cells.

Fig. 2. Reduced serum and nutrients decrease disc cell proliferation and metabolic activity.

(A) Number of cells after 0-, 48-, 96-, 144-, 192-, 240-, 288-, and 336-h culture in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 0%, 1%, or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. (B) Dehydrogenase activity, DNA amount, and metabolic activity in cells after 48-h culture in HBSS or DMEM with 0%, 1%, 3%, 5%, 10%, or 20% FBS. Total dehydrogenase activity and DNA amount were assessed by the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and PicoGreen assay kit, respectively. Cell metabolic activity was calculated as dehydrogenase activity normalized to DNA amount. Data are mean ± SD expressed as the relative percentage of those in DMEM with 20% FBS (n = 4). Mixed-design ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. (C) Morphological cell appearance. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4).

To evaluate cell metabolism, we measured cell dehydrogenase activity and DNA amount in HBSS or DMEM with 0–20% FBS. Total dehydrogenase activity (via CCK-8) and DNA (via PicoGreen) decreased under reduced serum and nutrients (Fig. 2B), indicating changes in proliferation as well as in metabolic activity. However, cell metabolic activity, calculated as dehydrogenase activity normalized to DNA amount, remained relatively unchanged in DMEM with 3–20% FBS and decreased only with the lowest (0–1%) FBS concentration (Fig. 2B). Cell appearance became flat and enlarged in DMEM with 0–1% FBS while most cells were detached in HBSS (Fig. 2C). These findings suggest that disc AF cells respond to limited nutrition by decreasing cell proliferation and cell metabolism.

Reduced serum and nutrients increase AF cellular autophagy

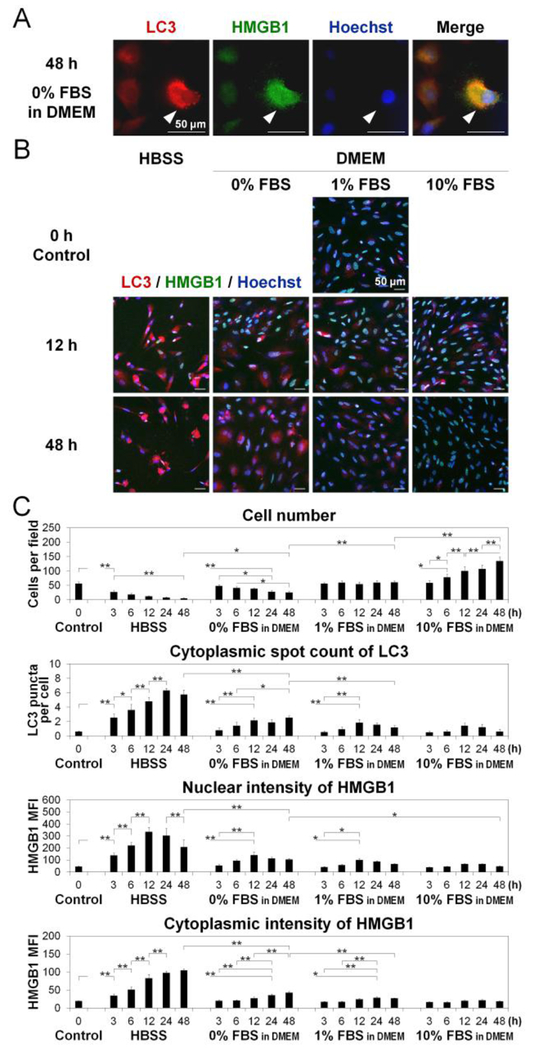

To monitor autophagic flux in AF cells (Fig. 1), we performed time-course LC3 puncta counting and nuclear and cytoplasmic HMGB1 measurement using imaging cytometry (Fig. 3A). The LC3 protein has two cytosolic forms. LC3-I, and the phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form, LC3-II [8]. LC3-II is recruited to the autophagosomal membrane, representing a marker of ongoing autophagy [8]. Therefore, counting LC3 puncta but not merely measuring LC3 expression is required when interpreting the immunofluorescence findings, as increased LC3 puncta indicate increased completed autophagosomes [8]. In this study, while the number of LC3 puncta per cell increased and peaked at 12 h in DMEM with ≥1% FBS, more pronounced increases in LC3 puncta were observed in HBSS and 0% FBS-supplemented DMEM, with the maximum levels seen at 24–48 h (Fig. 3BC). In response to stress, the DNA-binding nuclear protein HMGB1 translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, which is finally released extracellularly [9]. Increased cytoplasmic HMGB1 indicates the activation of Beclinl, that is essential to initiate autophagosome formation [9]. Nuclear HMGB1 intensity increased and peaked at 12–24 h but cytoplasmic HMGB1 intensity increased continuously with time through 48 h in HBSS and DMEM with 0–1% FBS (Fig. 3BC). Thus, the degree of changes in LC3 and HMGB1 corresponds to the severity of nutrient withdrawal. Reduced serum and nutrients activated the early (cytoplasmic HMGB1 translocation) and middle (LC3 puncta formation) phases of autophagic flux in disc AF cells.

Fig. 3. Reduced serum and nutrients activate disc cellular autophagy.

(A) Imaging cytometry for light chain 3 (LC3) (red) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (green) in cells after 48-h culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 0% fetal bovine serum (FBS), showing autophagic cells (white arrows). Hoechst (blue) was used for counterstaining. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (B) Time-course imaging cytometry for LC3 (red), HMGB1 (green), and Hoechst (blue) in cells after 0-, 3-, 6-, 12-, 24-, and 48-h culture in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) or DMEM with 0%. 1%. or 10% FBS. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (C) Changes in cell number per field, cytoplasmic spot count of LC3 per cell, and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of HMGB1 in the nucleus and cytoplasm per cell in time-course analysis. Imaging cytometric data were automatically collected from up to 36 fields and analyzed according to an established algorithm as described in the methods. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). Two-way analysis of variance with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

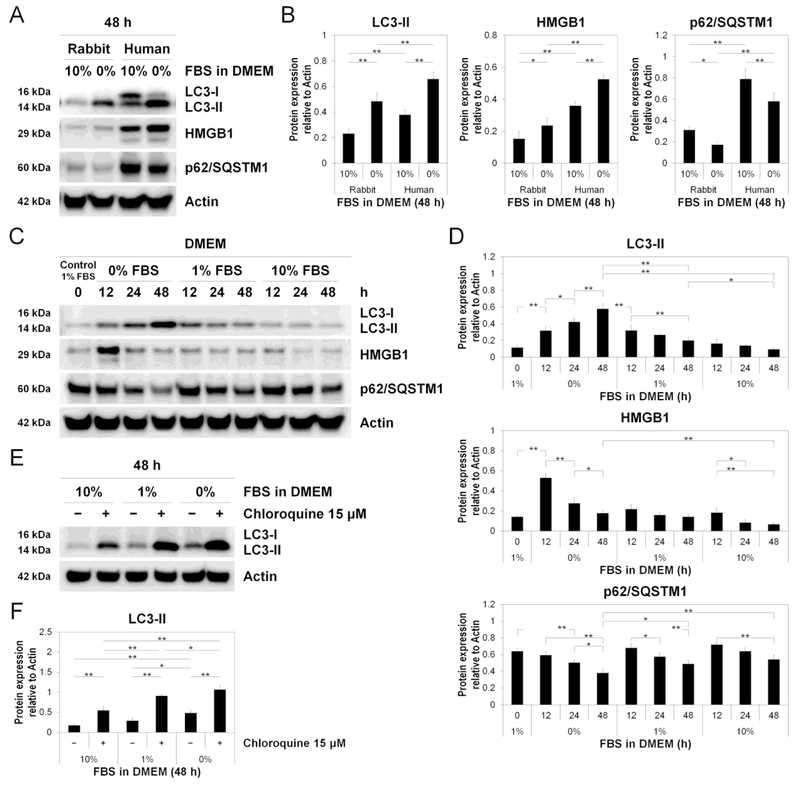

We then performed Western blotting for LC3, HMGB1, and also p62/SQSTM1, an autophagy-mediated degradation substrate, to assess the late phase of autophagic flux (autophagosome degradation). Western blotting demonstrated both LC3-I (16 kDa) and LC3-II (14 kDa) in human AF cells, but only LC3-II (14 kDa) in rabbit AF cells (Fig. 4AB). The absence of rabbit LC3-I may be due to a congenital loss or low expression of LC3-I, rapid conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II, or different epitope sequences of LC3-I undetectable by anti-human LC3 antibodies. As human samples showed decreased LC3-I and increased LC3-II, tracking the conversion of LC3 (soluble LC3-I to lipid-bound LC3-II) is the primary indicator of autophagic activity [8]. The lower baseline expression levels of HMGB1 and p62/SQSTM1 observed in young rabbit disc AF cells compared to degenerative human disc AF cells may also be explained by the differences in species and degeneration grades (Fig. 4AB).

Fig. 4. Reduced serum concentration executes disc cellular autophagy.

(A) Western blotting for light chain 3 (LC3), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and p62/sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1) in rabbit and human total protein extracts after 48-h culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 0% and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Actin was used as a loading control. Immunoblots shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (B) Changes in protein expression of LC3-II, HMGB1, and P62/SQSTM1 relative to actin in species analysis. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. (C) Time-course Western blotting for LC3, HMGB1, p62/SQSTM1, and actin in total protein extracts after 0, 12-, 24-, and 48-h culture in DMEM with 0%, 1%, or 10% FBS. Immunoblots shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (D) Changes in protein expression of LC3-II, HMGB1, and p62/SQSTM1 relative to actin in time-course analysis. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). Two-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. (E) Western blotting for LC3 and actin to assess LC3 turnover using 15-μM chloroquine in total protein extracts after 48-h culture in DMEM with 0%, 1%, or 10% FBS. Immunoblots shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (F) Changes in protein expression of LC3-II relative to actin in LC3 turnover assay. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). Two-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Western blotting demonstrated time-dependent LC3-II increases only in 0% FBS-supplemented DMEM, transient increases at 12 h in 1% FBS-supplemented DMEM, and no obvious increases in 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM (Fig. 4CD). Likewise, marked increases in total (nuclear + cytoplasmic) HMGB1 particularly at 12 h and decreases in p62/SQSTM1 were observed only in DMEM with 0% FBS (Fig. 4CD). Time-dependent decreases in p62/SQSTM1 indicate increased autophagic degradation.

We additionally performed LC3 turnover assay using a lysosomotropic compound, chloroquine. Chloroquine is known to induce the accumulation of autophagosomes with LC3-II by blocking lysosomal acidification, thus resulting in autophagy inhibition [8]. In Western blotting, chloroquine treatment increased LC3-II under all serum concentrations, even nutrient-rich 10% FBS (Fig. 4EF). These findings support the presence of both physiological and stress-response autophagy in disc AF cells.

Reduced serum concentration increases AF cellular apoptosis and cell growth arrest markers, which co-exist with autophagy

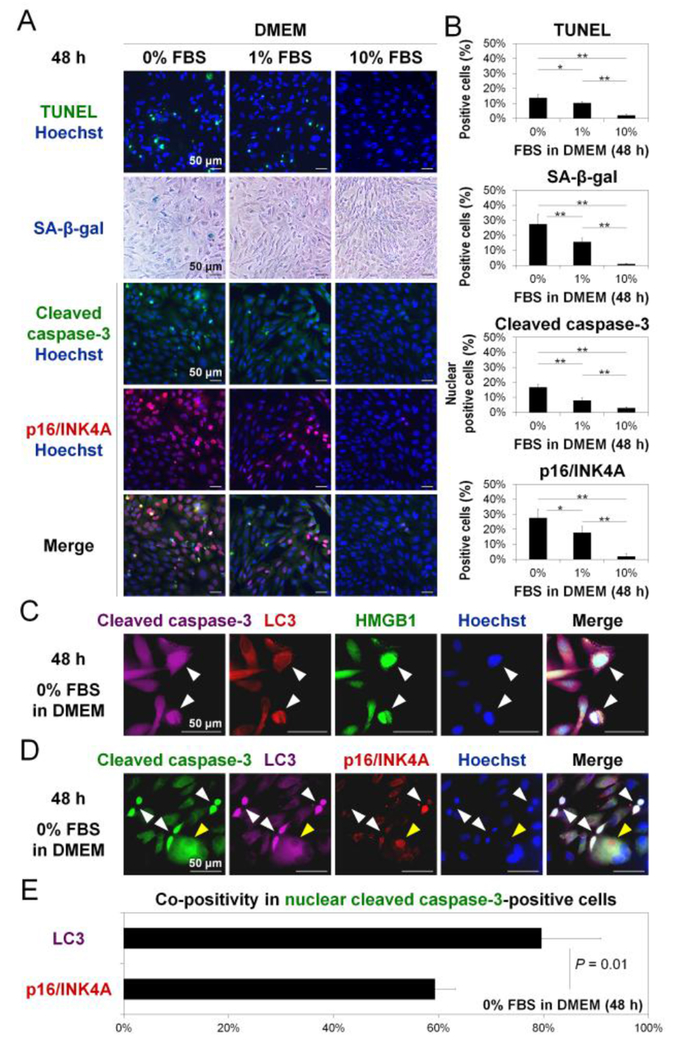

Apoptosis and cell growth arrest markers were measured to understand the involvement of other mechanisms that disc AF cells may utilize in response to graded serum deprivation. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells and nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells increased with decreasing FBS (Fig. 5AB). Positive TUNEL in the nucleus [17] and nuclear translocation of cleaved caspase-3 [15] indicate increased apoptosis under serum deprivation. The percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells and pl6/INK4A-positive cells also increased with diminishing FBS (Fig. 5AB). Many SA-β-gal-positive cells appeared flat and enlarged, a common morphologically feature of senescent cells [18]. Signals of pl6/INK4A were localized in the nucleus [16]. These findings indicate increased senescence or quiescence following serum deprivation.

Fig. 5. Reduced serum concentration increases disc cellular apoptosis and senescence, which co-exist with autophagy.

(A) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining (green), senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining (blue), and immunofluorescence for cleaved caspase-3 (green) and pl6/INK4A (red) in cells after 48-h culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 0%, 1%, or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Hoechst (blue) was used for fluorescent counterstaining. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (B) Changes in the percentage of positive cells for TUNEL, SA-β-gal, nuclear cleaved caspase-3, and pl6/INK4A in serum deprivation. The number of total and positive cells was counted in ten random low-power fields (×100). Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). One-way analysis of variance with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. (C) Immunofluorescence for cleaved caspase-3 (purple), light chain 3 (LC3) (red), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (green), and Hoechst (blue) in cells after 48-h culture in DMEM with 0% FBS. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (D) Immunofluorescence for cleaved caspase-3 (green), LC3 (purple), pl6/INK4A (red), and Hoechst (blue) in cells after 48-h culture in DMEM with 0% FBS. Nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells are indicated by white arrows. Nuclear cleaved caspase-3-negative but pl6/INK4A-positive cells are indicated by yellow arrows. Images shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (E) The percentage of co-positivity for LC3 or p16/INK4A in nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in DMEM with 0% FBS at 48 h. The number of positive cells was counted in ten random low-power fields (×100). Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). The Student t-test was used.

We then examined the extent to which markers of autophagy were concurrently present in apoptotic cells. Many nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells simultaneously showed LC3 puncta formation, nuclear HMGB1 elevation, and cytoplasmic HMGB1 release (Fig. 5C). Next, we examined the co-localization of autophagy and senescence markers in apoptotic cells. Nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells demonstrated a higher immunopositivity for cytoplasmic LC3 than nuclear pl6/INK4A (Fig. 5DE). Nuclear cleaved caspase-3-negative but pl6/INK4A-positive cells, i.e., non-apoptotic growth arrested cells, also showed the accumulation of LC3 puncta but the degree was markedly lower than apoptotic cells (nuclear cleaved caspase-3-positive cells) (Fig. 5D). This provides evidence that (1) autophagy occurs during both processes of apoptosis and senescence or quiescence in disc AF cells and (2) the degree of autophagic response in apoptosis is greater than in conditions of growth arrest.

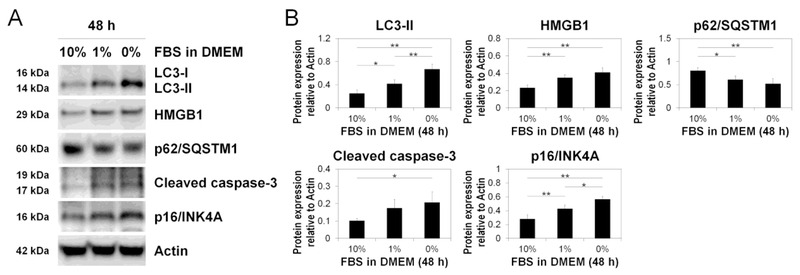

Western blotting showed increased LC3-II, HMGB1, cleaved caspase-3, and p16/INK4A and decreased p62/SQSTM1 with serum withdrawal (Fig. 6AB). These findings confirmed our imaging findings (Fig. 5ABCDE) and indicate concurrent induction of disc AF cellular autophagy, apoptosis, and quiescence under serum deprivation.

Fig. 6. Reduced serum concentration increases disc cellular autophagy, apoptosis, and senescence.

(A) Western blotting for light chain 3 (LC3), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), p62/sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1), cleaved caspase-3, and pl6/INK4A in total protein extracts after 48-h culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 0%, 1%, or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Actin was used as a loading control. Immunoblots shown are representative of four experiments with similar results (n = 4). (B) Changes in protein expression of LC3-II, HMGB1, p62/SQSTM1, cleaved caspase-3. and pl6/INK4A relative to actin in serum deprivation. Data are mean ± SD (n = 4). One-way analysis of variance with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this study, serum and nutrient deprivation decreased disc AF cell proliferation and metabolic activity and increased apoptosis and senescence or quiescence along with autophagy. Enhanced autophagy may indicate an adapting response of disc AF cells to nutritional stress, ind further mechanistic understanding of the interesting finding of disc AF cellular autophagy intersecting with apoptosis and senescence is warranted.

The decreased cell proliferation and metabolic activity under reduced serum and nutrients indicate cellular stress and correlate well with stress-response autophagy induction in disc AF cells. Then, we carefully and quantitatively monitored autophagic flux (autophagosome formation, maturation, and degradation) in disc AF cells by time-course measurement of a panel of autophagy markers LC3, HMGB1, and p62/SQSTM1 and blocking the degradation step of autophagy. By quantitation of intracellular LC3 puncta number and LC3-II amount or ratio to LC3-I, our findings established the dynamic response of autophagy in disc AF cells under limited serum and nutrition. Further, LC3 turnover, not simply expression, as measured through lysosomal inhibition (e.g. chloroquine) was critical to elucidate the net effect of stress. Autophagy was also confirmed by the degradation of autophagy substrates p62/SQSTM1. Through the use of these mechanistic approaches, our findings uncover the importance of measuring autophagic flux to fully appreciate roles of disc AF cellular autophagy, and add substantially to previous studies reporting the presence of autophagic markers in disc AF cells.

Time-dependent changes in the expression and localization of HMGB1 in AF cells is noteworthy. Independent measurement of nuclear and cytoplasmic HMGB1 revealed a close association of cytoplasmic HMGB1 intensity with LC3 puncta formation. This suggests the usefulness of cytoplasmic HMGB1 as an autophagy sensor in adult disc AF cells, similar to embryonic fibroblasts and cancer cells [9]. Stress-reactive cytoplasmic translocation, followed by extracellular release, of HMGB1 nuclear protein was supported through Western blotting for total (nuclear + cytoplasmic) HMGB1 expression. On the other hand, disc AF cells exhibited weaker and less localized expression of nuclear HMGB1 than embryonic fibroblasts or cancer cells [9]. Moreover, nuclear HMGB1 levels changed under limited nutrition. We then observed apoptotic cells expressing elevated nuclear HMGB1. Nuclear retention of HMGB1 occurs during apoptosis because of post-translational modifications that affect chromatin binding [19]. Thus, while roles of HMGB1 in disc disease need to be further studied, these data are the first to demonstrate a role of cytoplasmic HMGB1 as a useful autophagy marker in disc AF cells. Interestingly, media change to DMEM with 10% FBS including more abundant nutrients also induced transient but visible changes at 12 h in the expression levels of total HMGB1, suggesting that supplementation of excessive nutrients could be a stimulus to disc AF cells, and HMGB1 might be more sensitive as a stress sensor than autophagy markers.

The serum and nutrient deprivation-induced increases in disc AF cell apoptosis, senescence, and autophagy are consistent with prior reports [10,20,21]. To undertake a comprehensive and detailed exploration of how serum and nutrient deprivation modulates disc AF cell fate, we analyzed the co-existence of these cellular adaptive mechanisms. Under stress, autophagy was induced in disc AF cells that undergo cell growth arrest and apoptosis. However, levels of autophagy activation were much higher in apoptotic than senescent or quiescent disc AF cells Whether autophagy activation is an adaptive response for survival or mediates apoptosis or senescence in disc AF cells under serum and nutrient deprivation awaits further investigation. Importantly, while markers consistent with upregulation of senescent pathways were noted to be increased, differentiation from cellular quiescence could not be definitively determined under the conditions employed. As senescent cells are characterized by an increased resistance to apoptosis [22], further mechanistic studies between apoptosis and senescence in disc AF cells are required.

A relatively rapid development of cell growth arrest during proliferating cultures of disc AF cells was observed and should be noted. Primary AF disc cell cultures are speculated to be fairly vulnerable based on the difference between the in-vitro and in-vivo environment [1]. Thus, nutrient deprivation-induced quiescence observed in this study could be distinct from oncogene- or oxidative stress-induced senescence [23], which were not definitively differentiated in the current study. Additionally, it should be noted that false positive SA-β-gal staining may appear in confluent cell cultures, and therefore may not definitively indicate cell senescence [24].

Ni et al. previously reported effects of serum starvation in disc AF cells under normoxia [10]. In contrast, our study was performed under a hypoxic condition, which is more physiologic [1]. In addition, our study analyzed apoptosis and senescence and provided evidence supporting the complex network of cellular responses to serum and nutrient deprivation. Further, our time-course studies established autophagic flux in disc AF cells through measuring autophagic markers at carefully titrated serum concentrations. It should be emphasized that temporal autophagic flux, not mere detection of autophagic markers, needs to be established in order to demonstrate the presence and relevance of autophagy in the intervertebral disc.

An experimental limitation of our in-vitro study is the use of various concentrations of FBS for the control of the nutritional level, obscuring the impact of specific nutrients. It is possible that concentrations of individual FBS components, such as glucose and other small metabolites (pyruvate, amino acids, and other small metabolites), were responsible for the observed results, and cannot be distinguished. However, the use of FBS as a nutritional source is relevant since glucose is not the only carbon source in the disc in vivo. In addition, serum-dependent experiments are also heterogeneous across lots. To reduce this possible variability, we analyzed samples consisting of culture with different FBS lots; in fact, our results were consistent regardless of the lots of FBS used. Additionally, in-vitro monolayer culture of disc AF cells may limit physiological relevance to the in-vivo situation, although the laminar AF is better simulated in monolayer than the gelatinous NP. Also, we used rabbit cells for most experiments due to the reduced variability in phenotype compared to degenerative human cells; nevertheless, the limited availability and enormous variability of human cells is a limitation in completely characterizing the response in human cells. Further investigations to dissect human disc AF cellular autophagy are warranted.

Caution in interpreting our results is also advised. We utilized 5% oxygen in these experiments, however, the in-vivo oxygen concentration differ slightly in different AF regions [1]. In addition, in a healthy state, disc AF cells may not directly come into contact with serum proteins because of barriers at the capillary wall and the low permeability of AF matrix to large molecules [1]. However, in an injured disc and during the process of degeneration, with injury to blood vessels and associated leakage as well as neovascularization, exposure to blood proteins is possible. This study provides supportive information to understand pathological states such as degeneration and herniation, resulting in AF rupture, neovascularization, and possible exposure to serum proteins.

In conclusion, serum and nutrient deprivation reduces disc AF cell proliferation and metabolic activity, induces the dynamic activation of disc AF cellular autophagy, while also increasing apoptosis and senescence or quiescence. This study contributes to the current understanding of disc AF cell fate and lays a strong technical foundation for future research to explore roles of autophagy in disc degeneration-related diseases through loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Drs. Thomas P. Lozito (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA), Mayumi Morizane (Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Magee-Womens Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA), Masahiro Shuda (Cancer Virology Program, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA), and Tetsuya Watanabe (Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Asthma Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for their expertise. We also thank Mr. Kevin Ngo and Ms. Qing Dong (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by The Albert B. Ferguson, Jr., M.D. Orthopaedic Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, NIH AG044376, and The Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

TY, WB, HM, RH, KT, YK, KN, MK, NV, ML, and GS have no conflicts of interest to declare. JDK has received research grants from Stryker and Synthes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Urban JP, Smith S, Fairbank JC (2004) Nutrition of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29 (23):2700–2709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs Y, Steller H (2011) Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell 147 (4):742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lombard DB, Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Franco S, Gostissa M, Alt FW (2005) DNA repair, genome stability, and aging. Cell 120 (4):497–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA (2007) Accelerated cellular senescence in degenerate intervertebral discs: a possible role in the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res Ther 9 (3):R45. doi: 10.1186/ar2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurube T, Hirata H, Kakutani K, Maeno K, Takada T, Zhang Z, Takayama K, Matsushita T, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M, Nishida K (2014) Notochordal cell disappearance and modes of apoptotic cell death in a rat tail static compression-induced disc degeneration model. Arthritis Res Ther 16 (1):R31. doi: 10.1186/ar4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vo NV, Hartman RA, Patil PR, Risbud MV, Kletsas D, Iatridis JC, Hoyland JA, Le Maitre CL, Sowa GA, Kang JD (2016) Molecular mechanisms of biological aging in intervertebral discs. J Orthop Res 34 (8):1289–1306. doi: 10.1002/jor.23195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine B, Kroemer G (2008) Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132 (1):27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A, Adachi H, Adams CM, Adams PD, Adeli K, Adhihetty PJ, Adler SG, Agam G, Agarwal R, Aghi MK, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguilar PV, Aguirre-Ghiso J, Airoldi EM, Ait-Si-Ali S, Akematsu T, Akporiaye ET, Al-Rubeai M, Albaiceta GM et al. (2016) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 12 (1):1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang D, Kang R, Livesey KM, Cheh CW, Farkas A, Loughran P, Hoppe G, Bianchi ME, Tracey KJ, Zeh HJ 3rd, Lotze MT (2010) Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol 190 (5):881–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni BB, Li B, Yang YH, Chen JW, Chen K, Jiang SD, Jiang LS (2014) The effect of transforming growth factor beta1 on the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in the annulus fibrosus cells under serum deprivation. Cytokine 70 (2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.07.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyazaki S, Kakutani K, Yurube T, Maeno K, Takada T, Zhang Z, Kurakawa T, Terashima Y, Ito M, Ueha T, Matsushita T, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M, Nishida K (2015) Recombinant human SIRT1 protects against nutrient deprivation-induced mitochondrial apoptosis through autophagy induction in human intervertebral disc nucleus pulposus cells. Arthritis Res Ther 17:253. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0763-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito M, Yurube T, Kakutani K, Maeno K, Takada T, Terashima Y, Kakiuchi Y, Takeoka Y, Miyazaki S, Kuroda R, Nishida K (2017) Selective interference of mTORC1/RAPTOR protects against human disc cellular apoptosis, senescence, and extracellular matrix catabolism with Akt and autophagy induction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 25 (12):2134–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N (2001) Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26 (17):1873–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kofoed H, Sjontoft E, Siemssen SO, Olesen HP (1985) Bone marrow circulation after osteotomy. Blood flow, pO2, pCO2, and pressure studied in dogs. Acta Orthop Scand 56 (5):400–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamada S, Kikkawa U, Tsujimoto Y, Hunter T (2005) Nuclear translocation of caspase-3 is dependent on its proteolytic activation and recognition of a substrate-like protein(s). J Biol Chem 280 (2):857–860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400538200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, Sharpless NE (2004) Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest 114 (9):1299–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA (1992) Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol 119 (3):493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. (1995) A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 (20):9363–9367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME (2002) Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418 (6894):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858nature00858[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risbud MV, Fertala J, Vresilovic EJ, Albert TJ, Shapiro IM (2005) Nucleus pulposus cells upregulate PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling pathways under hypoxic conditions and resist apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 30 (8):882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson WE, Stephan S, Roberts S (2008) The influence of serum, glucose and oxygen on intervertebral disc cell growth in vitro: implications for degenerative disc disease. Arthritis Res Ther 10 (2):R46. doi: 10.1186/ar2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, Palmer AK, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lenburg M, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF, Miller JD, Roos CM, Verzosa GC, LeBrasseur NK, Wren JD, Farr JN, Khosla S, Stout MB, McGowan SJ, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Gurkar AU, Zhao J, Colangelo D et al. (2015) The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 14 (4):644–658. doi: 10.1111/acel.12344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robles SJ, Adami GR (1998) Agents that cause DNA double strand breaks lead to p16INK4a enrichment and the premature senescence of normal fibroblasts. Oncogene 16 (9):1113–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang NC, Hu ML (2005) The limitations and validities of senescence associated-beta-galactosidase activity as an aging marker for human foreskin fibroblast Hs68 cells. Exp Gerontol 40 (10):813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.