Abstract

Life cycle theory predicts that elderly households have higher levels of wealth than households with children, but these wealth gaps are likely dynamic, responding to changes in labor market conditions, patterns of debt accumulation, and the overall economic context. Using Survey of Consumer Finances data from 1989 through 2013, we compare wealth levels between and within the two groups that make up America’s dependents: the elderly and child households (households with a resident child aged 18 or younger). Over the observed period, the absolute wealth gap between elderly and child households in the United States increased substantially, and diverging trends in wealth accumulation exacerbated preexisting between-group disparities. Widening gaps were particularly pronounced among the least-wealthy elderly and child households. Differential demographic change in marital status and racial composition by subgroup do not explain the widening gap. We also find increasing wealth inequality within child households and the rise of a “parental 1 %.” During a time of overall economic growth, the elderly have been able to maintain or increase their wealth, whereas many of the least-wealthy child households saw precipitous declines. Our findings suggest that many child households may lack sufficient assets to promote the successful flourishing of the next generation.

Keywords: Wealth, Inequality, Elderly, Children

Introduction

In his 1984 presidential address to the Population Association of America, demographer Samuel Preston called attention to what he saw as a troubling trend: the transfer of resources to the elderly at the expense of children (Preston 1984). As Preston noted, society bears responsibility for taking care of the elderly and children, who often rely on others for resources. As America’s primary dependents, however, the elderly and children often compete for resources. By prioritizing the elderly over children in the provision of public transfers, Preston argued, society risked negative consequences because subsequent generations would have insufficient resources to thrive.

More than three decades later, little has changed: the United States still directs a disproportionate amount of social welfare dollars to those over the age of 65 relative to those under the age of 18 (Moffitt 2015). The effect of these disparities in social spending on the well-being of U.S. dependent populations may be compounded by disparities in the private resources held by households. Since the 1980s, household income and wealth have become more unequally distributed across households in the United States (Wolff 2016). Although life cycle models predict that elderly households should have higher net worth than households with children (which presumably have younger household heads), the wealth gap between the young and the old is likely dynamic and may have accelerated in recent years (Boshara et al. 2015). Wealth disparities are an important predictor of long-term societal health because wealth plays a critical role in determining the civic, political, and economic life of the next generation (Pfeffer and Schoeni 2016).

Concurrent with a potential rise in wealth disparities between the elderly and child households is a likely rise in wealth inequality within child households (Yellen 2016). The same factors that other scholars have documented as fueling overall increases in wealth inequality in the United States—a top-heavy wage distribution, a skill-driven economy, and globalization (Saez and Zucman 2016)—may have had even larger effects on the wealth distribution of child households. Wealth inequality has likely also risen because child households with higher-skilled and more-educated household heads may have been able to avoid the increase in debt and decreases in home equity that have characterized households headed by individuals with less education (Wolff 2012). Rising wealth inequality among child households is of concern because wealth, above and beyond income, is associated with child development, particularly human capital acquisition (Bond Huie et al. 2003; Conley 2001; Elliott et al. 2011).

Despite the potential consequences of wealth disparities for the long-term health of society and the repercussions for the life chances of children, relatively little research has analyzed temporal changes in the wealth holdings of child households, either relative to the wealth of elderly households or within child households. To address this gap, our study provides the first over-time analysis of trends in wealth, assets, and debts for child households. We concentrate on wealth disparities between child households and elderly households (households in which the head or spouse is aged 65 or older) and on wealth inequality within child households.

Using data from nine waves of the Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF) covering the period 1989–2013, we address several research questions. First, how has the gap in wealth between elderly and child households changed over time?1 Second, how does the wealth gap between the elderly and child households vary across the wealth distribution? Third, how has wealth inequality within each of these population groups changed over time? Finally, how have changes in asset composition and debt accumulation contributed to wealth inequality between and within elderly and child households? By answering these questions, our descriptive study calls attention to an important but heretofore overlooked dimension of the increase in economic inequality: the divergence in wealth holdings of America’s dependents.

Background

Rising Wealth Inequality

Wealth inequality has risen tremendously in the United States over the past half-century.2 In 1962, the top 20 % of the wealth distribution accounted for 81 % of all wealth; by 2013, that share had risen to 89 % (Wolff 2016). Wealth inequality was relatively flat between the 1960s and early 1980s, rose steeply in the 1980s, plateaued in the 1990s and early to mid-2000s, and then increased sharply with the onset of the Great Recession. Increases in wealth inequality appear to be driven by those at the very top of the wealth distribution (the so-called 1 %). Between 1983 and 2013, the top 1 % had net worth gains of 40 %, while those in the bottom 80 % had decreases of −0.01 % (Wolff 2016).

Although likely multiply determined, increasing wealth inequality in the United States can be attributed in large part to a shifting labor market and changes in household debt patterns (Saez and Zucman 2016). The growth in globalization and the pervasiveness of a skill-based economy, coupled with the erosion of labor unions and the real value of the minimum wage, has resulted in stagnating wages for many in the bottom and middle of the income distribution but skyrocketing wages for those at the very top (Autor 2014; Autor et al. 2008). Moreover, most workers have experienced increased earnings volatility, which is partially attributable to the increase in contingent employment and irregular schedules (Dynan et al. 2012; Kalleberg 2009). Although earnings do not translate directly into wealth, households with higher employment-based earnings and less earnings volatility can direct more of their income toward asset accumulation and are less likely to deplete their wealth to pay for living or medical expenses (McGrath and Keister 2008).

Concurrent with the changes in the U.S. labor market are increases in relative indebtedness for households (Saez and Zucman 2016). Debt levels have increased nearly linearly over the past few decades; in 2013, the median debt of $60,400 was more than double the 1992 amount ($27,800) (Bricker et al. 2014). Educational debt, in particular, has risen sharply, both in breadth and depth (Houle 2014). Prior to the 2000s, Americans had been able to offset high debt levels with strong returns to their investments, mainly through increasing home equity and the rising stock market (Saez and Zucman 2016). The collapse of the housing market and the stock market crash during the late 2000s destroyed much of the market value of these goods (Wolff 2016), resulting in high levels of debt and relatively low levels of assets. Increases in debt have not been uniform across the wealth distribution but instead have risen disproportionately faster for more socioeconomically disadvantaged households (Houle 2014; Saez and Zucman 2016).

Household wealth holdings have also been affected by the onset the Great Recession, the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression. Although the mild recessions of the early 1990s and 2000s had minimal effects on wealth (Wolff 2011), the Great Recession destroyed more than $15 trillion in national wealth (Thompson and Smeeding 2012). Importantly, however, the Great Recession disproportionately affected economically vulnerable individuals, resulting in increases in wealth inequality between 2007 and 2013 (Wolff 2016). African Americans, less-educated individuals, and those with lower pre-Recession incomes saw larger relative decreases in their wealth than more socioeconomically advantaged groups (Pfeffer et al. 2013). Younger individuals were also disproportionately affected, particularly in regard to housing values. Fully 16 % of all owners under age 35 had negative home equity in 2010 compared with 3.5 % of senior citizens ages 65–74 (Wolff 2016).

Wealth Disparities Between and Within Elderly and Child Households

Household wealth in the United States exhibits a strong age gradient, with levels of net worth increasing until roughly age 65 and then declining slightly thereafter. The wealthiest households are those headed by individuals ages 65–74; the least-wealthy households are those with heads who are under age 35 (Bricker et al. 2014). Mechanically, the higher levels of net worth among older households, relative to younger households, occurs because the elderly have lower levels of debt, particularly housing debt (Wolf 2011).

The age-related pattern of wealth is consistent with the life cycle model, the typical lens used to view age differences in net worth (Ando and Modigliani 1963). In the life cycle model, expectations of future income shape individuals’ debt and asset patterns. Young adults will not save but will instead borrow against future income. Adults in middle to late middle age, at the peak of their earnings capacity, will pay down debts and accrue assets and savings at an increased pace. Older adults (typically, those older than age 65, or past the typical age of retirement) will spend down their savings to support consumption in the absence of labor market activity (Modigliani 1988). Although the life cycle model describing an inverted U-shaped pattern of savings and wealth accumulation is not without its problems—the elderly, for example, do not spend down their wealth to the degree predicted by the model (Hurd 1987)—the model has generally held to be true (Keister and Moller 2000).

Child and elderly households have not been equally affected by the factors that have increased wealth inequality among Americans more generally (Pfeffer et al. 2013). The elderly, in contrast to working-age populations, have been largely insulated from changes in the labor market. They derive most of their income from Social Security, which is indexed to keep up with inflation. The indexing of Social Security payments means that elderly incomes are largely inured to labor market volatility and are not subject to the effect of economic contractions (such as the Great Recession). Additionally, elderly households have not had the same rise in relative indebtedness that have characterized nonelderly households, in part because they are more likely to own their homes outright. Finally, elderly households completed their education before the dramatic increase in higher education costs, and thus they have lower levels of educational debt than younger Americans (Li and Goodman 2015).

Furthermore, even though the elderly lost significant wealth in the Great Recession, households headed by those over age 65 were less likely to have the characteristics of those who suffered the largest relative losses: smaller shares were headed by black or Hispanic household heads or had recently bought their first home (Pfeffer et al. 2013; Wolff et al. 2011). Boshara et al. (2015) found that over the Great Recession, households with heads over the age of 62 lost less wealth than those with younger heads. (They did not explicitly consider households with children.)

Two other factors may have contributed to the increased gap between the elderly and child households. First, changes in tax and transfer programs and social service provision are increasingly being targeted toward the elderly and away from families with children (Ben-Shalom et al. 2012; Moffitt 2015). The increasingly porous safety net for families with children suggests that these families have fewer resources available for obtaining assets or paying down debts, potentially contributing to an increased wealth gap between these two household types.

Second, child households, relative to elderly households, have grown more demographically diverse (Child Trends 2016; Shrestha and Heisler 2011) and are increasingly characterized by heads of households who face structural or institutional barriers in wealth accumulation because of their demographic characteristics (e.g., racial/ethnic minority status or unmarried). Given that these demographic shifts have been concentrated among child households but not elderly households, the wealth gap between elderly and child households has likely widened.3

Beyond a growing age-based disparity in wealth, unequal growth in within-group wealth inequality is also likely. Households headed by working-age adults, including child households, have likely seen larger increases in within-group wealth inequality because their incomes are derived primarily from labor market earnings (Larrimore et al. 2016), which have become increasingly unequal since the 1970s (Autor et al. 2008). The contemporary labor market disproportionately benefits certain types of child households (e.g., those headed by well-educated, highly skilled workers) and disadvantages others (e.g., those headed by less-educated, less-skilled workers). When coupled with the effects of the Great Recession, which disproportionately affected lower-income households (Pfeffer et al. 2013), within-child household levels of wealth inequality have likely increased. Evidence for this comes from Pfeffer and Schoeni (2016), who found more rapid increases in wealth inequality for child households than for childless households (but did not explicitly consider elderly households). The least-wealthy child households may have seen particularly large drops in wealth, further distancing their levels of wealth from child households at the very top of the distribution (Yellen 2016).

In summary, because of changing labor market conditions, increased indebtedness for some groups, and the uneven effects of the Great Recession, we anticipate that even after demographic factors are accounted for, economic disparities between elderly and child households will have grown. Moreover, we expect that increases in net worth inequality among child households will have outpaced increases in net worth inequality among elderly households. We also anticipate the least-wealthy child households may have seen particularly large declines in their wealth and will have had pronounced declines in assets (because of declines in home equity) and increases in debt (particularly educational debt).

Data

We analyzed data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a cross-sectional study of U.S. households conducted by the Federal Reserve approximately every three years. The SCF is nationally representative of United States households when weighted and includes an oversample of high-income households.4 It is considered the best source of data on household-level wealth for the United States (Keister 2014; Kennickell 2008; Wolff 2016).

Data come from the years 1989, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013. All dollar amounts were converted to 2013 dollars using the consumer price index (CPI). Across years, the total sample size was 41,528 households. Sample sizes were larger for more recent years (e.g., 3,143 in 1989; 4,305 in 1998; and 6,015 in 2013).

We focused on two household types: child households and elderly households. (Some analyses present results for all SCF households.) Child households are those with at least one resident child under age 18. Elderly households are those without children, with either the head or head’s spouse aged 65 or older. By type, the weighted sample composition was 37 % child households, 21 % elderly households, and 41 % of households falling into neither of those two categories. Over time, the sample had a slightly smaller fraction of child households (38.8 % in 1989, 35.6 % in 2013) and a slightly larger fraction of elderly households (21.1 % in 1989, 22.9 % in 2013).

Measures

Net worth measured the sum total of a family’s fungible assets minus debts. The SCF measured several categories of assets, including the values of bank deposits, stocks, financial securities, market value of the primary residence, business equity, and other miscellaneous assets not classified elsewhere. Categories of debt include amount owed on primary residence, residential and building debt for other properties, credit card debt, educational debt, installment debt, and debt not classified elsewhere. (Medical debt was not specifically assessed but was classified into installment or the “other debt” category, depending on how it was paid.) Following Wolff (2014), we excluded the value of vehicles (whose resale value is far less than the consumption value) as well as the value of future pension and Social Security income (income that the household may realize someday but does not have ready access to currently). By including only assets that are readily convertible to cash, our measure of net worth reflects a household’s current holdings.

To take into account economies of scale, we adjusted our net worth variable by the square root of household size. Results, however, were largely the same when we did not adjust for household size. On average, child households had 2.3 more members than did elderly households (see Table 1). Household size remained virtually constant over the study period for both child households and elderly households; thus, changes in household size cannot explain our results.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, child and elderly households

| Child |

Elderly |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Elderly | 1989 | 2013 | 1989 | 2013 | |

| Median Net Worth | 23,761 | 147,816 | 27,509 | 12,413 | 110,100 | 154,892 |

| Percentile Net Worth | 42.8 (26.7) |

65.1 (25.3) |

43.7 (26.8) |

42.5 (26.8) |

62.3 (26.4) |

66.8 (24.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | .65 | .84 | .68 | .57 | .83 | .79 |

| Non-Hispanic black | .15 | .09 | .15 | .17 | .11 | .10 |

| Hispanic | .13 | .03 | .12 | .14 | .04 | .05 |

| Other race/ ethnicity | .07 | .04 | .05 | .12 | .03 | .06 |

| Age | 39.7 (10.3) |

74.6 (7.3) |

38.0 (10.0) |

41.3 (11.3) |

73.6 (6.4) |

74.4 (7.8) |

| Household Structure | ||||||

| Married | .67 | .48 | .74 | .62 | .47 | .47 |

| Unmarried male | .11 | .13 | .06 | .14 | .10 | .16 |

| Unmarried female | .22 | .39 | .20 | .24 | .43 | .37 |

| Education | ||||||

| No high school | .15 | .29 | .22 | .11 | .47 | .15 |

| High school diploma | .33 | .32 | .32 | .31 | .26 | .37 |

| Some college | .25 | .17 | .23 | .26 | .11 | .21 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | .27 | .22 | .22 | .32 | .16 | .28 |

| Household Size | 3.98 (1.28) |

1.66 (0.67) |

4.09 (1.32) |

4.02 (1.30) |

1.65 (0.69) |

1.68 (0.66) |

| Number of Children in Household | 1.92 (1.02) |

– | 1.92 (1.01) |

1.92 (1.01) |

– | – |

| Income (median) | 58,308 | 31,888 | 56,567 | 55,799 | 28,283 | 36,523 |

| Sample Size | 15,376 | 8,698 | 1,139 | 2,174 | 725 | 1,317 |

Notes: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. All measures refer to the respondent unless otherwise indicated. Net worth and income are reported in constant 2013 dollars. All estimates are weighted.

For some analyses, following Pfeffer and Killewald (2015), we measured a household’s wealth as their percentile rank in a weighted net worth distribution. Using the percentile rank of wealth—rather than a log of wealth—means that all households, even those with negative wealth, can be included in one model: 20 % of the overall sample had negative net worth. Percentile net worth was calculated relative to the entire sample, including working-age households without children, for each survey year.

For covariates in the regression and decomposition models, we included the household head’s race/ethnicity, education, and household structure. Race/ethnicity was measured with four categories: non-Hispanic white (omitted category), non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other race/ethnicity. Education also consisted of four categories: no high school diploma, high school diploma (omitted category), some college, and bachelor’s degree or more. Household structure was a combination of marital status and gender, with three categories: married couple, unmarried female head, and unmarried male head.5

Descriptive statistics (Table 1) indicate that elderly households had higher levels of wealth than child households. Additionally, among child households, between 1989 and 2013, the median wealth declined by more than one-half, and the mean percentile net worth decreased by 1 percentile. Elderly households, in contrast, saw slight increases in both wealth measures. Demographically, respondents in elderly households, relative to child households, were less likely to be married (many were widows or widowers), were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, and had slightly lower levels of education. As expected, the sample became more racially and ethnically diverse over time, but increases were more pronounced for child households. Child households, but not elderly households, also saw an increase in the share of unmarried household heads. The sample also became increasingly well-educated, with sharp increases in the fraction of household heads with at least a high school diploma.6

Analysis

We began by presenting trends in net worth disparities between elderly and child households over time. To assess overall changes in wealth, we examined over-time differences in median wealth for elderly and child households. Next, because we anticipated that changes in net worth were not distributed equally throughout the wealth distribution, we compared changes in wealth for households at relative points in the distribution (the top 1 %, next 9 %, and so on). A comparison of households at relative points in the distribution directly tests our hypothesis that child households in the bottom of the wealth distribution saw the largest declines in wealth. We also used the Gini coefficient, a commonly used measure of economic inequality, to assess trends in wealth inequality within household types over time.

To better understand how disparities in wealth have grown, we regressed percentile net worth on elderly households (with child households serving as the omitted category) with the demographic covariates (race/ethnicity, education, household structure), year fixed effects, and an interaction term between elderly households and the year fixed effects. (For this analysis, we excluded households that do not include children or an elderly household head.) The interaction term between year and elderly households tests the hypothesis that percentile net worth for elderly households, relative to child households, has grown over time (with demographic characteristics controlled for).

We also used Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions to examine how changes in household head composition over time contributed to changes in the relative wealth levels for child and elderly households. We used these models to identify how much of the change in the average wealth positions of each household type (child households and elderly households) from 1989 to 2013 was attributable to changes in the demographic characteristics of household heads, changing returns to these demographic characteristics, and “unexplained” factors.

Our last set of analyses speaks to our hypothesis that structural factors—such as changing labor market context, increasing indebtedness, and fluctuating housing values—have led to increased wealth inequality. For these analyses, we examined over-time changes in variables that map onto these factors: income and earnings (for labor market context), assets and debts (for indebtedness), and homeownership and equity (for housing values). Note that income and earnings are determinants of wealth, whereas assets and debts are components of wealth; components and determinants of wealth are not equivalent concepts. Nevertheless, from a descriptive point of view, changes in components and determinants of wealth provide insight into changing trends in net worth. These analyses are descriptive, not estimates of the causal effects of these factors. Our intent with this analysis was to see whether these components and determinants of wealth changed in the expected direction.

Limitations

The SCF data have limitations. First, the SCF may understate elderly wealth inequality because the sample excludes nursing home residents (although it includes the elderly residing in assisted living facilities and other retirement communities). This exclusion cannot explain changes in the wealth gap between elderly and child households because the restriction to noninstitutionalized populations has been in place since 1989. Moreover, between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of elderly adults over age 65 residing in a nursing home fell by 21 % (West et al. 2014), suggesting that the SCF became more representative of the elderly population over time.

Another limitation is that because the SCF does not collect detailed information on public assistance receipt, we cannot examine how changes in the social safety net are associated with changes in wealth.7 Additional research is needed to explore the associations between changing patterns of public assistance and declining wealth.

Finally, pre-1989 waves of the SCF are not directly comparable with waves from 1989 onward (Kennickell 2009). The pattern of results discussed here may have originated prior to 1989 but cannot be tested with these data.

Results

Widening Wealth Gaps Between Child and Elderly Households

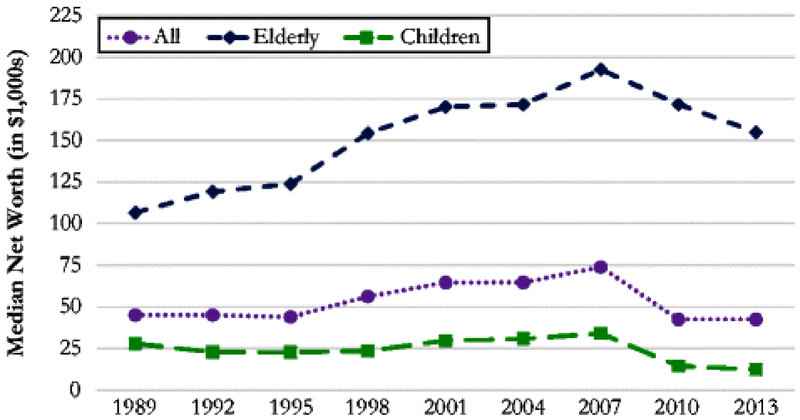

Child households, relative to elderly households, had lower levels of median net worth across the nine waves (see Fig. 1). Consistent with expectations, the relative gap in median net worth between child and elderly households widened over time. In 1989, elderly households had median net worth that was approximately 3.8 times that of child households ($106,647 vs. $27,889); by 2013, their median net worth was 12.5 times as high ($154,998 vs. $12,413). Growing disparities in net worth were evident before the onset of the Great Recession but were also magnified by it. Notably, the gap grew both because elderly households had increases in their wealth (although with a slight dip during the Great Recession) and because child households saw declines.

Fig. 1.

Median household wealth, by household type, 1989–2013. Net worth amounts are in constant 2013 dollars. Net worth was adjusted by the square root of household size. All estimates are weighted

Table 2 shows changes over time in median wealth at various points in the wealth distribution. Households were divided by their percentile of net worth, such that all households are represented in the “P0–P100” column, whereas only the top 1 % of households for each household type are represented in the “P100” column.8 Net worth was adjusted for differences in household size, and wealth distributions were calculated separately for each household type.9 We examined changes over select periods (e.g., 1989–1992, 1992–2001) to reflect years of economic growth or retraction (e.g., the recession of the early 1990s, and the economic growth of the mid- to late 1990s).

Table 2.

Median net worth for selected points in the wealth distribution, by year and household type

| Child Households |

Elderly Households |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0–P100 | P0–P50 | P51–P90 | P91–P99 | P100 | P0–P100 | P0–P50 | P51–P90 | P91–P99 | P100 | |

| Year | ||||||||||

| 1989 | 27,889 | 146 | 73,156 | 380,776 | 2,019,309 | 106,647 | 27,114 | 224,085 | 1,229,576 | 6,693,649 |

| 1992 | 22,828 | 16 | 67,956 | 428,207 | 2,268,170 | 119,095 | 37,898 | 231,212 | 955,640 | 4,954,717 |

| 2001 | 29,766 | 607 | 100,344 | 658,644 | 4,370,008 | 170,062 | 57,665 | 373,152 | 1,633,287 | 11,300,000 |

| 2004 | 30,828 | 262 | 104,270 | 660,366 | 5,347,351 | 171,653 | 45,133 | 379,438 | 1,676,785 | 10,500,000 |

| 2007 | 34,043 | 0 | 115,328 | 685,689 | 5,433,769 | 192,559 | 58,722 | 413,958 | 2,259,503 | 10,700,000 |

| 2010 | 14,489 | −148 | 56,698 | 659,236 | 5,175,390 | 171,643 | 48,494 | 363,215 | 1,977,761 | 12,200,000 |

| 2013 | 12,413 | −233 | 68,974 | 584,850 | 5,165,138 | 154,998 | 46,020 | 325,976 | 2,121,674 | 11,300,000 |

| Percentage Change | ||||||||||

| 1989–2013 | −55.5 | −259.7 | −5.7 | 53.6 | 155.8 | 45.3 | 69.7 | 45.5 | 72.6 | 68.8 |

| 1989–1992 | −18.1 | −88.9 | −7.1 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 44.8 | 90.5 | 24.8 | −9.6 | 17.7 |

| 1992–2001 | 30.4 | 3,633 | 47.7 | 53.8 | 92.7 | 42.8 | 52.2 | 61.4 | 70.9 | 128.1 |

| 2001–2004 | 3.6 | −56.9 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 22.4 | 0.9 | −21.7 | 1.7 | 2.7 | −7.1 |

| 2004–2007 | 10.4 | −100.0 | 10.6 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 12.2 | 30.1 | 9.1 | 34.8 | 1.9 |

| 2007–2010 | −57.4 | – | −50.8 | −3.9 | −4.8 | −10.9 | −17.4 | −12.3 | −12.5 | 14.0 |

| 2010–2013 | −14.3 | −57.1 | 21.6 | −11.3 | −0.2 | −9.7 | −5.1 | −10.3 | 7.3 | −7.4 |

| 2007–2013 | −63.5 | – | −40.2 | −14.7 | −4.9 | −19.5 | −21.6 | −21.3 | −6.1 | 5.6 |

Notes: Net worth amounts are in constant 2013 dollars. Net worth was adjusted by the square root of household size. All estimates are weighted.

Across all years, median wealth fell by 56 % for child households but increased by 45 % for elderly households. Child households experienced particularly large declines during the Great Recession; this economic contraction erased wealth gains in prior years. Growth in elderly household wealth was robust for the years prior to 2007, and the Great Recession had milder effects on elderly households.

The gap in median wealth between elderly and child households was growing, slowly but modestly, before the onset of the Great Recession. Notably, during the two periods of economic growth (1992–2001 and 2004–2007), median wealth increased more rapidly for elderly than for child households. In 1989, elderly households had wealth that was 3.8 times as high as that of child households; in 2004 (after the recession of the early 2000s), the difference had risen to 5.6. Thus, between 1989 and 2007—a time span that included mild recessions and economic growth—wealth disparities between the elderly and child households were rising, albeit slowly.

Disparities in wealth, however, grew tremendously with the onset of the Great Recession. Between 2007 and 2013, net worth declined by 64 % for child households but by only 20 % for elderly households. Given that child households had lower levels of net worth going into the Great Recession, their relatively bigger losses during the Great Recession aggravated the pre–Great Recession gap.

Trends in median wealth seen for child and elderly households were generally replicated across the wealth distribution, leading to a widening gap for both lower wealth and higher households. The one exception were households in the top 1 %, which saw a slight narrowing in the median wealth gap. Nevertheless, even in 2013, among the top 1 %, child households had median levels of net worth that were less than one-half as high as those of elderly households.

Despite the importance of the Great Recession in explaining wealth gaps for the overall sample, it cannot fully explain discrepancies in wealth for the least-wealthy child and elderly households. For the child households in the bottom 50 %, the Great Recession exacerbated what had already been a downward trend in median wealth: from $607 (2001) to $262 (2004) to $0 (2007). In fact, with the exception of 1992–2001, when median wealth rose for this group (from $16 to $607), the least-wealthy child households lost wealth over every period examined. In contrast, in the pre-Great Recession period, median wealth for the least-wealthy elderly households generally rose.

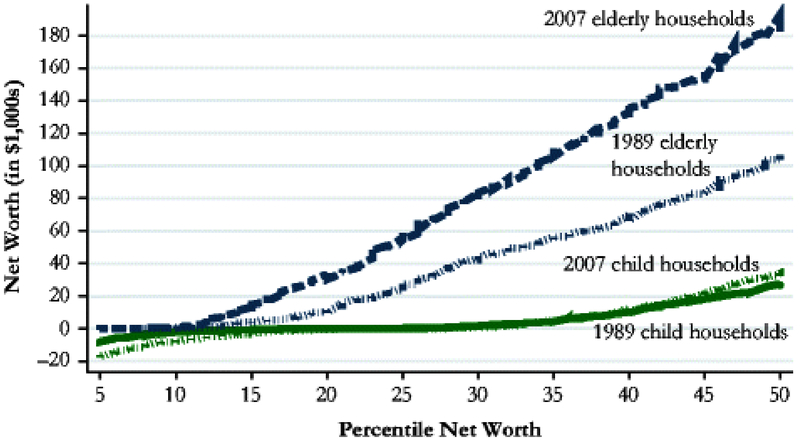

Figure 2 shows changes in the wealth holdings of the 5th through 50th percentiles of the child and elderly distributions for the years 1989 and 2007. As the figure illustrates, diverging trends in wealth among the least-wealthy households were evident before the Great Recession: in 2007, the median net worth gap between elderly and child households was $156,000, nearly double what it was in 1989.10

Fig. 2.

Net worth amounts by percentile net worth for child and elderly households, 5th through 50th percentiles

Changes in Within-Group Wealth Inequality

Child households experienced increasing within-group wealth inequality (Table 2). Gains in net worth were concentrated among the top 10 %, with the losses occurring in the bottom 50 %. Growing disparities between the top and the bottom cannot be explained fully by the Great Recession because child households in the bottom 50 % experienced declines in net worth before 2007. In contrast, child households in the top 10 % enjoyed robust growth in the 1990s and early and mid-2000s, suffering only modest losses in the late 2000s. Irrespective of the Great Recession, then, increasing disparities between the very top and the bottom occurred both because the top gained wealth while the bottom lost wealth.

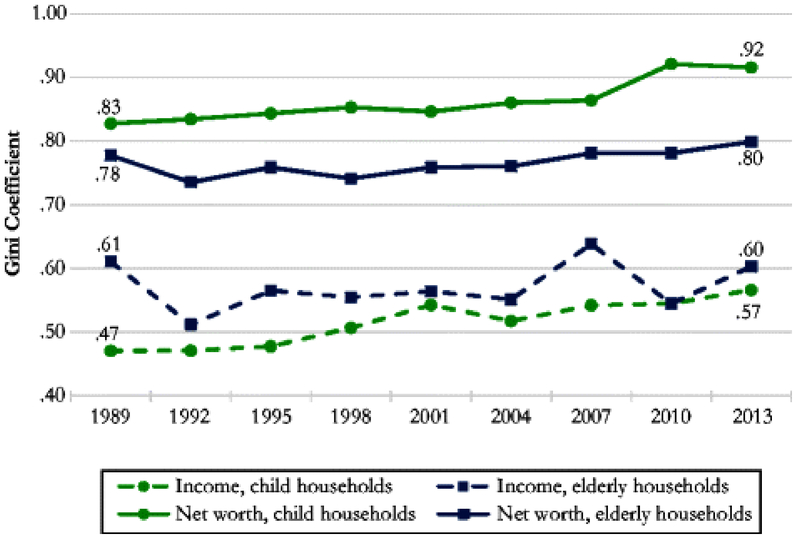

To further examine within-group inequality, we calculated Gini coefficients by household type (Fig. 3). We found that child households had substantially higher levels of within-group wealth inequality than elderly households. In 2013, the net worth Gini coefficient was .92 for child households and .80 among elderly households.11 In contrast with relatively small fluctuations over time in wealth inequality for elderly households, we found steady increases for child households. Between 1989 and 2013, the elderly experienced a very small increase in net worth inequality (Gini coefficient increased from .78 to .80). In contrast, over the same period, child households saw their net worth inequality rise by nearly 11 %, with the Gini coefficient increasing from .83 to .92.

Fig. 3.

Gini coefficients, by household type, 1989–2013

In supplementary analyses (not shown), we examined the concentration of wealth for child and elderly households. In 1989, child households in the top 1 % of the wealth distribution accounted for 31 % of net wealth; by 2013, the top 1 % accounted for 42 %. Child households in the bottom 50 % saw what little wealth they had dissipate: they accounted for 0.7 % in wealth in 1989 but had negative 1.5 % of wealth in 2013 (i.e., negative because they held more debt than assets). The distribution of wealth for elderly households, in contrast, changed very little over time, with the top 1 % accounting for 29 % of wealth and the bottom 50 % accounting for 4 % in both 1989 and 2013.

Explaining Changes in Net Worth Disparities Between Elderly and Child Households

Our next set of analyses examined average differences between child and elderly households in percentile net worth using an ordinary least squares (OLS) framework. Model 1 of Table 3 shows gaps unadjusted for demographic covariates. Elderly households were, on average, 21.7 percentile points higher in the wealth distribution than child households (p < .001). The year fixed effects suggest that child households had a fairly static average percentile net worth throughout the period. Notably, though, the net worth associated with these average positions were not constant throughout the period. The interaction terms between the year and elderly household suggest that the relative gap in percentile net worth between the elderly and child households was smaller in 1989 than in 2007, stable throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and increased during the Great Recession. In 2010, the gap between elderly households and child households was 3 percentile points larger than in 2007.

Table 3.

OLS regressions predicting percentile of net worth

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly Household | 21.7*** | (0.80) | 23.4*** | (0.72) |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref. = white) | ||||

| Black | −11.60*** | (0.41) | ||

| Hispanic | −10.70*** | (0.47) | ||

| Other race/ethnicity | −7.03*** | (0.64) | ||

| Education (ref. = high school diploma) | ||||

| No high school diploma | −7.17*** | (0.34) | ||

| Some college | 4.75*** | (0.35) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 18.00*** | (0.43) | ||

| Household Structure (ref. = married) | ||||

| Single male | −8.64*** | (0.44) | ||

| Single female | −11.09*** | (0.33) | ||

| Year (ref. = 2007) | ||||

| 1989 | 1.41 | (1.02) | 1.80* | (0.87) |

| 1992 | 0.18 | (0.92) | −0.18 | (0.85) |

| 1995 | 0.04 | (0.70) | 0.16 | (0.70) |

| 1998 | 0.28 | (0.90) | 0.17 | (0.74) |

| 2001 | 0.99 | (0.90) | 0.77 | (0.78) |

| 2004 | 0.74 | (0.77) | 0.15 | (0.66) |

| 2010 | −0.69 | (0.66) | −0.45 | (0.57) |

| 2013 | −0.02 | (0.77) | −0.04 | (0.67) |

| Year × Elderly (ref. = 2007) | ||||

| 1989 × Elderly | −3.21* | (1.53) | 0.14 | (1.42) |

| 1992 × Elderly | 0.61 | (1.28) | 3.97*** | (1.11) |

| 1995 × Elderly | 0.62 | (1.19) | 2.08 | (1.13) |

| 1998 × Elderly | 1.24 | (1.27) | 2.30* | (1.11) |

| 2001 × Elderly | −0.13 | (1.25) | 0.09 | (0.97) |

| 2004 × Elderly | −0.87 | (1.45) | −0.16 | (1.27) |

| 2010 × Elderly | 3.06** | (1.13) | 1.88* | (0.84) |

| 2013 × Elderly | 2.53* | (1.09) | 1.45 | (0.94) |

| Intercept | 42.49 | (0.55) | 44.55 | (0.58) |

| Sample Size | 24,074 | 24,074 |

Notes: All estimates are weighted. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Model 2, which includes demographic covariates, shows largely the same patterns. Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and wealth were as expected; more-disadvantaged households (as measured by racial/ethnic minority status or education level) had lower average levels of net worth. Household heads who were not married also had lower average levels of net worth. Accounting for demographic differences between elderly and child households results in a slightly larger average percentile gap (23.4 vs. 21.7) between household types. The interaction terms between elderly household and year show that wealth gaps were larger in the 1990s (compared with the reference year of 2007) and fairly stable throughout the 2000s before increasing with the onset of the Great Recession. Overall, this analysis suggests that accounting for demographic characteristics does not explain the wealth gaps between elderly and child households.

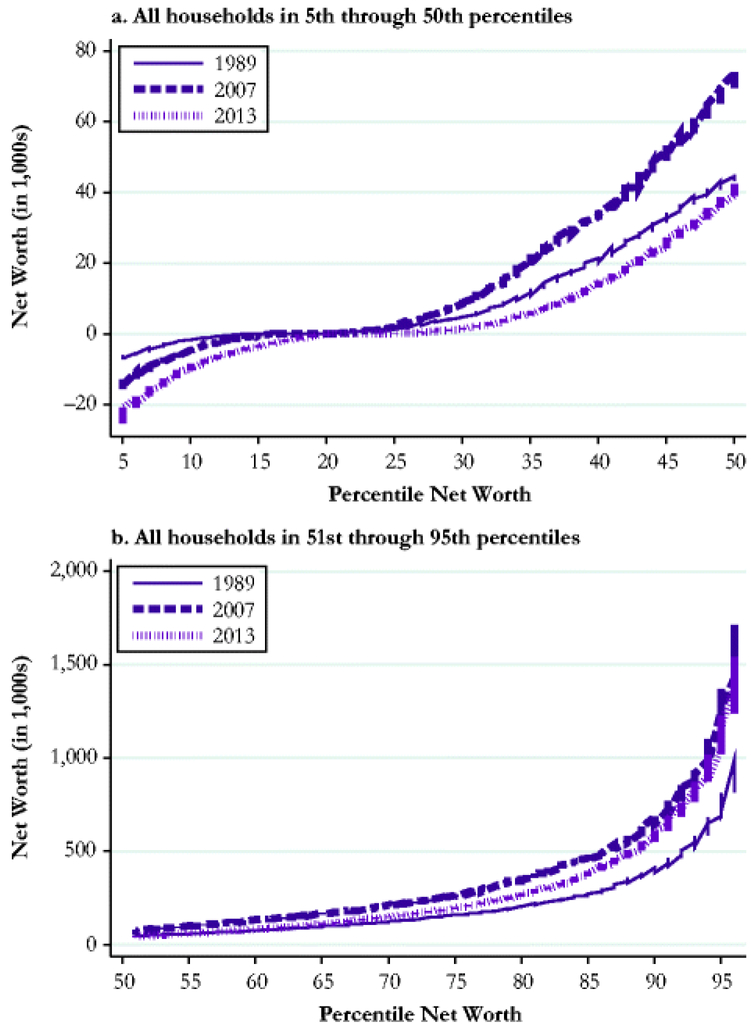

Notably, the relatively stable ranking of child households implied by the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results mask fluctuating absolute levels of wealth. Figure 4 shows the time-varying correspondence between percentile of net worth and dollar amounts of net worth. (The figure omits the tails of the distribution.) For example, the 42nd percentile, which is the average position of child households across this period, corresponded to a net worth value of $25,813 in 1989; $39,316 in 2007; and $18,165 in 2013. Thus, although the regression model shows that child households occupied a similar relative place in the overall population wealth distribution between 1989 and 2013, this corresponded with a fluctuating absolute value. The increased relative position of elderly households (as indicated by their gain of four percentiles of net worth) combined with the increased absolute value of net worth for the percentiles in the upper half of the wealth distribution (see Fig. 4, panel b), resulted in an absolute gap in net worth between elderly and child households that was smallest in 1989, and despite some fluctuations, generally increased over time.

Fig. 4.

Net worth amounts by percentile net worth, all households in the 5th through 50th percentiles (panel a) and those in the 51st through 95th percentiles (panel b)

Results thus far largely confirm our hypothesis: the absolute gap in wealth is growing between elderly and child households, in part because of the effect of the Great Recession. The Great Recession, however, does not explain the growing gap between the least-wealthy elderly and child households, who experienced opposing trends in wealth accumulation over the period from 1989 to 2007. Additionally, we found that inequality was rising faster among child households than among elderly households even before the Great Recession. Wealth increased particularly rapidly among the top 1 % of child households.

Decomposition Analysis

Our next analysis examined how shifts in demographic characteristics accounted for changes in wealth for elderly and child households. The average percentile net worth of child household decreased slightly from 43.9 in 1989 to 42.5 in 2013, but this decrease is not statistically significant (see Table 4). An Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the relative stability in the average wealth percentile of child households between 1989 and 2013 (Table 4, panel A) shows the offsetting effects of different demographic changes. The gain in predicted percentile net worth from the increasing educational attainment of household heads (2.08) was offset by the decrease in predicted percentile net worth from an increase in racial/ethnic minority household heads (−0.50) and single-parent households (−1.54), for a net effect of close to 0. Notably, for child households, the returns to education (represented by the educational coefficients) were similar in 1989 and 2013 (B = −0.41, SE = 1.30).

Table 4.

Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions: Change in average percentile net worth from 1989 to 2013 by household type

| Child Households | Elderly Households | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 Predicted Value | 42.47 | (0.57) | 66.7 | (0.67) | ||

| 1989 Predicted Value | 43.90 | (0.80) | 62.4 | (0.99) | ||

| Difference to Be Explained | −1.44 | (0.98) | 4.31*** | (1.19) | ||

| Coefficient | % of Difference |

Coefficient | % of Difference |

|||

| Explaineda | ||||||

| Total | 0.04 | (0.68) | −3 | 5.07*** | (0.93) | 118 |

| Racial/ethnic distribution | −0.50 | (0.31) | 35 | −0.19 | (0.42) | −4 |

| Household structure distribution | −1.54*** | (0.37) | 107 | −0.29 | (0.30) | −7 |

| Educational distribution | 2.08*** | (0.37) | −145 | 5.54*** | (0.70) | 129 |

| Unexplainedb | ||||||

| Total | −1.48 | (0.98) | 103 | −0.76 | (1.18) | −18 |

| Racial/ethnic coefficients | −1.16 | (0.86) | 81 | 0.29 | (0.58) | 7 |

| Household structure coefficients | 1.66* | (0.80) | −116 | 2.06* | (1.08) | 48 |

| Educational coefficients | −0.41 | (1.30) | 28 | 0.31 | (1.48) | 7 |

| Intercept | −1.57 | (1.78) | 109 | −3.41 | (2.17) | −79 |

| Sample Size | 3,313 | 2,042 | ||||

Notes: All estimates are weighted. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

Attributable to changes in characteristics.

Attributable to changes in coefficients.

p < .05;

p < .001

The household structure coefficients (part of the “unexplained” factor) changed such that the average wealth gap between married and unmarried household heads decreased slightly over time. Thus, our findings from the decomposition suggest that the story of a stable relative wealth position (and declining absolute levels of wealth) among child households cannot be attributed to increasing racial/ethnic diversity or increasing shares of single-parent households among families with children.

We also applied an Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition model to changes in the average wealth position of elderly households between 1989 and 2013. Average percentile wealth for elderly households rose by 4.3 percentiles between 1989 and 2013—a change that is statistically significant. In contrast to the results for child households, where demographic factors explained little, results for elderly households indicated that rising educational attainment accounted for most of their increased average wealth position (5.54 percentiles). Child households also experienced large gains in educational attainment (see earlier Table 1); it is unclear why education would explain such wealth gains for one group but not the other.

Changes in Assets and Debts

Our final analyses considered over-time changes in income, assets, and debts. A comparison of elderly to child households between 1989 and 2013 (Table 5, panel A) indicates that the elderly had positive increases in income, assets, homeownership, and home equity. The elderly also experienced a substantial increase in debts, from a median of $0 in 1989 to $900 in 2013. In contrast, child households had declines in income, homeownership, and home equity, as well as sizable increases in debts. Assets in child households rose by 13 %, but debts rose by far more (68 %). Because the elderly, in 1989, had higher levels of assets than child households, their relatively larger increase in assets over the observation period increased the asset disparity. The asset gap was particularly noticeable in terms of homeownership. In 1989, the share of elderly households that owned their own home was approximately 10 percentage points higher than that of child households; by 2013, the gap was 20 percentage points.

Table 5.

Change in determinants and components of wealth, 1989–2013

| Income | Assets | Debt | Homeownership | Home Equity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. All Child and Elderly Households | |||||

| Child | |||||

| 1989 | 56,567 | 114,781 | 29,915 | 64.4 | 72,303 |

| 2013 | 55,799 | 129,720 | 50,300 | 62.7 | 52,000 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | −1.4 | 13.0 | 68.1 | −2.6 | −28.1 |

| Elderly | |||||

| 1989 | 28,283 | 137,195 | 0 | 75.0 | 99,416 |

| 2013 | 36,523 | 240,500 | 900 | 83.1 | 127,000 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | 29.1 | 75.3 | — | 10.8 | 27.7 |

| B. Child and Elderly Households in the Bottom 50 % of Wealth Distribution | |||||

| Child | |||||

| 1989 | 39,597 | 21,149 | 12,291 | 44.9 | 30,729 |

| 2013 | 37,538 | 15,500 | 18,000 | 44.7 | 18,000 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | −5.2 | −26.7 | 46.4 | −0.5 | −41.4 |

| Elderly | |||||

| 1989 | 13,199 | 5,423 | 0 | 36.5 | 25,306 |

| 2013 | 18,262 | 15,080 | 1,650 | 46.2 | 27,200 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | 38.4 | 178.1 | — | 26.4 | 7.5 |

| C. Child Households, Bottom 50 % and Top 1 % | |||||

| Bottom 50 % | |||||

| 1989 | 37,711 | 21,149 | 12,291 | 44.9 | 30,729 |

| 2013 | 32,465 | 15,500 | 18,000 | 44.7 | 18,000 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | −13.9 | −26.7 | 46.4 | −0.5 | −41.4 |

| Top 1 % | |||||

| 1989 | 688,227 | 13,000,000 | 607,344 | 91.5 | 903,786 |

| 2013 | 828,872 | 17,000,000 | 375,000 | 98.6 | 1,025,000 |

| % Change 1989–2013 | 20.4 | 30.8 | −38.3 | 7.7 | 13.4 |

Notes: Dollar amounts are in constant 2013 dollars. All estimates are weighted.

Households in the bottom 50 % also had growing disparities between the elderly and child households in the determinants and components of wealth (Table 5, panel B). Between 1989 and 2013, elderly households in the bottom 50 % of the wealth distribution experienced a 38 % increase in income, a 178 % increase in assets, a 26 % increase in homeownership rates, and an 8 % increase in home equity. In contrast, child households saw decreases in income (−5 %), assets (−27 %), and home equity (−41 %), with virtually no change in homeownership rates. Child households in the bottom 50 % also saw their debt increase by 46 % from $12,291 in 1989 to $18,000 in 2013. Elderly households experienced a substantial increase in debts, but their median debt levels in 2013 were quite low at $1,650. Because assets fell and debts rose for child households, by 2013, child households in the bottom 50 % owed more in debts than they could claim in assets.

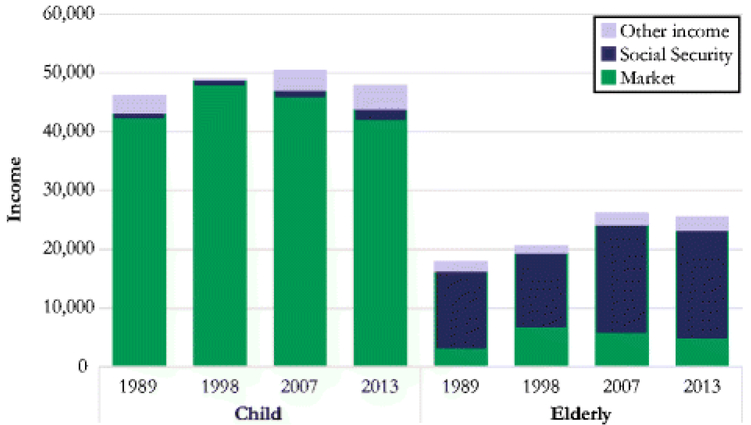

In additional analyses, we investigated the mechanical factors that accounted for the rise in income among the elderly and its decline among child households in the bottom 50 %. Following previous work (Toossi 2009), we looked at changes in Social Security and wages between 1989 and 2013 (see Fig. 5 in the appendix, which also includes other income that was neither Social Security nor wages). Among the elderly, income from Social Security rose by 40 % and from wages by 61 %. In contrast, market income—the largest income source for child households in this part of the distribution—decreased by $267, or 0.6 %. These results suggest that elderly in the bottom half of the wealth distribution have benefitted from the indexing of Social Security payments to inflation (which is partially why Social Security income rose over this time) and have been able to increase their labor market attachment. The decline in market income for child households, however, most likely speaks to the decline in wages for the less-skilled (Toossi 2009).

Comparisons of the determinants and components of wealth for the population of child households (Table 5, panel C) indicate that the top 1 % of child households enjoyed robust growth in earnings, assets, and homeownership. Conditional on owning a home, home equity increased, whereas median debt levels decreased by 38 %. Child households in the bottom 50 % experienced nearly the mirror opposite: declines in earnings, assets, home equity (if they owned homes), and increase in debts. These analyses indicate that rising indebtedness characterized only child households in the bottom half of the wealth distribution.

Supplementary analyses (not shown) indicated that the type of debt with the largest relative increase was educational debt. Between 199212 and 2013, the median amount of educational debt tripled, from $4,874 to $15,000. As a share of debt, it accounted for 14 % of all debt in 2013, up from 5 % in 1992. Credit card debt, vehicle debt, and mortgage-related debt either decreased or remained relatively flat as a proportion of debt.13

Last, we examined whether these changes occurred because of the onset of the Great Recession. We found that the relative gaps in observed components and determinants of wealth were widening between child households and elderly households and within child households prior to 2007. Child households in the bottom 50 % of the wealth distribution had modest gains in income, assets, homeownership, and home equity between 1989 and 2007. These modest gains, however, were far outpaced by gains in the same categories for elderly households, elderly households in the bottom 50 %, and child households in the top 1 %. Furthermore, child households in the bottom 50 % of the wealth distribution had large increases in debt before 2007. Thus, although the least-wealthy child households were disproportionately affected by the Great Recession, they were losing ground vis-à-vis the determinants and components of wealth before its onset.

Conclusions

Among America’s dependents, patterns of wealth accumulation over the past quarter-century have been dynamic. Consistent with recent analyses of trends in wealth accumulation by age of household head (Boshara et al. 2015), we find increasing median levels of wealth for the elderly, but decreasing median levels of wealth for child households. As a consequence, the absolute wealth gap between elderly and child households grew substantially, especially when the least-wealthy elderly households were compared with the least-wealthy child households. In contrast to the relative stability of the wealth distribution among elderly households, the wealth distribution among child households became increasingly top-heavy. Child households in the top 10 %—particularly those in the top 1 %—experienced large increases in net worth. Thus, child households experienced increases in within-group wealth inequality that far outpaced the modest increases in wealth inequality among elderly households.

Consistent with the conclusions of Saez and Zucman (2016), our results suggest that the increased wealth gap between child and elderly households was associated with changes in market income, asset accumulation patterns, and patterns of indebtedness. Elderly households enjoyed the equalizing effects of Social Security income, which increased in real value over our observation period. In contrast, child households were more reliant on market income, which has become more unequal (Saez and Zucman 2016), and median earnings for child households declined. Elderly households also increased their homeownership rate, experienced rising housing values, and maintained very low debt levels. Child households, in contrast, saw no increase in homeownership, a decrease in housing equity for those who owned homes, and a substantial increase in debt, particularly educational debt.

Our findings also suggest that rising inequality within child households occurred because of these same dynamics. The wealthiest child households saw large increases in market income, took on proportionally less debt, and had homes that increased substantially in value, whereas child households in the bottom half of the wealth distribution had large declines in market income, large increases in debt, and losses in home equity.

Other explanations for divergent wealth trends by subgroup received less support. The life cycle hypothesis, a primary explanation for wealth gaps between elderly and child households, suggests that disparities between the elderly and child households arise because the elderly have more years to save. If the hypothesis fully held, then the absolute and relative wealth gap should be relatively stable over time; the hypothesis seems insufficient given that we observed large changes in the size of the (absolute) wealth gap over a relatively short period. The growing wealth gap between elderly and child households also does not appear to have been driven primarily by growing racial and ethnic diversity among child households or by increases in the share of child households headed by single parents. Indeed, our decomposition analyses of changes in the average wealth position of child households between 1989 and 2013 suggest that demographic changes do not explain why child households experienced relative stability in their wealth position in the total population distribution and declines in their absolute levels of wealth.

The Great Recession exacerbated wealth differences between the elderly and child households and contributed to rising inequality within child households. We, like others (Pfeffer et al. 2013; Wolff 2016), found that the largest wealth losses associated with Great Recession accrued to the least-wealthy households. Notably, we showed that the Great Recession exacerbated preexisting disparities in wealth among the least-wealthy households. Although the least-wealthy elderly households enjoyed favorable economic growth before the Great Recession, the least-wealthy child households saw declines in wealth during the recessions of the early 1990s and 2000s, and also lost wealth during the mid-2000s. Thus, the Great Recession contributed to, but was not the origin of, increasing wealth disparities and inequalities over this period (see also Pfeffer and Schoeni 2016).

We found evidence of a “parental 1 %,” an extremely wealthy group of parents who can potentially dedicate high amounts of resources to their children. In 2013, the parental 1 % accounted for 42 % of all wealth among households with children and had approximately $2.5 million in wealth for each child. With Pfeffer and Schoeni (2016), we worry that the concentration of wealth among so few parents will lead to unequal access for children to the very social institutions that could mitigate wealth inequality (see also Yellen 2016). Moreover, given the rigidity of the wealth distribution—44 % of children who grow up with parents in the top wealth quintile are in the same wealth quintile as adults (Pfeffer and Killewald 2015)—our results suggest that wealth inequality will be high for the foreseeable future.

Diverging wealth trends between elderly and child households underscores Preston’s (1984) theme of decades ago: resources are not equitably distributed among America’s dependents. For the resource of household wealth, we find that some dependents (elderly in the bottom 50 %, child households in the top 1 %) are faring much better than others (children in the bottom 50 %). Substantial wealth increases among the poorest elderly Americans suggest that growing economic inequality does not have uniformly negative effects on (potentially) vulnerable populations. Our description of changes in household wealth over the period from 1989 to 2013 highlights the uneven effects of macro-level economic changes.

Previous research has shown that family wealth affects health and children’s educational attainment (Bond Huie et al. 2003; Conley 2001; Elliott et al. 2011). Given an increasingly porous social safety net for families with children (Moffitt 2015) and growth in inequality in per-pupil educational expenditures (Evans et al. 2017), the declining absolute and relative wealth holdings of most families with children is likely to impede the human capital development of the next generation of Americans. We posit that such underinvestments in children are likely to have negative long-term societal consequences for the United States.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to a grant from the National Science Foundation (#1459631) for funding this work. We also thank Leslie McCall, Ann Owens, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback.

Appendix

Fig. 5.

Income by source for the bottom 50 % of the wealth distribution, by household type and year. Income is reported in constant 2013 dollars. All estimates are weighted

Footnotes

Disparities in wealth between two groups, or a gap in wealth between groups, is conceptually distinct from levels of wealth inequality, or the dispersion of the wealth distribution.

Wealth, as a measure of stock of resources, is distinguishable from income, which measures the flow of resources. Among families with children, wealth and income are modestly correlated at .50 (Keister 2000). Wealth inequality has increased more rapidly than income inequality (Keister and Moller 2000; Wolff 2016), suggesting that trends in wealth inequality are not reducible to those for income inequality.

Two other demographic factors—educational attainment and age—have also shifted over time, as the United States population has become more educated and older (Mather et al. 2015; Ryan and Bauman 2016). Increased educational attainment is evident for both child and elderly households, and therefore is unlikely to contribute to widening gaps between the groups. Increased age among the elderly might downwardly bias gaps if, over time, a larger share of elderly households were in an age range where they were rapidly spending down their assets. The age of household heads for elderly households in our sample increased by only one year between 1989 and 2013, with a similar standard deviation (see Table 1).

The SCF describes itself as a sample of “families,” but its definition of family (people at the same address sharing living quarters) is more akin to the U.S. Census definition of households. Following Wolff (2014), we discuss our unit of analysis as households.

Cohabiting households with an unmarried man and unmarried woman were classified in the unmarried male head category because the SCF classified all households with a different-sex couple as male-headed.

SCF estimates of educational attainment were quite similar to Current Population Survey (CPS) estimates in the same years (results not shown).

We investigated using the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for this purpose, but SIPP estimates of wealth were inconsistent with SCF estimates and did not seem credible.

Estimating household median wealth at different points in the distribution is akin to estimating median wealth at the midpoint of that distribution: for example, household median wealth in the bottom 50 % is the average of the median wealth for households at the 25th and 26th percentile.

When all households were compared across time (available upon request), median net worth fell by 5.8 %. Households in the bottom 50 % had declines of 87 %, whereas those in the top 1 % had increases of 82 %.

In additional analyses, we divided households into the 0th–25th percentiles and the 26th–50th percentiles. Our main conclusions regarding the gap between elderly and child households remained the same. Notably, child households in both quartiles lost economic ground to elderly households in similar distributional positions between 1989 and 2013.

These net worth Gini coefficients may seem implausibly high, but they were consistent with other SCF-based estimates of net worth inequality (e.g., Keister 2014; Wolff 2016).

Information on types of debt were not collected in 1989.

Home debt rose in the mid-2000s but then fell to 1990s levels after the Great Recession.

References

- Ando A, & Modigliani F (1963). The “life cycle” hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. American Economic Review, 53, 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Autor DH (2014). Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the other 99 percent. Science, 344, 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autor DH, Katz LF, & Kearney MS (2008). Trends in U.S. wage inequality: Revising the revisionists. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 300–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shalom Y, Moffitt RA, & Scholz JK (2012). An assessment of the effectiveness of anti-poverty programs in the United States In Jefferson PN (Ed.), Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 709–749). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bond Huie SA, Krueger PM, Rogers RG, & Hummer RA (2003). Wealth, race, and mortality. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Boshara R, Emmons WR, & Noeth B (2015). The demographics of wealth: How age, education and race separate thrivers from strugglers in today’s economy (Demographics of Wealth Essay No. 1). St. Louis, MO: Center for Household Financial Stability at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J, Dettling LJ, Henriques A, Hsu JW, Moore KB, Sabelhaus J, … Windle RA (2014). Changes in U.S. family finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 100(4), 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. (2016). Racial and ethnic composition of the child population (Report). Washington, DC: Child Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Conley D (2001). Capital for college: Parental assets and postsecondary schooling. Sociology of Education, 74, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dynan K, Elmendorf D, & Sichel D (2012). The evolution of household income volatility. BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 12(2), 1–42. 10.1515/1935-1682.3347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott W III, Destin M, & Friedline T (2011). Taking stock of ten years of research on the relationship between assets and children's educational outcomes: Implications for theory, policy and intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2312–2328. [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, Schwab RM, & Wagner KL (2017). The Great Recession and public education. Education Finance and Policy. Advance online publication. 10.1162/edfp_a_00245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JN (2014). A generation indebted: Young adult debt across three cohorts. Social Problems, 61, 448465. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd MD (1987). Savings of the elderly and desired bequests. American Economic Review, 77, 298–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg AL (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Keister LA (2014). The one percent. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Keister LA, & Moller S (2000). Wealth inequality in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kennickell AB (2008). The role of over-sampling of the wealthy in the Survey of Consumer Finances. Irving Fisher Committee Bulletin, 28, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kennickell AB (2009). Ponds and streams: Wealth and income in the U.S., 1989 to 2007 (Finance and Economics Discussion Series No. 2009-13). Washington, DC: Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board. [Google Scholar]

- Larrimore J, Dodini S, & Thomas L (2016). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2015. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, & Goodman L (2015). Americans’ debt styles by age and over time (Report). Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Jacobsen LA, & Pollard KM (2015). Aging in the United States. Population Bulletin, 70(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath DM, & Keister LA (2008). The effect of temporary employment on asset accumulation processes. Work and Occupations, 35, 196–222. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani F (1988). The role of intergenerational transfers and life cycle saving in the accumulation of wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(2), 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt RA (2015). The deserving poor, the family, and the U.S. welfare system. Demography 52, 729–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer FT, Danziger S, & Schoeni RF (2013). Wealth disparities before and after the Great Recession. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650, 98–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer FT, & Killewald A (2015). How rigid is the wealth structure and why? Inter-and multi-generational associations in family wealth (PSR Reports No. 15-845). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer FT, & Schoeni RF (2016). How wealth inequality shapes our future. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 2–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH (1984). Children and the elderly: Divergent paths for America’s dependents. Demography 21, 435–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CL, & Bauman K (2016). Educational attainment in the United States: 2015 (Current Population Reports No. P20-578). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Saez E, & Zucman G (2016). Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131, 519–578. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha LB, & Heisler EJ (2011). The changing demographic profile of the United States (CRS Report for Congress, No. RL32701). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, & Smeeding TM (2012). Country case study—USA In Jenkins SP, Brandolini A, Micklewright J, & Nolan B (Eds.), The Great Recession and the distribution of household income (pp. 201–233). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toossi M (2009). Labor force projections to 2018: Older workers staying more active. Monthly Labor Review, 132, 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- West LA, Cole SD, Goodkind D, & He W (2014). 65+ in the United States: 2010 (Current Population Reports No. P23-212). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff EN (2011). Recent trends in household wealth, 1983–2009: The irresistible rise of household debt. Review of Economics and Institutions, 2(1), 1–31. 10.5202/rei.v2i1.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff EN (2012). The asset price meltdown and the wealth of the middle class (NBER Working Paper No. 18559). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff EN (2016). Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962 to 2013: What happened over the Great Recession? Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff EN, Owens LA, & Burak E (2011). Howmuchwealth was destroyedduringthe Great Recession? In Grusky DB, Wester B, & Wimer C (Eds.), The Great Recession (pp. 127–158). New York, NY: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yellen JL (2016). Perspectives on inequality and opportunity from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(2), 44–59.30123834 [Google Scholar]