Abstract

Background and Purpose

Despite modest predictive ability for ischemic stroke (IS), the CHA2DS2-VASc score is widely used for stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation (AF). Among AF patients, we aimed to (1) Compare the IS or transient ischemic attack (TIA) incidence by CHA2DS2-VASc in blacks and Hispanics vs. whites; (2) Compare predictive ability of CHA2DS2-VASc score for IS or TIA in blacks and Hispanics vs. whites; (3) Determine improvement in predictive ability of CHA2DS2-VASc score from addition of race/ethnicity.

Methods

Using data from Optum Clinformatics®, a large administrative claims database, we analyzed AF patients enrolled in commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans 2009–2015. We computed IS or TIA incidence rates, improvement in C-statistic, continuous and categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI), and relative integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) from addition of race/ethnicity to CHA2DS2-VASc.

Results

A total of 267,419 patients (mean age, 73.1 [SD, 12.3] years; 46.6% women; 84.2% white, 8.5% black, 7.3% Hispanic) were studied. After a mean follow-up of 22 months, there were 6,202 IS or TIA events. IS or TIA incidence rates were higher in blacks than Hispanics or whites (1.65, 1.40 and 1.22 cases per 100 person-years, respectively) and increased with higher CHA2DS2-VASc, with no race/ethnicity-based differences (P for interaction=0.17). The CHA2DS2-VASc and CHA2DS2-VASc + race/ethnicity C-statistic (95% CI) were 0.679 (0.670–0.686) and 0.679 (0.671–0.688). The CHA2DS2-VASc C-statistic in the 3 groups were comparable. With addition of race/ethnicity, the categorical NRI, continuous NRI, and relative IDI were −0.045 (95% CI, −0.067 to −0.025), 0.045 (95% CI, 0.025 to 0.068), and 0.016 (95% CI, 0.014 to 0.018).

Conclusions

The predictive ability of CHA2DS2-VASc for IS or TIA in AF is comparable among whites, blacks, and Hispanics; hence, it can be used in the latter 2 groups. Addition of race/ethnicity to the CHA2DS2-VASc does not improve its predictive ability.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, ischemic stroke, race, risk prediction, Atrial fibrillation, ischemic stroke, risk factors, race and ethnicity

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic stroke.1 Current practice guidelines recommend risk stratification with the CHA2DS2-VASc score to identify appropriate candidates for systemic anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic stroke.2, 3 Although widely used and recommended by current practice guidelines, the CHA2DS2-VASc score has modest discriminatory capacity for ischemic stroke in patients with AF: In a meta-analysis of 8 clinical studies, the C-statistic of the CHA2DS2-VASc score was only 0.675.4 Identification of novel factors that can improve the performance of the CHA2DS2-VASc score may refine our ability to prevent AF-related stroke.

Race is one potential such factor. Several studies have reported that patients with AF of African ancestry have higher risk of stroke compared with whites.5–9 In fact, a recent paper—based on Medicare claims data—concluded that addition of African-American race to the CHA2DS2-VASc score improves stroke prediction in AF patients.10 However, this study was restricted only to patients aged >65 years. Further, given limited data on this issue, more evidence from other independent cohorts is needed.

To address the aforementioned knowledge gaps, our study had 3 aims: (1) Compare the incidence rates of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) by CHA2DS2-VASc score in blacks and Hispanics vs. whites, (2) Compare the model discrimination of CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA in blacks and Hispanics vs. whites, and (3) Determine the improvement in risk classification of the CHA2DS2-VASc score from addition of race/ethnicity information. We evaluated our aims in Optum Clinformatics—a large administrative claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage health plan enrollees.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Optum, Inc.

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data from Optum Clinformatics®, which includes privately insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees throughout the United States.11 Approximately 17.5 million patients were enrolled per year during the analysis period between 2009 and 2015. This database includes enrollees from geographically diverse regions across the USA; thus, it is representative of the USA population with commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans. The database provides data on inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, laboratory, and pharmacy claims with linked enrollment information. Medical claims include International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes; ICD-9 procedure codes; Current Procedural Terminology, Version 4 (CPT-4) procedure codes; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System procedure codes; and site of service codes. Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Minnesota institutional review board. Informed consent was not obtained from patients since this study involved analysis of de-identified administrative claims data

Study Population

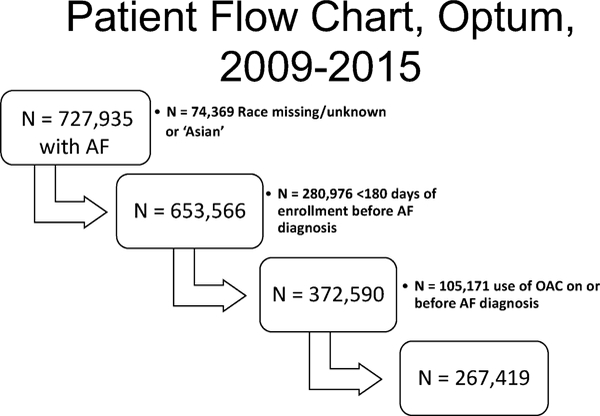

We identified 727,935 patients enrolled in Optum Clinformatics® between 2009 and 2015 with 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims for AF (ICD-9-CM 427.3, 427.31, and 427.32, in any position). The 2 outpatient AF diagnoses had to be at least 1 week apart and less than 1 year apart. After excluding patients with missing race information (n=60,538) or Asian race because of small numbers (n=13,831), patients with <180 days of enrollment before AF diagnosis (n=280,976), and those who were using an oral anticoagulant on or before AF diagnosis (n=105,171), 267,419 patients remained for analysis. A flow diagram of the study population is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram of participants, OAC=oral anticoagulant

Ascertainment of Ischemic Stroke and TIA

Our primary outcome was a composite of ischemic stroke and TIA. Ischemic stroke and TIA were ascertained using discharge diagnoses (first position only) from acute hospitalizations for ischemic stroke and TIA. Ischemic stroke was identified by ICD-9 codes 433.x1, 434 (excluding 434.x0), and 436. TIA was identified by ICD-9 code 435.

Ascertainment of Race and Ethnicity

We considered 3 race/ethnicity groups: whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Approximately 30% of the race/ethnicity data in this study were collected directly from public records (e.g., driver’s license records), while the remaining data were imputed using commercial software (E-Tech by Ethnic Technologies) that uses algorithms developed with USA Census data zip codes (zip + 4) and first and last names. This imputation method has been validated and demonstrates 97% specificity, 48% sensitivity, and 71% positive predictive value for estimating the race of black individuals.12

Covariates

The variables in the CHA2DS2-VASc score—congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, stroke or TIA, complicated vascular disease (myocardial infarction or peripheral arterial disease)—were defined based on the presence of relevant diagnostic codes in any position on any outpatient or inpatient claim prior to the diagnosis of AF. The CHA2DS2-VASc is calculated based on the presence of heart failure (1 point), hypertension (1 point), age ≥75 years (2 points), age 65–74 (1 point), diabetes (1 point), previous stroke or TIA (2 points), female sex (1 point), and vascular disease (1 point). Date of first oral anticoagulant use following AF was obtained from outpatient pharmacy claims. Please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org Table I for details on ICD-9 codes for covariates.

Statistical Analysis

We report means with standard deviations (SDs) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables.

We grouped patients into the following CHA2DS2-VASc score categories: 0–1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7–9. We computed the incidence rates of ischemic stroke or TIA, stratified by race/ethnicity and CHA2DS2-VASc score categories. We also computed the Negative Predictive Value (NPV), Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and odds ratio (95% confidence interval [CI]) of CHA2DS2-VASc 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 for ischemic stroke or TIA, not censoring and censoring for initiation of oral anticoagulation. To evaluate model discrimination of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA based on race/ethnicity, we computed the 1-year C-statistic, stratified by race/ethnicity. We also added a race/ethnicity variable (non-Hispanic whites, blacks, and Hispanic whites) to the CHA2DS2-VASc score to determine whether adding a race/ethnicity variable would improve model discrimination. Further, we added interaction terms (race/ethnicity*CHA2DS2-VASc variables) and computed the C-statistic to determine improvement in model discrimination.

To assess improvement in risk classification by considering race/ethnicity, we added the race/ethnicity variable (whites, blacks, and Hispanics) to the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and calculated the continuous and categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI) and relative integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). IDI assesses reclassification as a continuous outcome across the range of risk; no improvement in predicted risk is denoted by a value of zero. Specifically, relative IDI is the ratio of absolute difference in discrimination slopes of the 2 models over the discrimination slope of the model without the additional variable of interest. By contrast, NRI assesses changes between defined risk categories; in this study, for categorical NRI, we evaluated clinically relevant 1-year risk categories: <1%, 1% to <2%, ≥2%. Detailed formulas for these statistics are provided elsewhere.13 Of note, in all the aforementioned analyses, we censored patients at the time of database disenrollment.

We performed 3 sensitivity analyses. First, since the validity of ICD-9 code 435 (TIA) is less robust, we repeated our analyses excluding TIA from our outcome definition. Second, we repeated our analyses censoring patients who started oral anticoagulants at the time of the first oral anticoagulant prescription. Third, to evaluate non-gender stroke risk factors, we categorized patients into the following groups: Group1: low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc = 0 in male and 1 in female; Group 2: 1 non-gender risk factor, CHA2DS2-VASc = 1 in male and 2 in females; Group 3: 2 non-gender risk factors, CHA2DS2-VASc = 2 in male and 3 in female, and so on.

Finally, since race/ethnicity information was algorithmically imputed for two-thirds of the sample, we conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis14 to correct for race/ethnicity misclassification and random error simultaneously. Using sensitivity and specificity data of the imputed algorithm to predict black or white race from DeFrank et al.,12 we ran 1000 iterations of the simulation that reclassifies race/ethnicity and computed the conventional OR (crude odds ratio of stroke when race is misclassified), systematic OR (OR corrected for race misclassification), and total error OR (OR corrected for race misclassification and random error) for risk of stroke in blacks vs. whites.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All P values reported were 2-sided, and the statistical significance threshold was chosen as 5%.

Results

Study Population

The analysis sample consisted of 267,419 patients (mean age, 73.1 [SD, 12.3] years; 46.6% women; 84.2% white, 8.5% black, 7.3% Hispanic). The mean age and sex distribution were not significantly different among the 3 race/ethnic groups. Compared with whites, the mean CHA2DS2-VASc score and prevalence of its individual components were higher in blacks and Hispanics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Atrial Fibrillation Patients in Study, Optum Clinformatics, 2009–2015

| All | Whites | Blacks | Hispanics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 267,419 | 225,116 | 22,808 | 19,495 |

| Age, years | 73.1 (12.3) | 73.2 (12.1) | 71.2 (13.0) | 73.4 (12.9) |

| Women, % | 46.6 | 46.0 | 51.0 | 47.6 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.5 (2.1) |

| Heart failure, % | 32.7 | 31.5 | 40.5 | 38.1 |

| Hypertension, % | 82.3 | 81.3 | 88.3 | 86.6 |

| Diabetes, % | 33.9 | 31.8 | 43.6 | 47.3 |

| Ischemic stroke, % | 26.7 | 26.2 | 29.9 | 29.3 |

| Vascular disease, % | 31.9 | 31.1 | 34.5 | 38.2 |

| Income, %* | ||||

| <$40K | 39.5 | 37.5 | 54.8 | 45.6 |

| $40K-$49K | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 10.8 |

| $50K-$59K | 8.7 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 9.3 |

| $60K-$74K | 10.2 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 10.1 |

| $75K-$99K | 12.0 | 12.4 | 8.3 | 10.9 |

| $100K+ | 19.7 | 21.4 | 8.5 | 13.4 |

| Education, %** | ||||

| < 12th Grade | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 5.2 |

| High School Diploma | 30.4 | 26.8 | 54.1 | 43.8 |

| < Bachelor Degree | 56.0 | 58.5 | 41.6 | 43.5 |

| Bachelor Degree or more | 13.0 | 14.5 | 3.8 | 7.5 |

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation unless otherwise stated.

Based on 198,666 whites, 19,925 blacks, and 16,609 Hispanics

Based on 224,502 whites, 22,782 blacks, and 19,435 Hispanics

Incidence of Ischemic Stroke or TIA by Race/Ethnicity

After a mean follow-up of 22 months, there were 6,202 ischemic stroke or TIA events. Table 2 shows the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA, stratified by race. The overall incidence rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.24–1.30) per 100 person-years. Compared with whites, the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA was higher in blacks and Hispanics. In a sensitivity analysis excluding TIA from the outcome, the incidence rate of ischemic stroke was 1.03 (95% CI, 1.00–1.06) per 100 person-years. Similarly, we observed a lower incidence of ischemic stroke among whites compared with blacks and Hispanics (Table 2). Notably, the hazard ratio of blacks and Hispanics for ischemic stroke or TIA (whites as referent category) remained essentially unchanged after adjustment for CHA2DS2-VASc variables, income, and educational level. Figure I and II in the online supplement show the race/ethnicity–stratified Kaplan-Meier curves for ischemic stroke and TIA and ischemic stroke, respectively. In another sensitivity analysis when we censored patients at the time of oral anticoagulant initiation, the overall incidence rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was higher at 1.32 (95% CI, 1.28–1.35) per 100 person-years (please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org for Table II). Again, compared with whites, the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA was higher in blacks and Hispanics.

Table 2.

Incidence and Hazard Ratios of Ischemic Stroke or TIA Among Atrial Fibrillation Patients, Stratified by Race/Ethnicity, Optum Clinformatics, 2009–2015

| All | Whites | Blacks | Hispanics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic stroke or TIA, N | 6,202 | 5,069 | 617 | 516 |

| Person-years | 489,453 | 415,308 | 37,398 | 36,747 |

| Incidence rate* | 1.27 (1.24, 1.30) | 1.22 (1.19, 1.25) | 1.65 (1.52, 1.78) | 1.40 (1.29, 1.53) |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | - | Referent | 1.33 (1.22, 1.44) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)† | - | Referent | 1.31 (1.19, 1.43) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Ischemic stroke, N | 5,045 | 4,104 | 519 | 422 |

| Person-years | 491,416 | 416,975 | 37,543 | 36,897 |

| Incidence rate* | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 1.38 (1.27, 1.51) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.26) |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | - | Referent | 1.38 (1.26, 1.51) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)† | - | Referent | 1.38 (1.25, 1.53) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.22) |

Per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval)

Adjusted for CHA2DS2-VASc variables: congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, stroke or TIA, complicated vascular disease (myocardial infarction or peripheral arterial disease), sex category, income, and educational level

We conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (OR simulation results, n=1,000) to correct for potential race misclassification and random error. The analysis yielded the following median OR (2.5th to 97.5th percentile) for risk of stroke in blacks vs. whites: conventional OR, 1.13 (1.03–1.22); systematic OR, 1.30 (1.23–1.38); and total OR, 1.30 (1.17–1.44). Therefore, correction for potential race misclassification and random error increased the strength of the association between race and stroke risk.

Incidence of Ischemic Stroke or TIA by Race/Ethnicity and CHA2DS2-VASc Score

The NPV, PPV, and odds ratio (95% CI) of CHA2DS2-VASc 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 for ischemic stroke or TIA are shown in the online supplement Tables III and IV. Figure 2 shows the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA by CHA2DS2-VASc score stratified by race/ethnicity. In all 3 race/ethnicity groups, the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA increased monotonically from approximately 0.2 per 100 person-years in CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0–1 to 2.5–3.3 per 100 person-years in CHA2DS2-VASc category of 7–9. The relationship of the CHA2DS2-VASc score to incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA did not differ by race/ethnicity (P for interaction=0.17). A similar pattern was observed when we performed a sensitivity analysis that censored patients at the time of oral anticoagulant initiation (please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org for Figure III) and when we evaluated non-gender stroke risk factors (please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org for Figure IV).

Figure 2.

Incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA among patients with atrial fibrillation, stratified by CHA2DS2-VASc score and race/ethnicity (without censoring for oral anticoagulant)

Model Discrimination and Risk Classification of CHA2DS2-VASc Score for Ischemic Stroke or TIA by Race/Ethnicity

In the whole sample, the C-statistic of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for 1-year risk of ischemic stroke or TIA was 0.679 (95% CI, 0.670–0.686) (Table 3). Addition of a race/ethnicity variable did not change the C-statistic. Further, addition of interaction terms (race/ethnicity*CHA2DS2-VASc variables) did not improve model discrimination (please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org for Table V). Model performance of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA was comparable in all 3 race/ethnicity groups ranging from 0.649 (95% CI, 0.620–0.679) in Hispanics to 0.682 (95% CI, 0.658–0.706) in blacks.

Table 3.

C-statistic of CHA2DS2-VASc for 1-Year Prediction of Ischemic Stroke or TIA Among Atrial Fibrillation Patients, Optum Clinformatics, 2009–2015

| C-statistic | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 0.679 | 0.670, 0.686 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score + race/ethnicity | 0.679 | 0.671, 0.688 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score in models stratified by race/ethnicity | ||

| Whites | 0.678 | 0.669, 0.688 |

| Blacks | 0.682 | 0.658, 0.706 |

| Hispanics | 0.649 | 0.620, 0.679 |

CI, confidence interval

Similarly, the categorical NRI of −0.045 (95% CI, −0.067 to −0.025) indicates that addition of a race/ethnicity variable did not improve risk classification of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA (Table 4). The proportion of ischemic stroke or TIA events that was correctly reclassified was −0.028 and proportion of ischemic stroke or TIA non-events that was correctly reclassified was −0.016. The continuous NRI of 0.045 (95% CI, 0.025 to 0.068) and relative IDI of 0.016 (95% CI, 0.014 to 0.018) indicate that any improvement in risk classification was only marginal.

Table 4.

Categorical Net Reclassification Improvement of CHA2DS2-VASc Score for Ischemic Stroke or TIA Among Atrial Fibrillation Patients with Addition of Race/Ethnicity. Optum Clinformatics, 2009–2015

| Events | Non-events | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post | Post | ||||||||

| Pre | <1% | 1 to 2% | ≥2% | Total | Pre | <1% | 1 to 2% | ≥2% | Total |

| <1% | 2526 | 33 | 0 | 2559 | 0 to 1% | 133795 | 2886 | 0 | 136681 |

| 1 to 2% | 104 | 972 | 22 | 1098 | 1 to 2% | 782 | 78031 | 2719 | 81532 |

| ≥2% | 0 | 50 | 287 | 337 | ≥2% | 0 | 604 | 44608 | 45212 |

| Total | 2630 | 1055 | 309 | 3394 | Total | 134577 | 81521 | 47327 | 263425 |

Categorical NRI (1-year risk categories: <1%, 1 to <2%, ≥2%) = −0.0445 (95% Cl −0.0666, −0.0254)

Proportion of events correctly reclassified (blue print): −0.0284

Proportion of non-events correctly reclassified (red print): −0.0161

Discussion

Our study—based on a large administrative claims database—has 3 major findings: (1) As the CHA2DS2-VASc increased, there was similar relative increase in ischemic stroke or TIA risk by race/ethnicity, (2) Model discrimination of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA was comparable in all 3 race/ethnicity groups, and (3) Addition of race/ethnicity information did not improve prediction of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA. Our results were robust to 2 sensitivity analyses which excluded TIA from the outcome or censored patients who initiated oral anticoagulants during follow-up. Collectively, our findings suggest that despite its limitations and until we have a better instrument, the CHA2DS2-VASc score should be used to stratify the risk of AF-related ischemic stroke in blacks and Hispanic whites. Our findings also indicate that notwithstanding race-based differences in the risk of AF-related ischemic stroke, considering race/ethnicity information does not improve stroke prediction of the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Since the original publication of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in 2010,15 this risk prediction scheme has been adopted worldwide and endorsed by practice guidelines to stratify ischemic stroke risk in patients with AF.2, 3 The global adoption of the CHA2DS2-VASc score has occurred despite the fact that its predictive ability for stroke is only modest. Recent data from the Chinese population (Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database) suggest that a modified CHA2DS2-VASc (where age 50–74 years counts as 1 point) is better than the CHA2DS2-VASc (where age 65–74 years counts as 1 point) in predicting ischemic stroke.16 The CHA2DS2-VASc score is also purported to have greater ability than the older CHADS2 score at identifying patients with AF who are at low risk of ischemic stroke. More recent studies, however, have found the absolute risks in these “low-risk” groups to be higher: Chao TF et al. reported from a health claims database that the incidence rates of stroke were 1.15 and 2.11 per 100 person-years for CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 0 and 1, respectively.16 Another study reported an annual stroke risk of 1.06% for CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 and 1.72% for CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1.17 Further, a recent paper reported substantial variation across cohorts in overall stroke rates corresponding to CHA2DS2-VASc point scores.18 In aggregate, subsequent studies after 2010 suggest that the CHA2DS2-VASc score, despite its widespread use, has only modest predictive ability for ischemic stroke.

Several studies have indicated that black race may be an independent risk factor for stroke in AF patients.5–9 A study using Medicare data showed that the risk of stroke was higher in blacks (29.3 per 1,000 patient-years) versus whites (14.8 per 1,000 patient-years).19 Another study showed that after adjustment for pre-existing comorbidities and anticoagulation status, blacks had a 46% higher risk of ischemic stroke compared with whites.20 These data raise two tantalizing questions: First, whether the CHA2DS2-VASc score can be used to predict risk of AF-related ischemic stroke in blacks; and second, whether considering black race would refine prediction of ischemic stroke. Kabra et al. addressed these questions by conducting a retrospective analysis using Medicare claims data and found that the incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with AF was higher in African-American patients than in non-African-American patients.10 There was, however, no interaction between the CHA2DS2-VASc score and race/ethnicity, i.e., the relative increase in stroke risk by race/ethnicity as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increases was similar. Further, they found that adding African-American race to the CHA2DS2-VASc score did not improve model discrimination (C-statistic increased marginally from 0.60 to 0.61). Although the continuous NRI was 7.6% the integrated discrimination improvement was only 1.2%; categorical NRI was not reported.10

Our report advances knowledge on this topic on several fronts: (1) By not restricting to patients aged >65 years (who already have 1 stroke risk factor based on age), we are able to evaluate the performance of the CHA2DS2-VASc across a broader age range and health status, (2) By computing categorical NRI using clinically meaningful cutoffs—rather than only continuous NRI—we can evaluate whether addition of race/ethnicity would translate to a meaningful change in clinical management. Consistent with the study by Kabra et al.,10 we found that the incidence of ischemic stroke or TIA was higher in blacks compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Similarly, we observed that adding a race/ethnicity variable did not improve model discrimination of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Most importantly, although we noted a similar continuous NRI (4.5%), our categorical NRI was not clinically significant (−4.5%).

Several limitations should be noted. First, the study is based on administrative data that are susceptible to under- or overcoding and lack the outcome and diagnosis validation in clinical trials and registries. On the other hand, an administrative claims database more closely resembles a real-world patient population than a clinical trial, which typically enrolls highly selected patients. Second, race/ethnicity data were imputed in approximately two-thirds of patients. This imputation method, however, had 97% specificity and 71% positive predictive value for estimating the race of black individuals.12 However, data on positive predictive value for Hispanic patients were not available. Furthermore, approximately 8% of the total patient population were excluded due to unknown race/ethnicity information because race/ethnicity could not be assigned by the imputation algorithm or they were added to the data set after the imputation had been performed. Our bias analysis correcting for potential race/ethnicity misclassification increased the strength of the association between race/ethnicity and stroke risk. Therefore, future studies with more valid race/ethnicity information should be conducted. Third, because of small numbers, we were not able to evaluate Asians or Pacific Islanders. Finally, data to support an increased risk of stroke in blacks with AF compared with whites are observational5–9 and there are no clearly defined biological explanations or mechanisms. Therefore, more research is needed before we consider recommending anticoagulation therapy based on race/ethnicity information.

Summary

Our report—based on a large administrative claims database—provides evidence that the predictive ability of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke or TIA in patients with AF is comparable among whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Thus, until we have a more refined instrument than the CHA2DS2-VASc score, the latter should be used to stratify the risk of AF-related ischemic stroke in blacks and Hispanics. Since adding race/ethnicity variable to the CHA2DS2-VASc score does not improve stroke prediction, the quest to identify novel factors that will improve stroke prediction continues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by R01-HL122200 (Alonso). Dr. Chen is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL126637 and R01HL141288). Dr. Alonso is supported by the American Heart Association (16EIA26410001).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Bengtson is an employee of Optum.

References

- 1.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr., et al. 2014 aha/acc/hrs guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 esc guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with eacts. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JY, Zhang AD, Lu HY, Guo J, Wang FF, Li ZC. Chads2 versus cha2ds2-vasc score in assessing the stroke and thromboembolism risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2013;10:258–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, et al. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults - 9-year follow-up of the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30:736–743. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kissela B, Schneider A, Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Miller R, Alwell K, et al. Stroke in a biracial population: The excess burden of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 2004;35:426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Abel G, Lin IF, Elkind M, Hauser WA, et al. Race-ethnic disparities in the impact of stroke risk factors - the northern manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 2001;32:1725–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, McClure LA, Safford MM, Rhodes JD, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Annals of neurology. 2011;69:619–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnani JW, Norby FL, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, Loehr LR, et al. Racial differences in atrial fibrillation-related cardiovascular disease and mortality: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:433–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabra R, Girotra S, Sarrazin MV. Refining stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation patients by addition of african-american ethnicity to cha2ds2-vasc score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, Bleicher PA, Crown WH. Optum labs: Building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1187–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFrank JT, Bowling JM, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Skinner CS. Triangulating differential nonresponse by race in a telephone survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4:A60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172; discussion 207–112. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying quantitative bias analysis to epidemiologic data. New York: Springer-Verlag New York; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao T-F, Lip GYH, Liu C- J, Tuan T- C, Chen S- J, Wang K- L, et al. Validation of a modified cha(2)ds(2)-vasc score for stroke risk stratification in asian patients with atrial fibrillation: A nationwide cohort study. Stroke. 2016;47:2462–2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao TF, Liu CJ, Wang KL, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, et al. Using the cha2ds2-vasc score for refining stroke risk stratification in ‘low-risk’ asian patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1658–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn GR, Severdija ON, Chang Y, Singer DE. Wide variation in reported rates of stroke across cohorts of patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2017;135:208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shroff GR, Solid CA, Herzog CA. Atrial fibrillation, stroke, and anticoagulation in medicare beneficiaries: Trends by age, sex, and race, 1992–2010. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabra R, Cram P, Girotra S, Sarrazin MV. Effect of race on outcomes (stroke and death) in patients > 65 years with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:230–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.