Abstract

Purpose of review

This review examines recent literature regarding analysis of the throwing motion in baseball players and how modern technology may be used to predict or prevent injury.

Recent findings

Proper throwing technique is vitally important to prevent injury and it is easier to correct poor mechanics prior to foot strike. Recent findings suggest that the inverted-W position may not lead to an increased risk of injury, but incorrect trunk or pelvis rotation does. Three-dimensional motion analysis in a laboratory setting is most commonly used to evaluate the throwing motion, but it does not allow for assessment in real game scenarios. Wearable monitors allow for this and have proven to reliably assess pitching workload, kinematics, and kinetics.

Summary

Injuries in youth baseball pitchers have increased along with the trend towards more single sport specialization. To prevent injury, assessment of a pitcher’s throwing motion should be performed early to prevent development of poor mechanics. Classically, three-dimensional motion analysis has been used to evaluate throwing mechanics and is considered the gold standard. Newer technology, such as wearable monitors, may provide an alternative and allow for assessment during actual competition.

Keywords: Pitching motion, Video analysis, Kinematics of pitching, Kinetics of pitching, Pitching flaws, Wearables

Introduction

Injuries to baseball pitchers have become more frequent and are occurring at younger ages [1]. Conte et al. looked at injury trends in Major League Baseball (MLB) over 18 seasons (1998–2015) and found that shoulder injuries decreased, but elbow injuries increased [2]. In particular, ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries are increasing as almost 25% of MLB pitchers have undergone a UCL reconstruction [3]. The American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) has shown a 60% increase in UCL operations among high school and youth players since 1994 [4]. Petty et al. [5] reported a greater than 13% increase in UCL reconstructions in high school baseball players. The high injury rate has significant societal and financial impact, especially at the professional level. For example, Conte et al. found that 56.9% of disabled list days in MLB involved pitchers [6]. This has led to an increase in attention and resources targeted towards addressing this problem.

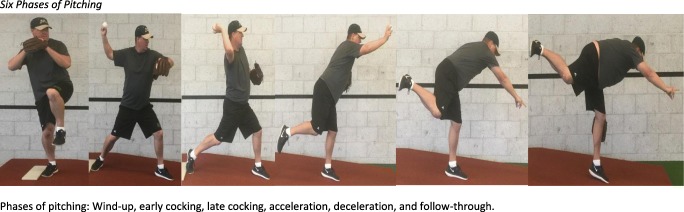

The pitching motion involves six phases of very coordinated muscle movements. Phases include wind-up, stride or early cocking, late cocking, acceleration, deceleration, and follow-through [7]. Incorrect technique involving each of these phases has been identified and can result in an increased risk of injury [7]. For example, if the pitching arm is lagging behind the torso and lower body before acceleration, it is not taking advantage of the potential energy created in the cocking phase which places greater stress on the arm and potentially leading to injury [8•]. Greater understanding of the pitching motion has led to more interest in its analysis with hopes of correcting poor throwing mechanics and preventing injury.

Three-dimensional motion analysis remains the gold standard way to evaluate a pitchers’ throwing motion. It requires a controlled laboratory type setting to achieve the best results. Newer technology, in the form of wearable monitors, has been developed and allows for analysis during actual competition [9•]. The primary purposes of this review are to summarize the throwing motion, examine how poor mechanics can lead to injury, and discuss the technology available for analysis.

Phases of the pitching motion

The pitching motion involves six phases of very coordinated muscle movements: wind-up, stride or early cocking, late cocking, acceleration, deceleration, and follow-through (Fig. 1). During these phases, energy created by the lower body and core musculature is transferred to the throwing arm leading to ball release [7].

Fig. 1.

Six phases of pitching. Phases of pitching: wind-up, early cocking, late cocking, acceleration, deceleration, and follow-through

Wind-up

Wind-up is the classic phase in which many envision a pitcher preparing to deliver the pitch. In this phase, the hands are brought together in the mid-torso region and the knee of the lead leg is lifted into the air [7, 10].

Stride

During the stride phase, or early cocking, the velocity of the pitch is generated. The lead leg extends while the pelvis rotates and the arm assumes the cocking position. The back foot must remain planted during this phase [7, 10].

Late cocking

Many of the shoulder and elbow injuries experienced by pitchers are encountered during the late cocking phase [11, 12]. This is likely due to the fact that elbow valgus and rotational shoulder torque are highest during this phase [13, 14]. Much of the energy from the lower body is transferred to the upper body as it rotates towards the batter. This phase begins when the lead foot strikes the ground [7, 10].

Acceleration

During the acceleration phase, the shoulder internally rotates, the elbow extends, and the elbow flexes as the energy produced by the body is transferred to the baseball [7, 10].

Deceleration

In this phase, the baseball is released and the internal rotation of the arm is slowed [7, 10]. The rotator cuff muscles are activated to resist the forward movement of the arm [15].

Follow-through

The pitching motion is completed and the force generated by the body is dissipated. The body assumes a relaxed position to allow for fielding of the baseball [7, 10].

Flaws in the pitching motion

A pitcher may be more successful in correcting poor throwing habits early in the pitching motion. Fleisig et al. [16•] found that it is easier to change throwing biomechanics prior to foot strike rather than later in the motion around ball release. Therefore, the assessment of pitching biomechanics should address timing in the cocking phases before acceleration. If the pitching arm is lagging behind the body before acceleration, it is not taking advantage of the potential energy created in the cocking phases. This is often referred to as throwing “all arm” [8•]. Higher elbow valgus stress has been correlated with poor trunk rotation timing [13, 17] along with increased shoulder external rotation angle and joint force [18].

The power position is important for the analysis of a pitcher. It is located at the end of the early cocking phase when the foot strikes the ground. A correct power position has the lead arm out in front with 70–80 degrees of shoulder abduction and the elbow flexed around 90 degrees with the wrist positioned facing the pitcher. This position is referred to as the “tell time position” (Fig. 2). An incorrect power position can inform the clinician that there is a breakdown earlier in the motion hindering the thrower’s ability to achieve this position correctly. Timing is negatively impacted if the correct power position is not obtained.

Fig. 2.

(1) “Power position” in early cocking phase. (2) Lead arm in “tell-time” position

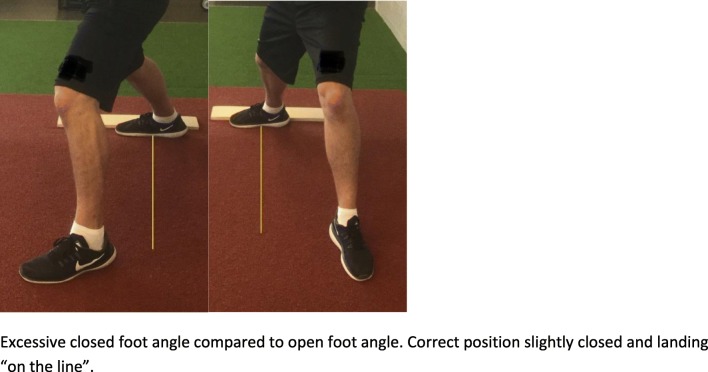

Hyper-abduction, often referred to as “loading,” should be minimized in the pitching motion. When viewing from anterior, the ball should be obscured by the pitcher’s head. The hand should be on top of the ball and facing third base for right-handed pitchers or first base for left-handed pitchers. The lead foot should be pointed towards home plate in a slightly internally rotated or “closed” position (Fig. 3). Calabrese [19•] demonstrated that an excessively closed front foot can lead to the pitcher throwing across their body. This closes off the front leg and pelvis which does not allow proper energy transfer from the lower body to the pitching arm. This often leads to a timing error and the pitching arm lags behind the body, placing more stress on shoulder complex and elbow as the arm moves from acceleration to ball release. If the pitcher displays an open front foot position the opposite can occur with the pelvis opening too soon and allowing early pelvic rotation (Fig. 3). This can also create an arm lag which places significant valgus stress on the elbow.

Fig. 3.

Excessive closed foot angle compared to open foot angle. Correct position slightly closed and landing “on the line”

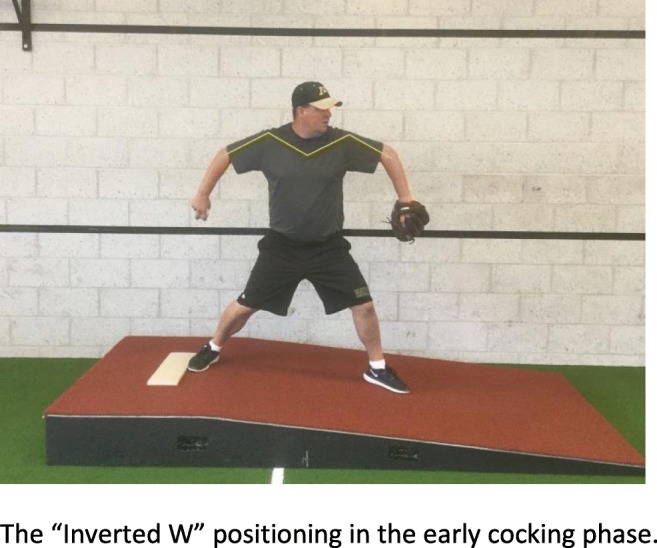

Douoguih et al. [8•] evaluated two mechanical flaws, including the inverted-W arm position that occurs in the early cocking phase and early trunk rotation (Fig. 4). The authors reviewed a video of 250 MLB pitchers and correlated with injury data. They aimed to determine if the inverted-W arm position or early trunk rotation increased the risk of an injury. They found that early trunk rotation did correlate with an increased risk of injury requiring surgery; however, the inverted-W position did not. Although suspected by some, more studies are needed to determine if the inverted-W position places increased stress on the arm.

Fig. 4.

The “inverted W” positioning in the early cocking phase

Fleisig et al. [16•] explored the ability of a pitcher to make biomechanical changes to their delivery. The study looked at eight kinematic parameters during the pitching motion. Five (stride length, front foot position, shoulder external rotation, shoulder abduction, and elbow flexion) were assessed at foot strike. Time between peak pelvis angular velocity and peak upper trunk angular velocity and knee extension from foot contact to ball release were evaluated in the arm cocking or acceleration stage. Shoulder abduction was assessed at ball release. They found correction rates were highest with front foot position (67%) and time between peak pelvis angular velocity and peak upper trunk angular velocity (64%). Parameters most difficult to correct were later in the pitching sequence. This included knee extension from foot contact to ball release (23%) and shoulder abduction at ball release (32%). They concluded that less than 50% of the parameters could be altered and it was toughest to adjust later in the pitching motion.

Riff et al. [20•] found differences in the mechanics of older and younger pitchers. Older pitchers tended to lead with their hips, have their hand on top of the ball, obtain a closed shoulder position at foot strike, and have proper hip and shoulder rotation. Positioning with the hand under the ball in the early cocking phase was commonly seen in younger pitchers. This places more stress on the medial elbow and shoulder [21]. Riff et al. [20•] found that 92% of pitchers younger than 13 years old maintained their hand on top of the ball, whereas 100% of pitchers over 13 years old were able to do this. The closed shoulder position was correct in 62% of pitchers between 9 and 12 years old. In contrast, it was correct in 79% of 13- to 15-year-old pitchers. As pitchers aged, stride length, knee flexion at foot strike, and hip flexion at foot strike all significantly increased. All of these contribute to a reduction in load on the throwing arm.

Seventy-eight pitchers were included in a study by Solomito et al. [22] looking at the association between forearm mechanics and elbow varus movement. They found that pitchers held their arm in supination more while throwing a curveball compared to a fastball. Additionally, the position of the forearm showed no association with elbow varus movement. However, increases in forearm supination have been shown to increase elbow varus movement, which may increase the risk of injury [22].

Fehr et al. [23] studied how age and experience impact elbow biomechanics of pitching. They found that more pitching experience resulted in increased external rotation during the late cocking phase and increased flexion in the early cocking phase. Less experienced pitchers showed more range of motion in supination and pronation during early and late cocking phases. The study suggested that experience played a greater role in pitching mechanics than age. Luera et al. [24] compared professional and high school pitchers’ rotational kinematics and elbow varus torque. They found pitch velocity and absolute elbow varus torque during the cocking stages and at maximum external rotation to be greater in professional pitchers. Additionally, high school pitchers did not demonstrate proper trunk and pelvis rotation, which can lead to increased forces being placed through the shoulder and elbow. This was especially apparent in those throwing at higher velocities. This study suggests correction of trunk and pelvis kinematics should be a high priority before increasing pitching velocity.

Fleisig et al. [25] reported significant changes in the kinematics and kinetics of youth pitchers in their first few years of pitching (9–13 years old). The changes made were around foot strike and included a longer stride, improved foot position, and better trunk separation. They showed an increase in elbow varus torque from 13 to 15 years old. It has been reported that youth pitchers have three times greater activation of the rotator cuff and biceps muscles compared to professional pitchers [24]. This puts adolescents at a higher risk for overuse injury and suggests protection measures need to be established early. Protection methods should include avoidance of overuse. This can be accomplished by minimizing pitch counts, avoiding pitching year-round, and avoiding early single-sport specialization. Other protection measures include proper arm care programs and correction of poor pitching biomechanics. Many believe that learning proper mechanics early will allow for sustained proper mechanics with age [26–28].

Pitching motion analysis

A clinician or coach can view a pitcher’s mechanics utilizing many different modalities. Three-dimensional motion analysis is performed in the laboratory setting and uses multiple cameras and sensors. This is considered the gold standard and it provides in-depth data including many kinematic and kinetic values (Table 1). Two-dimensional video analyses with high-speed cameras or phone applications are commonly used as well. Some have questioned whether these have the ability to accurately evaluate the actual stresses experienced by a pitcher’s arm during a live-game environment. This led to the development of newer technology in the form of wearable monitors.

Table 1.

Pitching kinetic and kinematic flaws to assess

| Wind-up | |

| • Little head movement. Large side step in wind-up can move head affecting vision. | |

| • Good balance point with stable center of gravity (COG). Leaning too far anteriorly or posteriorly can affect timing of pitch and proper energy transfer. [11] | |

| • Pelvic drift: 20 ± 5 cm. [22] | |

| • Glove should be at chest height. [11] | |

| Stride (early cocking) | |

| • Stride length % of height: 66–85% [23], 85–100% [11], 77–90% [22]. Youth at 66% of height [24]. Longer strides can increase pitching velocity without affecting accuracy [8•, 22, 25]. | |

| • Shoulder abduction at foot strike: 78°–95° [23], 93° ± 11° [22]. | |

| • Elbow flexion at foot strike: 74°–85° [23], 90° ± 15° [22], 87° [27]. | |

| • Knee flexion at foot strike: 40°–49° [23], 43° ± 10° [22]. | |

| • Foot angle: 14°–21.6° [23], 17° ± 9° [22]. Stride foot direction slightly closed. | |

| • Stride foot lands straight out from back foot “on a line.” | |

| • Correct “power position.” | |

| • Hand on top of the ball. | |

| • Hands break as lead knee moves towards home plate [22]. | |

| • Maximum pelvic rotation velocity: 601.9–1202.2°/s [23], 590 ± 80°/s [22]. | |

| • Maximum shoulder internal rotation torque: 17.7–36.9 N m. [27] | |

| • Maximum elbow varus torque: 27–37 N m. [27] | |

| • Maximum elbow valgus torque: 18 N m. [27] | |

| Late cocking | |

| • Maximum shoulder external rotation: 166°–178.2° [23], 182° ± 8° [22]. | |

| • Maximum elbow flexion: 95°–100.8° [23], 102° ± 11° [22]. | |

| • Shoulder abduction at maximum shoulder external rotation: 66°–92° [15], 90°–100° [11]. | |

| • Elbow flexion at maximum shoulder external rotation: 57°–95° [23], 90° [11]. | |

| • Proper trunk rotation. | |

| • Elbow valgus torque at foot contact: 1.7–2 N m [23]. | |

| • Maximum shoulder internal rotation velocity: 3396–9000°/s [23], 7510 ± 850°/s [22]. | |

| • Elbow valgus torque at maximum external rotation: 12.8–13 N m. [27] | |

| Acceleration | |

| • Shoulder abduction at ball release: 70°–94° [23], 94° ± 8° [22]. | |

| • Shoulder external rotation at ball release: 109°–143.4° [23]. | |

| • Elbow flexion at ball release: 24°–39° [23], 24° ± 5° [22]. | |

| • Forward trunk tilt at ball release: 30°–33.4° [23], 32°–55° [11], 36° ± 7° [22]. | |

| • Lateral trunk tilt at ball release: 21°–29.5° [23], 23° ± 10° [22]. | |

| • Knee flexion at ball release: 31.2°–41° [23], 35° ± 13° [22]. | |

| • Glove tuck at ball release. | |

| • Maximum elbow extension angular velocity: 1742–2272°/s [27], 2350 ± 330°/s [22]. | |

| • Elbow flexion torque: 16.4–28 N m [27]. | |

| • Shoulder horizontal adduction torque: 39.1 N m. [27] | |

| • Elbow valgus torque at ball release: 3.5–4 N m. [27] | |

| Deceleration | |

| • Minimum elbow flexion: − 8° [23]. | |

| • Maximum shoulder horizontal abduction torque: 40 N m. [27] | |

| • Maximum shoulder proximal force: 214.7–480 N m. [27] | |

| Follow-through | |

| • Ending in a good fielding position. Falling off the mound, correct flaws at stride phase [11]. | |

| • Back of shoulder is shown. | |

| • Forward trunk tilt: 49 ± 9° [22]. | |

| • Lead knee flexion: 22 ± 12° [22]. |

Small motion sensors or wearables are placed on the arm and can offer a way of tracking workload in a live game environment. The data can often be transferred to a tablet or cellphone using Bluetooth technology. A motusBASEBALL sleeve sensor was the first wearable monitoring device approved by major league baseball to be worn in a game. It allows for measurement of arm slot, arm speed, shoulder external rotation, and peak elbow valgus torque. Wearable technology provides an alternative option to three-dimensional motion analysis that may be more accurate and cost-effective.

A pilot study comparing wearable devices and three-dimensional motion analysis was performed. It showed comparable results for elbow varus torque, arm rotation, arm slot, and arm speed [29]. Rawashdeh et al. [29] used a wearable IMU (inertial measurement unit) to track baseball throws and volleyball serves. The authors reported an 86% overall accuracy rate using the IMU.

Camp et al. [9•] used a wearable monitor to assess elbow varus torque in 81 professional pitchers performing 82,000 throws. They found a 1 N·m increase in elbow varus torque caused by a 13° decrease in arm slot, 8° increase in maximal arm rotation, and a 116°/s increase in arm speed. Arm slot alterations increased torque on the elbow and a side arm slot had a higher risk of injury than an over the top delivery. Their belief was that increased shoulder external rotation, increased velocity, and elbow varus torque were interrelated. Other authors have linked increased shoulder external rotation with increased elbow varus torque [3, 13, 14, 30•,31–33].

Makhni et al. [30•] evaluated elbow varus torque using wearable monitors in 37 baseball pitchers throwing various pitch types. Arm speed, arm slot, and maximum shoulder external rotation were recorded for 888 total pitches. They found that the wearable monitors accurately measured fastballs in 96.9%, curveballs in 96.9%, and change-ups in 97.9% of all throws. Fastballs caused the greatest elbow varus torque and velocity was the greatest indicator of torque on the medial elbow. The wearable monitors offered a convenient and accurate option for monitoring pitching parameters.

Wearable monitors may give us substantially more data in a live game environment. They may provide insight into the forces experienced by the arm during the pitching motion and lead to the reduction of injuries. Further studies testing the accuracy of the received data are necessary. They are emerging as a cost-effective way to track workload and correct mechanical flaws.

Conclusions

Injuries in youth baseball pitchers have increased along with the trend towards more single sport specialization. To prevent injury, assessment of a pitcher’s throwing motion should be performed early to prevent development of poor mechanics. Classically, three-dimensional motion analysis has been used to evaluate throwing mechanics and is considered the gold standard. Newer technology, such as wearable monitors, may provide an alternative and allow for assessment during actual competition.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Injuries in Overhead Athletes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Melugin HP, Leafblad ND, Camp CL, Conte S. Injury prevention in baseball: from youth to the pros. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(1):26–34. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conte S, Camp CL, Dines JS. Injury trends in major league baseball over 18 seasons: 1998-2015. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2016;45(3):116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conte SA, Fleisig GS, Dines JS, Wilk KE, Aune KT, Patterson-Flynn N, ElAttrache N. Prevalence of ulnar collateral ligament surgery in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1764–1769. doi: 10.1177/0363546515580792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ASMI. UCL surgeries on adolescent baseball pitchers: ASMI; [Available from: http://www.asmi.org/research.php?page=research§ion=UCL. Accessed 18 Dec 2018.

- 5.Petty DH, Andrews JR, Fleisig GS, Cain EL. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in high school baseball players: clinical results and injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(5):1158–1164. doi: 10.1177/0363546503262166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431–436. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290040801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers PN, Wimmer MA, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, Cvetanovich GL, Pearl ML. The relationship between pitching mechanics and injury: a review of current concepts. Sports Health. 2017;9(3):216–221. doi: 10.1177/1941738116686545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douoguih WA, Dolce DL, Lincoln AE. Early cocking phase mechanics and upper extremity surgery risk in starting professional baseball pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(4):2325967115581594. doi: 10.1177/2325967115581594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camp CL, Tubbs TG, Fleisig GS, Dines JS, Dines DM, Altchek DW, et al. The relationship of throwing arm mechanics and elbow varus torque: within-subject variation for professional baseball pitchers across 82,000 throws. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(13):3030–3035. doi: 10.1177/0363546517719047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402–408. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. Shoulder injuries in overhead athletes. The “dead arm” revisited. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(1):125–158. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bey MJ, Elders GJ, Huston LJ, Kuhn JE, Blasier RB, Soslowsky LJ. The mechanism of creation of superior labrum, anterior, and posterior lesions in a dynamic biomechanical model of the shoulder: the role of inferior subluxation. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1998;7(4):397–401. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguinaldo AL, Chambers H. Correlation of throwing mechanics with elbow valgus load in adult baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):2043–2048. doi: 10.1177/0363546509336721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anz AW, Bushnell BD, Griffin LP, Noonan TJ, Torry MR, Hawkins RJ. Correlation of torque and elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1368–1374. doi: 10.1177/0363546510363402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med. 1996;21(6):421–437. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199621060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleisig GS, Diffendaffer AZ, Ivey B, Aune KT. Do baseball pitchers improve mechanics after biomechanical evaluations? Sports Biomech. 2018;17(3):314–321. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2017.1340508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JT, Limpisvasti O, Fluhme D, Mohr KJ, Yocum LA, Elattrache NS, et al. The effect of pitching biomechanics on the upper extremity in youth and adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(8):1484–1491. doi: 10.1177/0363546509340226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyama S, Yu B, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Li L, Myers JB. Improper trunk rotation sequence is associated with increased maximal shoulder external rotation angle and shoulder joint force in high school baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2089–2094. doi: 10.1177/0363546514536871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calabrese GJ, et al. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(5):652–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riff AJ, Chalmers PN, Sgroi T, Lesniak M, Sayegh ET, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA. Epidemiologic comparison of pitching mechanics, pitch type, and pitch counts among healthy pitchers at various levels of youth competition. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(8):1559–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegl UJ, Warth RJ, Millett PJ. Symptomatic internal impingement of the shoulder in overhead athletes. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2014;22(2):120–129. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomito MJ, Garibay EJ, Nissen CW. A biomechanical analysis of the association between forearm mechanics and the elbow varus moment in collegiate baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(1):52–57. doi: 10.1177/0363546517733471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fehr S, Damrow D, Kilian C, Lyon R, Liu XC. Elbow biomechanics of pitching: does age or experience make a difference? Sports Health. 2016;8(5):444–450. doi: 10.1177/1941738116654863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luera MJ, Dowling B, Magrini MA, Muddle TWD, Colquhoun RJ, Jenkins NDM. Role of rotational kinematics in minimizing elbow varus torques for professional versus high school pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(3):2325967118760780. doi: 10.1177/2325967118760780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleisig GS, Diffendaffer AZ, Ivey B, Aune KT, Laughlin T, Fortenbaugh D, Bolt B, Lucas W, Moore KD, Dugas JR. Changes in youth baseball pitching biomechanics: a 7-year longitudinal study. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(1):44–51. doi: 10.1177/0363546517732034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stodden DF, Langendorfer SJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Kinematic constraints associated with the acquisition of overarm throwing part I: step and trunk actions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77(4):417–427. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stodden DF, Langendorfer SJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Kinematic constraints associated with the acquisition of overarm throwing part II: upper extremity actions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77(4):428–436. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishida K, Murata M, Hirano Y. Shoulder and elbow kinematics in throwing of young baseball players. Sports Biomech. 2006;5(2):183–196. doi: 10.1080/14763140608522873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawashdeh SA, Rafeldt DA, Uhl TL. Wearable IMU for shoulder injury prevention in overhead sports. Sensors (Basel). 2016;16(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Makhni EC, Lizzio VA, Meta F, Stephens JP, Okoroha KR, Moutzouros V. Assessment of elbow torque and other parameters during the pitching motion: comparison of fastball, curveball, and change-up. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(3):816–822. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabick MB, Torry MR, Lawton RL, Hawkins RJ. Valgus torque in youth baseball pitchers: a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2004;13(3):349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bushnell BD, Anz AW, Noonan TJ, Torry MR, Hawkins RJ. Association of maximum pitch velocity and elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(4):728–732. doi: 10.1177/0363546509350067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chalmers PN, Sgroi T, Riff AJ, Lesniak M, Sayegh ET, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA. Correlates with history of injury in youth and adolescent pitchers. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]