Abstract

Aim

To report long-term data regarding biochemical control and late toxicity of simultaneous integrated boost intensity modulated radiotherapy (SIB-IMRT) with tomotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer.

Background

Dose escalation improves cancer control after curative intended radiation therapy (RT) to patients with localized prostate cancer, without increasing toxicity, if IMRT is used.

Materials and methods

In this retrospective analysis, we evaluated long-term toxicity and biochemical control of the first 40 patients with intermediate risk prostate cancer receiving SIB-IMRT. Primary target volume (PTV) 1 including the prostate and proximal third of the seminal vesicles with safety margins was treated with 70 Gy in 35 fractions. PTV 2 containing the prostate with smaller safety margins was treated as SIB to a total dose of 76 Gy with 2.17 Gy per fraction. Toxicity was evaluated using an adapted CTCAE-Score (Version 3).

Results

Median follow-up of living patients was 66 (20–78) months. No late genitourinary toxicity higher than grade 2 has been reported. Grade 2 genitourinary toxicity rates decreased from 58% at the end of the treatment to 10% at 60 months. Late gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity was also moderate, though the prescribed PTV Dose of 76 Gy was accepted at the anterior rectal wall. 74% of patients reported any GI toxicity during follow up and no toxicity rates higher than grade 2 were observed. Grade 2 side effects were reported by 13% of the patients at 60 months. 5-year freedom from biochemical failure was 95% at our last follow up.

Conclusion

SIB-IMRT using daily MV-CT guidance showed excellent long-term biochemical control and low toxicity rates.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Late toxicity, Rectal toxicity, Fractionation, Long term follow up, Tomotherapy

1. Background

Dose escalation improves cancer control after curative intended radiation therapy (RT) to patients with localized prostate cancer, without increasing toxicity, if intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)19, 30, 33 is used. The implementation of modern treatment (IMRT) and verification techniques (image guided radiotherapy, IGRT) to radiotherapy27 offered the opportunity to create hypofractionated treatment approaches. Due to the fact that the α/β ratio for prostate cancer is supposed to be in the range between 1–3 Gy,24, 26 these regimens have the potential to deliver higher or at least equivalent biologically effective dose over a shorter period of time, compared to conventional fractionation schemes. As the α/β ratio for prostate cancer is also assumed to be lower than that for the rectal wall, hypofractionated radiotherapy should additionally improve the therapeutic gain.

In this context, the results of larger randomized clinical trials on local control and toxicity are increasingly available,1, 3, 5, 15, 17, 25 but cannot unequivocally prove these theoretical considerations using hypofractionated concepts with single doses in the range between 2.5 and 3.4 Gy.16 The patients treated in the HYPRO-trial, for example, received single doses of 3.4 Gy to 64.6 Gy in three fractions a week, whereas in a study conducted at the Fox Chase Center, the patients were treated from 2.7 Gy up to 70.2 Gy in five weekly fractions. The follow up of the studies ranged from 49 to 70 months. In this range, all of the studies at least could show non-inferiority of their treatment schedules, compared to the normofractionated control-arms concerning biochemical control. But it should be mentioned, that higher acute toxicity and at least a trend to a pronounced late toxicity were observed in some of the trials.1, 25

2. Aim

In this analysis we report long-term outcomes at a median follow up of 66 Months, on biochemical control and toxicity for the first 40 patients, treated at our department with helical tomotherapy using a slightly hypofractionated SIB-IMRT to a total dose of 76 Gy in 2.17 Gy per fraction applied to the prostate, to update previously shown results on acute toxicity.10

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Patient characteristics

Starting in February 2008, patients with pathologically confirmed intermediate risk localized prostate cancer (cN0 cM0) were treated with SIB-IMRT at a tomotherapy unit. The last patient in this cohort was treated before November 2009. Patients with intermediate risk prostate cancer were defined according to D’Amico or: (1) not having low-risk features (cT1 and Gleason Score <7 and initial PSA ≤10 ng/ml) and (2) not having a risk of ≥20% of lymph node metastasis according to the Roach formula.28 Three high risk patients were treated with SIB-IMRT on an individual basis. To all intermediate risk patients short-term androgen deprivation 6-month therapy was recommended, starting 3–4 months before radiotherapy. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patients (n) | 40 |

| Median age [years (range)] | 72 (60–82) |

| Disease stage [n (%)] | |

| T1 | 12 (30) |

| T2 | 28 (70) |

| T3 | 0 (0) |

| Gleason score [n (%)] | |

| 4 | 2 (5) |

| 5 | 1 (2.5) |

| 6 | 15 (37.5) |

| 7 | 21 (52.5) |

| 8 | 1 (2.5) |

| Median pretreatment PSA-Level [ng/ml (range)] | 7.7 (2.85–24.0) |

| Median prostate dose [Gy (range)] | 77.04 (75.81–79.51) |

| Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy [n (%)] | 36 (90) |

| Median duration [months (range)] | 3 (0–7) |

3.2. Treatment

Treatment including planning, delivery and quality assurance as well as target volume and definition of Organs at risk has been described previously.10

In brief, a CT-scan of the pelvis was performed for treatment planning. Furthermore, an MRI-scan was carried out and fused to the Planning-CT. Patients were immobilized for treatment in an individually shaped vacuum cushion. For immobilization of the prostate an endorectal balloon was used. The Gross Tumor Volume (GTV) comprised the prostatic gland and base of seminal vesicles with possible extracapsular macroscopic tumor spread. The margins for the Clinical Target Volume (CTV) were 5 mm in all directions, except for the rectal interface with no additional safety margin. Planning Target Volume 1 (PTV1) encompassed the CTV with a safety margin of 3 mm in all directions, except for the cranio-caudal direction with margins of 5 mm. The PTV2 encompassed a smaller GTV containing prostatic gland only, with a 3 mm in the plane and a 5 mm margin in the cranio-caudal direction. A helper structure (Rectum-76) containing the overlap of PTV2 with the rectum and 3 mm anteriorly was created to limit the dose to this structure to ≤100% of the prescribed dose to PTV2, no further sparing of the PTV rectal overlap was performed not to compromise the PTV coverage. The prescribed dose was 70 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction to the PTV1 and 76 Gy in 2.17 Gy per fraction to the PTV2. The planning objective was to cover at least 95% of the PTV2 with 76 Gy. The maximum dose should not exceed 107% of the prescribed dose. This equals an EQD2 of 78.6 Gy3 assuming an α/β ratio of 3 for prostate cancer cells, or 79.7 Gy1.5 assuming an α/β ratio of 1.5.

Organs at risk were delineated as a whole (e.g. delineating the outer contour); the rectum extended caudally from the anal verge to the point where it merges into the sigma cranially. Radiation exposure of organs at risk was kept as low as reasonably achievable, checking for volumes receiving high doses of at least 60 Gy (V60) to 76 Gy (V76), as well as intermediate doses of at least 35 Gy (V35) to 59 Gy (V59).

After set-up, patients received an MV-CT prior to each treatment fraction. The MV-CT was then automatically fused to the planning CT scan and manually corrected if necessary.

3.3. Follow up

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) symptoms were prospectively documented before, at the end of radiotherapy, 3 and 6 months after treatment and once a year thereafter. Patients not compliant for a clinical visit at our department were contacted by the authors 36, 48, 66 months after enrollment of the last patient. Toxicity was scored according to slightly adapted CTCAE version 3 criteria. Biochemical failure was defined according the Phoenix definition of PSA nadir +2 ng/ml.

Biochemical control and survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

4. Results

4.1. Toxicity

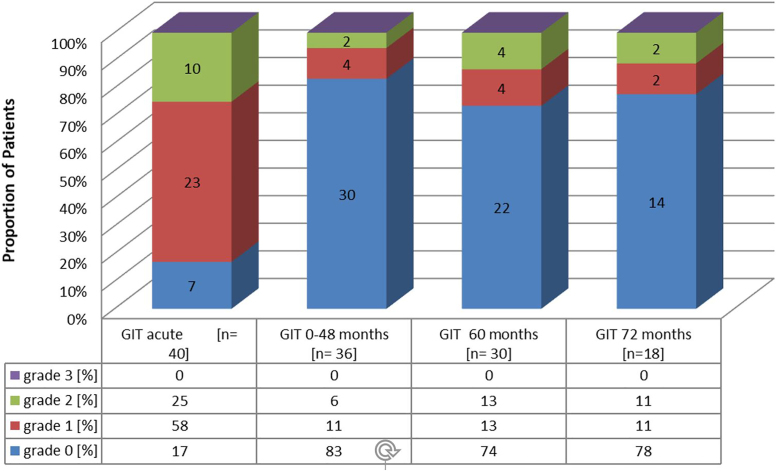

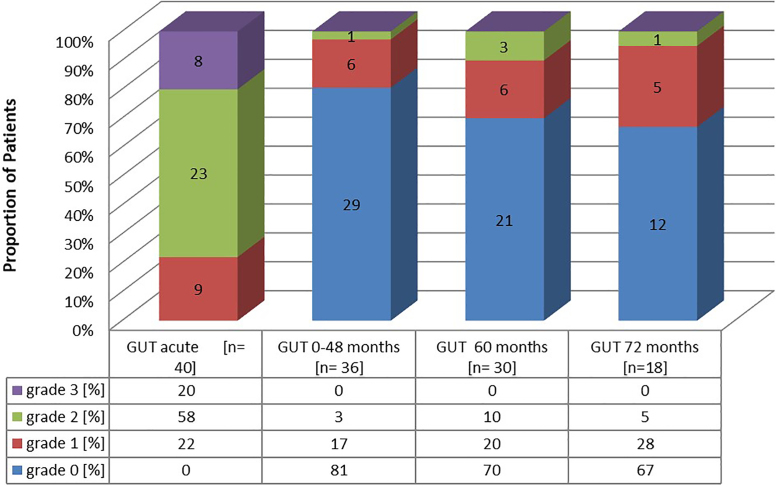

A cumulative dose–volume histogram (DVH) using overall patient's mean planning values for the rectum, bladder and femoral heads is depicted in Fig. 1. Table 2 additionally displays dosimetric data for the rectum and bladder. Maximum reported GI and GU toxicity rates at the end of treatment, 22–48, 60 and 72 months after treatment are listed in Fig. 2, Fig. 3. No grade 4 GI or GU toxicity was observed at any time of treatment and follow up. Grade 3 GU toxicity occurred in 20% of patients at the end of treatment. Side effects of all these patients declined at least to grade 2 within follow-up. Overall Grade 2 GU toxicity was observed in 58% of patients at the end of treatment. Within follow-up Grade 2 GU toxicity rates decreased to 10% at 60 months and 5% at 72 months (comprising 18 patients for analysis at the time of last evaluation).

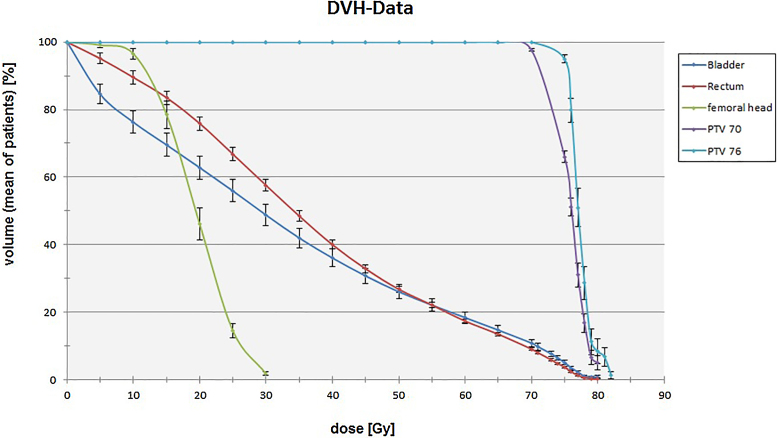

Fig. 1.

Cumulative dose–volume histogram (DVH) using overall patients mean planning values and error bars for standard error of the means.

Table 2.

Dosimetric data for rectum and bladder. Mean volume values VX in percent, which at least received the cumulative radiation dose X, including standard deviation and p-value for independent random samples, executed bilaterally.

| V35 (%) | V40 (%) | V50 (%) | V55 (%) | V60 (%) | V65 (%) | V70 (%) | V76 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectum | 48.31 ± 1.79 | 39.90 ± 1.51 | 26.60 ± 1.06 | 21.65 ± 0.90 | 16.87 ± 0.78 | 12.98 ± 0.64 | 8.67 ± 0.49 | 2.27 ± 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Bladder | 39.36 ± 2.91 | 33.60 ± 2.65 | 24.03 ± 2.07 | 20.37 ± 1.82 | 16.87 ± 1.57 | 13.43 ± 1.29 | 9.88 ± 1.04 | 3.17 ± 0.52 | 0.006–0.404 |

Fig. 2.

Incidence of acute GI toxicity (GIT) and prevalence of late GIT during follow up. Numbers in bars display the absolute number of patients.

Fig. 3.

Incidence of acute GU toxicity (GUT) and prevalence of late GUT during follow up. Numbers in bars display the absolute number of patients.

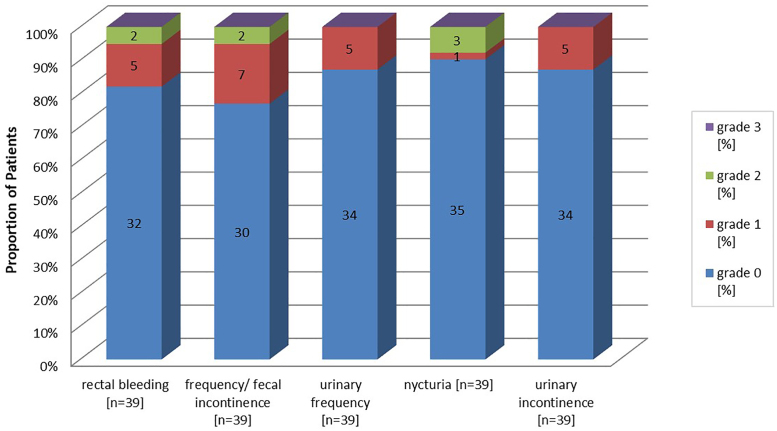

Regarding GI side effects, 25% patients reported grade 2 symptoms at the end of treatment. After 60 and 72 months, only two and four patients, respectively, reported Grade 2 GI toxicity, mentioning that two of the four patients did not reach Follow up of 72 months at the time of analysis. 74% of patients recovered about six months after treatment and stayed without any further late GI toxicity during follow-up. The overall incidence of observed symptoms is shown in Fig. 4. The Symptoms described higher than grade 1 included rectal bleeding and increased stool frequency/fecal incontinence each in two patients as well as nycturia in three patients. Grade 2 fecal incontinence of one patient might be related to his individual sexual preferences, which can be considered as pre-treatment risk factor.4, 22

Fig. 4.

Incidence of maximum reported late side effects within follow-up. Numbers in bars display the absolute number of patients with corresponding symptoms.

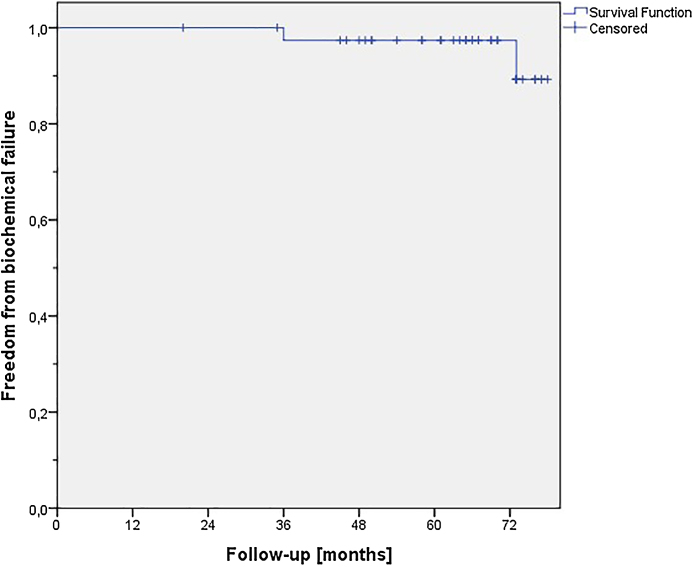

4.2. Biochemical disease-free survival (bDFS)

With a median follow-up of 66 (20–78) months for living patients, the analysis of post treatment PSA-values showed 2 cases of biochemical failure leading to a 5-year control rate of 95% (Fig. 5). The first failure was seen 36 months after treatment, and in the second patient it was diagnosed after 73 months of follow up. The two patients had no significantly increased risk factors as compared to the patients not developing a biochemical failure. Pretreatment PSA-values were 14.74 and 15.39 respectively. In both patients androgen deprivation therapy was re-initiated by the co-treating urologists and both patients had stable diseases regarding the PSA-values at the last FU. In addition to the above-mentioned events, two patients died during FU (lung cancer and one non-cancer or treatment related death) with no evidence of recurrent prostate cancer disease at the time of their last FU.

Fig. 5.

Freedom from biochemical failure according to Phoenix definition.

5. Discussion

This report is on long term outcome of SIB-IMRT with helical tomotherapy as an institutional protocol for primary treatment of prostate cancer patients. Biochemical control and late toxicity in a well-defined intermediate risk patient sample were analyzed. Biochemical control after SIB-IMRT combined with 6-month neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was excellent. The results compare favorably to the biochemical control rates of patient samples with comparable risk category in most of the large studies on hypofractionated radiotherapy with or without ADT3, 5, 6, 17, 25 or conventional fractionated IMRT.7, 30 However, a limitation of our study is the small sample size, which hampers inter-study comparison.

The modest dose escalation in our treatment regime yielded these excellent 5-year control-rates and was not associated with high toxicity rates. We consider GU and GI toxicity during the entire treatment and follow up to be clinically acceptable. Both GI and GU toxicity are also comparable to the findings from the above mentioned large randomized trials comparing hypofractionated to normofractionated IMRT1, 3, 5, 25 and nonrandomized trials using normofractionated IMRT.6, 7, 13, 30

The median follow-up of 66 months in our sample should be sufficient to detect major GI toxicity. With regard to the considerations by Tagkalidis et al.31 and Fiorino et al.,9 that chronic proctitis was observed to occur usually between 8–13 months,31 though it can develop later during the first three years after radiotherapy. Furthermore, an improvement of symptoms up to 65 months after treatment was described by Goldner et al.,12 who evaluated mucosal changes with rectal endoscopy in prostate cancer patients having received curative intended radiotherapy.

Compared to our data Guckenberger et al.13 reported very low GI toxicity. They observed more than 80% of patients without any late GI side effects when evaluating 150 consecutive patients treated with IMRT using a simultaneous integrated boost technique to doses of 73.9 Gy (n = 41) and 76.2 Gy (n = 109) in 32 and 33 fractions, respectively. Notably, they required sparing of the PTV overlap to the anterior rectal wall and adherence to very strong rectal constraints. As previously mentioned, our treatment regime in contrast abstained from explicit sparing of the rectal overlap, just limiting the dose in this area to the prescribed PTV dose, not to compromise the PTV coverage. This planning objective was chosen, because there is data from a planning study that suggest that excluding the rectal overlap from the boostvolume might result in a marked decrease of tumor control due to underdosage.18 Furthermore, a clinical analysis by Engels et al.8 described the risk of reduced tumor control using too small margins for prostate IGRT.

Our observed low-grade GI toxicity rates are higher compared to rates reported by Guckenberger et al., especially regarding the rate of patients without any GI toxicity (80% vs. 69%). In contrast to that study, no grade 3 toxicity was found in our sample. On the other hand, considering a 5-year biochemical control rate of 80% in a comparable intermediate risk subgroup, our results seem to be in favor reporting the rate of 95%.

Comparing our GI toxicity to larger randomized trials, e.g. of the Fox Chase Center25 or the PROFIT-Trial,3 our observed toxicity seems to be lower, especially regarding the incidence of overall GI toxicity, keeping in mind the small number of our analyzed patients.

As already mentioned, our observed GU side effects are in the expected and comparable range of the toxicity reported in literature, where 5 to 7-year rates of symptoms grade 2 and higher are usually found in around 10% of the patients.

There are recent studies which could show that especially higher doses to the inferior parts of the bladder might be associated with grade ≥2 GU toxicity.2, 11, 14 The inferior bladder and, especially, the bladder trigone are usually parts of the PTV or at least are included into “higher” dose areas. Because stable anatomical shapes of these bladder parts are suggested irrespective of the bladder filling,20, 21, 23 it seems reasonable, that GU side effects do not vary heavily in comparable patient and treatment settings, using doses of about 80 Gy EQD1,5, as it is done by most of the modern curative intended radiotherapy concepts.

The small sample size and its retrospective design have to be mentioned as main limitations of our analysis, even though side effects and outcome data were documented prospectively. In contrast to that, the available follow-up period should be adequate to give reliable information on the outcome and toxicity data of our patient sample.

Despite these limitations, several aspects might have contributed to the excellent freedom from biochemical-failure rates. By combining the application of an endorectal balloon with daily MV-CT image guidance,34 not only the intrafractional movement of the prostate can be reduced,32 but also an easier interpretation of the MV-CT images is supposed.29 Therefore, using this combination compared to daily MV-CT image guidance only34 may further reduce the risk of a target miss during treatment. Moreover, not sparing the rectal wall explicitly might also have contributed to the very good biochemical control rates, and, due to accurate localization resulting from daily image guidance, rectal toxicity rates still remained at a clinically acceptable level.

6. Conclusions

The presented 5-year follow-up data of this institutional treatment protocol for prostate SIB-IMRT and daily IGRT with tomotherapy are promising. Very high rates of biochemical relapse-free survival are achieved in combination with a good toxicity profile. Further evaluation in a prospective randomized trial that includes the concept of reducing the SIB volume35 should be considered.

Ethical approval

All institutional guidelines were followed. German radiation protection laws request a regular analysis of outcomes in the sense of quality control and assurance; thus, in the case of purely retrospective studies, no additional ethical approval is needed under German law.

Consent to participate

Informed consent for radiation therapy was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Bavarian state law (Bayrisches Krankenhausgesetz §27 Absatz 4 Datenschutz) allows the use of patient data for research and publication, provided that any personal related data are kept anonymous.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Aluwini S., Pos F., Schimmel E. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:464–474. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagala P., Ingrosso G., Falco M.D. Predicting genitourinary toxicity in three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: a dose–volume parameters analysis of the bladder. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:1018–1024. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.165871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catton C.N., Lukka H., Gu C.S. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7397. JCO2016717397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun A.B., Rose S., Mitrani C. Anal sphincter structure and function in homosexual males engaging in anoreceptive intercourse. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:465–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dearnaley D., Syndikus I., Mossop H. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Muzio N.G., Fodor A., Noris Chiorda B. Moderate hypofractionation with simultaneous integrated boost in prostate cancer: long-term results of a phase I–II study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016;28:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolezel M., Odrazka K., Zouhar M. Comparing morbidity and cancer control after 3D-conformal (70/74 Gy) and intensity modulated radiotherapy (78/82 Gy) for prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2015;191:338–346. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0806-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels B., Soete G., Verellen D. Conformal arc radiotherapy for prostate cancer: increased biochemical failure in patients with distended rectum on the planning computed tomogram despite image guidance by implanted markers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:388–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorino C., Valdagni R., Rancati T. Dose–volume effects for normal tissues in external radiotherapy: pelvis. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:153–167. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geier M., Astner S.T., Duma M.N. Dose-escalated simultaneous integrated-boost treatment of prostate cancer patients via helical tomotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:410–416. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghadjar P., Zelefsky M.J., Spratt D.E. Impact of dose to the bladder trigone on long-term urinary function after high-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldner G., Potter R., Kranz A. Healing of late endoscopic changes in the rectum between 12 and 65 months after external beam radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187:202–205. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guckenberger M., Lawrenz I., Flentje M. Moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: long-term outcome using IMRT and volumetric IGRT. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heemsbergen W.D., Al-Mamgani A., Witte M.G. Urinary obstruction in prostate cancer patients from the Dutch trial (68 Gy vs. 78 Gy): relationships with local dose, acute effects, and baseline characteristics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman K.E., Voong K.R., Pugh T.J. Risk of late toxicity in men receiving dose-escalated hypofractionated intensity modulated prostate radiation therapy: results from a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1074–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Höcht S., Aebersold D.M., Albrecht C. Hypofractionated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00066-017-1137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Incrocci L., Wortel R.C., Alemayehu W.G. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassim I., Dirkx M.L., Heijmen B.J. Evaluation of the dosimetric impact of non-exclusion of the rectum from the boost PTV in IMRT treatment plans for prostate cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lips I.M., Dehnad H., Van Gils C.H. High-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer using daily fiducial marker-based position verification: acute and late toxicity in 331 patients. Radiat Oncol. 2008;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lotz H.T., Remeijer P., Van Herk M. A model to predict bladder shapes from changes in bladder and rectal filling. Med Phys. 2004;31:1415–1423. doi: 10.1118/1.1738961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lotz H.T., Van Herk M., Betgen A. Reproducibility of the bladder shape and bladder shape changes during filling. Med Phys. 2005;32:2590–2597. doi: 10.1118/1.1992207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markland A.D., Dunivan G.C., Vaughan C.P. Anal intercourse and fecal incontinence: evidence from the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:269–274. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meijer G.J., Rasch C., Remeijer P. Three-dimensional analysis of delineation errors, setup errors, and organ motion during radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1277–1287. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickers P., Hermesse J., Deneufbourg J.M. Which alpha/beta ratio and half-time of repair are useful for predicting outcomes in prostate cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2010;97(3):462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollack A., Walker G., Horwitz E.M. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3860–3868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proust-Lima C., Taylor J.M., Secher S. Confirmation of a low alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;79(1):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudat V., Nour A., Hammoud M. Image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2016;192:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00066-015-0919-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roach M., 3rd, Hanks G., Thames H., Jr. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiller K., Petrucci A., Geinitz H. Impact of different setup approaches in image-guided radiotherapy as primary treatment for prostate cancer: a study of 2940 setup deviations in 980 MVCTs. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190::722–726. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spratt D.E., Pei X., Yamada J. Long-term survival and toxicity in patients treated with high-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tagkalidis P.P., Tjandra J.J. Chronic radiation proctitis. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:230–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K.K., Vapiwala N., Deville C. A study to quantify the effectiveness of daily endorectal balloon for prostate intrafraction motion management. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zelefsky M.J., Chan H., Hunt M. Long-term outcome of high dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2006;176:1415–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zucca S., Carau B., Solla I. Prostate image-guided radiotherapy by megavolt cone-beam CT. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187:473–478. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-2241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zamboglou C., Thomann B., Koubar K. Focal dose escalation for prostate cancer using 68)Ga-HBED-CC PSMA PET/CT and MRI: a planning study based on histology reference. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(May (1)):81. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-1036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]