Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an important and rising cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and early detection of undiagnosed disease forms part of the national clinical outcomes strategy for COPD in the UK. It is currently the fourth leading cause of death1 and is projected to become the third leading cause by 2020.2 It is responsible for a large level of healthcare use, costing the UK National Health Service over £800 million per year.3 Much of the burden of COPD remains undetected,4,5 with estimates from prevalence studies suggesting that over 10% of the UK population aged above 35 years may have undiagnosed airflow obstruction6 compared with the diagnosed prevalence of 1.6%.7 There is a national drive in the UK to identify people with undiagnosed COPD so that they receive treatments that may benefit their symptoms and quality of life, and this forms part of the Outcomes Strategy for COPD and Asthma.8

There are a number of published studies of case finding for COPD in primary care from a variety of settings worldwide.9–11 However, they are of variable quality and mostly lack a comparator. Two systematic reviews12,13 conducted for the US Preventive Service Task Force looked at the use of spirometry for population screening for COPD, but these did not fully address the scope of the proposed review, were limited in their search strategy, and need updating. Furthermore, no systematic review protocols on case finding for COPD were identified in the PROSPERO database.14 There is therefore a need to review systematically the various approaches to case finding that have been studied in primary care, including their cost-effectiveness. Many of these approaches use screening questionnaires to identify which patients should undergo spirometry, each reporting different levels of test accuracy.9,15–18 One narrative review by van Schayck et al.19 compared existing symptom-based questionnaires but requires updating.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to summarise the different approaches to case finding for COPD studied in primary care, and their case finding yield. The review will also consider the cost-effectiveness of case finding and the test accuracy of screening questionnaires for COPD.

The review specifically aims to address the following questions about case finding for COPD in primary care:

What approaches to case finding have been studied?

What is the yield from case finding for each approach?

What is the most effective method of case finding?

What is the cost per case of COPD detected through case finding?

What is the test accuracy of screening questionnaires for COPD?

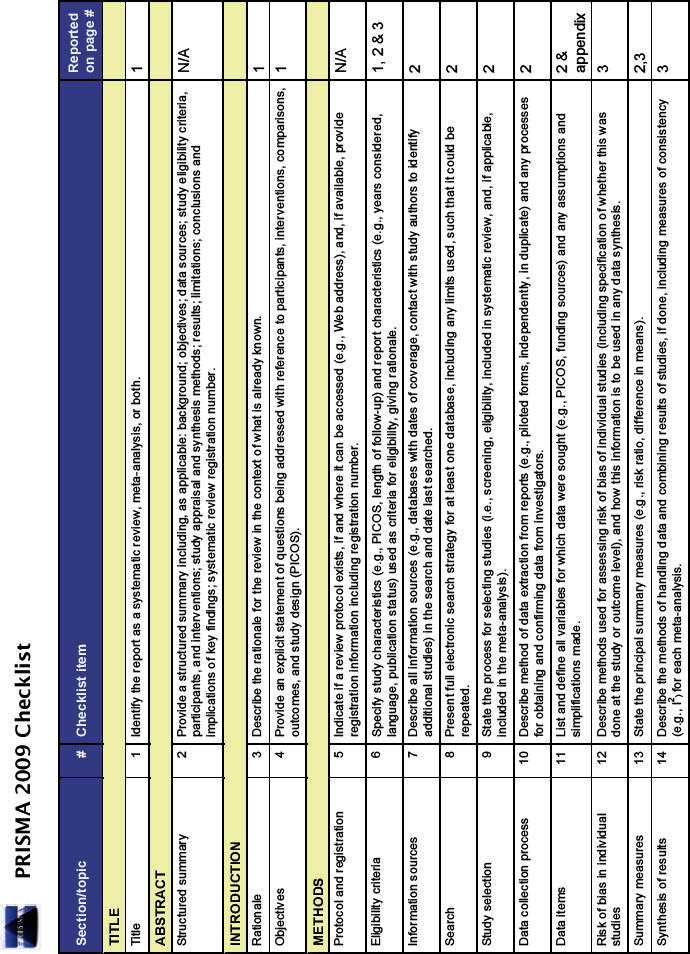

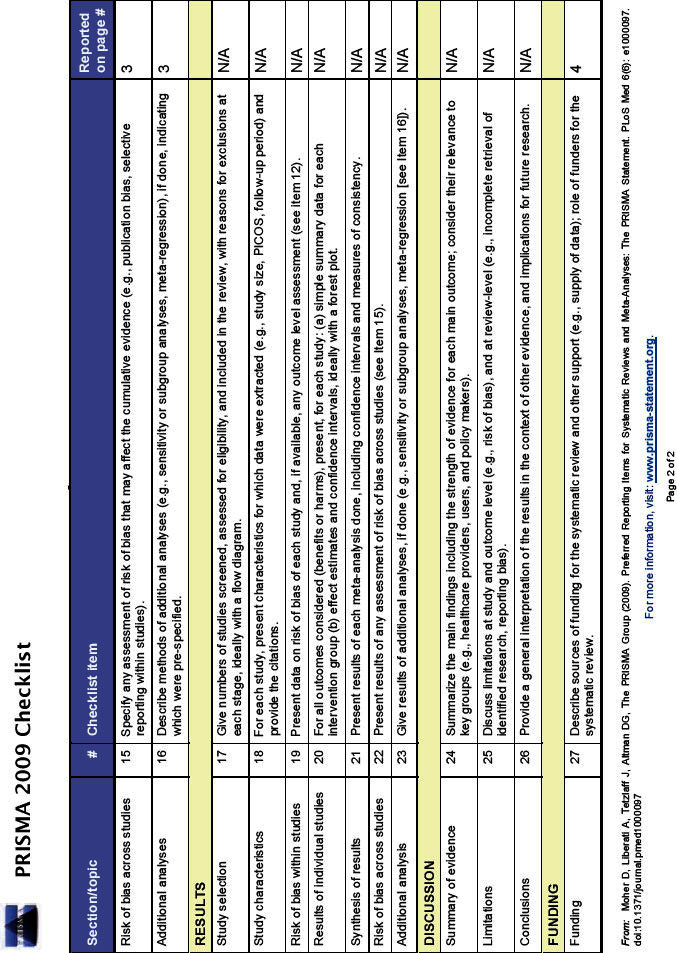

The review will be conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement.20 (see Appendix 1, available online at www.thepcrj.org)

Study criteria

Studies will be included in the review if they fulfil the following criteria:

Population

Individuals aged ≥35 years with no prior diagnosis of COPD, with or without a smoking history, in primary care. This includes individuals with other respiratory conditions such as asthma. Where possible, the populations will be subgrouped by age, smoking status (e.g. active smokers, ever smokers), and presence of symptoms.

Interventions

Questionnaires, clinical examination, spirometry, peak flow, decision aids/risk algorithms, and lung imaging (including chest x-ray and computed tomography), either alone or in combination.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest are derived from the number of new cases of spirometry-defined COPD identified and include:

Proportion of targeted patients identified with COPD

Cost per case of COPD detected

Sensitivity and negative predictive value of COPD screening questionnaires (these two measures of screening test accuracy have been prioritised as they reflect the ability of the questionnaire to exclude COPD)

The secondary outcomes are:

Positive predictive value of case finding interventions for COPD

Number-needed-to-screen to identify one individual with COPD

Specificity, positive predictive value, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and area under the curve of COPD screening questionnaires

Study designs

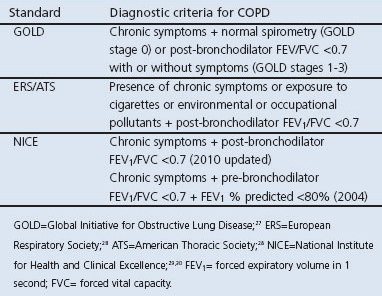

Randomised controlled trials, single arm trials, quasi-experimental and screening test accuracy studies will be considered eligible for inclusion if the studies confirm the diagnosis of COPD by spirometry according to either the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), European Respiratory Society (ERS), American Thoracic Society (ATS), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) or other nationally accepted criteria (Table 1). Economic evaluations will also be included.

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for COPD.

Methods

Search strategy

Bibliographic databases will be searched including Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), HTA Database and NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS EED). Studies in progress will be sought from trial registers including the UK Clinical Research Network, MetaRegister of Current Controlled Trials, UK International Clinical Research Network Portfolio (NIHR CRN), and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). Ongoing studies and other grey literature will also be sought from conference abstracts from the ERS, ATS, British Thoracic Society, Index of Scientific and Technical Proceedings, and the Conference Papers Index. Systematic reviews in progress will be sought from the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). A comprehensive search of relevant articles on the internet will be searched using Google Scholar, Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP), HTAi VORTAL and DogPile, limited to the first one hundred articles per search. Reference lists from relevant papers will be hand searched. Experts will be contacted to identify additional studies. Studies already known to the authors will also be included. There will be no language restrictions. The search will include studies published up to 15 years before the date of the search.

Search terms

Search terms will be used to broadly identify articles that examine case finding for COPD. This will include two main search term headings:

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive airways disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, COPD, COAD, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, airflow obstruction, airflow limitation (terms combined with OR)

Case finding: case finding, screening, early detection, secondary prevention, risk, spirometry, questionnaire, peak flow, chest X-ray, computed tomography, CT, decision aid, algorithm, sensitivity, specificity (terms combined with OR)

These search terms will be inputted as MESH or MESH-like terms and as free text.

Search terms will be combined as: COPD AND case finding.

The search strategy will be piloted on Medline and amended according to the number of articles produced and their relevance to the research questions.

Selection of relevant studies

A list of all citations and their abstracts will be produced. Articles will then be selected in two phases:

The first 10% of citations will be screened independently by two reviewers and included if they broadly fit with the inclusion criteria in order to maximise the sensitivity of the search. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion and through a third reviewer where agreement cannot be reached. The remaining 90% of citations will be screened by one reviewer. Articles will be included if their title or abstract suggests relevance to at least one of the five research questions.

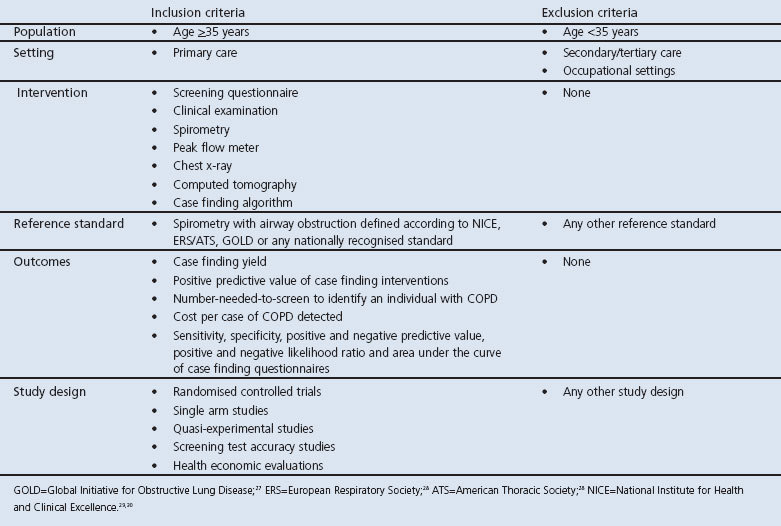

Full text versions of all included articles will then be screened for relevance independently by two reviewers using an explicit set of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Disagreements will be resolved through discussion and by a third reviewer where agreement cannot be reached.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection.

A log of included and excluded studies will be constructed at each stage of the study selection process.

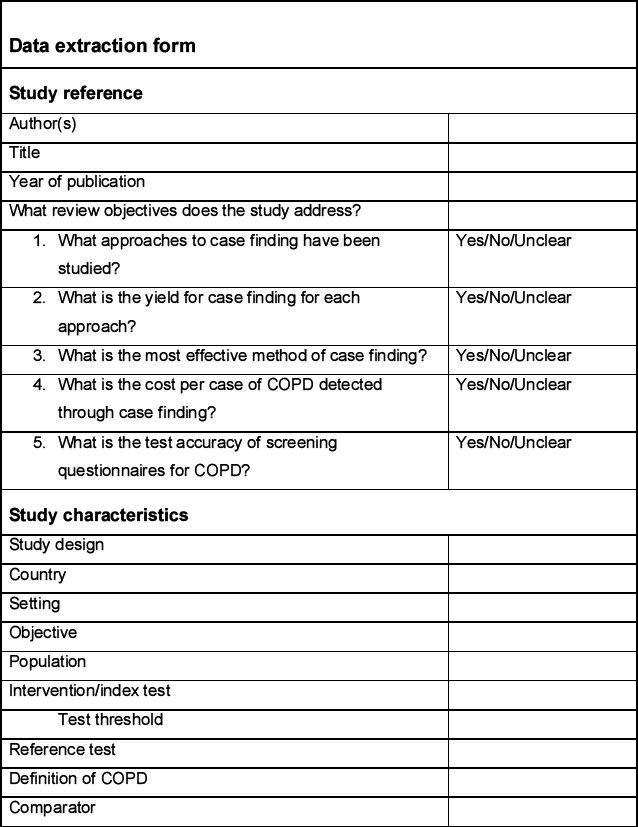

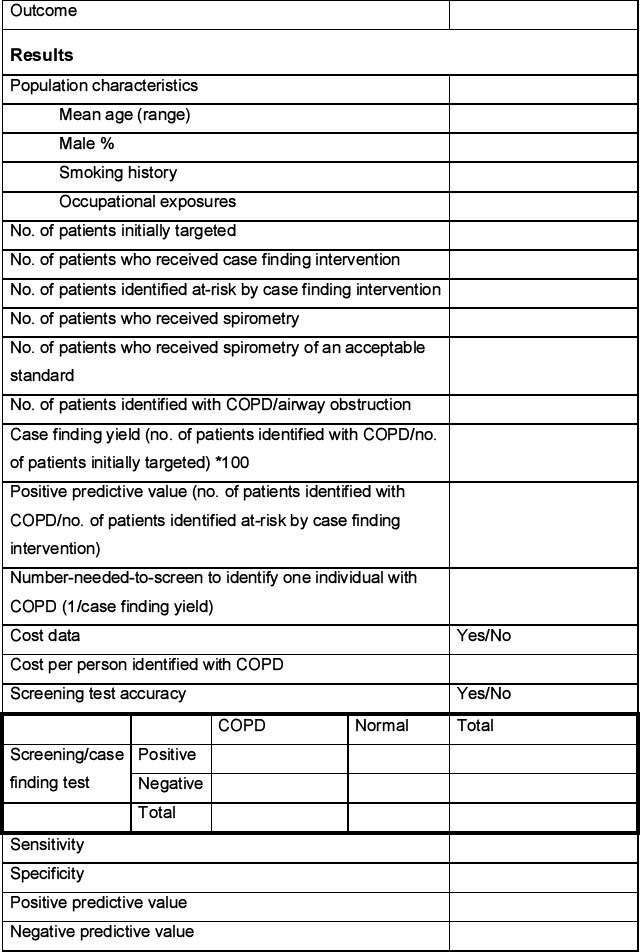

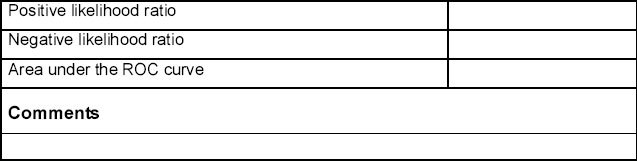

Data extraction

Data will be extracted from each included study by one reviewer using a predetermined data extraction form (see Appendix 2, available online at www.thepcrj.org) and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. This will include information on the population, intervention, comparator, study design, and specific outcome measures. Population characteristics of particular interest will include mean age, sex ratio, smoking history, and occupational exposures. The data extraction form will be piloted on at least two studies identified in the scoping search.

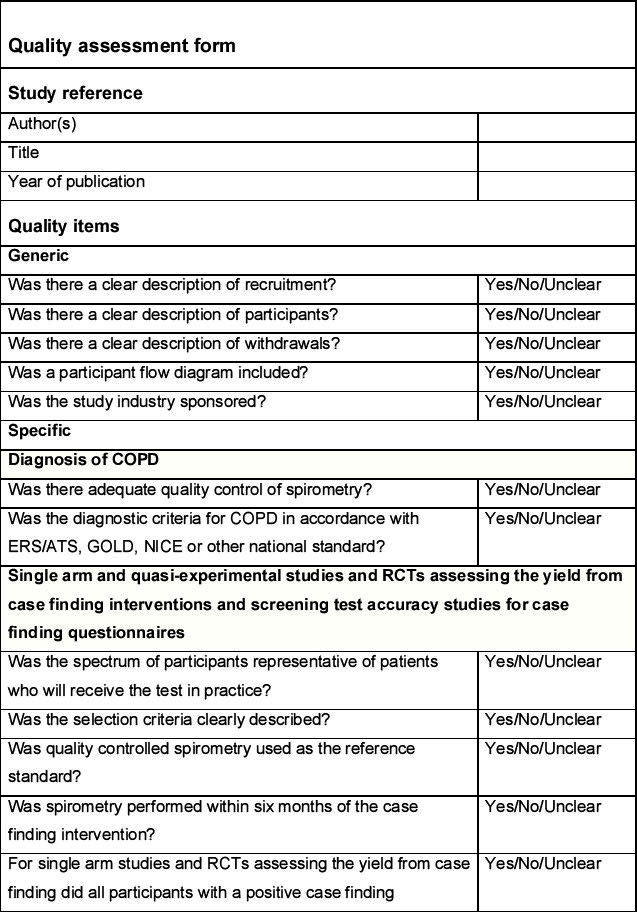

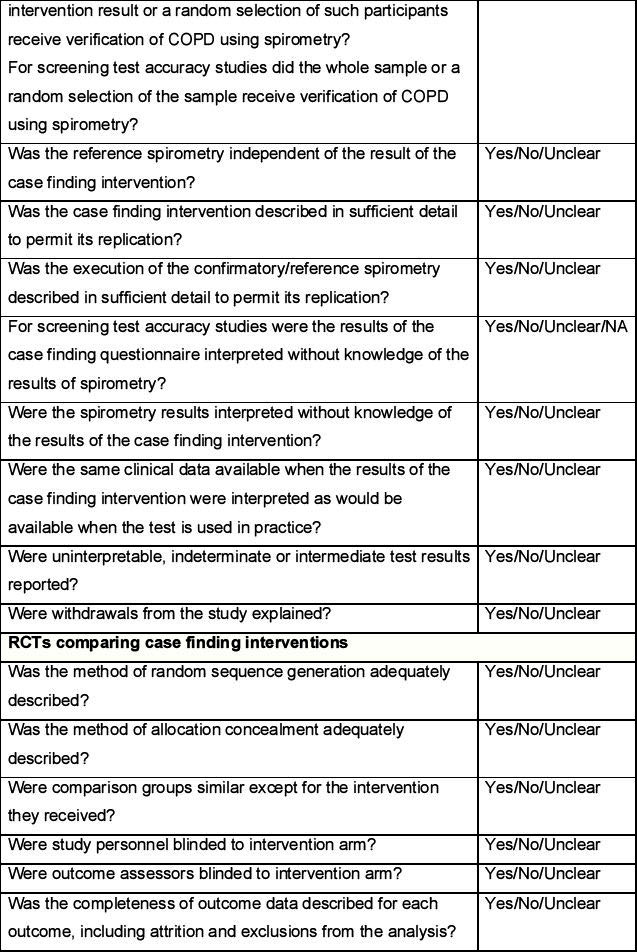

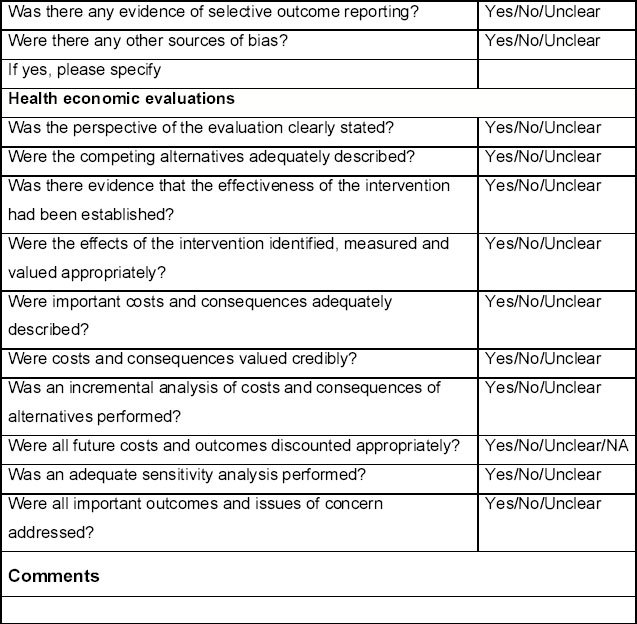

Quality assessment

The quality of studies assessing the yield from case finding interventions for COPD and the screening test accuracy of COPD case finding questionnaires will be assessed according to criteria adapted from the QUADAS and QUADAS-2 checklists.21 The quality of randomised controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of case finding interventions will be assessed according to criteria outlined in the Cochrane handbook22 as well as the QUADAS checklists.21 The quality of economic evaluations will be assessed according to items derived from the CHEC-List23 and Drummond.24 These items are listed in the Quality assessment form (see Appendix 3, available online at www.thepcrj.org).

The quality assessment will be conducted independently by two reviewers and disagreements resolved through discussion. Where consensus is not achieved, this will be resolved by a third reviewer. The quality assessment of each included study will be tabulated and a summary presented in a bar chart.

Risk of bias across studies

The case finding yield will be presented on separate funnel plots to assess the risk of bias across studies. The x-axis will include the proportion of individuals identified with COPD (p) and ln(p/[1-p]). These different scales have been chosen to account for the skew that will be induced by virtue of the case finding yield being a proportion, which cannot be less than one. The y-axis will include the number of individuals targeted and the inverse variance of p to reflect the size of the studies. An approximately symmetrical plot will be taken to indicate a reduced risk of bias across studies.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

The included studies will initially be described and analysed through a narrative systematic review. The case finding yield will be presented as the proportion of patients targeted through case finding who are identified with COPD. The number-needed-to-screen will be calculated as the reciprocal of the case finding yield. These will be sub-grouped by intervention, population, and definition of COPD. The case finding yields will be mathematically pooled where there is sufficient clinical and methodological homogeneity. A decision will then be made on whether to use a fixed or random effects model based on the level of heterogeneity identified amongst the included studies. However, a random effects model is more likely given the level of heterogeneity identified in the scoping review. This will be performed using REVMAN-Review Manager version 5.1. No attempt will be made to pool estimates of the positive predictive value and cost-effectiveness of case finding interventions, or the test accuracy of screening questionnaires.

Grading the overall quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

The overall quality of evidence and strength of recommendations will be graded according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.25,26 These will be summarised for each outcome using GRADEPro.

Acknowledgments

Handling editor Alan Crockett

Funding SMMH is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) doctoral fellowship. REJ is funded by an NIHR post-doctoral fellowship.

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42012002074

We would like to thank David Moore, Clare Davenport and Richard Riley for the advice they have provided on this protocol.

Appendix 1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist

Appendix 2.

Appendix 3.

Footnotes

SMMH and REJ are funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) which is currently funding a large randomised controlled trial of case finding for COPD in the West Midlands, UK as part of the Birmingham Lung Improvement Studies (BLISS) for which REJ and PAA are principal investigators.

References

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349(9064):1498–504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton M. The burden of COPD in the UK: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Respir Med 2003;97(Suppl C):S71–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0954-6111(03)80027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370(9589):741–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366(9500):1875–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab L, Jarvis MJ, Britton J, West R. Prevalence, diagnosis and relation to tobacco dependence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a nationally representative population sample. Thorax 2006;61(12):1043–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.064410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano JB, Maier WC, Egger P, et al. Recent trends in physician diagnosed COPD in women and men in the UK. Thorax 2000;55(9):789–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.55.9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. An Outcomes Strategy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Asthma. London: Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz ML, Yawn BP, Mannino DM, et al. Prevalence of airway obstruction assessed by lung function questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86(5):375–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ghobain M, Al-Hajjaj MS, Wali SO. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among smokers attending primary healthcare clinics in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31(2):129–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.77485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantikaki V, Kostikas K, Minas M, et al. Comparison of a network of primary care physicians and an open spirometry programme for COPD diagnosis. Respir Med 2011;105(2):274–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Watkins B, Johnson T, Rodriguez JA, Barton MB. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(7):535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilt T, Niewoehner D, Kim C, et al. Use of spirometry for case finding, diagnosis, and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, National Institute for Health Research, 2012.

- Hanania NA, Mannino DM, Yawn BP, et al. Predicting risk of airflow obstruction in primary care: Validation of the lung function questionnaire (LFQ) Respir Med 2010;104(8):1160–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Tejima T, Moritani Y, Matuzaki Y, Uchimura K, Aoki M. [The usefulness of COPD questionnaire for screening COPD subjects]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 2009;47(11):971–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FJ, Raczek AE, Seifer FD, et al. Development and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS). COPD 2008;5(2):85–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15412550801940721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Nordyke RJ, Isonaka S, Halbert RJ. Scoring system and clinical application of COPD diagnostic questionnaires. Chest 2006;129(6):1531–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.6.1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schayck CP, Halbert RJ, Nordyke RJ, Isonaka S, Maroni J, Nonikov D. Comparison of existing symptom-based questionnaires for identifying COPD in the general practice setting. Respirology 2005;10(3):323–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Dinnes J, Reitsma J, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. Development and validation of methods for assessing the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8(25):iii, 1–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green SP. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184 [Google Scholar]

- Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21(2):240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008;336(7653):1106–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2011.

- ERS/ATS. Standards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD. New York/Lausanne, 2004.

- NICE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax 2004;59(Suppl 1):1–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care (partial update). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010. [Google Scholar]