Abstract

Objectives

There are country and regional variations in the prevalence of hyperuricaemia (HUA). The prevalence of HUA and non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) in southern China is unknown.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting and participants

A total of 11 488 permanent residents aged 35 or older from urban and rural areas of Guangzhou, China were enrolled. A questionnaire was used to compile each participant’s demographic information and relevant epidemiological factors for HUA and NVAF. All participants were assessed using a panel of blood tests and single-lead 24-hour ECG.

Main outcome measures

HUA was defined as serum uric acid level >420 μmol/L in men and >360 μmol/L in women. NVAF was diagnosed as per guidelines.

Results

The prevalence of HUA was 39.6% (44.8% in men and 36.7% in women), and 144 residents (1.25%) had NVAF. Prevalence of HUA increased with age in women but remained stably high in men. After adjusting for potential confounders, age, living in urban areas, alcohol consumption, central obesity, elevated fasting plasma glucose level, elevated blood pressure, lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and elevated triglycerides level were associated with increased risk of HUA. Residents with HUA were at higher risk for NVAF. Serum uric acid level had a modest predictive value for NVAF in women but not men.

Conclusions

HUA was highly prevalent among citizens of southern China and was a predictor of NVAF among women.

Keywords: cardiac epidemiology, epidemiology, cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cross-sectional population-based study investigated the prevalence of hyperuricaemia and its impact on that of non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

A large cohort from urban and rural areas of Guangzhou was studied.

The surveyed areas were all randomised to increase reliability.

Residents aged under 35 years were not included.

The results of this cross-sectional study need to be validated in prospective studies.

Introduction

The prevalence of hyperuricaemia (HUA) ranges from 13.3% to 21.6% and varies by sex and among countries or regions.1 2 Local differences are apparent within countries, likely influenced by environmental, climatic, economic status and especially dietary habits variations.3 4 Although several epidemiological studies reported an association between serum uric acid (SUA) level and cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, vascular dementia, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cerebrovascular disease and kidney disease, it was not apparent in others such as the Framingham Heart Study.5

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common clinical cardiac arrhythmia, contributes to increased morbidity and mortality especially in the setting of other cardiovascular risk factors.6 AF disease burden is estimated to reach 9 million cases by 2050 in China,7 with the increasing prevalence of AF being a global health problem.8 9 HUA has been associated with AF10–13; however, prevalence of HUA and its potential association with that of non-valvular AF (NVAF) in the typical southern Chinese city of Guangzhou with its particular combination of dietary habits, economic status and climate remain undefined.

The present cross-sectional population-based study aimed to assess the prevalence of HUA and its association with NVAF among Guangzhou residents.

Materials and methods

Study population

We conducted a cardiovascular epidemiological survey (the Guangzhou Heart Study) from July 2015 to August 2017 in Guangzhou. Randomised multistage cluster sampling was used in this study. We divide all the 11 districts in Guangzhou into two groups: urban group (Yuexiu, Haizhu, Liwan, Tianhe and Huangpu districts) and rural group (Baiyun, Panyu, Nansha, Huadu, Conghua and Zengchen districts). Sealed envelopes with the names of all the districts written on pieces of paper were prepared before the selection. Then, we randomly selected one envelope from each group. Yuexiu district was selected to represent the urban places while Panyu district was chosen for the rural regions. We selected Xinzao Town, Nancun Town and Xiaoguwei Street to conduct the survey in Panyu district using the same earlier methods while Dadong Street and Baiyun Street were chosen in Yuexiu district. Finally, in the same way, 7 residential committees in Dadong Street and Baiyun Street and 17 village committees in Xinzao Town, Nancun Town and Xiaoguwei Street based on population size. Every subject who was eligible to fit the inclusive criteria in Yuexiu and Panyu districts was all included for the study.

The residents in the study sites were invited to participate in this study by 3-round mobilisation via door-to-door visits or telephone appointments. For the first-round mobilisation, we made appointments for the survey from door to door. Responsive information was collected to identify who were eligible to join the survey and within the eligible subjects who were willing, reluctant or indecisive to come. In the second-round mobilisation, we promoted the residents who were not connected in the same way. At the same time, we continued to have telephone appointments for people who were willing or indecisive to join the survey but had not come yet and collected the responsive information. During the last round of the mobilisation, we mainly made telephone appointments for the eligible rest of the list who still did not come and sum up the latest responsive information. Residents were enrolled if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) registered in the Guangzhou Household Register; (2) aged 35 years or older and (3) living in the selected communities for at least 6 months by the day they participated in the survey. Residents were excluded if they had any of the following conditions: (1) mental or cognitive disorders including dementia, disturbance of understanding and deaf-mutters; (2) mobility difficulties including paraplegia; (3) pregnant or lactating women; (4) malignant tumours under treatment; (5) temporary residents including renters or (6) non-responders during the 3-round mobilisation.

Data collection

A structured and interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to survey each participant’s demographic information, medical history, social habits, family history and emotional status. Physical examination including measurement of waist circumference, height, weight, blood pressure (BP), heart rate and body fat was performed using standard instruments and protocols. Blood samples were collected and tested following standardised procedures by an authorised medical laboratory. ECG and 24-hour single-lead ECG were recorded for each participant and reports were assessed by two independent cardiologists; methodological details were as reported by Deng et al.14 A total of 29 196 residents were eligible for inclusion, of whom 12 013 residents participated in the study; the response rate was therefore 41.16%.

Cohort definition

Subjects were diagnosed with NVAF if they met any of the following criteria: (1) AF pattern in ECG screening; (2) no AF in ECG screening but positive AF history; and (3) AF episodes in 24-hour single-lead ECG recording. All residents with AF underwent cardiac ultrasonography to assess for valvular AF. NVAF was diagnosed as per guidelines.6 ECG and single-lead 24-hour ECG recordings were performed by well-trained physicians, and AF diagnosis was made by two specific electrophysiological experts. HUA was defined as SUA level >420 μmol/L in men and >360 μmol/L in women. The MetS was defined as having at least three out of the five following characteristic signs7: abdominal obesity (defined as waist circumference ≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women); elevated triglycerides (TG) level: >150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L), or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol: <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in men and <50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in women, or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; elevated BP: systolic BP >130 mm Hg or diastolic BP >85 mm Hg, or treatment for previously diagnosed hypertension; and elevated fasting plasma glucose (FPG): FPG >100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L), or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Patient and public involvement

Residents were not involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures. All residents were informed of their right to enquire about their data and test results. If residents were diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, they were notified by phone to present themselves to Guangdong General Hospital for further treatment.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD and categorical variables as number (percentage). Comparisons between groups were made using the Student t-test or χ2 tests, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to investigate the risk factors for HUA and the associations between the prevalence of NVAF and HUA. ORs and corresponding 95% CI were calculated to assess the associations. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to calculate the predictive value of SUA and HUA for NVAF. SAS software V.9.3 (SAS Institute) was used for the statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p<0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

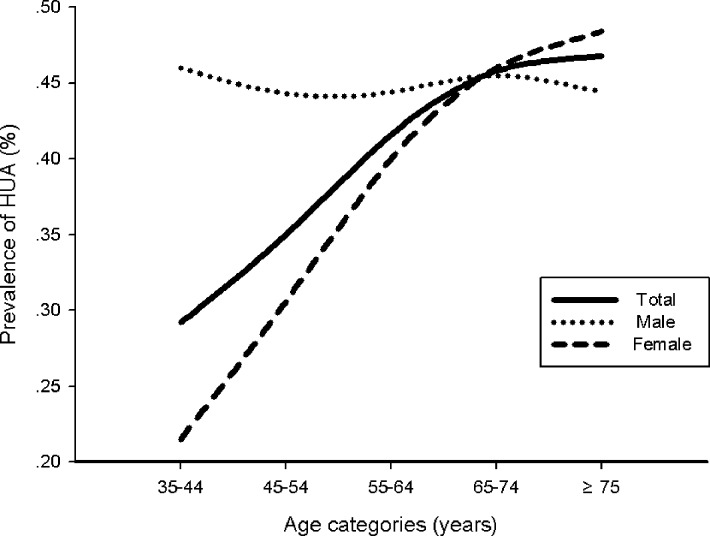

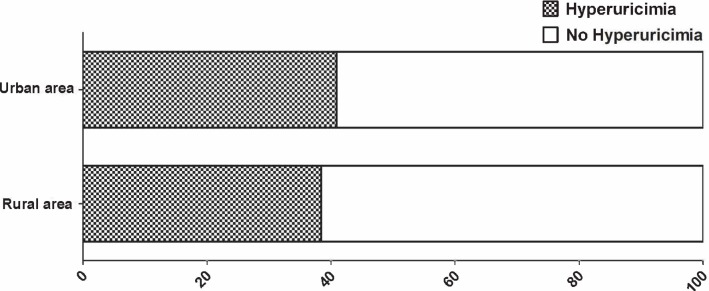

A total of 12 013 patients were enrolled in the study; 175 patients had AF, which was of valvular origin in 31. A total of 494 patients refused to have a blood test., and therefore 11 488 patients were included in the statistical analysis. The prevalence of HUA was 39.6% (44.8% in men and 36.7% in women, table 1). Prevalence of HUA increased with age in women but maintained a steady high level in men (figure 1). The prevalence of HUA in urban areas was higher than in rural areas (40.9% vs 38.6%, respectively, p=0.003, figure 2). Based on medical history, the proportion of men with HUA was significantly higher than that of women. Residents with HUA were significantly older. Regardless of gender, abdominal circumference and body mass index were significantly greater in residents with HUA. A higher proportion of NVAF, Hypertension (HTN), Diabetes mellitus (DM), central obesity, and stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA) were observed in residents with HUA. In laboratory testing, haemoglobin (HGB), platelet (PLT) count, red blood cell (RBC) count and levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), cholesterol (CHOL) and FPG were significantly higher while those of creatinine and HDL were significantly lower in residents with HUA. Significant larger proportion of reduced HDL cholesterol, elevated TG level and MetS were observed in residents with HUA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of residents with or without HUA

| Total (n=11 488) |

HUA (n=4547) |

No HUA (n=6941) |

P value | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Male (n, %) | 4047 (35.2) | 1814 (39.9) | 2233 (32.2) | <0.01 |

| Age (years) | 58.22±11.74 | 59.98±11.44 | 57.06±11.79 | <0.01 |

| Urban (n, %) | 5403 (46.9) | 2210 (48.6) | 3193 (46.0) | 0.01 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 130.51±20.52 | 134.16±20.39 | 128.13±20.25 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80.70±11.61 | 82.30±11.60 | 79.62±11.49 | <0.01 |

| Non-valvular AF (n, %) | 144 (1.3) | 91 (2.0) | 53 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 3377 (29.4) | 1744 (38.4) | 1633 (23.5) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 1050 (9.1) | 528 (11.6) | 522 (7.5) | <0.01 |

| Elevated BP (n, %)* | 6698 (58.3) | 3092 (68.0) | 3606 (52.0) | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.01±3.55 | 25.08±3.55 | 23.32±3.37 | <0.01 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 84.41±10.10 | 87.69±9.61 | 82.26±9.83 | <0.01 |

| Male | 84.41±10.11 | 87.71±9.63 | 82.26±9.83 | <0.01 |

| Female | 82.76±9.98 | 86.36±9.64 | 80.66±9.56 | <0.01 |

| Central obesity (n, %)† | 6183 (53.8) | 2984 (65.6) | 3199 (46.1) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure (n, %) | 114 (1.0) | 50 (1.1) | 64 (0.9) | 0.39 |

| Stroke/TIA (n, %) | 274 (2.4) | 128 (2.8) | 146 (2.1) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol consumption (n, %) | 2467 (21.5) | 1060 (23.3) | 1391 (20.0) | <0.01 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 2451 (21.3) | 1114 (24.5) | 1353 (19.5) | <0.01 |

| Laboratory examinations | ||||

| HGB (g/L) | 138.74±14.07 | 140.14±14.11 | 137.83±13.97 | <0.01 |

| PLT (109/L) | 243.78±60.67 | 245.42±61.76 | 242.71±59.93 | 0.019 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 4.76±0.64 | 4.80±0.65 | 4.73±0.63 | <0.01 |

| HDL cholesterol(mmol/L) | 1.49±0.55 | 1.36±0.51 | 1.58±0.56 | <0.01 |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol (n, %)‡ | 2589 (22.5) | 1369 (30.1) | 1220 (17.6) | <0.01 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.64±1.03 | 3.72±1.04 | 3.58±1.01 | <0.01 |

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 5.486±1.13 | 5.57±1.17 | 5.42±1.11 | <0.01 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.696±1.43 | 1.47±1.06 | 2.05±1.18 | <0.01 |

| Raised TG level (n, %)§ | 3787 (33.0) | 2140 (47.1) | 1647 (23.7) | <0.01 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.586±1.57 | 5.69±1.52 | 5.51±1.60 | <0.01 |

| Elevated FPG (n, %)¶ | 3375 (29.4) | 1653 (36.4) | 1722 (24.8) | <0.01 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 367.20±98.39 | 460.60±72.77 | 306.01±55.62 | <0.01 |

| Male | 367.00±98.30 | 460.60±72.70 | 306.01±55.63 | <0.01 |

| Female | 340.76±89.40 | 434.37±64.43 | 286.30±46.52 | <0.01 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 76.89±25.45 | 83.78±33.25 | 72.36±17.22 | <0.01 |

*Elevated BP was defined as systolic BP >130 or diastolic BP >85 mm Hg or history of hypertension.

†Central obesity was defined as waist circumference >85 cm for men and >80 cm for women.

‡Reduced HDL was defined as HDL <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in men or <50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in women or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality.

§Raised TG level was defined as TG >150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality.

¶Elevated FPG was defined as fasting plasma glucose >100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CHOL, cholesterol; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HGB, haemoglobin; HUA, hyperuricaemia; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; TG, triglycerides; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Figure 1.

Differential prevalence of hyperuricaemia (HUA) among men and women across 10-year age intervals starting at 35.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of hyperuricaemia in urban and rural areas.

Analysis of prevalence risk of HUA

We performed logistic regression analyses to evaluate the risk factors for HUA (table 2). After adjusting for possible confounders, age (per 10 years, OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.14), living region (urban, OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.25), alcohol consumption (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.24), central obesity (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.67 to 1.99), elevated FPG (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.29), elevated BP (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.46), reduced HDL (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.71) and elevated TG level (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.97 to 2.35) were strongly associated with risk for HUA.

Table 2.

Analysis of prevalence risk of HUA in multiple logistic regression model

| Model* | ORs | 95% CI | P value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.10 | 1.06 to 1.14 | <0.01 |

| Living area (urban) | 1.15 | 1.06 to 1.25 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.12 | 1.01 to 1.24 | 0.03 |

| Central obesity† | 1.82 | 1.67 to 1.99 | <0.01 |

| Elevated FPG‡ | 1.18 | 1.08 to 1.29 | <0.01 |

| Elevated BP§ | 1.34 | 1.22 to 1.46 | <0.01 |

| Reduced HDL¶ | 1.27 | 1.15 to 1.41 | <0.01 |

| Raised TG level** | 2.14 | 1.96 to 2.35 | <0.01 |

*Adjusted risk factors: age (per 10 years), living region, education level, marriage status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, central obesity, elevated FPG, elevated BP, reduced HDL, raised TG level.

†Central obesity was defined as waist circumference >85 cm for men and >80 cm for women.

‡Elevated FPG was defined as fasting plasma glucose >100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

§Elevated BP was defined as systolic BP >130 mm Hg or diastolic BP >85 mm Hg or history of hypertension.

¶Reduced HDL was defined as HDL <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in men or <50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in women or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality.

**Raised TG level was defined as triglycerides >150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality.

BP, blood pressure,; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides.

Predictive value of HUA on non-valvular AF

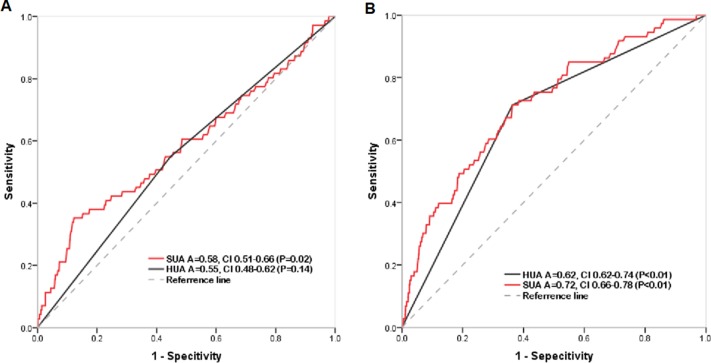

The adjusted multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that age (per 10 years) (OR 2.31, CI 1.93 to 2.78), female gender (OR 2.21, CI 1.45 to 3.36), central obesity (OR 1.93, CI 1.29 to 2.90, p<0.01), HUA (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.53 to 3.12) and history of heart failure (OR 5.13, CI 2.52 to 10.43) were risk factors for AF prevalence (table 3). ROC curves were generated for SUA by gender to determine its diagnostic capability for NVAF. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for SUA was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.79 to 0.91) in women and 0.58 (95% CI: 0.51 to 0.62) in men (figure 3).

Table 3.

Increasing OR for non-valvular atrial fibrillation with HUA

| Variables* | ORs | 95% CI | P value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 2.31 | 1.93 to 2.78 | <0.01 |

| Gender (female) | 2.21 | 1.45 to 3.36 | <0.01 |

| Central obesity | 1.93 | 1.29 to 2.87 | <0.01 |

| HUA | 2.19 | 1.53 to 3.12 | <0.01 |

| Heart failure | 5.13 | 2.53 to 10.43 | <0.01 |

*Adjusted risk factors: age (per 10 years), gender, heart failure, smoking status, alcohol consumption, central obesity, elevated FPG, elevated BP, reduced HDL, raised TG level and HUA.

BP, blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein, HUA, hyperuricaemia; TG, triglycerides.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for determination of predictive value of hyperuricaemia (HUA) or serum uric acid (SUA) for atrial fibrillation in men (A) and women (B). Area under curve.

Discussion

The present study had three main findings. First, the prevalence of HUA was 39.6% (44.8% in men and 36.7% in women) with sex related differences in residents with HUA. Second, the age, living in urban, alcohol consumption, central obesity, elevated FPG, elevated BP, reduced HDL and elevated TG level were strongly associated with risk of HUA. Third, residents with HUA had a markedly increased risk of NVAF, and SUA had moderate predictive value for NVAF only in women.

Prevalence of HUA

Regional differences in prevalence of HUA have been reported. According to Liu’s review,15 the prevalence of HUA in mainland China from 2000 to 2014 was 13.3% (19.4% in men and 7.9% in women). In Chinese publications, prevalence of HUA in Guangdong province ranged from 15% to 20%.15 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the USA documented a 21.2% HUA prevalence in men and 21.6% in women2 which was similar to that in Japan and Taiwan.16 17 In this study, the prevalence of HUA in Guangzhou area was 39.6% (44.8% in men and 36.7% in women), which was considerably higher than that in previous reports. The traditional dietary habits of Guangzhou residents might be one of the important reasons. Sex related differences in HUA prevalence also were observed in our study. The prevalence of HUA increased with age in women while remaining at a steady high level in men regardless of age. A rapidly increasing prevalence of HUA in women older than 55 years was observed; the prevalence was similar to or even higher than that of men after 65 years of age. The latter finding might reflect greatly decreased oestrogen level in postmenopausal women.18 Oestrogen might promote excretion of SUA via its effect on post-secretory tubular reabsorption of SUA, as confirmed by the effectiveness of hormone replacement therapy in reducing SUA.19 20

Risk factors of HUA

Due to the increasing prevalence of HUA, it is of great clinical significance to search for its risk factors. Risk factors for HUA might vary among ethnic groups. In this study, age, alcohol consumption, central obesity, elevated FPG, elevated BP, reduced HDL and elevated TG level were strongly associated with the risk of HUA. Previous studies showed that hypertriglyceridemia was strongly associated with risk of HUA.21 Consistent with our study, the Seychelles Heart Study II documented that high serum TG level was the strongest predictor of HUA.22 The mechanism of hypertriglyceridemia leading to HUA might be related to lifestyle22 or genetic factors.23 Central obesity, elevated FPG, elevated BP, reduced HDL and elevated TG level are all diagnostic components of MetS; therefore, HUA was closely related to MetS. Yuan’s study showed that MetS was 10 times higher in individuals with SUA ≥10 mg/dL than in adults with SUA <6 mg/dL and normal body mass index.24 A meta-analysis of more than 54 000 participants showed that elevated SUA was associated with increased risk of MetS.25 SUA and MetS often accompany each other and promote the occurrence of cardiovascular disease.

HUA and non-valvular AF

HUA showed a strong relationship with AF in our study. As reported previously, HUA was associated with endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, abnormal high levels of inflammatory markers and insulin resistance.26–28 In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study,29 HUA was associated with a greater risk of new onset AF. In contrast to our study, the ARIC study enrolled patients aged 45 to 64 years. Another study from Taiwan30 showed that SUA significantly correlated with left atrial diameter and that HUA was a significant risk factor for new onset AF in multivariable Cox regression analysis; however, HUA was diagnosed only when individuals suffered from a gout attack, while in the present study asymptomatic patients were not excluded and uric acid (UA) metabolism status of residents was assessed by measuring blood UA levels in the fasting state. A recent Chinese report also showed that HUA increased AF risk by twofold among elderly southwestern residents.31 Only 7.6% AF residents in the latter study presented with HUA while 63.2% did not so in the present study cohort. Mechanisms underlying the association between UA level and AF remain unclear; however, elevated UA has been associated with vasoconstriction, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, local inflammation and insulin resistance.32

Differences in cardiovascular events rates by gender have been reported.33 In the study by Suzuki and the ARIC study, elevated SUA was associated with a higher risk of AF, particularly in women. Both SUA and HUA had moderate predictive value for AF in the present study. It is worth noting that SUA had higher AUC than HUA, which indicates a better predictive value for AF for continuous rather than a cut-off for UA. As reported previously, the relationship between UA and cardiovascular disease is apparent with normal to high UA serum level (310–330 μmol/L)34–36; each 1 mg/mL increase in UA level was associated with 12% to 20% increase in the risk for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, respectively.37 Therefore, UA level might be strongly associated with AF. The bases for sex related differences in HUA and AF remain unknow. HUA has been associated with endothelial dysfunction in postmenopausal women, suggesting that HUA could be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease including AF, particularly among postmenopausal women.38

Limitations

The present study is limited by its cross-sectional design, warranting prospective studies with appropriate follow-up to validate findings, and lack of inclusion of residents aged under 35 years whose HUA prevalence remains unknown.

Conclusions

This large-scale cross-sectional study demonstrated a high prevalence of HUA with sex related differences among Guangzhou residents. Increasing age, living in an urban setting, alcohol consumption and components of MetS increase the risk of HUA. Residents with HUA had a markedly increased risk for AF and the UA level had moderate predictive value for NVAF only in women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the residents involved in this study for their cooperation.

Footnotes

W-dL and HD contributed equally.

Contributors: W-dL, HD, YX and S-lW conceived the study, analysed data, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. PG, RC, FL, XF, XZ, HoL, WH, YL, FW, MZ, HuL, JH and WW collected data and completed the survey.

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81370295), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (No. 201508020261 and No. 2014Y200196), Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2017A020215054) and Science and Technology Planning of Guangzhou City, China (No. 2014B070705005).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Guangzhou Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese Medical Association (No. GDREC2015306H) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. B L, T W, Hn Z, et al. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in China: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2011;11:832 10.1186/1471-2458-11-832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3136–41. 10.1002/art.30520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strasak A, Ruttmann E, Brant L, et al. Serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular mortality: a prospective long-term study of 83,683 Austrian men. Clin Chem 2008;54:273–84. 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ndrepepa G. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta 2018;484:150–63. 10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1811–21. 10.1056/NEJMra0800885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014;130:2071–104. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hajhosseiny R, Matthews GK, Lip GY. Metabolic syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and stroke: Tackling an emerging epidemic. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:2332–43. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, et al. Acute stroke with atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke 1996;27:1765–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friberg J, Buch P, Scharling H, et al. Rising rates of hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation. Epidemiology 2003;14:666–72. 10.1097/01.ede.0000091649.26364.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suzuki S, Sagara K, Otsuka T, et al. Gender-specific relationship between serum uric acid level and atrial fibrillation prevalence. Circ J 2012;76:607–11. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tamariz L, Hernandez F, Bush A, et al. Association between serum uric acid and atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:1102–8. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu X, Du N, Wang R, et al. Hyperuricemia is independently associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol 2015;184:699–702. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y, Xia Y, Han X, et al. Association between serum uric acid and atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional community-based study in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e19037 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng H, Guo P, Zheng M, et al. Epidemiological Characteristics of Atrial Fibrillation in Southern China: Results from the Guangzhou Heart Study. Sci Rep 2018;8:17829 10.1038/s41598-018-35928-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu R, Han C, Wu D, et al. Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and Gout in Mainland China from 2000 to 2014: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–12. 10.1155/2015/762820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagahama K, Iseki K, Inoue T, et al. Hyperuricemia and cardiovascular risk factor clustering in a screened cohort in Okinawa, Japan. Hypertens Res 2004;27:227–33. 10.1291/hypres.27.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chuang SY, Lee SC, Hsieh YT, et al. Trends in hyperuricemia and gout prevalence: Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan from 1993-1996 to 2005-2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guan S, Tang Z, Fang X, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia among Beijing post-menopausal women in 10 years. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016;64:162–6. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antón FM, García Puig J, Ramos T, et al. Sex differences in uric acid metabolism in adults: evidence for a lack of influence of estradiol-17 beta (E2) on the renal handling of urate. Metabolism 1986;35:343–8. 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90152-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sumino H, Ichikawa S, Kanda T, et al. Reduction of serum uric acid by hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with hyperuricaemia. Lancet 1999;354:650 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)92381-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu CS, Li TC, Lin CC. The epidemiology of hyperuricemia in children of Taiwan aborigines. J Rheumatol 2003;30:841–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chełchowska M, Ambroszkiewicz J, Gajewska J, et al. [The effect of tobacco smoking during pregnancy on concentration of uric acid in matched-maternal cord pairs]. Przegl Lek 2007;64:667–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hakoda M. [Epidemiology of hyperuricemia and gout in Japan]. Nihon Rinsho 2008;66:647–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. Am J Med 2007;120:442–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yuan H, Yu C, Li X, et al. Serum Uric Acid Levels and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:4198–207. 10.1210/jc.2015-2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Ble A, et al. Uric acid and inflammatory markers. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1174–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Papežíková I, Pekarová M, Kolářová H, et al. Uric acid modulates vascular endothelial function through the down regulation of nitric oxide production. Free Radic Res 2013;47:82–8. 10.3109/10715762.2012.747677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krishnan E, Pandya BJ, Chung L, et al. Hyperuricemia in young adults and risk of insulin resistance, prediabetes, and diabetes: a 15-year follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:108–16. 10.1093/aje/kws002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tamariz L, Agarwal S, Soliman EZ, et al. Association of serum uric acid with incident atrial fibrillation (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities [ARIC] study). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1272–6. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chao TF, Hung CL, Chen SJ, et al. The association between hyperuricemia, left atrial size and new-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:4027–32. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang G, Xu RH, Xu JB, et al. Hyperuricemia is associated with atrial fibrillation prevalence in very elderly - a community based study in Chengdu, China. Sci Rep 2018;8:12403 10.1038/s41598-018-30321-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ndrepepa G. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta 2018;484:150–63. 10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker JF, Krishnan E, Chen L, et al. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: recent developments, and where do they leave us? Am J Med 2005;118:816–26. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia in childhood primary hypertension. Hypertension 2003;42:247–52. (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085858.66548.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakagawa T, Tuttle KR, Short RA, et al. Hypothesis: fructose-induced hyperuricemia as a causal mechanism for the epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2005;1:80–6. 10.1038/ncpneph0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niskanen LK, Laaksonen DE, Nyyssönen K, et al. Uric acid level as a risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in middle-aged men: a prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1546–51. 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang R, Song Y, Yan Y, et al. Elevated serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in people with suspected or definite coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2016;254:193–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maruhashi T, Nakashima A, Soga J, et al. Hyperuricemia is independently associated with endothelial dysfunction in postmenopausal women but not in premenopausal women. BMJ Open 2013;3:e3659 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.