Abstract

Maternally transmitted Wolbachia bacteria infect about half of all insect species. Many Wolbachia cause cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), reduced egg hatch when uninfected females mate with infected males. Although CI produces a frequency-dependent fitness advantage that leads to high equilibrium Wolbachia frequencies, it does not aid Wolbachia spread from low frequencies. Indeed, the fitness advantages that produce initial Wolbachia spread and maintain non-CI Wolbachia remain elusive. wMau Wolbachia infecting Drosophila mauritiana do not cause CI, despite being very similar to CI-causing wNo from D. simulans (0.068% sequence divergence over 682,494 bp), suggesting recent CI loss. Using draft wMau genomes, we identify a deletion in a CI-associated gene, consistent with theory predicting that selection within host lineages does not act to increase or maintain CI. In the laboratory, wMau shows near-perfect maternal transmission; but we find no significant effect on host fecundity, in contrast to published data. Intermediate wMau frequencies on the island Mauritius are consistent with a balance between unidentified small, positive fitness effects and imperfect maternal transmission. Our phylogenomic analyses suggest that group-B Wolbachia, including wMau and wPip, diverged from group-A Wolbachia, such as wMel and wRi, 6–46 million years ago, more recently than previously estimated.

Keywords: host-microbe interactions, introgression, maternal transmission, mitochondria, spatial spread, WO phage

INTRODUCTION

Maternally transmitted Wolbachia infect about half of all species throughout all major insect orders (Werren and Windsor 2000; Zug and Hammerstein 2012; Weinert et al. 2015), as well as other arthropods (Jeyaprakash and Hoy 2000; Hilgenboecker et al. 2008) and nematodes (Taylor et al. 2013). Host species may acquire Wolbachia from common ancestors, from sister species via hybridization and introgression, or horizontally (O’Neill et al. 1992; Rousset and Solignac 1995; Huigens et al. 2004; Baldo et al. 2008; Raychoudhury et al. 2009; Gerth and Bleidorn 2016; Schuler et al. 2016; Turelli et al. 2018). Wolbachia often manipulate host reproduction, inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) and male killing in Drosophila (Laven 1951; Yen and Barr 1971; Hoffmann et al. 1986; Hoffmann and Turelli 1997; Hurst and Jiggins 2000). CI reduces egg hatch when Wolbachia-uninfected females mate with infected males. Three parameters usefully approximate the frequency dynamics and equilibria of CI-causing Wolbachia that do not distort sex ratios: the relative hatch rate of uninfected eggs fertilized by infected males (H), the fitness of infected females relative to uninfected females (F), and the proportion of uninfected ova produced by infected females (μ) (Caspari and Watson 1959; Hoffmann et al. 1990). To spread deterministically from low frequencies, Wolbachia must produce F(1 – μ) > 1, irrespective of CI. Once they become sufficiently common, CI-causing infections, such as wRi-like Wolbachia in Drosophila simulans and several other Drosophila (Turelli et al. 2018), spread to high equilibrium frequencies, dominated by a balance between CI and imperfect maternal transmission (Turelli and Hoffmann 1995; Kreisner et al. 2016). In contrast, non-CI-causing Wolbachia, such as wAu in D. simulans (Hoffmann et al. 1996), typically persist at lower frequencies, presumably maintained by a balance between positive Wolbachia effects on host fitness and imperfect maternal transmission (Hoffmann and Turelli 1997; Kreisner et al. 2013). When H < F(1 – μ) < 1, “bistable” dynamics result, producing stable equilibria at 0 and at a higher frequency denoted ps, where 0.50 < ps ≤ 1 (Turelli and Hoffmann 1995). Bistability explains the pattern and (slow) rate of spread of wMel transinfected into Aedes aegypti to suppress the spread of dengue, Zika and other human diseases (Hoffmann et al. 2011; Barton and Turelli 2011; Turelli and Barton 2017; Schmidt et al. 2017).

In contrast to the bistability observed with wMel transinfections, natural Wolbachia infections seem to spread via “Fisherian” dynamics with F(1 – μ) > 1 (Fisher 1937; Kriesner et al. 2013; Hamm et al. 2014). Several Wolbachia effects could generate F(1 – μ) > 1, but we do not yet know which ones actually do. For example, wRi has evolved to increase D. simulans fecundity in only a few decades (Weeks et al. 2007), wMel seems to enhance D. melanogaster fitness in high and low iron environments (Brownlie et al. 2009), and several Wolbachia including wMel protect their Drosophila hosts from RNA viruses (Hedges et al. 2008; Teixeira et al. 2008; Martinez et al. 2014). However, it remains unknown which if any these potential fitness benefits underlie Wolbachia spread in nature. For instance, wMel seems to have little effect on viral abundance in wild-caught D. melanogaster (Webster et al. 2015; Shi et al. 2018).

D. mauritiana, D. simulans and D. sechellia comprise the D. simulans clade within the nine-species D. melanogaster subgroup of Drosophila. The D. simulans clade diverged from D. melanogaster approximately three million years ago (mya), with the island endemics D. sechellia (Seychelles archipelago) and D. mauritiana (Mauritius) thought to originate in only the last few hundred thousand years (Lachaise et al. 1986; Ballard 2000a; Dean and Ballard 2004; McDermott and Kliman 2008; Garrigan et al. 2012; Brand et al. 2013; Garrigan et al. 2014). D. simulans is widely distributed around the globe, but has never been collected on Mauritius (David et al. 1989; Legrand et al. 2011). However, evidence of mitochondrial and nuclear introgression supports interisland migration and hybridization between these species (Ballard 2000a; Nunes et al. 2010; Garrigan et al. 2012), which could allow introgressive Wolbachia transfer (Rousset and Solignac 1995).

D. mauritiana is infected with Wolbachia denoted wMau, likely acquired via introgression from other D. simulans-clade hosts (Rousset and Solignac 1995). Wolbachia variant wMau may also infect D. simulans (denoted wMa in D. simulans) in Madagascar and elsewhere in Africa and the South Pacific (Ballard 2000a; Ballard 2004). wMau does not cause CI in D. mauritiana or when transinfected into D. simulans (Giordano et al. 1995). Yet it is very closely related to wNo strains that do cause CI in D. simulans (Merçot et al. 1995; Rousset and Solignac 1995; James and Ballard 2000, 2002). (Also, D. simulans seems to be a “permissive” host for CI, as evidenced by the fact that wMel, which causes little CI in its native host, D. melanogaster, causes intense CI in D. simulans [Poinsot et al. 1998].) Fast et al. (2011) reported that a wMau variant increased D. mauritiana fecundity four-fold. This fecundity effect occurred in concert with wMau-induced alternations of programmed cell death in the germarium and of germline stem cell mitosis, possibly providing insight into the mechanisms underlying increased egg production (Fast et al. 2011). However, the generality of this finding across wMau variants and host genetic backgrounds remains unknown.

Here, we assess the genetic and phenotypic basis of wMau frequencies in D. mauritiana on Mauritius by combining analysis of wMau draft genomes with analysis of wMau transmission in the laboratory and wMau effects on host fecundity and egg hatch. We identify a single mutation that disrupts a locus associated with CI. The loss of CI in wMau is consistent with theory demonstrating that selection within host species does not act to increase or maintain the level of CI (Prout 1994; Turelli 1994; Haygood and Turelli 2009), but instead acts to increase F(1 – μ), the product of Wolbachia effects on host fitness and maternal transmission efficiency (Turelli 1994). The loss of CI helps explain the intermediate wMau frequencies on Mauritius, reported by us and Giordano et al. (1995). We find no wMau effects on host fecundity, and theoretical analyses show that even a two-fold fecundity increase cannot be reconciled with the observed intermediate population frequencies, unless maternal wMau transmission is exceptionally unreliable in the field. Finally, we present theoretical analyses illustrating that the persistence of two distinct classes of mtDNA haplotypes among Wolbachia-uninfected D. mauritiana is unexpected under a simple null model. Together, our results contribute to understanding the genomic and phenotypic basis of global Wolbachia persistence, which is relevant to improving Wolbachia-based biocontrol of human diseases (Ritchie 2018).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila Husbandry and Stocks

The D. mauritiana isofemale lines used in this study (N = 32) were sampled from Mauritius in 2006 by Margarita Womack and kindly provided to us by Prof. Daniel Matute from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. We also obtained four D. simulans stocks (lines 196, 297, 298, and 299) from the National Drosophila Species Stock Center that were sampled from Madagascar. Stocks were maintained on modified version of the standard Bloomington-cornmeal medium (Bloomington Stock Center, Bloomington, IN) and were kept at 25°C, 12 light:12 dark photoperiod prior to the start of our experiments.

Determining Wolbachia infection status and comparing infection frequencies

One to two generations prior to our experiments DNA was extracted from each isofemale line using a standard ‘squish’ buffer protocol (Gloor et al. 1993), and infection status was determined using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Simpliamp ThermoCycler, Applied Biosystems, Singapore). We amplified the Wolbachia-specific wsp gene (Forward: 5’-TGGTCCAATAAGTGATGAAGAAAC-3’; Reverse: 5’-AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA-3’; Braig et al. 1998) and a nuclear control region of the 2L chromosome (Forward: 5’-TGCAGCTATGGTCGTTGACA-3’; Reverse: 5’-ACGAGACAATAATATGTGGTGCTG-3’; designed here). PCR products were visualized using 1% agarose gels that included a molecular-weight ladder. Assuming a binomial distribution, we estimated exact 95% binomial confidence intervals for the infection frequencies on Mauritius. Using Fisher’s Exact Test, we tested for temporal differences in wMau frequencies by comparing our frequency estimate to a previous estimate (Giordano et al. 1995). All analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 (R Team 2015).

We used quantitative PCR (qPCR) (MX3000P, Agilent Technologies, Germany) to confirm that tetracycline-treated flies were cleared of wMau. DNA was extracted from D. mauritiana flies after four generations of tetracycline treatment (1–2 generations prior to completing our experiments), as described below. Our qPCR used a PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™, California, USA) and amplified Wolbachia-specific wsp (Forward: 5’-CATTGGTGTTGGTGTTGGTG-3’; Reverse: 5’-ACCGAAATAACGAGCTCCAG-3’) and Rpl32 as a nuclear control (Forward: 5’-CCGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATC-3’; Reverse: 5’-CAATCTCCTTGCGCTTCTTG-3’; Newton and Sheehan 2014).

Wolbachia DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing

We sequenced wMau-infected R9, R29, and R60 D. mauritiana genotypes. Tissue samples for genomic DNA were extracted using a modified CTAB Genomic DNA Extraction protocol. DNA quantity was tested on an Implen Nanodrop (Implen, München, Germany) and total DNA was quantified by Qubit Fluorometric Quantitation (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). DNA was cleaned using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, U.S.A), following manufacturers’ instructions, and eluted in 50 μl 1× TE Buffer for shearing. DNA was sheared using a Covaris E220 Focused Ultrasonicator (Covaris Inc., Woburn, MA) to a target size of 400 bp. We prepared libraries using NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep with Sample Purification Beads (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts). Final fragment sizes and concentrations were confirmed using a TapeStation 2200 system (Agilent, Santa Clara, California). We indexed samples using NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina® (Index Primers Set 3 & Index Primers Set 4), and 10 μl of each sample was shipped to Novogene (Sacramento, CA) for sequencing using Illumina HiSeq 4000 (San Diego, CA), generating paired-end, 150 bp reads.

Wolbachia assembly

We obtained published reads (N = 6) from Garrigan et al. (2014), and assembled these genomes along with the R9, R29, and R60 genomes that we sequenced. Reads were trimmed using Sickle v. 1.33 (Joshi and Fass 2011) and assembled using ABySS v. 2.0.2 (Jackman et al. 2017). K values of 41, 51, 61, and 71 were used, and scaffolds with the best nucleotide BLAST matches to known Wolbachia sequences with E-values less than 10−10 were extracted as the draft Wolbachia assemblies. We deemed samples infected if the largest Wolbachia assembly was at least 1 million bases and uninfected if the largest assembly was fewer than 100,000 bases. No samples produced Wolbachia assemblies between 100,000 and 1 million bases. Of the six sets of published reads we analyzed (Garrigan et al. 2014), only lines R31 and R41 were wMau-infected. We also screened the living copies of these lines for wsp using PCR, and both were infected, supporting reliable wMau transmission in the lab since these lines were sampled in nature.

To assess the quality of our draft assemblies, we used BUSCO v. 3.0.0 to search for homologs of the near-universal, single-copy genes in the BUSCO proteobacteria database (Simao et al. 2015). As a control, we performed the same search using the reference genomes for wRi (Klasson et al. 2009), wAu (Sutton et al. 2014), wMel (Wu et al. 2004), wHa (Ellegaard et al. 2013), and wNo (Ellegaard et al. 2013).

Wolbachia gene extraction and phylogenetics

To determine phylogenetic relationships and estimate divergence times, we obtained the public Wolbachia group-B genomes of: wAlbB that infects Aedes albopictus (Mavingui et al. 2012), wPip_Pel that infects Culex pipiens (Klasson et al. 2008), wPip_Mol that infects Culex molestus (Pinto et al. 2013), wNo that infects Drosophila simulans (Ellegaard et al. 2013), and wVitB that infects Nasonia vitripennis (Kent et al. 2011); in addition to group-A genomes of: wMel that infects D. melanogaster (Wu et al. 2004), wSuz that infects D. suzukii (Siozios et al. 2013), four Wolbachia that infect Nomada bees (wNFe, wNPa, wNLeu, and wNFa; Gerth and Bleidorn 2016), and three Wolbachia that infect D. simulans (wRi, wAu and wHa; Klasson et al. 2009; Sutton et al. 2014; Ellegaard et al. 2013). The previously published genomes and the five wMau-infected D. mauritiana genomes were annotated with Prokka v. 1.11, which identifies homologs to known bacterial genes (Seemann 2014). To avoid pseudogenes and paralogs, we used only genes present in a single copy, and with no alignment gaps, in all of the genome sequences. Genes were identified as single copy if they uniquely matched a bacterial reference gene identified by Prokka v. 1.11. By requiring all homologs to have identical length in all of the draft Wolbachia genomes, we removed all loci with indels. 153 genes, a total of 123,720 bp, met these criteria when comparing all of these genomes. However, when our analysis was restricted to the five wMau genomes, our criteria were met by 686 genes, totaling 696,312 bp. Including wNo with the five wMau genomes reduced our set to 651 genes with 655,380 bp. We calculated the percent differences for the three codon positions within wMau and between wMau and wNo.

We estimated a Bayesian phylogram of the Wolbachia sequences with RevBayes 1.0.8 under the GTR + Γ model, partitioning by codon position (Höhna et al. 2016). Four independent runs were performed, which all agreed.

We estimated a chronogram from the Wolbachia sequences using the absolute chronogram procedure implemented in Turelli et al. (2018). Briefly, we generated a relative relaxed-clock chronogram with the GTR + Γ model with the root age fixed to 1 and the data partitioned by codon position. The relaxed clock branch rate prior was Γ(2,2). We used substitution-rate estimates of Γ(7,7) × 6.87×10−9 substitutions/3rd position site/year to transform the relative chronogram into an absolute chronogram. This rate estimate was chosen so that the upper and lower credible intervals matched the posterior distribution estimated by Richardson et al. (2012), assuming 10 generations/year, normalized by their median estimate of 6.87×10−9 substitutions/3rd position site/year. Although our relaxed-clock analyses allow for variation in substitution rates across branches, our conversion to absolute time depends on the unverified assumption that the median substitution rate estimated by Richardson et al. (2012) for wMel is relevant across these broadly diverged Wolbachia. (To assess the robustness of our conclusions to model assumptions, we also performed a strict-clock analysis and a relaxed-clock analysis with branch-rate prior Γ(7,7).) For each analysis, four independent runs were performed, which all agreed. Our analyses all support wNo as sister to wMau.

We also estimated a relative chronogram for the host species using the procedure implemented in Turelli et al. (2018). Our host phylogeny was based on the same 20 nuclear genes used in Turelli et al. (2018): aconitase, aldolase, bicoid, ebony, enolase, esc, g6pdh, glyp, glys, ninaE, pepck, pgi, pgm, pic, ptc, tpi, transaldolase, white, wingless and yellow.

Analysis of Wolbachia and mitochondrial genomes

We looked for copy number variation (CNV) between wMau and its closest relative, wNo across the whole wNo genome. Reads from the five infected wMau lines were aligned to the wNo reference (Ellegaard et al. 2013) with bwa 0.7.12 (Li and Durbin 2009). We calculated the normalized read depth for each alignment over sliding 1,000-bp windows by dividing the average depth in the window by the average depth over the entire wNo genome. The results were plotted and visually inspected for putative copy number variants (CNVs). The locations of CNVs were specifically identified with ControlFREEC v. 11.5 (Boeva et al. 2012), using a ploidy of one and a window size of 1,000. We calculated P-values for each identified CNV with the Wilcoxon Rank Sum and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests implemented in ControlFREEC.

We used BLAST to search for pairs of CI-factor (cif) homologs in wMau and wNo genomes that are associated with CI (Beckmann and Fallon 2013; Beckmann et al. 2017; LePage et al. 2017; Lindsey et al. 2018; Beckmann et al. 2019). (We adopt Beckmann et al. (2019)’s nomenclature that assigns names to loci based on their predicted enzymatic function, with superscripts denoting the focal Wolbachia strain.) These include predicted CI-inducing deubiquitylase (cid) wPip_0282-wPip_0283 (cidA-cidBwPip) and CI-inducing nuclease (cin) wPip_0294-wPip_0295 (cinA-cinBwPip) pairs that induce toxicity and rescue when expressed/co-expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Beckmann et al. 2017 and Beckmann et al. 2019); WD0631-WD632 (cidA-cidBwMel) that recapitulate CI when transgenically expressed in D. melanogaster (LePage et al. 2017); and wNo_RS01055 and wNo_RS01050 that have been identified as a Type III cifA-cifB pair in the wNo genome (LePage et al. 2017; Lindsey et al. 2018). wNo_RS01055 and wNo_RS01050 are highly diverged from cidA-cidBwMel and cidA-cidBwPip homologs and from cinA-cinBwPip; however, this wNo pair is more similar to cinA-cinBwPip in terms of protein domains, lacking a ubiquitin-like protease domain (Lindsey et al. 2018). We refer to these loci as cinA-cinBwNo.

We found only homologs of the cinA-cinBwNo pair in wMau genomes, which we extracted from our draft wMau assemblies and aligned with MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh and Standley 2013). We compared cinA-cinBwNo to the wMau homologs to identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) among our wMau assemblies.

D. mauritiana carry either the maI mitochondrial haplotype, associated with wMau infections, or the maII haplotype (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Ballard 2000a; James and Ballard 2000). To determine the mitochondrial haplotype of each D. mauritiana line, we assembled the mitochondrial genomes by down-sampling the reads by a factor of 100, then assembling with ABySS 2.0.2 using a K value of 71 for our data (150 bp reads) and 35 for the published data (76 bp reads) (Garrigan et al. 2014). Down-sampling reads prevents the nuclear genome from assembling but does not inhibit assembly of the mitochondrial genome, which has much higher coverage. We deemed the mitochondrial assembly complete if all 13 protein-coding genes were present on the same contig and in the same order as in D. melanogaster. If the first attempt did not produce a complete mitochondrial assembly, we adjusted the down-sampling fraction until a complete assembly was produced for each line.

Annotated reference mitochondrial sequences for the D. mauritiana mitochondrial haplotypes maI and maII were obtained from Ballard et al. (2000b), and the 13 protein-coding genes were extracted from our assemblies using BLAST and aligned to these references. The maI and maII reference sequences differ at 343 nucleotides over these protein-coding regions. We identified our lines as carrying the maI haplotype if they differed by fewer than five nucleotides from the maI reference and as maII if they differed by fewer than five nucleotides from the maII reference. None of our assemblies differed from both references at five or more nucleotides.

wMau phenotypic analyses

Previous analyses have demonstrated that wMau does not cause CI (Giordano et al. 1995). To check the generality of this result, we reciprocally crossed wMau-infected R31 D. mauritiana with uninfected R4 and measured egg hatch. Flies were reared under controlled conditions at 25°C for multiple generations leading up to the experiment. We paired 1–2-day-old virgin females with 1–2-day-old males in a vial containing spoons with cornmeal media and yeast paste. After 24 hr, pairs were transferred to new spoons, and this process was repeated for five days. Eggs on each spoon were given 24 hr at 25°C to hatch after flies were removed. To test for CI, we used nonparametric Wilcoxon tests to compare egg hatch between reciprocal crosses that produced at least 10 eggs. All experiments were carried out at 25°C with a 12 light:12 dark photoperiod.

To determine if wMau generally enhances D. mauritiana fecundity, we assessed the fecundity of two wMau-infected isofemale lines from Mauritius (R31 and R41); we also reciprocally introgressed wMau from each of these lines to assess host effects. To do this we crossed R31 females with R41 males and backcrossed F1 females to R41 males—this was repeated for four generations to generate the reciprocally introgressed R41R31 genotypes (wMau variant denoted by superscripts). A similar approach was taken to generate R31R41 genotypes. This approach has previously revealed D. teissieri-host effects on wTei-induced CI (Cooper et al. 2017). To assay fecundity, we reciprocally crossed each genotype (R31, R41, R31R41, R31R41) to uninfected line R4 to generate paired infected-and uninfected-F1 females with similar genetic backgrounds. The wMau-infected and uninfected F1 females were collected as virgins and placed in holding vials. We paired 3–7-day-old females individually with an uninfected-R4 male (to stimulate oviposition) in vials containing a small spoon filled with standard cornmeal medium and coated with a thin layer of yeast paste. We allowed females to lay eggs for 24 hours, after which pairs were transferred to new vials. This was repeated for five days. At the end of each 24-hr period, spoons were frozen until counted. All experiments were carried out at 25°C with a 12 light:12 dark photoperiod.

We also measured egg lay of wMau-infected (R31) and tetracycline-cleared uninfected (R31-tet) genotypes over 24 days, on apple-agar plates, to more closely mimic the methods of Fast et al. (2011). We fed flies 0.03% tetracycline concentrated medium for four generations to generate the R31-tet genotype. We screened F1 and F2 individuals for wMau using PCR, and we then fed flies tetracycline food for two additional generations. In the fourth generation, we assessed wMau titer using qPCR to confirm that each genotype was cleared of wMau infection. We reconstituted the gut microbiome by rearing R31-tet flies on food where R31 males had fed and defecated for 48 hours. Flies were given at least three more generations to avoid detrimental effects of tetracycline treatment on mitochondrial function (Ballard and Melvin 2007). We then paired individual 6–7-day-old virgin R31 (N = 30) and R31-tet (N = 30) females in bottles on yeasted apple-juice agar plates with an R4 male to stimulate oviposition. Pairs were placed on new egg-lay plates every 24 hrs. After two weeks, we added one or two additional R4 males to each bottle to replace any dead males and to ensure that females were not sperm limited as they aged.

We used nonparametric Wilcoxon tests to assess wMau effects on host fecundity. We then estimated the fitness parameter F in the standard discrete-generation model of CI (Hoffmann et al. 1990; Turelli 1994). We used the ‘pwr.t2n.test’ function in the ‘pwr’ library in R to assess the power of our data to detect increases to F. Pairs that laid fewer than 10 eggs across each experiment were excluded from analyses, but our results are robust to this threshold.

To estimate the fidelity of maternal transmission, R31 and R41 females were reared at 25°C for several generations prior to our experiment. In the experimental generation, 3–5 day old inseminated females were placed individually in vials that also contained two males. These R31 (N = 17) and R41 (N = 19) sublines were allowed to lay eggs for one week. In the following generation we screened F1 offspring for wMau infection using PCR as described above.

RESULTS

Wolbachia infection status

Out of 32 D. mauritiana lines that we analyzed, 11 were infected with wMau Wolbachia (infection frequency = 0.34; binomial confidence interval: 0.19, 0.53). In contrast, none of the D. simulans stocks (N = 4) sampled from Madagascar were infected, precluding our ability to directly compare wMau and wMa. Our new wMau frequency estimate is not statistically different from a previous estimate (Giordano et al. 1995: infection frequency, 0.46; binomial confidence interval, (0.34, 0.58); Fisher’s Exact Test, P = 0.293), based largely on assaying a heterogenous collecton of stocks in various laboratories. These relatively low infection frequencies are consistent with theoretical expectations given that wMau does not cause CI (Giordano et al. 1995; our data reported below). The intermediate wMau frequencies on Mauritius suggest that wMau persists at a balance between positive effects on host fitness and imperfect maternal transmission. Quantitative predictions, based on the idealized model of Hoffmann and Turelli (1997), are discussed below. The maintenance of wMau is potentially analogous to the persistence of other non-CI-causing Wolbachia, specifically wAu in some Australian populations of D. simulans (Hoffmann et al. 1996; Kriesner et al. 2013) and wSuz in D. suzukii and wSpc in D. subpulchrella (Hamm et al. 2014; Conner et al. 2017; Turelli et al. 2018; but see Cattel et al. 2018).

Draft wMau genome assemblies and comparison to wNo

The five wMau draft genomes we assembled were of very similar quality (Supplemental Table 1). N50 values ranged from 60,027 to 63,676 base pairs, and our assemblies varied in total length from 1,266,004 bases to 1,303,156 bases (Supplemental Table 1). Our BUSCO search found exactly the same genes in each draft assembly, and the presence/absence of genes in our wMau assemblies was comparable to those in the complete genomes used as controls (Supplemental Table 2). In comparing our five wMau draft genomes over 694 single-copy, equal-length loci comprising 704,613 bp, we found only one SNP. Four sequences (R9, R31, R41 and R60) are identical at all 704,613 bp. R29 differs from them at a single nucleotide, a nonsynonymous substitution in a locus which Prokka v. 1.11 annotates as “bifunctional DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta/beta.”

Comparing these five wMau sequences to the wNo reference (Ellegaard et al. 2013) over 671 genes with 682,494 bp, they differ by 0.068% overall, with equivalent divergence at all three codon positions (0.067%, 0.061%, and 0.076%, respectively).

Wolbachia phylogenetics

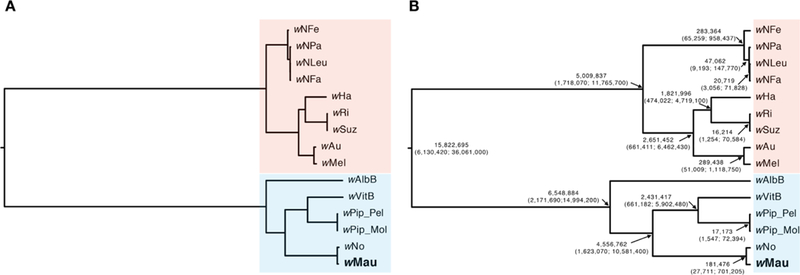

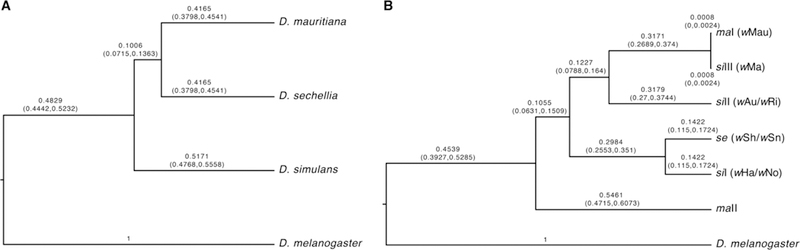

As expected from the sequence comparisons, our group-B phylogram places wMau sister to wNo (Figure 1A). This is consistent with previous analyses using fewer loci that placed wMau (or wMa in D. simulans) sister to wNo (James and Ballard 2000; Zabalou et al. 2008; Toomey et al. 2013). Our chronogram (Figure 1B) estimates the 95% credible interval for the split between the group-B versus group-A Wolbachia strains as 6 to 36 mya (point estimate, 16 mya). Reducing the variance on the substitution-rate-variation prior by using Γ(7,7) rather than Γ(2,2), changes the credible interval for the A-B split to 8 to 46 mya (point estimate, 21 mya). In contrast, a strict clock analysis produces a credible interval of 12 to 64 mya (point estimate, 31 mya). These estimates are roughly comparable to an earlier result based on a general approximation for the synonymous substitution rate in bacteria (Ochman and Wilson 1987) and data from only the ftsZ locus (59–67 mya, Werren et al. 1995). However, our estimates are much lower than an alternative estimate based on comparative genomics (217 mya, Gerth and Bleidorn 2016). We discuss this discrepancy below.

Figure 1.

A) An estimated phylogram for various group-A (red) and group-B (blue) Wolbachia strains. All nodes have Bayesian posterior probabilities of 1. The phylogram shows significant variation in the substitution rates across branches, with long branches separating the A and B clades. B) An estimated chronogram for the same strains, with estimated divergence times and their confidence intervals at each node. To obtain these estimates, we generated a relative relaxed-clock chronogram with the GTR + Γ model with the root age fixed to 1, the data partitioned by codon position, and with a Γ(2,2) branch rate prior. We used substitution-rate estimates of Γ(7,7) × 6.87×10−9 substitutions/3rd position site/year to transform the relative chronogram into an absolute chronogram.

The observed divergence between wNo and wMau is consistent across all three codon positions, similar to other recent Wolbachia splits like that between wRi and wSuz (Turelli et al. 2018). Conversely, observed divergence at each codon position generally varies across the chronogram, leading to inflation of the wNo-wMau (181,476 years; credible interval = 27,711 to 701,205 years; Figure 1B) and wRi-wSuz (16,214; credible interval = 1,254 to 70,584) divergence point estimates; the latter is about 1.6 times as large as the value in Turelli et al. (2018). (Nevertheless, the confidence intervals of our and Turelli et al. (2018)’s wRi-wSuz divergence estimates overlap.) To obtain an alternative estimate of wNo-wMau divergence, we estimated divergence time using the observed third-position pairwise divergence (0.077%, or 0.039% from tip to MRCA) and Richardson et al. (2012)’s estimate of the “short-term evolutionary rate” of Wolbachia third-position divergence within wMel. This approach produces a point estimate of 57,000 years, with a credible interval of 30,000 to 135,000 years for the wNo-wMau split. In Cooper et al. (2019), we address in detail how a constant substitution-rate ratio among codon positions across the tree, assumed by the model, affects these estimates.

Analysis of Wolbachia and mitochondrial genomes

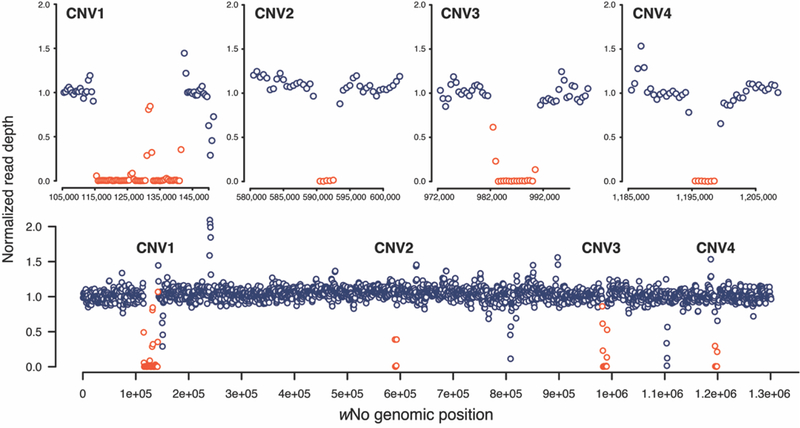

We looked for CNVs in wMau relative to sister wNo by plotting normalized read depth along the wNo genome. There were no differences in copy number among the wMau variants, but compared to wNo, ControlFREEC identified four regions deleted from all wMau that were significant according to the Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 3). These deleted regions of the wMau genomes include many genes, including many phage-related loci, providing interesting candidates for future work (listed in Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 2.

All wMau variants share four large deletions, relative to sister wNo. Top panel) The normalized read depth for wMau R60 plotted across the four focal regions of the wNo reference genome; 10 kb of sequence surrounding regions are plotted on either side of each region. Bottom panel) The normalized read depth of wMau R60 plotted across the whole wNo reference genome. Regions that do not contain statistically significant CNVs are plotted in dark blue, and regions with significant CNVs are plotted in red. All wMau variants share the same CNVs, relative to wNo.

To test the hypothesis that cif loci are disrupted, we searched for pairs of loci known to be associated with CI and found homologs to the cinA-cinBwNo pair in each of our draft assemblies, but we did not find homologs to the cidA-cidBwMel, cidA-cidBwPip, or to the cinA-cinBwPip pairs. There were no variable sites in cinA-cinBwNo homologs among our five wMau assemblies. Relative to wNo, all wMau variants share a one base pair deletion at base 1133 out of 2091 (amino acid 378) in the cinBwNo homolog. This frameshift introduces over 10 stop codons, with the first at amino acid 388, potentially making this predicted CI-causing-toxin protein nonfunctional. We also identified a nonsynonymous substitution in amino acid 264 of the cinBwNo homolog (wNo codon ACA, Thr; wMau codon AUA, Ile) and two SNVs in the region homologous to cinAwNo: a synonymous substitution in amino acid 365 (wNo codon GUC, wMau codon GUU) and a nonsynonymous substitution in amino acid 397 (wNo codon GCU, amino acid Ala; wMau codon GAU, amino acid Asp). Disruption of CI is consistent with theoretical analyses showing that selection within a host species does not act directly on the level of CI (Prout 1994; Turelli 1994; Haygood and Turelli 2009). Future functional analyses will determine whether disruption of regions homologous to cinA-cinBwNo underlie the lack of wMau CI.

Of the D. mauritiana lines tested (N = 9), one line (uninfected-R44) carries the maII mitochondrial haplotype, while the other eight carry maI. Rousset and Solignac (1995) reported a similar maII frequency, with 3 of 26 lines sampled in 1985 carrying maII. The maI and maII references differ by 343 SNVs across the proteome, and R44 differs from the maII reference by 4 SNVs in the proteome. Four of our maI lines (R23, R29, R32, and R39) are identical to the maI reference, while three (R31, R41, and R60) have one SNV and one (R9) has two SNVs relative to maI reference. One SNV is shared between R9 and R60, but the other three SNVs are unique. Our results agree with past analyses that found wMau is perfectly associated with the maI mitochondrial haplotype (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Ballard 2000a; James and Ballard 2000). The presence of maII among the uninfected is interesting. In contrast to maI, which is associated with introgression with D. simulans (Ballard 2000a; James and Ballard 2000), maII appears as an outgroup on the mtDNA phylogeny of the D. simulans clade and is not associated with Wolbachia (Ballard 2000b, Fig. 5; James and Ballard 2000). Whether or not Wolbachia cause CI, if they are maintained by selection-imperfect-transmission balance, we expect all uninfected flies to eventually carry the mtDNA associated with infected mothers (Turelli et al. 1992). We present a mathematical analysis of the persistence of maII below.

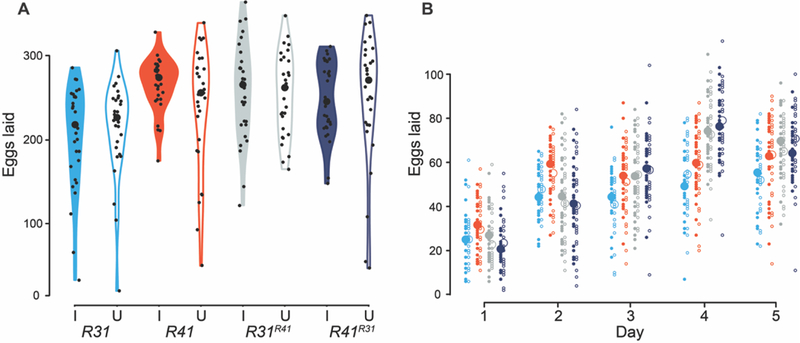

Analysis of wMau phenotypes

In agreement with Giordano et al. (1995), we found no difference between the egg hatch of uninfected females crossed to wMau-infected males (0.34 ± 0.23 SD, N = 25) and the reciprocal cross (0.29 ± 0.28 SD, N = 24), indicating no CI. In contrast to Fast et al. (2011), we find no evidence that wMau affects D. mauritiana fecundity (Supplemental Table 5 and Figure 3), regardless of host genetic backgrounds. Across both experiments assessing wMau fecundity effects in their natural backgrounds (R31 and R41), we counted 27,221 eggs and found no difference in the number of eggs laid by infected (mean = 238.20, SD = 52.35, N = 60) versus uninfected (mean = 226.82, SD = 67.21, N = 57) females over the five days of egg lay (Wilcoxon test, W = 1540.5, P = 0.357); and across both experiments that assessed wMau fecundity effects in novel host backgrounds (R31R41 and R41R31), we counted 30,358 eggs and found no difference in the number of eggs laid by infected (mean = 253.30, SD = 51.99, N = 60) versus uninfected (mean = 252.67, SD = 63.53, N = 60) females over five days (Wilcoxon test, W = 1869.5, P = 0.719). [The mean number of eggs laid over five days, standard deviation (SD), sample size (N), and P-values from Wilcoxon tests are presented in Supplemental Table 5 for all pairs.]

Figure 3.

wMau infections do not influence D. mauritiana fecundity, regardless of host genomic background. A) Violin plots of the number of eggs laid by D. mauritiana females over five days when infected with their natural wMau variant (R31I and R41I), when infected with a novel wMau variant (R31R41I and R41R31I), and when uninfected (R31U, R41U, R31R41U, and R41R31U). Large black dots are medians, and small black dots are the eggs laid by each replicate over five days. B) The daily egg lay of these same infected (solid circles) and uninfected (open circles) R31 (aqua), R41 (red), R31R41 (gray), and R41R31 (dark blue) genotypes is reported. Large circles are means of all replicates, and small circles are the raw data. Only days where females laid at least one egg are plotted. Cytoplasm sources are denoted by superscripts for the reciprocally introgressed strains.

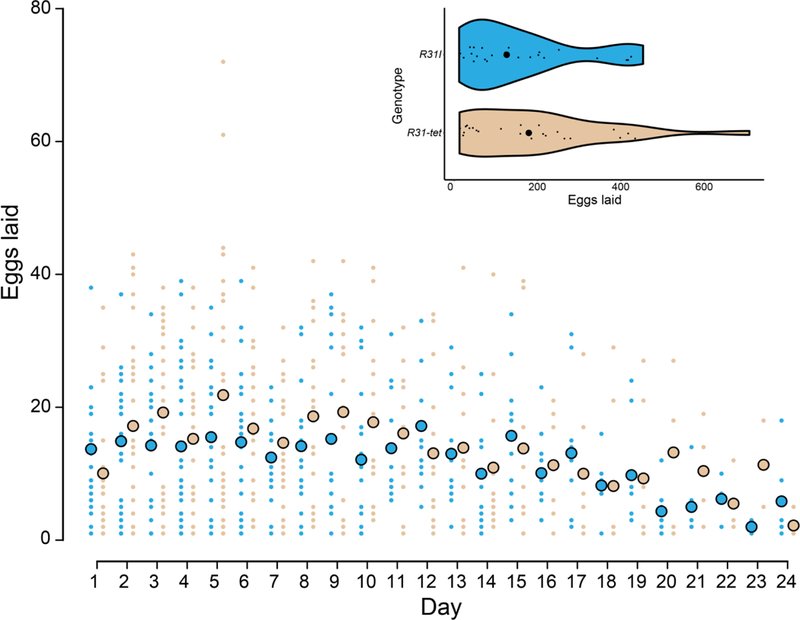

We sought to determine if wMau fecundity effects depend on host age with a separate experiment that assessed egg lay over 24 days on apple-agar plates, similar to Fast et al. (2011). Across all ages, we counted 9,459 eggs and found no difference in the number of eggs laid by infected (mean = 156.29, SD = 138.04, N = 28) versus uninfected (mean = 187.70, SD = 168.28, N = 27) females (Wilcoxon test, W = 409, P = 0.608) (Figure 4). While our point estimates indicate that wMau does not increase host fecundity, egg lay was generally lower and more variable on agar plates relative to our analyses of egg lay on spoons described above.

Figure 4.

The mean number of eggs laid by infected R31 (R31I, large aqua dots) and uninfected R31-tet (large tan dots) genotypes are similar. Egg counts for each replicate are also plotted (small dots). Violin plots show egg lay across all ages for each genotype; large black circles are medians, and small black circles are the number of eggs laid by each replicate.

With these data, we estimated the fitness parameter F in the standard discrete-generation model of CI (Hoffmann et al. 1990; Turelli 1994). Taking the ratio of replicate mean fecundity observed for wMau-infected females to the replicate mean fecundity of uninfected females in naturally sampled R31 and R41 D. mauritiana backgrounds, we estimated F = 1.05 (95% BCa interval: 0.96, 1.16). Following reciprocal introgression of wMau and host backgrounds (i.e., the R31R41 and R41R31 genotypes), we estimated F = 1.0 (95% BCa interval: 0.93, 1.09). Finally, across all 24 days of our age-effects experiment, we estimated F = 0.83, 95% BCa interval: 0.52, 1.32) for R31, which overlaps with our estimate of F for R31 in our initial experiment (Table 1). BCa confidence intervals were calculated using the two-sample acceleration constant given by equation 15.36 of Efron and Tibshirani (1993). (Estimates of F and the associated BCa confidence intervals are reported in Table 1 for each genotype and condition.) Consistent with our other analyses, we find little evidence that wMau significantly increases fecundity. However, our data do not have much statistical power to detect values of F on the order of 1.05, which may suffice to produce F(1 – μ) > 1 and deterministic spread of wMau from low frequencies. We present our power calculations in Figure 1B of the Supplementary Information.

Table 1.

Estimates of the relative fitness parameter F indicate that wMau fecundity effects are likely to be minimal.

| wMau variant/age class | F | 95% BCa interval |

|---|---|---|

| R31 | 0.988 | (0.862, 1.137) |

| R41 | 1.107 | (0.995, 1.265) |

| R31R41 | 1.012 | (0.911, 1.122) |

| R41R31 | 0.992 | (0.884, 1.143) |

| R31(across age) | 0.833 | (0.515, 1.323) |

Finally, we assessed the fidelity of wMau maternal transmission under standard laboratory conditions. We excluded sublines that produced fewer than 8 F1 offspring. In all cases, R31 (N = 17) sublines produced offspring that were all infected, indicating perfect maternal transmission. In contrast, one R41 subline produced one uninfected individual out of a total of 18 F1 offspring produced; all other R41 sublines meeting our criteria (N = 15) produced only infected F1 offspring, resulting in nearly perfect maternal transmission across all R41 sublines (μ = 0.0039).

Mathematical analyses of Wolbachia frequencies and mtDNA polymorphism

If Wolbachia do not cause CI (or any other reproductive manipulation), their dynamics can be approximated by a discrete-generation haploid selection model. Following Hoffmann and Turelli (1997), we assume that the relative fecundity of Wolbachia-infected females is F, but a fraction μ of their ova do not carry Wolbachia. Given our ignorance of the nature of Wolbachia’s favorable effects, the F represents an approximation for all fitness benefits. If F(1 – μ) > 1, the equilibrium Wolbachia frequency among adults is

| (1) |

Imperfect maternal transmisson has been documented for field-collected D. simulans infected with wRi (Hoffmann and Turelli 1988; Turelli and Hoffmann 1995; Carrington et al. 2011), D. melanogaster infected with wMel (Hoffmann et al. 1998) and D. suzukii infected with wSuz (Hamm et al. 2014). The estimates range from about 0.01 to 0.1. Given that we have documented imperfect maternal transmission of wMau in the laboratory, we expect (more) imperfect transmission in nature (Turelli and Hoffmann 1995; Carrington et al. 2011). In order for the equilibrium Wolbachia frequency to be below 0.5, approximation (1) requires that the relative fecundity of infected females satisfies

| (2) |

Thus, even for μ as large a 0.15, which greatly exceeds our laboratory estimates for wMau and essentially all estimates of maternal transmission failure from nature, Wolbachia can increase fitness by at most 43% and produce an equilibrium frequency below 0.5 (Supplemental Figure 1A). Conversely, (1) implies that a doubling of relative fecundity by Wolbachia would produce an equilibrium frequency 1 – 2μ. If μ ≤ 0.25, consistent with all available data, the predicted equilibrium implied by a Wolbachia-induced fitness doubling significantly exceeds the observed frequency of wMau. Hence, a four-fold fecundity effect, as described by Fast et al. (2011), is inconsistent with the frequency of wMau in natural populations of D. mauritiana. Field estimates of μ for D. mauritiana will provide better theory-based bounds on wMau fitness effects that would be consistent with wMau tending to increase when rare on Mauritius, i.e., conditions for F(1 – μ) > 1.

Our theoretical analysis, addressing the plausibility of a four-fold fitness increase caused by wMau, assumes that the observed frequency of wMau approximates selection-transmission equilibrium, as described by (1). With only two frequency estimates (one from a heterogeneous collection of laboratory stocks), we do not know that the current low frequency is temporarlly stable. Also, we do not know that the mutations we detect in cinA-cinBwNo homologs are responsible for the lack of wMau CI. One alternative is that D. mauritiana has evolved to suppress CI (for host suppression of male killing, see Hornet et al. 2006 and Vanthournout and Hendrickx 2016). Host suppression of CI is expected (Turelli 1994), and it may explain the low CI caused by wMel in D. melanogaster (Hoffmann and Turelli 1997). However, the fact that wMau does not produce CI in D. simulans, a host that allows wMel and other strains to induce strong CI even though little CI is produced in their native hosts, argues against host suppression as the explanation for the lack of CI caused by wMau in D. mauritiana. Nevertheless, the loss of CI from wMau may be quite recent; and wMau may be on its way to elimination in D. mauritiana. If so, our equilibrium analysis is irrelevant – but this gradual-loss scenario is equally inconsistent with the four-fold fecundity effect proposed by Fast et al. (2011).

As noted by Turelli et al. (1992), if Wolbachia is introduced into a population along with a diagnostic mtDNA haplotype that has no effect on fitness, imperfect Wolbachia maternal transmission implies that all infected and uninfected individuals will eventually carry the Wolbachia-associated mtDNA, because all will have had Wolbachia-infected maternal ancestors. We conjectured that a stable mtDNA polymorphism might be maintained if Wolbachia-associated mtDNA introduced by introgression is deleterious in its new nuclear background. We refute our conjecture in Appendix 1. We show that the condition for Wolbachia to increase when rare, F(1 – μ) > 1, ensures that the native mtDNA will be completely displaced by the Wolbachia-associated mtDNA, even if it lowers host fitness once separated from Wolbachia.

How fast is the mtDNA turnover, among Wolbachia-uninfected individuals, as a new Wolbachia invades? This is easiest to analyze when the mtDNA introduced with Wolbachia has no effect on fitness, so that the relative fitness of Wolbachia-infected versus uninfected individuals is F, irrespective of the mtDNA haplotype of the uninfected individuals. As shown in Appendix 1, the frequency of the ancestral mtDNA haplotype among uninfected individuals, denoted rt, declines as

| (3) |

Assuming r0 = 1, recursion (3) implies that even if F(1 – μ) is only 1.01, the frequency of the ancestral mtDNA haplotype should fall below 10−4 after 1000 generations. A much more rapid mtDNA turnover was seen as the CI-causing wRi swept northward through California populations of D. simulans (Turelli et al. 1992; Turelli and Hoffmann 1995). Thus, it is theoretically unexpected, under this simple model, that mtDNA haplotype maII, which seems to be ancestral in D. mauritiana (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Ballard 2000a), persists among Wolbachia-uninfected D. mauritiana, given that all sampled Wolbachia-infected individuals carry maI. However, spatial variation in fitnesses is one possible explanation for this polymorphism (Gliddon and Strobeck 1975), which has persisted since at least 1985.

DISCUSSION

wMau is sister to wNo and diverged from group-A Wolbachia less than 100 mya

Our phylogenetic analyses place wMau sister to wNo, in agreement with past analyses using fewer data (James and Ballard 2000; Zabalou et al. 2008; Toomey et al. 2013). The relationships we infer agree with those from recently published phylograms (Gerth and Bleidorn 2016; Lindsey et al. 2018) (Figure 1A).

Depending on the prior used for substitution-rate variation, we estimate that wMau and other group-B Wolbachia diverged from group-A strains about 6–46 mya. This is roughly consistent with a prior estimate using only ftsZ (58–67 mya, Werren et al. 1995), but is inconsistent with a recent estimate using 179,763 bases across 252 loci (76–460 mya, Gerth and Bleidorn 2016). There are several reasons why we question the Gerth and Bleidorn (2016) calibration. First, Gerth and Bleidorn (2016)’s chronogram placed wNo sister to all other group-B Wolbachia, in disagreement with their own phylogram (Gerth and Bleidorn 2016, Figure 3). In contrast, our phylogram and that of Lindsey et al. (2018) support wAlbB splitting from all other strains at this node. Second, the Gerth and Bleidorn (2016) calibration estimated the split between wRi that infects D. simulans and wSuz that infects D. suzukii at 900,000 years. This estimate is more than an order of magnitude higher than ours (16,214 years) and nearly two orders of magnitude higher than the 11,000 year estimate of Turelli et al. (2018) who found 0.014% third position divergence between wRi and wSuz (i.e., 0.007% along each branch) over 506,307 bases. Raychoudhury et al. (2009) and Richardson et al. (2012) both estimated a rate of about 7 × 10−9 substitutions/3rd position site/year between Wolbachia in Nasonia wasps and within wMel, respectively. An estimate of 900,000 years requires a rate about 100 times slower, 7.8 × 10−11 substitutions/3rd position site/year, which seems implausible. Finally, using data kindly provided by Michael Gerth, additional analyses indicate that the third-position rates required for the Wolbachia divergence times estimated by Gerth and Bleidorn (2016) between Nomada flava and N. leucophthalma (1.72 × 10−10), N. flava and N. panzeri (3.78 × 10−10) (their calibration point), and N. flava and N. ferruginata (4.14 × 10−10) are each more than 10 times slower than those estimated by Raychoudhury et al. (2009) and Richardson et al. (2012), which seems unlikely. Our analyses suggest that the A-B group split occurred less than 100 mya.

The lack of CI is consistent with intermediate wMau infection frequencies

Across 671 genes (682,494 bases), the wMau genomes were identical and differed from wNo by only 0.068%. Across the coding regions we analyzed, we found few SNVs and no CNVs among wMau variants. Our analyses did identify four large deletions shared by all wMau genomes, relative to wNo. Despite the close relationship between wMau and wNo, wNo causes CI while wMau does not (Giordano et al. 1995; Merçot et al. 1995; Rousset and Solignac 1995, our data). We searched for all pairs of loci known to cause CI and found only homologs to the cinA-cinBwNo pair in wMau genomes. All wMau variants share a one-base-pair deletion in the wMau region homologous to cinBwNo. This mutation introduces a frameshift and more than ten stop codons. Future functional work will help determine if disruption of this predicted-toxin locus underlies the lack of CI in wMau. Regardless, the lack of CI is consistent with the prediction that selection within host lineages does not directly act on the intensity of CI (Prout 1994; Turelli 1994). We predict that analysis of additional non-CI-causing strains will reveal additional examples of genomic remnants of CI loci. Among non-CI Wolbachia, the relative frequency of those with non-functional CI loci, versus no CI loci, is unknown.

Irrespective of whether CI was lost or never gained, non-CI Wolbachia have lower expected equilibrium infection frequencies than do CI-causing variants (Kriesner et al. 2016). The wMau infection frequency of approximately 0.34 on Mauritius (Giordano et al. 1995; our data) is consistent with this prediction. Additional sampling of Mauritius, preferably over decades, will determine whether intermediate wMau frequencies are temporally stable. Such temporal stability depends greatly on values of F and μ through time suggesting additional field-based estimates of these parameters will be useful.

wMau co-occurs with essentially the same mitochondrial haplotype as wMa that infects D. simulans on Madagascar and elsewhere in Africa and the South Pacific (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Merçot and Poinsot 1998; Ballard 2000a; James and Ballard 2000; James et al. 2002; Ballard 2004), suggesting that wMau and wMa may be the same strain infecting different host species following introgressive Wolbachia transfer (see below). wMau and wMa phenotypes are also more similar to one another than to wNo, with only certain crosses between wMa-infected D. simulans males and uninfected D. simulans females inducing CI (James and Ballard 2000). Polymorphism in the strength of CI induced by wMa could result from host modification of Wolbachia-induced CI (Reynolds and Hoffmann 2002; Cooper et al. 2017), or from Wolbachia titer variation that influences the strength of CI and/or the strength of CI rescue by infected females. Alternatively, the single-base-pair deletion in the cinBwNo homolog or other mutations that influence CI strength, could be polymorphic in wMa. wMa infection frequencies in D. simulans are intermediate on Madagascar (infection frequency = 0.25, binomial confidence intervals: 0.14, 0.40; James and Ballard 2000), consistent with no CI, suggesting replication of rarely observed wMa CI is needed. Including D. simulans from the island of Réunion in this infection-frequency further supports the conjecture that wMa causes little or no CI (infection frequency = 0.31, binomial confidence intervals: 0.20, 0.45; James and Ballard 2000). Unfortunately, no Madagascar D. simulans stocks available at the National Drosophila Species Stock Center were wMa infected, precluding detailed analysis of this strain.

Our genomic data indicate that wMau may maintain an ability to rescue CI, as the cinAwNo homolog is intact in wMau genomes with only one nonsynonymous substitution relative to cinAwNo; cidA in wMel was recently shown to underlie transgenic-CI rescue (Shropshire et al. 2018). wMa seems to sometimes rescue CI, but conflicting patterns have been found, and additional experiments are needed to resolve this (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Bourtzis et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998; James and Ballard 2000; Merçot and Poinsot 2003; Zabalou et al. 2008). Future work that tests for CI rescue by wMau and wMa-infected females crossed with males infected with wNo or other CI-causing strains, combined with genomic analysis of CI loci in wMa, will be useful.

wMau does not influence D. mauritiana fecundity

While selection does not directly act on the level of CI (Prout 1994; Turelli 1994; Haygood and Turelli 2009), it does act to increase the product Wolbachia-infected host fitness and the efficiency of maternal transmission (Turelli 1994). Understanding the Wolbachia effects that lead to spread from low frequencies and the persistence of non-CI causing Wolbachia at intermediate frequencies is crucial to explaining Wolbachia prevalence among insects and other arthropods. The four-fold fecundity effect of wMau reported by Fast et al. (2011) in D. mauritiana is inconsistent with our experiments and with the intermediate infection frequencies observed in nature. We find no wMau effects on host fecundity, regardless of host background, with our estimates of F having BCa intervals that include 1. Small increases in F could allow the deterministic spread of wMau from low frequencies, although detecting very small increases in F is difficult (Supplemental Figure 1B). Our results are consistent with an earlier analysis that assessed egg lay of a single genotype and found no effect of wMau on host fecundity (Giordano et al. 1995). When combined with the low observed infection frequencies, our fecundity data are also consistent with our mathematical analyses indicating that Wolbachia can increase host fitness by at most about 50% for reasonable estimates of μ. Because fecundity is one of many fitness components, analysis of other candidate phenotypes for aiding the spread of low-frequency Wolbachia is needed.

Introgressive Wolbachia transfer likely predominates in the D. simulans clade

Hybridization and introgression in the D. simulans clade may have led to introgressive transfer of Wolbachia among host species (Rousset and Solignac 1995). This has been observed in other Drosophila (Turelli et al. 2018; Cooper et al. 2019) and Nasonia wasps (Raychoudhury et al. 2009). The number of Wolbachia strains in the D. simulans clade, and the diversity of mitochondria they co-occur with, is complex. Figure 5A shows host relationships and Figure 5B shows mitochondrial relationships, with co-occurring Wolbachia variants in parentheses. While D. mauritiana is singly infected by wMau, D. simulans is infected by several strains, including CI-causing wHa and wNo that often co-occur as double infections within individuals (O’Neill and Karr 1990; Merçot et al. 1995; Rousset and Solignac 1995). wHa and wNo are similar to wSh and wSn, respectively, that infect D. sechellia (Giordano et al. 1995; Rousset and Solignac 1995). wHa and wSh also occur as single infections in D. simulans and in D. sechellia, respectively (Rousset and Solignac 1995). In contrast, wNo almost always co-occurs with wHa in doubly infected D. simulans individuals (James et al. 2002), and wSn seems to occur only with wSh (Rousset and Solignac 1995). D. simulans has three distinct mitochondrial haplotypes (siI, siII, siIII) associated with wAu/wRi (siII), wHa/wNo (siI), and wMa (siIII). The siI haplotype is closely related to the se haplotype found with wSh and wSn in D. sechellia (Ballard 2000b). wMa co-occurs with the siIII haplotype, which differs over its 13 protein-coding genes by only a single-base pair from the maI mitochondrial haplotype carried by wMau-infected D. mauritiana. A second haplotype (maII) is carried by only uninfected D. mauritiana (Ballard 2000a; James and Ballard 2000).

Figure 5.

A) A nuclear relative chronogram. B) A mitochondrial relative chronogram with co-occurring Wolbachia strains listed in parentheses. See the text for an interpretation of the results, including the artifactual resolution of the phylogeny of the D. simulans clade.

The lack of whole wMa genome data precludes us from confidently resolving the mode of wMau acquisition in D. mauritiana. However, mitochondrial relationships support the proposal of Ballard (2000b) that D. mauritiana acquired wMau and the maI mitochondrial haplotype via introgression from wMa-infected D. simulans carrying siIII. D. mauritiana mitochondria are paraphyletic relative to D. sechellia and D. simulans mitochondria (Solignac and Monnerot 1986; Satta and Takahata 1990; Ballard 2000a, 2000b), with maI sister to siIII and maII outgroup to all other D. simulans-clade haplotypes (see Figure 5). Of the nine genomes we assessed, all but one (uninfected-R44) carry the maI haplotype, and genotypes carrying maI are both wMau-infected (N = 5) and uninfected (N = 3). While wMa-infected D. simulans carry siIII, wNo-infected D. simulans carry siI. We estimate that wMau and wNo diverged about 55,000 years ago, with only 0.068% sequence divergence over 682,494 bp. Nevertheless, it seems implausible that wNo (versus wMa) was transferred directly to D. mauritiana as this requires horizontal or paternal transmission of wNo into a D. mauritiana background already carrying the maI mitochondrial haplotype. Although our nuclear result suggests a confident phylogenetic resolution of the D. simulans clade (Figure 5A), this is an artifact of the bifurcation structure imposed by the phylogenetic analysis. Population genetic analyses show a complex history of introgression and probable shared ancestral polymorphisms (Kliman et al. 2000) among these three species. Consistent with this, of the 20 nuclear loci we examined, 6 (aconitase, aldolase, bicoid, ebony, enolase, ninaE) supported D. mauritiana as the outgroup within the D. simulans clade, 7 (glyp, pepck, pgm, pic, ptc, transaldolase, wingless) supported D. sechellia as the outgroup, and 7 (esc, g6pdh, glys, pgi, tpi, white, yellow) supported D. simulans. With successive invasions of the islands and purely allopatric speciation, we expect the outgroup to be the island endemic that diverged first. Figure 5B indicates that the maII haplotype diverged from the other mtDNA haplotypes roughly when the clade diverged, with the other haplotypes subject to a complex history of introgression and Wolbachia-associated sweeps, as described by Ballard (2000b).

Ballard (2000b) estimated that siIII-maI diverged about 4,500 years ago, which presumably approximates the date of the acquisition of wMau (and siIII, which became maI) by D. mauritiana. This is surely many thousands of generations given previous estimates that consider the temperature dependence of Drosophila development (Cooper et al. 2014; Cooper et al. 2018). As shown by our mathematical analyses (Eq. 3), the apparent persistence of the maII mtDNA among Wolbachia-uninfected D. mauritiana––without its occurrence among infected individuals––is unexpected. More extensive sampling of natural D. mauritiana populations is needed to see if this unexpected pattern persists. The persistence of this haplotype is inconsistent with simple null models, possibly indicating interesting fitness effects.

While paternal transmission has been observed in D. simulans (Hoffmann and Turelli 1988; Turelli and Hoffmann 1995), it seems to be very rare (Richardson et al. 2012; Turelli et al. 2018). wNo almost always occurs in D. simulans individuals also infected with wHa, complicating this scenario further. It is possible that horizontal or paternal transmission of wMa or wNo between D. simulans backgrounds carrying different mitochondrial haplotypes underlies the similarities of these strains within D. simulans, despite their co-occurrence with distinct mitochondria. Given the diversity of Wolbachia that infect D. simulans-clade hosts, and known patterns of hybridization and introgression among hosts (Garrigan et al. 2012; Brand et al. 2013; Garrigan et al. 2014; Matute and Ayroles 2014; Schrider et al. 2018), determining relationships among these Wolbachia and how D. mauritiana acquired wMau will require detailed phylogenomic analysis of nuclear, mitochondrial, and Wolbachia genomes in the D. simulans clade.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Margarita Womack for sampling the D. mauritiana used in this study and Daniel Matute for sharing them. We thank Michael Gerth for sharing Nomada genomic data. Isaac Humble, Maria Kirby, and Tim Wheeler assisted with data collection. Michael Gerth, Michael Hague, Amelia Lindsey, and three anonymous reviewers provided comments that improved our manuscript. Computational resources were provided by the University of Montana Genomics Core. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R35GM124701 to B.S.C. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix 1. Mathematical analyses of mtDNA and Wolbachia dynamics

Our analysis follows the framework developed in Turelli et al. (1992), but is simplified by the lack of CI. We suppose that introgression introduces a cytoplasm carrying Wolbachia and a novel mtDNA haplotype, denoted B. Before Wolbachia introduction, we assume the population is monomorphic for mtDNA haplotype A. With imperfect maternal Wolbachia transmission, uninfected individuals will be produced with mtDNA haplotype B. Without horizontal or paternal transmission (which are very rare, Turelli et al. 2018), all Wolbachia-infected individuals will carry mtDNA haplotype B. Once Wolbachia is introduced, uninfected individuals can have mtDNA haplotype A or B. We assume that these three cytoplasmic types (“cytotypes”) differ only in fecundity, and denote their respective fecundities FI, FA and FB. Denote the frequencies of the three cytotypes among adults in generation t by pI,t, pA,t and pB,t, with pI,t + pA,t + pB,t = 1. Without CI, the frequency dynamics are

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

If the uninfected population is initially monomorphic for mtDNA haplotype A, the Wolbachia infection frequency will increase when rare if and only if

| (A3) |

Turelli et al. (1992) showed that if a CI-causing Wolbachia is introduced with a cytoplasm that contains a novel mtDNA haplotype B, which has no effect on fitness, Wolbachia-uninfected individuals will eventually all carry haplotype B. This follows because eventually all uninfected individuals have Wolbachia-infected maternal ancestors. This remains true for non-CI-causing Wolbachia that satisfy (A3). However, we conjectured that if the introduced B mtDNA is deleterious in the new host nuclear background, i.e., FA > FB, a stable polymorphism might be maintained for the alternative mtDNA haplotypes. The motivation was that imperfect maternal transmission seemed analogous to migration introducing a deleterious allele into an “island” of uninfected individuals. To refute this conjecture, consider the equilibria of (A1) with

| (A4) |

If all three cytotypes are to be stably maintained, we expect each to increase in frequency when rare. In particular, we expect the fitness-enhancing mtDNA haplotype A to increase when the population contains only infected individuals and uninfected individuals carrying the deleterious Wolbachia-associated mtDNA haplotype B. From (A1), pA,t increases when rare if and only if

| (A5) |

In the absence of haplotype A, we expect pI to be at equilibrium between selection and imperfect maternal transmission, i.e.,

| (A6) |

with F = FI/FB (Hoffmann and Turelli 1997). Substituting (A6) into (A5) and simplifying, the condition for pA,t to increase when rare is

| (A7) |

By assumption (A4), FI > FB; hence (A7) contradicts condition (A3), required for initial Wolbachia invasion. Thus, simple selection on Wolbachia-uninfected mtDNA haplotypes cannot stably maintain an mtDNA polymorphism. The “ancestral” mtDNA haplotype A is expected to be replaced by the less-fit Wolbachia-associated haplotype B.

To understand the time scale over which this replacement occurs, let rt denote the frequency of haplotype A among Wolbachia-uninfected individuals, i.e., rt = pA,t/(pA,t + pB,t). From (A1),

| (A8) |

If we assume that the mtDNA haplotypes do not affect fitness, i.e., FA = FB, and that the Wolbachia infection frequency has reached the equilibrium described by (A6), (A8) reduces to

| (A9) |

with F = FI/FB.

Footnotes

DATA ACCESSIBILITY STATEMENT

All phenotypic data, relevant genetic data, and scripts are archived in DRYAD (10.5061/dryad.17h7q4v). Illumina reads for D. mauritiana genotypes R60 (SRR8834567), R9 (SRR8834568), and R29 (SRR8834569) are available in GenBank (Bioproject: PRJNA530272). The R60 wMau assembly (GCA_004685025.1) is available in GenBank (Bioproject: PRJNA530278).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

LITERATURE CITED

- Baldo L, Ayoub NA, Hayashi CY, Russell JA, Stahlhut JK, and Werren JH. 2008. Insight into the routes of Wolbachia invasion: high levels of horizontal transfer in the spider genus Agelenopsis revealed by Wolbachia strain and mitochondrial DNA diversity. Molecular Ecolology 17:557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO 2000a. When one is not enough: introgression of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila. Molecular Biology and Evolution 17:1126–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JW 2000b. Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans. Journal of Molecular Evolution 51:64–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO 2004. Sequential evolution of a symbioint inferred from the host: Wolbachia and Drosophila simulans. Molecular Biology and Evolution 21:428–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JW, and Melvin RG. 2007. Tetracycline treatment influences mitochondrial metabolism and mtDNA density two generations after treatment in Drosophila. Insect Molecular Biology 16:799–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH, and Turelli M. 2011. Spatial waves of advance with bistable dynamics: cytoplasmic and genetic analogues of allee effects. American Naturalist 178:E48–E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann JF, and Fallon AM. 2013. Detection of the Wolbachia protein WPIP0282 in mosquito spermathecae: implications for cytoplasmic incompatibility. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 43:867–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann JF, Ronau JA and Hochstrasser M. 2017. A Wolbachia deubiquitylating enzyme induces cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature Microbiology 2:17007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, Weill M, Sicard M, and Charlat S. 2019. The toxin-antidote model of cytoplasmic incompatibility: genetics and evolutionary implications. Trends in Genetics in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boeva V, Popova T, Bleakley K, Chiche P, Cappo J, Schleiermacher G, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Delattre O, Barillot E. 2012. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28:423–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K, Dobson SL, Braig HR and O’Neill SL. 1998. Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked. Nature 391:852–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand CL, Kingan SB, Wu L and Garrigan D. 2013. A Selective Sweep across Species Boundaries in Drosophila. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:2177–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie JC, Cass BN, Riegler M, Witsenburg JJ, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. 2009. Evidence for Metabolic Provisioning by a Common Invertebrate Endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during Periods of Nutritional Stress. PLoS Pathogens 5:e1000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington LB, Lipkowitz JR, Hoffmann AA, and Turelli M. 2011. A re-examination of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in California Drosophila simulans. PLoS ONE 6:e22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari E, and Watson GS. 1959. On the evolutionary importance of cytoplasmic sterility in mosquitoes. Evolution 13:568–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cattel J, Nikolouli K, Andrieux T, Martinez J, Jiggins F, Charlat S, Vavre F, Lejon D, Gibert P, and Mouton L. 2018. Back and forth Wolbachia transfers reveal efficient strains to control spotted wing Drosophila populations. Journal of Applied Ecology 55:2408–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Conner WR, Blaxter ML, Anfora G, Ometto L, Rota-Stabelli O, and Turelli M. 2017. Genome comparisons indicate recent transfer of wRi-like Wolbachia between sister species Drosophila suzukii and D. subpulchrella. Ecology and Evolution 7:9391–9404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BS, Hammad LA, and Montooth KL. 2014. Thermal adaptation of cellular membranes in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Functional Ecology 28:886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BS, Ginsberg PS, Turelli M and Matute DR. 2017. Wolbachia in the Drosophila yakuba complex: pervasive frequency variation and weak cytoplasmic incompatibility, but no apparent effect on reproductive isolation. Genetics 205:333–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BS, Sedghifar A, Nash WT, Comeault AA, Matute DR. 2018. A maladaptive combination of traits contributes to the maintenance of a Drosophila hybrid zone. Current Biology 28:2940–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BS, Vanderpool D, Conner WR, Matute DR, and Turelli M. 2019. Introgressive and horizontal acquisition of Wolbachia by Drosophila yakuba-clade hosts and horizontal transfer of incompatibility loci between distantly related Wolbachia. bioRxiv. 10.1101/551036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- David J, McEvey S, Solignac M and Tsacas L. 1989. Drosophila communities on Mauritius and the ecological niche of D. mauritiana (Diptera, Drosophilidae). Revue De Zoologie Africaine – Journal of African Zoology 103:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dean MD, and Ballard JW. 2004. Linking phylogenetics with population genetics to reconstruct the geographic origin of a species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32:998–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, and Tibshirani R. 1993. An Introduction to the Bootstrap Chapman & Hall, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Ellegaard KM, Klasson L, Näslund K, Bourtzis K and Andersson SGE. 2013. Comparative Genomics of Wolbachia and the Bacterial Species Concept. PLoS Genetics 9:e1003381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast EM, Toomey ME, Panaram K, Desjardins D, Kolaczyk ED, Frydman HM. 2011. Wolbachia enhance Drosophila stem cell proliferation and target the germline stem cell niche. Science 334:990–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA 1937. The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Annals of Eugenics 7:355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D, Kingan SB, Geneva AJ, Andolfatto P, Clark AG, Thornton KR, Presgraves DC. 2012. Genome sequencing reveals complex speciation in the Drosophila simulans clade. Genome Research 22:1499–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D, Kingan SB, Geneva AJ, Vedanayagam JP and Presgraves DC. 2014. Genome diversity and divergence in Drosophila mauritiana: multiple signatures of faster X evolution. Genome Biology and Evolution 6:2444–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerth M, and Bleidorn C. 2016. Comparative genomics provides a timeframe for Wolbachia evolution and exposes a recent biotin synthesis operon transfer. Nature Microbiology 2:16241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano R, O’Neill SL and Robertson HM. 1995. Wolbachia infections and the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila sechellia and D. mauritiana. Genetics 140:1307–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliddon C and Strobeck C. 1975. Necessary and sufficient conditions for multiple-niche polymorphism in haploids. American Naturalist 109:233–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gloor GB, Preston CR, Johnsonschlitz DM, Nassif NA, Phillis RW, Benz WK, Robertson HM, Engels WR. 1993. Type-1 repressors of P-element mobility. Genetics 135:81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Vasanthakrishnan RB, Siva-Jothy J, Monteith KM, Brown SP, and Vale PF. 2017. The route of infection determines Wolbachia antibacterial protection in Drosophila. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284:20170809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm CA, Begun DJ, Vo A, Smith CCR, Saelao P, Shaver AO, Jaenike J, Turelli M. 2014. Wolbachia do not live by reproductive manipulation alone: infection polymorphism in Drosophila suzukii and D. subpulchrella. Molecular Ecology 23:4871–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haygood R, and Turelli M. 2009. Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes in subdivided host populations. Evolution 63:432–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL and Johnson KN. 2008. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322:702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A and Werren JH. 2008. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiology Letters 281:215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Turelli M, and Simmons GM. 1986. Unidirectional incompatibility between populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 40:692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, and Turelli M. 1988. Unidirectional incompatibility in Drosophila simulans: Inheritance, geographic variation and fitness effects. Genetics 119:435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, and Turelli M. 1997. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. In Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction, edited by O’Neill SL, Werren JH, and Hoffmann AA. Oxford University Press, pp. 42–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Clancy D and Duncan J. 1996. Naturally-occurring Wolbachia infection in Drosophila simulans that does not cause cytoplasmic incompatibility. Heredity 76:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Hercus M and Dagher H. 1998. Population dynamics of the Wolbachia infection causing cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 148:221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Turelli M, and Harshman LG. 1990. Factors affecting the distribution of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 126:933–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, Greenfield M, Durkan M, Leong YS, Dong Y, Cook H, Axford J, Callahan AG, Kenny N, Omodei C, McGraw EA, Ryan PA, Ritchie SA, Turelli M, and O’Neill SL. 2011. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476:454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhna S, Landis MJ, Heath TA, Boussau B, Lartillot N, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. 2016. RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Systematic Biology 65:726–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornett EA, Charlat S, Duplouy AMR, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N, and Hurst GDD. 2006. Evolution of male-killer suppression in a natural population. PLoS Biology 4:e283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huigens ME, de Almeida RP, Boons PA, Luck RF and Stouthamer R. 2004. Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271:509–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst GDD and Jiggins FM. 2000. Male-killing bacteria in insects: mechanisms, incidence, and implications. Emerging Infectious Diseases 6:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman SD, Vandervalk BP, Mohamadi H, Chu J, Yeo S, Hammond SA, Jahesh G, Khan H, Coombe L, Warren RL, Birol I. 2017. ABySS 2.0: resource-efficient assembly of large genomes using a Bloom filter. Genome Research 27:768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, and Ballard JWO. 2000. Expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and its impact on infection frequencies and distribution of Wolbachia pipientis. Evolution 54:1661–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, Dean MD, McMahon ME and Ballard JW. 2002. Dynamics of double and single Wolbachia infections in Drosophila simulans from New Caledonia. Heredity 88:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaprakash A, and Hoy MA. 2000. Long PCR improves Wolbachia DNA amplification: wsp sequences found in 76% of sixty-three arthropod species. Insect Molecular Biology 9:393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi NA, and Fass JN. 2011. Sickle: A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33) Available at https://github.com/najoshi/sickle.