Abstract

Background:

Ecological factors are important indicators for tuberculosis (TB) notification. However, consolidation of evidence on the effect of altitude and temperature on TB notification rate has not yet been done. The aim of this review is to illustrate the effect of altitude and temperature on TB notification rate.

Methods:

Electronic searches were undertaken from PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus databases. Hand searches of bibliographies of retrieved papers provided additional references. A review was performed using the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline.

Results:

Nine articles from various geographic regions were included in the study. Five out of nine studies showed the effect of altitude and four articles identified temperature effects. Results showed that TB notification rates were lower at higher altitude and higher at a higher temperature.

Conclusion:

This review provides qualitative evidence that TB notification rates increase with temperature and decrease with altitude. The findings of this review will encourage policymakers and program managers to consider seasonality and altitude differences in the design and implementation of TB prevention and control strategies.

Keywords: Altitude, notification, systematic review, temperature, tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Globally, over past decades, considerable effort has been undertaken in an attempt to control tuberculosis (TB).[1] However, TB remains a significant public health problem: in 2015, an estimated 10.4 million TB cases occurred, and 1.8 million people died with or from the disease (including 0.4 million among people with HIV).[2] The risk of transmission differs markedly by geographical area with noticeable heterogeneity within and among continents.[2,3] The notification rate is higher in poorer and remote areas, with the highest rate reported from the Southeast Asia region (61% of new cases), followed by Africa (26% of new cases).[2]

Socioeconomic and individual factors associated with TB such as ethnicity, place of residence, drug use, alcohol consumption, homelessness, human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, age, and sex have been investigated in numerous studies.[4,5,6]

Climate change plays an important role in the seasonality and geographical heterogeneity of TB notifications, although it is likely to be distally related to TB incidence.[7] Although published literature suggests there are no specific favorable or unfavorable climate conditions for TB incidence, transmission could be enhanced via poor ventilation and overcrowding.[8]

Variation in TB notifications associated with altitude and temperature, particularly for pulmonary TB, has been widely assumed.[9,10,11,12,13] The causative agent replicates more readily at higher temperatures. Furthermore, airflow is often high in hot conditions providing an environment conducive to the spread of TB.[13,14]

Epidemiological studies suggest that high altitude is associated with lower TB notification and mortality. However, the biological mechanisms underlining this apparent effect are poorly understood.[15,16,17] Furthermore, the effects of these factors have not been well studied and have not taken into account common confounding factors.[18]

Systematically summarizing the role of these factors on TB notification may help to provide relevant information to support TB control and prevention. Therefore, the aim of this review is to survey existing evidence on the altitude and temperature effects on TB notifications.

METHODS

We searched the PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus for all studies of the association between altitude and temperature and TB disease. We also hand searched bibliographies of retrieved papers for additional references. Data filtering used keywords, title, abstracts, and full-text reviews. EndNote was used to eliminate duplicated articles. The full search strategy is available as Supplement 1 (78KB, pdf) .

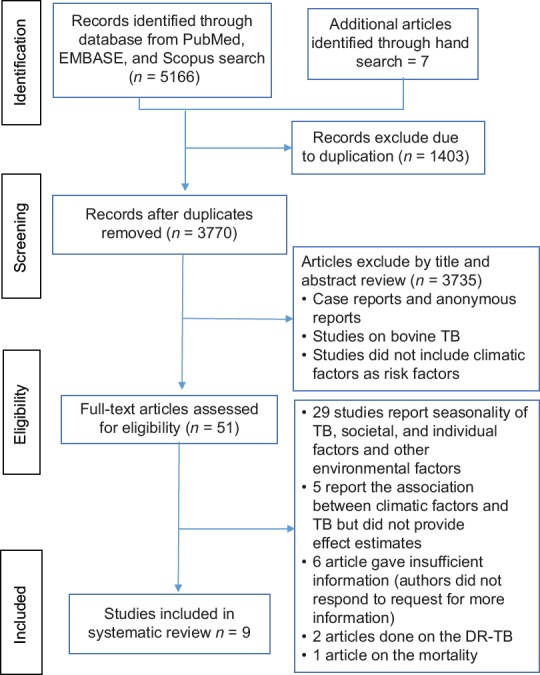

Our searches were limited to human studies. Studies were included if quantitative effect estimates of the relationship between temperature or altitude and TB (regardless of the clinical diagnosis and measure of morbidity) were presented or could be calculated from the data provided. Articles with any of the following: case reports, anonymous reports, studies on biomedical aspects of TB, and bovine TB were excluded from the study. Furthermore, studies conducted to assess risk factors other than temperature and altitude factors were not included in the study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search strategy for the effect of temperature and altitude difference on tuberculosis notification

For all included studies, location/country of the study, study period, study population, exposure temperature or altitude, outcome, TB notification (prevalence or incidence of TB), confounders adjusted for, and effect estimates such as mean, correlation, path coefficient, beta coefficient, relative risk (RR), and odds ratio (OR) were extracted by two independent reviewers (Y. G and W. Y) using a standard data extraction format. We used the following definition to standardize the data extraction process.

Tuberculosis notifications

TB cases (all forms of TB) were diagnosed biologically or clinically and confirmed cases registered and reported. Included papers defined TB morbidity as incidence, prevalence, or notification of TB. Nevertheless, to harmonize this, we defined notification as diagnosed and reported TB incidence/prevalence. The term notification will be used to encompass both incidence and prevalence in the present paper.

Temperature

Temperature measured in °C was obtained from the meteorology agency/Bureau of the appropriate country. It was defined as monthly or yearly average calculated from the daily/weekly/monthly records.

Altitude

The mean height above sea level, measured in meters (m), was obtained from geo-coordinates of the geographical location.

The reporting of this review follows the guidelines for the Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies (MOOSE).[19]

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies was used to assess the quality of the included papers [Supplement 2 (94.8KB, pdf) ].[20] Each article was rated for quality based on the three elements such as selection, comparability, and outcome and is presented in Supplement 3. All items in the three elements were evaluated irrespective of reporting.

SUPPLEMENT 3.

Table 3: Quality assessment of the impact of climate and altitude variability on tuberculosis transmission using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies

| Studies references | Selection (maximum 6 star) | Comparability (maximum 2 star) | Outcome (maximum 3 star) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | **** | ** | ** |

| 21 | *** | * | |

| 25 | *** | * | |

| 29 | ** | ** | ** |

| 27 | **** | ** | ** |

| 28 | ** | ** | *** |

| 23 | ** | ** | *** |

| 26 | ** | ** | * |

| 22 | **** | * | * |

*Scale score

A narrative review and a descriptive summary are given because of the variability in measures of temperature and analytical approaches, as well as in the definitions of control groups. Adjusted effects from studies on the association between altitude and TB notification were pooled with random effects. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation between studies compared to that within studies. Data were analyzed using MetaXL version 5.2 (EpiGear International).

RESULTS

Overall, 5166 references were first retrieved via the electronic database search: 956 articles from PubMed, 2866 from EMBASE, and 1344 from Scopus, and hand searching other literature sources yielded 7 studies. After removing duplicates, 3770 titles were screened. Finally, 9 studies from 5 countries were relevant for inclusion.[21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]

Of the 9 included articles, 7 were carried out in Asia, 1 in South America, and 1 in Africa. All eligible studies used clinical record linkage of governmental reports for the assessment of TB notification. In the included studies, a diagnosis of TB was made based on a combined evaluation of clinical, radiological, and laboratory features of the patients in line with the National TB Prevention and Control Programs. Four articles did not describe diagnostic methods.[21,23,26,28]

The identified articles were quite variable, reporting different effect estimates (eta correlation, RR, OR, path coefficient, and mean), different exposure scales, as well as different TB reporting (prevalence of TB, the incidence of TB, and TB notification).

Various statistical methods were used to examine the research questions relating to altitude and temperature and TB notification. Effect estimates included correlation coefficient methods (Pearson and eta correlation coefficients) and regression models (partial path coefficients, normal regression beta coefficients, and Bayesian models). Some articles used more than one method. None of the eligible studies adequately justified the sample size.

The measurement of temperature and altitude differed in different studies. The temperature in °C as monthly or annual averages and altitude in meter (m) were defined as categorical or continuous. Results of this review are presented as a qualitative summary of temperature and altitude factors on TB notification.

The five studies examining the association between altitude and notified TB cases were conducted in the following four countries: China, Turkey, Mexico, and Kenya.[22,23,26,27,28,30] Details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis of effect of climatic factors and altitude on tuberculosis

| Study | Country, Population | Study period | Outcome type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Japan, all registered TB cases of the Fukuoka Institute of Health | 2008-2012 | All forms of TB incidence (5904 TB cases) |

| 21 | China, all annual reported TB patients in 32 Mainland provinces | 2009-2013 | TB prevalence |

| 25 | Japan, TB patients registered in 46 prefectures Japanese TB registry | 1961-1978 | TB prevalence determined by clinicians by clinical factors |

| 29 | China, all TB patients in randomly selected medical institutions | 2009-2013 | TB incidence (n=27, 655 cases) |

| 27 | Turkey, all patients receive treatment in state TB dispensaries from randomly selected 56 cities | 1999-2005 | All forms of TB (378 TB cases; the mean incidence of TB per 100 k=23.8±9.1 [12.07-47.39]) |

| 28 | Mexico, all annual PTB notification cases registered obtained from Mexican Health Ministry database | 1998, 2002 | TB incidence |

| 23 | Kenya, all annual TB patient reports in 41 districts of National TB Program | 1988-1990 | TB prevalence |

| 26 | China, all registered TB cases from Chinese center of disease control and prevention management information system | 2007 | TB prevalence |

| 22 | China, all TB patients registered (in 31 provinces) China Health Statistics Yearbook | 2001-2010 | TB prevalence |

| Study | Exposure | Adjusted variable | Findings |

| 24 | Temperature (29.2°C) | Age, sex | Exposure to extreme heat temperature (RR=1.2, 95% CI: 1.01-1.43) |

| 21 | Monthly average temperature | NA | Average annual temperature (RR=1.00324, 95% CI: 1.00150-1.00550) |

| 25 | Annual average temperature (°C) | Sunshine hour | The monthly average temperature increase in 10°C TB incidence decrease by 9% (β=−0.0060, P<0.001) |

| 27 | Monthly average temperature (°C) | Latent variable; TB control programs, population density, income, public assist, past TB control, past epidemic | 29.9°C-39.8°C and 18.0°C-46.1°C temperature is associated with TB prevalence and incidence rate, respectively |

| 28 | Altitude defined as>750 m and 1-750 m | Green card, annual income, population density, household size, urbanization rate, number of doctors | There is inverse correlation between altitude and mean TB incidence (r=−0.58, 95% CI: −0.73-−0.38, P=0.000) The incidence higher in cities at an altitude <750 m versus >750 m (OR=3.28, 95% CI [1.83-5.88], P<0.0001) |

| 23 | Altitude above sea level (0-2500) | NA | Altitude above sea level correlated with TB incidence (r=−0.74, 95% CI: −0.87-−0.53, P<0.0001) |

| 26 | Altitude | Nomads, population density, literacy rate, household size, life expectancy rate, nutritional status | The log notification rates negatively associated with altitude (r=−0.71, 95% CI: −0.51-0.83, P<0.001) |

| 22 | Altitude | Air quality, education, health service, population density, economic level, unemployment | Altitude factor (−0.595) had a significant effect on TB prevalence |

NA: No information about variable adjustment, TB: Tuberculosis, CI: Confidence interval, RR: Relative risk, OR: Odds ratio

The studies conducted in China in 2014 and 2015 reported that altitude is associated with TB notifications. A 2014 study showed that TB notifications increased in high-altitude regions (path coefficient = 0.5953), whereas in a 2015 study, the notifications decreased (path coefficient = −0.595).[22,26]

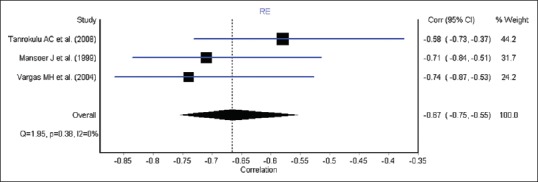

The retrospective study conducted from 1999 to 2005 in 56 randomly selected Turkish cities involving 378 patients showed that the mean number of TB notifications decreased in high altitude (r = −0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.73, −0.38): TB notifications were higher in cities at altitudes below 750 m than for cities located above 750 m (OR = 3.28, 95% CI: 1.83, 5.88, P = 0.001).[27]

The Mexico study found that altitude above sea level was correlated with low TB notifications in 2014 (r = −0.74, 95% CI: −0.87, −0.53, P = 0.001).[28] The Kenya study also reported that TB notifications were lower at higher altitudes (r = −0.071, 95% CI: −0.51, −0.83, P = 0.001).[23]

Although five studies reported the relationship between altitude and TB incidence, three articles were eligible for meta-analysis, since two articles did not report effect estimates. We report the pooled estimates correlation between altitude and TB incidence for these studies. All the three studies found a negative association between altitude and TB notification [Figure 2]. The pooled correlation between altitude and TB notifications was r = −0.67 (95% CI: −0.75, −0.55).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of correlation between altitude and tuberculosis

Studies of the association between temperature and TB notifications were conducted in three countries such as China, Japan, and Iran.[21,24,25,29] Given the heterogeneity of methods among studies, we did not compute pooled effect estimates. Table 1 shows the individual effect measures for the studies on TB notification; one study found a negative association between temperature and TB notification; with a 10°C increasing monthly average temperature, the monthly notifications of TB decreased by 9% (β = −0.0060, t = −5.12, P < 0.001).[25]

Temperature was associated with TB notifications in three studies. The 15-year retrospective review of 46 Japanese prefectures showed that temperature was associated with TB notifications when between 18.0°C and 46.1°C. The 4-year Fukuoka Institute of Health Registry study of 5904 TB cases, carried out three decades later, showed that exposure to extreme heat (RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.01–1.43) increased the risk of TB notification.[24] However, effect estimates related to risk were not provided in the article.[29] The study done in mainland China, using a Bayesian model, reported that the risk of a TB notification increased with a one-degree increase in temperature (RR = 1.00324, 95% CI: 1.0015–1.0055).[21]

DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to examine whether temperature or altitude affected TB notification. Studies found were geographically varied, small, and did not adjust for important confounders. However, regardless of study duration, geographical coverage, and heterogeneity of analytical approaches and effect sizes, this review demonstrated an increasing effect of temperature on TB notification rates, except for one study associated with low notification rates.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TB notification is associated with socioeconomic conditions.[4,5,6] Our review indicates that TB notification is high in areas where the temperature was high, except for Qinghai province where TB notification decreases exponentially for each 10°C. This is potentially due to differences in the temperature measurement (monthly/annually). As well, seasonality, social context, and medical and health conditions of the residents in Qinghai province could influence TB transmission.[25] Specifically, overcrowding, the amount of co-infection with HIV, malnutrition, and type 2 diabetes have been implicated.[31] Our findings support the notion that lower altitudes are advantageous for TB transmission, since TB notifications declined with increasing altitude.[32] This might be explained by lower levels of crowding and population density at higher altitude, with residents not staying indoors for long periods.[13,25,33,34] In addition, UV-B exposure is higher at higher altitudes, leading to higher levels of Vitamin D which might enhance immune response and decrease consequent reactivation of TB.[30,35]

Limitations of this review include those related to residual confounding, measurement of the exposure variable, and lack of an established mechanism underlying the apparent effect of temperature and altitude on TB. Some studies did not adjust for known drivers of TB during analysis and included latent (unmeasured) variables in the analysis. Climate factors associated with TB are likely to operate as secondary factors, unlike proximal factors such as HIV. Therefore, well-designed studies on the direct and indirect effects of temperatures and/or altitude factors on TB transmission are needed. In addition, the review did not control for year of the study published (1981–2016), sample size (not all studies reported), socioeconomic characteristics, and the health profile of each country.

Other possible limitations relate to inconsistencies in the classifications of temperature (hot and cold) and altitude (highland and sea level) which could lead to misclassification bias. In addition, analyses are restricted to TB notifications which may not reflect the timing of actual incidence, thus leading to mismatch when notifications are linked to time-dependent climate data.

Finally, most studies (seven studies) in the review used retrospective registry-based community-level data sources and findings may not be the same for individual-level data, that is, findings could be vulnerable to the ecological fallacy. Despite limited data, heterogeneity of measurements, design, and quantitative effect estimates among the studies were included in this review; this systematic literature review demonstrates that temperature/altitude is associated with TB disease notifications. This should encourage policymakers and program managers to consider seasonality and altitude differences in the design and implementation of TB prevention and control strategies.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mr. Scott Macintyre for his unreserved professional guidance during electronic database searching.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raviglione MC, Uplekar MW. WHO's new stop TB strategy. Lancet. 2006;367:952–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68392-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2016. Report No.: 924156539X. World Health Organization. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ormerod LP, Charlett A, Gilham C, Darbyshire JH, Watson JM. Geographical distribution of tuberculosis notifications in national surveys of England and Wales in 1988 and 1993: Report of the Public Health Laboratory Service/British Thoracic Society/Department of Health Collaborative Group. Thorax. 1998;53:176–81. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nava-Aguilera E, Andersson N, Harris E, Mitchell S, Hamel C, Shea B, et al. Risk factors associated with recent transmission of tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurmi OP, Sadhra CS, Ayres JG, Sadhra SS. Tuberculosis risk from exposure to solid fuel smoke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:1112–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses: Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumpter C, Chandramohan D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the associations between indoor air pollution and tuberculosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:101–8. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knopf SA. Climate in tuberculosis and the prevention of relapses. JAMA. 1931;96:2023–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fourie P, Knoetze K. Tuberculosis prevalence and risk of infection in Southern-Africa. S Afr J Sci. 1986;82:387. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates JH. Transmission and pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Clin Chest Med. 1980;1:167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biello D. Deadly by the Dozen: 12 Diseases climate change may Worsen. Sci Am. 2008;8:12–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fares A. Seasonality of tuberculosis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:46–55. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.77296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vardoulakis S, Dimitroulopoulou C, Thornes J, Lai KM, Taylor J, Myers I, et al. Impact of climate change on the domestic indoor environment and associated health risks in the UK. Environ Int. 2015;85:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trask JW. Climate and tuberculosis: The relation of climate to recovery. Public Health Rep (1896-1970) 1917;23:318–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anigbo AR, Choudhary RC. The effects of climate change on tuberculosis. J Environ Sci Technol. 2018;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peers RA. The influence of climate upon tuberculosis; with remarks on the climate of Colfax, California. Cal State J Med. 1909;7:106–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberg JN, Desai MA, Levy K, Bates SJ, Liang S, Naumoff K, et al. Environmental determinants of infectious disease: A framework for tracking causal links and guiding public health research. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1216–23. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2011. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 07]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

- 21.Cao K, Yang K, Wang C, Guo J, Tao L, Liu Q, et al. Spatial-temporal epidemiology of tuberculosis in Mainland China: An analysis based on bayesian theory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:pii: E469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13050469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li XX, Wang LX, Zhang J, Liu YX, Zhang H, Jiang SW, et al. Exploration of ecological factors related to the spatial heterogeneity of tuberculosis prevalence in P. R. China. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23620. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansoer JR, Kibuga DK, Borgdorff MW. Altitude: A determinant for tuberculosis in Kenya? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:156–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onozuka D, Hagihara A. The association of extreme temperatures and the incidence of tuberculosis in Japan. Int J Biometeorol. 2015;59:1107–14. doi: 10.1007/s00484-014-0924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao HX, Zhang X, Zhao L, Yu J, Ren W, Zhang XL, et al. Spatial transmission and meteorological determinants of tuberculosis incidence in Qinghai province, China: A spatial clustering panel analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:45. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0139-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun W, Gong J, Zhou J, Zhao Y, Tan J, Ibrahim AN, et al. Aspatial, social and environmental study of tuberculosis in China using statistical and GIS technology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:1425–48. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120201425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanrikulu AC, Acemoglu H, Palanci Y, Dagli CE. Tuberculosis in Turkey: High altitude and other socio-economic risk factors. Public Health. 2008;122:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas MH, Furuya ME, Pérez-Guzmán C. Effect of altitude on the frequency of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:1321–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagawa H, Hara N, Hashimoto T, Yokoyama H, Tachibana K. Geographical pattern of tuberculosis and related factors in Japan. Soc Sci Med Med Geogr. 1981;15D:141–8. doi: 10.1016/0160-8002(81)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olender S, Saito M, Apgar J, Gillenwater K, Bautista CT, Lescano AG, et al. Low prevalence and increased household clustering of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in high altitude villages in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:721–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: The role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boere TM, Visser DH, van Furth AM, Lips P, Cobelens FG. Solar ultraviolet B exposure and global variation in tuberculosis incidence: An ecological analysis. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:pii: 1601979. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01979-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell-Lendrum D, Pruss-Ustun A, Corvalan C. Climate Change and Human Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. How much disease could climate change cause; pp. 133–58. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rieder HL. Epidemiologic basis of Tuberculosis Control. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 1999. pp. 1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies PD. A possible link between Vitamin D deficiency and impaired host defence to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tubercle. 1985;66:301–6. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(85)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.