Abstract

Isoprenoids are constructed in nature using hemiterpene building blocks that are biosynthesized from lengthy enzymatic pathways with little opportunity to deploy precursor-directed biosynthesis. Here, an artificial alcohol-dependent hemiterpene biosynthetic pathway was designed and coupled to several isoprenoid biosynthetic systems, affording lycopene and a prenylated tryptophan in robust yields. This approach affords a potential route to diverse non-natural hemiterpenes and by extension isoprenoids modified with non-natural chemical functionality. Accordingly, the prototype chemo-enzymatic pathway is a critical first step towards the construction of engineered microbial strains for bioconversion of simple scalable building blocks into complex isoprenoid scaffolds.

Keywords: isoprenoids, terpenoids, hemiterpene, kinase, lycopene, prenyltransferase

Graphical Abstract

Isoprenoids comprise >55,000 natural products for which methods to access and diversify their structures are in high demand.1–3 Ultimately, the isoprene motif plays a critical role in modulating the biological activity of isoprenoids, determines their utility as tools to study and treat human diseases, and provides the basis to develop new fuels and chemicals.4–7 Notably, although several valuable isoprenoids have been accessed via heterologous expression,8–11 our ability to diversify isoprenoids is extremely limited largely due to critical limitations imposed by native isoprenoid biosynthesis. Firstly, only the mevalonate (MEV) and 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) pathways (Figure 1A) are known to produce the universal hemiterpene isoprenoid diphosphate building blocks, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP).12, 13 The negatively charged hemiterpenes are not cell permeable, thus preventing feeding them or analogues thereof into cultures. The MEV and DXP pathways involve at least six enzymatic steps13 each with stringent substrate specificity and therefore offer little opportunity to diversify the structures of isoprenoids through feeding in non-natural precursors.14 As a result, while precursor-directed biosynthesis has proven a powerful approach to access diverse structures of natural products15, 16—especially polyketides17–21—by feeding non-natural building blocks, this approach has not yet been applied to isoprenoids. Furthermore, late-stage biosynthetic modification of isoprenoid scaffolds is typically limited to oxidations, often catalyzed by P450’s.11, 22 Secondly, terpene metabolism is highly regulated and is a burden to the carbon supply on the cell.23 For example, the MEV pathway uses three molecules of phosphate donor (ATP) and two reducing equivalents (NADPH) for each DMAPP/IPP, while the DXP pathway requires two phosphate donors (ATP and CTP) and two reducing equivalents (NADPH) (Figure 1A).13 Thirdly, given that native terpenes are typically essential for maintenance of the cell, genetic modification of native hemiterpene pathways would likely be lethal.24 Together, these limitations could be overcome by supplying a membrane-permeable carbon building block dedicated for a designer pathway that would function independent of native isoprenoid metabolism. A potential strategy for hemiterpene biosynthesis could start with isopentenol (ISO) and dimethylallyl alcohol (DMAA) which are converted to the required diphosphates via stepwise phosphorylation catalyzed by two independent kinases (Figure 1B). This proposed alcohol-dependent hemiterpene (ADH) pathway is completely orthogonal to the endogenous DMAPP/IPP biosynthetic machinery, such that non-natural precursors are not expected to inhibit endogenous enzymatic machinery. In addition, the ADH pathway requires only two equivalents of ATP and no other cofactors. Furthermore, an artificial pathway designed ‘bottom-up’ as a replacement for natural hemiterpene biosynthesis could leverage naturally or engineered promiscuous enzymes. In this way, the ADH pathway could enable a broad panel of easily scalable and accessible alcohols to be converted to the corresponding diphosphate, thus providing a simple strategy to probe the plasticity of downstream isoprenoid biosynthesis in vivo or in vitro. In this study, as a necessary first step to realizing this goal, we report the design and development of a prototype ADH pathway that is completely orthogonal to native hemiterpene biosynthesis. The ability of this pathway to access isoprenoids is demonstrated by coupling the ADH pathway to two different isoprenoid biosynthetic systems.

Figure 1.

Natural and engineered hemiterpene biosynthetic pathways. (A) The MEV and DXP (grey box) pathways. A branch of the MEV pathway, the archaeal MEV I pathway, is shown in blue. For full names of enzymes, see ref12. (B) An artificial alcohol-dependent hemiterpene (ADH) pathway completely decoupled from native isoprenoid metabolism.

Inspired by the observation that several mammalian cell lines convert farnesol and farnesol analogues to the corresponding disphosphates,25–27 it was first determined whether E. coli harbors suitable enzymatic machinery that could convert exogenously provided ISO or DMAA into a pool of hemiterpenes for isoprenoid production. To test this, a previously reported reporter system that leverages lycopene biosynthesis was used that includes genes from the CrtEBI operon, a geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (CrtE or IspA Y80D), and the isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase ipi (Figure 2A).28 In E. coli, this reporter system expresses genes that use pools of hemiterpenes to generate the lycopene pigment, enabling quantification.28, 29 The intensity of the absorbance at 450–470 nm is directly associated with an increase in hemiterpene production given that the reporter system itself is not rate limiting.30–33

Figure 2.

Lycopene reporter system and preliminary characterization of IPK. (A) The reporter system module generates lycopene from cellular hemiterpenes. Fs is expected to inhibit native hemiterpene biosynthesis via the DXP pathway but not an artificial alcohol-dependent hemiterpene pathway. (B) E. coli BL21Tuner(DE3) harboring pCDFDuet-GGPP, pACYCDuet-Lyc and pETDuet-IPK in wells of a microplate were treated with combinations of IPTG, DMAA/ISO, and Fs and visualized.

The native DXP pathway in the E. coli reporter strains supports production of lycopene independently of exogenously added DMAA/ISO. Because of this, fosmidomycin (Fs), an inhibitor of the first dedicated step in hemiterpene biosynthesis (Figure 1A),34, 35 was leveraged to knockdown endogenous lycopene production in order to determine whether any endogenous machinery could support conversion of DMAA/ISO to hemiterpenes (Figure 2A). Fs was added to the culture medium at sufficient concentration (0.5 μM) to inhibit the DXP pathway34 but at low enough concentration growth was not significantly suppressed. In this way, the goal was to employ Fs to prevent accumulation of excess DXP-dependent hemiterpene, forcing production of lycopene solely from the exogenously fed precursors via potential unknown endogenous enzymes. Following addition of DMAA and ISO (each at 2.5 mM) and Fs (0.5 μM) to an overnight culture of E. coli BL21Tuner(DE3) harboring the lycopene reporter plasmids pCDFDuet-GGPP + pACYCDuet-Lyc, lycopene production was quantified by visual examination of the culture broth. However, no difference in lycopene production was observed upon comparison of the E. coli strain to an otherwise identical culture prepared in the absence of DMAA/ISO (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, the E. coli native metabolism does not support conversion of the ISO/DMAA mixture to lycopene at a rate greater than the inhibited DXP-pathway. Thus, our efforts shifted to identification of enzymes that could be heterologously expressed in E. coli and function as kinase- 2 in the proposed ADH pathway.

A protein recently found in archaea, isopentenyl phosphate kinase (IPK),36, 37 is responsible for the generation of IPP from isopentenyl phosphate (IP) and forms a branch of the MEV pathway called the Archaeal MEV Pathway I (Figure 1A). Over-expression of IPK in E. coli could lead to improved production of lycopene from exogenously added ISO if (1) an endogenous kinase (kinase-1, Figure 1B) can convert ISO to the corresponding monophosphate, and (2) the obligatory second phosphorylation (Figure 1B) contributes to the rate-limiting step in the conversion of ISO to lycopene in E. coli. To test these assumptions, a codon-optimized gene sequence for ipk from Thermoplasma acidophilum (Supplementary Table S1) was expressed in a strain of E. coli harboring a lycopene reporter module and was incubated either in the presence or absence of supplementary DMAA/ISO, IPTG, and Fs. The expression of IPK clearly resulted in increased lycopene (compare 1–3, Figure 2B). In addition, the presence of Fs almost completely inhibited lycopene production (2 vs. 4, Figure 2B). However, an increase in lycopene production was observed when the Fs-treated E. coli cultures that expressed IPK were supplemented with DMAA/ISO (Figure 2B). This increase in lycopene production that was dependent on IPK and DMAA/ISO validates the assumption that an endogenous kinase is capable of providing IPP from DMAA/ISO and that IPK supports the second required phosphorylation.

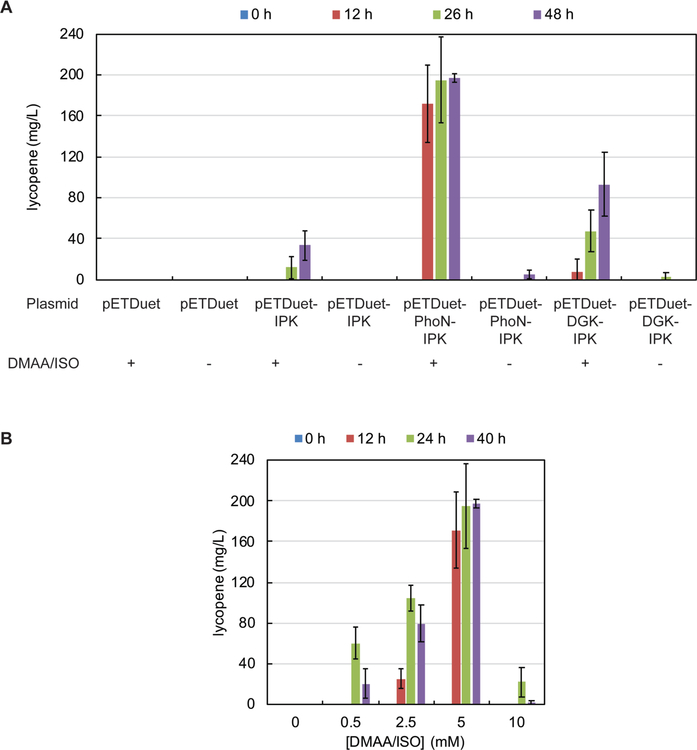

It was reasoned that over-expression of the E. coli gene product putatively responsible for DMAA/ISO phosphorylation would result in improved production of hemiterpenes. In a preliminary attempt to identify a suitable enzyme that could act as ‘kinase-1’ (Figure 1B), a set of 12 soluble alcohol kinases from E. coli, S. cerevisiae and A. thaliana, in addition to PhoN, a class-A non-specific acid phosphatase from Shigella flexneri (Supplementary Table S2) were cloned, expressed in E. coli, subjected to immobilized-metal affinity chromatography, and analyzed for their ability to phosphorylate DMAA/ISO by LC-MS analysis. PhoN was included in this set as it has previously been shown to phosphorylate various alcohols in vitro.38, 39 Notably, while none of the kinases displayed the desired activity (data not shown), mass ions consistent with DMAPP (calculated 165.0317 m/z, [M-H]−; observed 165.0318 m/z, [M-H]−) and IPP (calculated 165.0317 m/z, [M-H]−; observed 165.0317 m/z, [M-H]−) were detected in the presence of PhoN. Another potential candidate for kinase-1 is a membrane-associated diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) from Streptococcus mutans which is known to display undecaprenol-kinase activity.40 Given that DGK is membrane-bound, it was tested in vivo. In parallel, PhoN was also tested in vivo to ensure that its activity could contribute to isoprenoid biosynthesis. Accordingly, PhoN and DGK (Supplementary Table S1) were each cloned into pETDuet-IPK and tested for their ability to support isoprenoid production in an E. coli lycopene strain by extraction and HPLC-based quantification of the pigment (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S2). Remarkably, the prototype PhoN-IPK system was capable of converting DMAA/ISO to lycopene in titers of ~150 mg/L in E. coli after 12 hours post-induction (Figure 3A). These titers are comparable to that of an optimized engineered DXP pathway (24 mg/L)41 and heterologous production of the MEV pathway (102 mg/L) in E. coli.31 As expected, the activity was largely dependent on the presence of PhoN given that 17-fold less lycopene was produced at 26 hours post-induction when PhoN is absent. In addition, wild-type DGK could support lycopene production in good yields, although these were 4-fold lower than that with PhoN after 24 hours.

Figure 3.

Lycopene titers supported by engineered E. coli strains. (A) Lycopene titers are shown at 0, 12, 26, or 48 h post induction, in the presence or absence of DMAA/ISO, using E. coli NovaBlue(DE3) harboring pAC-LYCipi and the indicated plasmid with Fs treatment. Values are the average of three replicates. Error bars are the standard deviation. (B) Substrate dependence of lycopene titers determined at 0, 12, 26, or 40 h post induction with the strain harboring pETDuet-PhoN-IPK + pAC-LYCipi with Fs treatment. Values are the average of three replicates. Error bars are the standard deviation.

Next, to determine whether the lycopene titers were dependent on the concentration of the exogenously provided alcohol substrates, a series of lycopene assays were carried out at various concentrations of DMAA/ISO using the strain harboring pETDuet-PhoN-IPK/pAC-LYCipi in the presence of Fs (Figure 3B). After 24 hours, the prototype strain produced ~60 mg/L lycopene at 0.5 mM each of DMAA/ISO, ~100 mg/L at 2.5 mM each of DMAA/ISO, and ~190 mg/L at 5 mM each of DMAA/ISO (Figure 3B). At concentrations of 10 mM, DMAA/ISO supported a maximum lycopene titer of ~20 mg/L after 24 hours.

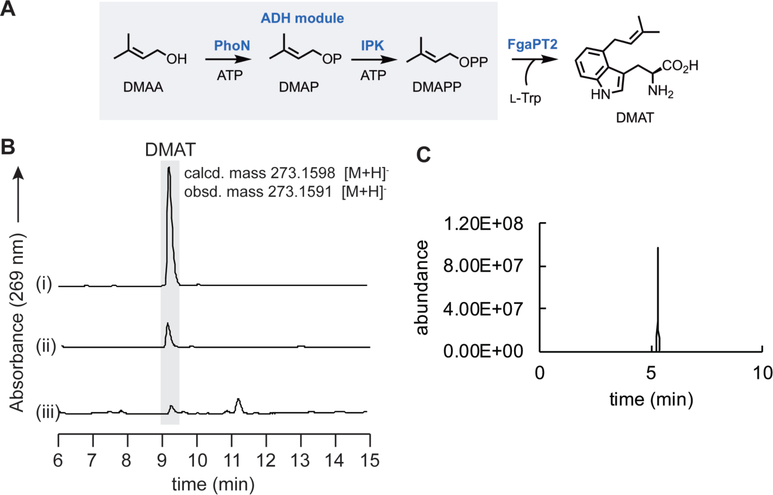

As an additional test of the ability of the designed prototype strain to provide an isoprenoid building block, the PhoN-IPK pathway was used to provide DMAPP which was then transferred to L-Trp using the prenyltransferase (PTase) FgaPT242 by providing an additional plasmid that expressed the PTase (Figure 4A). First, an in vitro reaction using purified FgaPT2 and a DMAPP standard confirmed production of a single product by HPLC and LC-MS analysis of the product mixture (Figure 4B), the mass of which (273.1591 m/z, [M+H]+) was consistent with the expected regioselectively mono-alkylated product, dimethylallyl-L-Trp (DMAT, calculated 273.1598 m/z, [M+H]+). In addition, using purified PhoN, IPK, and FgpaPT2 in a one-pot reaction, the same DMAT product was detected when DMAA was included in the in vitro reaction mixture (Figure 4B), confirming the ability of the ADH pathway to produce the required prenyl donor for FgaPT2. To test the ability of the in vivo system to provide the hemiterpene and couple it with the PTase, DMAA/ISO were fed into E. coli that harbored the ADH module (pETDuet-PhoN-IPK) in conjunction with a plasmid that harbored the PTase (pCDFDuet-FgaPT2), and after protein expression, HPLC confirmed the presence of the expected product (DMAT) in the culture media with an elution time indistinguishable from that produced by both in vitro reactions (Figure 4B). As expected from the in vitro reactions, an extracted-ion chromatogram of the culture media revealed a single peak corresponding to the mass ion for DMAT (Figure 4C). By using the in vitro FgaPT2-catalyzed conversion of L-Trp and DMAPP to DMAT as a calibration standard (the reaction went to completion), the ADH-FgaPT2 pathway in E. coli was judged to support the production of DMAT at ~20 mg/L. Furthermore, according to HPLC analysis, DMAT was not detected in negative controls that lacked either the alcohol or FgaPT2. Consistent with this observation, HR-MS analysis revealed that DMAT was present in 100-fold lower in abundance in the negative controls as compared to the positive reaction (data not shown). Together, this data confirms that the artificial ADH module is required for high-level production of the prenylated product.

Figure 4.

Tryptophan prenylation via the artificial alcohol-dependent hemiterpene pathway. (A) Reaction scheme of the ADH pathway coupled to the prenyltransferase, FgaPT2. (B) HPLC chromatograms showing peaks corresponding to DMAT: (i) in vitro FgaPT2 reaction with synthetic DMAPP; (ii) in vitro reaction with purified PhoN, IPK, and FgaPT2; (iii) culture media from in vivo bioconversion with the ADH module. The chromatograms are scaled equally. (C) Extracted-ion chromatogram showing a single peak corresponding to DMAT in the culture media of E. coli Rosetta(DE3) pLysS+pETDuet-PhoN-IPK+pCDFDuetFgaPT2 after treatment with DMAA/ISO, and IPTG.

In summary, an artificial hemiterpene biosynthetic pathway dependent on the exogenous addition of DMAA/ISO was developed. The prototype ADH pathway performed similarly to previously established routes that depend on building blocks from primary metabolism. It is expected that ribosome binding site and/or promoter engineering can be leveraged to optimize the productivity of the pathway further. Notably, although previous synthetic biology efforts have for example constructed a new entry point into the DXP pathway43 and provided new routes to DXP,44, 45 to the best of our knowledge, the ADH pathway described here is the first to transform scalable simple precursors directly into the required pyrophosphates and couple them to isoprenoid biosynthesis. This provides a simple strategy to provide isoprenoids in good yields given that only two enzymes and DMAA/ISO need to be provided. Indeed, in the absence of ISO/DMAA, there was insufficient endogenous DMAPP in E. coli to support high level production of the prenylated tryptophan, even when Fs was not used to inhibit the native DXP pathway. Given the cost of prenol, it is unlikely that the strategy described here will be used to access isoprenoids at industrial scale. It has however been designed primarily as a future discovery tool that potentially enables for the first time the in vivo biosynthesis of hemiterpene analogues, and by extension, non-natural isoprenoids. For example, PhoN displays a broad specificity in vitro, and this is expected to extend to the in vivo system here. Furthermore, several features of PhoN have been previously targeted by enzyme engineering, including shifting its pH optima for neutral media46 and improving its kinase activity with concomitant reduction in phosphatase activity.47, 48 Similarly, although the promiscuity of IPK is largely under-explored, its substrate interacts with the enzyme active site through electrostatic forces dictated by the phosphate portion of the substrate, while the remaining alkyl portion of the substrate is simply sterically accommodated.49 Indeed, the substrate specificity of IPK has been expanded to include geranyl- and farnesylphosphate.50 An expanded set of non-natural hemiterpenes provided by the prototype or engineered ADH pathway could be coupled with downstream enzymes to probe the promiscuity and utility of isoprenoid biosynthesis. For example, it is expected that this precursor-directed approach to non-natural isoprenoids will be readily extendible to natural product scaffolds that include L-Trp and/or other aromatics given the previously reported promiscuity of aromatic PTases.51–54 Subsequently, the ADH pathway may enable the production of prenylated and terpene natural products with non-natural alkyl groups expanding upon the limited chemical diversity afforded by nature.

METHODS

General

All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Purifications of all DNA were performed with kits from BioBasic. Lycopene standard was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA, USA). Plasmid pAC-LYCipi was purchased from Addgene (Plasmid #53279, Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). Polymerase chain reactions were conducted using Phire Hot Start II DNA Polymerase from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Lycopene quantification

E. coli NovaBlue (DE3) containing pAC-LYCipi and various pETDuet constructs were grown in 250 mL LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL) at 37 °C overnight with shaking at 250 rpm after inoculation with 0.25 mL of the starter culture. After 5 h the OD600 of the culture was ~0.2 at which point combinations of DMAA/ISO (in DMSO), IPTG, and Fs were added to give final concentrations of 5 mM, 1 mM, and 0.5 μM, respectively. In controls that lacked DMAA/ISO, DMSO was added to give the equivalent volume. At various time points, 600 μL of culture was removed and lycopene extracted and quantified (see the Supplemental Methods).

In vitro FgaPT2 assay

FgaPT2 reactions were run at pH 7.5 in 200 μL containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM L-tryptophan, 2 mM DMAPP, and 40 μg of FgaPT2. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then quenched by the addition of an equal volume of methanol. Reactions with PhoN-IPK generated DMAPP contained 25 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM magnesium chloride, 1 mM L-tryptophan, 1.8 mM ATP, 30 mM DMAA, 270 ng/μL FgaPT2, 20 ng/μL IPK, and 87 ng/μL PhoN at pH 8.0 in a total volume of 50 μL. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C overnight and then quenched by the addition of an equal volume of methanol. For analytical-scale HPLC analysis, FgaPT2 reactions were followed at 269 nm using a Phenomenex Kinetex 5u EVO C18 column (250 x 4.6 mm; 100 Å) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A linear gradient of 20–70% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid over 20 min was used.

In vivo FgaPT2 assay

A 3 mL culture of E. coli Rosetta(DE3) pLysS pETDuet-PhoN-IPK+pCDFDuetFgaPT2 was grown overnight at 37 °C and 250 rpm in LB media containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). An aliquot (100 μL) of overnight culture were used to inoculate 10 mL cultures in TB media containing the same antibiotics as before, and those cultures were grown at 30 °C for 6 h at 250 rpm until induction with 0.5 mM IPTG (final concentration) and addition to a final concentration of 5 mM DMAA, 5 mM ISO, and 10 mM Trp. The cultures were grown for 48 h after induction. The culture supernatant was diluted 1:1 in methanol before analysis by HPLC and LC-MS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant GM104258 (G.J.W.). All high resolution LC-MS measurements were made in the Molecular Education, Technology, and Research Innovation Center (METRIC) at NC State University.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Includes supplementary tables, supplemental figures, and detailed methods that describe: cloning candidate kinase genes; screening of kinases for phosphorylation of ISO and DMAA; synthesis of DMAPP/IPP; preliminary colorimetric screening of IPK; cloning of IPK, PhoN, DGK, and FgaPT2; expression and purification of PhoN, IPK, and FgapT2; extraction and quantification of lycopene; and lycopene standard curve.

References

- 1.Christianson DW (2008) Unearthing the roots of the terpenome, Curr Opin Chem Biol 12, 141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vickers CE, Williams TC, Peng B, and Cherry J (2017) Recent advances in synthetic biology for engineering isoprenoid production in yeast, Curr Opin Chem Biol 40, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang MC, and Keasling JD (2006) Production of isoprenoid pharmaceuticals by engineered microbes, Nat Chem Biol 2, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhassan AM, Abdullahi MI, Uba A, and Umar A (2014) Prenylation of aromatic secondary metabolites: a new frontier for development of novel drugs, Trop J Pharm Res 13, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollinsky B, Ludwig L, Hamacher A, Yu X, Kassack MU, and Li SM (2012) Prenylation at the indole ring leads to a significant increase of cytotoxicity of tryptophan-containing cyclic dipeptides, Bioor Med Chem Lett 22, 3866–3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George KW, Alonso-Gutierrez J, Keasling JD, and Lee TS (2015) Isoprenoid drugs, biofuels, and chemicals--artemisinin, farnesene, and beyond, Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 148, 355–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beller HR, Lee TS, and Katz L (2015) Natural products as biofuels and bio-based chemicals: fatty acids and isoprenoids, Nat Prod Rep 32, 1508–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KE, Wang Y, Simeon F, Leonard E, Mucha O, Phon TH, Pfeifer B, and Stephanopoulos G (2010) Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli, Science 330, 70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuruta H, Paddon CJ, Eng D, Lenihan JR, Horning T, Anthony LC, Regentin R, Keasling JD, Renninger NS, and Newman JD (2009) High-level production of amorpha-4,11-diene, a precursor of the antimalarial agent artemisinin, in Escherichia coli, PLoS One 4, e4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard E, Ajikumar PK, Thayer K, Xiao WH, Mo JD, Tidor B, Stephanopoulos G, and Prather KL (2010) Combining metabolic and protein engineering of a terpenoid biosynthetic pathway for overproduction and selectivity control, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 13654–13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang MCY, Eachus RA, Trieu W, Ro DK, and Keasling JD (2007) Engineering Escherichia coli for production of functionalized terpenoids using plant P450s, Nat Chem Biol 3, 274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao L, Chang WC, Xiao Y, Liu HW, and Liu P (2013) Methylerythritol phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis, Annu Rev Biochem 82, 497–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank A, and Groll M (2017) The methylerythritol phosphate pathway to isoprenoids, Chem Rev 117, 5675–5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudoh T, Park CS, Lefurgy ST, Sun M, Michels T, Leyh TS, and Silverman RB (2010) Mevalonate analogues as substrates of enzymes in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bioorg Med Chem 18, 1124–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalkreuter E, Carpenter SM, and Williams GJ (2018) Chapter 11 Precursor-directed Biosynthesis and Semi-synthesis of Natural Products, In Chemical and Biological Synthesis: Enabling Approaches for Understanding Biology, pp 275–312, The Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalkreuter E, and Williams GJ (2018) Engineering enzymatic assembly lines for the production of new antimicrobials, Curr Opin Microbiol 45, 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker MC, Thuronyi BW, Charkoudian LK, Lowry B, Khosla C, and Chang MC (2013) Expanding the fluorine chemistry of living systems using engineered polyketide synthase pathways, Science 341, 1089–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowell AN, DeMars MD, Slocum ST, Yu F, Anand K, Chemler JA, Korakavi N, Priessnitz JK, Park SR, Koch AA, Schultz PJ, and Sherman DH (2017) Chemoenzymatic total synthesis and structural diversification of tylactone-based macrolide antibiotics through late-stage polyketide assembly, tailoring, and C-H functionalization, J Am Chem Soc 139, 7913–7920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory MA, Petkovic H, Lill RE, Moss SJ, Wilkinson B, Gaisser S, Leadlay PF, and Sheridan RM (2005) Mutasynthesis of rapamycin analogues through the manipulation of a gene governing starter unit biosynthesis, Angew Chemie Int Ed 44, 4757–4760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moss SJ, Carletti I, Olano C, Sheridan RM, Ward M, Math V, Nur EAM, Brana AF, Zhang MQ, Leadlay PF, Mendez C, Salas JA, and Wilkinson B (2006) Biosynthesis of the angiogenesis inhibitor borrelidin: directed biosynthesis of novel analogues, Chem Commun (Camb), 2341–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen JR, Hutchinson CR, Cane DE, and Khosla C (1997) Precursor-directed biosynthesis of erythromycin analogs by an engineered polyketide synthase, Science 277, 367–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, and Li S (2017) Expansion of chemical space for natural products by uncommon P450 reactions, Nat Prod Rep 34, 1061–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruchattka E, Hadicke O, Klamt S, Schutz V, and Kayser O (2013) In silico profiling of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae as terpenoid factories, Microb Cell Fact 12, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori H, Baba T, Yokoyama K, Takeuchi R, Nomura W, Makishi K, Otsuka Y, Dose H, and Wanner BL (2015) Identification of essential genes and synthetic lethal gene combinations in Escherichia coli K-12, Methods Mol Biol 1279, 45–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palsuledesai CC, and Distefano MD (2015) Protein prenylation: enzymes, therapeutics, and biotechnology applications, ACS Chem Biol 10, 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeGraw AJ, Palsuledesai C, Ochocki JD, Dozier JK, Lenevich S, Rashidian M, and Distefano MD (2010) Evaluation of alkyne-modified isoprenoids as chemical reporters of protein prenylation, Chem Biol Drug Des 76, 460–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onono FO, Morgan MA, Spielmann HP, Andres DA, Subramanian T, Ganser A, and Reuter CW (2010) A tagging-via-substrate approach to detect the farnesylated proteome using two-dimensional electrophoresis coupled with Western blotting, Mol Cell Proteomics 9, 742–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham FX Jr., Lee H, and Gantt E (2007) Carotenoid biosynthesis in the primitive red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, Eukaryot Cell 6, 533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang HH, Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Sun ZZ, Xu G, Forest CR, and Church GM (2009) Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution, Nature 460, 894–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alper H, and Stephanopoulos G (2008) Uncovering the gene knockout landscape for improved lycopene production in E. coli, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 78, 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon SH, Lee YM, Kim JE, Lee SH, Lee JH, Kim JY, Jung KH, Shin YC, Keasling JD, and Kim SW (2006) Enhanced lycopene production in Escherichia coli engineered to synthesize isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate from mevalonate, Biotechnol Bioeng 94, 1025–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farmer WR, and Liao JC (2001) Precursor balancing for metabolic engineering of lycopene production in Escherichia coli, Biotechnol Prog 17, 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alper H, Miyaoku K, and Stephanopoulos G (2005) Construction of lycopene-overproducing E. coli strains by combining systematic and combinatorial gene knockout targets, Nat Biotechnol 23, 612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong CM, Meyers DJ, Imlay LS, Freel Meyers C, and Odom AR (2015) Resistance to the antimicrobial agent fosmidomycin and an FR900098 prodrug through mutations in the deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase gene (dxr), Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 5511–5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuzuyama T, Shimizu T, Takahashi S, and Seto H (1998) Fosmidomycin, a specific inhibitor of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase in the nonmevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis, Tettrahedron Lett 39, 7913–7916. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dellas N, Thomas ST, Manning G, and Noel JP (2013) Discovery of a metabolic alternative to the classical mevalonate pathway, eLife 2, e00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen M, and Poulter CD (2010) Characterization of thermophilic archaeal isopentenyl phosphate kinases, Biochemistry 49, 207–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Herk T, Hartog AF, Babich L, Schoemaker HE, and Wever R (2009) Improvement of an acid phosphatase/DHAP-dependent aldolase cascade reaction by using directed evolution, Chembiochem 10, 2230–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka N, Hasan Z, Hartog AF, van Herk T, Wever R, and Sanders RJ (2003) Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of polyhydroxy compounds by class A bacterial acid phosphatases, Org Biomol Chem 1, 2833–2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lis M, and Kuramitsu HK (2003) The stress-responsive dgk gene from Streptococcus mutans encodes a putative undecaprenol kinase activity, Infect Immun 71, 1938–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SW, and Keasling JD (2001) Metabolic engineering of the nonmevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis pathway in Escherichia coli enhances lycopene production, Biotechnol Bioeng 72, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unsold IA, and Li SM (2005) Overproduction, purification and characterization of FgaPT2, a dimethylallyltryptophan synthase from Aspergillus fumigatus, Microbiology 151, 1499–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King JR, Woolston BM, and Stephanopoulos G (2017) Designing a new entry point into isoprenoid metabolism by exploiting fructose-6-phosphate aldolase side reactivity of Escherichia coli, ACS Synth Biol 6, 1416–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang A, Meadows CW, Canu N, Keasling JD, and Lee TS (2017) High-throughput enzyme screening platform for the IPP-bypass mevalonate pathway for isopentenol production, Metab Eng 41, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirby J, Nishimoto M, Chow RW, Baidoo EE, Wang G, Martin J, Schackwitz W, Chan R, Fortman JL, and Keasling JD (2015) Enhancing terpene yield from sugars via novel routes to 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate, Appl Environ Microbiol 81, 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makde RD, Dikshit K, and Kumar V (2006) Protein engineering of class-A non-specific acid phosphatase (PhoN) of Salmonella typhimurium: modulation of the pH-activity profile, Biomol Eng 23, 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mihara Y, Utagawa T, Yamada H, and Asano Y (2000) Phosphorylation of nucleosides by the mutated acid phosphatase from Morganella morganii, Appl Environ Microbiol 66, 2811–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tasnadi G, Zechner M, Hall M, Baldenius K, Ditrich K, and Faber K (2017) Investigation of acid phosphatase variants for the synthesis of phosphate monoesters, Biotechnol Bioeng 114, 2187–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mabanglo MF, Schubert HL, Chen M, Hill CP, and Poulter CD (2010) X-ray structures of isopentenyl phosphate kinase, ACS Chem Biol 5, 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mabanglo MF, Pan JJ, Shakya B, and Poulter CD (2012) Mutagenesis of isopentenyl phosphate kinase to enhance geranyl phosphate kinase activity, ACS Chem Biol 7, 1241–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu HL, Liebhold M, Xie XL, and Li SM (2015) Tyrosine O-prenyltransferases TyrPT and SirD displaying similar behavior toward unnatural alkyl or benzyl diphosphate as their natural prenyl donor dimethylallyl diphosphate, Appl Microbiol Biot 99, 7115–7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liebhold M, Xie X, and Li SM (2012) Expansion of enzymatic Friedel-Crafts alkylation on indoles: acceptance of unnatural beta-unsaturated allyl diphospates by dimethylallyltryptophan synthases, Org Lett 14, 4882–4885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elshahawi SI, Cao HN, Shaaban KA, Ponomareva LV, Subramanian T, Farman ML, Spielmann HP, Phillips GN, Thorson JS, and Singh S (2017) Structure and specificity of a permissive bacterial C-prenyltransferase, Nat Chem Biol 13, 366-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen RD, Gao BQ, Liu X, Ruan FY, Zhang Y, Lou JZ, Feng KP, Wunsch C, Li SM, Dai JG, and Sun F (2017) Molecular insights into the enzyme promiscuity of an aromatic prenyltransferase, Nat Chem Biol 13, 226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.