Abstract

Developmental programs that generate the astonishing neuronal diversity of the nervous system are not completely understood and thus present a significant challenge for clinical applications of guided cell differentiation strategies. Using direct neuronal programming of embryonic stem cells, we found that two main vertebrate proneural factors, Ascl1 and Neurog2, induce different neuronal fates by binding to largely different sets of genomic sites. Their divergent binding patterns are not determined by the previous chromatin state but are distinguished by enrichment of specific E-box sequences which reflect the binding preferences of the DNA-binding domains. The divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding patterns result in distinct chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity profiles that differentially shape the binding of downstream transcription factors during neuronal differentiation. This study provides a mechanistic understanding of how transcription factors constrain terminal cell fates, and it delineates the importance of choosing the right proneural factor in neuronal reprogramming strategies.

Nervous systems are composed of a diverse array of neuronal cell types that form functional circuits. This cellular complexity is generated by the combinatorial activity of transcription factors (TFs). Decades of developmental biology studies identified a handful of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TFs called “proneural factors” that are necessary and sufficient to initiate neurogenesis1. In addition to conferring neuronal fate, proneural factors contribute to the specification of neuronal subtype identity2. While the molecular mechanisms by which different proneural factors control and coordinate neurogenesis and neuronal subtype specification have begun to be elucidated2, remaining gaps in our knowledge make it difficult to generate the vast array of clinically relevant neurons for research and clinical applications.

Ascl1 (Mash1) and Neurogenin2 (Neurog2), which are the mammalian homologs of Drosophila achaete-scute complex and atonal, respectively, are the two main proneural factors that initiate and regulate neurogenesis in vertebrate nervous systems1–4. Apart from a few regions in the nervous system where they are co-expressed, these two proneural factors are expressed in a complementary manner and are not interchangeable for neuronal subtype specification5–7. Proneural factors promote neurogenesis and induce distinct subtype identities, and these functions are conserved across phyla. In Drosophila ectoderm atonal controls chordotonal organ identity, while achaete-scute genes control external sensory organs8. In mice, Ascl1 and Neurog2 are respectively required to specify GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the forebrain and sympathetic and sensory neurons of the peripheral nervous system5,9–14. Thus, functional divergence of Ascl1 and Neurog2 is an ancestral trait responsible for the generation of neuronal diversity required in the nervous system which predates the split of vertebrates and invertebrates15.

The transcriptional programs that establish the terminal neuronal identity consists of generic (pan-neuronal) neuronal features, which are shared by all neurons, and subtype-specific features which are shared by specific classes of neurons1,16,17. These features are considered to be controlled by the activities of neurogenesis-inducing TFs (including proneural TFs) and TF combinations specific to a particular neuronal subtype18–20. While Ascl1 or Neurog2 can induce neurogenesis in neural-lineage or pluripotent cells21–23, reprogramming of differentiated cells usually couple Ascl1 and/or Neurog2 with additional TFs to promote subtype identity and/or downregulate the resident transcriptional program24–26. However, this model contrasts with the observation that Ascl- and Neurog- proneural families are the dominant force in controlling neuronal subtype identities when expressed in fibroblasts in combination with other TFs17. Thus, to better understand the rules that govern neuronal subtype reprogramming, we must understand the differences in Ascl1- and Neurog2-induced neurogenesis.

Direct programming is an advantageous platform to study how proneural TFs, alone or in combination with other TFs, control neuronal gene regulatory networks. Analysis of astrocyte-to-neuronal conversion by Ascl1 and Neurog2 shows that they initially activate largely non-overlapping genes27. Additionally, Ascl1 and Neurog2 were shown to act as “pioneer factors” in fibroblasts by binding to previously inaccessible regulatory regions and increasing chromatin accessibility upon binding25,28,29. However, it is not clear if Ascl1 and Neurog2 would have a similar non-overlapping differentiation trajectory when expressed in pluripotent stem cells as compared to differentiated cells and whether their proposed pioneering activity would differentially affect the acquisition of generic and subtype-specific neuronal features. To address these questions, the intrinsic differences between Ascl1 and Neurog2 and their effect on the downstream neurogenesis must be studied in a controlled environment that allows for a direct and robust comparison of the induced transcriptional and chromatin dynamics.

Here, we investigated the mechanism by which the two bHLH proneurals Ascl1 and Neurog2 engage with chromatin and affect the activities of TFs expressed downstream of Ascl1 and Neurog2 during neuronal differentiation. We found that Ascl1 and Neurog2 generate neurons by binding to largely different sets of genomic sites when expressed in similar chromatin and cellular contexts. Their divergent binding is due to distinct DNA sequence specificities of the respective bHLH domains towards preferred E-boxes. The initial divergent binding of Ascl1 and Neurog2 results in distinct regulatory landscapes that influence the binding pattern and the regulatory activity of shared downstream TFs in establishing shared (generic) and neuron-specific (subtype-specific) expression profiles. Thus, we speculate that the intrinsic differences in Ascl1- and Neurog2-induced neurogenesis increase the number of possible neuronal types generated during development by differentially altering the chromatin landscapes upon which the widely expressed downstream TFs operate.

Ascl1 and Neurog2 program neuronal fate with distinct neuronal subtype bias

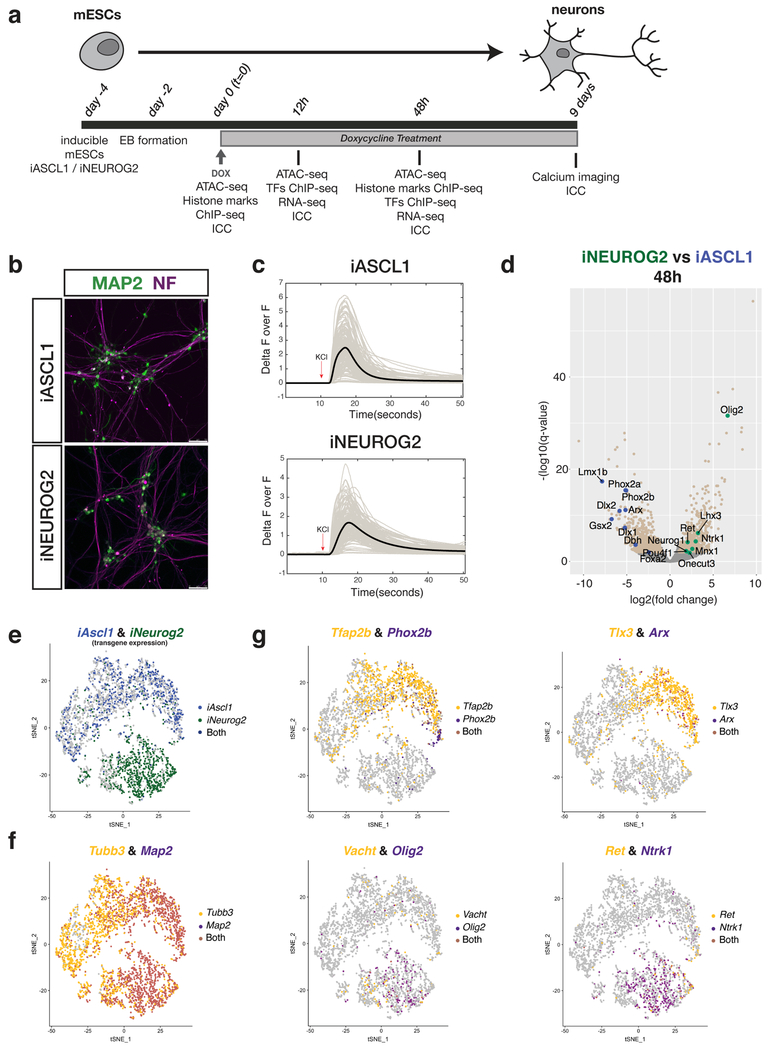

To investigate the intrinsic activities of Ascl1 and Neurog2, we generated two isogenic mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) lines that express either Ascl1 (iASCL1 or iA) or Neurog2 (iNEUROG2 or iN) upon Doxycycline (Dox) treatment but are otherwise identical (Fig. 1a). Induction of Ascl1 and Neurog2 resulted in neuronal differentiation with detectable upregulation of the neuron-specific ßIII-tubulin (Tubb3) within 12 hours after induction (Supplementary Fig. 1a). iA and iN neurons adopted typical neuronal morphologies with projections compatible with axonal and dendritic identity expressing NF and MAP2 proteins, respectively (Fig. 1b). Both iA and iN neurons responded to KCl-induced depolarization by changing their intracellular Ca++ concentration albeit with different dynamics – iN neurons have slower decay (Fig. 1c). In line with previous studies, forced expression of the proneural TFs Ascl1 or Neurog2 triggers a rapid conversion of differentiating mESCs into neurons21–23,30. Therefore, isogenic iA and iN lines constitute an ideal platform with which to comparatively study the molecular mechanisms of Ascl1- versus Neurog2-induced neurogenesis.

Fig. 1: Ascl1 and Neurog2 induction in differentiating mESCs generates neurons with distinct neuronal subtype bias.

a, Experimental scheme (EB: Embryoid body; ICC: Immunocytochemistry). b, iA and iN neurons express mature neuronal markers MAP2 (green) and Neurofilament (NF; purple) 9 days after Ascl1 and Neurog2 induction, respectively. Similar results were obtained n=2 independent cell differentiations. c, iA and iN neurons change their Ca++ levels upon KCl depolarization (9 days after induction). The thick line shows the average of individual recordings (from n=2 independent cell differentiations). d, Volcano plot comparing mRNA levels between iA and iN neurons by RNA-seq at 48 hours after induction (iA 48h n=5; iN 48h n=2). Beige dots represent the differentially expressed genes between iA or iN (q-value < 0.01, Wald test). Green and blue dots represent examples of differentially expressed genes in iN and iA, respectively. e, tSNE plot showing the single-cell clustering of the iA or iN neurons. Dots are colored by the expression of transgenes (iA cells – blue (top cluster), iN cells – green (bottom cluster) (n=1 cell differentiation). f, tSNE plot showing the cells that express generic neuronal markers Tubb3 and Map2. Note the maturation axis towards the left of the clusters (n=1 cell differentiation). g, tSNE plots showing iA and iN clusters expressing distinct neuronal subtype markers. The dots are colored by expression of Ascl1-specific genes Tfap2b&Phox2b (noradrenergic) and Tlx3&Arx (interneuron) (top panel), or Neurog2-specific genes Vacht&Olig2 (motor neuron) and Ret&Ntrk1 (sensory neuron) (bottom panel) (n=1 cell differentiation).

Ascl1 and Neurog2 overexpression transdifferentiates astrocytes into neurons by inducing an early divergent transcriptional profile27. To investigate if Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce neuronal differentiation with similar dynamics during mESC differentiation, we profiled mRNA levels at 12 and 48 hours after induction. 50% of Ascl1 upregulated genes and 37% of Neurog2 upregulated genes were shared at 12 hours (394 genes) (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The percentages of commonly upregulated genes increased to 74% and 80% at 48 hours, for iA and iN neurons respectively (2577 genes). Shared upregulated genes were enriched in GO-terms associated with generic neuronal features (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Moreover, Ascl1 and Neurog2 have already activated the expression of genes associated with different neuronal subtypes consistent with their requirement during embryonic development such as noradrenergic (Phox2b and Dbh in iA) and sensory neuron markers (Ret and Ntrk1 in iN) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1d).

To investigate if the gene expression differences stem from a subset of neurons in the dish, or the majority of iA and iN neurons differ, we performed a single-cell RNA-seq (sc-RNAseq) experiment at 48 hours after induction. The vast majority of cells upregulated generic neuronal markers Tubb3 and Map2 (Fig. 1f). Confirming the hypothesis that Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce neurogenesis through divergent differentiation paths, iA and iN neurons clustered into two distinct groups based on transgene expression (Fig. 1e). The neuronal subtype markers were not homogeneously distributed across either population nor largely co-expressed in the same cells (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 1d). For example, noradrenergic (Tfap2b & Phox2b) and cortical interneuron (Tlx3 & Arx) markers were primarily expressed by iA neurons, spinal motor (Vacht & Olig2) and sensory neuron (Ret & Ntrk1) markers were expressed by iN neurons (Fig. 1g). Thus, while these results are not indicative of complete neuronal subtype specification, Ascl1 and Neurog2 expression initiates different neuronal differentiation programs even when expressed under similar chromatin and transcriptional states.

Ascl1 and Neurog2 bind to largely distinct sets of sites in the genome

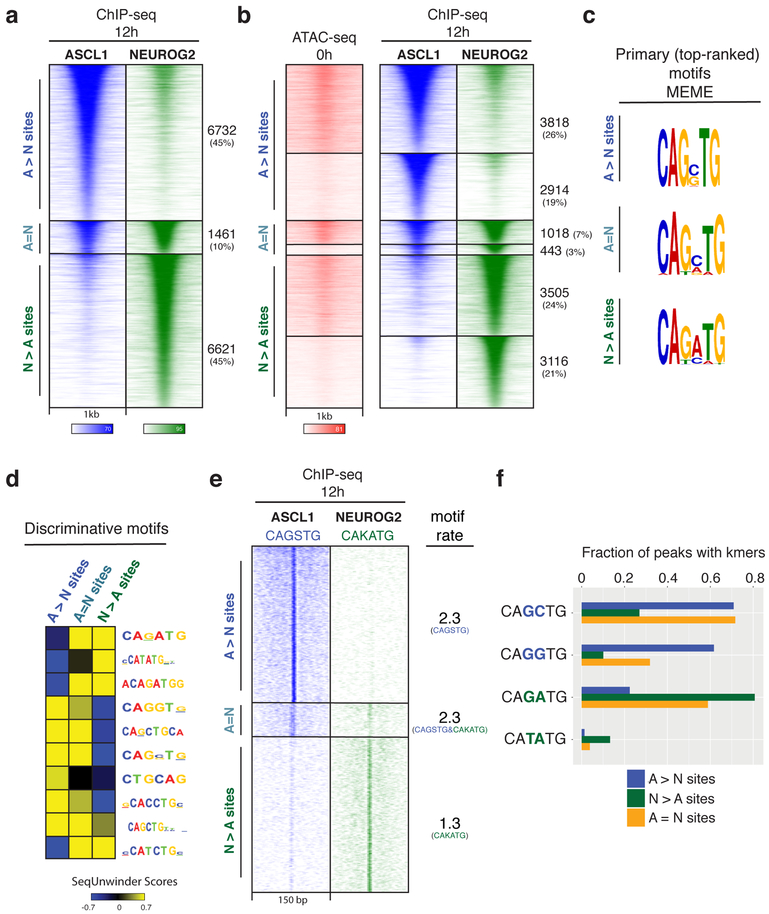

To understand how Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce neuronal differentiation, we captured their initial binding at 12 hours after induction – which is the earliest time point when the Dox system induces robust expression of these TFs in most cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We identified 20,452 and 28,206 binding sites for Ascl1 and Neurog2, respectively. While analysis of the whole data produces similar percentages (Supplementary Fig. 2a), we focused on the top 10,000 binding sites in each dataset for downstream analysis to eliminate complications that may arise from comparing ChIP-seq signals with different strengths. The initial binding of Ascl1 and Neurog2 was largely non-overlapping, with 90% of all sites confidently called as differentially bound – Ascl1 and Neurog2 each preferentially bind 45% of the sites (Fig. 2a). Only 10% of the sites were bound with similar strength by both TFs. We designated Ascl1 and Neurog2 differentially bound sites respectively as “Ascl1-preferred sites (A>N sites)”, “Neurog2-preferred sites (N>A sites)”, and the sites that were bound by both TFs as “shared sites (A=N sites)”. Ascl1 pioneer activity is not enough to allow for its invariable binding across cell types because Ascl1 binding in mESCs does not recapitulate its genomic distribution when expressed in fibroblasts25 (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Our data recovers some of the few sites previously described as bound by Ascl1 in mESCs, but this comparison is compromised by the radically different ChIP strength31 (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Thus, as in line with Dll1 activation by distinct Ascl1 and Neurog2 enhancers (Supplementary Fig. 2f), genome-wide comparison of the two proneural bHLH TFs Ascl1 and Neurog2 shows remarkably different binding profiles under similar chromatin and cellular contexts.

Fig. 2: Genome-wide characterization of Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding and its determinants.

a, ChIP-seq heatmap showing Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding at 12 hours after induction. Ascl1- and Neurog2-preferred sites are designated as “A>N” and “N>A”, respectively. Sites that are bound by both Ascl1 and Neurog2 are designated as shared sites (A=N). Top 10k sites are plotted on the heatmap within a 1kb window around the peak center (n=3). b, Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding does not depend on prior chromatin accessibility. Ascl1 and Neurog2 ChIP-seq heatmap partitioned into previously accessible and inaccessible sites per 0h ATAC-seq signal at bound sites. c, Primary (top-ranked) motifs enriched at the differentially bound A>N, N>A, and shared (A=N) sites differ in central nucleotides. d, The discriminative motifs enriched at the A>N, A=N, N>A sites corroborate the relative enrichment of the distinct E-box variants. e, CAGSTG and CAKATG k-mer occurrences plotted at Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding sites within a 150 bp window (S: G/C; K: G/T). The rate of motif/k-mer occurrence at the binding sites are shown on the right. f, Ascl1 and Neurog2 differentially bound sites are distinguished by specific E-box instances. Fraction of differentially bound and shared sites containing various k-mer sequences within a 150 bp window around the peak center.

Distinct E-box sequences are enriched at Ascl1- and Neurog2-preferred sites

The extensive lack of overlap between Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding prompted us to investigate the possible mechanisms driving their divergent binding patterns. Chromatin accessibility and DNA sequence are the two main factors that dictate in vivo TF binding to regulatory elements32. Ascl1 acts as a pioneer factor, however pioneering activity for Neurog2 was only proposed indirectly when in combination with small molecules that enhance chromatin accessibility25,28. When we compared 12 hours Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding to the previous chromatin accessibility state by ATAC-seq, we observed that both TFs engage with previously accessible and inaccessible sites in roughly the same proportion: 57% and 43% of A>N sites were previously accessible and inaccessible, respectively (Fig. 2b). Likewise, 53% and 47% of N>A sites were previously accessible and inaccessible, respectively (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding patterns are not due to major differences in their intrinsic abilities to bind inaccessible chromatin.

It has been observed that Drosophila orthologs Scute and Atonal have different E-box targets and Ascl1 and Neurog2 regulate Dll1 expression by binding to distinct E-box sequences33,34. Thus, we investigated whether DNA sequence features could explain the differences in the binding of Ascl1 and Neurog2. The primary (top-ranked) motifs discovered by MEME in each class of Ascl1- and Neurog2-bound sites were variations of canonical E-boxes, differing primarily in the central two nucleotides (Fig. 2c). The primary motif discovered at A>N sites contained the consensus sequence “CAGSTG” (S: G/C nucleotides), encompassing the canonical E-box motif “CAGCTG” which had been associated with the Ascl1 binding in fibroblasts and neural stem cells25,30. On the other hand, the primary motif at N>A sites contained the consensus “CAKMTG” (K: G/T nucleotides, M: A/C nucleotides). The peaks bound by both TFs (A=N) contained a motif that appears to be the average between the motifs found in the other two classes (Fig. 2c). To further identify discriminative motifs between Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding classes, we deployed SeqUnwinder – a tool designed to search for discriminative motifs across ChIP-seq samples. SeqUnwinder identified variations of the canonical E-box motif (CANNTG) that discriminate between A>N, N>A, and A=N shared sites (Fig. 2d). CAGSTG and CAKATG motifs were visibly enriched at the A>N and N>A when plotted in 150 bp window around peaks (Fig. 2e). The CAGSTG motif occurred more than once at the A>N sites, while the CAKATG motif occurred on average once (Fig. 2e). Specifically, “CAGCTG” and “CAGGTG” 6-mers were present at 70% and 62% of the A>N sites with some sites having both 6-mers, as opposed to only 27% and 10% of N>A sites (Fig. 2f). On the other hand, 81% of the N>A sites contained the “CAGATG” 6-mer sequence, while this 6-mer was present at only 22% of the A>N sites. Of note, only 13% of the N>A sites contained the “CATATG” motif described for in vitro Neurog2 binding35. Finally, roughly half of the A=N sites contained both Ascl1- and Neurog2-preferred 6-mers, suggesting that Ascl1 and Neurog2 bind to different E-boxes even within shared enhancers (Fig 2f). Sequences flanking E-boxes have been shown to confer additional specificity to bHLH TFs by affecting the DNA shape36,37. Indeed, there were differences in nucleotide preferences flanking the non-discriminative core E-box (CAGNTG) and A>N sites were associated with larger predicted propeller twist and larger predicted minor groove width at alternate sides of the core E-box motif (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Thus, Ascl1 and Neurog2 have strong DNA sequence preferences that drive their genomic binding in differentiating mESCs.

bHLH domain controls DNA sequence-specificity and neuronal subtype identity

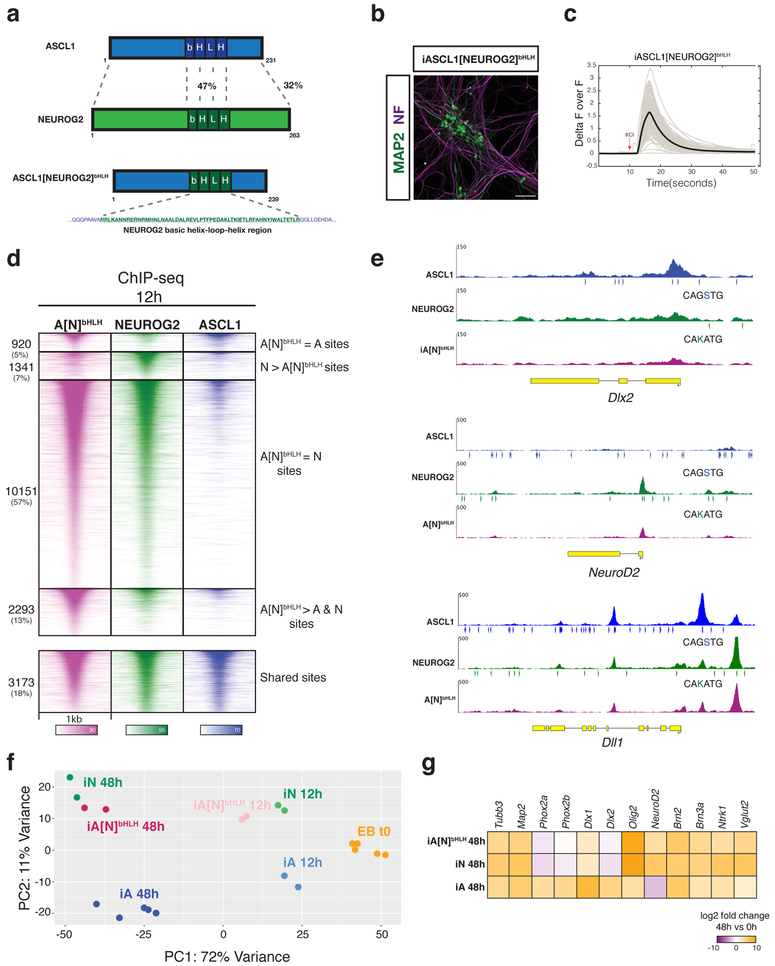

The basic domain of proneural TFs binds to the major groove of DNA, while the helix-loop-helix (HLH) domain mediates heterodimerization with other HLH proteins38,39. To test whether the bHLH (DNA-binding and dimerization) domain is sufficient to induce the divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding patterns, we generated an inducible mESC line expressing a chimeric Ascl1-Neurog2 TF (A[N]bHLH chimera) by swapping the bHLH domain of Ascl1 with that of Neurog2 (Fig. 3a). Like Ascl1 and Neurog2, A[N]bHLH chimera generated neurons that respond to KCl-induced depolarization and express mature neuronal cytoskeleton markers (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3: bHLH domain of Neurog2 is sufficient to drive both the genomic binding and transcriptional output.

a, Schematic of generation of the bHLH chimera by swapping the bHLH domain of Ascl1 with that of Neurog2. The percentages represent the amino acid sequence similarity between the bHLH domains (47%) and the overall protein (32%). The A[N]bHLH chimeric TF construct was used to generate a stable inducible iA[N]bHLH line. b, Expression of A[N]bHLH chimeric TF generates neurons that express mature neuronal markers MAP2 (green) and NF (purple) 9 days after induction. Similar results were observed in two independent cell differentiations. c, iA[N]bHLH neurons respond to KCl-induced depolarization by changing their intracellular Ca++ levels. Thick line represents the average across recordings (from n=2 independent cell differentiations). d, The A[N]bHLH chimera binds largely to Neurog2 sites in the genome. ChIP-seq heatmap showing the binding sites of A[N]bHLH chimera in comparison to Neurog2 and Ascl1. e, Genome browser snapshots of Ascl1, Neurog2, and A[N]bHLH chimera binding sites (12h ChIP-seq) with distribution of Ascl1- or Neurog2-preferred E-boxes (arrowheads) on subtype-specific genes (Dlx2 and NeuroD2) and a shared target Dll1 (S: G/C; K: G/T) (A[N]bHLH n=2). f, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the RNA-seq replicates shows A[N]bHLH chimera-induced neurons (iA[N]bHLH) cluster with Neurog2-induced neurons (iN) both at 12h and 48h (each dot represents independent cell differentiations). g, RNA-seq heatmap showing the expression of representative subtype-specific genes in iA, iN, and iA[N] neurons at 48h.

A[N]bHLH chimera binding had significantly different ChIP-seq enrichment compared to Ascl1 at 70% of the sites (A[N]bHLH=N sites and A[N]bHLH>A&N sites) (Fig. 3d). On the other hand, only 18% of A[N]bHLH chimera binding sites were significantly different from those of Neurog2 (A[N]bHLH>A&N and A[N]bHLH=A sites). As expected from its binding pattern, the k-mer (6-mers and 8-mers) signatures at the A[N]bHLH chimera binding sites were similar to that of Neurog2 sites as well (Supplementary Fig. 4a). For example, ChIP-seq signal and the k-mer signature of the chimera at the shared (Dll1) and neuron-specific genes, such as NeuroD2 (target of Neurog2) and Dlx2 (target of Ascl1), also resembled that of Neurog2 (Fig. 3e). Thus, the analysis of the A[N]bHLH chimeric TF demonstrates that the differences in Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding patterns are intrinsic and determined by the amino acid sequence of the bHLH domain.

Although the A[N]bHLH chimera binds to Neurog2-preferred sites driven by its Neurog2 bHLH domain, the rest of its amino acid sequence is identical to Ascl1 (Fig. 3a). Specific residues outside the bHLH domain of Ascl1 and Neurog2 were shown to behave as rheostat-like modulators upon phosphorylation/dephosphorylation for the context-dependent activity of their proneural functions2,40–44. However, the A[N]bHLH chimera induces a gene expression profile similar to that induced by Neurog2 (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). Principal component analysis (PCA) on gene expression (RNA-seq) of the A[N]bHLH-, Ascl1-, and Neurog2-induced neurons (iA[N]bHLH, iA, iN neurons) revealed that A[N]bHLH differentiation trajectory is similar to that induced by Neurog2 (Fig. 3f). The first two PCA dimensions of individual replicates explain 83% of the variance, with PC1 reflecting differentiation time and PC2 reflecting the differences in iA and iN neurons. These results demonstrate that the bHLH domain of Neurog2 is both sufficient to drive sequence-specific DNA binding on chromatin, and strongly induces subtype-specific gene expression profiles in differentiating mESCs. Thus, the divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding pattern is the main determinant of the bias in the expression of neuronal subtype genes.

Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding results in differential chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity

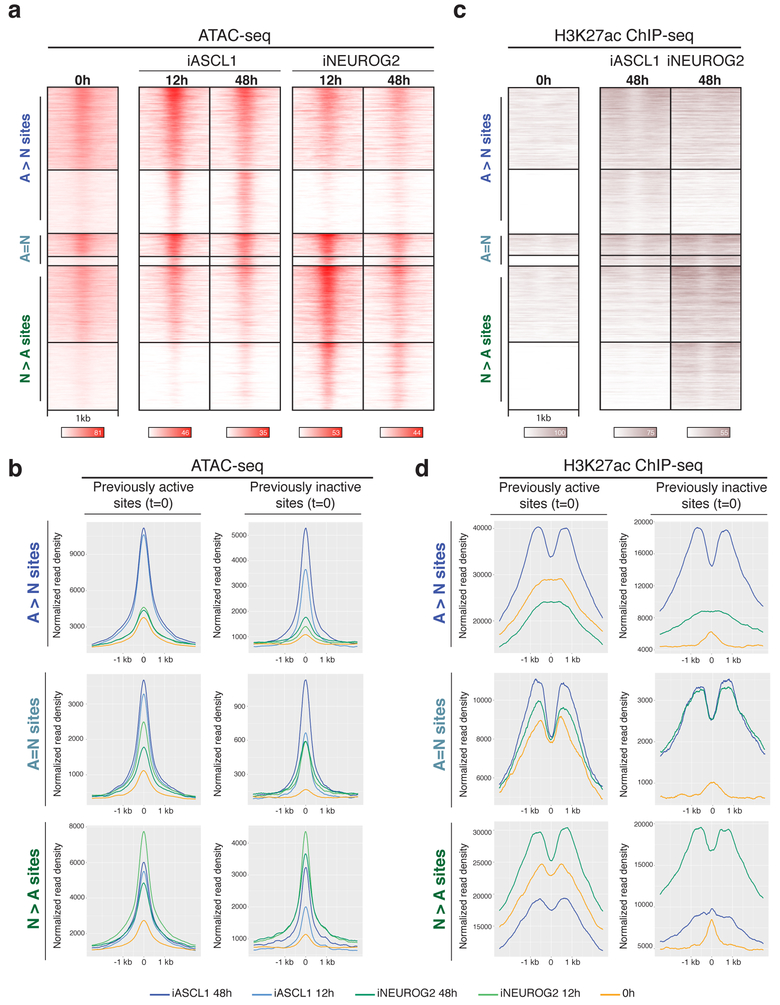

The strong binding preference and the likely importance of the binding pattern in controlling the differentiation trajectory of neurons prompted us to investigate the chromatin landscapes that result from the divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding. We examined genome-wide chromatin accessibility dynamics by ATAC-seq before and after the induction of the proneural TFs. A global accessibility analysis revealed that Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce different accessibility landscapes (Supplementary fig. 5a). Mirroring the expression dynamics (Supplementary fig. 1b), the majority of initial accessibility changes are specific to iA or iN neurons (Supplementary fig. 5a). As differentiation proceeds and the downstream program converges, a larger set of common loci gain accessibility (Supplementary fig. 5a). We also compared the accessibility landscape in Ascl1-induced neurons from stem cells and fibroblast45 (Supplementary fig. 5b). Following the Ascl1 binding differences, the accessibility landscape between these two neuronal differentiations is quite dissimilar.

Because of the divergent binding pattern and the resulting accessibility differences upon proneural TF induction, we sought to investigate if Ascl1- and Neurog2-preferred sites gain accessibility during differentiation. Proneural sites gained ATAC-seq signal after Ascl1 or Neurog2 binding, regardless of their accessibility state before TF induction (Fig. 4a). While Ascl1-preferred sites progressively gained accessibility, Neurog2-preferred sites quickly gained accessibility and remained accessible but lost some ATAC-seq signal at 48 hours (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, A[N]bHLH chimera binding also resulted in a rapid gain of accessibility by 12 hours with a pattern similar to that of Neurog2 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). These results demonstrate that, albeit with different dynamics, both bHLH factors induce or maintain regulatory regions in an accessible state. Similarly, independent of the histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) status before TF induction, Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding resulted in an increase of H3K27ac at bound sites by 48 hours (Fig. 4c, d). Although we observe a gain of accessibility at the previously inaccessible N>A sites in iA neurons by 48 hours, these sites do not gain H3K27ac enrichment (Fig. 4b, d). In summary, both Ascl1 and Neurog2 bind to active or inactive regulatory elements, and their binding subsequently increases chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity of bound regulatory regions. Thus, the divergent binding of Ascl1 and Neurog2 results in different chromatin accessibility and activity landscapes during Ascl1- or Neurog2-induced neurogenesis.

Fig. 4: Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding results in differential chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity.

a, Time-series ATAC-seq heatmaps displaying the gain of accessibility at the Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding sites (n=2). b, Metagene plots of accessibility (ATAC-seq reads) at the differentially bound and shared sites of Ascl1 and Neurog2 that were previously active (left) or previously inactive (right) before induction of the TFs (0h or EB t=0). c, H3K27ac ChIP-seq at Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding sites at 48h shows the gain of enhancer activity at the bound sites in comparison to 0h (n=2). d, Metagene plots of H3K27ac ChIP-seq at the differentially bound and shared sites of Ascl1 and Neurog2 that were previously active (left) or previously inactive (right) before the induction of the TFs (0h or EB t=0).

Distinct chromatin landscapes induced by Ascl1 and Neurog2 affect the binding of the downstream TFs

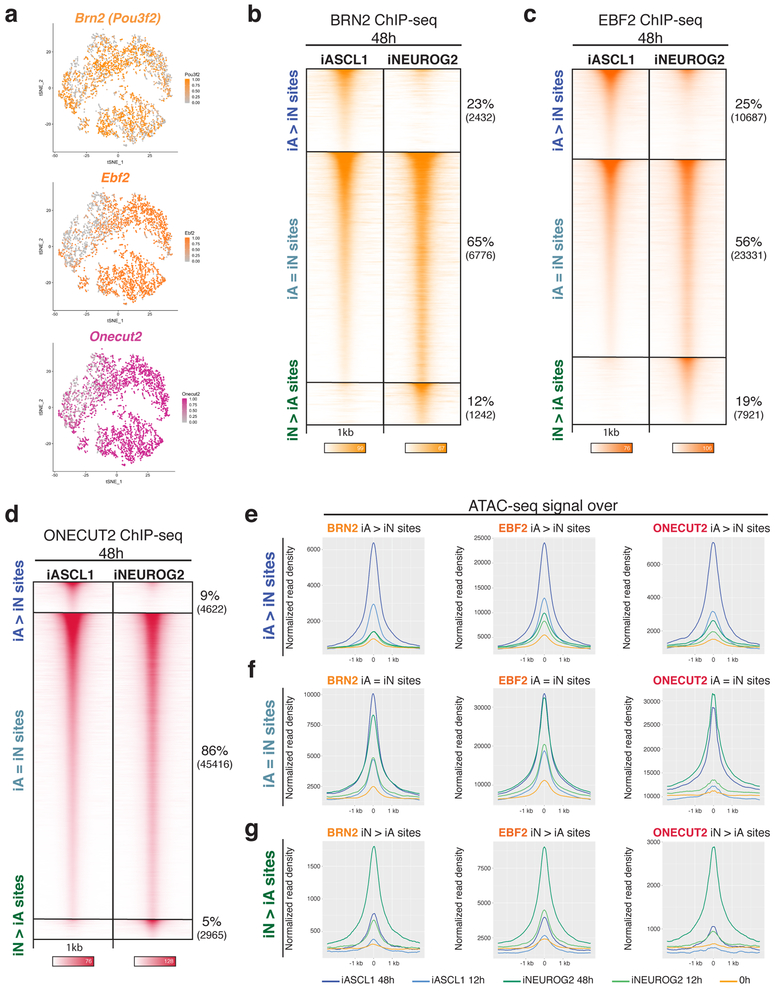

We hypothesized that the regulatory activity of the TFs expressed downstream of both proneurals will be conditioned by the distinct chromatin landscapes induced by Ascl1 and Neurog2. Brn2 (POU & Homeodomain TF), Ebf2 (non-basic HLH & Zinc finger TF), and Onecut2 (CUT & Homeodomain TF) are among the widely expressed neuronal TFs in the nervous system which are induced by both Ascl1 and Neurog2 in differentiating mESCs by 48 hours (Fig. 5a). Thus, we analyzed Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 genome-wide binding in iA and iN neurons 48 hours after induction of the proneural TFs. Around 60% of the Brn2 and Ebf2 binding sites were shared in iA and iN neurons (iA=iN sites), while roughly 40% of Brn2 and Ebf2 sites were differentially enriched in iA or iN neurons (iA>iN and iN>iA sites) (Fig. 5b, c). Binding of Brn2 in ESC differentiation is dissimilar to Brn2 in fibroblasts when expressed alongside Ascl1 and Myt1l (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Among these TFs, Onecut2 had proportionally less differentially bound sites in iA and iN neurons (14%), while the majority of sites bound by Onecut2 were shared in iA and iN neurons (86%) (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5: Differential chromatin landscapes induced by Ascl1 and Neurog2 shape the binding patterns of the shared downstream TFs.

a, tSNE plots showing the cells that express downstream TFs (Top cluster iA, below cluster iN – Fig. 1e). The dots are colored by the expression levels of downstream TF Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 (n=1 cell differentiation). b-d, ChIP-seq heatmaps of endogenous Brn2 (A), Ebf2 (B), and Onecut2 (C) binding in iA and iN neurons at 48h after induction of Ascl1 and Neurog2. “iA>iN” designates sites enriched in iA neurons, “iN>iA” designates sites enriched in iN neurons, and “iA=iN” designates shared binding in both neurons (n=2). e, Metagene plots of accessibility (ATAC-seq reads) overlap at the differentially bound sites of Brn2 (left), Ebf2 (middle), and Onecut2 (right) in iA neurons (iA>iN sites).f, Metagene plots of accessibility (ATAC-seq reads) overlap at the shared sites of Brn2 (left), Ebf2 (middle), and Onecut2 (right) in iA and iN neurons (iA=iN sites). g, Metagene plots of accessibility (ATAC-seq reads) overlap at the differentially bound sites of Brn2 (left), Ebf2 (middle), and Onecut2 (right) in iN neurons (iN>iA sites).

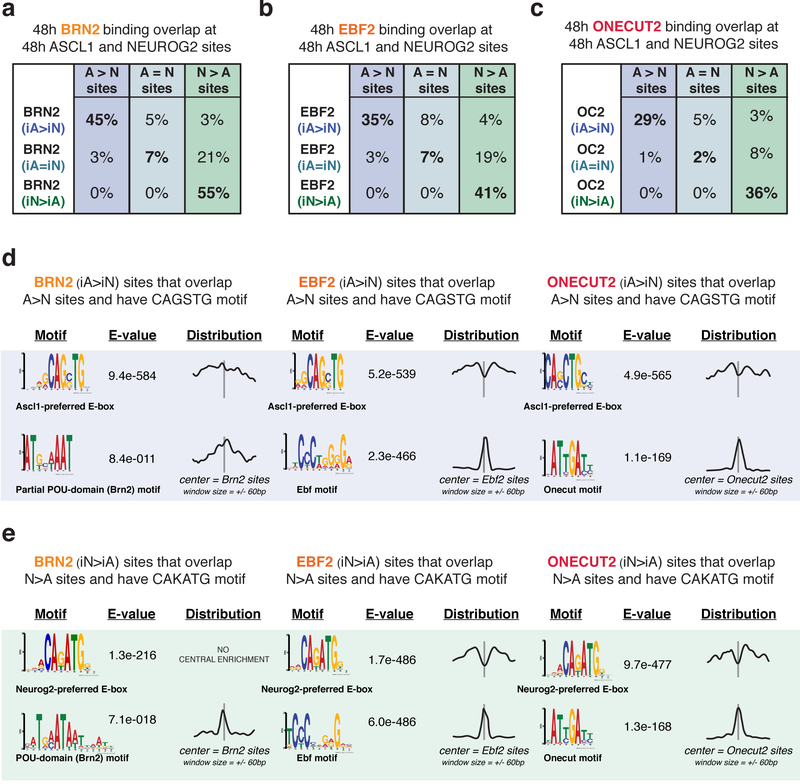

If the Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 binding differences are shaped by Ascl1- and Neurog2-induced chromatin landscapes, then their differential binding should correlate with the differentially accessible regions established in iA and iN neurons. Indeed, Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 sites differentially enriched in iA neurons (iA>iN) occurred in sites that became differentially accessible in iA neurons (Fig. 5e). Similarly, differentially bound sites in iN neurons (iN>iA) also occurred in sites that became accessible in iN neurons (Fig. 5g). On the other hand, Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 shared binding sites in iA and iN neurons (iA=iN) have high ATAC-seq read counts in both iA and iN neurons, thus were accessible in both neurons (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 differential binding sites in iA neurons (iA>iN) substantially overlap with Ascl1-preferred binding (A>N sites) (45%, 35%, 29%, respectively, and only <1% of expected overlap by chance) at 48 hours (Fig. 6a, b, c). Two observations suggest that the differentially bound sites represent direct DNA-binding targets of the downstream TFs. First, motif-finding analysis at the differentially bound Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 sites that harbor an E-box motif revealed Ascl1- vs Neurog2-preferred E-boxes along with appropriate cognate motifs for downstream TFs (Fig. 6d, e). Second, while the downstream TF cognate motifs are enriched at the center of the ChIP-seq peaks, the E-box is depleted at the central peak location (Fig 6d, e). However, we note that the downstream TF cognate motif instances are weaker at differentially bound sites compared with other downstream TF binding sites in iA and iN (Supplementary fig. 6b). These results support a model in which the differential chromatin accessibility induced by Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding exposes weaker cognate motifs that can then be bound by downstream TFs. Consequently, the activity of widely expressed TFs is not functionally equivalent in all neurons.

Fig. 6: Differentially bound sites of downstream TFs in iA or iN neurons overlap with Ascl1 or Neurog2 binding.

a-c, A subset of differentially enriched Brn2 (a), Ebf2 (b), Onecut2 (c) binding sites in iA or iN neurons at 48h overlap with Ascl1 or Neurog2 differential binding at 48h. d, MEME motif search at the 48h differentially bound Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 sites in iASCL1 neurons (iA>iN) that overlap with differentially bound Ascl1 sites (A>N) with CAGSTG motif. Note that the cognate motif of downstream TFs is present and Ascl1-preferred E-boxes are depleted in the motif distribution graphs centered on downstream TF motifs. The E-values are reported by MEME, and represent an estimate of the expected number of motifs with the same log likelihood ratio that one would find in a similarly sized set of random sequences. e. MEME motif search at the 48h differentially bound Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 sites in iNEUROG2 neurons (iN>iA) that overlap with differentially bound Neurog2 sites (N>A) with CAKATG motif.

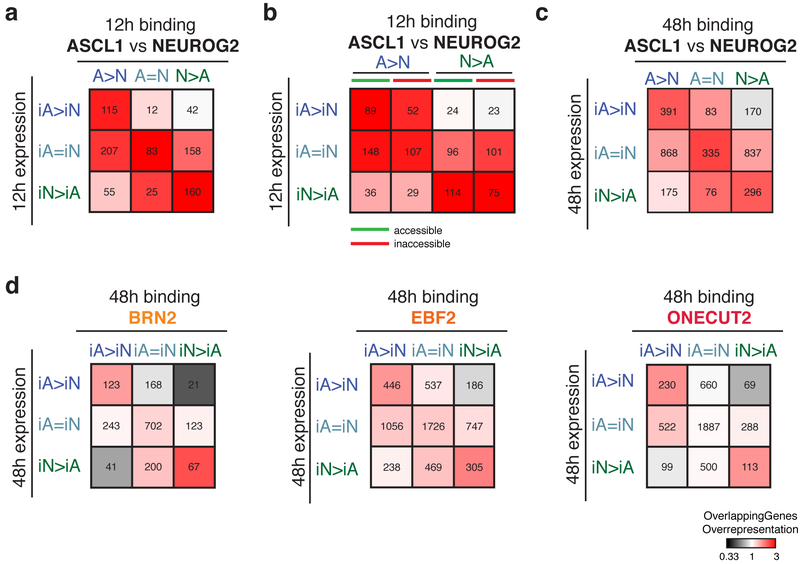

Ascl1 and Neurog2 control initial transcriptional changes and bias the regulatory activity of downstream TFs in the acquisition of neuron-specific identity

To understand how Ascl1 and Neurog2 non-overlapping binding induces expression of subtype-specific (neuron-specific) and generic (shared) neuronal genes, we explored the association between binding sites of Ascl1, Neurog2, and downstream TFs with induced gene expression using GREAT. We first investigated the association between differential binding and gene expression at 12 hours. This analysis revealed that early (12 hours) differential binding of Ascl1 or Neurog2 correlates well with early differentially expressed genes at 12 hours (Fig 7a). Around 65% and 78% of the Ascl1 or Neurog2 differentially expressed genes at 12 hours have at least one A>N or N>A peak within GREAT-defined regulatory domains, respectively (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 1). Dividing proneural TF binding into previously accessible and inaccessible regions does not dramatically modify the association with transcription (Fig. 7b). Thus, the initial divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding correlates with differential gene expression regardless of the previous accessibility state.

Fig. 7: Associations between genomic binding sites and gene expression.

a, Heatmap representing the associations (ratio between the genes overlapped by Ascl1 or Neurog2 peaks versus random peaks: overlapping genes overrepresentation) between 12h Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding with 12h gene expression. b, Heatmap representing the associations between 12h Ascl1 and Neurog2 sites that were previously accessible (green) or inaccessible (red) with 12h gene expression. c, Heatmap representing the associations between 48h Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding with 48h gene expression. d, Heatmap representing the associations between 48h Brn2 (top), Ebf2 (middle), Onecut2 (bottom) binding in iA and iN neurons with 48h gene expression in iA and iN neurons. For all panels: the number of genes that overlap with specific binding classes are listed inside the squares.

The next challenge was to understand how the 10% overlap in Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding results in ~80% overlap in gene expression by 48 hours after induction. Sites that are bound by Ascl1 and Neurog2 (A=N sites) associate with genes upregulated in both neurons (Fig.7a–c). Additionally, differentially bound Ascl1 and Neurog2 sites (A>N and N>A) are also associated with genes upregulated in both neurons (Fig. 7a–c). Expanding on Dll1 regulation by differential Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding34, our results suggest that distinct Ascl1 and Neurog2 regulatory elements are spatially peppered around similar sets of genes, and Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce shared and neuron-specific (subtype-specific) gene expression through different regulatory regions (Supplementary fig. 6c).

Ascl1 and Neurog2 drive the majority of the expression differences at early time points. We tested if the downstream factors contribute to gene expression differences. Shared binding sites of Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 in iA and iN neurons are associated with shared upregulated genes in iA and iN neurons at 48 hours (Fig. 7d). Similarly, differentially bound Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 sites significantly associate with Ascl1- or Neurog2-specific gene expression at 48 hours (Fig. 7d). These results suggest that the initial divergent binding of the proneural TFs biases both binding (Fig. 6) and activity of shared downstream TFs thus contribute to neuron-specific expression profiles.

Discussion

Here, we probed the molecular mechanisms governing the divergent roles played by the proneural factors Ascl1 and Neurog2 during neuronal differentiation. Using direct neuronal programming of isogenic mESCs, we found that the proneural factors influence cell fate in two ways. First, Ascl1 and Neurog2 bind to and regulate distinct sets of regions in the genome, determined by the intrinsic activity of their bHLH domains. Second, because of this initial divergent binding, Ascl1 and Neurog2 induce differential chromatin landscapes that shape the binding and function of the shared downstream TFs during neuronal fate specification. Hence, we speculate that the regulatory activity of the widely expressed shared TFs will not be identical when expressed downstream of Ascl1 or Neurog2 during neurogenesis and reprogramming experiments.

The question of bHLH TF binding specificity is of importance not only for proneural factors but also for bHLH TFs that regulate various developmental events such as myogenesis, hematopoiesis, and pancreatic development38. While extensive binding differences are intuitive for TFs that belong to different bHLH families and induce different cell types such as MyoD versus Ascl1 or NeuroD231,46, it was striking to observe the substantial difference in the genomic binding of proneural bHLHs Ascl1 and Neurog2 even when expressed in similar chromatin contexts. bHLH dimers acquire specificity by recognizing distinct E-box half sites (CAN-NTG) in DNA47. Thus, the non-palindromic Ascl1- and Neurog2-preferred E-boxes (“CAGGTG” and “CAGATG”, respectively) enriched at the differentially bound sites could reflect the sites that are bound with their heterodimerization partners.

Several experiments suggest the importance of the bHLH domain for the subtype-specific activity of neural bHLHs46,48–50. Using an equivalent chromatin and cellular context for comprehensive analysis of Ascl1-, Neurog2-, and Ascl1[Neurog2]bHLH-induced neurogenesis led us to an interesting observation: the genomic binding, transcriptional output, and even the chromatin accessibility dynamics induced by the Ascl1[Neurog2]bHLH chimera was similar to that induced by Neurog2. The DNA specificity of the bHLH domain can be further divided by amino acids in mostly the basic domain and helix 1 contacting DNA and helix 2 mediating dimerization39. Additional experiments are required to resolve if, in this differentiation system, DNA binding preferences of the amino acids in the basic and helix1 region or the dimerization surface guides Ascl1 and Neurog2 to different sites. Phosphorylation of certain residues outside bHLH domain has been shown to alter the proneural activity42 and the interactions with putative partners of Ascl1 and Neurog2 homologs in Xenopus and in mouse40,41,43,44. Although the controlled mESC differentiation system is ideal for studying the intrinsic differences between the proneural TFs, it might lack the complexity of the extracellular signaling in developing embryos. Alternatively, posttranslational modifications can fine-tune the binding preferences which might have been overshadowed by high expression levels required to differentiate mESCs into neurons.

Divergent Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding induce initially divergent accessibility and expression pattern that later converge on a generic neuronal fate while maintaining subtype-specific differences (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c, d and Fig. 1d, g). We found that shared binding of the proneural TFs and the downstream TFs correlates with upregulation of a generic neuronal program. This divergent-to-convergent neuronal differentiation trajectory is in line with the previous studies which described NeuroD4 among the common targets regulating the shared genes during astrocyte-to-neuron programming by Ascl1 or Neurog227. The complete cascade of events that leads to this convergence while maintaining some expression differences in astrocyte and pluripotent cell differentiations are yet to be uncovered. Brn2 was proposed to be recruited to its genome-wide sites by Ascl1 in neuronal reprogramming of fibroblasts25. We report here that both Ascl1 and Neurog2 influence the binding pattern of several downstream TFs. Our findings propose a novel mechanism that links these previous findings: the widely expressed shared TFs contribute not only to generic neuronal program, but also to neuron-specific programs by retaining the memory of the initial neurogenesis triggered by divergent binding of Ascl1 and Neurog2 (Supplementary fig. 7). Thus, in addition to the differentially expressed TFs and/or terminal selectors, the role of widely expressed TFs should also be considered in determining the aspects of neuronal subtype identity.

The ability of Ascl1 and Neurog2 to substitute for each other varies in different regions of the nervous system5. We propose that the intrinsic Ascl1 and Neurog2 differences will have a smaller impact on instructing the neuronal subtype identity in neuronal progenitors where the chromatin is strongly pre-patterned for a specific neuronal type. However, when expressed in a permissive chromatin and cellular state, Ascl1 and Neurog2 differentially force the specification of distinct neuronal subtype identities. These findings provide a mechanistic explanation for the importance of choosing the right proneural factor in neuronal differentiation strategies.

Methods

Experimental Procedures

Cell line generation and cell differentiation

Inducible cell lines were generated using the inducible cassette exchange (ICE) method that was previously described51. Resulting transgenic lines contain a single-copy insertion of the transgene into an expression-competent (HPRT) locus. p2Lox-Neurog2 (iNeurog2) plasmid was generated by cloning Neurog2 cDNA into p2Lox-Flag plasmid52. Likewise, p2Lox-Ascl1(iAscl1) plasmid was generated by cloning mouse Ascl1 cDNA into p2Lox-V5 plasmid53. To generate p2Lox-iAscl1[Neurog2]bHLH chimera, 396 bp of oligonucleotide gBlocks (IDT) fragment encompassing Neurog2 bHLH domain fused to C-terminal of Ascl1 with 1X HA tag sequence was synthesized. Ascl1 N-terminal fragment was amplified from mouse Ascl1 cDNA. In-fusion cloning (Clontech) was used to clone/fuse Ascl1 N-terminal and gBlocks Neurog2 bHLH-Ascl1 C-terminal-HA in a p2Lox plasmid backbone. The inducible cell lines (iA, iN, iA[N]bHLH) were generated by treating the recipient mESCs for 16hr with 1 ug/ml Doxycycline (Sigma D9891) to induce Cre recombinase expression to mediate recombination following electroporation of the p2Lox-Ascl1, p2Lox-Neurog2 p2Lox-iAscl1[Neurog2]bHLH plasmids. After G418 selection (250ng/ml, Cellgro), cell lines were characterized by performing antibody staining against the tagged transgenic proteins Ascl1-V5 (anti-V5; R960–25), FLAG-Neurog2 (anti-FLAG; F1804), A[N]bHLH-HA (anti-HA; ab9110).

Tubb3::T2A-GFPnls line was generated by designing two sgRNAs (5’ GCTGCGAGCAACTTCACTT and 5’ GAAGATGATGACGAGGAAT) to target Cas9 to the stop codon on Tubb3 Exon 4. Donor vector containing T2A peptide and GFP with a C-terminal nuclear localization signal was cloned in frame between ~800bp Tubb3 homologous arms flanking the stop codon. Coding sequence upstream of Tubb3 stop codon was amplified with 5’ CCCTACAACGCCACCCTGTCCAT (Forward) and 5’ CTTGGGCCCCTGGGCTTCTGATTCTTC (Reverse) primers. 3’ UTR sequence downstream of Tubb3 stop codon was amplified with 5’ AGTTGCTCGCAGCTGG (Forward) and 5’ CCAGCCTTCCCTGCGTTTTTTTC (Reverse) primers. Knock-in clones were selected for GFP expression after neuronal differentiation. p2Lox-Neurog2 plasmid was nucleofected to Tubb3::T2A-GFPnls ESC line to generate iNeurog2 Tubb3::GFP stable line.

The inducible mESCs were grown in 2i (2-inhibitors) based medium (Advanced DMEM/F12: Neurobasal (1:1) Medium (GIBCO), supplemented with 2.5% mESC-grade fetal bovine serum (vol/vol, Corning), N2 (GIBCO), B27 (GIBCO), 2mM L-glutamine (GIBCO), 0.1 mM ß-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO), 1000 U/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (Millipore), 3mM CHIR (BioVision) and 1 mM PD0325901 (Sigma) on 0.1% gelatin (Milipore) coated plates at 37°C, 8% CO2. To obtain embryoid bodies (EBs), 60–70% confluent mESCs were dissociated by TrpLE (Gibco) and plated in AK medium (Advanced DMEM/F12: Neurobasal (1:1) Medium, 10% Knockout SR (vol/vol) (GIBCO), Pen/Strep (GIBCO), 2mM L-glutamine and 0.1mM ß-mercaptoethanol) on untreated plates for two days (day −2) at at 37°C, 8% CO2. After two days, the EBs were passaged 1:2 and expression of the transgenes was induced by 3 ug/ml Doxycycline (Sigma D9891) to the AK medium. For differentiating mESC (EB) antibody stainings, RNA-seq, sc-RNAseq, and ATAC-seq experiments 2–3×105 cells were plated in each 100 mm untreated dishes (Corning). For ChIP-seq experiments, the same conditions were used, but seeded cell number was scaled up to 3–3.5×106 cells in 245 mm × 245 mm square dishes (Corning).

For day 9 attached neurons antibody stainings and calcium recording experiments, EBs induced with Doxycycline for two days (48hr+Dox) were dissociated with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) and plated on poly-D-lysine (P0899, Sigma) coated 4-well plates. The dissociated neurons were grown in neuronal medium with supplements (Neurobasal Medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, B27, 0.5 mM L-glutamine, 0.01 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 3ug/ml Doxycycline, 10 ng/mL GDNF (PeproTech 450–10), 10 ng/mL BDNF (PeproTech 450–02), 10 ng/mL CNTF (PeproTech 450–13), 10 uM Forskolin (Fisher BP2520–5), and 100 uM IBMX (Tocris 2845)) at 37 C°, 5% CO2. Anti-mitotic reagents 4 uM 5-Fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (Sigma F0503) and 4 uM Uridine (Sigma U3003) were used to kill any residual proliferating cells that might have failed neuronal differentiation.

Immunocytochemistry

Embryoid bodies were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (vol/vol) in PBS. Fixed EBs were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose and were embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek) and sectioned for staining. Primary antibody stainings were done by incubating overnight at 4°C, and secondary antibody stainings were done by incubating one hour at room temperature. Day 9 attached neuron stainings were done on coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine with same incubation times. After staining, samples were mounted with Fluoroshield with DAPI (Sigma). Images were acquired with a SP5 Leica confocal microscope. Below primary and secondary antibodies were used: anti-Tubb3 (Sigma, T2200, 1:2000), anti-V5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, R960–25, 1:5000), anti-Flag (Sigma, F1804; 1:500), anti-Map2 (abcam, ab5392, 1:1000), anti-Neurofilament (DSHB, 2H3, 1:1000), anti-HA (abcam, ab9110, 1:5000), Goat anti-chicken Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, A-11039, 1:1000), Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (Invitrogen, A-11036, 1:1000), Goat anti-mouse Alexa 647 (Invitrogen, A-21236, 1:1000).

Calcium imaging

750.000 dissociated iA, iN and iA[N]bHLH embryoid bodies were plated on 0.001% poly-D-lysine coated 35 mm glass bottom plates (MatTek, P35GC-1.5–10-C) and incubated for 9 days in neuronal medium (see above). To load neurons with calcium indicator, the cells were incubated for 30–60 min with 2 μM Fluo-4 AM (Thermo Fisher) and 0.02 % Pluronic F-127 (Invitrogen) in Ringer’s solution (150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2)54 at room temperature55. Fluo-4 fluorescence was excited with 488 nm light from a monochromatic Polychrome light source (Till Photonics) and emissions were filtered through a 500–550 nm bandpass filter (Chroma). Fluorescence images were acquired at 10 Hz with a cooled EM-CCD camera (Andor). Fluo-4 fluorescence was measured in regions of interest around the cell body of a given neuron. Bath solution exchanges were performed via a computer-controlled gravity-fed perfusion system (Automate Scientific). Excitation light, image acquisition, and hardware control were executed by the Live Acquisition software package (Till Photonics). Post-acquisition analysis was performed using custom Matlab scripts, which normalized changes in fluorescence to the pre-stimulus baseline fluorescence, which was computed as the mean of the 20 lowest fluorescence measurements taken prior to stimulus application.

RNA-seq

Cells were collected 0, 12 and 48 hours after Doxycycline induction and RNA was isolated by resuspending in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026) followed by purification using Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, 74106). RNA integrity was measured with Agilent High Sensitivity RNA Screentape (Agilent Tech, 5067–5080). 500 ng of RNA was spiked-in (1:100) with ERCC Exfold Spike-in mixes (Thermo Fisher, 4456739) for accurate comparison across samples. Illumina TruSeq LS kit v2 (RS-122–2001; RS-122–2002) was used to prepare RNA-seq libraries. The final quantification of the library before pooling was done with KAPA library amplification kit (Roche Lightcycler 480). The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 using V2 and V2.5 chemistry for 50 cycles (single-end) at the Genomics Core Facility at NYU.

Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq)

Cells (iAscl1-v5 and iNeurog2 Tubb3::GFP) were collected 48 hours after Dox induction and washes were done in 1X PBS with 0.04 mg/ml BSA (Thermo Fisher Sci AM2616). Cells were strained with CellTrics 30 μM (Cat #04–004-2326) to remove cell clumps. Equal number of iA and iN Tubb3::GFP cells were pooled to have 1000 cells/ul. 10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3’ library kit was used to generate single cell library for a targeted cell recovery rate of 10.000 cells (120262 Chromium™ i7 Multiplex Kit, 120236 Chromium™ Single Cell 3’ Chip Kit v2, 120237 Chromium™ Single Cell 3’ Library & Gel Bead Kit v2). Fragment length distribution of the library was determined by Agilent High Sensitivity DNA D1000 Screentape (5067– 5585) system and the final quantification of the library before pooling was done with KAPA library amplification kit (Roche Lightcycler 480). The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 High Output using V2.5 chemistry with 26×98 bp - 150 cycles run confirmation at the genomics core facility at NYU.

ChIP-seq

Cells were collected at 12 hours and 48 hours after TF induction and fixed with 1mM DSG (ProtoChem) followed by 1% FA (vol/vol) each for 15 min at room temperature. Pellets containing 25–30×106 cells were aliquoted and flash-frozen at −80°C. Cells were lysed in 50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol (vol/vol), 0.5% Igepal (vol/vol), 0.25% Triton X-100 (vol/vol) with 1X protease inhibitors (Roche, 11697498001) at 4°C. After 10 min, the cells were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol (vol/vol), 0.5% Igepal (vol/vol), 0.25% Triton X-100 (vol/vol) and incubated at 4°C. Nuclear extracts were resuspended in cold sonication buffer (50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate (wt/vol), 0.1% SDS (wt/vol). Sonication was performed on ice with Branson 450 digital sonifier (Marshall Scientific, B450CC) at 20% amplitude, 18 cycles of 30s ON/60s OFF into average size of approximately 300 bp. Immunoprecipitation was done overnight at 4°C on a rotator with Dynabeads protein-G (Thermo Fisher) conjugated antibodies. 5 ug of the following antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation: anti-Ascl1(abcam, ab74065), anti-Neurog2 (Santa Cruz, SC-19233), anti-HA (abcam, ab9110) anti-Brn2 (Santa Cruz, SC-6029), anti-Ebf2 (R&D, AF7006), anti-Onecut2 (R&D, AF6294), anti-H3K27ac (abcam, ab4729). Washes were done subsequently with 1X with sonication buffer (cold), sonication buffer with 500nM NaCl (cold), LiCl wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) (cold), 1 mM EDTA, 250mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) (cold), and TE buffer (10mMTris, 1mMEDTA, pH 8) (cold). Elution was done by adding Elution buffer (50mMTris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10mMEDTA (pH 8.0), 1% SDS) and incubating 45 min at 65°C. Eluted sample and input (sonicated, not ChIPed chromatin) were incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse the crosslink. RNA was digested by the addition of 0.2 mg/ml RNase A (Sigma) and incubating 2 hr at 37°C. Protein digestion was performed by adding 0.2mg/ml Proteinase K (Invitrogen) 30 min at 55°C. Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1; vol/vol) (Invitrogen) followed by ethanol precipitation were used for DNA extraction. The pellets were suspended in water and one third of ChIP DNA (1:100 dilution of input DNA) was used to prepare lllumina DNA sequencing libraries. Bioo Scientific multiplexed adapters were ligated after end repair and A-tailing, and unligated adapters were removed by purification using Agencourt AmpureXP beads (Beckman Coulter). Adapter-ligated DNA was amplified by PCR using TruSeq primers (Sigma). DNA libraries between 300 and 500 bp in size were purified from agarose gel purified using Qiagen minElute column and the final quantification of the library before pooling was done with KAPA library amplification kit (Roche Lightcycler 480). The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 using V2 chemistry for 50 cycles (single-end) and 75 cycles (single-end) at the genomics core facility at NYU.

ATAC-seq

50.000 cells were harvested and washed twice in cold 1X PBS. Cells were resuspended in 10mM Tris pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, and 0.1% NP-40 and centrifuged immediately at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 25 ul of 2x TD buffer, 2.5 ul TDE1 (Nextera DNA sample preparation kit, FC-121–1030) followed by incubation for 30 min at 37C. The reaction was then cleaned by Min-elute PCR purification kit (Qiagen, 28004). The optimal number of PCR cycles were determined to be the 1/3 of the maximum fluorescence measured by qPCR reaction with 1X SYBR Green (Invitrogen), custom designed primers56 and 2X NEB MasterMix (New England Labs, M0541). Following PCR enrichment, the library was cleaned with min-elute PCR kit and quantified using Qubit (Life Technologies, Q32854). The fragment length distribution of the library was determined by Agilent High Sensitivity DNA D1000 Screentape (5067– 5585) system and the final quantification of the library before pooling was done with KAPA library amplification kit (Roche Lightcycler 480). The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 using V2 chemistry for 150 cycles (paired-end 75 bp) at the genomics core facility at NYU.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

RNA-seq data analysis:

All RNA-seq fastq files were aligned to the mouse genome (version mm10) using Tophat (version 2.1.1)57 with options “-r 100 --no-coverage-search”. Rsubread58, an R package, was used to assign reads to genes defines using Refseq59 mm10 gene annotations. The Wald test in the DESeq2 package60 was used for differential gene expression analysis. A q-value cutoff of less than 0.01 was used for calling differentially expressed genes. PANTHER (version 13.1) (http://pantherdb.org) was used to perform Gene Ontology term enrichment analysis.

Single-cell RNA-seq data processing:

Fastq files were generated by using CellRanger (version 2.1.0) from 10X Genomics with default settings (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger). We added the transgene sequences to the reference genome manually to distinguish the two pooled cell lines: V5 (iAscl1) and GFP (iNeurog2 Tubb3::GFP) exogenous sequences were added to the end of chromosome 1 in FastA and GTF files of the mouse reference genome (mm10). A custom reference genome was generated by CellRanger mkref function by passing the modified FastA and GTF files. CellRanger count function was used to generate single cell feature counts for the library. Downstream analysis and graph visualizations were performed in Seurat R package61 (version 2.3.4). Briefly, we removed the cells that have unique gene counts greater than 6800 (potential doublets) and less than 200. After removing the unwanted cells, we normalized the data by a global-scaling normalization method (LogNormalize) with the default scale factor (10000). Linear dimensional reduction was performed by PCA and the clustering was performed by using the statistically significant principal components (identified by jackStraw method and by standard deviation of principle components). The results were visualized by tSNE plots.

ChIP-seq data processing:

All ChIP-seq fastq files were aligned to the mouse genome (version mm10) using Bowtie (1.0.1)62 with options “-q --best --strata -m 1 --chunkmbs 1024”. Only uniquely mapped reads were considered for further analysis. MultiGPS (version 0.74) was used to define transcription factor DNA binding events63. Cutoffs of fold enrichment ≥1.5 and q-value < 0.01 (assessed using binomial tests and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple hypothesis test correction), were used to call statistically significant binding events. Differential binding analysis between proneural TFs (Ascl1 vs Neurog2), between time points (12hr vs 48hr), or between factor inductions for the downstream TFs (iAscl1 vs iNeurog2) was also performed using MultiGPS, which calls EdgeR64 internally. Differentially bound sites are defined as those that display significantly greater read enrichment levels (q-value < 0.01) as determined by EdgeR’s negative binomial generalized linear models applied to MultiGPS’ per-replicate count data (TMM normalized). Shared binding events are defined as those that are called in both conditions, and not displaying significant differences in read enrichment level. To account for some differences in the numbers of peaks called for Neurog2 and Ascl1, some analyses of differential and shared binding restrict analysis to the top 10,000 most ChIP-enriched binding events for each of those TFs. When comparing binding site locations across distinct TF classes (e.g. Fig. 6a–c), we used a window size of 200bp to define overlapping sites.

ATAC-seq data processing:

All ATAC-seq data was mapped to the mouse genome (version mm10) using bowtie2–2.2.264 using “-q --very-sensitive” options. Enriched domains were identified using the DomainFinder module in SeqCode: (https://github.com/seqcode/seqcode-core/blob/master/src/org/seqcode/projects/seed/DomainFinder.java). Briefly, contiguous 50 bp genomic bins with significantly higher read enrichment compared to normalized input were identified (binomial test, p-value < 0.05). Further, contiguous blocks within 200 bp were joined together to call enriched domains. Differential ATAC-seq analysis was performed by first merging accessible domains across compared conditions (bedtools v.2.26.0: merge function with parameter -d100), counting ATAC-seq reads from each replicate which overlap the merged domains, and performing differential enrichment analysis with EdgeR64 (version 3.24, thresholds: 2-fold, p<0.01 (EdgeR’s negative binomial generalized linear models)).

Defining 0hr “active” and “inactive” regions:

A random forest classifier was trained to classify binding event locations as either being active or inactive at the 0hr time point (EB-embryoid bodies). The classifier was trained using H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, and ATAC-seq windowed read-enrichment as predictors. A union list of ~300,000 500 bp regions comprising the enriched domains (see above) of H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and ATAC-seq was used as the positive set for training the classifier. An equal number of unmarked 500 bp regions were randomly selected and used as the negative set for training the classifier. Weka’s implementation of Random Forests was used to train the classifier (https://github.com/seqcode/seqcode- core/blob/master/src/org/seqcode/ml/classification/BaggedRandomForest.java). Briefly, the forest contained 10,000 trees. Each tree was trained with 10 randomly sampled features on 1% bootstrapped samples of the entire dataset. Every binding event that was predicted to be in active 0h chromatin with a probability of greater than 0.8 was placed in the “active” class, while the remaining events were placed in the “inactive” class.

De novo motif discovery and k-mer analysis

MEME-ChIP (MEME suite version 4.11.3)65 was run on each of the subsets of Ascl1, Neurog2, Brn2, Ebf2, and Onecut2 binding sites using parameters “-meme-mod zoops -meme-minw 6 -meme-maxw 20”, and default parameters otherwise. Primary motif finding analyses (e.g. Fig. 2c) were performed on 50bp windows centered on the MultiGPS-defined binding event locations. Motif-finding analysis that aimed to find both primary and secondary motif signals (e.g. Fig. 6d–e) were performed on 150bp windows centered on the MultiGPS-defined binding event locations. Motif distribution plots (Fig. 6d–e) are produced by MEME-ChIP’s Centrimo function.

SeqUnwinder66 was used for label-specific de novo motif discovery. Briefly, all k-mers with lengths 4 and 5 were used as predictors. The SeqUnwinder classifier was trained to predict iAscl1-specific, iNeurog2-specific, and shared binding events. The heatmaps associating discovered motifs with each label are produced by SeqUnwinder.

For flanking k-mer analysis, we started with all possible 8-mers with the following restrictions: the 8-mers were restricted to contain the “CAGNTG” 6-mer subsequence and the remaining 2 characters were picked from the following set {A, T, G, C, N}. These restrictions resulted in a total of 150 8-mers. We used these 150 8-mers as predictors for a logistic regression classifier with L1 regularization. The classifier was trained on Ascl1- and Neurog2-specific binding sites. All non-zero weighted 8-mers were used for further analysis.

DNA shape properties around Ascl1 and Neurog2 sites were calculated using the DNAshapeR R package67 (version 1.10.0).

Transcription factor binding site and ATAC-seq heatmaps:

The MetaMaker program from the SeqCode project was used to generate heatmaps (https://github.com/seqcode/seqcode-core/blob/master/src/org/seqcode/viz/metaprofile/MetaMaker.java). Briefly, each row in a heatmap represents a 1000 bp window centered on the midpoint of a TF binding event. Reads were extended to 100 bp and overlapping read counts are binned into 10 bp bins. Color shading between white and a maximum color are used to represent depth of read coverage in each heatmap. We used a systematic approach to choose the read depth represented by the maximum color for each track. We first calculated the read counts in 10 bp bins at all identified binding sites for the given transcription factor and then used the 95th percentile value as the maximum value for the color pallet. The following are the read depths represented by the maximum color for different heatmaps: Ascl1: --linemin 15 --linemax 70; Neurog2: --linemin 15 --linemax 95; A[N]bHLH: --linemin 15 --linemax 90; Brn2 (iAscl1): --linemin 10 --linemax 99; Brn2 (iNeurog2): --linemin 10 --linemax 67; Ebf2 (iAscl1): --linemin 5 --linemax 76; Ebf2 (iNeurog2): --linemin 5 –linemax 106; Onecut2 (iAscl1): --linemin 5 –linemax 76; Onecut2 (iNeurog2): --linemin 5 –linemax 128. H3K27ac (EB) --linemin 15 --linemax 100;H3K27ac (iAscl1) --linemin 10 --linemax 75; H3K27ac (iNeurog2) --linemin 10 --linemax 55. ATAC-seq (EB) --linemin 10 --linemax 81; ATAC-seq(iASCL1 12h) --linemin 10 --linemax 46; ATAC-seq(iASCL1 48h) --linemin 10 --linemax 53; ATAC-seq (iNeurog2 12h) --linemin 10 --linemax 35; ATAC-seq(iNeurog2 48h) --linemin 10 --linemax 44; ATAC-seq(iA[N]bHLH 12h) --linemin 10 --linemax 33; ATAC-seq(iA[N]bHLH 48h) --linemin 10 --linemax 27.

Browser snapshots:

The ChipSeqFigureMaker program from the SeqCode project was used to generate the browser shots. (https://github.com/seqcode/seqcode-core/blob/master/src/org/seqcode/viz/genomicplot/ChipSeqFigureMaker.java)). Reads from both strands were merged and extended to 100 bp. The colors of the tracks were matched to the colors of the TF heat maps.

Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding site comparison

For all Ascl1 and Neurog2 binding site comparative analyses, we restricted to the top 10,000 binding events. The binding events were sorted based on q-value indicating significant enrichment over input ChIP-seq experiments. All top 10,000 Ascl1 binding events that showed significantly differential higher (q-value <0.01, EdgeR’s negative binomial generalized linear models) ChIP enrichment over Neurog2 ChIP were defined as “Ascl1-preferred” or “Ascl1>Neurog2” binding sites. Similarly, all top 10,000 Neurog2 binding events that showed significantly differential higher (q-value <0.01, EdgeR’s negative binomial generalized linear models) ChIP enrichment over Ascl1 ChIP were defined as “Neurog2-preferred” or “Neurog2>Ascl1” binding sites. All binding events in top 10,000 Ascl1 and Neurog2 lists, which were also not significantly enriched in either Ascl1 of Neurog2, were defined as “Shared” or “A=N” sites.

Associations between differential binding sites and differential expression

The GREAT command-line tools68 were used to define gene regulatory domains and to assess the associations between sets of binding sites and gene categories defined by the differential expression analyses. Regulatory domains were defined using the GREAT “basal plus extension” model with settings: basalUpstream=5000, basalDownstream=1000, maxExtension=100000. Gene sets evaluated in Fig. 7 represent genes that are significantly upregulated in both iA and iN compared with EBs (iA=iN), and genes that are significantly differentially expressed between iA and iN (iA>iN and iN>iA) for each relevant timepoint.

Sample size and statistical analysis

No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications69,70. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Biologically independent cell differentiations were used as replicates.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data produced for this study are available from the GEO database under accession GSE114176. We performed re-analysis of data sourced from GEO database entries GSE101397, GSE97715, and GSE43916.

Code availability

Analysis scripts are available from https://github.com/seqcode/Aydin_2019_iAscl1-vs-iNeurog2

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NICHD (R01HD079682) and Project ALS (A13–0416) to E.O.M. and by NYSTEM pre-doctoral training grant (C026880) to B.A. S.M. is supported by NIGMS (R01GM125722) and the National Science Foundation ABI Innovation Grant No. DBI1564466. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. M.R. is supported by NYU MSTP (T32GM007308) and Developmental Genetics T32 (T32HD007520) grants. N.F. and M.M.E. are supported by ERC Starting Grant (2011–281920). The authors would like to thank L. Tejavibulya and A. Ashokkumar for their help with molecular biology; M. Khalfan for his help with scRNA-seq analysis. M. Cammer from the NYU Medical Center Microscopy Core for the ImageJ script used in calcium imaging analysis; and NYU Genomics Core facility. Finally, we would like to thank S. Small, N. Konstantinidis, P. Onal, O. Wapinski, S. Ercan, C. Rushlow, C. Desplan and Mazzoni lab members for their helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Accession codes

All data produced for this study (RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and sc-RNAseq) are available from the GEO database under accession GSE114176.

References

- 1.Bertrand N, Castro DS & Guillemot F Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 3, 517–530 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillemot F & Hassan BA Beyond proneural: emerging functions and regulations of proneural proteins. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 42, 93–101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbán N & Guillemot F Neurogenesis in the embryonic and adult brain: same regulators, different roles. Front Cell Neurosci 8, 396 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuurmans C & Guillemot F Molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate specification in the developing telencephalon. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 12, 26–34 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parras CM et al. Divergent functions of the proneural genes Mash1 and Ngn2 in the specification of neuronal subtype identity. Genes Dev. 16, 324–338 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osório J, Mueller T, Rétaux S, Vernier P & Wullimann MF Phylotypic expression of the bHLH genes Neurogenin2, Neurod, and Mash1 in the mouse embryonic forebrain. J Comp Neurol 518, 851–871 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simionato E et al. atonal- and achaete-scute-related genes in the annelid Platynereis dumerilii: insights into the evolution of neural basic-Helix-Loop-Helix genes. Bmc Evol Biol 8, 1–13 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarman AP & Ahmed I The specificity of proneural genes in determining Drosophila sense organ identity. Mech. Dev 76, 117–125 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fode C et al. A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes Dev. 14, 67–80 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarman AP, Grau Y, Jan LY & Jan YN atonal is a proneural gene that directs chordotonal organ formation in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Cell 73, 1307–1321 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch MR, Tiveron MC, Guillemot F, Brunet JF & Goridis C Control of noradrenergic differentiation and Phox2a expression by MASH1 in the central and peripheral nervous system. Dev Camb Engl 125, 599–608 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo L, Dormand E, Greenwood A & Anderson DJ Comparison of the generic neuronal differentiation and neuron subtype specification functions of mammalian achaete-scute and atonal homologs in cultured neural progenitor cells. Development 129, 1553–1567 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Q, Fode C, Guillemot F & Anderson DJ Neurogenin1 and neurogenin2 control two distinct waves of neurogenesis in developing dorsal root ganglia. Genes Dev. 13, 1717–1728 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuurmans C et al. Sequential phases of cortical specification involve neurogenin-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 23, 2892–2902 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker NE & Brown NL All in the family : proneural bHLH genes and neuronal diversity. Development 145, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flames N & Hobert O Transcriptional control of the terminal fate of monoaminergic neurons. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 34, 153–184 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsunemoto R et al. Diverse reprogramming codes for neuronal identity. Nature 557, 380 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wichterle H, Gifford D & Mazzoni E Mapping neuronal diversity one cell at a time. Science (80-.). 341, 726–7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobert O Regulation of terminal differentiation programs in the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 27, 681–96 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefanakis N, Carrera I & Hobert O Regulatory Logic of Pan-Neuronal Gene Expression in C. elegans. Neuron 87, 733–750 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinrich C et al. Generation of subtype-specific neurons from postnatal astroglia of the mouse cerebral cortex. Nat. Protoc 6, 214–228 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanda S et al. Generation of Induced Neuronal Cells by the Single Reprogramming Factor ASCL1. Stem Cell Reports 3, 282–296 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y et al. Rapid Single-Step Induction of Functional Neurons from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Neuron 78, 785–798 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mall M et al. Myt1l safeguards neuronal identity by actively repressing many non-neuronal fates. Nature 544, 245–249 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wapinski OL et al. Hierarchical mechanisms for direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to neurons. Cell 155, 621–635 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadodaria KC et al. Generation of functional human serotonergic neurons from fibroblasts. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 49–61 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masserdotti G et al. Transcriptional Mechanisms of Proneural Factors and REST in Regulating Neuronal Reprogramming of Astrocytes. Cell Stem Cell 17, 74–88 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DK, Yang J, Liu M-LL & Zhang C-LL Small Molecules Modulate Chromatin Accessibility to Promote NEUROG2-Mediated Fibroblast-to-Neuron Reprogramming. Stem Cell Reports 7, 955–969 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soufi A et al. Pioneer transcription factors target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming. Cell 161, 555–568 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raposo AA et al. Ascl1 Coordinately Regulates Gene Expression and the Chromatin Landscape during Neurogenesis. Cell Rep 10, 1544–1556 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casey BH, Kollipara RK, Pozo K & Johnson JE Intrinsic DNA binding properties demonstrated for lineage-specifying basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Genome Biol 28, 484–496 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slattery M et al. Absence of a simple code: how transcription factors read the genome. Trends Biochem. Sci 39, 381–399 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell LM, Zur Lage PI, Prentice DR, Senthinathan B & Jarman AP The proneural proteins Atonal and Scute regulate neural target genes through different E-box binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol 24, 9517–9526 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castro DS et al. Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev. Cell 11, 831–844 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jolma A et al. DNA-binding specificities of human transcription factors. Cell 152, 327–339 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordân R et al. Genomic regions flanking E-box binding sites influence DNA binding specificity of bHLH transcription factors through DNA shape. Cell Rep 3, 1093–1104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohs R et al. Origins of specificity in protein-DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem 79, 233–269 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massari ME & Murre C Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol 20, 429–440 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma PC, Rould MA, Weintraub H & Pabo CO Crystal structure of MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex: perspectives on DNA recognition and implications for transcriptional activation. Cell 77, 451–459 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali FR et al. The phosphorylation status of Ascl1 is a key determinant of neuronal differentiation and maturation in vivo and in vitro. Development 141, 2216–2224 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hindley C et al. Post-translational modification of Ngn2 differentially affects transcription of distinct targets to regulate the balance between progenitor maintenance and differentiation. Development 139, 1718–1723 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quan X-J et al. Post-translational Control of the Temporal Dynamics of Transcription Factor Activity Regulates Neurogenesis. Cell 164, 460–475 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li S et al. RAS/ERK Signaling Controls Proneural Genetic Programs in Cortical Development and Gliomagenesis. J. Neurosci 34, 2169–2190 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S et al. GSK3 temporally regulates neurogenin 2 proneural activity in the neocortex. J. Neurosci 32, 7791–7805 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wapinski OL et al. Rapid Chromatin Switch in the Direct Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Neurons. Cell Rep. 20, 3236–3247 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fong AP et al. Conversion of MyoD to a neurogenic factor: binding site specificity determines lineage. Cell Rep 10, 1937–1946 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Masi F et al. Using a structural and logics systems approach to infer bHLH-DNA binding specificity determinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 4553–4563 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chien CT, Hsiao CD, Jan LY & Jan YN Neuronal type information encoded in the basic-helix-loop-helix domain of proneural genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13239–13244 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakada Y, Hunsaker TL, Henke MR & Johnson JE Distinct domains within Mash1 and Math1 are required for function in neuronal differentiation versus neuronal cell-type specification. Development 131, 1319–1330 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quan X-J et al. Evolution of neural precursor selection: functional divergence of proneural proteins. Development 131, 1679–1689 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iacovino M et al. Inducible cassette exchange: a rapid and efficient system enabling conditional gene expression in embryonic stem and primary cells. Stem Cells 29, 1580–1588 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazzoni EO et al. Embryonic stem cell-based mapping of developmental transcriptional programs. Nat. Methods 8, 1056–1058 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zappulo A et al. RNA localization is a key determinant of neurite-enriched proteome. Nat. Commun 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Groth RD, Lindskog M, Thiagarajan TC, Li L & Tsien RW Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase type II triggers upregulation of GluA1 to coordinate adaptation to synaptic inactivity in hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108, 828–833 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bootman MD, Rietdorf K, Collins T, Walker S & Sanderson M Loading fluorescent Ca2+ indicators into living cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc 8, 122–125 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY & Greenleaf WJ Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim D et al. TopHat2 : accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liao Y, Smyth GK & Shi W The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res 41, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]