Abstract

This preface forms part of the theme issue ‘Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: epidemic forecasting and control’. This theme issue is linked with the earlier issue ‘Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: approaches and important themes’.

1. Introduction

The twenty-first century has already seen many infectious disease outbreaks in human, animal and plant populations, including the outbreak of plague in Madagascar in 2017 [1], outbreaks of Foot and Mouth disease in countries including the United Kingdom [2,3] and Japan [4], and the outbreak of olive quick decline in Italy due to the bacterial pathogen Xyelella fastidiosa which was first detected in that country in 2013 [5]. In §2d of the main introductory article of this pair of theme issues [6], we describe three of the main uses of epidemiological models today, namely: (i) guiding surveillance; (ii) epidemic forecasting; and (iii) assessing the potential impacts of interventions. These analyses are increasingly carried out in real-time when outbreaks are ongoing [2,7–15].

In this theme issue, we present articles about epidemic detection, forecasting and control at different stages of an outbreak by researchers from across the complementary fields of mathematical epidemiology in human, animal and plant systems. The questions that models are used to address inevitably change throughout an outbreak, according to the needs of decision makers and/or public health teams. Questions that are considered in this theme issue include the following.

Before and early in an outbreak:

how vulnerable is the population to disease, where will the pathogen arrive and where should surveillance be focused? [16–18],

what is the current outbreak size, and where is the pathogen now? [20,21],

where and how can interventions be introduced to eradicate the pathogen quickly? [22], and

which data and resources are required to allow forecasting and control to be performed effectively? [10,20,23].

Once a major epidemic is ongoing:

how transmissible is the pathogen, by which transmission routes is it spreading, and how many cases will there be? [23–25],

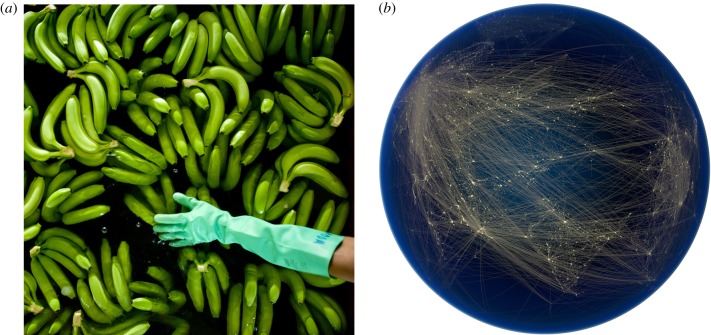

how effective are current control efforts (figure 1a)? [28], and

which interventions should be introduced, and how should they be adapted as the epidemic continues? [18,22,24,28–30].

At the end of a major epidemic:

can the epidemic be declared over, or do hidden cases remain in the population? [20,31].

Figure 1.

(a) Epidemiological models can be used to predict the impacts of current and proposed disease control measures in populations of humans, animals and plants. As an example of an intervention, fungicides are applied to banana plantations in Costa Rica 40–80 times per year to control Black Sigatoka disease, which has been exacerbated by climate change [26]. Here, bananas in another country—Columbia—are being washed prior to packing. Credit: David Bebber, 2017. This photograph is also the cover image of the linked theme issue ‘Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: approaches and important themes’. (b) Complex epidemiological models require detailed datasets for accurate parametrization. Here, a visualization of air traffic routes over Eurasia, which could be used to inform travel rates or connectivities in models of global pathogen transmission (e.g. [17,27]). Credit: Globaïa, 2011. This photograph is also the cover image of this theme issue. (Online version in colour.)

2. Requirements for outbreak modelling

In order to answer the types of questions outlined above, two important components are required. First, a model designed to answer the specific questions of interest is needed. For example, to predict the effects of interventions that are inherently spatial, such as culling all hosts within a fixed radius of known infecteds—a commonly used control for outbreaks in animal [32,33] and plant [34,35] populations—a spatially explicit epidemiological model is required. As described in the Introduction to the theme issue ‘Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: approaches and important themes' [6], a suite of modelling frameworks has been developed. For example, for representing outbreak dynamics, compartmental models that track the numbers of individuals in different infection or symptom states [36–39] or renewal equations that count the numbers of infections [40–42] can be used. For modelling disease surveillance, a number of statistical approaches have been designed [19,21,43].

Second, data relevant to the ongoing outbreak are required so that the model can be parametrized. To estimate the values of transmission parameters, temporal data are usually needed, such as time-series data describing the number of new cases in each time period (e.g. [44]). Because more data become available as an outbreak progresses, this leads to parameter estimates that change over time [45,46], and even to questions surrounding when parameters are known with sufficient certainty to allow action to be taken [45,47]. In certain scenarios, genetic data can provide information on temporal variables such as transmission rates between hosts or locations and rates of pathogen evolution [48–50]. The increasing complexity of models that are developed has led to the requirement for more data so that the models can be parametrized accurately, often including detailed datasets such as the precise locations of hosts in the landscape or travel routes and frequencies between different regions (figure 1b).

Data availability is extremely important. Despite well-documented instances in which crucial data were unavailable to modellers, such as during the early response to the 2014–16 Ebola epidemic [51], publically available datasets (such as those in the Project Tycho database [52]) and computing code (e.g. the code underlying the Nextstrain pathogen evolution tracker [53]) are increasingly common. Teaching tools such as the recent book by Ottar Bjørnstad [54] are introducing more mathematical modellers to epidemiological modelling. These advances are permitting the questions outlined above to be answered more accurately for pathogens in populations of humans, animals and plants.

3. Outlook

Collaboration between modellers, experimental or clinical epidemiologists and policy makers has been recommended in an attempt to build a framework that will allow outbreaks to be managed optimally [15,39,55]. However, collaboration between epidemiological modellers focused on different host types is encouraged more rarely [56]. Distinctions between different human, animal and plant populations and the pathogens that cause disease in those populations, such as the lack of adaptive immunity in plant hosts unlike in vertebrate animals [57], demand that certain research questions can only be addressed by modellers who are experts in particular systems.

However infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants also share many similarities [6]. Most of the questions addressed in this theme issue are relevant not only to particular pathogens in specific systems, but to almost all outbreaks irrespective of the type of host. As a result, we contend that increased collaboration between mathematical epidemiologists interested in infectious diseases of humans, animals and plants will lead to improved mathematical tools. Partnerships between modellers from different disciplines, combined with interaction with epidemiologists and decision makers, will permit epidemic responses to be performed most effectively.

We hope that this theme issue serves as a foundation on which to build this unified approach.

Biographies

Editors' biographies

Dr Robin Thompson is a Junior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford, UK, and is the lead guest editor of this pair of theme issues. His research involves using mathematical models to represent the epidemiological or evolutionary dynamics of infectious disease outbreaks in human, animal and plant populations. This includes using statistical methods to estimate parameters associated with pathogen transmission and developing stochastic or deterministic models for generating outbreak forecasts. These forward projections can be used to predict the effects of proposed control interventions. Robin has developed models for a range of infectious diseases in human and plant populations—including Ebola virus disease, HIV, sudden oak death and citrus greening. He also recently developed a method for determining the optimal time to introduce control of an invading pathogen, with applications to diseases of livestock.

Dr Ellen Brooks-Pollock is a Lecturer at the University of Bristol, UK. She is interested in applying mathematical modelling and data science to applied questions in the control of infectious diseases. She has spent a lot of time thinking about tuberculosis (TB) in humans, bovine TB in cattle and zoonotic TB transmission from cattle to humans, but is also branching out into Hepatitis A, influenza and vaccination strategies. Ellen has spoken about bovine TB on BBC1's Countryfile and BBC Radio 4's Farming Today and sits on the Editorial board for Mathematics Today.

Data accessibility

This article has no associated data.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

R.N.T. was funded by a Junior Research Fellowship from Christ Church, Oxford. E.B.P. was partly supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Evaluation of Interventions.

References

- 1.Roberts L. 2017. Echoes of Ebola as plague hits Madagascar. Science 358, 430–431. ( 10.1126/science.358.6362.430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson NM, Donnelly CA, Anderson RM. 2001. The foot-and-mouth epidemic in Great Britain: pattern of spread and impact of interventions. Science 292, 1155–1160. ( 10.1126/science.1061020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson I.2008. Foot and Mouth disease 2007: a review and lessons learned. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/foot-and-mouth-disease-2007-a-review-and-lessons-learned .

- 4.Muroga N, Hayama Y, Yamamoto T, Kurogi A, Tsuda T, Tsutsui T. 2011. The 2010 foot-and-mouth disease epidemic in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 74, 399–404. ( 10.1292/jvms.11-0271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida RPP. 2016. Can Apulia's olive trees be saved? Science 353, 346–348. ( 10.1126/science.aaf9710) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson RN, Brooks-Pollock E. 2019. Preface to theme issue ‘Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: epidemic forecasting and control’. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20190375 ( 10.1098/rstb.2019.0375) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keeling MJ, et al. 2001. Dynamics of the 2001 UK foot and mouth epidemic: stochastic dispersal in a heterogeneous landscape. Science 294, 813–818. ( 10.1126/science.1065973) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Ebola Response Team. 2014. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl. J. Med. 371, 1481–1495. ( 10.15678/EBER.2017.050110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funk S, Camacho A, Kucharski AJ, Eggo RM, Edmunds WJ. 2018. Real-time forecasting of infectious disease dynamics with a stochastic semi-mechanistic model. Epidemics 22, 56–61. ( 10.1016/j.epidem.2016.11.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McRoberts N, Figuera SG, Olkowski S, McGuire B, Luo W, Posny D, Gottwald T. 2019. Using models to provide rapid programme support for California's efforts to suppress Huanglongbing disease of citrus. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180281 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0281) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camacho A, et al. 2015. Temporal changes in Ebola transmission in Sierra Leone and implications for control requirements: a real-time modelling study. PLoS Curr. 7, 1–12. ( 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.406ae55e83ec0b5193e3085) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey A, Atkins KE, Medlock J, Wenzel N, Townsend JP, Childs JE, Nyenswah TG, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Galvani AP. 2014. Strategies for containing Ebola in West Africa. Science 346, 991–995. ( 10.1126/science.1260612) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DEFRA. 2013. Chalara management plan. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chalara-management-plan.

- 14.Gomes MFC, Piontti Ay, Rossi L, Chao D, Longini I, Halloran ME, Vespignani A. 2014. Assessing the international spreading risk associated with the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak. PLoS Curr. 6 ( 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.cd818f63d40e24aef769dda7df9e0da5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalf CJE, Edmunds WJ, Lessler J. 2014. Six challenges in modelling for public health policy. Epidemics 10, 93–96. ( 10.1016/j.epidem.2014.08.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kajero O, Del Rio Vilas V, Wood JLN, Lo Iacono G. 2019. New methodologies for the estimation of population vulnerability to diseases: a case study of Lassa fever and Ebola in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180265 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottwald T, Luo W, Posny D, Riley T, Louws F. 2019. A probabilistic census-travel model to predict introduction sites of exotic plant, animal and human pathogens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180260 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0260) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaters GL, et al. 2019. Analysing livestock network data for infectious disease control: an argument for routine data collection in emerging economies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180264 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0264) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastin AJ, van den Bosch F, van den Berg F, Parnell SR. 2019. Quantifying the hidden costs of imperfect detection for early detection surveillance. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180261 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan O. 2019. How decision makers can use quantitative approaches to guide outbreak responses. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180365 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0365) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourhis Y, Gottwald T, van den Bosch F. 2019. Translating surveillance data into incidence estimates. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180262 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0262) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker L, Matthiopoulos J, Müller T, Freuling C, Hampson K. 2019. Optimizing spatial and seasonal deployment of vaccination campaigns to eliminate wildlife rabies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180280 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0280) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polonsky JA, et al. 2019. Outbreak analytics: a developing data science for informing the response to emerging pathogens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180276 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0276) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaydos DA, Petrasova A, Cobb RC, Meentemeyer RK. 2019. Forecasting and control of emerging infectious forest disease through participatory modelling. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180283 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0283) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rushton SP, Sanderson RA, Reid WDK, Shirley MDF, Harris JP, Hunter PR, O'Brien SJ. 2019. Transmission routes of rare seasonal diseases: the case of norovirus infections. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180267 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0267) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bebber DP. 2019. Climate change effects on Black Sigatoka disease of banana. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180269 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0269) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson RN, Thompson CP, Pelerman O, Gupta S, Obolski U. 2019. Increased frequency of travel in the presence of cross-immunity may act to decrease the chance of a global pandemic. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180274 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0274) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaminsky J, Keegan LT, Metcalf CJE, Lessler J. 2019. Perfect counterfactuals for epidemic simulations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180279 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0279) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Probert WJM, Lakkur S, Fonnesbeck CJ, Shea K, Runge MC, Tildesley MJ, Ferrari MJ.. 2019. Context matters: using reinforcement learning to develop human-readable, state-dependent outbreak response policies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180277 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0277) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bussell EH, Dangerfield CE, Gilligan CA, Cunniffe NJ. 2019. Applying optimal control theory to complex epidemiological models to inform real-world disease management. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180284 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson RN, Morgan OW, Jalava K. 2019. Rigorous surveillance is necessary for high confidence in end-of-outbreak declarations for Ebola and other infectious diseases. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180431 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0431) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tildesley MJ, Savill NJ, Shaw DJ, Deardon R, Brooks SP, Woolhouse MEJ, Grenfell BT, Keeling MJ. 2006. Optimal reactive vaccination strategies for a foot-and-mouth outbreak in the UK. Nature 440, 83–86. ( 10.1038/nature04324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tildesley MJ, House TA, Bruhn MC, Curry RJ, Neil MO, Allpress JLE, Smith G, Keeling MJ. 2010. Impact of spatial clustering on disease transmission and optimal control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1041–1046. ( 10.1073/pnas.0909047107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunniffe NJ, Stutt ROJH, DeSimone RE, Gottwald TR, Gilligan CA. 2015. Optimising and communicating options for the control of invasive plant disease when there is epidemiological uncertainty. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004211 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004211) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyatt-Twynam SR, Parnell S, Stutt ROJH, Gottwald TR, Gilligan CA, Cunniffe NJ. 2017. Risk-based management of invading plant disease. New Phytol. 214, 1317–1329. ( 10.1111/nph.14488) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keeling MJ, Rohani P. 2008. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleczkowski A, Hoyle A, McMenemy P. 2019. One model to rule them all? Modelling approaches across OneHealth for human, animal and plant epidemics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180255 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0255) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson RN, Gilligan CA, Cunniffe NJ. 2016. Detecting presymptomatic infection is necessary to forecast major epidemics in the earliest stages of infectious disease outbreaks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004836 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004836) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson RN, Hart WS. 2018. Effect of confusing symptoms and infectiousness on forecasting and control of Ebola outbreaks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67, 1472–1474. ( 10.1093/cid/ciy248) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nouvellet P, Cori A, Garske T, Blake IM, Dorigatti I, Hinsley W et al. 2018. A simple approach to measure transmissibility and forecast incidence. Epidemics 22, 29–35. ( 10.1016/j.epidem.2017.02.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H, Nishiura H. 2019. Sexual transmission and the probability of an end of the Ebola virus disease epidemic. J. Theor. Biol. 471, 1–12. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.03.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Champredon D, Dushoff J, Earn DJD. 2018. Equivalence of the Erlang-distributed SEIR epidemic model and the renewal equation. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 78, 3258–3278. ( 10.1137/18M1186411) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parnell S, van den Bosch F, Gottwald T, Gilligan CA. 2017. Surveillance to inform control of emerging plant diseases: an epidemiological perspective. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 591–610. ( 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035334) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noori N, Rohani P. 2019. Quantifying the consequences of measles-induced immune modulation for whooping cough epidemiology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180270 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson RN, Gilligan CA, Cunniffe NJ. 2018. Control fast or control smart: when should invading pathogens be controlled? PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006014 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cori A, et al. 2017. Key data for outbreak evaluation: building on the Ebola experience. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160371 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ludkovski M, Niemi J. 2010. Optimal dynamic policies for influenza management. Stat. Commun. Infect. Dis. 2 ( 10.2202/1948-4690.1020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lycett SJ, Duchatel F, Digard P. 2019. A brief history of bird flu. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180257 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0257) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Archie EA, Luikart G, Ezenwa VO. 2009. Infecting epidemiology with genetics: a new frontier in disease ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 21–30. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.08.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hill SC, et al. 2019. Comparative micro-epidemiology of pathogenic avian influenza virus outbreaks in a wild bird population. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 374, 20180259 ( 10.1098/rstb.2018.0259) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitty CJM, Mundel T, Farrar J, Heymann DL, Davies SC, Walport MJ. 2015. Providing incentives to share data early in health emergencies: the role of journal editors. Lancet 386, 1797–1798. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00758-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tycho Team Science for Data and Health. 2017 Project Tycho, v.2.0 See https://www.tycho.pitt.edu.

- 53.Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, Sagulenko P, Bedford T, Neher RA. 2018. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bjørnstad O. 2018. Epidemics: models and data using R. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knight GM, Dharan NJ, Fox GJ, Stennis N, Zwerling A, Khurana R, Dowdy DW. 2019. Bridging the gap between evidence and policy for infectious diseases: how models can aid public health decision-making. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 42, 17–23. ( 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunniffe NJ, Koskella B, Metcalf CJE, Parnell S, Gottwald TR, Gilligan CA. 2015. Thirteen challenges in modelling plant diseases. Epidemics. Elsevier B. V. 10, 6–10. ( 10.1016/j.epidem.2014.06.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kushalappa AC, Yogendra KN, Karre S. 2016. Plant innate immune response: qualitative and quantitative resistance. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 35, 38–55. ( 10.1080/07352689.2016.1148980) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no associated data.