Abstract

Geroprotectors are compounds that slow the rate of biological aging and therefore may reduce the incidence of age-associated diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, few have therapeutic efficacy in mammalian AD models. Here we describe the identification of geroneuroprotectors (GNPs), novel AD drug candidates that meet the criteria for geroprotectors.

Geroprotectors: Compounds that Slow Aging

Perhaps the greatest challenge to modern medicine is to prevent or delay the diseases of aging. The most recalcitrant of these is AD. One approach to AD therapies is to identify drug candidates that slow aging and extend lifespan in model organisms. These compounds are called geroprotectors and it has been argued that their ability to extend lifespan in model organisms may translate to a healthier lifespan in humans. The hypothesis is that by delaying biological aspects of aging there will be a simultaneous delay in the chronic diseases associated with aging because they share the same physiological risk factor, the aging process itself. To date, there are about 200 compounds that extend either median or maximal lifespan in yeast, flies, and/or worms [1]. Analysis of these compounds points to the central importance of several key molecular pathways in life extension and healthy aging, including the AMP-activated kinase (AMP kinase) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways [2,3].

Since the AMP kinase and mTOR pathways exist in all cells, but are engaged by a variety of mechanisms, it is currently unclear whether geroprotectors extend lifespan by slowing aging in all tissues equally or whether different geroprotectors protect specific tissues thereby decreasing overall mortality. In the few cases in which the targets of geroprotectors were identified, they were expressed in a tissue-specific manner [4]. These observations suggest that by using the proper selection criteria, geroprotectors could be identified that pass the blood–brain barrier and protect the brain in addition to affecting aging pathways that are shared with other tissues. We term these compounds GNPs and describe herein the set of phenotypic screening assays that have been used to identify these compounds.

A Novel Screening Platform Identifies GNPs

If the goal is to promote healthier brain aging and long-term neural function, what are the criteria that can be used to identify functional GNP drug candidates? First, a GNP should protect from multiple brain toxicities that are known to increase with age. Examples of age-associated brain toxicities include reduced energy metabolism, proteotoxicity, inflammation, and oxidative damage. Second, GNPs should not be disease specific but should show beneficial effects in multiple neurodegenerative diseases as well as other age-related conditions. Thus, GNPs should have therapeutic efficacy in animals that die from age-related multimorbidity. Third, it is not sufficient to simply show an effect on lifespan, because a new GNP drug candidate will be required to have a disease-modifying property to obtain FDA approval for clinical trials. Finally, a GNP must have the ability to reduce, or at least to slow, age-associated physiological and molecular changes even if treatment is initiated in aged animals or at symptomatic stages of the disease. While most published geroprotector studies have initiated treatment in young adults [1], a GNP should ideally function when given to older individuals.

Here, we outline a plausible drug discovery pipeline for the identification and characterization of GNP drug candidates using cell culture assays that recapitulate multiple age-associated toxicities of the brain. The pipeline is based on a group of phenotypic screening assays described in [5] and listed in Table 1. Importantly, all of the assays reflect conditions that are more robust in the aged and diseased brain relative to age-matched controls.

Table 1.

Brain Toxicities of Old Age as a Drug Screening Platforma

| Assay | Pathway | Metformin | Rapamycin | Curcumin | J147 | CAD31 | Fisetin | CMS121 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC65 cells | Ab toxicity | 1.5 mM | >10 µM | >20 µM | 34 nM | 12 nM | 2.7 µM | 90 nM |

| Oxytosis | Oxidative stress | 10 mM | >10 µM | 6 µM | 11 nM | 20 nM | 3 µM | 200 nM |

| In vitro ischemia | Energy loss | >10 mM | >10 µ M | 100 nM | 180 nM | 47 nM | 3 µM | 7 nM |

| Microglial activation | Inflammation | 2.5 mM | 100 nM | 8 µM | >10 µM | 10 µM | 5 µM | 1 µM |

| Trophic factor withdrawal | Growth factor loss | >2 mM | >10 µM | >20 µM | 27 nM | 18 nM | 2.2 µM | 70 nM |

| PC12 neurites | Nerve cell differentiation | >10 mM | >10 µM | >10 µM | >10 µM | >10 µM | 5 µM | 2.5 µM |

Curcumin and fisetin along with their synthetic derivatives were screened from the highest nontoxic amount (100 µM) down to 10 nM in the six screening assays described in [5]. The concentration that produces 50% of the maximal effect in each assay (EC50) is given. For comparison, two well-studied geroprotectors, metformin and rapamycin, were included in these assays. The data are from [2,3,5,6,8–12,17,18].

These include assays for amyloid beta proteotoxicity, protection against oxidative stress (oxytosis), protection against a reduction of ATP synthesis (in vitro ischemia), anti-inflammatory activity (microglial activation), protection against loss of the trophic factors that nerve cells depend on for survival (trophic factor withdrawal), and the ability to induce the differentiation of PC12 sympathetic-like neurons (PC12 cells), a property of some trophic factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF). Screening of natural product libraries using these assays yielded fisetin and curcumin as lead compounds [5,6,12].

We and many others have studied the preclinical efficacy and molecular pathways initiated by these natural compounds in multiple cell culture systems and animal models of neurodegeneration, including stroke, AD and dementia, Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease [6,7]. Subsequent medicinal chemistry based on structure–activity relationship studies and the GNP selection assays listed in Table 1 as phenotypic readouts yielded the synthetic derivatives of curcumin, CAD31, and J147 and the synthetic derivative of fisetin, CMS121 [8–12]. These compounds are several orders of magnitude more potent than their natural precursors, yet they maintain the biological activities of the parent compounds (Table 1).

New GNPs Share Antiaging Pathways with Geroprotectors

As predicted from the GNP selection assays, J147, CAD31, and CMS121 are effective in multiple rodent models of AD. They improve memory, reduce inflammation, maintain synapses, and remove toxic amyloid peptide [5,9–13]. More surprising was the finding that they and their natural product precursors extend life-span and/or delay physiological and molecular aspects of aging [9,11,13,14].

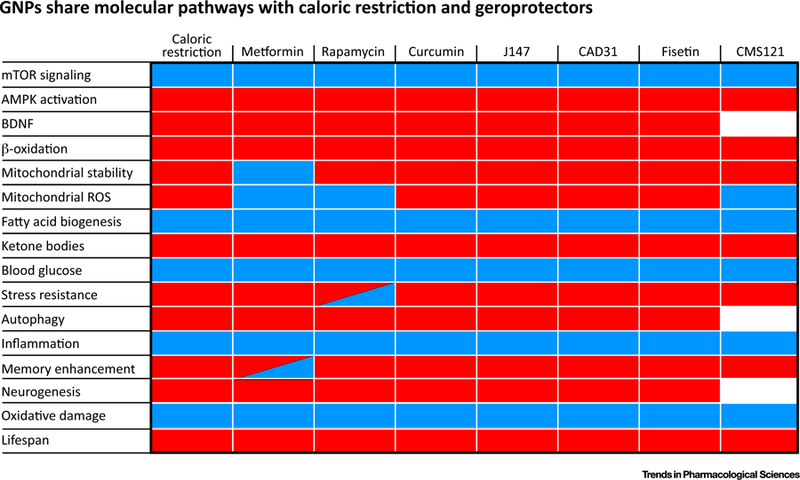

A limited number of molecular pathways associated with reducing the rate of aging in model organisms have been identified, most of which are associated with the experimental manipulation of caloric restriction or treatment with metformin or rapamycin [2,3,15]. If CMS121, J147, and CAD31 are bona fide GNPs, the molecular pathways modified by them should include those that are modified by caloric restriction, metformin, and rapamycin. Figure 1 shows that they indeed engage many of the same pathways. Their robust effects across many in vitro and in vivo systems at nanomolar concentrations should clearly dispel any notion that polyphenolic compounds make poor lead compounds and cannot be chemically improved while still maintaining their biological activities [8–10,12].

Figure 1. Geroneuroprotectors (GNPs) Share Molecular Pathways with Caloric Restriction and Geroprotectors.

Heatmap of molecular pathways activated (shown as red) or inhibited (shown as blue) by the different compounds is shown. White spaces denote that the effects were not determined whereas the hatched boxes depict publications showing both activation and inhibition. Data are compiled from [2,3,5–20].

J147 is the best-studied curcumin derivative. It is effective in over a dozen rodent models of neurodegenerative diseases and memory enhancement [9,10,12,13]. Its mechanistic target is a subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase that was also found to promote life extension in worms [9]. These data strongly support the designation of J147 as a GNP. CAD31 is a derivative of J147 that has many of the same neuroprotective properties and also stimulates nerve stem cell division [10,11]. Fisetin has been extensively studied in both transgenic mice expressing genes that cause the familial form of AD (APPswe/PSdeltaE9 mice) [16] and old, rapidly aging SAMP8 mice [14]. SAMP8 mice are perhaps the best rodent model to study drug effects on multimorbidity and sporadic dementia [13,14]. CMS121 has the same GNP properties as fisetin but a much higher level of potency (Table 1).

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

We show that selecting compounds using phenotypic screens that reflect toxicities associated with the aging brain have yielded several drug candidates that are neuroprotective in multiple age-related neurodegenerative disease models and have geroprotective properties. These define a new class of human GNP drug candidates that could be used alone or in combination with disease-specific compounds for the treatment of old-age-associated neurodegenerative diseases and, perhaps, aging itself. An Investigational New Drug (IND) application for J147 is currently in the filing process and CMS121 recently received NIH funding for IND studies. We believe that the novel screening platform described here can move multiple new drug candidates to IND studies and beyond. In addition, this approach could potentially generate a greater interest in incorporating phenotypic screening and geroscience into future drug discovery for AD as well as other age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

The work outlined in this Forum was supported by the NIH (RO1 AG046153 and RF1 AG054714 to P.M. and D.S. and R41AI104034 to P.M.), the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) (D.S.), and the Edward N. & Della Thome Memorial Foundation (P.M.) and the Paul F. Glenn Center for Aging Research at the Salk Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer Statement

D.S. is an unpaid science advisor for Abrexa Pharmaceuticals that is working to get J147 into clinical trials.

References

- 1.Moskalev A et al. (2015) Geroprotectors.org: a new, structured and curated database of current therpeutic interventions in aging and age-related disease. Aging (Albany N. Y.) 7, 616–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson SC et al. (2013) mTOR is a key regulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature 493, 338–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salminen A and Kaarniranta K (2012) AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via an integrated signaling network. Ageing Res. Rev 11, 230–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrascheck M et al. (2007) An antidepressant that extends lifespan in adult Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 450, 553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prior M et al. (2014) Back to the future with phenotypic screening. ACS Chem. Neurosci 5, 503–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher P (2015) How fisetin reduces the impact of age and disease on CNS function. Front. Biosci 7, 58–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma QL et al. (2013) Curcumin suppresses soluble tau dimers and corrects molecular chaperone, synpatic and behavioral deficits in aged human tau transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem 288, 4056–4065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiruta C et al. (2012) Chemical modification of the multi- target neuroprotective compound fisetin. J. Med. Chem 55, 378–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg J et al. (2018) The mitochondrial ATP synthase is a shared drug target for aging and dementia. Aging Cell 17, 12715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prior M et al. (2016) Selecting for neurogenic potential as an alternative for Alzheimer’s disease drug discovery. Alzheimer Dement 12, 678–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daughtery D et al. (2017) A novel Alzheimer’s disease drug candidate targeting inflammation and fatty acid metabolism. Alzheimers Res. Ther 9, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Q et al. (2011) A novel neurotrophic drug for cognitive enhancement and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 6, e27865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Currais A et al. (2015) A comprehensive multiomics approach toward understanding the relationship between aging and dementia. Aging 7, 937–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Currais A et al. (2018) Fisetin reduces the impact of aging on behavior and physiology in the rapidly aging SAMP8 mouse. J. Gerentol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 73, 299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Lluch G and Navas P (2016) Calorie restriction as an intervention in aging. J. Physiol 594, 2043–2060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currais A et al. (2014) Modulation of p25 and inflammatory pathways by fisetin maintains cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Aging Cell 13, 379–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viollet B et al. (2012) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 122, 253–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu S et al. (2015) Clinical development of curcumin in neurodegenerative disease. Expert Rev. Neurother 15, 629–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pernicova I and Kornbonits M (2014) Metformin – mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 10, 143–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Z et al. (2015) Rapamycin and calorie restriction induce metabolically distinct changes in mouse liver. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 70, 410–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]