Abstract

The selection of desirable traits in crops during domestication has been well studied. Many crops share a suite of modified phenotypic characteristics collectively known as the domestication syndrome. In this sense, crops have convergently evolved. Previous work has demonstrated that, at least in some instances, convergence for domestication traits has been achieved through parallel molecular means. However, both demography and selection during domestication may have placed limits on evolutionary potential and reduced opportunities for convergent adaptation during post-domestication migration to new environments. Here we review current knowledge regarding trait convergence in the cereal grasses and consider whether the complexity and dynamism of cereal genomes (e.g., transposable elements, polyploidy, genome size) helped these species overcome potential limitations owing to domestication and achieve broad subsequent adaptation, in many cases through parallel means.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Convergent evolution in the genomics era: new insights and directions’.

Keywords: domestication, adaptation, convergence, evolution, plants

1. Introduction

Certain species of plants have been continually selected over the past 10 000 years to better meet the needs of humans. Similar selection pressure has favoured traits that consistently distinguish these domesticated crops from their wild progenitors [1], distinctions that are shared even among distantly related species such as maize and sunflower. These traits include increased yield, apical dominance or lack of branching, loss of seed dormancy, loss of bitterness and loss of shattering or seed dispersal. Collectively, this suite of shared traits is known as the domestication syndrome [2].

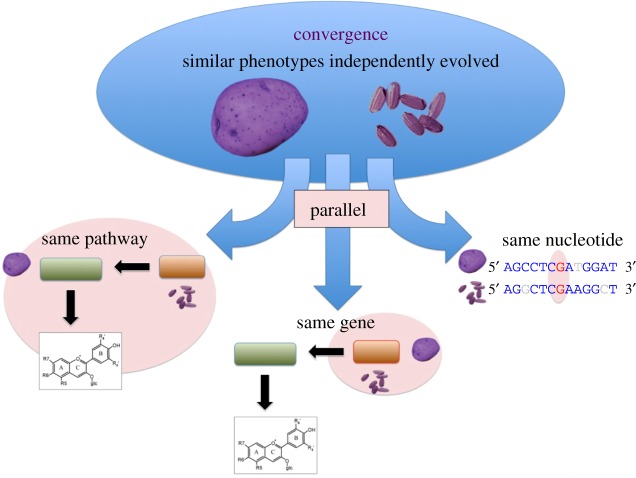

Trait sharing among diverged species such as maize and sunflower (their last common ancestor was 150 Ma [3]) is an example of the phenomenon of convergence. Convergent traits can arise from unrelated genes in different enzymatic pathways, such as fruit/seed indehiscence in both dicot and monocot crops (reviewed in [4]). But if a convergent trait is caused by repeated modification of the same molecular pathway, orthologue, or nucleotide, we define this as parallelism [5] (figure 1). We expect that parallelism is more likely to occur in closely related species owing to their similar complement of genes and pathways [6] and less likely to occur in substantially diverged species that contain fewer orthologous loci and pathways [6,7].

Figure 1.

Parallelism in convergence. Convergence is the phenomenon whereby similar traits, such as purple pigmentation in potato and rice in this example, arise independently in different species. Parallelism is when convergent traits are caused by modification of the same molecular pathways, genes or nucleotides. (Online version in colour.)

After the initial wave of crop domestication yielded convergence in many of the aforementioned domestication syndrome traits, another period of trait evolution ensued—the adaptation of crop species to varied environmental conditions and pathogens during global expansion. A variety of maize bred for cultivation at sea level, for instance, may not necessarily thrive in the colder, higher-UV environment of the Andes mountain range. Therefore, cultivators in the Andes must have looked for individuals in the existing domesticated maize population that were hardy under these new conditions. However, crop adaptation occurred under genetic limitations not experienced during domestication of wild progenitors [8].

Only a subset of genome-wide diversity was retained in initial domesticates and additional diversity was lost through subsampling events during crop expansion. Furthermore, selection on particular alleles coding for domestication traits often resulted in dramatic reductions in diversity in particular chromosomal regions. The effects of this loss of genetic diversity on the potential for adaptation has been documented. For example, a dramatic genetic bottleneck in the ‘lumper’ variety of potato led to a catastrophic outbreak of Phytopthera infestans, resulting in the infamous potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s [9]. The potato famine demonstrated that, by divesting a crop cultivar of its diversity, the cultivar loses its ability to adapt to newly encountered environmental pressures, because the alleles that code for adaptive traits such as, for instance, disease resistance are lost.

This review will consider the extent to which selection and bottlenecks during domestication have affected the potential for convergence and parallel adaptation post-domestication. We will focus mainly on cereal grass crops since the major domesticates—maize, rice, sorghum, wheat, barley and millet—include a range of divergence times conducive to both parallel domestication and adaptation. While the cereals have documented the loss of diversity owing to domestication and subsequent expansion, they possess dynamic genomes with frequent polyploidization, transposable element (TE) activity and labile genome size. These features may have provided cereals with an advantage in escaping the limits of domestication by generating novel diversity upon which adaptation could act.

2. The effects of domestication on adaptation in the cereals

(a). Domestication in the cereals

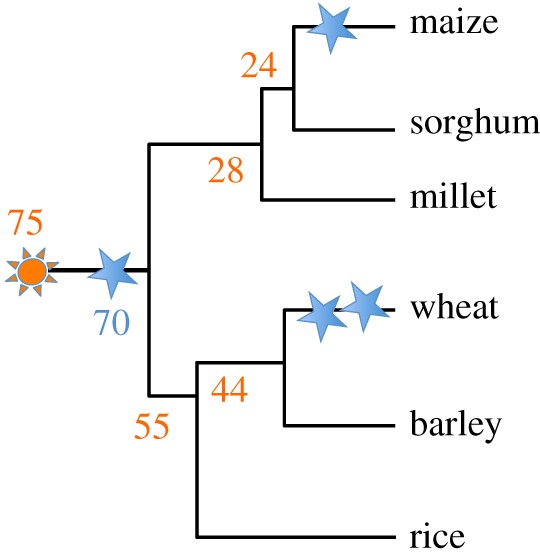

Cereal grasses have often been studied as a cohesive genetic group [10,11], and there are many reasons why they present a compelling system for studying crop domestication and adaptation. The grass clade is thought to have arisen around 75 Ma [12,13], eventually leading to the rice, wheat, barley, millet, maize and sorghum lineages (figure 2). Prior to the radiation of the grasses, however, a genome duplication event occurred approximately 70 Ma [14], which is shared among all grass crops (figure 2). Subsequently, both maize and wheat have undergone additional, lineage-specific polyploidy events (figure 2) [15]. These polyploidy events, followed by selective and ongoing fractionation, present an opportunity for grass genomes to evolve subfunctionalized homeologs; this, along with relatively high transposon activity (particularly in maize and wheat) [16,17], provides substantial functional diversity upon which selection can act during domestication and adaptation.

Figure 2.

Simple cladogram of major cereal speciation. Numbers are in Ma (millions of years ago). Orange sun: grass speciation event 75 Ma. Blue stars: polyploidy events; the major grass polyploidy event immediately after the grass speciation event occurred approximately 70 Ma. The Ehrhartoideae clade, which includes rice, arose approximately 55 Ma. The Pooideae clade, which includes wheat and barley, arose around 44 Ma; Chloridoideae, which contains foxtail millet 28 Ma, and the Panicoids, which include maize and sorghum, arose approximately 24 Ma. The branch length is not proportional to the number of substitutions per site. (Online version in colour.)

Collectively, cereals have been targeted by human selection for millable grain. Components of the domestication syndrome convergently selected within grain include increased seed size, loss of seed dormancy, loss of bitterness, loss of shattering or seed dispersal [18], fragrance [13] and glutinous seeds [19]. Plant architecture traits such as apical dominance or lack of branching have also been convergently targeted [18]. A number of well-characterized or candidate domestication genes are known in the cereals and have been described in table 1. This table includes an expanded set of loci and information beyond that originally published in [18]. While parallelism can occur for convergent traits at the level of the nucleotide, gene or pathway (figure 1), orthology, or shared functional genes across species, is currently best characterized and is therefore our primary focus in table 1 and throughout the article. Cereal domestication genes are categorized based on whether they occur strictly within a species, share orthologues across the grasses, share orthologues within and outside of the grasses or share orthologues entirely outside of the grasses (Column 5, table 1). This provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent of parallelism for a convergent domestication trait. In Column 1 of table 1, we indicate whether a gene is thought to be associated with a domestication trait, and in Column 8 whether the gene is expected to be selected in parallel, depending on whether it has known orthologues in other species that are associated with the given domestication trait. For instance, fragrance is a convergent domestication trait that is shared among species as diverse as rice and soya bean, and it is likely to have been selected in parallel, since orthologues of the fragrance-associated gene BADH2 have been independently targeted (table 1). Another convergent trait likely to have been selected in parallel is glutinous seeds, since the Waxy gene that confers the glutinous trait has targeted orthologues in nearly all cereals and beyond (reviewed in [19]). Shattering also shows evidence of parallel selection in the cereals with orthologues of Sh1 selected in sorghum, rice and maize [38]. With regard to convergence and parallelism during domestication, one clear message emerges from the evaluation of table 1: while we have much left to characterize regarding the genetic basis of domestication across the cereals, both phenomena are not rare.

Table 1.

Parallel or convergent orthologies (adapted from Lenser and Theissen, 2013 [18]).

| trait type | phenotypic trait | crop species | orthologue phylogeny | phylogeny of domestication trait | orthologous gene(s) | gene product | potentially parallel? | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| domestication | determinate growth | tomato, soya bean, common bean | family/above family | outside the cereals | SP, Dt1, PvTFL1y | signalling protein | parallel | [1,20–23] |

| domestication | dwarfism | rice, barley | family | cereal-wide | OsGA20ox-2, HvGA20ox-2 | metabolic enzyme | parallel | [24–26] |

| domestication | dwarfism | sorghum, pearl millet | family | cereal-wide | dw3, d2 | transporter protein | parallel | [27,28] |

| domestication | dwarfism | wheat | species | species-specific, cereals | Rht-1 | SH2-TF | unknown | [1] |

| domestication | fragrance | rice, soya bean | species/family | cereals and beyond | BADH2, GmBADH2 | metabolic enzyme | parallel | [29,30] |

| domestication | glutinous seeds | rice, wheat, maize, foxtail millet, barley, amaranth, sorghum, broom, maize millet | species/family/above family | cereals and beyond | GBSSI, waxy | metabolic enzyme | parallel | [31–36] |

| domestication | grain quality | maize | species | species-specific, cereals | Opaque2 | bZIP-TF | unknown | [37] |

| domestication | shatter resistance | sorghum, rice, maize | family | cereal-wide | Sh1, OsSh1, ZmSh1 | YABBY-like TF | parallel | [38] |

| both | coloration | pea, potato | above family | outside the cereals | flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase | metabolic enzyme | parallel | [37] |

| both | coloration | rice, potato | species/above family | cereals and beyond | Rd/DFR, DFR | metabolic enzyme | parallel | [39,40] |

| both | coloration | blood orange | species | species-specific, outside cereals | Ruby | MYB-TF | unknown | [41] |

| both | coloration | rice | species | species-specific, cereals | Bh4 | transporter protein | unknown | [42] |

| both | coloration | soya bean | species | species-specific, outside cereals | R | MYB-TF | unknown | [43] |

| both | coloration | rice | species | species-specific, cereals | Rc | bHLH-TF | unknown | [37] |

| both | coloration | grapevine | species | species-specific, outside cereals | VvMYBA1-3 | MYB-TF | unknown | [37] |

| both | flowering time | barley, pea, strawberry | above family | cereals and beyond | HvCEN, PsTFL1c, FvTFL1 | signalling protein | parallel | [44–46] |

| both | flowering time | rice, barley, pea, lentil | family/above family | cereals and beyond | Hd17, EAM8, Mat-a, HR, LcELF3 | Circadian clock | parallel | [47–50] |

| both | flowering time | rice, wheat, sunflower, barley | family/above family | cereals and beyond | Hd3a (Heading date 3a), VRN3/TaFT, HaFT1, HvFT | signalling protein | parallel | [51–53] |

| both | flowering time | sorghum, rice | family | cereal-wide | Ghd7, SbGhd7 | CCT domain protein | parallel | [54,55] |

| both | flowering time | turnip, Brassica oleracea | family | outside the cereals | BrFLC2, BoFLC2 | MADS domain TF | parallel | [56–58] |

| both | flowering time | barley, wheat, rye cereals | species/family | cereal-wide | VRN1, BM5, TmAP1, WAP1, LpVRN1 | MADS domain TF | parallel | [59] |

| both | flowering time | rice, barley, wheat, sorghum, sugar beet | species/family/above family | cereals and beyond | OsPRR37, Ppd-H1, Ppd1, SbPRR37, BvBTC1 | circadian clock | parallel | [60–65] |

| both | flowering time | rice | species | species-specific, cereals | Hd1 | zinc finger TF | unknown | [37] |

| both | flowering time | barley, wheat, maize | species/family | cereal-wide | VRN2, ZCCT1, ZmCCT9 | CCT domain protein | parallel | [66] |

| both | plant architecture | maize, pearl millet, barley | family | cereal-wide | tb1, Pgtb1, INT-C | TCP-TF | parallel | [67–69] |

| both | plant architecture | barley | species | species-specific, cereals | VRS1 | homeodomain-TF | unknown | [37] |

| adaptation | cold tolerance | barley, wheat | family | cereal-wide | HVA1, Wrab18, Wrab19 | LEA protein | parallel | [70,71] |

| adaptation | cold tolerance | wheat, barley | family | cereal-wide | Wcs19, Wcor14, Wcor15, Bcor14b | Cor protein | parallel | [72] |

| adaptation | drought tolerance | maize, Arabidopsis | above family | cereals and beyond | ZmVPP1, AVP1 | H(+) pyrophosphatase | parallel | [73] |

| adaptation | drought tolerance | rice | species | species-specific, cereals | OsAHL1 | AT-hook PPC domain | unknown | [74] |

| adaptation | metal tolerance | wheat, rye | family | cereal-wide | TaALMT1, ScALMT1 | transporter protein | parallel | [37] |

| adaptation | metal tolerance | sorghum, maize | family | cereal-wide | SbMATE1, ZmMATE1 | transporter protein | parallel | [37] |

| adaptation | pathogen resistance | wheat, rice, sorghum | family | cereal-wide | LR34 | ABC transporter | parallel | [75] |

| adaptation | pathogen resistance | maize | species | species-specific, cereals | Rp3 | NBS-LRR | unknown | [76] |

| adaptation | soil salinity | barley, maize, spinach | above family | cereals and beyond | HvPIP2;1, ZmPIP2-4, PM28A | Aquaporin | parallel | [77–79] |

| adaptation | soil salinity | rice, foxtail millet, tomato | above family | cereals and beyond | OsASR1, OsASR3, SiASR1, SlASR1 | ABA stress ASR protein | parallel | [80,81] |

(b). Post-domestication adaptation in the cereals

An adaptive trait is one that interacts or responds to the environment in a way that helps an organism to thrive. By this definition, adaptive traits can include (but are not limited to) flowering time, drought tolerance, cold tolerance, soil salinity and pathogen defense. For domesticated crops, however, adaptive traits that reverse desired domestication phenotypes such as yield, fragrance and reduced branching and shattering would not be considered favourable; therefore, we will narrow the definition of an adaptive trait to one that interacts or responds to the environment favourably but does not detract from desired domestication traits.

Perhaps it is also necessary to define what specifically is meant by ‘environment’. A straightforward (and admittedly simplistic) way would be to break ‘environment’ down to discrete features, which can include, for example, the level of carbon dioxide in the air, the level of UV radiation, temperature, day length, humidity, rainfall, wind, soil nutrient load and soil salinity. By dividing the environment into these discrete elements, we can address each element individually by asking what sort of adaptive trait we would expect to observe in response to each, how many of these adaptive traits are expressed in the same genetic pathways as known domestication genes and which represent entirely distinct physiological processes. Most cereal crops were domesticated within the latitudinal boundaries of the equator and 35 N [82,83], featuring both wet and dry seasons [82], which means, in relation to some aspects of the environment, they likely shared similar initial adaptation. Subsequent to domestication, cereals expanded to broad distributions, encountering new pathogens, cooler temperatures, distinct photoperiod, altered growing seasons and varied elevation. While much attention has been given to whether convergence in domestication traits occurred through parallel molecular means, far less is known about these processes during crop expansion and adaptation to novel habitats.

In cereal domestication, we have identified convergent domestication traits and shown examples of parallel convergence through shared functional orthology across species. Adaptation traits, too, are often convergent. One example is cold tolerance, which has been reported in a number of plant species, including wheat, barley and Arabidopsis (table 1). Other adaptive traits that are convergent across cereal taxa include drought tolerance, metal tolerance and soil salinity (table 1). However, the extent to which post-domestication convergent adaptation has occurred through parallel molecular means in the cereals is potentially impacted by demography and selection during domestication.

(c). Impacts of domestication bottlenecks on parallel adaptation in the cereals

Genome-wide loss of diversity during genetic bottlenecks associated with both initial domestication and later crop expansion may constrain adaptation by reducing the diversity in cereal crop populations. Substantial genome-wide loss of nucleotide diversity during domestication is reported in domesticated bread wheat [84], maize (with an increase in deleterious alleles) [8,85], rice [86], sorghum [87] and barley [88] compared with wild relatives, demonstrating that loss of diversity is widespread in cultivated grasses and is a phenomenon that is distinct from uncultivated wild relatives. Further reductions in nucleotide diversity are found near loci underlying domestication syndrome traits. It would seem that domestication itself is responsible for the loss of diversity and, because of this, attempts to adapt domesticated grasses to new environments could be constrained by recent demography. Both demographic bottlenecks and selection during domestication could affect the likelihood that adaptive traits were selected in parallel, since these depend on whether adaptive alleles are retained across taxa post-domestication. Nevertheless, the dynamic nature of cereal crop genomes may provide unique opportunities for cereals to escape from these constraints by facilitating conditions for parallel adaptation.

3. Predicting the likelihood of parallelism in post-domestication cereal adaptation

The likelihood that a convergent adaptive trait will be selected in parallel is summarized in figure 3. Here, we will focus primarily on our expectations for post-domestication parallel selection of adaptive traits in the cereals relative to (a) whether an adaptive gene is orthologous in other species; (b) whether an adaptive gene functions also as a domestication gene; (c) mutation rate; (d) mutational target size; and, finally, (e) how the dynamics of cereal crop genomes may uniquely influence some of these expectations.

Figure 3.

Likelihood that post-domestication adaptation would be parallel. (a,b) describes a simple representation of spike domestication in wheat (a) and maize (b). Alongside the domestication of each crop is the resulting bottleneck. After the domestication of both crops, any adaptation must result from a population with lower diversity in each crop species. The likelihood of parallel adaptation is compromised due to this lower diversity, but parallelism may still result if certain criteria are met (c). (Online version in colour.)

(a). Adaptive genes that have orthologues in other species

We have seen that an increasing number of causal genes for domestication traits have been characterized (table 1). Many of these characterized genes have orthologues in the cereals that have been selected in parallel. In table 1, we demonstrate cases where genes have been characterized that appear to confer adaptive traits. As discussed previously, some of these traits, such as cold, drought and metal tolerance, are convergent. Among these convergent adaptation traits, some appear to have been selected in parallel. For instance, ZmVPP1 in maize has been linked to drought tolerance [73]. More specifically, a transposon insertion upstream of ZmVPP1 confers the drought-tolerant trait. Since this gene has an orthologue also linked to drought tolerance in the divergent species Arabidopsis, AVP1 [89], this trait may have been selected in parallel in the cereals. Another example is the MATE1 gene, which has been selected for metal tolerance in maize [90]. MATE1 has an orthologue in sorghum (SbMATE1; table 1) and would be a promising candidate for parallel adaptation in the two species. Finally, another gene thought to confer adaptation is ZmCCT9 in maize, which appears to be involved in flowering under the long days of higher latitudes. More specifically, a transposon insertion upstream of ZmCCT9 in domesticated maize cultivars led to reduced photoperiod sensitivity, which has allowed domesticated maize to expand its range [66]. This gene has orthologues in barley and wheat (Column 3, table 1); therefore, there is the potential that the orthologue exists in other cereal crops as well (where it has yet to be characterized).

Table 1 has some examples of orthologous genes that confer adaptive traits that might be investigated for parallel selection across the cereals. For example, wheat and barley share a small family of cold-tolerance genes including Wcs19 [91], Wcor14 [92] and Bcor14b [93], all of which encode chloroplast-targeted COR proteins analogous to the Arabidopsis protein COR15a [72,94]. The LEA protein orthologues HVA1 and Wrab 18/19 in barley and wheat, respectively, are also associated with cold tolerance [70,71]. Transcript and protein levels of the barley HvPIP2 aquaporin gene were found to be downregulated in roots but upregulated in the shoots of plants under salt stress [77]. HvPIP2 has an orthologue in both maize, ZmPIP2-4 [78] and spinach, PM28A [79]. There are also the ASR (abscisic acid, stress and ripening-induced) genes that are associated with salinity tolerance in rice [95], Setaria (millet) [80] and tomato [81].

However, other adaptive genes such as Rp3, which confers rust resistance in maize [76], do not appear to have a characterized orthologue in any other species at the time of this writing. While this orthologue may certainly exist undiscovered in other grasses, there are some adaptive traits, for example, those involved in pathogen resistance, that are less likely to have orthologues, even in closely related species. There are examples of shared orthologues for pathogen defense and stress response genes in the grasses (table 1), but by and large, genes that code for traits involved in plant defense and stress response are frequently orphan genes or genes that are specific to a particular lineage, sharing no defined orthologues with any outgroup ([96]; reviewed in [97]). Orphan genes tend to be very dynamic, arising and becoming lost much faster than their basal counterparts [98]. Orphan genes can arise via transposon exaptation [99] and propagate through trans duplication [97,98], including retrotransposition [100]. Therefore, movement of these genes to a new region whose local euchromatic status can confer novel expression patterns to the mobilized gene can be a strong source of adaptation, especially since it has been shown that stressful environments can stimulate activation of TEs ([101,102] reviewed in [103]). This is one way that cereal crops might be able to escape their legacy of reduced diversity owing to domestication in order to adapt. If a convergent adaptive trait such as pathogen resistance is dependent on these orphan-type genes, which quite often are unique even in individual cultivars within the same crop species, then we would not expect to see parallel selection of this trait at the allelic level in cereal adaptation, since each species—indeed, each cultivar—would be expected to have its own unique, ”outward-facing” suite of orphan genes that would confer environmental adaptation uniquely to its niche.

(b). Domestication genes that have adaptive components

A gene involved in domestication may be less likely to be selected during adaptation if the adaptive function reverses the domestication phenotype. Therefore, it is useful to define genes that are known to function as domestication genes versus those that have been characterized as adaptive (Column 1, table 1). There are a number of adaptive traits described previously, such as drought tolerance, cold tolerance, soil salinity and pathogen defense, that are unlikely to have a domestication component, since they appear unrelated to previously described domestication syndrome traits. Some of these adaptive traits have characterized genes described in table 1. However, there are genes described in table 1 that can be potentially associated with both domestication and adaptation. For example, the Ghd7 gene in rice has been associated with domestication traits such as grains per panicle; however, natural variants with reduced function allow rice to be cultivated in cooler regions [54], which is an adaptive phenotype. Another example of a domestication trait with an adaptive component is pigmentation. Loss of pigmentation has been favoured in a variety of cereal cultivars as a cultural preference during domestication. Yet pigment assists with UV tolerance in cereals and other plant species, particularly at high elevation [104,105]. Therefore, pigmentation could lead to greater tolerance of UV radiation in cereals colonizing high elevation post-domestication [106]. At least, under the criterion of shared orthology, parallel convergence of this trait is possible in the cereals. Genes targeted during domestication do not appear to be entirely unassociated with adaptation, suggesting that either standing adaptive variation has survived the domestication bottleneck and selection or mutational processes have introduced adaptive alleles post-domestication.

(c). Mutation rate

The limitation imposed by the domestication in cereal crops may, to some extent, be reversed owing to their dynamic genomes, particularly their high transposon activity relative to other crop species. We have seen that grasses tend to have relatively active transposons and this transposon activity may permit a higher mutation rate in cereals [16]. In table 1, several adaptive phenotypes are owing to a transposon insertion somewhere in the functional region of a gene, such as ZmCCT9 and ZmVVP1 in maize. However, a comprehensive review of TEs and plant evolution [107] suggests that our understanding of the role of TE activity in crop adaptation is largely anecdotal and might be overstated, but perhaps can be better elucidated by harnessing the recent advances in genomics such as more sophisticated TE annotation protocols, whole-genome sequencing and comparative algorithms. Using these advances in genome biology, a recent study by Lai and coworkers found that transposon insertions may have played an important part in creating the variation in gene regulation that enabled the rapid adaptation of domesticated maize to diverse environments [108].

(d). Mutational target size

Transposable elements may also result in meaningful differences in genome size across cereal crops. Transposons are known to contribute to the expansion of genome size in maize and other plant species ([109], reviewed in [107]). A recent review [110] suggests that larger genomes may affect the process of adaptation by increasing the number and location of potentially functional mutations, thus expanding the regulatory space in which functional mutations may arise. This may increase the likelihood that a given orthologous gene or pathway could be selected in parallel for adaptive traits, despite losses of diversity experienced during domestication. In this way, cereal grasses may be more poised than other crop species to reverse the effects of their domestication bottlenecks and increase the chances of parallel adaptation, owing to their high rates of transposon activity.

(e). Considerations for cereal polyploids

For a subset of cereals (e.g. maize and wheat) that have undergone recent polyploidy [111,112], whole-genome duplication events (figure 2) can result in homeologs that may undergo subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization and give rise to adaptive loci. To some extent, it can be predicted which homeolog in a post-polyploid cereal is likely to be adaptive. It is known that of the two retained post-polyploidy subgenomes in maize, one undergoes less fractionation and is more highly expressed than the other (i.e. the dominant subgenome) [113,114], and there is evidence that fractionation is biased not only in maize but in wheat as well [115]. Schnable & Freeling found that of the characterized genes that have a known mutant phenotype, the majority are on the less fractionated subgenome [116]. Many of these genes, such as tb1, Waxy, Opaque2 and several starch synthesis and coloration genes not in table 1, have a domestication syndrome phenotype in maize. Additionally, recent work has suggested that the genes on the more highly expressed subgenome in maize contribute more to phenotypic variation than the less expressed subgenome across a wide variety of traits, including those linked to adaptation [117]. Indeed, two genes associated with adaptive phenotypes in maize from table 1, ZmVPP1 (drought tolerance) and ZmPIP2-4 (soil salinity) are both found on the less fractionated subgenome [116]; and genes associated with adaptation phenotypes such as disease resistance have also been observed on the more dominant subgenome in [117]. Parallelism in recent polyploids with other species, therefore, may be more likely within the more dominant subgenome.

4. Conclusion

This review set out to explore the extent of convergence and molecular parallelism in domestication syndrome traits in cereals. We have also considered how domestication has influenced the potential for subsequent parallel adaptation in the grasses during expansion to novel habitats. Demographic bottlenecks and targeted selection during domestication have removed potentially adaptive variation that may, in turn, reduce the extent of parallelism observed during adaptation. We hypothesized that parallelism in adaptation in cereal crops is affected by: (a) whether an adaptive gene is orthologous across taxa; (b) whether an adaptive trait is related to the domestication syndrome; (c) the mutation rate in cereals, particularly as influenced by transposable elements; (d) the mutation target size; and (e) particular dynamics of cereal genomes such as recent polyploidy. As demonstrated in table 1, the causal loci underlying adaptation in the grasses are just beginning to be discovered. Comparative genomic analyses of cereals and their wild relatives combined with comparative studies of uniquely adapted populations will help identify genes involved in these processes and further characterize whether selection occurred in parallel. The genomic study of time-stratified archaeological samples may also help clarify the timing of selection and the extent to which parallelism in adaptation is conditioned on initial selection during domestication. Crops in the grass family have been very successful in adapting to a wide range of environmental conditions, in some documented cases in parallel, despite limitations in adaptive potential owing to domestication, perhaps owing to their dynamic, large genomes. Other crop species with, for example, fewer TEs, may fail to overcome the limitations on adaptive potential introduced by demographic bottlenecks and selection during domestication. In addition to enhancing our basic understanding of the repeatability of evolution, an understanding of convergence and parallelism is useful if we wish to breed wild grass relatives for adaptive traits or create hybrids among existing cultivars, since we can now associate favourable phenotypes and quantitative trait loci with orthologues across species by simple comparative genomics. We therefore predict that a clear understanding of parallel adaptation within crop species will enhance and assist modern breeding.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

M.B.H. devised the theme and general concepts of domestication, adaptation and parallelism. M.R.W. devised the sections relating to grass genome plasticity, orthology and orphan genes. M.R.W. and M.B.H. contributed equally to the drafting and the editing of the article.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by USDAgrant no. USDA-ARS 58-5030-7-072.

References

- 1.Doebley JF, Gaut BS, Smith BD. 2006. The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127, 1309–1321. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer K. 1984. Das domestikationssyndrom. Die Kulturpflanze 32, 11–34. ( 10.1007/BF02098682) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang C-C, Chen H-L, Li W-H, Chaw S-M. 2004. Dating the monocot–dicot divergence and the origin of core eudicots using whole chloroplast genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 58, 424–441. ( 10.1007/s00239-003-2564-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong Y, Wang Y-Z. 2015. Seed shattering: from models to crops. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 476 ( 10.3389/fpls.2015.00476) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblum EB, Parent CE, Brandt EE. 2014. The molecular basis of phenotypic convergence. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 203–226. ( 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091851) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickersgill B. 2018. Parallel vs. convergent evolution in domestication and diversification of crops in the Americas. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, 56 ( 10.3389/fevo.2018.00056) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washburn JD, Bird KA, Conant GC, Pires JC. 2016. Convergent evolution and the origin of complex phenotypes in the age of systems biology. Int. J. Plant Sci. 177, 305–318. ( 10.1086/686009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Beissinger TM, Lorant A, Ross-Ibarra C, Ross-Ibarra J, Hufford MB. 2017. The interplay of demography and selection during maize domestication and expansion. Genome Biol. 18, 215 ( 10.1186/s13059-017-1346-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin SB, Cohen BA, Fry WE. 1994. Panglobal distribution of a single clonal lineage of the Irish potato famine fungus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11 591–11 595. ( 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11591) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennetzen JL, Freeling M. 1993. Grasses as a single genetic system: genome composition, collinearity and compatibility. Trends Genet. 9, 259–261. ( 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90001-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeling M. 2001. Grasses as a single genetic system: reassessment 2001. Plant Physiol. 125, 1191–1197. ( 10.1104/pp.125.3.1191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchenak-Khelladi Y, Anthony-Verboom G, Savolainen V, Hodkinson TR. 2010. Biogeography of the grasses (Poaceae): a phylogenetic approach to reveal evolutionary history in geographical space and geological time. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 162, 543–557. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2010.01041.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellogg EA. 2001. Evolutionary history of the grasses. Plant Physiol. 125, 1198–1205. ( 10.1104/pp.125.3.1198) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Chapman BA. 2004. Ancient polyploidization predating divergence of the cereals, and its consequences for comparative genomics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9903–9908. ( 10.1073/pnas.0307901101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy AA. 2002. The impact of polyploidy on grass genome evolution. Plant Physiol. 130, 1587–1593. ( 10.1104/pp.015727) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wicker T. et al. 2016. DNA transposon activity is associated with increased mutation rates in genes of rice and other grasses. Nat. Commun. 7, 12790 ( 10.1038/ncomms12790) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lisch DR. 2001. Mutator transposase is widespread in the grasses. Plant Physiol. 125, 1293–1303. ( 10.1104/pp.125.3.1293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenser T, Theißen G. 2013. Molecular mechanisms involved in convergent crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 704–714. ( 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.08.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer RS, Purugganan MD. 2013. Evolution of crop species: genetics of domestication and diversification. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 840–852. ( 10.1038/nrg3605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repinski SL, Kwak M, Gepts P. 2012. The common bean growth habit gene PvTFL1y is a functional homolog of Arabidopsis TFL1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124, 1539–1547. ( 10.1007/s00122-012-1808-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B. et al. 2010. The soybean stem growth habit gene dt1 is an ortholog of arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER1. Plant Physiol. 153, 198–210. ( 10.1104/pp.109.150607) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwak M, Toro O, Debouck DG, Gepts P. 2012. Multiple origins of the determinate growth habit in domesticated common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Ann. Bot. 110, 1573–1580. ( 10.1093/aob/mcs207) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian Z, Wang X, Lee R, Li Y, Specht JE, Nelson RL, McClean PE, Qiu L, Ma J. 2010. Artificial selection for determinate growth habit in soybean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8563–8568. ( 10.1073/pnas.1000088107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asano K, Takashi T, Miura K, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Ashikari M. 2007. Genetic and molecular analysis of utility of sd1 alleles in rice breeding. Breed. Sci. 57, 53–58. ( 10.1270/jsbbs.57.53) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asano K. et al. 2011. Artificial selection for a green revolution gene during japonica rice domestication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11 034–11 039. ( 10.1073/pnas.1019490108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia Q, Zhang J, Westcott S, Zhang X-Q, Bellgard M, Lance R, Li C. 2009. GA-20 oxidase as a candidate for the semidwarf gene sdw1/denso in barley. Funct. Integr. Genomics 9, 255–262. ( 10.1007/s10142-009-0120-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Multani DS. 2003. Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants. Science 302, 81–84. ( 10.1126/science.1086072) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parvathaneni RK, Jakkula V, Padi FK, Faure S, Nagarajappa N, Pontaroli AC, Wu X, Bennetzen JL, Devos KM. 2013. Fine-mapping and identification of a candidate gene underlying the d2 dwarfing phenotype in pearl millet, Cenchrus americanus (l.) Morrone. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 3, 563–572. ( 10.1534/g3.113.005587) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovach MJ, Calingacion MN, Fitzgerald MA, McCouch SR. 2009. The origin and evolution of fragrance in rice (Oryza sativa). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14 444–14 449. ( 10.1073/pnas.0904077106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juwattanasomran R, Somta P, Chankaew S, Shimizu T, Wongpornchai S, Kaga A, Srinives P. 2010. A SNP in GmBADH2 gene associates with fragrance in vegetable soybean variety kaori and SNAP marker development for the fragrance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 533–541. ( 10.1007/s00122-010-1467-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeon J-S, Ryoo N, Hahn T-R, Walia H, Nakamura Y. 2010. Starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperm. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 383–392. ( 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.03.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan L, Quan L, Leng X, Guo X, Hu W, Ruan S, Ma H, Zeng M. 2008. Molecular evidence for post-domestication selection in the Waxy gene of Chinese waxy maize. Mol. Breed. 22, 329–338. ( 10.1007/s11032-008-9178-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawahigashi H, Oshima M, Nishikawa T, Okuizumi H, Kasuga S, Yonemaru JI. 2013. A novel waxy allele in sorghum Landraces in East Asia. Plant Breed. 132, 305–310. ( 10.1111/pbr.2013.132.issue-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawase M, Fukunaga K, Kato K. 2005. Diverse origins of waxy foxtail millet crops in East and Southeast Asia mediated by multiple transposable element insertions. Mol. Genet. Genomics 274, 131–140. ( 10.1007/s00438-005-0013-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt HV, Moots HM, Graybosch RA, Jones H, Parker M, Romanova O, Jones MK, Howe CJ, Trafford K. 2012. Waxy phenotype evolution in the allotetraploid cereal broomcorn millet: mutations at the GBSSI locus in their functional and phylogenetic context. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 109–122. ( 10.1093/molbev/mss209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park Y-J, Nishikawa T, Tomooka N, Nemoto K. 2011. The molecular basis of mutations at the Waxy locus from Amaranthus caudatus l.: evolution of the waxy phenotype in three species of grain amaranth. Mol. Breed. 30, 511–520. ( 10.1007/s11032-011-9640-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin A, Orgogozo V. 2013. The loci of repeated evolution: a catalog of genetic hotspots of phenotypic variation. Evolution 67, 1235–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Z. et al. 2012. Parallel domestication of the Shattering1 genes in cereals. Nat. Genet. 44, 720–724. ( 10.1038/ng.2281) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furukawa T, Maekawa M, Oki T, Suda I, Iida S, Shimada H, Takamure I, Kadowaki KI. 2006. The Rc and Rd genes are involved in Proanthocyanidin synthesis in rice pericarp. Plant J. 49, 91–102. ( 10.1111/tpj.2007.49.issue-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Cheng S, Jong DD, Griffiths H, Halitschke R, Jong WD. 2009. The potato R locus codes for dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 931–937. ( 10.1007/s00122-009-1100-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butelli E, Licciardello C, Zhang Y, Liu J, Mackay S, Bailey P, Reforgiato-Recupero G, Martin C. 2012. Retrotransposons control fruit-specific, cold-dependent accumulation of anthocyanins in blood oranges. Plant Cell 24, 1242–1255. ( 10.1105/tpc.111.095232) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu B-F, et al. 2011. Genetic control of a transition from black to straw-white seed hull in rice domestication. Plant Physiol. 155, 1301–1311. ( 10.1104/pp.110.168500) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gillman JD, Tetlow A, Lee J-D, Shannon J, Bilyeu K. 2011. Loss-of-function mutations affecting a specific glycine max r2r3 MYB transcription factor result in brown hilum and brown seed coats. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 155 ( 10.1186/1471-2229-11-155) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Comadran J, et al. 2012. Natural variation in a homolog of antirrhinum CENTRORADIALIS contributed to spring growth habit and environmental adaptation in cultivated barley. Nat. Genet. 44, 1388–1392. ( 10.1038/ng.2447) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foucher F. 2003. DETERMINATE and LATE FLOWERING are two TERMINAL FLOWER1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs that control two distinct phases of flowering initiation and development in pea. Plant Cell Online 15, 2742–2754. ( 10.1105/tpc.015701) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koskela EA, et al. 2012. Mutation in TERMINAL FLOWER1 reverses the photoperiodic requirement for flowering in the wild strawberry Fragaria vesca. Plant Physiol. 159, 1043–1054. ( 10.1104/pp.112.196659) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weller JL, et al. 2012. A conserved molecular basis for photoperiod adaptation in two temperate legumes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 21 158–21 163. ( 10.1073/pnas.1207943110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsubara K, Ogiso-Tanaka E, Hori K, Ebana K, Ando T, Yano M. 2012. Natural variation in Hd17, a homolog of Arabidopsis ELF3 that is involved in rice photoperiodic flowering. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 709–716. ( 10.1093/pcp/pcs028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zakhrabekova S, et al. 2012. Induced mutations in circadian clock regulator Mat-a facilitated short-season adaptation and range extension in cultivated barley. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4326–4331. ( 10.1073/pnas.1113009109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faure S, Turner AS, Gruszka D, Christodoulou V, Davis SJ, von Korff M, Laurie DA. 2012. Mutation at the circadian clock gene EARLY MATURITY 8 adapts domesticated barley (Hordeum vulgare) to short growing seasons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8328–8333. ( 10.1073/pnas.1120496109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan L. et al. 2006. The wheat and barley vernalization gene VRN3 is an orthologue of FT. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19 581–19 586. ( 10.1073/pnas.0607142103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi Y, Teshima KM, Yokoi S, Innan H, Shimamoto K. 2009. Variations in Hd1 proteins, Hd3a promoters, and Ehd1 expression levels contribute to diversity of flowering time in cultivated rice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4555–4560. ( 10.1073/pnas.0812092106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blackman BK, Strasburg JL, Raduski AR, Michaels SD, Rieseberg LH. 2010. The role of recently derived FT paralogs in sunflower domestication. Curr. Biol. 20, 629–635. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xue W. et al. 2008. Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat. Genet. 40, 761–767. ( 10.1038/ng.143) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy RL, Morishige DT, Brady JA, Rooney WL, Yang S, Klein PE, Mullet JE. 2014. Ghd7 (Ma6) represses sorghum flowering in long days: Ghd7 alleles enhance biomass accumulation and grain production. Plant Genome 7, 0040 ( 10.3835/plantgenome2013.11.0040) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J, Wei K, Cheng F, Li S, Wang Q, Zhao J, Bonnema G, Wang X. 2012. A naturally occurring InDel variation in BraA.FLC.b (BrFLC2) associated with flowering time variation in Brassica rapa. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 151 ( 10.1186/1471-2229-12-151) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuan Y-X, Wu J, Sun R-F, Zhang X-W, Xu D-H, Bonnema G, Wang X-W. 2009. A naturally occurring splicing site mutation in the Brassica rapa FLC1 gene is associated with variation in flowering time. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1299–1308. ( 10.1093/jxb/erp010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okazaki K, Sakamoto K, Kikuchi R, Saito A, Togashi E, Kuginuki Y, Matsumoto S, Hirai M. 2006. Mapping and characterization of FLC homologs and QTL analysis of flowering time in Brassica oleracea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 595–608. ( 10.1007/s00122-006-0460-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asp T. et al. 2011. Comparative sequence analysis of VRN1 alleles of Lolium perenne with the co-linear regions in barley, wheat, and rice. Mol. Genet. Genomics 286, 433–447. ( 10.1007/s00438-011-0654-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murakami M, Matsushika A, Ashikari M, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. 2005. Circadian-associated rice pseudo response regulators (OsPRRs): insight into the control of flowering time. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 410–414. ( 10.1271/bbb.69.410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turner A. 2005. The pseudo-response regulator ppd-h1 provides adaptation to photoperiod in barley. Science 310, 1031–1034. ( 10.1126/science.1117619) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones H. et al. 2008. Population-based resequencing reveals that the flowering time adaptation of cultivated barley originated east of the fertile crescent. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 2211–2219. ( 10.1093/molbev/msn167) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beales J, Turner A, Griffiths S, Snape JW, Laurie DA. 2007. A pseudo-response regulator is misexpressed in the photoperiod insensitive Ppd-D1a mutant of wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 115, 721–733. ( 10.1007/s00122-007-0603-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilhelm EP, Turner AS, Laurie DA. 2008. Photoperiod insensitive Ppd-A1a mutations in tetraploid wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 285–294. ( 10.1007/s00122-008-0898-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Díaz A, Zikhali M, Turner AS, Isaac P, Laurie DA. 2012. Copy number variation affecting the Photoperiod-B1 and Vernalization-A1 genes is associated with altered flowering time in wheat (Triticum aestivum). PLoS ONE 7, e33234 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0033234) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang C. et al. 2017. ZmCCT9 enhances maize adaptation to higher latitudes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E334–E341. ( 10.1073/pnas.1718058115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Studer A, Zhao Q, Ross-Ibarra J, Doebley J. 2011. Identification of a functional transposon insertion in the maize domestication gene tb1. Nat. Genet. 43, 1160–1163. ( 10.1038/ng.942) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Remigereau M-S, Lakis G, Rekima S, Leveugle M, Fontaine MC, Langin T, Sarr A, Robert T. 2011. Cereal domestication and evolution of branching: evidence for soft selection in the Tb1 orthologue of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum [L.] r. br.). PLoS ONE 6, e22404 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0022404) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramsay L. et al. 2011. INTERMEDIUM-c, a modifier of lateral spikelet fertility in barley, is an ortholog of the maize domestication gene TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1. Nat. Genet. 43, 169–172. ( 10.1038/ng.745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hong B, Uknes SJ, David Ho T-H. 1988. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a mRNA rapidly-induced by ABA in barley aleurone layers. Plant Mol. Biol. 11, 495–506. ( 10.1007/BF00039030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Egawa C, Kobayashi F, Ishibashi M, Nakamura T, Nakamura C, Takumi S. 2006. Differential regulation of transcript accumulation and alternative splicing of a DREB2 homolog under abiotic stress conditions in common wheat. Genes Genet. Syst. 81, 77–91. ( 10.1266/ggs.81.77) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takumi S. 2003. Cold-specific and light-stimulated expression of a wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Cor gene Wcor15 encoding a chloroplast-targeted protein. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 2265–2274. ( 10.1093/jxb/erg247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X, Wang H, Liu S, Ferjani A, Li J, Yan J, Yang X, Qin F. 2016. Genetic variation in ZmVPP1 contributes to drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat. Genet. 48, 1233–1241. ( 10.1038/ng.3636) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou L. et al. 2016. A novel gene OsAHL1 improves both drought avoidance and drought tolerance in rice. Sci. Rep. 6, 30264 ( 10.1038/srep30264) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krattinger SG, Lagudah ES, Wicker T, Risk JM, Ashton AR, Selter LL, Matsumoto T, Keller B. 2010. Lr34 multi-pathogen resistance ABC transporter: molecular analysis of homeologous and orthologous genes in hexaploid wheat and other grass species. Plant J. 65, 392–403. ( 10.1111/tpj.2011.65.issue-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Webb CA, Richter TE, Collins NC, Nicolas M, Trick HN, Pryor T, Hulbert SH. 2002. Genetic and molecular characterization of the maize rp3 rust resistance locus. Genetics 162, 381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katsuhara M, Akiyama Y, Koshio K, Shibasaka M, Kasamo K. 2002. Functional analysis of water channels in barley roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 885–893. ( 10.1093/pcp/pcf102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhu C, Schraut D, Hartung W, Schäffner AR. 2005. Differential responses of maize MIP genes to salt stress and ABA. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2971–2981. ( 10.1093/jxb/eri294) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fotiadis D, Jenö P, Mini T, Wirtz S, Müller SA, Fraysse L, Kjellbom P, Engel A. 2000. Structural characterization of two aquaporins isolated from native spinach leaf plasma membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1707–1714. ( 10.1074/jbc.M009383200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li J, Dong Y, Li C, Pan Y, Yu J. 2017. SiASR4, the target gene of SiARDP from Setaria italica, improves abiotic stress adaption in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 02053 ( 10.3389/fpls.2016.02053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Konrad Z, Bar-Zvi D. 2008. Synergism between the chaperone-like activity of the stress regulated ASR1 protein and the osmolyte glycine-betaine. Planta 227, 1213–1219. ( 10.1007/s00425-008-0693-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harlan JR. 1992. Crops and man, 2nd edn. Madison, WI: American Society for Agronomy. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gepts P. 2010. Crop domestication as a long-term selection experiment. In Plant breeding reviews (ed. J Janick), pp. 1–44. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haudry A. et al. 2007. Grinding up wheat: a massive loss of nucleotide diversity since domestication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1506–1517. ( 10.1093/molbev/msm077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eyre-Walker A, Gaut RL, Hilton H, Feldman DL, Gaut BS. 1998. Investigation of the bottleneck leading to the domestication of maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4441–4446. ( 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4441) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu Q, Zheng X, Luo J, Gaut BS, Ge S. 2007. Multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation of Oryza sativa and its wild relatives: severe bottleneck during domestication of rice. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 875–888. ( 10.1093/molbev/msm005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hamblin MT. 2006. Challenges of detecting directional selection after a bottleneck: lessons from Sorghum bicolor. Genetics 173, 953–964. ( 10.1534/genetics.105.054312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kilian B. et al. 2006. Haplotype structure at seven barley genes: relevance to gene pool bottlenecks, phylogeny of ear type and site of barley domestication. Mol. Genet. Genomics 276, 230–241. ( 10.1007/s00438-006-0136-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gaxiola RA, Li J, Undurraga S, Dang LM, Allen GJ, Alper SL, Fink GR. 2001. Drought- and salt-tolerant plants result from overexpression of the AVP1 H+-pump. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11 444–11 449. ( 10.1073/pnas.191389398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maron LG. et al. 2013. Aluminum tolerance in maize is associated with higher MATE1 gene copy number. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5241–5246. ( 10.1073/pnas.1220766110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chauvin LP, Houde M, Sarhan F. 1993. A leaf-specific gene stimulated by light during wheat acclimation to low temperature. Plant Mol. Biol. 23, 255–265. ( 10.1007/BF00029002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tsvetanov S, Ohno R, Tsuda K, Takumi S, Mori N, Atanassov A, Nakamura C. 2000. A cold-responsive wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) gene wcor14 identified in a winter-hardy cultivar ’Mironovska 808’. Genes Genet. Syst. 75, 49–57. ( 10.1266/ggs.75.49) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crosatti C, Polverino de Laureto P, Bassi R, Cattivelli L. 1999. The interaction between cold and light controls the expression of the cold-regulated barley gene cor14b and the accumulation of the corresponding protein. Plant Physiol. 119, 671–680. ( 10.1104/pp.119.2.671) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Steponkus PL, Uemura M, Joseph RA, Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF. 1998. Mode of action of the COR15a gene on the freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14 570–14 575. ( 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14570) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Joo J, Lee YH, Kim Y-K, Nahm BH, Song SI. 2013. Abiotic stress responsive rice ASR1 and ASR3 exhibit different tissue-dependent sugar and hormone-sensitivities. Mol. Cells 35, 421–435. ( 10.1007/s10059-013-0036-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woodhouse MR, Tang H, Freeling M. 2011. Different gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana transposed in different epochs and at different frequencies throughout the rosids. Plant Cell 23, 4241–4253. ( 10.1105/tpc.111.093567) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arendsee ZW, Li L, Wurtele ES. 2014. Coming of age: orphan genes in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 698–708. ( 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.07.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Freeling M, Lyons E, Pedersen B, Alam M, Ming R, Lisch D. 2008. Many or most genes in Arabidopsis transposed after the origin of the order Brassicales. Genome Res. 18, 1924–1937. ( 10.1101/gr.081026.108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Donoghue MTA, Keshavaiah C, Swamidatta SH, Spillane C. 2011. Evolutionary origins of Brassicaceae specific genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 47 ( 10.1186/1471-2148-11-47) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang W. 2006. High rate of chimeric gene origination by retroposition in plant genomes. Plant Cell Online 18, 1791–1802. ( 10.1105/tpc.106.041905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beguiristain T. 2001. Three tnt1 subfamilies show different stress-associated patterns of expression in tobacco. Consequences for retrotransposon control and evolution in plants. Plant Physiol. 127, 212–221. ( 10.1104/pp.127.1.212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Makarevitch I, Waters AJ, West PT, Stitzer M, Hirsch CN, Ross-Ibarra J, Springer NM. 2015. Transposable elements contribute to activation of maize genes in response to abiotic stress. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004915 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004915) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Negi P, Rai AN, Suprasanna P. 2016. Moving through the stressed genome: emerging regulatory roles for transposons in plant stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1448 ( 10.3389/fpls.2016.01448) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stapleton AE, Walbot V. 1994. Flavonoids can protect maize DNA from the induction of ultraviolet radiation damage. Plant Physiol. 105, 881–889. ( 10.1104/pp.105.3.881) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gould KS. 2004. Nature’s Swiss army knife: the diverse protective roles of anthocyanins in leaves. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2004, 314–320. ( 10.1155/S1110724304406147) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pyhäjärvi T, Hufford MB, Mezmouk S, Ross-Ibarra J. 2013. Complex patterns of local adaptation in Teosinte. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 1594–1609. ( 10.1093/gbe/evt109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lisch D. 2013. How important are transposons for plant evolution? Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 49–61. ( 10.1038/nrg3374) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lai X. et al. 2017. Genome-wide characterization of non-reference transposable element insertion polymorphisms reveals genetic diversity in tropical and temperate maize. BMC Genomics 18, 702 ( 10.1186/s12864-017-4103-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tenaillon MI, Hufford MB, Gaut BS, Ross-Ibarra J. 2011. Genome size and transposable element content as determined by high-throughput sequencing in maize and zea luxurians. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 219–229. ( 10.1093/gbe/evr008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mei W, Stetter MG, Gates DJ, Stitzer MC, Ross-Ibarra J. 2018. Adaptation in plant genomes: bigger is different. Am. J. Bot. 105, 16–19. ( 10.1002/ajb2.1002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hughes TE, Langdale JA, Kelly S. 2014. The impact of widespread regulatory neofunctionalization on homeolog gene evolution following whole-genome duplication in maize. Genome Res. 24, 1348–1355. ( 10.1101/gr.172684.114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pfeifer M, Kugler KG, Sandve SR, Zhan B, Rudi H, Hvidsten TR, Mayer KFX, Olsen O-A. 2014. Genome interplay in the grain transcriptome of hexaploid bread wheat. Science 345, 1250091 ( 10.1126/science.1250091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Woodhouse MR, Schnable JC, Pedersen BS, Lyons E, Lisch D, Subramaniam S, Freeling M. 2010. Following tetraploidy in maize, a short deletion mechanism removed genes preferentially from one of the two homeologs. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000409 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000409) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schnable JC, Springer NM, Freeling M. 2011. Differentiation of the maize subgenomes by genome dominance and both ancient and ongoing gene loss. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4069–4074. ( 10.1073/pnas.1101368108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eckardtv NA. 2014. Genome dominance and interaction at the gene expression level in allohexaploid wheat. Plant Cell 26, 1834–1834. ( 10.1105/tpc.114.127183) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schnable JC, Freeling M. 2011. Genes identified by visible mutant phenotypes show increased bias toward one of two subgenomes of maize. PLoS ONE 6, e17855 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0017855) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Renny-Byfield S, Rodgers-Melnick E, Ross-Ibarra J. 2017. Gene fractionation and function in the ancient subgenomes of maize. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1825–1832. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx121) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.