Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Children with advanced cancer experience high symptom distress, which negatively impacts their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). To the authors’ knowledge, the relationship between income and symptom distress and HRQOL is not well described.

METHODS:

The Pediatric Quality of Life and Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) multisite clinical trial evaluated an electronic patient-reported outcome system to describe symptom distress and HRQOL in children with advanced cancer via repeated surveys. The authors performed a secondary analysis of PediQUEST data for those children with available parent-reported household income (dichotomized at 200% of the Federal Poverty Level and categorized as low income [<$50,000/year] or high income [≥$50,000/year]). The prevalence of the 5 most commonly reported physical and psychological symptoms was compared between groups. Multivariable generalized estimating equation models were used to test the association between household income and symptom distress and HRQOL.

RESULTS:

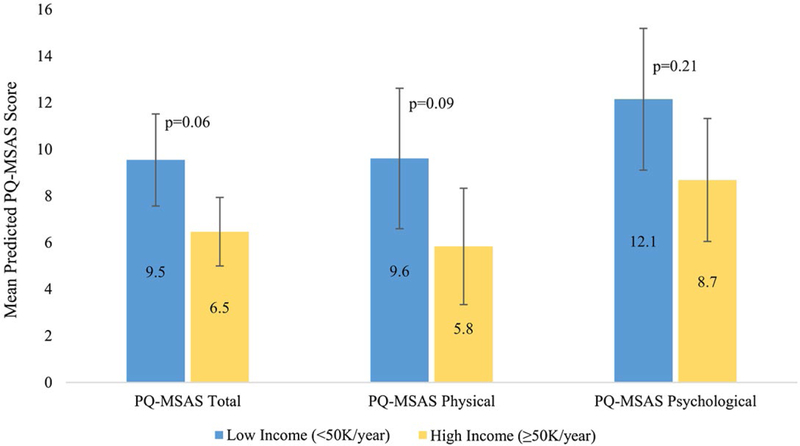

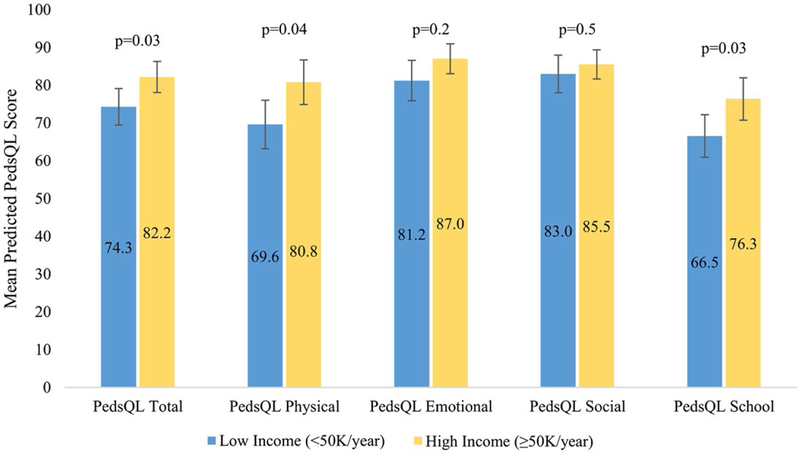

A total of 78 children were included in the analyses: 56 (72%) in the high-income group and 22 (28%) in the low-income group. Low-income children were more likely to report pain than high-income children (64% vs 42%; P=.02). In multivariable models, children from low-income families demonstrated a uniform trend toward higher total (βlow-high=3.1; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −0.08 to 6.2 [P=.06]), physical (β=3.8; 95% CI, −0.4 to 8.0 [P=.09]), and psychological (β=3.46; 95% CI, −1.91 to 8.84 [P=.21]) symptom distress compared with children from high-income families. Low income was associated with a uniform trend toward lower total (β=−7.9; 95% CI, −14.8, to −1.1 [P=.03]), physical (β=−11.2; 95% CI, −21.2 to −1.2 [P=.04]), emotional (β=−5.8; 95% CI, −13.6 to 2.0 [P=.15]), social (β=−2.52; 95% CI, −9.27 to 4.24 [P=.47]), and school (β=−9.8; 95% CI, −17.8 to −1.8 [P=.03]) HRQOL.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this cohort of children with advanced cancer, children from low-income families were found to experience higher symptom burden and worse QOL.

Keywords: disparity in symptom burden, patient-reported outcomes, pediatric advanced cancer, pediatric palliative care, Pediatric Quality of Life and Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST)

Precis

The authors performed a secondary analysis of data collected during the Pediatric Quality of Life and Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) multisite clinic trial. In this cohort of children with advanced cancer, low-income status was associated with increased symptom distress and worse quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Children with advanced cancer experience high symptom burden related to their underlying cancer and/or its treatments.1 This symptom burden affects parental decision making regarding goals of care as well as further treatment.2 Poverty is an established predictor of inferior health outcomes in children, including those with special health care needs. Children from low-income families have inferior asthma control,3 inferior glycemic control in those with type I diabetes mellitus,4 and increased mortality in those with cystic fibrosis.5 However, to the best of our knowledge, very little is known regarding the impact of socioeconomic status on health outcomes in children with cancer.

Prior studies in adults with cancer have demonstrated that patients who are racial or ethnic minorities and those living in poverty experience higher symptom distress than their counterparts.6–8 Provider symptom management differs based on race and income,6,9 as does patient-perceived unmet need for supportive care in adult patients with cancer.10 Furthermore, well-documented differences in the quality of communication between physicians and adult patients who are economically disadvantaged or of minority race11 suggest that uncontrolled symptoms may go unrecognized and unaddressed.

Data regarding disparities in symptom distress and management in pediatric patients with cancer are much more limited. A growing body of literature suggests that a child’s chance of cure may differ based on race or income. For example, children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who reside in low-income neighborhoods are at a greater risk of early disease recurrence compared with those from high-income neighborhoods.12 Minority children are more likely to be nonadherent to 6-mercaptopurine during treatment of ALL, which is associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence.13 There also is preliminary evidence that children from low-income families undergoing treatment of standard-risk ALL experience inferior quality of life (QOL).14

The Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) study was developed to collect patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in children with advanced cancer to better elicit the child’s voice around symptom experiences. Prior PediQUEST publications demonstrated that children with advanced cancer experience high symptom distress,15 and that symptom distress is strongly associated with health-related QOL (HRQOL).16 These data suggest that more intensive symptom management may improve a child’s HRQOL, and that identifying children at highest risk of symptom distress might facilitate interventions.16 To our knowledge, the impact of socioeconomic status on a child’s symptom distress and HRQOL has not been previously explored. We aimed to address this gap by exploring the relationship between household income and symptom prevalence, distress, and HRQOL among children with advanced cancer who were enrolled on the PediQUEST study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PediQUEST multisite clinical trial aimed to evaluate an electronic PRO system to describe symptom distress and HRQOL in children aged ≥2 years with advanced cancer via repeated surveys. Detailed methods and results from PediQUEST have been published previously.15–17 At baseline, parents completed the sociodemographic Survey About Caring for Children With Cancer (SCCC), which included household income. For the current investigation, we conducted a secondary analysis of those patients with available household income data.

PediQUEST participants were recruited from 3 large pediatric cancer centers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Seattle Children’s Hospital) between December 2004 and June 2009. Participants were eligible for PediQUEST if they were aged ≥2 years; spoke English; and had at least a 2-week history of progressive, recurrent, or nonresponsive cancer, or had made a decision not to pursue cancer-directed therapy. Surveys were completed primarily at the clinic or ward at most once a week. Data regarding cancer-directed therapy, disease status, and other relevant clinical covariates were extracted from the medical record.

Household Income

Household income information was obtained via the SCCC, which was administered to parents at baseline. Parents were asked to report their total combined family income for the past 12 months. Response categories were <$5000, $5000 through $11,999, $12,000 through $15,999, $16,000 through $24,999, $25,000 through $34,999, $35,000 through $49,999, $50,0000 through $74,999, $75,000 through $99,999, ≥$100,000, “don’t know,” and “no response.” We dichotomized income at a cutpoint of $50,000, which was based on a median house-hold size of 4 for the cohort, corresponding to <200% of the Federal Poverty Level. Consistent with prior pediatrics literature, we defined low income a priori as <200% of the Federal Poverty Level.18,19

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Symptom prevalence and distress were ascertained via the PediQUEST Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (PQ-MSAS).15 The PQ-MSAS measures the frequency, severity, and extent of bother for 24 symptoms; we a priori selected the 5 most commonly reported physical and psychological symptoms to compare prevalence. HRQOL was assessed via the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL).20 As previously published, validated age-appropriate PQ-MSAS and PedsQL versions were used to elicit patient-reported symptom distress and HRQOL.15–17,20 Parent-proxy versions of the PQ-MSAS and PedsQL were used for very young children and older children who declined to self-report. PQ-MSAS and PedsQL total scores were calculated as the average of all nonmissing individual item scores. Subscale scores were calculated by averaging the appropriate nonmissing subitems. All scores were standardized to scales of 0 to 100 (with 100 being the worst on the PQ-MSAS and 100 being the best on the PedsQL). For descriptive purposes, individual symptom scores were dichotomized as being high or low distress, as reported previously.15

Other Covariates

Clinical and demographic data were extracted from medical records, including age, sex, cancer type, and date of diagnosis. Disease status as well as details regarding cancer-directed therapy received within the 10 days before administration of PediQUEST also were collected. As previously reported, cancer-directed therapy was characterized as mild (oral or outpatient chemotherapy and/or minor procedures), moderate (inpatient intravenous chemotherapy, radiotherapy alone or with oral chemotherapy, or a major procedure), or intense (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation conditioning, radiotherapy with intravenous chemotherapy, or surgery).15

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics and PROs were summarized using descriptive statistics, including medians and ranges for the continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables. Baseline characteristics were compared between low-income and high-income groups using the Fisher exact test. The number of surveys returned and time from enrollment to last survey were compared between income groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. PROs, including PQ-MSAS total, physical, and psychological scores and PedsQL total, physical, emotional, social, and school scores, were compared between income groups using multivariable generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to account for multiple observations (surveys) per patient. Multivariable GEE models were adjusted for sex, age at the time of the initial survey, cancer type, intervention arm (PediQUEST intervention vs standard of care), time since disease progression, and cancer treatment intensity if treatment was received within the 10 days before the survey, consistent with prior PediQUEST publications.16,17 Symptom prevalence was compared between the low-income and high-income groups using GEE models. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Of the of 86 parents who completed the baseline SCCC, 78 patients (91%) had evaluable household income and were included in the current analysis. As shown in Table 1, 28% of the cohort (22 patients) was considered to be of low income. There were no statistically significant differences noted with regard to age, race, sex, or diagnosis between the high-income and low-income groups. There also was no difference noted with regard to the percentage of patients receiving cancer-directed treatment within the 10 days prior to enrollment between the high-income and low-income groups. The percentage of patients treated at the 3 participating hospitals did not differ by income. Low-income parents were significantly less likely to have a college education (P=.003) and to have a partner (P=.014). Fifty-six high-income patients returned 589 surveys and 22 low-income patients returned 173 surveys. The median number of surveys per patient was 10 (range, 1–33 surveys) in the high-income group and 7 (range, 2–20 surveys) in the low-income group; there was no difference noted with regard to the number of surveys returned between income groups (P=.14). There also were no differences noted in the time from enrollment to last survey between income groups (P=.7). The characteristics of those who reported house-hold income were similar to those who did not report household income.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Income

| Overall N=78 | Low Income n=22 | High Income n=56 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||

| Child sex | 1 | |||

| Male | 34 (44) | 10 (45) | 24 (43) | |

| Female | 44 (56) | 12 (55) | 32 (57) | |

| Child age, y | .32 | |||

| <13 | 42 (54) | 14 (64) | 28 (50) | |

| ≥13 | 36 (46) | 8 (36) | 28 (50) | |

| Parent educational level | .003 | |||

| ≤High school graduate | 28 (36) | 14 (64) | 14 (25) | |

| ≥Some college | 50 (64) | 8 (36) | 42 (75) | |

| Parent marital status (n=77) | .014 | |||

| Partner | 65 (84) | 14 (67) | 51 (91) | |

| No partner | 12 (16) | 7 (33) | 5 (9) | |

| Parent race/ethnicity | .11 | |||

| White | 69 (88) | 17 (77) | 52 (93) | |

| Nonwhite | 9 (12) | 5 (23) | 4 (7) | |

| Intervention arm | .8 | |||

| Control arm | 39 (50) | 10 (45) | 29 (52) | |

| Treatment arm | 39 (50) | 12 (55) | 27 (48) | |

| Diagnosis | .31 | |||

| Hematological malignancy | 23 (30) | 9 (41) | 14 (25) | |

| Brain tumor | 8 (10) | 1 (5) | 7 (13) | |

| Solid tumor | 47 (60) | 12 (55) | 35 (63) | |

| Location of care | .25 | |||

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital | 45 (58) | 16 (73) | 29 (52) | |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | 19 (24) | 3 (14) | 16 (29) | |

| Seattle Children’s Hospital | 14 (18) | 3 (14) | 11 (20) | |

| Median time from enrollment to last survey, mo | 6.0 | 6.4 | 6.0 | .7 |

| Median no. of surveys per patient | 8.5 | 7.0 | 10.0 | .14 |

Symptom Prevalence and Distress Among the High-Income and Low-Income Groups

Within the entire cohort, the 5 most frequently reported physical symptoms were fatigue (48%), pain (47%), drowsiness (41%), nausea (36%), and lack of appetite (34%). The 5 most frequently reported psychological symptoms were irritability (39%), sleep disturbances (30%), worry (27%), nervousness (28%), and sadness (25%). Only pain was significantly more prevalent in the low-income group compared with the high-income group (111 of 173 surveys [64%] vs 249 of 589 surveys [42%]; P=.02). When pain was present, it was highly distressing in both the low-income (95 of 111 surveys [86%]) and high-income (208 of 249 surveys [84%]) groups.

The predicted mean PQ-MSAS scores for the high-income and low-income groups are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. In multivariable models, low-in-come patients demonstrated a uniform, but not statistically significant, trend toward higher PQ-MSAS total (mean difference βlow-high=3.1; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −0.08 to 6.2 [P=.06]), physical (β=3.8; 95% CI, −0.4 to 8.0 [P=.09]), and psychological (β=3.46; 95% CI, −1.91 to 8.84 [P=.21]) scores.

Figure 1.

Symptom distress by income. PQ-MSAS indicates PediQUEST Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale.

TABLE 2.

Effect of Income on Symptom Distress and HRQOL in Multivariable Modelsa

| Outcome | No. of Subjects | No. of Surveys | Adjusted Mean Difference in Score, βlow-high (95% CI) | Adjusted P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom distress | ||||

| PQ-MSAS total score | 78 | 756 | 3.1 (−0.08 to 6.2) | 0.06 |

| PQ-MSAS physical score | 78 | 760 | 3.8 (−0.4 to 8.0) | .09 |

| PQ-MSAS psychological score | 78 | 760 | 3.5 (−1.9 to 8.8) | .21 |

| HRQOL | ||||

| PedsQL total score | 78 | 754 | −7.9 (−14.8 to −1.1) | .03 |

| PedsQL physical score | 78 | 755 | −11.2 (−21.2 to −1.2) | .04 |

| PedsQL emotional score | 78 | 754 | −5.8 (−13.6 to 2.0) | .15 |

| PedsQL social score | 78 | 754 | −2.5 (−9.3 to 4.2) | .47 |

| PedsQL school score | 78 | 754 | −9.8 (−17.8 to −1.8) | .03 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; β, effect size; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0; PQMSAS, PediQUEST Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale.

Effect sizes, 95% CIs, and P values were calculated from multivariable generalized estimating equations models controlling for sex, age, cancer type, intervention arm, time since disease progression, and cancer treatment intensity.

HRQOL Among the High-Income and Low- Income Groups

Predicted mean PedsQL total and subscale scores for the high-income and low-income groups are depicted in Figure 2 and Table 2. In multivariable models, low income was associated with a uniform trend toward lower total (mean difference βlow-high=−7.9; 95% CI, −14.8 to −1.1 [P=.03]), physical (β=−11.2; 95% CI, −21.2 to −1.2 [P=.04]), emotional (β=−5.8; 95% CI, −13.6 to 2.0 [P=.15]), social (β=−2.52; 95% CI, −9.27 to 4.24 [P=.47]), and school (β=−9.8; 95% CI, −17.8 to −1.8 [P=.03]) PedsQL scores, with statistically significant differences noted in the total, physical, and school subscales (Fig. 2) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Health-related quality of life by income. PedsQL indicates Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0.

DISCUSSION

Children with advanced cancer experience great distress related to uncontrolled symptoms. In this exploratory analysis, we found that children from low-income families experienced a significantly higher prevalence of pain compared with children from high-income families (64% vs 42%) and trended toward greater symptom distress compared with children from high-income families. Perhaps not surprisingly, children from low-income families also reported corresponding poorer HRQOL.

This analysis was performed using data from what to our knowledge is the largest prospective cohort study of PROs among children with advanced cancer. To our knowledge, it is the first study to report on income-related inequities in patient-reported symptom distress in pediatric patients with cancer. That these data identify clinically relevant trends in both symptom and HRQOL based on income despite the small sample size and exploratory nature of the current investigation is compelling and supports the significant need for further study.

Although we were unable to investigate mechanisms that might explain these disparities, several hypotheses have emerged. It is possible that providers prescribed fewer opioids to children from low-income families. Prior literature among adults and children indicate that opioid prescribing behaviors differ based on patient race and socioeconomic status in multiple settings.21–23 Distinct from prescribing patterns, children from low-income families may have had less access or inferior adherence to prescribed opiates, possibly due to insurance coverage or local pharmacy characteristics. Prior work has demonstrated differential availability of opioids at local pharmacies24 and decreased adherence to medications at home12,13 for children from low-income families. Communication challenges between low-income patients and their providers may have meant that symptoms went unrecognized and therefore unaddressed. There is evidence that patient-provider communication experiences differ based on a patient’s sociodemographic background, with patients of minority race/ethnicity demonstrating lower prognostic knowledge,25,26 poorer understanding of the goals of treatment,27 and less participation in decision making.28 Although enrolling on the PediQUEST study may have facilitated communication by eliciting PROs, differences in communication experiences between low-income patients and their providers nonetheless may persist and contribute to symptom experience. There is a growing body of literature focusing on the negative effects of toxic stress on children’s health and supporting the important role that toxic stress plays in the development of widespread health disparities.29 To the best of our knowledge, the impact of toxic stress in pediatric patients with cancer is largely unexplored and future studies might examine how toxic stress–induced pathways link income and child PROs. With regard to our observed differences in HRQOL, although prior data from children with advanced cancer are limited, these results are consistent with well-documented socio-demographic differences in HRQOL in a variety of other pediatric chronic conditions.30 Low-income status has been shown to negatively impact HRQOL in children with asthma,31 sickle cell disease,32 and cardiac disease.33 In addition, other PediQUEST analyses have suggested that symptom distress is strongly associated with HRQOL, a finding that supports the patterns observed herein.16

Our ability to detect significant relationships between household income and PROs was likely dampened by the relatively small number of patients. Nevertheless, we were able to identify trends in symptom distress. It should be noted that the current analyses were not adjusted for patient race/ethnicity because we were limited by a small sample, with 88% of patients being white. Furthermore, the small number of patients of minority race included in the current study may limit the generalizability of its findings. In addition, the current study was conducted at 3 large academic pediatric cancer centers and therefore the results may not be generalizable to all children with advanced cancer. In addition, several covariates, including a child’s insurance status, distance from home to the treatment center, location of survey completion (inpatient vs outpatient), and hospice enrollment at end of life may have impacted a child’s ability to access supportive care services and led to differences in symptom distress and QOL. These variables were not available for analysis in the current study cohort, and should be included in future studies regarding this topic. Eight patients in the PediQUEST study did not report income data and were not included in the current analysis. Demographics were similar between those who provided income data and those who did not, and we do not have reason to believe that this biased our analyses.

Children from low-income families experience high symptom burden and, in particular, high pain prevalence compared with children from high-income families. HRQOL also is worse for children from low-income families. Although the results of the current study provide new evidence of socioeconomic-related inequities in the illness experience for children with advanced cancer, further research is needed to validate these findings in more diverse populations, to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these differences, and to uncover ways in which we can ameliorate these inequities. As we work to address suffering for all children with cancer, these data highlight the presence of a uniquely vulnerable population underserved by our current clinical care.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grants 1K07 CA096746–01 and 1K07CA211847, a Charles H. Hood Foundation Child Health Research Award, an American Cancer Society Pilot and Exploratory Project Award in Palliative Care of Cancer Patients and Their Families, and the Helen Gurley Brown Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, et al. Patients’ and parents’ needs, attitudes, and perceptions about early palliative care integration in pediatric oncology. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1214–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakur N, Martin M, Castellanos E, et al. Socioeconomic status and asthma control in African American youth in SAGE II. J Asthma 2014;51:720–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood JR, Miller KM, Maahs DM, et al. T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Most youth with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry do not meet American Diabetes Association or International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical guidelines. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2035–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor GT, Quinton HB, Kneeland T, et al. Median household income and mortality rate in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 2003;111(4 pt 1):e333–e339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knight JM, Syrjala KL, Majhail NS, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and socioeconomic status as predictors of clinical outcomes after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a study from the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network 0902 Trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:2256–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2011;117:2779–2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas BC, Waller A, Malhi RL, et al. A longitudinal analysis of symptom clusters in cancer patients and their sociodemographic predictors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:566–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Check DK, Reeder-Hayes KE, Zullig LL, Weinberger M, Basch EM, Dusetzina SB. Examining racial variation in antiemetic use and postchemotherapy health care utilization for nausea and vomiting among breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:4839–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John DA, Kawachi I, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ. Disparities in perceived unmet need for supportive services among patients with lung cancer in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. Cancer 2014;120:3178–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walling AM, Keating NL, Kahn KL, et al. Lower patient ratings of physician communication are associated with unmet need for symptom management in patients with lung and colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e654–e669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bona K, Blonquist TM, Neuberg DS, Silverman LB, Wolfe J. Impact of socioeconomic status on timing of relapse and overall survival for children treated on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocols (2000–2010). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia S, Landier W, Hageman L, et al. 6MP adherence in a multiracial cohort of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood 2014;124:2345–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung L, Yanofsky R, Klaassen RJ, et al. Quality of life during active treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Cancer 2011;128:1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and distress in children with advanced cancer: prospective patient-reported outcomes from the PediQUEST Study. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1928–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Quality of life in children with advanced cancer: a report from the PediQUEST study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anker B, Tripodis Y, Long WE, Garg A. Income disparities in the association of the medical home with child health. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57:827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma CT, Gee L, Kushel MB. Associations between housing instability and food insecurity with health care access in low-income children. Ambul Pediatr 2008;8:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 2002;94:2090–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169: 996–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joynt M, Train MK, Robbins BW, Halterman JS, Caiola E, Fortuna RJ. The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status and race on the prescribing of opioids in emergency departments throughout the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1604–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA 2008;299:70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, Senzel RS, Huang LL. “We don’t carry that”–failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilowite MF, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Disparities in prognosis communication among parents of children with cancer: the impact of race and ethnicity. Cancer 2017;123:3995–4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 1999;282:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Didsbury MS, Kim S, Medway MM, et al. Socio-economic status and quality of life in children with chronic disease: a systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:1062–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erickson SR, Munzenberger PJ, Plante MJ, Kirking DM, Hurwitz ME, Vanuya RZ. Influence of sociodemographics on the health-related quality of life of pediatric patients with asthma and their caregivers. J Asthma 2002;39:107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palermo TM, Riley CA, Mitchell BA. Daily functioning and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease pain: relationship with family and neighborhood socioeconomic distress. J Pain 2008;9:833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassedy A, Drotar D, Ittenbach R, et al. The impact of socio-economic status on health related quality of life for children and adolescents with heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]