Abstract

Introduction

Despite the fact that millions of scars affect individuals annually, little is known about their psychosocial impact and overall quality of life (QOL) on individuals. Scars from multiple aetiologies may cause psychiatric and emotional disturbances, can limit physical functioning and increase costs to the healthcare system. The purpose of this protocol is to describe the methodological considerations that will guide the completion of a scoping review that will summarise the extent, range and nature of psychosocial health outcomes and QOL of scars of all aetiologies.

Methods and analysis

A modified Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework will be completed, namely having ongoing consultation between experts from the beginning of the process, then (1) identifying the research question/s, (2) identifying the relevant studies from electronic databases and grey literature, with (3) study selection and (4) charting of data by two independent coders, and (5) collating, summarising and reporting data. Experts will include a health information specialist (TAW), scar expert (JSF), scoping review consultant (SCK), as well as at least two independent coders (NZ, AM).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval will not be sought for this scoping review. We plan to disseminate this research through publications, presentations and meetings with relevant stakeholders.

Keywords: scar, psychosocial outcomes, quality of life, burn, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A scoping review examining the psychosocial and quality of life impact on individuals with scars has not been published before.

A rigorous methodological framework will be completed with numerous quality checks throughout and every effort to obtain access to non-published work will be completed.

A hybrid psychosocial and quality of life definition used with a new health outcome coding scheme will be used to examine the literature.

Limitations include English articles, articles examining scars themselves (and not a surrogate marker of scars like total body surface area), and the scoping review process is time consuming

Background

Millions of people develop scars from burn injuries, surgeries and traumatic events.1–3 Scars are known to have wide ranging effects on individuals. For example, facial scars have been shown to impact psychosocial functioning causing increased anxiety and self-consciousness,4 traumatic scars can have the potential to impair social functioning and emotional well-being,5 and burn scars have been shown to decrease physical functioning.6 Recently, hypertrophic scars have been labelled the greatest unmet challenge both psychosocially and functionally to burn rehabilitation.7

However, despite how common scars are, little is known about the psychosocial health outcomes that scars have on the individual. Scar-specific research has predominantly focused on clinical trials of scar modulation, diagnosis and improving our understanding of the physical symptoms of scars. Unfortunately, this research does not align with the WHO’s definition of health that encompasses physical, mental and social well-being.8 Since scars are formed from inciting injuries (such as a burn/traumatic injury, surgery, inflammatory or oncologic disease) reviews regarding psychosocial impact and quality of life (QOL) of burn9–11 and traumatic injuries12–16 do exist but a comprehensive review has not been conducted across all scar aetiologies. Furthermore, there has been an increased interest in psychosocial outcomes from the scientific communities themselves. For example, the 2016 American Burn Association’s State of the Science conference recently called for scar research to extend to psychosocial impacts.17

The exploration of psychosocial health outcomes and overall QOL of individuals with scars will be explored through a scoping review. Scoping reviews, as opposed to systematic reviews which synthesise quantitative findings, aim to investigate the extent (scar aetiology and patients affected), range (of patients and scar severity) and nature (what kind of psychosocial and QOL outcomes for this patient population) of research activity18 19 especially when a topic has either not been extensively reviewed, is complex, or heterogeneous.20 In particular, scoping reviews map a given field of study, identify gaps in the current state of knowledge and aim to disseminate findings.18 To our knowledge, there is no such scoping review in this area. As a result, the findings and concepts generated from this scoping review will be able to inform clinicians about the effects of scarring on an individual across scar aetiologies given the conceptual generalisability and transferability21 of results ensured by the methodological rigour in the scoping review process.21

The protocol aims to comprehensively examine the effect of scars on individuals from a psychosocial health and QOL perspective. The term ‘psychosocial’ has been used broadly in research. As described by Martikainen et al,22 the term psychosocial has been used to describe causes and risk factors, mediating factors and contexts, and outcomes of various disease states and encompasses ‘psychological distress’, ‘psychosocial well-being’ and ‘psychosocial health’. The term ‘psychosocial outcome’ has been further described and examined broadly in the context of emotional and social function,23 24 well-being, life satisfaction, self-esteem and overall QOL.25 It has also been examined with particular disease states such as depression,24–27 anxiety,26 27 and emotions such as distress26 in various clinical studies. Given the multiple definitions and lack of standardisation of psychosocial and QOL, we have created a hybrid psychosocial framework and will examine the scar through this lens. This framework is expanded on in stage 5.

The purpose of this protocol is to describe the methodological considerations that will guide the completion of a scoping review that will summarise the extent, range and nature of psychosocial health and QOL outcomes of scars of all aetiologies. Poor psychosocial outcomes have been associated with delayed recovery,28 chronic disease progression and even mortality,29–31 and the WHO has indicated that psychosocial risks have become a major health concern.32 33 We are interested in approaching the scar literature from a holistic viewpoint encompassing all types of scar aetiologies. This is an uncommon way of approaching the research question as the literature tends to be described using one scar aetiology. We are aiming to capture the full range of psychosocial outcomes from the perspective of patients with scars from different aetiologies (ie, scar from a major trauma vs a small scar from spilled tea vs acne or self-harm scars, and so on). We aim to identify the gaps in knowledge that may exist in terms of understanding how a scar may impact the psychosocial well-being of an individual. The outcome of the scoping review will be to develop a comprehensive understanding of the current literature on the topic in order to improve clinical encounters, formulate new research questions and, ultimately, improve patient care.

Methods and analysis

A modified Arksey and O’Malley18 framework will be used in this scoping review. The original methodological framework of how to conduct a scoping review by Arksey and O’Malley includes six major stages: (1) identifying the research question/s; (2) identifying the relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarising and reporting data; and an optional stage, (6) ongoing consultation.18 This framework has been used to structure a number of scoping reviews in other areas of research.19 34 35 However, similar to Grant et al,34 we feel that the optional stage 6, ongoing consultation, should be included as a first stage. Arksey and O’Malley18 endorse the use of consultation to help provide valuable insights, possibly additional resources, and alternative approaches to the research questions examined. In addition, Levac et al 36 suggest recommendations to refine the original framework with additional steps for each stage and specific considerations for scoping reviews in health research which we have adopted (refer to table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of methods and overview of stages

| Arksey and O’Malley18

Stage |

Arksey and O’Malley Details/stage | Levac et al

36

Modifications to framework |

Overview of phases |

| Ongoing consultation* |

|

|

Stakeholders:

|

| Identifying research questions |

|

|

|

| Identify relevant studies | Identify studies via:

|

|

Will identify studies in:

Time span: no restriction. |

| Study selection |

|

|

|

| Charting the data | Charting: synthesising and interpreting qualitative data by sifting, charting and sorting materials based on key issues and themes. |

|

Charting, synthesising and interpreting qualitative data by sifting, charting and sorting materials based on key issues and themes by an iterative process of:

|

| Collating, summarising and reporting data |

|

|

|

Stage 1: ongoing consultation

As mentioned above, Arksey and O’Malley18 suggest ongoing consultation to occur at the end of the scoping review process, however as noted by Grant et al,34 we believe ongoing consultation should be at the beginning. As stated by Levac et al,36 ongoing consultation is an essential stage with an established purpose, which shapes the whole process of the scoping review. Three consultants have been selected: a specialist in scar modulation, a second with expertise in scoping reviews and a third health information specialist to ensure a thorough literature search of all pertinent published and non-published materials. We have specifically chosen these individuals based on their academic backgrounds and experience in their respective areas and will be involved in each stage moving forward.

Stage 2: identifying the research questions

Scoping reviews are expected to be comprehensive in nature and this goal is achieved with an appropriate research question. Arksey and O’Malley18 suggest keeping the research question broad but Levac et al 36 suggest having a broad research question with a clear scope of inquiry and defined outcome. Thus, following Levac et al’s36 research question schema, our research questions are: how do scars impact patients from a psychosocial and QOL perspective? Second, of those studies included, what are the scar and patient variables examined? Specifically, variables that will be assessed are the location of the scar (visible or not, defined as any scar on the face, neck, hands and/or feet), scar aetiology, and patient ethnicity, gender and age (child vs adult). These variables were chosen with the guidance of the scar specialist (JSF) and through known debates in the literature regarding scar visibility,37 aetiology,38 and location,4 ethnicity,39 gender40 and age.41

By better understanding the psychosocial and QOL impact a scar may have on an individual, clinical care may be enhanced through the creation of guidelines, patient advocacy measures and improvement of clinical care. These variables were chosen with the guidance of the scar specialist and through known debates in the literature regarding scar visibility,37 aetiology,38 and location,4 ethnicity,39 gender40 and age.41

Stage 3: identifying relevant studies

Identifying relevant studies will occur through three separate stages. First, through consultation with a health information specialist, we will conduct a key article search targeting relevant databases which will include MEDLINE, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE Classic, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Search terms will include a combination of appropriate database subject headings (eg, MeSH, Emtree) and text words for the concepts of scars and psychological impact (self concept or self image or quality of life or satisfaction or sexuality or social adjustment or social desirability or social skills or social isolation or shame or stigma or anxiety or fear or happiness). A sample search strategy is found in online supplementary appendix 1. Second, pertinent journals selected by the scar expert (JSF) will be hand-searched (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Journal of Burn Care, Journal of Trauma, Burns, JAPRAS, Cleft Palate Journal, Body Image) by two coders (AM, NZ). Finally, as per scoping review best practice guidelines, grey literature19 42 will be reviewed, specifically patient advocacy and association websites will be searched (by AM) for additional material regarding guidelines, reviews and clinical studies on the topic. Relevant journals and websites will be identified through consensus with the expert panel as well as through the preliminary database search. Authors will be contacted for any conference abstracts with minimal information or if full-text articles are not accessible. Finally, review articles will be hand-searched for relevant topics from key papers found in the article database search (AM, NZ). The searches will be limited to English with no time restriction.

bmjopen-2017-021289supp001.pdf (28.1KB, pdf)

Stage 4: study selection

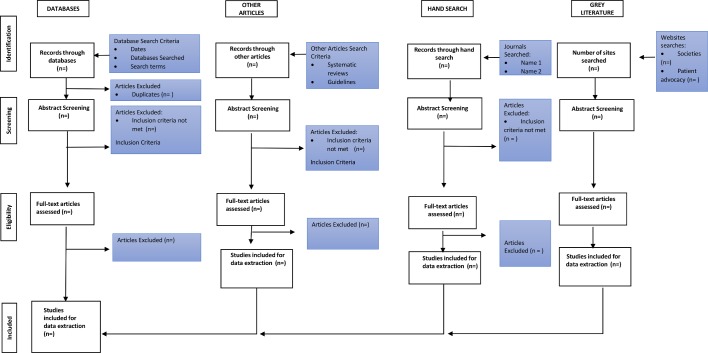

Levac et al 36 suggest a team approach to study selection including both a transparent and replicable process with at least two coders selecting articles independently. Additionally, Reeves et al 43 propose a qualitative inter-rater reliability protocol for two or more independent coders with quality checks from a third party. Based on these suggestions, two coders will meet at the beginning, midpoint and final stage with disagreements resolved by a third party. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be completed after the literature review. A pilot sample of abstracts will be completed to ensure that all coders have a common understanding of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A summary figure of all abstracts will be completed (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Stage 5: charting the data

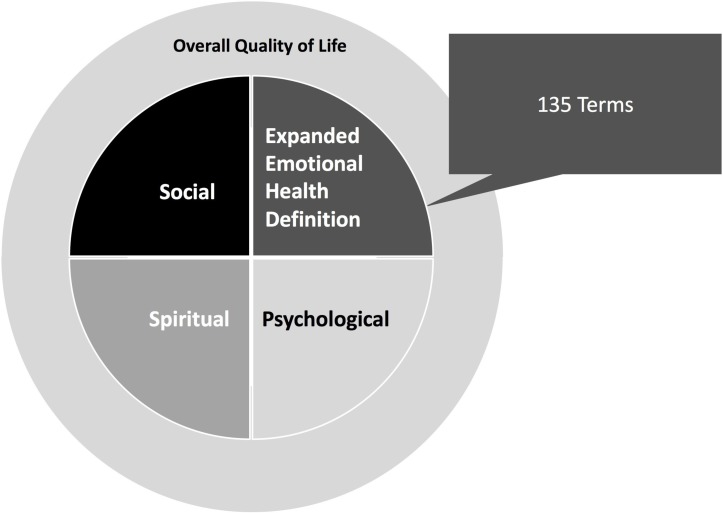

Similar to the previous stages, charting the data will include synthesising and interpreting the qualitative results in the included articles by sifting and sorting materials based on the key issues and themes.44 Data extraction will be an iterative process and for quality assurance purposes, two independent coders will extract data from the literature into a preformed template on Excel. A coding manual will be created to ensure that the data extracted and coded are the same between two coders. Information extracted will consist of quantitative data regarding the articles and authors (such as number of authors, year of publication, study location), patient information (age, gender), scar information (scar aetiologies, location and visibility of scars), how scars were assessed/described and psychosocial and QOL impact on the individual. A hybrid definition encompassing elements of both psychosocial and generalised QOL will be used. First, we are specifically interested in examining psychosocial health from the framework created by Dr Lana Zinger,45 which describes psychosocial health as consisting of emotional (‘feeling’), mental (‘thinking’), social (interactions with others) and spiritual (belief system, feeling of belonging) health. Further, emotions will be categorised into primary and secondary emotions as per Shaver et al.46 In addition, the definition of QOL is provided by the WHO, specifically: ‘as an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment.’47

Further, the WHO defines QOL as an indicator of well-being as related to healthcare.47 These definitions will be used to define the general well-being not attributed to the psychosocial subcategories as defined above (see figure 2). As explained in the introduction, given the heterogeneity of psychosocial definitions,22–27 on careful consideration the team chose a simple and comprehensive definition that could be easily applied by both coders. To our knowledge, this is the first time a psychosocial framework has been used to inform the design and implementation of a scoping review coding structure within the literature on scoping review methodology.

Figure 2.

Framework (modified from Zinger [45]).

Stage 6: collating, summarising and reporting data

Finally, we will present an overview of data from a quantitative and qualitative perspective. Quantitative analysis will be conducted through SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Inc, Cary NC) software and will consist of subgroup analysis of each variable (scar visibility, location, and aetiology and patient’s age and ethnicity). This analysis will be conducted to identify trends and gaps in knowledge as applied by the modified psychosocial framework. Content analysis will be used to guide the qualitative assessment.44 We aim to report the results in a peer-reviewed journal article as well as in a conference setting. Further, we expect this work to generate a discussion and possibly lead to future research depending on the gaps in knowledge that are discovered. Finally, we will use these data to create guidelines, patient advocacy measures and, ultimately, improve patient care.

Patient and public involvement

The patients and the public were not involved in this protocol as the first step of the scoping review was to find published literature in the area. Future studies will incorporate the patient’s perspective.

Ethics and dissemination

There is no need for a formal ethical review because no primary data will be collected. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to review the literature of the psychosocial and QOL impact of scars using a comprehensive scoping review methodology. We anticipate the study duration to occur from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2018. We hope to compile the multitude of psychosocial effects that scars may have by investigating the extent, range and nature of research conducted within all scar patient populations (encompassing different ages and ethnicities as well as scar aetiologies) through this scoping review. The findings from the review will be submitted to relevant journals and conferences such as the American Burn Association and Canadian and American Plastic Surgery conferences. Finally, we aim to share our results with key stakeholders to help change clinical practice. By better understanding the psychosocial health and QOL impact of scars on the individual, we can formulate new research questions through the identification of research gaps, creation of treatment guidelines and, ultimately, improvement of patient care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions. NZ, SCK, JSF and TAW were involved in conceptualisng this review. NZ, SCK and JSF were involved in writing this protocol. DJ, JZ, AM and TAW commented critically on several drafts of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine’s Edward Christie Stevens Fellowship in Medicine and the Chisholm Memorial Fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Abdullah F, Gabre-Kidan A, Zhang Y, et al. Report of 2,087,915 Surgical Admissions in U.S. Children: Inpatient Mortality Rates by Procedure and Specialty. World J Surg 2009;33:2714–21. 10.1007/s00268-009-0219-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tepas JJ, Frykberg ER, Schinco MA, et al. Pediatric trauma is very much a surgical disease. Ann Surg 2003;237:775–81. 10.1097/01.SLA.0000068118.01520.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tracy ET, Englum BR, Barbas AS, et al. Pediatric injury patterns by year of age. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:1384–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tebble NJ, Adams R, Thomas DW, et al. Anxiety and self-consciousness in patients with facial lacerations one week and six months later. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;44:520–5. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown BC, McKenna SP, Siddhi K, et al. The hidden cost of skin scars: quality of life after skin scarring. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61:1049–58. 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schneider JC, Holavanahalli R, Helm P, et al. Contractures in burn injury: defining the problem. J Burn Care Res 2006;27:508–14. 10.1097/01.BCR.0000225994.75744.9D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG, Branski LK, et al. Hypertrophic scarring: the greatest unmet challenge after burn injury. Lancet 2016;388:1427–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31406-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Constitution of WHO: principles. 2017. http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/ (22 Mar 2017).

- 9. Klein MB, Lezotte DC, Heltshe S, et al. Functional and psychosocial outcomes of older adults after burn injury: results from a multicenter database of severe burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2011;32:66–78. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318203336a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stavrou D, Weissman O, Tessone A, et al. Health related quality of life in burn patients--a review of the literature. Burns 2014;40:788–96. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin-Herz SP, Zatzick DF, McMahon RJ. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents following traumatic injury: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2012;15:192–214. 10.1007/s10567-012-0115-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moi AL, Haugsmyr E, Heisterkamp H. Long-term study of health and quality of life after burn injury. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2016;29:295–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rissanen R, Berg HY, Hasselberg M. Quality of life following road traffic injury: A systematic literature review. Accid Anal Prev 2017;108:308–20. 10.1016/j.aap.2017.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stocchetti N, Zanier ER. Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: a narrative review. Crit Care 2016;20:148–57. 10.1186/s13054-016-1318-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fineblit S, Selci E, Loewen H, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life after Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury/Concussion: A Systematic Review. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:1561–8. 10.1089/neu.2015.4292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christensen J, Ipsen T, Doherty P, et al. Physical and social factors determining quality of life for veterans with lower-limb amputation(s): a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:2345–53. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1129446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tredget EE, Shupp JW. Schneider JC. Scar Management Following Burn Injury. JBCR 2017;38:146–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesizing research evidence : Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, et al Studying the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services: Research methods. London: Routledge, 2001:188–219. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitto SC, Chesters J, Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust 2008;188:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1091–3. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dunn J, Watson M, Aitken JF, et al. Systematic review of psychosocial outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma. Psychooncology 2017;26:1–10. 10.1002/pon.4290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fann JR, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Psychosocial outcomes of an electronic self-report assessment and self-care intervention for patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2017;26:1–6. 10.1002/pon.4250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lan X, Xiao H, Chen Y. Effects of life review interventions on psychosocial outcomes among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17 Epub Ahead of Print 10.1111/ggi.12947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ford JS, Chou JF, Sklar CA, et al. Psychosocial Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3608–14. 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.5733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glozier N, Moullaali TJ, Sivertsen B, et al. The Course and Impact of Poststroke Insomnia in Stroke Survivors Aged 18 to 65 Years: Results from the Psychosocial Outcomes In StrokE (POISE) Study. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 2017;7:9–20. 10.1159/000455751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glass TA, Matchar DB, Belyea M, et al. Impact of social support on outcome in first stroke. Stroke 1993;24:64–70. 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 1999;318:1460–7. 10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: a critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Psychol 2002;53:341–69. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med 2002;2:267–314. 10.1055/s-2002-35401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leka S, Cox T. The European Framework for Psychosocial Risk Management. Nottingham: I-WHO publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization. Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: an overview. 2010. http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/ (22 Mar 2017).

- 34. Grant RE, Sajdlowska J, Van Hoof TJ, et al. Conceptualization and Reporting of Context in the North American Continuing Medical Education Literature: A Scoping Review Protocol. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2015;35 Suppl 2:S70–S74. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamilton CB, Wong MK, Gignac MA, et al. Validated Measures of Illness Perception and Behavior in People with Knee Pain and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Scoping Review. Pain Pract 2017;17:99–114. 10.1111/papr.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg L, et al. Visible vs hidden scars and their relation to body esteem. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004;25:25–32. 10.1097/01.BCR.0000105090.99736.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Sullivan ST, O’Shaughnessy M, O’Connor TP. Aetiology and management of hypertrophic scars and keloids. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1996;78:168–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bayat A, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Skin scarring. BMJ 2003;326:88–92. 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gangemi EN, Gregori D, Berchialla P, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for pathologic scarring after burn wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2008;10:93–102. 10.1001/archfaci.10.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwanholt CA, Ridgway CL, Greenhalgh DG, et al. A prospective study of burn scar maturation in pediatrics: does age matter? J Burn Care Rehabil 1994;15:416–20. 10.1097/00004630-199409000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reeves S, Barr H, Birch I, et al. A BEME Systematic Review of the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Health and Social Care Practitioners, Professional Practice. Patient/client Health and Social Outcomes 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278667351. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zinger L. “Health The Basics, Green Edition: Chapter 2: Psychosocial Health.” Los Angelese Harbor College. Accessed from https://www.lahc.edu/classes/pe/health/health11media/Health_11_Chapter_2_Psychosocial-PDF.pdf.

- 46. Shaver P, Schwartz J, Kirson D, et al. Emotional Knowledge: Further Exploration of a Prototype Approach: Parrott G, Emotions in Social Psychology: Essential Readings. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press, 2001:26–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47. World Health Organization. “WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life”: World Health Organization, 2018. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/ (13 Jun 2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021289supp001.pdf (28.1KB, pdf)