Abstract

Objective:

To assess the occurrence of narcolepsy following influenza vaccines used in the United States that contained the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus strain.

Methods:

A population-based cohort study in the Vaccine Safety Datalink with an annual population of over 8.5 million people. All persons <30 years old who received a 2009 pandemic or a 2010–2011 seasonal influenza vaccine were identified. Their medical visit history was searched for a first-ever occurrence of an ICD-9 narcolepsy diagnosis code through the end of 2011. Chart review was done to confirm the diagnosis and determine the date of symptom onset. Cases were patients who met the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition narcolepsy diagnostic criteria. We compared the observed number of cases following vaccination to the number expected to occur by chance alone.

Results:

The number vaccinated with 2009 pandemic vaccine was 650,995 and with 2010–2011 seasonal vaccine was 870,530. Among these patients, 70 had a first-ever narcolepsy diagnosis code following vaccination, of which sixteen had a chart-confirmed incident diagnosis of narcolepsy. None had their symptom onset during the 180 days following receipt of a 2009 pandemic vaccine compared to 6.52 expected, and two had onset following a 2010–2011 seasonal vaccine compared to 8.83 expected.

Conclusions:

Influenza vaccines containing the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus strain used in the United States were not associated with an increased risk of narcolepsy. Vaccination with the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine viral antigens does not appear to be sufficient by itself to increase the incidence of narcolepsy in a population.

Introduction

Narcolepsy is a chronic disorder of the central nervous system characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness.1 Narcolepsy can occur with or without cataplexy, which consists of sudden short episodes of the loss of motor tone triggered by emotions.1 The incidence of narcolepsy is highest during the teen years and most cases begin before the age of 25,1, 2 but many individuals with narcolepsy are not diagnosed until several years after the onset of symptoms.3

In August 2010, public health agencies in Sweden and Finland announced that they had received reports of narcolepsy as an adverse event following vaccination with Pandemrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals [GSK]), an adjuvant-containing influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 monovalent pandemic vaccine.4, 5 By February 2011, twelve countries had received similar reports, and a preliminary investigation in Finland found an incidence of narcolepsy nine times higher among people aged 4–19 years who had received Pandemrix compared to those who had not.6 The narcolepsy symptoms began within six months following vaccination in 96% of the cases.7 Pandemrix was used in 47 countries during the 2009 pandemic. A similar GSK vaccine, Arepanrix, was used in additional countries. Neither of these vaccines nor any other adjuvant-containing influenza vaccine was used in the United States (US). A review of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System data did not indicate any association between U.S.-licensed influenza vaccines and narcolepsy.8

In order to further evaluate the possibility of an association between influenza vaccines used in the US that contained the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus strain and narcolepsy, we conducted an epidemiologic assessment in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) population.

Methods

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and several integrated health care organizations (sites) in the US that performs vaccine safety research and surveillance.9 Eight sites with a combined annual population of more than 8.5 million patients contributed data to this study.

Incidence of narcolepsy diagnosis in the population

We searched each patient’s health care visit history for visits with an International Classification of Disease, 9th revision (ICD-9) narcolepsy diagnosis code (347.00 – 347.11), regardless of the patient’s vaccination history. Visit records were available starting between 1990 and 2005 depending on the site. The visit date associated with the first-ever occurrence of any narcolepsy ICD-9 code in a patient’s record was considered the incident diagnosis date. The number of patients with an incident diagnosis was divided by the number of patients enrolled in the VSD population to calculate the incidence rate (IR) of diagnosis for the years 2006 through 2011. We compared the diagnosis IR following the start of the influenza pandemic in April 2009 to the period prior to the start of the pandemic.

Vaccinated cohort

We identified all VSD patients who received an influenza vaccine that contained the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus strain during either the 2009 influenza pandemic or the 2010–2011 influenza season. These included the 2009 monovalent inactivated vaccine (MIV) and monovalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (MLAIV) and the 2010–2011 seasonal influenza trivalent inactivated vaccine (TIV) and live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV). Patients had to have received the vaccine prior to or during enrollment in a VSD site. Among this cohort, we identified all patients with a health care visit code for narcolepsy as described above through the end of year 2011. Chart review was done to confirm the diagnosis of narcolepsy and identify the date of narcolepsy symptom onset. Patients were first classified into one of three groups based on their status on the date of the diagnosis code: miscode, prevalent case of narcolepsy, or being evaluated for narcolepsy. Miscodes were patients for whom no evidence of a narcolepsy diagnosis or any symptoms suggestive of narcolepsy could be found in the medical record. Prevalent cases were patients who had a preexisting diagnosis of narcolepsy with symptom onset in the remote past, for example – prior to enrollment in the site, and whose narcolepsy symptom onset could not have occurred following receipt of one of the vaccines being studied. Patients in the third category were those being evaluated for symptoms for which narcolepsy was considered in the differential diagnosis by at least one provider.

Among the patients being evaluated for narcolepsy, we further classified each patient into one of the following diagnosis categories: narcolepsy with cataplexy, narcolepsy without cataplexy, unknown diagnosis, or not a case of narcolepsy. Narcolepsy with cataplexy and narcolepsy without cataplexy were defined according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2) diagnostic criteria.10 Each of these patients had been evaluated by a sleep medicine specialist in the course of routine clinical care; for the purposes of this investigation, one physician reviewed each patient’s medical record to determine if the ICSD-2 diagnostic criteria were met. ‘Unknown diagnosis’ was assigned to patients for whom narcolepsy was mentioned in the medical record as a possibility, but the patient either did not pursue definitive evaluation or was lost to follow-up. Patients who were evaluated for symptoms suggestive of narcolepsy but for whom a narcolepsy diagnosis was ruled out and an alternative diagnosis established were classified as ‘not a case of narcolepsy’. Narcolepsy symptom onset was defined as the earliest date of onset of either excessive daytime sleepiness or cataplexy, as reported by the patient and recorded in the medical record. If the symptom onset date occurred during the 180 days following influenza vaccination, the case was considered a post-vaccination case of narcolepsy.

We compared the observed number of post-vaccination cases to the number of cases expected to occur by chance alone based on the size and age distribution of the vaccinated cohort. The number of incident cases expected to occur was calculated by multiplying the enrolled person-time during the 180 days post-vaccination among individuals who received an influenza vaccine by the age-specific incidence rates from a published study that identified chart-confirmed narcolepsy cases in a US population using a similar case definition.11

To determine how often a health care visit with a first-ever narcolepsy ICD-9 code represented a chart-confirmed diagnosis of narcolepsy among vaccinated patients, we calculated the positive predictive value (PPV), which equals the number of chart-confirmed cases divided by the number of patients whose charts were reviewed.

We restricted our investigation to patients <30 years old because the initial reports of an association between narcolepsy and influenza vaccines in Europe involved persons <20 years old. This age group also has the highest baseline incidence of narcolepsy. Our vaccinated cohort analysis was done using data from six sites where chart review was available.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Institutional review boards at each VSD site approved this study and determined that informed consent was not required.

Results

Incidence of narcolepsy diagnosis in the population

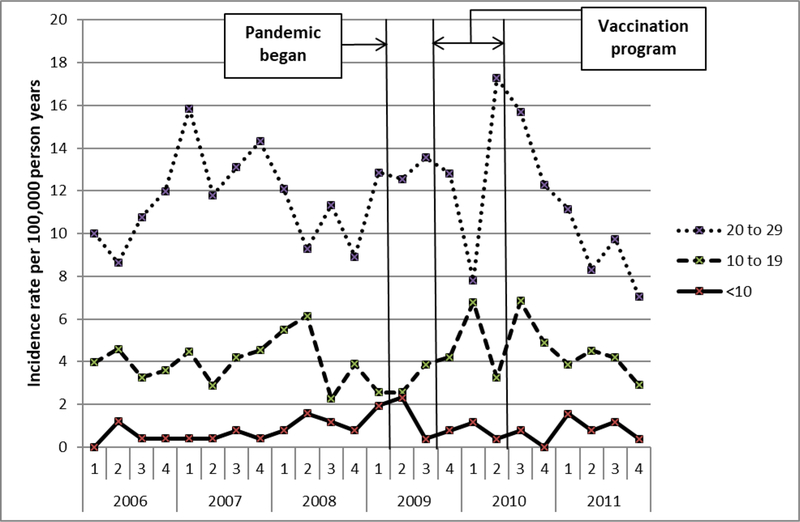

We identified 1,045 patients with an incident diagnosis code for narcolepsy. Figure 1 shows the incidence rate of narcolepsy diagnosis codes by quarter year for three age groups. The rate after the start of the pandemic is similar to the rate prior to the pandemic. Table 1 shows incidence rate ratios comparing the rates during each time period after the start of the pandemic to the pre-pandemic baseline rate. There was no significant change.

Figure 1.

Population incidence rate of narcolepsy diagnosis (first-ever narcolepsy ICD-9 diagnosis code in a patient’s record) for three age groups by quarter year, 2006–2011

Table 1.

Population incidence rate of narcolepsy diagnosis (first-ever narcolepsy ICD-9 diagnosis code in a patient’s record) by pandemic and non-pandemic time periods in the Vaccine Safety Datalink population, 2006–2011

| Age Group: | <10 years old |

10–19 years old |

20–29 years old |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | n | IR* | IRR (95%CI) | n | IR* | IRR (95%CI) | n | IR* | IRR (95%CI) |

| Jan 2006 – Mar 20091 | 26 | 0.79 | reference | 160 | 3.99 | reference | 366 | 11.63 | reference |

| Apr 2009 – Sep 20092 | 7 | 1.36 | 1.72 (0.69–3.83) | 20 | 3.22 | 0.81 (0.49–1.26) | 64 | 13.05 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) |

| Oct 2009 – Dec 20113 | 18 | 0.78 | 0.99 (0.53–1.80) | 128 | 4.61 | 1.16 (0.92–1.46) | 256 | 11.25 | 0.97 (0.82–1.13) |

| Apr 2009 – Dec 20114 | 25 | 0.88 | 1.12 (0.64–1.95) | 148 | 4.35 | 1.09 (0.87–1.37) | 320 | 11.57 | 0.99 (0.86–1.16) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IR = incidence rate; IRR = incidence rate ratio.

Incidence rate is expressed per 100,000 person years

Prepandemic

Pandemic, before vaccine available

After pandemic vaccine available

All pandemic and post-pandemic time included in the study

Vaccinated cohort

The number of patients vaccinated during the 2009 pandemic was 650,995 of which 96% were still enrolled at 180 days post-vaccination, 92% at 365 days post-vaccination, and 83% at the end of 2011. There were 870,530 vaccinated during the 2010–2011 season, of which 95% were still enrolled at 180 days post-vaccination and 88% at the end of 2011. The MIV manufacturers were: Sanofi Pasteur (67%), Novartis (19%), others (2%), unknown (12%). The 2010–2011 TIV manufacturers were: Sanofi Pasteur (43%), Novartis (26%), GSK (15%), others (5%), unknown (11%).

Seventy patients had a first-ever narcolepsy ICD-9 code following vaccination; chart review was completed for all of them. The patients were classified as follows: miscode (n=5), prevalent case of narcolepsy (n=19), and being evaluated for narcolepsy (n=46). Among the 46 patients being evaluated for narcolepsy, the diagnosis categories were as follows: incident diagnosis of narcolepsy with cataplexy (n=6), incident diagnosis of narcolepsy without cataplexy (n=10), unknown diagnosis (n=3), and not a case of narcolepsy (n=27). Table 2 shows characteristics by diagnosis categories, including the relationship between date of vaccination and date of symptom onset for the cases. For some cases, the date of symptom onset was either not documented or not stated precisely enough to determine the relationship to vaccination. None of these patients received a GSK influenza vaccine during the study period.

Table 2.

Characteristics of vaccinated-cohort narcolepsy cases by chart-confirmed diagnosis category

| Narcolepsy with cataplexy (n=6) | Narcolepsy without cataplexy (n=10) | Unknown diagnosis (n=3) | Total (n=19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | ||||

| 0 – 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 – 19 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| 20 – 29 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| Received influenza vaccine during: | ||||

| 2009 pandemic only | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| 2010–2011 season only | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Both | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Symptom onset in relation to receipt of vaccine | ||||

| Before A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccines available | 5 | 6 | 1 | 12 |

| Within 180 days post-MIV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Within 180 days post-MLAIV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Within 180 days post-2010–2011 TIV | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| More than 180 days post-MIV | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Not documented; received MIV | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Not documented; received MLAIV | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations: MIV = monovalent inactivated vaccine; MLAIV = monovalent live attenuated influenza vaccine; TIV = trivalent inactivated vaccine.

Among the sixteen cases with an incident diagnosis, none clearly had their symptom onset during the 180 days following receipt of an MIV or MLAIV vaccine, compared to 6.52 cases expected (Table 3). Two cases clearly had symptom onset during the 180 days following receipt of 2010–2011 TIV. The first patient was a 17 year old male who had onset of excessive daytime sleepiness 12 days after vaccination; he did not have cataplexy. The other case occurred in a 13 year old male with cataplexy whose symptom onset occurred between 120–180 days post-vaccination. The number of cases expected following TIV was 7.57.

Table 3.

Number of chart-confirmed narcolepsy cases with symptom onset during the 180 days post-vaccination observed versus expected in the Vaccine Safety Datalink population for the 2009 pandemic and 2010–2011 influenza season

| Vaccination Period | Vaccine | Age group, years | Number of people vaccinated | Expected Incidence Rate1 | Expected number of cases | Observed number of cases2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 pandemic | MIV | < 10 | 229,157 | 1.01 / 100,000 | 1.12 | 0 |

| 10 – 19 | 142,342 | 3.84 / 100,000 | 2.64 | 0 | ||

| 20 – 29 | 67,532 | 1.84 / 100,000 | 0.59 | 0 | ||

| subtotal | 439,031 | 4.35 | 0 | |||

| MLAIV | < 10 | 120,710 | 1.01 / 100,000 | 0.59 | 0 | |

| 10 – 19 | 79,936 | 3.84 / 100,000 | 1.48 | 0 | ||

| 20 – 29 | 11,318 | 1.84 / 100,000 | 0.10 | 0 | ||

| subtotal | 211,964 | 2.17 | 0 | |||

| Total | 650,995 | 6.52 | 0 | |||

| 2010–2011 influenza season | TIV | < 10 | 345,390 | 1.01 / 100,000 | 1.68 | 0 |

| 10 – 19 | 250,006 | 3.84 / 100,000 | 4.62 | 2 | ||

| 20 – 29 | 145,586 | 1.84 / 100,000 | 1.27 | 0 | ||

| subtotal | 740,982 | 7.57 | 2 | |||

| LAIV | < 10 | 81,410 | 1.01 / 100,000 | 0.40 | 0 | |

| 10 – 19 | 45,426 | 3.84 / 100,000 | 0.84 | 0 | ||

| 20 – 29 | 2,712 | 1.84 / 100,000 | 0.02 | 0 | ||

| subtotal | 129,548 | 1.26 | 0 | |||

| Total | 870,530 | 8.83 | 2 | |||

Abbreviations: LAIV = live attenuated influenza vaccine; MIV = monovalent inactivated vaccine; MLAIV = monovalent live attenuated influenza vaccine; TIV = trivalent inactivated vaccine.

Expected incidence rates are per 100,000 person-years; from Silber, et al.11

Chart-confirmed cases of narcolepsy with or without cataplexy and whose symptom onset date occurred during the 180 days following receipt of one of the vaccines listed in the table.

In European reports, the vast majority of narcolepsy case-patient’s symptoms began within six months (180 days) following vaccination.7, 12, 13 We also examined the 365 days post-vaccination interval: for the 2009 pandemic vaccines there were 2 cases (12.95 expected) and for the 2010–2011 seasonal vaccines there were 2 cases (17.24 expected). No cases had symptom onset more than 365 days post-vaccination.

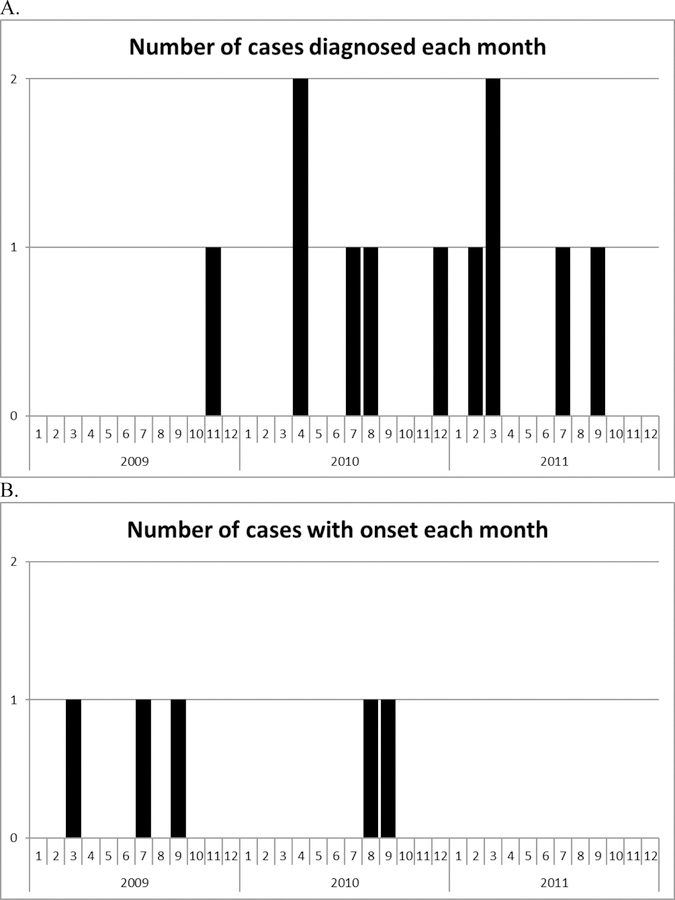

Among the sixteen chart-confirmed incident cases, the median age was 18 years (range 11 to 28). The sex distribution was nine male and seven female. The time between symptom onset and diagnosis ranged from 4 to 36 months among those ≤ 19 years old, and from 6 months to 17 years among those >19 years old. One case-patient had a history of influenza like illness recorded near to, but not clearly prior to, the time of narcolepsy symptom onset. Figure 2 shows the date of diagnosis and date of symptom onset among the incident cases who received either MIV or MLAIV. The distributions do not suggest a cluster of cases following the 2009 pandemic vaccination program.

Figure 2.

Number of chart-confirmed incident narcolepsy cases by date of diagnosis (A) and date of symptom onset (B) among patients that received either MIV or MLAIV during the 2009 pandemic. Includes chart-confirmed incident cases of narcolepsy with cataplexy and narcolepsy without cataplexy diagnosed following receipt of a 2009 pandemic vaccine (n=11). The date of symptom onset was prior to the year 2009 for five of the cases and was not documented for one case - these six cases are not shown in the lower graph (B).

The PPV of a first-ever narcolepsy ICD-9 code for a chart-confirmed incident diagnosis of narcolepsy was 23% (16/70) and for either an incident or prevalent diagnosis was 50% (35/70). All of the incident diagnoses were associated with visits to sleep medicine or neurology clinics. When the ICD-9 code was associated with a primary care clinic visit, it either represented a prevalent case [10/18 (56%)] or not a case [8/18 (44%)]. The PPV for an incident diagnosis was highest in the 10 to 19 year old age group [9/31 (29%)] compared to the 20–29 year old age group [7/35 (20%)] and the 0–9 year old group [0/4 (0%)].

Discussion

Epidemiologic investigations in several European countries have found an association between Pandemrix (an adjuvanted influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine) and narcolepsy. An increased relative risk (RR) of narcolepsy in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated children and adolescents was found in Finland (RR = 12.7),7 Sweden (RR = 2.92),14 Ireland (RR = 13.9),13 and Norway (RR=10).15 An increased risk with vaccination was also found in England [odds ratio (OR) = 14.4]12 and France (OR = 6.5).16 A case-control study that pooled data from eight European countries found an increased risk in an analysis anchored on the date of narcolepsy symptom onset.17 We investigated whether a similar association could exist with the pandemic influenza vaccines that were used in the US.

In our vaccinated cohort analysis, we found fewer chart-confirmed cases of narcolepsy with symptom onset in the six months following receipt of influenza vaccine than would have been expected by chance alone. We based our expected number of cases on the only chart-confirmed incidence rate estimates published to date,11 which might not reflect the baseline incidence in our study population. However, even if we assumed the true baseline incidence was one order of magnitude less, the zero cases observed in our 2009 pandemic vaccinated cohort would still be less than the 0.652 cases expected. In Finland, the incidence of narcolepsy observed among vaccinated people 0–19 years old was 9 per 100,000 person years.7 If that rate existed in our 2009 pandemic vaccinated cohort, we should have observed 16 cases just among the patients aged 0–19 years who received MIV, whereas we actually observed zero cases.

Three of our patients had an ‘unknown diagnosis’ despite chart-review. One had sleep related symptoms that clearly pre-dated the availability of the 2009 pandemic vaccine. The timing of symptom onset for the other two cases was not documented, but even assuming that these two patients actually had narcolepsy and that their symptom onset was following vaccination, the observed number of cases would still be less than expected. The patterns observed among the chart-confirmed cases identified in our population were quite different from the patterns observed in Europe. The cases diagnosed among our vaccinated cohort were characterized by a long duration of excessive daytime sleepiness prior to presentation with the resulting typical lengthy delay between symptom onset and the final diagnosis of narcolepsy. In contrast, the post-vaccination cases identified in Europe were characterized by abrupt symptom onset and relatively rapid diagnosis. Only 38% of our incident cases had cataplexy, which is similar to historical rates and also contrasts markedly with the experience in Finland where 94% of post-vaccination cases had cataplexy.18

Some European countries subsequently also reported an increased risk following vaccination in adults up to age 40, though the risk was smaller than the risk among those <20 years old.14, 16, 19 We did not observe an increased risk among those aged 20–29 years. While we did not investigate persons ≥30, it is unlikely that an increased risk would exist in that age range when no increase was observed in the younger age groups.

There are at least two reasons why influenza vaccination could have been associated with an increased risk of narcolepsy in some countries but not in the US. First, the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccines used in the US were different from Pandemrix, the vaccine used in the countries reporting an increased risk. Pandemrix was manufactured by GSK; no GSK pandemic vaccine was used in the US. Pandemrix contained the AS03 adjuvant.20 An adjuvant enhances the immune system’s response to the antigens contained in a vaccine. An adjuvant-containing vaccine could have a different adverse event profile than a non-adjuvanted vaccine containing the same antigens. No adjuvanted influenza vaccines were used in the US. The second factor to consider is the proportion of individuals in a population who are susceptible to developing narcolepsy. Narcolepsy with cataplexy has a strong association with the HLA DQB1*0602 allele, suggesting that it occurs in genetically susceptible individuals.21 The frequency of this allele varies between populations.22 A study in the US found the DQB1*0602 allele to be less frequent among Asian/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics than among Caucasians,23 and the frequency varies between different Caucasian populations as well. Other HLA alleles might also affect susceptibility.24 The US has a more heterogeneous population than Northern European countries, therefore, the proportion of the US population that is susceptible to developing narcolepsy with cataplexy may be lower than in the countries where an association with vaccine has been observed.

Narcolepsy with cataplexy is caused by the loss of hypothalamic neurons that produce the neuropeptide hypocretin.1 This loss is thought to result from an autoimmune process. Influenza antigen, either from natural infection or vaccine, has been suggested as a possible trigger of the autoimmune response.25 The role for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 infection as a potential trigger for narcolepsy has been suggested based on the results of a non-population-based study in a single specialty clinic in Beijing, China where a 3-fold increase in the number of narcolepsy cases was observed beginning approximately six months following the peak of pandemic influenza activity; among those cases, 94% occurred in unvaccinated individuals.26 However, the epidemiologic evidence from other countries has not been consistent with an increase in narcolepsy following the 2009 pandemic. In South Korea, where a non-adjuvanted influenza vaccine was used for those age 0–18 years, the rate of narcolepsy diagnosis decreased following the start of the pandemic.27 A European study found a large increase in diagnosis rates among 5–19 year olds in Finland and Sweden (where adjuvanted vaccine coverage was high) but not in three other countries where adjuvanted vaccine coverage was low.28 In our study, the population incidence rate of narcolepsy diagnosis did not show any significant changes following the start of the 2009 influenza pandemic or the pandemic vaccination program, which achieved an approximately 28% vaccination rate in the 5 to 17 year old age group.29 Our results do not suggest an association of either influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination or natural infection with a change in the rates of narcolepsy, though this type of ecologic analysis must be interpreted with caution. First, as described in the literature, the date of narcolepsy diagnosis does not represent the date of narcolepsy symptom onset.3 Our chart-reviewed analysis showed the time from symptom onset to diagnosis for individuals with confirmed narcolepsy ranged from 4 months to 17 years. Second, in our study population, many first-ever narcolepsy diagnosis codes do not represent an incident diagnosis of chart-confirmed narcolepsy, particularly in the older age group.

The role that influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 antigens might have played in causing the increase in narcolepsy observed in some countries has not yet been determined. The lack of an increase in incidence in our study and in other countries that did not use the AS03 adjuvanted Pandemrix vaccine suggests that other factors are involved. Other factors that have been suggested include the adjuvant or differences between vaccines in the manufacturing process for viral inactivation.25, 30

Our findings do not suggest an association between influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-containing vaccines used in the US and narcolepsy. Our investigation included both the inactivated and the live attenuated 2009 monovalent pandemic vaccines and the 2010–2011 seasonal influenza vaccines, which also contained the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus strain. Vaccination with the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine viral antigens does not appear to be sufficient by itself to increase the incidence of narcolepsy in a population.

Acknowledgements

The following individuals contributed to the data collection for this study: Patti Benson, Jennifer Covey, Group Health Cooperative (Seattle, WA); Katherine M. Burniece, Komal J. Narwaney, Kaiser Permanente Colorado (Denver, CO); Ajit deSilva, Karen Forsen, Cat Magallon, Margarita Magallon, Paula Ray, Pat Ross, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (Oakland, CA); Stephanie Irving, Jill Mesa, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (Portland, OR); Cheryl Mercado, Jackie Porcel, Zendi Solano, Lina Sy, Kaiser Permanente Southern California (Pasadena, CA); Melisa Rett, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care and Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (Boston, MA); Leslie Kuckler, Laurie VanArman, HealthPartners (Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN); Tara L. Johnson, Jennifer P. King, Marshfield Clinic (Marshfield, WI).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding: This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No external funding was obtained for this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ahmed I, Thorpy M. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy. Clinics in chest medicine 2010;31:371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longstreth WT Jr., Koepsell TD, Ton TG, Hendrickson AF, van Belle G. The epidemiology of narcolepsy. Sleep 2007;30:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrish E, King MA, Smith IE, Shneerson JM. Factors associated with a delay in the diagnosis of narcolepsy. Sleep Med 2004;5:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The MPA investigates reports of narcolepsy in patients vaccinated with Pandemrix [online] Available at: http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/english/All-news/NYHETER-2010/The-MPA-investigates-reports-of-narcolepsy-in-patients-vaccinated-with-Pandemrix/. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 5.National Institute for Health and Welfare recommends discontinuation of Pandemrix vaccinations [online] Available at: http://www4.thl.fi/en_US/web/en/pressrelease?id=22930. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 6.Statement on narcolepsy and vaccination [online] Available at: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/committee/topics/influenza/pandemic/h1n1_safety_assessing/narcolepsy_statement/en/. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 7.Nohynek H, Jokinen J, Partinen M, et al. AS03 adjuvanted AH1N1 vaccine associated with an abrupt increase in the incidence of childhood narcolepsy in Finland. PLoS One 2012;7:e33536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC statement on narcolepsy following Pandemrix influenza vaccination in Europe [online] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Concerns/h1n1_narcolepsy_pandemrix.html. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 9.Baggs J, Gee J, Lewis E, et al. The Vaccine Safety Datalink: a model for monitoring immunization safety. Pediatrics 2011;127 Suppl 1:S45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billiard M Diagnosis of narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia. An update based on the International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd edition. Sleep medicine reviews 2007;11:377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silber MH, Krahn LE, Olson EJ, Pankratz VS. The epidemiology of narcolepsy in Olmsted County, Minnesota: a population-based study. Sleep 2002;25:197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller E, Andrews N, Stellitano L, et al. Risk of narcolepsy in children and young people receiving AS03 adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccine: retrospective analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Flanagan D, Barret AS, Foley M, et al. Investigation of an association between onset of narcolepsy and vaccination with pandemic influenza vaccine, Ireland April 2009-December 2010. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2014;19:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson I, Granath F, Askling J, Ludvigsson JF, Olsson T, Feltelius N. Risks of neurological and immune-related diseases, including narcolepsy, after vaccination with Pandemrix: a population- and registry-based cohort study with over 2 years of follow-up. Journal of internal medicine 2014;275:172–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heier MS, Gautvik KM, Wannag E, et al. Incidence of narcolepsy in Norwegian children and adolescents after vaccination against H1N1 influenza A. Sleep Med 2013;14:867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, Lecendreux M, et al. Increased risk of narcolepsy in children and adults after pandemic H1N1 vaccination in France. Brain : a journal of neurology 2013;136:2486–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narcolepsy in association with pandemic influenza vaccination (a multi-country European epidemiological investigation) Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partinen M, Saarenpaa-Heikkila O, Ilveskoski I, et al. Increased incidence and clinical picture of childhood narcolepsy following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination campaign in Finland. PLoS One 2012;7:e33723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Increased risk of narcolepsy observed also among adults vaccinated with Pandemrix in Finland [online] Available at: http://www4.thl.fi/en_US/web/en/pressrelease?id=33516. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 20.Garcon N, Vaughn DW, Didierlaurent AM. Development and evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System containing alpha-tocopherol and squalene in an oil-in-water emulsion. Expert review of vaccines 2012;11:349–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black JL 3rd. Narcolepsy: a review of evidence for autoimmune diathesis. International review of psychiatry 2005;17:461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Allele Frequency Net Database [online] Available at: http://allelefrequencies.net/. Accessed 07/15/2014.

- 23.Maiers M, Gragert L, Klitz W. High-resolution HLA alleles and haplotypes in the United States population. Human immunology 2007;68:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mignot E, Lin L, Rogers W, et al. Complex HLA-DR and -DQ interactions confer risk of narcolepsy-cataplexy in three ethnic groups. American journal of human genetics 2001;68:686–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partinen M, Kornum BR, Plazzi G, Jennum P, Julkunen I, Vaarala O. Narcolepsy as an autoimmune disease: the role of H1N1 infection and vaccination. Lancet neurology 2014;13:600–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han F, Lin L, Warby SC, et al. Narcolepsy onset is seasonal and increased following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in China. Ann Neurol 2011;70:410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choe YJ, Bae GR, Lee DH. No association between influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination and narcolepsy in South Korea: An ecological study. Vaccine 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Wijnans L, Lecomte C, de Vries C, et al. The incidence of narcolepsy in Europe: Before, during, and after the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic and vaccination campaigns. Vaccine 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lee GM, Greene SK, Weintraub ES, et al. H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccine safety in the vaccine safety datalink project. American journal of preventive medicine 2011;41:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed SS, Schur PH, MacDonald NE, Steinman L. Narcolepsy, 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic influenza, and pandemic influenza vaccinations: what is known and unknown about the neurological disorder, the role for autoimmunity, and vaccine adjuvants. Journal of autoimmunity 2014;50:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]