Abstract

Detecting and correcting errors is essential to successful action. Studies on response monitoring have examined scalp event-related potentials (ERPs) following the commission of motor slips in speeded-response tasks, focusing on a frontocentral negativity (i.e., error-related negativity or ERN). Sensorimotor neurophysiologists investigating cortical monitoring of reactive balance recovery behavior observe a strikingly similar pattern of scalp ERPs following externally imposed postural errors, including a brief frontocentral negativity that has been referred to as the balance N1. We integrate and review relevant literature from these discrepant fields to suggest shared underlying mechanisms and potential benefits of collaboration across fields. Unlike the cognitive tasks leveraged to study the ERN, balance perturbations afford precise experimental control of postural errors to elicit balance N1s that are an order of magnitude larger than the ERN and drive robust and well-characterized adaptation of behavior within an experimental session. Many factors that modulate the ERN, including motivation, perceived consequences, perceptual salience, expectation, development, and aging are likewise known to modulate the balance N1. We propose that the ERN and balance N1 reflect common neural activity for detecting errors. Collaboration across fields could help clarify the functional significance of the ERN, and poorly understood interactions between motor and cognitive impairments.

1. Error-related negativity

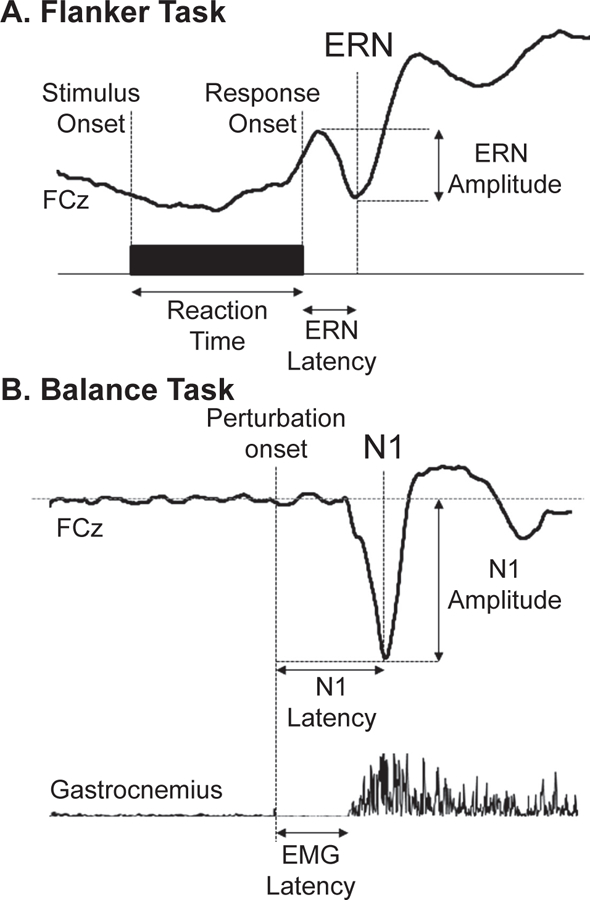

For nearly three decades, psychophysiologists have studied a specific neural response to error commission, referred to as the error-related negativity (ERN or Ne; (Falkenstein, Hohnsbein, Hoormann, & Blanke, 1990; Gehring, Goss, Coles, Meyer, & Donchin, 1993, 2018)). The ERN is elicited when participants make errors (i.e., motor slips) in forced-choice speeded-response tasks. The most common tasks that have been used to elicit and study the ERN are variations on the Flankers task, Stroop task, and Go/No-go tasks (Meyer, Riesel, & Proudfit, 2013), which involve basic stimulus-response pairs that are verbally explained at the beginning of the task, e.g. “when you see stimulus A, press response button 1.” Although the tasks are relatively simple, participants make mistakes on a small percentage of trials. By having participants perform hundreds of trials while recording electroencephalographic (EEG) activity, it is possible to evaluate event-related brain potentials (ERPs) time-locked to errors compared to correct responses. The ERN is observed as a sharp negative peak within the first 100ms of the ERP following incorrect response commission at frontocentral EEG electrodes (Fz, FCz, or Cz) (Gehring et al., 1993). Figure 1A shows the ERN evoked by errors in a Flankers task from Marlin et al. (Marlin, Mochizuki, Staines, & McIlroy, 2014).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the error-related negativity (ERN) and balance N1, collected in the same recording session in N = 11 healthy young adults (8 female) from Marlin et al. 2014. (A) ERN evoked by errors in an arrow Flankers Task. (B) N1 evoked by sudden release of a cable supporting a portion of body weight from an upright leaning posture. This figure is republished from Marlin et al. 2014 with permission from the Journal of Neurophysiology.

The ERN appears to reflect activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and/or the supplementary motor area based on extracranial EEG (Dehaene, Posner, & Tucker, 1994; Gentsch, Ullsperger, & Ullsperger, 2009; Marlin et al., 2014; Miltner, Braun, & Coles, 1997), intracranial EEG (Bonini et al., 2014), functional magnetic resonance imaging (Badgaiyan & Posner, 1998; Carter et al., 1998; Hauser et al., 2014) and magnetoencephalography studies (Miltner et al., 2003). The ERN is thought to represent the activation of a generic neural system for error detection because it is relatively consistent across different tasks (Meyer et al., 2013; Riesel, Weinberg, Endrass, Meyer, & Hajcak, 2013) and responding limbs (Holroyd, Dien, & Coles, 1998). Theoretical and computational models suggest that the ERN reflects detection of errors, situations conducive to errors (Carter et al., 1998; Kerns et al., 2004; Ullsperger & von Cramon, 2001; van Veen, Cohen, Botvinick, Stenger, & Carter, 2001; Yeung, Botvinick, & Cohen, 2004), or unexpected events (Alexander & Brown, 2011) to recruit cognitive control to improve behavior (Holroyd & Coles, 2002b; Ridderinkhof, Ullsperger, Crone, & Nieuwenhuis, 2004; Shackman et al., 2011; Ullsperger, Danielmeier, & Jocham, 2014). That is, theories of the ERN generally suggest it is functionally linked to posterror adaptation. However, observable changes in behavior accompanying errors in the tasks most commonly used to study ERN are limited to less forceful entry of errors compared to correct responses, subsequent entry of the correct response on the same trial, slower reaction time on subsequent trials, and increased probability of responding correctly on the next trial (Dutilh et al., 2012; Gehring et al., 1993). Thus, behavioral changes include differences in error-related responses or posterror performance measures.

Although the amplitude of the ERN has been correlated with changes in behavior after errors (Gehring et al., 1993; Ullsperger et al., 2014), a number of experimental factors limit the ability to rigorously test adaptive hypotheses of the ERN. Primarily, reliance on subjects to sporadically commit errors limits experimental control over error frequency, timing, and sequencing. Additionally, discrete classification of responses as either overtly correct or erroneous limits the ability to observe continuous behavioral adaptation within subjects. Although some groups have begun to assess partial errors in the form of muscle activation in the nonresponding limb in trials with an overtly correct response (Spieser, van den Wildenberg, Hasbroucq, Ridderinkhof, & Burle, 2015), adaptation in these tasks is typically estimated as an increasing probability of an overtly correct response on subsequent trials (Gehring et al., 1993), rather than being directly measured in terms of incremental progress (e.g., skill acquisition toward the development of expertise within individuals (Shadmehr, Smith, & Krakauer, 2010)). Given that accuracy often exceeds 90% in these simple tasks, the odds of a correct response following an error would be quite high even in the absence of behavioral adaptation. While it is possible to observe incremental changes in response latency across trials within individuals, it is unclear if behavioral changes such as posterror slowing after errors in speeded-response tasks actually reflect control-related processes, or rather, orienting responses to infrequent events (Dutilh et al., 2012; Notebaert et al., 2009; Wessel, 2018; Wessel & Aron, 2017). Further, whether such orienting responses increase (Houtman & Notebaert, 2013) or decrease (Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001) the likelihood of errors on subsequent trials depends on, and is thus confounded by, the duration of inter-trial-intervals (Jentzsch & Dudschig, 2009; Wessel, 2018). A more complex behavioral task providing better experimental control and the presence of robust behavioral adaptation could overcome these limitations to facilitate a more mechanistic investigation of the ERN in relation to posterror changes in behavior.

2. Balance perturbations and the balance N1

Reactive balance recovery following externally imposed balance errors provides greater experimental control over errors than tasks typically used to elicit the ERN. Reactive balance recovery can be evoked by a variety of physical perturbations imposing errors on whole body posture, including shove (Adkin, Quant, Maki, & McIlroy, 2006) or release (Mochizuki, Boe, Marlin, & McIlRoy, 2010) perturbations of the upper torso, as well as tilts (Ackermann, Diener, & Dichgans, 1986) or translations of the floor during standing (Welch & Ting, 2009), walking (Dietz, Quintern, & Berger, 1985b), or sitting (Mochizuki, Sibley, Cheung, Camilleri, & McIlroy, 2009a; Staines, McIlroy, & Brooke, 2001). In contrast to cognitive paradigms that rely on subjects to sporadically commit errors, perturbation devices can be used to precisely control the type, frequency, extent, and sequencing of balance perturbations, which can be repeated across subjects (Adkin et al., 2006; Welch & Ting, 2008, 2009, 2014). In each case, a rapid and highly motivated motor reaction is necessary to prevent a fall or possible bodily harm. The earliest balance-correcting muscle activity, called the automatic postural response, is an involuntary behavior mediated by brainstem sensorimotor circuits (Carpenter, Allum, & Honegger, 1999; Jacobs & Horak, 2007a), which can be predicted in fine detail from movement-based error trajectories, i.e. the deviation of the body from the upright, standing position (Welch & Ting, 2008, 2009). In this way, balance recovery is an ecologically relevant error-correcting behavior that evokes error-related and error-correcting muscle activity. And most importantly, balance perturbations evoke an error-related scalp ERP resembling the ERN, that has been referred to as the balance N1. Figure 1B shows the balance N1 evoked by sudden release of a cable supporting a portion of body weight from an upright leading posture from Marlin et al. (Marlin et al., 2014).

Motor reactions to balance perturbations have been well-characterized as rapidly adapting error-driven responses. Balance performance error can be measured by the position, velocity, and acceleration of the body’s center of mass relative to the feet, which serve as three error signals that simultaneously evoke balance-correcting muscle activations (Figure 2A; (Lockhart & Ting, 2007; Welch & Ting, 2008, 2009)). Sensitivities to each of these error signals can vary independently and substantially within a range of solutions that are sufficient to generate forces to correct balance errors, and differences in these sensitivities can parsimoniously explain apparently complex differences in balance-correcting motor responses between individuals (Figure 2ABC; (Welch & Ting, 2008, 2009)). These error sensitivities can adapt on a trial-by-trial basis within an experimental session toward optimal solutions that can be predicted through physics (Welch & Ting, 2014). Such adaptation can also occur over motor rehabilitation, as demonstrated by an increase in sensitivity to velocity and position errors in cats when the sensory afferents encoding acceleration error were damaged by pyridoxine overdose (Lockhart & Ting, 2007). The mechanisms underlying such changes in error-sensitivities remain unclear, but a better understanding could facilitate rehabilitation of balance disorders.

Figure 2.

Kinematic error signals define the balance-correcting motor response to perturbation. (A) Recorded center of mass kinematics (top) are multiplied by subject- and muscle-specific error sensitivities, added together, clipped below zero, and delayed 100ms (middle) to reconstruct recorded balance-correcting EMG response (bottom). (B) Different kinematic error sensitivities can explain differences in balance-correcting EMG between subjects responding to the same perturbation. (C) Changes in sensitivity to acceleration error (top) primarily influences the initial burst of the balance-correcting response, whereas changes in sensitivity to velocity (middle) or position errors (bottom) influence later portions of the response due to the relative peak timings of the error signals. Data in this figure is republished from Welch and Ting 2008 with permission from the Journal of Neurophysiology.

In addition to error-related and error-correcting muscle activity, balance perturbations elicit error-related cortical activity resembling the ERN (Figure 1). Specifically, a frontocentral negativity called the balance N1 is evoked simultaneous to the balance-correcting muscle activity (Payne, Hajcak, & Ting, 2018). The balance N1 is a negative peak of cortical activity occurring between 100–200ms after balance perturbation at frontal and central midline EEG electrodes (Fz, FCz, Cz) (Marlin et al., 2014; Mierau, Hulsdunker, & Struder, 2015), with amplitudes large enough to observe on single trials (Mierau et al., 2015; Payne et al., 2018). The balance N1 has been localized to the supplementary motor area (Marlin et al., 2014; Mierau et al., 2015), but theories of its function are extremely limited. The balance N1 was initially thought to reflect sensory activity from balance perturbations (Dietz, Quintern, & Berger, 1984b; Dietz et al., 1985b; Dietz, Quintern, Berger, & Schenck, 1985a). However, the absence of the balance N1 when perturbations are predictable (Adkin et al., 2006) suggests that the balance N1 may represent an error-signal similar to the ERN. In fact, many factors known to modulate the ERN, including motivation, perceived consequence, perceptual salience, expectation, development, and aging are likewise known to modulate the balance N1 (Section 3). If the balance N1 and ERN are manifestations of a common neural system for error detection, sensorimotor perturbations may present a more controllable experimental paradigm to study the relationship between errors, the action monitoring system, and subsequent changes in behavior (Section 4).

3. Parallels between Balance N1 and ERN

The previous sections defined the ERN and balance N1 as frontocentral negativities time-locked to an error event, which have largely overlapping scalp distributions (Figure 3) and sources localized to the medial frontal cortex (Marlin et al., 2014). In this section, we describe parallel outcomes of investigations of the balance N1 and the ERN to support the argument that these brain responses reflect similar functions of the action monitoring system, and in the following section we conclude with the suggestion that collaboration across fields could overcome barriers to progress in both fields. One apparent contrast is that the ERN is typically quantified within the first 100ms of the response-locked ERP waveform whereas the balance N1 is typically quantified in the second 100ms of the stimulus-locked ERP waveform. However, in tasks that elicit the ERN, the onset of muscle activity associated with the erroneous response entry can be observed 100ms before the response button is pressed (Spieser et al., 2015). Thus, if the ERN were quantified relative to the onset of the error event rather than completion of the error event, its timing would be more aligned with the timing of the balance N1 relative to the onset of perturbation acceleration. In other words, both the balance N1 and ERN could be equivalently quantified within the second 100ms relative to the onset of an error, whether the error is internally generated, as in the case of the ERN, or externally applied, as in the case of the balance N1. Much like the ERN, which displays a similar scalp distribution whether responses are entered by the hand or foot (Holroyd et al., 1998), or even by the eyes (Endrass, Reuter, & Kathmann, 2007; Nieuwenhuis, Ridderinkhof, Blom, Band, & Kok, 2001; Van’t Ent & Apkarian, 1999), the balance N1 displays a similar scalp distribution regardless of whether perturbations are delivered during standing or sitting (Mochizuki et al., 2009a), consistent with a generic system for error detection.

Figure 3.

Scalp distributions of the error-related negativity (ERN) and balance N1, collected in the same recording session in N = 11 healthy young adults (8 female) from Marlin et al. 2014. (A) Scalp distribution of the ERN evoked by errors in an arrow Flankers Task. (B) Scalp distribution of the N1 evoked by sudden release of a cable supporting a portion of body weight from an upright leaning posture. This figure is republished from Marlin et al. 2014 with permission from the Journal of Neurophysiology.

Larger and more intense balance perturbations elicit a larger balance N1 response (Mochizuki et al., 2010; Payne et al., 2018; Staines et al., 2001). Likewise, the ERN increases in amplitude with the extent of an error, such as when an error is committed with both the wrong finger and the wrong hand compared to errors committed with either the wrong finger or the wrong hand (Bernstein, Scheffers, & Coles, 1995). The balance N1 also decreases in amplitude when sensory input is partially blocked by tendon vibration (Staines et al., 2001), or when sensory input is naturally suppressed during walking (Dietz et al., 1985b). These data are similar to observed reductions in the amplitude of the ERN in a visual two-choice reaction task under degraded stimulus conditions (Scheffers & Coles, 2000). In contrast to the balance N1 studies that directly altered the sensory experience of the error, the degraded visual stimulus condition in Scheffers and Coles (2000) altered the representation of the error by making subjects more uncertain about the identity of the appropriate response. In either case the error-related cortical response was influenced by altering the perceptual intensity of the information necessary to compare the actual and desired events, thereby implicating some dependency on the sensory manifestation of the error-related stimulus.

The balance N1 and the ERN both scale in amplitude with the perceived consequence of an error. The balance N1 is increased in amplitude when a balance failure would be more significant, such as when the participant is perturbed at an elevated height (Adkin, Campbell, Chua, & Carpenter, 2008; Sibley, Mochizuki, Frank, & McIlroy, 2010). In this case, the externally applied force of the perturbation is the same, but the change in context from standing at ground level to standing at the edge of an elevated platform increases the perceived consequences of a possible balance failure and increases the amplitude of the balance N1. The ERN likewise increases when an error is perceived as more significant, e.g. when an error incurs a higher monetary loss (Hajcak, Moser, Yeung, & Simons, 2005a; Pailing & Segalowitz, 2004a) or when the participant is informed that their performance is being evaluated and judged (Hajcak et al., 2005a; Kim, Iwaki, Uno, & Fujita, 2005). Interestingly, the elevated height perturbation context also increased self-reported level of anxiety and worry about falling (Adkin et al., 2008), which aligns with findings of higher ERN amplitudes in individuals with greater general anxiety and worry (Hajcak, McDonald, & Simons, 2003), which may modulate the perceived consequences of errors. These studies suggest that the balance N1 and ERN depend not only on the sensory phenomena of errors, but also on the cognitive valuation of the perceived consequences of balance perturbations and errors, respectively.

The balance N1 is reduced in amplitude when a participant’s attention is diverted from a balance task by performing a simultaneous visuomotor tracking task (Quant, Adkin, Staines, Maki, & McIlroy, 2004b) or visual working memory task (Little & Woollacott, 2015). Likewise, ERN amplitude is reduced when a participant’s attention is diverted from the primary speeded-response task by simultaneous performance of an interleaved visual working memory task (Klawohn, Endrass, Preuss, Riesel, & Kathmann, 2016; Maier & Steinhauser, 2017) or while simultaneously listening to a series of numbers for a particular sequence (Pailing & Segalowitz, 2004b). These studies suggest that the amplitude of both the balance N1 and the ERN are modulated by the availability of cognitive resources.

When a balance perturbation is predictable in timing, magnitude, and direction, the balance N1 amplitude is substantially reduced (Mochizuki et al., 2010) or even absent (Adkin et al., 2008; Adkin et al., 2006). Along similar lines, an unexpected balance perturbation in a different direction following a series of predictable perturbations elicits a large balance N1 (Adkin et al., 2008; Adkin et al., 2006). Additionally, self-initiated balance perturbations elicit smaller balance N1s than those initiated by an experimenter (Dietz et al., 1985a; Mochizuki, Sibley, Cheung, & McIlroy, 2009b; Mochizuki, Sibley, Esposito, Camilleri, & McIlroy, 2008). These data suggest that the balance N1 scales with predictability and are consistent with observations that ERN amplitude is larger when errors are less frequent and therefore more unexpected (Holroyd & Coles, 2002b; Santesso, Segalowitz, & Schmidt, 2005). Collectively, these studies suggest a parallel potentiation of ERN when errors are more infrequent and unexpected and balance N1 when perturbations are unexpected.

The balance N1 evoked by whole body perturbations increases in amplitude from early childhood (Berger, Quintern, & Dietz, 1987) and declines in amplitude with old age (Duckrow, Abu-Hasaballah, Whipple, & Wolfson, 1999). This developmental trajectory is similar to that of the ERN, which has also been observed to increase in amplitude from childhood to adolescence, plateauing in adulthood (Ladouceur, Dahl, & Carter, 2007; Santesso & Segalowitz, 2008; Tamnes, Walhovd, Torstveit, Sells, & Fjell, 2013; Wiersema, van der Meere, & Roeyers, 2007) and declining with old age (Beste, Willemssen, Saft, & Falkenstein, 2009; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2002). However, increases in ERN amplitude from childhood to adulthood are often confounded by a reduction in error frequency (Ladouceur et al., 2007; Santesso & Segalowitz, 2008; Wiersema et al., 2007), making it unclear whether the increase in ERN amplitude from childhood to adulthood is due to age or increased unexpectedness of errors due to performance improvement. However, when comparing younger adults to older adults, errors continue to become less frequent while the ERN amplitude declines (Beste et al., 2009; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2002), suggesting there are indeed changes in ERN amplitude with age that do not depend on changes in error rate.

Time-frequency analyses of the ERN (Luu, Tucker, & Makeig, 2004) and balance N1 (Peterson & Ferris, 2018; Varghese et al., 2014) have been used to suggest that both of these ERPs may reflect a transient synchronization of theta frequency (4–7 Hz) brain activity. However, in simulated datasets, such analyses are unable to distinguish synchronization of oscillatory components from discrete component peaks (Yeung, Bogacz, Holroyd, Nieuwenhuis, & Cohen, 2007). The extent to which these ERPs relate to theta frequency brain activity observed in other contexts remains unclear. Although theta power and ERN amplitudes are similarly modulated by novelty, conflict, and error within subjects (Cavanagh, Zambrano-Vazquez, & Allen, 2012), theta power and ERN amplitude can be relatively independent individual difference measures (Cavanagh, Meyer, & Hajcak, 2017). Whether the balance N1 evoked by postural perturbations is mechanistically related to continuous theta frequency brain activity observed in continuous balance tasks (Hulsdunker, Mierau, Neeb, Kleinoder, & Struder, 2015; Sipp, Gwin, Makeig, & Ferris, 2013) remains unclear, but presents another interesting area of future investigation and integration.

On the basis of these parallels, we propose that the balance N1 and the ERN reflect similar functions of the action monitoring system and suggest that balance and other sensorimotor perturbation paradigms could be leveraged to probe neural mechanisms of error detection and behavioral adaptation. While anatomical studies have suggested that the ERN reflects activity within a cortical node of cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits (Ullsperger et al., 2014), the balance N1 may likewise reflect activity within a cortical node of parallel or overlapping cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits, which are known to be highly parallel in nature and are suspected to perform similar functions based on detailed anatomical studies in animals (Alexander, DeLong, & Strick, 1986). In particular, the possible differences in localization of the ERN to the anterior cingulate cortex and the balance N1 to the supplementary motor area (Marlin et al., 2014) provides further support for the possibility that these ERPs may arise from the aforementioned parallel circuits, as the anterior cingulate cortex represents the cortical node of the so called “cognitive loop” of the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit and the supplementary motor area represents the cortical node of the so called “motor loop” of the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit (Alexander et al., 1986). However, these differences in localization may also be influenced by differences in overlap between the ERN or balance N1 and associated stimulus-locked visual or proprioceptive and vestibular ERPs respectively (Hajcak, Vidal, & Simons, 2004). If the balance N1 is a perturbation-elicited ERN, the experimental control and robust adaptation within balance paradigms could be leveraged to test adaptive hypotheses of the ERN, and theoretical and computational models of the ERN could be leveraged to design mechanistic investigations of the balance N1. Further, collaboration across fields could reveal interactions between motor and cognitive impairments, as well as cross-modal and synergistic benefits seen in combined motor and cognitive rehabilitation interventions.

4. Summary and Future Directions

Detecting and correcting errors is essential to successful behavior. By error, we refer to any deviation from a desired or expected goal or bodily state, which can be recognized by the nervous system as the impetus to modify behavior to achieve the desired state or goal. Although a perturbation does not reflect commission of a motor error, it produces a deviation from the desired upright posture that must be rapidly detected and corrected to prevent bodily harm. In this way, we believe that balance perturbations recruit many of the same control processes that are recruited by commission of motor errors, which is supported by a range of parallel influences on scalp ERPs described in the preceding section. Because of the similarities between error-correcting motor responses to balance perturbations and error-correcting motor responses in perturbations to the arms during voluntary movement (Crevecoeur & Kurtzer, 2018), it is possible that these cortical responses would generalize more broadly across sensorimotor control paradigms.

In contrast to cognitive paradigms that rely on subjects to sporadically commit errors, perturbation devices can be used to precisely control the type, frequency, extent, and sequencing of errors, which can be repeated both within and across subjects (Adkin et al., 2006; Welch & Ting, 2008, 2009, 2014) across a wide range of ages (Berger et al., 1987; Duckrow et al., 1999). Prediction or expectation errors can also be controlled in sensorimotor paradigms by altering verbal instructions or sequencing of perturbations, e.g. by providing a series of perturbations that are predictable in timing, direction, and magnitude, and manipulating any of these dimensions on selected “catch” trials (Adkin et al., 2006; Welch & Ting, 2014). In addition, it is also possible to examine outcome errors, e.g. by instructing a subject to recover balance without stepping in perturbations large enough to guarantee stepping reactions (Chvatal & Ting, 2012; McIlroy & Maki, 1993). It is therefore possible to leverage precise control over sensorimotor errors to experimentally isolate factors for a more detailed understanding of how each aspect of errors influences cortical activity. In turn, leveraging knowledge of the ERN to design sensorimotor perturbation experiments could be a major step toward identifying the functional role of cortical action monitoring on adaptation of sensorimotor behaviors.

Given the parallel outcomes of investigations of the ERN and the balance N1, several questions arise from the ERN literature that have yet to be tested of the balance N1. First, if the balance N1 and ERN share neural circuitry, then drugs that influence the ERN should also influence the balance N1. In particular, do dopamine agonists and antagonists, which increase (de Bruijn, Hulstijn, Verkes, Ruigt, & Sabbe, 2004) and decrease (de Bruijn, Sabbe, Hulstijn, Ruigt, & Verkes, 2006; Zirnheld et al., 2004) the amplitude of the ERN in healthy young adults, likewise influence the amplitude of the balance N1? Second, if the balance N1 and ERN share neural circuitry, then disorders that influence the ERN should also influence the balance N1. In particular, do individuals with Parkinson’s disease who present with reduced ERN amplitudes (Seer, Lange, Georgiev, Jahanshahi, & Kopp, 2016), likewise show reduced balance N1s? And could this relate to balance impairment in Parkinson’s disease? Do individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder who present with larger ERN amplitudes (Endrass et al., 2010; Klawohn, Riesel, Grutzmann, Kathmann, & Endrass, 2014) also display larger balance N1s? And could this relate to reduced postural sway in obsessive-compulsive disorder (Kemoun, Carette, Watelain, & Floirat, 2008)? Further, can reward and punishment, which can cause a lasting increase in ERN amplitude (Riesel, Weinberg, Endrass, Kathmann, & Hajcak, 2012), likewise cause lasting changes in the balance N1 amplitude? Or, if the balance N1 and ERN share underlying circuitry, can the effect of punishment on ERN amplitude cross domains to increase the balance N1 in the absence of punishment in balance tasks? While such correlational investigations are interesting and may provide insight into the neural underpinnings of performance monitoring, a much greater challenge will be leveraging such insight to benefit people with altered performance monitoring.

ERN amplitude is characteristically altered in multiple patient populations that seek rehabilitation from persistent pathological behaviors and thought processes, including those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Gehring, Himle, & Nisenson, 2000; Klawohn et al., 2014), generalized anxiety disorder (Weinberg, Klein, & Hajcak, 2012; Weinberg, Olvet, & Hajcak, 2010), substance abuse (Franken, van Strien, Franzek, & van de Wetering, 2007; Schellekens et al., 2010), old age, Parkinson’s disease (Seer et al., 2016), and Huntington’s disease (Beste et al., 2009). While such between-population differences can be leveraged as a risk factor to predict the development of certain neuropsychiatric disorders (Meyer, Hajcak, Torpey-Newman, Kujawa, & Klein, 2015), attempts to leverage knowledge about altered cortical action monitoring and error processing to devise treatment strategies are just beginning. Potential rehabilitation strategies targeting the action monitoring system include, but are not limited to, strategic reorienting of attention from overvalued errors in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Klawohn et al., 2016) or anxiety (Waters et al., 2018) or toward undervalued or unrecognized errors in individuals with PD; habituation of maladaptive error responses or training of alternative behavioral responses to compete with pathological behaviors (Jacoby & Abramowitz, 2016); or targeted noninvasive electrical stimulation of the action monitoring system (Bellaiche, Asthana, Ehlis, Polak, & Herrmann, 2013; Reinhart & Woodman, 2014). A better understanding of the action monitoring system could therefore be advantageous for treating a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, and could even extend into balance rehabilitation if action monitoring spans behavior more broadly. Although the brainstem-mediated involuntary balance-correcting motor responses can adapt rapidly within a single experimental session in healthy young adults (Horak & Nashner, 1986; Welch & Ting, 2014), understanding brain involvement is critical for rehabilitation of balance recovery behavior in individuals with balance impairments due to Parkinson’s disease (Grimbergen, Munneke, & Bloem, 2004), cerebellar dysfunction (Horak & Diener, 1994), or cognitive impairment (Herman, Mirelman, Giladi, Schweiger, & Hausdorff, 2010). Further, the rapid behavioral adaptation observable in balance paradigms could provide an experimental model in which to test hypotheses about error-driven changes in behavior more broadly and may prove particularly helpful in the context of comorbidities between motor and psychiatric disorders.

Finally, we suggest that collaboration across fields could clarify poorly understood interactions between motor, cognitive, and psychiatric disorders, leading to more integrated models of the ERN and balance N1, as well as potential treatment strategies. Many populations with altered error responses also display differences in balance behavior, including frequent comorbidities between anxiety disorders and balance disorders (Balaban, 2002; Balaban & Thayer, 2001; Bolmont, Gangloff, Vouriot, & Perrin, 2002; Yardley & Redfern, 2001), and substantially reduced postural sway in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Kemoun et al., 2008). Further, balance impairment is strongly associated with cognitive impairment in older adults with (Allcock et al., 2009; Mak, Wong, & Pang, 2014; McKay, Lang, Ting, & Hackney, 2018) and without (Camicioli & Majumdar, 2010; Gleason, Gangnon, Fischer, & Mahoney, 2009; Herman et al., 2010; Mirelman et al., 2012) Parkinson’s disease, and rehabilitation interventions that simultaneously target cognitive engagement show greater improvement in motor function in healthy aging (Kraft, 2012; Wu, Chan, & Yan, 2016) and in Parkinson’s disease (McKay, Ting, & Hackney, 2016; Petzinger et al., 2013) than interventions that target motor function alone. Collaboration across fields could provide new insight into these synergistic benefits of combined interventions, and may help explain counterintuitive findings that balance training can ameliorate anxiety disorders (Bart et al., 2009) or that cognitive training can improve balance and gait (Smith-Ray et al., 2015), leading to the development of more integrated treatment strategies for comorbid motor, cognitive, and psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (5T90DA032466, 1P50NS098685, and R01 HD46922–10), the National Science Foundation (1137229), the Georgia Tech Neural Engineering Center, and the Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly Authority of Fulton County.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors report that there are no potential sources of conflict of interest (financial or otherwise) which may be perceived as influencing any author’s objectivity.

References

- Ackermann H, Diener HC, & Dichgans J (1986). Mechanically evoked cerebral potentials and long-latency muscle responses in the evaluation of afferent and efferent long-loop pathways in humans. Neuroscience Letters, 66(3), 233–238. 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90024-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkin AL, Campbell AD, Chua R, & Carpenter MG (2008). The influence of postural threat on the cortical response to unpredictable and predictable postural perturbations. Neurosci Lett, 435(2), 120–125. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkin AL, Quant S, Maki BE, & McIlroy WE (2006). Cortical responses associated with predictable and unpredictable compensatory balance reactions. Exp Brain Res, 172(1), 85–93. 10.1007/s00221-005-0310-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, & Strick PL (1986). Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci, 9, 357–381. 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander WH, & Brown JW (2011). Medial prefrontal cortex as an action-outcome predictor. Nat Neurosci, 14(10), 1338–1344. 10.1038/nn.2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allcock LM, Rowan EN, Steen IN, Wesnes K, Kenny RA, & Burn DJ (2009). Impaired attention predicts falling in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 15(2), 110–115. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgaiyan RD, & Posner MI (1998). Mapping the cingulate cortex in response selection and monitoring. NeuroImage, 7(3), 255–260. 10.1006/nimg.1998.0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban CD (2002). Neural substrates linking balance control and anxiety. Physiol Behav, 77(4–5), 469–475. 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00935-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban CD, & Thayer JF (2001). Neurological bases for balance-anxiety links. J Anxiety Disord, 15(1–2), 53–79. 10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart O, Bar-Haim Y, Weizman E, Levin M, Sadeh A, & Mintz M (2009). Balance treatment ameliorates anxiety and increases self-esteem in children with comorbid anxiety and balance disorder. Res Dev Disabil, 30(3), 486–495. 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaiche L, Asthana M, Ehlis AC, Polak T, & Herrmann MJ (2013). The Modulation of Error Processing in the Medial Frontal Cortex by Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Neurosci J, 2013, 187692 10.1155/2013/187692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W, Quintern J, & Dietz V (1987). Afferent and efferent control of stance and gait: developmental changes in children. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 66(3), 244–252. 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein PS, Scheffers MK, & Coles MGH (1995). “Where did I go wrong?” A psychophysiological analysis of error detection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 21(6), 1312–1322. 10.1037/0096-1523.21.6.1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste C, Willemssen R, Saft C, & Falkenstein M (2009). Error processing in normal aging and in basal ganglia disorders. Neuroscience, 159(1), 143–149. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmont B, Gangloff P, Vouriot A, & Perrin PP (2002). Mood states and anxiety influence abilities to maintain balance control in healthy human subjects. Neurosci Lett, 329(1), 96–100. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini F, Burle B, Liegeois-Chauvel C, Regis J, Chauvel P, & Vidal F (2014). Action monitoring and medial frontal cortex: leading role of supplementary motor area. Science, 343(6173), 888–891. 10.1126/science.1247412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, & Cohen JD (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol Rev, 108(3), 624–652. 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camicioli R, & Majumdar SR (2010). Relationship between mild cognitive impairment and falls in older people with and without Parkinson’s disease: 1-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Gait Posture, 32(1), 87–91. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MG, Allum JHJ, & Honegger F (1999). Directional sensitivity of stretch reflexes and balance corrections for normal subjects in the roll and pitch planes. Experimental Brain Research, 129(1), 93–113. 10.1007/s002210050940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, & Cohen JD (1998). Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Science, 280(5364), 747–749. 10.1126/science.280.5364.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF, Meyer A, & Hajcak G (2017). Error-Specific Cognitive Control Alterations in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, 2(5), 413–420. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF, Zambrano-Vazquez L, & Allen JJ (2012). Theta lingua franca: a common mid-frontal substrate for action monitoring processes. Psychophysiology, 49(2), 220–238. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01293.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chvatal SA, & Ting LH (2012). Voluntary and reactive recruitment of locomotor muscle synergies during perturbed walking. J Neurosci, 32(35), 12237–12250. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6344-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevecoeur F, & Kurtzer IL (2018). Long-latency reflexes for inter-effector coordination reflect a continuous state-feedback controller. J Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.00205.2018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn ER, Hulstijn W, Verkes RJ, Ruigt GS, & Sabbe BG (2004). Drug-induced stimulation and suppression of action monitoring in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 177(1–2), 151–160. 10.1007/s00213-004-1915-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn ER, Sabbe BG, Hulstijn W, Ruigt GS, & Verkes RJ (2006). Effects of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs on action monitoring in healthy volunteers. Brain Res, 1105(1), 122–129. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Posner M, & Tucker D (1994). Localization of a neural system for error detection and compensation. Psychological Science, 5(5). 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00630.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Quintern J, & Berger W (1984b). Cerebral evoked potentials associated with the compensatory reactions following stance and gait perturbation. Neuroscience Letters, 50(1–3), 181–186. 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90483-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Quintern J, & Berger W (1985b). Afferent control of human stance and gait: evidence for blocking of group I afferents during gait. Exp Brain Res, 61(1), 153–163. 10.1007/BF00235630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Quintern J, Berger W, & Schenck E (1985a). Cerebral potentials and leg muscle e.m.g. responses associated with stance perturbation. Exp Brain Res, 57(2), 348–354. 10.1007/BF00236540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckrow RB, Abu-Hasaballah K, Whipple R, & Wolfson L (1999). Stance perturbation-evoked potentials in old people with poor gait and balance. Clin Neurophysiol, 110(12), 2026–2032. 10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00195-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh G, Vandekerckhove J, Forstmann BU, Keuleers E, Brysbaert M, & Wagenmakers EJ (2012). Testing theories of post-error slowing. Atten Percept Psychophys, 74(2), 454–465. 10.3758/s13414-011-0243-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrass T, Reuter B, & Kathmann N (2007). ERP correlates of conscious error recognition: aware and unaware errors in an antisaccade task. Eur J Neurosci, 26(6), 1714–1720. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrass T, Schuermann B, Kaufmann C, Spielberg R, Kniesche R, & Kathmann N (2010). Performance monitoring and error significance in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychol, 84(2), 257–263. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein M, Hohnsbein J, Hoormann J, & Blanke L (1990). Effects of errors in choice reaction tasks on the ERP under focused and divided attention

- Franken IH, van Strien JW, Franzek EJ, & van de Wetering BJ (2007). Error-processing deficits in patients with cocaine dependence. Biol Psychol, 75(1), 45–51. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MGH, Meyer DE, & Donchin E 1993). A Neural System for Error-Detection and Compensation. Psychological Science, 4(6), 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MGH, Meyer DE, & Donchin E (2018). The Error-Related Negativity. Perspect Psychol Sci, 13(2), 200–204. 10.1177/1745691617715310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Himle J, & Nisenson LG (2000). Action-monitoring dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Sci, 11(1), 1–6. 10.1111/1467-9280.00206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentsch A, Ullsperger P, & Ullsperger M (2009). Dissociable medial frontal negativities from a common monitoring system for self- and externally caused failure of goal achievement. NeuroImage, 47(4), 2023–2030. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason CE, Gangnon RE, Fischer BL, & Mahoney JE (2009). Increased risk for falling associated with subtle cognitive impairment: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 27(6), 557–563. 10.1159/000228257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbergen YA, Munneke M, & Bloem BR (2004). Falls in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol, 17(4), 405–415. 10.1097/01.wco.0000137530.68867.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, & Simons RF (2003). Anxiety and error-related brain activity. Biological Psychology, 64(1–2), 77–90. 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00103-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Yeung N, & Simons RF (2005a). On the ERN and the significance of errors. Psychophysiology, 42(2), 151–160. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Vidal F, & Simons RF (2004). Difficulties with easy tasks: ERN/Ne and stimulus component overlap. In Errors, conflicts, and the brain: Current opinions on response monitoring (pp. 204–211).

- Hauser TU, Iannaccone R, Stampfli P, Drechsler R, Brandeis D, Walitza S, & Brem S (2014). The feedback-related negativity (FRN) revisited: new insights into the localization, meaning and network organization. NeuroImage, 84, 159–168. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman T, Mirelman A, Giladi N, Schweiger A, & Hausdorff JM (2010). Executive control deficits as a prodrome to falls in healthy older adults: a prospective study linking thinking, walking, and falling. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 65(10), 1086–1092. 10.1093/gerona/glq077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd CB, & Coles MG (2002b). The neural basis of human error processing: reinforcement learning, dopamine, and the error-related negativity. Psychol Rev, 109(4), 679–709. 10.1037/0033-295x.109.4.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd CB, Dien J, & Coles MG (1998). Error-related scalp potentials elicited by hand and foot movements: evidence for an output-independent error-processing system in humans. Neurosci Lett, 242(2), 65–68. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00035-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, & Diener HC (1994). Cerebellar control of postural scaling and central set in stance. J Neurophysiol, 72(2), 479–493. 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, & Nashner LM (1986). Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol, 55(6), 1369–1381. 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman F, & Notebaert W (2013). Blinded by an error. Cognition, 128(2), 228–236. 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsdunker T, Mierau A, Neeb C, Kleinoder H, & Struder HK (2015). Cortical processes associated with continuous balance control as revealed by EEG spectral power. Neurosci Lett, 592, 1–5. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JV, & Horak FB (2007a). Cortical control of postural responses. J Neural Transm (Vienna), 114(10), 1339–1348. 10.1007/s00702-007-0657-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby RJ, & Abramowitz JS (2016). Inhibitory learning approaches to exposure therapy: A critical review and translation to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev, 49, 28–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentzsch I, & Dudschig C (2009). Why do we slow down after an error? Mechanisms underlying the effects of posterror slowing. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove), 62(2), 209–218. 10.1080/17470210802240655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemoun G, Carette P, Watelain E, & Floirat N (2008). Thymocognitive input and postural regulation: a study on obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Neurophysiol Clin, 38(2), 99–104. 10.1016/j.neucli.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Cohen JD, MacDonald AW 3rd, Cho RY, Stenger VA, & Carter CS (2004). Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science, 303(5660), 1023–1026. 10.1126/science.1089910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Iwaki N, Uno H, & Fujita T (2005). Error-related negativity in children: effect of an observer. Dev Neuropsychol, 28(3), 871–883. 10.1207/s15326942dn2803_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klawohn J, Endrass T, Preuss J, Riesel A, & Kathmann N (2016). Modulation of hyperactive error signals in obsessive-compulsive disorder by dual-task demands. J Abnorm Psychol, 125(2), 292–298. 10.1037/abn0000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klawohn J, Riesel A, Grutzmann R, Kathmann N, & Endrass T (2014). Performance monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a temporo-spatial principal component analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 14(3), 983–995. 10.3758/s13415-014-0248-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft E (2012). Cognitive function, physical activity, and aging: possible biological links and implications for multimodal interventions. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn, 19(1–2), 248–263. 10.1080/13825585.2011.645010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur CD, Dahl RE, & Carter CS (2007). Development of action monitoring through adolescence into adulthood: ERP and source localization. Dev Sci, 10(6), 874–891. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little CE, & Woollacott M (2015). EEG measures reveal dual-task interference in postural performance in young adults. Exp Brain Res, 233(1), 27–37. 10.1007/s00221-014-4111-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart DB, & Ting LH (2007). Optimal sensorimotor transformations for balance. Nat Neurosci, 10(10), 1329–1336. 10.1038/nn1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu P, Tucker DM, & Makeig S (2004). Frontal midline theta and the error-related negativity: neurophysiological mechanisms of action regulation. Clin Neurophysiol, 115(8), 1821–1835. 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier ME, & Steinhauser M (2017). Working memory load impairs the evaluation of behavioral errors in the medial frontal cortex. Psychophysiology, 54(10), 1472–1482. 10.1111/psyp.12899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak MK, Wong A, & Pang MY (2014). Impaired executive function can predict recurrent falls in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 95(12), 2390–2395. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlin A, Mochizuki G, Staines WR, & McIlroy WE (2014). Localizing evoked cortical activity associated with balance reactions: does the anterior cingulate play a role? J Neurophysiol, 111(12), 2634–2643. 10.1152/jn.00511.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlroy WE, & Maki BE (1993). Changes in early ‘automatic’ postural responses associated with the prior-planning and execution of a compensatory step. Brain Res, 631(2), 203–211. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91536-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JL, Lang KC, Ting LH, & Hackney ME (2018). Impaired set shifting is associated with previous falls in individuals with and without Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture, 62, 220–226. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JL, Ting LH, & Hackney ME (2016). Balance, Body Motion, and Muscle Activity After High-Volume Short-Term Dance-Based Rehabilitation in Persons With Parkinson Disease: A Pilot Study. J Neurol Phys Ther, 40(4), 257–268. 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Hajcak G, Torpey-Newman DC, Kujawa A, & Klein DN (2015). Enhanced error-related brain activity in children predicts the onset of anxiety disorders between the ages of 6 and 9. J Abnorm Psychol, 124(2), 266–274. 10.1037/abn0000044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Riesel A, & Proudfit GH (2013). Reliability of the ERN across multiple tasks as a function of increasing errors. Psychophysiology, 50(12), 1220–1225. 10.1111/psyp.12132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierau A, Hulsdunker T, & Struder HK (2015). Changes in cortical activity associated with adaptive behavior during repeated balance perturbation of unpredictable timing. Front Behav Neurosci, 9(272), 272 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner WH, Braun CH, & Coles MG (1997). Event-related brain potentials following incorrect feedback in a time-estimation task: evidence for a “generic” neural system for error detection. J Cogn Neurosci, 9(6), 788–798. 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner WH, Lemke U, Weiss T, Holroyd CB, Scheffers MK, & Coles MGH (2003). Implementation of error-processing in the human anterior cingulate cortex: a source analysis of the magnetic equivalent of the error-related negativity. Biological Psychology, 64(1–2), 157–166. 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirelman A, Herman T, Brozgol M, Dorfman M, Sprecher E, Schweiger A, … Hausdorff JM (2012). Executive function and falls in older adults: new findings from a five-year prospective study link fall risk to cognition. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e40297 10.1371/journal.pone.0040297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki G, Boe S, Marlin A, & McIlRoy WE (2010). Perturbation-evoked cortical activity reflects both the context and consequence of postural instability. Neuroscience, 170(2), 599–609. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki G, Sibley KM, Cheung HJ, Camilleri JM, & McIlroy WE (2009a). Generalizability of perturbation-evoked cortical potentials: Independence from sensory, motor and overall postural state. Neurosci Lett, 451(1), 40–44. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki G, Sibley KM, Cheung HJ, & McIlroy WE (2009b). Cortical activity prior to predictable postural instability: is there a difference between self-initiated and externally-initiated perturbations? Brain Res, 1279, 29–36. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki G, Sibley KM, Esposito JG, Camilleri JM, & McIlroy WE (2008). Cortical responses associated with the preparation and reaction to full-body perturbations to upright stability. Clin Neurophysiol, 119(7), 1626–1637. 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis S, Ridderinkhof KR, Blom J, Band GP, & Kok A (2001). Error-related brain potentials are differentially related to awareness of response errors: evidence from an antisaccade task. Psychophysiology, 38(5), 752–760. 10.1111/1469-8986.3850752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis S, Ridderinkhof KR, Talsma D, Coles MG, Holroyd CB, Kok A, & van der Molen MW (2002). A computational account of altered error processing in older age: dopamine and the error-related negativity. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 2(1), 19–36. 10.3758/CABN.2.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notebaert W, Houtman F, Opstal FV, Gevers W, Fias W, & Verguts T (2009). Post-error slowing: an orienting account. Cognition, 111(2), 275–279. 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pailing PE, & Segalowitz SJ (2004a). The error-related negativity as a state and trait measure: motivation, personality, and ERPs in response to errors. Psychophysiology, 41(1), 84–95. 10.1111/1469-8986.00124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pailing PE, & Segalowitz SJ (2004b). The effects of uncertainty in error monitoring on associated ERPs. Brain Cogn, 56(2), 215–233. 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AM, Hajcak G, & Ting LH (2018). Dissociation of muscle and cortical response scaling to balance perturbation acceleration. J Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.00237.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peterson SM, & Ferris DP (2018). Differentiation in Theta and Beta Electrocortical Activity between Visual and Physical Perturbations to Walking and Standing Balance. eNeuro, 5(4). 10.1523/ENEURO.0207-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, & Jakowec MW (2013). Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol, 12(7), 716–726. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quant S, Adkin AL, Staines WR, Maki BE, & McIlroy WE (2004b). The effect of a concurrent cognitive task on cortical potentials evoked by unpredictable balance perturbations. BMC Neuroscience, 5(18), 1–12. 10.1186/1471-2202-5-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart RM, & Woodman GF (2014). Causal control of medial-frontal cortex governs electrophysiological and behavioral indices of performance monitoring and learning. J Neurosci, 34(12), 4214–4227. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5421-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, & Nieuwenhuis S (2004). The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science, 306(5695), 443–447. 10.1126/science.1100301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesel A, Weinberg A, Endrass T, Kathmann N, & Hajcak G (2012). Punishment has a lasting impact on error-related brain activity. Psychophysiology, 49(2), 239–247. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesel A, Weinberg A, Endrass T, Meyer A, & Hajcak G (2013). The ERN is the ERN is the ERN? Convergent validity of error-related brain activity across different tasks. Biol Psychol, 93(3), 377–385. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, & Segalowitz SJ (2008). Developmental differences in error-related ERPs in middle- to late-adolescent males. Dev Psychol, 44(1), 205–217. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Segalowitz SJ, & Schmidt LA (2005). ERP correlates of error monitoring in 10-year olds are related to socialization. Biol Psychol, 70(2), 79–87. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffers MK, & Coles MGH (2000). Performance monitoring in a confusing world: Error-related brain activity, judgments of response accuracy, and types of errors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26(1), 141–151. 10.1037/0096-1523.26.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens AF, de Bruijn ER, van Lankveld CA, Hulstijn W, Buitelaar JK, de Jong CA, & Verkes RJ (2010). Alcohol dependence and anxiety increase error-related brain activity. Addiction, 105(11), 1928–1934. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seer C, Lange F, Georgiev D, Jahanshahi M, & Kopp B (2016). Event-related potentials and cognition in Parkinson’s disease: An integrative review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 71, 691–714. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, & Davidson RJ (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci, 12(3), 154–167. 10.1038/nrn2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Smith MA, & Krakauer JW (2010). Error correction, sensory prediction, and adaptation in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci, 33, 89–108. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley KM, Mochizuki G, Frank JS, & McIlroy WE (2010). The relationship between physiological arousal and cortical and autonomic responses to postural instability. Exp Brain Res, 203(3), 533–540. 10.1007/s00221-010-2257-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipp AR, Gwin JT, Makeig S, & Ferris DP (2013). Loss of balance during balance beam walking elicits a multifocal theta band electrocortical response. J Neurophysiol, 110(9), 2050–2060. 10.1152/jn.00744.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Ray RL, Hughes SL, Prohaska TR, Little DM, Jurivich DA, & Hedeker D (2015). Impact of Cognitive Training on Balance and Gait in Older Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 70(3), 357–366. 10.1093/geronb/gbt097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieser L, van den Wildenberg W, Hasbroucq T, Ridderinkhof KR, & Burle B (2015). Controlling your impulses: electrical stimulation of the human supplementary motor complex prevents impulsive errors. J Neurosci, 35(7), 3010–3015. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1642-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staines WR, McIlroy WE, & Brooke JD (2001). Cortical representation of whole-body movement is modulated by proprioceptive discharge in humans. Exp Brain Res, 138(2), 235–242. 10.1007/s002210100691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamnes CK, Walhovd KB, Torstveit M, Sells VT, & Fjell AM (2013). Performance monitoring in children and adolescents: a review of developmental changes in the error-related negativity and brain maturation. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 6, 1–13. 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, Danielmeier C, & Jocham G (2014). Neurophysiology of performance monitoring and adaptive behavior. Physiol Rev, 94(1), 35–79. 10.1152/physrev.00041.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, & von Cramon DY (2001). Subprocesses of performance monitoring: a dissociation of error processing and response competition revealed by event-related fMRI and ERPs. NeuroImage, 14(6), 1387–1401. 10.1006/nimg.2001.0935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen V, Cohen JD, Botvinick MM, Stenger VA, & Carter CS (2001). Anterior cingulate cortex, conflict monitoring, and levels of processing. NeuroImage, 14(6), 1302–1308. 10.1006/nimg.2001.0923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van’t Ent D, & Apkarian P (1999). Motoric response inhibition in finger movement and saccadic eye movement: a comparative study. Clinical Neurophysiology, 110, 1058–1072. 10.1016/S1388-2457(98)00036-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese JP, Marlin A, Beyer KB, Staines WR, Mochizuki G, & McIlroy WE (2014). Frequency characteristics of cortical activity associated with perturbations to upright stability. Neurosci Lett, 578, 33–38. 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Cao Y, Kershaw R, Kerbler GM, Shum DHK, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, … Cunnington R (2018). Changes in neural activation underlying attention processing of emotional stimuli following treatment with positive search training in anxious children. J Anxiety Disord, 55, 22–30. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Klein DN, & Hajcak G (2012). Increased error-related brain activity distinguishes generalized anxiety disorder with and without comorbid major depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol, 121(4), 885–896. 10.1037/a0028270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Olvet DM, & Hajcak G (2010). Increased error-related brain activity in generalized anxiety disorder. Biol Psychol, 85(3), 472–480. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch TD, & Ting LH (2008). A feedback model reproduces muscle activity during human postural responses to support-surface translations. J Neurophysiol, 99(2), 1032–1038. 10.1152/jn.01110.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch TD, & Ting LH (2009). A feedback model explains the differential scaling of human postural responses to perturbation acceleration and velocity. J Neurophysiol, 101(6), 3294–3309. 10.1152/jn.90775.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch TD, & Ting LH (2014). Mechanisms of motor adaptation in reactive balance control. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e96440 10.1371/journal.pone.0096440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel JR (2018). An adaptive orienting theory of error processing. Psychophysiology, 55(3). 10.1111/psyp.13041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel JR, & Aron AR (2017). On the Globality of Motor Suppression: Unexpected Events and Their Influence on Behavior and Cognition. Neuron, 93(2), 259–280. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema JR, van der Meere JJ, & Roeyers H (2007). Developmental changes in error monitoring: an event-related potential study. Neuropsychologia, 45(8), 1649–1657. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Chan JS, & Yan JH (2016). Mild cognitive impairment affects motor control and skill learning. Rev Neurosci, 27(2), 197–217. 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L, & Redfern MS (2001). Psychological factors influencing recovery from balance disorders. J Anxiety Disord, 15(1–2), 107–119. 10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00045-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung N, Bogacz R, Holroyd CB, Nieuwenhuis S, & Cohen JD (2007). Theta phase resetting and the error-related negativity. Psychophysiology, 44(1), 39–49. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00482.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung N, Botvinick MM, & Cohen JD (2004). The Neural Basis of Error Detection: Conflict Monitoring and the Error-Related Negativity. Psychological Review, 111(4), 931–959. 10.1037/0033-295x.111.4.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirnheld PJ, Carroll CA, Kieffaber PD, O’Donnell BF, Shekhar A, & Hetrick WP (2004). Haloperidol impairs learning and error-related negativity in humans. J Cogn Neurosci, 16(6), 1098–1112. 10.1162/0898929041502779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]