Abstract

There is increasing evidence of the health benefits of exposure to natural environments, including green and blue spaces. The association with physical functioning and its decline at older age remains to be explored. The aim of the present study was to investigate the longitudinal association between the natural environment and the decline in physical functioning in older adults. We based our analyses on three follow-ups (2002–2013) of the Whitehall II study, including 5759 participants (aged 50 to 74 years at baseline) in the UK. Exposure to natural environments was assessed at each follow-up as (1) residential surrounding greenness across buffers of 500 and 1000 m around the participants’ address using satellite-based indices of greenness (Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)) and (2) the distance from home to the nearest natural environment, separately for green and blue spaces, using a land cover map. Physical functioning was characterized by walking speed, measured three times, and grip strength, measured twice. Linear mixed effects models were used to quantify the impact of green and blue space on physical functioning trajectories, controlled for relevant covariates.

We found higher residential surrounding greenness (EVI and NDVI) to be associated with slower 10-year decline in walking speed. Furthermore, proximity to natural environments (green and blue spaces combined) was associated with slower decline in walking speed and grip strength. We observed stronger associations between distance to natural environments and decline in physical functioning in areas with higher compared to lower area-level deprivation. However, no association was observed with distance to green or blue spaces separately. The associations with decline in physical functioning were partially mediated by social functioning and mental health.

Our results suggest that higher residential surrounding greenness and living closer to natural environments contribute to better physical functioning at older ages.

Keywords: Physical capability, Functional status, Sea, NDVI, Built environment, Ageing

1. Introduction

Physical functioning is a main indicator of a person’s ability to carry out daily activities (Cooper et al., 2010; Kuh, 2007; Rooth et al., 2016) and a major component of healthy ageing (Kuh et al., 2014; World Health Organization, 2015a). It is increasingly important to identify measures that foster healthy ageing and physical functioning as the world’s older population is growing rapidly. According to the World Health Organization (2015b), the proportion of people over 60 years old is expected to nearly double from 12% to 22% between 2015 and 2050. This growth in the older population is occurring faster in urban areas (United Nations, 2015), where exposure to urban-related stressors such as air pollution and noise can affect physical functioning (Beard and Petitot, 2010; Schootman et al., 2010; Weuve et al., 2016). While such stressors carry a negative impact, others such as urban natural environments could play a beneficial role in improving physical functioning (Cerin et al., 2017; Van Cauwenberg et al., 2011).

An accumulating body of evidence has shown beneficial associations between natural environments including green spaces and health (Fong et al., 2018; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2017). Green spaces are defined as open pieces of land that are “partly or completely covered with grass, trees, shrubs, or other vegetation” and include, among others, parks, forests, community gardens, and cemeteries (Environmental Protection Agency, 2017). Exposure to natural environments have been associated to better mental health (Gascon et al., 2015) and self-perceived general health (Dadvand et al., 2016; Triguero-Mas et al., 2015), and lower risk of morbidity (James et al., 2015) and mortality (Gascon et al., 2016). Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain these associations such as greater physical activity (Dadvand et al., 2016; Gong et al., 2014), improved social interaction (Dadvand et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2018), decreased levels of stress (Gong et al., 2016), and lower exposure to air pollution (Dadvand et al., 2015b, 2012) and noise (Dzhambov and Dimitrova, 2014). Through these mechanisms, exposure to green spaces could also be a protective factor against the decline in physical functioning in older adults, as more physical activity (Fielding et al., 2017), enhanced social support (Chen et al., 2012; Perissinotto et al., 2012), better mental health (Stuck et al., 1999), and lower exposure to air pollution and noise (Weuve et al., 2016) are suggested to be associated with decelerated decline in physical functioning at older age. However, studies on the association between the natural environment and physical functioning are scarce, used a crosssectional design, and reported conflicting results (Vogt et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2018).

In addition, exposure to outdoor blue spaces has beneficial associations with health. The term blue spaces refers to “all the visible surface waters in space” including lakes, rivers, and coastal water (Gascon et al., 2015). In particular, studies have found associations with increased physical activity (White et al., 2016) and improved mental health (de Vries et al., 2016; Dempsey et al., 2018; Nutsford et al., 2016) and well-being (Gascon et al., 2017), but also with social interaction (de Bell et al., 2017; Haeffner et al., 2017). Considering that the proposed pathways for the associations between blue space and health are similar to those for green spaces, exposure to blue spaces may also have a beneficial impact on physical functioning in older adults. However, this potential association has not yet been explored. The aim of the present study was to investigate the longitudinal association between the natural environment, including green and blue spaces, and decline in physical functioning in older adults. Moreover, as previous studies have shown that the association between the natural environment and health may differ by socioeconomic status (Gascon et al., 2015; Maas et al., 2009; McEachan et al., 2016) and sex (Bos et al., 2016; Richardson and Mitchell, 2010), we explored this variation in the association in stratified analyses.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and setting

This study was based on the Whitehall II study, an ongoing cohort established in 1985 among 10308 (6895 men and 3413 women, aged 35–55) civil servants from 20 government departments in London, UK (Marmot and Brunner, 2005). The participants were invited for clinical examinations and questionnaires every five years, irrespective of participation in the previous wave of data collection, unless they had withdrawn permanently from the study. Physical functioning was first introduced to the clinical examination in 2002–2004, making it the baseline of the present study, with repeated measurements in follow- ups in 2007–2009 and 2012–2013. We excluded participants who did not live in England, Scotland, or Wales during these follow-ups (1% of participants in 2002–2004) (Fig. S1). Participant’s written and informed consent and research ethics approvals (University College London (UCL) ethics committee) are renewed at each follow-up. The latest approval was granted by the Joint UCL/UCLH Committee on the Ethics of Human Research (Committee Alpha), reference number 85/0938.

2.2. Exposure assessment

Our assessment of exposure to green and blue spaces encompassed two different aspects: (1) residential surrounding greenness, an indicator of general outdoor greenness of the participants’ neighbourhoods and (2) residential proximity to natural environments, separately for green and blue spaces, as a surrogate for access to these spaces (Expert Group on the Urban Environment, 2000). We extracted these indicators for the residential address of each participant at each follow- up (2002–2004, 2007–2009, and 2012–2013). The residential location at each follow-up was geocoded based on the centroid of the postcode of the participant at that time, obtained from the postcode directory of the corresponding year, provided by the Office for National Statistics (Office for National Statistics, 2017). The postcodes in England and Wales held a median number of 14 (interquartile range (IQR): 20) households and a median number of 33 (IQR: 47) residents in 2011 (Office for National Statistics, 2013). We used the software ArcGIS 10 and GDAL 2.2.0 for the exposure assessment.

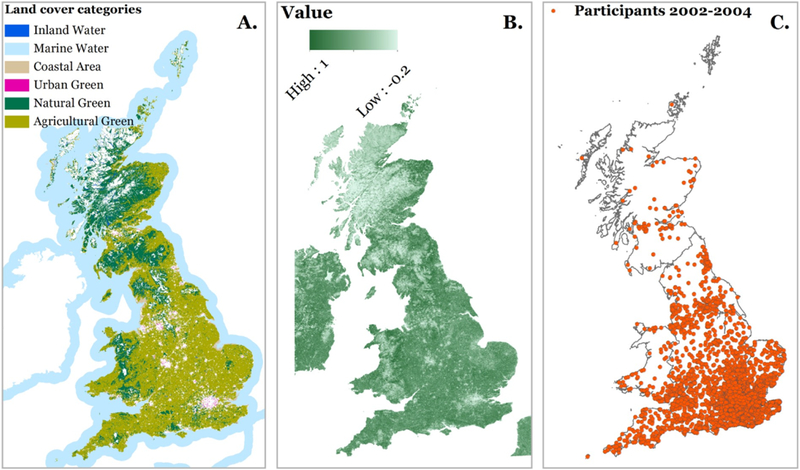

2.2.1. Residential surrounding greenness

The characterization of outdoor greenness surrounding the residential address was based on two vegetation indices, namely the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), derived from satellite images obtained by the Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) onboard the TERRA satellite (Didan, 2015). NDVI is an indicator of greenness based on land surface reflectance of visible (red) and near-infrared parts of spectrum (Weier and Herring, 2000). It ranges between - 1 and 1 with higher numbers indicating more greenness. EVI is a vegetation index which, compared to NDVI, is more responsive to canopy structural variations (i.e. it functions better in densely vegetated areas) while it minimizes soil background influences (MODIS, 2017). The EVI and NDVI maps had a spatial resolution of 250 m by 250 m and were obtained over a period of 16 days. These maps were produced every 16 days from 2000 onward. We used MODIS images with minimal cloud cover captured between May and June (i.e. the maximum vegetation period of the year in our study region to maximize the contrast in exposure) of the relevant years to each follow-up as described in Table S1. We obtained these images from the Data Pool website of the NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, 2014).

Sets of EVI and NDVI were extracted for each participant’s address at each follow-up separately across buffers of 500 m and 1000 m around the corresponding postcode centroid (de Keijzer et al., 2018). The 500 m buffer was selected to represent the direct environment around the home, which is potentially more relevant for older adults (Gong et al., 2014). It was unfeasible to choose buffers smaller than 500 m given the size of the postcode areas and the resolution of our EVI and NDVI maps. The 1000 m buffer was chosen to represent the general distance that adults walk to reach places nearby the home as discussed in a previous publication of the Whitehall II study (Stockton et al., 2016). However, a circular buffer is based on the assumption that the individual’s residence is geographically central to their neighbourhood. Therefore, the average EVI and NDVI were calculated across the Lower layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs). LSOAs are administrative areas, created by grouping postcodes while taking into account natural barriers, proximity, and social homogeneity (Martin, 2001), which could be considered to represent a neighbourhood (Stockton et al., 2016). LSOAs have around 1500 residents and 650 households (Office for National Statistics, 2011). Each participant was assigned a LSOA at each follow-up using the corresponding postcode of that follow-up. To sum up, we abstracted estimates for two vegetation indices at three follow-ups for three surfaces (two buffers and LSOA) resulting in up to 18 2 × 3 × 3) exposure estimates per person.

2.2.2. Residential distance to natural environments

We applied COoRdination and INformation on the Environmental (CORINE) land use map (2006) to assess the distance of participants’ residential addresses to natural environments. CORINE maps developed by the European Environment Agency (European Environment Agency, 2007) and only include areas of 25 ha and larger. We abstracted the residential distance to the nearest natural environment for each participant at each follow-up separately for green spaces (encompassing agricultural land, natural green, and urban green) and blue spaces (including inland water, marine water, and coastal areas). The CORINE land cover categories that were considered as natural environments are described in Table S2.

For each participant at each follow-up, we abstracted the linear distance from the postcode centroid to the nearest edge of the nearest green space and the distance to the nearest edge of the nearest blue space. The distance to the nearest natural environment was obtained as the distance to the nearest blue or green space (hereafter referred to as “distance to any natural environment”).

2.3. Physical functioning

Physical functioning was assessed by repeated objective measures of lower and upper body function (Lara et al., 2015). Lower body function was evaluated by walking speed, assessed in 2002–2004, 2007–2009, and 2012–2013, covering a follow-up period of lOyears. For this test, the participants were instructed to walk at their usual walking pace for 2.44 m (Guralnik et al., 1994). Participants were standing static at the start of the course. A trained nurse stopped the timing as soon as the participant’s foot hit the floor behind the end of the walking course. At each follow-up, the test was repeated three times and the walking speed (m/s) was calculated by dividing 2.44 m by the average of the three walking times in seconds.

Upper body function was assessed by grip strength at the follow-ups of 2007–2009 and 2012–2013, covering a 5-year period. Grip strength was measured by squeezing a Smedley hand grip dynamometer as hard as possible for 2 s (Rantanen et al., 1999). At each follow-up, the test was repeated three times with 1 min rest between each test, and the mean grip strength in kilograms over these three times was used in the analyses.

2.4. Covariates and mediators

Data on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status (SES), and lifestyle factors were collected at each wave. The demographic characteristics included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, and height. For SES, we used two individual level indicators (educational attainment and employment grade), and two area-level indicators (employment domain and income domain of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) at the LSOA level). Lifestyle factors included smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption, and intake of fruit and vegetables. Furthermore, data was collected on limitations in walking over a mile and additional neighbourhood variables including an indicator of rurality and the proportion of road and path area in the LSOA. Additional information on the assessment of the covariate data can be found in the Supplement (SI).

Data were collected on potential mediators including physical activity (MET-hours a week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity), gardening (weekly or less often/never), air pollution (PM2.5 levels in μg/m3), and social functioning and mental health (both scores on a scale of 0 to 100). Additional information on the assessment of the mediator data can be found in the Supplement (SI).

2.5. Statistical analysis

2.5.1. Main analyses

The scores of the physical functioning tests were converted into sex-specific z-scores (Mean = 0, SD = 1) separately for walking speed and grip strength following the method applied in previous Whitehall II publications (Sabia et al., 2014; Singh-Manoux et al., 2011). For walking speed, we used the distribution of the baseline measurement in the 2002–2004 follow-up and for grip strength we applied the distribution of the baseline measurement in 2007–2009. A positive score for each of these z-scores would therefore indicate better physical functioning. We tested the association of each exposure variable (one at a time) with walking speed and grip strength separately. For each analysis, we included all participants with available data on the corresponding physical functioning test, exposure, and complete covariate data for at least one follow-up.

To take into account the repeated measurements for each participant, we used mixed effects models with physical functioning z-scores (separately for walking speed and grip strength) as outcome, measures of exposure to natural environments (one at a time) as the fixed predictor, and the person as random effect (de Keijzer et al., 2018). An interaction term between age (centred at the mean age at baseline and divided by 5 to give change over 5 years) and the exposure at each follow-up was used to quantify the impact of the exposure on the trajectory of decline in physical functioning (Rouxel et al., 2017). Age was centred at the mean age at 2002–2004 (61 years) for walking speed and the mean age at 2007–2009 (66 years) for grip strength. The interaction term of the exposure with age could be interpreted as the difference in the 5-year change in physical functioning scores associated with the exposure during the course of our study. The main effect of the exposure captured the baseline differences in physical function z-score that were associated with the exposure at the start of the study period. All models were adjusted for sex (male or female), ethnicity (white or nonwhite), age squared (Granic et al., 2016; Rouxel et al., 2017), height, marital status (married/cohabiting, yes or no), usual frequency of alcohol consumption (sometimes, daily, or never), smoking status (current, past, or never), intake of fruit and vegetables (twice a day or less), educational attainment (lower secondary school or less, higher secondary school, and university or higher degree), employment grade (high (administrative), middle (professional and executive), and low (clerical)), and country-specific fertiles of income and employment scores of the IMD. Moreover, we adjusted for rurality (rural, yes or no), because differences between urban and rural areas can be associated with both exposure to natural environments and physical functioning. Except for sex, ethnicity, and education, all covariates were treated as time-varying variables. The associations were reported per interquartile range (IQR) increase in residential surrounding greenness or distance to natural environments. The IQR was calculated separately for each indicator of exposure based on all study participants.

2.5.2. Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, to account for missing covariate data, we repeated the analysis with imputed data for the missing covariate values. Multiple imputation was conducted by chained equations carrying out 25 imputations with 10 cycles for each imputation that generated 25 complete datasets. The description of the applied multiple imputation models is presented in Table S3.

Second, we repeated the analysis (a) including only observations from England to test the influence of country (England, Scotland, Wales), (b) excluding non-white participants to test the influence of ethnicity, and (c) excluding rural areas as rural areas generally have larger postcode areas which could have resulted in greater exposure misclassification. Given the small proportion of participants from Wales and Scotland (< 4%, Table 1), non-white participants (< 9%, Table 1) and participants living in rural areas (< 12%, Table 1), it was not feasible to conduct stratified analyses by country, ethnicity, or rurality.Furthermore, we repeated the analysis (d) excluding participants who changed postcode In the study period to test the influence of moving and (e) excluding participants with limitations in walking over one mile at baseline (2002–2004 for walking speed and 2007–2009 for grip strength) to test the influence of functional limitations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants and physical functioning scores over the study period.

| 2002–2004 | 2007–2009 | 2012–2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | |||

| N | 5394 | 4940 | 4378 |

| Age; median (IQR) | 60.2 (56.0–66.2) | 64.9 (60.9–70.9) | 68.7 (64.8–74.4) |

| Sex; N(%) male | 3920 (72.7) | 3640 (73.7) | 3260 (74.5) |

| Ethnicity; N(%) white | 5002 (92.7) | 4614 (93.4) | 4109 (93.9) |

| Marital status; N(%) married/cohabiting | 4135 (76.7) | 3771 (76.3) | 3300 (75.4) |

| Educational level; N(%) | |||

| ≤ Lower secondary school | 1888 (35.0) | 1672 (33.9) | 1461 (33.4) |

| Higher secondary school | 1520 (28.2) | 1423 (28.8) | 1263 (28.9) |

| ≥ University | 1986 (36.8) | 1845 (37.4) | 1654 (37.8) |

| Employment grade; N(%) | |||

| Low (clerical) | 488 (9.0) | 399 (8.1) | 320 (7.3) |

| Middle (professional and executive) | 2332 (43.2) | 2074 (42.0) | 1816 (41.5) |

| High (administrative) | 2574 (47.7) | 2467 (49.9) | 2242 (51.2) |

| IMD income domain; median (IQR) | 0.06 (0.03–0.11) | 0.06 (0.03–0.10) | 0.06 (0.03–0.10) |

| Alcohol consumption; N(%) daily | 2545 (47.2) | 2313 (46.8) | 2061 (47.1) |

| Fruit and vegetable intake; N(%) > 2 a day | 2228 (41.3) | 2039 (41.3) | 2606 (59.5) |

| Smoking status; N(%) current smokers | 396 (7.3) | 255 (5.2) | 134 (3.1) |

| Country; N(%) living in England | 5238 (97.1) | 4773 (96.6) | 4219 (96.4) |

| Rurality; N(%) rural | 567 (10.5) | 582 (11.8) | 493 (11.3) |

| Physical functioning; mean (SD) | |||

| Walking speed z-score | ~0 (1) | −0.535 (1.000) | −0.441 (0.971) |

| Grip strength z-score | - | ~0 (1) | −0.206 (1.027) |

Third, to assess residential surrounding greenness in the main analyses, we used satellite images obtained in summer months (i.e. the maximum vegetation period) in order to maximize the contrast in exposure. To explore the robustness of our findings and take into account the influence of season on greenness, we acquired MODIS images with minimal cloud cover captured in December (i.e. the minimum vegetation period in our study region) from the relevant years to each follow- up as described in Table S1 (winter estimates). We then abstracted the average EVI across the 500 m buffer and averaged this “winter” estimate with the “summer” estimate and repeated our analyses using this summer-winter estimate.

Finally, we used inverse probability weighting to investigate the impact of differential loss to follow-up on our findings (de Keijzer et al., 2018; Weuve et al., 2012). Each participants’ probability of completing the study (i.e. alive and participating in the physical functioning tests in all available follow-ups) was estimated by logistic regression models with completing the study (yes/no) as outcome, and relevant covariates as predictors. We defined the weight for each participant as the inverse probability of completing the study period, and applied it in the main model. Further information is provided in the Supplement (S2).

2.5.3. Stratified analyses

We stratified the analyses by sex, education, and the tertiles of the IMD income domain to explore variation in the association between residential surrounding greenness or distance to natural environments and physical functioning across the strata of sex and SES. The associations were reported per IQR calculated separately for each exposure and each stratum.

2.5.4. Mediation analyses

We tested for mediation of the longitudinal association between residential surrounding greenness and distance to natural environments and the change in physical functioning scores over the study period by physical activity, gardening, air pollution, social functioning, and mental health. To establish mediation, we followed the four steps of Baron and Kenny (1986) as used in our previous studies of health benefits of green spaces (Dadvand et al., 2016; de Keijzer et al., 2018; Zijlema et al., 2017) which are described in the Supplement (S2). We considered mediation if the exposure variable (green space) was significantly associated with the outcome (walking speed or grip strength), the exposure variable was significantly associated with the mediator, the mediator was significantly associated with the outcome after controlling for exposure, and the association between the exposure and the outcome was eliminated or weakened when the mediator was included in the model. If such a case was identified, we quantified the contribution of each mediator to the association expressed as the proportion of the total effect that is mediated by the mediator using the mediation package of R (Tingley et al., 2014). Further information is given in the Supplement (S3).

3. Results

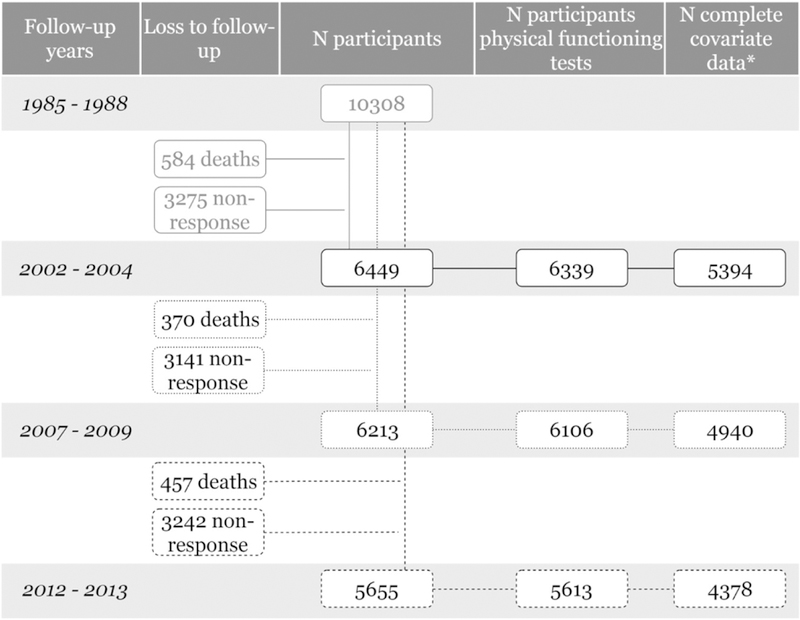

Of 7055 participants with at least one observation for a physical functioning test, 5759 had complete covariate data in at least one follow-up (Fig. 1). The socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. For the walking speed tests, the median follow-up time was 9.0 years (IQR: 8.8–9.2). The average walking speed was 1.25 m/s in 2002–2004, 1.11 m/s in 2007–2009 and 1.13 m/s in 2012–2013. For grip strength, the median follow-up time was 4.1 years (IQR: 3.9–4.2) and the mean values were 36.3 kg in 2007–2009 and 34.8kg in 2012–2013. The average residential surrounding greenness and distance to natural environments did notchange notably over the study period (Table S4). The estimates of EVI and NDVI were strongly correlated with each other and negatively correlated with the estimates of distance to natural environments (Table S5, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart study population.

*Number of participants in the physical functioning tests with complete covariate data in each of the follow-ups.

Fig. 2.

A. Geographical location of green and blue spaces (CORINE land cover map 2006), B. Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) levels in the United Kingdom (May/June 2003) and C. the geographical distribution of the participants’ postcodes at baseline. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.1. Main analyses

Estimated associations between residential surrounding greenness and the physical functioning z-scores (walking speed and grip strength) were similar for greenness in the 500 m buffer, 1000 m buffer, and the LSOA (Table 2). When using NDVI as an alternative measure of greenness, we found similar associations as with the EVI estimates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in the physical functioning z-scores at baseline and over 5 years associated with one interquartile range (IQR) Increase in residential surrounding greenness (EVI and NDVI) or distance to natural environments (green spaces, blue spaces, and any natural environment).

| Walking speed |

Grip strength |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | |

| Residential surrounding greenness (EVI) | ||||||

| 500 m | 0.16 | −0.01 (−0,04, 0.02) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.16 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07)* | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) |

| 1000 m | 0.17 | −0.01 (−0,04, 0.03) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.17 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) |

| LSOA | 0.20 | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.02) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.20 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.03) |

| Residential surrounding greenness (NDVI) | ||||||

| 500 m | 0.17 | −0.06 (−0,09, −0.03)* | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.17 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.09)* | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| 1000 | 0.17 | −0.06 (−0.10, - 0.03)* | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.17 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10)* | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| LSOA | 0.20 | −0.06 (−0,09, −0.02)* | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04)* | 0.19 | 0.05 (0.02, 0.09)* | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) |

| Distance to natural environments | ||||||

| Green space | 624 m | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.00) | 618 m | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| Blue space | 6880 m | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.05) | −0.01 (−0,02, 0.01) | 6929 m | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.05) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| Any natural environment | 556 m | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.03, 0.00)* | 551 m | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00)* |

p < 0.05. Note: estimates are from linear mixed effects models including exposure, age, age2, and × exposure. Adjusted for sex, ethnicity (white, non-white), marital status (married/cohabiting, yes or no), height, alcohol use (frequency of consumption; sometimes, daily, or never), intake of fruit and vegetables (twice a day or less), smoking (current, past, or never), rurality (rural, yes or no), education (lower secondary school or less, higher secondary school, and university or higher degree), employment grade (high, middle, or low), and tertiles of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) income score and of IMD employment score.

We observed slower decline in walking speed in participants with higher residential surrounding greenness and participants living closer to any natural environment. The fully-adjusted models showed that one-IQR increase in EVI in a 500 m buffer surrounding the residence was associated with slower decline in walking speed (difference in decline over 5 years = 0.020 z-score, 95% confidence interval (Cl): 0,005 to 0.035; Table 2), In a model including mean values for all covariates, we estimated that the mean decline in the walking speed z- score was 0.266 over 5 years in participants aged 65 years. The difference in decline associated with an IQR increase in EVI was thus equivalent to a 7.5% slower decline in walking speed over 5 years. In addition, an IQR increase in distance to any natural environment was associated with faster decline in walking speed (difference in decline over 5years = −0.016 z-score, 95% Cl: —0.029 to —0.003; Table 2). Compared to the estimated average decline in the walking speed z-score over 5 years in participants aged 65 years, this difference was equivalent to a 6.0% faster decline in walking speed over 5 years. We also observed faster decline in walking speed associated with distance to green space and blue spaces (separately); however, none of the associations attained statistical significance. The baseline associations with EVI-based residential surrounding greenness and distance to natural environments were not statistically significant; however, for the NDVI- based residential surrounding greenness we observed inverse baseline associations with walking speed (Table 2).

For grip strength, we found higher residential surrounding greenness to be associated with higher grip strength at baseline, but not with decline over the study period. One-IQR increase in EVI in a 500 m buffer surrounding the residence was associated with a difference in grip strength z-score of 0.033 (95% Cl: 0.000 to 0.066) at baseline (Table 2). In contrast, greater distance to any natural environment was associated with slower decline in grip strength over the study period (difference in decline over 5 years per one-IQR increase = 0.018 z- score, 95% Cl: −0.036, −0.001), but no association was observed with grip strength at baseline (Table 2). In a model including mean values of all covariates, we estimated that the mean decline in the grip strength z- score was 0.252 over 5 years in participants of 65 years old. Compared to this estimated average decline, the difference in decline associated with one-IQR increase in distance to any natural environment was equivalent to a 7.1% faster decline in grip strength over 5 years.

3.2. Sensitivity analyses

As presented in Table S6, the association between EVI and distance to any natural environment and decline in walking speed did not change notably when using multiple imputation (a), when including only observations from England (b), after excluding non-white participants (c) or participants who changed postcode in the study period (e), or when using the averaged summer-winter estimate of EVI (g), but attenuated slightly after excluding participants living in rural areas (d) or participants with walking limitations (f). The results were similar for NDVI (data not shown). For grip strength, the results of the sensitivity analyses are presented in Table S7. The association between EVI and baseline grip strength was slightly stronger when using multiple imputation (a), after excluding rural areas (d) or participants who changed postcode over the study period (e) or participants with walking limitations at baseline (f), and when using the summer-winter estimate of EVI (g). The results were similar for NDVI (data not shown). The association between distance to any natural environment and decline in grip strength over the study period was attenuated when using multiple imputation (a) and after excluding non-white participants (c) or participants with walking limitations (f), but was similar when only including observations from England (b) or when excluding rural areas (d) or participants who changed postcode over the study period (e). Finally, the associations with physical functioning were consistent with the main model when inverse probability weighting was used to account for potential bias due to differential loss to follow-up (Table S8).

3.3. Stratified analyses

We only present the results of the stratified analyses for EVI in the 500 m buffer and the distance to any natural environment for which we found statistically significant associations with physical functioning.

When stratified by sex, the association with decline in walking speed was slightly stronger among men for EVI, while the association with distance to any natural environment was slightly stronger among women (Table 3.A). For grip strength, stratifying the analysis by sex did not change the association with EVI notably (Table 4.A). However, regarding distance to any natural environment, among men, an increase in distance was associated with lower grip strength at baseline but not with decline in grip strength over time, while among women, an increase in distance was associated with faster decline in grip strength over time but not with grip strength at baseline (Table 4.A).

Table 3.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in the walking speed z-score at baseline and over 5 years associated with one interquartile range increase in residential surrounding greenness (EVI in the 500 m buffer) or distance to any natural environment stratified by A) sex, B) education, and C) IMD income domain.

| EVI (500 m) |

Distance to any natural environment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modifier | N | IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | P-int | IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | P-int |

| A) Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 4184 | 0.16 | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.02 (0.00, 0,04)* | 0.01 | 528 m | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.00) | 0.06 |

| Women | 1573 | 0.16 | −0.01(−0.07, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) | 638 m | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.00) | ||

| B) Education | |||||||||

| ≤ Lower secondary school | 2025 | 0.15 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) | 511 m | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | ||

| Higher secondary school | 1613 | 0.16 | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.05) | 0.04 (0,01, 0.07)* | 0.10 | 535 m | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.06) | −0.03 (−0.05, 0.00)* | 0.26 |

| ≥ University | 2119 | 0.17 | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 621 m | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00) | ||

| C) IMD income domain | |||||||||

| Tertile 1 (less deprived) | 2218 | 0.14 | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.04) | 415 m | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) | ||

| Tertile 2 | 1943 | 0.17 | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | 0,03 (0,00, 0.06) | 0.77 | 515 m | 0.00 (−0.05, 0,04) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.01) | 0.66 |

| Tertile 3 (most deprived) | 2061 | 0.13 | 0.01 (−0.04, 0,06) | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.03) | 730 m | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.07) | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01)* | ||

P-int: the p-value for interaction was assessed by the Wald test comparing the main model to a model including an interaction between the modifier and exposure (modifier × exposure) and an interaction between the modifier, exposure, and age (modifier × exposure × age).

p < 0.05. Note: estimates are from linear mixed effects models adjusted for age, age2, sex, ethnicity, marital status, height, alcohol use, diet, smoking, rurality, education, employment grade, and tertiles of the IMD employment and income domain.

Table 4.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in the grip strength z-score at baseline and over 5 years associated with one interquartile range increase in residential surrounding greenness (EVI in the 500 m buffer) or distance to any natural environment stratified by A) sex, B) education, and C) IMD income domain.

| EVI (500 m) |

Distance to any natural environment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modifier | N | IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | P-int | IQR | Baseline | 5-year difference | P-int |

| A) Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 3753 | 0.16 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.11 | 517 m | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.00)* | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.01 |

| Women | 1342 | 0.17 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.09) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | 632 m | 0.02 (−0.04, 0.08) | −0.05 (−0.08, −0.01)* | ||

| B) Education | |||||||||

| ≤ Lower secondary school | 1740 | 0.15 | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.09) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | 508 m | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.00) | ||

| Higher secondary school | 1451 | 0.16 | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) | 0.55 | 525 m | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.00) | 0.39 |

| ≥ University | 1904 | 0.17 | 0.06 (0.00, 0.11) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.01) | 618 m | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.04) | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | ||

| C) IMD income domain | |||||||||

| Tertile 1 (less deprived) | 1913 | 0.14 | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.03) | 413 m | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | ||

| Tertile 2 | 1681 | 0.17 | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.10) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.09 | 513 m | −0.05 (−0.10, 0.00) | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.02) | 0.33 |

| Tertile 3 (most deprived) | 1695 | 0.14 | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.00) | 722 m | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.00) | ||

P-int: the p-value for interaction was assessed by the Wald test comparing the main model to a model including an interaction between the modifier and exposure (modifier × exposure) and an interaction between the modifier, exposure, and age (modifier × exposure × age).

p < 0.05. Note: estimates are from linear mixed effects models adjusted for age, age2, sex, ethnicity, marital status, height, alcohol use, diet, smoking, rurality, education, employment grade, and tertiles of the area IMD employment and income domain.

When stratified by educational level, no clear trends were found in the associations between green space and the physical functioning scores across the strata of educational level (Tables 3.B and 4.B). Similarly, we did not observe any clear trend for the association between EVI and walking speed (Table 3.C) and grip strength (Table 4.C) across the strata of area deprivation. For the distance to any natural environment, however, the strongest association with decline in walking speed and decline in grip strength was found among those living in areas within the highest tertile of area deprivation, compared to the lowest and middle tertile (Tables 3.C and 4.C). For the association between distance to any natural environment and baseline walking speedand baseline grip strength, no such trend was observed (Tables 3.C and 4.C).

3.4. Mediation

In the main analyses we found that EVI and distance to any natural environment were significantly associated with decline in walking speed over the study period (Table 2). For EVI, we only found suggestions of mediation of the association by the social functioning score (Table S9) with an estimated mediated proportion of 10% (95% Cl: 1%, 34%). For distance to any natural environment, we found suggestions of mediation of the association with decline in walking speed by the mental health and social functioning scores (Table S9) with estimated mediated proportions of 3% (95% Cl: 0%, 15%) for mental health and 13% (95% Cl: 4%, 52%) for social functioning.

For grip strength, EVI was not significantly associated with decline over the study period, but we did observe a significant association with distance to any natural environment (Table 2). The conditions for mediation of this association were only met for mental health (Table S10). However, the estimated mediated proportion did not reach statistical significance (4%; 95% Cl: −1%, 30%).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first longitudinal study to investigate the impact of long-term residential surrounding greenness and proximity to natural environments on decline in physical functioning in older adults. We used repeated objective measures of upper and lower body function together with the characterization of residential surrounding greenness (using two satellite-based indices of greenness) and distance to green and blue spaces. We observed that greater exposure to residential surrounding greenness was associated with slower decline in walking speed over the study period and higher grip strength at baseline. Considering the two different indices of greenness, the associations were similar, except for a counterintuitive association between higher NDVI and lower baseline walking speed that was not found for EVI. We do not have an explanation for this finding. In addition, proximity to any natural environment was associated with slower decline in walking speed and grip strength over the study period. In stratified analyses, we generally found stronger associations in participants living in areas with higher area deprivation compared to those living in areas with lower area deprivation. The findings were robust to a wide range of sensitivity analyses.

While we did not observe an association between residential surrounding greenness and decline in grip strength over the study period, we did find a statistically significant association between proximity to any natural environment and decline in grip strength in complete case analysis. However, this association was not statistically significant in analysis using multiple imputation. The 5-year follow-up period of grip strength may not have been sufficient to find an association with the decline, as the analysis was restricted to only two data points.

The baseline association is likely to reflect the association preceding the study period. These estimates could have been affected by exposure occurring before the study period due to, for instance, prior home addresses. The association with the change in the physical functioning scores over the study period are based on the exposure at the home address of the participants during the study period and are adjusted for the baseline association. Part of our observed larger estimates for the decline in physical functioning compared to the baseline estimates might therefore reflect better characterization of exposure.

4.1. Available evidence

Studies on green space exposure and physical functioning are scarce and most had a cross-sectional design, which did not rule out reverse causality (i.e. those with better health choose to live in greener areas). Some studies have looked at the association of green space with frailty or disability (Vogt et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2018). A recent longitudinal study covering a period of two years found that neighbourhood green space was associated with improvement in frailty status in older adults aged over 65 year old (Yu et al., 2018). In addition, a cross-sectional study found no clear association between distance to green space and self-rated physical constitution, disability and health-related quality of life (Vogt et al., 2015). In another cross-sectional study of older adults with functional limitations, greater participation in fitness programs and social activities was shown for those living in neighbourhoods with parks and walking areas (White et al., 2010). Finally, in a cross-sectional study investigating the association between neighbourhood vegetation and participation in physical activity in older adults, physical function was shown to modify this relationship, though the direct association between greenness and physical functioning was not reported (Gong et al., 2014).

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the association between blue space exposure and physical functioning. Therefore, we could not compare our results to previous findings. The lack of association might have been, partly, the result of the small number of participants living close to blue spaces in our study population. Furthermore, we did not find any significant association with the distance to green spaces, separately, either. Again this might have been the result of a smaller number of participants living close to green spaces in comparison to the number of those living close to any natural environment.

Our results suggested sex differences in the association between natural environments and physical functioning, though the observed pattern was mixed; for residential surrounding greenness, we observed a stronger association with the 5-year difference in walking speed among men, while for distance to natural environments, this association was stronger among women. Several studies found that women were at higher risk of poor physical functioning than men (Ferrucci et al., 2000; Rooth et al., 2016). Furthermore, the association between natural environments and health may be modified by sex; for instance, women may spend more time in the residential area (and thus have more exposure to neighbourhood greenspace). Furthermore, men and women may have different use of green space, e.g. men were found more likely to do vigorous physical activity in parks than women (Cohen et al., 2007). Previous studies found sex differences in associations with physical functioning as well. For example, a stronger association between green space and frailty was found in men than in women (Yu et al., 2018), and a lower land use mix was associated with a lower walking speed in men while it was associated with lower grip strength in women (Soma et al., 2017). In addition, stratifying the analysis by socioeconomic indicators showed some indication for stronger associations in participants living in more deprived neighbourhoods. Previous studies found that the association between green space and health may be stronger among lower socioeconomic groups (Gascon et al., 2015; Maas et al., 2009), but this has not been shown consistently (Vienneau et al., 2017).

4.2. Potential underlying mechanisms

A number of mechanisms have been proposed for the association between exposure to natural environments and health, which could also be relevant in terms of such an association with physical functioning. In this study, we investigated mediation by physical activity, gardening, air pollution, mental health, and social functioning, and found some of them to mediate the association with upper limb strength, as measured by grip strength, or motor function, as measured by walking speed. First, physical activity plays an important role in maintaining physical functioning in older adults (Fielding et al., 2017), while a recent review found evidence for a beneficial association of parks, public open space, and greenery with self-reported physical activity and walking in older adults (Barnett et al., 2017). However, in our study, we did not observe mediation by physical activity and gardening in the associations between natural environments and the decline in physical functioning. Second, greener neighbourhoods are reported to foster social cohesion and social support (de Vries et al., 2013), while social status and loneliness may be important determinants of functional status decline in older adults (Chen et al., 2012; Perissinotto et al., 2012). In our study, social functioning was found to mediate the association between residential surrounding greenness and distance to any natural environment and the decline in walking speed. In addition, exposure to green space may present benefits for mental health (Gascon et al,, 2015), while depressive symptoms have been associated with higher risk of functional status decline (Stuck et al., 1999). In our study, we found that mental health may have mediated a small proportion of the association between distance to any natural environment and the decline in walking speed. Furthermore, exposure to natural environments has been found to reduce stress (Gong et al., 2016), which may benefit physical functioning (Hansen et al., 2014; Kulmala et al., 2014; Nilsen et al., 2016). However, we did not have data available on this mediator. Lastly, greenness can reduce levels of noise and air pollution (Dadvand et al., 2015b, 2012), while air pollution may be associated to a faster decline in physical ability (Weuve et al., 2016). However, air pollution was not found to mediate the associations between natural environments and the decline in physical functioning scores in this study.

4.3. Limitations

First, the Whitehall II study consisted of civil servants and underrepresented women and ethnic minorities, which may have affected the generalisability of the findings. Second, using satellite-based vegetation indices for the assessment of residential surrounding greenness enabled us to take into account small green spaces in a standardized way. However, we could not use buffers smaller than 500 m due to the resolution of our EVI and NDVI maps and because of the use of the postcode centroid as the residential location of the participants. Greenness within smaller buffers could be an indicator for green space closer to home and more visual access, which could be used to test for other pathways underlying benefits of natural environments. Furthermore, our estimate of distance to natural environment was an indicator of access to natural environments that were larger than 25 ha and did not consider smaller natural environments. Additionally, these indicators of green space exposure are not informative about the type or quality of vegetation or land-cover or give any information on use of green spaces which could have affected our observed associations. However, a study from Germany found that the walking distance to natural environments was associated with its use frequency (Vblker et al., 2018). Moreover, we could not characterize exposure to natural environments at the workplace or other locations where participants might have spent significant amount of time. However, many of the Whitehall II participants retired before or during the study period and older adults generally tend to be more bound to their direct neighbourhood environment (Yen et al., 2009). Moreover, the use of buffers around postcode centroids might have led to exposure misclassification, especially in large postcode areas that are more common in rural areas. However, excluding participants living in rural areas did not change the results notably. Lastly, limitations in the characterization of mediators might have reduced the ability to detect mediation. The indicators of physical activity, gardening, mental health, and social functioning were based on self-reported data. In addition, social functioning was assessed with only two questions that did not include factors as social support or social cohesion in the neighbourhood. Furthermore, our exposure assessment of air pollution was based on modelled PM2.5 with a coarse spatial resolution. This resulted in an indicator of background air pollution, while traffic-related pollution may be more important in explaining the association (Dadvand et al., 2015a). In addition to air pollution, noise may also be an important mediator in the association between natural environments and physical functioning, but was not measured in our study.

4.4. Conclusions

In a longitudinal study of older adults, we observed that higher residential surrounding greenness and proximity to natural environments was associated with slower decline in physical functioning. Considering the ageing population (World Health Organization, 2015b), the identification of factors that promote healthy ageing is of increasing importance. Reaching optimal levels of physical functioning and maintaining these levels is essential in maintaining quality of life and independent living at older age (Sayer et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2015a) and has been associated with lower morbidity and mortality (Celis-Morales et al., 2018). Our findings, if confirmed by future studies, provide further evidence for the benefits of exposure to natural environments in the ageing population. Future studies are needed that are situated in other settings and climates and further investigate the pathways between the exposure to natural environments and health, the potential modifying effect of sex and socioeconomic status, and the specific characteristics of natural environments that have the largest impact on maintaining physical functioning at older age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in the Whitehall II Study, as well as all Whitehall II research scientists, study and data managers and clinical and administrative staff who make the study possible. We are grateful to Aida Sanchez for managing and providing data.

The MODIS vegetation products were retrieved from the online Data Pool, courtesy of the NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/.

The UK Medical Research Council (MRC MR/R024227/1), British Heart Foundation (RG/13/2/30098), and the US National Institute on Ageing (R01AG013196; R01AG034454; R01AG056477) have supported collection of data in the Whitehall II Study. Payam Dadvand [RYC-2012–10995] and Cathryn Tonne [RYC-2015–17402] are funded by Ramón y Cajal fellowships awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. The funders have not been involved in any part of the study design or reporting.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.046.

References

- Barnett DW, Barnett A, Nathan A, Van Cauwenberg J, Cerin E, 2017. Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 14,103 10.1186/sl2966-017-0558-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA, 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard JR, Petitot C, 2010. Ageing and urbanization: can cities be designed to foster active ageing? Public Health Rev. 32, 427–450. 10.1007/BF03391610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bos EH, van der Meulen L, Wichers M, Jeronimus BF, 2016. A primrose path? Moderating effects of age and gender in the association between green space and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13 10.3390/ijerphl3050492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celis-Morales CA, Welsh P, Lyall DM, Steell L, Petermann F, Anderson J, Iliodromiti S, Sillars A, Graham N, Mackay DF, Pell JP, Gill JMR, Sattar N, Gray SR, 2018. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer outcomes and all cause mortality: prospective cohort study of half a million UK Biobank participants. BMJ 361 10.1136/bmj.kl651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerin E, Nathan A, van Cauwenberg J, Barnett DW, Barnett A, 2017, The neighbourhood physical environment and active travel in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys, Act. 14, 15 10.1186/sl2966-017-0471-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Covinsky KE, Stijacic Cenzer I, Adler N, Williams BA, 2012. Subjective social status and functional decline in older adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27, 693–699. 10.1007/sll606-011-1963-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, McKenzie TL, Sehgal A, Williamson S, Golinelli D, Lurie N, 2007. Contribution of public parks to physical activity. Am, J. Public Health 97 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R, Mortality Review Group, 2010, Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 341 10.1136/bmj.c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, de Nazelle A, Triguero-Mas M, Schembari A, Cirach M, Amoly E, Figueras F, Basagana X, Ostro B, Nieuwenhuijsen M, 2012. Surrounding greenness and exposure to air pollution during pregnancy: an analysis of personal monitoring data. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 1286–1290. https://doi.org/101289/ehp.l104609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Esnaola M, Forns J, Basagana X, Alvarez- Pedrerol M, Rivas I, López-Vicente M, De Castro Pascual M, Su J, Jerrett M, Querol X, Sunyer J, 2015a. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 7937–7942. 10.1073/pnas.1503402112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, Rivas I, Basagana X, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Su J, De Castro Pascual M, Amato F, Jerret M, Querol X, Sunyer J, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2015b. The association between greenness and traffic-related air pollution at schools. Sci. Total Environ. 523, 59–63, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, Bartoll X, Basagana X, Dalmau-Bueno A, Martinez D, Ambros A, Cirach M, Triguero-Mas M, Gascon M, Borrell C, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2016. Green spaces and general health: roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environ. Int. 91, 161–167. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bell S, Graham H, Jarvis S, White P, 2017. The importance of nature in mediating social and psychological benefits associated with visits to freshwater blue space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 167, 118–127. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Keijzer C, Tonne C, Basagana X, Valentín A, Singh-Manoux A, Alonso J, Antó JM, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Sunyer J, Dadvand P, 2018. Residential surrounding greenness and cognitive decline: a 10-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 126 10.1289/EHP2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries S, van Dillen SME, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P, 2013. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc. Sci. Med. 94, 26–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries S, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, van Wezep M, Hermans T, de Graaf R, 2016. Local availability of green and blue space and prevalence of common mental disorders in the Netherlands. BJPsych Open 2, 366–372. 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey S, Devine MT, Gillespie T, Lyons S, Nolan A, 2018. Coastal blue space and depression in older adults. Health Place 54, 110–117. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didan K, 2015. MOD13Q1 MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250m SIN Grid V006 [Data Set] [WWW Document]. 10.5067/MODIS/MOD13Q1.006. [DOI]

- Dzhambov AM, Dimitrova DD, 2014. Urban green spaces’ effectiveness as a psychological buffer for the negative health impact of noise pollution: a systematic review. Noise Health 16, 157–165. 10.4103/1463-1741.134916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency, 2017. What is Open Space/Green Space? [WWW Document]. https://www3.epa.gov/regionl/eco/uep/openspace.html, Accessed date: 1 October 2018.

- European Environment Agency, 2007, CLC2006 Technical Guidelines [WWW Document]. 10.2800/12134. [DOI]

- Expert Group on the Urban Environment, 2000. Towards a Local Sustainability Profile - European Common Indicators [WWW Document]. URL. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/83090cd3-b9b2-4d81-9c8b-0e58a020f2e5, Accessed date: 10 July 2018.

- Ferrucci L, Penninx BW, Leveille SG, Corti MC, Pahor M, Wallace R, Harris TB, Havlik RJ, Guralnik JM, 2000. Characteristics of nondisabled older persons who perform poorly in objective tests of lower extremity function. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48, 1102–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding RA, Guralnik JM, King AC, Pahor M, McDermott MM, Tudor-Locke C, Manini TM, Glynn NW, Marsh AP, Axtell RS, Hsu FC, Rejeski WJ, group, for the L. study, 2017. Dose of physical activity, physical functioning and disability risk in mobility-limited older adults: results from the LIFE study randomized trial. PLoS One 12, e0182155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong KC, Hart JE, James P, 2018. A review of epidemiologic studies on greenness and health: updated literature through 2017, Curr. Environ. Heal. Reports 5, 77–87. 10.1007/s40572-018-0179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martinez D, Dadvand P, Forns J, Plasencia A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2015. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 4354–4379. 10.3390/ijerphl20404354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martinez D, Dadvand P, Rojas-Rueda D, Plasencia A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2016. Residential green spaces and mortality: a systematic review. Environ. Int. 86, 60–67. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon M, Zijlema W, Vert C, White MP, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2017. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220, 1207–122L 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y t Gallacher J, Palmer S, Fone D, 2014. Neighbourhood green space, physical function and participation in physical activities among elderly men: the Caerphilly prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 11,1–11. 10.1186/1479-5868-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Palmer S, Gallacher J, Marsden T, Fone D, 2016. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ, Int. 96, 48–57. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic A, Davies K, Jagger C, Kirkwood TBL, Syddall HE, Sayer AA, 2016. Grip strength decline and its determinants in the very old: longitudinal findings from the Newcastle 85+ study. PLoS One 11, e0163183. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB, 1994. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 49, M85–M94, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffner M, Jackson-Smith D, Buchert M, Risley J, 2017. Accessing blue spaces: social and geographic factors structuring familiarity with, use of, and appreciation of urban waterways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 167, 136–146. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen ÅM, Darsø L, Manty M, Nilsson C, Christensen U, Lund R, Holtermann A, Avlund K, 2014. Psychosocial factors at work and the development of mobility limitations among adults in Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 42, 417–424, 10.1177/1403494814527526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A, Sallis JF, King AC, Conway TL, Saelees B, Cain KL, Fox EH, Frank LD, 2018. Linking green space to neighborhood social capital in older adults: the role of perceived safety. Soc. Sci. Med. 207, 38–45. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Banay RF, Hart JE, Laden F, 2015. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr, Epidemiol. Reports 2, 131–142. 10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, 2007. The new dynamics of ageing (NDA) preparatory network: a life course approach to healthy aging, frailty, and capability. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 717–721. 10.1093/gerona/62.7-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Karunananthan S, Bergman H, Cooper R, 2014. A life-course approach to healthy ageing: maintaining physical capability. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 73, 237–248. 10.1017/S0029665113003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulmala J, Hinrichs T, Tormakangas T, von Bonsdorff MB, von Bonsdorff ME, Nygard C-H, Klockars M, Seitsamo J, Ilmarinen J, Rantanen T, 2014. Work- related stress in midlife is associated with higher number of mobility limitation in older age-results from the FLAME study. Age (Dordr.) 36, 9722, 10.1007/sl1357-014-9722-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, 2014. Data Pool [WWW Document]. URL. https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/data_access/data_pool, Accessed date: 7 November 2016.

- Lara J, Cooper R, Nissan J, Ginty AT, Khaw KT, Deary IJ, Lord JM, Kuh D, Mathers JC, 2015. A proposed panel of biomarkers of healthy ageing, BMC Med. 13, 222 10.1186/sl2916-015-0470-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas J, Verheij RA, de Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P, Schellevis FG, Groenewegen PP, 2009. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 63, 967–973. 10.1136/jech.2008.079038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Brunner E, 2005. Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34, 251–256. 10.1093/ije/dyh372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, 2001. Geography for the 2001 Census in England and Wales [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan RRC, Prady SL, Smith G, Fairley L Cabieses B, Gidlow C, Wright J, Dadvand P, van Gent D, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2016. The association between green space and depressive symptoms in pregnant women: moderating roles of socioeconomic status and physical activity, J. Epidemiol. Community Health 70, 253–259. 10.1136/jech-2015-205954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MODIS, 2017. Data Products [WWW Document]. URL. https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/dataprod/, Accessed date: 12 December 2016.

- Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Khreis H, Triguero-Mas M, Gascon M, Dadvand P, 2017. Fifty shades of green: pathway to healthy urban living. Epidemiology 28, 63–71. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen C, Agahi N, Kareholt I,, 2016. Work stressors in late midlife and physical functioning in old age. J. Aging Health 29, 893–911. 10.1177/0898264316654673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutsford D, Pearson AL, Kingham S, Reitsma F, 2016. Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city. Health Place 39, 70–78. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics, 2011. 2011 Census: Population and Household Estimates for Small Areas in England and Wales, March 2011 [WWW Document]. URL. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/2011censuspopulationandhouseholdestimatesforsmallareasinenglandandwales/2012-11-23.

- Office for National Statistics, 2013. 2011 Census: Headcounts and Household Estimates for Postcodes in England and Wales [WWW Document]. URL. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/2011censusheadcountsandhouseholdestimatesforpostcodesinenglandandwales, Accessed date: 7 June 2017.

- Office for National Statistics, 2017. Geography [WWW Document]. URL. https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography, Accessed date: 16 December 2016.

- Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE, 2012. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch. Intern. Med, 172, 1078–1083. https://doi.org/l0.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, JM G, Foley D, et al. , 1999. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA 281, 558–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson EA, Mitchell R, 2010. Gender differences in relationships between urban green space and health in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 568–575. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooth V, van Oostrom SH, Deeg DJH, Verschuren WMM, Picavet HSJ, 2016. Common trajectories of physical functioning in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Age Ageing 45, 382–388. https://doi.org/l0,1093/ageing/afw018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouxel P, Webb E, Chandola T, 2017. Does public transport use prevent declines in walking speed among older adults living in England? A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 7, e017702. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabia S, Elbaz A, Rouveau N, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A, 2014. Cumulative associations between midlife health behaviors and physical functioning in early old age: a 17-year prospective cohort study. J, Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 1860–1868. https://doi.org/10.Ill1/jgs.13071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ,, Dennison EM, Roberts HC, Cooper C, 2006, Is grip strength associated with health-related quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing 35, 409–415. 10.1093/ageing/afl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schootman M, Andresen EM, Wolinsky FD, Miller JP, Yan Y, Miller DK, 2010. Neighborhood conditions, diabetes, and risk of lower-body functional limitations among middle-aged African Americans: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 10, 283, 10.1186/1471-2458-10-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Kauffmann F, Elbaz A, Ankri J, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Sabia S, 2011. Association of lung function with physical, mental and cognitive function in early old age. Age (Omaha) 33, 385–392. 10.1007/si1357-010-9189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma Y, Tsunoda K, Kitano N, Jindo T, Tsuji T, Saghazadeh M, Okura T, 2017. Relationship between built environment attributes and physical function in Japanese comm unity-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17, 382–390. 10.1111/ggi.l2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockton JC, Duke-Williams O, Stamatakis E, Mindell JS, Brunner EJ, Shelton NJ, 2016. Development of a novel walkability index for London, United Kingdom: cross-sectional application to the Whitehall II Study. BMC Public Health 16, 416 10.1186/sl2889-016-3012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC, 1999. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 48, 445–469. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingley D, Yamamoto T Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K, 2014. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat, Softw. 1–38. 10.18637/jss.v059i05,Artie.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triguero-Mas M, Dadvand P, Cirach M, Martinez D, Medina A, Mompart A, Basagana X,, Grazuleviciene R, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, 2015. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environ, Int 77, 35–41. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, 2015. World Population Ageing [WWW Document]. URL. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf, Accessed date: 10 July 2018.

- Van Cauwenberg J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Meester F, Van Dyck D, Salmon J, Clarys P, Deforche B, 2011. Relationship between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Health Place 17, 458–469. https://doi.org/l0.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vienneau D, de Hoogh K, Faeh D, Kaufmann M, Wunderli JM, Roosli M, 2017. More than clean air and tranquillity: residential green is independently associated with decreasing mortality. Environ. Int. 108, 176–184. 10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt S, Mielck A, Berger U, Grill E, Peters A, Döring A, Holle R, Strobl R, Zimmermann A-K, Linkohr B, Wolf K, Kneißl K, Maier W, 2015. Neighborhood and healthy aging in a German city: distances to green space and senior service centers and their associations with physical constitution, disability, and health-related quality of life. Eur. J. Ageing 12, 273–283. 10.1007/sl0433-015-0345-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völker S, Heiler A, Pollmann T, Claßen T, Hornberg C, Kistemann T, 2018. Do perceived walking distance to and use of urban blue spaces affect self-reported physical and mental health? Urban For. Urban Green. 29, 1–9. 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weier J, Herring D, 2000. Measuring Vegetation (NDVI&EVI). [WWW Document]. URL. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/MeasuringVegetation/, Accessed date: 3 July 2016, [Google Scholar]

- Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, Beck TL, Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Mendes De Leon CF, 2012. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology 23, 119–128. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weuve J, Kaufman JD, Szpiro AA, Curl C, Puett RC, Beck T, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF, 2016, Exposure to traffic-related air pollution in relation to progression in physical disability among older adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1000–1008. 10.1289/ehp.1510089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DK, Jette AM, Felson DT, LaValley MP, Lewis CE, Tomer JC, Nevitt MC, Keysor JJ, 2010. Are features of the neighborhood environment associated with disability in older adults? Disabil. Rehabil. 32, 639–645. 10.3109/09638280903254547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MP, Elliott LR, Taylor T, Wheeler BW, Spencer A, Bone A, Depledge MH, Fleming LE, 2016. Recreational physical activity in natural environments and implications for health: a population based cross-sectional study in England. Prev. Med. 91, 383–388. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.023.(Baltim). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2015a. World Report on Ageing and Health. Geneva.

- World Health Organization, 2015b. Ageing and Health [WWW Document]. URL. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs404/en/, Accessed date: 27 July 2016.

- Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L, 2009. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 37, 455–463. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009,06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Wang D, Leung J, Lau K, Kwok T, Woo J, 2018. Is neighborhood green space associated with less frailty? Evidence from the Mr. and Ms. Os (Hong Kong) study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc, 10.1016/jjamda.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlema WL, Triguero-Mas M, Smith G, Cirach M, Martinez D, Dadvand P, Gascon M, Jones M, Gidlow C, Hurst G,, Masterson D, Ellis N, van den Berg M, Maas J, van Kamp I, van den Hazel P, Kruize H, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Julvez J, 2017. The relationship between natural outdoor environments and cognitive functioning and its mediators. Environ. Res, 155, 268–275, 10.1016/j.envres.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.