Abstract

Introduction

Child maltreatment and other traumatic events can have serious long-term physical, social and emotional effects, including a cluster of distress symptoms recognised as ‘complex trauma’. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Aboriginal) people are also affected by legacies of historical trauma and loss. Trauma responses may be triggered during the transition to parenting in the perinatal period. Conversely, becoming a parent offers a unique life-course opportunity for healing and prevention of intergenerational transmission of trauma. This paper outlines a conceptual framework and protocol for an Aboriginal-led, community-based participatory action research (action research) project which aims to co-design safe, acceptable and feasible perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.

Methods and analysis

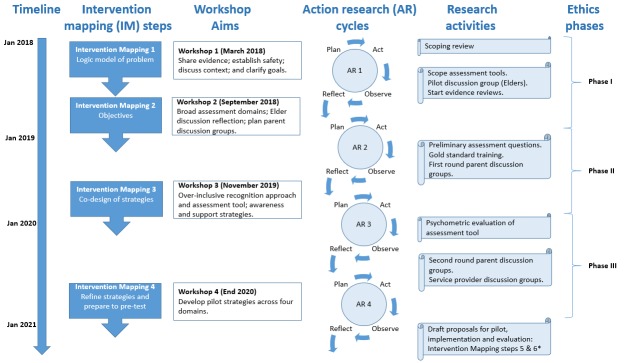

This formative research project is being conducted in three Australian jurisdictions (Northern Territory, South Australia and Victoria) with key stakeholders from all national jurisdictions. Four action research cycles incorporate mixed methods research activities including evidence reviews, parent and service provider discussion groups, development and psychometric evaluation of a recognition and assessment process and drafting proposals for pilot, implementation and evaluation. Reflection and planning stages of four action research cycles will be undertaken in four key stakeholder workshops aligned with the first four Intervention Mapping steps to prepare programme plans.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics and dissemination protocols are consistent with the National Health and Medical Research Council Indigenous Research Excellence criteria of engagement, benefit, transferability and capacity-building. A conceptual framework has been developed to promote the application of core values of safety, trustworthiness, empowerment, collaboration, culture, holism, compassion and reciprocity. These include related principles and accompanying reflective questions to guide research decisions.

Keywords: complex trauma, perinatal, parents, indigenous, community-based participatory action research, intergenerational

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Demonstrates a comprehensive formative action research process to co-design acceptable and feasible perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.

A conceptual framework to guide this project includes core values of safety, trustworthiness, empowerment, collaboration, culture, holism, compassion and reciprocity.

Indigenous Research Excellence criteria influence ethics and dissemination protocols.

Assessment of safety, acceptability and feasibility of an awareness, recognition and assessment process for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma in three Australian jurisdictions.

Formative study to set the foundation for implementation and evaluation of the co-designed support strategies.

Introduction

Child maltreatment and other adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are an international health priority,1 contributing to a wide range of long-lasting physical, social and emotional health issues.1–7 There is growing international consensus to recognise a cluster of distress symptoms people may experience following childhood exposure to severe threats, called complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (complex trauma). This classification describes a symptom profile that typically follows traumatic experiences of a prolonged nature or repeated adverse events from which separation is not possible.8 These symptoms include ‘affect/emotional dysregulation’, ‘negative self-concept’ and ‘relational disturbances’, in addition to previously recognised PTSD symptoms of ‘re-experiencing the events (triggers), avoidance and a sense of threat’.8 These traumatic experiences often involve interpersonal violation and occur within childhood family or institutional care giving systems9 (eg, childhood abuse, severe domestic violence, torture or slavery).8 Broader societal factors can amplify or counteract the impact of potentially traumatic experiences. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Aboriginal) people in Australia are particularly affected by complex trauma, following a legacy of historical trauma,10 11 which includes state-sanctioned systematic removal of Aboriginal children from their families and ongoing discrimination.12 While community cohesion, access to services and cultural continuity have been shown to have a protective effect for some trauma-related outcomes among Aboriginal people,13 within the context of colonisation socioecological risk factors experienced by many Aboriginal communities are likely to amplify rather than counteract the effects of complex trauma originating from childhood experiences.14 15 There are strong associations between child maltreatment and a wide range of physical and psychological morbidities16 and risk factors, including smoking, eating disorders, unplanned pregnancies6 17 and adverse birth outcomes.18 Critically, these long-lasting relational effects can impede the capacity to nurture and care for children, leading to ‘intergenerational cycles’ of trauma.19 Experiences of child maltreatment are not equally distributed across general populations and WHO uses a socioecological framework20 to highlight the links between higher levels of social adversity and increased rates of child maltreatment experienced in some communities worldwide. These factors also interact and create a ‘compounding intergenerational effect’ on health inequities. As such, this is a crucial issue for improving health equity worldwide. ‘Life course approaches’ are central to understanding complex intergenerational causal pathways and also for identifying critical ‘intervention points’ for prevention and support to improve health equity.21

The transition to parenting during the perinatal period (pregnancy to 2 years after birth) is a critical ‘life course’ transition for parents who have experienced complex trauma.22 Trauma responses may be triggered by the intimate nature of experiences associated with pregnancy, birth and breast feeding23; and the attachment needs of the infant.24 The long-lasting relational effects can impede the capacity of parents to nurture and care for their children, and may contribute to ‘intergenerational cycles’ of trauma.19 25 26

Conversely, the transition to parenthood offers a unique life-course opportunity for emotional healing and development.27 28 A positive strengths-based focus during this often-optimistic period has the potential to transform the ‘vicious cycle’ of intergenerational trauma into a ‘virtuous cycle’ that contains positively reinforcing elements. When parents can manage trauma responses and provide love and nurturing care, this love is returned by children, and trauma responses can be relearnt, promoting healing in the parent,29 and optimal development for the infant.30 31 It is this concept which has inspired the title for this project—‘Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future’.

Frequent scheduled contacts with perinatal care providers before and after childbirth and across the first 2 years offer an opportunity for providing comprehensive system-based supports for people experiencing complex trauma during this period. This is particularly important because it may be the first time many of this predominantly young childbearing population have had contact with universal health services since childhood. Despite these clear risks and opportunities, few interventions are available for parents with specific histories of maltreatment,23 32 33 and there are no systematic, culturally informed processes or evidence of effective strategies to identify and support Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.34

The benefits of involving communities in co-designing healthcare strategies are increasingly recognised.35 36 This is critical in the perinatal period for Aboriginal families experiencing complex trauma for several reasons. First, there is very limited evidence of effective interventions internationally. Australian guidelines for the treatment of complex trauma and trauma-informed care emphasise the need for complex trauma to be understood within relational networks and social environments if it is to be adequately addressed.9 Aboriginal Australians, despite suffering great disadvantage and adversity, demonstrate strong resistance to those actions that are foreign to Aboriginal culture, including separation from families, discrimination and removal from country. Thus, we will engage in respectful collaborative research with and alongside Aboriginal people and keep Aboriginal people’s strengths and protective factors to the fore. These strengths include rich cultural relationship and kinship networks that foster relatedness and connectedness for children.37 Collaboration with local Aboriginal leaders and Aboriginal organisations has been shown to be critical in adapting child trauma therapies among other Indigenous communities.38

Second, Aboriginal conceptualisations of social and emotional well-being are holistic and incorporate connection to land, culture, spirituality, family and community; all of which are impacted by complex trauma, which is sometimes referred to as ‘relational trauma’.39 The rich relational understandings of well-being may offer important insights for other Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

Third, there are risks associated with identifying parents with complex trauma. Labelling individuals as ‘at risk’ has the potential to undermine parents’ existing resilience and coping skills, and trigger inappropriate notifications to a potentially punitive child protection system. These concerns are particularly salient for Aboriginal communities, with the history of colonisation and forced child removals from families, and ongoing high rates of infants being removed from Aborginal families,40 which have had devastating ongoing intergenerational impacts. Finally, despite a history of childhood adversity, most parents are able to nurture and care for their children.41 Evidence suggests that examining these ‘cycles of discontinuity’ are an important place to start to illuminate innovative strategies for support.42

Aims and objectives

Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future is a formative Aboriginal-led, community-based participatory action research (action research) project, which aims to co-design perinatal strategies to support Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma. There is currently insufficient evidence to identify potentially acceptable, feasible and effective strategies to support Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma, hence the focus of this project is formative research.

The expected outcomes of the project are to identify strategies that are considered acceptable to Aboriginal parents and feasible for service providers. Piloting, implementation and evaluation of the effectiveness of these perinatal strategies will be the subject of a sequential project following this formative design stage.

The co-design strategies aim to improve four key domains of perinatal care:

Awareness of the impact of trauma on parents or ‘trauma-informed’ perinatal care to minimise the risks of triggering and compounding trauma responses.

Safe recognition of parents who may benefit from assessment and support, with processes to reduce risk of harm.

Assessment of complex trauma symptoms to accurately identify parents experiencing distress.

Support strategies for parents to heal, including psychological/emotional, social, cultural and physical strategies.

The purpose of this protocol paper is to illustrate the processes, frameworks and methods used by an Aboriginal-led research team to generate rigorous context-relevant strategies, while also fostering cultural and emotional safety for participants, partners, research staff and the broader Aboriginal community. This paper includes an outline of the following elements:

Community involvement in the project.

Conceptual framework for developing safe research processes.

Research activities within the four action research cycles and Intervention Mapping (IM) steps.

Ethical considerations and research dissemination plans.

Due to the evolving nature of action research and co-design research, submissions for Human Resarch Ethics Committee (HREC) approval are planned in three distinct ‘ethics phases’, following key stakeholder co-design workshops one, two and three. At the time of submitting this protocol, phase I and II HREC approval had been granted, and HREC submission is planned for phase III in late 2019. Therefore, this protocol includes a detailed description of ‘phase I and II’ activities, with a brief outline only of anticipated phase III activities (highlighted in text).

Methods and analysis

Patient and public (community) involvement

This project involves Aboriginal people at every level, and a detailed description is outlined in the National Health and Medical Reserch Council (NHMRC) Indigenous Research Excellence Criteria (see online supplementary file 1). In summary, the majority of the investigator team are Aboriginal with extensive expertise in this area. The need for this research has been identified in national Aboriginal conferences and formally supported by three Aboriginal community controlled ‘peak bodies’, who play a leading role in Aboriginal health initiatives43: the Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of Northern Territory; the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia and the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation.

bmjopen-2018-028397supp001.pdf (94.1KB, pdf)

We are using an action research model to ensure ongoing community involvement is built into the research plan, including refinement of the research questions. Action research draws on phenomenology and critical theory to generate constructivist grounded theory using mixed methods.44 It involves a practical community-based focus and collaboration for action.45 The focus of the first year has been meaningful community engagement to enable action research. We have established formal partnerships and recognise the leadership of five partner service organisations with this project, including: Central Australian Aboriginal Congress (Northern Territory); Nunkuwarrin Yunti of South Australia and Women’s and Children’s Health Network (South Australia); the Royal Women’s Hospital (Victoria) and the Bouverie Family Healing Centre (Victoria).

Participants in this study include Aboriginal parents, perinatal service providers, Aboriginal elders and key stakeholders (service providers, researchers, policy-makers and community leaders working to address complex trauma). Participants are required to provide informed consent prior to participating in study activities, and draft findings of each activity are provided to particpants for feedback, prior to broader community dissemination. We invite key stakeholders from all Australian jurisdictions to participate in the four co-design workshops to enable broader national collaboration in planning for subsequent programme pilot, implementation and evaluation.

Conceptual framework: developing safe research processes

To articulate the values for the project and address risks and contextual complexities, we have developed a conceptual framework (figure 1) drawing on holistic Aboriginal constructs of social and emotional well-being. Protocols that have been critical for informing this conceptual framework include:

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for co-designing perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.

Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF),46 ’an over-arching structure for identifying patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubling behaviour, as an alternative to psychiatric diagnosis and classification’ (p. 5). We will incorporate the PTMF by reframing behaviours related to complex trauma as normal self-protective responses to threatening situations rather than pathological deficits.

Principles for population-based screening 47 to assess the benefits, risks, costs, acceptability, accuracy and potential risk of harms resulting from recognising and assessing parents experiencing complex trauma.

Indigenous research methodologies 48 that involve privileging Aboriginal worldviews, self-determination and Aboriginal community control.

The conceptual framework incorporates two elements:

Four main domains of awareness, recognition, assessment and support.

Eight core values with related principles and questions.

Four main domains of recognition, assessment, awareness and support

The four main domains were developed during the early community engagement stages of the project which revealed concerns about the use of language such as ‘screening’ and ‘intervention’, which implies ‘something is wrong’ with a person, and is not consistent with PTMF framing of trauma to ask ‘what has happened to you’.46 There are also sensitivities in the context of Aboriginal communities in Australia, with controversial Government ‘interventions’ imposed on Aboriginal communities. The domains of ‘recognition’ and ‘assessment’ broadly align with ‘screening’ strategies that incorporate a safe and feasible two-tiered process for care providers to recognise parents who may require more in-depth assessment for complex trauma; and ‘intervention’ approaches to improve trauma-informed perinatal care and minimise the risks of re-traumatising parents (awareness), and provide trauma-specific support.

Eight core values with related principles and questions

Using online searches and team members’ clinical knowledge, we identified seven frameworks that included trauma-informed values and principles.9 49–54 These values and principles were mapped and consensus was reached by the project team for eight core values: safety, trustworthiness, empowerment, collaboration, culture, holism, compassion and reciprocity. Each contains action-oriented principles that enable the core values to be realised, and are accompanied by questions developed to aid reflection on whether the activity under consideration is consistent with the core value (see online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2018-028397supp002.pdf (171.4KB, pdf)

Setting

Research activities will be conducted in three of seven Australian jurisdictions selected on the basis of existing research relationships and expressed interest by key stakeholders: Northern Territory, South Australia and Victoria. Approximately 23% of Australian Aboriginal people live in these three jursidictions across mixed urban, rural and remote demographic contexts.55

Data storage and triangulation

All data will be securely stored using REDCap software,56 and accessible only to members of the project team. Wherever possible, data will be stored in de-identified form. However, where concerns exist about the health of a participant, the safety plans and responses relating to that participant will be stored to enable appropriate follow-up by healthcare professionals.

Multiple data sources will be triangulated within this project (as described below), which will increase confidence in the findings through the confirmation of proposed ideas from two or more independent sources.57 Data collection tools are designed to progressively inform the co-design of safe, acceptable and feasible perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies.

Research approaches

An Intervention Mapping (IM) approach58 is used in this project to frame the co-design process. IM uses ‘theory and evidence as foundations for taking an ecological approach to assessing and intervening in health problems and engendering community participation’ (p. 7). This formative research project addresses IM steps one to four, which are aligned with four key stakeholder workshops (figure 2). IM steps five and six (implementation and evaluation)* will form the basis of a subsequent project.

Figure 2.

‘Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future’ research plan.

Action research processes will be used to foster an iterative co-design process comprising four ‘plan-act-observe-reflect’ cycles. The ‘reflect’ and ‘plan’ action research stages will be conducted in four key stakeholder workshops, which align with the first four steps of IM.58 The ‘act’ and ‘observe’ stages of the action research cycles involve a series of mixed method ‘research activities’ that will be refined in each ‘reflect’ and ‘plan’ stage within the workshops. We outline research activities within each of the IM steps and action research cycles below. We note that HREC approval has been received for ‘phase I and II’, but that activities planned for a ‘phase III’ HREC submission have not been approved and are subject to review (thus briefly outlined here).

1. Action research cycle and IM step 1: developing relationships and understanding the problem

This first action research cycle includes: (1a) evidence reviews, (1b) the first key stakeholder workshop, aligned with IM step 1, (1c) mapping domains included within existing assessment tools and (d) a pilot discussion group with senior Aboriginal women. Each of these activities is described further below:

1a: Evidence reviews: scoping review and evidence map of studies involving parents in the perinatal period with a history of childhood maltreatment; and comprehensive systematic reviews

The purpose of the scoping review and evidence map was to identify preliminary evidence, and enable development of protocols for a series of comprehensive systematic reviews (see online supplementary file 3). The scoping review findings have been incorporated into subsequent research activities, including: presentation at workshop 1; generating ‘cards’ of key issues described by parents elsewhere in discussion groups with senior Aboriginal women and parents and scoping ‘strengths’ to be included in an assessment tool. The scoping review has also been critical to refine the search strategy for a series of comprehensive reviews.59

bmjopen-2018-028397supp003.pdf (259.9KB, pdf)

1b: Key stakeholder workshop 1

The purpose of workshop 1, aligned with IM step 1 (understanding the problem and developing a logic model), was to provide a forum for preliminary engagement with key stakeholders to:

Introduce the rationale for the project and share preliminary evidence from the scoping review to enable informed discussion and clarification of goals (logic model).

Establish safety protocols for working with parents, service providers, key stakeholders, team members and the wider Aboriginal community.

Understand the context and issues for key stakeholders regarding identifying and supporting Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.

Recruitment and sample: key stakeholders were identified through consultation and using a snowballing recruitment process of advertising about the project through Aboriginal and academic health networks, professional meetings and conferences. People expressing interest in the project were included in a key stakeholder email list, and received updates about the project and invitations to the workshops which were cost-free to enable attendance. Approximately 40 people participated in workshop 1.

Data collection and analysis: a facilitation guide was developed to address the aims of the workshop (see online supplementary file 4) and promote a culturally and emotionally safe environment. Strategies to support any participants who may experience ‘triggers’ themselves (ie, trauma responses) during the workshop and psychological support were provided.

bmjopen-2018-028397supp004.pdf (280.6KB, pdf)

Data were collected in the form of workshop materials developed by participants (butchers paper notes) and observer notetakers. Data were collated into themes and circulated to workshop participants to check the accuracy of the interpretations. A summary of the workshop is available on the project website.60 In keeping with the action research process, findings were reflected on and used for planning workshop 2 (2a) and developing the conceptual framework and a detailed safety protocol.

1 c: Scoping assessment tools

The purpose of scoping existing assessment tools for complex trauma and/or a parental history of child maltreatment, and for assessing resilience and strengths was to:

Map the range of areas of distress included within existing assessment tools.

Enable informed consultation with key stakeholders about each of the main areas of distress and if all important areas were considered.

Map domains of resilience and strengths.

Data collection and analysis: distress assessment tools were identified through the scoping review and consultation. For each tool, data were extracted on: description of the tool; key references; validation information; symptoms of distress and/or trauma exposures measured. Data were synthesised into summary ‘areas of distress’ (see online supplementary file 5), and further refined by the research team for presentation to key stakeholders at workshop 2.

bmjopen-2018-028397supp005.pdf (243.6KB, pdf)

Strengths domains were mapped from existing resilience tools, mediating/moderating factors and ‘strategies parents use’ in the scoping review, and data generated from a discussion group with senior Aboriginal women and in key stakeholder workshop 2.

1d: Pilot discussion group with senior Aboriginal women

The purpose of this discussion group was to:

Consult with community leaders about the effects of complex trauma during the perinatal period for Aboriginal parents, and what might help or hinder the parenting transition.

Pilot qualitative methods proposed for use with parents, and gather feedback on the safety and appropriateness of these approaches and tools.

Recruitment and sample: a convenience sample of six to eight senior Aboriginal members of a community group that had expressed interest in the project.

Data collection and analysis: a facilitation plan was developed that included use of: visual tools and natural materials to facilitate discussions; cards illustrating the main themes from the scoping review to build on existing research; third person scenarios to increase safety and minimise the ‘directness’ of sensitive discussions so they were not intrusive; use of metaphors and symbolism; and a ‘strengths-based’ focus on ‘healing’ rather than ‘trauma’. The discussion group was facilitated by an Aboriginal psychologist (YC) and Aboriginal midwife (CC) with expertise in conducting discussion groups with Aboriginal people. Additional psychological support was available in line with the detailed safety plan.

A detailed discussion group protocol was developed (available on request). Data were collected in the form of visual notes and images provided by group participants, observer notes and a recording of the discussion which was transcribed verbatim. Two Aboriginal researchers (YC, CC) independently coded data into themes (thematic analysis)61 and these were discussed with participants to check the interpretation of the data accurately reflected both what was said as well as the intent. Themes were shared with key stakeholders at workshop 2 for reflection and planning of subsequent parent discussion groups.

2. Action research cycle and IM step 2: scoping assessment domains with a focus on research evidence and community knowledge, and devloping objectives

The second action research cycle includes: (2a) a second key stakeholder workshop, aligned with IM step 2, (2b) refining the assessment tool domains and preliminary questions for parents, (2 c) identifying ‘gold standard’ assessment for comparison in psychometric testing, training and cultural adaptation (if required) and (2d) first round of discussion groups with parents who have experienced complex childhood trauma.

2a: Key stakeholder workshop 2

The purpose of workshop 2 was to reflect on the activities from action research cycle 1 and plan for ethics phase II. This is aligned with IM step 2, which involves refining the project objectives and consulting with key stakeholders regarding:

The areas of distress to be included in an assessment tool.

Reflection on pilot discussions with senior Aboriginal women regarding areas of strengths and pretesting the proposed approach for working with parents.

Recruitment and sample: key stakeholders were identified as described in 1b, with approximately 60 participants attending.

Data collection and analysis: a facilitation guide was developed to address the aims of the workshop (see online supplementary file 6) and promote a culturally and emotionally safe environment. A traditional healer (Ngangkerre) worked alongside the registered psychologist to cater for different support needs and recognise the equal value of respective expertise.

bmjopen-2018-028397supp006.pdf (294.1KB, pdf)

Data regarding the 12 summary areas of distress were gathered using a modified Delphi approach. Each area of distress was allocated to a table and facilitator. Participants gathered in groups of six to eight at one table and were given individual forms (non-identified) with a description of the area of distress, with additional information provided by the facilitator. They were asked to indicate the degree of ‘importance’ (1–5) of the area of distress, and discuss and/or document any comments about why, who, where and how questions regarding this area of distress should be asked. These discussions will be central for informing co-design of safe ‘recognition’ strategies in workshop 3. Participants rotated around all 12 tables. Data were transcribed and imported into NVivo for thematic analysis and future triangulation with data to be collected at workshops 3 and 4.

Reflections regarding the discussion group with senior Aboriginal women and pretesting the discussion group ‘tree of life’62 approach for use with parents were recorded by participants pictorially using sticky notes on butchers paper. The ‘tree of life’62 was used as it provides a hopeful and inspiring approach to talking about challenging issues and generates visual images to promote shared understanding, and had been used by effectively by an Investigator in other settings (JA). This positive ‘tree of life’ tool aligned with the ‘strengths-based’ focus on parents hopes and dreams and the support parents need moving forward, rather than dwelling on past experiences. These images were photographed, data were coded into themes and imported into NVivo for thematic analysis and future triangulation with other data sources to inform co-design of awareness and support strategies.

2b: Developing assessment tool areas of distress and strength questions for parents

The purpose of refining the areas of distress and strength questions that may be included in an assessment tool is to enable initial evaluation of ‘face validity’ of the questions with parents and identify any important issues requiring direct discussion with parents.

Data collection and analysis: data collected in key stakeholder workshop 1 (1b), scoping assessment tools (1 c) and workshop 2 (2a) will be collated in NVivo for thematic analysis. These themes and issues will be refined in consultation with the research team to propose questions related to ‘areas of distress’ to be included in an assessment tool. Questions for assessing each of these areas of distress will be drafted, based on questions validated in existing tools (International Trauma Questionnaire and a version of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire adapted for Aboriginal people and cultural resources regarding mental health literacy).63 64

Strengths questions will be developed by the research team, based on strength themes identified from the scoping review, workshop activities, pilot discussion group and other strength-based tools. The core values from the conceptual framework will be applied to assess the degree to which each of the proposed questions is consistent with the values and principles of the project, and discussed in relation to key issues raised in the thematic analysis. The preliminary overinclusive question list will be discussed with the research team, and ‘pretested’ in a convenience sample of Aboriginal colleagues. The proposed questions will be incorporated into the first round of discussion groups with parents to evaluate preliminary ‘face validity’ of the proposed questions.

2c: Identifying ‘gold standard’ assessment for comparison in psychometric testing, training and cultural adaptation (if required)

The purpose of this activity is to identify the best possible ‘gold standard’ for comparison with our proposed assessment tool.

Data collection and analysis: a preliminary list of suitable tools for use as a ‘gold standard’ was generated by consensus within the research team following a systematic and transparent process of consideration. From this, the trauma section of the WHO World Mental health Composite International Diagnostic Interview has been proposed. Consultation about the proposed ‘gold standard’ will also be conducted with three or four additional key external psychiatric and psychological experts.

Up to six Aboriginal psychologists will train together in the use of the ‘gold standard’ structured clinical interview to enable them to reflect and use their cultural and clinical expertise. They will advise whether any aspects need adaptation for use with Aboriginal parents.

2d: First round of discussion groups with Aboriginal parents

The purpose of the first round of discussion groups with Aboriginal parents is to:

Understand key perinatal experiences affecting Aboriginal parents and what kinds of awareness (trauma-informed care) and support strategies might help or hinder the transition to parenting for parents experiencing complex trauma.

Evaluate the ‘face validity’ of draft questions in a preliminary assessment tool.

Recruitment and sample: approximately 24 Aboriginal parents will be invited to participate in discussion groups, one to three groups per participating jurisdiction with up to eight parents in each. The size of the group will be determined by the study coordinator in consultation with service provider staff regarding the most appropriate mix of gender, the level of comfort of participants in group discussion and language. We estimate that this will be sufficient to produce theoretical saturation of thematic categories, particularly when triangulated with data from the pilot discussion group and key stakeholder workshops. However, if saturation of themes is not reached we will consider further discussion groups as needed.

Individual parents will be recruited through the services they attend for perinatal care using direct and indirect methods. Service providers will be given written and verbal information about the study by the research team. Service providers will then ask potentially eligible parents if they give consent to be contacted by the research team to discuss the study in more detail and consider if they would like to consent to participate in the discussion group. Parents may be asked if they would like to be contacted by the research team in a private area while waiting to attend for services, after a consultation, or during other community activities. Additionally, flyers will be displayed describing the purpose of the study and providing contact details for parents to contact the research team directly.

Inclusion criteria: participants will be eligible to participate if they identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, are aged 16 years or older and they or their partner are currently pregnant or have a child <2 years of age.

Exclusion criteria: parents experiencing current serious mental illness (eg, acute psychoses or other mental health difficulties that may affect their capacity to provide informed consent and/or pose a risk to the safety of the parent and other participants in the discussion group). This will be assessed by service staff prior to asking for consent to be contacted, and by the research team prior to asking for consent to participate in the discussion group.

Data collection and analysis: a facilitation plan has been refined based on feedback from the pilot discussion group (1d) and workshop 2 (2a). The discussion group will be facilitated by an Aboriginal researcher with expertise in conducting discussion groups with Aboriginal people. Psychological support will be provided. The facilitation plan (see supplementary file 7) includes use of: visual tools and natural materials to facilitate discussions; cards illustrating the main themes from the scoping review to build on existing research; third person scenarios to increase safety and minimise the ‘directness’ of sensitive discussions so they are not intrusive; use of metaphors and symbolism to explain complex phenomena and a ‘strengths-based’ focus. Data will be collected using visual notes prepared by participants in a ‘tree of life’ activity to frame discussions about the needs for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma, and transcribed audio recordings of the discussions.

bmjopen-2018-028397supp007.pdf (416.2KB, pdf)

Two researchers will independently conduct thematic analysis and discuss draft themes with participants to check the interpretation of the data. The themes from this discussion group will be triangulated with data from previous project activities and shared with key stakeholders participating in workshop 3 to inform co-design of a preliminary awareness and support strategies.

Additional face-to-face interviews will be conducted with up to nine parents to assess the ‘face validity’ of a preliminary list of distress and strengths questions. These will be further refined in workshop 3.

3. Action research cycle and IM step 3: developing acceptable and feasible perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies

The third action research cycle includes: (3a) key stakeholder co-design workshop 3, aligned with IM step 3, (3b) psychometric evaluation of assessment tool, (3c) a second round of discussion groups with parents and (3d) discussion groups with service providers.

3a: Key stakeholder co-design workshop 3

The purpose of workshop 3, aligned with IM step 3, is to co-design the preliminary recognition and assessment process and possible awareness and support strategies.

Recruitment and sample: key stakeholders will be identified as previously described, with up to 60 participants anticipated.

Data collection and analysis: a facilitation guide will be developed to address the aims of the workshop and promote a culturally and emotionally safe environment as per previous workshop. The workshop will incorporate triangulated data from previous action research cycles to foster informed co-design of for preliminary:

Awareness and support strategies, informed by scoping review, qualitative systematic review of parents views, intervention review and relevant data from discussion groups and key stakeholder workshops. The purpose is to generate an overinclusive range of options, for further refinement in parent discussion groups to rank and assess acceptability, and service provider discussion groups to assess feasibility.

Recognition and assessment strategies, informed by data from the scoping review, scoping of assessment tools, key stakeholder workshop 2 exercise and the face validity assessments in parent discussion groups. The purpose is to develop processes to foster safe recognition of parents who may benefit from further assessment, to be further refined following parent and service provider discussion groups, and an overinclusive list of assessment tool items for psychometric evaluation and refinement.

Summary of proposed activities to be submitted for ‘phase III’ HREC approval

The detailed methods for the following activities will be refined based on feedback from ‘reflection’ and ‘planning’ from activities described in ‘ethics phase I and II’ in consultation with partner organisation staff, and submitted for ethical approval. A brief outline of main activities, aims and sample size estimates are included below.

3b: Psychometric evaluation of assessment tool

The psychometric evaluation aims to develop a valid assessment tool that enables perinatal care providers to accurately identify strengths, as well as complex trauma symptoms (measurement sensitivity) while minimising the erroneous identification of parents who are not experiencing complex trauma symptoms (measurement specificity).

The sensitivity of a complex trauma assessment will need to be high for the inventory to be effective and appropriate for use in practice, where our priority would be that all parents who could benefit from further assessment and support are recognised. Based on previous estimates of PTSD and complex trauma,64–74 we conservatively estimate that 20% of Aboriginal parents will meet subthreshold criteria of at least two symptoms. Identifiying parents meeting subthreshold criteria will maximise the sensitivity of the instrument to identify PTSD and complex trauma and we estimate that a sensitivity of 90% would be achieved. Thus, a sample size of 173 participants will be required to yield an estimate of the instrument sensitivity with a two-sided 95% CI with a width of 10% of the estimate. This sample size will also enable estimation of the specificity of the instrument to correctly identify participants who had not experienced complex trauma.

3c: Second round of discussion groups with parents, which aims to assess the acceptability of the proposed recognition and assessment process; and awareness and support strategies

Approximately 24 Aboriginal parents will be recruited to participate in discussion groups, one to three groups per participating jurisdiction with up to eight parents in each.

3d: Discussion groups with service providers, which aim to assess the feasibility of the proposed recognition and assessment process; and awareness and support strategies

Approximately 24 service providers will be recruited to participate in discussion groups, one to two groups per participating jurisdiction with up to eight service providers in each.

4. Action research cycle and IM step 4: planning for pilot, implementation and evaluation

The fourth and final action research cycle includes a fourth key stakeholder workshop and drafting plans with perinatal service providers to pilot, implement and evaluate safe acceptable and feasible perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies for Aboriginal parents experiencing complex trauma.

4a: Key stakeholder co-design workshop 4

The purpose of workshop 4, aligned with IM step 4 to ‘refine strategies and prepare to pretest’, aims to reflect on the research findings with service providers and develop plans for seeking funding to pilot, implement (IM step 5) and evaluate (IM step 6) perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

Action research poses unique challenges for seeking HREC approval. While there is an overarching structure and an outline of main activities, the detail required for ethical approval evolves during the action research process. In this project, submissions for HREC approval are being submitted to relevant jurisdictional authorities in three phases, with HREC approval for phases I and II granted at the time of submission. This is particularly important in a project involving sensitive content such as complex trauma, where the HREC need to examine draft tools and resources to consider risks for triggering distress symptoms against potential benefits.

This staged approach also enables piloting and reflection on the ‘safety’ of the research activities and flexibility to refine research processes. For example, in this project, discussions were first held with a predominantly professional group of ‘key stakeholders’ in workshop one, then with a group of senior Aboriginal women in a ‘pilot’ discussion, and then a proposed approach was ‘pretested’ in a second ‘key stakeholder’ workshop, prior to submitting the final plans for discussion groups directly with Aboriginal parents. The intent is to ensure our approach and processes maximise safety and minimise the risk of distress for parents, while also gathering the data needed to inform iterative development of awareness, recognition, assessment and support strategies. At the time of submitting this protocol, HREC approval had been granted for phase I and II (figure 2).

The funding proposal for this project was assessed by an Indigenous research panel using the NHMRC Indigenous Research Excellence criteria (see online supplementary file 1) developed to promote ethical and culturally appropriate research with Aboriginal communities. In addition, we have developed a conceptual framework (figure 1), which outlines the ethical and cultural values for this project. A specific safety framework describes how the primary value of safety will be fostered for parents, service providers, key stakeholders and team members, and the broader Aboriginal community.

Dissemination

We have developed a research dissemination plan (available on request), in line with the NHMRC Indigenous Research Excellence criteria (see online supplementary file 1) and the value of reciprocity.

The research dissemination plan includes:

Offering two-way information exchange for all community meetings (ie, prior to the meeting asking if there are any presentations about topics people would like us to offer to their staff and community members about complex trauma and parenting).

Publication of articles in open access journals with links to relevant Aboriginal health websites.

Face-to-face presentations in national and international conferences.

Translating all findings into plain language summaries.

Incorporating art, presentations and other mediums to present information.

Preparing a video/short YouTube clip with essential information for community members and making this freely available on the project website and sharing at community meetings.

Ensuring all relevant information is presented on the research website, which is regularly monitered for currency, optimised for search engine performance and follows accessibility guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CC is the study Principal Investigator and drafted this protocol based on the project proposal and other relevant project planning documents involving many people as outlined in acknowledgements and author contribution statements. GG, SJB, JA, DG, HH, KG, YC, SC, FKM, CA, SEB, HM, TH and JN are study investigators who contributed to development of the project proposal, project planning and drafting the manuscript. FKM conducted sample size estimate calculations for psychometric evaluation of the assessment tool. DD assisted with development of the conceptual framework, study planning and drafting the manuscript. NR, SH and YC are employed on the project and have contributed to development of planning documents, conceptual framework, ethics submissions which involved many considerations outlined in this protocol, and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Lowitja Institute Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1141593). CC was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (1088813). SJB was supported by an NHMRC Research Fellowship (1103976). HH was supported by an Australian NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (1080820). FKM was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1111160). JN was supported by the Roberta Holmes donation to La Trobe University. Research at MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Sara G, Lappin J. Childhood trauma: psychiatry’s greatest public health challenge? Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e300–e301. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30104-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. Research review: the neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;51:1079–95. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2014;23:185–222. 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brent DA, Silverstein M. Shedding light on the long shadow of childhood adversity. JAMA 2013;309:1777–8. 10.1001/jama.2013.4220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. . The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001349 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, et al. . National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med 2014;12:72 10.1186/1741-7015-12-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. . Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, et al. . Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2013;12:198–206. 10.1002/wps.20057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kezelman C, Stavropoulos P. Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Complex Trauma and Trauma Informed Care and Service Delivery. Sydney: Adults Surviving Child Abuse, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sotero MA. A Conceptual Model of Historical Trauma: Implications for Public Health Practice and Research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 2006;1:93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL. Catching our breath: A decolonization framework for healing Indigenous families. Intersecting Child Welfare, Substance Abuse, and Family Violence: Culturally Competent Approaches Alexandria, VA, CSWE Publications 2006:266–92. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atkinson J, Nelson J, Trauma AC. Transgenerational transfer and effects on community wellbeing In: Purdie N, Dudgeon P, Walker R, eds Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing practices and principles. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Cultural Continuity as a Protective Factor against Suicide in First Nations Youth. Horizons -A Special Issue on Aboriginal Youth, Hope or Heartbreak: Aboriginal Youth and Canada’s Future 2008;10:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alliance VP. The ecological framework Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2016. Available from http://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en/ (accessed 9/9/2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lieberman AF, Chu A, Van Horn P, et al. . Trauma in early childhood: empirical evidence and clinical implications. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:397–410. 10.1017/S0954579411000137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Font SA, Maguire-Jack K. Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: The role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl 2016;51 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCrory C, Dooley C, Layte R, et al. . The lasting legacy of childhood adversity for disease risk in later life. Health Psychol 2015;34:687–96. 10.1037/hea0000147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blackmore ER, Putnam FW, Pressman EK, et al. . The Effects of Trauma History and Prenatal Affective Symptoms on Obstetric Outcomes. J Trauma Stress 2016;29:245–52. 10.1002/jts.22095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alexander PC. Intergenerational cycles of trauma and violence: An attachment and family systems perspective. New York, NY, US: W W Norton & Co, 2015:370. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dahlberg L, Krug E. Violence-a global public health problem Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2002. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/chap1.pdf (accessed 10/10/2018).

- 21. Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. . WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012;380:1011–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sperlich M, Seng J, Rowe H, et al. . A Cycles-Breaking Framework to Disrupt Intergenerational Patterns of Maltreatment and Vulnerability During the Childbearing Year. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2017;46:378–89. 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stephenson LA, Beck K, Busuulwa P, et al. . Perinatal interventions for mothers and fathers who are survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 2018;80:9–31. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amos J, Furber G, Segal L. Understanding maltreating mothers: a synthesis of relational trauma, attachment disorganization, structural dissociation of the personality, and experiential avoidance. J Trauma Dissociation 2011;12:495–509. 10.1080/15299732.2011.593259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bridgett DJ, Burt NM, Edwards ES, et al. . Intergenerational transmission of self-regulation: A multidisciplinary review and integrative conceptual framework. Psychol Bull 2015;141:602–54. 10.1037/a0038662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Siegel JP. Breaking the links in intergenerational violence: an emotional regulation perspective. Fam Process 2013;52:163–78. 10.1111/famp.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fava NM, Simon VA, Smith E, et al. . Perceptions of general and parenting-specific posttraumatic change among postpartum mothers with histories of childhood maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2016;56:20–9. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Green-Miller SN. Intergenerational parenting experiences and implications for effective interventions of women in recovery. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 2012;73(5-A) 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Segal L, Dalziel K. Investing to Protect Our Children: Using Economics to Derive an Evidence-based Strategy. Child Abuse Review 2011;20:274–89. 10.1002/car.1192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richter LM, Daelmans B, Lombardi J, et al. . Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. The Lancet 2017;389:103–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, et al. . Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. The Lancet 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barlow J, MacMillan H, Macdonald G, et al. . Psychological interventions to prevent recurrence of emotional abuse of children by their parents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;13 10.1002/14651858.CD010725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DeGregorio LJ. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: Implications for parenting interventions from a neuropsychological perspective. Traumatology 2013;19:158–66. 10.1177/1534765612457219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowes J, Grace R. Review of early childhood parenting, education and health intervention programs for Indigenous children and families in Australia. Issues paper no 8 Australian Institute of Family Studies for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palmer VJ, Weavell W, Callander R, et al. . The Participatory Zeitgeist: an explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Med Humanit 2018:medhum-2017-011398 10.1136/medhum-2017-011398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gonzales KL, Jacob MM, Mercier A, et al. . An Indigenous framework of the cycle of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder risk and prevention across the generations: historical trauma, harm and healing. Ethn Health 2018. 1 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haebich A. Broken Circles: Fragmenting Indigenous families 1800-2000 Fremantle, Western Australia: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38. BigFoot DS, Schmidt SR. Honoring children, mending the circle: cultural adaptation of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for American Indian and Alaska Native children. J Clin Psychol 2010. 66(8 847 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, et al. . Understanding Social and Emotional Wellbeing and Mental Health from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective : Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice. Second ed Canberra: Australian Council for Education Research and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Donnell M, Taplin S, Marriott R, et al. . Infant removals: The need to address the over-representation of Aboriginal infants and community concerns of another ‘stolen generation’. Child Abuse Negl 2019;90:88–98. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sexton MB, Davis MT, Menke R, et al. . Mother–child interactions at six months postpartum are not predicted by maternal histories of abuse and neglect or maltreatment type. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2017;9:622–6. 10.1037/tra0000272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ. Does Maltreatment Beget Maltreatment? A Systematic Review of the Intergenerational Literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2012;13:135–52. 10.1177/1524838012447697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S, et al. . Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. Med J Aust 2014;200:649–52. 10.5694/mja13.00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. MacDonald C. Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research 2012;13:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ivankova NV. Applying mixed methods in community-based participatory action research: a framework for engaging stakeholders with research as a means for promoting patient-centredness. Journal of Research in Nursing 2017;22:282–94. 10.1177/1744987117699655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnstone L, Boyle M, Cromby J, et al. . The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis Leicester: British Psychological Society. 2018.

- 47. Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council. Population Based Screening Framework. Commonwealth of Australia: Barton, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rigney L. Indigenous Australian views on Knowledge Production and Indigenist Research : Runnie J, Goduka N, Indigenous Peoples' Wisdom and Power: Affirming our Knowledge. Burlington, USA: Ashgate Publishing, 2006:32–48. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dudgeon P, Milroy J, Calma T, et al. . Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Evaluation Project (ATSISPEP) report. Solutions that Work: What the Evidence and Our People Tell Us. Perth: Univerrsity of WA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rodriguez CM, Green AJ. Parenting stress and anger expression as predictors of child abuse potential. Child Abuse Negl 1997;21:367–77. 10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00177-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guarino K, Soares P, Konnath K, et al. . Trauma-Informed Organizational Toolkit. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Daniels Fund, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Denby C, Winslow C, Willette C, et al. . The Trauma Toolkit: a resource for service organizations and providers to deliver services that are trauma-informed. Winnipeg, Canada: Klinic Community Health Centre, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Atkinson C, Atkinson J, Wrigley B, et al. . Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention Legal Services: Culturally informed trauma integrated healing approach - a guide for action for trauma champions. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 54. CATSINAM, ACM. Birthing on country position statement. Canberra: College of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and midwives, Australian College of Midwives, CRANA Plus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report. Canberra: AHMAC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Heale R, Forbes D. Understanding triangulation in research. Evid Based Nurs 2013;16:98 10.1136/eb-2013-101494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bartholomew Eldrigde LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, et al. . Planning health promotion programs: An Intervention Mapping approach. 4th ed Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chamberlain C, Stansfield C, Sutcliffe K, et al. . Perinatal experiences and views of parent’s with a history of adverse childhood experiences: a protocol for a systematic review of qualitative studies. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews 2018:CRD42018102110. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ralph N, Clark Y, Gee G, et al. . Healing The Past by Nurturing the Future: Perinatal support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Parents who have experienced Complex Childhood Trauma - Workshop One Report. Bundoora, Melbourne: Judith Lumley Centre, La Trobe University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Centre D. The Tree of Life Adelaide, Australia. 2019. https://dulwichcentre.com.au/the-tree-of-life/ (accessed 23/3/2019).

- 63. NPY Womens Council Aboriginal Corporation. Uti Kulintjaku. 2018. https://www.npywc.org.au/ngangkari/uti-kulintjaku/

- 64. Atkinson C. The violence continuum: Aboriginal Australian male violence and generational post-traumatic stress. Charles Darwin University 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ben-Ezra M, Karatzias T, Hyland P, et al. . Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) as per ICD-11 proposals: A population study in Israel. Depress Anxiety 2018;35:264–74. 10.1002/da.22723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hyland P, Shevlin M, Brewin CR, et al. . Validation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017;136:313–22. 10.1111/acps.12771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Muzik M, Morelen D, Hruschak J, et al. . Psychopathology and parenting: An examination of perceived and observed parenting in mothers with depression and PTSD. J Affect Disord 2017;207:242–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Bocknek E, et al. . PTSD symptoms across pregnancy and early postpartum among women with lifetime PTSD diagnosis. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:584–91. 10.1002/da.22465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Quispel C, Schneider TAJ, Hoogendijk WJG, et al. . Successful five-item triage for the broad spectrum of mental disorders in pregnancy – a validation study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:51 10.1186/s12884-015-0480-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wenz-Gross M, Weinreb L, Upshur C. Screening for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Prenatal Care: Prevalence and Characteristics in a Low-Income Population. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:1995–2002. 10.1007/s10995-016-2073-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017;208:634–45. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gee G. Resilience and Recovery from Trauma among Aboriginal Help Seeking Clients in an Urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. University of Melbourne 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gartland D, Woolhouse H, Giallo R, et al. . Vulnerability to intimate partner violence and poor mental health in the first 4-year postpartum among mothers reporting childhood abuse: an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:1091–100. 10.1007/s00737-016-0659-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Healing the past by nurturing the future project Melbourne. Australia: La Trobe University, 2018. Available from https://www.latrobe.edu.au/jlc/research/healing-the-past/workshops/past-workshops (accessed 2/12/2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028397supp001.pdf (94.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp002.pdf (171.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp003.pdf (259.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp004.pdf (280.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp005.pdf (243.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp006.pdf (294.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028397supp007.pdf (416.2KB, pdf)