Abstract

Background

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a seasonal pattern of recurrent major depressive episodes that most commonly starts in autumn or winter and remits in spring. The prevalence of SAD depends on latitude and ranges from 1.5% to 9%. The predictable seasonal aspect of SAD provides a promising opportunity for prevention in people who have a history of SAD. This is one of four reviews on the efficacy and safety of interventions to prevent SAD; we focus on agomelatine and melatonin as preventive interventions.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of agomelatine and melatonin (in comparison with each other, placebo, second‐generation antidepressants, light therapy, psychological therapy or lifestyle interventions) in preventing SAD and improving person‐centred outcomes among adults with a history of SAD.

Search methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1950‐ ), Embase (1974‐ ), PsycINFO (1967‐ ) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to 19 June 2018. An earlier search of these databases was conducted via the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trial Register (CCMD‐CTR) (all years to 11 August 2015). Furthermore, we searched the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database and international trial registers (to 19 June 2018). We also conducted a grey literature search and handsearched the reference lists of included studies and pertinent review articles.

Selection criteria

To examine efficacy, we included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on adults with a history of winter‐type SAD who were free of symptoms at the beginning of the study. For adverse events, we intended also to include non‐randomised studies. We planned to include studies that compared agomelatine versus melatonin, or agomelatine or melatonin versus placebo, any second‐generation antidepressant, light therapy, psychological therapies or lifestyle changes. We also intended to compare melatonin or agomelatine in combination with any of the comparator interventions mentioned above versus the same comparator intervention as monotherapy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors screened abstracts and full‐text publications, abstracted data and assessed risk of bias of included studies independently. We intended to pool data in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model, but included only one study.

Main results

We identified 3745 citations through electronic searches and reviews of reference lists after deduplication of search results. We excluded 3619 records during title and abstract review and assessed 126 full‐text papers for inclusion in the review. Only one study, providing data of 225 participants, met our eligibility criteria and compared agomelatine (25 mg/day) with placebo. We rated it as having high risk of attrition bias because nearly half of the participants left the study before completion. We rated the certainty of the evidence as very low for all outcomes, because of high risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

The main analysis based on data of 199 participants rendered an indeterminate result with wide confidence intervals (CIs) that may encompass both a relevant reduction as well as a relevant increase of SAD incidence by agomelatine (risk ratio (RR) 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.34; 199 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Also the severity of SAD may be similar in both groups at the end of the study with a mean SIGH‐SAD (Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders) score of 8.3 (standard deviation (SD) 9.4) in the agomelatine group and 10.1 (SD 10.6) in the placebo group (mean difference (MD) ‐1.80, 95% CI ‐4.58 to 0.98; 199 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events may be similar in both groups. In the agomelatine group, 64 out of 112 participants experienced at least one adverse event, while 61 out of 113 did in the placebo group (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.34; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Three out of 112 patients experienced serious adverse events in the agomelatine group, compared to 4 out of 113 in the placebo group (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.30; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

No data on quality of life or interpersonal functioning were reported. We did not identify any studies on melatonin.

Authors' conclusions

Given the uncertain evidence on agomelatine and the absence of studies on melatonin, no conclusion about efficacy and safety of agomelatine and melatonin for prevention of SAD can currently be drawn. The decision for or against initiating preventive treatment of SAD and the treatment selected should consider patient preferences and reflect on the evidence base of all available treatment options.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Acetamides, Acetamides/therapeutic use, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Melatonin, Melatonin/agonists, Melatonin/therapeutic use, Placebos, Placebos/therapeutic use, Seasonal Affective Disorder, Seasonal Affective Disorder/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Melatonin and agomelatine for prevention of winter depression

Why is this review important?

Many people in northern latitudes suffer from seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which occurs as a reaction to reduced sunlight. Three‐quarters of those affected are women. Lethargy, overeating, craving for carbohydrates and depressed mood are common symptoms. In some people, SAD becomes depression that seriously affects their daily lives. Up to two‐thirds experience depressive symptoms every winter.

Who might be interested in this review?

General practitioners, psychiatrists, pharmacists, other health professionals working in adult mental health services, and researchers could be interested in the results of this review. Anyone who has experienced winter depression, or who has friends or relatives who have experienced winter depression might also be interested.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

Because of the seasonal pattern and high recurrence of SAD, melatonin or agomelatine could be used to prevent the onset of depressed mood. The goal of this report is to examine whether benefits outweigh harms of melatonin or agomelatine when used to prevent onset of a new depressive episode in people with a history of SAD who were free of symptoms when the preventive intervention started. To date, this question has not been examined in a systematic way. This is one of four reviews on the efficacy and potential harms of interventions to prevent SAD.

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched databases up to June 2018 for studies on melatonin or agomelatine for prevention of winter depression. Among 3745 records, we found one randomised controlled study comparing agomelatine with placebo for one year. All 225 participants had a history of winter depression but were not depressed when the prevention study started.

What does evidence from the review reveal?

The included study showed neither a clear effect in favour nor against agomelatine as a preventive treatment. In addition, the certainty of evidence for all outcomes was very low, making it impossible to draw any conclusions about the efficacy and safety of agomelatine for the prevention of winter depression. No evidence on melatonin for prevention of SAD was identified.

Doctors need to discuss with persons with a history of SAD that currently evidence on agomelatine or melatonin for preventive treatment options for SAD is inconclusive, therefore treatment selection should be strongly based on peoples' preferences and reflect on the evidence base of all available treatment options.

What should happen next?

Review authors recommend that future studies should evaluate the efficacy of agomelatine or melatonin in preventing SAD and should directly compare these interventions against other treatment options, such as light therapy, antidepressants, or psychological therapies to determine the best treatment option for prevention of SAD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Agomelatine compared to placebo for preventing seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

| Agomelatine compared to placebo for preventing seasonal affective disorder (SAD) | ||||||

| Population: adults with a history of SAD Setting: inpatient and outpatient clinics in Europe and North America Intervention: agomelatine (25 mg a day) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with agomelatine | |||||

| Incidence of SAD (modified ITT) assessed with: SIGH‐SAD 16 or higher within a year | Low | RR 0.83 (0.51 to 1.34) | 199 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa, b, c | Modified ITT analysis | |

| 300 per 1000 | 249 per 1000 (153 to 402) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 415 per 1000 (255 to 670) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 600 per 1000 | 498 per 1000 (306 to 804) | |||||

| Number of persons with at least one adverse event within a year | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa, b, c | ||

| 540 per 1000 | 572 per 1000 (453 to 723) | |||||

| Severity of depression (SIGH‐SAD score) at the end of the study | The mean severity of depression (SIGH‐SAD score at end of study) was 10.1 | MD 1.80 lower (4.58 lower to 0.98 higher) | ‐ | 199 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa, b, c | Modified ITT analysis |

| Quality of life | No evidence identified | |||||

| Quality of interpersonal and social functioning | No evidence identified | |||||

| Number of persons with at least one severe adverse event within a year | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.17 to 3.30) | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa, b, c | ||

| 35 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (6 to 117) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SIGH‐SAD: Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aWe downgraded one step for "high risk of bias" due to the high attrition rate (45% in agomelatine group and 52% in placebo group). bWe downgraded one step for "indirectness" because participants in this prevention study were enrolled in a study where they received open‐label treatment with agomelatine. Only those reaching stable remission were eligible for the prevention study. This may not represent a real‐world scenario of SAD prevention. cWe downgraded one step for "imprecision" because optimal information size was not reached, and the confidence interval was broad including both a potential beneficial and harmful effect.

Background

Description of the condition

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a seasonal pattern of recurrent major depressive episodes that most commonly occurs during autumn or winter and remits in spring or summer (Rosenthal 1984). In addition to the predictable seasonal pattern of depression, persons suffering from SAD commonly experience atypical symptoms such as hypersomnia, carbohydrate craving with increased appetite and weight gain and extreme fatigue (Sohn 2005). Prevalence in the USA ranges from 1.5% in southern Florida to 9% in northern regions (Rosen 1990). In northern latitudes, the prevalence of SAD is estimated to be around 10% (Byrne 2008). SAD is a multifactorial condition in which chronobiological mechanisms related to circadian rhythms, melatonin, serotonin turnover and photoperiodism (length of dark hours relative to light hours over a 24‐hour period) are thought to play a role (Ciarleglio 2011; Levitan 2007). A quintessential and especially impairing quality of this illness is its high risks of recurrence and persistence. Approximately two‐thirds of those diagnosed with SAD will face recurrence of these distressing symptoms the following winter (Rodin 1997). In the five to 11 years following initial diagnosis, 22% to 42% of people still suffer from SAD, and 33% to 44% develop a non‐seasonal pattern in subsequent episodes; the disorder resolves completely in only 14% to 18% of people (Magnusson 2005; Schwartz 1996). Indeed, many people who suffer from SAD experience this type of depression every year, which makes it particularly amenable to preventive treatment (Westrin 2007).

Description of the intervention

Research into the origin of SAD has focused on the role of circadian rhythms and melatonin (Lam 2006). Lewy et al suggested that relative phase shifting of circadian rhythms in relation to the timing of sleep‐wake rhythm is responsible for the genesis of SAD (Lewy 1988). As a rhythm‐regulating factor, and as a hormone involved in the regulation of sleep, melatonin is essential for control of mood and behaviour (Srinivasan 2012). Appropriately timed administration of melatonin has chronobiotic properties and can assist with phase shifting of the circadian system (alone or, more typically, in combination with light exposure) (Hickie 2011). The antidepressant agomelatine, which is a metabolic stable analogon of melatonin, is a melatonergic (MT1 and MT2) receptor agonist and a serotonin‐2c receptor antagonist. Previous studies have shown that agomelatine can restore disrupted circadian rhythms, which are implicated in the pathophysiology of SAD (Kasper 2010; Pjrek 2007). It was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009 for the treatment of major depressive disorders (Srinivasan 2012). Other treatments used in the prevention of SAD include light therapy, second‐generation antidepressants and psychological therapies. Light therapy has been shown to be an effective non‐pharmacological treatment for SAD and is often used as first‐line therapy for this disorder (Terman 2005a). Decreased seasonal exposure to light is thought to be a reason for the development of SAD, which occurs through phase shifts in circadian rhythms, resulting in alterations of serotonin metabolism. As a consequence, light therapy has been studied intensively as treatment for SAD (Partonen 1998). One second‐generation antidepressant (drugs typically used to treat major depressive disorder) ‐ bupropion XL extended‐release ‐ is currently licensed for use in preventing SAD (Modell 2005). At the neurochemical level, changes in both serotonergic and catecholaminergic transmitter systems seem to play a key role in SAD (Neumeister 2001). Targeting these systems with serotonin or noradrenaline reuptake inhibition, or both, provides biological plausibility for the mechanism of action of second‐generation antidepressants. The rationale for using second‐generation antidepressants for prevention of SAD is based on the efficacy of second‐generation antidepressants in the treatment of SAD (Thaler 2010). Finally, several psychological interventions have been evaluated for their effectiveness in treating SAD. Among these are behavioural therapy/behaviour modification, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), third‐wave CBT and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychological therapy, regardless of the specific modality, may prevent SAD by helping individuals intentionally engage in cognitive or behavioural activities (or both) that directly counter those cognitive patterns or behavioural responses that might be inherent sequelae of the worsening mood symptoms commonly associated with SAD.

How the intervention might work

Given that nearly all successful treatments for mood disorders affect circadian rhythms, drugs that cause shifts, resetting and stabilisation of rhythms are considered effective for treatment of mood disorders (Srinivasan 2012). On the neurochemical level, melatonergic systems seem to play a substantial role in SAD. Targeting these systems with melatonin or agomelatine provides biological plausibility for their mechanism of action. Melatonin has a sleep‐enhancing and antidepressant effect above its agonistic behaviour at melatonergic (MT1 and MT2) binding sites. Even at low physiological doses, it can cause advances (shifts to an earlier time) or delays (shifts to a later time), depending on when on its phase‐response curve it is administered (Lewy 2006). Although melatonin might improve sleep‐wake timing and might increase sleep duration in people with major depressive disorder, more specific antidepressant effects are few (Hickie 2011). Agomelatine represents the only available MT1/MT2 melatonergic receptor agonist and 5‐HT2c antagonist that has been shown to induce resynchronisation of circadian rhythms and antidepressant actions in humans. By avoiding 5‐HT2a stimulation, agomelatine shows a more favourable side effect profile than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in terms of sexual functioning and gastrointestinal disturbances. However, use of agomelatine has been discontinued in the USA because cases of hepatotoxicity have been reported (Srinivasan 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

The predictable seasonal aspect of SAD provides a specific and promising opportunity for prevention. However, people affected by SAD and clinicians face much uncertainty in their collaborative decisions about the choice of a preventive intervention (Westrin 2007). To date, no review has determined the efficacy, effectiveness and risk of harms of melatonin and agomelatine for preventing recurrent SAD.

Our findings intend to provide insights into (1) available evidence on the benefits and harms of competing interventions for prevention of SAD with respect to person‐centred outcomes, and (2) gaps in the evidence base that will inform future research needs.

This is one of four reviews of interventions to prevent SAD. The others focus on light therapy (Nussbaumer‐Streit 2019), second‐generation antidepressants (Gartlehner 2019), and psychological therapies (Forneris 2019), as preventive interventions.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of agomelatine and melatonin (in comparison with each other, placebo, second‐generation antidepressants, light therapy, psychological therapy or lifestyle interventions) in preventing SAD and improving person‐centred outcomes among adults with a history of SAD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Efficacy (beneficial effects)

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of melatonin and agomelatine for prevention of seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

Adverse effects

We included RCTs (including cross‐over studies and cluster‐randomised trials) of melatonin and agomelatine for SAD.

We planned to also include controlled non‐randomised studies of melatonin and agomelatine for SAD.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Male and female adults (≥ 18 years of age) of all races, ethnicities and cultural groups with a history of SAD who do not fulfil the criteria for a current major depressive episode when the intervention (agomelatine or melatonin) was initiated.

Diagnosis

We defined SAD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5) as a seasonal pattern of recurrent major depressive episodes (APA 2013). However, we restricted the definition to winter‐type SAD (i.e. major depression in autumn/winter with full remission in spring/summer), and we did not include people with bipolar disorder and a seasonal pattern. We intended to include studies that had used definitions from prior versions of the DSM (APA 1980; APA 1987; APA 2000).

Comorbidities

We excluded studies that enrolled participants with depressive disorder due to another medical condition. We included populations at risk of SAD with common comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease) that were not the cause of the depressive episode.

Setting

We included studies in all settings (e.g. inpatient or outpatient clinics, community‐based clinics, etc).

Subset data

We included studies that provided data on subsets of participants of interest, as long as the subset met our eligibility criteria. We did not include studies with 'mixed' populations if researchers did not adequately stratify data with respect to our population of interest.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they assessed melatonin and agomelatine and combination therapies of melatonin/agomelatine with any of the comparator interventions listed below.

Comparator interventions

We planned to compare melatonin/agomelatine with:

melatonin/agomelatine;

placebo;

second‐generation antidepressants;

light therapy;

psychological therapy; and

lifestyle interventions (e.g. exercising, making the environment sunnier (opening blinds), spending regular time outside, adapting nutrition (low‐fat diet, reduction in refined sugars)).

We also planned to compare melatonin/agomelatine in combination with any one of the comparator interventions listed above versus the same comparator intervention as monotherapy (see Data extraction and management).

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the above inclusion criteria regardless of whether investigators reported on the following outcomes. In consultation with clinical experts, we selected the following outcomes a priori.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome for benefit was the incidence of SAD. We defined incidence of SAD as the proportion of participants with a SIGH‐SAD (Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders) score of 20 or higher (Williams 2002), or as defined by authors.

The primary outcome for harm was the overall rate of adverse events related to preventive interventions.

Secondary outcomes

Severity of the SAD episode or SAD‐related symptoms, as measured by a validated tool (e.g. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; Hamilton 1960).

Quality of life, as measured by a validated quality of life tool (e.g. Short Form (SF)‐36; Ware 1992).

Quality of interpersonal and social functioning, as measured by a validated tool (e.g. the Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE–RIFT; Leon 1999).

Proportion of participants with serious adverse events.

Rates of discontinuation of preventive intervention due to adverse events.

Overall rate of discontinuation.

Timing of outcome assessment

Depending on available data, we planned to synthesise outcomes at different time points: short‐term (0 to 3 months); medium‐term (> 3 months and up to 6 months); and long‐term (> 6 months and up to 12 months) throughout an entire six‐month period of risk during an autumn‐winter season.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

Our main focus was on person‐centred outcomes, that is, outcomes that people notice and care about. If several measures could be used to assess the same outcome, we consulted with clinical experts regarding the validity and reliability of individual outcome measures and prioritised accordingly.

Search methods for identification of studies

This is one of four Cochrane Reviews on prevention of SAD. We performed the same search for all reviews (Forneris 2019; Gartlehner 2019; Nussbaumer‐Streit 2019).

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) maintains two clinical trials registers at its editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references‐based register and a studies‐based register. The CCMD Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)‐References contains more than 39,000 reports of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on common mental disorders. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the Specialised CCMDCTR‐Studies Register, and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual and use of a controlled vocabulary (the CCMD Information Specialist can provide further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group Registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐), and PsycINFO (1967‐); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also obtained from international trials registers through trials portals of the World Health Organization (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)) and pharmaceutical companies and by handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1. This register is current to June 2016 only.

Electronic searches

The searches for this review are up‐to‐date as of 19 June 2018. Details of all searches conducted between April 2013 and June 2018 are described below.

The Information Specialist with the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) ran an initial search of their Group's specialised registers (CCMD‐CTR‐Studies and CCMD‐CTR‐References) (all years to 12 April 2013) using terms for condition only. An updated search was performed on 11 August 2015, prior to the first publication of this review.

("seasonal affective disorder*" or "seasonal depression" or "seasonal mood disorder*" or "winter depression" or SIGH‐SAD*).

In addition, we conducted our own searches of the following electronic databases (to 26 May 2014) to ensure that no studies had been missed by the CCMD‐CTR specialised registers (Appendix 2).

International Pharmaceutical Abstracts

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

Web of Science (formerly Web of Knowledge: includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, BIOSIS, Derwent Innovations Index, Data Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index) (all available years)

The Cochrane Library

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED)

We also searched international trial registries via the World Health Organization trials portal (ICTRP), and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished or ongoing studies.

We did not restrict searches by date, language or publication status.

In June 2018, CCMD's Information Specialist updated the search for studies on all of the databases listed above (Appendix 3), with the exception of International Pharmaceutical Abstracts. The search of these databases was necessary as the CCMD‐CTR was out‐of‐date at the time (current to June 2016 only).

Searching other resources

Grey literature

To detect additional studies, we checked the following sources.

IFPMA (International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations) Clinical Trials Portal

OpenGrey

National Institute of Health RePORTER

Health Services Research Projects in Progress (HSRProj)

Hayes Inc. Health Technology Assessment

The New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Index

Conference Papers Index

European Medicines Agency

Drugs@FDA (Food and Drug Administration)

National Registry of Evidence‐Based Programs and Practices (NREPP) (no longer available online)

Reference lists

We handsearched the references of all included studies and pertinent review articles.

Correspondence

We contacted trialists and subject matter experts to ask for information on unpublished and ongoing studies, or to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors (BN, AG, CF, LM, BG, JW, LL, GG) dually and independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the searches. We retrieved full‐text copies of all studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria based on this initial assessment, and two review authors (BN, AG, CF, LM, BG, JW, LL) screened them independently to determine their eligibility.

If the two review authors did not reach consensus, they discussed disagreements with a third party (GG), who resolved them. We tracked all results in an EndNote X8 database (EndNote X8 2016).

We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009), and the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form to extract study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors (AG, BN) independently extracted study characteristics and outcome data. We resolved discrepancies by reaching consensus. We reported whether studies were detected by searches of databases of published studies, by handsearches or by grey literature searches.

We extracted the following study characteristics.

Methods: study design, duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, duration of treatment period, number of study centres and locations, study setting, withdrawals and dates of study

Participants: number of participants, mean age, age range, proportion of women, number of prior depressive episodes, diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant interventions and excluded interventions

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected and time points reported

Notes: funding for studies and notable conflicts of interest of study authors

We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were not reported in a useable way. We resolved disagreements by reaching consensus. One review author (BN) transferred data into the Review Manager file (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing data presented in the systematic review versus data provided in the study reports. A second review author (AG) would spot‐check study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Main planned comparisons

Melatonin versus placebo

Agomelatine versus placebo

Melatonin versus agomelatine

Melatonin versus second‐generation antidepressants

Agomelatine versus second‐generation antidepressants

Melatonin versus light therapy

Agomelatine versus light therapy

Melatonin versus psychological therapy

Agomelatine versus psychological therapy

Melatonin versus lifestyle intervention

Agomelatine versus lifestyle intervention

Agomelatine/melatonin + comparator intervention (as listed in Types of interventions) versus placebo

Agomelatine/melatonin + comparator intervention (as listed in Types of interventions) versus the same comparator intervention as monotherapy (e.g. agomelatine + light therapy versus light therapy alone)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AG, BN) independently assessed the risk of bias of included randomised trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This tool allows assessment of random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other potential threats to validity. Specifically, we assessed attrition in these trials and reasons for attrition, particularly when attrition rates between two groups in a trial differ substantially. In addition, we assessed whether all relevant outcomes for the trial were reported in the published articles. We assessed each domain as having high risk of bias, low risk of bias or unclear risk of bias.

For non‐randomised studies, we planned to use the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale, which involves selection of cases or cohorts and controls, adjustment for confounders, methods of outcome assessment, length of follow‐up, and statistical analysis (Wells 2009).

Measures of treatment effect

We used data extracted from the original study to construct 2 × 2 tables for dichotomous outcomes. When multiple studies allowed for quantitative analysis, we planned to calculate the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each outcome. We chose RR as an effect measure because for decision makers, RRs are easier to interpret than odds ratios (ORs), particularly when event rates are high.

We planned to pool continuous data using the mean difference (MD) when an outcome was measured on the same scale, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) when an outcome was measured on different scales. When available, we planned to use final measurements rather than changes from baseline to estimate differences between treatments. When it was considered necessary to use both change and postintervention scores in a comparison, we planned to present these by subgroup using the MD rather than the SMD.

When time‐to‐event data were available, we intended to calculate a pooled hazard ratio (HR), or to dichotomise data at multiple time points into response/no response (e.g. at 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, etc).

The same time points as specified under 'Timing of outcome assessment' were intended to form the basis for dichotomisation into response/no response.

For non‐randomised studies, we planned to use adjusted treatment effects when available.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

To incorporate cluster‐randomised trials, we planned to reduce the size of each trial to its 'effective sample size'. If intracluster correlation coefficients were not reported, we intended to try to find external estimates from similar studies. We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of including such trials.

Cross‐over trials

To avoid carry‐over effects, we planned to include data only from the first period of cross‐over studies.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For included trials that had multiple treatment groups (e.g. differing doses of one drug versus placebo), we planned to include data for the treatment arms and to halve data from the placebo arm, or to collapse data for different doses into one group when this was clinically appropriate (Hansen 2009).

Dealing with missing data

We used intention‐to‐treat analysis when data were missing for participants who dropped out of trials before completion. When data regarding an outcome of interest were not reported, we planned to contact the authors of publications to obtain missing results. However, for the included study we were able to obtain comprehensive trial data from the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use the Cochran Chi2 test (Q‐test) to assess heterogeneity; a P value less than 0.10 is considered statistically significant. We planned to use the I2 statistic to estimate the degree of heterogeneity. This measure describes the percentage of total variation across studies that results from heterogeneity rather than from chance. We planned to interpret the importance of heterogeneity in terms of its magnitude and the direction of effects. We planned to not consider thresholds; instead, we planned to adopt the overlapping bands, as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. For example, we consider an I2 value between 0% and 40% as probably not important, between 30% and 60% as representing moderate heterogeneity, between 50% and 90% as representing substantial heterogeneity and between 75% and 100% as representing considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

If we found more than 10 studies, we planned to perform a funnel plot analysis. A funnel plot is a graph used to detect publication bias. We planned to look at whether the largest studies were near the average and small studies spread on both sides of the average. Variations from this assumption can indicate the existence of publication bias, but asymmetry may not necessarily be caused by publication bias. In addition, we planned to use Kendell's tau (Begg 1994), Egger's regression intercept (Egger 1997), and Fail‐Safe N (Rosenthal 1979), to assess reporting biases.

Data synthesis

We analysed data using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We planned to pool data for meta‐analysis when participant groups were similar; when studies assessed the same treatments versus the same comparator; and when investigators used similar definitions of outcome measures over a similar duration of treatment. In general, we intended to use random‐effects models to combine results because we did not expect the true effect to be the same for all included studies. We planned to employ fixed‐effect models to determine differences in treatment effects between random‐effects and fixed‐effect results. We intended to weigh studies using the Mantel‐Haenszel method. We rated the certainty of the evidence using the system developed by the GRADE Working Group Guyatt 2011. We planned to perform qualitative analyses of data on adverse effects by comparing crude rates, and to conduct quantitative analyses of the rate of adverse effects only if we located a sufficient number of prospective observational studies or randomised trials that provide data on adverse effects that are suitable for pooling.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Sex, age, history of non‐seasonal major depressive episodes and psychiatric comorbidities are potential effect measure modifiers for prevention of SAD. When data were sufficient, we planned to conduct subgroup analyses for primary outcome measures. Subgroup analyses should be performed and interpreted with caution because multiple analyses could lead to false‐positive conclusions. We intended to conduct subgroup analyses based on:

men versus women;

history of non‐seasonal major depressive episodes versus no history of non‐seasonal major depressive episodes;

age younger than 65 years versus 65 years and older; and

Axis I, Axis II comorbidities versus no Axis I, Axis II comorbidities.

Sensitivity analysis

The purpose of sensitivity analyses is to test the robustness of decisions made during the review process.

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses:

excluding small studies (i.e. studies with fewer than 30 participants);

excluding studies with high risk of bias (i.e. studies that have been rated as having high risk of bias in one or more domains);

excluding studies published only in abstract form;

with adjusted versus unadjusted results; and

excluding cluster‐randomised trials.

'Summary of findings' tables

We assessed the certainty of evidence by using the GRADE approach and presented the results for our main comparisons and outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables (as listed in Types of outcome measures). Two review authors graded the certainty of evidence (BN, GG). We did not expect to be able to stratify populations into low‐, medium‐ and high‐risk groups. For 'assumed risk', we planned to use prevalence studies from countries in northern latitudes (e.g. Scandinavia, Canada, northern USA) in which SAD leads to substantial burden of disease.

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to rate the certainty of evidence and to prepare the 'Summary of findings' tables (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

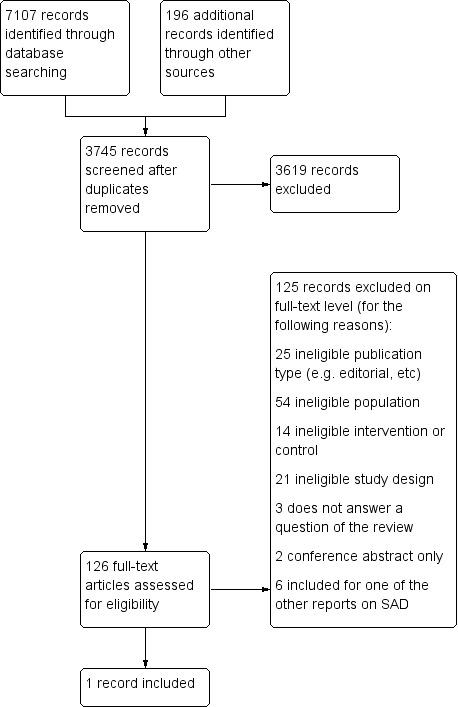

We identified 3745 citations through electronic searches and reviews of reference lists after deduplication of search results. We excluded 3619 records during title and abstract review, and we included 126 articles for full‐text review and assessment for eligibility. We included one study in this review. The PRISMA flow chart documents the selection of the literature in this review (Figure 1). In the section Excluded studies we describe the reasons for exclusion in more detail.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We found the included study through a search in the database of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). They provided us the complete trial data for this study that has not been published in a scientific journal.

Included studies

We included one randomised controlled trial (RCT) assessing the effectiveness of agomelatine compared to placebo in preventing seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (Kasper 2008). The study was sponsored by the Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier (France) and Servier Canada Inc. (Canada). In the following section we describe the study in more detail (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Design

The included RCT was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group, multicentre study. It assessed the efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25 mg) compared to placebo for one year following an open‐label treatment period of 18 weeks. Before the actual prevention study started, participants were included into a treatment study because of acute depressive SAD episodes. All persons were openly treated with agomelatine (25 mg, daily) during the winter for at least 18 weeks. Only participants who reached full and stable remission for at least two months were included into the actual prevention trial. Remission was defined as a score of 7 or less on the 21‐item Hamilton Depression Scale and 7 or less points on the 8‐item Scale for Atypical Symptoms. These participants were randomised to agomelatine (25 mg, daily) or placebo in May and continued treatment for one year. For this report we focus on results of the prevention part of the study.

Sample size

After treating 355 participants with open‐label agomelatine during winter, 225 participants reached stable remission for at least two months and were randomised: 112 participants were allocated to the agomelatine group, and 113 participants to the placebo group. In the agomelatine group one person (1%) was lost to follow‐up and 49 (44%) were withdrawn (30 due to lack of efficacy, 13 due to non‐medical reasons, 3 due to adverse events, 3 due to protocol deviation). In the placebo group 59 (52%) were withdrawn (35 people due to lack of efficacy, 16 due to non‐medical reasons, 5 due to adverse events, 2 due to protocol deviation, 1 due to recovery).

Setting

This multicentre trial was conducted in 25 centres located in eight countries: Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, and Sweden.

Participants

Participants were adults with a history of SAD who had an acute depressive episode that had been openly treated with agomelatine in the winter preceding the prevention study. Only persons who had been in stable remission for at least two months were eligible for randomisation. People in the agomelatine group were, on average, 41.1 years (standard deviation (SD) ± 11.2) old; those in the placebo group 40.4 years (SD ± 10.9). The majority of the participants were female: 75% in the agomelatine group and 70% in the placebo group. All participants had a recurrent major depressive disorder with seasonal pattern according to the DSM‐IV‐TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ‐ text revision at time of selection) (Segal 2010). Participants in both groups had similarly often experienced depressive episodes in the past, with a mean number of 9.9 depressive episodes (SD ±7.3) in the agomelatine group and 9.7 (SD ± 6.7) in the placebo group. Severity of the last depressive episode in the preceding winter was comparable in both groups. In the agomelatine group 71% had a moderate depression and 29% a severe depression without psychotic features, in the placebo group 74% had a moderate and 26% a severe depression without psychotic features.

Interventions

The active treatment was agomelatine. Participants administered one tablet containing 25 mg agomelatine orally per day, in the evening. In the control group participants took one placebo tablet orally per day, in the evening. Placebo was identical in taste and appearance.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome in this study was the incidence of depression, measured with the SIGH‐SAD. People with a SIGH‐SAD total score ≥ 16 were considered depressed. This deviates from our a priori defined cut‐off of a SIGH‐SAD total score ≥ 20, see Types of outcome measures, potentially leading to an overestimation of depression incidence. In addition, severity of depression was assessed with the SIGH‐SAD.

Safety outcomes, including number of people experiencing at least one adverse event, number of people with at least one serious adverse event, and number of participants discontinuing the study due to adverse events, were measured. Additionally, the overall rate of discontinuation was reported.

Quality of life, as well as quality of interpersonal and social functioning, were not assessed by the researchers.

Excluded studies

Overall, we assessed 126 references as full‐text articles and excluded 125 of them. The Characteristics of excluded studies section shows all records that narrowly missed the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. We excluded studies because included participants did not suffer from SAD (but rather from major depressive disorder or subsyndromal SAD), or because they already had depressive symptoms when the study started. We mentioned studies that were included in the review on light therapy (Nussbaumer‐Streit 2019), second‐generation antidepressant (Gartlehner 2019), and psychological therapy (Forneris 2019), under Characteristics of excluded studies and we explained why they are not included in this review.

Ongoing studies

We identified no ongoing studies of interest.

Studies awaiting classification

We found no studies currently awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

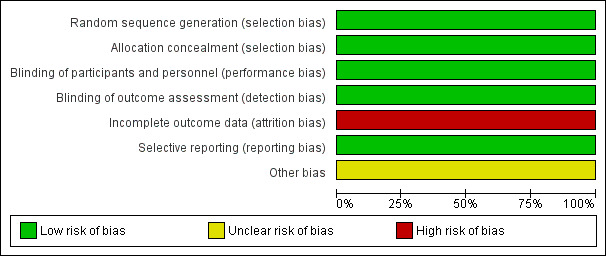

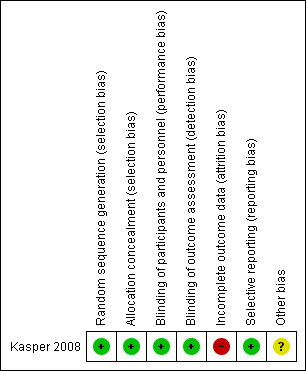

For details of the risk of bias assessment, see Characteristics of included studies. A graphical representation of the overall risk of bias in the included study can be found in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across the included study.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for the included study.

Allocation

The randomisation list was generated centrally by the Biometry Department of one sponsor using permutation blocks of fixed size of four. Blocks were sent to each participating centre and treatments were allocated to the participants in ascending order as they were included in the randomised period. Allocation concealment was warranted by using sealed, coded envelopes that were kept by the investigator and/or the pharmacist. Only the two sponsors had a list containing the treatment codes. After randomisation both groups were comparable in characteristics such as age, sex, and disease severity and duration. Therefore, we rated the risk for selection bias as low.

Blinding

Participants and study personnel were blinded to treatment. To keep the blinding, the placebo and agomelatine tablets were identical in taste and appearance. We rated the risk for performance and detection bias as low.

Incomplete outcome data

The attrition rate was high, with 45% of participants in the agomelatine group and 52% in the placebo group leaving the study before completion. Only the safety analysis used a true intention‐to‐treat (ITT) approach. The efficacy analyses employed a modified ITT approach, not considering all participants randomised to the study. We rated the risk for attrition bias as high. The last observation of each participant was used for analysis.

Selective reporting

The study was not published in a scientific journal. However, we received the comprehensive trial report from the EMA that reported on all measured outcomes. Therefore, we rated the risk of reporting bias as low.

Other potential sources of bias

The randomised part of the study was preceded by an open‐label study where all received agomelatine. Only those reaching remission after treatment with agomelatine were included in the prevention trial. This does not represent a conventional prevention setting, therefore we rated other potential sources of bias as unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: melatonin versus placebo

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 2: agomelatine versus placebo

Primary outcomes

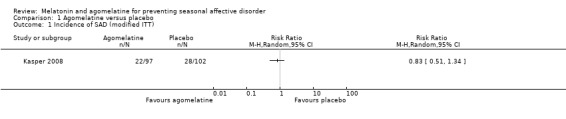

2.1 Incidence of SAD

The main analysis used a modified ITT approach. Participants who took at least one dose of the randomised treatment and had at least one visit during the fall‐winter period were part of this analysis set (199 of 225 randomised participants; 88%).

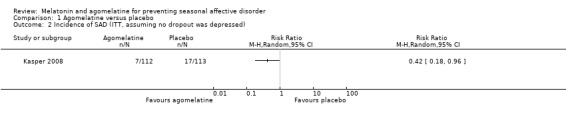

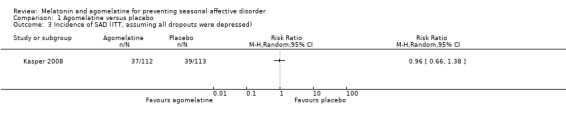

This modified ITT analysis rendered an inconclusive result, because the 95% confidence interval (CI) encompassed both relevant beneficial and relevant harmful effects of agomelatine (risk ratio (RR) 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.34; 199 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). In order to assess the impact of the 26 participants not included in this analysis we calculated a best‐case and a worst‐case scenario. In the best‐case scenario we assumed that all participants who were not part of the ITT analysis were actually free of depression. Under this assumption people in the agomelatine group had a reduction of SAD incidence compared to the placebo group (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.96; 225 participants; Analysis 1.2). Under the assumption of a worst‐case scenario (all 26 participants had developed depression) similar proportions of SAD incidence were shown in the agomelatine and the placebo group (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.38; 225 participants; Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Incidence of SAD (modified ITT).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Incidence of SAD (ITT, assuming no dropout was depressed).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Incidence of SAD (ITT, assuming all dropouts were depressed).

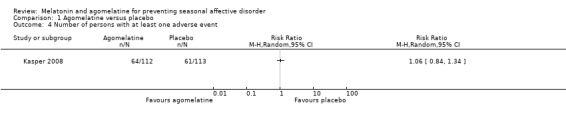

2.2 Overall rate of adverse events

Overall, 125 participants experienced 351 adverse events. In the agomelatine group 64 out of 112 people (57%) reported 187 adverse events. In the placebo group 61 people of 113 (54%) experienced 164 adverse events, the CI was broad (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.34; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Number of persons with at least one adverse event.

Most commonly, headache (13% of agomelatine participants, 12% of placebo participants), nasopharyngitis (9% of agomelatine participants, 6% of placebo participants), and back pain (5% of agomelatine participants, 2% of placebo participants) were reported as adverse events.

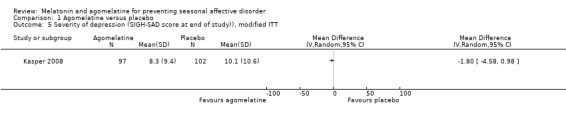

Secondary outcomes

2.3 Severity of SAD or SAD‐related symptoms

The severity of SAD‐related symptoms was measured with the SIGH‐SAD score at the end of the study. The mean SIGH‐SAD score in the agomelatine group was 8.3 (SD 9.4), and 10.1 (SD 10.6) in the placebo group, the CI included a potential lower as well as higher SIGH‐SAD score in the agomelatine group (mean difference (MD) ‐1.80, 95% CI ‐4.58 to 0.98; 199 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Severity of depression (SIGH‐SAD score at end of study)), modified ITT.

2.4 Quality of life

The included RCT did not measure this outcome.

2.5 Quality of interpersonal and social functioning

The included RCT did not measure this outcome.

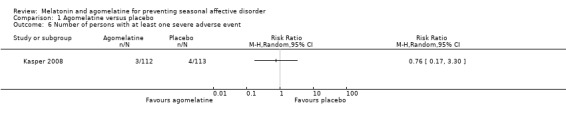

2.6 Proportion of participants with serious adverse events

No participant died during the study, but seven participants experienced a serious adverse event. In the agomelatine group, three participants (3%) experienced serious adverse events (2 people had surgical procedures, and 1 had fibrocystic breast disease). In the placebo group four participants (4%) experienced serious adverse events (2 people had suicidal depression and panic attacks, 1 had a spinal operation, and 1 had prostate cancer stage II) (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.30; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 6 Number of persons with at least one severe adverse event.

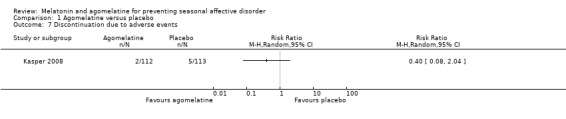

2.7 Rates of discontinuation due to adverse events

Seven of 225 participants (3%) discontinued the study early due to adverse events. Two withdrew from the agomelatine group due to atrial fibrillation or rheumatoid arthritis, and five withdrew from the placebo group due to psychiatric disorders (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.04; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 7 Discontinuation due to adverse events.

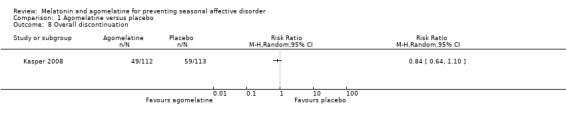

2.8 Overall rate of discontinuation

Throughout the complete prevention study, 108 participants left the study, 49 in the agomelatine group (44%), and 59 in the placebo group (52%) (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.10; 225 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine versus placebo, Outcome 8 Overall discontinuation.

Comparison 3: melatonin versus agomelatine

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 4: melatonin versus second‐generation antidepressants

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 5: agomelatine versus second‐generation antidepressants

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 6: melatonin versus light therapy

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 7: agomelatine versus light therapy

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 8: melatonin versus psychological therapy

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 9: agomelatine versus psychological therapy

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 10: melatonin versus lifestyle intervention

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 11: agomelatine versus lifestyle intervention

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 12: agomelatine/melatonin + comparator intervention versus placebo

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Comparison 13: agomelatine/melatonin + comparator intervention versus the same comparator intervention as monotherapy

We found no eligible studies assessing this comparison.

Subgroup analyses

Data were insufficient for subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

Data were insufficient for sensitivity analyses.

Reporting bias

As we identified only one study; statistical approaches to assessment of publication bias are not possible.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Overall, the evidence for agomelatine was inconclusive, because the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were broad for all efficacy and safety outcomes. We did not identify any evidence on melatonin for prevention of SAD. The attrition rate was very high in both arms of the included study, with 45% from the agomelatine group and 52% from the placebo group discontinuing the study early, impacting the validity of the results. Table 1 shows that the certainty of evidence was very low for all outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In the previous version of this Cochrane Review we contacted the pharmaceutical company Les Laboratoires Servier to include unpublished data on efficacy and safety of agomelatine, but received no information. In this update we succeeded to access these trial data via the European Medicines Agency (EMA). However, one limitation of our report is that despite the comprehensive search, we identified only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) with data on 225 participants, but with a high attrition rate. The main analysis for efficacy did not employ a full intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. In addition, using the last observed values of participants who dropped‐out of the study might underestimate the incidence of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) because it could be possible that these participants developed depression after they left the study. The participants were all treated with agomelatine in the preceding winter and only those with stable remission for at least two months were eligible for the prevention study. This procedure does not reflect a real world prevention situation.

Overall, there seems to be a lack of research on prevention of SAD; this was also detected in the other Cochrane Reviews on SAD prevention. In addition, each of the reviews on light therapy (Nussbaumer‐Streit 2019), and psychotherapy (Forneris 2019), for SAD prevention only identified one small high risk of bias study, precluding us from making conclusions on benefits and harms of these interventions. Only the review on antidepressants for prevention of SAD identified three well‐conducted RCTs that provided moderate certainty of evidence, indicating that bupropion extended‐released (bupropion XL) is effective for preventing recurrence of SAD. Nevertheless, even in a high‐risk population, three out of four people will not benefit from preventive treatment with bupropion XL and will be at risk for harm (Gartlehner 2019). Despite this lack of evidence, preventive treatment in patients with SAD seems to often be implemented in clinical practice. A survey in German‐speaking countries showed that 73% of 81 hospitals reported recommending psychotherapy for SAD prevention in people with a history of SAD; 84% recommended antidepressants, 72% light therapy, and 47% agomelatine (Nussbaumer‐Streit 2017). Besides the evidence on benefits and harms of an intervention, peoples' preferences also need to be taken into consideration. A recent qualitative study showed that people with a history of SAD often do not want to take antidepressants and preferred non‐pharmacological treatments (Nussbaumer‐Streit 2018).

Certainty of the evidence

We graded the certainty of the evidence for all available outcomes (incidence of SAD, adverse events, severity of SAD, serious adverse events, discontinuation due to adverse events, and overall discontinuation) as very low. Reasons for downgrading the certainty of evidence included high risk of bias of the included study, indirectness because the study sample was part of a preceding open‐label agomelatine trial not representing a real‐life prevention scenario, and imprecision due to the small sample size.

Potential biases in the review process

Publication bias is a threat for any systematic review. Although we searched for grey and unpublished literature, the extent and impact of reporting biases of this body of evidence is impossible to determine.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

One open‐label study assessed the efficacy of agomelatine in treatment of acute depressive episodes in 37 SAD patients. They measured a statistically significant decrease of SIGH‐SAD scores from week two onwards in the agomelatine group. They measured a response rate of 76% and a remission rate of 70%, concluding that agomelatine might be an effective treatment option for SAD (Pjrek 2007). However, the study was very small and the effects could be affected by random error. Two studies assessed agomelatine for relapse prevention in people suffering from major depressive disorder (without a seasonal pattern) and showed inconsistent results. One double‐blinded multicentre trial showed similar relapse rates in the agomelatine group (25%, 48/185) and the placebo group (24%, 42/179) (study number CL3‐21). Another study, however, showed lower relapse rates in the agomelatine group (21%, 34/165) compared to the placebo group (41%, 72/174; P = 0.0001) (study number CL3‐41) (EMA 2009). Agomelatine was associated with serious side effects in the past and not approved in the US due to cases of hepatoxicity (Srinivasan 2012).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Given the uncertain evidence on agomelatine and the absence of studies on melatonin, no conclusion about efficacy and safety of agomelatine and melatonin for prevention of SAD can currently be drawn. Clinicians and people with a history of SAD should consider patient preferences and reflect on the evidence base when making decisions.

Implications for research.

Independently funded randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy and safety of agomelatine and/or melatonin for the prevention of SAD compared to placebo and other active treatments are necessary. So far, we identified only one trial with high attrition rates. Future studies should include a large sample (to reach at least a statistical power of 80%), must initiate the intervention when people with a history of SAD are free of depressive symptoms, and should aim for low attrition rates.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 June 2019 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Review updated. New study added |

| 10 June 2019 | New search has been performed | We updated the searches on 19 June 2018; we identified one new study. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Evelyn Auer and Sandra Hummel for providing administrative support during the course of this review. We would also like to thank Julia Hoffmann and Jeffrey H Sonis for their support when conducting the former version of this Cochrane Review.

The authors and the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Editorial Team, are grateful to the following peer reviewers and editors for their time and comments: Raymond Lam, Philip Kerrigan, and Lindsay Robertson. They would also like to thank copy editor, Clare Dooley.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group.

Disclaimer: views and opinions expressed herein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CCMDCTR: Core MEDLINE search

The search strategy listed below is the weekly OVID Medline search which was used to inform the Group’s specialised register (to June 2016). It is based on a list of terms for all conditions within the scope of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group plus a sensitive RCT filter.

OVID MEDLINE search strategy, used to inform the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Specialised Register A weekly search alert based on condition + RCT filter only 1. [MeSH Headings]: eating disorders/ or anorexia nervosa/ or binge‐eating disorder/ or bulimia nervosa/ or female athlete triad syndrome/ or pica/ or hyperphagia/ or bulimia/ or self‐injurious behavior/ or self mutilation/ or suicide/ or suicidal ideation/ or suicide, attempted/ or mood disorders/ or affective disorders, psychotic/ or bipolar disorder/ or cyclothymic disorder/ or depressive disorder/ or depression, postpartum/ or depressive disorder, major/ or depressive disorder, treatment‐resistant/ or dysthymic disorder/ or seasonal affective disorder/ or neurotic disorders/ or depression/ or adjustment disorders/ or exp antidepressive agents/ or anxiety disorders/ or agoraphobia/ or neurocirculatory asthenia/ or obsessive‐compulsive disorder/ or obsessive hoarding/ or panic disorder/ or phobic disorders/ or stress disorders, traumatic/ or combat disorders/ or stress disorders, post‐traumatic/ or stress disorders, traumatic, acute/ or anxiety/ or anxiety, castration/ or koro/ or anxiety, separation/ or panic/ or exp anti‐anxiety agents/ or somatoform disorders/ or body dysmorphic disorders/ or conversion disorder/ or hypochondriasis/ or neurasthenia/ or hysteria/ or munchausen syndrome by proxy/ or munchausen syndrome/ or fatigue syndrome, chronic/ or obsessive behavior/ or compulsive behavior/ or behavior, addictive/ or impulse control disorders/ or firesetting behavior/ or gambling/ or trichotillomania/ or stress, psychological/ or burnout, professional/ or sexual dysfunctions, psychological/ or vaginismus/ or Anhedonia/ or Affective Symptoms/ or *Mental Disorders/ 2. [Title/ Author Keywords]: (eating disorder* or anorexia nervosa or bulimi* or binge eat* or (self adj (injur* or mutilat*)) or suicide* or suicidal or parasuicid* or mood disorder* or affective disorder* or bipolar i or bipolar ii or (bipolar and (affective or disorder*)) or mania or manic or cyclothymic* or depression or depressive or dysthymi* or neurotic or neurosis or adjustment disorder* or antidepress* or anxiety disorder* or agoraphobia or obsess* or compulsi* or panic or phobi* or ptsd or posttrauma* or post trauma* or combat or somatoform or somati#ation or medical* unexplained or body dysmorphi* or conversion disorder or hypochondria* or neurastheni* or hysteria or munchausen or chronic fatigue* or gambling or trichotillomania or vaginismus or anhedoni* or affective symptoms or mental disorder* or mental health).ti,kf. 3. [RCT filter]: (controlled clinical trial.pt. or randomized controlled trial.pt. or (randomi#ed or randomi#ation).ab,ti. or randomly.ab. or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or control* or determine* or divide* or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or recruit* or subsitut* or treat*)).ab. or placebo*.ab,ti. or drug therapy.fs. or trial.ab,ti. or groups.ab. or (control* adj3 (trial* or study or studies)).ab,ti. or ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) adj3 (blind* or mask* or dummy*)).mp. or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or randomized controlled trial/ or pragmatic clinical trial/ or (quasi adj (experimental or random*)).ti,ab. or ((waitlist* or wait* list* or treatment as usual or TAU) adj3 (control or group)).ab.) 4. (1 and 2 and 3)

Records are screened for reports of RCTs within the scope of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group. Secondary reports of RCTs are tagged to the appropriate study record. Similar weekly search alerts are also conducted on OVID Embase and PsycINFO, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource.

Appendix 2. Database searches 2014

PubMed 26.05.2014

| Search | Query | Items found |

| #1 | Search "Seasonal Affective Disorder"[Mesh] | 1061 |

| #2 | Search "seasonal affective disorder"[All Fields] | 1415 |

| #3 | Search seasonal affective disorder* | 1451 |

| #4 | Search "seasonal depression"[All Fields] | 162 |

| #5 | Search seasonal mood disorder* | 10 |

| #6 | Search "winter depression" | 248 |

| #7 | Search SIGH‐SAD | 61 |

| #8 | Search (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) | 1555 |

| #9 | Search (#8 AND 2013/05:2014[dp]) | 46 |

The Cochrane Library 26.05.2014

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | seasonal affective disorder (Word variations have been searched) | 312 |

| #2 | winter blues (Word variations have been searched) | 25 |

| #3 | seasonal depression | 295 |

| #4 | seasonal mood disorder | 134 |

| #5 | winter depression | 256 |

| #6 | SIGH‐SAD | 39 |

| #7 | {or #1‐#6} Publication Date from 2013 to 2014 | 69 |

EMBASE 26.05.2014

| No. | Query | Results |

| #1 | 'seasonal affective disorder'/exp AND [humans]/lim AND [embase]/lim | 640 |

| #3 | 'seasonal affective disorder'/mj | 484 |

| #4 | #1 OR #3 | 831 |

| #5 | #4 AND [2013‐2014]/py | 79 |

PsycINFO, AMED, IPA, CINAHL (via EBSCO HOST) 26.05.2014

| # | Query | Limiters/Expanders | Last Run Via | Results |

| S1 | seasonal affective disorder | Limiters ‐ Published Date: 20130501‐ | Interface ‐ EBSCOhost Research Databases | 39 |

| Search modes ‐ Boolean/Phrase | Search Screen ‐ Advanced Search | |||

| Database ‐ PsycINFO;AMED ‐ The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database;CINAHL with Full Text;International Pharmaceutical Abstracts |

Web of Knowledge (via UNC) 28.05.2014

| Set | Results | |

| # 5 | 69 | #4 AND #1 |

| Timespan=2013‐2014 | ||

| Search language=English | ||

| # 4 | Approximately | #3 OR #2 |

| 1,107,073 | Timespan=2013‐2014 | |

| Search language=English | ||

| # 3 | Approximately | TOPIC: (treatment) |

| 975,242 | Timespan=2013‐2014 | |

| Search language=English | ||

| # 2 | Approximately | TOPIC: (prevention) |

| 188,628 | Timespan=2013‐2014 | |

| Search language=English | ||

| # 1 | 165 | TOPIC: ("seasonal affective disorder") |

| Timespan=2013‐2014 | ||

| Search language=English |

Appendix 3. Database searches 2018

Summary of searches (19 June 2018)

CCMD Register, n = 8

CENTRAL, n = 30

MEDLINE, n = 233

Embase, n = 301

PsycINFO, n = 154

International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, (database unavailable)

CINHAL, n = 77

Web of Knowledge, n = 489

AMED, n = 1

Total = 1293 Duplicates removed = 607 Number to screen = 686

Database search strategies

CCMD‐CTR (searched via Cochrane CRS) Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 (Register current to June 2016, only) Hits: 303 (8 in scope for this update) 1"seasonal affective disorder" AND INREGISTER (277) 2seasonal affective disorder* AND INREGISTER (280) 3"seasonal depression" AND INREGISTER34 4 seasonal mood disorder* AND INREGISTER (6) 5 "winter depression" AND INREGISTER (72) 6 SIGH‐SAD AND INREGISTER (48) 7 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 (303) Cochrane CENTRAL searched the Cochrane Library (Wiley interface) Data parameters: Issue 5 of 12, May 2018 Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 363 (30 in scope for this update) #1 MeSH descriptor: [Seasonal Affective Disorder] explode all trees 172 #2 "seasonal affective disorder" 364 #3 seasonal affective disorder* 397 #4 "seasonal depression" 46 #5 seasonal mood disorder* 199 #6 "winter depression" 85 #7 SIGH‐SAD 55 #8 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7) 452 Notes: Of 452 returned from searching The Cochrane Library, 363 were records from CENTRAL. Records dating pre‐2015 were visually inspected and manually removed.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) Data parameters: 1946 to Present Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 233 1 Seasonal Affective Disorder/1180 2 "seasonal affective disorder".ti,ab,kw,ot.1206 3 seasonal affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot.1277 4 "seasonal depression".ti,ab,kw,ot.188 5 seasonal mood disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot.12 6 "winter depression".ti,ab,kw,ot.272 7 SIGH‐SAD.ti,ab,kw,ot.78 8 (1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7) 1790 9 (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018*).yr,ed. 4792024 10 (8 and 9) 233

Embase (Ovid Interface) Data parameters: 1974 to 2018 June 18 Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 301 1 Seasonal Affective Disorder/ 1239 2 "seasonal affective disorder".ti,ab,kw,ot. 1528 3 seasonal affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 1618 4 "seasonal depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 246 5 seasonal mood disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 23 6 "winter depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 334 7 SIGH‐SAD.ti,ab,kw,ot. 92 8 (1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7) 2297 9 (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018*).yr,ed. 4907927 10 (8 and 9) 301

PsycINFO (Ovid) Data parameters: 2002 to June Week 2 2018 Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 154 1 Seasonal Affective Disorder/ 484 2 "seasonal affective disorder".ti,ab,kw,ot. 511 3 seasonal affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 529 4 "seasonal depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 94 5 seasonal mood disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 6 6 "winter depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 72 7 SIGH‐SAD.ti,ab,kw,ot. 53 8 (1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7) 690 9 (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018*).yr,ed. 633488 10 (8 and 9) 154

CINAHL via EBSCOHost Data parameters: 1937‐Current Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 77 S9 (S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7) Limiters: Published Date (20150101 ‐ 20180631) 77 S8 (S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7) 454 S7 TI SIGH‐SAD OR AB SIGH‐SAD 15 S6 TI "winter depression" OR AB "winter depression" 24 S5 TI seasonal mood disorder* OR AB seasonal mood disorder* 16 S4 TI "seasonal depression" OR AB "seasonal depression" 43 S3 TI Seasonal Affective Disorder* OR AB Seasonal Affective Disorder* 287 S2 TI "Seasonal Affective Disorder" OR AB "Seasonal Affective Disorder" 276 S1 (MM "Seasonal Affective Disorder") 365

Web of Science (Web of Science Core Collection, BIOSIS, Data citation Index, KCI Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, Russian Science Citation Database, SciELO Citation Index)* Data parameters: 1900 to Present Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 489 #8 TOPIC ((#6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1) Refined by: PUBLICATION YEARS (2018 OR 2017 OR 2016 OR 2015) 489 #7 TOPIC (#6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1) 3819 #6 TOPIC (SIGH‐SAD) 84 #5 TOPIC ("winter depression") 790 #4 TOPIC (seasonal mood disorder*) 1525 #3 TOPIC ("seasonal depression") 267 #2 TOPIC (Seasonal Affective Disorder*) 3355 #1 TOPIC ("Seasonal Affective Disorder") 3007

Notes: In the 2015 review, which these searches update, Web of Knowledge was searched. Web of Knowledge (containing Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, BIOSIS, Derwent Innovations Index, Data Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index) has been discontinued. This search was the closest representation of the previous search.

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) Data parameters: 1985 to June 2018 Date searched: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Hits: 1 1 Seasonal Affective Disorder/ 0 2 "seasonal affective disorder".ti,ab,kw,ot. 28 3 seasonal affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 28 4 "seasonal depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 2 5 seasonal mood disorder*.ti,ab,kw,ot. 0 6 "winter depression".ti,ab,kw,ot. 4 7 SIGH‐SAD.ti,ab,kw,ot. 2 8 (1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7) 32 9 (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018*).yr,ed. 22289 10 (8 and 9) 1

Trials registers WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) searched via: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx search date: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 seasonal n = 113 records for 49 trials. These records were visually inspected and 20 records were retained for screening SIGH‐SAD n = 0 ClinicalTrials.Gov searched via: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home search date: Tuesday, 19th June 2018 Records were visually inspected and records 2015‐current when exported to Endnote. Search field: Condition or Disease seasonal affective n = 3 seasonal depression n = 3 (being duplicates of the above) SIGH‐SAD n = 0

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Agomelatine versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of SAD (modified ITT) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Incidence of SAD (ITT, assuming no dropout was depressed) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Incidence of SAD (ITT, assuming all dropouts were depressed) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Number of persons with at least one adverse event | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Severity of depression (SIGH‐SAD score at end of study)), modified ITT | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Number of persons with at least one severe adverse event | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Discontinuation due to adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Overall discontinuation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kasper 2008.

| Methods |

Study design: Multicentre, blinded, randomised controlled trial Duration of study: September 2002 ‐ June 2005 "Run‐in" period: This study was preceeded by an open‐label study period (25 mg agomelatine) of at least 18 weeks. Duration of treatment period: 1 year treatment period beginning in May Number of study centres and locations: 25 centres located in 8 countries: Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Sweden Study setting: Ambulatory or hospitalized Withdrawals: 48% (108 of 225) |

|

| Participants |