Overview

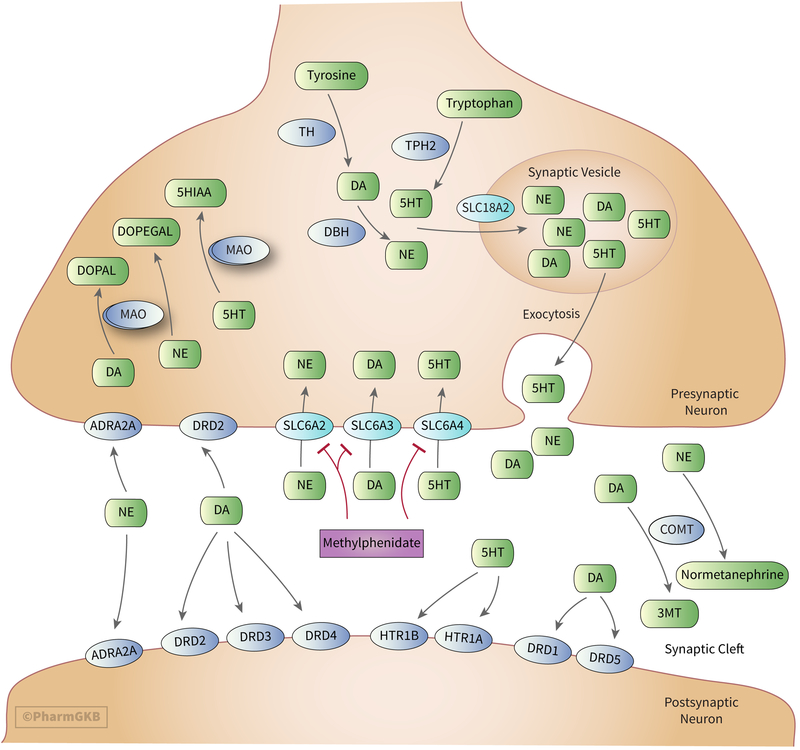

Methylphenidate (MPH) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant primarily used for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). MPH works by preventing the reuptake of dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) through inhibition of the DA (SLC6A3) and NE transporters (SLC6A2), resulting in an increase of extracellular DA and NE. The bulk of research examining the pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics of MPH focuses on SLC6A3, SLC6A2 and their respective genes. Other research regarding MPH pharmacodynamics analyzes proteins involved in the processing of neurotransmitters, how altering the concentration of neurotransmitters affects binding to their respective receptors, and the proteins involved in the subsequent downstream effects of these changes. From a pharmacokinetic standpoint, MPH is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1).

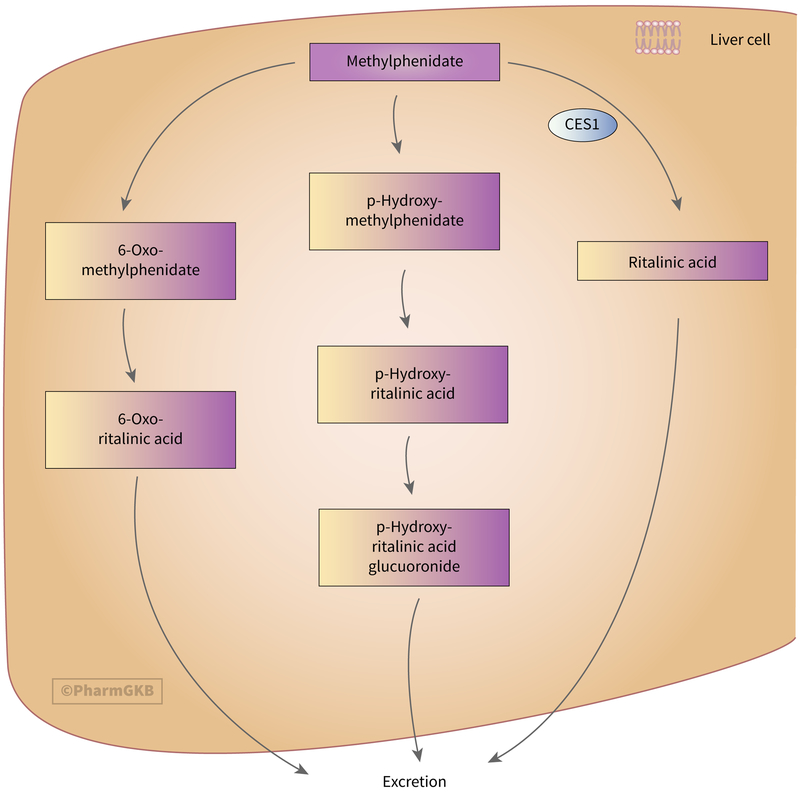

Pharmacokinetics of MPH and Pharmacogenetics of CES1

The primary metabolic pathway of MPH involves CES1, primarily expressed in the liver (Fig. 1) [1]. CES1 mediates de-esterification of MPH to the inactive metabolite aphenyl-2-piperidine acetic acid, more commonly known as ritalinic acid (RA). This de-esterification heavily favors the stereoselective hydrolysis of the l-isomer of MPH (l-MPH) [1], resulting in the d-isomer of MPH (dexmethylphenidate, d-MPH) as the primary isomer found in plasma [2]. Further, only d-MPH has been shown to exhibit significant pharmacological activity, with no metabolic conversion between d- and l-MPH [3]. Most formulations of MPH contain a racemic mixture of d- and l-MPH, although there are formulations available of d-MPH alone. While CES1 is closely related to carboxylesterase 2 (CES2) [4, 5], MPH is metabolized solely by CES1 [1].

Figure 1.

Stylized diagram showing methylphenidate metabolism in the liver. A fully clickable version of this figure can be found at https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166181002.

In several single dose pharmacokinetic studies, 60–80% of administered doses were recovered as RA in human urine after 48 hours [6–9]. Microsomal oxidation and aromatic hydroxylation of MPH in humans also produce the inactive metabolites 6-oxo-methylphenidate (6-oxo-MPH) and p-hydroxy-methylphenidate (p-hydroxy-MPH) respectively [6]. The metabolite p-hydroxy-MPH has been shown to exhibit pharmacological activity in mice; however, this has not been studied in humans [10]. The metabolite 6-oxo-MPH is converted to 6-oxo-ritalinic acid via de-esterification, with the sum of these 6-oxo- metabolites accounting for up to 1.5% of the total dose [6]. This is less than what was previously reported by Bartlett and Egger, who reported 6-oxo-ritalinic acid accounting for 5 to 12% of the administered dose [9]. Similarly, p-hydroxy-MPH is metabolized by de-esterification to p-hydroxy-ritalinic acid and subsequently glucuronidated to p-hydroxy-ritalinic acid glucuronide and accounts for up to 2.5% of the total dose of MPH [6]. These downstream metabolites of 6-oxo-MPH and p-hydroxy-MPH are also inactive [6]. Fecal excretion of MPH and its metabolites account for up to 3% of the total dose, while less than 2% of the total dose is excreted unchanged in the urine [6, 9]. It was previously hypothesized that MPH was metabolized by cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) due to the observed activity at inhibiting CYP2D6 substrates [11, 12]; however, this hypothesis was not supported in a pharmacokinetic study in humans with and without quinidine (a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor) [13].

An additional transesterification metabolite (l-ethylphenidate) is formed when MPH is taken concomitantly with ethanol [14]. In an open, 3-way randomized crossover study, subjects were administered standardized doses of MPH with and without ethanol. The AUC values of MPH were significantly higher when ethanol was administered 30 minutes before and after MPH (105.2 and 102.8 ng*hr/ml (P < 0.0001)) as compared to no ethanol administration (82.9 ng*hr/ml). Cmax values of d-MPH were similarly increased upon ethanol administration (21.5 and 21.4 ng/ml (P < 0.0001)) before and after MPH as compared to without ethanol (15.3 ng/ml). The results of this study demonstrate increased exposure to MPH and the pharmacologically active compound ethylphenidate, raising concerns about the abuse potential when ingested with ethanol [15].

Pharmacogenomic studies of CES1 are complicated by the inactive truncated pseudogene CES1P1, also referred to as CES1A3, located near CES1 on chromosome 16. The ‘wild-type’ haplotype of CES1 consists of CES1 (also referred to as CES1A1) and the inactive CES1P1. Hypothesized to have been created through gene exchange events, CES1P1 can form hybrid genes with CES1 which can have increased transcriptional activity relative to CES1P1 [16]. Additionally, CES1 and CES1P1 can form the hybrid gene variant CES1A2, which has 2% of the transcriptional efficiency of CES1 [17]. Other identified hybrid variants include CES1A1b and CES1A1c, also known as CES1VAR [16]. Multiple haplotypes and diplotypes exist with these various CES1 variants, and individuals can carry more than two active copies of CES1 (i.e. two CES1 copies and one CES1A2 copy for a copy number of three or two CES1 copies and two CES1A2 copies for a copy number of four) [16, 18].

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacogenetic studies of MPH and CES1 have focused on rs71647871, commonly referred by the amino acid substitution G143E. An individual heterozygous for the G143E variant and a rare Asp260fs frameshift variant resulting in a premature stop codon was compared to 19 individuals without these variants. The AUC, Cmax and t1/2 of the individuals without the noted variants were 78.6 ng/ml* hrs, 13.8 ng/ml, and 3.0 hrs, respectively, while the same values for the individual with the two variants were 208.7 ng/ml*hrs, 36 ng/ml and 5.4 hrs (p < 0.01 for all parameters) [19]. In a separate 30-day, prospective study of 122 children with ADHD providers titrated the dose of MPH between 10–30 mg in two doses to achieve adequate medication response. Subjects were then classified as responders or non-responders based on the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) assessment. There was no difference in response rate when comparing individuals with the G143E variant to those without the variant; however, amongst responders, those that were heterozygous for the G143E variant (n = 5) required significantly lower doses (0.41 mg/kg/day vs. 0.57 mg/kg/day; p = 0.022) of MPH than those without the variant (n = 85) [20]. This decreased dosing requirement in G143E variants supports decreased metabolic conversion of MPH to the inactive RA. This was further supported by a single-dose pharmacokinetic study (n = 44) in which G143E carriers had a 149% increase in AUC as compared to the control subjects (P < 0.0001). Notably, individuals with 4 copies of CES1 had 45% (P = 0.011) and 61% (P = 0.028) increased AUCs of d-MPH as compared to control participants and those with 3 copies of CES1. With increased copy number, it would be expected that there would be increased CES1 activity, and therefore increased metabolism of MPH resulting in smaller AUCs; however, due to the inability to sequence past exon 5 in this study attributed to difficulties sequencing CES1 gene duplications, it is hypothesized that the decreased metabolic activity observed in these individuals may be due to polymorphisms downstream of exon 5 [18].

As a CNS stimulant crossing the blood-brain barrier, the role of MPH as a substrate for the efflux transporter p-glycoprotein (P-gp) (encoded by ABCB1) has also been examined. A study in mice found that P-gp knockout mice had 33% higher brain concentrations of d-MPH (p < 0.05) than wild-type control mice 10 minutes after dosing but not at other measured time intervals past 10 minutes, suggesting d-MPH is a weak P-gp substrate [21]. A follow-up in vitro study in porcine kidney epithelial cells found that the potent P-gp inhibitor PSC833 did not significantly alter d-MPH levels, supporting the previous study that d-MPH is a minor substrate of P-gp [22]. Lastly, a clinical, open-label dose titration trial of MPH-naive Korean subjects administered MPH extended release for 4 weeks found that of 134 sequenced subjects, individuals homozygous for the ABCB1 c.2677G>T (rs2032582) variant were at an increased risk for experiencing adverse drug reactions (P = 0.005; OR: 9.04) [23].

Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacogenomics of Pharmacodynamic Genes

MPH elicits its effects by blocking the reuptake of DA and NE into the presynaptic neuron through inhibition of the SLC6A3 and SLC6A2 (Fig. 2) [24–40] resulting in increases in extracellular concentrations of DA and NE [36, 41–50]. MPH also has weak effects at blocking the reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) at the serotonin transporter (SLC6A4), although this is thought to be at clinically insignificant levels. An in vitro study utilizing human SLC6A2, SLC6A3, and SLC6A4 demonstrated MPH has about 1300-fold greater affinity for SLC6A2, and about 2200-fold greater affinity for SLC6A3 compared to SLC6A4 [34]. Other studies have measured MPH’s affinity for SLC6A4 below the limit of detection or have found no demonstrable effect [33, 35, 48].

Figure 2.

Stylized diagram showing the synthesis, degradation, release and uptake of monoamines, synaptic effectors and targets of methylphenidate. A fully clickable version of this figure can be found at https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166181140 .

As previously stated, MPH is a racemic mixture of l- and d-MPH enantiomers, with varying affinities for the transporters of interest. The impact of increased catecholamine concentrations has been shown to result in improvements in cognition [51–53], memory [54], and impulsivity [55], which are primarily mediated through the indirect activation of DA and NE receptors as discussed below. In an in vitro animal study assessing the affinity of MPH for different transporters in rat brain membranes, the mean IC50 values of d-MPH for SLC6A3, SLC6A2 and SLC6A4 were 33, 244 and >50,000 nM, respectively. The corresponding values for l-MPH were 540, 5100 and >50,000 nM [35]. A similar study conducted in human and canine kidney cells measured mean IC50 values of 34, 339 and >10,000 for SLC6A3, SLC6A2 and SLC6A4 with racemic MPH [41]. The results of these studies demonstrate the selective pharmacological activity of d-MPH over l-MPH at SLC6A3 and SLC6A2 and have led to MPH formulations exclusively of d-MPH. The following sections will focus on associations between variation in pharmacodynamic genes and MPH response, observed associations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Summary of observed associations between variation in pharmacodynamic genes and methylphenidate (see text for studies reporting no association).

| Gene | Variant(s) | Genotype/phenotype/haplotype | Association (rating scale/measurement) | P value | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotransmitter Synthesis and Degradation | |||||

| TH | rs2070762 | C/C | Decreased response (CGI-I) | 0.0055 | 26810137 |

| DBH | rs1541332, rs2073833 | TC haplotype | Increased treatment failure (CGI-S) | 0.011 | 26810137 |

| DBH | rs2073833 | C/C | Increased treatment failure (CGI-I) | 0.03 | 26810137 |

| DBH | rs2007153, rs2797853, rs77905 | AGC haplotype | Decreased risk of adverse events | 0.02 | 26810137 |

| TPH2 | rs1386488, rs2220330, rs1386495, rs1386494, rs6582072, rs1386492, rs4760814, rs1386497 | CGCAAGAC (‘Yang’ haplotype) vs AATGGAGA (‘Yin’ haplotype) | Increased score improvement (TOVA) | 0.009 | 18213624 |

| MAOA | 30-bp promoter VNTR | 4-repeat allele vs 3-repeat allele | Improved response (SNAP-IV oppositional) | 0.009 | 19309535 |

| MAOA | 30-bp promoter VNTR | 4- and 5-repeat alleles | Improved impulsivity scores (TOVA) | 12140786 | |

| COMT | rs4680 | G/G | Increased response rate (ADHD-RS, CGI-S) | 0.034 | 18214865 |

| COMT | rs4680 | G/G | Increased response rate (K-ARS) | 0.035 | 18703939 |

| COMT | rs4680 | G/G | Increased response(meta-analysis) | 0.02 | 29230023 |

| COMT | rs4680 | G/G | Increased irritability | 0.02 | 19858760 |

| COMT | rs4680 | G | Increased sadness | <0.05 | 22149470 |

| Neurotransmitter Reuptake | |||||

| SLC6A2 | rs28386840 | A/A | Decreased response(CGI-I) | 0.008 | 20929549 |

| SLC6A2 | rs28386840 | A/A | Decreased response (TOVA) | 0.003 | 22591463 |

| SLC6A2 | rs28386840 | A/A | Decreased response (ADHD-RS and CGI-I) | 0.02 | 23083021 |

| SLC6A2 | rs28386840 | T | Increased response(meta-analysis) | <0.0001 | 29230023 |

| SLC6A2 | rs28386840 | T/T | Increased HR | 0.01 | 21628343 |

| SLC6A2 | rs5569 | G | Increased response (ADHD-RS) | 0.012 | 15322419 |

| SLC6A2 | rs5569 | G/G | Increased response (ADHD-RS and CGI-S) | 0.008 | 21127421 |

| SLC6A2 | rs5569 | G/G | Increased response (TOVA) | 0.006 | 22591463 |

| SLC6A2 | rs5569 | G/G | Increased response(meta-analysis) | 0.0007 | 29230023 |

| SLC6A3 | rs28363170 | Lack of 10R allele | Improved hyperactive-impulsive scores (Vanderbilt ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scales) | 0.008 | 22024001 |

| SLC6A3 | rs28363170 | 9R/9R | Decreased response (ADHD-RS) | 0.012 | 24813374 |

| SLC6A3 | rs28363170 | 10R/10R | Improvements in working memory (N-Back Test) | 0.002 | 23541676 |

| SLC6A3 | rs28363170 | 10R/10R | Decreased response (meta-analysis, naturalistic trials) | 0.03 | 23588108 |

| SLC6A3 | rs28363170 | 10R/10R | Decreased response (meta-analysis) | 0.004 | 29230023 |

| SLC6A3 | rs2550948 | G | Increased response (CGI-S) | 0.011 | 28871191 |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTTLPR | L/L (also DRD4 7R carriers) | Decreased symptom improvement (CGAS) | 0.001 | 11684336 |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTTLPR | L | Lower math scores (PERMP) | 0.02 | 19858760 |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTTLPR | L/L | Decreased vegetative symptoms (sleep problems and appetite loss) | 0.003 | 19858760 |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTTLPR | L | Increased nail-biting | 0.017 | 26402385 |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTTLPR | L | Increased tics | < 0.001 | 26402385 |

| SLC6A4 | 17-bp VNTR | Lack of 12R allele | Decreased symptom improvement (ADHD-RS) | 0.01 | 19858760 |

| SLC6A4 | 17-bp VNTR | 12R/12R | Reduced response rate (CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale) | 0.041 | 23856854 |

| Neurotransmitter Receptor Binding | |||||

| DRD1 | rs4867798 | G | Increased response (CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale) | 0.042 | 23856854 |

| DRD1 | rs5326 | A | Increased response (CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale) | 0.006 | 23856854 |

| DRD3 | rs6280 | A/A | Increased response (CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale) | 0.044 | 23856854 |

| DRD2 | rs2283265 | T (MPH dose as covariate) | Increased risk of any adverse effect | 0.047 | 26810137 |

| ANKK1 | rs1800497 | A2/A2 | Decreased appetite | 0.007 | 19364291 |

| DRD3 | rs2134655, rs1800828 | Carriers of G for both SNPs | Increased treatment failure (CGI-I) | 0.041 | 26810137 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | 4R/4R | Increased response (ADHD-RS) | < 0.01 | 17077808 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | Lack of 4R allele | Decreased improvement in hyperactive-impulsive scores (Vanderbilt ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scales) | 0.02 | 22024001 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | 4R/4R | Increased response(meta-analysis) | 0.005 | 29230023 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | 7R | Increased response and gene transmission (TDT) | 0.049 | 10889550 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | 7R (combined with L/L genotype of SLC6A4 5HTTLPR) | Decreased response (CGAS) | 0.001 | 11684336 |

| DRD4 | 48-bp VNTR | 7R | Increased dose required for response (Conners’ Global Index-Parent) | 0.002 | 15662148 |

| DRD4 | 120-bp promoter duplication | L/L | Increased response (Teacher CLAM-SKAMP) | 0.05 | 17023870 |

| DRD4 | 120-bp promoter duplication | S/S | Decreased response (CGAS and CGI-S) | 0.001 | 28871191 |

| DRD4 | rs11246226 | A/A | Increased response (CGI-S and ABC-hyperactivity subscale) | 0.038 | 23856854 |

| ADRA2A | rs1800544 | G | Decreased inattentive score (SNAP-IV) | 0.02 | 17283289 |

| ADRA2A | rs1800544 | G | Decreased inattentive score (SNAP-IV) | 0.016 | 18200436 |

| ADRA2A | rs1800544 | G/G | Increased response (ADHD-RS parent) | 0.003 | 19150055 |

| ADRA2A | rs1800544 | G | Increased response(meta-analysis) | 0.01 | 29230023 |

| ADRA2A | rs1800544 | C/C | Increased diastolic blood pressure | 0.009 | 21628343 |

| Neurotransmitter Release | |||||

| SNAP25 | rs3746544 | T/T | Improved response (ADHD-RS) | 0.034 | 25229170 |

| SNAP25 | rs3746544 | T/T | Decreased response (CGI-S) | 0.018 | 28871191 |

| SNAP25 | rs3746544 | G | Decreased irritability | 0.04 | 17023870 |

| SNAP25 | rs1051312 | C | Decreased motor tics | 0.02 | 17023870 |

| SNAP25 | rs1051312 | C | Decreased buccal-lingual movements | 0.01 | 17023870 |

| SNAP25 | rs1051312 | C | Decreased picking/biting | 0.05 | 17023870 |

| Neuronal/Synaptic Plasticity and Synaptic Effectors | |||||

| ADGRL3 | rs6551665, rs1947274, rs6858066 | AAG haplotype | Decreased response (CGI-I) | 22486528 | |

| ADGRL3 | rs6551665, rs1947274, rs6858066 | GCA haplotype | Increased response (CGI-I) | 22486528 | |

| ADGRL3 | rs6551665 | G | Decreased response (RAST) | 0.005 | 22851411 |

| ADGRL3 | rs1947274 | C | Decreased response (RAST) | 0.005 | 22851411 |

| ADGRL3 | rs6858066 | G | Increased response (RAST) | 0.006 | 22851411 |

| ADGRL3 | rs2345039 | G | Decreased response (RAST) | 0.0002 | 22851411 |

| ADGRL3 | rs6813183, rs1355368, rs734644 | CGC haplotype | Increased response (SNAP-IV) | < 0.001 | 25989180 |

| ADGRL3 | rs1868790 | A/A | Decreased response (CGI-S) | 0.026 | 28871191 |

| BDNF | rs6265 | G/G | Increased response (CGI-S) | 0.0002 | 21733227 |

| NTF3 | rs6332 | A/A | Increased emotionality | 0.042 | 23471121 |

| NTF3 | rs6332 | A/A | Increased over-focus/euphoria | 0.045 | 23471121 |

| NTF3 | rs6332 | A/A | Increased proneness to crying | 0.047 | 23471121 |

| NTF3 | rs6332 | A/A | Increased nail-biting | 0.017 | 23471121 |

| GRM7 | rs3792452 | G/A | Increased response (ADHD-RS parent, CGI-I) | 0.011, 0.044 | 24815731 |

| GRIN2B | rs2284411 | C/C | Improved response (ADHD-RS inattentive, CGI-I) | 0.009, 0.009 | 27624150 |

| Downstream Neurotransmitter Effects | |||||

| AKT1 | intron 3 VNTR | H/H > H/L > L/L | Increased DA release | 0.009 | 28416594 |

Abbreviations: ABC=Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADGRL3=adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3; ADHD-RS=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-rating scale; ADRA2A=alpha-2A adrenergic receptor; AKT1=AKT serine/threonine kinase 1; ANKK1=kinase domain containing 1; BDNF=brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CGAS=Children’s Global Assessment Scale; CGI-I=Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale; CGI-S=Clinical Global Impressions-Severity scale; CLAM=Conners, Loney and Milich rating scale; COMT=catechol-O-methyltransferase; DA=dopamine; DBH=dopamine beta-hydroxylase; DRD1=dopamine receptor D1; DRD2=dopamine receptor D2; DRD3=dopamine receptor D3; DRD4=dopamine receptor D4; GRIN2B=N-methyl-D-aspartate type subunit 2B; GRM7=glutamate metabotropic receptor 7; K-ARS=Korean ADHD Rating Scale; MAOA=monoamine oxidase A; NTF3=neurotrophin 3; PERMP=Permanent Product Measure of Performance; RAST=Restricted Academic Situations Task; SKAMP=Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham Scale; SLC6A2=norepinephrine transporter; SLC6A3=dopamine transporter; SLC6A4=serotonin transporter; SNAP=Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire; SNAP25=synaptosome associated protein 25; TH=tyrosine hydroxylase; TPH2=tryptophan hydroxylase 2; TOVA=Test of Variables of Attention; VNTR=variable number tandem repeat

Neurotransmitter Synthesis and Degradation

Several proteins are involved in the synthesis, processing and delivery of the neurotransmitters DA, NE and 5-HT to the synaptic cleft and have been studied as a factors of MPH response.

Tyrosine hydroxylase

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is the rate limiting enzyme for DA synthesis, facilitating the conversion of tyrosine to the DA precursor, L-3,4-dihyroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) [56]. MPH may induce expression of TH [57] and increase levels of TH [58]. An in-vitro study showed that TH activity was statistically significantly increased with D-MPH above a concentration of 100 nmol/l, but not with L-MPH or racemic MPH at the same concentrations (P< 0.001) [59]. In comparison, a 0.75 mg/kg dose of MPH produced plasma concentrations in the range of 20 to 37 nM in mice one-hour post dose; however, brain concentrations were below the limit of detection [60]. In ADHD children, a mean dose of osmotic pressure delivery system-MPH (OROS-MPH) 0.7 mg/kg of MPH resulted in an average plasma concentration of 42.5 nM racemic MPH [61]. Examined studies revealed only one TH polymorphism studied as a factor of MPH response. Including Clinical Global Impressions-Severity scale (CGI-S) baseline scores as a covariate, subjects with the C/C genotype of rs2070762 who started with lower CGI-S scores than carriers of the T allele had poorer response to MPH (OR: 4.34, Cl:1.54 – 12.2, P = 0.0055) [62]. Current data suggest an effect of TH on MPH response, although further studies are needed to support this effect.

Tryptophan hydroxylase

Tryptophan hydroxylase exists as two isoforms, TPH1 and TPH2, and catalyzes the rate limiting step in the synthesis of 5-HT, converting tryptophan to the 5-HT precursor, 5-hydroxytryptophan. TPH1 had previously been studied in ADHD association studies [63, 64] until TPH2 was implicated as the sole isoform expressed in the brain [65]. Two studies have examined TPH2 as a factor of MPH response. Contini et al. did not find an association for either rs1843809 or rs4570625 in adult individuals [66]. Manor et al. tested for eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) unique from those studied by Contini et al.; rs1386488, rs2220330, rs1386495, rs1386494, rs6582072, rs1386492, rs4760814, and rs1386497. The tested SNPs were all in strong linkage disequilibrium with each other forming five haplotypes. The most common haplotypes, ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’, displayed complementary patterns of alleles, AATGGAGA and CGCAAGAC respectively. When analyzed with the continuous performance test (TOVA), individuals with the ‘Yang’ haplotype had significant improvement in scores compared to ‘Yin’ haplotype individuals after MPH administration (P = 0.009), suggesting improved MPH response in individuals with the ‘Yang’ haplotype [67].

Dopamine beta-hydroxylase

Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) is responsible for converting DA to NE [68], DBH has been examined as an effector of MPH response. Contini et al. found no association between rs1611115 and MPH response [66]. Pagerols et al. did not examine this variant but found an effect with two other SNPs: rs1541332 and rs2073833. Carriers of the TC haplotype of the aforementioned SNPs showed an increased frequency of treatment failure via the CGI-S (OR: 4.58, Cl: 1.32 – 15.9, P = 0.011). The same effect was observed with nominal significance for the C/C genotype of rs2073833 alone (OR: 6.25, Cl: 0.78 – 50, P = 0.030). Subjects with the AGC haplotype of rs2007153, rs2797853 and rs77905 were found to be 61.9% less likely to experience any adverse events (P = 0.02), which was strengthened when adjusting for comorbid conditions (OR: 0.28, Cl: 0.11 – 0.70, P = 0.0064) [62].

Monoaomine oxidase

The monoamine oxidase family of enzymes includes monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) and monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), both of which are located on the outer mitochondrial membrane. MAOB primarily degrades DA while MAOA breaks down a wider array of compounds including DA, NE, 5-HT and tyramine [69]. Guimarães et al. examined the effects of the 30-bp promoter-region variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) of MAOA on MPH-response with the Swanson, Nolan and Pelham Rating Scale version IV (SNAP-IV) oppositional score as the primary outcome. During 3 months of treatment, individuals with the 4-repeat allele had improved oppositional scores compared to individuals with the 3-repeat allele (P = 0.009) [70]. Manor et al. found a significant association in male ADHD subjects with longer repeats (4 and 5) of the VNTR of MAOA and increase in impulsivity via TOVA (P = 0.008). After administration with MPH this difference was no longer significant, suggesting improved response in individuals with longer repeats [71]. McCracken et al. examined the effects of MAOA variants rs1465108, rs3810709 and rs3027399 and MAOB variants rs10521432 and rs1799836 on MPH administration with no effect observed [72]. An in vitro study found MAOB enzyme activity to be increased between 94 and 220% at MPH concentrations from 1 nM to 10 μM with either l-threo or d-threo MPH (p < 0.01) [59]. These two studies indicate a potential relationship between MAOA/MAOB and their respective genes and MPH response, particularly with the 30-bp VNTR of MAOA; however, more studies are needed to confirm this association.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is responsible for the degradation of DA and NE [73], and therefore COMT has been targeted as a potential impactor of MPH response. The most common allelic variant studied, 472G>A (rs4680), is most often referred to by the protein substitution, Val158Met. The A allele (Met) results in about 25% of the protein activity compared to the wild type G allele (Val) [74] and has been associated with impaired structural maturation of brain white matter connectivity in children with ADHD. In fourteen studies examining the effect of 472G>A on MPH response, only three studies [75–77] found statistically significant or near statistically significant associations between improved response to MPH and the Val allele [62, 66, 78–86]. Kereszturi et al. determined the G/G genotype was present twice as frequent in the responder group compared to the non-responder group according to both the ADHD-RS and CGI-S (P = 0.034) [75]. Cheon et al. presented a similar outcome in their study, where 62.5% of subjects with a good response to MPH had the G/G genotype while 41.7% and 11.7% of subjects with a poor response had the G/A and A/A genotypes, respectively, according to the Korean version of the ADHD-RS (K-ARS) (P = 0.035) [76]. Notably, two of these studies were carried out within specific population subsets, post traumatic brain injury [82] and Velocardiofacial Syndrome [81], making it difficult to analyze MPH response in individuals with comorbid conditions. Based on re-analyzed data from seven studies [67, 76, 77, 79, 80, 83, 84], a recent meta-analysis reported an association of the G/G genotype with improved treatment response compared to A allele presence (OR:1.40, Cl: 1.04–1.87, P=0.02) [87]. A few studies found associations between Val158Met genotypes and MPH side effects: worsened sleep continuity for G carriers (P < 0.05) [88] increased irritability for G/G genotype (P = 0.02) [77], and a higher rate of sadness for the G allele in a population of individuals also having Velocardiofacial Syndrome (P < 0.05) [81].

Neurotransmitter Reuptake

Dopamine transporter

Pharmacogenetic studies of SLC6A3 polymorphisms have almost exclusively focused on the 40-bp VNTR (rs28363170) within the 3’ untranslated region of the gene. The VNTR consists of between 3 to 11 repeats and is most commonly expressed as either 9 (9R) or 10 repeats (10R). Numerous studies examine the effects of the VNTR on response to MPH. Kambeitz et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 16 articles examining the VNTR and concluded no clear association between either the 9R or 10R allele and response to MPH across twelve different rating scales. However, when only naturalistic trials were analyzed there was a significant association between 10R homozygotes and decreased response (P = 0.03) [89]. Studies not included in the meta-analysis by Kambeitz et al. have yielded similarly conflicting results. Froehlich et al. found individuals without the 10R allele had improved hyperactive-impulsive scores on the Vanderbilt ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scales (P = 0.008) [80], while Stein et al. found 9R homozygotes had decreased response at higher doses of MPH via the ADHD-RS (P = 0.012) [90]. Furthermore, in an open label trial, Pasini et al. determined 10R homozygotes had increased response of improvements in working memory via the N-Back Test (P = 0.002) [91]. Four other studies found no effect of the SLC6A3 VNTR with MPH response [62, 86, 92, 93]. A recent meta-analysis by Myer et al. included 16 studies with an overlap of 11 studies compared to the meta-analysis described above. Based on the transformed data from these 16 studies, Myer et al. reported a significant association for the homozygous 10R genotype with reduced efficacy (OR: 0.74, Cl: 0.60–0.90, P=0.004) [87]. After adjusting for publication bias, the association remained significant. Large variability in populations and methodology examining the 40-bp VNTR may contribute to the differences in results among the discussed studies. One study included in both meta-analyses also examined three other SNPs within SLC6A3 rs2652510, rs2550956 and rs11564750, although no effect was found for any of these variants [94]. Gomez-Sanchez et al. studied rs11564750, in addition to a 30-bp VNTR within intron 8, rs2550948 and rs2652511 in SLC6A3. They found the G allele of rs2550948 to be associated with increased response to MPH assessed via the CGI-S (P = 0.011) [86]. The variability in methodology and results observed in the reviewed studies makes it difficult to clearly explain the relationship between MPH response and genetic variation in SLC6A3.

Norepinephrine transporter

Pharmacogenetic studies of SLC6A2 variants and MPH administration suggest the SNP −3081A>T (rs28386840) may be a significant contributor. Individuals with the genotype, A/A, of −3081A>T have been associated with decreased response to MPH in several studies: via TOVA (P = 0.003) [95], ADHD-RS (P = 0.02) [92], and Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale (CGI-I) (P = 0.03) [96]. Angyal et al. described an association of increased response for carriers of least one T-allele using ADHD-RS scores, however, the association was not statically significant (P=0.08) [97]. A meta-analysis by Myer et al. included data from three of the four studies [92, 95, 96] and reported an association of the T allele with improved response to MPH compared to the A/A genotype (OR: 2.93, Cl: 1.76–4.90, P<0.0001) [87]. On the other hand, Gomez-Sanchez et al. and Kim et al. did not observe this association [86, 98]. In the four studies demonstrating a positive association, all were carried out in Korean patients and all but one were blinded dose-response studies. In contrast, Gomez-Sanchez et al. was an observational study conducted in a Caucasian/Spanish population and Kim et al. was an open-label study of Korean subjects.

The G allele of 1287G>A (rs5569) is associated with improved response to MPH in numerous studies. This association was noted with the G/G genotype via TOVA (P = 0.006) [95], with at least one copy of the G allele via the ADHD-RS – hyperactive-impulsive subscale (P = 0.012) [99] and with the G/G genotype via the ADHD-RS and CGI-S (P = 0.008) [100]. Numerous studies have not supported this association [77, 86, 92, 96–98, 101]. A re-analysis of seven studies [77, 92, 95, 96, 99–101] in the meta-analysis by Myer et al. reported an association of the G/G genotype of the rs5569 variant with improved MPH response compared to the A allele carriers (OR: 1.73, Cl: 1.26–2.37, P=0.0007) [87]. Cho et al. studied the effects of both −3081A>T and 1287G>A on blood-pressure and heart rate in children taking MPH and found the T/T genotype of −3081A>T to be associated with increased heart rate (HR) (P = 0.01) [102]. Other polymorphisms studied included the 4-bp insert in the promoter region (NETpPR) [103], rs2242446, rs5568, rs998424, rs1610905, rs3785157, rs3785143, and rs7194256 [97, 101]. No association has been observed with any of these polymorphisms.

Serotonin transporter

As previously noted, MPH has low affinity for SLC6A4, and therefore pharmacogenetic variants in SLC6A4 would not necessarily be expected to significantly impact medication response. The commonly studied polymorphism within SLC6A4 is the deletion, short ‘S’, or insertion, long ‘L’, variant of the serotonin-transporter-linked polymorphic region (5HTTLPR) within the promoter region of SLC6A4. Of nine studies identified that examined the effects of 5HTTLPR and MPH response, only two found statistically significant associations between 5HTTLPR and MPH response. Seeger et al. found a decrease in symptom improvement according to the Childrens’ Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) for individuals who expressed the L/L genotype of 5HTTLPR and were also carriers of the 7R allele of the dopamine receptor D4 gene (DRD4) when compared to all other combinations of alleles within those polymorphisms except for the DRD4 7R/5HTTLPR S/S allelic combination (P = 0.001) [104]. McGough et al. found at higher doses, carriers of the L allele had lower scores on the Permanent Product Measure of Performance (PERMP) math test (P = 0.02), but no association with response when evaluated by the ADHD-RS. This study also found an association between the 5HTLPR L/L genotype and decreased vegetative symptoms (sleep problems and appetite loss) (P = 0.003) [77]. No other studies found any statistically significant association between 5HTTLPR and MPH response [66, 72, 86, 105–108]. Tharoor et al. specifically examined the relationship between the DRD4 7R/5HTTLPR combination and MPH response, finding no statistical significance [106]. Park et al. found individuals expressing genotypes of either S/L or L/L were associated with increased incidence in nail biting during MPH treatment (P = 0.017) and increase or aggravation of tics (P < 0.001) [108]. The VNTR of intron 2 contains a 17-bp unit repeated either 7, 9, 10, or 12 times. McGough et al. determined individuals lacking any copy of the 12-repeat allele of the intron 2 VNTR had less symptom improvement via the ADHD-RS as compared to individuals with at least one copy (P = 0.01) [77]. Conversely, McCracken et al. showed individuals homozygous for the 12-repeat allele had worse MPH response rates compared to other individuals via the CGI-I and Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC)- hyperactivity subscale, 39% to 67% respectively (P = 0.041). This study also examined several other variants rs12150214, rs4251417, and rs11080121, although none exhibited an association with MPH response [72]. Gomez-Sanchez et al. also analyzed the VNTR within intron 2 and found no association with response [86].

Neurotransmitter Receptor Binding

Dopamine receptors

Research regarding the downstream effects of MPH as a SLC6A3 blocker is complicated by the numerous DA receptors. There are five different DA receptors between two subfamilies, dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1)-like receptors and dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2)-like receptors. DRD1-like receptors include DRD1 and dopamine receptor D5 (DRD5); DRD2-like receptors include DRD2, dopamine receptor D3 (DRD3) and DRD4 [109]. DRD1-like receptors mediate excitatory neurotransmission by increasing the probability of producing an action potential, while DRD2-like receptors mediate inhibitory neurotransmission by decreasing the probability of producing an action potential. DRD2-like receptors are present as both downstream postsynaptic receptors and presynaptic feedback auto-receptors. DRD2 predominates as the primary mediator of presynaptic auto-receptor signaling, while other DRD2-like receptors have been suggested to play minor roles as presynaptic auto-receptors [110]. The effects of presynaptic DRD2 stimulation is not clearly defined as discussed further in the text. MPH has no measurable affinity for DA receptors [35], but rather exerts its effects on DA receptors indirectly through increased DA concentrations in the synaptic cleft through SLC6A3 inhibition. The results of studies examining MPH induced DA receptor activation is further complicated by which region of brain is studied [53, 111–115]. Carey et al. notes that the same DA receptor can be differentially distributed or regulated in different areas of the brain, presumably due to changes in post-synaptic DA concentrations [116]. Studies examining the effects of MPH on changes in DA receptor concentrations or mRNA expression have similarly yielded differing results dependent upon the region of the brain studied [117–121].

Current research indicates all five DA receptors may play a role in MPH’s effects on increased extracellular DA concentrations; however, the effects are primarily mediated through DRD1 and DRD2. Indirect activation of postsynaptic DRD2 due to MPH-mediated higher DA concertation in the synaptic cleft has been observed in animal studies [122–128] and confirmed in human studies [53, 123, 129, 130]. This activation leads to the coupling of prefrontal cortex (PFC) and DA cells contributing to synaptic plasticity [131]. MPH also exhibits its effects through indirect activation of DRD1 [127, 132, 133]. This activation enhances cognitive function [134] through PFC neurons [135–137] and induction of long term potentiation (LTP) [138]. Interestingly, DRD1 has been implicated as a player in antinociception [139] and induction of cortical acetylcholine release [140]. These effects may contribute to the rewarding effects of MPH linked to DRD1/DRD2 receptor activation [125, 141–144]. Venkataraman et al. highlights the difference between DRD1 and DRD2 as excitatory and inhibitory receptors respectively. In rats given MPH, there was an increase in DRD1 activity and neuronal firing rate in rats classified as MPH responders. Conversely, there was increased post-synaptic DRD2 activity and decreased neuronal firing in rats classified as MPH non-responders [145]. The results of this study suggest expression or regulation of DA receptors may influence the effectiveness of MPH, specifically higher concentrations or expression of excitatory DA receptors, DRD1 and DRD5, may result in increased response to MPH. The activation of presynaptic DRD2 after MPH administration may induce redistribution of membrane vesicles resulting in increased DA release [146]; however, it has also been suggested this activation leads to decreased DA release through feedback inhibition [147, 148].

MPH has been shown to illicit various other effects through indirect activation of DA receptors in animal studies. Like DRD1, DRD5 also plays a role in MPH induced cognitive enhancement through induction of LTP [138]. Indirect MPH activation of DRD1 and DRD5 in mice induces the consolidation of extinction memory, which is defined as the learned inhibition of retrieval or the gradual loss of a conditioned response and is a common therapy used to treat drug addiction, phobias and fear disorders [149]. DRD2, DRD3 and DRD4 receptors have been linked to MPH induced impulsivity [112, 150]. DRD4 plays a role in the modulation of PFC and cerebellar vermis (CBV) functioning [151] and is associated with the positive reinforcing property of MPH [152]. The positive reinforcing property of MPH can be defined as increased utilization associated with rewarding stimuli, or more simply “wanting” and “liking” [153]. DRD3 receptors have been shown to decrease the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) upon MPH administration resulting in reduced PFC plasticity. While MPH cannot be assumed to elicit these effects in humans without correlative studies, these associations highlight the complexity of the effects of MPH induced increases in extracellular DA concentrations.

Pharmacogenetic studies of DA receptors have primarily focused on the 48-bp VNTR located within exon 3 of DRD4. The VNTR includes between two and eleven repeats with four and seven repeats being the most common (4R and 7R). The association between the VNTR and MPH response has been examined in several studies. Cheon et al. observed that among MPH responders, 71% and 80% of the individuals were homozygous for the 4R allele while only 31–37% of non-responders were homozygous for the 4R allele as measured via the ADHD-RS parent and teacher scores respectively (p < 0.01) [154]. Froehlich et al. similarly found individuals lacking a copy of the 4R allele had decreased improvement in hyperactive-impulsive scores via the Vanderbilt ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scales (P = 0.02) [80]. In a dose titration study, participants with the 7R allele required 1.0 mg/kg to achieve response via the Conners’ Global Index-Parent as compared to 0.49 mg/kg for those without the 7R allele (P = 0.002) [155]. Seeger et al. also determined the 7R allele was a risk factor for decreased response measured by the CGAS, but only when coupled with the L/L genotype of the 5HTTLPR within the promoter region of SLC6A4 (P = 0.001) [104]. Conversely, Tahir et al. reported an increased rate of medication response and transmission of 7R from parent to child via the Transmission Disequilibrium test (TDT) compared to non-responders (P = 0.049) [156]. Notably, all other studies concerning the VNTR within DRD4 have yielded non-significant associations with MPH response [62, 66, 75, 77, 86, 92, 93, 103, 105, 106, 157–160]. In addition to most studies investigating the DRD4 VNTR finding a non-significant association with MPH response, the positive associations discussed present specific findings that do not support a strong association. Froehlich et al. only noted an association via hyperactive-impulsive scores, the association observed in Seeger et al. only occurred when the DRD4 VNTR genotype was coupled with the L/L genotype of the 5HTTLPR, and Tahir et al.’s findings were based on the TDT and not a direct measurement of medication response. A meta-analysis investigated the DRD4 48bp VNTR as 4R allele vs others alleles and 7R allele vs others [87]. Homozygous presence of the 4R variant was associated with improved response to MPH based on data of the six included studies (OR: 1.66, Cl: 1.16–2.37, P=0.004). The comparison of the 7R variant vs others did not result in a statistically significant association (OR: 0.68, Cl: 0.47–1.00, P=0.05; based on five studies) [87]. Another variant studied within DRD4 is the 120-bp promoter duplication located 1.2 kb upstream. This variant presents as either 120-bp (short, S) or repeated as 240-bp (long, L). In two studies, this duplication was found to not be associated with MPH response [77, 103]. Gomez-Sanchez et al. however noted a significant association between individuals homozygous for the short allele, S/S, and impaired response to MPH via the CGAS and CGI-S (P = 0.001) [86]. Another study supported this association and observed subjects homozygous for the long allele, L/L, responded better to MPH treatment, although this association was measured via the composite scores of the lesser-utilized Teacher Conners, Loney and Milich (CLAM) and Swanson, Conners, Milich and Pelham (SKAMP) Scales (P = 0.05) [161]. Other DRD4 polymorphisms studied include rs3758653, in which no association has been observed [72, 86], and rs11246226, with the A/A genotype associated with increased response scored using the CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale (P = 0.038) [72].

Multiple other variants within the other DA receptor genes have been studied, although there are not widespread results to suggest a significant association. McCracken et al. examined 19 polymorphisms within the other DA receptors and observed a nominally significant association with three variants according to the CGI-I and ABC-hyperactivity subscale. Within DRD1, individuals carrying at least one G allele for rs4867798 responded to MPH at a higher rate (P = 0.042) and individuals carrying at least one A allele for rs5326 also had improved response rate (P = 0.006). Additionally, children with autism spectrum disorder with the A/A genotype of rs6280 within DRD3 had a higher response rate (P = 0.044) [72]. Individuals homozygous for the A2 allele, of the Taq1A polymorphism (rs1800497, A2>A1) ate significantly less food compared to others (P = 0.007), implying an increased risk for appetite suppression [159]. No association with medication response was observed for this polymorphism [86, 157]. The Taq1A polymorphism is located ~10 kb downstream of DRD2 within ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (ANKK1) but has been associated with altered functionality of DRD2 [162]. Analyzing multiple polymorphisms within the five DA receptors, Pagerols et al. only noted an association with two genes and response to MPH. The first association observed was with the allelic combination of rs2134655 and rs1800828 of DRD3. Subjects who carried at least one copy of the G allele for both SNPs were at a higher risk for treatment failure via the CGI-I (P = 0.041). When considering MPH dose as a covariate, they noted carriers of the T allele of rs2283265 within DRD2 were at an increased risk of experiencing any adverse effect (P = 0.047) [62].

Alpha-2A adrenergic receptor

The alpha-2A adrenergic receptor (ADRA2A) is stimulated by NE as post-synaptic receptor and acts as a negative feedback inhibitor through auto-receptors on the presynaptic neuron [163]. MPH increases the activity of alpha adrenoreceptors in rats, presumably through the indirect increase in NE mediated by the SLC6A2 blockade [164]. This association has been supported in subsequent animal studies, specifically through ADRA2A [136, 165, 166]. The indirect stimulation of ADRA2A has been shown to increase PFC cognitive function in monkeys [135] and subsequent studies have supported these findings by demonstrating that MPH induced activation of ADRA2A improves cognitive function [134] and PFC working memory performance [167]. Despite a lack of human studies on MPH-induced changes in NE and ADRA2A interactions, there are multiple studies investigating the pharmacogenetic influence of ADRA2A variation on MPH response.

Pharmacogenetic studies of adrenergic receptors have focused primarily on the MspI (−1291C>G, rs1800544) and DraI (rs553668) variants within ADRA2A. In four studies examining the association between DraI and MPH, none found a significant association with overall response [92, 98, 168, 169]. Results from studies concerning MspI are varied. Cheon et al. found 76.9% subjects with the G/G genotype of −1291C>G were responders according to the ADHD-RS parent score compared to 46% and 41.7% of C/G and C/C genotypes respectively (P = 0.003) [170]. Da Silva et al. and Polanczyk et al. both examined −1291C>G using the SNAP-IV scale. Presence of at least one G allele was associated with decreased inattentive scores during the first month (P = 0.016) and 3 months of treatment respectively (P = 0.02) [171, 172]. Three studies observed a trend for association between the G allele and improved response to MPH but without statistical significance [93, 169, 173], and no effect was observed in four other studies [80, 86, 92, 168]. A meta-analysis by Myer et al. included data from four studies [80, 98, 171, 172] and reported an association of the G allele of rs1800544 with improved MPH response compared to the C allele (OR: 1.69, Cl: 1.12–2.55, P=0.01) [87]. Two additional SNPs within ADRA2A, rs1800545 and rs553668, were found to be in linkage disequilibrium with MspI but were not associated with response to MPH [86, 173]. Cho et al. found individuals with the C/C genotype of MspI averaged an 18% increase in diastolic blood pressure readings after MPH administration, while individuals with either G/C or G/G genotypes averaged a 0.2% decrease in diastolic blood pressure (P = 0.009). No effect on blood pressure were observed for DraI [102]. Variability in the observed results could be attributed to multiple factors, most notably that the studies examining the effects of the MspI polymorphism on response to MPH differed in the study populations and the administered rating scales (including the ADHD-RS, SNAP-IV, CGI, and CGAS).

Serotonin receptors

Investigation into the effects of the serotonergic system on MPH response has not supported a strong association. In vitro, MPH has been shown to bind directly to the 5-HT receptors, 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A (HTR1A) and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B (HTR2B) [33], but not the at any of the receptors in the subfamily of 5-HT receptor 3 (in vivo rat study) [174]. As discussed previously, MPH has minimal affinity for SLC6A4 and binds at clinically insignificant levels [35, 41]. Subsequent animal studies have found MPH acts as an agonist at HTR1A [175] and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1B (HTR1B) [176], but no activity at HTR2B [175], although no human studies have confirmed these associations. From a pharmacogenetic view, no tested polymorphisms within the serotonergic receptor genes HTR2A, HTR1B or HTR2C were associated with MPH response [66, 86, 105].

Neurotransmitter Processing and Release

Vesicular monoamine transporter

Solute carrier family 18 member 2 (SLC18A2), also known as vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), participates in transporting monoamines from the cytosol into synaptic vesicles [177]. Sandoval et al. first reported the effect of MPH on SLC18A2. In vivo experiments in rats demonstrated MPH administration quickly and reversibly increase vesicular uptake of DA into packaging vesicles. The study suggested MPH may play a role in the redistribution of SLC18A2 from the plasmalemmal membrane to the cytoplasmic, non-membrane associated subcellular pool, as well as in increasing the protein expression of SLC18A2 [178]. The MPH-induced vesicular uptake of DA and the suggested role of MPH in the redistribution of SLC18A2 from the plasmalemmal membrane to the cytoplasmic, non-membrane associated subc0ellular pool has since been supported in numerous animal studies [146, 179–182], including at 2 mg/kg subcutaneous injection in rats [183]. The redistribution away from the plasma membrane may be a function to promote the sequestration of DA into the synaptic vesicles [183].

Synaptosome associated protein 25

Synaptosome associated protein 25 (SNAP25) constitutes part of the Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor (SNARE) protein complex. SNAP25 plays a vital role in the docking and fusion of synaptic vesicles on the cytosolic side of the neuronal membrane carrying neurotransmitters including DA and NE [184]. After 30 days of MPH administration in juvenile rats, there was a significant decrease in SNAP25 protein levels (< 0.05) [185]. Pharmacogenetic studies of SNAP25 and MPH have yielded mixed results. In three studies there were no primary associations between 1065T>G (rs3746544), 1069T>C (rs1051312) or rs363020 and MPH response [66, 77, 161]. However, Song et al. and Gomez-Sanchez et al. found the T/T genotype of 1065T>G was associated with improved and decreased response to MPH on the ADHD-RS (P = 0.034) and CGI-S (P = 0.018) respectively [86, 186]. McGough et al. also analyzed side effects to MPH treatment. The G allele of 1065T>G resulted in decreased risk of irritability (OR: 0.35, CI: 0.13 – 0.97, P = 0.04) and the C allele of 1069T>C resulted in decreased risk of motor tics (OR: 0.27, CI: 0.09 – 0.83, P = 0.02), buccal-lingual movements (OR: 0.27, CI: 0.09 – 0.77, P = 0.01) and picking/biting (OR: 0.38, CI: 0.14 – 1.01, P = 0.05) [161]. The current data on SNAP25 provides evidence of an association with MPH but the strength of the relationship between identified polymorphisms and MPH treatment remains unclear.

Neuronal/Synaptic Plasticity and Synaptic Effectors

Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3

Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 (ADGRL3), is a G-protein coupled receptor of the latrophilin subfamily. Latrophilin proteins play a role in synaptic development and regulation [187], development of dopaminergic circuitry [188] and the regulation of neurotransmitter exocytosis in the brain, including NE [189, 190]. Two studies examined the effects of the same six SNPs within ADGRL3 rs1868790, rs1947274, rs2122643, rs2345039, rs6551665 and rs6858066 on MPH treatment response with differing results [191, 192]. Choudry et al. noted the AAG haplotype of rs6551665, rs1947274, and rs6858066 was associated with decreased response to MPH via the CGI-I while the GCA haplotype was associated with increased response [191]. In contrast, Labbe et al. found the G allele of rs6551665 and the C allele of rs1947274 were both associated with MPH non-responders according to the Restricted Academic Situation Scale Task (RAST) (P = 0.005). They also found the G allele of rs6858066 and the G allele of rs2345039 to be associated with increased (P = 0.006) and decreased response (P = 0.0002) respectively [192]. Song et al. determined there was no association with MPH treatment and the variants rs6551665, rs2345039, rs1947274 according to both the CGI-I and K-ARS [186]. Among these three studies, a different scale was used in each to measure MPH response which could contribute to the variation in observed results. Another study examined the effects of haplotype combinations via the SNAP-IV scale. They determined the CGC combination of SNPs rs6813183, rs1355368 and rs734644 was associated with improved response (p < 0.001) to MPH while the GT haplotype of rs6551665 and rs1947275 fell short of significance after Bonferroni correction (P = 0.03) [193]. Gomez-Sanchez et al. found subjects with the A/A genotype of rs1868790 was associated with decreased response to MPH via the CGI-S (P = 0.026) which was not previously reported. No other variation (rs1397548, rs2305339, rs6551665, rs6813183, rs6858066) in this study were associated with response to MPH [86]. Arcos-Burgos et al. similarly analyzed the effects of ADGRL3 SNPs on stimulant treatment but did not differentiate between treatment with MPH and other stimulants [194]. A meta-analysis showed no significant association with MPH response for rs6551665 (OR: 1.07, Cl: 0.84–1.37, P=0.59) and rs1947274 (OR: 0.95, Cl: 0.71–1.26, P=0.70) [87]. These results suggest there may be an effect of ADGRL3 genotype on MPH treatment but there does not appear to be a consistent trend.

Neurotrophin factors

The neurotrophin family of proteins aid in regulating neuronal plasticity through involvement in neuronal growth, differentiation, maturation and survival. BDNF and neurotrophin 3 (NTF3) are members of this family that have been studied for an association with MPH. BDNF specifically plays a role in the neuroplasticity of dopaminergic neurons [195]. Animal studies initially reported decreased BDNF expression [196] and decreased BDNF levels [197] upon MPH administration in rats while another study found BDNF levels increased by 50.4% in males and decreased by 42% in females after MPH administration [198]. Subsequent animal studies have demonstrated mostly increases in BDNF levels [199–201] and BDNF expression [57, 202] upon MPH administration. However, decreased BDNF levels [185, 202] and activity [203, 204] have also been reported. Studies in children with ADHD have shown MPH administration has led to a reduction in BDNF levels (P = 0.048) [205, 206], however the latter was conducted in predominantly inattentive type ADHD subjects (P = 0.025). Another study examining the effects of MPH on BDNF found an increase in serum BDNF levels in the predominantly inattentive group (P = 0.005) [207]. Amiri et al. similarly found an increase in serum BDNF levels in ADHD patients treated with MPH and, in addition, a negative correlation between BDNF plasma levels and improvement in hyperactivity symptoms after treatment via Conner’s Parent Rating Scale (Pearson’s correlation = −0.395, P = 0.037), indicating improved treatment response with decreasing plasma BDNF levels [208]. Only one pharmacogenetic study has examined the effects of BDNF on MPH response. Kim et al. determined individuals with G/G genotype of the rs6265 variant had significantly improved response to MPH via the CGI-S upon Bonferroni-correction (P = 0.0002) [209]. The results presented provide differing associations between MPH and BDNF, clouding the exact effect and clinical significance of the association.

NTF3 is a neurotrophic factor that has been shown to play a role in proliferation, differentiation and survival of neurons [210, 211]. NTF3 has been suggested to enhance the myelination of oligodendrocytes [212], specifically through direct action on protein translation [213]. Park et al. studied the effects of two NTF3 SNPs, rs6332 and rs1805149, on MPH administration. They demonstrated individuals with the A/A genotype of rs6332 were at increased risk of experiencing emotionality (P = 0.042), over-focus/euphoria (P = 0.045), proneness to crying (P = 0.047) and nail-biting (P = 0.017) as side effects of MPH. No effect was observed for rs1805149 [214].

Glutamate receptors

The glutamate metabotropic receptor 7 (GRM7) belongs to the mGluR family of receptors and acts as a presynaptic regulator of neurotransmission through its primary role in the control of excitatory synapse function [215]. GRM7 was included in a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of response to MPH, and while it did not meet the threshold for GWAS significance, the GRM7 SNP rs3792452 was implicated as a potentially impactful polymorphism (P = 2.6 × 10−5) [216]. Korean subjects heterozygous for rs3792452 polymorphism, G/A, had a better response than those with the genotype G/G after 8 weeks of treatment with MPH. These results were consistent on both the ADHD-RS parent version (72.2% vs 55.4% response rate respectively, P = 0.011) and CGI-I scores (50.0% vs 35.3% response rate respectively, P = 0.044) [217]. Gomez-Sanchez et al. however found no association with this variant in a Caucasian population utilizing the CGI-S and CGAS [86].

MPH has also been linked to the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor. Animal studies have shown MPH potentiates the effects of the NMDA receptor excitatory post-synaptic current [137, 218–220] and MPH may decrease protein levels of glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 1 (GRIN1) and glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B (GRIN2B), but not glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2A (GRIN2A) [221]. Kim et al. studied the association between MPH response in humans and the GRIN2B variant rs2284411 and the GRIN2A variant rs2229193. They demonstrated the C/C genotype of GRIN2B rs2284411was associated with improved treatment response based on the ADHD-RS inattentive score (P = 0.009) and CGI-I (P = 0.009), but only with nominal significance on the ADHD-RS total score [222]. These studies do not provide robust data to confirm an association between NMDA receptors and MPH, but it does appear some of MPH’s effects may be mediated through the receptor subtypes.

Apart from ADGRL3, there is minimal data depicting a clear picture of how these synaptic effectors may alter response to MPH.

Downstream Neurotransmitter Effects

The indirect activation of DA receptors results in various changes in downstream signaling. Downstream effectors of DA receptor activation include protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 1B (PPP1R1B), AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (AKT1), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) release and neuronal calcium sensor 1 (NCS1), as well as changes in acetylcholine transmission. PPP1R1B, also known as dopamine- and cAMP-regulated neuronal phosphoprotein (DARPP-32), has been implicated to play a role in the regulation of post-synaptic signaling [223] and it has been suggested MPH may affect PPP1R1B expression [224] and phosphorylation [132]. In PPP1R1B knockout mice MPH-induced DA activation has led to restoration of behavioral deficits [225]. In mice, Akt1 plays a role in neuronal survival and is regulated by changes in DA signaling [226]. AKT1 contains a VNTR within intron 3 with either eight repeats (L) or nine repeats (H). Following intravenous MPH administration in humans, DRD2 availability was enhanced in L/L individuals compared to H/H individuals (p < 0.002) and increased DA release was observed in individuals with the H allele; H/H > H/L > L/L (P = 0.009) [227]. This study presents novel data suggesting indirect DA induced dephosphorylation of AKT1 may alter upstream DA concentrations following stimulant administration. In animal studies GABA release is associated with MPH induced activation of DRD4 [228] and has been implicated to play a role in response to MPH [229–231]. In humans, when started at a young age, chronic MPH treatment has been suggested to increase GABA levels resulting in long-term down-regulation of endogenous GABA levels. These results suggest chronic MPH administration early in development may alter brain development, specifically related to the GABAergic system [232]. MPH has been shown to alter expression of NCS1, which plays a role in DRD2 internalization [233] and induction of cortical acetylcholine release through indirect DRD1 stimulation [140]. Based on the current evidence, it is clear MPH exerts changes to the DA signaling cascade; however, the complexity of downstream effectors and the lack of correlative human studies makes it difficult to illustrate the significance of these changes.

Conclusion

CES1 is the primary enzyme responsible for metabolism of MPH to the inactive metabolite RA. Current research suggests the G143E variant (rs71647871) of CES1 may result in decreased metabolism of MPH and therefore increased exposure to MPH.

Determining the significance of the role a protein or gene may play in the pharmacodynamic effects of MPH is complicated by multiple factors. Analyzing the downstream effects of the MPH-blockade of SLC6A3 and SLC6A2 and the resulting increase in DA and NE becomes difficult as the concentrations of SLC6A3, SLC6A2 and downstream effectors differs in different regions of the brain. Further, the receptors the neurotransmitters bind to can be either stimulatory or inhibitory, can act as both downstream effectors and as autoregulators, and can be differentially expressed in different regions of the brain. Besides of the direct effects at increasing DA and NE levels, the neurotransmitters must be synthesized, packaged, delivered and released in to the synaptic cleft and can also be degraded before exerting their effects. After binding to their respective receptors, there are many downstream effectors that can alter the received signal.

Epigenetic alterations and environmental factors are additional variables to be explored, as a recent article examined the effects of SLC6A3 and DRD4 methylation on MPH response [234]. While no significant association was observed, for each gene associated with MPH regulation of that gene’s expression may play a role in the effectiveness of MPH. Environmental factors can affect a subject’s response to MPH. Specifically, Pagerols et al. noted individuals that were exposed to prenatal smoking were significantly less likely to respond to MPH (OR: 5.10, Cl: 1.76 – 14.8) [62].

The determination of MPH efficacy is challenging because no universally accepted means of measuring response exists. In humans, measuring the effectiveness of MPH is most often done using rating scales; however, there are multiple rating scales including Conners, ADHD-RS, SNAP-IV, Vanderbilt ADHD Parent and Teacher Rating Scales, and CGI scales. Furthermore, the scales are scored differently for parents compared to a teacher, or the results can be analyzed by subtype of ADHD symptoms; inattention, impulsivity, hyperactivity. Hong et al. perhaps best highlights the complexity of MPH pharmacodynamics and how research regarding the effect a protein or gene plays in the response to the drug should be analyzed. In their study, polymorphisms within SLC6A3, DRD4, ADRA2A and SLC6A2 were analyzed for association with MPH response. After multi-variate logistic regression, no individual polymorphism was significantly associated with MPH response; however, individuals with combinations of multiple polymorphisms were significantly associated with altered response [92]. Due to the many factors contributing to the response of MPH, a single variant within one gene is unlikely to account for enough observed variability on response, but expressing multiple variants within key genes, namely SLC6A3, SLC6A2, ADRA2A and DRD4 may lead to a more pronounced effect on MPH response.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH/NIGMS grant GM61374.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: RBA is a stockholder in Personalis Inc. and 23andMe, and a paid advisor for Youscript.

References

- 1.Sun Z, Murry DJ, Sanghani SP, Davis WI, Kedishvili NY, Zou Q, Hurley TD, Bosron WF: Methylphenidate is stereoselectively hydrolyzed by human carboxylesterase CES1A1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004; 310:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz JS, Straughn AB, Patrick KS: Advances in the pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: focus on methylphenidate formulations. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23:1281–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivas NR, Hubbard JW, Quinn D, Midha KK: Enantioselective pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dl-threo-methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992; 52:561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh T, Taylor P, Bosron WF, Sanghani SP, Hosokawa M, La Du BN: Current progress on esterases: from molecular structure to function. Drug Metab Dispos 2002; 30:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai T, Taketani M, Shii M, Hosokawa M, Chiba K: Substrate specificity of carboxylesterase isozymes and their contribution to hydrolase activity in human liver and small intestine. Drug Metab Dispos 2006; 34:1734–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faraj BA, Israili ZH, Perel JM, Jenkins ML, Holtzman SG, Cucinell SA, Dayton PG: Metabolism and disposition of methylphenidate-14C: studies in man and animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1974; 191:535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivas NR, Hubbard JW, Midha KK: Enantioselective gas chromatographic assay with electron-capture detection for dl-ritalinic acid in plasma. J Chromatogr 1990; 530:327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoyama T, Kotaki H, Honda Y, Nakagawa F: Kinetic analysis of enantiomers of threo-methylphenidate and its metabolite in two healthy subjects after oral administration as determined by a gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method. J Pharm Sci 1990; 79:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartlett MFE HP: Disposition and metabolism of methylphenidate in dog and man Fed Proc 1972:537. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick KS, Kilts CD, Breese GR: Synthesis and pharmacology of hydroxylated metabolites of methylphenidate. J Med Chem 1981; 24:1237–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perel JMB N; Wharton RN; Malitz S: Inhibition of imipramine metabolism by methylphenidate Fed Proceed 1969:418. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunninghake D: Studies of the inhibition of drug metabolism by methylphenidate Fed Proceed 1970:345. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeVane CL, Markowitz JS, Carson SW, Boulton DW, Gill HS, Nahas Z, Risch SC: Single-dose pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate in CYP2D6 extensive and poor metabolizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markowitz JS, Logan BK, Diamond F, Patrick KS: Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick KS, Straughn AB, Minhinnett RR, Yeatts SD, Herrin AE, DeVane CL, Malcolm R, Janis GC, Markowitz JS: Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 81:346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrero-Miliani L, Bjerre D, Stage C, Madsen MB, Jurgens G, Dalhoff KP, Rasmussen HB: Reappraisal of the genetic diversity and pharmacogenetic assessment of CES1. Pharmacogenomics 2017; 18:1241–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukami T, Nakajima M, Maruichi T, Takahashi S, Takamiya M, Aoki Y, McLeod HL, Yokoi T: Structure and characterization of human carboxylesterase 1A1, 1A2, and 1A3 genes. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2008; 18:911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stage C, Jurgens G, Guski LS, Thomsen R, Bjerre D, Ferrero-Miliani L, Lyauk YK, Rasmussen HB, Dalhoff K: The impact of CES1 genotypes on the pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate in healthy Danish subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 83:1506–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, Wang JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, Malcolm R, Johnson JA, Youngblood GL, Sweet DH, et al. : Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 82:1241–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemoda Z, Angyal N, Tarnok Z, Gadoros J, Sasvari-Szekely M: Carboxylesterase 1 gene polymorphism and methylphenidate response in ADHD. Neuropharmacology 2009; 57:731–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu HJ, Wang JS, DeVane CL, Williard RL, Donovan JL, Middaugh LD, Gibson BB, Patrick KS, Markowitz JS: The role of the polymorphic efflux transporter P-glycoprotein on the brain accumulation of d-methylphenidate and d-amphetamine. Drug Metab Dispos 2006; 34:1116–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu HJ, Wang JS, Donovan JL, Jiang Y, Gibson BB, DeVane CL, Markowitz JS: Interactions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder therapeutic agents with the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein. Eur J Pharmacol 2008; 578:148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SW, Lee JH, Lee SH, Hong HJ, Lee MG, Yook KH: ABCB1 c.2677G>T variation is associated with adverse reactions of OROS-methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013; 33:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris RM, Tang FL: Comparison of the effects of the isomers of amphetamine, methylphenidate and deoxypipradrol on the uptake of l-[3H]norepinephrine and [3H]dopamine by synaptic vesicles from rat whole brain, striatum and hypothalamus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1979; 210:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferris RM, Tang FL, Maxwell RA: A comparison of the capacities of isomers of amphetamine, deoxypipradrol and methylphenidate to inhibit the uptake of tritiated catecholamines into rat cerebral cortex slices, synaptosomal preparations of rat cerebral cortex, hypothalamus and striatum and into adrenergic nerves of rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1972; 181:407–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatley SJ, Volkow ND, Gifford AN, Fowler JS, Dewey SL, Ding YS, Logan J: Dopamine-transporter occupancy after intravenous doses of cocaine and methylphenidate in mice and humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 146:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen PH: The dopamine inhibitor GBR 12909: selectivity and molecular mechanism of action. Eur J Pharmacol 1989; 166:493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wall SC, Gu H, Rudnick G: Biogenic amine flux mediated by cloned transporters stably expressed in cultured cell lines: amphetamine specificity for inhibition and efflux. Mol Pharmacol 1995; 47:544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross SB: The central stimulatory action of inhibitors of the dopamine uptake. Life Sci 1979; 24:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweri MM, Skolnick P, Rafferty MF, Rice KC, Janowsky AJ, Paul SM: [3H]Threo-(+/−)-methylphenidate binding to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethylamine uptake sites in corpus striatum: correlation with the stimulant properties of ritalinic acid esters. J Neurochem 1985; 45:1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannestad J, Gallezot JD, Planeta-Wilson B, Lin SF, Williams WA, van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Carson RE, Ding YS: Clinically relevant doses of methylphenidate significantly occupy norepinephrine transporters in humans in vivo. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68:854–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Gatley SJ, Logan J, Ding YS, Hitzemann R, Pappas N: Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1325–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Pestreich LK, Patrick KS, Muniz R: A comprehensive in vitro screening of d-, l-, and dl-threo-methylphenidate: an exploratory study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han DD, Gu HH: Comparison of the monoamine transporters from human and mouse in their sensitivities to psychostimulant drugs. BMC Pharmacol 2006; 6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatley SJ, Pan D, Chen R, Chaturvedi G, Ding YS: Affinities of methylphenidate derivatives for dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. Life Sci 1996; 58:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G, Ding Y, Gatley SJ: Mechanism of action of methylphenidate: insights from PET imaging studies. J Atten Disord 2002; 6 Suppl 1:S31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikolaus S, Antke C, Beu M, Kley K, Larisch R, Wirrwar A, Muller HW: In-vivo quantification of dose-dependent dopamine transporter blockade in the rat striatum with small animal SPECT. Nucl Med Commun 2007; 28:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweri MM: Mercuric chloride and p-chloromercuriphenylsulfonate exert a biphasic effect on the binding of the stimulant [3H]methylphenidate to the dopamine transporter. Synapse 1994; 16:188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding YS, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Sugano Y: Carbon-11-d-threo-methylphenidate binding to dopamine transporter in baboon brain. J Nucl Med 1995; 36:2298–2305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K: Increased striatal dopamine transporter in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate as measured by single photon emission computed tomography. Neurosci Lett 2000; 285:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Threlkeld PG, Heiligenstein JH, Morin SM, Gehlert DR, Perry KW: Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002; 27:699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.During MJ, Bean AJ, Roth RH: Effects of CNS stimulants on the in vivo release of the colocalized transmitters, dopamine and neurotensin, from rat prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett 1992; 140:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuczenski R, Segal DS: Exposure of adolescent rats to oral methylphenidate: preferential effects on extracellular norepinephrine and absence of sensitization and cross-sensitization to methamphetamine. J Neurosci 2002; 22:7264–7271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butcher SP, Liptrot J, Aburthnott GW: Characterisation of methylphenidate and nomifensine induced dopamine release in rat striatum using in vivo brain microdialysis. Neurosci Lett 1991; 122:245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Franceschi D, Maynard L, Ding YS, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, Zhu W, Swanson JM: Relationship between blockade of dopamine transporters by oral methylphenidate and the increases in extracellular dopamine: therapeutic implications. Synapse 2002; 43:181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choong KC, Shen RY: Methylphenidate restores ventral tegmental area dopamine neuron activity in prenatal ethanol-exposed rats by augmenting dopamine neurotransmission. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004; 309:444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Easton N, Steward C, Marshall F, Fone K, Marsden C: Effects of amphetamine isomers, methylphenidate and atomoxetine on synaptosomal and synaptic vesicle accumulation and release of dopamine and noradrenaline in vitro in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology 2007; 52:405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuczenski R, Segal DS: Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem 1997; 68:2032–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiffer WK, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Alexoff DL, Logan J, Dewey SL: Therapeutic doses of amphetamine or methylphenidate differentially increase synaptic and extracellular dopamine. Synapse 2006; 59:243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmeichel BE, Berridge CW: Neurocircuitry underlying the preferential sensitivity of prefrontal catecholamines to low-dose psychostimulants. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013; 38:1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crunelle CL, van den Brink W, Dom G, Booij J: Dopamine transporter occupancy by methylphenidate and impulsivity in adult ADHD. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204:486–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kodama T, Kojima T, Honda Y, Hosokawa T, Tsutsui KI, Watanabe M: Oral Administration of Methylphenidate (Ritalin) Affects Dopamine Release Differentially Between the Prefrontal Cortex and Striatum: A Microdialysis Study in the Monkey. J Neurosci 2017; 37:2387–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schabram I, Henkel K, Mohammadkhani Shali S, Dietrich C, Schmaljohann J, Winz O, Prinz S, Rademacher L, Neumaier B, Felzen M, et al. : Acute and sustained effects of methylphenidate on cognition and presynaptic dopamine metabolism: an [18F]FDOPA PET study. J Neurosci 2014; 34:14769–14776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carmack SA, Howell KK, Rasaei K, Reas ET, Anagnostaras SG: Animal model of methylphenidate’s long-term memory-enhancing effects. Learn Mem 2014; 21:82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamashita M, Sakakibara Y, Hall FS, Numachi Y, Yoshida S, Kobayashi H, Uchiumi O, Uhl GR, Kasahara Y, Sora I: Impaired cliff avoidance reaction in dopamine transporter knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013; 227:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molinoff PB, Axelrod J: Biochemistry of catecholamines. Annu Rev Biochem 1971; 40:465–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim H, Heo HI, Kim DH, Ko IG, Lee SS, Kim SE, Kim BK, Kim TW, Ji ES, Kim JD, et al. : Treadmill exercise and methylphenidate ameliorate symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder through enhancing dopamine synthesis and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in spontaneous hypertensive rats. Neurosci Lett 2011; 504:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]