Summary

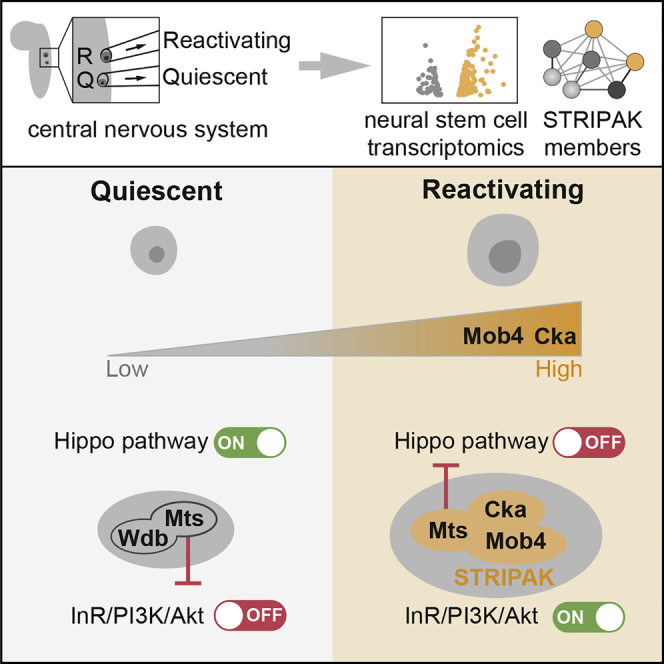

Adult stem cells reactivate from quiescence to maintain tissue homeostasis and in response to injury. How the underlying regulatory signals are integrated is largely unknown. Drosophila neural stem cells (NSCs) also leave quiescence to generate adult neurons and glia, a process that is dependent on Hippo signaling inhibition and activation of the insulin-like receptor (InR)/PI3K/Akt cascade. We performed a transcriptome analysis of individual quiescent and reactivating NSCs harvested directly from Drosophila brains and identified the conserved STRIPAK complex members mob4, cka, and PP2A (microtubule star, mts). We show that PP2A/Mts phosphatase, with its regulatory subunit Widerborst, maintains NSC quiescence, preventing premature activation of InR/PI3K/Akt signaling. Conversely, an increase in Mob4 and Cka levels promotes NSC reactivation. Mob4 and Cka are essential to recruit PP2A/Mts into a complex with Hippo kinase, resulting in Hippo pathway inhibition. We propose that Mob4/Cka/Mts functions as an intrinsic molecular switch coordinating Hippo and InR/PI3K/Akt pathways and enabling NSC reactivation.

Keywords: neural stem cells, quiescence, reactivation, STRIPAK members, Hippo signaling, InR/PI3K/Akt signaling

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Transcriptional profiling of reactivating versus quiescent NSCs identifies STRIPAK members

-

•

PP2A/Mts phosphatase inhibits Akt activation, maintaining NSC quiescence

-

•

Mob4 and Cka target Mts to Hippo to inhibit its activity and promote NSC reactivation

-

•

Mob4/Cka/Mts coordinate Hippo and InR/PI3K/Akt signaling in NSCs

The integration of signals allowing stem cell reactivation from quiescence is unclear. Gil-Ranedo et al. identify STRIPAK members Mob4, Cka, and PP2A/Mts through reactivating versus quiescent neural stem cell (NSC) transcriptional profiling. Their findings suggest that Mob4/Cka/Mts functions as an intrinsic molecular switch coordinating Hippo and InR/PI3K/Akt pathways, enabling NSC reactivation.

Introduction

Brain homeostasis and damage repair depend on the generation of new neurons and glia by neural stem cells (NSCs). In adult brains, most NSCs are found to be quiescent but can enter proliferation if prompted by extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli. The balance between quiescence and reactivation is critical for the maintenance of an NSC reservoir (Cavallucci et al., 2016, Chaker et al., 2016). Mechanistic insight underlying NSC quiescence and reactivation remains limited—in particular, how regulatory signals are integrated.

In the model organism Drosophila, embryonic NSCs give rise to the larval functional CNS. Similar to mammals, NSCs become quiescent at the end of embryogenesis and reactivate postembryonically to generate neurons and glia of the adult brain (Truman and Bate, 1988). Quiescence entry is regulated by Hox proteins, temporal transcription factors, and levels of the homeodomain transcription factor Prospero (Otsuki and Brand, 2019, Lai and Doe, 2014, Tsuji et al., 2008). NSCs are kept quiescent by the canonical Hippo pathway, whereby its core kinases Hippo and Warts prevent the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie from entering the nucleus and triggering growth (Ding et al., 2016, Poon et al., 2016). This signaling can be modulated by niche glia cells via the upstream regulators Crumbs and Echinoid, expressed in both glia and NSCs (Ding et al., 2016). NSC reactivation involves cell size increase, from 4 to 5 μm during quiescence, followed by entry into division (Ding et al., 2016, Chell and Brand, 2010, Prokop and Technau, 1991, Truman and Bate, 1988). NSCs continue to enlarge, reaching up to 10–15 μm when proliferating (Prokop and Technau, 1991, Truman and Bate, 1988). Nutrition stimulates reactivation (Britton and Edgar, 1998): dietary amino acids in the young larvae induce a systemic signal that triggers blood-brain barrier glia to secrete Drosophila insulin-like peptides (dILPs), a process that depends on gap junction proteins and synchronized calcium pulses (Spéder and Brand, 2014). dILPs activate the insulin-like receptor (InR)/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt cascade in neighboring NSCs, promoting quiescence exit (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011, Chell and Brand, 2010). The conserved heat shock protein 38/90 chaperone associates with InR to promote reactivation, and Spindle matrix proteins, including Chromator, function downstream of InR/PI3K/Akt signaling in this process (Huang and Wang, 2018, Li et al., 2017).

We performed a small-scale transcriptome analysis using single quiescent and reactivating NSC samples obtained directly from live Drosophila brains. Members of the evolutionary conserved striating-interacting phosphatase and kinase (STRIPAK) complex (Shi et al., 2016, Ribeiro et al., 2010) were identified and validated: monopolar spindle-one-binder family member 4 (Mob4); connector of kinase to AP-1 (Cka), which is the sole Drosophila Striatin protein; and the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A; Drosophila Microtubule Star [Mts]). STRIPAK contains multiple components, some of which are mutually exclusive, and STRIPAK members are part of a variety of regulatory proteins that can direct the pleiotropic PP2A to specific targets (Shi et al., 2016, Ribeiro et al., 2010, Virshup, 2000). In Drosophila and mammals, a STRIPAK-PP2A complex containing Mob4 and Cka was reported to inhibit Hippo signaling (Zheng et al., 2017, Couzens et al., 2013, Ribeiro et al., 2010). We show that PP2A/Mts, with its regulatory subunit Widerborst (Wdb), contributes to NSC quiescence via the inactivation of Akt, an essential component of the InR/PI3K/Akt signaling cascade. Conversely, NSC reactivation requires Mob4 and Cka, which are necessary within STRIPAK for Mts association to Hippo and subsequent Hippo pathway inhibition. These findings suggest a mechanism coordinating Hippo and InR/PI3K/Akt signaling in NSCs, enabling the transition from quiescence to proliferation.

Results

Transcriptome Analysis of Reactivating NSCs: Identification of Mob4, Cka, and PP2A/Mts

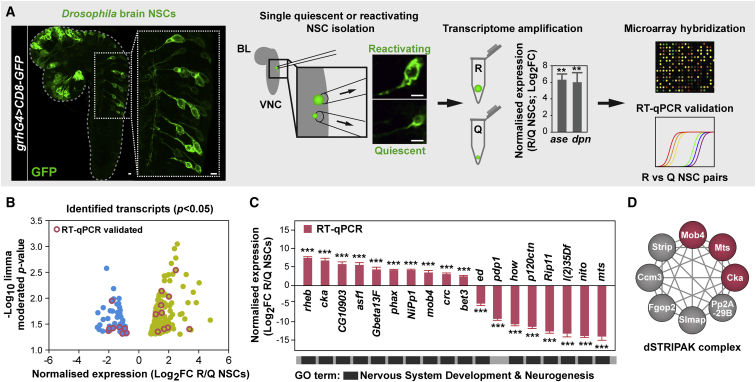

To identify the mechanisms regulating NSC reactivation, we performed a small-scale analysis comparing single-cell transcriptomes of quiescent and reactivating NSCs from Drosophila larval brains. By combining grh-Gal4 with UAS-CD8-GFP transgenic lines, cell membranes of approximately one-third of all NSCs (Chell and Brand, 2010) were specifically labeled in vivo. NSCs were individually harvested from 17 h after larval hatching (ALH) brains, when both quiescent (small; diameter 4–5 μm) (Ding et al., 2016, Chell and Brand, 2010) and reactivating (enlarged) cells can be easily distinguished. Of the enlarged NSCs, only non-dividing cells without any progeny were harvested. Cells were removed from the second and third thoracic segments of the ventral nerve cords (VNCs), minimizing potential differences from spatial positioning and avoiding retrieving a mix of type I and II NSCs, as the latter are absent from VNCs. Using our single-cell transcriptome protocol (Liu and Bossing, 2016, Bossing et al., 2012), cDNA from each NSC was readily obtained. Quantitative real-time PCRs confirmed that quiescent and reactivating cells expressed the NSC markers deadpan (dpn) and asense (ase), with higher levels in the latter. Single NSC transcriptomes were compared in pairs (three reactivating versus quiescent NSC pairs) on whole-genome Drosophila microarrays (Figure 1A). We used a limma moderated paired t test (Ritchie et al., 2015) to shortlist potential candidates, since the limited sample size did not support false discovery rate (FDR) correction. We identified 196 genes with consistent fold expression changes across all 3 replicates (p < 0.05), of which 145 are upregulated and 51 are downregulated (Figure 1B; Table S1; see Method Details). For quality control, we performed quantitative real-time PCR using independent single NSC samples on a subset of candidates classed mainly into nervous system development and neurogenesis Gene Ontology categories. Up- or downregulated expression for all 18 candidates tested in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs was confirmed, including echinoid (ed) and ras homolog enriched in brain (rheb), which are known to maintain NSC quiescence and promote reactivation, respectively (Ding et al., 2016, Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011) (Figures 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis of Reactivating NSCs

(A) Workflow: individual quiescent (Q) and reactivating (R) NSCs expressing CD8-GFP driven by grh-Gal4 were harvested from 17 h ALH CNSs, their mRNA reverse transcribed, and resulting cDNA amplified. Quantitative real-time PCRs confirmed higher ase and dpn expression in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs (normalized fold change [log2FC]; n = 3 NSC reactivating/quiescent pairs; error bars: SEMs; Student’s t test, ∗∗p < 0.01). NSC transcriptomes were compared on whole-genome microarrays (reactivating versus quiescent; three pairs) and a subset of identified targets validated by quantitative real-time PCRs. ALH, after larval hatching; BL, brain lobe; VNC, ventral nerve cord. Scale bars: 10 μm.

(B) Distribution of identified transcripts according to average fold change expression (x axis; log2FC) and p value (y axis; limma moderated t test; −log10 p value; p < 0.05). See also Table S1 and Figure S1.

(C) Normalized expression levels in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs obtained by quantitative real-time PCR for a subset of targets (log2FC; n = 3 NSC reactivating/quiescent pairs; error bars: SEMs; Student’s t test; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). The results validate the data from the microarray analysis. Most of the targets selected are classified under “nervous system development” and “neurogenesis” GO terms.

(D) STRING-based interaction network of a Drosophila PP2A-STRIPAK complex reported to inhibit Hippo signaling (Zheng et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2016, Ribeiro et al., 2010), highlighting (pink) the components identified in our transcriptome analysis and functionally characterized in this study.

Using FlyAtlas data (Chintapalli et al., 2007), we noted that our dataset (p < 0.05) is mostly enriched in genes expressed in the larval CNS, whereas among adult tissues, the highest enrichment is seen for genes expressed in ovaries, supporting reported gene sets associated with both NSC and germline stem cell maintenance and growth (Yan et al., 2014) (Figure S1A; Table S2). Most genes have highly conserved mouse (63%) and human orthologs (66%), and only 10% have no mammalian counterpart (Figure S1B; Table S1). When comparing the 175 mouse orthologs identified (single best matches) with transcripts found by previous studies as differentially expressed in quiescent versus activated mouse embryonic (Martynoga et al., 2013) or adult NSCs (Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015, Codega et al., 2014) and other stem cell types (Fukada et al., 2007, Venezia et al., 2004), we observed that the overlap is always highest (17–21 targets, 10%–12%) with any of the studies examining NSC transcriptomes (Figure S1C; Table S3). These results suggest that our small-scale single-cell transcriptome analysis generated high-quality data exposing conserved genes that are potentially involved in NSC reactivation. The analysis reveals transcripts encoding for some of the core STRIPAK complex members: mob4 and cka upregulated in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs, whereas mts, encoding the catalytic subunit of PP2A, downregulated (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). STRIPAK is involved in a variety of cellular functions (Shi et al., 2016), but it has no known role in NSC reactivation. To functionally test the components identified, we focused initially on Mob4.

Loss of Mob4 Prevents NSC Reactivation

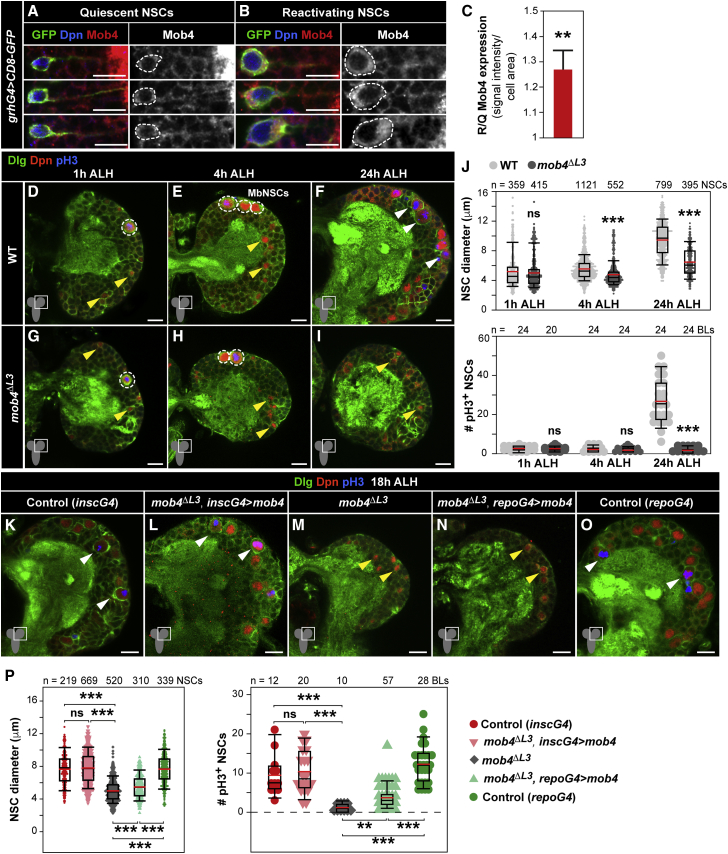

Mob4 is highly expressed in the mammalian and Drosophila CNS (Schulte et al., 2010, Baillat et al., 2001). After validating the differential expression of mob4 detected in NSCs (Figure 1C), we examined its protein levels. Immunostaining of NSCs highlighted with membrane-tagged GFP and Deadpan (Dpn) together with Mob4 antibodies in 17 h ALH brains, revealed higher Mob4 levels in reactivating (enlarged) versus quiescent (small) NSCs (Figures 2A–2C). To investigate the potential function of Mob4 in NSC reactivation, we first examined mob4 null mutants (mob4EYΔL3, hereafter mob4ΔL3), of which 10% survive to third-instar stages (Schulte et al., 2010). NSC (Dpn+) membranes labeled with anti-Discs large (Dlg) and mitosis with anti-phospho-histone H3 (pH3) antibodies enabled the scoring of size (maximum diameters) and proliferation. In newly hatched larvae (1 h ALH), no differences are detected between NSCs of mob4 mutants and controls in either brain lobes or VNCs (Figures 2D, 2G, 2J, S2A, S2D, and S2G). All NSCs are quiescent, with the exception of four mushroom body NSCs (MbNSCs) per brain lobe that continuously proliferate from embryonic stages (Ito and Hotta, 1992). However, as early as 4 h ALH, while NSCs in controls start to enlarge, those in mob4 mutants remain small. No NSC mitosis re-entry is detected in either group (Figures 2E, 2H, 2J, S2B, S2E, and S2G). At the end of the first-instar larval stage (24 h ALH), when many NSCs in controls are enlarged and dividing, the reduction in both NSC size and proliferation in mutants is striking, with the only mitotic NSCs corresponding to MbNSCs (Figures 2F, 2I, 2J, S2C, S2F, and S2G). 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assays monitoring entry into S phase confirmed that NSCs in mob4 CNSs are not able to re-enter the cell cycle (Figures S2H–S2J). NSC reactivation defects in mob4 mutants were similarly observed in brain lobes and VNCs. We focused subsequent studies on brain lobes.

Figure 2.

Loss of Mob4 Prevents NSC Mitotic Reactivation

(A–C) Mob4 is upregulated in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs. Examples of quiescent (small, A) and reactivating (enlarged, B) NSCs in 17 h ALH CNSs (VNC thoracic region) labeled with grh-Gal4 driving CD8-GFP (GFP, green), Mob4 (red), and Dpn (blue). Mob4 channel also shown in monochrome. Dashed lines: cell bodies. (C) Mob4 protein quantification in reactivating normalized to quiescent NSCs (reactivating NSCs: n = 50, 8 BLs, 8 brains; quiescent NSCs: n = 50, 8 BLs, 8 brains; error bars: SEMs).

(D–J) NSC enlargement and division are impaired in mob4ΔL3 mutants. Wild-type (WT; D, 1 h ALH; E, 4 h ALH; F, 24 h ALH) and mob4ΔL3 brain lobes (G, 1 h ALH; H, 4 h ALH; I, 24 h ALH). NSCs (Dpn, red), cell membranes (Dlg, green), and divisions (pH3, blue). Yellow arrowheads: quiescent NSCs; white arrowheads: reactivated NSCs. Mushroom body NSCs (MbNSCs; dashed circles) are large and do not enter quiescence. At 1 and 4 h ALH, there are no NSC divisions, except in MbNSCs.

(J) Quantification of NSC diameters (1 h ALH: WT n = 359 NSCs, 10 BLs, 5 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 415 NSCs, 10 BLs, 7 brains; 4 h ALH: WT n = 1,121 NSCs, 14 BLs, 7 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 552 NSCs, 10 BLs, 5 brains; 24 h ALH: WT n = 799 NSCs, 10 BLs, 7 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 395 NSCs, 18 BLs, 9 brains) and proliferation (1 h ALH: WT n = 24 BLs, 12 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 20 BLs, 12 brains; 4 h ALH: WT n = 24 BLs, 12 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 24 BLs, 12 brains; 24 h ALH: WT n = 24 BLs, 12 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 24 BLs, 12 brains).

(K–P) Mob4 expression in NSCs, but not in glia, rescues NSC reactivation in mob4ΔL3 mutants to control levels. Brain lobes of control (K, insc-gal4), mob4ΔL3 expressing Mob4 in NSCs (L, mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > mob4), mob4ΔL3 (M), mob4ΔL3 expressing Mob4 in glia (N, mob4ΔL3, repo-gal4 > mob4), and control (O, repo-gal4) at 18 h ALH.

(P) Quantification of NSC diameters (insc-gal4 n = 219 NSCs, 3 BLs, 3 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > mob4 n = 669, 10 BLs, 5 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 520 NSCs, 7 BLs, 7 brains; mob4ΔL3, repo-gal4 > mob4 n = 310 NSCs, 6 BLs, 6 brains; repo-gal4 n = 339, 5 BLs, 5 brains) and proliferation (insc-gal4 n = 12 BLs, 12 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > mob4 n = 20 BLs, 10 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 10 BLs, 10 brains; mob4ΔL3, repo-gal4 > mob4 n = 57 BLs, 29 brains; repo-gal4 n = 28 BLs, 14 brains) at 18 h ALH.

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; p > 0.05: non-significant (ns). BLs, brain lobes. Anterior up. Scale bars: 10 μm.

See also Figure S2.

Since niche glial cells are involved in NSC reactivation (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011, Chell and Brand, 2010) and Mob4 is ubiquitous in the larval CNS (Schulte et al., 2010), we next tested whether Mob4 action is cell autonomous. We ectopically expressed mob4 specifically in NSCs or in glia of mob4 mutants using insc-Gal4 and repo-Gal4 drivers, respectively. NSCs were analyzed at 18 h ALH, when mitotic reactivation is ongoing. Re-introduction of Mob4 in NSCs of mob4 mutants rescued both NSC size growth and division to the levels observed in controls (Figures 2K–2M and 2P). We observed a small increase in NSC size and division when Mob4 was expressed from glia, but levels are markedly lower than in controls (Figures 2M–2P). Finally, we inhibited Mob4 specifically in NSCs by expressing mob4-RNAi (Schulte et al., 2010) using insc-Gal4, resulting in a significant, albeit small, reduction in NSC size and a decrease in NSC division at 18 h ALH (Figures S2K–S2M). We conclude that Mob4 functions primarily cell autonomously to promote NSC reactivation.

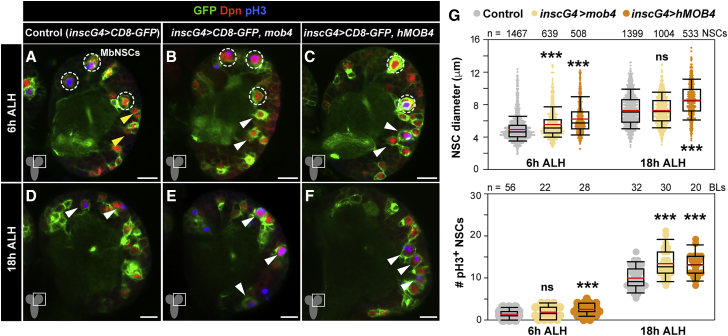

Overexpression of Mob4 or Its Human Ortholog Accelerates NSC Reactivation

Mob4 is highly conserved (78% identical at the amino acid level) to its human ortholog MOB4 (hMOB4, also known as Phocein), and ubiquitous expression of hMOB4 fully rescues the lethality of mob4 null larvae (Schulte et al., 2010). To determine whether increasing Mob4 or hMOB4 levels can promote NSC reactivation, we overexpressed these specifically in NSCs using insc-Gal4. Simultaneous expression of membrane-tagged GFP allowed for NSC size examination, and divisions were labeled with pH3 antibodies. At 6 h ALH, NSCs in controls have yet to re-enter mitosis. At this stage, Mob4 or hMOB4 overexpression results in a premature NSC size increase. No re-entry into division was seen upon Mob4 overexpression, but hMOB4 induced a minor but significant increase (Figures 3A–3C and 3G). At 18 h ALH, no difference in NSC size was detected upon Mob4 overexpression, but more NSCs were found in mitosis compared to controls. hMOB4 ectopic expression increased NSC size and induced a similar increase in the number of dividing NSCs as seen upon Mob4 overexpression (Figures 3D–3G). We next tested whether Mob4 overexpression leads to NSC overproliferation. Scoring of NSC divisions in late larval brain lobes (94 h ALH) revealed no differences from controls, indicating that Mob4 overexpression effects are restricted to the NSC reactivation process (Figures S3A–S3C). Finally, since NSC reactivation depends on nutritional stimulus (Britton and Edgar, 1998), we inquired as to whether Mob4 overexpression in NSCs could induce reactivation under diet-restriction conditions. In larvae reared in the absence of dietary amino acids, NSCs overexpressing Mob4 remained quiescent (Figures S3D–S3F). We conclude that increased Mob4 levels accelerate NSC reactivation, and this function may be evolutionary conserved. Yet, Mob4 is not sufficient to bypass the extrinsic nutrition stimulus required for NSC reactivation.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Mob4 or hMOB4 Increases NSC Growth and Division

(A–G) NSC-specific mob4 or human MOB4 (hMOB4) overexpression leads to premature NSC enlargement and mitosis entry. Brain lobes of control (A and D, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP) and mob4 (B and E, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4) or hMOB4 (C and F, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, hMOB4) overexpressing brains at 6 and 18 h ALH. NSCs in green (GFP) and red (Dpn), and divisions in blue (pH3). Dashed circles: MbNSCs; yellow arrowheads: quiescent NSC examples; white arrowheads: prematurely enlarging (B and C) and dividing NSC examples (D–F). Anterior up. Scale bars: 10 μm.

(G) Quantification of NSC diameters (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 1,467 NSCs, 20 BLs, 15 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 639 NSCs, 10 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, hMOB4 n = 508 NSCs, 7 BLs, 5 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 1,399 NSCs, 18 BLs, 15 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 1,004 NSCs, 13 BLs, 9 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, hMOB4 n = 533 NSCs, 7 BLs, 5 brains) and proliferation (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 56 BLs, 28 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 22 BLs, 11 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, hMOB4 n = 28 BLs, 14 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 32 BLs, 16 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 30 BLs, 15 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, hMOB4 n = 20 BLs, 10 brains).

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; p > 0.05: ns.

See also Figure S3.

Mob4 Regulates InR/PI3K/Akt and Hippo Signaling Activity in NSCs

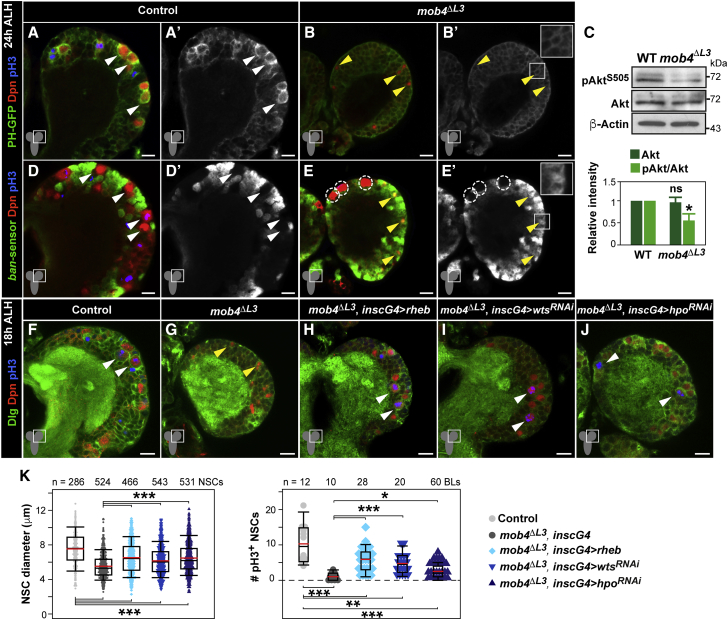

The Hippo pathway maintains NSCs in quiescence (Ding et al., 2016, Poon et al., 2016), whereas activation of InR/PI3K/Akt signaling cascade triggers reactivation (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011, Chell and Brand, 2010). To assess how Mob4 function relates to both pathways, we first examined their activity in the absence of Mob4. Upon activation, insulin receptors recruit PI3K to the cell membrane to convert phosphoinositol(4,5)P2 (PIP2) into phosphoinositol(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3), which in turn recruits the Akt protein kinase through its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, becoming activated by phosphorylation. This process can be monitored using a PH domain-GFP fusion protein (PH-GFP) binding PIP3 (Britton et al., 2002). We confirmed strong membrane-bound accumulation of PH-GFP in reactivated NSCs (Figures 4A and 4A’) (Chell and Brand, 2010). In contrast, NSCs in mob4 mutants show weak and diffused PH-GFP signals (Figures 4B and 4B’). We also observed reduced phosphorylated Akt levels in mob4 whole CNS lysates compared to controls, whereas total Akt levels were equivalent (Figure 4C). To examine Hippo signaling, we tested the activity of bantam (ban) microRNA that promotes NSC size growth and division (Ding et al., 2016). In quiescent NSCs, active Hippo signaling prevents ban transcription (Ding et al., 2016). We used a ban GFP-sensor system, in which GFP signal reduction reflects an increase in ban activity (Brennecke et al., 2003). No GFP is observed in control reactivated NSCs demonstrating ban activity (Ding et al., 2016) (Figures 4D and 4D’). However, the GFP signal is detected in the NSCs of mob4 mutants, indicating the absence of ban activity and Hippo pathway activation (Figures 4E and 4E’). We next tested whether activating InR/PI3K/Akt cascade or inhibiting Hippo pathways in the NSCs of mob4 mutants could rescue reactivation defects. Stimulation of target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling by Rheb overexpression activates the InR/PI3K/Akt cascade, promoting premature NSC exit from quiescence (Li et al., 2017, Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011). Overexpressing Rheb in the NSCs of mob4 mutants led to NSC size increase and division re-entry (Figures 4F–4H, and 4K). To inhibit Hippo signaling, we used RNAi against warts (wts) or hippo, which induce earlier NSC reactivation (Ding et al., 2016). In mob4 brains, expression of wts-RNAi or hippo-RNAi in NSCs induced cell size growth and mitosis re-entry (Figures 4F, 4G, and 4I–4K). We conclude that the InR/PI3K/Akt signaling cascade is inhibited, while the Hippo pathway stays active in NSCs upon the loss of Mob4, consistent with NSCs in mob4 mutants being unable to exit quiescence. Activation of InR/PI3K/Akt or inhibition of Hippo pathways can restore reactivation. However, the rescues are partial, with the NSC size and proliferation increase observed in mob4 mutant brains not reaching control levels (Figures 4F–4K). The results contrast with the effect of expressing rheb, hippo-RNAi, or wts-RNAi in a control background, where NSC growth and division surpass control levels (Li et al., 2017, Ding et al., 2016, Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011) and may also reflect insufficient activation or inactivation of the respective signals and/or regulation of both pathways that are essential for effective NSC reactivation.

Figure 4.

InR/PI3K/Akt Pathway Activation or Hippo Signaling Inhibition Rescues NSC Reactivation in mob4 Mutants

(A–C) InR/PI3K/Akt signaling is strongly reduced in mob4 NSCs. Expression of pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-GFP fusion (GFP, green) does not accumulate at NSC membranes of mob4 mutants as in controls. Brain lobes of control (A) and mob4ΔL3 mutants (B) at 24 h ALH. NSCs in red (Dpn) and divisions in blue (pH3). GFP channel also shown in monochrome (A’ and B’). Inset displays higher magnification (B’). Yellow arrowheads: quiescent NSC examples; white arrowheads: reactivated NSC examples.

(C) Phospho-Akt (pAktS505) is reduced in mob4 mutant brains, while total Akt levels are comparable to those in controls (24 h ALH brain extracts; β-actin: loading control). Quantification of protein signals (bottom; error bars: SEMs; n = 3 independent assays; Student’s t tests; ∗p < 0.05; p > 0.05: ns.

(D–E’) Hippo signaling remains active in mob4 NSCs. In contrast to controls, NSCs in mob4 mutants show no ban activity, except in MbNSCs (dashed circles). ban-activity sensor, in which decreased GFP signal (green) reflects increased ban activity, in brain lobes of control (D and D’) and mob4ΔL3 mutants (E and E’) at 24 h ALH. NSCs in red (Dpn) and divisions in blue (pH3). GFP channel also shown in monochrome (D’ and E’). Inset showing higher magnification (E’).

(F–K) NSC-specific expression of rheb activating InR/PI3K/Akt signaling and of warts (wts)-RNAi or hippo (hpo)-RNAi inactivating Hippo signaling can rescue NSC reactivation in mob4 mutants. Brain lobes of control (F, insc-gal4), mob4ΔL3 (G), mob4ΔL3 expressing Rheb in NSCs (H, mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > rheb), mob4ΔL3 expressing wts-RNAi in NSCs (I, mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > wtsRNAi), and mob4ΔL3 expressing hpo-RNAi in NSCs (J, mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > hpoRNAi) at 18 h ALH. NSCs in red (Dpn), cell membranes in green (Dlg), and divisions in blue (pH3). Anterior up. Scale bars: 10 μm and 17 μm in insets.

(K) Quantification of NSC diameters (insc-gal4 n = 286 NSCs, 4 BLs, 3 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 524 NSCs, 7 BLs, 7 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > rheb n = 466 NSCs, 6 BLs, 5 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > wtsRNAi n = 543 NSCs, 8 BLs, 5 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > hpoRNAi n = 531 NSCs, 8 BLs, 5 brains) and divisions (insc-gal4 n = 12 BLs, 12 brains; mob4ΔL3 n = 10 BLs, 10 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > rheb n = 28 BLs, 14 brains; mob4ΔL3; insc-gal4 > wtsRNAi n = 20 BLs, 10 brains; mob4ΔL3, insc-gal4 > hpoRNAi n = 60 BLs, 30 brains).

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Mob4 and Cka Cooperate to Reactivate NSCs and Assemble a PP2A-Hippo Complex

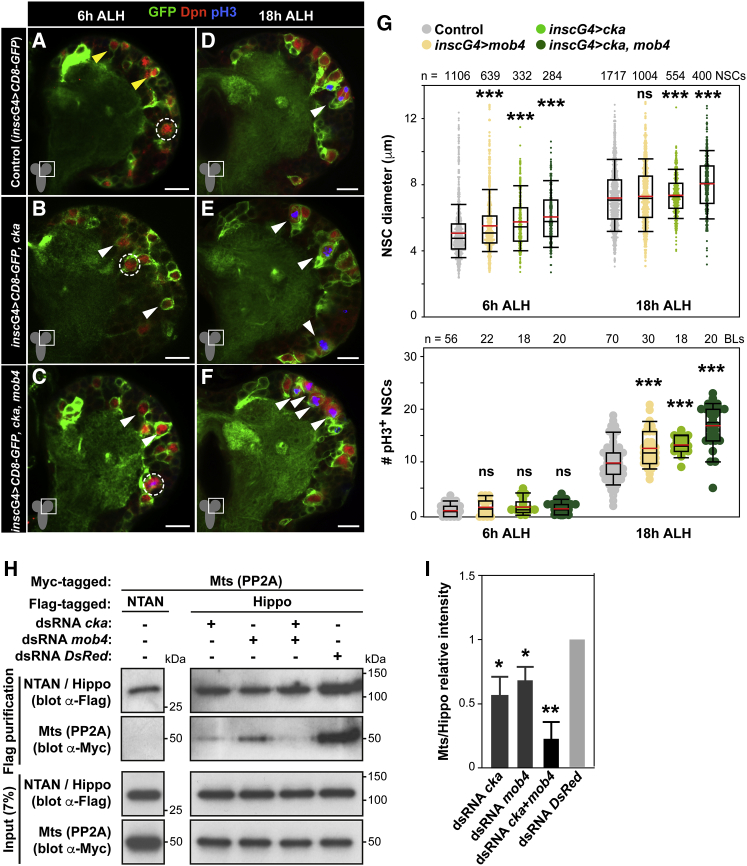

Our analysis of single NSC transcriptomes also identified the STRIPAK scaffold protein Cka, which is expressed throughout the CNS (Shi et al., 2016, Chen et al., 2002). Similar to Mob4, we found cka transcript and protein upregulated in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs (Figures 1C and S4A–S4C). To examine its function, we overexpressed Cka specifically in NSCs and observed premature NSC enlargement at 6 h ALH (Figures 5A, 5B, and 5G), as well as increased NSC size and divisions at 18 h ALH (Figures 5D, 5E, and 5G). Conversely, the expression of cka-RNAi resulted in a small but significant reduction in NSC size and decreased NSC mitosis at 18 h ALH (Figures S4D–S4F). Next, we simultaneously overexpressed Mob4 and Cka in NSCs and observed stronger effects compared to those upon single Mob4 or Cka overexpression (Figures 5A–5G; see also Figures 3B, 3E, and 3G).

Figure 5.

Cka and Mob4 Cooperate to Promote NSC Reactivation and Are Required for PP2A/Hippo Interaction

(A–G) NSC-specific cka or cka and mob4 double overexpression leads to premature enlargement and increased mitotic NSCs. Double overexpression results in stronger effects (see also Figure 3). Brain lobes of control (A and D, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP), cka (B and E, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka), and double cka and mob4 (C and F, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka, mob4) overexpressing brains at 6 and 18 h ALH. NSCs in green (GFP) and red (Dpn), and divisions in blue (pH3). Dashed circles: MbNSCs; yellow arrowheads: quiescent NSCs; white arrowheads: prematurely enlarging (B and C) and dividing NSCs (D–F). Anterior up. Scale bars: 10 μm.

(G) Quantification of NSC diameters (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 1,106 NSCs, 15 BLs, 10 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 639 NSCs, 10 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka n = 332 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka, mob4 n = 284 NSCs, 8 BLs, 8 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 1,717 NSCs, 19 BLs, 14 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 1,004 NSCs, 13 BLs, 9 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka n = 554 NSCs, 8 BLs, 4 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka, mob4 n = 400 NSCs, 6 BLs, 4 brains) and divisions (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 56 BLs, 28 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 22 BLs, 11 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka n = 18 BLs, 9 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka, mob4 n = 20 BLs, 10 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4>CD8-GFP n = 70 BLs, 38 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mob4 n = 30 BLs, 15 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka n = 18 BLs, 9 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, cka, mob4 n = 20 BLs, 10 brains). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; p > 0.05: ns. See also Figure S4.

(H and I) Depletion of Mob4 and/or Cka inhibits PP2A/Mts association to Hippo.

(H) CoIP assays using S2R+ cells expressing Myc-Mts and FLAG-Hippo or control FLAG-NTAN, in addition to RNAi against mob4 and/or cka or control DsRed (see also Figure S5). Lysates and FLAG-purified immunoprecipitates analyzed by western blot with indicated antibodies.

(I) Quantification of relative binding of Myc-Mts to FLAG-Hippo shown as a mean of the ratio between Myc-Mts and FLAG-Hippo signal intensities relative to control (DsRed RNAi) levels (n = 3 independent assays; error bars: SEMs; Student’s t tests; ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01).

STRIPAK negatively regulates Hippo signaling via the dephosphorylation of Hippo kinase by PP2A phosphatase (Couzens et al., 2013, Ribeiro et al., 2010). We examined whether the STRIPAK components Mob4 and Cka are essential for mediating the association of PP2A to Hippo. Co-immunoprecipitations (coIPs) were conducted on S2R+ cell lysates expressing FLAG-tagged Hippo or control FLAG-NTAN, plus Myc-tagged Mts. In addition, we performed RNAi targeting mob4 and/or cka, which effectively depletes the respective proteins (Figure S5A), using RNAi as a control against DsRed targeting red fluorescent protein. FLAG-Hippo co-immunoprecipitates Myc-Mts, as reported (Ribeiro et al., 2010), and no association is found with FLAG-NTAN. However, depletion of Mob4, Cka, or both impairs Hippo/Mts binding, with the latter nearly abolishing association (Figures 5H and 5I). We verified that the inhibition of Mob4 and Cka results in increased Hippo activation, as reported (Zheng et al., 2017, Ribeiro et al., 2010), and that chemical inhibition of PP2A with okadaic acid targeting PP2A, and to a lesser extent PP1 (Takai et al., 1992), leads to Hippo hyperphosphorylation as a positive control (Figure S5B). We conclude that Mob4 and Cka cooperate to promote NSC reactivation and are both required for the association of PP2A to Hippo, leading to its inactivation, which is consistent with the Hippo pathway remaining active in NSCs upon mob4 loss (Figures 4D–4E’).

PP2A Inactivates Akt Independently of STRIPAK Cka and Mob4 Members and Maintains Quiescent NSCs

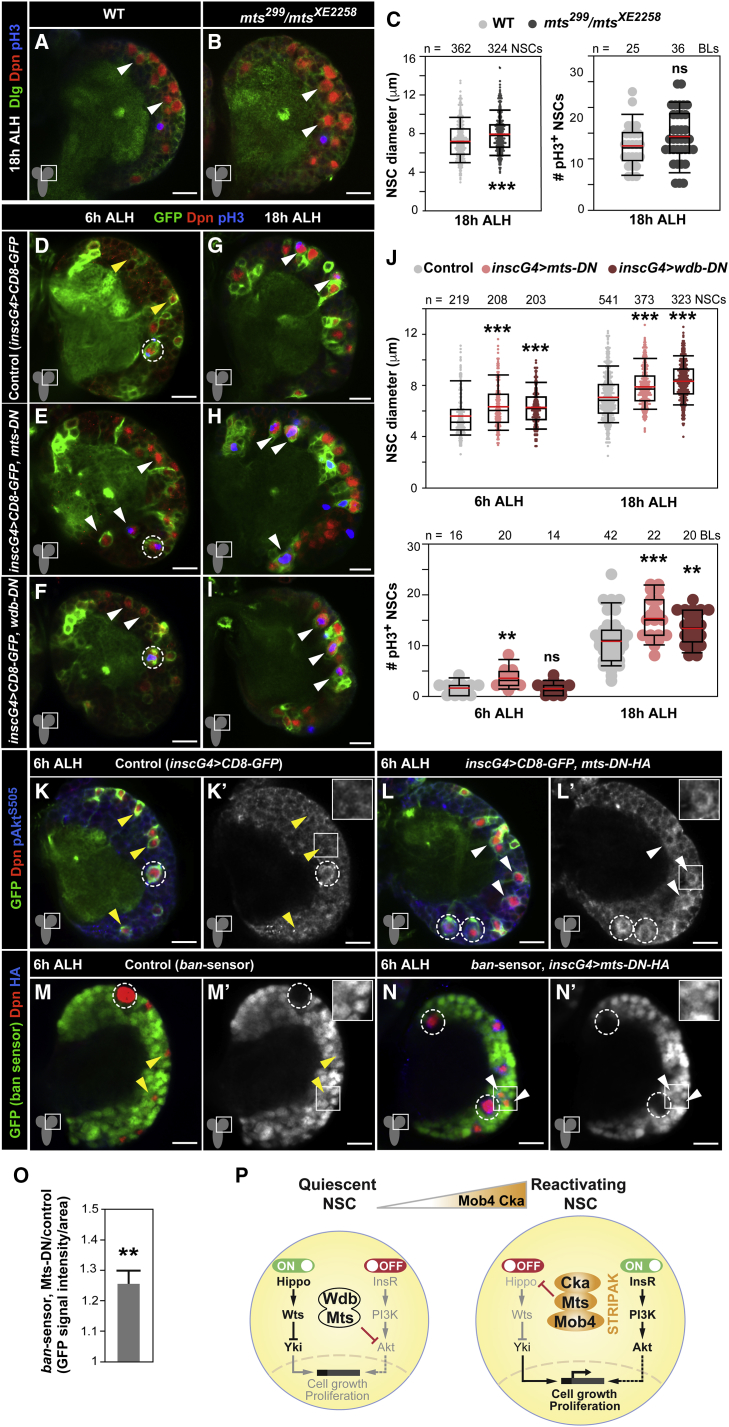

If PP2A/Mts would only function in NSCs to inactivate Hippo signaling via STRIPAK, then a prolonged NSC quiescence could be anticipated upon Mts inhibition. However, PP2A is also a well-established negative regulator of the insulin receptor signaling cascade, including by the dephosphorylation of Akt (Padmanabhan et al., 2009, Vereshchagina et al., 2008, Janssens and Goris, 2001). Using S2R+ cells, we observed that Mts inhibition with okadaic acid increases Akt phosphorylation, regardless of RNAi-mediated depletion of cka and mob4 (Figure S6A). In addition, in S2R+ cells expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Mts and Myc-tagged Akt, Mts co-immunoprecipitates with Akt. However, unlike for Mts/Hippo interaction, the depletion of cka and mob4 does not disturb Mts/Akt association, nor does it disturb the levels of phosphorylated Akt with or without insulin stimulation (Figures S6A–S6C). Next, we examined whether impaired Mts function affects NSC reactivation. Since mts null mutants (mtsXE-2258) are embryonic lethal (Snaith et al., 1996), we analyzed transheterozygotes harboring an mts hypomorphic allele surviving to pupal stages (mts299) (Wang et al., 2009) and mtsXE-2258. Reactivating NSCs in mts299/mtsXE-2258 mutants shows a mild increased cell size as compared to controls (Figures 6A–6C). To knock down mts specifically in NSCs, we expressed a dominant-negative mts mutant (mts-DN) lacking the N-terminal region of the phosphatase domain (Hannus et al., 2002). Premature NSC size increase and entry into division were observed (Figures 6D, 6E, 6G, 6H, and 6J), strengthening the results using mts transheterozygotes. We then examined whether the regulatory PP2A subunit Wdb, shown to modulate Akt downstream of InR/PI3K/Akt signaling in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Rodgers et al., 2011, Padmanabhan et al., 2009, Vereshchagina et al., 2008), may also function in NSCs. Similar to mts-DN, expression of a truncated wdb mutant form acting as a dominant negative (wdb-DN) (Hannus et al., 2002) leads to increased NSC size growth at 6 h ALH and a higher number of mitotic NSCs at 18 h ALH (Figures 6D, 6F, 6G, 6I, and 6J). Next, we ascertained whether PP2A/Mts inhibition affects pAkt levels. A premature increase in pAkt is seen in NSCs expressing mts-DN, which indicates abnormal InR/PI3K/Akt activation (Figures 6K–6L’). In this condition, a moderate but significant reduction of ban activity (indicated by ban-GFP sensor signal increase) is also observed (Figures 6M–6O). The results suggest that the inhibition of Mts can promote Hippo signaling activity in NSCs, but the effect is insufficient, possibly due to the availability of endogenous Mob4/Cka levels at this stage, or otherwise dominated by InR/PI3K/AKT activation, with the final outcome being premature NSC reactivation. Our data indicate that PP2A/Mts may play a dual role in early postembryonic NSCs: first with Wdb to target Akt contributing to quiescence maintenance and second with STRIPAK components Mob4 and Cka targeting Hippo signaling to promote reactivation (Figure 6P).

Figure 6.

Inactivation of PP2A Phosphatase Results in Premature NSC Reactivation

(A–C) PP2A/mts hypomorphic mutants show premature NSC size growth. Brain lobes of WT (A) and mts299/mtsXE2258 mutants (B) at 18 h ALH. NSCs in red (Dpn), cell membranes in green (Dlg), and divisions in blue (pH3). Arrowheads: NSC examples.

(C) Quantification of NSC diameters (WT n = 362 NSCs, 5 BLs, 3 brains; mts299/mtsXE2258 n = 324 NSCs, 6 BLs, 5 brains) and divisions (WT n = 25 BLs, 13 brains; mts299/mtsXE2258 n = 36 BLs, 27 brains). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; p > 0.05: ns.

(D–J) NSC-specific expression of dominant-negative (DN) forms of PP2A catalytic subunit Mts or regulatory subunit Wdb results in premature NSC size growth and an increased number of mitotically reactivated NSCs. Brain lobes of control (D and G, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP), mts-DN (E and H, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mts-DN), and wdb-DN (F and I, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, wdb-DN) expressing brains at 6 and 18 h ALH. NSC in green (GFP) and red (Dpn), and divisions in blue (pH3). Dashed circles: MbNSCs; yellow arrowheads: quiescent NSC examples; white arrowheads: prematurely enlarging (E and F) and mitotically reactivated NSCs (G–I).

(J) Quantification of NSC diameters (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 219 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > wdb-DN n = 208 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > mts-DN n = 203 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 541 NSCs, 8 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, wdb-DN n = 373 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mts-DN n = 323 NSCs, 5 BLs, 5 brains) and divisions (6 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 16 BLs, 8 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, wdb-DN n = 20 BLs, 10 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mts-DN n = 14 BLs, 7 brains; 18 h ALH: insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP n = 42 BLs, 21 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, wdb-DN n = 22 BLs, 12 brains; insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mts-DN n = 20 BLs, 10 brains). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; p > 0.05: ns.

(K–O) NSC-specific expression of mts-DN results in the increased expression of phosphorylated Akt, as well as a decrease in ban activity. (K–L’) Brain lobes of control (K and K’, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP) and mts-DN (L and L’, insc-gal4 > CD8-GFP, mts-DN) expressing brains at 6 h ALH. NSCs in green (GFP) and red (Dpn), and pAktS505 (blue). pAktS505 also shown in monochrome; insets showing higher magnifications (K’ and L’).

(M–O) ban-activity sensor, in which a decrease in GFP signal (green) reflects an increase in ban activity, in brain lobes of control (M and M’) and mts-DN expressing brains (N and N’) at 6 h ALH. NSCs in red (Dpn) and Mts-DN (HA-tag, blue). GFP channel also shown in monochrome; insets showing higher magnification (M’ and N’).

(O) GFP signal (ban-activity sensor) quantification in NSCs expressing mts-DN normalized to control NSCs (n = 84 mts-DN NSCs, 19 BLs, 14 brains; n = 46 control NSCs, 8 BLs, 5 brains; error bars: SEMs; Wilcoxon rank-sum test; ∗∗p < 0.01). Anterior up. Scale bars: 10 μm and 17 μm in insets.

(P) A model of action of STRIPAK Mob4/Cka/PP2A members: in quiescent NSCs, Mob4 and Cka levels are low, while PP2A (Mts/Wdb) phosphatase targets Akt, ensuring that InR/PI3K/Akt signaling is maintained switched off. Hippo signaling is active (Ding et al., 2016, Poon et al., 2016). Mob4 and Cka levels increase, promoting NSC size growth and entry into division; both are required to direct Mts to switch off Hippo signaling, while the InR/PI3K/Akt cascade becomes active (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011, Chell and Brand, 2010).

Discussion

Neural replenishment depends on the ability of NSCs to tightly control the balance between quiescence and proliferation (Tian et al., 2018, Chaker et al., 2016, Cheung and Rando, 2013). Recent advances in profiling quiescent and activated NSCs are increasing our understanding of these cell states. Most approaches have relied on brain tissue dissociation, cell sorting, and culturing procedures (Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015, Codega et al., 2014, Martynoga et al., 2013). Here, we reveal a transcript profile of single quiescent versus reactivating NSC samples obtained directly from live brains. The analysis of identified individual cells taken directly from living tissues at desired time points allows us to precisely examine the transcriptional control at the crossroads of crucial cell fates. Due likely to the reduced sample number and single-cell cDNA amplification variability (Tung et al., 2017, Macaulay and Voet, 2014) (Pearson’s r correlations obtained: quiescent NSCs 0.75 < r < 0.81, mean: 0.77; reactivating NSCs 0.58 < r < 0.67, mean: 0.61), our analysis did not support FDR correction. However, the identified genes meeting significance (limma moderated t test, p < 0.05) show consistent expression changes across replicates, and the regulation of all of the targets tested was independently validated. The high conservation with mammalian genes and partial overlap with orthologs reported to be differentially expressed in mouse quiescent versus activated NSCs suggest that our dataset is also a valuable resource for mammalian NSC research.

Adult NSCs must orchestrate extrinsic signals according to the organism’s status with intrinsic factors to transit between quiescence and proliferation. As in mammals, Drosophila NSCs are dependent on niche signals relaying external stimuli for both quiescence and reactivation (Tian et al., 2018, Chaker et al., 2016). In response to a nutritional cue, niche glia cells activate InR/PI3K/Akt signaling in NSCs to promote reactivation (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011, Chell and Brand, 2010). Niche glia cells also contribute to quiescence by maintaining Hippo signaling activation in NSCs (Ding et al., 2016). In mammals, the insulin and insulin-like growth factor pathway also plays a major role in adult NSC reactivation (Renault et al., 2009, Kippin et al., 2005, Arsenijevic et al., 2001), and while regulation of the Hippo pathway has not yet been implicated in this process, Hippo signaling maintains liver progenitors in quiescence and is indispensable for skin and intestinal regeneration (Wang et al., 2017, Zhou et al., 2009). Here, we show that Mob4, Cka, and PP2A phosphatase, identified in our transcriptome analysis, regulate NSC quiescence to reactivation states, and we propose that they function as an intrinsic integration mechanism of InR/PI3K/Akt and Hippo signals.

We detected the catalytic subunit of PP2A, Mts, downregulated at the transcript level in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs. Mts maintains NSCs in quiescence, preventing premature phosphorylation of Akt, a key component of the InR/PI3K/Akt signaling cascade. PP2A substrate specificity depends on the choice from a variety of regulatory subunits (Shi et al., 2016). In Drosophila, the regulatory subunit Wdb was shown to physically interact and negatively regulate Akt in ovaries (Vereshchagina et al., 2008), and has also been implicated in the inhibition of insulin signaling, controlling organism growth and metabolic regulation (Fischer et al., 2015). Wdb orthologs in Caenorhabditis elegans (PPTR1) and mammals (B56β) also dephosphorylate Akt to modulate InR/PI3K/Akt, indicating a conserved role (Rodgers et al., 2011, Padmanabhan et al., 2009). We demonstrate that the inhibition of Mts or of Wdb leads to similar premature NSC reactivation effects, suggesting that Wdb/Mts function together to maintain quiescence. PP2A has been linked to cellular quiescence in different contexts. In the developing Drosophila eye and wing, PP2A/Wdb contributes to a quiescent state upon terminal cell differentiation (Sun and Buttitta, 2015); in cycling human cells, PP2A is also required for stable quiescence, a function that is dependent on the B56γ subunit (Naetar et al., 2014). Thus, PP2A may also have an evolutionary conserved function in maintaining quiescence in NSCs, modulating the InR/PI3K/Akt signaling cascade. PP2A is a pleiotropic phosphatase. In proliferating Drosophila NSCs, it contributes to apical-basal polarity and prevents excess self-renewal at later larval stages. Here, Wdb was shown to play no role and instead Twins, a B55 subunit ortholog, regulated PP2A/Mts action (Chabu and Doe, 2009, Krahn et al., 2009, Ogawa et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2009).

In contrast to Mts, we found that Mob4 and Cka upregulated in reactivating versus quiescent NSCs. Both are scaffold proteins of STRIPAK, a large molecular complex that is highly conserved from fungi to humans containing PP2A (Shi et al., 2016). We demonstrate that the loss of Mob4 or Cka impairs NSC reactivation, while their overexpression can accelerate it. Furthermore, ectopic expression of human Mob4 also induced premature NSC size growth and mitosis entry, suggesting a conserved function. In cultured S2 cells, Mob4 was shown to focus spindle fibers during mitosis (Trammell et al., 2008). Our Mob4 analysis in NSCs exposed a function in cell size growth before mitosis and additionally showed that MbNSCs, which do not enter quiescence, continue dividing in the absence of Mob4, indicating that the role of Mob4 in NSC reactivation is independent of that reported in spindle fibers.

STRIPAK/PP2A associates with Hippo in Drosophila and mammalian cells, and restricts Drosophila Hippo kinase activity via dephosphorylation (Liu et al., 2016, Couzens et al., 2013, Ribeiro et al., 2010). Previous reports revealed cross-talk inhibition between Hippo and InR/PI3K/Akt pathways in both mammalian and Drosophila tissues (Straßburger et al., 2012, Tumaneng et al., 2012). We demonstrate that Mob4 and Cka are both required for the physical association of Mts to Hippo and its subsequent inhibition, as reported (Ribeiro et al., 2010). We also show that upon loss of Mob4, the Hippo pathway consistently remains switched on in NSCs, and InR/PI3K/Akt signaling is inhibited. Finally, we determined that the inhibition of Mts can enhance Hippo signaling in NSCs but that the effect is overcome by premature activation of InR/PI3K/Akt, resulting in earlier NSC reactivation, despite Hippo activity. Our data suggest that as the levels of STRIPAK members Mob4 and Cka increase in NSCs, a complex with Hippo kinase assembles recruiting PP2A/Mts protein to inactivate Hippo signaling. This may function as an intrinsic molecular switch to turn off Hippo signaling and allow the InR/PI3K/Akt cascade to turn on (Figure 6P). Given their large and versatile composition, it is not surprising that STRIPAK complexes are assigned to an increasing number of functions and linked to clinical conditions, including autism and cancer (Shi et al., 2016). It will be important to determine whether and how STRIPAK proteins contribute to regulating the reactivation of other stem cells.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-GFP | Gift from U. Mayor (U. Mayor, personal communication) | N/A |

| Chicken anti-GFP | Millipore | Cat# 06-896, RRID: AB_310288 |

| Guinea pig anti-Dpn | Gift from J. Knoblich (Levy and Larsen, 2013) | RRID: AB_2314299 |

| Guinea pig anti-Mob4 | Gift from T. Littleton (Schulte et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Mouse anti-Dlg | DSHB | Cat# 4F3 anti-discs large, RRID: AB_528203 |

| Rabbit anti-pH3 | Abcam | Cat# ab5176, RRID: AB_304763 |

| Rabbit anti-Cka | Gift from W. Du (Weng and Wei, 2002) | N/A |

| Rabbit anti-pAKTS505 | CST | Cat# 4054, RRID: AB_331414 |

| Mouse anti-Flag clone M2 | Sigma | Cat# F3165, RRID: AB_259529 |

| Rat anti-HA clone 3F10 | Roche | Cat# 11867431001, RRID: AB_390919 |

| Rat IgG | Sigma | Cat# I4131, RRID: AB_1163627 |

| Rabbit anti-Akt | CST | Cat# 9272, RRID: AB_329827 |

| Rabbit anti-b-Actin | CST | Cat# 4967, RRID: AB_330288 |

| Mouse anti-Myc clone 9E10 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-40, RRID: AB_627268 |

| Rabbit anti-pMST1T183/pMST2T180 | CST | Cat# 3681S, RRID: AB_330269 |

| Guinea pig anti-Hippo | Gift from G. Halder (Hamaratoglu et al., 2006) | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Okadaic Acid | CST | Cat# 5934 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 Imaging Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# C10339 |

| Co-Immunoprecipitation Kit | Pierce | Cat# 26149 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Transcriptome data | This paper | GEO: GSE128646 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| D. melanogaster: Cell line S2R+ | Gift from B. Houdsen | FlyBase: FBtc0000150 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. melanogaster: mob4 mutant: y[1] w[∗]; Mob4[EYDeltaL3]/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Schulte et al., 2010) | BDSC: 36331; FlyBase: FBst0036331 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing mob4 RNAi: P{UAS-Mob4.RNAi.JS1}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Schulte et al., 2010) | BDSC:36488; FlyBase: FBst0036488 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing mob4: y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = UAS-Mob4.S}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Schulte et al., 2010) | BDSC: 36329; FlyBase: FBst0036329 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing hMOB4: y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = UAS-phocein.1}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Schulte et al., 2010) | BDSC: 36330; FlyBase: FBst0036330 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing cka-eGFP: w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = UASp-Cka.EGFP.C}2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 53756; FlyBase: FBst0053756 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing wdb-DN: w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = UAS-wdb.95-524.HA}6 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Hannus et al., 2002) | BDSC: 55053; FlyBase: FBst0055053 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing wts RNAi: y[1] sc[∗] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.GL01331}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Ding et al., 2016) | BDSC: 41899; FlyBase: FBst0041899 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing hpo RNAi: y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS00006}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Ding et al., 2016) | BDSC: 33614; FlyBase: FBst0033614 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing cka RNAi: y[1] v[1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HM05138}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 28927; FlyBase: FBst0028927 |

| D. melanogaster: Wild type: Oregon-R | Gift from M. Akam (Bossing and Technau, 1994) | FlyBase: FBsn0000276 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing rheb: w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = UAS-Rheb.Pa}3 | Gift from R. Sousa-Nunes (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011) | BDSC: 9689; FlyBase: FBst0009689 |

| D. melanogaster: Gal4 line under the control of grh: Grh-Gal4 | Gift from A.H. Brand (Chell and Brand, 2010) | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing mts-DN-HA: UAS-mts.dn181-HA | Gift from S. Eaton (Hannus et al., 2002) | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: line expressing pleckstrin homology domain-GFP fusion protein: PH-GFP (tGPH) | Gift from B. Edgar (Britton and Edgar, 1998) | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: bantam GFP-sensor line, ban-sensor (db20) | Gift from S.M. Cohen (Brennecke et al., 2003) | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: mtsXE225839 mutant: mtsXE2258/CyO, P{sevRas1.V12}F1 and mts299 mutant | Gifts from H. Wang (Wang et al., 2009) | BDSC: 5684; FlyBase:FBst0005684 N/A for mts299 |

| D. melanogaster: Gal4 line under the control of insc: w[∗]; P{w[+mW.hs] = GawB}insc[Mz1407] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 8751; FlyBase:FBst0008751 |

| D. melanogaster: Gal4 line under the control of repo: w[1118]; P{w[+m∗] = GAL4}repo/TM6, tb | Gift from A. Hidalgo | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing CD8-GFP: y[1] w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = UAS-mCD8::GFP.L}LL5, P{UAS-mCD8::GFP.L}2 | Lee and Luo, 1999 | BDSC: 5137; FlyBase:FBst0005137 |

| D. melanogaster: UAS line expressing dicer2: UAS-dicer2 | Ding et al., 2016 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer: Anchored polyT AAGCAGTGGTATCAAC GCAGAGTACT(26)VN |

Bossing et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Primer: SM AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAG TACGCrGrGrG |

Bossing et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Primer: Nested AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT | Bossing et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Primers used for RT-qPCR | See Table S4 | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence mob4: Forward: TAATAC GACTCACTATAGGGagatgtggaagtacgagcacctg |

Schulte et al., 2010 | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence mob4: Reverse: TAATACG ACTCACTATAGGGagatgcgagaagatgcgatacac |

Schulte et al., 2010 | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence cka: Forward: TAATACG ACTCACTATAGGGatacgggtccagttctgtgc |

This paper | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence cka: Reverse: TAATACG ACTCACTATAGGGtgttgtaggccaccacgata |

This paper | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence DsRed: Forward: TAATAC GACTCACTATAGGGgccgatgaacttcaccttgt |

This paper | N/A |

| dsRNA targeting sequence DsRed: Reverse: TAATAC GACTCACTATAGGGcgaggacgtcatcaaggagt |

This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: 12XCSL DsRedExpressDL | Hansson et al., 2006 | Addgene plasmid #47683 |

| Plasmid: Flag-NTAN | Gift from P. Ribeiro (Ribeiro et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Plasmid: Flag-Hippo | Gift from P. Ribeiro (Ribeiro et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Plasmid: Myc-Mts | Gift from P. Ribeiro (Ribeiro et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Plasmid: HA-Mts | Gift from P. Ribeiro (Ribeiro et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Plasmid: Myc-Akt | Gift from W. Hongyan (Li et al., 2014) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| R/Bioconductor Limma | Ritchie et al., 2015 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html |

| STRING v10.5 | Szklarczyk et al., 2015 | https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl?sessionId=QMsQ2cmXKFYZ&input_page_show_search=on |

| FlyAtlas | Chintapalli et al., 2007 | http://flyatlas.org/atlas.cgi |

| DIOPT – DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool | Hu et al., 2011 | https://www.flyrnai.org/cgi-bin/DRSC_orthologs.pl |

Contact for Reagent and Resources Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Claudia Barros (claudia.barros@plymouth.ac.uk).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Drosophila strains and husbandry

Drosophila stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center are: mob4EYΔL3 (36331) (Schulte et al., 2010) rebalanced over CyO, P(GAL4-twi.G)2.2; UAS-mob4RNAi (36488) (Schulte et al., 2010); UAS-mob4 (36329) (Schulte et al., 2010); UAS-hMOB4 (36330) (Schulte et al., 2010); UAS-cka-eGFP (53756); UAS-wdb-DN (UAS-wdb.95-524.HA; 55053) (Hannus et al., 2002); UAS-wtsRNAi (41899) (Ding et al., 2016); UAS-hpoRNAi (33614) (Ding et al., 2016) and UAS-ckaRNAi (28927). Other stocks used are: Wild-type Oregon-R (kind gift from M. Akain); UAS-rheb (Blomington 9689) (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011) (kind gift from R. Sousa-Nunes); grh-Gal4 (Chell and Brand, 2010) (kind gift from A.H. Brand); UAS-mts-DN (UAS-mts.dn181-HA) (Hannus et al., 2002) (kind gift from S. Eaton); PH-GFP (tGPH) (Britton and Edgar, 1998) (kind gift from B. Edgar); ban-sensor (db20) (Brennecke et al., 2003) (kind gift from S.M. Cohen), mts299 and mtsXE2258 (Wang et al., 2009) (kind gifts from H. Wang). NSC-specific RNAi and overexpression assays were performed using insc-Gal4 (w1118; p{GAWB}inscMZ1407) and glial-specific expression assays used repo-Gal4 (w1118; p{GAWB}repo/TM6b, iab-lacZ). grh-Gal4 driver was recombined with UAS-CD8-GFP. For rescue experiments, insc-Gal4 and repo-Gal4 drivers were recombined or combined with the mob4EYΔL3 mutant strain. For other assays, the insc-Gal4 driver was recombined with UAS-CD8-GFP and/or combined with UAS-dicer2 (Ding et al., 2016). Fly lines were kept in standard Drosophila fly food. Egg collections and larvae rearing were performed on agar juice plates (21 g agar, 200ml of grape juice per l of water) supplemented with yeast paste. Egg lays were collected in either 30min or 1h time-windows. For nutritional deprivation experiments, freshly hatched larvae were transferred to agar plates prepared with amino-acid free media (5% sucrose, 1% agar in phosphate buffered saline, PBS).

S2R+ cell culture, transfection and drug treatment

S2R+ cells (kind gift from B. Houdsen) were maintained in 25- or 75-cm2 T-flasks at 25°C in Schneider′s Medium (GIBCO) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (One Shot, GIBCO) and antibiotics. For transient transfections, 1.6x106 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates. Effectene transfection reagent (Quiagen) was used to transfect 1 μg and/or 2 μg of each appropriate plasmid and/or dsRNA, respectively, following manufacturer guidelines. Cells were incubated 72 hours before harvest. Plasmids used are Flag-NTAN, Flag-Hippo, Myc-Mts, HA-Mts (kind gifts from P. S. Ribeiro) and Myc-AKT (kind gift from W. Hongyan). For okadaic acid experiments, cells were transfected as above, incubated 70 hours and treated with 50 nM okadaic acid (CST) or 0.005% DMSO (vehicle; Corning) for 2 hours prior harvest.

Method Details

NSC transcriptome analysis

Single NSC harvest, mRNA isolation, cDNA generation and microarray hybridization were performed essentially as previously described (Bossing et al., 2012). Single quiescent (small; 4-5μm) and reactivating (enlarged) NSCs were individually removed from freshly dissected 17 ALH CNS expressing membrane-tagged GFP specifically in NSCs (grh-Gal4, UAS-CD8-GFP). Samples with any trace of non-fluorescent material were rejected. Each single cell was expelled in its own Eppendorf tube containing annealing mix: 0.3 μL anchored polyT primer (5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACT(26)VN-3′, 10pM), 0.3 μL SM primer (5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACGCrGrGrG-3′, 10pM), 0.4 μL RNase inhibitor (Superase, Ambion) and 2 μL Lysis Mix (10% Nonidet P-40, 0.1M DTT in DEPC-treated ultrapure water), and processed in less than 20 min. Each sample was spun (14000rpm, 1min, 4°C), primers annealed (3min, 70°C) and snap-frozen in dry ice/ isopropanol. 1.5 μL of mix 1 (1 μL Invitrogen first strand buffer, 0.5 μL 10mM dNTPs) and 0.5 μL of mix 2 (3 μL Invitrogen Superscript II reverse transcriptase, 0.5 μL Ambion Superase RNase inhibitor) were added per sample. Samples were thawed during centrifugation (14000rpm, 1 min, 4°C) and reverse transcribed (37°C, 90min), followed by enzyme thermal inactivation (65°C, 10 min). RNA was digested in 2 μL digestion mix (0.7 μL Roche RNase H buffer, 0.5 μL Roche RNase H, 0.8 μL ultrapure water) for 20min at 37°C, followed by enzyme thermal inactivation (65°C, 15 min). For cDNA PCR amplification, 2 μL of nested primer (5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3′), 2 μL dNTPs (10mM), 5 μL Roche buffer, 0.5 μL Roche Long Expand polymerase and 34.5 μL of ultrapure water were added. PCR program: one cycle (95°C 3min, 50°C 5min, 68°C 15min) followed by 25 cycles (95°C 20 s, 60°C 1min, 68°C 7min). 3 pairs of NSC quiescent/ reactivating samples showing clear banding patterns on agarose gels were sent for microarray analysis (FlyChip, University of Cambridge). 1 μg of each sample were Klenow-labeled using BioPrime DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen) in the presence of Cy3- or Cy5-dCTP (GE Healthcare) for 2 hours 37°C. Unincorporated dye and nucleotides were removed using AutoSeq G-50 columns (GE Healthcare), following manufacturer instructions. Cy3- and Cy5-labeled pairs of samples were combined with salmon sperm DNA as blocking agent and co-hybridized (16 hours, 51°C) in a HybStation hybridization station (Digilab Genomic Solutions) on long oligonucleotides FL003 microarrays (International Drosophila Array Consortium; Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GPL14121). Post-hybridization washes were performed according to Full Moon Biosystems protocols. Detailed protocols for labeling, hybridization and washing can be requested from the Cambridge Systems Biology Centre UK (https://www.sysbiol.cam/ac.uk/CSBC). Arrays were scanned at 5 μm resolution (GenePix scanner, Axon Instruments) using optimized PMT gain settings for each channel.

RT-qPCR validation of selected genes was done using SYBRGreen on a StepOnePlus thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) and primers indicated in Table S4. ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) was used as internal calibrator for all reactions. Single NSC cDNA samples used were obtained as described above. Candidates validated were also selected based on their Gene Ontology (GO) Nervous system development and Neurogenesis classification (STRING v10.5) (Szklarczyk et al., 2015).

Tissue-specific expression of identified targets was performed using FlyAtlas (Chintapalli et al., 2007). Gene orthology analysis used DIOPT (DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool) (Hu et al., 2011). Protein-protein interaction network of Drosophila PP2A-STRIPAK components was performed using STRING (v10.5) (Szklarczyk et al., 2015) with experimental-based data only as source, and as previously described (Zheng et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2016, Ribeiro et al., 2010).

Immunohistochemistry and EdU incorporation

Immunohistochemistry assays were performed as previously described (Chell and Brand, 2010), with minor modifications. Briefly, larval CNSs were dissected in PBS and fixed for 20 min in 4% formaldehyde/PBS with 5 μM MgCl2 and 0.5 μM EGTA or 10 μM MgCl2 and 1 μM EGTA (3rd instar larvae), followed by washes in PBS (2 × 10 min, 3 rinses between washes) and block for 1h in PBST (PBS, 1% Triton X-100) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Primary antibodies were incubated in PBST overnight or for 2 nights at 4°C. CNSs were washed in PBST and secondary antibodies incubated 2h at room temperature, followed by PBST washes and sequentially embedding in 50% and 70% glycerol before mounting in a 1:1 mix of 70% glycerol and Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Antibodies used are: rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, kind gift from U. Mayor), chicken anti-GFP (1:500, Millipore), guinea pig anti-Dpn (1:2000, kind gift from J. Knoblich), guinea pig anti-Mob4 (1:1000, kind gift from T. Littleton), mouse anti-Dlg (1:50, DSHB), rabbit anti-pH3 (1:1000, Abcam), rabbit anti-Cka (1:1000, kind gift from W. Du), rabbit anti-pAKTS505 (1:50, CST) and rat anti-HA clone 3F10 (1:1000, Roche). EdU incorporation assays were performed as previously described (Sousa-Nunes et al., 2011). Briefly, CNSs were dissected in PBS and incubated in 10 μM EdU/PBS for 1h at room temperature. CNSs were fixed for 15min in 4% formaldehyde/PBS and incorporated EdU detected using Click-iT EdU Imaging kit following manufacturer instructions (Invitrogen).

Image acquisition and processing

Images were obtained on a Leica SP8 confocal laser-scanning microscope using LAS X software. Quantifications were made using z stacks of 1.5 μm step size, comprising whole brain lobes, VNCs or CNSs. Representative images shown are single optical sections, with the exception of Figure 1A, which is a z-projection stack (3 steps, 0.5 μm each), and EdU incorporations, which are z-projection stacks encompassing whole CNSs. Images were processed in Fiji v2.0 or Adobe Photoshop CS6 and assembled in Adobe Illustrator CS6. NSC sizes (maximum diameters) (Chell and Brand, 2010), pH3 scorings, Mob4 and Cka signal intensities (pixel intensity/ NSC maximum area), ban-GFP signal intensity (pixel intensity/ NSC maximum area outlined by Dpn staining) and EdU voxel quantification were performed using Fiji v2.0 or Adobe Photoshop CS6.

dsRNA synthesis

For cka, mob4 and DsRed dsRNA, DNA templates of target genes were PCR amplified from larval genomic DNA or 12XCSL-DsRedExpressDL plasmid (Addgene) to include the T7 promoter sequence on both ends. Primers used are: dsRNAmob4_Fwd: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGagatgtggaagtacgagcacctg-3′(Schulte et al., 2010), dsRNAmob4_Rev: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGagatgcgagaagatgcgatacac-3′(Schulte et al., 2010), dsRNAcka_Fwd: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGatacgggtccagttctgtgc-3′, dsRNAcka_Rev: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGtgttgtaggccaccacgata-3′, dsRNADsRed_Fwd: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGgccgatgaacttcaccttgt-3′, dsRNADsRed_Rev:

5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGcgaggacgtcatcaaggagt-3′. The size of DNA bands was confirmed, purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN) and used as template for dsRNA synthesis. In vitro transcriptions were performed using MEGAscript T7 kit (Invitrogen), incubated for 6 hours at 37°C and treated with TURBO DNase (Invitrogen) for 15 min at 37°C. RNA was precipitated using LiCl precipitation solution (Invitrogen) and re-hydrated in ultrapure water. dsRNA was annealed by incubation at 65°C 30 min and cooled down to room temperature.

Co-immunoprecipitations and western blotting

S2R+ cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (25mM Tris, 0.15M NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5% glycerol; pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Complete, EDTA-free; Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitors (cocktails B+C; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cell extracts were spun at 14000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C and proteins quantified (BCA protein assay, Pierce). Using the Pierce Co-immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce), 20 μg of anti-Flag M2 (Sigma), anti-HA (3F10; Roche), or rat IgG (Sigma) were immobilized in 50 μL of AminoLink Plus Coupling resin slurry following manufacturer instructions. Protein lysates were incubated in the resin on a rotator at 4°C overnight, washed 4 times with PBS and eluted following manufacturer instructions. Detection of proteins was performed using standard SDS-PAGE and western blotting using ECL or ECL Plus chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). Antibodies used are: rabbit anti-Akt (1:500, CST), rabbit anti-pAktS505 (1:500, CST), rabbit anti-β-Actin (1:1000, CST), mouse anti-Flag clone M2 (1:3000, Sigma), mouse anti-Myc clone 9E10 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-Cka (1:5000, kind gift from W. Du), guinea pig anti-Mob4 (1:5000, kind gift from T. Littleton), rabbit anti-pMST1T183/pMST2T180 (1:500, CST), guinea pig anti-Hippo (1:5000, kind gift from G. Halder) and rat anti-HA clone 3F10 (1:3000, Roche).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Transcriptome data: all genes with raw signal intensity values below 150 were removed from the analysis, generating a matrix containing 2455 genes. Quantile normalization (Bolstad et al., 2003) across all samples was performed using R/Bioconductor limma package (Ritchie et al., 2015). Remaining genes were analyzed with limma, by fitting a linear model. Adjusting p-values with False Discovery Rate (FDR) did not reach statistical significance. Instead, a limma moderated paired t test was employed. Targets with expression fold changes with associated p < 0.05 values were used for subsequent analysis, including expression validation. Expression of selected candidate genes assayed by RT-qPCR was quantified using the Livak method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Other statistics were performed using SigmaPlot Version 12.5 (Systat software): Shapiro-Wilk and equal variance tests used to evaluate normality; Student′s t test applied when data fitted a normal distribution; Wilcoxon rank-sum test used for non-parametric data; p < 0.05 considered significant. Data from Drosophila in vivo assays were obtained from a minimum of two biological replica sets; sample numbers are indicated in figure legends. Cell culture/ biochemistry results derive from a minimum of three independent assays. Histograms show mean ± standard error of the mean. Boxplots represent 25th and 75th percentiles, black line indicates median, red line specifies mean, whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles.

Data and Software Availability

Processed transcriptome data is shown in Table S1. Raw transcriptome data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Onmibus (GEO) public database under ID code GSE128646.

Acknowledgments

We thank FlyChip (Cambridge Systems Biology Centre, University of Cambridge, UK) and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for their services. We are very grateful to those that kindly provided antibodies, fly lines, and plasmids (indicated in Method Details). We also thank Bettina Fisher, Steve Russell, and Matthias Futschik for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (ECF2010/0526), the BBSRC (BB/M004392/1), the DFG (BE4278/1-1), the Johannes Gutenberg University, Germany, and the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Plymouth, UK.

Author Contributions

All of the authors designed and performed the experiments. J.G.-R. and C.S.B. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: June 4, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.023.

Supporting Citations

The following references appear in the Supplemental Information: Berger et al., 2012, Kohyama-Koganeya et al., 2008, Zitserman et al., 2012.

Supplemental Information

For each gene identified in whole-genome microarray transcriptome analysis, the following are indicated: oligonucleotide microarray probe sequence, matched transcripts, FlyBase identifier (FBgn), official gene name (symbol), normalized expression fold change (log2FC reactivating/ quiescent NSCs) for each of the 3 NSC pairs analyzed and corresponding average normalized gene expression fold change, and p value (limma moderated t test). Genes are sorted by decreasing p values. Mouse and human orthologs of identified genes (single best matches; random ortholog listed if multiple equal scores) and corresponding orthology level score (DIOPT [Hu et al., 2011]; 0–15) are also shown in separate tabs.

For each gene identified on transcriptome analysis (limma moderated t test, p < 0.05), the following are indicated: FlyBase identifier, official gene name (symbol), and transcript expression enrichment in indicated tissues relative to levels in whole fly (FlyAtlas) (Chintapalli et al., 2007).

Tabs show mouse orthologs (single best matches only) of Drosophila genes identified in our transcriptome analysis (limma moderated t test, p < 0.05) and reported to be differentially expressed in mouse activated versus quiescent embryonic stem cell-derived NSCs (Martynoga et al., 2013), quiescent or activated NSCs isolated from adult mouse brains (Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015; Codega et al., 2014), quiescent or cycling satellite stem cells from adult mouse skeletal muscle (Fukada et al., 2007), and quiescent or proliferating adult mouse hematopoietic stem cells (Venezia et al., 2004). FlyBase identifier, fly gene symbol, mouse gene symbol, and orthology score (DIOPT 0–15) (Hu et al., 2011) are indicated.

References

- Arsenijevic Y., Weiss S., Schneider B., Aebischer P. Insulin-like growth factor-I is necessary for neural stem cell proliferation and demonstrates distinct actions of epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7194–7202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07194.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Arsenijevic, Y., Weiss, S., Schneider, B., and Aebischer, P. (2001). Insulin-like growth factor-I is necessary for neural stem cell proliferation and demonstrates distinct actions of epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2. J. Neurosci. 21, 7194-7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baillat G., Moqrich A., Castets F., Baude A., Bailly Y., Benmerah A., Monneron A. Molecular cloning and characterization of phocein, a protein found from the Golgi complex to dendritic spines. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:663–673. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baillat, G., Moqrich, A., Castets, F., Baude, A., Bailly, Y., Benmerah, A., and Monneron, A. (2001). Molecular cloning and characterization of phocein, a protein found from the Golgi complex to dendritic spines. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 663-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berger C., Harzer H., Burkard T.R., Steinmann J., van der Horst S., Laurenson A.S., Novatchkova M., Reichert H., Knoblich J.A. FACS purification and transcriptome analysis of drosophila neural stem cells reveals a role for Klumpfuss in self-renewal. Cell Rep. 2012;2:407–418. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Berger, C., Harzer, H., Burkard, T.R., Steinmann, J., van der Horst, S., Laurenson, A.S., Novatchkova, M., Reichert, H., and Knoblich, J.A. (2012). FACS purification and transcriptome analysis of drosophila neural stem cells reveals a role for Klumpfuss in self-renewal. Cell Rep. 2, 407-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bolstad B.M., Irizarry R.A., Astrand M., Speed T.P. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bolstad, B.M., Irizarry, R.A., Astrand, M., and Speed, T.P. (2003). A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19, 185-193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bossing T., Technau G.M. The fate of the CNS midline progenitors in Drosophila as revealed by a new method for single cell labelling. Development. 1994;120:1895–1906. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bossing, T., and Technau, G.M. (1994). The fate of the CNS midline progenitors in Drosophila as revealed by a new method for single cell labelling. Development 120, 1895-1906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bossing T., Barros C.S., Fischer B., Russell S., Shepherd D. Disruption of microtubule integrity initiates mitosis during CNS repair. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bossing, T., Barros, C.S., Fischer, B., Russell, S., and Shepherd, D. (2012). Disruption of microtubule integrity initiates mitosis during CNS repair. Dev. Cell 23, 433-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brennecke J., Hipfner D.R., Stark A., Russell R.B., Cohen S.M. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brennecke, J., Hipfner, D.R., Stark, A., Russell, R.B., and Cohen, S.M. (2003). bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113, 25-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Britton J.S., Edgar B.A. Environmental control of the cell cycle in Drosophila: nutrition activates mitotic and endoreplicative cells by distinct mechanisms. Development. 1998;125:2149–2158. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Britton, J.S., and Edgar, B.A. (1998). Environmental control of the cell cycle in Drosophila: nutrition activates mitotic and endoreplicative cells by distinct mechanisms. Development 125, 2149-2158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Britton J.S., Lockwood W.K., Li L., Cohen S.M., Edgar B.A. Drosophila’s insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Britton, J.S., Lockwood, W.K., Li, L., Cohen, S.M., and Edgar, B.A. (2002). Drosophila’s insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev. Cell 2, 239-249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cavallucci V., Fidaleo M., Pani G. Neural Stem Cells and Nutrients: Poised Between Quiescence and Exhaustion. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;27:756–769. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cavallucci, V., Fidaleo, M., and Pani, G. (2016). Neural Stem Cells and Nutrients: Poised Between Quiescence and Exhaustion. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 756-769. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chabu C., Doe C.Q. Twins/PP2A regulates aPKC to control neuroblast cell polarity and self-renewal. Dev. Biol. 2009;330:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chabu, C., and Doe, C.Q. (2009). Twins/PP2A regulates aPKC to control neuroblast cell polarity and self-renewal. Dev. Biol. 330, 399-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chaker Z., Codega P., Doetsch F. A mosaic world: puzzles revealed by adult neural stem cell heterogeneity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2016;5:640–658. doi: 10.1002/wdev.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chaker, Z., Codega, P., and Doetsch, F. (2016). A mosaic world: puzzles revealed by adult neural stem cell heterogeneity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 5, 640-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chell J.M., Brand A.H. Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell. 2010;143:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chell, J.M., and Brand, A.H. (2010). Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell 143, 1161-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen H.W., Marinissen M.J., Oh S.W., Chen X., Melnick M., Perrimon N., Gutkind J.S., Hou S.X. CKA, a novel multidomain protein, regulates the JUN N-terminal kinase signal transduction pathway in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:1792–1803. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1792-1803.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chen, H.W., Marinissen, M.J., Oh, S.W., Chen, X., Melnick, M., Perrimon, N., Gutkind, J.S., and Hou, S.X. (2002). CKA, a novel multidomain protein, regulates the JUN N-terminal kinase signal transduction pathway in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1792-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheung T.H., Rando T.A. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cheung, T.H., and Rando, T.A. (2013). Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 329-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chintapalli V.R., Wang J., Dow J.A. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chintapalli, V.R., Wang, J., and Dow, J.A. (2007). Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 715-720. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Codega P., Silva-Vargas V., Paul A., Maldonado-Soto A.R., Deleo A.M., Pastrana E., Doetsch F. Prospective identification and purification of quiescent adult neural stem cells from their in vivo niche. Neuron. 2014;82:545–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Codega, P., Silva-Vargas, V., Paul, A., Maldonado-Soto, A.R., Deleo, A.M., Pastrana, E., and Doetsch, F. (2014). Prospective identification and purification of quiescent adult neural stem cells from their in vivo niche. Neuron 82, 545-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Couzens A.L., Knight J.D., Kean M.J., Teo G., Weiss A., Dunham W.H., Lin Z.Y., Bagshaw R.D., Sicheri F., Pawson T. Protein interaction network of the mammalian Hippo pathway reveals mechanisms of kinase-phosphatase interactions. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:rs15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Couzens, A.L., Knight, J.D., Kean, M.J., Teo, G., Weiss, A., Dunham, W.H., Lin, Z.Y., Bagshaw, R.D., Sicheri, F., Pawson, T., et al. (2013). Protein interaction network of the mammalian Hippo pathway reveals mechanisms of kinase-phosphatase interactions. Sci. Signal. 6, rs15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ding R., Weynans K., Bossing T., Barros C.S., Berger C. The Hippo signalling pathway maintains quiescence in Drosophila neural stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10510. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ding, R., Weynans, K., Bossing, T., Barros, C.S., and Berger, C. (2016). The Hippo signalling pathway maintains quiescence in Drosophila neural stem cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 10510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fischer P., La Rosa M.K., Schulz A., Preiss A., Nagel A.C. Cyclin G Functions as a Positive Regulator of Growth and Metabolism in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fischer, P., La Rosa, M.K., Schulz, A., Preiss, A., and Nagel, A.C. (2015). Cyclin G Functions as a Positive Regulator of Growth and Metabolism in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]