Abstract

KEOPS complex is one of the most conserved protein complexes in eukaryotes. It plays important roles in both telomere uncapping and tRNA N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) modification in budding yeast. But whether KEOPS complex plays any roles in DNA repair remains unknown. Here, we show that KEOPS complex plays positive roles in both DNA damage response and homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair independently of its t6A synthesis function. Additionally, KEOPS displays DNA binding activity in vitro, and is recruited to the chromatin at DNA breaks in vivo, suggesting a direct role of KEOPS in DSB repair. Mechanistically, KEOPS complex appears to promote DNA end resection through facilitating the association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. Interestingly, inactivation of both KEOPS and Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 (MRX) complexes results in synergistic defect in DNA resection, revealing that KEOPS and MRX have some redundant functions in DNA resection. Thus we uncover a t6A-independent role of KEOPS complex in DNA resection, and propose that KEOPS might be a DSB sensor to assist cells in maintaining chromosome stability.

INTRODUCTION

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are serious threats to genome integrity and must be repaired to maintain cell survival. Two major strategies have been evolved to repair DSBs in eukaryotes, namely non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ directly joins the broken ends together, while HR involves pairing an exposed long 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) with a homologous donor sequence to repair DSBs. At molecular level, NHEJ and HR are quite different. NHEJ requires the binding of Ku70/80 heterodimer to the breaks, which prevents the ends from resection by nucleases and recruits DNA ligase and accessory factors to the ends (1,2). HR requires a long ssDNA generated by 5′-3′ resection of the DNA ends. In budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 (MRX) complex and Sae2 are responsible for the onset of 5′-strand resection to produce an intermediate, which is subjected to extensive processing by Exo1 and/or Dna2/Sgs1 (3–5). MRX initiates DNA end resection likely through its endonuclease activity, which is stimulated by both Sae2 and proteins that block the DNA ends, such as Yku (6–8). Thus, MRX–Sae2 promotes the binding of Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 through removing the obstacles and altering the structures at DNA ends (7–11). Moreover, Dna2/Sgs1 acts redundantly with MRX–Sae2 in DNA resection, whereas Exo1 does not (9,10). Dna2-mediated DNA 5′-strand resection requires both its endonuclease and translocase activity upon stimulation of Sgs1 (12,13). The ssDNA generated by the nucleases is coated and protected by Replication Protein A (RPA) complex, which recruits Mec1/Dcd2 complex to activate DNA damage checkpoint signaling (14). RPA complex is then displaced by Rad51, a key recombinase for homologous sequences searching and strand exchange (15,16).

In eukaryotes, the natural linear chromosomal ends resemble DSB ends. These physical ends form special DNA-protein complexes, named ‘telomeres’, to cap and protect the chromosome ends from being perceived as DSBs. Yku70/80 heterodimer and Cdc13/Stn1/Ten1 (CST) complex play critical roles in telomere capping. Yku complex directly binds the telomeric double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) to fulfil the capping function (17,18). Cdc13 is a ssDNA binding protein that specifically binds G-rich telomeric overhang (19,20). Loss of telomere capping in CDC13 mutants or YKU deletion mutants results in over-resection of C-rich strand by Exo1 (21–23). In a temperature-sensitive allele of CDC13, cdc13-1, telomere capping is deficient at non-permissive temperature (>26°C), and thus telomeres are recognized as sites of DNA damage in cdc13-1 mutant (24). These uncapped telomeres are vulnerable to nuclease activity, which generates overlong telomeric ssDNA, and thus elicits a checkpoint response mediated by Rad9 (22,25). Deletion of RAD9 or EXO1 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 (26).

KEOPS complex was primarily identified as a suppressor of cdc13-1 at non-permissive temperature (27,28). It comprises five subunits, Gon7, Pcc1, Kae1, Bud32 and Cgi121 (27,29). Deletion of CGI121 or BUD32 suppresses the accumulation of ssDNA and inhibits the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 strain at non-permissive temperature (27). Additionally, deletion of any KEOPS complex subunit results in short telomeres (27). Moreover, deletion of KEOPS subunit Cgi121 inhibits telomere recombination, and thus elongates replicative lifespan (30–32). However, the molecular mechanism by which KEOPS complex regulates telomere uncapping, elongation and recombination remains elusive.

Other than the functions in telomere regulation, KEOPS complex has been proved to catalyze the synthesis of N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) of tRNA in combination with Sua5 (33–36). SUA5 deletion also results in telomere shortening and deficiency of telomere recombination (37,38), suggesting KEOPS and SUA5 mutants share similar telomere phenotypes. Due to the critical role of t6A in accurate translation, it has been proposed that the defects in KEOPS mutants, such as slow cell growth, transcriptional deficiency and telomere shortening, are attributed to the lack of t6A (33,36,39). Interestingly, the defects of t6A modification and the slow growth caused by KEOPS subunit deletion can be fully complemented by cytoplasmic expression of Qri7, a yeast mitochondrial paralog of Kae1 (33,40,41). But the shortened telomeres are not fully rescued by the cytoplasmic expression of Qri7 (40,41). These results imply KEOPS complex has t6A-independent functions in telomere regulation. In this study, we have explored the role of KEOPS complex in uncapped telomeres and DSB repairs. The results indicate that KEOPS complex promotes DNA end resection through regulating the association of nucleases with the breaks. Interestingly, the function of KEOPS complex in DNA resection is partially redundant with that of MRX–Sae2 complex. Together, our findings shed light on a novel role of KEOPS complex in DSB response and repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids

The strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1 unless otherwise stated. Myc tagging strains were generated as described previously (42). Primers for real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Qri7ΔMTS ectopic expression plasmid was constructed by inserting the promoter of TDH3 gene (1 kb upstream of TDH3 gene) and terminator (0.5 kb downstream of TDH3 gene) into vectors of pRS42X. DNA fragment encoding Qri7ΔMTS (amino acids 34–407) was inserted between the promoter and terminator of TDH3 gene. his3-SC- plasmid used for HR rate assay was constructed in pRS316 plasmid as schematic showing in Figure 4A.

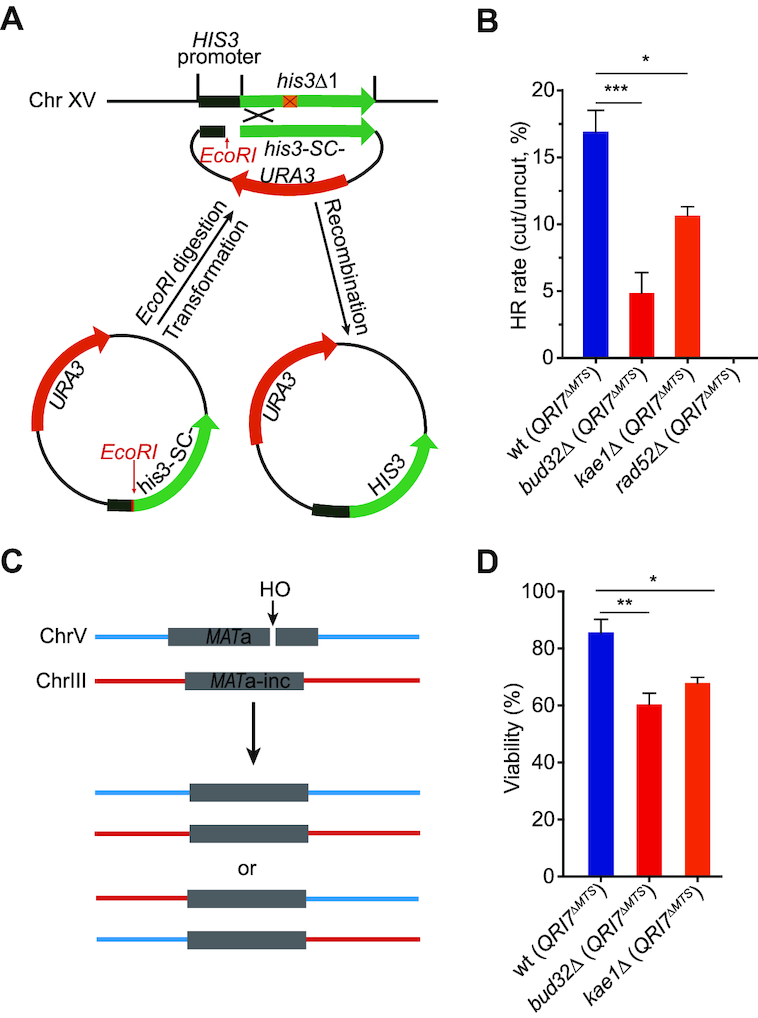

Figure 4.

KEOPS promotes homologous recombination. (A) Schematic representation of a plasmid-mediated HR assay. If the EcoRI linearized plasmid is introduced in yeast cells of BY4741/42, the cells can survive on histidine minus medium only when the plasmid is repaired through HR by using the genomic his3Δ1 DNA as a donor sequence. (B) Recombination rates in indicated strains. Recombination rates were assayed with the system described in A. The results are presented as the means ± s.e.m. (n ≥ 3). *** represents P < 0.001, * represents P < 0.05 (Student's t-test). (C) Schematic representation of ectopic recombination. (D) Viability of indicated strains after induction of a DSB as shown in C. n ≥ 4.

Expression and purification of KEOPS complex

Recombinant expression plasmid pJ241_KEOPS was used to express the whole KEOPS complex in BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli strain. The expression and purification of yeast KEOPS complex were performed as described by Collinet et al. (43).

Serial dilution assay

Cultures grown overnight were diluted to OD600 of 0.8. Cells were five-fold serially diluted and spotted on indicated plates. Plates were incubated at indicated temperatures for 2–5 days before pictures were taken.

Whole-cell protein extraction and immunoblot analysis

Cells were cultured to mid-log phase and DNA damage was induced by adding genotoxic agents. After grown for indicated time points, cells were collected and whole cell extracts were obtained by TCA method. SDS-PAGE was used to separate proteins. Primary antibodies were diluted in 5–10% milk and incubated overnight at 4°C or 1 h at room temperature, and secondary antibodies were diluted in 1× TBST. Antibodies used in this study: H2AS129ph (ab15083, 1:1000), Rad53 (ab104232, 1:1000), H4 (ab5823, 1:2000), Yku70 (gift from Dr Heidi Feldmann, University of Munich) (44), and Myc antibody is prepared by our laboratory.

Homologous recombination rate assay

Yeast cells were transformed with EcoRI-digested or undigested his3-SC-plasmid (ARS-CEN, URA3). The transformants were selected on Yeast Complete (YC) medium lacking both uracil and histidine (Ura-/His–). The yeast cells transformed with intact his3-SC- plasmid were selected on YC medium lacking uracil (Ura-). HR rate was determined by the ratio of transformants recovered from EcoRI-digested plasmid to the transformants recovered from the undigested plasmid. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a two-tailed t-test in GraphPad Prism 5.

The competition assay for HR and NHEJ

Yeast cells were transformed with EcoRI-digested his3-SC- plasmid (ARS-CEN, URA3). HR transformants were selected on Yeast Complete (YC) medium lacking histidine (His–), while transformants with repaired plasmid were selected on Yeast Complete (YC) medium lacking uracil (Ura-). The NHEJ transformants were determined by detracting the transformants grown on His–/Ura- medium from the transformants grown on Ura- medium. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a two-tailed t-test in GraphPad Prism 5.

DNA end resection assay

Cells were grown in YC medium containing 2% raffinose to log phase. HO induction was performed in medium containing 2% galactose. Cells were collected at indicated time intervals for DNA extraction. Southern blot and real-time PCR were performed to assay the resection intermediates as described previously (45). POL1 probe was used as loading control (31). Real-time PCR assay used primers flanking the StyI site located 0.7 kb away from the HO site. A pair of primers amplifying the DNA fragment located on chromosome V were used as a PCR internal control. PCRs were performed by the SYBR green system. The presented data are means of at least three independent experiments. The fraction of resected DNA was calculated by X = 2/[(1+2ΔCt)*f] as described previously (45,46), where ΔCt = Ctdigestion – Ctmock, and f is the fraction cut by HO.

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was performed as previously described with some modifications (47). Briefly, cells were grown to OD600 of ∼0.6 and DSB was induced by addition of galactose to a final concentration of 2%. Cells were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde and quenched cross-linking by adding 2.5 M glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mg/ml sodium-deoxycholate, 1% Triton-X, 0.14 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) using homogenizer and sonicated to obtain chromatin fragments of ∼500-bp in size. DNA was precipitated in the presence (+Ab) or absence (–Ab) of indicated antibodies (Rfa1: Agrisera, AS07214; Myc antibody was prepared by our lab) at 4°C for 4 h, followed by incubation with 20 μl Protein G beads (GE Healthcare) at 4°C for overnight. Beads were washed once by the following buffers at room temperature: lysis buffer, wash buffer I (1 mg/ml sodium-deoxycholate, 1% Triton-X, 0.05 M HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5)), wash buffer II (5 mg/ml sodium-deoxycholate, 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5), 1% NP-40) and 1× TE. Precipitated DNA was de-crosslinked at 65°C and purified by QIAGEN PCR purification Kit. ChIP enrichment was measured by real-time PCR. A pair of primers amplifying the DNA fragment located on chromosome V were used as a PCR internal control. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a two-tailed t-test in GraphPad Prism 5.

Chromatin preparation

Cells were grown in YPD medium to log-phase and exposed to 0.05% MMS for indicated time points. Chromatin was extracted as described previously with a few modifications (47). Briefly, spheroplasts were obtained by zymolase digestion for 30 min at 30°C. Spheroplasts were washed once with 1 ml zymolase buffer and suspended in EBX buffer with 0.5% Triton X-100. After NIB buffer cushion of spheroplasts, nuclear membrane was further lysed in EBX buffer with 1% Triton X-100. The chromatin pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 16 000 g at 4°C for 10 min. Proteins in chromatin pellets and whole cell extracts (WCE) were detected by western blot analysis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The EMSA assay was performed in a reaction of 10 μl mix containing 2 nM radioactively labeled probes (probe sequence: AACGTCATAGACGATTACATTGCTAGGACATCTTTGCCCACGT-TGACCCA), and KEOPS proteins (0–1.8 μM) in binding buffer (25 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MnCl2, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT). The reaction mix was incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The products were separated by 6% non-denaturing acrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE at 4°C. The gels were dried and exposed to storage phosphor screens which were scanned by phosphor imager.

Immunofluorescence assay

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (48) with a few modifications. Briefly, about 1 × 107 cells were collected and fixed by 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Then, cells were washed once by sorbitol buffer (1.1 M sorbitol, 0.1 M K2HPO4, pH 7.5), and treated by 1 μg/μl zymolase for 20 min at 37°C. Spheroplasts were washed once by sorbitol buffer and spotted on poly-l-lysine pre-treated slides. After rinsing in PBS-T buffer for 40 min, the slides were incubated with anti-Myc antibody. After washed by PBS-T buffer, the slides were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to Cy3 in dark. Next, slides were washed by PBS-T buffer and dyed by 1 μg/ml DAPI diluted in PBS buffer. At last, the slides were washed by PBS buffer and mounted on DAKO mounting medium. Confocal microscopy was carried out by OLYMPUS FV1200 Laser Scanning.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

Cells (0.5–1 × 107) collected from different time points were fixed by 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Then the cells were washed once by 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.2). Afterward, the cells were digested by 0.25 mg/ml RNaseA and 0.2 mg/ml Protease K diluted in sodium citrate buffer. The cells were resuspended in sodium citrate buffer and sonicated for 30 s. DNA was stained by 20 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI). FACS analysis was performed on a BD LSRII instrument.

Viability

The viability measurement of cells derived from tGI354 yeast strain was performed as previously described (49).

RESULTS

Qri7ΔMTS complements cytoplasmic t6A modification in KEOPS mutants

Budding yeast mitochondrion harbors a Kae1 paralog, Qri7, which catalyzes t6A synthesis in combination with Sua5 in mitochondria (33,34,40). Ectopic expression of Qri7 lacking mitochondrial targeting sequence (Qri7ΔMTS) in the cytoplasm of KEOPS-inactive cells restores both t6A modification and cell growth rate to the levels comparable with those seen in wild type cells (33,40,41). To dissect the potential t6A-independent functions of the KEOPS complex, we constructed KEOPS deletion strains in which the t6A modification remains intact. TDH3 gene is the most abundant and constitutively expressed protein gene in budding yeast (50), and its promoter was employed to overexpress Qri7ΔMTS in the cytoplasm of kae1Δ, bud32Δ, gon7Δ and pcc1Δ cells. As the t6A modification defect in the KEOPS mutants results in severely slow growth (33,40,41), cell growth was used as an indicator of the t6A modification. Ectopic expression of Qri7ΔMTS driven by TDH3 promoter completely rescued the slow growth phenotype in these KEOPS subunit null mutants (Figure 1A), suggesting that TDH3 promoter can drive enough Qri7ΔMTS expression to restore t6A modification in KEOPS mutants. These data are consistent with the findings of previous reports (33,40,41).

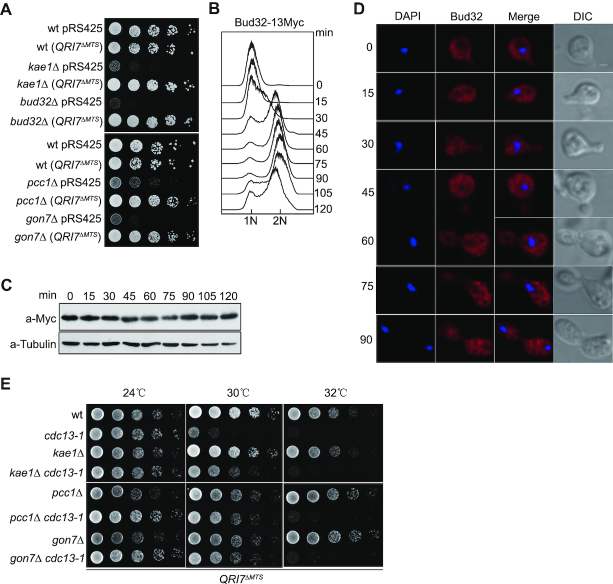

Figure 1.

Inactivation of KEOPS complex suppresses telomere-capping defect through a t6A-independent pathway. (A) Cell growth analysis. Qri7ΔMTS was expressed under the driving of TDH3 promoter in wild type (wt), kae1Δ, bud32Δ, pcc1Δ and gon7Δ strains. All indicated strains were plotted on selective medium by five-fold serial dilutions. (B) Cell cycle progression analysis by FACS. Cells were synchronized in G1 phase by α-factor. After release, cells were collected every 15 min intervals and subjected to FACS, immunoblot and immunofluorescence analyses. (C) Bud32–13Myc expression level during cell cycle progression. Cell samples taken from B were analyzed by western blot. (D) Bud32–13Myc distribution in cells during cell cycle progression. Cell samples taken from B were analyzed by immunofluorescence assay. (E) Temperature sensitivity analysis. Qri7ΔMTS was expressed in indicated strains and serial dilutions were spotted on selective medium. Plates were incubated at indicated temperatures for 2–3 days.

However, as a multi-subunit complex, KEOPS may not only function to maintain the overall content of t6A modification, but also coordinate t6A synthesis in time and space in cytoplasm. Direct detection of t6A distribution in cells was technically infeasible. Therefore, we detected protein levels and cellular distributions of the five subunits of KEOPS complex during cell cycle progression, because yeast Qri7 and KEOPS are essential and sufficient for t6A synthesis in the presence of Sua5 protein in vivo (36,40). We constructed yeast strains in which each subunit of KEOPS complex was individually tagged with the epitope of 13-Myc, and performed both immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analyses. The results showed that the protein levels of KEOPS subunits displayed little changes along cell cycle progression (Figure 1B, C and Supplementary Figure S1A–D), and each subunit seemed to be randomly distributed in whole cells, regardless of the changes of cell cycle stages (Figure 1B, D and Supplementary Figure S1A–D).

KEOPS has t6A-independent functions in uncapped telomere resection

KEOPS complex was initially identified as a telomere regulator that promotes telomere replication and uncapped telomere resection (27). Deletion of KEOPS subunits results in telomere shortening and suppression of the temperature sensitivity (ts) of the cdc13-1 mutant (27). To address whether or not the functions of KEOPS complex in telomeres are indirect consequences of t6A synthesis, we measured the telomere length in KEOPS mutants and their corresponding strains that expressed Qri7ΔMTS. Ectopic expression of Qri7ΔMTS had no effect on telomere length in wild type cells, and resulted in only a slight (∼50 bp) increase in telomere length in kae1Δ, bud32Δ, gon7Δ and pcc1Δ mutants (Supplementary Figure S2). These data are in line with previous results showing that Qri7ΔMTS can fully complement tRNA t6A modification, but not telomere length in KEOPS mutants (40,41).

We also examined the ts of kae1Δ cdc13-1, pcc1Δ cdc13-1 and gon7Δ cdc13-1 mutants. cdc13-1 mutant expressing Qri7ΔMTS was sensitive to non-permissive temperature of 30°C (Figure 1E). Deletion of KAE1, PCC1 or GON7 suppressed the ts of cdc13-1 mutant in the presence of Qri7ΔMTS expression (Figure 1E), suggesting that the telomere uncapping function of KEOPS complex is independent of t6A.

KEOPS complex is required for efficient DNA damage response

The uncapped telomeres mimic DSB ends. Many of the proteins involved in DSB sensing and end resection also participate in processing and/or maintenance of telomeres (51–54). Given that KEOPS complex functions in the resection of uncapped telomeres (Figure 1E) (27), we considered the possibility that KEOPS complex is involved in DSB repair. To test it, we assessed the sensitivity of Qri7ΔMTS overexpressed KEOPS mutants to genotoxic agents, and found that all these KEOPS subunit deletion cells were more sensitive to phleomycin (Phl), methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) and hydroxyurea (HU) than wild type (wt) cells (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S3A), suggesting that KEOPS complex may contribute to efficient response and/or repair of DNA damage. Bud32 is an essential subunit of KEOPS complex and displays protein kinase activity in vitro (55–57). We tested the requirement of the kinase activity of Bud32 for the DNA repair function of KEOPS complex. bud32K52A (QRI7ΔMTS) mutant, in which the kinase activity of Bud32 is eliminated (55), displayed the same sensitivity to MMS as bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain (Figure 2B), suggesting that the kinase activity of Bud32 is essential for the function of KEOPS complex in DNA damage repair.

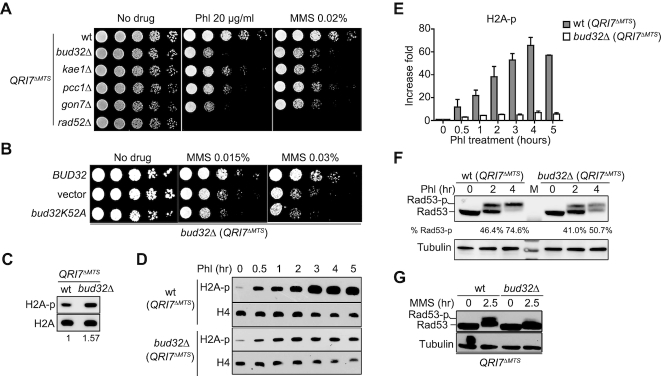

Figure 2.

Lack of KEOPS activity impairs efficient DNA damage response and repair. (A) Genotoxic sensitivity analysis of KEOPS mutants. Indicated strains were serially diluted and plotted on media containing phleomycin (Phl) or methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). (B) Genotoxic sensitivity analysis. Plasmid encoding wild type Bud32 (BUD32), Bud32K52A (bud32K52A) or empty plasmid (vector) was introduced in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells. The genotoxic sensitivity was assayed in the presence of MMS. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of H2AS129 phosphorylation (H2A-p). Whole-cell proteins were extracted from cells that were grown in normal conditions. (D, E) Immunoblotting analysis of H2AS129 phosphorylation (H2A-p) upon phleomycin (Phl) treatment. Cells were exposed to Phl for indicated time points (D). Whole-cell proteins were extracted, and H2A-p and H4 were analyzed. Quantification of the immunoblotting results was performed (E). Data are presented as fold changes relative to time point 0. Each value represents the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3). (F, G) Rad53 activation analysis. Cells of indicated strains were arrested in G2/M phase and exposed to Phl (F), or asynchronized cells were exposed MMS (G). Whole-cell proteins were extracted and Rad53 phosphorylation (Rad53-p) levels were monitored by western blot.

Then we asked whether KEOPS deletion leads to defective DNA-damage signaling. The phosphorylation levels of H2AS129 (H2A-p) and Rad53 (Rad53-p) were monitored. Deletion of BUD32 slightly increased the level of H2A-p (Figure 2C). Upon exposure to phleomycin, the H2A-p level in wild type cells was gradually increased, and reached >50-fold higher than that in untreated cells (Figure 2D, E and Supplementary Figure S3B). This robust increase of H2A-p was significantly compromised in bud32Δ, kae1Δ, gon7Δ and pcc1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) mutants (Figure 2D, E and Supplementary Figure S3B). Consistently, in the presence of either Phl or MMS, the bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells showed reduced phosphorylation level of Rad53 (Rad53-p) compared to wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 2F and G). These results indicate that KEOPS complex plays a critical role in DNA damage response.

KEOPS complex is required for DNA end resection

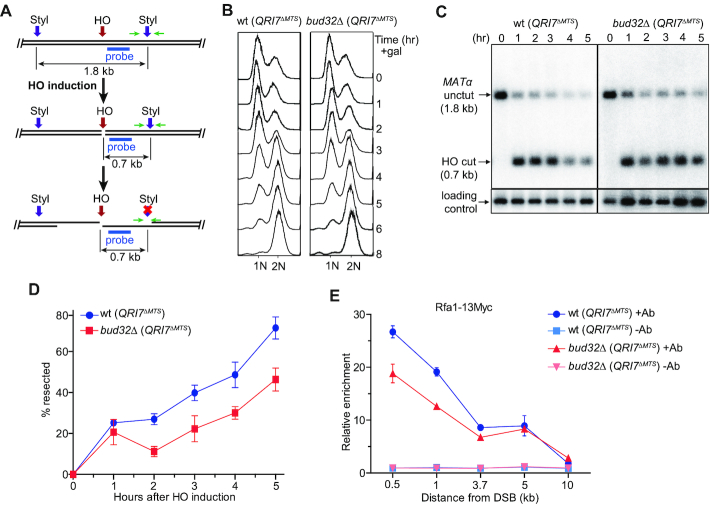

KEOPS promotes uncapped telomere resection and efficient DNA damage response (Figures 1E and 2), which prompted us to hypothesize that KEOPS plays a role in DNA end resection at DNA breaks. To measure DNA resection rate, we used a haploid yeast strain JKM179, in which a galactose-induced expression of homothallic switching endonuclease (HO) can introduce a specific DSB at the MATα site on chromosome III (Figure 3A) (58). Induction of the DSB at the MATα site resulted in G2/M arrest of cell cycle in both bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 3B) (59). We measured the DNA resection at the break site by detecting a StyI recognition site, which is located 0.7 kb away from the break end (Figure 3A). As resection proceeds, the DNA at the StyI site becomes single-stranded, and is resistant to StyI cleavage, leading to the disappearance of a 0.7 kb restriction fragment over time (Figure 3C). The ssDNA was also measured by real-time PCR as described previously (46). An obvious delay in end resection was observed in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells compared to wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 3C, D and Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that ssDNA generation at the HO-induced break is decreased in KEOPS mutant cells. To confirm this observation, we detected the enrichment of Rfa1, a subunit of RPA complex, to the break site by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay (45,60). The ChIP results showed that the enrichment of Rfa1 in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells was less than that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 3E), while the expression of Rfa1 was not affected by BUD32 deletion (Supplementary Figure S5A). We therefore concluded that the DNA end resection at DSB site is compromised in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells.

Figure 3.

BUD32 deletion impairs DNA end resection. (A) Schematic representation of ssDNA measurement by Southern blot and real-time PCR. Green arrow pair shows the primers used for real-time PCR. Cyan bar shows the location of probe used for hybridization. (B) FACS analysis of cell cycle progression. HO expression was induced in cells cultured to log-phase stage. Cell samples were taken every one hour and FACS was performed to analyze the cell cycle progression. (C) Southern blot analysis of StyI digested genomic DNA isolated from indicated strains collected at different time points. (D) Plot showing the percentage of resected DNA by real-time PCR. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). (E) Rfa1–13Myc enrichment at the HO-induced break site. ChIP assay with anti-Myc antibody (+Ab) or without anti-Myc antibody (–Ab) was performed to measure the recruitment of Rfa1–13Myc protein at DNA sites located 0.5, 1, 3.7, 5 and 10 kb away from the break. Results are fold enrichment when HO was induced for 2.5 hr over that at time 0 hr (n = 2).

KEOPS complex promotes HR

DNA resection is critical for DSB repair by HR. Now that KEOPS promotes DNA end resection, it could be important for HR repair of DNA breaks. To test the recombination rate in KEOPS deletion strains, we constructed a plasmid-mediated recombination system modified from a previously reported assay (Figure 4A) (61). A version of his3 gene, which lacks the start codon (his3-SC-), and harbors only part of promoter sequence, was inserted into a CEN plasmid. Between the promoter and open reading frame (ORF) of the his3-SC- gene, an EcoRI recognition site was inserted (Figure 4A). If the plasmid was linearized by EcoRI in vitro and introduced into BY4741 or BY4742 budding yeast strain, in which the genomic HIS3 gene is partially deleted (his3Δ1), the linearized plasmid could be repaired through HR using the genomic homology sequence of his3Δ1 as a donor sequence, resulting in functional restoration of HIS3 gene (Figure 4A). Thus, the cells carrying repaired HIS3 gene can survive in the medium lacking histidine (His–). As a control, no recombinants were obtained when the linearized his3-SC- plasmid was introduced into BY4742 rad52Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 4B). In contrast, 15–20% wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells transformed with linearized his3-SC- were able to grow in His– medium (Figure 4B), demonstrating the establishment of a Rad52-dependent HR assay. Notably, in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and kae1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) mutants, HR rate was significantly lower than that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 4B), indicating that KEOPS complex is important for efficient HR. We also employed a previously established ectopic recombination system (tGI354 yeast strain), in which a DSB introduced by HO cleavage at a MATa sequence on chromosome V is repaired by HR using a MATa-inc sequence on chromosome III as a template (Figure 4C) (49). The ectopic recombination rate was measured under the induction of HO expression by addition of galactose (49). Consistent with the results of plasmid-mediated HR assay, ectopic HR was reduced in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and kae1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) mutants compared with that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 4D), supporting the conclusion that KEOPS promotes efficient repair of DSB by HR.

KEOPS complex is associated with chromatin of break sites

In order to address whether the function of KEOPS complex in DNA processing and homologous recombination is direct, we examined the association of KEOPS with the chromatin in cells exposed to MMS. Both yeast whole cell extract (WCE) and chromatin were prepared. An immunoblotting analysis revealed that the chromatin fraction contained undetectable α-Tubulin (Figure 5A), indicative of successful chromatin fractionation (62). MMS treatment resulted in an increase of H2A phosphorylation in both whole cell extract and chromatin fraction, indicative of the activation of DNA damage response (Figure 5A). Bud32 was detected in the chromatin fraction of cells that were not exposed to MMS (Figure 5A). Notably, MMS exposure did not alter the overall protein level of Bud32 in whole cell extract, but led to an increase of Bud32 protein level in chromatin fraction (Figure 5A). These results are in line with previous data that the association of Cgi121 with chromatin is increased in yeast cells exposed to MMS (63), and suggest that KEOPS complex is recruited to chromatin when DNA damage occurs.

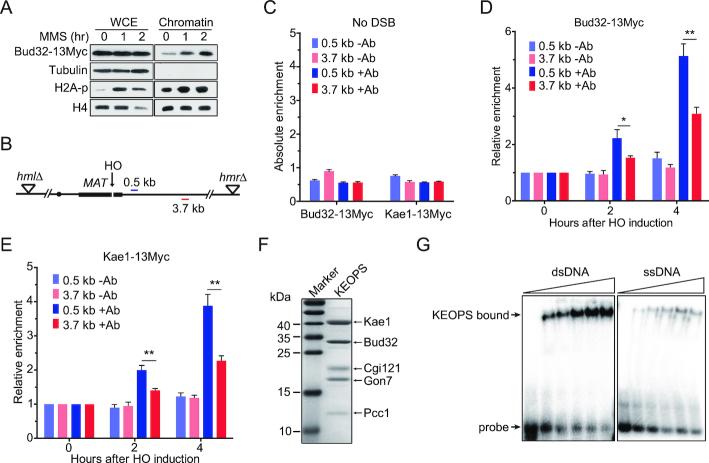

Figure 5.

KEOPS complex is recruited to the chromatin at DNA breaks. (A) Chromatin recruitment of Bud32 after MMS treatment. The chromatin was extracted from cells exposed to 0.05% MMS for indicated time points. The whole-cell extract (WCE) and chromatin-bound proteins were analyzed by western blot. (B) Schematic of the HO mediated DSB in the ‘donorless’ strain and real-time PCR primer sets on chromosome III. (C) The absolute fold enrichment of Bud32–13Myc and Kae1–13Myc at indicated distances from the HO recognition site in the absence of a DSB. –Ab and +Ab mean ChIP assay without and with anti-Myc antibody, respectively. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). (D, E) Relative fold enrichment of Bud32–13Myc (D) and Kae1–13Myc (E) at the indicated distances from the HO cleavage site after HO induction for indicated times. ChIP assays without antibody (–Ab) or with anti-Myc antibody (+Ab) were performed and real-time PCR was used to measure the enrichment. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.01 (Student's t-test). (F) SDS-PAGE and Commassie blue staining analysis of purified yeast KEOPS complex. (G) DNA binding ability analysis by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. 2 nM of radio-labeled dsDNA or ssDNA was incubated with purified yeast KEOPS proteins (0, 0.4, 0.7, 1.0, 1.4 and 1.8 μM).

To address whether KEOPS was recruited to the break sites, we measured the enrichment of both Bud32–13Myc and Kae1–13Myc at the DNA break induced by HO. Two DNA regions located 0.5- and 3.7-kb away from the DSB were examined by ChIP assay (Figure 5B). As a control, little binding of either Bud32–13Myc or Kae1–13Myc was detected at both the 0.5- and 3.7-kb sites when the DSB was not induced (Figure 5C). Following HO induction, the enrichment of Bud32–13Myc or Kae1–13Myc at the two sites increased over time (Figure 5D and E). Notably, the enrichment of both Bud32–13Myc and Kae1–13Myc at the 0.5-kb site was significantly higher than those at the 3.7-kb site (Figure 5D and E), suggesting that KEOPS is recruited to the chromatin surrounding break sites.

KEOPS complex modifies tRNA through direct binding to tRNA (36,64). We examined the DNA binding ability of KEOPS complex. We purified recombinant yeast KEOPS complex as previously described (Figure 5F) (43), and performed electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). The results revealed that KEOPS complex interacted with radiolabeled dsDNA and ssDNA in vitro (Figure 5G). We noted that the binding affinity for KEOPS-DNA interaction was comparable with that for KEOPS-tRNA interaction reported previously (36,64). Taken together, these results suggest that the function of KEOPS complex in DNA processing and homologous recombination is direct.

KEOPS provides some redundant activity in DNA resection in the absence of active MRX–Sae2

MRX complex and Sae2 are essential for the initiation of DNA end resection and HR repair of DSB (3,4). We asked whether the DNA end processing defect in KEOPS mutant is attributed to MRX dysfunction. The overall expression and recruitment of Mre11 at the DNA break in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells were determined, and no significant differences were observed (Figure 6A and Supplementary Figure S5A), suggesting that inactivation of KEOPS complex does not affect the action of MRX complex. We then examined the growth of bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS), mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells on regular medium or media containing genotoxic agents to investigate the genetic interaction between KEOPS and MRX. Intriguingly, the bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double mutant grew perceptively poorer than mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) single mutants on regular medium (Figure 6B). To determine whether the poorer growth of bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells was attributed to cell senescence induced by critical short telomeres, we examined the telomere length, and found that telomere length in bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain was shorter than that in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strains (Supplementary Figure S5B). Additionally, subtelomeric Y’ amplification, an indication of telomeric recombination as well as senescence, was not observed in bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Supplementary Figure S5B). In the presence of genotoxic agents, both bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and bud32Δ sae2Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double mutants exhibited a synthetic growth defect (Figure 6B, C and Supplementary Figure S5C), indicating that KEOPS and MRX-Sae2 act in different genetic pathways.

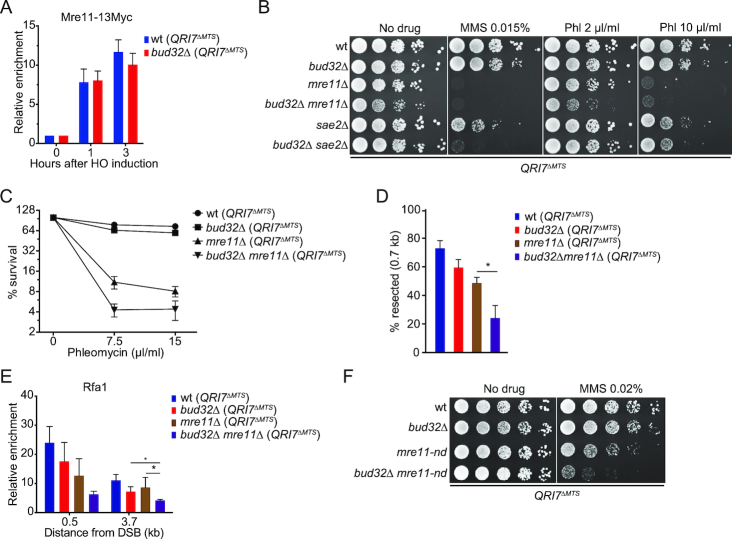

Figure 6.

KEOPS complex and MRX–Sae2 act in different pathways for DNA resection. (A) Recruitment of Mre11–13Myc at the HO induced beak site. ChIP assay was performed to analyze the enrichment of Mre11–13Myc at the DNA location of 0.5 kb away from the break. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). (B) Cell growth analysis. 10-fold serial dilutions of indicated strains were spotted on regular medium (no drug) or media containing methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) or phleomycin (Phl). (C) Quantitative analysis of phleomycin sensitivity. (D) Real-time PCR analysis of StyI digested genomic DNA isolated from indicated strains. DSB was induced in galactose medium for 3 hr. DNA located 0.7 kb away from the HO induced break was analyzed. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). * represents P < 0.05, (Student's t-test). (E) Enrichment of Rfa1 at the HO induced break site. HO expression was induced for 3 hr in indicated strains. Rfa1 specific antibody was used to perform ChIP analysis. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). * represents P < 0.05, (Student's t-test). (F) Genotoxic sensitivity analysis. Five-fold serial dilutions of indicated strains were spotted on regular medium (no drug) or medium containing MMS. mre11-nd means Mre11 nuclease-deficient mutation.

In order to confirm KEOPS affects DNA end resection independently of MRX, we measured the ssDNA generation at the HO-cut site by quantitative PCR in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS), mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) single- and their double-deletion strains. The result showed that severer deficiency in DNA resection was observed in bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double mutant (Figure 6D). Accordingly, further reduction of Rfa1 enrichment at the break was observed in bud32Δ mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain compared to bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and mre11Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strains (Figure 6E). These results consistently indicate that KEOPS and MRX have independent functions in ssDNA generation.

MRX complex has both endo- and exo-nuclease activity. mre11-H125N (mre11-nd) mutant is defective in nuclease activity (9,10). To examine whether KEOPS is required in the mre11 nuclease mutant, we compared the genotoxic sensitivity of mre11-H125N (mre11-nd) (QRI7ΔMTS), bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and bud32Δ mre11-nd (QRI7ΔMTS) strains. The results in Figure 6F and Supplementary Figure S5D revealed that bud32Δ mre11-nd (QRI7ΔMTS) double-mutation cells were more sensitive to genotoxic agents than either mre11-nd (QRI7ΔMTS) or bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) single mutant. These data further support the conclusion that the KEOPS provides some complementary activity for DNA resection in the absence of MRX nuclease activity.

KEOPS regulates the association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks

Dna2/Sgs1 plays a redundant role in DNA resection with MRX complex (9,10). Deletion of DNA2 or SGS1 in mre11 nuclease mutants aggravates the defect of DNA resection, as well as the sensitivity to ionizing radiation (9,10). We suspected that KEOPS complex may affect Dna2/Sgs1 at DNA breaks. To test this possibility, we measured the loading of Dna2 to the HO-induced break in the absence of active KEOPS. The results showed that in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain, Dna2 recruitment at the break was significantly reduced (Figure 7A), while the expression of Dna2 was not affected (Supplementary Figure S6A). These data indicate that KEOPS may function to promote the recruitment of Dna2 at DNA breaks. To further assess the genetic interaction between KEOPS and Dna2/Sgs1, we compared the genotoxic sensitivity of bud32Δ sgs1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double mutant, bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and sgs1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) single mutants. bud32Δ sgs1Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double mutant exhibited severer defect in genotoxic agent resistance than the corresponding single mutants (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure S6B). These results imply that KEOPS has function(s) other than affecting Dna2 recruitment. Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 are involved in two distinct pathways of extensive end processing following the initial end resection (3–5). We detected the recruitment of Exo1 at the break in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain, and found that lack of Bud32 also reduced the loading of Exo1 (Figure 7C), but has little effect on the protein level of Exo1 (Supplementary Figure S6C). Accordingly, a strain lacking both EXO1 and BUD32 was more sensitive to genotoxic agents than the strains lacking either EXO1 or BUD32 (Figure 7D and Supplementary Figure S6D). These data suggest that KEOPS affects both Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 pathways.

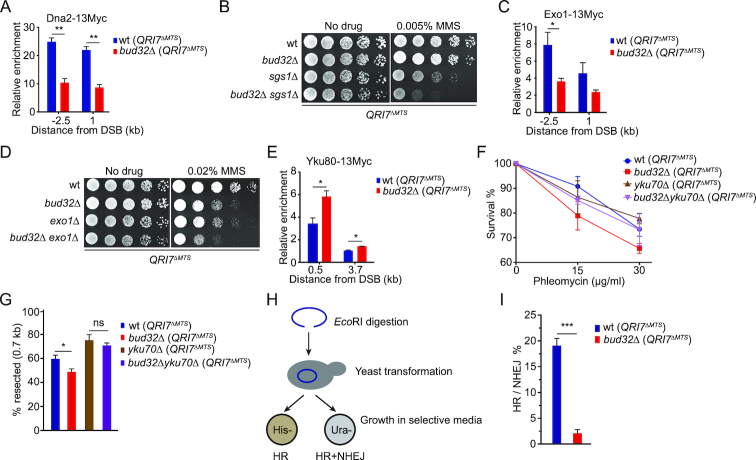

Figure 7.

KEOPS affects the association of Dna2, Exo1 and Yku complex with DNA breaks. (A) Recruitment of Dna2–13Myc at the HO induced DNA break. DSB was induced by 2% galactose for 2 hr and ChIP assay was performed with anti-Myc antibody. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). ** represents P < 0.01 (Student's t-test). (B) Cell growth analysis. Five-fold serial dilutions of indicated strains were spotted on normal medium (No drug) or medium containing MMS. (C) Recruitment of Exo1–13Myc at DNA breaks. DSB was induced for 2 hr and ChIP assay was performed with anti-Myc antibody. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). * represents P < 0.05, (Student's t-test). (D) MMS sensitivity analysis. Five-fold serial dilutions of indicated strains were spotted on normal medium (No drug) or medium containing MMS. (E) Recruitment of Ku80–13Myc at DNA breaks. DSB was induced for 3 hr and ChIP assay was performed with anti-Myc antibody. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). * represents P < 0.05, (Student's t-test). (F) Quantitative analysis of phleomycin sensitivity. (G) Real-time PCR analysis of StyI digested genomic DNA isolated from indicated strains. DSB was induced in galactose medium for 3 hr. The ssDNA at 0.7 kb away from the break was measured. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 4), ns represents no significance, * represents P < 0.05 (Student's t-test). (H) Schematic for the competition between HR and NHEJ. pRS316-his3-SC- plasmid shown in Figure 4A was linearized by EcoRI, which was followed by transformation into indicated cells. (I) Ratio of HR to NHEJ. The HR and NHEJ efficiencies were determined by the assay described in H. *** represents P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

Inactivation of KEOPS increases the association of Yku with DNA breaks

Due to the critical roles of Yku complex in DNA resection, we wondered whether KEOPS regulates the association of Yku at DNA breaks. The expression of Yku70/80 complex was not affected upon deletion of BUD32 (Supplementary Figure S7A). Then we examined the association of both Bud32 and Yku at the HO induced break in G1-arrested cells, in which little ssDNA is generated (1). The result showed that Bud32–13Myc was recruited to the break site, but not at the DNA locus 3.7 kb away from the beak site (Supplementary Figure S7B), while the recruitment of Yku was not affected in the absence of Bud32 in G1 phase (Supplementary Figure S7C). In asynchronized cells, the association of Yku80 with the breaks in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) mutant strain displayed a modest but statistically significant increase compared to that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) strain (Figure 7E), suggesting that KEOPS complex antagonizes the recruitment of Yku complex. Additionally, we deleted YKU70 in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) and bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strains, and found that bud32Δ yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain displayed less genotoxic sensitivity than bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain (Figure 7F and Supplementary Figure S7D). Moreover, DNA end resection efficiency in bud32Δ yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells was comparable to that in yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) cells, but higher than those in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and wt (QRI7ΔMTS) cells (Figure 7G). These data are consistent with the notion that KEOPS promotes the association of Dna2 and Exo1, and antagonizes Yku binding. However, we also noted that the bud32Δ yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) double-deletion mutant showed poorer growth than bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) and yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strains on normal medium (Supplementary Figure S7D), indicating additional unknown functions of KEOPS in cell growth.

Since the loading of Yku complex to the DNA break was increased in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) mutant, we reasoned that NHEJ-mediated repair of DSB might be improved. We used the JKM179 yeast strain to analyze the NHEJ efficiency as previously described (65). Because both the HMR and HML homologous donor sequences of MAT site in this strain are deleted (Supplementary Figure S7E), the DSB induced by HO cleavage can be repaired exclusively by NHEJ (66). The HO expression was induced in galactose medium for 1 hr, and then turned off by addition of glucose (Supplementary Figure S7F). The rejoining efficiency of DSBs was measured by quantitative PCR after cells were cultured in glucose medium for 2.5 and 5 hr (Supplementary Figure S7F). Little rejoining of DSBs was detected in yku70Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain (Supplementary Figure S7F), confirming that the rejoining is NHEJ-dependent. The rejoining efficiency in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain was significantly higher than that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) strain when the cells were cultured in glucose medium for 2.5 and 5 hr (Supplementary Figure S7F). We then evaluated both HR and NHEJ efficiencies using the plasmid system shown in Figure 4A. The plasmid his3-SC- (ARS-CEN, URA3) was linearized by EcoRI and introduced into wt (QRI7ΔMTS) or bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) strain. The transformants of each sample were equally divided into two groups, which were grown on solid media lacking histidine (His–) and uracil (Ura-), respectively (Figure 7H). The transformants grown on His– medium were outcomes of HR (His+), while the transformants grown on Ura- medium were outcomes of HR and NHEJ (Ura+) (Figure 7H). The competition between HR and NHEJ was represented as the ratio of HR transformants (His+) to NEHJ transformants that were only grown on Ura- medium (His−/Ura+). The results showed that the ratio of HR to NHEJ in bud32Δ (QRI7ΔMTS) was much lower than that in wt (QRI7ΔMTS) (Figure 7I), indicating that NHEJ pathway is much more favored than HR pathway when BUD32 is absent.

DISCUSSION

In budding yeast, KEOPS complex plays multiple roles, including promoting telomere uncapping and elongation (27), facilitating the expression of inducible genes (29), and catalyzing tRNA t6A modification (33,34). In this work, we have explored the role of KEOPS complex in DSB repair, and found that KEOPS complex promotes the DNA resection of break ends to facilitate HR mediated DNA repair.

BUD32, KAE1, PCC1 and GON7 had been considered as essential genes because their individual deletion mutants grow extremely slow, raising technical challenges for functional study of these genes (67). The severe slow growth of KEOPS mutants appears to be resulted from the defect of tRNA t6A modification because Qri7ΔMTS overexpression recovers the cell growth and t6A modification in KEOPS subunit null strains (Figure 1A) (33,40,41). In contrast, Qri7ΔMTS overexpression could not rescue telomere length defect (Supplementary Figure S2) (33,40,41), nor affects the temperature resistance of KEOPS subunit null cdc13-1 cells (Figure 1E). These lines of evidence distinguish the roles of KEOPS in telomere maintenance form that in tRNA t6A modification (41).

The recovery of cell growth of KEOPS mutant(s) by ectopic expression of Qri7ΔMTS has provided essential genetic tools for further functional study of KEOPS genes in DNA damage repair. KEOPS subunit deletion cells are more sensitive to several genotoxic agents, including phleomycin, MMS and HU than wild type cells (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S3A). In addition, the phosphorylation of Rad53 seen in genotoxin-treated wild type cells are compromised in bud32Δ mutant (Figure 2F and G). Moreover, DNA end resection of DSBs is delayed and reduced in bud32Δ cells (Figure 3C-E and Supplementary Figure S4). Consistently, bud32Δ and kae1Δ mutant cells display significantly lower HR rate than wild type cells (Figure 4B and D). These data strongly support the conclusion that KEOPS plays a positive role in regulating DNA end resection, and thereby promotes DNA damage response and efficient HR repair of DSB.

KEOPS complex has intrinsic DNA and RNA binding activity in vitro (Figure 5G) (36,64). It also associates with chromatin in vivo (Figure 5A), including telomeres (27). Moreover, more Bud32, Kae1 and Cgi121 are recruited to the break sites of chromatin upon DNA damage occurring (Figure 5A-E) (63). These results indicate that the function of KEOPS in DSB response and repair is direct. Given that the phenotypes of single subunit deletion mutant are almost the same as those of the others, we favor the notion that the KEOPS subunits, Bud32, Kae1, Pcc1, Gon7 and Cgi121 need to form an intact complex to fully fulfil their functions. Bud32 exhibits ATPase/kinase activity, which is required for the function of KEOPS in DNA damage repair (Figure 2B), it remains possible that KEOPS affects telomere replication and DSB repair through phosphorylating proteins associated with telomeres and DNA breaks. However, the observation that the ATPase/kinase activity of Bud32 is suppressed by Kae1 when they form a complex seems to argue against this hypothesis (55,56).

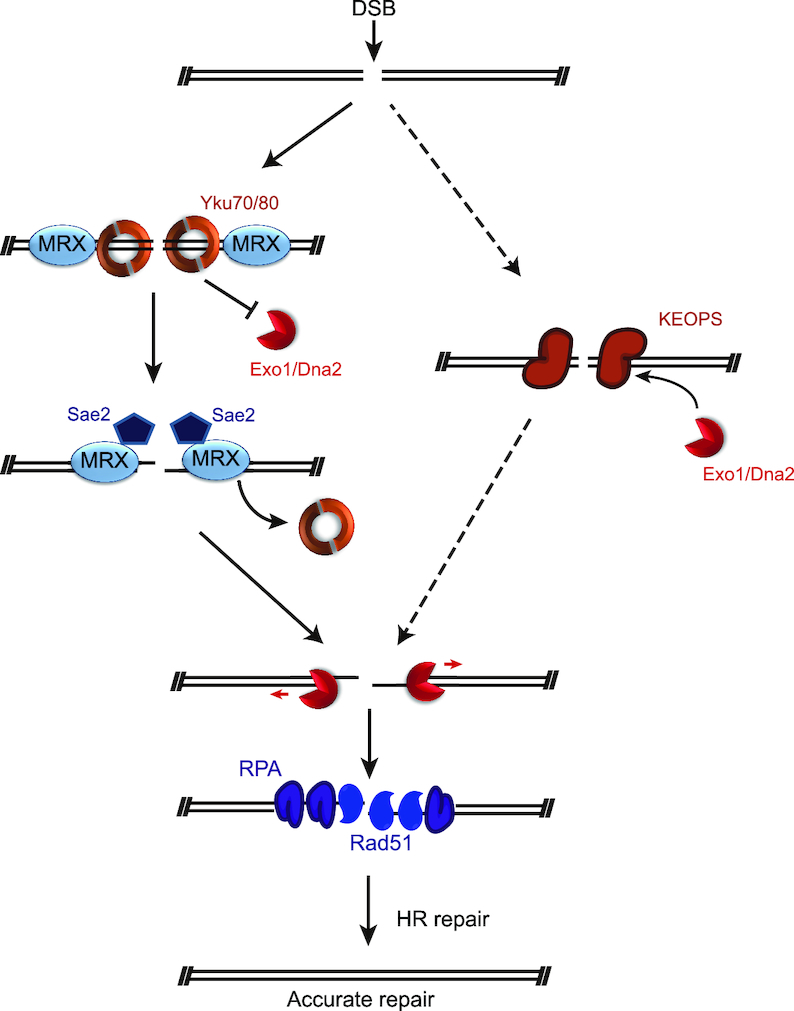

It has been well documented that DSBs are primarily and timely sensed by Yku and MRX complex (68). Yku complex prevents Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 from access to break ends, and promotes NHEJ (9,10). MRX in combination with Sae2 functions as an endonuclease complex, and cleaves the 5′-terminated break ends to remove the proteins (e.g. Yku70/80) that block DNA ends (6–8), and thus promotes the recruitment of Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 (9,10). Interestingly, simultaneous inactivation of both MRX–Sae2 and KEOPS results in an elevated synthetic sensitivity to genotoxic agents (Figure 6B, C and Supplementary Figure S5C), as well as an additive reduction of DNA end resection (Figure 6D and E), indicating that KEOPS complex and MRX independently regulate end resection. Consistently, KEOPS is critical for genotoxic resistance when the nuclease activity of MRX is abrogated (Figure 6F and Supplementary Figure S5D). Whether KEOPS complex has endonuclease activity is unknown. But inactivation of KEOPS complex leads to reduced enrichment of Dna2 and Exo1 (Figure 7A and C), and increased recruitment of Yku at DNA breaks (Figure 7E). Based on the data mentioned above, we propose a model that KEOPS may function as a sensor for DSB. KEOPS promotes the recruitment of Dna2 and Exo1, and suppresses Yku at DSBs (Figure 8). It is of note that the ChIP results of the spatio-temporal recruitment of KEOPS (Bud32 and Kae1) at the HO-induced break displays a modest delay (Figure 5D and E). These data argue that KEOPS seems not to be an ‘early’ sensor. However, a quick enrichment of Bud32 at chromatin is observed when cells are exposed to MMS (Figure 5A), suggesting an urgent requirement of KEOPS upon DNA damage, such as MMS treatment. Therefore, we contend that compared to MRX, KEOPS likely functions as a complementary sensor of DSBs, and it becomes indispensable when MRX is not present or not enough to deal with massive DNA damage.

Figure 8.

Model depicting the function of KEOPS at DSB. When a DSB occurs, In addition to Yku70/80 and MRX, KEOPS complex also functions as a sensor, and is recruited to the break sites. The binding of Yku complex prevents the access of Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 to DNA breaks. The binding of MRX–Sae2 and KEOPS antagonizes excess Yku binding and promotes the recruitment of Exo1 and Dna2/Sgs1 to process the break ends to generate long ssDNA. Then Rad51 replaces RPA complex to mediate homologous template searching and repair of DSB.

Given that KEOPS complex is conserved across eukaryotes, whether KEOPS complex participates in DNA damage repair in other species is a fascinating question. All the KEOPS subunits are detected in both the cytoplasm and nucleus in human cell lines (69,70). Additionally, direct physical interactions between human KEOPS subunits and DNA-repair protein PARP1 are detected (69). Knockdown of human KEOPS complex subunits OSGEP (Kae1 ortholog), TP53RK (Bud32 ortholog), or TPRKB (Cgi121 ortholog) results in genomic instability, though the molecular mechanism is still unclear (69). Recent studies show that mutations of human KEOPS complex genes lead to nephrotic syndrome with primary microcephaly (also named as Galloway-Mowat syndrome), which is considered as a DDR-defective syndrome, in several familial cases (69,71–73). These lines of evidence suggest that the function of KEOPS complex in DNA damage response and repair may be conserved across species, and harbors physiologic significance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr James E. Haber (Brandeis University, USA), Dr H. van Tilbeurgh (Université Paris-Sud, France), Dr Xuefeng Chen (Wuhan University, China) and Dr Huiqiang Lou (China Agricultural University, China) for strains and plasmids, Dr Heidi Feldmann (University of Munich, Germany) for Yku70 antibody, Dr Junhong Han (Sichuan University, China), Dr. Fei-long Meng (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, CAS, China) and members of Zhou lab for the help, discussions and suggestions for this project.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) [2016YFA0500701]; Chinese Academy of Sciences [XDB19000000]; National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [31230040/31461143003]. Funding for open access charge: Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) [2016YFA0500701]; National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [31230040/31461143003]; Chinese Academy of Sciences [XDB19000000].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chiruvella K.K., Liang Z., Wilson T.E.. Repair of double-strand breaks by end joining. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013; 5:a012757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deriano L., Roth D.B.. Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013; 47:433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S.. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008; 455:770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu Z., Chung W.H., Shim E.Y., Lee S.E., Ira G.. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008; 134:981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gravel S., Chapman J.R., Magill C., Jackson S.P.. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:2767–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cannavo E., Cejka P.. Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks. Nature. 2014; 514:122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang W., Daley J.M., Kwon Y., Krasner D.S., Sung P.. Plasticity of the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2-Sae2 nuclease ensemble in the processing of DNA-bound obstacles. Genes Dev. 2017; 31:2331–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reginato G., Cannavo E., Cejka P.. Physiological protein blocks direct the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 nuclease complex to initiate DNA end resection. Genes Dev. 2017; 31:2325–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shim E.Y., Chung W.H., Nicolette M.L., Zhang Y., Davis M., Zhu Z., Paull T.T., Ira G., Lee S.E.. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 2010; 29:3370–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S.. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 2010; 29:3358–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gobbini E., Cassani C., Vertemara J., Wang W., Mambretti F., Casari E., Sung P., Tisi R., Zampella G., Longhese M.P.. The MRX complex regulates Exo1 resection activity by altering DNA end structure. EMBO J. 2018; 37:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levikova M., Pinto C., Cejka P.. The motor activity of DNA2 functions as an ssDNA translocase to promote DNA end resection. Genes Dev. 2017; 31:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller A.S., Daley J.M., Pham N.T., Niu H., Xue X., Ira G., Sung P.. A novel role of the Dna2 translocase function in DNA break resection. Genes Dev. 2017; 31:503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zou L., Elledge S.J.. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003; 300:1542–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jasin M., Rothstein R.. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013; 5:a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Symington L.S., Rothstein R., Lisby M.. Mechanisms and regulation of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2014; 198:795–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pfingsten J.S., Goodrich K.J., Taabazuing C., Ouenzar F., Chartrand P., Cech T.R.. Mutually exclusive binding of telomerase RNA and DNA by Ku alters telomerase recruitment model. Cell. 2012; 148:922–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lopez C.R., Ribes-Zamora A., Indiviglio S.M., Williams C.L., Haricharan S., Bertuch A.A.. Ku must load directly onto the chromosome end in order to mediate its telomeric functions. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7:e1002233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin J.J., Zakian V.A.. The Saccharomyces CDC13 protein is a single-strand TG1-3 telomeric DNA-binding protein in vitro that affects telomere behavior in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996; 93:13760–13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diede S.J., Gottschling D.E.. Exonuclease activity is required for sequence addition and Cdc13p loading at a de novo telomere. Curr. Biol. 2001; 11:1336–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gravel S., e M.L., Labrecque P., Wellinger R.J.. Yeast ku as a regulator of chromosomal DNA end structure. Science. 1998; 280:741–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garvik B., Carson M., Hartwell L.. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995; 15:6128–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maringele L., Lydall D.. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70 Delta mutants. Gene Dev. 2002; 16:1919–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lydall D., Weinert T.. Use of cdc13-1-induced DNA damage to study effects of checkpoint genes on DNA damage processing. Method Enzymol. 1997; 283:410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grandin N., Damon C., Charbonneau M.. Cdc13 prevents telomere uncapping and Rad50-dependent homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2001; 20:6127–6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zubko M.K., Guillard S., Lydall D.. Exo1 and Rad24 differentially regulate generation of ssDNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 mutants. Genetics. 2004; 168:103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Downey M., Houlsworth R., Maringele L., Rollie A., Brehme M., Galicia S., Guillard S., Partington M., Zubko M.K., Krogan N.J. et al.. A Genome-Wide Screen Identifies the Evolutionarily Conserved KEOPS Complex as a Telomere Regulator. Cell. 2006; 124:1155–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Addinall S.G., Downey M., Yu M., Zubko M.K., Dewar J., Leake A., Hallinan J., Shaw O., James K., Wilkinson D.J. et al.. A genomewide suppressor and enhancer analysis of cdc13-1 reveals varied cellular processes influencing telomere capping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008; 180:2251–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kisseleva-Romanova E., Lopreiato R., Baudin-Baillieu A., Rousselle J.C., Ilan L., Hofmann K., Namane A., Mann C., Libri D.. Yeast homolog of a cancer-testis antigen defines a new transcription complex. EMBO J. 2006; 25:3576–3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu Y., Tang H.B., Liu N.N., Tong X.J., Dang W., Duan Y.M., Fu X.H., Zhang Y., Peng J., Meng F.L. et al.. Telomerase-null survivor screening identifies novel telomere recombination regulators. PLoS Genet. 2013; 9:e1003208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng J., He M.H., Duan Y.M., Liu Y.T., Zhou J.Q.. Inhibition of telomere recombination by inactivation of KEOPS subunit Cgi121 promotes cell longevity. PLoS Genet. 2015; 11:e1005071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fu X.H., Duan Y.M., Liu Y.T., Cai C., Meng F.L., Zhou J.Q.. Telomere recombination preferentially occurs at short telomeres in telomerase-null type II survivors. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e90644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. El Yacoubi B., Hatin I., Deutsch C., Kahveci T., Rousset J.P., Iwata-Reuyl D., Murzin A.G., de Crecy-Lagard V.. A role for the universal Kae1/Qri7/YgjD (COG0533) family in tRNA modification. EMBO J. 2011; 30:882–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Srinivasan M., Mehta P., Yu Y., Prugar E., Koonin E.V., Karzai A.W., Sternglanz R.. The highly conserved KEOPS/EKC complex is essential for a universal tRNA modification, t6A. EMBO J. 2011; 30:873–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El Yacoubi B., Lyons B., Cruz Y., Reddy R., Nordin B., Agnelli F., Williamson J.R., Schimmel P., Swairjo M.A., de Crecy-Lagard V.. The universal YrdC/Sua5 family is required for the formation of threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:2894–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perrochia L., Crozat E., Hecker A., Zhang W., Bareille J., Collinet B., van Tilbeurgh H., Forterre P., Basta T.. In vitro biosynthesis of a universal t6A tRNA modification in Archaea and Eukarya. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:1953–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meng F.L., Chen X.F., Hu Y., Tang H.B., Dang W., Zhou J.Q.. Sua5p is required for telomere recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Res. 2010; 20:495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meng F.L., Hu Y., Shen N., Tong X.J., Wang J., Ding J., Zhou J.Q.. Sua5p a single-stranded telomeric DNA-binding protein facilitates telomere replication. EMBO J. 2009; 28:1466–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daugeron M.C., Lenstra T.L., Frizzarin M., El Yacoubi B., Liu X., Baudin-Baillieu A., Lijnzaad P., Decourty L., Saveanu C., Jacquier A. et al.. Gcn4 misregulation reveals a direct role for the evolutionary conserved EKC/KEOPS in the t6A modification of tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:6148–6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wan L.C.K., Mao D.Y.L., Neculai D., Strecker J., Chiovitti D., Kurinov I., Poda G., Thevakumaran N., Yuan F., Szilard R.K. et al.. Reconstitution and characterization of eukaryotic N6-threonylcarbamoylation of tRNA using a minimal enzyme system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:6332–6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu Y.Y., He M.H., Liu J.C., Lu Y.S., Peng J., Zhou J.Q.. Yeast KEOPS complex regulates telomere length independently of its t(6)A modification function. J. Genet. Genomics. 2018; 45:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Longtine M.S., McKenzie A., 3rd Demarini, Shah D.J., Wach N.G., Brachat A., Philippsen A., Pringle J.R.. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998; 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Collinet B., Friberg A., Brooks M.A., van den Elzen T., Henriot V., Dziembowski A., Graille M., Durand D., Leulliot N., Saint Andre C. et al.. Strategies for the structural analysis of multi-protein complexes: lessons from the 3D-Repertoire project. J. Struct. Biol. 2011; 175:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Driller L., Wellinger R.J., Larrivée M., Kremmer E., Jaklin S., Feldmann H.M.. A short C-terminal domain of Yku70p is essential for telomere maintenance. J. Biol. Chem. 2000; 275:24921–24927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen H., Lisby M., Symington L.S.. RPA coordinates DNA end resection and prevents formation of DNA hairpins. Mol. Cell. 2013; 50:589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zierhut C., Diffley J.F.. Break dosage, cell cycle stage and DNA replication influence DNA double strand break response. EMBO J. 2008; 27:1875–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peng J., Zhou J.-Q.. The tail-module of yeast Mediator complex is required for telomere heterochromatin maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 40:581–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou J., Zhou B.O., Lenzmeier B.A., Zhou J.Q.. Histone deacetylase Rpd3 antagonizes Sir2-dependent silent chromatin propagation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:3699–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ira G., Malkova A., Liberi G., Foiani M., Haber J.E.. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003; 115:401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kulak N.A., Pichler G., Paron I., Nagaraj N., Mann M.. Minimal, encapsulated proteomic-sample processing applied to copy-number estimation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Methods. 2014; 11:319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nugent C.I., Bosco G., Ross L.O., Evans S.K., Salinger A.P., Moore J.K., Haber J.E., Lundblad V.. Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr. Biol. 1998; 8:657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Longhese M.P. DNA damage response at functional and dysfunctional telomeres. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mattarocci S., Reinert J.K., Bunker R.D., Fontana G.A., Shi T., Klein D., Cavadini S., Faty M., Shyian M., Hafner L. et al.. Rif1 maintains telomeres and mediates DNA repair by encasing DNA ends. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017; 24:588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu Z., Liu J., Zhang Q.D., Lv D.K., Wu N.F., Zhou J.Q.. Rad6-Bre1-mediated H2B ubiquitination regulates telomere replication by promoting telomere-end resection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:3308–3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mao D.Y., Neculai D., Downey M., Orlicky S., Haffani Y.Z., Ceccarelli D.F., Ho J.S., Szilard R.K., Zhang W., Ho C.S. et al.. Atomic structure of the KEOPS complex: an ancient protein kinase-containing molecular machine. Mol. Cell. 2008; 32:259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hecker A., Lopreiato R., Graille M., Collinet B., Forterre P., Libri D., van Tilbeurgh H.. Structure of the archaeal Kae1/Bud32 fusion protein MJ1130: a model for the eukaryotic EKC/KEOPS subcomplex. EMBO J. 2008; 27:2340–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang W., Collinet B., Graille M., Daugeron M.C., Lazar N., Libri D., Durand D., van Tilbeurgh H.. Crystal structures of the Gon7/Pcc1 and Bud32/Cgi121 complexes provide a model for the complete yeast KEOPS complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:3358–3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Holmes A., Haber J.E.. Physical monitoring of HO-induced homologous recombination. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999; 113:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee S.E., Moore J.K., Holmes A., Umezu K., Kolodner R.D., Haber J.E.. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998; 94:399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barlow J.H., Lisby M., Rothstein R.. Differential regulation of the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks in G1. Mol. Cell. 2008; 30:73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Silberman R., Kupiec M.. Plasmid-mediated induction of recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1994; 137:41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ruthemann P., Balbo Pogliano C., Codilupi T., Garajova Z., Naegeli H.. Chromatin remodeler CHD1 promotes XPC-to-TFIIH handover of nucleosomal UV lesions in nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 2017; 36:3372–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim D.R., Gidvani R.D., Ingalls B.P., Duncker B.P., McConkey B.J.. Differential chromatin proteomics of the MMS-induced DNA damage response in yeast. Proteome Sci. 2011; 9:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Perrochia L., Guetta D., Hecker A., Forterre P., Basta T.. Functional assignment of KEOPS/EKC complex subunits in the biosynthesis of the universal t6A tRNA modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:9484–9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tao R., Chen H., Gao C., Xue P., Yang F., Han J.D., Zhou B., Chen Y.G.. Xbp1-mediated histone H4 deacetylation contributes to DNA double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell Res. 2011; 21:1619–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moore J.K., Haber J.E.. Cell cycle and genetic requirements of two pathways of nonhomologous end-joining repair of double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996; 16:2164–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Giaever G., Chu A.M., Ni L., Connelly C., Riles L., Veronneau S., Dow S., Lucau-Danila A., Anderson K., Andre B. et al.. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002; 418:387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Symington L.S., Gautier J.. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011; 45:247–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Braun D.A., Rao J., Hildebrandt F.. Mutations in KEOPS-complex genes cause nephrotic syndrome with primary microcephaly. Nat. Genet. 2017; 49:1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wan L.C., Maisonneuve P., Szilard R.K., Lambert J.P., Ng T.F., Manczyk N., Huang H., Laister R., Caudy A.A., Gingras A.C. et al.. Proteomic analysis of the human KEOPS complex identifies C14ORF142 as a core subunit homologous to yeast Gon7. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hyun H.S., Kim S.H., Park E., Cho M.H., Kang H.G., Lee H.S., Miyake N., Matsumoto N., Tsukaguchi H., Cheong H.I.. A familial case of Galloway-Mowat syndrome due to a novel TP53RK mutation: a case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2018; 19:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Edvardson S., Prunetti L., Arraf A., Haas D., Bacusmo J.M., Hu J.F., Ta-Shma A., Dedon P.C., de Crecy-Lagard V., Elpeleg O.. tRNA N6-adenosine threonylcarbamoyltransferase defect due to KAE1/TCS3 (OSGEP) mutation manifest by neurodegeneration and renal tubulopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017; 25:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. O’Driscoll M., Jeggo P.A.. The role of the DNA damage response pathways in brain development and microcephaly: insight from human disorders. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2008; 7:1039–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.