Abstract

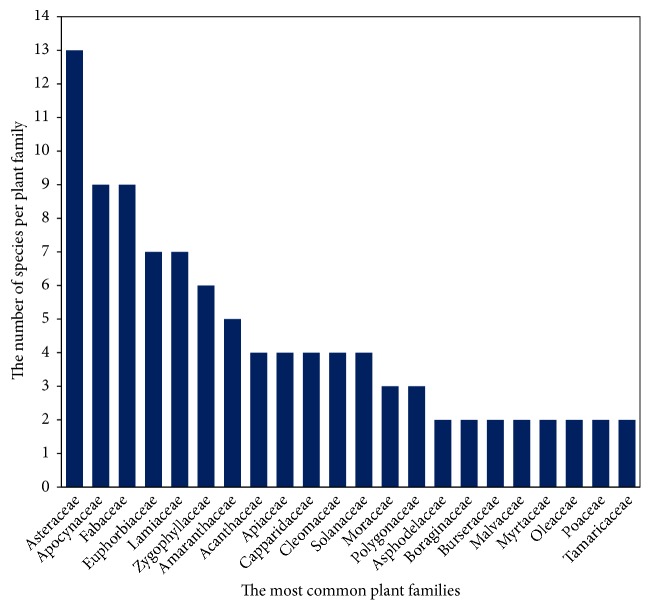

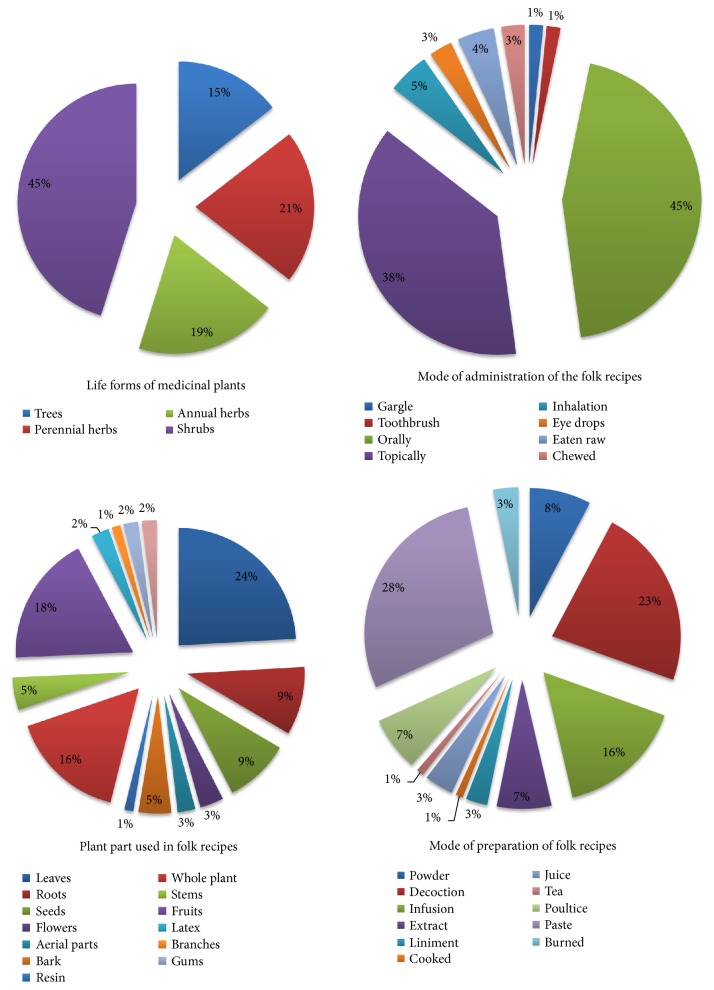

For a long time, the people of Saudi Arabia have been using medicinal plants (MPs) as conventional medicine to heal diverse human and livestock diseases. The present work is the first study on ethnobotanical uses of 124 MPs species used by the local tribal communities of Jazan province in the Southwest of Saudi Arabia. Ethnobotanical data were collected by interviewing 174 local informants using semistructured interviews. Informants of different ages, from several settlements belonging to several tribal communities, were interviewed. It is worth noticing that the age of informants and their knowledge of MPs were positively correlated, whereas the educational level and MP knowledge of participants were negatively correlated. To find out if there was agreement in the use of certain plants in the treatment of given ailments, we used Informant Consensus Factor (ICF). To determine the most frequently used plant species for treating a particular ailment category by local people we used the fidelity level (FL%). The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) was used to indicate the local importance of a species and the relative importance (RI) level was used to check the therapeutic potentials of the cited plants. A total of 124 MPs belonging to 103 genera and 48 families were collected and identified. The majority of these plants were shrubs (45%), perennial herbs (21%), annual herbs (19%), or trees (18%). The Asteraceae (10.48%), Fabaceae (7.25%), and Apocynaceae (7.25%) families were the most represented. Leaves, fruits, and whole plant (24%, 18%, and 16%, respectively) were the most used plant parts in formulating traditional medicines. Ziziphus spina-christi and Calotropis procera with the highest RI level (2.0) were found to have the highest range of therapeutic uses. They were followed by Datura stramonium (1.86), Withania somnifera, and Aloe vera (1.81). The ICF ranged from 0.02 to 0.42 covering 12 disease categories with a prevalence of disease categories related to skin and hair problems (ICF=0.42) having 75 species cited, while 73 species were cited for gastrointestinal tract (GIT) disorders (ICF = 0.40). Senna alexandrina (67%), Tribulus terrestris (64%), Pulicaria undulata (60%), Leptadenia pyrotechnica (55%), and Rumex nervosus (55%) had the highest FL which indicates their good healing potential against specific diseases. The high-FL species are the most promising candidate plants for in-depth pharmacological screening and merit further consideration. Accordingly, Jazan flora has good ethnobotanical potential. Unfortunately, many MP species are endangered by drought, overgrazing, and overexploitation. Some protection measures should be undertaken to prevent these species from becoming extinct. Natural reserves and wild nurseries are typical settings to retain medically important plants in their natural habitats, while botanic gardens and seed banks are important paradigms for ex situ conservation.

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, people of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Peninsula, in general, have been using medicinal plants (MPs) to heal various human and livestock diseases. This special relationship with the flora continues to this day as people still rely heavily on traditional medicine to meet their healthcare needs [1, 2]. In fact, traditional Arab and Islamic medicine is a well-known system of healing in many Arab and Islamic countries going back to ancient times. This traditional medicine refers to healing practices, beliefs, and philosophy integrating herbal medicines, spiritual therapies, dietary practices, mind-body practices, and manual techniques, applied singularly or in combination to treat, diagnose, and prevent illnesses and/or maintain well-being [3]. Furthermore, this healing system reflects a permanent interconnectivity between Islamic medical practice and Prophetic guidance (Hadith), as well as regional healing practices emerging from specific geographical and cultural origins [3]. For instance the healing practices vary considerably from country to country and region to region, as they are influenced by factors such as local flora diversity, culture/ subcultures, history, personal attitudes, and philosophy [3].

Saudi Arabia occupies the largest part of the Arab Peninsula which is dominated by desert. Geographically, it is characterized by a variety of habitats including mountains, valleys, lava fields, meadows, and rocky deserts. It is made up of two zones: the rain fed zones of the western and southwestern highlands and the arid region of the interior area [50, 52]. The eastern part comprises large swaths of land covered with sand dunes and lower mountains and plains (deserts). The Asir highlands as well as the southwestern highlands that stretch parallel to the Red Sea constitute a flowing series of cliffs extending far in to Yemen. Most of the forests (about 2.7 million hectares) are found in the southwestern highlands [2, 13] where vegetation is closely related to that of Yemen and East African countries such as Ethiopia and Eritrea [52]. These forests remained under a system of tribal protection since ancient times, when they were an important source of timber used in the manufacture of ceilings of the buildings, doors, and windows and agriculture tools. They were also the main source of firewood and charcoal and grazing surface for the herds. Most of the population of the region is ethnically Arab and is made mainly of tribal communities; therefore the use of MPs is the central part of the diversity of cultures in the country which resulted in the heterogeneity of the conventional healing system. Traditional healers are the primary providers of traditional therapies but professional practitioners were recently licensed in Saudi Arabia to practice cupping therapy [53].

The flora of Saudi Arabia offers a rich reserve of MP species for folk medicine and some of them are endemic [2, 20]. Such flora of the desert, semidesert, and mountainous ecosystems has several elements of the Palaearctic (Europe and Asia), Afrotropical (Africa south of the Sahara), and Indo-Malayan terrestrial realms [1, 2]. Hence, the region has been considered as a natural reservoir for the collection of wild MPs; about 600 species (27% of the flora) are actually used in traditional healing systems or were reported to have medicinal value [2, 20]. The southwestern region is the richest in terms of species diversity and also holds the largest number of endemic species [4]. Most of the species are found in the mountains chains highly occupied with human settlements from ancient times [2, 13]. The use of MPs by the local tribal communities and traditional healers (Hakim or Tib Arabi) in these regions goes back thousands of years and still plays a major role in people's culture and therefore accounts for the accumulation of outstanding traditional knowledge (TK) in the region [4, 54]. In spite of the presence of modern hospitals and well-trained medical staff, local communities still use MPs as an alternative to allopathic medicine to deal with several routine maladies and chronic diseases including skin-related diseases, rheumatism, bone fracture, asthma, diabetes, stomach problems, constipation, respiratory tract infections, eye and ear problems, colds, fever, measles, bladder and urinary diseases, liver and spleen disorders, typhoid, toothache, epilepsy, tuberculosis, hypertension, anaemia, nervous problems, scorpion stings, and snake bites as well as several tropical diseases such as leishmaniosis, malaria, rift valley fever, and schistosomiasis. In particular, tropical diseases and scorpion stings and snake bites are a health and socioeconomic problems in Saudi Arabia and many other tropical and subtropical countries [55, 56].

Gathering and processing MPs for domestic use or for selling is common in Saudi Arabia [2, 20]. Unfortunately, overexploitation of these MPs and the conversion of natural habitats to cropland have critically reduced the size of common MPs communities and their economic contribution to local communities [2, 21]. Furthermore, the number of resource persons with knowledge on the use of local MPs is fast decreasing among rural communities whose very existence is now under the threat of rapid urbanization taking place in the Arabian Peninsula like in much of the developing world. Therefore, scientific ethnobotanical studies have to be undertaken on the largest scale possible as recommended by the WHO [57] to preserve this fast vanishing knowledge. In Saudi Arabia, most of the studies on herbal medicines were partial and fragmentary [4, 7, 10, 21, 23]. Still, very little are the documents that detailed the folk medicine in southwestern regions of the country. Documenting the TK on MPs of Jazan region in particular still needs more work to avoid losing this knowledge. The present work, being the first collection and listing of all existing data on MPs used by the local tribal communities of Jazan region, provides the first ethnomedicinal and cultural assessment of these species. The study area is ethnobotanically unexplored and rich in plants resources. The aim of the study was to (i) document the knowledge and the uses of wild plants in folk system of Arab and Islamic medicine for treating human health related ailments, including plant local names, method of preparation, plant part(s) used, and application; (ii) analyse the outstanding traditional knowledge of local tribal communities of Jazan region specifically with regard to gender, age and geographical origin of the informants; (iii) determine the most common ailment categories and plant species used for treating different ailments in the study area; (iv) find out the highest diversity of medicinal uses of a plant using relative importance (RI) value. We addressed our aims by documenting various uses of MPs from Jazan region and then analysing the data using indices such as Informant consensus factor (ICF), relative frequency citation (RFC), fidelity level (FL%), and RI level to check the level of consensus within a community and the potential uses of the cited plants. Our findings may help for future research to investigate new derivative used as medicines and also manufacture natural health products. We hope it will help in preserving TK and contribute to the conservation of biodiversity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Jazan province is located in the southwest corner of Saudi Arabia and directly north of the border with Yemen between 16°20' N to 17°40'N and 41°55'E to 43°20'E (Figure 1). It is one of the smallest administrative districts of the country; the total area of the region is estimated to 11,670 km2 in addition to around 80 islands in the Red Sea, of which the largest is Farasan, covering around 752 km2. The study area is bordered from the south by the north-western frontier regions of Yemen (120 km border) and from the north by the town of Ash-Shuqaiq and from the east by the eastern slopes of Fyfa Mountains (part of Al-Sarawat mountain range that runs parallel to the western coast of the Arabian Peninsula). The region has about 260-km-long coastal area on the western side. Farasan islands, 40 km off the coast of Jazan, were also included the study area. The main cities of Jazan region are Jazan, Sabya, Abou-arish, Al-darb, Ash-Shuqaiq, Haroub, Al-rayth, Samitah, Farasan, Al-Aridha, and Al-Idabi. The population, according to the 2010 census, was about 1.37 million. It is made up of ethnic Arabs and divided into several tribal communities. All people speak Arabic and they have old cultural traditions and festivals. The main occupations of these communities have been livestock rearing and traditional agriculture. Jazan region has a hot desert climate with an average annual temperature above 30°C.

Figure 1.

Map of Saudi Arabia and the study area (Jazan region).

The plants considered in this study were collected from areas ranging in altitude between sea level and 3,000 m. The area is characterized by considerable cultural, topographic, and climatic diversity. The area can be divided roughly into three different regions: Tihama coastal plains, the escarpments (highlands), and the islands. It represents variant landforms such as marshland, coastal plains, alluvial plains, and valleys. Based on annual rainfall, the area of Tihama was classified as arid while the high mountains as semiarid [58]. Data of 25 years obtained from Jeddah Regional Climate Center [58] show that the climate in the lowlands (Tihama coastal plains and islands) is characterized by hot summers (33.6°C in June and July) and mild winters (26.1°C in January), with the mean annual temperature is 30.4°C and the mean annual rainfall is 139.7 mm. The rainy season in these regions occur between August (26.2 mm) and October (18.5 mm). Humidity ranges from 60% in July to 73% in the winter period with an average relative humidity about 68%. On the other hand, data of five years obtained from the meteorological station of Fayfa Development Authority show that the climate in the high mountains (Jabal Fyfa, Jabal Tallan, Bani-Malek, Jabal Hasher, Habess, Khacher, wadi Dafa, Maadi, Jabal Qahar, etc.) is characterized by rainy cold winters, rainy cool summers, and a mean annual rainfall of ca. 373 mm. The hottest and the coolest months are June (41.2°C) and November (16°C), respectively.

From a biogeographical point of view, the vegetation of this region is closely related to that of Yemen and East African countries such as Ethiopia and Eritrea [52]. Tihama coastal area is characterized by a sparse vegetation cover with eight major community types dominated by nine perennials: Ziziphus spina-christi, Calotropis procera, Leptadenia pyrotechnica, Suaeda monoica, Panicum turgidum, Salvadora persica, Acacia tortilis, Tamarix mannifera, and Cyperus conglomeratus. This area is noted for production of high-quality tropical fruits like mango, figs, and papaya. The region has been considered a natural reservoir for the collection of wild MPs [2]. Still most of the species are found in the mountain chains to the east highly occupied by human settlements from ancient times [2, 13]. The west facing slopes of these mountains, which profit from frequent moisture-laden winds from the Red Sea, boost a plant cover with several endemic and endangered species. Terrace cultivation has been practiced in these mountains for centuries and Arabica coffee, khat (Catha edulis), maize, vegetables, and fruits are widely cultivated here. The natural vegetation of the escarpments is dominated by Acacia asak, Otostegia fruticose, Olea europaea, Dodonaea viscosa, Rhus retinorrhaea, and Pennisetum setaceum. The higher elevations (above 2000m) are home to a Juniperus procera forest along with Acacia origena and O. europaea subsp. cuspidata and many other shrubs such as Clutia myricoides, Maytenus arbutifolia, and several annual and perennial ground cover species.

2.2. Consent and Ethical Approval

This ethnomedicinal study was duly approved by the Standing Committee for Scientific Research Ethics of Jazan University, Saudi Arabia (Registration number HAPO-10-Z-001). Prior to conducting the interviews, the objectives of the study were well explained to the participants and a written consent was obtained from each individual.

2.3. Collection of Ethnobotanical Data

Semistructured interviews following standard ethnobotanical methods of Martin [59] and group conversation with local peoples were led in Arabic (spoken by both participants and the interviewers) in a relaxed, informal discussion, with the interviewee and interviewer sitting face-to-face, normally in the healer's house. A copy of the survey questionnaire is provided as supplementary information (Additional file 1). The research was carried out over a period of approximately 2 years (2015–2016) in Tihama coastal plains comprising the biggest towns of Jazan province, e.g., Jazan, Abou-arish, Al-darb, Ash-Shuqaiq, Sabya, Haroub, Al-rayth, and Farasan, as well in the mountains regions of Fyfa, Al-Aridha, Al-Idabi, Beni-Malek, Tallan, Dafa, Habess, Sala, Khacher, Qahar, Hashar, and Maadi (Figure 1). Despite the good public health facilities existing in the mountain villages, peoples have to travel in some cases about 100 km to find a modern hospital with well-trained medical staff which is mostly in Jazan city, Abu-Arish, and Sabya (Tihama coastal plains). Moreover in several rural areas modern health facilities were only built recently and they generally provide care for simple conditions [10]. Therefore, we compared the knowledge of MPs between the two collection regions and between four age brackets (35–45, 46-55, 56-65, and above 65 years of age). Further comparisons were made between educational level categories of informants. In total 174 informants with 93% male, 7% female and traditional healers were interviewed. Half of informants (87) were from Tihama coastal plains and the other half from the mountain villages. Most of the informants (88%) were from the rural areas. Information regarding the local vernacular plant names, plant parts used, and preparation techniques of the recipes were documented. The participants were requested to indicate the wild MPs most often used in the past and now. First, they mentioned the plants to the interviewers and later took the interviewers to spots from where they collected the plants. Whenever available, plant samples of the MPs mentioned were collected or obtained from the participants, then dry pressed in the field using a plant press, and later brought back to the university for complete identification. The scientific names of the plants were determined by the authors who cross-checked their vernacular names and photographs with available literature. The dry pressed plants were identified by using flora of Saudi Arabia [50] literature and botanists from Jazan University Herbarium. Later, they were compared with deposited herbarium specimen at Jazan University, Jazan. The nomenclature was followed as given in the International Plant Name Index (http://www.ipni.org) and the plant list (www.theplantlist.org). For the families, A.P.G. system (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system) was followed [60]. A set of voucher specimens was deposited in the herbarium of the Centre for Environmental Research and Studies, Jazan University, Jazan. Instances of endemism and risk categories (www.plantdiversityofsaudiarabia.info/Biodiversity-Saudi-Arabia/Flora) were also specified for some species. The information given on local MPs was compared with data from the literature.

2.4. Data Presentation and Analysis

The collected data was analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively using diverse indices such as Informant consensus factor (ICF), relative frequency citation (RFC), fidelity level (FL%), and relative importance (RI) level to check the level of consensus within a community and the curative potentials of the cited plants. Before calculating the ICF index, diseases are mostly classified into twelve categories based on the information gathered from the informants. ICF index specifies the homogeneity of the ethnobotanical data and the degree of overall agreement about a specific plant use to treat a specific category of ailment and, then, the degree of shared knowledge for the treatment of that ailment. The ICF was calculated by the formula described earlier [61, 62] as follows:

| (1) |

where nur is number of use reports for each disease category and nt indicates the number of species used in said category.

The ICF value ranges from 0 to 1. A value close to one indicates that only one or a few plant species are reported to be used by a large fraction of informants to treat a particular category of ailments. Yet, lower values (close to 0) indicate that informants disagree over which plant to use [62]. The use of the ICF allows the degree of consensus about the treatment of different ailments within a community to be assessed as well as the identification of the most important MP species. In other words, by using the ICF it was possible to detect species of specific importance for a given community and to compare that to how they are used in other cultures.

Ethnomedicinal data were quantitatively analysed using Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) which indicates the local importance of a species. RFC is calculated as follows [63]:

| (2) |

where FC is the number of informants citing a useful species and N is the total number of informants in the survey. A highest RFC value (RFC close to 1) indicates that the informants report the particular species as useful, whereas a lower RFC value (RFC close to 0) indicates that nobody mentioned the use of that plant species.

The fidelity level (FL%) was calculated to rank the recorded plant species based on their claimed relative efficacy. It indicates the proportion of informants who cited the uses of certain plant species to cure a specific disease in a study area. FL was calculated for the most regularly reported diseases or ailments. It was given by the following formula [64]:

| (3) |

where ‘Ip' is the number of informants that claimed a use of certain plant species for a particular disease and ‘Iu' is the total number of informants citing the species for any disease or ailment. The high value of FL (%) shows the reputation of certain species over other plants to cure a particular disease as high value approves the high rate of plant usage against a definite ailment. MPs that are not regularly used have low FL and the informants commonly disagree on their potential. The MPs that were cited only by one informant to cure a precise ailment were not considered in the FL ranking. Relative importance (RI) of MP species mentioned by the informants was calculated as follows [65]:

| (4) |

where NP is obtained by dividing the number of specific ailments ascribed to a plant species by the total number of ailments ascribed to the species with the highest number of pharmacological properties. NCS is the number of ailment categories ascribed to a species divided by the total number of ailment categories ascribed to the most versatile species. The highest value for RI (RI=2) indicates the most versatile species with the maximum number of uses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

Demographic characteristics of the informants were documented through semistructured interviews and group conversation with local inhabitants. A total of 174 local participants with 162 males (93%) and 12 females (7%) were questioned. Informants, with diverse ages (35–45, 46-55, 56-65, and above 65 years of age), from several settlements belonging to several local tribal communities were interviewed. The communities living in mountain villages and those of Tihama coastal plains were considered in the present study. The study revealed that only 12 informants, most of them from Tihama plains (75%), did not have knowledge of MPs (Table 1). Accordingly, most inhabitants (about 93%) mainly from the mountain settlements still use conventional medicine alone or in combination with modern drugs. Surveys conducted in other countries had reported values ranging from 42% to 98% depending on the region and country of the study [66, 67]. Still, the high percentage of TK of MPs identified in Jazan province may be due to factors such as lower influence of the modern and urban lifestyle and the strength of cultural traditions in the rural communities. Still the transmission and conservation of TK are more evident in the mountain villages due to the high plant biodiversity and the modesty of public health facilities compared to the big cities. Furthermore, these modern health facilities found presently in the mountain villages were built only recently and they are generally providing care for simple conditions [10]. Therefore peoples from the mountain villages have to travel about 100 km to find a modern hospital which is mostly in Jazan city, Abu-Arish, and Sabya (Tihama coastal plains). As far the dominance of male participants, it is due to the fact that women in the study area were reluctant to talk to male strangers (the research team). All females interviewed were from Tihama plains and were old women; meanwhile it was not possible to interview any women from the mountainous regions. Previous studies showed that women from Saudi Arabia combine biomedical and MP health care and learn about MPs from their social network, mass media, and written sources [14].

Table 1.

Number of MPs reported by informants from Tihama coastal plains (n= 87) and the mountain villages (n= 87) of Jazan region as well as the number of MPs reported by informants with varying educational level (n=174).

| Number of MPs reported | Informants ages bracket in Tihama coastal plain (years) | Informants ages bracket in the mountain villages (years) | Informants' educational level category | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35-45 | 46-55 | 56-65 | above 65 | Total | 35-45 | 46-55 | 56-65 | above 65 | Total | Illiterate | Primary school | Secondary school | High school | University | Total | |

| 0 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 34 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 32 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 23 |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 16 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 25 |

| ≥6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

One of the most important aspects of this research is the documentation of a high number of taxa mentioned by the informants as medicinal, whereas in several other regions of Saudi Arabia folk medicine is still practiced among local communities but on a limited scale [1, 4, 7, 13, 21, 68]. For instance, in Al-Bahah region, with comparable climate and biodiversity to Jazan region, only 39 plant species were recorded by the informants for their medicinal benefits [4]. Moreover, TK loss has been reported in local communities and Bedouins living in the desert area in the central region of Saudi Arabia [13]. In general, TK erosion has been observed in the Middle East both among herbalists and the general population [69]. Still rural communities have more knowledge about the medicinal and therapeutic properties of plants and have contributed to the conservation and transmission of the TK.

3.2. Knowledge of Study Participants

The study revealed that informants have rich TK about the distribution, harvesting, and uses of MPs. The present results show that the few women (7%) questioned has comparable knowledge to men on conventional medicine. The average MP reported by a female is 4.36 ± 0.76 and by male is 3.98 ± 1.17. The difference between the two genders was not significant. Moreover, the TK is mostly held by old males (41% of the reported plants). This is different from some societies in Africa, South America, and Asia where experts in MPs and their use are mostly women [70, 71]. In fact most of the medicinal healers (Hakim or Tib Arabi) in these tribal communities are old men. Ten men (among the 174 respondents) are known as healers of which seven are from the mountain villages and three from Tihama coastal plains settlements. These local expert healers account for a significant number of citations (155) in this study. The number of ailments reported by the informants ranged from 1 to 18. The highest number of MPs reported by a healer is 19 (Tihama plains). They also stated mixture of many MPs to treat an ailment while most of the informants (45%) told of single or two MPs (Table 1). Only 25 informants (14%) told above six MPs. The number of MPs reported by the participants increased as the distance from modern hospitals increased. In fact, the number of MPs reported in the mountain villages (420 use reports) was much more important than those reported in Tihama plains settlements (277 use reports) where most modern hospitals are located. Moreover, the average number of MPs reported by participants of 35–45 years of age is 0.75 ± 0.27 in Tihama plains and 1.75±0.49 in the mountain villages. Besides, the more aged informants (above 65 years) were the more knowledgeable about MPs uses. The average number of MPs reported by informants above 65 years of age is 5.62 ± 1.59 and 6.29 ± 1.18 for Tihama coastal plains settlements and the mountain villages, respectively. We found that illiterate informants hold more information on herbal medicine (average number of MPs reported is 5.98 ± 1.41) than educated participants (2.23 ± 0.38 reported for those which had a secondary school education). This may be due to the shifting to the use of allopathic medicine and urbanization as reported earlier for several other developing countries [65, 72, 73]. Less educated persons tend to be less acculturated and know more MPs, but educated persons tend to be more acculturated, know few MPs, and seek modern healthcare services. It appears that this TK is not easily passed from the old persons to the younger generation and it may be lost soon. Likewise, most of the informants were using wild plants without attempting to apply any conservation measures to prevent the extinction of species.

3.3. Vernacular and Scientific Plant Names

Most of the vernacular names of plant were found to be derived from Arabic. As shown in Table 2, MPs reported in Jazan region often have one, two, or three names. For some MPs well distributed throughout the Middle East and well known in traditional Arab medicine, generally only one name was given. For example, Alar'ar, Hundhal, Kharwah, Al-Arfaj, and Sabar are the names for Juniperus procera, Citrullus colocynthis, Ricinus communis, Rhanterium epapposum, and Aloe vera, respectively, in all Arab countries. Still for some plants, people of Jazan have additional regional/local names as in the case of A. vera which is also called “Al-Maguar” in Jazan region. Additionally, for some species, a third name is given which is generally the local name of the plant.

Table 2.

List of the MPs recorded from Jazan region, diseases they were claimed to cure and ways of utilisation.

| N° | Family, Plant species, voucher specimen, endemism |

Habit | Habitat | Vernacular name | Plant part (s) used a | Preparations b | Utilization method | Pharmacological activity | RFC | Recorded literature use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACANTHACEAE | ||||||||||

| 1 | Blepharis ciliaris (L.) B. L. Burtt (CERSH-022) | Perennial herb | Sand dunes and plains | Al-Zaghaf | Lea, Roo, See | Pow, Dec | Decoction of leaves, roots and seeds is taken orally. The roots are ground to make a powder applied topically; eye drops | Fever, astringents, appetizer, cough, asthma, wounds, sores, pruritic, injuries, liver and GIT diseases, diuretic, urinary diseases, menstrual pain, spleen disorder, eye pain | 0.05 | Vitiligo, sores, wounds, fever, cough, asthma, anti-inflammatory, cataracts, astringents, eye inflammation, appetizer, antitoxic, diuretic, lung diseases, liver and spleen disorder [4–6] |

| 2 |

Anisotes trisulcus (Forssk.) Nees (endemic) (CERSH-044) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Math | Lea, flow | Dec | Boiling crushed fresh leaves and flowers in water and the water is taken orally | Fever, malaria, diabetes, foot inflammation, oedema, hepatoprotective, neurological disorder, hepatitis | 0.06 | Diabetes, malaria, hepatitis, oedema, epilepsy, anaesthetic, hepatoprotective, jaundice, antibacterial, cytotoxicity [7–9] |

| 3 |

Avicennia marina Forssk (CERSH-108) |

Sub-shrub | Along the shore-line | Shoura | Bar | Inf | Soaking crushed bark in water and the water is taken orally | Smallpox, sores, pruritic, induce women infertility, diabetes | 0.04 | Smallpox, diabetes [10, 11] |

| 4 |

Peristrophe paniculata (Forssk.) Brummitt (CERSH-076) |

Annual Herb | Tihama plains | Madhiafa, thouem | Who | Inf | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally | Anti-snake venom | 0.02 | Anti-snake poison [5] |

| AGAVACEAE | ||||||||||

| 5 |

Dracaena ombet Kot. & Peyr. (rare) (CERSH-109) |

Tree | Fyfa mountains | Azef, Meqr | Aer, Res | Ext, Pas, Pow | Paste is applied topically for skin problems; the plant extract is taken orally for malaria, powdered resin is applied topically | Skin infections, wounds, burns, injuries, haemorrhage, smooth the hair, allergy, malaria, spasm | 0.03 | Wounds, burns, hair, spasm, strengthening, allergy, malaria [10] |

| AMARANTHACEAE | ||||||||||

| 6 |

Achyranthes aspera L. (CERSH-107) |

Perennial herb | Fyfa mountains | Mahwat | Who | Pas, Ext | Leaf paste is applied locally for skin diseases; root paste is applied on snake bite area, the plant extract is used for fever, abortion and labour pains and GIT diseases; gargle for toothache | Fever, astringent, colds, stomach ache, diuretic, skin diseases, acne, anti-inflammatory, pruritic, snake and scorpion stings, abortion and labour pains, toothache | 0.06 | Pruritic, fever, snake bites, jaundice, stomach-ache, toothache, colds [5, 12] |

| 7 |

Suaeda aegyptiaca Hasselq (CERSH-114) |

Perennial herb | Tihama plain and Farasan Islands | Suwwad | Lea | Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically | Contagious skin diseases, blisters, sores, pruritic | 0.02 | Blisters and sores [4] |

| 8 |

Aerva javanica (Burm.f.) Juss. ex Schultes (CERSH-046) |

Perennial herb | Common in Tihama plains | Al-Raa | Roo, lea, flow, See | Pow, Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically for skin diseases; soaking the crushed fresh plant in water and the water is taken orally | Headaches, wounds, injuries, bruises, toothache, snake and insect stings, malaria, kidney stones, bone fractures, rheumatism, neurological disorders | 0.09 | Headaches, toothache, haemostatic, wounds, ulcers, anti-inflammatory, neurological disorder, rheumatism, GIT diseases, bone problems, haemorrhage, kidney problems [6, 7, 12–15] |

| 9 | Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult (CERSH-115) | Perennial herb | Near the stagnant waters of the wadis | Al-Athlab | Who | Ext, Pas | Root paste is applied on scorpion sting area | Diuretic, GIT diseases; scorpion stings | 0.02 | Antimicrobial, scorpion sting [16] |

| 10 |

Amaranthus viridis L. (CERSH-075) |

Annual herb | Fyfa mountains | Kaf Almehana, Qutaifa | Who | Pas, Dec | Leaf used as emollient in scorpion stings | Blood purifier, piles, GIT diseases, abortifacient, scorpion stings | 0.04 | Scorpion stings [17] |

| APIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 11 |

Anethum graveolens L. (CERSH-045) |

Annual herb | Cultivated in gardens | Shibt/ snout | Lea, fru, Roo | Inf | Soaking crushed plant and the water is taken orally | Postnatal problems, GIT problems | 0.03 | GIT diseases [14] |

| 12 |

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (CERSH-116) |

Perennial herb | Mountains | Shamr | Roo, See | Pow, Dec | Boiling crushed fresh roots in water and the water is taken orally | Body energizer, tonic, GIT diseases, spasm, blood purifier, malaria | 0.04 | GIT diseases, urological, neurological, gynaecological, blood and immune system, cough, spasm [14, 18] |

| 13 |

Cuminum cyminum L. (CERSH-023) |

Annual herb | Cultivated in gardens | Cumin | See | Inf or Dec, Pow | Seeds powder applied externally; boiling crushed seeds in water and the water is taken orally | GIT problems, urinary diseases, scorpion stings, diabetes | 0.03 | GIT diseases, gynaecological, endocrine and nutritional problems, respiratory problems [14] |

| 14 | Trachyspermum ammi (L.) Sprague (CERSH-001) | Shrub | Cultivated in gardens | Ajwain | Who, See, oil | Pow, Dec | Boiling crushed seeds in water and the water is taken orally; Seeds powder applied externally; oil is given to expel hookworms. | GIT diseases, hookworms, diarrhoea, asthma, coughs, influenza, cholera, kidney stones, urinary diseases, scorpion stings, SM disorders | 0.04 | GIT diseases, SM disorders, gynaecological, scorpion stings [14] |

| APOCYNACEAE | ||||||||||

| 15 |

Caralluma edulis (Edgew.) Benth. & Hook.f. (CERSH-074) |

Perennial herb | Along watercourses | Ghlotha | See, Ste | Pas, Pow | Powder mixed with milk and applied externally, leaf paste is applied topically | Malaria, respiratory and throat diseases, lung pains, scorpion stings and snake bites, chickenpox, smallpox, measles, pruritic | 0.04 | Chickenpox, smallpox, diabetes, measles, breast cancer [10, 19] |

| 16 |

Monolluma quadrangula (Forssk.) Plowes (CERSH-106) |

Perennial herb | Mountains | Ghalaf | Lea | Cook/ heated | Heated on coal then cooked with spices and eaten; the fresh plant is eaten to treat gastric ulcers and diabetes | Influenza, diabetes, spasm, gastric ulcers | 0.03 | Influenza, diabetes, spasm, gastric ulcers [10, 20] |

| 17 |

Ceropegia variegata Forssk. Decne. (endangered) (CERSH-047) |

Perennial herb | Along watercourses | Meyabesa | Aer | Pas | Leaf paste is applied externally in the abdominal area | Expel tapeworms | 0.02 | Taeniafuge [10] |

| 18 |

Calotropis procera (Aiton.) W.T. Aiton (CERSH-024) |

Small tree | Distributed in Tihama palin | Ushar | Flow, lea, Ste, lat | Ext, Pas, lini, Pou | Leaf paste is used to clean pain area. Leaf extract is applied directly against hair loss; Leaf paste and latex are used for locally for skin problems; poultice is applied on rheumatic pain | Body energizer, fever, asthma, headaches, indigestion, cough, diarrhoea, toothache, leprosy, wounds, muscles problems, skin infections, boils, psoriasis, hair loss, scorpion stings, malaria, diabetes | 0.08 | Skin infections, psoriasis, hair loss, diabetes, leishmaniosis, analgesic, respiratory problems, scorpion stings, strengthening muscles, rheumatism [5, 6, 10, 13, 14, 21] |

| 19 |

Leptadenia pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne (CERSH-002) |

Shrub | Sand dunes and plains | Markh | Who | Inf, Pas, Ext | Soaking crushed bark in water and the water is taken orally; crushed stems are applied to wounds; infusion of the whole plant mixed with butter milk is given for stomach disorders. | Headaches, diuretic, stomach disorders, wounds, stop bleeding, kidney disorders, urinary retention, SM and gynaecological disorders | 0.06 | diuretic, smallpox, psoriasis, eczema, dermatitis, diabetes, carminative, purgative, antitumor, hypolipidemic, anti-atherosclerotic [6] |

| 20 |

Nerium oleander L. (CERSH-093) |

Small tree | Cultivated in gardens | Difla | Lea, Roo | Pas, Ext, Pou | Extracts from leaves and roots are used internally; poultice is applied for skin problems. | Skin diseases, scabies, pruritic, bronchitis, coughs, diuretic, anti-snake venom | 0.06 | Diuretic, emetic, bronchitis, coughs, scabies [6, 18] |

| 21 |

Rhazya stricta Decne. (CERSH-119) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Harmal | Lea, flow | Pow, Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically | Rheumatism, allergy, improving bad breath, skin rash, pruritic | 0.06 | Tonic, stimulant, syphilis, allergy, GIT disease, anti-microbial, colon cancer, anti-inflammatory, rheumatism [4, 6, 13, 14, 19] |

| 22 |

Carissa edulis Vahl (Forssk.) CERSH-073 |

Shrub or small tree | Fyfa Mountains | A'rm, Airoon | Lea, Fru | Pow, Pas | Berries are eaten raw; leaf paste is applied topically | Anti-snake venom, parasitic worms, colic, toothache, menstrual pain | 0.03 | Anthelmintic, stomach disorders, antiscorbutic, toothache, astringent [22] |

| 23 |

Adenium obesum (Forssk.) Roem & Schult. (rare, endemic) (CERSH-124) |

Shrub | Rocky slopes at intermediate elevations | Adnah | Aer, lat | Pow, Pas, Jui | Powdered plant is applied externally on the head; the plant juice is dropped directly in the mouth; the use of plant milky latex is applied topically to skin diseases (lotion) | Headache, GIT diseases, skin infections, rashes, pruritic, lice, muscle pain, dislocations, excites the sexual desire in women, venereal diseases, scorpion stings, teeth cleaning, pesticide | 0.07 | Headache, muscle pain, joint pain, kill lice, tonsillitis, skin diseases, cleaning the teeth, aphrodisiac, antiviral, antibacterial, venereal diseases [7, 10, 15, 23–26] |

| ASPARAGACEAE | ||||||||||

| 24 |

Sansevieria ehrenbergii Schweinf. ex Baker. (CERSH-078) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Salb | Aer | Pow | Powder is applied topically on skin affected areas | Wounds, pruritic, injuries, insect bites, malaria | 0.03 | Wounds, insect bites [10] |

| ASPHODELACEAE | ||||||||||

| 25 |

Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (CERSH-105) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Al-Maguar, Sabar | Lea, Roo | Jui, Ext, Pas | Leaf juice is given orally for menstrual trouble, treating gonorrhoea, liver and spleen disorders; leaf gel is applied topically for skin problems; paste is applied locally for rheumatism | Fever, laxative, sunstroke, malaria, eczema, psoriasis, hair loss, gastric ulcer, liver pain, diabetes, menstrual troubles, gonorrhoea, spleen disorders, nerve pain, rheumatism | 0.08 | Skin diseases, eczema, psoriasis, laxative, sunstroke, stomach ulcer, pain of nerves, gonorrhoea, menstrual trouble, liver and spleen disorders, rheumatism [5, 14, 15, 27] |

| 26 |

Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. (CERSH-025) |

Perennial herb | Along watercourses | Broque | See, Roo | Pas, Pou | Poultice is applied for skin problems and rheumatism | Skin diseases, wounds, anti-inflammatory, pruritic, rheumatism, colds | 0.02 | Eczema, alopecia, paralysis, earache [28] |

| ASTERACEAE | ||||||||||

| 27 |

Pulicaria undulata (L.) Kostel. (CERSH-090) |

Perennial herb | Fyfa Mountains | Gathgath | Who | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically, infusion is taken orally for internal diseases | Skin diseases, wounds, central nervous system depression | 0.06 | Central nervous system depression, antimicrobial, breast cancer, liver cancer, leukaemia, diuretic [6, 19, 23] |

| 28 | Pulicaria jaubertii Gamal Ed Din (CERSH-048) | Perennial herb | Tihama plains and Farasan Island | Al-Arar/ Eter Elraee |

Who | Dec | Soaking crushed leaves in boiled water and the water is taken orally | Carminative, intestinal worms, digestive disorders, malaria | 0.03 | Anthelmintic, antimicrobial, antifungal, antimalarial, insecticidal [29] |

| 29 |

Pulicaria schimperi DC. (CERSH-072) |

Annual or biennial herb | Fyfa Mountains | Sakab | Lea | Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically to cure wounds and for hair | Hair strengthening, wounds infection | 0.03 | Wounds [30] |

| 30 |

Rhanterium epapposum Oliv. (CERSH-003) |

Shrub | Desert lands | Al-Arfaj | Lea | Pas, Dec | Leaf paste is applied topically; decoction is used orally to treat diabetes and digestive troubles | Respiratory and throat diseases, diabetes, allergy, oedema, digestive troubles, toothache, insect repellent | 0.06 | Diabetes, allergy, oedema, toothache, GIT disorders, antimicrobial [6, 10] |

| 31 | Artemisia abyssinica Schultz-Bip (CERSH-121) | Shrub | Mountains | Beithran, Al-obal | Who | Dec or Inf | Decoction is used orally to treat diabetes, cough, cold, irritation of the throat and menstrual pain | Appetizer, digestive troubles, parasitic worms, spasm, rheumatism, menstrual pain, diabetes, malaria, cough, cold, irritation of the throat | 0.07 | Appetizer, headache, diabetes, mellitus, cold, spasm, pharyngitis, insect repellent, anthelmintic, rheumatism, antibacterial, indigestion [5, 7, 10, 23] |

| 32 |

Artemisia sieberi Besser (CERSH-092) |

Shrub | Mountains | Shih | Who | Dec, Bur | The whole plant is used as a smoke inhalant to treat various diseases; decoction from leaves are used orally as an anthelmintic | GIT diseases, intestinal worms | 0.04 | Breast and liver cancer [19] |

| 33 | Chrysanthemum coronarium L. (CERSH-071) | Annual herb | Tihama palin | Oukhouan | Who | Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically; fresh roots are chewed | Laxative, anti-inflammatory | 0.03 | Purgative, syphilis. Anti-inflammation [5] |

| 34 |

Achillea biebersteinii Afan. (CERSH-079) |

Perennial herb | Mountains | Kaysoum/Aldefera/ thafra'a |

Who | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically; an infusion form its leaves is used orally; chewing of fresh leaves relieves toothache | Carminative, itching, insect repellent, urinary diseases, toothache, kidney inflammation, menstruation troubles, leishmaniosis | 0.05 | Leishmaniosis, insect repellent, toothache [7, 23] |

| 35 |

Conyza incana (Vahl) Willd. (CERSH-026) |

Perennial herb | Fyfa Mountains | Baithran, arfaj | Lea | Bur | The smoke of burned leaves is used to repel insects and is inhaled nasally for relieving muscular pains | Central nervous system depression, cardiac stimulation, muscular pains, insects repellent, malaria, leishmaniosis | 0.03 | Antifungal activity [23] |

| 36 |

Xanthium strumarium L. (CERSH-081) |

Annual herb | Along watercourses | Who | Dec, Cook | Soaking crushed whole plant in boiled water and the water is taken orally | Malaria, GIT disorders, stomach ache | 0.02 | Leukoderma, bites of insects, epilepsy, allergy, salivation, malaria, leprosy, rheumatism, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diarrhoea, constipation, lumbago, pruritus, bacterial and fungal infections [31] | |

| 37 | Osteospermum vaillantii Decne (CERSH-110) | Shrub | Moutains | Annakad, Hechmat El-thore | Who | Inf | Soaking crushed whole plant in water and the water is taken orally | GIT diseases, liver disorders | 0.02 | Fever, stomach ailments and liver disorders |

| 38 |

Picris cyanocarpa Boiss. (CERSH-094) |

Annual herb | Tihama plains | Hozan | Who | Dec | Soaking crushed whole plant in water and the water is taken orally | Lower blood pressure, cardiac stimulation, central nervous system stimulation, | 0.02 | Antioxidant properties [23] |

| 39 |

Sonchus oleraceus L (CERSH-004) |

Annual herb | Fyfa Mountains | Uddaid | Lea, flow | Pas, Dec | Leaf paste is applied topically; decoction applied orally to induce menstruation | Induce menstruation, skin infection, sores, pruritic, scorpion stings | 0.03 | Skin diseases, sores [4, 13] |

| ASPARAGACEAE | ||||||||||

| 40 |

Asparagus africanus Lam. (CERSH-111) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Smin, khurus theeb | Aer | Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically, chewing of leaves relieves breathing problems | Paralysis, skin diseases, pruritic, swelling, malaria, breathing problems | 0.03 | Malaria, leishmaniosis, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities [32] |

| BORAGINACEAE | ||||||||||

| 41 |

Heliotropium digynum Forssk. (CERSH-070) |

Shrub | Sandy soil in Tiham plains | Hettan, Raghel, Atana, Dafra | Who | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Skin diseases, liver pain, diuretic | 0.03 | Skin diseases [4] |

| 42 | Heliotropium bacciferum Forssk. (CERSH-027) | Perennial herb | Tihama palin | Ramram | Who, lea | Dec, Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically for snake bites; decoction applied orally is used for urinary problems | Urinary diseases, snake bites, skin infections | 0.04 | Scorpion stings, skin diseases, tonsillitis [21] |

| BURSERACEAE | ||||||||||

| 43 |

Commiphora gileadensis (L.) Christ.(rare) (CERSH-049) |

Shrub | Tihama plains and Farasan Island | Al-bisham | Bran, gum, Res | Dec, Pas, Pou | Poultice is applied for skin problems and bone fracture (topically); soaking crushed resin in water and the water is taken orally | Toothache, respiratory diseases, anti-snake venom, bone fracture, leishmaniosis, nervous system disorders | 0.05 | Anti-snake poison, peptic ulcer, leishmaniosis, gynaecological diseases, respiratory diseases, neurological troubles [7, 14] |

| 44 | Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. (rare) (CERSH-005) | Shrub | Tihama plains | Myrrha Orouq Al Aqa |

Res, gum, Bar | Inf, Pas | Oil leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed resin or bark in water and the water is taken orally | Carminative, bone fractures, wounds, burns, pruritic, stomach pain, urinary tract infection, scorpion stings | 0.05 | Laxative, wounds, stomach pain, diarrhoea, urinary tract infection, scorpion stings, respiratory diseases, gynaecological infections, haemorrhage [10, 12, 14, 21] |

| BRASSICACEAE | ||||||||||

| 45 |

Matthiola Arabica Boiss. (CERSH-080) |

Annual herb | Tihama plains along watercourses | Soqar | See | Inf | Soaking crushed seeds in water and the water is taken orally; the seeds are eaten raw | Anaemia | 0.02 | Anaemia [10] |

| CACTACEAE | ||||||||||

| 46 | Opuntia ficus-indica Mill (CERSH-006) | Shrub | Cultivated in gardens | Barshoum | Ste, Fru | Dec | Soaking crushed stems in boiled water and the water is taken orally | Diabetes | 0.03 | Diabetes [21]. |

| CAPPARIDACEAE | ||||||||||

| 47 |

Capparis spinosa L. (CERSH-028) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Shafallah | Lea, Roo | Dec, Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed leaves and roots in boiled water and the water is taken orally | Urinary diseases, kidney stones, GIT problems, parasitic worms, diuretic, skin diseases, anti-inflammatory, rheumatism, diabetes, splenomegaly, induce menstruation | 0.06 | Dermatitis, diarrhoea, diabetes [5, 7] |

| 48 | Capparis decidua (Forssk.) Edgew (rare)(CERSH-051) | Shrub | Tihama plains and Farasan Islands | Tandhab | Who | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed fresh leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Carminative, laxative, fever, intestinal worms, leprosy, sores, ear pain, diabetes, rheumatism, aphrodisiac, induce menstruation | 0.05 | Coughs, appetizer, asthma, fever, boils, anti-inflammatory; cardiac troubles, analgesic, biliousness, alveolaris, pyorrhoea, purgative, diabetes, anthelmintic, hypercholesterolemia, antimicrobial [33] |

| 49 |

Cadaba rotundifolia Forssk. (CERSH-069) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Kathab | Lea | Inf | Soaking crushed fresh leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Rheumatism, urinary diseases | 0.02 | Antibiotic [12] |

| 50 |

Cadaba farinosa Forssk (CERSH-050) |

Shrub | Abu-Arish Tihama plains | Asaf, Qusaia, Azan-al-arnab | Lea | Pas, Dec | Leaf paste is applied topically on the head; decoction from leaves is taken orally | Parasitic worms, liver pains, dysentery, induce menstruation, cough, lungs problems, nervous system disorders | 0.04 | Hepatoprotective, sores, wounds, hydrocephalus, haemorrhage antioxidant activities [12] |

| CARYOPHYLLACEAE | ||||||||||

| 51 | Minuartia filifolia (Forssk.). Mattf. (CERSH-095) | Perennial herb | Mountains | Oud Al-Halaba | Bar | Pas, Dec | Leaf paste is applied topically, decoction from bark is taken orally | Promote women fertility, snakes bites | 0.02 | |

| CLEOMACEAE | ||||||||||

| 52 |

Cleome viscosa L. (CERSH-007) |

Annual herb | Fyfa Mountains | Om -Hanif | Who | Pas, Dec | Leaf paste is applied topically; decoction from crushed fresh leaves is taken orally | Intestinal worms, stomach ache, anti-inflammatory, skin diseases, wounds, leprosy, malaria, ear pain, snake bites | 0.05 | Anthelmintic, wounds, analgesic, carminative, anticonvulsant, antitumor, antidiarrheal, antiemetic, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective [12] |

| 53 | Cleome amblyocarpa Barratte & Murb.(CERSH-104) | Annual herb | Tihama plains | Khunayzah/ ouffina | Who | Dec | Decoction from crushed plant is taken orally | Insecticide, scabies, rheumatism, kidney problems, sexual stimulator | 0.03 | Rheumatism, rheum, scabies, rheumatic fever, anti-inflammatory [6] |

| 54 |

Cleome gynandra L. (CERSH-117) |

Annual herb | Along watercourses and mountains | Oyfiqan | Roo, lea, See | Dec | Boiling crushed fresh leaves and roots in water and the water is taken orally | Appetiser, carminative, ear pain, splenomegaly, muscles problems, scorpion stings | 0.04 | Muscle weakness, diabetes, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, cardiovascular diseases [10, 34] |

| 55 | Cleome brachycarpa Vahl ex DC (CERSH-068) | Perennial herb | Tihama plains and Farasan Islands | Birbran | lea | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed fresh leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Appetizer, carminative, stomach irritant, skin diseases, scabies, leprosy | 0.03 | Diuretic and astringent, narcotic and stomach irritant, foot problems [6, 12] |

| COMBRETACEAE | ||||||||||

| 56 | Combretum molle R.Br. ex G. Don. (CERSH-029) | Shrub or small tree | Fyfa Mountains | Althu'ab | Gum | - | The gum is eaten raw | Cause women infertility, digestive disorders, stomach ache, malaria | 0.03 | anti-inflammatory, infections, diabetes, malaria, bleeding, diarrhoea, digestive disorders, diuretic, anti-Trypanosoma, anthelmintic [7, 35] |

| CUCURBITACEAE | ||||||||||

| 57 | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. (CERSH-008) | Perennial herb | Along watercourses | Hundhal | Fru, See, lea | Dec | Half the fresh fruit is applied topically; decoction of leaves and seeds is used orally. | Laxative, scorpion stings and snakes bites, insect bites, leishmaniosis, vitiligo, skin infections, rabies, GIT diseases, rheumatism | 0.08 | Laxative, analgesic, skin infection, hair dye, scorpion, dog, insect and snake bites, vitiligo, GIT diseases, larynx cancer, leukaemia [4, 6, 13, 14, 19, 21] |

| CUPRESSACEAE | ||||||||||

| 58 | Juniperus procera Hochst. Ex. Endel. (CERSH-052) | Tree | Al Hashar mountains | Alar'ar | Lea, fru | Inf, Bur | Soaking crushed fruits in water is taken orally; leaves are applied on burning charcoal and smoke is inhaled nasally | Skin infections, warts, toothache, spasm, cold, flu | 0.03 | Spasm, gout, cold, pharyngitis, urological disorder [7, 14] |

| EUPHORBIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 59 |

Ricinus communis L. (CERSH-009) |

Shrub | Widely distributed in Tihama plains | Kharwah | Who, oils | Lini, Pow, Ext, Jui, Pou | Leaf and root powders are applied topically on wounds; root extract is given to treat asthma, bronchitis and rheumatism; poultice of leaves applied locally; seed oil is applied topically | Boils, sores, warts, wounds, intestinal worms, dysentery, inhibit menstruation, enhance the lactation process, rheumatism, joint pain, bad breath, toothache, asthma, bronchitis, scorpion stings | 0.07 | GIT diseases, dysentery, asthma, warts, wound, skin diseases, boils, sores, SM, bronchitis, Joint pain, cracks of feet, rheumatism [4, 5, 14] |

| 60 | Euphorbia schimperiana Scheele (CERSH-123) | Small tree | Fyfa Mountains | Lubbana | Who, lat | Ext, Dec, lini | An extract of leaves and roots is used topically; soaking crushed fresh leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Laxative, respiratory and throat diseases, coughs, asthma, wounds, skin infections, anti-snake venom, ear pains | 0.04 | Cavernous stinking wounds [7] |

| 61 |

Euphorbia retusa (Forssk.) (CERSH-053) |

Perennial herb | Ghazalah/ Om-laben |

Lat | Lini | Latex is used topically | Nervous system depression, asthma, eczema, wounds, warts, leishmaniosis | 0.03 | Anorectal diseases, colon diseases, fissures, cracks, fistulas, abscesses, haemorrhoids, inflammatory bowel disease [36, 37] | |

| 62 |

Jatropha glauca Vahl. (CERSH-030) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountain | Kharat, Orouq Aobab | Lea, See, Ste | Pow, Dec, Pas | Soaking crushed fresh leaves in water and the water is taken orally; the paste is used topically; powder of white stems is used topically | Chronic skin diseases, enhance the lactation process, asthma, allergy, malaria | 0.03 | Asthma, leukoderma, allergy, haemorrhoids [10, 12]. |

| 63 |

Acalypha fruticosa (Forssk). var. fruticose (CERSH-082) |

Shrub or tree | Along watercourses and Abadil mountains |

Thefran, anama | Lea, Roo | Pas, Dec, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking the crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally or used as nose drops; a root decoction/infusion is taken orally for fever and constipation; stems or roots are chewed for toothache | Fevers, toothache, eye infections, bee stings, malaria, typhoid, liver problems, constipation, wounds, skin infections, sores, colds, cough, haemorrhage | 0.06 | Malaise, fevers, colds, cough, tooth decays, eye infections, haemorrhage, wound, skin infections, diphtheria, malaria, typhoid, liver problems, stomach ache, convulsions, constipation [5, 12, 15] |

| 64 |

Acalypha indica L. (CERSH-096) |

Annual herb | Along watercourses and Abadil Mountains | Who | Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically | Bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, scorpion stings | 0.03 | Ganglions [12] | |

| 65 |

Chrozophora oblongifolia (Delile) A. Juss. ex Spreng. (CERSH-112) |

Sub-shrub | Along watercourses | Tannoum | Lea, Ste | Ext | Stem or leaf extract is used topically | GIT problems, cathartic and emetic | 0.02 | Antimicrobial, antioxidant [38] |

| FABACEAE | ||||||||||

| 66 |

Tamarindus indica L. (CERSH-010) |

Tree | Fyfa Mountains | Tamur Hindi | Fru, See | Dec | Boiling crushed fresh fruits in water and the water is taken orally | Laxative, headache, ear pain, smallpox, scabies, sores, wounds; blood diseases, antihypertensive, liver pain, intestinal worms, bone fractures, snake bites | 0.07 | GIT diseases, skin diseases [14, 15] |

| 67 |

Alhagi graecorum Boiss (CERSH-103) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Aqool | Who | Dec | A decoction made from seeds is used orally | Anthelmintic, constipation, leprosy, anti-inflammatory, kidney stones, blood diseases, blood purifier; sexual enhancement, rheumatism | 0.04 | Cataracts, jaundice, migraine, painful joints, aphrodisiac, bilharzias, rheumatism [6] |

| 68 | Acacia oerfota (Forssk.) Schweinf. (CERSH-054) | Shrub or tree | Fyfa, mountains | Al-orfet | Lea | Inf, Pas | Soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally; leaf paste is applied topically | Severe fever, allergy, skin diseases, scorpion stings, hepatitis | 0.04 | Food poisoning, wound infections [12] |

| 69 |

Acacia tortillis (Forssk) (CERSH-031) |

Shrub or tree | Along watercourses and Fyfa Mountains | Alsomer | Bran, Roo, honey | Dec, Pas, Bur | The shoots and roots are burned and smoke is inhaled nasally; scorched leaves/roots are applied topically; toothbrush | Ulcers and deep wounds, anti-inflammatory, teeth cleaning | 0.03 | Teeth cleaning, ulcers and gangrene, wounds dry coughs, coughs, diphtheria [7, 12] |

| 70 |

Acacia ehrenbergiana Hayne (CERSH-083) |

Shrub or tree | Along watercourses | Assalam | Lea, Bar | Pas, Inf | Leaf paste is applied topically and grinded leaves in water is used to wash the eyes | GIT diseases, eye infections | 0.03 | Injuries, wound infections, eye infections [12] |

| 71 |

Acacia seyal Del. (CERSH-032) |

Shrub or Tree | Fyfa Mountains | Talh, Sanat Sayel | Bar, Gum, Roo | Inf | Soaking crushed bark or root in water and the water is taken orally | Burns, stop bleeding, Leprosy, stomach ache, after abortion | 0.03 | Stop bleeding, stomach ache, dysentery, after abortion [4, 12] |

| 72 |

Astragalus spinosus Vahl. (CERSH-077) |

Shrub | Mountains | Katad | Who | Dec | Boiling crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally | Leukaemia, skin diseases, wounds, scorpion stings | 0.02 | Scorpion stings [21] |

| 73 |

Senna alexandrina Mill. (CERSH-055) |

Shrub | Along watercourses | Sana, Eshriq | Lea, See | Dec, Pas | Leaf paste is applied topically; soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Laxative, skin diseases, GIT diseases, constipation, abdominal pain, stomach cramps | 0.07 | Injuries, skin diseases, constipation, stomach cramps, abdominal pain, gynaecological [6, 10, 12, 14] |

| 74 |

Tephrosia apollinea (Delile) Link (CERSH-011) |

Shrub | Mountains | Who | Dec | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally | Lower blood pressure, cardiac stimulation, cough, bronchitis, bone fractures, ear ache | 0.03 | Anti-bacterial; ear ache, bronchitis, cough, wounds bleeding, bone fractures, dysentery, diarrhoea [6, 12, 23] | |

| LAMIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 75 |

Plectranthus asirensis J.R.I Wood (rare, endemic) (CERSH-084) |

Shrub | Fyfa, Mountains | Shar Elkrood, sana'abur | Who | Dec, Pas | Boiling crushed fresh plant in water and the water is taken orally; paste of fresh leaves are placed topically on wounds to avoid infection | Sore throat, rash, itching, wounds, malaria | 0.03 | Intestinal disturbance, respiratory disorders, heart diseases, liver fatigue, malaria, central nervous system disorders, antiseptic, wounds [39–41] |

| 76 |

Origanum majorana L. (CERSH-056) |

Sub-shrub | Cultivated in gardens | Bardakush | Who | Dec | Boiling crushed fresh plant in water and the water is taken orally | Headaches, analgesic, asthma, cough, rheumatism | 0.04 | Analgesic during labour- inflammation of the uterus [10] |

| 77 |

Lavandula dentata L. (CERSH-067) |

Shrub | common on Mountains | Dhurum | Flow | Inf, tea | Infusion of fresh plant in water and the water is taken orally; leaf extract in tea is taken orally | Urine retention, kidney stones, ureter stones, bowel disease | 0.02 | Wounds, diuretic, carminative, antiseptic, rheumatism, bronchopulmonary infections [42] |

| 78 | Nepeta deflersiana Schweinf. ex Hedge (CERSH-118) | Perennial herb | Mountains | Shaya'a | Who | Tea | Leaf extract in tea is taken orally | Sedative or tranquilliser, stomach problems | 0.03 | Anti-inflammatory, carminative, ant-rheumatic [43] |

| 79 |

Ocimum basilicum L. (CERSH-033) |

Annual herb | Cultivated in gardens | Rayhan | Lea, Roo, See | Dec, Pas, Jui, Tea | Decoction taken orally for internal use and as spices; paste of leaves are placed topically on bruises to avoid infection; leaf paste is applied topically on snake bites; leaf and root juice are given orally to cure dysentery; leaves mixed with tea used to allay upset stomach, cold, and fever. | Fever, cough, bruises, ulcers, skin diseases, GIT diseases, diarrhoea, ringworms, ear ache, spasm, urinary diseases, kidney disorders, internal piles, anti-snake venom | 0.06 | Spasm, stomach ulcer, dysentery, respiratory, parasites, ear ache [5, 10, 12, 14] |

| 80 |

Marrubium vulgare L. (CERSH-012) |

Perennial herb | Mountains | Zagome | Lea | Pow, Dec | Leaf powder is used topically to treat wounds; decoction is used orally for treating menstrual pain and urinary diseases | Body energizer, intestinal worms, hepatitis, dyspepsia, menstrual pain, absence of a menstrual period, urinary diseases, tuberculosis, chronic bronchitis | 0.04 | Wounds, coughs [15] |

| 81 | Teucrium yemense Deflers (endemic) (CERSH-097) | Perennial herb | Al-Abadil and Fyfa Mountains | Rechal Fatima | Who | Inf | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally | Diabetes, kidney problems, anthelmintic, rheumatism | 0.03 | Insect repellent, spasm, kidney disease, rheumatism, diabetes [27] |

| LYTHRACEAE | ||||||||||

| 82 |

Lawsonia inermis L. (CERSH-085) |

Shrub | Cultivated or wild | Henna | Lea | Inf, Pow | Leaf infusion is used orally; leaf powder is used as a dye for women | Urinary tract infection, skin protection, diabetes, scorpion stings, nerve pain and nervous system disorders | 0.04 | Antifungal, urinary tract infection, skin protection, neurological and SM disorders [9, 10, 14] |

| MALVACEAE | ||||||||||

| 83 | Abutilon Pannosum (Forest.) Schlecht (CERSH-057) | Shrub | Farasan Islands and Along watercourses | Rayn | See, Bar | Ext, Inf | The extracts and infusion of seeds and bark in water are applied orally to treat most of the diseases | Sedative, fever, psoriasis, cleaning wound, skin ulcer, diabetes, anaemia, GIT diseases, diuretic, diarrhoea, urinary diseases, pulmonary problems, cough, bronchitis, vaginal infection, gonorrhoea bladder disorders | 0.06 | Diuretic, dysentery, fever, sedative, diarrhoea, cough, gonorrhoea, bronchitis, pile grumbles, pulmonary problems, cleaning wound and ulcer, vaginal infection, anaemia, diabetes, bladder problems, haemorrhoids [5, 6, 23] |

| 84 |

Malva parviflora L. (CERSH-034) |

Annual herb | Tihama plains | Khobaiza | Who | Inf. | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally; fresh leaves is chewed to treat respiratory and throat diseases | Laxative, respiratory and throat diseases, cough, bronchitis, diabetes, intestinal ulcers, hair growth, constipation, scorpion stings | 0.06 | Laxative, hair growth, cough, constipation, skin burns, urinary tract infection [13, 14, 18] |

| MELIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 85 |

Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (CERSH-066) |

Small tree | Along watercourses | Neem | Who | Dec, Pas | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally, plant past is used topically for scorpion stings | GIT diseases, gastric ulcers, scorpion stings, diabetes | 0.04 | GIT diseases, antifungal, antipyretic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, diabetes, anti-arthritic, gastric ulcer [9, 14] |

| MORACEAE | ||||||||||

| 86 |

Dorstenia foetida Schweinf. (endangered) (CERSH-098) |

Sub-shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Arkouth, Om-lakef | Lat | Inf, Lat | Infusion and latex is used topically (lotion) | GIT diseases, Leishmaniosis | 0.02 | Leishmaniosis [7] |

| 87 |

Ficus palmata Forssk (CERSH-120) |

Small tree | Fyfa Mountains | Al-Hamat | Who, lat | Lat | Fruits are eaten; latex is used topically | kidney and bladder problems, gastro-intestinal diseases, warts | 0.03 | Warts, GIT diseases [7, 14] |

| 88 |

Ficus carica L. (CERSH-087) |

Small tree | Tihama plains | Teen | Lea, fru | Dec, Pas, Lat | Fruits are eaten raw; decoction of fruit in water is taken orally; leaf paste is applied on face to lighten freckles | Laxative, kidney infections, kidney stones, GIT diseases, scorpion stings | 0.03 | Laxative, cough; lighten freckles [5] |

| MORINGACEAE | ||||||||||

| 89 | Moringa peregrina (Forssk.) Fiori (rare) (CERSH-013) | Tree | Tihama plains | Al-Ban | Lea, See oil, gums | Dec, Pas, oil | Decoction and oil from the seeds is taken orally; grind the leaves in water and wash the eye | Laxative, headache, incurable wounds, burns, abdominal and colon pains, constipation, diabetes, eyes pain, anaemia, sciatic pain, SM disorders | 0.07 | Headaches, fever, burns, wounds, colon, eyes pain, anaemia, joints pains, backache, diabetes, sciatic pain, conjunctivitis [4, 7, 10] |

| MYRTACEAE | ||||||||||

| 90 |

Myrtus communis L. (CERSH-035) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | Al-A's/Hadass | Lea, Bar | Inf, Pas | Soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally (or gargle) to cure respiratory and intestinal problems; bark is chewed; leaf paste is applied topically for skin problems | Deep wound diseases, GIT diseases, liver disorder, asthma, cough, mouth ulcers, scorpion stings, cardiovascular problems, leishmaniosis | 0.07 | Asthma, cough, respiratory problems, gangrene, pharyngitis, leishmaniosis, blood and immune system [7, 14] |

| 91 | Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. (CERSH-058) | Tree | Tihama plains | Khafour | Lea | Bur | The leaf is roasted on the heated tool and the smoke is inhaled | Abortion | 0.02 | Antimicrobial, spasmolytic [13] |

| NITRARIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 92 |

Peganum harmala L. (rare) (CERSH-065) |

Perennial herb | Tihama plains | Harmal | Who | Bur | The whole plant is used as a smoke inhalant to treat various diseases | Toothache, intestinal worms, rheumatism, skin diseases | 0.03 | Sheep fertility [18] |

| OLEACEAE | ||||||||||

| 93 |

Jasminum sambac Linn (CERSH-086) |

Small shrub | Cultivated in gardens | Al-Fill | Fru, flow | Dec, Bur | Decoction of fruit and flowers in water is taken orally; inhalation of the flowers | Intestinal worms, skin diseases, skin rashes, leprosy, ulcers, heighten sexual desire | 0.03 | Liver diseases, cirrhosis, diarrhoea, heighten sexual desire, skin rashes, sun burn, analgesic, antimicrobial, wound healing [25] |

| 94 | Olea europaea L. ssp. cuspidata (Wall. ex G. Don) Ciferri.(CERSH-059) | Tree | Mountains | Al-etem | Oil, lea, Bar | Inf, Pas lini | Soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally; fresh leaves is chewed, soaking leaves in water and water is used as mouthwash, paste and oil is used topically | Liver diseases, oesophageal irritation, ulcers, oedemas, oral thrush, dental caries, warts, skin smoothing, leprosy, smallpox, scabies, diabetes, leishmaniosis, rheumatism | 0.05 | Rheumatism, leishmaniosis, skin diseases of camels, diabetes, mellitus and hypertension, gonorrhoea [7, 12] |

| PAPAVERACEAE | ||||||||||

| 95 |

Fumaria parviflora Lam (CERSH-037) |

Annual herb | Tihama plains and Mountains | Shahtaraj | Aer | Inf, lini | Soaking crushed aerial parts in water and the water is taken orally | Intestinal worms, diuretic, urinary diseases, blood purifier, spleen disorder, leprosy, scabies, eczema, acne, lungs diseases | 0.05 | Diuretic, laxative, blood purifier, scabies, eczema, acne, skin disorders [5] |

| PLANTAGINACEAE | ||||||||||

| 96 |

Plantago major L. (CERSH-014) |

Perennial herb | Tihama plains | Lissan Jamal | Roo, lea | Dec, Pow | Decoction of fresh plant in water is taken orally, leaf powder is used topically for skin diseases | Urinary diseases, blisters, boil, wounds, malaria, scorpion stings | 0.03 | Blisters, boil and wounds [4] |

| PLUMBAGINACEAE | ||||||||||

| 97 | Limonium axillare (Forssk.) O. Kuntze (CERSH-099) | Shrub | Tihama plains and Farasan Islands | Qattaf | Who | Dec | Decoction of fresh plant in water is taken orally | Central nervous system depression | 0.02 | Diarrhoea, astringent [6, 23] |

| POACEAE | ||||||||||

| 98 |

Saccharum spontaneum L. (CERSH-038) |

Perennial grass | Along watercourses | Half | Who | Jui | Juice of whole plant is used orally | Urinary diseases, skin diseases, tuberculosis | 0.03 | Anaemia, vomiting, abdominal disorders, obesity, astringent, emollient, diuretic, tonic, dyspepsia, burning sensation, piles, respiratory troubles, antidiarrheal, anti-urolithiatic activity [44] |

| 99 | Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) Willd. ex Asch. & Schweinf. (CERSH-015) | Annual grass | Tihama plains and Mountains | na'eem el-saleeb, rigl Al-harbaya | Roo, lea | Pas, Ext, Dec | The leaf paste in water is applied topically; Ext of the plant is taken orally; decoctions of seeds is given orally for postnatal problems | GIT diseases, gastric ulcer, kidney diseases, biliary and urinary ailments, skin inflammation, small pox, lesion, sores, postnatal problems | 0.03 | Astringent, bitter tonic, anti-anthelmintic, wounds, smallpox, GIT, biliary and urinary ailments, polyurea fevers, spasm of maternity, renal infections, immune-deficiency, gastric ulcers [45, 46] |

| POLYGONACEAE | ||||||||||

| 100 |

Rumex nervosus Vahl. (CERSH-100) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Al-athrub | Lea, Roo, See | Pow | Seeds roasted and used topically for the treatment of dysentery and snake bites; leaves and seeds are eaten raw; chewing of the leaves | Appetizer, astringent, diarrhoea, diuretic, stoop bleeding, burns, dental pain, diabetes, dysentery, scorpion and snake bites | 0.06 | Diabetes, asthma, diarrhoea, diuretic, dental pain, wounds, dysentery, scorpion stings and snake bites, appetizing, astringent [5, 7, 47] |

| 101 |

Rumex vesicarius L. (CERSH-088) |

Annual or perennial, rhizomatous herb | Al-Hashar Mountains | Al-Hommad | See, lea | - | The leaves and seeds are crushed and eaten raw | Wounds, spasm, muscle cramp, diuretic, dysentery, toothache, scorpion stings and snake bites | 0.07 | Toothache, antiemetic, leukaemia, breast, lung, central nervous system cancers, scorpion stings [6, 7, 13, 19] |

| 102 |

Emex spinosa (L.) Campd. (CERSH-060) |

Annual herb | Fyfa Mountains | Hambaaz | Lea, Roo | - | The leaves and roots are edible (chewing) | Dyspepsia, GIT disorders | 0.03 | Appetizer, dyspepsia, diuretic [13] |

| RANUNCULACEAE | ||||||||||

| 103 | Clematis wightiana Wall. ex Wight & Arn. (CERSH-016) | Climber | Fyfa Mountains | Threeja, Alharya | Who | Pas | The leaf paste in water is applied topically | Skin diseases, leprosy, cardiac depression, varicose veins, bone fracture, rheumatism | 0.03 | Rheumatism, headaches, varicose veins, syphilis, gout, bone problems [23] |

| RHAMNACEAE | ||||||||||

| 104 | Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Willd (CERSH-113) | Tree | Fyfa mountains and along watercourses | Seder, Arq | Lea, Fru, See | Dec, Inf. | Decoction of the plant is used orally for GIT problems; crushed seed kernels are eaten raw; chewing fresh leaves to relieve mouth problems | Scabies, measles, sores, wounds, lice, hair tonic, allergy, rabies, antidandruff; toothache, stomach ache, liver problems, headache, insect bites, leishmaniosis, spasm, rheumatism, urinary troubles, diabetes, anaemia | 0.08 | Duodenum and stomach ache, allergy, chest pain; scabies, itching, sores, wounds, bruises; insect bites, diabetes, spasm, strengthening hairs, antidandruff, mouth problems [4, 5, 7, 13, 21, 48] |

| RHIZOPHORACEAE | ||||||||||

| 105 |

Rhizophora mucronata Lam. (CERSH-039) |

Small tree | Tihama plains | Kindale | Bar, Roo, lea, fru, flow | Dec, Pas | Soaking crushed plant in water and the water is taken orally | Diabetes, GIT diseases | 0.02 | Diabetes, diarrhoea, anti-inflammatory hepatitis [11] |

| RUTACEAE | ||||||||||

| 106 |

Ruta chalepensis L. (CERSH-061) |

Perennial herb | Cultivated in gardens or wild in Fyfa Mountains | El - shathab | Lea, Ste | Dec | Soaking crushed leaves in water and the water is taken orally | Headache, fever, ear pain, vitiligo, measles, snake bites, menstrual pain, skin diseases, rheumatism, GIT diseases | 0.08 | Snake bites, ear, neurological, diphtheria, respiratory diseases [7, 12, 14] |

| RUBIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 107 |

Coffea arabica L (CERSH-040) |

Small tree | Cultivated on Mountains | Bone | See | Pow | Heat crushed seeds and apply topically | Fever, tonic, headache, malaria, kidney disorders, kidney inflammation | 0.03 | Haemorrhage, asthma, flu, atropine-poisoning, sores, stimulants fever, headache, jaundice, malaria, vertigo migraine, narcosis, nephritis [5] |

| SALVADORACEAE | ||||||||||

| 108 |

Salvadora persica L. (CERSH-017) |

Shrub or Small tree | Tihama plains and foothills | Al-Arak | Fru, Roo | Cook | Roots are used as toothbrush; fruits are eaten raw; cooked leaves for kidney problems | Teeth cleaning, kidney diseases and stones, spleen disorder, rheumatism, snake bites | 0.05 | Snake bites, epilepsy, rheumatism, skin diseases, toothbrush, gonorrhoea, spleen troubles, stomach ulcer [7] |

| SAPINDACEAE | ||||||||||

| 109 |

Dodonaea viscosa Jacq (CERSH-101) |

Small tree | Fyfa Mountains | Shath | Lea | Pas, Pow | Leaf powder is used for treating toothache; leaf paste is applied topically for skin problem | Rheumatism, toothache, wounds, burns, malaria, leishmaniosis | 0.03 | Toothache, burns, wounds leishmaniosis [4, 6, 7] |

| SOLANACEAE | ||||||||||

| 110 | Solanum incanum L (CERSH-063) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains And foothills |

Nagum, Al-hadak | Fru, Roo, lea | Pas, Dec, Pou | Leaf paste is applied topically as poultice on skin diseases; decoction from berries, leaves and roots is taken orally; berries boiled in oil and the oil is used for earache | Sever fever, malaria, leishmaniosis, earache, wounds, bruise, rashes, warts, dyspepsia, ulcers, carbuncles, stomach-ache, painful menstruation | 0.07 | Malaria, leishmaniosis, bruised fingers, wounds, onchocerciasis, earache, dyspepsia, pleurisy, rheumatism, pneumonia, haemorrhoids [5, 7, 12] |

| 111 |

Datura stramonium L. (CERSH-018) |

Annual herb | Common along watercourses | Daturah, /ain el bakar | Who | Pas | Leaf paste is placed on bleeding wounds and skin diseases; leaves are dried, crushed, heated and applied topically to the sting point | Headaches, epilepsy, rabies, asthma, earache, sores, vitiligo, pruritic, GIT diseases, wounds, scabies, hair-fall, cough, skin inflammation, rheumatism, bronchitis, scorpion stings | 0.08 | Dermatitis, sores and vitiligo, wounds, stomach ache, scorpion stings [4, 15, 21, 49] |

| 112 |

Hyoscyamus muticus L. (CERSH-089) |

Shrub | Tihama plains | As -sakran | Lea, See | Pas, Pou, Ext, Bur | A crushed leaves is applied topically as a poultice to relieve pain; whole plant is used as a smoke inhalant to treat various diseases, grind the leaves in water and wash the eye | Asthma, toothache, eyes problems, rheumatism, spasm | 0.03 | Eyes problems, muscles, asthma intoxicating effect [47] |

| 113 |

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (CERSH-062) |

Shrub | Fyfa Mountains | Sem Alfa'ar/Alobeb | Lea, Fru, Roo | Pas, Inf, Ext, Pou | Paste from berries and leaves are applied as a poultice to ulcers, skin diseases and eyes pain; soaking crushed root in water and the water is taken orally (gargle) | Tranquilizer, intestinal worms and ulcers, dyspepsia, skin chronic inflammation, eye pain, asthma, bronchitis, urinary diseases, scorpion stings, aphrodisiac, toning up the uterus of women | 0.09 | Ulcers, chronic dermatitis, psoriasis, breast, colon and liver cancers, asthma, leukaemia, aphrodisiac, sexual disorders, eye pains bronchitis,, gynaecological disorders [5–7, 12, 13, 19] |

| TAMARICACEAE | ||||||||||

| 114 |

Tamarix nilotica Ehrenb (CERSH-041) |

Shrub or small tree | Tihama plains | Tarfaa | Lea, seed's oil | Pas, Pou | Topically to cure wounds and skin problems | Wounds, anti-inflammatory, varicose veins | 0.04 | Dermatitis, leg varices [7, 13] |

| 115 |

Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst (CERSH-019) |

Tree | Tihama plains and Farasan Islands | Al -Athl | Bran, lea, Roo, Bar | Dec, Bur, Pas, Pou | Decoction of the roots and branches is used orally, fumigation of the leaves is beneficial in flu; paste form bark is used topically on wounds. | Astringent, cold, flu, tuberculosis, spleen diseases, stomach ache, hepatitis, leprosy, wound infection, eczema, smallpox, aphrodisiac, uterus problems | 0.06 | Astringent, wound, eczema, leprosy, smallpox stomach-ache, hepatitis, tuberculosis, cold, flu, spleen diseases, aphrodisiac, germicidal effect, tetanus [4, 5, 50] |

| TILIACEAE | ||||||||||

| 116 |

Grewia tenax (Forssk.) Fiori (CERSH-122) |