Key Points

Question

Do search engine queries for chest pain correlate with known epidemiology of coronary heart disease?

Findings

In this study, searches for chest pain and variants closely mirrored the known epidemiology for coronary heart disease in regards to state-by-state variation, seasonal variation, and diurnal variation.

Meaning

Search engine query data may provide an important new resource for cardiovascular research and patient care.

This study investigates the correlation of online symptom search for chest pain using Google Trends with disease prevalence of coronary heart disease.

Abstract

Importance

Online search for symptoms is common and may be useful in early identification of patients experiencing coronary heart disease (CHD) and in epidemiologically studying the disease.

Objective

To investigate the correlation of online symptom search for chest pain with disease prevalence of CHD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective study used Google Trends, a publicly available tool that provides relative search frequency for queried terms, to find searches for chest pain from January 2010 to June 2017 in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. For the United States, results were obtained by state. These data were compared with publicly available prevalence data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of CHD hospitalizations by state for the same period. The same terms were used to evaluate seasonal and diurnal variation. Data were analyzed from July 2017 to October 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Correlation of search engine query for chest pain symptoms with temporal and geographic epidemiology.

Results

State-by-state comparisons with reported CHD hospitalization were correlated (R = 0.81; P < .001). Significant monthly variation was appreciated in all countries studied, with the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia showing an 11% to 39% increase in search frequency in winter months compared with summer months. Diurnal variation showed a morning peak for search between local time 6 am and 8 am, with a greater than 100% increase seen in peak searching hours, which was consistent among the 3 countries studied.

Conclusions and Relevance

Relative search frequency closely correlated with CHD epidemiology. This may have important implications for search engines as a resource for patients and a potential early-detection mechanism for physicians moving forward.

Introduction

Increasingly, patients are turning to online search engines such as Google to evaluate their symptoms prior to turning to a physician; 59% of US adults attest to looking online for health information, with 80% starting with a search engine.1 The Institute of Medicine has identified online search data, and specifically Google Trends, a free publicly available tool for analyzing search data, as a valuable source for health sciences research.2 A wide variety of studies have used Google Trends, including topics such as mental health3 and infectious diseases.4 A review of the use of Google Trends in the medical literature noted that only 16% of the 70 studies identified focused on noncommunicable diseases.5 The studies identified also tended to focus on searches for known disease states as opposed to symptoms of noncommunicable disease.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) has been shown to exhibit geographic,6 seasonal,7 and diurnal8,9 variation. The cardinal symptom of CHD is angina, and given the commonality of online searches for symptoms, we sought to investigate the association of chest pain symptom search with the epidemiology of CHD. We hypothesized that search frequency for chest pain obtained using Google Trends would correlate strongly with previously reported epidemiology of CHD.

Methods

Search Terms

With the goal of identifying searches most likely to be related to cardiovascular disease, several possible symptoms were considered, including angina, dyspnea, diaphoresis, and weakness. Chest pain has been found to have the greatest sensitivity for CHD in both the emergency department and outpatient settings.10,11 Therefore, chest pain and synonyms were chosen by the authors as the symptom of investigation. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. Due to the deidentified nature of the data used in the study, informed consent for this study was not obtained.

Data Acquisition

Google Trends provides an unbiased sample of Google search data. Each data point represents the proportion of searches for the queried item by the total searches in the geography of the area selected during the time range selected. This yields a relative search frequency, and results are reported as a scaled range from 0 to 100. Each proportion can represent from thousands to millions of searches taking place in the specified time frame and geographic region. Query details are reported in the Table in a manner consistent with that recommended by Nuti et al.5

Table. Google Trends Search Queries.

| Access Date | Time Period Queried | Search Syntax | Geographic Areas of Search | Query Category | Quantification of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic | |||||

| December 8, 2017 | January 2012 to December 2014 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US | All | State by state |

| December 8, 2017 | January 2011 to December 2013 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US | All | State by state |

| December 8, 2017 | January 2010 to December 2012 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US | All | State by state |

| Seasonal | |||||

| August 19, 2017 | July 1, 2012, to June 30, 2017 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US, UK, and Australia | All | Weekly |

| Diurnal | |||||

| August 18, 2017 | August 11, 2017, to August 18, 2017 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US, UK, and Australia | All | Hourly |

| August 28, 2017 | August 21, 2017, to August 28, 2017 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US, UK, and Australia | All | Hourly |

| December 8, 2017 | December 1, 2017, to December 8, 2017 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US, UK, and Australia | All | Hourly |

| December 17, 2017 | December 10, 2017, to December 17, 2017 | Chest pain, chest pressure, chest tightness, and angina | US, UK, and Australia | All | Hourly |

Abbreviations: UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

US Geographic Variation

Publicly available data on annual CHD hospitalization rate per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Atlas of Heart and Stroke Statistics from January 2010 to December 2014.12 A query was then placed for chest pain and synonyms in Google Trends during the same period the CDC data were collected. These values were compared. A similar query was placed during the same time frame for knee pain to be used as a control. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated.

Monthly Variation

A query was placed to determine the volume of searches for chest pain symptoms in 3 large, predominantly English-speaking countries from July 2012 to July 2017 (Table). From this, a multivariate linear regression model was constructed, with month and year as predictor variables and relative search frequency as the outcome variable.

Diurnal Variation

Queries were placed to determine the volume of searches in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia for 4 one-week intervals (Table). Hourly data were only available for the 7 days before the query date. For each country, hourly data were adjusted to the local time of the most populous time zone in each country, eg, Eastern Standard Time in the United States. Means for each hour in each country were calculated and compared via analysis of variance.

Statistical Analysis

For geographic variation, correlation was evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficient with 2-tailed t tests to determine statistical significance. For monthly variation, a multivariable linear regression was performed to evaluate the correlation between month, year, and search frequency. In regards to diurnal variation, means for each hour were calculated and compared using 1-way analysis of variance to determine significance. Statistical analysis was performed in R version 3.4.3 (The R Foundation).

Results

Overall Search Frequency

Of 4 keywords used to describe chest pain symptoms, “chest pain” was searched 4.5-fold more than “angina” and 13-fold more than “chest pressure” and “chest tightness.” As a comparator, these search terms were collectively queried 1.6-fold more than “knee pain.”

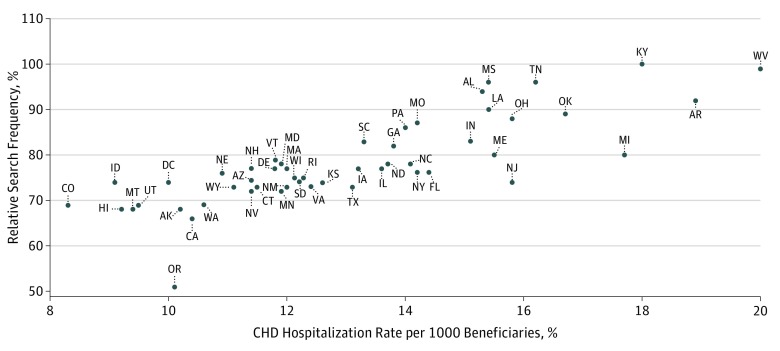

US Geographical Variation

The Pearson correlation coefficient for CDC data for each state from January 2012 to December 2014 and the search frequency in each state over the same period was calculated to be 0.81 (P < .001) (Figure 1). Kentucky residents searched most frequently, approximately twice as frequently as residents of Oregon, the state with the least relative searches. The Pearson correlation coefficient from January 2011 to December 2013 was 0.81 (P < .001) and from January 2010 to December 2012 was 0.78 (P < .001). As a comparison, the correlation coefficient for knee pain searches from January 2012 to December 2014 was 0.31 (P < .001) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Relative Search Frequency and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Prevalence in the United States.

The scatter chart shows the relative search frequency for each state plotted with the CHD hospitalization rate reported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for each state from January 2012 to December 2014. Relative search frequency signifies the proportion of searches for the queried term by the total searches in the geography of the area selected during the time range selected.

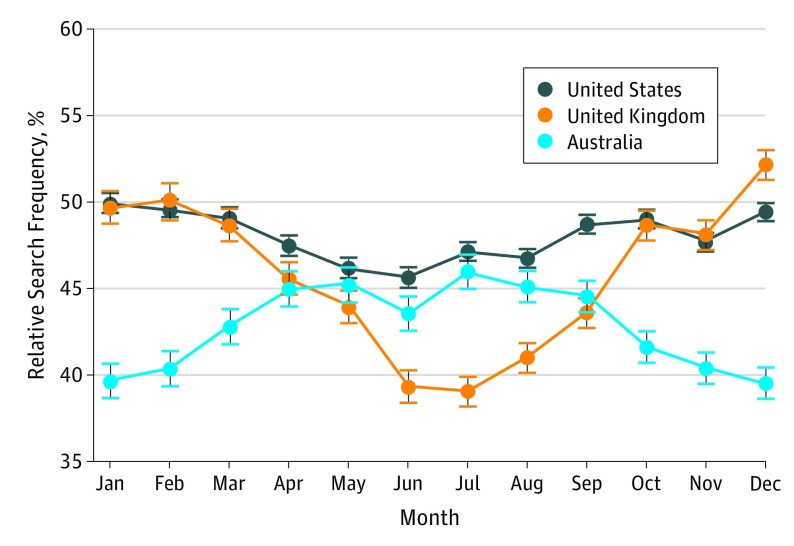

Monthly Variation

Searches for chest pain symptoms were found to have significant monthly differences in all 3 countries evaluated (Figure 2). In the United States and United Kingdom, searches peaked in the winter months and had a trough during the summer. The peak month in the United States was January, with an 11% increase over the trough month of June. In the United Kingdom, the peak month was December, which had a 39% increase in searches compared with the trough month of July. In Australia, the peak month for searches was July, which had a 19% increase compared with the trough month of December.

Figure 2. Monthly Variation of Symptom Search.

The least-squares mean of relative search frequency of chest pain symptoms monthly from January 2012 to December 2017 for the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. All countries had a significant monthly variation in search frequency when means were compared using analysis of variance.

Diurnal Variation

Chest pain searches were found to consistently peak between 6 am and 8 am local time, with a nadir in the late afternoon between 2 pm and 6 pm for all 3 countries studied. In the United States, searches peaked at 7 am, with a 110% increase from the nadir between 2 pm and 4 pm. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, searches peaked at 6 am, a 189% increase over the nadir. In Australia, searches peaked at 7 am, a 157% increase over the nadir between 3 pm and 5 pm (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Analysis of variance of the calculated means was statistically significant for difference.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that in regard to chest pain symptoms, the frequency of searches correlates strongly with previously reported CHD epidemiology. To our knowledge, our study is the first to identify a correlation of chest pain symptom searches online with disease prevalence in cardiovascular disease. Surveillance of online search engine activity may grow to become an important, emerging data source for cardiovascular research and care.

State-by-state geographic variation of CHD hospitalizations correlated well with searches for related symptoms in all 3 of the time intervals studied. This identifies a linear relationship between search frequency and disease burden at a population level. As the most recent data publicly available from the CDC is a minimum of 2 years old and Google Trends data are available nearly contemporaneously, it could potentially provide a more timely and cost-effective data source for public health researchers.

At both a seasonal and diurnal scale, searches were found to reflect previously reported temporality for CHD. This likely reflects people searching for symptoms at the time they are experiencing them. Search engines could then potentially provide a first point of contact to intervene for patients experiencing life-threatening symptoms of CHD. Google has identified the importance of online symptom search and has worked with Harvard Medical School and the Mayo Clinic to try to improve the accuracy and prioritize medically accurate information.13 They have also started screening for depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 following searches relating to depression.14 If screened positive, resources for suicide prevention are made available. A similar model could be applied to CHD, where a screening questionnaire could identify those in need of more resources, such as the nearest percutaneous coronary intervention–capable center or an online triage with health care physicians. This has the distinct advantage of including all individuals using online search, even if they would otherwise be unable or unwilling to immediately seek medical care. While challenges to such a system are immense, it could provide an avenue to intervene at an earlier stage at large scale.

Limitations

This study had limitations. The terms used for symptom search in this study are not isolated to CHD and could represent a wide variety of pathology. Search engine data are anonymized, and motivation for particular search terms cannot guarantee the person searching is experiencing those symptoms. The granularity of the temporal information available (ie, hourly, daily, and weekly) is variable. Further clinical course or outcomes of individuals who searched for these terms cannot be determined but would be of great interest moving forward.

Conclusions

Overall, our study highlights the use of search engine data as a valuable resource in the study of cardiovascular disease. It mirrors reported epidemiology for coronary disease, with the distinct advantages of being nearly contemporaneous and inexpensive. Online searching may be an initial contact point for patients experiencing symptoms and may potentially be used to expedite necessary medical evaluation. Care needs to be taken to ensure appropriate information is provided to patients searching for these potentially serious symptoms.

eFigure 1. Relative search frequency for knee pain and coronary heart disease prevalence in the United States.

eFigure 2. Diurnal search frequency variation.

References

- 1.Fox S, Duggan M Health online 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2018.

- 2.Institute of Medicine Committee on a National Surveillance System for Cardiovascular and Select Chronic Diseases A Nationwide Framework for Surveillance of Cardiovascular and Chronic Lung Diseases. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunn JF III, Lester D. Using Google searches on the internet to monitor suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2-3):1218-1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsberg J, Mohebbi MH, Patel RS, Brammer L, Smolinski MS, Brilliant L. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature. 2009;457(7232):1012-1014. doi: 10.1038/nature07634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuti SV, Wayda B, Ranasinghe I, et al. The use of Google Trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, and Stroke Council . Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873-898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fares A. Winter cardiovascular diseases phenomenon. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(4):266-279. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.110430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behar S, Reicher-Reiss H, Goldbourt U, Kaplinsky E. Circadian variation in pain onset in unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67(1):91-93. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90107-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller JE, Stone PH, Turi ZG, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(21):1315-1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511213132103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devon HA, Rosenfeld A, Steffen AD, Daya M. Sensitivity, specificity, and sex differences in symptoms reported on the 13-item acute coronary syndrome checklist. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000586. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayerbe L, González E, Gallo V, Coleman CL, Wragg A, Robson J. Clinical assessment of patients with chest pain: a systematic review of predictive tools. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:18. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0196-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Interactive Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke. http://nccd.cdc.gov/DHDSPAtlas. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 13.Pinchin V. I’m feeling yucky: (searching for symptoms on Google. https://www.blog.google/products/search/im-feeling-yucky-searching-for-symptoms/. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- 14.Giliberti M. Learning more about clinical depression with the PHQ-9 questionnaire. https://www.blog.google/products/search/learning-more-about-clinical-depression-phq-9-questionnaire/. Accessed February 16, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Relative search frequency for knee pain and coronary heart disease prevalence in the United States.

eFigure 2. Diurnal search frequency variation.