Abstract

Importance

Patients with psoriasis may experience comorbidities involving cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, uveitis, psychiatric disturbances, and metabolic syndrome. However, the association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been largely unclear.

Objective

To investigate the association of psoriasis with IBD.

Data Sources

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for relevant studies from inception to January 17, 2018.

Study Selection

Case-control, cross-sectional, or cohort studies that examined either the odds or risk of IBD in patients with psoriasis were included. No geographic or language limitations were used in the search.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines were followed for data extraction. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to evaluate the risk of bias of included studies. Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis were analyzed separately and random-effects model meta-analysis was conducted. A subgroup analysis was performed on psoriatic arthritis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The risk and odds of IBD, Crohn disease, and ulcerative colitis in patients with psoriasis.

Results

A total of 5 case-control or cross-sectional studies and 4 cohort studies with 7 794 087 study participants were included. Significant associations were found between psoriasis and Crohn disease (odds ratio, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20-2.40) and between psoriasis and ulcerative colitis (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.49-2.05). Patients with psoriasis had an increased risk of Crohn disease (risk ratio, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.65-3.89) and ulcerative colitis (risk ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.55-1.89).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that psoriasis is significantly associated with IBD. Gastroenterology consultation may be indicated when patients with psoriasis present with bowel symptoms.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 9 studies comprising more than 7 million patients examines the association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease?

Findings

This meta-analysis included 5 case-control or cross-sectional studies with 1 826 677 individuals; patients with psoriasis had 1.70-fold increased odds of Crohn disease and 1.75-fold increased odds for ulcerative colitis. The meta-analysis also included 4 cohort studies with 5 967 410 individuals; patients with psoriasis had a 2.53-fold increased risk of developing Crohn disease and a 1.71-fold increased risk of developing ulcerative colitis.

Meaning

Psoriasis appears to be associated with inflammatory bowel disease; gastroenterology consultation may be indicated when patients with psoriasis present with bowel symptoms.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic immune-mediated disorder affecting approximately 0.5% to 11.4% of adults and approximately 1.4% of children worldwide.1,2 Psoriasis has been characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous scaling plaques with a typical relapsing and remitting course.3,4 Even with proper treatments, psoriasis can only be controlled but cannot be cured.5 Genetic and environmental factors are considered involved in the possible causes of psoriasis.6 Previous genome-based analysis revealed that specific genes (eg, PSORS1 [OMIM 177900], IL12B [OMIM 161561], and IL23R [OMIM 607562]) are predisposing factors for psoriasis.7 Psoriasis has been linked with a variety of comorbidities including cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, uveitis, psychiatric disturbances, and metabolic syndrome and its relevant components (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and type 1 and 2 diabetes), resulting in impaired quality of life and shortening of life expectancy.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract that requires long-term management.19 Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the 2 main forms of IBD.20 During the past 2 decades, the incidence of IBD has increased in developing countries, with an annual increase of 11.1% for CD and an annual increase of 14.9% for UC.21 Accumulating evidence indicates that genetic susceptibility may play an essential role in the dysregulated inflammatory reaction of IBD.22,23 Crohn disease frequently causes the infiltration and destruction of all intestinal wall layers along the digestive tract, while UC primarily involves the colon and rectum, with mucosal and submucosal invasion.24 Patients with IBD often experience recurrent loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and body weight loss.25,26,27

Previous studies have shown common genotypes, clinical course, and immunologic features shared by psoriasis and IBD.7 Genetic correlation between psoriasis and IBD, including chromosomal locus 6p21 and the IL23R and IL12B genes, has been identified.7,28,29,30 As to the shared immunologic features, increased levels of IL-17 were found in both IBD and psoriasis.31,32,33 However, the association between psoriasis and IBD was largely unclear. In this study, we aimed to systematically analyze the association of psoriasis with IBD.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies (including case-control, cross-sectional, and cohort studies) on the association of psoriasis with IBD. This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)34 and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.35

Literature Search

We searched MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase from inception to January 17, 2018, for relevant studies. The search strategy is shown in the eTable in the Supplement. No language or geographic restrictions were imposed.

Study Selection

We included studies that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) observational studies examining the association of psoriasis with IBD, including cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies; (2) the study participants were humans; and (3) the case group was composed of patients with psoriasis and the control group was composed of individuals without psoriasis. Two of us (Y.F. and C.-H.L.) independently screened the search results and assessed their eligibility by scanning the titles and abstracts of citations. We checked the full text of potentially eligible studies and included studies that met the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was resolved by consulting another one of us (C.-C.C.).

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

The following data were extracted from the included studies: first author, year of publication, country, study design, and quantitative estimates including odds ratio (OR) and risk ratio (RR) with 95% CIs on the association of psoriasis with IBD. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to assess the risk of bias of included studies.36 The following 8 domains were evaluated for included case-control studies: adequacy of case definition, representativeness of cases, selection of controls, definition of controls, comparability of cases and controls, ascertainment of exposure, same method of ascertainment for cases and controls, and nonresponse rate. The following 8 domains were evaluated for included cohort studies: the representativeness of exposed cohort, selection of nonexposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, outcome of the interest not present at start of study, comparability of cohorts, assessment of outcome, follow-up duration, and adequacy of follow up of cohorts.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted by using the Review Manager, version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration). We calculated the pooled OR with 95% CI for included case-control and cross-sectional studies, and calculated the pooled RR with 95% CI for included cohort studies. If there were multiple risk estimates provided in the study report, we adopted the risk estimates with the most adjusted confounders. The statistical heterogeneity across the included studies was assessed by using the I2 statistic. We considered an I2 of greater than 50% to represent substantial heterogeneity. We adopted the random-effects model in conducting meta-analyses as we anticipated clinical heterogeneity. We conducted a subgroup analysis on patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Results

Characteristic of Included Studies

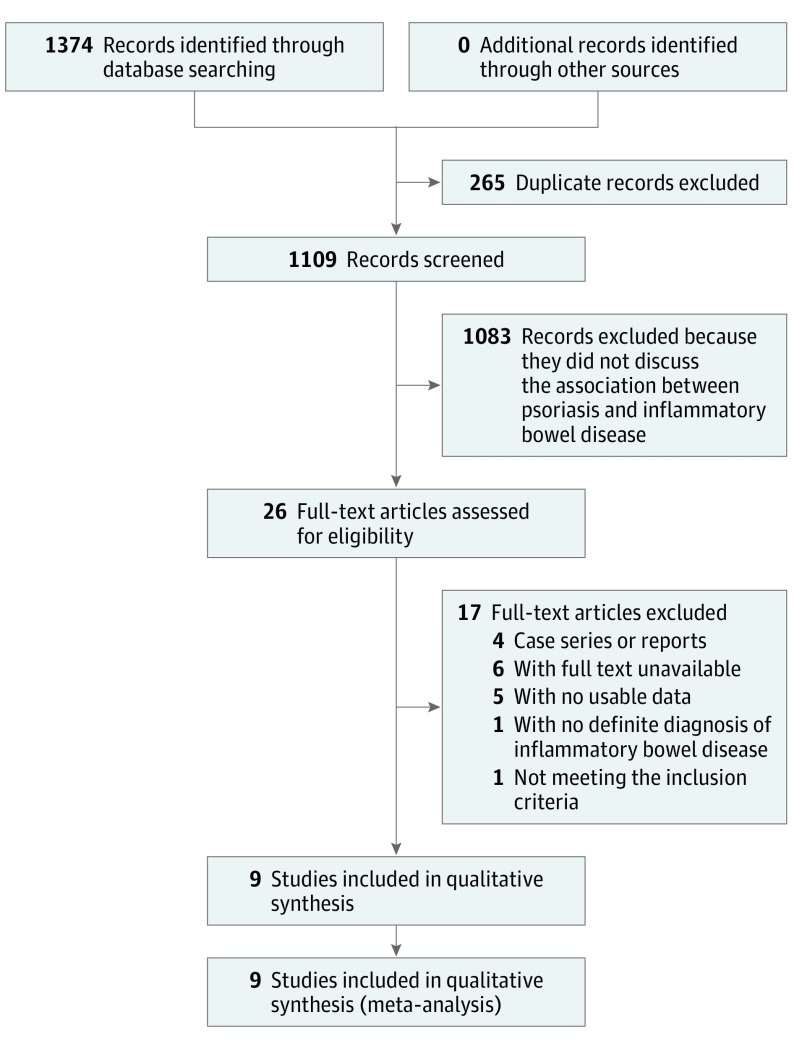

The PRISMA study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. Our search identified 1109 records after removing duplicates. After scanning the titles and abstracts, 1083 citations were excluded. After examining the full text, 5 case-control or cross-sectional studies and 4 cohort studies with a total of 7 794 087 study participants were included in this study.37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 The characteristics of the included case-control or cross-sectional studies are listed in Table 1,37,38,39,40,43 and the characteristics of the cohort studies are listed in Table 2.41,42,44,45

Figure 1. PRISMA Study Flowchart.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Case-Control and Cross-Sectional Studies.

| Source | Study Design | Case Group | Control Group | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn Disease | Ulcerative Colitis | ||||

| Cohen et al,37 2009 | Case-control | 12 502 Patients with psoriasis (6516 males and 5986 females) | 24 285 Age- and sex-matched controls (12 197 males and 12 088 females) | 2.49 (1.71-3.62) | 1.64 (1.15-2.33) |

| Tsai et al,39 2011 | Case-control | 51 800 Patients with psoriasis (31 923 males and 19 877 females) | 207 200 Controls matched for age, sex, and urbanization level of residential area | 0.70 (0.52-0.94) | NA |

| Augustin et al,38 2010 | Cross-sectional | 33 981 Patients with psoriasis | 1 310 090 Healthy controls | 2.06 (1.83-2.31) | 1.95 (1.76-2.17) |

| Zohar et al,43 2016 | Case-control | 3161 Patients with psoriatic arthritis | 31 610 Age- and sex-matched randomly selected patients | 2.20 (1.59-3.03) | 1.91 (1.21-3.00) |

| Wu et al,40 2012 | Case-control | 25 341 Patients with ≥2 diagnosis codes for any psoriatic disease | 126 705 Controls matched for age, sex, and length of enrollment | 1.80 (1.50-2.16) | 1.53 (1.30-1.80) |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; OR, odds ratio.

Table 2. Characteristics of Included Cohort Studies.

| Source | Study Design | Exposed Group | Control Group | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn Disease | Ulcerative Colitis | ||||

| Egeberg et al,42 2016 | Cohort study | 75 209 Patients with psoriasis (36 212 males and 38 997 females) | 5 478 891 Individuals in the reference population | 1.94 (1.66-2.26) | 1.72 (1.56-1.90) |

| Charlton et al,45 2018 | Cohort study | 6783 Patients with psoriatic arthritis | 27 132 Individuals in the general population | 2.96 (1.46-6.00) | 1.30 (0.66-2.56) |

| Li et al,41 2013 | Cohort study | 2755 Women with psoriasis | 171 721 Women without psoriasis | 3.86 (2.23-6.67) | 1.17 (0.41-3.36) |

| Manos et al,44 2017 | Cohort study | 1012 Children with psoriatic arthritis | 203 907 Controls matched for age, sex, and date of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis diagnosis | 1.50 (0.21-10.68) | 3.45 (0.86-13.90) |

Abbreviation: RR, risk ratio.

Risk of Bias of Included Studies

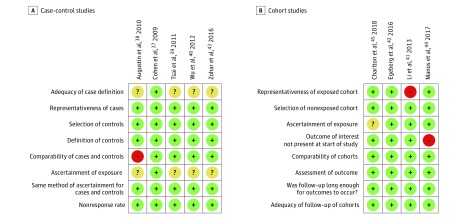

The risk of bias of included case-control and cohort studies was summarized in Figure 237,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 and Figure 3.37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 Of 5 included case-control studies, 4 studies were rated with unclear risk in the domains of adequacy of case definition and ascertainment of exposure domains.38,39,40,43 The main reason for an unclear risk in the adequacy of case definition domain was that most studies defined the case group by using corresponding International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes. Moreover, the reason for an unclear risk of bias in the ascertainment of exposure domain was that most studies used the medical record as their only reference for ascertainment of exposure. We rated the study by Augustin et al38 at high risk in the comparability of cases and controls domain because there was no controlling for confounders. All 4 included cohort studies were rated at low risk of bias in the adequacy of follow-up of cohorts domain, as the length of follow-up exceeded 1 year in all 4 studies.41,42,44,45 We rated the study by Li et al41 at high risk in the domain of representativeness of exposed cohort because the study participants were from a specific group limited to nurses. We also rated the study by Manos et al44 at high risk of bias in the domain of outcome of the interest not present at start of the study because the study did not report relevant information.

Figure 2. Risk of Bias of Included Studies.

A, Risk of bias of included case-control studies. B, Risk of bias of included cohort studies. A green dot denotes low risk of bias, yellow for unclear risk of bias, and red for high risk of bias.

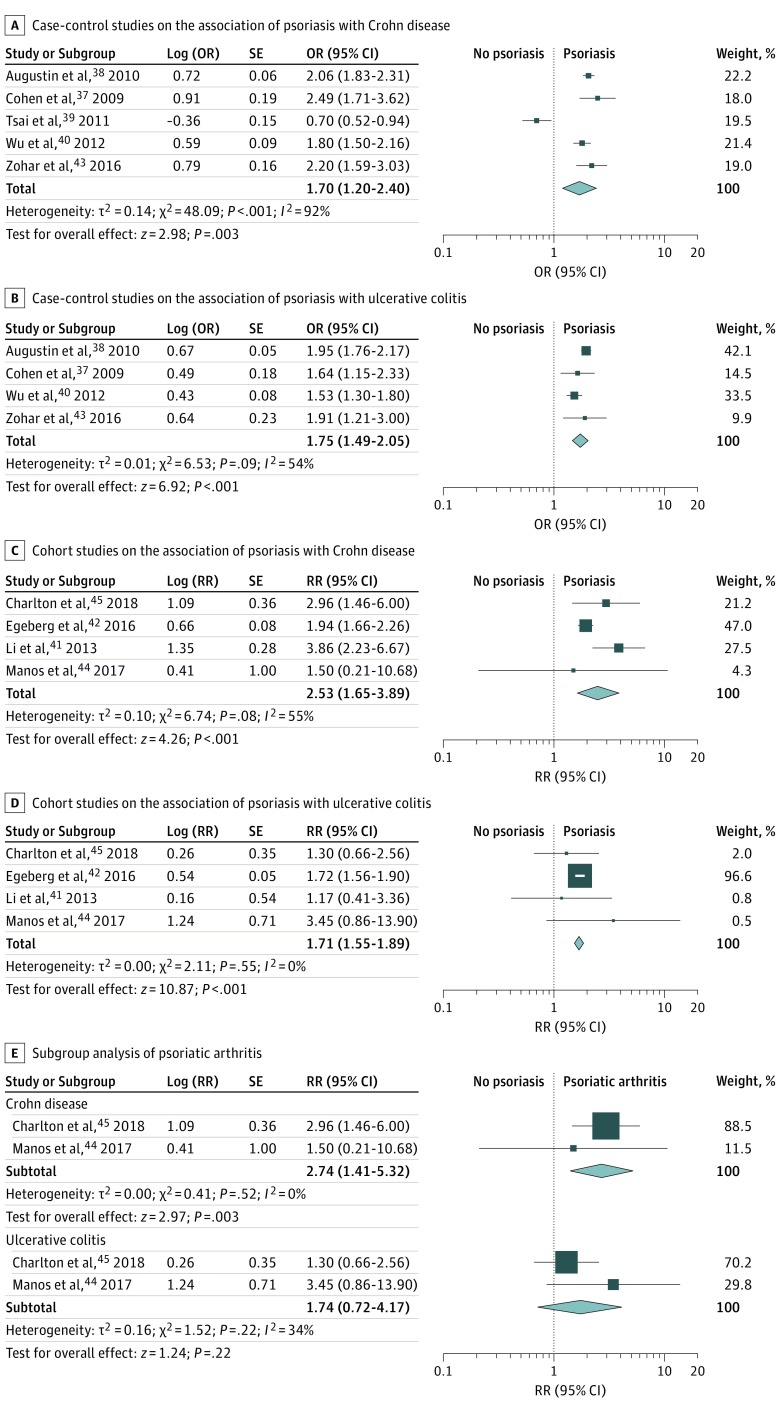

Figure 3. Forest Plots of the Association of Psoriasis With Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis, and Subgroup Analysis of Psoriatic Arthritis.

A, Case-control studies on the association of psoriasis with Crohn disease. B, Case-control studies on the association of psoriasis with ulcerative colitis. C, Cohort studies on the association of psoriasis with Crohn disease. D, Cohort studies on the association of psoriasis with ulcerative colitis. E, Subgroup analysis of psoriatic arthritis. The size of the data markers reflects the weight. Data were pooled separately by study design type using random-effects models; the inverse variance technique was used for pooling of measures of effect.

Association of Psoriasis With IBD

Except for the study by Tsai et al,39 all of the other 4 case-control studies demonstrated an increased odds of CD in association with psoriasis.37,38,40,43 We identified substantial statistical heterogeneity across these 5 studies (I2 = 92%). As shown in Figure 3A,37,38,39,40,43 the meta-analysis illustrates a significant association of psoriasis with CD (pooled OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20-2.40).

Four included case-control studies provided data regarding the association of psoriasis with UC.37,38,40,43 Significant statistical heterogeneity was identified across the 4 studies (I2 = 54%). As illustrated in Figure 3B,37,38,40,43 the meta-analysis revealed a significant association of psoriasis with UC (pooled OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.49-2.05).

All 4 included cohort studies illustrated an increased risk of CD and UC in patients with psoriasis.41,42,44,45 The meta-analysis revealed that patients with psoriasis had a significantly increased risk of CD (pooled RR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.65-3.89) (Figure 3C)41,42,44,45 and UC (pooled RR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.55-1.89) (Figure 3D).41,42,44,45 Substantial statistical heterogeneity was found in the risk estimate for CD (I2 = 55%) (Figure 3C)41,42,44,45 but not for UC (I2 = 0%) (Figure 3D).41,42,44,45

Subgroup Analysis on Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis

One case-control study and 2 cohort studies investigated the association of psoriatic arthritis with CD and UC.43,44,45 The case-control study found significant associations of psoriatic arthritis with CD (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.59-3.03) and UC (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.21-3.00).43 As illustrated in Figure 3E,44,45 the meta-analysis on the 2 cohort studies demonstrated a significantly increased risk of CD (RR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.41-5.32; I2 = 0%) and a nonsignificant increase in the risk of UC (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 0.72-4.17; I2 = 34%) in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis to examine the association of psoriasis with IBD. We found that patients with psoriasis were prone to have comorbid IBD. The evidence from case-control studies indicates that patients with psoriasis had 1.70-fold increased odds of developing CD and 1.75-fold increased odds of developing UC when compared with controls. Meanwhile, the evidence from cohort studies revealed that patients with psoriasis had a 2.53-fold increased risk of developing CD and a 1.71-fold increased risk of developing UC when compared with controls. The subgroup analysis on patients with psoriatic arthritis showed similar results. Patients with psoriatic arthritis had a 2.74-fold risk of developing CD and a 1.74-fold risk of developing UC when compared with controls.

Only 1 case-control study evaluated the association of psoriasis with CD in Asians; it showed a negative association of psoriasis with CD in Asians (OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52-0.94). By contrast, all the other studies were conducted in Western countries and Israel, and found a significant association of psoriasis with CD (pooled OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.84-2.22; I2 = 3%).

Most of the included studies were rated as low risk of bias according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Three included studies were rated as high risk of bias for the following reasons: no control for confounders,38 study participants from a specific group,41 and lack of relevant information on the outcome interest not present at the start of the study.44 These points in study design should be considered in future studies.

The possible explanations for the identified association of psoriasis with IBD include genetic abnormalities, immune dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and dysregulation of gut microbiota. A few studies have explored the genetic link between psoriasis and IBD. Chromosomal locus 6p21, an area encompassing the major compatibility complex (MHC)–related genes, is the most extensively studied genetic region.46 Psoriasis and IBD shared same the genetic susceptibility loci on chromosome 6p21, which corresponds to PSORS1 in psoriasis and IBD3 in IBD.7 Furthermore, genes not related to major compatibility complex, including IL23R and IL12B, have been identified in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and IBD.28,29,30 The IL23R gene encodes a subunit of the IL-23 receptor and affects the binding capability of IL-23. Interleukin-23 is essential for the differentiation and activation of TH17 lymphocytes that produce IL-17. Binding of IL-17 to its receptor stimulates hyperproliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes, maturation of myeloid dendritic cells, and recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages in psoriatic lesions.31,32 In the gastrointestinal system, increased expression of IL-17 in the mucosa of the gut and serum in patients with IBD in comparison with healthy controls has been found.33 The evidence supports the possibility that IL-17 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD. Moreover, the IL12B gene encodes the p40 subunit that participates in the signaling pathways of both IL-12 and IL-23.47 Therefore, IL-12B is an essential cytokine subunit in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and IBD.

On the other hand, the skin and gut show similarities in IBD and psoriasis, including immense microbial diversity and bountiful blood supply.48 Microbiota affect the physiology and immune response of the epithelium of the skin and gut by regulating biological metabolites.49,50 In addition, the microbiota may lead to expression of antimicrobial particles, elevated cytokine levels, and, consequently, regulation of activity and differentiation of T cells.51 Therefore, microbiota dysfunction may cause systemic immune dysregulation. The emerging evidence supports the gut-skin axis theory that describes the close association between intestinal dysbiosis and cutaneous manifestations.52 Patients with psoriasis have been found to present with decreased diversity and abundance of gut microbiota that was similar to patients with IBD.53

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we found that only 1 cohort study reported the association between different severity of psoriasis and IBD.42 Second, only 1 case-control study provided data on the association of psoriasis with IBD in Asians.39 More studies are warranted to confirm if psoriasis is inversely associated with IBD in this population. Third, owing to the variation in sample size across the included studies, the relative weight of studies varied in different subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, the overall direction of effects was consistent.

Conclusions

The evidence to date supports an association of psoriasis with IBD. Patients with psoriasis should be informed about the increased risk of IBD. Gastroenterology consultation is indicated for patients with psoriasis presenting with bowel symptoms.

eTable. Search Strategy

References

- 1.Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):205-212. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):496-509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronckers IM, Paller AS, van Geel MJ, van de Kerkhof PC, Seyger MM. Psoriasis in children and adolescents: diagnosis, management and comorbidities. Paediatr Drugs. 2015;17(5):373-384. doi: 10.1007/s40272-015-0137-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983-994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1: overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826-850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skroza N, Proietti I, Pampena R, et al. Correlations between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:983902. doi: 10.1155/2013/983902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb AB, Chao C, Dann F. Psoriasis comorbidities. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19(1):5-21. doi: 10.1080/09546630701364768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira MdeF, Rocha BdeO, Duarte GV. Psoriasis: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(1):9-20. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machado-Pinto J, Diniz MdosS, Bavoso NC. Psoriasis: new comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(1):8-14. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malkic Salihbegovic E, Hadzigrahic N, Cickusic AJ. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Med Arch. 2015;69(2):85-87. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.85-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi CC, Wang J, Chen YF, Wang SH, Chen FL, Tung TH. Risk of incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in patients with psoriasis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78(3):232-238. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi CC, Chen TH, Wang SH, Tung TH. Risk of suicidality in people with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(5):621-627. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0281-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi CC, Tung TH, Wang J, et al. Risk of uveitis among people with psoriasis: a nationwide cohort study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(5):415-422. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SH, Chi CC, Hu S. Cost-efficacy of biologic therapies for moderate to severe psoriasis from the perspective of the Taiwanese healthcare system. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1151-1156. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang TS, Chi CC, Wang SH, Lin JC, Lin KM. Cost-efficacy of biologic therapies for psoriatic arthritis from the perspective of the Taiwanese healthcare system. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(10):1002-1009. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh ML, Ko SH, Wang MH, Chi CC, Chung YC. Acupuncture-related techniques for psoriasis: a systematic review with pairwise and network meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23(12):930-940. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573-621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellinghaus D, Bethune J, Petersen BS, Franke A. The genetics of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—status quo and beyond. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(1):13-23. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.990507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390(10114):2769-2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho JH, Weaver CT. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1327-1339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):596-604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1641-1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bielefeldt K, Davis B, Binion DG. Pain and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(5):778-788. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(suppl A):5A-36A. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binder HJ. Mechanisms of diarrhea in inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:285-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capon F, Di Meglio P, Szaub J, et al. Sequence variants in the genes for the interleukin-23 receptor (IL23R) and its ligand (IL12B) confer protection against psoriasis. Hum Genet. 2007;122(2):201-206. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0397-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cargill M, Schrodi SJ, Chang M, et al. A large-scale genetic association study confirms IL12B and leads to the identification of IL23R as psoriasis-risk genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(2):273-290. doi: 10.1086/511051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho JH. The genetics and immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(6):458-466. doi: 10.1038/nri2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddur MS, Miossec P, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(1):8-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiricozzi A, Krueger JG. IL-17 targeted therapies for psoriasis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22(8):993-1005. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.806483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujino S, Andoh A, Bamba S, et al. Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2003;52(1):65-70. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed March 12, 2018.

- 37.Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Birkenfeld S. Psoriasis associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(5):561-565. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Augustin M, Reich K, Glaeske G, Schaefer I, Radtke M. Co-morbidity and age-related prevalence of psoriasis: Analysis of health insurance data in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(2):147-151. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai TF, Wang TS, Hung ST, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63(1):40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KYT, Herrinton LJ. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):924-930. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li WQ, Han JL, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn’s disease in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1200-1205. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egeberg A, Mallbris L, Warren RB, et al. Association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(3):487-492. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(11):2679-2684. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3374-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manos CK, Xiao R, Brandon TG, Ogdie A, Weiss PF. Risk factors for arthritis and the development of comorbid cardiovascular and metabolic disease in children with psoriasis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/risk-factors-for-arthritis-and-the-development-of-comorbid-cardiovascular-and-metabolic-disease-in-children-with-psoriasis/. Accessed September 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charlton R, Green A, Shaddick G, et al. ; PROMPT study group . Risk of uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease in people with psoriatic arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):277-280. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad T, Marshall SE, Jewell D. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease: the role of the HLA complex. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(23):3628-3635. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nair RP, Ruether A, Stuart PE, et al. Polymorphisms of the IL12B and IL23R genes are associated with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(7):1653-1661. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, Boland CR, Menter A. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(2):211.e1-211.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121-141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharon G, Garg N, Debelius J, Knight R, Dorrestein PC, Mazmanian SK. Specialized metabolites from the microbiome in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):719-730. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zákostelská Z, Málková J, Klimešová K, et al. Intestinal microbiota promotes psoriasis-like skin inflammation by enhancing Th17 response. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Neill CA, Monteleone G, McLaughlin JT, Paus R. The gut-skin axis in health and disease: a paradigm with therapeutic implications. Bioessays. 2016;38(11):1167-1176. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A, et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):128-139. doi: 10.1002/art.38892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Search Strategy