Abstract

Importance

Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery (MILS) for endometrial cancer reduces surgical morbidity compared with a total abdominal hysterectomy. However, only a minority of women with early-stage endometrial cancer undergo MILS.

Objective

To evaluate the association between the Danish nationwide introduction of minimally invasive robotic surgery (MIRS) and severe complications in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this nationwide prospective cohort study of 5654 women with early-stage endometrial cancer who had undergone surgery during the period from January 1, 2005, to June 30, 2015, data from the Danish Gynecological Cancer Database were linked with national registers on socioeconomic status, deaths, hospital diagnoses, and hospital treatments. The women were divided into 2 groups; group 1 underwent surgery before the introduction of MIRS in their region, and group 2 underwent surgery after the introduction of MIRS. Women with an unknown disease stage, an unknown association with MIRS implementation, unknown histologic findings, sarcoma, or synchronous cancer were excluded, as were women who underwent vaginal or an unknown surgical type of hysterectomy. Statistical analysis was conducted from February 2, 2017, to May 4, 2018.

Exposure

Minimally invasive robotic surgery, MILS, or total abdominal hysterectomy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Severe complications were dichotomized and encompassed death within 30 days after surgery and intraoperative and postoperative complications diagnosed within 90 days after surgery.

Results

A total of 3091 women (mean [SD] age, 67 [10] years) were allocated to group 1, and a total of 2563 women (mean [SD] age, 68 [10] years) were allocated to group 2. In multivariate logistic regression analyses, the odds of severe complications were significantly higher in group 1 than in group 2 (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11-1.74). The proportion of women undergoing MILS was 14.1% (n = 436) in group 1 and 22.2% in group 2 (n = 569). The proportion of women undergoing MIRS in group 2 was 50.0% (n = 1282). In group 2, multivariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that a total abdominal hysterectomy was associated with increased odds of severe complications compared with MILS (OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.80-3.70) and MIRS (OR, 3.87; 95% CI, 2.52-5.93). No difference was found for MILS compared with MIRS (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.99-2.27).

Conclusions and Relevance

The national introduction of MIRS changed the surgical approach for early-stage endometrial cancer from open surgery to minimally invasive surgery. This change in surgical approach was associated with a significantly reduced risk of severe complications.

This cohort study evaluates the association between the nationwide introduction of minimally invasive robotic surgery in Denmark and severe complications in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer.

Key Points

Question

Is the nationwide introduction of minimally invasive robotic surgery associated with a decreased risk of severe complications in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer?

Findings

A Danish nationwide cohort of 5654 women with early-stage endometrial cancer was divided into 2 groups based on the time of the introduction of minimally invasive robotic surgery in their region. The risk of severe complications was significantly reduced in the group undergoing surgery after the introduction of minimally invasive robotic surgery.

Meaning

The national implementation of minimally invasive robotic surgery was associated with an increased proportion of minimally invasive surgical procedures, which translated into a reduced risk of severe complications in women with early-stage endometrial cancer.

Introduction

Several randomized clinical trials have confirmed that minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery (MILS) for early-stage endometrial cancer is associated with reduced morbidity compared with a total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH).1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Globally, the MILS rate for endometrial cancer is low, which is most likely related to the steep learning curve in complex oncologic surgical procedures.10,11,12,13,14,15 Minimally invasive robotic surgery (MIRS) was approved for treatment of gynecologic conditions in 2005.16 The technique offers enhanced visualization, movements, and ergonomics and was rapidly accepted by surgeons worldwide. Data from highly specialized institutions suggest that the implementation of MIRS increases the use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS).17,18,19,20,21

In Denmark, the treatment of early-stage endometrial cancer was gradually centralized from 28 departments in 2005 to 6 national cancer centers in 2012. During the first years of the centralization process, only patients with high-risk histologic characteristics were referred, followed by a transition to the referral of the entire group as requested by the National Board of Health. Each center implemented MIRS between 2008 and 2013.

In the present population-based study, we aimed to evaluate whether the nationwide introduction of MIRS was associated with a decreased risk of severe complications in women with early-stage endometrial cancer.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This is a study of nationwide registers based on prospectively obtained data. In the design, we take advantage of the “natural experiment” that took place when MIRS was introduced nationwide in Denmark. The introduction took place gradually across the 6 national cancer centers, which, to some extent, mimics a multicenter stepped-wedge design. The main division of the data corresponds to a multicenter before-after design (eFigure in the Supplement), followed by an adjusted comparison of the 3 concurrent surgical modalities. The study was approved by the Data Protection Agency. The Danish Gynecological Cancer Database (DGCD) is a scientific quality assurance register with mandatory entry of the data (commanded by the Danish government). Danish researchers may request access to the data in the DGCD, which requires approval from the Danish Gynecological Cancer Group and the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Population

All consecutive women who underwent surgical treatment for International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I or II endometrial cancer from January 1, 2005, to June 30, 2015, were identified.

Exposures and Outcomes

Surgical modality was categorized as TAH, MILS, or MIRS. Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery encompassed total laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. The women were divided into 2 groups: group 1 underwent surgery before MIRS was introduced, and group 2 underwent surgery after MIRS was introduced. The date dividing the groups was set as the date of the first such procedure performed at each cancer center for early-stage endometrial cancer. If a woman underwent TAH or MILS outside a cancer center during the MIRS introductory period and the information on region was missing, she was excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was severe complications, which were dichotomized for each woman into absent or present. Prior to data collection, severe complications were defined to include 30-day mortality and severe intraoperative and postoperative complications. Severe intraoperative complications were defined as unintended vascular, urinary tract, bowel, or nerve damage. Severe postoperative complications encompassed 90 postoperative days and included acute renal failure, paralytic ileus, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute myocardial infarction, sepsis, fistula, postoperative deep or intra-abdominal hematoma, surgical evacuation of cavities, and the need for gynecologic reoperation.

Data Collection and Merging

All Danish citizens are at birth or immigration provided with a unique civil registration number that is used for all contacts with the municipality and the health care system (the Danish Civil Registration System).22 More than 100 nationwide registers and clinical databases using the civil registration number exist and provide researchers with the possibility to unambiguously link the information between registers. All linkage of data with information from nationwide registers was performed using the Danish civil registration number.22 Linkage of the data was performed by Statistics Denmark. The research group performing the data entry and data merging were blinded.

The Danish Gynecological Cancer Database

The cohort was extracted from the DGCD, which is a nationwide and validated cancer register with mandatory registration of all women with newly diagnosed gynecologic cancer.23 The register holds prospectively obtained information on demographic, clinical, surgical, and pathologic data related to the index operation.

The Danish National Patient Register

The Danish National Patient Register (NPR) holds information on all hospital contacts with the corresponding diagnoses and treatments coded.24 The NPR holds high validity on the registration of severe conditions and was used to extract data on comorbidities and severe intraoperative and postoperative complications. Minor complications (eg, cystitis) were excluded because they are often treated by the general practitioner, whose diagnoses and treatments are not registered in the NPR. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was estimated based on diagnoses recorded in the NPR up to 10 years before surgery and categorized into none (0), mild (1), and moderate to severe (≥2).25,26,27

The Danish Register of Causes of Death

The Danish Register of Causes of Death is based on the mandatory death certificate that is completed by physicians during medical inquest. The 30-day mortality used in the registration of severe complications is derived from this register.28

The Integrated Database for Labor Market Research

Information on the educational level of each patient was obtained from the Population Education Register, and information on the disposable income of each patient the year before surgery was obtained from the Income Statistics Register.29,30 The socioeconomic status of each patient was ranked on a 5-point scale based on their educational level and their disposable income the year before surgery.31,32

Categorization of Variables From the DGCD

Surgical modality and the dates derived from the DGCD were used for grouping of the exposures as previously described. Age was reported in years and grouped into quartiles. Body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was grouped into 4 categories according to cutoff values in the World Health Organization classification33 (<25.0, 25.0-29.9, 30.0-34.9, and ≥35.0). A BMI less than 13.0 and a BMI greater than 98.0 were considered implausible and were recorded as missing. Smoking status was grouped into 3 categories in the DGCD: nonsmoker, smoker, and previous smoker. Physical status was reported according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and categorized into no systemic disease (I), mild systemic disease (II), and moderate to severe systemic disease (≥III).34 Information on intra-abdominal adhesions was dichotomized as yes or no.35 Definitions of histopathologic risk groups (low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk) were based on the depth of myometrial invasion and histologic grade according to the FIGO 2009 guidelines.36,37 Furthermore, women with stage II disease or nonendometrioid adenocarcinoma (carcinosarcoma included) were considered to be at high risk, in line with the new ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO (European Society for Medical Oncology–European Society of Gynaecological Oncology–European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology) guideline.38 Thus, histopathologic risk was defined as follows: low, endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage IA with grade I or II; intermediate, endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage IB with grade I or II or endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage IA with grade III; high, endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage IB with grade III, endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage II, or nonendometrioid carcinoma; and unknown, endometrioid adenocarcinoma stage I with unknown grade. Lymph node dissection was reported as a dichotomized variable (yes or no). Information on the number of lymph nodes removed was not available. Treatment at a cancer center vs a nonspecialized gynecologic department was noted as a dichotomized variable.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from February 2, 2017, to May 4, 2018. The distribution for demographic and tumor characteristics between group 1 and group 2 and among the 3 surgical modalities (TAH, MILS, and MIRS) was compared by use of χ2 tests.

A logistic regression model was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI for severe complications. We compared severe complications in group 1 and group 2 and stratified them using the 2 surgical modalities (TAH and MIS). Furthermore, restricted analyses in group 2 were performed comparing severe complications among the 3 surgical modalities (TAH, MILS, and MIRS).

Univariate analyses and adjusted ORs for prespecified potential confounders were performed and included age, BMI, smoking status, ASA score, intra-abdominal adhesions, socioeconomic status, histologic risk groups, lymphadenectomy, and surgical year. The models were initially adjusted for confounders that were considered the most important clinically: age, ASA score, lymphadenectomy, and BMI. Furthermore, the model was tested for other potential confounders, and those that had a significant association were included in the model. Likelihood ratio tests were used to evaluate whether potential interactions between the key confounding factors were statistically significant. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the models. Furthermore, the model that compared the 3 concomitant surgical modalities was adjusted for site-level clustering after the centralization was accomplished (ie, to account for the correlation between the sites and the risk of severe complications). Women with missing data were excluded from the adjusted analyses. In addition, an explorative adjusted model was generated to see whether an MIRS learning curve could be identified within group 2. In this model, the surgical year was replaced by a variable of time since MIRS introduction alongside an interaction term between the new time variable and surgical modalities.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the potential effect of missing data. The OR of severe complications for the entire population and the OR of severe complications for the women included in the fully adjusted analyses were compared.

All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. All analyses were conducted using STATA, version 15.0 (StataCorp).

Results

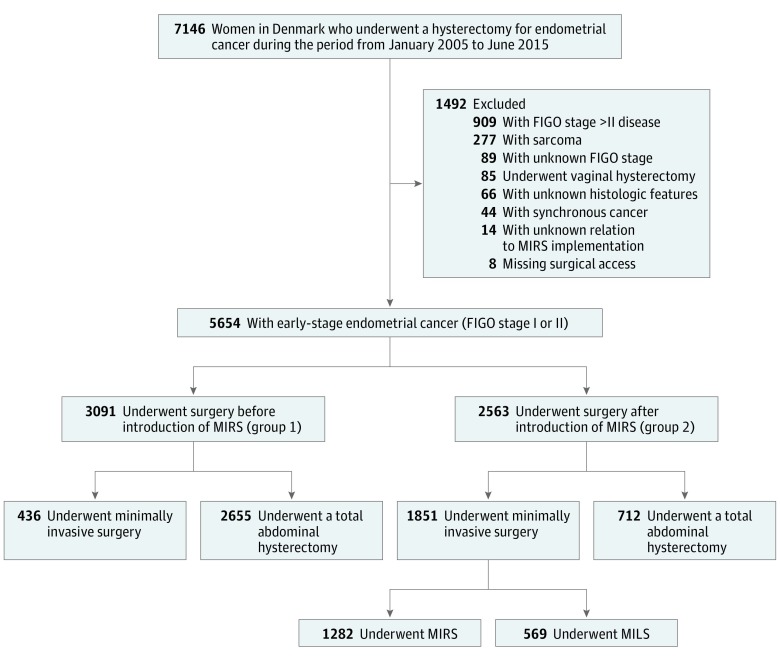

In total, 5654 women with stage I or II endometrial cancer underwent surgery during the study period (Figure 1). Of these women, 3091 (mean [SD] age, 67 [10] years) underwent surgery before the implementation of MIRS (group 1) and 2563 (mean [SD] age, 68 [10] years) underwent surgery after the implementation of MIRS (group 2). The 2 groups differed significantly regarding several clinical, sociodemographic, and histopathologic characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Patient Inclusion.

FIGO indicates International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology; MIRS, minimally invasive robotic surgery.

Table 1. Data on Women With FIGO Stage I or II Endometrial Cancer Who Had Surgery Before (Group 1) or After (Group 2) Introduction of MIRS.

| Characteristic | Women, No. (%) | P Valuea | Women, No. (%) | P Valuea | Women, No. (%) | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIS Group 1 (n = 436) | MIS Group 2 (n = 1851) | TAH Group 1 (n = 2655) | TAH Group 2 (n = 712) | Overall Group 1 (n = 3091) | Overall Group 2 (n = 2563) | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤59 y | 118 (27.1) | 441 (23.8) | .06 | 641 (24.1) | 145 (20.4) | .004 | 759 (24.6) | 586 (22.9) | .03 |

| 60-66 y | 123 (28.2) | 451 (24.4) | 692 (26.1) | 166 (23.3) | 815 (26.4) | 617 (24.1) | |||

| 67-74 y | 111 (25.5) | 521 (28.2) | 648 (24.4) | 175 (24.6) | 759 (24.6) | 696 (27.2) | |||

| ≥75 y | 84 (19.3) | 438 (23.7) | 674 (25.4) | 226 (31.7) | 758 (24.5) | 664 (25.9) | |||

| BMI | |||||||||

| <25.0 | 152 (35.7) | 539 (30.6) | .23 | 891 (34.4) | 245 (35.3) | .72 | 1043 (34.5) | 784 (31.9) | .004 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 112 (26.3) | 494 (28.0) | 801 (30.9) | 217 (31.2) | 913 (30.2) | 711 (28.9) | |||

| 30.0-34.9 | 78 (18.3) | 361 (20.5) | 501 (19.3) | 121 (17.4) | 579 (19.2) | 482 (19.6) | |||

| ≥35.0 | 84 (19.7) | 370 (21.0) | 401 (15.5) | 112 (16.1) | 485 (16.1) | 482 (19.6) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 10 | 87 | 61 | 17 | 71 | 104 | |||

| CCI | |||||||||

| 0 | 293 (67.2) | 1220 (65.9) | .18 | 1769 (66.6) | 442 (62.1) | .08 | 2062 (66.7) | 1662 (64.9) | .09 |

| 1 | 89 (20.4) | 340 (18.4) | 399 (15.0) | 121 (17.0) | 488 (15.8) | 461 (18.0) | |||

| ≥2 | 54 (12.4) | 291 (15.7) | 487 (18.3) | 149 (20.9) | 541 (17.5) | 440 (17.2) | |||

| ASA class | |||||||||

| I | 201 (46.4) | 587 (32.2) | <.001 | 1007 (38.0) | 196 (27.7) | <.001 | 1208 (39.2) | 783 (30.9) | <.001 |

| II | 207 (47.8) | 1041 (57.1) | 1376 (51.9) | 407 (57.5) | 1583 (51.3) | 1448 (57.2) | |||

| ≥III | 25 (5.8) | 196 (10.8) | 269 (10.1) | 105 (14.8) | 294 (9.5) | 301 (11.9) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 3 | 27 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 31 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Never | 296 (71.0) | 1115 (67.6) | .003 | 1381 (63.8) | 392 (62.7) | .001 | 1677 (65.0) | 1507 (66.2) | <.001 |

| Former | 55 (13.2) | 329 (19.9) | 366 (16.9) | 140 (22.4) | 421 (16.3) | 469 (20.6) | |||

| Active | 66 (15.8) | 206 (12.5) | 417 (19.3) | 93 (14.9) | 483 (18.7) | 299 (13.1) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 19 | 201 | 491 | 87 | 510 | 288 | |||

| Tumor riskb | |||||||||

| Low | 280 (65.4) | 1126 (62.3) | .007 | 1362 (52.4) | 319 (45.3) | <.001 | 1642 (54.2) | 1445 (57.6) | .001 |

| Intermediate | 93 (21.7) | 335 (18.5) | 623 (24.0) | 148 (21.0) | 716 (23.7) | 483 (19.2) | |||

| High | 55 (12.9) | 346 (19.2) | 615 (23.7) | 237 (33.7) | 670 (22.1) | 583 (23.2) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 8 | 44 | 55 | 8 | 63 | 52 | |||

| Intra-abdominal adhesion | |||||||||

| No | 372 (85.7) | 1169 (64.2) | <.001 | 2034 (76.6) | 462 (65.1) | <.001 | 2406 (77.9) | 1631 (64.4) | <.001 |

| Yes | 62 (14.3) | 652 (35.8) | 620 (23.4) | 248 (34.9) | 682 (22.1) | 900 (35.6) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 2 | 30 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 32 | |||

| Lymphadenectomy | |||||||||

| No | 311 (71.3) | 1222 (67.1) | .09 | 1995 (75.4) | 400 (58.1) | <.001 | 2306 (74.8) | 1662 (64.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 125 (28.7) | 599 (32.9) | 651 (24.6) | 289 (41.9) | 776 (25.2) | 888 (35.4) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 0 | 30 | 9 | 23 | 9 | 53 | |||

| Socioeconomic class | |||||||||

| High | 56 (12.8) | 293 (15.8) | .50 | 320 (12.1) | 99 (13.9) | <.001 | 376 (12.2) | 392 (15.3) | .001 |

| Intermediate-high | 86 (19.7) | 323 (17.5) | 399 (13.0) | 129 (18.1) | 485 (15.7) | 452 (17.6) | |||

| Intermediate | 93 (21.3) | 399 (21.6) | 546 (20.6) | 169 (23.7) | 639 (20.7) | 568 (22.2) | |||

| Intermediate-low | 122 (28.0) | 494 (26.7) | 771 (29.0) | 202 (28.4) | 893 (28.9) | 696 (27.2) | |||

| Low | 79 (18.1) | 342 (18.5) | 619 (23.3) | 113 (15.9) | 698 (22.6) | 455 (17.8) | |||

| Treatment at cancer center | |||||||||

| No | 44 (10.1) | 10 (0.5) | <.001 | 1276 (48.1) | 91 (12.8) | <.001 | 1320 (42.7) | 101 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Yes | 392 (89.9) | 1841 (99.5) | 1378 (51.9) | 621 (87.2) | 1770 (57.3) | 2462 (96.1) | |||

| Unknown, No. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; DGCD, Danish Gynecological Cancer Database; FIGO, International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology; MIRS, minimally invasive robotic surgery; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Patients with missing values in noncrucial variables are included for transparency and sensitivity analyses. P values reflect comparison of patients without missing values.

Histopathologic risk is defined in the Categorization of Variables From the DGCD subsection of the Methods section.

A total of 226 women in group 1 experienced severe complications (7.3%; 95% CI, 6.4%-8.3%), and a total of 160 women in group 2 experienced severe complications (6.2%; 95% CI, 5.3%-7.2%) (Table 2). We also observed that 7 of 5654 women (0.12%) had acute renal failure and that 15 of 5654 (0.27%) had sepsis. A multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the odds of severe complications were associated with lymphadenectomy, histopathologic tumor risk group, ASA score, intra-abdominal adhesions, and BMI. Age, surgical year, smoking status, and socioeconomic status were not significantly associated with the odds of severe complications. In the adjusted analyses, the odds of severe complications were significantly higher among women in group 1 compared with women in group 2 (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11-1.74). In the overall comparison of groups, the surgical approach was not incorporated in the analysis. The model was repeated within stratified analyses among women who underwent minimally invasive techniques and open procedures. The stratified and adjusted analyses did not demonstrate any difference in odds of severe complications (Table 3).

Table 2. Data on Women With FIGO Stage I or II Endometrial Cancer Who Experienced Severe Complications Before (Group 1) or After (Group 2) Introduction of MIRS.

| Characteristic | Women, No. (%) [95% CI] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIS Group 1 (n = 436) | MIS Group 2 (n = 1851) | TAH Group 1 (n = 2655) | TAH Group 2 (n = 712) | Overall Group 1 (n = 3091) | Overall Group 2 (n = 2563) | |

| 30-d Mortality | 0 | 2 (0.1) [0.0-0.4] | 9 (0.3) [0.2-0.6] | 5 (0.7) [0.2-1.6] | 9 (0.3) [0.1-0.6] | 7 (0.3) [0.1-0.6] |

| Intraoperative complicationsa | 0 | 9 (0.5) [0.2-0.9] | 6 (0.2) [0.1-0.5] | 2 (0.3) [0.0-1.0] | 6 (0.2) [0.1-0.4] | 11 (0.4) [0.2-0.8] |

| 90-d Postoperative complicationsa | 24 (5.5) [3.6-8.1] | 72 (3.9) [3.1-4.8] | 189 (7.1) [6.2-8.2] | 75 (10.5) [8.4-13.0] | 213 (6.9) [6.0-7.8] | 147 (5.7) [4.9-6.7] |

| Any complicationsa | 24 (5.5) [3.6-8.1] | 79 (4.3) [3.4-5.3] | 202 (7.6) [6.6-8.7] | 81 (11.4) [9.1-13.9] | 226 (7.3) [6.4-8.3] | 160 (6.2) [5.3-7.2] |

Abbreviations: FIGO, International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology; MIRS, minimally invasive robotic surgery; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Each woman who experienced 1 or several complications was registered once.

Table 3. Odds of Severe Complications Before (Group 1) or After (Group 2) Introduction of MIRS.

| Procedure and Group | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||

| Group 1 | 1.18 (0.96-1.46) | 1.39 (1.11-1.74)a |

| Group 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| TAH | ||

| Group 1 | 0.64 (0.49-0.84) | 0.79 (0.59-1.06)a |

| Group 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| MIS | ||

| Group 1 | 1.31 (0.82-2.09) | 1.42 (0.85-2.37)a |

| Group 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Group 2 | ||

| TAH | 3.16 (2.20-4.56) | 3.87 (2.52-5.93)b |

| MILS | 1.32 (0.83-2.11) | 1.50 (0.99-2.27)b |

| MIRS | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: MILS, minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery; MIRS, minimally invasive robotic surgery; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; OR, odds ratio; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Adjusted for age, lymphadenectomy, histopathologic risk, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, intra-abdominal adhesions, and body mass index. The stratified comparison of MIS was underpowered for the adjustments because women in MIS group 1 were highly selected and the number of complications was low (n = 24).

Adjusted for age, lymphadenectomy, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, body mass index, socioeconomic status, and surgical year. The analysis model was not influenced significantly by histopathologic risk, intra-abdominal adhesions, or smoking status.

Among women in group 2, severe complications occurred in 81 of 712 who underwent TAH (11.4%; 95% CI, 9.1%-13.9%), 29 of 569 who underwent MILS (5.1%; 95% CI, 3.4%-7.2%), and 59 of 1282 who underwent MIRS (4.6%; 95% CI, 2.9%-5.1%). A multiple logistic regression model for severe complications in group 2 demonstrated that the odds of severe complications were associated with lymphadenectomy, ASA score, BMI, socioeconomic status, and surgical year but were not associated with age, smoking status, tumor risk group, socioeconomic group, and intra-abdominal adhesions. In the adjusted analyses, TAH was associated with increased odds of complications compared with MILS (OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.80-3.70) and MIRS (OR, 3.87; 95% CI, 2.52-5.93), whereas no significant difference in the odds of complications was found when women who had MILS were compared with those who had MIRS (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.99-2.27). No significant differences were found in sensitivity analyses.

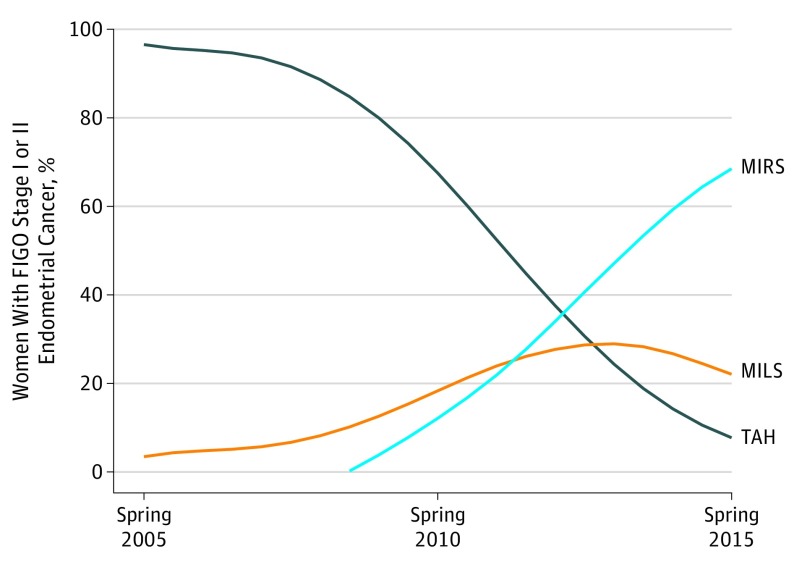

In group 1, 2655 women (85.9%) underwent TAH, and 436 women (14.1%) underwent MILS. In group 2, 712 women (27.8%) underwent TAH, 569 women (22.2%) underwent MILS, and 1282 women (50.0%) underwent MIRS. The nationwide use of MIS increased from 3% in 2005 to 95% in 2015 (Figure 2). Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery was accessible throughout the study period, whereas MIRS was gradually implemented between 2008 and 2013 in all cancer centers. In 2005, 202 of 488 women (41.4%) had surgical procedures at gynecologic cancer centers; this number gradually increased to 535 of 554 (96.6%) in 2012. In 2005, 49 of 488 women (10.0%) underwent staging lymph node dissections, gradually increasing to 201 of 525 (38.3%) in 2010. The proportion of staging lymph node dissections remained stable, between 34.9% (197 of 565) and 39.5% (209 of 529), from 2010 to 2015. Trends of changes in the OR of severe complications after MIRS along a potential learning curve after the introduction of MIRS were not observed.

Figure 2. Surgical Approach Among Women With Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer Demonstrated Over Time.

FIGO indicates International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology; MILS, minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery; MIRS, minimally invasive robotic surgery; and TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study describes the first analyses of how a nationwide implementation of MIRS affected the risk of surgical complications in an unselected national cohort of women with early-stage endometrial cancer. The implementation of MIRS led to an increase in the proportion of women who underwent MIS, and it reduced the number of severe complications. The reduction in the number of severe complications was observed despite a higher proportion of women with an older age, a high ASA score, high-risk histopathologic characteristics, and intra-abdominal adhesions being offered MIS and a higher proportion of women undergoing staging lymphadenectomy. Randomized trials on TAH vs MIRS have reported a decreased risk of complications after laparoscopy.3,4,5,8,39,40,41,42 Thus, in line with earlier findings from single-institution trials,17,19,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52 multi-institution trials,10,11,53,54,55,56,57 and randomized clinical trials in selected cohorts,3,4,5,8,39,40,41,42 our nationwide study confirms that MIS for women with early-stage endometrial cancer decreases the risk of severe complications compared with open surgery. Furthermore, the present study supports earlier reports from specialized single-institution trials that using MIRS for early-stage endometrial cancer decreases the risk of surgical complications.17,20,21,58,59

Studies in selected cohorts have compared complications between minimally invasive approaches and reported equal or improved results after MIRS.17,45,46,48,51,52,54,55,56 In contrast, Wright et al10 demonstrated an increased complication rate after MIRS (23.7%) compared with MILS (19.5%) for endometrial cancer. The study reported comparatively high, severe complication rates of 39.7% after TAH and 22.7% after MIS. The authors ascribe the higher risk of complications after MIRS to an increased proportion of medical complications, in particular, bacteremia and respiratory and renal failures in the MIRS group. The data in the study by Wright et al10 were derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Medicare database, which combines data from the National Cancer Database and claims from patients covered by Medicare.60 Medicare is a US government insurance system that aims to support persons 65 years of age or older, persons receiving chemotherapy, persons with end-stage renal disease, persons with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and younger persons with disabilities.57 Wright et al10 adjusted for the complexity within this cohort by using propensity score matching weighted by the inverse probability of treatment with additional stabilizing techniques. However, we believe that the increased odds of complications after MIRS compared with MILS is a result of selection bias related to the allocation of women with a higher risk of complications to undergo MIRS rather than to the higher risk of complications after MIRS. In our study, we observed that 0.12% of women had acute renal failure and that 0.27% had sepsis. The proportions of acute renal failure and of sepsis found in our study correspond with previous reports on women with endometrial cancer.45,53,55,61

Bergstrom et al11 have recently proposed a minimally invasive hysterectomy benchmark of more than 80% when performed at high-volume institutions. The study included 1621 women who underwent surgery for endometrial cancer during the period from 2013 to 2014 at 4 national cancer centers. Our study suggests that a nationwide, minimally invasive hysterectomy benchmark of 95% is feasible for early-stage endometrial cancer if treatment is centralized to high-volume cancer centers with MIRS adopted.

In 2002 and 2005, the Danish government launched a nationwide Cancer Action Plan I and II, respectively, in which endometrial cancer treatment was centralized to specialized centers.62,63 The centralization of endometrial cancer treatment was completed in 2012 after gradual implementation. A nationwide centralization of complex surgical procedures induces a high flow of patients and gives the optimal conditions for improving surgical expertise in complex surgical procedures for the treatment of cancer. A high level of surgical expertise may be associated with a decreased number of complications, but centralization may also facilitate more comprehensive surgery and may offer surgery for patients with cancer and comorbid conditions. Only 101 women in group 2 received treatment outside the cancer centers; these women had few severe complications. Therefore, adjustment or stratification for centralization in the adjusted regression analyses was not possible, and the degree and direction of a potential association of centralization on our outcome remains unknown.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study was strengthened by the inclusion of prospectively entered national data during a 10-year period with the gradual introduction of MIRS. By dividing the women into groups according to the availability of MIRS, we avoided a comparison across surgical modalities that were not available during the time frame.

Our study included 97% of all women who underwent surgery for early-stage endometrial cancer in Denmark, thus minimizing selection. The DGCD consecutively performs external validation and data quality improvement through updated national registers generating deficiency lists that are completed by the departments responsible for reporting. However, all register-based studies are at risk of information bias. The registration of minor complications may be underreported in the NPR; to minimize such information bias, we included only major complications. Furthermore, severe complications were dichotomized to decrease the risk of multiple registrations of complications with the same origin, increasing the robustness of the analyses.

The MIRS learning curve has been suggested to encompass up to 30 operations,14,61,64,65 and as the nationwide introduction of MIRS was effectuated during the present study, our estimates may be considered conservative.10,13,14 Information on the MILS and MIRS experiences of the surgeons was not available; accordingly, adjustment for the surgeon-specific learning curve was not possible. The absence of an overall learning curve may be due to several factors. The MIRS learning curve is reported to be less steep than that for conventional laparoscopy and therefore was less of a factor. Furthermore, the first surgical procedures performed at each center were performed by skilled cancer surgeons, which means that the learning curve for the Danish surgeons performing MIRS is likely to be scattered over time.

Conclusions

The national introduction of MIRS changed the surgical approach for early-stage endometrial cancer from open surgery to MIS. This change in surgical approach was associated with a significantly reduced risk of severe complications.

eFigure. Centralization and MIRS Introduction in Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer Treatment in Denmark

References

- 1.Galaal K, Bryant A, Fisher AD, Al-Khaduri M, Kew F, Lopes AD. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD006655. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006655.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janda M, Gebski V, Davies LC, et al. . Effect of total laparoscopic hysterectomy vs total abdominal hysterectomy on disease-free survival among women with stage I endometrial cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(12):1224-1233. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fram KM. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy in stage I endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(1):57-61. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malur S, Possover M, Michels W, Schneider A. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal versus abdominal surgery in patients with endometrial cancer—a prospective randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80(2):239-244. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bijen CB, Briët JM, de Bock GH, Arts HJ, Bergsma-Kadijk JA, Mourits MJ. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy in the treatment of patients with early stage endometrial cancer: a randomized multi center study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornblith AB, Huang HQ, Walker JL, Spirtos NM, Rotmensch J, Cella D. Quality of life of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing laparoscopic International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging compared with laparotomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5337-5342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorlu CG, Simsek T, Ari ES. Laparoscopy or laparotomy for the management of endometrial cancer. JSLS. 2005;9(4):442-446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zullo F, Palomba S, Falbo A, et al. . Laparoscopic surgery vs laparotomy for early stage endometrial cancer: long-term data of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):296.e1-296.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, et al. . Total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer: a prospective randomized study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):126-133. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JD, Burke WM, Tergas AI, et al. . Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1087-1096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstrom J, Aloisi A, Armbruster S, et al. . Minimally invasive hysterectomy surgery rates for endometrial cancer performed at National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) centers. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(3):480-484. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fader AN, Java J, Tenney M, et al. . Impact of histology and surgical approach on survival among women with early-stage, high-grade uterine cancer: an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group ancillary analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(3):460-465. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holub Z, Jabor A, Bartos P, Hendl J, Urbánek S. Laparoscopic surgery in women with endometrial cancer: the learning curve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;107(2):195-200. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00373-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seamon LG, Fowler JM, Richardson DL, et al. . A detailed analysis of the learning curve: robotic hysterectomy and pelvic-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(2):162-167. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eltabbakh GH. Effect of surgeon’s experience on the surgical outcome of laparoscopic surgery for women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78(1):58-61. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gala RB, Margulies R, Steinberg A, et al. ; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group . Systematic review of robotic surgery in gynecology: robotic techniques compared with laparoscopy and laparotomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):353-361. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoekstra AV, Jairam-Thodla A, Rademaker A, et al. . The impact of robotics on practice management of endometrial cancer: transitioning from traditional surgery. Int J Med Robot. 2009;5(4):392-397. doi: 10.1002/rcs.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veljovich DS, Paley PJ, Drescher CW, Everett EN, Shah C, Peters WA III. Robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology: program initiation and outcomes after the first year with comparison with laparotomy for endometrial cancer staging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):679.e1-679.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paley PJ, Veljovich DS, Shah CA, et al. . Surgical outcomes in gynecologic oncology in the era of robotics: analysis of first 1000 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):551.e1-551.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau S, Vaknin Z, Ramana-Kumar AV, Halliday D, Franco EL, Gotlieb WH. Outcomes and cost comparisons after introducing a robotics program for endometrial cancer surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):717-724. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824c0956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peiretti M, Zanagnolo V, Bocciolone L, et al. . Robotic surgery: changing the surgical approach for endometrial cancer in a referral cancer center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(4):427-431. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sørensen SM, Bjørn SF, Jochumsen KM, et al. . Danish Gynecological Cancer Database. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:485-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S99479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):30-33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245-1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson Comorbidity Index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):26-29. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Brønnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 suppl):12-16. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The National Centre for Register-Based Research. The integrated database for labour market research (IDA). http://econ.au.dk/the-national-centre-for-register-based-research/danish-registers/the-integrated-database-for-labour-market-research-ida/. Accessed September 12, 2018.

- 31.Quaglia A, Lillini R, Mamo C, Ivaldi E, Vercelli M; SEIH (Socio-Economic Indicators, Health) Working Group . Socio-economic inequalities: a review of methodological issues and the relationships with cancer survival. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85(3):266-277. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7-12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- 35.Brüggmann D, Tchartchian G, Wallwiener M, Münstedt K, Tinneberg H-R, Hackethal A. Intra-abdominal adhesions: definition, origin, significance in surgical practice, and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(44):769-775.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=21116396&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. Pathology & Genetics: Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. WHO Classification of Tumours. 3rd ed. Vol 4. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creasman W. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105(2):109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosse T, Peters EEM, Creutzberg CL, et al. . Substantial lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) is a significant risk factor for recurrence in endometrial cancer—a pooled analysis of PORTEC 1 and 2 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(13):1742-1750. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janda M, Gebski V, Brand A, et al. . Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):772-780. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70145-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. . Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5331-5336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obermair A, Janda M, Baker J, et al. . Improved surgical safety after laparoscopic compared to open surgery for apparent early stage endometrial cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(8):1147-1153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tozzi R, Malur S, Koehler C, Schneider A. Analysis of morbidity in patients with endometrial cancer: is there a commitment to offer laparoscopy? Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(1):4-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boggess JF, Gehrig PA, Cantrell L, et al. . A comparative study of 3 surgical methods for hysterectomy with staging for endometrial cancer: robotic assistance, laparoscopy, laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(4):360.e1-360.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park HK, Helenowski IB, Berry E, Lurain JR, Neubauer NL. A comparison of survival and recurrence outcomes in patients with endometrial cancer undergoing robotic versus open surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(6):961-967. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coronado PJ, Herraiz MA, Magrina JF, Fasero M, Vidart JA. Comparison of perioperative outcomes and cost of robotic-assisted laparoscopy, laparoscopy and laparotomy for endometrial cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(2):289-294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corrado G, Cutillo G, Pomati G, et al. . Surgical and oncological outcome of robotic surgery compared to laparoscopic and abdominal surgery in the management of endometrial cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(8):1074-1081. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ElSahwi KS, Hooper C, De Leon MC, et al. . Comparison between 155 cases of robotic vs 150 cases of open surgical staging for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(2):260-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leitao MM, Narain WR, Boccamazzo D, et al. . Impact of robotic platforms on surgical approach and costs in the management of morbidly obese patients with newly diagnosed uterine cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(7):2192-2198. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-5062-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeNardis SA, Holloway RW, Bigsby GE IV, Pikaart DP, Ahmad S, Finkler NJ. Robotically assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(3):412-417. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seamon LG, Bryant SA, Rheaume PS, et al. . Comprehensive surgical staging for endometrial cancer in obese patients: comparing robotics and laparotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):16-21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aa96c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung YW, Lee DW, Kim SW, et al. . Robot-assisted staging using three robotic arms for endometrial cancer: comparison to laparoscopy and laparotomy at a single institution. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(2):116-121.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=19902479&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1002/jso.21436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Estape R, Lambrou N, Estape E, Vega O, Ojea T. Robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy and staging for the treatment of endometrial cancer: a comparison with conventional laparoscopy and abdominal approaches. J Robot Surg. 2012;6(3):199-205. doi: 10.1007/s11701-011-0290-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fader AN, Seamon LG, Escobar PF, et al. . Minimally invasive surgery versus laparotomy in women with high grade endometrial cancer: a multi-site study performed at high volume cancer centers. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126(2):180-185. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck TL, Schiff MA, Goff BA, Urban RR. Robotic, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy: surgical outcomes by approach in endometrial cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(6):986-993. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright JD, Burke WM, Wilde ET, et al. . Comparative effectiveness of robotic versus laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):783-791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borgfeldt C, Kalapotharakos G, Asciutto KC, Löfgren M, Högberg T. A population-based registry study evaluating surgery in newly diagnosed uterine cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(8):901-911. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scalici J, Laughlin BB, Finan MA, Wang B, Rocconi RP. The trend towards minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for endometrial cancer: an ACS-NSQIP evaluation of surgical outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(3):512-515. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lavoue V, Zeng X, Lau S, et al. . Impact of robotics on the outcome of elderly patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(3):556-562. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ind TEJ, Marshall C, Hacking M, et al. . Introducing robotic surgery into an endometrial cancer service—a prospective evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes in a UK institution. Int J Med Robot. 2016;12(1):137-144. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & you 2018. https://www.calpers.ca.gov/docs/medicare-and-you.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- 61.Lowe MP, Johnson PR, Kamelle SA, Kumar S, Chamberlain DH, Tillmanns TD. A multiinstitutional experience with robotic-assisted hysterectomy with staging for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2, pt 1):236-243. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181af2a74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sundhedsstyrelsen. Kræftplan I. https://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/kraeft/nationale-planer/kraeftplan-i. Accessed August 8, 2016.

- 63.Sundhedsstyrelsen. Kræftplan II. https://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/kraeft/nationale-planer/kraeftplan-ii. Accessed August 8, 2016.

- 64.Lin JF, Frey M, Huang JQ. Learning curve analysis of the first 100 robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by a single surgeon. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124(1):88-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mäenpää M, Nieminen K, Tomás E, Luukkaala T, Mäenpää JU. Implementing robotic surgery to gynecologic oncology: the first 300 operations performed at a tertiary hospital. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(5):482-488. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Centralization and MIRS Introduction in Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer Treatment in Denmark